Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Peginterferon and ribavirin treatment is less effective for hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infections in African Americans (AA) compared with Caucasian Americans (CA). Host genetic variability near the interleukin-28B (IL28B) gene locus is partly responsible. We investigated the relationship between ribavirin drug exposure and week 24 and 72 (sustained virologic response, SVR) responses (undetected serum HCV RNA) in 71 AA and 74 CA with HCV genotype 1 who received >90 % of the prescribed peginterferon and weight-based ribavirin (1,000 or 1,200 mg per day) from week 1 to 24.

METHODS

Ribavirin plasma levels were measured at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24; ribavirin area under the concentration vs. time curve (AUC) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule.

RESULTS

Compared with CA, AA had lower week 24 (WK24VR) (57.8 vs. 78.1; P < 0.05) and week 72 (SVR) (36.6 % vs 54.8 %; P < 0.05) response rates. AA also had significantly lower ribavirin exposure (AUC) from week 1 to 12 (P < 0.05). Ribavirin exposures ≥ 4,065 and ≥ 4,480 ng/ml/day in the first week (AUC0–7) were thresholds for WK24VR and SVR in receiver-operating characteristic curve analyses. AA were less likely to have a threshold ribavirin AUC0–7 level than CA (P < 0.05). There were no significant racial differences in WK24VR (AA: 77 vs. CA: 84 %) and SVR (AA: 52 vs. CA: 60 %) rates in patients who met the ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds. Ribavirin AUC0–7 predicted WK24VR and SVR independently of IL28B single-nucleotide polymorphism rs12979860 genotype. Yet, achieving threshold AUC0–7 levels increased response rates primarily in AA with the less favorable non-C/C genotypes.

CONCLUSIONS

Standard weight-based dosing leads to suboptimal ribavirin exposure in AA and contributes to the racial disparity in peginterferon and ribavirin treatment efficacy for HCV genotype 1.

INTRODUCTION

Less than 50 % of patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 experience a sustained virologic response (SVR) following treatment with peginterferon plus ribavirin (1,2). Compared with Caucasian Americans (CA), SVR is significantly lower in African Americans (AA) with HCV genotype 1 infections (19–28 % vs. 52 %) (3,4). However, the racial disparity in response is manifested 1–2 days after treatment initiation as a weaker decline in serum HCV RNA in AA (5,6). A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) near the interleukin-28B (IL28B) gene locus on chromosome 19q13.3 explains up to 50 % of the racial disparity in SVR (7). The basis for residual disparity in peginterferon and ribavirin efficacy has not been fully defined. An HCV NS3 protease inhibitor (boceprevir or telaprevir) combined with peginterferon and ribavirin is now standard therapy for HCV genotype 1 (8,9). Yet, HCV protease inhibitors are also less efficacious in AA (8,9). The exact cause is unclear, but racial differences in responsiveness to peginterferon and ribavirin are thought to have a role.

The likelihood of a SVR following peginterferon and ribavirin treatment is closely related to adherence to both drugs. In a similar way, higher peginterferon and ribavirin blood concentrations have been associated with superior SVR rates (10–16). Peginterferon pharmacokinetics did not differ between AA and CA in the study of viral resistance to antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C (VIRAHEP-C) (11). In the Weight-based Dosing of Peginterferon alfa-2b and Ribavirin study, weight-based ribavirin dosing resulted in similar SVR rates (45, 42, and 47 %) in CA patients weighing 65–78 kg (1,000 mg), 85–105 kg (1,200 mg), and >105–125 kg (1,400 mg), respectively (17). The corresponding SVR rates in AA were 13, 22, and 31 % (P = 0.036), raising the possibility that standard weight-based ribavirin dosing is not optimum for many AA. Regarding ribavirin pharmacokinetics, a recent study reported a lower maximum plasma concentration and a borderline decrease in exposure (area under concentration vs. time curve, AUC) from time 0 to 12 h after the first dose, and trends toward lower maximum plasma concentration and AUC levels after the week-8 dose in AA compared with CA (18). The results were limited by a small sample size, and their clinical relevance was not assessed.

The current study investigated the relationship between ribavirin drug exposure (AUC) from week 1 to 24 and week 24 (WK24VR) and 72 (SVR) responses in AA and CA patients with HCV genotype 1 who were more than 90 % adherent to both peginterferon and ribavirin in the VIRAHEP-C. Also, we defined the significance of ribavirin exposure to treatment outcomes in relation to IL28B gene-related SNP rs12979860 and early HCV RNA kinetics (day 0–28) (6,7).

METHODS

Patients and study design

In the VIRAHEP-C study (4), 401 treatment-naive adults (196 AA and 205 CA) with HCV genotype 1 infections were treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (180 μg per week) and weight-based ribavirin 1,000 mg (< 75 kg) or 1,200 mg (≥ 75 kg) for up to 48 weeks. Patient race was self-reported. Adherence to peginterferon and ribavirin treatment was measured with an electronic Medication Event Management System (MEMS) (Aardex, Zug, Switzerland). On the basis of MEMS, a similar percentage (80–87 %) of AA and CA patients received ≥ 80 % of the maximum peginterferon dose from week 1 to 24 during the VIRAHEP-C (4). In contrast, 76 % of CA and 56 % of AA received ≥ 80 % of the maximum ribavirin dose (4). To avoid the racial difference in ribavirin drug adherence, we conducted a retrospective study in 150 consecutive VIRAHEP-C participants (75 AA and 75 CA) who received at least 95 % of the prescribed ribavirin dose during the first 4 weeks and at least 80 % of the maximum doses of ribavirin and peginterferon during the first 24 weeks. Four AA and two CA patients who received >120 % of the maximum ribavirin dose were excluded. The protocol and consent form were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. All patients provided informed written consent for the clinical trial; 114 of the 144 subjects consented to genetics studies.

