Abstract

Flowering plants possess mechanisms that stimulate positive emotional and social responses in humans. It is difficult to establish when people started to use flowers in public and ceremonial events because of the scarcity of relevant evidence in the archaeological record. We report on uniquely preserved 13,700–11,700-y-old grave linings made of flowers, suggesting that such use began much earlier than previously thought. The only potentially older instance is the questionable use of flowers in the Shanidar IV Neanderthal grave. The earliest cemeteries (ca. 15,000–11,500 y ago) in the Levant are known from Natufian sites in northern Israel, where dozens of burials reflect a wide range of inhumation practices. The newly discovered flower linings were found in four Natufian graves at the burial site of Raqefet Cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel. Large identified plant impressions in the graves include stems of sage and other Lamiaceae (Labiatae; mint family) or Scrophulariaceae (figwort family) species; accompanied by a plethora of phytoliths, they provide the earliest direct evidence now known for such preparation and decoration of graves. Some of the plant species attest to spring burials with a strong emphasis on colorful and aromatic flowers. Cave floor chiseling to accommodate the desired grave location and depth is also evident at the site. Thus, grave preparation was a sophisticated planned process, embedded with social and spiritual meanings reflecting a complex preagricultural society undergoing profound changes at the end of the Pleistocene.

Keywords: burial customs, preburial preparation, radiocarbon dates

In the Mediterranean Levant, the earliest known burials involved disposal of the dead in sporadic and isolated pits dug in caves and their terraces. Such burial sites are known at the caves of Qafzeh, Skhul, Tabun, Amud, and Kebara, all dated to the latter half of the Middle Paleolithic, ca. 120,000–55,000 y ago (1–5). The bodies were usually interred in flexed positions, sometimes with selected animal parts placed on them. In all instances only a few individuals were buried at each site, likely reflecting intermittent burials. These sites were not cemeteries in the modern sense, where frequent, repetitive interment and memorial events take place at a specifically dedicated location, usually for generations.

Natufian [ca. 15,000–11,500 calibrated years (Cal.) B.P.] sites used for burial reflect a different pattern. To date, more than 450 skeletons have been unearthed in sites such as el-Wad Cave and Terrace, Eynan, Hayonim Cave and Terrace, Hilazon Tachtit Cave, Nahal Oren, and Raqefet Cave; these sites have several characteristics conceptually similar to modern cemeteries (6–18). At each, at least several dozen burials were found in a delineated and densely used area. The unprecedented density of graves and the great variety of inhumation practices in these sites represent some elaboration of earlier traditions and a wide variety of innovations. The new forms of burial include the combination of individual and multiple graves, flexed and full-length postures, patterned orientations, head and body decoration with beads, removal of the skull after body decomposition, use of ochre-based pigments, provisioning with grave goods and offerings, and possibly an association with funereal feasts (13, 19).

