Abstract

Background

The Internet is a promising medium for engaging the community in preventive care and health promotion, particularly among those who do not routinely access health care.

Objective

The authors pilot-tested a novel website that translates evidence-based preventive health guidelines into a patient health education tool. The web-based tool allows individuals to enter their health risk factors and receive a tailored checklist of recommended preventive health services based on up-to-date guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

Methods

The authors conducted surveys and in-depth interviews among a purposive sample of adults from an urban African American community who pilot-tested the website in a standardized setting. Interviews were designed to assess the usability, navigability, and content of the website and capture patient perceptions about its educational value and usefulness. Each interview was audiotaped, transcribed, and examined using the constant comparative method.

Results

Twenty-five participants piloted the tool: 96% found it easy to use and 64% reported learning something new. Many participants reported that, in addition to improving clinical preventive care (the intended purpose), the website could serve as a stand-alone tool to improve self-awareness and motivate behavior change.

Conclusions

A web-based tool designed to translate preventive health guidelines for the community may serve the dual purpose of improving the delivery of preventive health care and encouraging health promotion. The website developed here is publicly available for use by practitioners and the community.

Keywords: web-based learning, preventive health, evidence based medicine, doctor-patient relationship

The benefits of preventive health care are well established, yet studies demonstrate that Americans are not consistently obtaining recommended preventive care measures.1,2 Rates of delivery are even lower in racial and ethnic minorities, who experience reduced access to health care and lower quality of preventive care.3

Sixty-six percent of American adults, including nearly half of African Americans and Latinos, use the Internet to access health information.4 The web has also become an important source of information about preventive health.5 Thus, the Internet may represent a promising medium for engaging diverse communities in preventive care and health promotion.

Systematic reviews demonstrate that patient-directed initiatives increase community demand for clinical preventive service delivery.6 Studies of patient-held checklists have demonstrated provider acceptance and effectiveness in increasing compliance with preventive health care guidelines.7,8. However, paper-based tools face several challenges: they are difficult to update, costly to disseminate, and nearly impossible to tailor.

In this case report, we describe a novel web-based patient education tool that is readily updated, is freely available on the World Wide Web, and provides users a tailored checklist of recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

Methods

Setting and Participants

After the study received approval from the Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited from an urban, working class African-American community. Flyers were posted in an academic medical center and various community locations (eg, churches, community centers). Eligible participants included adults who were 18 years and older, who had experience with computer and Internet use, and who rated their health as better than “poor.” Participants received a $20 gift card as an incentive.