Ribavirin plasma concentrations at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 were measured using a modification of Liu’s high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry method (LC-MS/MS) (19,20). Ribavirin and an internal standard (5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine) were extracted with acetonitrile/ethyl acetate. An AQUASIL C18 reverse phase column with an isocratic mobile phase was used to separate ribavirin and the internal standard from the plasma matrix. The detection was accomplished using an API 3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with positive electrospray ionization. Ribavirin (m/z 245–113) and 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine (m/z 242–126) transitions were assessed by multiple reaction monitoring. The assay was validated for ribavirin plasma concentrations of 20–5,000 ng/ml. Cumulative ribavirin exposure (AUC) at intervals from day 0 to weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 were calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule (11).

Virologic end points

WK24VR and SVR (week 72), defined as an undetected serum HCV RNA (< 50 IU/ml; Amplicor assay; Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Alameda, CA) were the primary virologic end points. Serum HCV RNA kinetics from day 0 to 28 were also studied. HCV RNA concentrations were measured on days 0, 1, 2, 7, 14, and 28 using the COBAS Amplicor Hepatitis C Virus Monitor Test, version 2.0 assay (sensitivity 600 IU/ml; Roche Molecular Diagnostics). Early viral kinetics phase 1 was defined as the difference in HCV RNA concentration (log10 IU/ml) from day 0 to 1 and day 0 to 2 (5). Phase 2 was defined as the change in HCV RNA concentrations from day 7 to 28.

IL28B SNP rs12979860 genotyping

Genomic DNA samples (68 AA and 66 CA) were analyzed for SNP rs12979860 at the University of Maryland and Duke University using the TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems) (6,21). Replicate genotyping in 8 % of the samples was >98 % concordant.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using t-tests, analysis of variance tests or nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared with chi-square (χ2) tests. Sixty-four patients per group provided 80 % power to detect a 20 % difference in ribavirin AUC between AA and CA with the 40 % interpatient variability observed. The effect of SNP rs12979860 genotype on virologic response was evaluated under the additive genetic model, with the genotype variable coded as the number of C alleles (6). Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the associations among baseline variables, ribavirin plasma exposure and virologic response. Variables that differed between AA and CA or between WK24 responders (WK24VR) and non-responders (WK24NR) in univariate analysis (P value ≤ 0.25) were retained for selection by the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method (22). Variables with non-zero coefficients were further analyzed in a multivariable logistic regression model. Receiver-operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was used to identify ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds or best cutoff levels to discriminate WK24VR and SVR from nonresponders. LASSO was performed using the R package lasso2. All other statistical analyses were performed using the SAS system, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

AA patients had a lower mean blood hemoglobin, serum ALT, and total serum bilirubin, and less hepatic steatosis in pretreatment liver biopsies than CA patients (Table 1) (4). Mean serum creatinine was higher in AA, but creatinine clearance did not differ between AA and CA. The IL28B SNP (rs12979860) C/C genotype was more frequent in CA; non-C/C (i.e. C/T and T/T) genotypes were more frequent in AA (7). Mean adherence to both peginterferon and ribavirin from week 1 to 24 by AA and CA exceeded 90 %. Yet, week 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 (SVR) response rates were lower in AA (4). Similar to an earlier study of 361 VIRAHEP-C study participants (188 CA and 173 AA), CA with the SNP C/C genotype had higher WK24VR (C/C: 93%; C/T: 70%; T/T: 50%; P = 0.005) and SVR (C/C: 71 %; C/T: 52 %; T/T: 37 %; P = 0.05) rates than CA patients with non-C/C genotypes (6). Neither WK24VR (C/C: 78 %; C/T: 60 %; T/T: 47 %; P = 0.13) nor SVR (C/C: 44 %; C/T: 40 %; T/T: 32 %; P = 0.5) differed by SNP genotype in AA (6).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variablesa | AA (n=71) | CA (n=73) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%)b | 51 (71.8) | 54 (74.0) | 0.77 |

| Age (years) | 48.1 (7.2) | 47.7 (7.2) | 0.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.4 (6.9) | 29.8 (6.1) | 0.6 |

| Baseline HCV RNA (×106IU/ml), median (IQR) | 2.4 (0.4, 4.5) | 2.5 (0.4, 5.5) | 0.84 |

| Neutrophil count (103 cells/mm3) | 3.4 (1.5) | 3.5 (1.6) | 0.18 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dl) | 14.4 (1.2) | 15.3 (1.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Platelet count (103 cells/mm3) | 229 (73) | 218 (63) | 0.34 |

| ALT (IU/l), median (IQR) | 54.0 (39.0, 81.0) | 76.0 (54.0, 129.0) | .0003 |

| AST (IU/l), median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0, 64.0) | 52.0 (39.0, 74.0) | 0.068 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl), median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.014 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.15) | 0.03 |

