Abstract

Background and Aims

Cell wall pectins and arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) are important for pollen tube growth. The aim of this work was to study the temporal and spatial dynamics of these compounds in olive pollen during germination.

Methods

Immunoblot profiling analyses combined with confocal and transmission electron microscopy immunocytochemical detection techniques were carried out using four anti-pectin (JIM7, JIM5, LM5 and LM6) and two anti-AGP (JIM13 and JIM14) monoclonal antibodies.

Key Results

Pectin and AGP levels increased during olive pollen in vitro germination. (1 → 4)-β-d-Galactans localized in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell, the pollen wall and the apertural intine. After the pollen tube emerged, galactans localized in the pollen tube wall, particularly at the tip, and formed a collar-like structure around the germinative aperture. (1 → 5)-α-l-Arabinans were mainly present in the pollen tube cell wall, forming characteristic ring-shaped deposits at regular intervals in the sub-apical zone. As expected, the pollen tube wall was rich in highly esterified pectic compounds at the apex, while the cell wall mainly contained de-esterified pectins in the shank. The wall of the generative cell was specifically labelled with arabinans, highly methyl-esterified homogalacturonans and JIM13 epitopes. In addition, the extracellular material that coated the outer exine layer was rich in arabinans, de-esterified pectins and JIM13 epitopes.

Conclusions

Pectins and AGPs are newly synthesized in the pollen tube during pollen germination. The synthesis and secretion of these compounds are temporally and spatially regulated. Galactans might provide mechanical stability to the pollen tube, reinforcing those regions that are particularly sensitive to tension stress (the pollen tube–pollen grain joint site) and mechanical damage (the tip). Arabinans and AGPs might be important in recognition and adhesion phenomena of the pollen tube and the stylar transmitting cells, as well as the egg and sperm cells.

Keywords: arabinogalactan protein, cell wall, Olea europaea, pectin, pollen, pollen tube

INTRODUCTION

Sexual reproduction in seed plants begins when the pollen grain (male gametophyte) lands on the surface of a compatible stigma, where it hydrates and resumes its metabolism. Then, a pollen tube emerges through the pollen aperture, which is guided through the style by chemical clues from the female tissue to the ovary (Johnson and Lord, 2006). Within the ovary, the pollen tube enters a receptive ovule through the micropyle, and delivers the male gametes within the embryo sac (female gametophyte) to carry out fertilization.

Pollen tubes are fast-growing cells exhibiting polar growth at their apex (Hepler et al., 2001). Pollen tube growth is driven by the rapid and continuous secretion of Golgi-derived vesicles, which dock and fuse with the plasma membrane at the pollen tube tip, providing new plasma membrane and cell wall precursors. Pollen tube cell walls differ in both structure and function from those of somatic plant cells (Geitmann and Steer, 2006). At the tip, the pollen tube wall is formed by a primary wall, mainly composed of newly synthesized pectins. This primary wall forms the outer layer of the cell wall in the pollen tube shank, where a secondary callose wall is deposited adjacent to the plasma membrane (Geitmann and Steer, 2006). The content of cellulose in pollen tubes is remarkably low and the subcellular localization varies depending on the species (Schlüpmann et al., 1994). Thus, in tobacco pollen tubes, cellulose co-localized with callose (Ferguson et al., 1998), but this may not be so for other species (Heslop-Harrison, 1987). The pollen tube wall dynamics are an important feature in the success of fertilization, displaying multiple functions: physical control of pollen tube shape, protection of male gametes against mechanical damage, adhesion of the pollen tube to the pistil transmitting tissue and resistance against the turgor pressure (Geitmann and Steer, 2006).

Pectins constitute a family of complex galacturonic acid-rich polysaccharides with uncertain supramolecular organization classified into four groups: homogalacturonans (HGs), type I (RG-I) and II rhamnogalacturonans (RG-II), and xylogalacturonans (Mohnen, 2008). In the pollen tube apex, pectins are secreted as highly methyl-esterified compounds (Li et al., 1994). Cell wall maturation during pollen tube growth is accompanied by the shifting of esterified pectins from the apex to the sub-apical region, where they undergo de-esterification by the action of pectin methylesterase enzymes (Li et al., 2002; Bosch et al., 2005). De-esterification allows Ca2+ ions to cross-link the carboxyl groups of HGs to form pectates, strengthening the pollen tube cell wall and increasing its resistance against mechanical stress (Jarvis, 1984; Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993). Therefore, the gelling ability of pectins may be important for the regulation of the pollen tube growth process.

Pollen tube cell walls also contain several proteins including arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) (Li et al., 1992; Mogami et al., 1999). AGPs are hydroxyproline-rich proteins that exhibit a high degree of O-glycosylation. The carbohydrate moiety mainly consists of large polymers of d-galactose and l-arabinose that typically account for >90 % (w/w) of the mass of the glycoprotein (Nothnagel, 1997). The glycan composition varies greatly between species and can be developmentally regulated within the same organ in different cell types (Pennell et al., 1991; Suárez et al., 2013). Moreover, carbohydrate motifs of AGPs might take different spatial conformations that modulate AGP functionality (Showalter, 2001). AGPs are also a major component of the extracellular matrix of the stigma and style secretory cells (Jauh and Lord, 1996; Losada and Herrero, 2012; Suárez et al., 2013). Several possible functions have been suggested for AGPs, including pollen tube adhesion and guidance, and pollen nutrition and recognition (Jauh and Lord, 1996; Chen and Ye, 2007).

While HGs have been widely studied in the pollen tube wall (Li et al., 1994; Jauh and Lord, 1996; Mogami et al., 1999; Dardelle et al., 2010), the map of other well-defined RG and AGP epitopes is far from being completed. Moreover, the cellular localization of certain AGPs is still a matter of debate (Li et al., 1992; Jauh and Lord, 1996; Coimbra et al., 2007). This study provides novel information about the time-course and spatial distribution of several pectin and AGP epitopes in olive (Olea europaea L.) pollen at different stages of pollen germination. Their putative functions in the context of pollen–pistil interaction are also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Olive (Olea europaea L. cv. ‘Picual’) mature pollen grains were collected during the months of May–June from dehiscent anthers by vigorous shaking of flowering shoots inside large paper bags. Sampling was carried out from discrete trees of the olive germplasm collection at the Estación Experimental del Zaidín in Granada (Spain). Pollen samples were sieved through an appropriate set of meshes to remove floral debris and stored at –80 °C until use.

In vitro germination of olive pollen

Pollen samples were pre-hydrated by incubation in a humid chamber at room temperature for 30 min and then transferred to Petri dishes (0·1 g per dish) containing 10 mL of germination medium [10 % (w/v) sucrose, 0·03 % (w/v) Ca(NO3)2, 0·01 % (w/v) KNO3, 0·02 % (w/v) MgSO4 and 0·01 % (w/v) boric acid] and incubated at room temperature in the dark. Pollen grains were sampled after hydration and 3 h after the onset of the culture.

Pectin and AGP extraction

Pectins and AGPs were extracted from mature (MP), hydrated (HP) and germinated (3 h) pollen samples (0·1 g each) as described by Suárez et al. (2013). The protein content was determined in triplicate from three independent extractions (n = 9) following the method of Bradford (1976), using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard. The carbohydrate content for each sample (n = 9) was assayed following the phenol–sulfuric acid method (Dubois et al., 1956), using d-glucose as standard. Finally, the AGP content for each sample (n = 9) was estimated as previously described (Lu et al., 2001) using gum arabic (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) as standard.

SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting

SDS–PAGE was performed according to Laemmli (1970). A 25 µg aliquot of proteins per sample were loaded in 10 % (w/v) polyacrylamide gels with 4 % stacking gels using a Mini-Protean 3 apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Blotting was carried out on polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes using a Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each membrane was blocked overnight at 4 °C in a solution containing 3 % (w/v) BSA in a Tris-buffered saline (TBS) solution (pH 7·4). Immunodetection of pectins was carried out by incubation with JIM5, JIM7, LM5 or LM6 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (Table 1) diluted 1:20 in TBST buffer [TBS solution containing 0·3 % (v/v) Tween-20], for 12 h at 4 °C in the dark, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), diluted 1:1000 in TBST, as above. The signal was detected in a Pharos FX molecular imager (Bio-Rad). Densitometric analyses of band intensities were carried out using the Quantity One v.4.6.2 software (BioRad). The resulting data were initially expressed as the ‘adjusted volume’ values (intensity mm2) delivered by the software, and then plotted as relative percentages referred to the highest value of the series using the SigmaPlot v.11 software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). The densitometric data were plotted referred to both total protein and carbohydrate (or AGP) contents loaded on the gels. AGPs were immunodetected using JIM13 and JIM14 mAbs as above. Negative controls were performed by omitting the primary mAb from the reaction. Primary antibodies were purchased from PlantProbes (Leeds, UK).

Table 1.

Antibodies used for pectin and AGP detection in olive pollen

| Antibody | Epitope | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| JIM7 | High methyl-esterified epitopes of homogalacturonan (HG) | Willats et al. (2000) |

| JIM5 | Low methyl-esterified epitopes of HG and unesterified HG | Willats et al. (2000) |

| LM5 | [(1 → 4)-β-d-galactose]4 | Jones et al. (1997) |

| LM6 | [(1 → 5)-α-l-arabinose]5 | Willats et al. (1998) |

| JIM13 | β-d-GlcpA-(1 → 3)-α-d-Galp A-(1 → 2)-l-Rha* | Yates et al. (1996) |

| JIM14 | Unknown | Yates et al. (1996) |

* This trisaccharide is part of the epitope but not the full epitope.

Whole-cell immunodetection of pectins and AGPs

Mature, hydrated and germinated pollen samples were fixed in a mixture of 4 % (w/v) paraformaldehyde and 0·25 % (v/v) glutaraldehyde prepared in 0·1 m cacodylate buffer (pH 7·2), for 2 h at 4 °C in the dark. Samples were then washed twice in cacodylate buffer and blocked in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (pH 7·2) containing 5 % (w/v) BSA. Detection of pectins and AGPs was carried out by incubation with the primary mAb (JIM5, JIM7, LM5, LM6, JIM13 or JIM14), diluted 1:20 in blocking buffer for 4 h at 4 °C in the dark. After washing steps in PBS (3× 15 min each), a secondary anti-rat IgG Alexa 488-conjugated antibody, diluted 1:100 in PBS buffer, was added for 1·5 h as above. Finally, samples were resuspended in the anti-fading solution Citifluor (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and examined with a Nikon C1 confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using an argon (488 nm) laser. Z-series images were collected and processed with the software EZ-C1 Gold version 2·10 build 240 (Nikon). Further treatment of images was made by using the Easy 3-D tool of the Imaris v4.0.6 software (Andor Technology, Zurich, Switzerland). In all images, the fluorescent labelling appears in green, whereas red colour represents autofluorescence (mainly located in the pollen exine). Negative controls were treated as above, but the primary antibody was omitted.

Immunogold labelling of pectins and AGPs

For transmission electron microscope analysis, mature, hydrated and germinated pollen samples were incubated with a fixative solution as above for 24 h. Samples were washed twice in cacodylate buffer, dehydrated in an ethanol series and embedded in Unicryl resin (BBInternational, Cardiff, UK) at –20 °C using UV light. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut on an Ultracut microtome (Reichert-Jung, Germany) and mounted on 200 mesh formvar-coated nickel grids. Blocking of non-specific binding sites was carried out by incubating sections for 4 h in a solution containing 1 % (w/v) BSA in PBS. This step was followed by incubation with the primary mAb (JIM5, JIM7, LM5, LM6, JIM13 or JIM14), diluted 1:5 in PBS with 1 % BSA, for 3 h. Samples were then rinsed with PBS and incubated with an anti-rat IgG 15 nm gold-conjugated antibody (BBInternational), diluted 1:50 in PBS with 1 % BSA, for 2 h. After washing, sections were stained with 5 % (w/v) uranyl acetate for 30 min followed by lead citrate for 15 min. Observations were carried out in a JEM-1011 transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan). Control reactions were carried out by omitting the primary antibody.