Materials and Methods

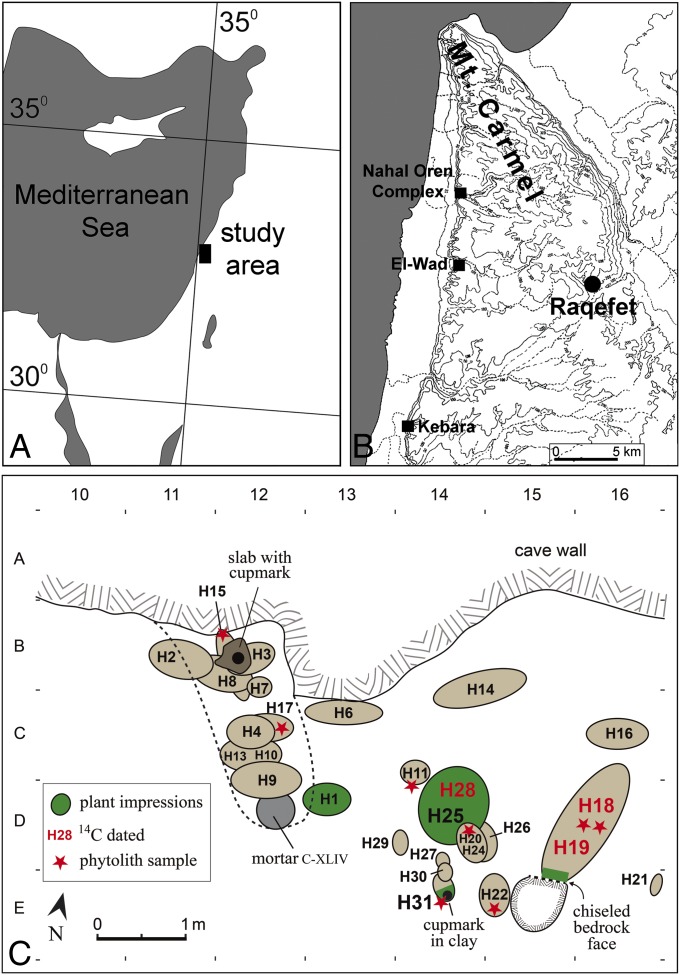

Here we report on the discovery of grave linings made of flowering plants in four radiocarbon-dated (13,700–11,700 Cal. B.P.) Natufian burials excavated at Raqefet Cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel (Figs. 1 A and B, 2, and 3; Figs. S1 S2, S3 and S4; and Table S1). Excavations at the site exposed 29 skeletons, all but one clustered in a small area (ca. 15 m2) (Fig. 1C). Although not suitable for all Natufian contexts, the term “cemetery” seems justified here, because frequent, repetitive interments took place at a specifically dedicated location, probably for at least several generations. The retrieved skeletons include infants, children, and adults (14, 15). Most of the burials were single interments, although four were double, in which two bodies were interred together in the same pit. In the double burials, deaths were certainly contemporaneous or almost so, because the burials are simultaneous. However, the cause of death (epidemic, accident, violence) is unknown, and in most such cases is never identified (10).

Fig. 1.

(A) Location map of Mt. Carmel. (B) Major Natufian sites in Mt. Carmel. (C) Plan of the Natufian burial area in the first chamber, Raqefet cave. See Fig. S3 for a section through graves Homo 28–Homo 31.

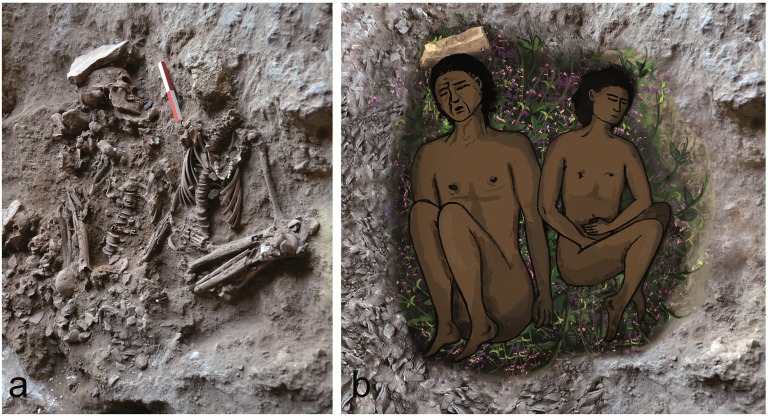

Fig. 2.

(A) Field photograph of skeletons Homo 25 (adult, on left) and Homo 28 (adolescent, on right) during excavation. Note the almost vertical slab behind the skull of Homo 25 and the missing skull of H28. Photograph reproduced with permission from E. Gernstein. (Scale bar: 20 cm.) (B) A reconstruction of the double burial at the time of inhumation. The skull of Homo 25 was displaced in the grave long after burial (A), but originally the head was facing upwards. The skull of Homo 28 was ritually removed months or years after burial. Note the bright veneer inside the grave on the right, partially covered by green plants.