| Cr clearance (ml/min), median (IQR) | 108.67 (95.28, 141.32) | 117.37 (98.92, 144.14) | 0.29 |

| Liver histology scores | |||

| HAI (I + II + III) Inflammation | 8.2 (2.6) | 8.1 (2.8) | 0.87 |

| Ishak fibrosis score, 0–6 | 2.0 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.4) | 0.69 |

| Fat score | 0.3 (0.52) | 0.6 (0.74) | 0.005 |

| Initial RBV dose (mg/kg) | 12.9 (2.0) | 13.5 (2.0) | 0.08 |

| % Maximum dose, week 1–24 | |||

| Peginterferon | 96% (7) | 96% (7) | 0.89 |

| Ribavirin | 97% (4) | 98% (3) | 0.15 |

| SNP rs12979860 genotype | < 0.0001 | ||

| C/C | 9 (13%) | 31 (47%) | |

| C/T | 40 (59%) | 27 (41%) | |

| T/T | 19 (28%) | 8 (12%) | |

| Undetected serum HCV RNA | |||

| Week 4 | 6% | 16% | 0.04 |

| Week 12 | 48% | 67% | 0.02 |

| Week 24 | 58% | 78% | 0.009 |

| Week 48 | 46% | 71% | 0.002 |

| Week 72 (SVR) | 37% | 55% | 0.03 |

AA, African Americans; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CA, Caucasian Americans; HAI, histological activity index (knodell); HCV, hepatitis C virus; IQR, interquartile range; RBV, ribavirin; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Continuous variables expressed as mean (s.d.) or median (IQR) and compared with t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, respectively.

Compared with χ2 tests.

AA have less ribavirin exposure than CA

AA patients had lower ribavirin plasma concentrations at weeks 1, 2, and 4 (Figure 1) and less cumulative ribavirin exposure (AUC) at weeks 0–1 (AUC0–7), 0–2 (AUC0–14), 0–4 (AUC0–28), 0–8 (AUC0–72), and 0–12 (AUC0–84) (Table 2) than did CA. Consistent with less ribavirin exposure, AA patients had a slower decline in blood hemoglobin from week 0 to 4 and higher hemoglobin concentrations from week 1 (day 7)–24 (day 168) (P < 0.01 at each time point) (Supplementary Figure S1 online).

Figure 1.

Ribavirin (RBV) plasma concentrations in African Americans (AA) and Caucasian Americans (CA) during peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin treatment. Ribavirin concentrations were measured by LC-MS/MS as described in Methods. Results at each time were compared by t-tests. s.e.m., standard error of mean.

Table 2.

Ribavirin exposure (AUC) from week 1–24 in AA and CAa

| AUC (ng/ml/day) | AA (n=71) | CA (n=73) | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–7 | 4,142±205 | 5,117±224 | 0.002 |

| AUC0–14 | 13,650±647 | 16,694±723 | 0.002 |

| AUC0–28 | 37,199±1,752 | 44,338±1,779 | 0.005 |

| AUC0 –56 | 93,634±4,342 | 106,598±3,700 | 0.02 |

| AUC0–84 | 155,541±7,157 | 173,738±5,821 | 0.04 |

| AUC0–168 | 337,390±15,385 | 370,456±12,637 | 0.10 |

AA, African Americans; AUC, area under the concentration vs. time curve; CA, Caucasian Americans.

Data expressed as mean AUC±s.e.m.

Results compared using t-tests.

WK24VR and SVR associated with higher ribavirin exposure in AA

AA patients who experienced a WK24VR had higher ribavirin plasma concentrations from week 1 to 24 (Figure 2a) and greater ribavirin exposure at weeks 0–1 (AUC 0–7), 0–2 (AUC0–14), 0–4 (AUC0–28), 0–8 (AUC0–72), 0–12 (AUC0–84), and 0–24 (AUC0–168) compared with AA with a WK24NR (Table 3). Similarly, AA patients with a SVR had higher ribavirin plasma concentrations at weeks 1 and 2 (Figure 2c) and greater ribavirin exposure (Supplementary Table S1 online) at weeks 0–1 (P = 0.01), 0–2 (P = 0.02), and 0–4 (P = 0.08) than those without a SVR. In contrast, ribavirin plasma concentrations and exposure levels did not differ by WK24VR (Figure 2b; Table 3) and SVR in CA (Figure 2d; Supplementary Table S1 online). Ribavirin plasma concentrations and exposure levels also did not differ between AA and CA with a WK24VR (Table 3) and SVR (Supplementary Table S1 online). In contrast, AA with a WK24NR (Table 3) had lower ribavirin concentrations and exposures than CA with a WK24NR at each time point. Among patients without a SVR (Supplementary Table S1 online), the AA patients had lower ribavirin plasma concentrations at weeks 1 (P = 0.006) and 2 (P = 0.05), and less exposure at weeks 0–1 (P = 0.006), 0–2 (P = 0.01), 0–4 (P = 0.03), and 0–8 (P = 0.07).

Figure 2.

Ribavirin (RBV) plasma concentrations and WK24VR (a, b) and sustained virologic response (SVR) (c, d) in African Americans (AA) and Caucasian Americans (CA). Ribavirin concentrations were measured as described in Methods and Figure 1. Results within racial groups at each time were compared between responders and nonresponders by t-tests.

Table 3.