RESULTS

Pectin profiling in the olive pollen during germination

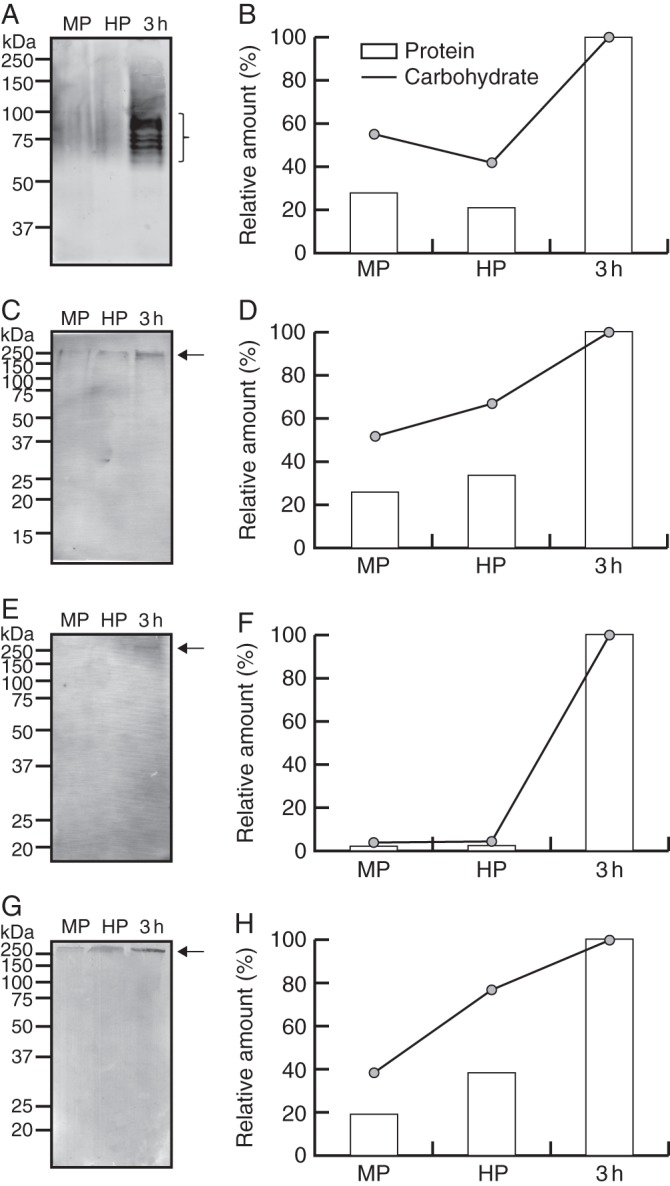

We first carried out immunoblot analyses to determine the quantitative and qualitative changes in pectin profiles during olive pollen in vitro germination. Total protein, carbohydrate and AGP contents were estimated for each developmental stage analysed. The average carbohydrate (μg)/protein (μg) ratios were 28·4 ± 3·9, 25·9 ± 4·7 and 51·5 ± 4·3 for the mature, hydrated and germinated pollen, respectively. On the other hand, the average AGP (μg)/protein (μg) ratios were 0·2 ± 0·01, 0·4 ± 0·05 and 0·3 ± 0·02 for the mature, hydrated and germinated pollen, respectively. Detection of galactans and arabinans was carried out using LM5 and LM6 mAbs, respectively. The LM5 mAb labelled up to seven different molecules containing galactan epitopes with molecular weights ranging from 58 to 92 kDa (Fig. 1A). Mature and hydrated pollen grains contained relatively low levels of the LM5 epitopes, but the pool significantly increased during pollen germination and pollen tube growth (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, the LM6 mAb recognized only a single band corresponding to an l-arabinose-rich pectin of about 253 kDa (Fig. 1C), whose density was initially low but increased gradually during pollen hydration and exhibited a maximum in the germinated pollen (Fig. 1D). Profiles of HGs with a low and a high degree of methyl-esterification were examined using JIM5 and JIM7 mAbs, respectively. Low methyl-esterified HGs were detected on blots around 264 kDa using JIM5 mAb (Fig. 1E). The JIM5 epitope was almost undetectable at pollen maturity and after pollen hydration, but then significantly increased during pollen culture (Fig. 1F). The JIM7 mAb bound to a 290 kDa pectin band with a high degree of methyl-esterification (Fig. 1G). JIM7 labelling progressively increased during hydration and further pollen tube growth (Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1.

Pectin profiling in mature, hydrated and germinated olive pollen. (A) Immunoblot detection of galactans with LM5 mAb. (B) Densitometric analysis of the bands that are recognized by LM5 mAb (indicated by bracket in A). Densitometry data are plotted referred to either the total protein or carbohydrate contents (as indicated in key) loaded on the gels. (C) Immunoblot detection of arabinans with LM6 mAb. (D) Densitometric analysis of the 253 kDa pectin from (C) (arrow) as above. (E) Immunoblot detection of low methyl-esterified pectins with JIM5 mAb. (F) Densitometric analysis of the 264 kDa pectin from (E) (arrow) as above. (G) Immunoblot analysis of esterified pectins with JIM7 mAb. (H) Densitometric analysis of 290 kDa pectin from (G) (arrow) as above. Protein molecular markers (kDa) are displayed on the left. MP, mature pollen; HP, hydrated pollen; 3 h, pollen germinated for 3 h.

Immunolocalization of pectins in hydrated and germinating olive pollen

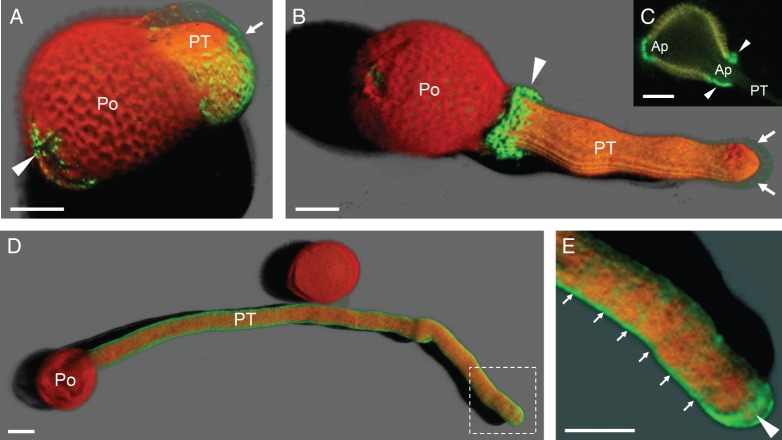

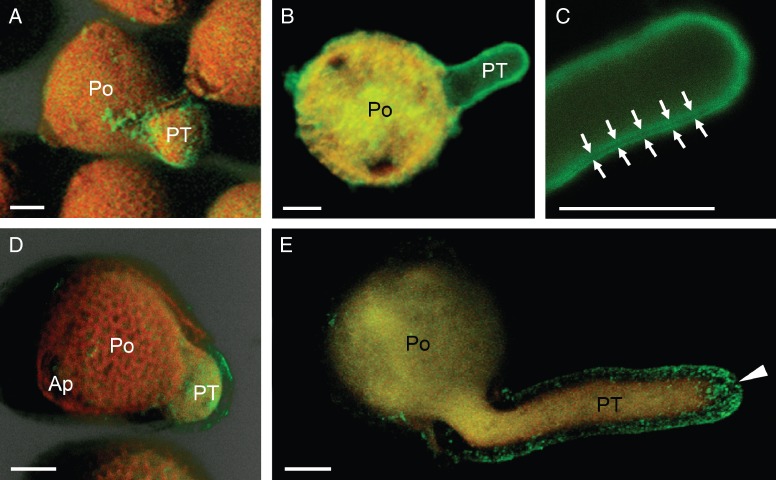

Immunolocalization of pectins was first performed at the confocal microscope. By the use of LM5 mAb, galactans were specifically localized in all the three apertures of mature pollen grains (Fig. 2A). However, the fluorescent labelling was more intense in the apertural region through which the pollen tube protruded (Fig. 2A, B). The intense labelling may correspond to the apertural intine remains (Fig. 2C). In the germinating pollen, these pectins formed a ring of green fluorescence as a collar around the germinative aperture (Fig. 2B). The cell wall of the pollen tube shank showed a weak level of fluorescence, while it was more intense at the pollen tube apex. Labelling with LM6 mAb allowed us to study the spatial distribution of arabinans. The cell wall was specifically labelled along the entire pollen tube, particularly at the tip (Fig. 2D, E). Label intensity showed regular ring-shaped fluctuations in pectin deposition along the longitudinal axis of the pollen tube (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Confocal microscopy imaging of pectins with neutral side chains in olive pollen during in vitro germination. (A–C) Localization of pectins containing [(1 → 4)-β-d-galactose]4 motifs with LM5 mAb. (A) 3-D reconstruction of pollen at the onset of germination. Green fluorescent labelling was observed at the pollen apertures (arrowhead) and the cell wall of the emerging pollen tube (arrow). (B) 3-D reconstruction of pollen germinated for 3 h. Pectins formed a ring-shaped structure as a collar around the germinative aperture (arrowhead). A weak green labelling was also noticeable in the cell wall at the pollen tube apex (arrows). (C) Optical section of pollen germinated for 3 h. The remains of the apertural intine were labelled (arrowheads). The pollen tube cytoplasm was also labelled. (D, E) Localization of pectins containing [(1 → 5)-α-l-arabinose]5 motifs with LM6 mAb. (D) 3-D reconstruction of pollen germinated for 3 h. LM6 labelling was distributed along the cell wall of the pollen tube. (E) Magnification of dashed area from Fig. 1D. Several ring-shaped deposits were visible at the sub-apical zone (arrows). Green labelling was more intense at the pollen tube tip (arrowhead). Ap, aperture; Po, pollen grain; PT, pollen tube. Scale bars = 10 µm.

Homogalacturonans with a low and a high degree of methyl-esterification were immunolocalized with JIM5 and JIM7 mAbs, respectively. Low methyl-esterified HGs were labelled in the three apertures (Fig. 3A). In germinated pollen tubes, an intense labelling was homogenously distributed along the surface of the cell wall of the pollen tube (Fig. 3B–D). At very early stages of germination, JIM7 labelling was specifically localized in the emerging pollen tube tip (Fig. 3E). After several hours of culture, label intensity was higher at the apex (Fig. 3F), but a less intense fluorescent signal was also visible as spots that were irregularly distributed along the pollen tube wall.

