Abstract

Background

Past series have identified completion pneumonectomy (CP) as a high-risk operation. We evaluated factors affecting outcomes of CP with a selective approach to offering this operation.

Methods

We analyzed a prospective institutional database and abstracted information on patients undergoing pneumonectomy. Patients undergoing CP were compared to those undergoing primary pneumonectomy (PP).

Results

Between 1/2000 and 2/2011, 211 patients underwent pneumonectomy, of which 35 (17%) were CPs. Ten of 35 (29%) CPs were for benign disease and 25/35 (71%) for cancer. Major perioperative morbidity was seen in 21/35 (60%) with 4 (11%) perioperative deaths. In univariate analysis, postoperative bronchopleural fistula (p=0.05) and benign diagnosis (p=0.07) tended to be associated with perioperative mortality.

All 10 patients undergoing CP for benign disease developed a major complication compared to 11/25 (44%) with malignancy, p=0.002. A bronchopleural fistula (4/35, 11%) was more likely to occur in patients undergoing CP shortly after the primary operation (interval between lobectomy and CP; 0.28 vs. 4.5 years; p=0.018) with a trend towards a benign indication for operation (p=0.07). Median survival after CP for benign and malignant indications was 24.3 months and 36.5 months respectively.

Comparing CP patients to those undergoing PP (n=176), CP patients were more likely to undergo surgery for benign disease (10/35, 29% vs. 14/176, 8%, p=0.001). Perioperative mortality for PP was 10/176 (5.7%), and was statistically similar to CP (11%).

Conclusions

Despite a selective approach, CP remains a morbid operation particularly for benign indications. Rigorous preoperative optimization, ruling out contraindications to surgery and attention to technical detail are recommended.

Keywords: Lung cancer surgery, Pneumonectomy

Introduction

Completion pneumonectomy (CP) is often described as a high-risk operation in thoracic surgical literature.(1-6) Major complications occur in up to 60% of patients and operative mortality can be as high as 30%. (1-6) The incidence of major morbidity and perioperative mortality from CP is perceived to be higher than after a primary, one-stage pneumonectomy, however these patient groups are often not compared in published studies.

Many risk factors have been associated with poor outcomes after CP in published studies.(1, 7, 8) In addition to patient-, and disease-related factors, which are largely non-modifiable, technical factors like stump coverage may significantly impact perioperative complications.(1)

Lung cancer is one of the most common indications for CP. (1-6) Over the last decade, several advancements have been made in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. These include the use of minimally invasive surgery in appropriate candidates, and the option of non-surgical treatments like stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), and radiofrequency ablation in patients with prohibitive surgical risks. Most series of CP patients report data from a time-frame prior to these advancements.

With these factors in mind, we investigated the application of CP at our institution over the last decade, using a uniform technical approach and sought to compare patients undergoing CP to those undergoing primary, one-stage pneumonectomy.

Patients and Methods

After Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, we performed a retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database. The need for individual patient consent was waived by the IRB. The search terms “pneumonectomy”, and “completion pneumonectomy” were utilized. Patients undergoing pneumonectomy as part of a transplant operation were excluded. Individuals operated upon between January 2000 and February 2011 were included. This start date was chosen as electronic patient records, including operative reports, were available from this period. The prospectively maintained database was utilized to abstract information about patient demographics, diagnosis, workup, operation, perioperative course, and outcomes. Missing data were obtained by a review of patient charts. Followup information was obtained from clinic notes. This patient list was compared to the social security death index database to ensure consistency and uniformity of information.

Definitions

For the purpose of this study, we defined CP as an operation where remaining lung parenchyma was removed after a prior ipsilateral anatomic resection (segmentectomy, lobectomy, or bilobectomy). We did not consider patients who had undergone a prior wedge resection. A primary, single-stage pneumonectomy was defined as an operation to remove the entire lung, when no prior ipsilateral lung resection had been performed. We defined major complications as those that are reportable to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Database. These are summarized in appendix 1.