Ribavirin exposure (AUC) by WK24VR in AA and CAa

| AUC (ng/ml/day) | AA WK24VR (n=98) | AA WK24NR (n=46) | P valueb | CA WK24VR (n=98) | CA WK24NR (n=46) | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–7 | 4,702±261 | 3,875±278 | 0.001 | 5,193±214 | 4,854±699 | 0.52 |

| AUC0–14 | 15,256±821 | 11,455±915 | 0.003 | 16,825±676 | 16,226±2,314 | 0.73 |

| AUC0–28 | 40,844±2,260 | 32,217±2,536 | 0.014 | 44,862±1,731 | 42,468±5,402 | 0.58 |

| AUC0–56 | 103,666±5,758 | 79,923±6,013 | 0.006 | 108,141±3,688 | 101,102±10,785 | 0.43 |

| AUC0–84 | 174,142±9,437 | 130,119±9,284 | 0.002 | 175,177±5,924 | 168,611±16,528 | 0.64 |

| AUC0–168 | 380,394±20,829 | 278,619±18,116 | <0.001 | 370,210±1,3127 | 371,652±35,003 | 0.96 |

AA, African Americans; AUC, area under the concentration vs. time curve; CA, Caucasian Americans.

Data expressed as mean AUC±s.e.m.

Results compared using t-tests.

Variables associated with ribavirin AUC 0–7, WK24VR and SVR

Baseline patient characteristics associated with WK24VR, SVR, and ribavirin exposure (AUC) were identified using multivariable regression analysis; 37 baseline variables that differed between AA and CA or between WK24VR and WK24NR in univariate analyses (P ≤ 0.25) (Tables 1 and 2, Figures 1 and 2; Supplementary Table S2 online) were studied. Ribavirin AUC0–7 (P = 0.0008), IL28B SNP genotype C/C (vs. non-C/C) (odds ratio, OR: 9.0; 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI): 2.5–32.3; P = 0.0008), age (P = 0.03), platelet count (OR: 1.01; 95 %: CI 1.001–1.015; P = 0.03) and an interaction between AUC0–7 and age (P = 0.0017) were associated with WK24VR. Ribavirin AUC0–7, IL28B SNP genotype C/C, age, platelet count and an interaction between AUC0–7 and platelet count predicted SVR. Patient race (P < 0.003) was the only variable associated with ribavirin AUC0–7.

Ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds predict higher WK24VR and SVR

By means of ROC analysis, ribavirin AUC0–7 ≥ 4,095 ng/ml × day (Supplementary Figure S2A online) and ≥ 4,480 ng/ml × day (Supplementary Figure S2B online) were threshold or best cutoff values for WK24VR and SVR, respectively, in the total sample. Forty-nine percent of AA and 70 % of CA had a ribavirin AUC0–7 >4,095 ng/ml × day (P = 0.01 χ2); 44 % of AA and 64 % of CA had a ribavirin AUC0–7 ≥ 4,480 ng/ml × day (P = 0.03 χ2). Areas under the ROC (AUROC) for WK24VR and SVR were 0.71 (Supplementary Figure S2A online) and 0.65 (Supplementary Figure S2B online), overall. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of a ribavirin AUC0–7 ≥ 4,095 for WK24VR were 0.69, 0.70, 0.83, and 0.52, respectively. Sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values of an AUC0–7 ≥ 4,480 for SVR were 0.59, 0.65, 0.59, and 0.65, respectively. The best AUC0–7 cutoff values for both WK24VR and SVR were lower in AA (AA: 4,060 and 4375 ng/ml × day; CA: 4,585 and 4,935 ng/ml × day). Nonetheless, AUROC for both WK24VR and SVR were greater in AA (AUROC 0.73 and 0.68, respectively) than in CA (AUROC 0.62 and 0.57, respectively) (Supplementary Figure S2 online). Thus, the specified ribavirin exposure thresholds were better at discriminating responders from non-responders among AA.