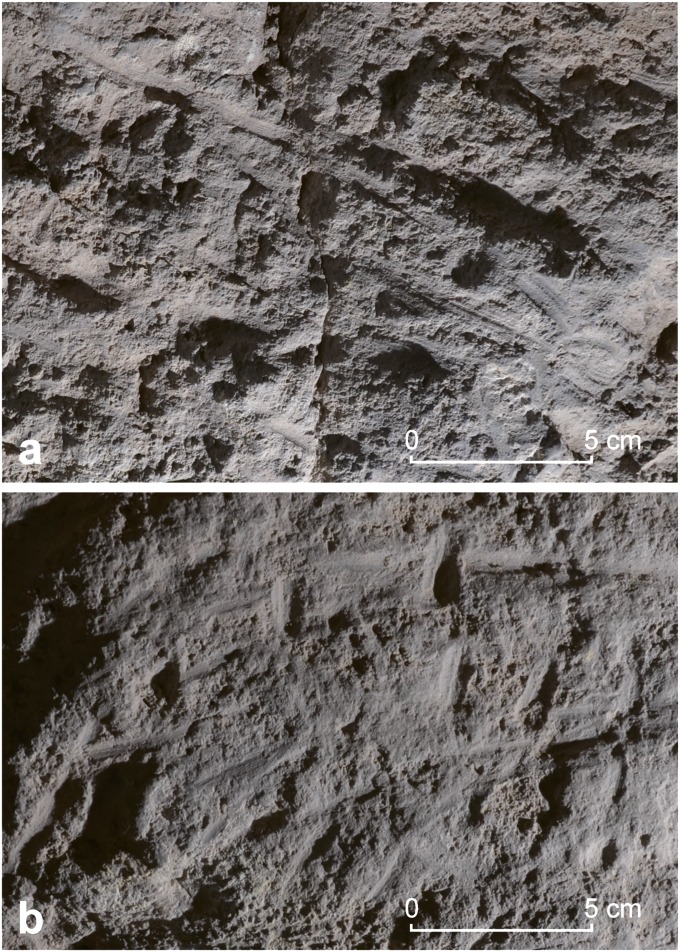

Fig. 3.

Photographs of plant impressions found at the bottom of graves. (A) Impressions under the skeletons of Homo 25 and Homo 28. The long impressions are of square stems. (B) Impressions under the skeleton of Homo 1. Note the short, parallel impressions of square stems crossing long stems (at the top center) and the Y-like branching stems (at the left). Photographs reproduced with permission from E. Gernstein.

The current study focuses on the analyses of plant impressions in four graves (Table S1). To document the complex formation processes in the Natufian graveyard, to refine the microstratigraphy, and to assess depositional and postdepositional processes, we collected sediment samples from all contexts in and around the graveyard for micromorphological studies (SI Text, section S1). We also sampled a wide array of deposits across the site for phytolith analysis (SI Text, section S2). These samples include 16 samples from eight burials, 12 samples from four bedrock mortars, and seven samples from other contexts and from naturally accumulating soils located away from the cave's entrance (Table S2).

Results

The graveyard deposits vary in thickness from ∼0.8 m in the concentration between Homo 9 and Homo 15 (Locus 1) to ∼0.6 m in the concentration of Homo 31 to Homo 28 (Fig. 1C and Fig. S3). In thin sections the grave fills appear as heterogenic calcareous ash deposits mixed with comminuted charcoal, bones, local soil, gravel, and snail shells (SI Text, section S1 and Fig. S5 A and B). The uppermost part of the anthropogenic deposits was strongly affected by bioturbation, manifested as a loose consistency, high porosity and crumbly structure (Fig. S5 C and D). Significantly, bioturbation acted mainly on a millimetric scale and decreased considerably with depth.