Fig. 3.

Confocal microscopy imaging of pectins with a low and high degree of methyl-esterification in the olive pollen during in vitro germination. (A–C) Localization of pectins with a low degree of methyl-esterification using JIM5 mAb. (A) Optical section of hydrated pollen. JIM5 green labelling was mainly located in the apertures (arrowheads). (B) Optical section of a pollen grain germinated for 1 h. Green fluorescence was mainly located along the pollen tube wall. (C) 3-D reconstruction of pollen germinated for 3 h. JIM5 epitopes were homogenously distributed along the pollen tube wall. (D–F) Localization of highly methyl-esterified pectins with JIM7 mAb. (D) Z-stack projection of hydrated pollen. JIM7 green labelling was restricted to the cell wall at the pollen tube tip (arrowhead). (E, F) Z-stack projections of pollen germinated for 1 (E) and 3 h (F). Green fluorescent labelling was very intense at the pollen tube tip (arrowheads). Ap, aperture; Po, pollen grain; PT, pollen tube. Scale bars = 10 µm.

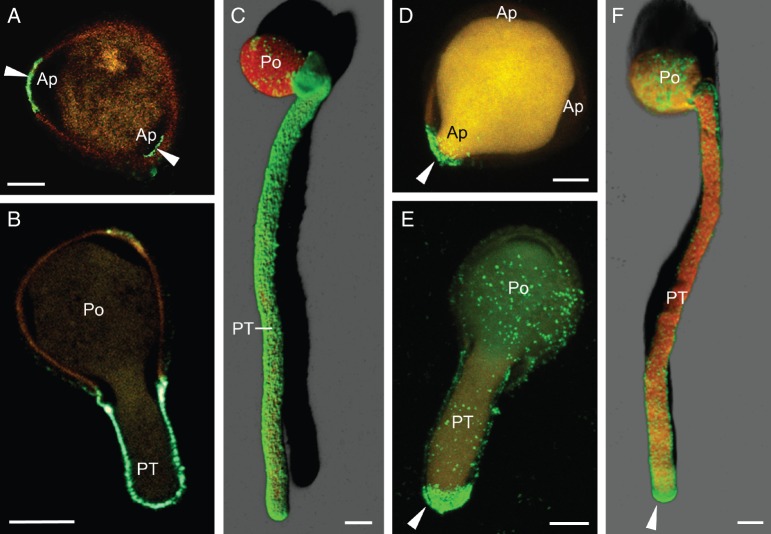

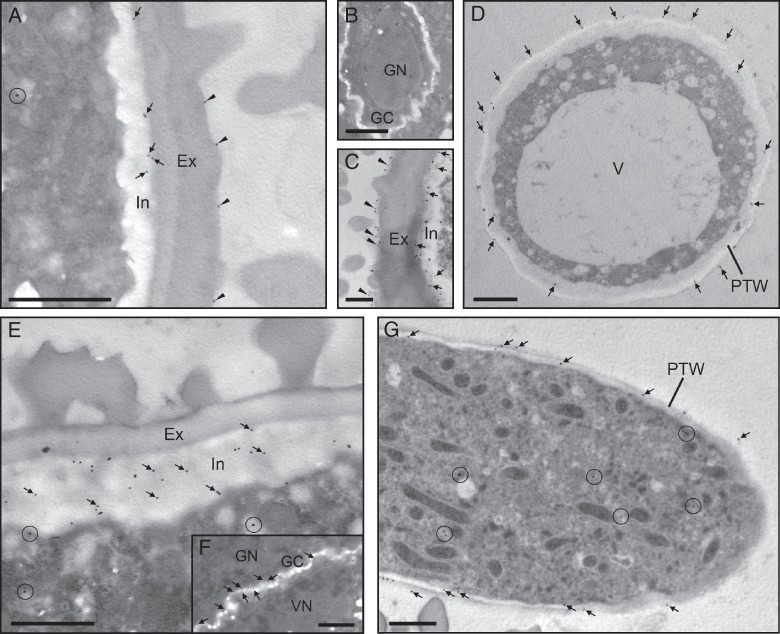

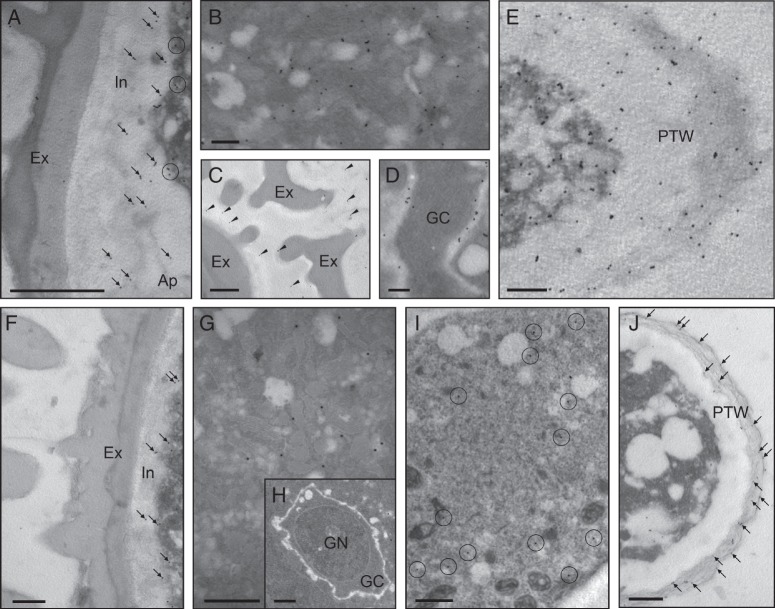

The ultrastructural localization of pectins at the transmission electron microscope confirmed the results obtained by using immunofluorescence techniques and revealed some new data about their cellular distribution. Immunogold labelling of [(1 → 4)-β-d-galactose]4 epitopes was detected in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell, mainly associated with small vesicles, and the intine (Fig. 4A). The generative cell did not show any LM5 labelling (Fig. 4B). The exine and the material adhered to its surface also showed some epitopes (Fig. 4C). In the germinative aperture, gold labelling was very intense and restricted to the outer layer containing a dense fibrillar material (Fig. 4D). In the cell wall of the pollen tube, LM5 labelling was mostly found in the outer layer (Fig. 4E). LM6 epitopes were found in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell, mainly associated with small vesicles, but the pollen cell wall was devoid of labelling (Fig. 4F). Arabinans were also present in the wall of the generative cell, in the vicinity of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4G). In the pollen tube, LM6 labelling was mainly found in the outer layer of the cell wall (Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4.

Ultrastructural immunolocalization of neutral pectins in the olive pollen during in vitro germination. (A–E) Localization of galactans with LM5 mAb. (A) Transverse section of hydrated pollen. Labelling with gold was mainly associated with vesicles scattered in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell (circles), and the intine (arrows). (B) The generative cell did not show any gold particles. (C) The exine (arrows) and the material that coated its surface (arrowheads) also showed some LM5 epitopes. (D) Transverse section of pollen germinated for 1 h. A strong gold labelling was observed in the fibrillar material (arrows). (E) Tangential section of a pollen tube (germinated for 3 h). Galactans localized in the outer layer of the pollen tube wall. (F–H) Localization of neutral pectins with LM6 mAb. (F) Transverse section of mature pollen. LM6 epitopes were found in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell (circles). (G) Arabinans were also present in the cell wall of the generative cell (arrowheads). (H) Longitudinal section of a pollen tube (3 h of germination). Gold labelling was mainly found in the outer layer of the pollen tube wall. Ap, aperture; Ex, exine; GC, generative cytoplasm; GN, generative nucleus; In, intine; PTW, pollen tube wall; VN, vegetative nucleus. Scale bars = 1 µm.

