Abstract

The paired motor unit analysis provides in vivo estimates of the magnitude of persistent inward currents (PIC) in human motoneurons by quantifying changes in the firing rate (ΔF) of an earlier recruited (reference) motor unit at the time of recruitment and derecruitment of a later recruited (test) motor unit. This study assessed the variability of ΔF estimates, and quantified the dependence of ΔF on the discharge characteristics of the motor units selected for analysis. ΔF was calculated for 158 pairs of motor units recorded from nine healthy individuals during repeated submaximal contractions of the tibialis anterior muscle. The mean (SD) ΔF was 3.7 (2.5) pps (range −4.2 to 8.9 pps). The median absolute difference in ΔF for the same motor unit pair across trials was 1.8 pps, and the minimal detectable change in ΔF required to exceed measurement error was 4.8 pps. ΔF was positively related to the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit (r2=0.335; P<0.001), and inversely related to the rate of increase in discharge rate (r2=0.125; P<0.001). A quadratic function provided the best fit for relations between ΔF and the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units (r2=0.229, P<0.001), the duration of test motor unit activity (r2=0.110, P<0.001), and the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit (r2=0.237, P<0.001). Physiological and methodological contributions to the variability in ΔF estimates of PIC magnitude are discussed, and selection criteria to reduce these sources of variability are suggested for the paired motor unit analysis.

Keywords: Persistent inward current, Delta F, electromyography, motoneuron, intrinsic properties

1. Introduction

It is well established that the dendrites of spinal motor neurons possess voltage-sensitive channels that exert a strong influence on the processing of synaptic inputs (see Heckman et al., 2008 for review). Activation of these channels causes a persistent inward current (PIC), comprised of both a slow activating L-type Ca2+ current and a fast activating persistent Na+ current, that can amplify and prolong synaptic inputs to the cell. The voltage-sensitive channels responsible for generating a PIC are typically activated near the threshold for cell spiking (i.e., recruitment) (Bennett et al., 1998b), and are known to be under strong neuromodulatory control (Conway et al., 1988; Hounsgaard et al., 1988; Lee & Heckman, 1999). It has been proposed that PICs facilitate state-dependent modulation of motor neuron excitability during the execution of normal motor behaviors, and may be impaired in a variety of pathological conditions that affect the motor system (reviewed in Heckman et al., 2008a–b).