Several graves rest on hard limestone bedrock with a distinct upper layer altered by weathering into a porous, friable crust, 2–3 cm thick, that does not effervesce with diluted hydrochloric acid, upon which a mud veneer, 2–3 mm thick, is present. Micromorphological and scanning electron microscope (SEM)/energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analyses of the crust studied in the grave of Homo 25 and Homo 28 (SI Text, section S1 and Fig. S5 E–H) provide data regarding the microstructure, elemental composition, and postdepositional diagenesis of the initial calcite in the limestone bedrock. SEM observations show that the crust has an amorphous microstructure with fractures (Fig. S5 E–G). EDS measurements show that the crust is composed of a calcium-phosphorus mineral phase with ∼14% phosphorus by weight, indicating that initial calcite of the limestone rock has been largely replaced by hydroxyapatite. On a microscale level, the crust shows variations in chemical composition which appear as different shades of gray (Fig. S5G). However, EDS measurements in both brighter and darker areas are similar and apparently reflect the presence of two different mineralogical phases; one is a phosphate mineral phase, and the other is an alumosilicate phase revealed by peaks of silicon, aluminum, and potassium (Fig. S5H).

The presence of alumosilicates is probably the result of a mud veneer on the phosphatic crust. Preservation conditions hamper full characterization of the veneer and its postulated plaster-like utilization. A mud plaster was found lining the inside of a Late Natufian grave at Hilazon Tachtit (12, 13). The veneer at Raqefet Cave contains impressions of stems, leaves, and fruits and hence must have been damp and in a plastic state during the burial event or immediately thereafter, allowing soft delicate plant tissues to leave their precise impressions.

The largest number of preserved plant impressions was discovered in the double burial of Homo 25 and Homo 28 (Figs. 1C, 2, and 3; Figs. S1 B–D and S3; and Table S1). The two skeletons were found lying on their backs, parallel to each other with their elbows juxtaposed. One was a 12- to 15-y-old adolescent (Homo 28) placed with the knees folded to the left. The skull was ritually removed from the grave at a later time, after flesh decomposition. Homo 28 has been directly radiocarbon dated to 12,550–11,720 Cal. B.P. (Table S1 and Fig. S6). Homo 25 was an individual over 30 y old placed with his knees folded to his right. This individual had a stone slab set vertically behind the head, which was facing upwards. The head and slab were naturally dislocated in the grave and fell on their side, after body decomposition (Fig. 2).