In the mature pollen grain, pectins with a low degree of methyl-esterification were scarcely detected in the intine close to the exine, and also coating the exine surface (Fig. 5A). The generative cell did not show any labelling (Fig. 5B). After germination, the intine and the outer surface of the exine appeared intensively decorated with gold particles (Fig. 5C). In the pollen tube, the epitope was mainly present in the outer layer of the cell wall (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, highly methyl-esterifed HG epitopes were localized inside of small vesicles scattered in the cytoplasm of vegetative cells, as well as in the intine of mature pollen (Fig. 5E). The wall of the generative cell was also labelled with gold particles, which localized in the vicinity of the plasma membrane (Fig. 5F). In the pollen tube shank, JIM7 labelling was scarce (Fig. 5G). Negative controls did not show any significant labelling (Supplementary Data Fig. S1).

Fig. 5.

Ultrastructural immunolocalization of pectins with a low and high degree of methyl-esterification in the olive pollen during in vitro germination. (A–D) Immunolocalization of pectins with a low degree of methyl-esterification with JIM5 mAb. (A) Transverse section of mature pollen. Gold labelling was scarce and localized in the cytoplasm (circle), the intine (arrows) and on the exine surface (arrowheads). (B) The generative cell did not show any JIM5 epitope. (C) Transverse section of germinated (3 h) pollen. Numerous gold particles decorated the intine (arrows) and the material that coated the exine (arrowheads). (D) Transverse section of a pollen tube (3 h of germination). JIM5 epitopes were present in the outer pectin layer of the wall (arrows). (E–G) Immunolocalization of highly methyl-esterified pectins with JIM7 mAb. (E) Transverse section of hydrated pollen. Gold labelling was located in the cytoplasm (circles) and the intine (arrows). (F) The generative cell wall was also labelled (arrows). (G) Tangential section of a pollen tube (3 h of germination). JIM7 epitopes were observed in the cytoplasm (circles) and the outer layer of the pollen tube wall (arrows). Ex, exine; GC, generative cytoplasm; GN, generative nucleus; In, intine; PTW, pollen tube wall; VN, vegetative nucleus; V, vacuole. Scale bars = 1 µm.

AGP profiling in the olive pollen during germination

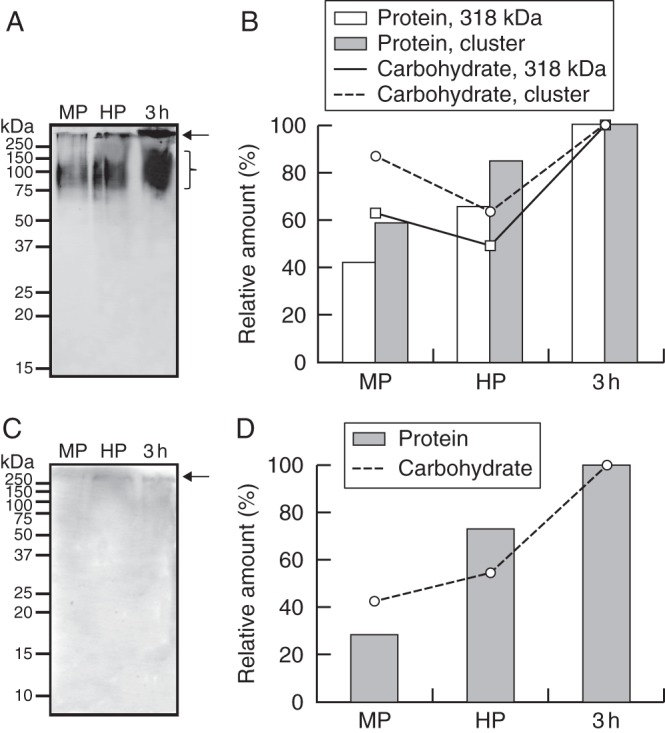

AGP levels were analysed during pollen hydration and pollen tube growth using JIM13 and JIM14 mAbs. JIM13 recognized a 318 kDa AGP band and a second cluster of AGPs with molecular weights ranging from 90 to 120 kDa (Fig. 6A). In both cases, levels progressively increased during hydration and further germination steps (Fig. 6B). The JIM14 antibody was able to bind to a unique AGP band of about 270 kDa (Fig. 6C). Similarly, its amount progressively increased after hydration (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

AGP profiling in mature, hydrated and germinated olive pollen. (A) Western blot detection of AGPs with JIM13 mAb. (B) Densitometric analysis of the 318 kDa AGP (arrow) and the AGP cluster (bracket) from Fig. 1A. Densitometry data of the 318 kDa band and the AGP cluster are plotted referred to either the total protein (white and light grey bars, respectively) or AGP (solid line with white squares, and dashed line with grey circles, respectively) contents loaded on the gels. (C) Western blot detection of JIM14 epitopes. (D) Densitometric analysis of the 269 kDa AGP from Fig. 1C. Densitometry data are plotted referred to either the total protein (dark grey bars) or AGP (dotted line with black triangles) contents loaded on the gels. Molecular markers (kDa) are displayed on the left. MP, mature pollen; HP, hydrated pollen; 3h, pollen germinated for 3 h.