Technique

All CP operations were performed via a thoracotomy approach. During dissection of the pleural space and adhesiolysis, careful attention was paid to avoiding visceral pleural tears and the resulting pleural space contamination. Extrapleural dissection was performed as needed. Central control of hilar vessels was obtained early in the operation, often intrapericardially. Systematic lymph node sampling was performed for lung cancer patients. All bronchial stumps were kept as short as possible and reinforced with vascularized muscle tissue or pedicled mediastinal tissue including pericardial fat pad, thymus, or pericardium. The chest wall was closed in airtight fashion, and the pleural space drained with a balanced suction system for 24 hours. Patients were managed in an intensive care unit overnight and moved to a stepdown unit when clinically appropriate.

Data were managed using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test, matched ordinal data using Wilcoxon’s rank test and categorical data using a chi-square test. Kaplan Meier (product limit) graphs were used to demonstrate survival over time. Survival comparisons between groups of patients were completed using the Mantel-Haenszel log rank test. P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Between January 2000 and February 2011, of the 3382 lung resections at out institution, 211 were pneumonectomies unrelated to transplantation. Of these, 35 (17%) were completion pneumonectomies (CP), the remainder being one-stage primary pneumonectomy (PP) operations. Twenty-five of 211 (11.8%) pneumonectomy operations were performed for benign indications. Of these, 15 were primary pneumonectomies (Indication: subacute or chronic infection-9, inflammatory mass-3, others-3) while 10 were completion pneumonectomies (Indication: subacute or chronic infection-5, nonfunctioning lung with hemoptysis-3, postoperative subacute complications-2). Patients undergoing primary pneumonectomy were similar to patients undergoing CP in age, gender distribution, preoperative spirometry, and significant comorbidities. (Table 1) Primary pneumonectomy patients were more likely to have smoked cigarettes than patients undergoing CP. (Table 1) Patients undergoing CP were more likely to have a benign indication for surgery compared to those undergoing primary pneumonectomy (10/35, 29% vs. 15/176, 9%, p=0.001).

Table 1.

A comparison of preoperative variables in patients undergoing completion or primary pneumonectomy.

| Variable | Completion pneumonectomy (n=35) |

Primary pneumonectomy (n=176) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 59.9 ± 12.5 | 61.1 ± 12.7 P=0.062 |

0.62 |

| Female gender | 15 (43%) | 67 (38%) | 0.71 |

| Mean FEV1* (liters) | 2.09 ± 0.84 | 2.21 ± 0.71 | 0.42 |

| Hypertension | 13 (37%) | 74 (42%) | 0.58 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 4 (11%) | 24 (14%) | 0.79 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1 (3%) | 16 (9%) | 0.32 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 2 (6%) | 8 (5%) | 0.68 |

| Cigarette smoking | 25 (71%) | 150 (86%) | 0.03 |

| Mean Creatinine | 0.93 ± 0.29 | 0.93 ± 0.38 | 0.98 |

FEV1=Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second

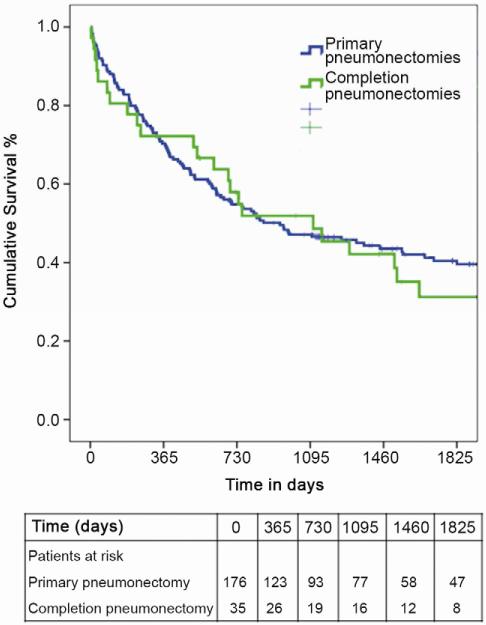

Major perioperative morbidity was seen in 21 of 35 (60%) patients undergoing CP and 4/35 (11%) patients died perioperatively. The incidence of major perioperative complications was not different between the CP and PP groups with regard to development of empyema and bleeding, however CP patients were noted to have a higher incidence of bronchopleural fistula and stroke postoperatively. (Table 2) The perioperative mortality for PP was 10/175 (5.7%), and was not significantly different from CP statistically (4/35, 11%). The long-term survival of patients undergoing completion pneumonectomy was similar to that of patients undergoing primary pneumonectomy (median 36.5 months versus 31 months, p=0.85). (Figure 1)

Table 2.