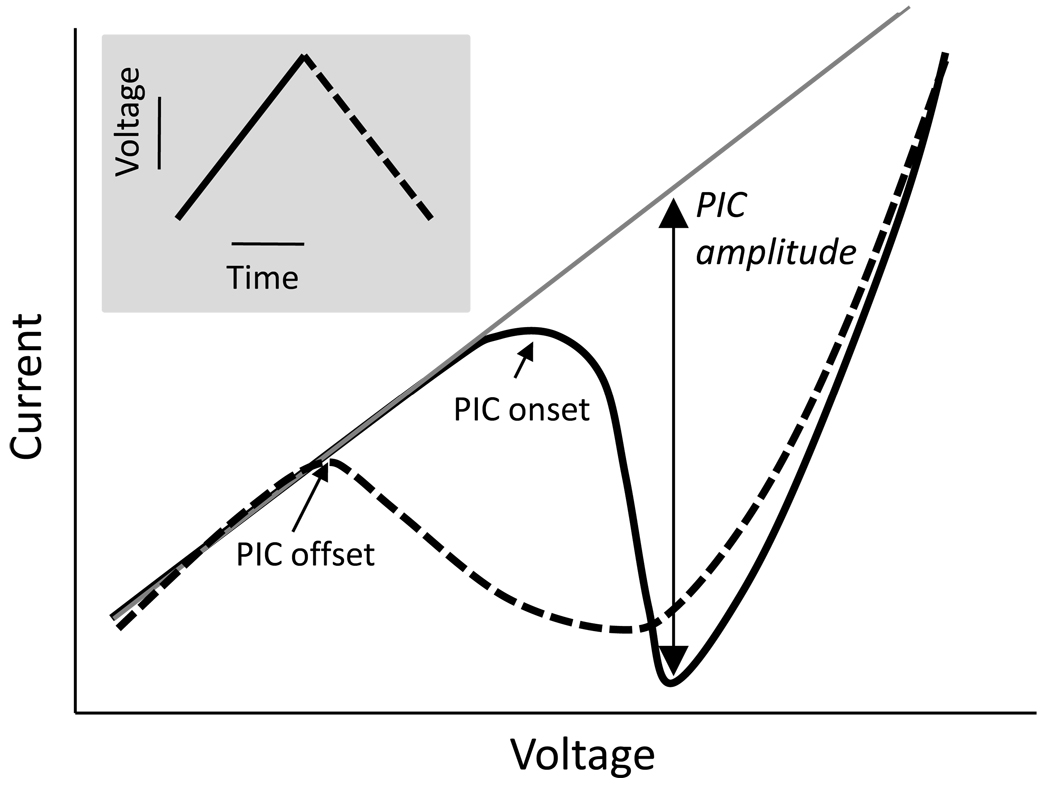

In reduced preparations, PIC activation can be detected as a downward deflection in net current during a linear rise in the voltage command. The magnitude of the PIC is then quantified by the amplitude of the negative deflection in the current-voltage function as illustrated in Figure 1. In contrast to the widely studied presence of PICs in cellular studies, the presence and function of PICs in human motor neurons have been difficult to assess. Several studies in humans have identified patterns of motor unit discharge (Kiehn & Eken, 1992, 1997; Gorassini et al., 1998; Walton et al., 2002; Kamen et al., 2006) and muscle force generation (Collins et al., 2001, 2002; Hornby et al., 2003; Baldwin et al., 2006; Blouin et al., 2009) that are consistent with behaviors attributed to PICs in cellular studies. However, the experimental techniques used in these studies are limited by their inability to detect quantitative changes in the magnitude of PICs across different motor behaviors or study populations.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the procedure used to quantify PIC amplitude from intracellular recordings (adapted from Heckman et al., 2008, Figure 2). The solid line indicates net current plotted as a function of voltage rise during the ascending limb of a triangular voltage ramp (inset), whereas the dashed line indicates net current during the descending limb of the voltage ramp. The onset of the PIC manifests as a downward deflection in the net current (solid line). The magnitude of the PIC is calculated as the difference between the linear leak current-voltage function (solid gray line) and the peak of the downward deflection in net current during voltage rise. The sustained inward current on the descending limb of the voltage ramp and hysteresis in the activation (onset) and deactivation (offset) of the PIC are reflected by higher firing frequencies for a given level of synaptic input while the PIC is activated.

An indirect technique for estimating the magnitude of PICs in human motor neurons has been proposed by Gorassini and colleagues (Bennett et al., 2001a; Gorassini et al., 2002). A characteristic feature of PICs in cellular studies is that the activation of these currents at or near the threshold for recruitment allows motor neurons to sustain their firing at lower levels of excitatory input than were required to initiate firing (Conway et al., 1988; Hounsgaard et al., 1988; Lee & Heckman, 1998b). If it is assumed that the discharge rate of an earlier recruited (reference) motor unit provides a sensitive indicator of changes in the net excitatory synaptic input to the motor neuron pool, then the magnitude of the PIC present in a later recruited (test) motor unit can be quantified by the change in the firing rate (ΔF) of the reference motor unit at the time of recruitment and derecruitment of the test motor unit (Gorassini et al., 2002). Any reduction in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit is thought to reflect a lower level of net excitatory synaptic input to the test motor unit at the time of derecruitment. The additional depolarization required to maintain firing of the test motor unit as the net excitatory synaptic input drops below the level required for recruitment is assumed to come from activation of a PIC in the motor neuron.