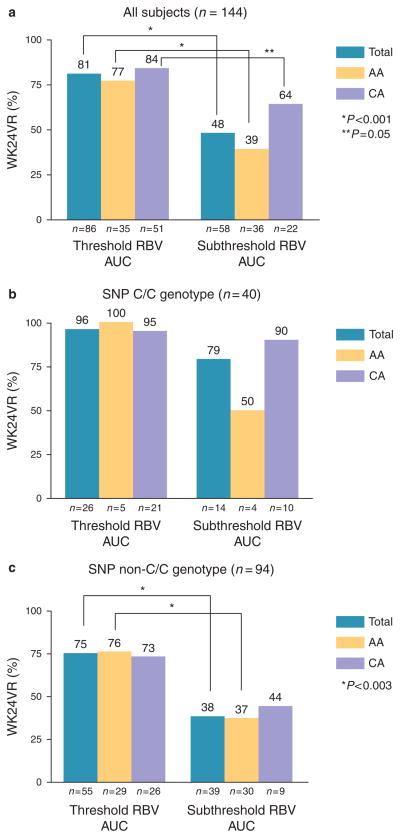

A ribavirin AUC0–7 ≥ 4,095 was associated with a higher WK24VR in the total sample, and in both AA and CA subgroups (Figure 3a). An AUC0–7 ≥ 4,480 was associated with a higher SVR overall, but only in AA when the races were analyzed separately (Figure 4a). Mean ribavirin exposure during week 1 did not differ between AA and CA with a ribavirin AUC0–7 ≥ 4,095 ng/ml × day (AA: 5,596 ± 1,033; CA: 5,920 ± 1,710; P = 0.32) and a ribavirin AUC0–7 ≥ 4480 ng/ml × day (AA: 5,770± 966, CA: 6,139 ± 1,703; P = 0.28). Among patients with subthreshold ribavirin AUC0–7 levels, the AA patients had lower exposure than the CA patients (ribavirin AUC0–7 < 4,095 ng/ml × day: AA: 2,728 ± 887, CA: 3,255 ± 668; P = 0.019; ribavirin AUC0–7 < 4,480 ng/ml × day: AA: 2,879 ± 959, CA: 3,474 ± 729; P = 0.007). WK24VR (Figure 3a) and SVR (Figure 4a) rates did not differ between AA and CA with threshold ribavirin AUC0–7 levels. In patients with subthreshold ribavirin AUC0–7 levels, on the other hand, the AA patients had lower WK24VR (P = 0.07) and SVR (P = 0.02) rates compared with the CA patients. Using race-specific ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds for WK24VR (AA ≥ 4,060; CA ≥ 4,585) and SVR (AA ≥ 4,375; CA ≥ 4,935) did not change the results (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Ribavirin (RBV) area under concentration vs. time curve (AUC)0-7 threshold (≥4095 ng/ml × day) predict WK24VR. WK24VR for the total sample (a) and patients with interleukin-28B (IL28B) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) CC (b) and non-CC (c) genotypes categorized by AUC0-7 and race. Response rates between ribavirin exposure categories were compared using the χ2tests.

Figure 4.

Ribavirin (RBV) area under concentration vs. time curve (AUC)0-7 threshold (≥4480 ng/ml × day) predict sustained virologic response (SVR). SVR for total sample (a) and patients with interleukin-28B (IL28B) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) CC (b) and non-CC (c) genotypes stratified by AUC0-7 category and race. Response rates between ribavirin exposure categories were compared using the χ2 tests.

WK24VR (Figure 3b) and SVR (Figure 4b) rates did not differ by ribavirin AUC0–7 category (i.e. threshold vs. subthreshold) in patients with the IL28B SNP C/C genotype, both overall and within the AA and CA subgroups. In contrast, a threshold ribavirin AUC0–7 level was associated with higher WK24VR (Figure 3c) and SVR (Figure 4c) rates overall, and among AA patients with IL28B SNP non-CC genotypes. Similar trends were observed in the CA patients with non-C/C, but the differences were not significant (possibly because of a small sample size). In addition, there were no racial differences in WK24VR (Figure 3b,c) and SVR (Figure 4b,c) rates among patients in the same ribavirin AUC0–7 and IL28B SNP genotype categories.

Ribavirin exposure and early viral kinetics

Consistent with previous reports, responders to peginterferon plus ribavirin exhibited two distinct phases of HCV RNA decay from day 0 to 28 (Figure 5a) (6,23–25). The decline in HCV RNA from day 0 to 2 (phase 1) is thought to indicate interferon alpha’s effectiveness at blocking HCV replication. Phase 2 (day 7–28) is hypothesized to reflect both interferon effectiveness and clearance of HCV-infected cells, and is a strong predictor of SVR. The fall in HCV RNA on day 1 and 2 (phase 1) did not differ between AA and CA, but AA had lesser declines on days 7, 14, and 28 (phase 2) (Figure 5a). In a prior study, ribavirin had no effect on phase 1 kinetics when combined with peginterferon alfa compared with peginterferon alone. Instead, ribavirin appeared to prevent an increase (rebound) in HCV RNA from day 2 to 7 and to accelerate the fall in HCV RNA from day 7 to 28 (phase 2) when added to peginterferon (26). Incidentally, AA with subthreshold ribavirin AUC0–7 (< 4,095 ng/ml × day) (Figure 5b) exhibited a 0.2 log10 IU/ml rebound in HCV RNA from day 2 to 7. By comparison, AA with threshold ribavirin AUC0–7 (≥ 4,095 ng/ml × day) experienced a 0.2 log10 IU/ml decline in HCV RNA from day 2 to 7 (P = 0.016) and greater falls in HCV RNA on days 7 (P = 0.01), 14 (P = 0.01), and 28 (P = 0.07) (Figure 5b). Early HCV RNA kinetics did not differ by ribavirin AUC0–7 threshold in CA patients. Furthermore, the AA and CA patients with threshold ribavirin AUC had similar HCV RNA kinetics.

Figure 5.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA kinetics day 0–28. Serum HCV RNA concentrations were measured with the Roche Amplicor Monitor Assay, version 2. Results are shown by race (a), race and ribavirin area under concentration vs. time curve (AUC)0-7 (b), and interleukin-28B (IL28) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype and ribavirin (RBV) AUC0-7 (c, d) in AA. Differences in HCV RNA log10 IU/ml relative to day 0 at each time point were compared between using t-tests (a, c, d) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) (b). AA, African Americans; CA, Caucasian Americans. Threshold ≥4095 ng/ml × day.