A comparison of early postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing completion or primary pneumonectomy.

| Variable | Completion pneumonectomy (n=35) |

Primary pneumonectomy (n=176) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchopleural fistula | 4 (11%) | 5 (3%) | 0.04 |

| Empyema | 2 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 0.19 |

| Bleeding | 0 | 3 (2%) | 1.00 |

| Stroke | 3 (9%) | 2 (1%) | 0.03 |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival of all patients undergoing pneumonectomy, stratified by primary versus completion pneumonectomy.

We compared 10 patients undergoing CP for benign indications to 25 patients with cancer as the indication for surgery. The two groups were similar in age, gender distribution, preoperative spirometry, significant comorbidities, and time between index operation and CP. (Table 3) All 10 patients undergoing CP for benign disease developed a major complication compared to 11/25(44%) with malignancy, p=0.002. The benign group showed a trend towards a higher incidence of postoperative bronchopleural fistula, and perioperative mortality. (Table 4) The incidence of postoperative empyema and hemorrhage was similar in the two groups. (Table 4)

Table 3.

Demographics and preoperative variables in patients undergoing completion pneumonectomy, stratified by indication for surgery.

| Variable | Benign (n=10) | Malignant (n=25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 55.8 ± 13.4 | 60.9 ± 12.0 | 0.27 |

| Female gender | 4 (40%) | 11 (44%) | 1.00 |

| Mean FEV1* | 2.22 ± 1.1 | 2.09 ± 0.73 | 0.76 |

| Hypertension | 3 (30%) | 9 (36%) | 1.00 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 1 (10%) | 2 (8%) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1 (10%) | 0 | 0.29 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1 (10%) | 1 (4%) | 0.50 |

| Tobacco use | 7 (70%) | 17 (68%) | 1.00 |

| Mean Creatinine | 0.79 ± 0.26 | 1.0 ± 0.29 | 0.07 |

| Mean elapsed time in years, index operation to CP |

7.0 ± 16.8 | 3.1 ± 3.1 | 0.48 |

FEV1=Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second

Table 4.

Early postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing completion pneumonectomy, stratified by indication for surgery.

| Variable | Benign (n=10) | Malignant (n=25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchopleural fistula | 3 (30%) | 1 (4%) | 0.06 |

| Empyema | 1 (10%) | 1 (4%) | 0.50 |

| Bleeding | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Stroke | 2 (20%) | 1 (4%) | 0.19 |

| Perioperative mortality | 3 (30%) | 1 (4%) | 0.06 |

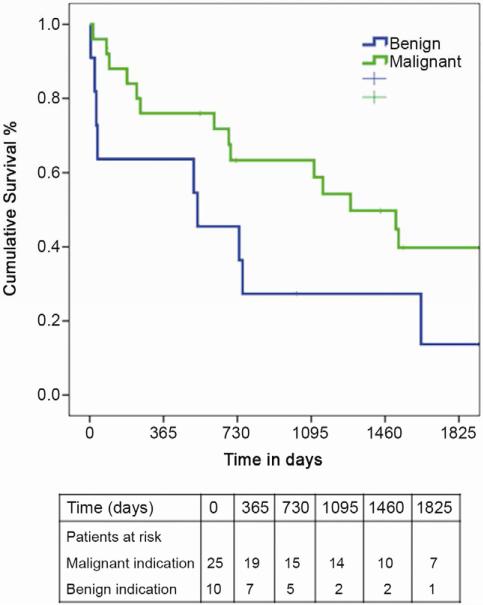

In univariate analysis of risk factors, postoperative bronchopleural fistula (BPF)(p=0.05) and benign indication for surgery (p=0.07) tended to be related to perioperative mortality. A bronchopleural fistula (4/35, 11%) was more likely to occur in patients undergoing CP shortly after the primary operation (time between initial lung resection and CP: 0.28 vs. 4.5 years; p=0.018) and a trend was seen toward a benign indication for operation (p=0.07). Median survival after CP for benign indications was 24.3 months and 36.5 months for malignancy (p=0.06). (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival of patients undergoing completion pneumonectomy, stratified by indication for surgery (benign versus malignant).

