Abstract

Stigma negatively affects the health of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). Negative attitudes and discriminatory actions towards PLWHA are thought to be based, among other factors, on stigma towards sexual minorities and beliefs about personal responsibility. Yet, there is little evidence to support these linkages and explain how they take place, especially among Latinos. This study analyzes attitudes towards PLWHA among 643 Latino gay/bisexual men and transgender (GBT) people. It examines whether discriminatory actions are predicted by beliefs about personal responsibility and internalized homosexual stigma. Results indicate that Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA is associated with HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs and Internalized Homosexual Stigma. Further, HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs partially mediates the relationship between Internalized Homosexual Stigma and Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA. Latino GBT persons who have internalized negative views about homosexuality may project those onto PLWHA. They may think PLWHA are responsible for their serostatus and, hence, deserving of rejection.

Stigma towards people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) is an important public health problem because it is widespread, hinders prevention efforts, negatively affects the health of those being stigmatized (Herek, Chopp, & Strohl, 2007; National Institutes of Health, 2002), and the number of PLWHA will continue to increase (Prejean et al., 2011; Torian, Chen, Rhodes, & Hall, 2011). Society's negative attitudes towards PLWHA and PLWHA's reported experiences of stigma have been linked to fear of disclosure of HIV status and testing, psychological distress, and lack of social support (Holtgrave, McGuire, & Milan, 2007; Mak et al., 2007; McCrae et al, 2007; Molina & Ramirez-Valles, 2012). Many PLWHA report internalized stigma in the form of guilt and shame about their status and/or difficulty in telling others about their infection (Kalichman et al., 2009). This internalized stigma contributes to depression, anxiety, and hopelessness (Lee, Kochman, & Sikkema, 2002). There is also evidence that HIV/AIDS stigma is a barrier to utilizing prevention and treatment services (Herek, Capitanio, & Widaman, 2003). Understanding and addressing stigma towards PLWHA, therefore, is an essential part of combating the epidemic.

Although negative attitudes have declined, the general public continues to believe that PLHWA are responsible for their illness (Des Jarlais, Galea, Tracy, Tross, & Vlahov, 2006; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006). Further, much of the research on attitudes towards PLWHA has been done on the general population, with the goal of assessing attitudes and their correlates. This research has found that stigma associated with HIV is rooted in factors such as negative feelings about gay men, or homosexual stigma, and personal responsibility (Connors & Hely, 2007b; Greene & Banerjee, 2006; Herek & Capitanio, 1999).

Despite the fact that more than half of all PLWHA in the United States are gay men or men who have sex with men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013), little is known about gay men's attitudes and discriminatory actions towards PLWHA. There is a lack of empirical evidence about attitudes towards PLWHA within ethnic minority gay male communities, who are notably affected by HIV infection (Marin, 2003; Parker & Aggleton, 2003; Rao, Pryor, Gaddist, & Mayer, 2008). Among Latino gay men, there is evidence that HIV/AIDS stigma is a barrier to getting tested for HIV (Brooks, Etzel, Hinojos, Henry, & Perez, 2005) and participating in HIV prevention programs (Ramirez-Valles & Brown, 2003). Experienced (or enacted) HIV/AIDS stigma has been linked to social isolation, low self-esteem, and psychological well-being in HIV-positive Latino gay men (Diaz, 2006; Molina & Ramirez-Valles, 2012). Yet, we have limited knowledge on the extent and manner in which HIV/AIDS stigma manifests within this community. The purpose of this study is to address such a gap in the literature by analyzing attitudes towards PLWHA among Latino gay/bisexual men and transgender (male to female) (GBT) people. Specifically, we examine whether beliefs about personal responsibility and internalized homosexual stigma predict discriminatory actions.

Stigma and attribution theory

Stigma refers to a process by which individuals are devalued and treated as less than others (Goffman, 1963). It involves overt discrimination (from the stigmatizer), labeling and separation (e.g., “the other”), and attribution of unfavorable qualities (e.g., promiscuous, immoral; Link & Phelan, 2001). Attribution theory is a helpful framework to unpack how stigmatization may take place (Weiner, 1995). It posits that discriminatory behavior is determined by a cognitive-emotional process (Corrigan, Markowitz, Watson, Rowan, & Kubiak, 2003; Johnson, Mullick, & Mulford, 2002). Individuals make attributions about the cause and controllability of a particular characteristic (e.g., being gay) or illness (e.g., AIDS) aversion, anger) that influence behavioral reactions (e.g., rejection). Thus, a refusal to date a PLWHA, for example, may be shaped by personal responsibility beliefs, based on the idea that HIV is a caused by sexually “promiscuous behavior.”