Stratified by IL28B SNP genotype, the decline in HCV RNA from day 0 to 28 did not vary by ribavirin AUC0–7 category in the AA (Figure 5c) and CA patients (Supplementary Figure S3A online) with CC genotypes. Indeed, AA with subthreshold ribavirin AUC0–7 had greater declines in HCV RNA on days 1 and 2 (phase 1) compared with AA with threshold ribavirin AUC0–7 levels (Figure 5c), but experienced an HCV RNA rebound from day 2 to 7 and a comparable decline from day 7 to 28 (phase 2). HCV RNA kinetics from day 0 to 2 and day 2 to 7 did not vary by ribavirin AUC0–7 category in AA with non-CC genotypes (Figure 5d). Yet, AA with threshold levels exhibited a greater fall in HCV RNA from day 7 to 28 (Figure 5d). Among CA with non-CC, those with subthreshold AUC0–7 had greater declines in HCV RNA on days 1 and 2, but experienced an HCV RNA rebound from day 2 to 7 and equivalent log10 declines from day 7 to 28 (Supplementary Figure S3B online).

DISCUSSION

In patients with HCV genotype 1 infections and exceptional adherence to weight-based ribavirin plus peginterferon treatment, the AA patients had lower ribavirin plasma exposure (AUC) from week 1 to 12, and were less likely to achieve ribavirin plasma exposure thresholds during the first week (AUC0–7) that predicted WK24VR and SVR. Remarkably, racial differences in WK24VR and SVR rates were eliminated in patients who reached these ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds. Ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds were associated with WK24VR and SVR independently of IL28B SNP genotype. However, achieving the specified ribavirin exposure thresholds increased response rates preferentially in the AA patients with the less favorable IL28B non-CC genotypes. These results provide important new insights into the basis for the racial disparity in treatment responses to peginterferon and ribavirin treatment for HCV genotype 1.

Consistent with prior studies, we found substantial variability in ribavirin plasma concentrations and cumulative ribavirin exposure (AUC), even in patients with >90 % medication adherence (14–16). Differences in ribavirin plasma concentrations (week 1–4) and ribavirin AUC from week 1 to 12 between the AA and CA patients with similar drug adherence is a novel finding. Ribavirin accumulation was independently associated with patient age, body weight, body mass index, gender, initial ribavirin dose, and creatinine clearance in previous studies (12,13). AA had a higher estimated mean serum creatinine clearance and received a marginally lower (P = 0.09) weight-normalized ribavirin dose. However, creatinine clearance did not differ between AA and CA. In a multi variable regression model that included these variables, patient race was the only variable independently associated with ribavirin exposure during the first treatment week. In a population pharmacokinetic model, the apparent peripheral volume of distribution for ribavirin was 1.5 times greater in the AA patients compared with the CA patients (Jin et al. (20), accepted for publication). This probably explains for the racial divergence in ribavirin plasma concentrations and exposure, though the underlying mechanism(s) is unknown. Up to 50 % of patients experience a decline in blood hemoglobin to < 12 g/dl during peginterferon combination therapy, because of hemolysis linked to ribavirin’s dose and plasma concentration (12,13,27,28). Racial differences in hemoglobin kinetics in the present study correlated with variation in ribavirin exposure. Indeed, AA had a slower decline in blood hemoglobin from week 0 to 4 and a higher hemoglobin nadir during the first 24 weeks, despite lower pretreatment hemoglobin.

Previous studies have found higher ribavirin plasma concentrations and exposure (AUC) in patients with an SVR compared with non-SVR following peginterferon combination treatment (12–16). A ribavirin AUC0–12hr >3,014 ng/ml × h after the first dose was associated with 12.5 greater odds for SVR relative to lower exposure levels in one study (16). A ribavirin plasma concentration>2,010 ng/ml at week 4 was optimum for SVR in patients with HCV genotype 1 in another (29). In the present study, ribavirin exposure ≥ 4,095 and ≥ 4,480 ng/ml × day during the first week (AUC0–7) were thresholds for WK24VR and SVR, respectively. Sequential ribavirin plasma concentrations and ribavirin AUC levels (AUC0–7, 0–14, 0–28, etc.) were highly correlated (r coefficient >0.95 each; P < 0.001); thus, the ribavirin concentration at the week 1 predicted the steady-state (week 8–24) level. Patients who achieved the specified ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds had higher WK24VR and SVR rates than those with subthreshold levels, with the biggest differences observed in AA patients. The AA patients were almost 50 % less likely to have a threshold ribavirin AUC0–7 than the CA patients. Yet, WK24VR and SVR rates did not differ between AA and CA with threshold ribavirin AUC0–7. Among patients with subthreshold ribavirin AUC0–7 levels, on the other hand, the AA patients had significantly lower ribavirin AUC0–7 levels and response rates. It is noteworthy that ribavirin plasma concentrations and exposure varied by WK24VR and SVR only in the AA patients. This finding differs from previous studies, and may be explained by the small number of AA in prior studies as well as differences in study designs. To avoid racial differences in ribavirin adherence reported in VIRAHEP-C (4), we selected patients who had received >90 % of the maximum doses of both medications from week 1 to 24. In contrast, previous studies included patients who received either < 80% of the maximum weight-based ribavirin or an 800 mg (i.e., flat) ribavirin dose (12,13,30).