Immunolocalization of AGPs in hydrated and germinated olive pollen

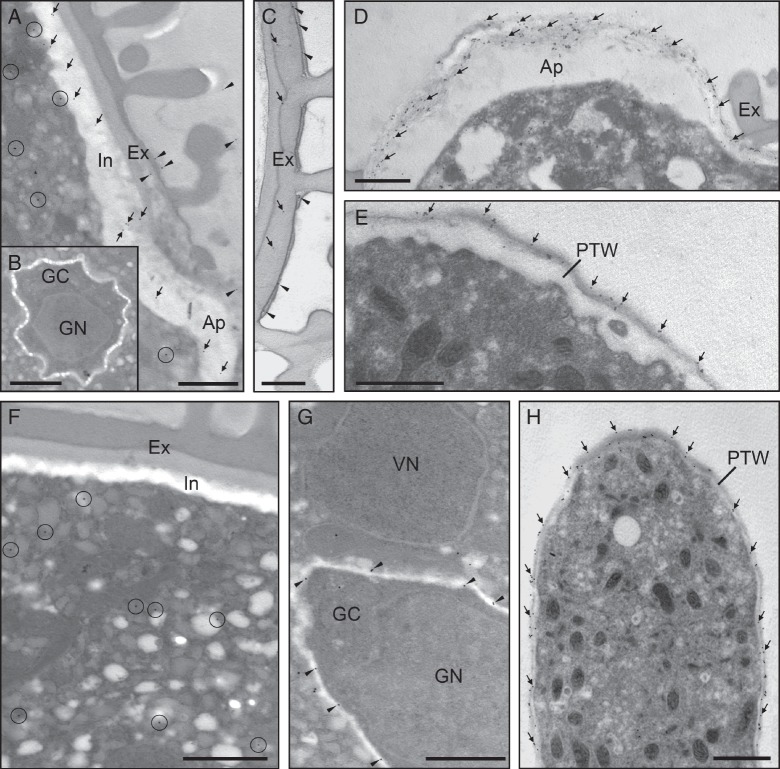

At the very early steps of pollen germination, the immunofluorescent labelling of JIM13 epitopes was localized around the germinative aperture, as well as in the cell wall of the emerging pollen tube (Fig. 7A). The antibody also produced patches of fluorescence on the surface of the sculptured exine wall. Later, JIM13 labelling was localized on the cell wall along the pollen tube (Fig. 7B). In some optical sections, two labelled layers could be clearly distinguished in the cell wall (Fig. 7C). The JIM14 mAb produced a weak labelling on the cell wall of the pollen tube shank (Fig. 7D, E). The fluorescent labelling was more intense in both the apex and the sub-apical region of the pollen tube (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Confocal microscopy imaging of AGPs in the olive pollen during in vitro germination. (A–C) Localization of AGPs with JIM13 mAb. (A) 3-D reconstruction of a hydrated pollen grain and its emerging pollen tube. JIM13 green labelling was localized in the emerging pollen tube wall and on the pollen grain surface. (B) Z-stack projection of germinated (1 h) pollen. The green fluorescent labelling was located along the pollen tube wall and on the surface of the pollen. (C) At higher magnification, a double layer of JIM13 green labelling was clearly distinguishable in the pollen tube wall (arrows). (D, E) Localization of JIM14 epitopes. (D) 3-D reconstruction of germinated pollen. Green labelling was mainly located in the cell wall at the pollen tube tip. (E) Z-stack projection of germinated pollen after 1 h of culture. JIM14 epitopes were located along the pollen tube wall and accumulated at the apex (arrowhead). Po, pollen grain; PT, pollen tube. Scale bars = 10 µm.

At the ultrastructural level, JIM13 labelling was located in the intine, particularly at the apertural region (Fig. 8A), and the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell, mainly associated with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) cisternae (Fig. 8B). The pollen coat material that fills the exine cavities was also decorated with JIM13 epitopes (Fig. 8C). The wall of the generative cell also showed a significant labelling in the vicinity of the plasma membrane (Fig. 8D). In the pollen tube, gold particles were located in the cytoplasm, mainly associated with small vesicles, and across the wall (Fig. 8E). JIM13 labelling was also present extracellularly, in the vicinity of the cell wall, suggesting that this AGP is secreted to the extracellular space (Fig. 8E). The ultrastructural localization of JIM14 epitopes was carried out using JIM14 mAb. This epitope localized in the intine, close to the plasma membrane (Fig. 8F), and in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell (Fig. 8G). The exine and the generative cell wall did not show any labelling (Fig. 8G, H). In the pollen tube, gold particles were mostly localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8I) and the outer layer of the cell wall (Fig. 8J).

Fig. 8.

Ultrastructural immunolocalization of AGPs in the olive pollen during in vitro germination. (A–E) Immunolocalization of JIM13 epitopes. (A, B) Transverse sections of mature pollen. Gold particles were observed in the intine (A, circles), particularly at the apertural regions (A, arrows). Gold particles also co-localized with vesicles scattered in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell (B). (C, D) The material that filled the exine cavities (C, arrowheads) and the generative cell wall (D) also showed a significant labelling. (E) Tangential section of a pollen tube germinated for 3 h. An intense gold labelling was found in the pollen tube cytoplasm and cell wall. (F–J) Immunolocalization of JIM14 epitopes. (F–H) Transverse sections of hydrated pollen. Gold particles were secreted to the intine (F, arrows) and also located associated with cytoplasmic vesicles (G), whereas the generative cell did not show any labelling (H). (I) Tangential section of a pollen tube germinated for 3 h. JIM14 epitopes were located in the pollen tube cytoplasm (circles). (J) Transverse section of a pollen tube as above. Gold particles were also observed in the outer layer of the pollen tube wall (arrows). Ex, exine; GC, generative cell; GN, generative nucleus; In, intine; PTW, pollen tube wall. Scale bars = 0·5 µm.

DISCUSSION

The spatial pattern of both esterified and unesterified pectin deposition in the olive pollen tube wall was similar to that previously described in other species (Li et al., 1994; Jauh and Lord, 1996; Dardelle et al., 2010). The low content of JIM5 and JIM7 epitopes in the mature pollen grain contrasted with the high levels detected after germination. This fact suggests that HG synthesis, secretion and de-esterification are processes temporally connected to pollen tube elongation. Highly methyl-esterified pectins were mainly localized inside vesicles at the pollen tube tip, as previously reported in other species (Li et al., 1994; Jauh and Lord, 1996). Unesterified pectins were located in large amounts in the cell wall along the pollen tube shank. It was previously suggested that unesterified pectins might reinforce pollen tubes for passing through the stylar transmitting tissue (Li et al., 1994). A lipid transfer protein (LTP), called SCA (stigma/stylar cysteine-rich adhesion), mediates the interaction between the pectic matrices of the pollen tubes and the stylar transmitting tract epidermal cells in lily (Mollet et al., 2000; Park et al., 2000). The lily stylar pectin involved in adhesion contains ‘smooth regions’ of low-esterified HG and regions of RG-I substituted with arabinan or galactan (Mollet et al., 2000). Interestingly, low esterified pectins are also abundant during pollination in the cell wall of the olive stylar transmitting cells (Suárez et al., 2013). Consequently, a role for unesterified HG in pollen tube–style cell adhesion is also possible in this species.

While HGs in the pollen tube have been widely studied, there is much less information about the composition and distribution of RG-I. According to our data, the olive pollen grain synthesizes branched RG-I with either (1 → 5)-α-l-arabinans or (1 → 4)-β-d-galactans. The content of both epitopes notably increased after germination, suggesting that these pectins are newly synthesized during pollen tube growth. However, their quantitative levels and localization patterns clearly differed during this process. Thus, only galactans were found in the pollen wall, being massively deposited at the apertural site through which the pollen tube emerged. Three-dimensional image reconstruction showed that these epitopes specifically formed a ring-like structure around the germinative aperture. The appearance of (1 → 4)-β-d-galactans in developing pea cotyledons correlated with an increase in firmness (McCartney and Knox, 2000). Therefore, we can hypothesize that this galactan collar-like structure might reinforce the joint of the pollen tube with the pollen grain, contributing to its mechanical stability against tension stress. Moreover, the presence of LM5 epitopes in the exine is in good agreement with the early deposition of (1 → 4)-β-d-galactans in the newly formed primexine and exine reported in Beta vulgaris developing microspores (Majewska-Sawka and Rodríguez-García, 2006). Low although detectable amounts of LM5 epitopes were also synthesized and secreted via the ER–Golgi into the cell wall at the olive pollen tube tip. Similarly, 4-linked galactosyl residues accounted for only 1·5 % of the monosaccharide composition of the Arabidopsis thaliana pollen tube wall (Dardelle et al., 2010). Here, these compounds might increase the firmness of the cell wall, protecting the tip from mechanical damage.