In the case of HIV/AIDS, beliefs of personal responsibility account for much of the stigma directed at PLWHA both within and outside of gay male populations (Diaz, 2006; Herek, Capitanio, & Widaman, 2002; von Collani, Grumm, & Streicher, 2010). However, this attribution model may take on a different meaning depending on the population to which it is applied. For the general population, judgments about personal responsibility are confounded by negative attitudes towards gay men (Herek, 2002), wherein negative attitudes towards gay men predict negative attitudes towards PLWHA (von Collani et al., 2010). Gay men living with HIV/AIDS are deemed as personally responsible for their condition, because they are thought to have chosen to engage in male-male sex (Alonzo & Reynolds, 1995; Herek & Capitanio, 1999).

For the GBT population, the connection between attitudes towards homosexuality, or gender nonconformity, and those towards PLHWA might be slightly different. We propose that negative attitudes towards homosexuality (e.g., homosexual stigma) are partly manifested as internalized homosexual stigma in GBT people and that this drives beliefs about HIV/AIDS personal responsibility, which in turn influence discriminatory actions towards PLWHA. As described by Herek (2007), internalized homosexual stigma refers to GBT individuals' incorporation of society's negative views of homosexuality into their own identity. It may result in a range of feelings, from self-doubt and shame to self-hatred (Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, & Meyer, 2008). Thus, when GBT people hold negative views of themselves as sexual minorities, they may be likely to project these feelings to the larger GBT population and, by association, to PLWHA. For instance, a gay man's belief that gay men are promiscuous may translate into blame and rejection of PLWHA.

Attitudes towards PLWHA Among GBT People

There is some evidence of a division among gay men based on serostatus, where those who are HIV-negative are perceived to only associate with other HIV-negative gay men, thereby alienating HIV-positive gay men from their own wider community (Botnick, 2000a; Botnick, 2000b; Courtenay-Quirk, Wolitski, Parsons, & Gomez, 2006). Within communities of gay men, HIV/AIDS stigma is manifested, for example, as a rejection of HIV-positive gay men as sexual partners (Smit et al., 2011).

The limited studies on mostly non-Hispanic White gay men indicate that negative attitudes towards PLWHA, while decreasing, are still widespread (Dowshen, Binns, & Garofalo, 2009; Smit et al., 2011). Among Latino gay men, stigma towards PLWHA is also pervasive (Diaz & Ayala, 2001; Ramirez-Valles, 2011). Although there have been significant improvements among Latino populations in HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment and gay rights, PLWHA and GBT people remain marginalized within these groups (Social Research Sciences Solutions, 2012). In many communities throughout Latin American and the Caribbean, PLWHA are thought of as deserving of their illness because they have engaged in “erroneous and immoral” actions, such as homosexuality and substance use (Gonzalez-Rivera & Bauermeister, 2007; Parker & Aggleton, 2003). Indeed, the larger Latino population holds negative views towards homosexuality. A little over half of them consider homosexuality a deviant sexual act (yet, half support legalization of same sex marriage; Social Research Sciences Solutions, 2012). Internalized homosexual stigma among Latino GBT may be related to discriminatory actions towards PLWHA as a result of beliefs about personal responsibility. Many HIV-negative Latino gay men believe that HIV-positive men are personally responsible for getting infected and are to blame for the spread of the disease (Diaz, 2006). They believe that that PLWHA are sexually promiscuous and not trustworthy (Diaz, 2006).

Thus, there is some evidence suggesting that Latino gay men's attitudes towards PLWHA may be rooted in attitudes towards homosexuality. In this study, we aim to move this evidence forward by examining two hypotheses: 1) Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA is positively associated with Internalized Homosexual Stigma and Personal Responsibility Beliefs; and 2) Beliefs about HIV/AIDS personal responsibility mediate the association between Internalized Homosexual Stigma and Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA.