Comment

Completion pneumonectomy remains a highly morbid operation with a significant risk of perioperative mortality. Twenty-one of 35 (60%) of our patients had major complications and 4/35 (11%) died perioperatively. These results are similar to prior series of CP patients, several of them from the 1990’s.(1, 9, 10) Although one may anticipate that improvements in anesthetic techniques, perioperative critical care, and attention to respiratory therapy over the last decade may improve outcomes, our results likely reflect the issues of major surgery in a frail patient population.

As a group, we employ a conservative and highly selective approach towards pneumonectomy operations in general and completion pneumonectomy in particular. It is hard to reflect this selective approach in numbers, but our group performed 211 pneumonectomies during the study period and this constituted 6.3% of the 3,382 lung resections performed at our center. Other contemporary series have reported pneumonectomies being a higher proportion (15-20%) of lung resections performed in their respective settings.(11, 12) Every patient considered for completion pneumonectomy for cancer is discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor board to ensure that resection is the most appropriate treatment. Additionally, all the thoracic surgeons also contribute to this discussion to endorse or oppose the decision to operate. Patients undergoing CP are optimized preoperatively, even more rigorously than other lung resection candidates. This includes smoking cessation, ensuring optimal pulmonary rehabilitation, and appropriate preoperative antiinfective therapy for patients with benign indications. In spite of a selective and planned approach, we have not been able to demonstrate better outcomes than those in previous series. (Table 5)

Table 5.

Published series describing perioperative outcomes after completion pneumonectomy.

| Author | Study period |

N | Morbidity (%) |

Mortality (%) |

Five-year survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regnard(6) | 1972-97 | 80 | 25 | 5 | 70% benign, 36% cancer |

| Muysoms(3) | 1975-95 | 138 | 43 | 23.3 | 59% benign, 32% cancer |

| Miller(1) | 1985-98 | 115 | 70 | 21 | |

| Terzi(17) | 1982-2000 | 59 | 30 | 3.4 | 25% for R0 cancer resection |

| Fujimoto(4) | 1990-98 | 66 | 32 | 7.6 | 65% benign, 54% cancer |

| Jungraithmayr(2) | 1986-2003 | 86 | 37 | 20 | |

| Guggino(8) | 1989-2002 | 55 | 58 | 16.4 | 35% |

| Sirmali(18) | 1991-2006 | 23 | 44 | 0 | |

| Sherwood(16) | 1994-2003 | 26 | 46 | 23 | |

| Zhang(13) | 1988-2007 | 92 | 34 | 10 | 14% |

| Tabutin(14) | 1995-2009 | 46 | 56 | 15 | Median survival 30 months |

| Cardillo(9) | 1990-2009 | 165 | 56 | 10.5 | 37% |

| Current Study | 2000-11 | 36 | 61 | 11 | Median 24 months benign, 36 months cancer |

Surgical technique and the development of bronchopleural fistula (BPF) and resulting morbidity and mortality have been found to be key factors impacting outcomes of patients undergoing CP. (1, 2, 13) Despite this knowledge, bronchial stump reinforcement with a pedicled flap or coverage with adjacent tissue is not universally employed. (1, 4, 13-15) For our series, a relatively uniform technique was employed. Five of the 6 participating surgeons have been trained at our institution and the 6th surgeon (GAP) has been the mentor at our program for over 20 years. We utilized adjacent or regional pedicled tissue (mediastinal fat, pericardial fat, azygous vein, intercostal muscle, serratus muscle, or thymus) for covering all bronchial stumps, which were kept as short as possible. Of the 35 patients undergoing CP in our series, 18 had bronchial reinforcement with pericardium and pericardial fat pad (1 developed BPF), 12 with thymus and pericardial fat pat (1 developed BPF), and 5 with a chest wall muscle (2 developed BPF). Unfortunately the number of patients is too small to make meaningful statistical comparisons.

We noted that patients undergoing CP at a short interval after the index operation were more likely to develop a BPF and a trend was seen for benign indications being a risk factor for BPF. A similar trend for increased risk of perioperative septic complications including BPF was noted by Jungraithmayr et al (2) in patients who underwent CP soon after the index operation. This group includes patients who are undergoing CP for an acute or indolent complication after their initial operation, and are thus are more likely to suffer further morbidity. In this situation, CP is often the only treatment option for these patients.