IL28B gene-related SNP rs12979860 on chromosome 19 is strongly associated with response to peginterferon and ribavirin in US patients with HCV genotype 1 infections (7,21). Patients with the C/C genotype have more rapid declines in serum HCV RNA during the first (day 0–2) and second (day 7–28) phases of early viral kinetics, and two- to three-fold higher response rates at weeks 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 (SVR) than those with the non-C/C (i.e. T/T and C/T) genotypes (6,21). The C allele is much less frequent in AA than in CA, and this difference is estimated to explain >50 % of the racial disparity in early viral kinetics (day 0–28) and 30–50% of the disparity in SVR (6,7,21). The present study shows that variability in ribavirin AUC0–7 can explain much of the remaining difference between AA and CA in peginterferon and weight-based ribavirin treatment efficacy for HCV genotype 1. Ribavirin AUC0–7, SNP genotype, age, and platelet count were associated with WK24VR and SVR in multivariable regression analysis. Controlling for these four variables, patient race did not predict WK24VR and SVR. Yet, achieving threshold ribavirin AUC0–7 augmented WK24VR and SVR most significantly in AA with IL28B SNP non-C/C genotypes. Compared with subthreshold ribavirin exposure, the beneficial effect threshold ribavirin exposure in AA was associated with greater reductions in HCV RNA during the early viral kinetic phase 2 (day 7–28) that is known to predict SVR. Dixit et al. (31) proposed that the need for ribavirin during phase 2 is inversely correlated with interferon alpha’s effectiveness or the vigor of the phase 1 response. Thus, higher interferon effectiveness in patients with the C/C genotype (6,20). Probably explains why phase 2 kinetics, WK24VR and SVR did not differ by ribavirin AUC0–7 in C/C patients.

This study has some limitations. The sample size provided adequate statistical power to detect differences in ribavirin exposure between AA and CA. However, few CA patients had suboptimum ribavirin exposure based on ROC analysis. Because of racial differences in IL28B SNP allele frequencies, small numbers of AA with C/C and CA with non-C/C genotypes were studied. As a result, statistical power was limited in analyses of treatment responses by ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds in CA and in each race stratified by IL28B SNP genotype. This might explain why WK24VR and SVR rates did not differ by ribavirin AUC0–7 threshold in CA with non-C/C. In addition, we studied patients with exceptional adherence to both peginterferon and ribavirin. Thus, a larger study with a full range of peginterferon and ribavirin adherence observed in the VIRAHEP-C would be required to completely define the importance of ribavirin exposure to treatment outcomes in relation to IL28B SNP variation. Functional polymorphisms (rs1127354 and rs7270101) in the inosine triphosphatase (ITPA) gene on chromosome 20 were associated with the extent of decline of blood hemoglobin at week 4 in 304 VIRAHEP-C study participants (167 CA and 137 AA) (32). Minor alleles (ITPA deficiency) provided protection against anemia. However, the frequency of ITPA deficiency was similar in CA and AA and did not predict SVR in the VIRAHEP-C (32). Lower serum interferon- gamma inducible protein 10 (IP10) levels (< 600 pg/ml) during pretreatment were associated with an increased SVR following peginterferon and ribavirin treatment for HCV genotype 1 in both AA (n = 134) and CA (n = 138) overall and stratified by IL28B SNP genotypes in VIRAHEP-C (33). AA had higher pretreatment IP10 levels. However, variation in pretreatment IP-10 levels did not explain the racial difference in SVR (33). Thus, we did not analyze these markers.

In conclusion, the present study shows that current weight-based ribavirin dosing guidelines result in suboptimal ribavirin plasma exposure for WK24VR and SVR during peginterferon plus ribavirin therapy in 60 % of AA and 36 % of CA patients with HCV genotype 1 infections and exceptional medication adherence. The racial difference in ribavirin exposure appears to be related to a larger volume of ribavirin distribution in AA (20). Ironically, lower ribavirin exposure in AA was compounded by a higher frequency of IL28B SNP rs12979860 non-C/C genotypes that are associated with lower interferon effectiveness (phase 1) and a greater need for ribavirin during phase 2 of early viral kinetics. IL28B SNP non-C/C genotypes also predict a poorer response to HCVNS3 protease inhibitors combined with peginterferon and ribavirin, the new standard for HCV genotype 1 treatment (8,9). Future studies should determine the importance of ribavirin pharmacokinetic variability to racial disparities in treatment responses to HCVNS3 protease inhibitors and other direct-acting antiviral treatments for HCV.

Supplementary Material

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

Peginterferon plus ribavirin treatment is less effective for hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infections in African Americans (AA) relative to Caucasian Americans (CA).

Up to 50 % of racial difference in HCV eradication is explained by allelic variation in SNP near the interleukin 28B (IL28B) gene on chromosome 19.

The basis for the remaining disparity is unknown.

There is no difference in peginterferon pharmacokinetics from week 1 to 24 between AA and CA.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

Ribavirin plasma concentrations and drug exposure (area under the concentration vs. time curve, AUC) from week 1 to 24 were compared between AA and CA, who were >90 % adherent to peginterferon and ribavirin.

Fewer AA achieved ribavirin exposure (AUC0–7) thresholds for week 24 and week 72 (sustained virologic response, SVR) responses.

There were no racial differences in week 24 and SVR response rates in patients who met the ribavirin AUC0–7 thresholds.