Methods

Sample

The sample consists of Latino GBT individuals from Chicago and San Francisco recruited via Respondent-Driven Sampling (RDS). The two cities were chosen to secure diversity (e.g., country of origin) and because of their different HIV/AIDS histories. RDS is a peer referral method (Heckathorn, 1997; Heckathorn, 2002) suited to sample and recruit hidden and stigmatized populations. Sampling and recruitment details are discussed elsewhere (Ramirez-Valles, Garcia, Campbell, Diaz, & Heckathorn, 2008; Ramirez-Valles, Kuhns, Campbell, & Diaz, 2010).

The sample is made of 643 (320 in Chicago and 323 in San Francisco) Latino men who self-identified as gay, bisexual, or transgender (male-to-female). The ages ranged from 18–73 years; 170 (26.4%) of participants reported being HIV-positive. Table 1 depicts descriptive information for the sample and main study variables. We included transgender women because their experiences of stigma are comparable to those of gay and bisexual men, yet varying in level (Ramirez-Valles, 2011). Also, there is significant variation within the group of trangenders in this sample. Some of them live their daily lives as women while others only adopt some feminine features in their outlook occasionally.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for Study Variables (n = 643)

| Variable | n(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Chicago n = 320 (49.8%) | San Francisco n = 323 (50.2%) | Total | |

| Sexual/gender identity | |||

| Gay | 233 (72.8%) | 214 (66.5%) | 447 (69.6%) |

| Bisexual | 68 (21.2%) | 56 (17.4%) | 124(19.3%) |

| Transgender | 19 (5.9%) | 52 (16.1%) | 71 (11.1%) |

| Birth country | |||

| USA | 99 (30.9%) | 46 (14.2%) | 145 (22.6%) |

| Other | 221 (69.1%) | 277 (85.8%) | 498 (77.4%) |

| Serostatus | |||

| Positive | 57 (17.8%) | 113 (35.0%) | 170 (26.4%) |

| Negative | 208 (65.0%) | 184 (57.0%) | 392 (61.0%) |

| Don't know/refuse | 14 (4.3%) | 10 (3%) | 24 (3.7%) |

| Education | |||

| <HS/GED | 81 (25.3%) | 91 (28.2%) | 172 (26.7%) |

| HS/GED | 88 (27.5%) | 61 (18.9%) | 149 (23.2%) |

| Vocational school | 22 (6.9%) | 37 (11.5%) | 59 (9.2%) |

| ≥ Some college | 129 (40.3%) | 134 (41.5%) | 263 (40.9%) |

| M(SE) | |||

|

|

|||

| Age | 33.54 (0.54) | 36.72 (0.54) | 35.14 (0.54) |

| Income1 | 3.15 (0.13) | 2.75(0.13) | 2.95 (0.13) |

| Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA2 | 1.64 (0.03) | 1.52 (0.03 | 1.61 (0.03) |

| Personal Responsibility Beliefs2 | 1.67 (0.04) | 1.56 (0.04) | 1.58 (0.04) |

| Internalized Homosexual Stigma2 | 2.03 (0.03) | 1.95 (0.03) | 1.99 (0.03) |

Note.

1 = < $10K, 2 = $10–15K, 3 = $15–20K, 4 = $20–25K, 5 = $30–35K, 6 = $35–410K…14 = $70–75K, $15 = > $75K.

Range was 1–4: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, and 4 = Strongly Agree.

Measures

Data were collected using computer-assisted self-interviewing in respondents' preferred language, Spanish or English. Sociodemographic data collected included city of residence (Chicago, San Francisco), country of birth (U.S.–born, foreign-born), sexual/gender identity (i.e., gay, bisexual, transgender), HIV serostatus, income, age, and education.

Internalized Homosexual Stigma

This 17-item variable has been validated in this population (with both self-identified gay/bisexual men and transgender women; Ramirez-Valles et al., 2010). Example items are: “Being gay means you will be alone when old” and “Gays are to blame for society's attitudes toward them.” The response categories were: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, and 4 = Strongly Agree. We calculated summary scores as averages of responses to the 17 items. Cronbach's alpha was .88.

HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs

This variable was developed based on Diaz and colleagues' work (Diaz, 2006; Diaz & Ayala, 2001) and on qualitative data collected in the development of this study (Ramirez-Valles, 2011). Our item bank included three items (see Table 2). Participants could choose from the following options: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, or 4 = Strongly Agree. We conducted an exploratory factor analysis and obtained a one-factor solution, with a Cronbach's alpha of .66. The items in this construct capture existing definitions of personal responsibility in the realm of HIV/AIDS—the condition is the result of people's own acts and values (Alonzo & Reynolds, 1995; Herek & Capitanio, 1999).