Previous series of patients undergoing CP have not contrasted their patients with those undergoing primary one-stage pneumonectomy at the same programs. In our series, these two groups of patients had similar demographics, lung function tests, and comorbidities. Yet, we noted that perioperative mortality with CP (11%) was nearly double that seen in the primary pneumonectomy group although the differences were not statistically significant, likely due to the small sample size in the CP group. We also noted that patients undergoing CP for benign indications were more likely to have poorer short-term outcomes. Relatively few patients underwent primary pneumonectomy for benign indications (<9%) compared to nearly 30% of CP patients. This, along with the greater technical complexity of the procedure and the elevated risk of technical problems including bronchopleural fistula can explain some of the excess mortality in the CP cohort.

We noted a strong trend towards a higher risk of complications and perioperative mortality when CP was being performed for benign indications. Similar findings have been reported by other authors. (1, 16) Several factors can contribute towards this finding. Benign indications may include early postoperative complications after lung resection (like BPF, bronchovascular fistula etc.) that necessitate an urgent or emergent operation with its associated risk. Benign indications also encompass chronic bacterial and fungal infections; these patients are typically malnourished, have poor cardiopulmonary reserve, and usually have the most hostile pleural spaces, especially after a prior lung resection. Additionally, the hilar dissection is tedious in these patients. These technical factors often predict an extrapleural dissection, a prolonged operative time, and the almost certain need for multiple blood transfusions; all these are factors that predict increased perioperative morbidity. (16) In our series the risk of mortality in patients undergoing CP for cancer was indeed quite similar to the risk after primary pneumonectomy (4% vs. 5.6%). Similarly, the risk of postoperative BPF was 4% after CP for cancer and 3% in those undergoing primary pneumonectomy. These findings indicate that the excess postoperative morbidity and mortality after CP was mostly related to operations for benign indications.

Our paper has certain limitations. The analysis is based upon a retrospective evaluation of institutional data. Thus our study is subject to the inherent biases of a retrospective study, the most important of which is selection bias in treatment allocation. Additionally, we have employed a conservative and selective approach to CP, thus limiting our sample size. This limits our statistical analysis and introduces the possibility of type II error in the analysis, where true differences between groups may not become apparent due to sample size constraints. Lastly, the subjectivity of intraoperative decision-making and the management of the numerous perioperative complications that CP patients experience can lead to misclassification bias. We have sought to avoid underestimating the morbidity of the operations by adopting a stringent approach towards enumerating complications, preferring to classify an event as a complication if there was some doubt on chart review.

Conclusions

Despite a selective approach, CP remains a highly morbid operation particularly for benign indications. Perioperative morbidity and mortality after CP for cancer may approach outcomes for primary pneumonectomy. Rigorous preoperative optimization, ruling out contraindications to surgery and attention to technical detail are recommended.

Acknowledgement

Author Varun Puri is supported by NIH awards K12CA167540 and UL1 TR000448.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1.

Major complications considered reportable in the current study.

| Pulmonary |

|---|

| Chest Tube Air leak > 5 days |

| Atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy |

| Pleural Effusion Requiring Drainage |

| Pneumonia |

| ARDS |

| Respiratory Failure |

| Bronchopleural Fistula |

| Pulmonary Embolus |

| Pneumothorax requiring chest tube insertion |

| Initial Ventilator support >48 hours |

| Reintubation |

| Tracheostomy |

| Other major pulmonary event, specify |

| Cardiovascular |

| Atrial Arrhythmia requiring treatment |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia requiring treatment |

| Myocardial Infarction |

| Deep Vein Thrombosis requiring treatment |

| Other major Cardiovascular event, specify |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Gastric Outlet Obstruction |