The growing characterization of PICs at the cellular level (Prather et al., 2001; Hyngstrom et al., 2008) and the potential role of these currents in pathological motor behaviors (Bennett et al., 2001a; Gorassini et al., 2004; Li et al., 2004) emphasize the importance of studying the functional role of PICs in humans. The paired motor unit analysis provides a quantitative, in vivo estimate of PIC magnitude and is therefore a potentially valuable tool for the study of humans. Although ΔF has been validated as an accurate estimate of PIC magnitude in chronic spinal rats (Bennett et al., 2001a), the validity of ΔF as an exclusive measure of PIC magnitude in human motor neurons has been questioned (Fuglevand et al., 2006; Powers et al., 2008; Fuglevand & Revill, 2009). Furthermore, a recent study of this technique in a decerebrate cat preparation indicated that ΔF estimates can be highly variable and depend on the discharge characteristics of the reference and test motor units selected for analysis (Powers et al., 2008).

Despite evidence that ΔF estimates can be highly variable in the decerbrate cat, the variability of ΔF in humans is unknown and no explicitly defined selection criteria currently exist to optimize the reliability of the paired motor unit analysis. The purposes of this study were to assess the within- and between-trial variability of ΔF estimates of PIC magnitude in the human tibialis anterior muscle, and to quantify the dependence of ΔF on selected discharge characteristics of the reference and test motor units used to calculate this measure. Based on previously published results from animal and modeling studies, we hypothesized that ΔF would be (1) positively related to the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit (Powers et al., 2008); (2) inversely related to the rate of increase in discharge rate of the reference motor unit (Fuglevand & Revill, 2009; Revill & Fuglevand, 2009); (3) positively related to the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units at brief recruitment intervals (Bennett et al., 2001b; Udina et al., 2010); (4) positively related to the duration of activity in the test motor unit (Bennett et al., 2001b; Udina et al., 2010); and (5) positively related to the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit (Powers et al., 2008).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Participants

Nine healthy individuals (6 women; 3 men) ranging in age from 24 to 47 years (mean (SD) = 31.8 (8.6) years) volunteered to participate in the study. All participants reported having no known neurological or orthopedic impairments, and all provided informed consent prior to participation in experimental procedures approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Experimental setup

Participants were seated upright with the forearms resting on arm rests and the hip joint flexed to approximately 90 degrees. The left foot was supported on a foot rest, and the right leg was secured to a custom made device with the knee flexed to approximately 45 degrees and the ankle positioned in approximately 20 degrees of plantar flexion. Straps attached to a footplate were placed securely around the forefoot and ankle. Isometric dorsiflexion contractions exerted tensile forces on a force transducer (LGP 310; 2224 N range; Cooper Instruments, Warrenton, VA) attached to the footplate under the forefoot. Dorsiflexion force was displayed in real time on a feedback monitor positioned at eye level approximately 1 m in front of the participant.

2.3 Experimental Protocol

Participants performed maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVCs) of the ankle dorsiflexor muscles, and were instructed to gradually increase the exerted force from zero to maximum during a period of 3 s and then maintain maximal force for 2–3 s while receiving strong verbal encouragement. Multiple MVC trials were performed, each separated by at least 60 s rest, until peak forces from two trials agreed within 5%; the highest of these trials was considered the MVC force. After several minutes rest, participants performed a series of submaximal dorsiflexion test contractions whereby they were required to match their ankle dorsiflexion force to a template displayed on the feedback monitor. The target template comprised three phases: a ramped increase in isometric force; a plateau region in which isometric force was held constant; and a ramped decrease in isometric force. The rates of change in force were equivalent during the ascending and descending force ramps within a given contraction. To ensure sampling of a wide range of motor unit discharge behaviors for ΔF calculations, the features of the test contractions listed in Table 1 were systematically varied by changing the dimensions of the target force template across different trials within the same recording session. Specific dimensions of the template were determined individually for each subject to optimize recordings from identified motor units, and some templates were used repeatedly within a session to assess the between-trial variability of ΔF. Rest periods of at least 30 s were provided between consecutive test contractions, and every 5–10 minutes a longer break of several minutes was provided to prevent muscle fatigue. The total duration of the experiment was less than 2 hours for each participant.