Table 2.

Exploratory Factor Analyses for HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs and Discriminatory Actions (n = 643)

| Items | Discriminatory Actions Towards PLWHA (SE) | HIV/AIDS- Personal Responsibility Beliefs (SE) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People with HIV/AIDS should be isolated from society. | 0.75 (.03) | — | 1.40 | 0.68 |

| People with HIV/AIDS should only date HIV+ people. | 0.85 (.03) | — | 1.64 | 0.81 |

| People with HIV/AIDS are not sexually desirable | 0.72 (.03) | — | 1.81 | 0.91 |

| People with HIV/AIDS are more sexually promiscuous. | — | 0.78 (.03) | 1.74 | 0.79 |

| AIDS exists because gays are promiscuous. | — | 0.73 (.03) | 1.68 | 0.85 |

| AIDS is a punishment from God. | — | 0.73 (.03) | 1.31 | 0.64 |

Discriminatory Actions Towards PLWHA

This variable was developed in a similar fashion as HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs. Our item bank included three items (see Table 2). Participants could choose from the following options: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, or 4 = Strongly Agree. Exploratory factor analysis revealed a one-factor solution, with a Cronbach's alpha of .70.

Analysis plan

Our sample exhibited a very low amount of missing data for the major study variables of interest (0–.5%). Given these findings, we used case deletion techniques, which are considered adequate ways to handle presumably ignorable low amounts of missing data (Schafer & Graham, 2002). First, we conducted analyses of variances (ANOVA) and Pearson's correlations to assess the relationship of sociodemographic variables to Discriminatory Actions toward PLWHA. Second, we conducted multivariate regression analyses, adjusting for sociodemographic covariates, to assess the relationship of HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs and Internalized Homosexual Stigma to Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA. Third, we assessed whether HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs partially mediated the relationship between Internalized Homosexual Stigma and Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA. To test the significance of the mediation effect, we used the Preacher and Hayes' method of calculating standard errors and 95% confidence intervals of the effect of Internalized Homosexual Stigma on Discriminatory Actions through HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs (Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This method uses 5,000 bootstrapped samples to estimate the bias-corrected and accelerated confidence interval and is preferred for small-sized samples. For comparison, we also used the traditional mediation Sobel's test to assess the full mediated pathway, which is a single test of the indirect effect that is treated similarly as a z-test (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Sobel, 1982).

Results

Relationships to Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA

Discriminatory Actions varied across several sociodemographic factors. First, there were significant differences by place of residence, F(1, 641) = 4.84, p = .03. Chicago participants reported greater Discriminatory Actions (M = 1.67, SD = 0.66) than San Francisco-based participants (M = 1.56, SD = 0.62). There were significant differences by place of birth, F(1, 641) = 19.27, p < .0001. U.S.–born participants reported greater Discriminatory Actions (M = 1.82, SD = 0.68) than foreign-born participants (M = 1.56, SD = .61). We found significant differences across sexual identity F(6, 639) = 6.06, p = .002. Bisexual men reported greater Discriminatory Actions (M = 1.79, SD = .65) than gay men (M = 1.57, SD = 0.62). We found no significant differences in Discriminatory Actions by HIV serostatus, F(1, 560) = 1.95, p = .16. Pearson's bivariate correlations revealed that Discriminatory Actions were not related to income, r(641) = -.02, p = .62, or age, r(641) = -.06, p = .18, or education, r(641) = -.07, p = .06.

After adjusting for covariates (i.e., city of residence, sexual/gender identity, birthplace, age, serostatus, and education), a multivariate linear regression revealed a significant amount of variation in Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA explained by HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs and Internalized Homosexual Stigma R2 change = 0.37, F-change(2, 632) = 201.97, p < .0001. Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA was significantly associated with both HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs (B = .54, t = 15.98, p < .0001) and Internalized Homosexual Stigma (B = .15, t = 4.43, p < .0001).