The olive pollen tube wall was particularly rich in arabinans. Likewise, Nicotiana alata and A. thaliana pollen tube walls also showed high levels of 5-linked arabinosyl residues (Rae et al., 1985; Dardelle et al., 2010). The pollen grain wall did not contain arabinans, which are also absent during the sugar beet and the English ryegrass pollen wall ontogeny (Majewska-Sawka and Rodríguez-García, 2006; Wiśniewska and Majewska-Sawka, 2006). In contrast, arabinans are abundant in the intine layer of the early-divergent Angiosperm Trithuria submersa (Costa et al., 2013), suggesting that LM6 epitope distribution in pollen grains may be species dependent. Arabinans are also present in high amounts in the cell wall of active proliferating tissues such as root meristems (Willats et al., 1999) or callus (Kikuchi et al., 1995; Majewska-Sawka and Münster, 2003). It was suggested that RG-I with arabinan side chains may prevent HG polymers from forming tight associations in order to maintain certain wall plasticity (Jones et al., 2003). This property seems to be essential in the case of fast growing cells, such as pollen tubes or root cells. Arabinan epitopes formed ring-shaped deposits near the olive pollen tube tip, although the biological significance of this is unclear. These periodic rings are also visible in tobacco pollen tubes with the anti-AGP MAC207 and JIM8 antibodies (Li et al., 1992). In certain cases, LM6 mAb recognizes 1,5-linked arabinosyl residues in AGPs (Willats et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2005). Thus, it is possible that the LM6 epitope may be present in some AGPs, such as those occurring in these periodic rings. Interestingly, loss in cell adhesion in non-organogenic calli and fruits is often associated with low content, low branching or misplaced arabinan in cell walls (Iwai et al., 2001; Orfila et al., 2001; Leboeuf et al., 2004; Peña and Carpita, 2004). The content of arabinans also increases in the olive stylar transmitting tissue cell walls during the passage of pollen tubes (Suárez et al., 2013), supporting the idea that arabinans might be involved in adhesion phenomena.

Two classes of AGPs were detected in the olive pollen grain and pollen tube, being synthesized de novo and secreted during pollen germination. JIM13 antibody bound to several bands >90 kDa in western blot experiments in all the developmental stages studied. Similar results were reported in Lilium longiflorum germinated pollen (Jauh and Lord, 1996). There are several reports on JIM13 immunolocalization in pollen grains and pollen tubes, but the information is incomplete in most cases (Nguema-Ona et al., 2012). In the olive pollen, JIM13 epitopes were located in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell and the generative cell wall, as previously described in tobacco and kiwi (Qin et al., 2007; Speranza et al., 2009). The function of AGPs that localize on the surface of the generative and sperm cells is not clear. Interestingly, unfertilized tobacco egg cells contain high amounts of JIM13 epitopes, but levels rapidly decrease after fertilization (Qin and Zhao, 2006). These data suggest that these molecules may be involved in the recognition and fusion of egg and sperm cells. The intine layer was also labelled, as reported in A. thaliana (Lennon and Lord, 2000), tobacco (Qin et al., 2007), several Gymnosperms (Mogami et al., 1999; Yatomi et al., 2002) and the early-divergent Angiosperm T. submersa (Costa et al., 2013). In addition, JIM13 labelling was also found in the pollen coat material that filled the exine cavities. These extracellular JIM13 epitopes might have a sporophytic origin. Indeed, the anther tapetum synthesizes and secretes JIM13 epitopes in A. thaliana (Coimbra et al., 2007). However, this possibility needs to be experimentally validated. In the pollen tube, up to three different spatial patterns of JIM13 labelling have been described to date: pollen tube tip wall labelling as in lily (Jauh and Lord, 1996; Mollet et al., 2002), whole pollen tube wall labelling as in tobacco (Qin et al., 2007) and no labelling as in A. thaliana (Pereira et al., 2006). The labelling found in the olive was similar to that described in tobacco. These divergences might be due to differences in (1) the taxonomic position of the species studied; (2) the organization of the epitopes in the structure of AGPs; and/or (3) the accessibility of the epitopes in the pollen tube wall. Treatments with the Yariv reagent caused pollen tube growth to cease due to abnormal callose deposition (Jauh and Lord, 1996; Quin et al., 2007). When the Yariv reagent was removed from the germination medium, a new pollen tube emerged behind the arrested tip. Interestingly, the JIM13 antibody labels the site of emergence and the tip of regenerated new pollen tubes (Mollet et al., 2002). Hence, these data suggest that these AGPs may be important in the deposition of new cell wall precursors during pollen tube growth. AGPs are also candidate molecules for adhesion phenomena in pollination. Thus, the presence of JIM13 epitopes in the cell wall of the olive stylar transmitting cells (Suárez et al., 2013) and on the pollen tube wall surface (this study) supports this idea.

In contrast, the AGP epitope that is recognized by the JIM14 antibody is still unknown (Yates et al., 1996). In the olive pollen grain, JIM14 labelling was found in the cytoplasm of the vegetative cell, and the intine layer of the cell wall. In the pollen tube, the cytoplasm and the outer layer of the pollen tube wall were labelled, as previously described in kiwifruit pollen (Speranza et al., 2009). Recently, it has been proposed that AGPs secreted to the apex might act as co-receptors and function in signalling processes related to pollen tube guidance (Boisson-Dernier et al., 2011; Zang et al., 2011). JIM14 labelling was very intense in the olive pollen tube apex, thus supporting this idea.

To conclude, we have provided data that complete and add new information to the map of pectins and AGPs in the pollen tube cell wall. Our data showed that new synthesis and secretion of pectins and AGPs takes place in the pollen during its germination, this process being developmentally regulated. We suggest that galactans might provide mechanical stability to the pollen tube, reinforcing those regions that are particularly sensitive to tension stress and mechanical damage. On the other hand, arabinans and AGPs might be important in recognition and adhesion phenomena of the pollen tube and the stylar transmitting cells, as well as the egg and sperm cells.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms C. Martínez-Sierra for her expert technical assistance. This work was supported by the Junta de Andalucía (ERDF-co-financed project P06-AGR-01791) and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN) (ERDF-co-financed project AGL2008-00517). C.S. thanks the MICINN for providing FPI grant funding.