Table 1.

Characteristics of test contractions (N=119)

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Contraction duration(s) | 18.7 (7.8) | 4.2–40.9 |

| Plateau duration (s) | 1.1 (2.4) | 0.0–11.8 |

| Force peak (%MVC) | 12.7 (5.8) | 4.4–37.6 |

| Force rate of rise (%MVC/s) | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.5–5.0 |

| Force rate of fall (%MVC/s) | 1.6 (0.8) | 0.5–5.1 |

2.4 Data acquisition

The force signal was A/D converted and stored at 100 samples per second (Power 1401, 16-bit resolution; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Single motor unit activity was recorded from the muscle belly of the right tibialis anterior muscle using a single bipolar intramuscular electrode consisting of two Formvar-insulated stainless steel wires (50 µm in diameter; California Fine Wire Co., Grover Beach, CA) with the cross-sectional area exposed for recording. A 30-gauge needle was used to insert the wires into the tibialis anterior muscle after the MVC trials were completed. The needle was removed after placement of the intramuscular wires, and the signals were examined online to verify the detection of motor unit action potentials. If necessary, small adjustments were made in the placement of the wires to enhance signal quality. Intramuscular EMG signals were amplified (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA; X 1000) and band-pass filtered (20–8000 Hz) before A/D conversion and storage at 20000 samples per second.

2.5 Data analysis

All offline analyses were performed with custom software written in Matlab (v7.5.0.342; MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA). Maximal dorsiflexion force was calculated as largest peak force achieved during the MVC trial. Submaximal test contractions were considered for analysis if the dorsiflexion force profile was free from abrupt changes in force level, and if more than one motor unit could be discriminated during the contraction. Test contraction forces were normalized to the MVC force.

Single motor unit action potentials were discriminated from the intramuscular EMG signal using the spike-sorting algorithm in Spike2 software (v5.14; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Motor unit action potentials were automatically identified based on waveform shape and were manually verified on a spike-by-spike basis to increase discrimination accuracy. For each pair of discriminated motor units, the earliest recruited motor unit was classified as the reference motor unit, whereas the later recruited motor unit was classified as the test motor unit. If more than two motor units could be discriminated during a test contraction, then all possible pairs were considered. Thus, the same motor unit could serve as the reference motor unit for one pair, and the test motor unit for another pair. A motor unit pair was only considered for analysis if the test motor unit was derecruited before the reference motor unit.