Mediation hypothesis

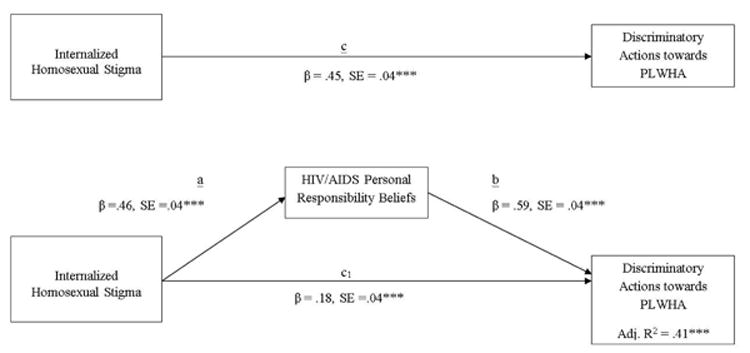

Using the Preacher and Hayes method (Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2008), we tested our mediation model, which exhibited adequate fit R2= .41, F(9, 630) = 51.17, p < .0001 (Figure 1). HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs partially mediated the relationship between Internalized Homosexual Stigma and Discriminatory Actions towards PLWHA, Mediated Effect = .28, SE = .04, 95% CI = .21, .35. Because the confidence interval did not contain zero, we can conclude that there is a significant partial mediation effect of Internalized Homosexual Stigma on Discriminatory Actions through Personal Responsibility Beliefs. This effect was supported through the traditional mediation methods (Sobel z = 9.63, p < .0001). Post-hoc separate analysis by HIV status showed slight differences. Among HIV-negative individuals (n = 391), partial mediation through Personal Responsibility Beliefs was found, as noted above (Mediated Effect = .30, SE = .05, 95% CI = .21, .41). Among HIV-positive individuals, (n = 170), full mediation was observed (Mediated Effect = .25, SE = .06, 95% CI = .14, .39). Confidence intervals for the mediated effect overlapped, suggesting modest variation in strength of associations across HIV status.

Figure 1.

Mediation Model of the Relationship Among Internalized Homosexual Stigma, HIV/AIDS Personal Responsibility Beliefs, and Discriminatory Actions Towards People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), Adjusting for Age, Education, Birthplace, Sexual/Gender Identity, and Serostatus Effects. All Coefficients Represent Unstandardized Regression Coefficients, n = 642. * * * p < .001.

Discussion

Because the number of PLWHA is increasing, especially in GBT communities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Prejean et al., 2011), understanding and addressing stigma towards PLWHA is of critical importance. The purpose of this study was to unpack Latino GBT persons' attitudes towards PLWHA. Following attribution theory, we proposed that internalized homosexual stigma influenced discriminatory actions towards PLWHA through HIV/AIDS personal responsibility beliefs. The results indicate that internalized homosexual stigma is associated to discriminatory actions and that personal responsibility beliefs partially mediate such relationship.

The unique contribution of this paper to research on stigma towards PLWHA is that it points to an empirical and theoretical link between homosexual stigma and stigma towards PLWHA in sexual minorities. This connection had not been tested among gay men (Connors & Hely, 2007a; Herek & Capitanio, 1999). This relationship has occurred because historically the HIV epidemic in the United States and Latin America has been largely driven by unprotected anal sex between men. Since the epidemic emerged, HIV and AIDS have been attached to homosexual behavior, which was further stigmatized at that point (Alonzo & Reynolds, 1995). PLWHA were judged by their homosexual behavior and perceived lack of responsibility. By the same token, the HIV/AIDS epidemic reinforced negative attitudes towards homosexuality (Herek & Capitanio, 1999; Ruel & Campbell, 2006). Although discriminatory actions towards PLWHA and beliefs about HIV/AIDS personal responsibility are not high in the sample we studied, it is significant that internalized homosexual stigma is associated to discriminatory actions and that it is through its relationship to personal responsibility beliefs. That is, Latino GBT people who have internalized societal negative views about homosexuality (e.g., feeling shame, not wanting to be gay) cognitively project those views onto PLWHA. They tend to believe that PLWHA are sexually promiscuous and that AIDS is a “punishment” and, hence, find PLWHA not sexually desirable and believe they need to be segregated from the rest. Personal responsibility beliefs may thus serve as the mechanism underlying the subtle and actual segregation made by HIV-negative individuals within GBT communities (Courtenay-Quirk et al., 2006).

The findings have important implications for research and interventions to reduce negative attitudes towards PLWHA. To further understand how discriminatory actions are formed, there is a need to assess at least one more element, familiarity with the condition and/or with homosexuality. We were not able to assess those variables in this study, but given the research evidence (Corrigan, Green, Lundin, Kubiak, & Penn, 2001; Herek & Glunt, 1993), it is possible that familiarity may be a factor in reducing both negative attitudes towards homosexuality and HIV/AIDS personal beliefs, hence decreasing discriminatory actions. This effect should be smaller in GBT populations than in the larger population.