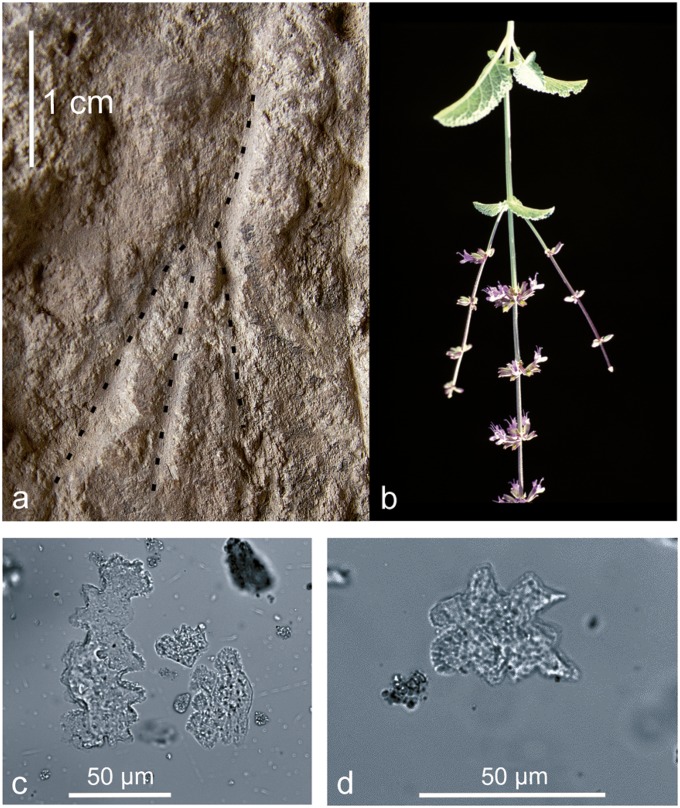

At the base of the grave we recorded more than 30 impressions; we identified 13 stem impressions, 3–15 cm long and 0.5–2 cm wide, with rectangular cross-sections and visible longitudinal veins preserving stem vascular bundles (Fig. 3A and Figs. S1 B–D, S2, and S3). One set of impressions was identified as the flowering stems of Salvia judaica Boiss. (Judean sage) (Fig. 4A) based on the size and angles between the branching stems (Fig. 4B). Other rectangular stems belong to sage and closely related species of the mint family (Labiatae) or to the figwort family (Scrophulariaceae). Species of these families currently grow on the terrace and slopes below the cave. Local plants of these families flower in spring; most have a strong, aromatic fragrance, and some possess medicinal properties. The stems become stiff in April–May and begin to deteriorate after desiccation during the summer. Thus, the impressions on the veneer were formed before midsummer. Additional impressions in this grave include stems with a round cross-section; three wide leaves, 5 cm in length, likely of trees; a row of five small impressions with a close morphological affinity to seeds of Cercis silliquastrum L. (Judas tree) and small (<3 mm), round impressions of unidentified seeds.

Fig. 4.

(A) Impressions of flowering stems in the grave of Homo 25 and Homo 28, marked by dashed lines. Photograph reproduced with permission from E. Gernstein. (B) Flowering stems of Salvia judaica, presented in the same scale and orientation as the impressions in the grave. Photograph reproduced with permission from A. Danin. (C and D) Jigsaw-puzzle phytoliths indicating tissue of a dicot plant. These phytoliths are associated with the graves and are also found in Salvia species growing near the cave today. Photographs reproduced with permission from R. Power.

The double grave of Homo 18 and Homo 19 is unique because it preserves data regarding a preparation phase preceding the floral lining. Here, a bedrock bulge on the cave floor was chiseled to serve as an inner wall of the grave. The chiseled surface is ca. 40 × 40 cm in area, creating an almost vertical plane, whereas the rest of the bedrock in the cave is usually undulating and has a different color (Fig. S4 A and B). Only after the modification of the rock were the veneer and plant lining set inside, as indicated by the impressions of reeds (Phragmites?) and other species found on the thin vertical veneer (Fig. S4C).

We identified another dense set of impressions at the base of the Homo 1 grave; it was exposed 40 y ago, although at the time the impressions were not observed (14). Here, there are several examples of square stems crossing each other at right angles and in regular intervals, seemingly in a loose net-like arrangement of the lining (Fig. 3B). Impressions of stems with round cross-sections were exposed immediately under the skeleton of a child (Homo 31) (Fig. 1C and Figs. S1A and S3). Apparently, the practice of lining graves with flowers was not age-related, according to the Raqefet burials. This finding is not surprising; when children were not excluded from the rest of the dead community (usually they were), their treatment did not substantially differ from that of the adults (10).

The plant impressions were restricted to the burial area. No similar remains were observed elsewhere on the cave floor or cave walls. Furthermore, no flint, stone, or bone impressions were found in the graves despite the presence of thousands of these hard and durable artifacts within the grave fills. This finding suggests that the green lining was thick and continuous, covering the entire grave floor and sides, preventing other objects from leaving impressions on the mud veneer.

The abundance of phytoliths recovered from eight graves provides additional evidence for the habitual use of plants in the Raqefet Cave burials (Fig. 4 C and D). Phytoliths were identified in 35 contexts in the cave and on its terrace, including control samples. They consist of morphotypes from grasses, dicotyledon leaves, reeds, and sedges. The average density of samples from the eight graves is 61,199 phytoliths per gram of sediment, whereas the average for the off-site control samples is only 27,231 per gram. The eight grave samples produced 91% of all jigsaw dicotyledon phytoliths even though these contexts produced only 38% of all phytoliths (SI Text, section S1, Tables S2–S4, and Fig. S7). The density of dicot phytoliths found in graves at Raqefet Cave is unique for phytolith concentrations at Natufian sites and supports the suggested use of large quantities of shrubs in the burials. Our recent study (summer 2012) revealed that phytoliths of local Lamiaceae species (including Salvia fruticosa) fall morphologically within the group of dicotyledonous phytolith morphotypes and thus may be one of the taxa used as grave lining at the Raqefet Cave burials (Fig. 4 C and D).