| Ileus |

| Anastomotic Leak requiring treatment |

| Dilation of Esophagus prior to discharge |

| Other major GI event, specify |

| Hematology |

| PRBC transfusion post-operatively, specify number of units |

| Infection |

| Urinary Tract Infection |

| Urinary Retention requiring catheterization |

| Discharged With Foley catheter |

| Surgical Site infection, specify: |

| Organ space (i.e. empyema, mediastinitis) |

| Superficial |

| Deep |

| Sepsis |

| Other Infection requiring IV antibiotics, specify |

| Neurology |

| New Central Neurological Event |

| Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Paresis |

| Delirium Tremens |

| Other major Neurological event, specify |

| Miscellaneous |

| New Renal Failure per RIFLE criteria |

| Chylothorax requiring medical intervention |

| Other events requiring OR with General Anesthesia, specify |

| Anastomotic Leak following esophageal surgery |

| Bleeding |

| Chylothorax, reoperation requiring surgical ligation of thoracic duct |

| Empyema |

| Other |

| Unexpected Admission to ICU |

| Readmit 30Days after Discharge |

Appendix 2

Discussion

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Paper presented by Varun Puri, MD,

St. Louis, MO. puriv@wudosis.wustl.edu

Discussion by John A. Howington, MD,

Illinois

jhowington@northshore.org

Dr. J. Howington (Evanston, IL):

You mentioned one of the risk factors is the short interval between the lobectomy and the completion pneumonectomy. Were some of those patients in that series patients that had a BPF after a lobectomy at another institution and you had to go in and do a completion pneumonectomy as a salvage operation?

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Response by Varun Puri, MD, St. Louis, MO.

DR. PURI: One patient. That’s an excellent point that you bring up. When I reviewed the series from other institutions, that was a common scenario for early postoperative complications in the benign group, and we only had one individual with that particular situation. But, again, there are some individuals who undergo a lobectomy for destroyed lung from infectious issues, and if they go in early or within a few months of pneumonectomy, those tended to have a higher risk of complications.

DR. HOWINGTON: Then the next question, differentiating left side versus right side.

DR. PURI: In the risk factor analysis, laterality did not have any significant impact on the outcomes.

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Paper presented by Varun Puri, MD,

St. Louis, MO. puriv@wudosis.wustl.edu

Discussion by Mark J. Krasna, MD,

New Jersey

mkrasna@meridianhealth.com

Dr. M. Krasna (Neptune, NJ):

I enjoyed this series. It was a very good presentation. Just two questions. One is technical. You did use the word “local” autologous tissue and then at the end you talked about “vascularized” autologous tissue. Perhaps if you can be specific, did you use intercostal muscle bundles, did you use serratus anterior, or did you just rotate the pericardial fat pad?

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Response by Varun Puri, MD, St. Louis, MO.

DR. PURI: There was a combination of pericardial fat pad, serratus, intercostal muscle, thymus, and azygos vein. So these five tissues were utilized. And since there were only 35 individuals, there was a handful of patients in each of these categories.

DR. KRASNA: So I would propose, although the numbers obviously are so small, that perhaps one of the last recommendations is probably the most important. I think the idea of using a pedicled vascularized autologous tissue, namely, a muscle, probably a large muscle if you are using a completion pneumonectomy, especially for somebody with benign disease, is probably the safest thing. It does not take a lot of extra time, and often if the patient had a prior operation, especially on the same side, although you may have lost some muscle, usually the serratus anterior is intact.

Lastly, it seemed that you showed us univariate analyses and you showed us dichotomized variables, but you didn’t tell us if you had a multivariable analysis and you didn’t tell us whether you did matched cohorts. If you could just explain if you were able to take those 25 patients and compare them to a matched group from the primary group, I would be curious about your results.

DR. PURI: We did not do a matched comparison simply because the groups are significantly different, just based upon the indications for operation that are being performed. There were 10 individuals, or 30% of the patients, in the completion pneumonectomy group who had a benign indication, while only a small percentage, only 9% of the individuals in the larger group, had a benign indication. So it was next to impossible to match these two patient populations. Secondly, we only found one factor which leads to statistical significance in the univariate analysis, therefore a multivariate analysis was not called for.

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Paper presented by Varun Puri, MD,

St. Louis, MO. puriv@wudosis.wustl.edu

Discussion by Daniel L. Miller, MD,

Georgia

dlmill2@emory.edu

Dr. D. Miller (Atlanta, GA):

Very detailed presentation. Can you expand on how you handle the bronchus? I know that you showed a series from Mayo of which I was a co-author, in that series in the majority of cases we stapled the bronchus with a yellow heavy-wired stapler and used the serratus anterior muscle (SAM) for reinforcement, especially in people who received neoadjuvant radiation or had opportunistic infections such as Aspergillus. Did you look at which patients were at higher risk of BPF formation?