Regarding strategies to lessen negative attitudes towards PLHWA, it is clear that the current dominant HIV prevention strategy of personal responsibility (e.g., use a condom, get tested) might, paradoxically, cultivate negative attitudes towards PLWHA. We might need to change this message or balance it with one about collective responsibility and empathy. Also, interventions may be focused on attitudes towards homosexuality. It might be very difficult to attempt to reduce negative attitudes towards PLWHA without addressing homosexual stigma in both general and sexual minority populations. Homosexual stigma in the general population needs to be addressed so that gay men are not exposed to it and hence do not internalize it. Among gay men, efforts may be directed at reducing internalized homosexual stigma, which may also address their overall mental health.

Limitations

The findings from this study need to be interpreted in light of several shortcomings. The most important limitation is the cross-sectional study design. A longitudinal or randomized control trial design may be needed to test the causal connection between internalized homosexual stigma and HIV/AIDS stigma. Yet, the continuing change in societal attitudes makes this challenging. Perhaps a long-term analysis of societal (and sub-group) trends in attitudes may be more feasible and effective than a randomized control or longitudinal analysis. For example, annual cross-sectional samples (e.g., overall population) may assess both attitudes towards homosexuality and towards PLWHA and examine whether the current trend of increasing positive attitudes towards homosexuality translates into similar movement in attitudes towards PLHWA.

Another limitation is our assessment of discriminatory actions towards PLWHA. The measurement does not reflect individuals' actual behaviors, but plausible actions. Yet, it is consistent with existing literature (Corrigan et al., 2003). True discriminatory actions are difficult to observe and record and not free of measurement error. Additionally, our instrument of personal responsibility beliefs had poor internal reliability. Future research may increase reliability by adding items describing personal responsibility of PLWHA. Last, this sample does not represent the “ Latino”GBT population in the United States. However, it was not the aim of this study to draw generalizations about such population's attitudes, but rather to test a theoretical model about the manner in which attitudes towards PLWHA are shaped.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01MH62937-01) to the first author and in part by a Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research through the National Cancer Institute (P50CA148143) to the second author.

Contributor Information

Jesus Ramirez-Valles, Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, at the University of Illinois–Chicago.

Yamile Molina, Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, at the University of Illinois–Chicago; Cancer Prevention Program at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

Jessica Dirkes, Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, at the University of Illinois–Chicago.

References

- Alonzo AA, Reynolds NR. Stigma, HIV, and AIDS: An exploration and elaboration of the illness trajectory surrounding HIV infection and AIDS. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41:303–315. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botnick MR. Part 1: HIV as “the line in the sand”. Journal of Homosexuality. 2000a;38(4):39–76. doi: 10.1300/J082v38n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botnick MR. Part 3: A community divided. Journal of Homosexuality. 2000b;38(4):103–132. doi: 10.1300/J082v38n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA, Etzel MA, Hinojos E, Henry CL, Perez M. Preventing HIV among Latino and African American gay and bisexual men in a context of HIV-related stigma, discrimination, and homophobia: Perspectives of providers. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19(11):737–744. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Fact sheet: HIV among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/msm/