Direct 14C dates of bone collagen (extracted from three human skeletons) are now available for two double graves. The Homo 18 and Homo 19 skeletons produced a range of 13,700–13,000 Cal. B.P. The Homo 28 skeleton was dated to 12,550–11,720 Cal. B.P. (Fig. S7). The dates indicate that the site was used for burial, repeatedly, in the same confined area and with the same customs and grave preparation, likely for as long as about 2,000 y. The characteristics of the burial customs (6, 14), the flint assemblage (15), and the bedrock mortars accord with these dates. Indeed, the site was used as a graveyard for many generations, during which inhumation practices that included plant lining did not change.

The burial pits contained abundant material remains. In many burials worked and natural stone objects were set on edge, perhaps as markers or symbols. Flints and butchered animal bones were very common. The low frequency of trampling, burning, and carnivore gnawing marks on the animal bones suggest instant burial of food remains during interment, as would be expected in funerary feasting. Abundant bedrock mortars and cup marks were hewn in the cave floor adjacent to the graves (15), and one human skeleton was found resting on the rim of a large bedrock mortar. This finding suggests that at least some mortars functioned in conjunction with the burials.

Discussion

The Raqefet Cave plant impressions and phytoliths provide evidence for the earliest known use of plant lining in grave preparation. Earlier examples of plant lining are limited to utilitarian grass beddings found at Middle Stone Age/Middle Paleolithic Sibudu Cave (20), Misliya Cave (21), and Tor Faraj rockshelter (22), where the lining was identified as thin laminar layers containing abundant phytoliths and other microscopic plant remains. The oldest macroscopic lining remains yet identified were found on brush hut floors at Ohalo II (23,000 y ago), where grass bedding composed of large bundles of Puccinellia convoluta was exposed and analyzed (23). The finds from Raqefet Cave indicate that 13,700–11,700 y ago the Natufians lined graves with a soft mud veneer and then placed on the veneer a thick cover of fresh flowering plants, thereby providing color and aromatic fragrance. Claims for earlier use of flowers in the Shanidar IV Neanderthal burial (Iraq) were based on concentrations of microscopic pollen grains found adjacent to the skeleton (24, 25). However, the presence of rodent burrows, the abundant remains of jird (Meriones crassus) bones in the same layer, and this rodent’s habit of storing seeds and flower heads in its burrows cast serious doubts on this interpretation (26).

Natufian grave preparation at Raqefet Cave included three basic patterns. The first was the creation of a pit in either Middle Paleolithic or Natufian deposits. In several cases Natufian pits were dug successively in the same location, with the later ones disturbing earlier ones (Fig. 1C and Fig. S3). These pits were dug in loose deposits and then were filled with sediments from the immediate surroundings (Fig. S5 A–D). This pre-Natufian tradition was practiced for millennia and was very common at Raqefet Cave and many other Natufian burial sites (1, 2, 6, 9, 10, 16, 17).

The second pattern was the chiseling of bedrock to accommodate the desired grave. The Natufian skills of high-quality rock and stone carving are well demonstrated by bedrock and stone mortars (27–29) and by aesthetic and symbolic objects such as figurines and decorative designs (16, 30, 31). At Raqefet Cave there is direct evidence for bedrock chiseling in the graveyard as part of grave preparation. In one case the result was a vertical surface against which the foot of Homo 19 rested (Fig. S4). Rather than simply being a part of the physical setting of the grave pit, this chiseled surface may have had a symbolic meaning. Stones set vertically are very common in burials (e.g., Homo 25; see also Fig. S3) and even occur in bedrock mortars at Raqefet Cave (27).

The third pattern was the lining of the pit with a thick layer of green plants, including flowering species renowned for their aromatic fragrance and bright colors. This lining may have been the practice for all burials at the site, although remains were preserved only in some of the graves resting directly on bedrock. The lining practice appears to have taken place regardless of age and sex, in single and double burials. It may have been common in other Natufian sites, although such remains could be preserved for millennia only in particular conditions. Naturally, all three patterns of grave preparation could have been combined, as was the case for the Homo 18–Homo 19 grave.