LITERATURE CITED

- Boisson-Dernier A, Kessler SA, Grossniklaus U. The walls have ears: the role of plant CrRLK1Ls in sensing and transducing extracelular signals. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2011;62:1581–1591. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, Cheung A, Hepler PK. Pectin methylesterase, a regulator of pollen tube growth. Plant Physiology. 2005;138:1334–1346. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.059865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. The Plant Journal. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-Q, Ye D. Roles of pectin methylesterases in pollen-tube growth. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2007;49:94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra S, Almeida J, Junqueira V, Costa M, Pereira LG. Arabinogalactan proteins as molecular markers in Arabidopsis thaliana sexual reproduction. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:4027–4035. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Pereira AM, Rudall PJ, Coimbra S. Immunolocalization of arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) in reproductive structures of an early-divergent Angiosperm, Trithuria (Hydatellaceae) Annals of Botany. 2013;111:183–190. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardelle F, Lehner A, Ramdani Y, et al. Biochemical and immunocytological characterizations of Arabidopsis pollen tube cell wall. Plant Physiology. 2010;153:1563–1576. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical Chemistry. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- Geitmann A, Steer M. The architecture and properties of the pollen tube cell wall. In: Malhó R, editor. The pollen tube. A cellular and molecular perspective. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Vidali L, Cheung AY. Polarized cell growth in higher plants. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2001;17:159–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J. Pollen germination and pollen tube growth. International Review of Cytology. 1987;107:1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Iwai H, Ishii T, Satoh S. Absence of arabinan in the side chains of the pectic polysaccharides strongly associated with cell walls of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia non-organogenic callus with loosely attached constituent cells. Planta. 2001;213:907–915. doi: 10.1007/s004250100559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MC. Structure and properties of pectin gels in plant cell walls. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1984;7:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jauh GY, Lord EM. Localization of pectins and arabinogalactan protein in lily (Lilium longiflorum L.) pollen tube and style, and their possible roles in pollination. Planta. 1996;199:251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Lord EM. Extracellular guidance cues and intracellular signalling pathways that direct pollen tube growth. In: Malhó R, editor. The pollen tube. A cellular and molecular perspective. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Seymour GB, Knox JP. Localization of pectic galactan in tomato cell walls using a monoclonal antibody specific to (1→4)-β-d-galactan. Plant Physiology. 1997;113:1405–1412. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.4.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Milne JL, Ashford D, McQueen-Mason SJ. Cell wall arabinan is essential for guard cell function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2003;100:11783–11788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832434100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi A, Satoh S, Nakamura N, Fujii T. Differences in pectic polysaccharides between carrot embryogenic and non-embryogenic calli. Plant Cell Reports. 1995;14:279–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00232028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboeuf E, Thoiron S, Lahaye M. Physico-chemical characteristics of cell walls from Arabidopsis thaliana microcalli showing different adhesion strengths. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55:2087–2097. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJD, Sakata Y, Mau S-L, et al. Arabinogalactan-proteins are required for apical cell extension in the moss Physcomitrella patens. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:3051–3065. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon KA, Lord EM. In vivo pollen tube cell of Arabidopsis thaliana. I. Tube cell cytoplasm and wall. Protoplasma. 2000;214:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Bruun L, Pierson ES, Cresti M. Periodic deposition of arabinogalactan epitopes in the cell wall of pollen tubes of Nicotiana tabacum L. Planta. 1992;188:532–538. doi: 10.1007/BF00197045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Chen F, Linskens H, Cresti M. Distribution of unesterified and esterified pectins in cell walls of pollen tubes of flowering plants. Sexual Plant Reproduction. 1994;7:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Mareck A, Faleri C, Moscatelli A, Liu Q, Cresti M. Detection and localization of pectin methylesterase isoforms in pollen tubes of Nicotiana tabacum L. Planta. 2002;214:734–740. doi: 10.1007/s004250100664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada JM, Herrero M. Arabinogalactan-protein secretion is associated with the acquisition of stigmatic receptivity in the apple flower. Annals of Botany. 2012;110:573–584. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Chen M, Showalter AM. Developmental expression and perturbation of arabinogalactan-proteins during seed germination and seedling growth in tomato. Physiologia Plantarum. 2001;112:442–450. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2001.1120319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska-Sawka A, Münster A. Cell wall antigens in mesophyll cells and mesophyll-derived protoplasts of sugar beet: possible implication in protoplast recalcitrance? Plant Cell Reports. 2003;21:946–954. doi: 10.1007/s00299-003-0612-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska-Sawka A, Rodríguez-García MI. Immunodetection of pectin and arabinogalactan protein epitopes during pollen exine formation of Beta vulgaris L. Protoplasma. 2006;228:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00709-006-0160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney L, Knox JP. Regulation of pectic polysaccharide domains in relation to cell development and cell properties in the pea testa. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:707–713. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.369.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogami N, Nakamura S, Nakamura N. Immunolocalization of the cell wall components in Pinus densiflora pollen. Protoplasma. 1999;206:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mollet JC, Park SY, Nothnagel EA, Lord EM. A lily stylar pectin is necessary for pollen tube adhesion to an in vitro stylar matrix. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:1737–1750. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollet JC, Kim S, Jauh GY, Lord EM. Arabinogalactan proteins, pollen tube growth, and the reversible effects of Yariv phenylglycoside. Protoplasma. 2002;219:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s007090200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen D. Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2008;11:266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguema-Ona E, Coimbra S, Vicré-Gibouin M, Mollet JC, Driouich A. Arabinogalactan proteins in root and pollen-tube cells: distribution and functional aspects. Annals of Botany. 2012;110:383–404. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothnagel E. Proteoglycans and related components in plant cells. International Review of Cytology. 1997;174:195–191. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfila C, Seymour GB, Willats WG, et al. Altered middle lamella homogalacturonan and disrupted deposition of (1→5)-α-l-arabinan in the pericarp of Cnr, a ripening mutant of tomato. Plant Physiology. 2001;126:210–221. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Jauh GY, Mollet JC, et al. A lipid transfer-like protein is necessary for lily pollen tube adhesion to an in vitro stylar matrix. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:151–163. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña MJ, Carpita NC. Loss of highly branched arabinans and debranching of rhamnogalacturonan I accompany loss of firm texture and cell separation during prolonged storage of apple. Plant Physiology. 2004;135:1305–1313. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.043679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell RI, Janniche L, Kjellbom P, Scofield GN, Peart JM, Roberts K. Developmental regulation of a plasma membrane arabinogalactan protein epitope in oilseed rape flowers. The Plant Cell. 1991;3:1317–1326. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.12.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira LG, Coimbra S, Oliveira H, Monteiro L, Sottomayor M. Expression of arabinogalactan protein genes in pollen tubes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2006;223:374–380. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Zhao J. Localization of arabinogalactan proteins in egg cells, zygotes, and two-celled proembryos and effects of beta-d-glucosyl Yariv reagent on egg cell fertilization and zygote division in Nicotiana tabacum. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:2061–2074. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Chen D, Zhao J. Localization of arabinogalactan proteins in anther, pollen, and pollen tube of Nicotiana tabacum L. Protoplasma. 2007;231:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00709-007-0245-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae AL, Harris PJ, Bacic A, Clarke AE. Composition of the cell walls of Nicotiana alata Link et Otto pollen tubes. Planta. 1985;166:128–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00397395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlüpmann H, Bacic A, Read SM. Uridine diphosphate glucose metabolism and callose synthesis in cultured pollen tubes of Nicotiana alata Link et Otto. Plant Physiology. 1994;105:659–670. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter AM. Arabinogalactan proteins: structure, expression and function. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2001;58:1399–1417. doi: 10.1007/PL00000784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speranza A, Taddei AR, Gambellini G, Ovidi E, Scoccianti V. The cell wall of kiwifruit pollen tubes is a target for chromium toxicity: alterations to morphology, callose pattern and arabinogalactan protein distribution. Plant Biology. 2009;11:179–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez S, Zienkiewicz A, Castro AJ, Zienkiewicz K, Majewska-Sawka A, Rodríguez-García MI. Cellular localization and levels of pectins and arabinogalactan proteins in olive (Olea europaea L.) pistil tissues during development: implications for pollen–pistil interaction. Planta. 2013;237:305–319. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1774-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats WGT, Limberg G, Buchholt HC, et al. Analysis of pectic epitopes recognised by hybridoma and phage display monoclonal antibodies using defined oligosaccharides, polysaccharides, and enzymatic degradation. Carbohydrate Research. 2000;327:309–320. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats WGT, Marcus SE, Knox JP. Generation of a monoclonal antibody specific to (1→5)-α-l-arabinan. Carbohydrate Research. 1998;308:149–152. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(98)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats WGT, Steele-King CG, Marcus SE, Knox JP. Side chains of pectic polysaccharides are regulated in relation to cell proliferation and cell differentiation. The Plant Journal. 1999;20:619–628. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewska E, Majewska-Sawka A. Cell wall polysaccharides in differentiating anthers and pistils of Lolium perenne. Protoplasma. 2006;228:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00709-006-0175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates EA, Valdor J-F, Haslam SM, et al. Characterization of carbohydrate structural features recognized by anti arabinogalactan-protein monoclonal antibodies. Glycobiology. 1996;6:131–139. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatomi R, Nakamura S, Nakamura N. Immunochemical and cytochemical detection of wall components of germinated pollen of Gymnosperms. Grana. 2002;41:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zang Y, Yang J, Showalter A. AtAGP18, a lysine-rich arabinogalactan protein in Arabidopsis thaliana, functions in plant growth and development as a putative co-receptor for signal transduction. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 2011;6:855–857. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.6.15204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.