- Connors J, Hely A. Attitudes toward people living with HIV/AIDS: A model of attitudes to illness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2007a;37(1):124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2007.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors J, Hely A. Attitudes toward people living with HIV/AIDS: A model of attitudes to illness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2007b;37(1):124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2007.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Green A, Lundin R, Kubiak MA, Penn DL. Familiarity with and social distance from people who have serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(7):953–958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson A, Rowan D, Kubiak MA. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2003;44:162–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay-Quirk C, Wolitski RJ, Parsons JT, Gomez CA. Is HIV/AIDS stigma dividing the gay community? Perceptions of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(1):56–67. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Galea S, Tracy M, Tross S, Vlahov D. Stigmatization of newly emerging infectious diseases: AIDS and SARS. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(3):561–567. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM. In our own backyard: HIV/AIDS stigmatization in the Latino gay community. In: Teunis N, Herdt G, editors. Sexual inequalities and social justice(pp 50-65) Berkeley: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G. Social discrimination and health: The case of Latino gay men and HIV risk. Washington, DC: Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Binns HJ, Garofalo R. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(5):371–376. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rivera M, Bauermeister JA. Children's attitudes toward people with AIDS in Puerto Rico: Exploring stigma through drawings and stories. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(2):250–263. doi: 10.1177/1049732306297758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Banerjee SC. Disease-related stigma: Comparing predictors of AIDS and cancer stigma. Journal of Homosexuality. 2006;50(4):185–209. doi: 10.1300/J082v50n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems. 2002;49(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: Theory and practice. Journal of Social Issues. 2007;63(4):905–925. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Thinking about AIDS and stigma: A psychologist's perspective. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2002;30:594–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP. AIDS stigma and sexual prejudice. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42:1130–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP. A second decade of stigma: Public reactions to AIDS in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:574–577. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.4.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: Prevalence and trends, 1991-1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(3):371–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. Stigma, social risk, and health policy: Public attitudes toward HIV surveillance policies and the social construction of illness. Health Psychology. 2003;22(5):533–540. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Chopp R, Strohl D. Sexual stigma: Putting sexual minority health issues in context. In: Meyer I, Northridge M, editors. The health of sexual minorities. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 171–208. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Glunt EK. Interpersonal contact and heterosexuals' attitudes toward gay men: Results from a national survey. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30(3):239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Holtgrave DR, McGuire JF, Milan J. The magnitude of key HIV prevention challenges in the United States: Implications for a new national HIV prevention plan. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1163–1167. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LM, Mullick R, Mulford CL. General versus specific victim blaming. Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;142(2):249–263. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser public opinion spotlight: Attitudes about stigma and discrimination related to HIV/AIDS. 2006 http://www.kff.org/spotlight/hivstigma/upload/Spotlight_Aug06_Stigma-pdf.pdf.

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: The internalized AIDS-related stigma scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):87–93. doi: 10.1080/09540120802032627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6(4):309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27(1):363–385. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak WWS, Cheung RYM, Law R, Woo J, Li PCK, Chung RWY. Examining attribution model of self-stigma on social support and psychological well-being among people with HIV+/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(1):1549–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture, and empowerment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14(3):186–192. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Martin TA, Oryol VE, Senin IG, O'Cleirigh C. Personality correlates of HIV stigmatization in Russia and the United States. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(1):190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Molina Y, Ramirez-Valles J. HIV/AIDS stigma: Measurement and relationships to health in Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender individuals. AIDS Care 2012 [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Stigma and global health research program: Request for application(RFA) 2002 http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-TW-03-001.html.

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Assessing mediation in communication research. In: Hayes A, Slater M, Snyder L, editors. The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J. Compañeros: Latino activists in the face of AIDS. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Brown AU. Latino's community involvement in HIV/AIDS: Organizational and individual perspectives on volunteering. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15(1, Suppl. A):90–104. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.90.23606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Garcia D, Campbell RT, Diaz RM, Heckathorn DD. HIV infection, sexual risk behavior, and substance use among Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender persons. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1036–1042. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Kuhns LM, Campbell RT, Diaz RM. Social integration and health: Community involvement, stigmatized identities, and sexual risk in Latino sexual minorities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(1):30–47. doi: 10.1177/0022146509361176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Pryor JB, Gaddist BW, Mayer R. Stigma, secrecy, and discrimination: Ethnic/racial differences in the concerns of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(2):265–271. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel E, Campbell RT. Homophobia and HIV/AIDS: Attitude change in the face of an epidemic. Social Forces. 2006;84(4):2167–2178. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit PJ, Brady M, Carter M, Fernandes R, Lamore L, Meulbroek M, et al. HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: A literature review. AIDS Care. 2011;24(4):405–412. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.613910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Social Research Sciences Solutions. LGBT acceptance and support: The Hispanic perspective. Media, PA: 2012. Author. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Kashubeck-West S, Meyer J. Internalized heterosexism: Measurement, psychosocial correlates, and research directions. Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36(4):50. [Google Scholar]

- Torian L, Chen M, Rhodes P, Hall I. HIV surveillance-United States, 1981-2008. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60:689–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Collani G, Grumm M, Streicher K. An investigation of the determinants of stigmatization and prejudice toward people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2010;40(7):1747–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. Attribution theory: An organizational perspective. Delray Beach, FL: St. Lucie Press; 1995. Attribution theory in organizational behavior: A relationship of mutual benefit. In Mark J. Martinko (Ed.) pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]