Ribavirin AUC0–7 predicts WK24VR and SVR independently of IL28B single-nucleotide polymorphism genotype.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was sponsored by NIDDK 1 R21 DK078100-01, R01 DK066920-01and 1 K24 DK072036-01. The VIRAHEP-C study was a cooperative agreement funded by the NIDDK with a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) with Roche Laboratories Grant numbers: U01 DK60329, U01 DK60340, U01 DK60324, U01 DK60344, U01 DK60327, U01 DK60335, U01 DK60352, U01 DK60342, U01 DK60345, U01 DK60309, U01 DK60346, U01 DK60349, and U01 DK60341. Other support: National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) General Clinical Research Centers Program grants: M01 RR00645 (New York Presbyterian), M02 RR000079 (University of California, San Francisco), M01 RR16500 (University of Maryland), M01 RR000042 (University of Michigan), and M01 RR00046 (University of North Carolina). The data analyses and interpretation and manuscript preparation were performed by the authors listed.

Footnotes

Potential competing interests : John McHutchison: employed by Gilead Sciences. Charles D. Howell: Roche (advisory board); Vertex. (advisory board; research grant); Boehringer Ingelheim (research grant); Bristol Meyer Squibb (research grant); Janssen (advisory board).

The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/ajg

Guarantor of the article: Charles D. Howell, MD.

Specific author contributions: Acquisition of data; analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; statistical analysis; technical support: R. Jin; statistical analysis: L. Cai; statistical analysis: M. Tan; IL28B SNP genotype data: J McHutchison; study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; technical support; study supervision: T. Dowling; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; obtained funding; study supervision: C. Howell.

References

- 1.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–65. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muir AJ, Bornstein JD, Killenberg PG. Peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in blacks and non-hispanic whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2265–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conjeevaram HS, Fried MW, Jeffers LJ, et al. Peginterferon and ribavirin treatment in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C genotype 1. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:470–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoofnagle JH, Wahed AS, Brown RS, Jr, et al. Early changes in Hepatitis C virus (HCV) levels in response to peginterferon and ribavirin treatment in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1112–20. doi: 10.1086/597384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howell CD, Gorden A, Ryan KA, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism upstream of interleukin 28B associated with phase 1 and phase 2 of early viral kinetics in patients infected with HCV genotype 1. J Hepatol. 2012;56:557–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Bisceglie AM, Fan X, Chambers T, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and hepatitis C viral kinetics during antiviral therapy: the null responder. J Med Virol. 2006;78:446–51. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howell CD, Dowling TC, Paul M, et al. Peginterferon pharmacokinetics in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:575–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jen JF, Glue P, Gupta S, et al. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ther Drug Monit. 2000;22:555–65. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200010000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snoeck E, Wade JR, Duff F, et al. Predicting sustained virological response and anaemia in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:699–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larrat S, Stanke-Labesque F, Plages A, et al. Ribavirin quantification in combination treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:124–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.124-129.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arase Y, Ikeda K, Tsubota A, et al. Significance of serum ribavirin concentration in combination therapy of interferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. Intervirology. 2005;48:138–44. doi: 10.1159/000081741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loustaud-Ratti V, Alain S, Rousseau A, et al. Ribavirin exposure after the first dose is predictive of sustained virological response in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2008;47:1453–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson IM, Brown RS, Jr, Freilich B, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b and weight-based or flat-dose ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2007;46:971–81. doi: 10.1002/hep.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brennan BJ, Morcos PN, Wang K, et al. The pharmacokinetics of peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in African American, Hispanic and Caucasian patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1209–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Xu C, Yan R, et al. Sensitive and specific LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous measurements of viramidine and ribavirin in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;832:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin R, Fossler MJ, McHutchison JG, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection. AAPS J. 2012;14:571–80. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, et al. Interleukin-28B polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:120,9.e18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian GL, Tang ML, Fang HB, et al. Efficient methods for estimating constrained parameters with applications to lasso logistic regression. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2008;52:3528–42. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girard C, Ravallec M, Mariller M, et al. Effect of the 5′ non-translated region on self-assembly of hepatitis C virus genotype 1a structural proteins produced in insect cells. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3659–70. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrmann E, Lee JH, Marinos G, et al. Effect of ribavirin on hepatitis C viral kinetics in patients treated with pegylated interferon. Hepatology. 2003;37:1351–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahari H, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS. Triphasic decline of hepatitis C virus RNA during antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2007;46:16–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.21657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feld JJ, Lutchman GA, Heller T, et al. Ribavirin improves early responses to peginterferon through improved interferon signaling. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:154,62.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balan V, Schwartz D, Wu GY, et al. Erythropoietic response to anemia in chronic hepatitis C patients receiving combination pegylated interferon/ribavirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Longo DL. Definition and management of anemia in patients infected with hepatitis C virus. Liver Int. 2006;26:389–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maynard M, Pradat P, Gagnieu MC, et al. Prediction of sustained virological response by ribavirin plasma concentration at week 4 of therapy in hepatitis C virus genotype 1 patients. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:607–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, et al. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dixit NM, Layden-Almer JE, Layden TJ, et al. Modelling how ribavirin improves interferon response rates in hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2004;432:922–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson AJ, Fellay J, Patel K, et al. Variants in the ITPA gene protect against ribavirin-induced hemolytic anemia and decrease the need for ribavirin dose reduction. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1181–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darling JM, Aerssens J, Fanning G, et al. Quantitation of pretreatment serum interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10 improves the predictive value of an IL28B gene polymorphism for hepatitis C treatment response. Hepatology. 2011;53:14–22. doi: 10.1002/hep.24056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.