Experimental studies have demonstrated flowers’ significant role as external sources of emotional stimuli, with measurable positive impacts on human social function (32). Flowers can be used to express sympathy, pride, and joy (33). They also are used to express religious feelings; in some religions flowers are considered the direct route for spiritual communication (34). These relationships may benefit fitness in both humans and flowers and have been linked to the domestication of certain species of flowering plants more than 5,000 y ago (32, 35). At a significantly earlier period, the use of flowers in social events (funerals) may have served as yet another means for enhancing group identity and solidarity. The Natufian development of group-specific burials and related practices likely reduced social tensions and improved group cohesion in a period of fluctuating environmental conditions, increasing population density, and growing social conflicts (6–11, 36, 37). The emergence of Natufian cemeteries, such as those at Raqefet Cave and Hilazon Tachtit Cave, also may represent new and complex social organizations which could have included the establishment or strengthening of special interest groups, inheritance of corporate property, territorial ownerships, and aspects of social organization (6–11, 12, 13, 19).

The careful preparation of the graves and the common use of flowers add yet another perspective to Natufian funerary rites and their impact on the participants in a way that is familiar among many modern cultures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Bar-Oz, A. Belfer-Cohen, L. Conyers, S. Filin, I. Hershkovitz, D. Kaufman, G. Lengyel, M. Weinstein-Evron, A. Weisskopf, and D. Bruggeman for their support, comments and advice; R. Shafir and T.R. Sevi for laboratory and field assistance; E. Mintz for help in sample preparation; and A. Lambert and G. Bosset, who also assisted in field work. Digital figures were prepared by A. Regev. Photographs were taken by E. Bartov (Fig. S4B), A. Danin (Fig. 4B), R. Power (Fig. 4 C and D), M. Eisenberg (Fig. S2 C and D), and E. Gerstein (Figs. 2A, 3AB. 4A, S1 A, B, C, and D, S2 A and B, S3 A and C). Field work was conducted under permits from the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. This project was supported by Grant 8915-11 from the National Geographic Society, Grant 7481 from the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and the Irene Levi-Sala CARE Foundation. Radiocarbon dating was funded by Grant 475/10 from the Israel Science Foundation (to E. B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1302277110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Vandermeersch B. 1981. Les Hommes Fossiles de Qafzeh (Israel) [The Fossil Humans of Qafzeh (Israel)] (Centre National de la Recherche Scietifique, Paris). French.

- 2.Garrod DAE, Bate DMA. The Stone Age of Mount Carmel. Oxford, UK: Clarendon; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Yosef O, Callander J. The woman from Tabun: Garrod’s doubts in historical perspective. J Hum Evol. 1999;37(6):879–885. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1999.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovers E, Kimbel WH, Rak Y. The Amud 7 skeleton—still a burial. Response to Gargett. J Hum Evol. 2000;39(2):253–260. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1999.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bar-Yosef O, et al. The excavations in Kebara cave, Mt. Carmel. Curr Anthropol. 1992;33:497–550. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bocquentin F, et al. De la récurrence à la norme: Interpréter les pratiques funéraires en préhistoire [From repetition to norm: Interpreting prehistoric funerary practices] Bull Mem Soc Anthropol Paris. 2010;22:157–171. French. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bar-Yosef O. The Natufian culture in the Levant, threshold to the origins of agriculture. Evol Anthropol. 1998;6:159–177. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd FB, Monahan CM. Death, mortuary ritual, and Natufian social structure. J Anthropol Archaeol. 1995;14:251–287. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein-Evron M. Archaeology in the Archives. Unveiling the Natufian Culture of Mount Carmel. Boston: Brill; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bocquentin F. 2003. Pratiques funéraires, paramèters biologiques et identitiés culturelles au Natoufien: une analyse archéo-anthropologique [Burial Practices, Biological Factors and Cultural Identities During the Natufian Period: A Bio-Archaeological Perspective]. PhD thesis. (Université Bordeaux 1, Talence, France). French. Available at http://grenet.drimm.u-bordeaux1.fr/pdf/2003/BOCQUENTIN_FANNY_2003.pdf.