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Response by Varun Puri, MD, St. Louis, MO.

DR. PURI: The type of closure did not in this small series affect the risk of postoperative bronchopleural fistula. There were nearly an equal number of individuals who underwent a hand-closed or a simple suture closure of the stump versus a stapled closure. And again, like I said, in the 35 individuals, there would be five types of tissues that I just referred that had been utilized in various combinations.

DR. MILLER: And I would echo what Mark said. Go big or go home, you have to put a muscle with enough bulk to cover the stump as well as to ensure long term viability, especially after radiation. An intercostal muscle is just not as reliable long term as a SAM flap.

DR. PURI: Your paper was an excellent preparation for me to go to and see what all I wanted to put in mine. Thank you very much.

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Paper presented by Varun Puri, MD, St. Louis, MO. puriv@wudosis.wustl.edu Discussion by Russell R. Kraeger, MD, Missouri bkraeger@charter.net Dr. R. Kraeger (St. Louis, MO):

I just had two short questions for you, and I want to congratulate you on an excellent paper. One is, do you routinely leave a chest tube on these people, and the second question I have is, what was the incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in these people?

51. Completion Pneumonectomy: Do Outcomes Justify the Operation?

Response by Varun Puri, MD, St. Louis, MO.

DR. PURI: We routinely leave a chest tube for 24 hours in these individuals and take it out right away after that. The incidence of arrhythmias, if I remember off the top of my head, was 30% or so.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the Southern Thoracic Surgical Association meeting, Naples, FL, November 7-10, 2012

References

- 1.Miller DL, Deschamps C, Jenkins GD, et al. Completion pneumonectomy: factors affecting operative mortality and cardiopulmonary morbidity. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:876–883. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03855-9. discussion 883-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jungraithmayr W, Hasse J, Olschewski M, Stoelben E. Indications and results of completion pneumonectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muysoms FE, de la Riviere AB, Defauw JJ, et al. Completion pneumonectomy: analysis of operative mortality and survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1165–1169. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujimoto T, Zaboura G, Fechner S, et al. Completion pneumonectomy: current indications, complications, and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:484–490. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.112471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HS, I H, Choi YS, et al. Surgical resection of recurrent lung cancer in patients following curative resection. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:224–228. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regnard JF, Icard P, Magdeleinat P, et al. Completion pneumonectomy: experience in eighty patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen RM, Force SD, Pickens A, et al. Pneumonectomy for benign disease: analysis of the early and late outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guggino G, Doddoli C, Barlesi F, et al. Completion pneumonectomy in cancer patients: experience with 55 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardillo G, Galetta D, van Schil P, et al. Completion pneumonectomy: a multicentre international study on 165 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:405–409. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chataigner O, Fadel E, Yildizeli B, et al. Factors affecting early and long-term outcomes after completion pneumonectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:837–843. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riquet M, Berna P, Fabre E, et al. Evolving characteristics of lung cancer: a surgical appraisal. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:1019–1024. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezr189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorsteinsson H, Alexandersson A, Oskarsdottir GN, et al. Resection rate and outcome of pulmonary resections for non-small-cell lung cancer: a nationwide study from Iceland. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1164–1169. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318252d022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang P, Jiang C, He W, et al. Completion pneumonectomy for lung cancer treatment: early and long term outcomes. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;7:107. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-7-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabutin M, Couraud S, Guibert B, et al. Completion pneumonectomy in patients with cancer: postoperative survival and mortality factors. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1556–1562. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31826419d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haraguchi S, Koizumi K, Hirata T, et al. Surgical results of completion pneumonectomy. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:24–28. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.09.01502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherwood JT, Mitchell JD, Pomerantz M. Completion pneumonectomy for chronic mycobacterial disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terzi A, Lonardoni A, Falezza G, et al. Completion pneumonectomy for non-small cell lung cancer: experience with 59 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:30–34. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirmali M, Karasu S, Gezer S, et al. Completion pneumonectomy for bronchiectasis: morbidity, mortality and management. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:221–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]