Tool Development

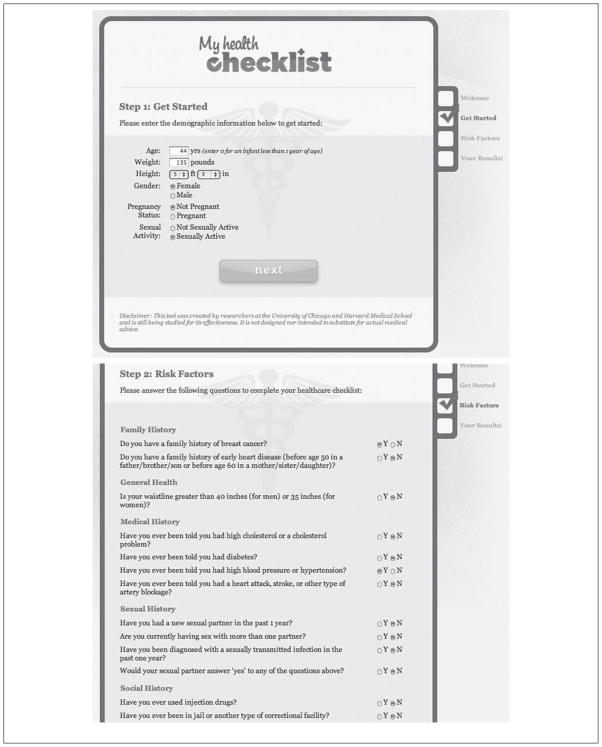

The web-based tool allows individuals to create a checklist of preventive health services based on self-identified risk factors (Figure 1, available at www.myhealthchecklist.org). Using an updatable database, the tool links risk profiles with guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Users enter information about their age, sex, height/weight, sexual activity, and pregnancy status. After cross-referencing specific recommendations, the tool generates additional questions about risk factors and comorbid conditions that allow it to further individualize recommendations. For example, if the individual is age 26 or older and sexually active, it will assess for risk factors for Chlamydia to determine if screening should be recommended. Finally, it creates a tailored checklist of recommended preventive health services, divided into counseling, prevention, and screening. Users can access educational materials about each recommended service and print the checklist out for use with their physician (eg, discussing mammograms) or at home (eg, reducing alcohol consumption). The website was written at a sixth-grade reading level to facilitate use by a wide audience.

Figure 1.

Screenshots of the demographics page, the risk factor page, and a sample personalized checklist.

Study Design

Based on mixed methods, in-depth individual interviews and surveys were conducted at a research office for approximately 1 hour. After receiving as much time as necessary to use the website, participants were interviewed with open-ended questions adapted from a prior study9 to assess their perceptions of the tool’s educational value and usefulness and to obtain feedback on its navigability, usability, and content. Interviews were performed by a member of the research team (K.B., I.N., M.S.). Discussions were audiotaped and then transcribed for analysis. In addition, pre- and postsurveys were conducted to assess demographic data, computer and Internet usage, and satisfaction with the tool.

Data Analysis

De-identified, anonymous transcripts were reviewed by 3 investigators (S.N., I.N., M.S.) and analyzed with no a priori hypotheses. The reviewers independently applied themes iteratively until consensus was achieved.

Results

A total of 25 participants completed the study, and all but one self-identified as African American. Twenty-four percent had a high school degree equivalent or less. Nearly one-quarter had Medicaid, and 16% were uninsured. The majority did not require assistance using the Internet (84%), and most had used the Internet to obtain medical information before (72%).

All the participants successfully used the website to create a personalized preventive health checklist without assistance from the research staff. Most found the website helpful to understanding their preventive health needs (92%) and reported learning something new (64%). The majority (84%) felt very comfortable using the website to obtain personalized health information.

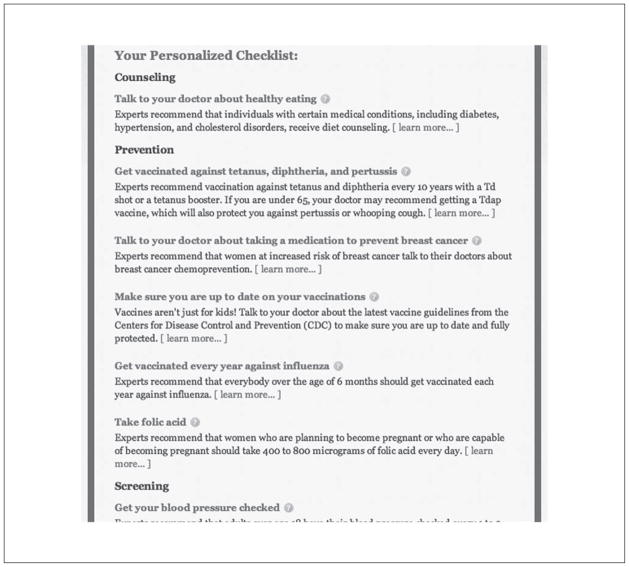

A number of themes emerged (Figure 2). Participants reported that the checklist introduced them to preventive health recommendations they were previously unaware of (eg, tetanus booster) as well as measures they were aware of but did not realize applied to them (eg, chlamydia screening). All participants indicated a willingness to take a printout of the checklist to the doctor. As one participant noted,

I would want to print it out just to let the doctor know that I am serious about this and I’ve taken time to research and I’m having these problems. … From my experience the more information that you give the doctor, the more they can help you.

Figure 2.

Selected commentary from in-depth interviews with participants.

Most participants felt that the tool was primarily for personal health education and empowerment. In the words of one participant,

I think that it’s a great avenue for me to help me be more involved, I guess go to each step and look at to see what I need to do and maybe things I need to check into and follow it.