- 11.Grosman L. Preserving cultural traditions in a period of instability: the Late Natufian of the hilly Mediterranean zone. Curr Anthropol. 2003;44:571–580. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosman L, Munro ND, Belfer-Cohen A. A 12,000-year-old Shaman burial from the southern Levant (Israel) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(46):17665–17669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munro ND, Grosman L. Early evidence (ca. 12,000 B.P.) for feasting at a burial cave in Israel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(35):15362–15366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001809107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lengyel G, Bocquentin F. Burials of Raqefet Cave in the context of the Late Natufian. J Isr Prehist Soc. 2005;35:271–284. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadel D, et al. The Raqefet Cave 2008 excavation season. J Isr Prehist Soc. 2009;39:21–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrot J. Le Gisement Natoufien de Mallaha (Eynan), Israel. Anthropologie. 1966;70:437–484. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belfer-Cohen A. The Natufian graveyard in Hayonim Cave. Paléorient. 1988;14:297–308. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stekelis M, Yizraely T. Excavations at Nahal Oren. Isr Explor J. 1963;13:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayden B. In: Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. Feasting Rituals in the Prehistoric Societies of Europe and the Near East. Jiménez GA, Montón-Subías S, Sánzhez-Romero M, editors. Oxford, UK: Oxbow; 2011. pp. 30–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg P, et al. Bedding, hearths, and site maintenance in the Middle Stone Age site of Sibudu cave, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Archaeol Anthropol Sci. 2009;1:95–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstein-Evron M, et al. A Window into Early Middle Paleolithic human occupational layers: Misliya Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel. Paleoanthropology. 2012;2012:202–228. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen AM. In: Neanderthals in the Levant: Behavioral Organization and the Beginnings of Human Modernity. Henry DO, editor. London: Continuum; 2003. pp. 156–171. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadel D, et al. Stone Age hut in Israel yields world’s oldest evidence of bedding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(17):6821–6826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308557101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leroi-Gourhan A. The flowers found with Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal burial in Iraq. Science. 1975;190:562–564. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solecki RF. Shanidar the First Flower People. New York: Knopff; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sommer JD. The Shanidar IV 'Flower Burial': a reevaluation of Neanderthal burial ritual. Camb Archaeol J. 1999;9:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadel D, Lengyel G. Human-made bedrock holes (mortars and cupmarks) as a Late Natufian social phenomenon. Archaeology, Anthropology and Ethnology of Eurasia. 2009;37(2):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nadel D, Rosenberg D, Yeshurun R. The deep and the shallow: The role of Natufian bedrock features at Rosh Zin, Central Negev, Israel. Bull Am Schools Orient Res. 2009;355:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadel D, Rosenberg D. New insights into Late Natufian bedrock features (mortars and cupmarks) Eurasian Prehistory. 2010;7(1):65–87. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinstein-Evron M, Belfer-Cohen A. Natufian figurines from the new excavations of the El-Wad cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel. Rock Art Research. 1993;10(2):102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards PC. 1991. in The Natufian Culture in the Levant, eds Bar-Yosef O, Valla FR, (International Monographs in Prehistory, Archaeological Series 1, Ann Arbor), pp 123–148.

- 32.Haviland-Jones J, Rosario HH, Wilson P, McGuire TR. An environmental approach to positive emotion: Flowers. Evol Psychol. 2005;3:104–132. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heilmeyer M. The Language of Flowers: Symbols and Myths. New York: Prestel; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenta N. From other lands: the use of flowers in the spirit of the liturgy. Orate Fratres. 1930;4(11):462–469. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollan M. The Botany of Desire. New York: Random; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A. The origins of sedentism and farming communities in the Levant. J World Prehist. 1989;3:447–498. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bar-Yosef O. In: Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Evolution and Sustainability. Gepts P, et al., editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2012. pp. 57–91. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.