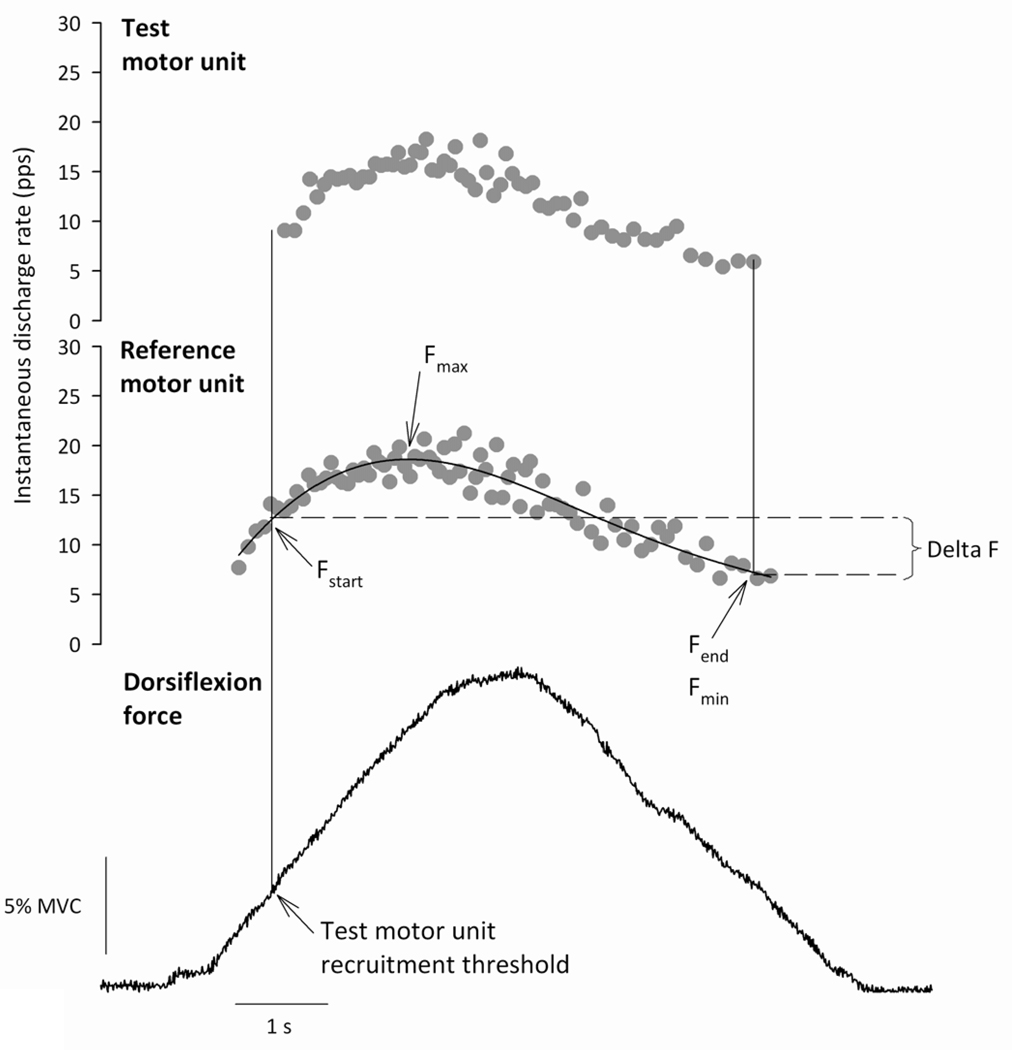

The instantaneous discharge rate of each discriminated motor unit was calculated as the reciprocal of the interval between each motor unit action potential and the motor unit action potential preceding it, expressed in pulses per second (pps). The discharge rate of the reference motor unit was smoothed with a fifth-order polynomial. This polynomial fit was used to calculate the discharge rate of the reference motor unit at the time of test motor unit recruitment (Fstart) and derecruitment (Fend), as well as the maximal (Fmax) and minimal (Fmin) discharge rate of the reference motor unit while the test motor unit was active, as illustrated in Figure 2. ΔF was quantified as the difference between Fstart and Fend, as previously described by Gorassini and colleagues (2002). Relations between ΔF and the following motor unit discharge characteristics were assessed: discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit while the test motor unit was active; rate of increase in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit; time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units; duration of test motor unit activity; and recruitment threshold of the test motor unit.

Figure 2.

Example data from one subject showing dorsiflexion force (bottom panel) and the instantaneous discharge rate profiles of two concurrently active motor units expressed in pulses per second (pps). The first recruited motor unit was classified as the reference motor unit (middle panel), and the second recruited motor unit as the test motor unit (top panel). The discharge rate of the reference motor unit was smoothed with a fifth-order polynomial (solid line; middle panel). This polynomial fit was used to calculate the discharge rate of the reference motor unit at the time of test motor unit recruitment (Fstart) and derecruitment (Fend), and the maximal (Fmax) and minimal (Fmin) discharge rate of the reference motor unit while the test motor unit was active. The magnitude of the persistent inward current present in the test motor unit (ΔF) was estimated as Fstart − Fend.