Participants reported that the tool helped them understand their health risk factors. For example, some participants were surprised to learn that their body mass index qualified them as obese. Others felt that it would encourage them to take a more active role in maintaining their health. Upon learning about the term alcohol misuse, one participant said that he needed to cut down on his alcohol consumption.

Discussion

In this study, evidence-based guidelines for clinical preventive services were successfully translated into a web-based patient education tool and pilot-tested in an urban African American community.

The tool was designed to improve preventive care by first, raising awareness of clinical preventive health services and, second, encouraging individuals to request those services from their physicians. As anticipated, participants learned about preventive care that they were unaware of or did not realize was recommended for them, and they were willing to share their individualized checklists with their primary care physicians.

A surprising finding was that participants reported that the tool helped them understand their health risks and encouraged them to take greater ownership over their health. In addition to using the tool with their providers to improve clinical care, they saw the website as a stand-alone tool for health promotion.

This web-based tool is more tailored than currently available public tools, such as one put forth by the US Department of Health and Human Services (www.healthfinder.gov), which takes into account only an individual’s age, sex, and pregnancy status. Our site has been considerably revised on the basis of systematic feedback from participants in this study and is freely available via the World Wide Web for diverse communities and practitioners.

Limitations

The study population was a working-class urban African American population; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. In addition, certain populations that may be important to target were excluded, including individuals with self-identified poor health and little or no computer or Internet experience.

Conclusions

We believe that we have developed an innovative web-based tool that captures the most up-to-date preventive health recommendations and translates them into a personalized patient education tool. This preliminary study suggests that the website may serve as a novel tool for engaging the community in preventive care and health promotion.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the University of Chicago Clinical and Translational Science Award, which funds short-term studies for postdoctoral students, residents, and fellows (UL1 RR024999). We also recognize Keisha Bishop, BSHA for her contributions to this study.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Nundy is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Services Research Training Program (T32 HS00084). Dr Peek is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development program and the Mentored Patient-Oriented Career Development Award of the NIDDK (K23 DK075006). This research was also supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60 DK20595) and the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK092949).

Biographies

Shantanu Nundy, MD is a clinical instructor and general medicine fellow at the University of Chicago Medical Center. His research interests include the use of Internet and mobile technologies to improve prevention and chronic disease care and reduce health disparities.

Mosmi Surati, MD, MPH was a medical student at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. She is currently a resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan.

Ifeoma Nwadei, MD was a medical student at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. She is currently a categorical General Surgery resident at Emory University Hospital.

Gaurav Singal, MD is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. He has over a decade of experience in computational research and web development and currently works on clinical informatics and natural language processing applications in healthcare.

Monica E. Peek, MD, MPH is an assistant professor at The University of Chicago, where she is a practicing general internist and health services researcher. Her research focuses on health disparities and patient empowerment interventions among racial/ethnic minorities. Dr. Peek is also an associate director of the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research.

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Kottke TE, Solberg LI, Brekke ML, Cabrera A, Marquez MA. Delivery rates for preventive services in 44 Midwestern clinics. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1997;72:515–523. doi: 10.4065/72.6.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA, Kelly RB, Zyzanski SJ. Direct observation of rates of preventive service delivery in community family practice. Prev Med. 2000;31:167–76. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halle M, Lewis CB, Seshamani M. [Accessed January 9, 2012];Health disparities: A case for closing the gap. http://www.healthreform.gov/reports/healthdisparities/disparities_final.pdf.

- 4.Pew Internet & American Life Project. [Accessed November 28, 2011];The social life of health information. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Life-of-Health-Info.aspx.

- 5.Quintana Y, Feightner JW, Wathen CN, Sangster LM, Marshall JN. Preventive health information on the Internet: qualitative study of consumers’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:1759–1765. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron RC, Rimer BK, Breslow RA, et al. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Client-directed interventions to increase community demand for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1 suppl):S34–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickey LL, Petitti D. A patient-held minirecord to promote adult preventive care. J Fam Pract. 1992;34(4):457–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich AJ, Duhamel M. Improving geriatric preventive through a patient-held checklist. Fam Med. 1989;21(3):195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fetters MD, Ivankova NV, Ruffin MT, Creswell JW, Power D. Developing a web site in primary care. Fam Med. 2004;36:651–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]