Calculation of ΔF relies directly on the modulation of discharge rate in the reference motor unit. Accordingly, Powers et al (2008) reported that ΔF is influenced by the amount of discharge rate modulation that occurs in the reference motor unit while the test motor unit is active during reflexive contractions in the decerebrate cat. To examine this relation in human motor neurons, the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit was quantified as the difference between Fmax and Fmin, as previously described by Powers and colleagues (2008).

It has been recommended that changes in synaptic input during the assessment of ΔF must be slowly graded and of low-amplitude to avoid the confounding influence of spike frequency adaptation and rate-dependent dynamics (Bennett et al., 2001a), however, practical limits for these parameters when evaluating ΔF in human motor neurons have not been established. To assess the influence of the rate of change in synaptic input on ΔF in the present study, the rate of increase in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit was quantified as [Fmax − Fstart] / [Time of Fmax − Time of Fstart].

The paired motor unit analysis assumes that any PIC in the reference motor unit is fully activated before the test motor unit is recruited. Full activation of the PIC is slow (Bennett et al., 2001b) and may take up to 2 s in human motor neurons (Udina et al., 2010). Therefore, it is plausible that ΔF may be related to the time allowed between recruitment of the reference and test motor units, particularly at short recruitment intervals. Recruitment of a motor unit was identified as the time at which regular discharge (defined as successive discharges within 600 ms) of motor unit action potentials began, and the time from recruitment of the reference motor unit to recruitment of the test motor unit was quantified for each motor unit pair. Similarly, the duration of activity in the test motor unit must be sufficient to allow the PIC to fully develop to prevent underestimation of the PIC magnitude. The duration of test motor unit activity was quantified as the time from recruitment to derecruitment of the test motor unit for each pair. Finally, there is evidence that ΔF may depend on the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit (Powers et al., 2008). Recruitment threshold was quantified in the present study as the dorsiflexion force at the time of recruitment of the test motor unit.

As described in detail by Gorassini et al. (2002), the discharge rates of the reference and the test motor unit were averaged across consecutive 500 ms windows spanning the interval during which both motor units were active. Rate-rate correlation was calculated as the correlation (r) between the mean discharge rates of the two motor units within each window. Rate-rate correlation provides an index of common modulation of the discharge rates of two concurrently active motor units. Rate-rate correlation values less than r=0.7 (Gorassini et al., 2002; Gorassini et al., 2004; Mottram et al., 2009; Udina et al., 2010) or r2=0.5 (Powers et al., 2008) have been taken as evidence that synaptic input to the two motor units was not sufficiently similar to meet the assumption of shared synaptic input, as required by the paired motor unit analysis. Therefore, all motor unit pairs with a rate-rate correlation less than r=0.7 were excluded from analysis.

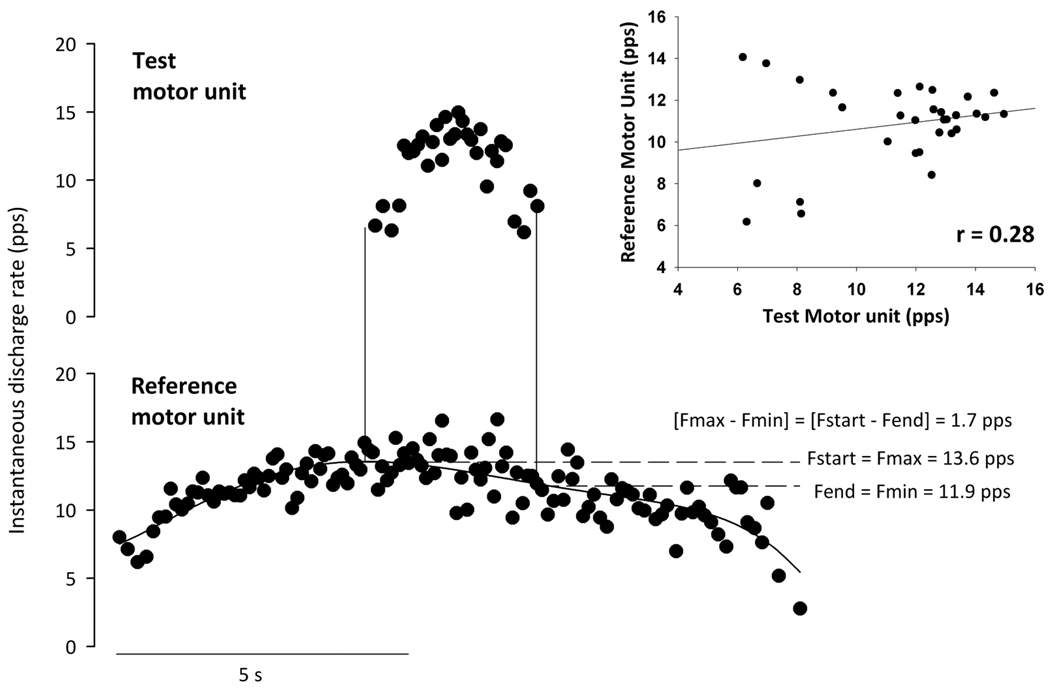

Another assumption of the paired motor unit analysis is that the discharge rate of the reference motor unit is a sensitive indicator of the net excitatory synaptic input that it receives. The validity of this assumption is of paramount importance at the two time points when synaptic input is estimated; i.e. at recruitment and derecruitment of the test motor unit. Saturation of discharge rates in the reference motor unit while synaptic input is still increasing violates this assumption, and it is therefore important to ensure that saturation has not occurred at the time of test motor unit recruitment. To achieve this, we excluded all motor unit pairs in which the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit (Fmax − Fmin) was within 0.5 pps of ΔF (Fstart − Fend). Fmin is generally equivalent to Fend, therefore equivalence between the discharge rate modulation and ΔF indicates that Fmax is equivalent to FStart, i.e. the discharge rate of the reference motor unit did not continue to increase with further increases in force after the test motor unit was recruited. Data from a typical motor unit pair exhibiting this behavior is shown in Figure 3. Values of discharge rate modulation that were within 0.5 pps of ΔF could be attributed either to saturation of the discharge rate in the reference motor unit, or to recruitment of the test motor unit near the peak of the force target such that small increases in synaptic input were not sufficient to drive the reference motor unit to higher firing rates before peak force was achieved.

Figure 3.

Example data from one subject showing a motor unit pair that was excluded due to low rate-rate correlation (r = 0.28) and potential saturation of the discharge rate in the reference motor unit ([Fmax − Fmin] within 0.5 pps of ΔF). Note the plateau in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit as the test motor unit discharge rate increases during voluntary contraction.

2.6 Statistical analysis

To assess the dependence of ΔF on each of the selected motor unit discharge characteristics we fitted each relation with a linear and a quadratic model using PASW software (v18.0.0, Chicago, IL). An F test was used to determine whether the additional fitting parameter contained in the quadratic model provided a significant increase in the goodness of fit. The level of statistical significance was set at P=0.05.

When the same force templates were used repeatedly within a session, ΔF was assessed multiple times for the same motor unit pair. A histogram of the absolute difference between the smallest and largest ΔF estimate obtained for each motor unit pair was constructed to assess the between-trial variability of ΔF. These data were used to calculate the smallest change in ΔF that could confidently be considered to exceed measurement error at a 95% confidence level according to the following formula (Beaton, 2000):

Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) = 1.96· √2 · SD · √(1 – test-retest reliability coefficient) where the test-retest reliability coefficient was calculated as the correlation between the two most extreme ΔF estimates for each motor unit pair. This will give a conservatively low estimate of the test-retest reliability coefficient in contrast to selecting two ΔF measures for a motor unit pair that were not as variable.

When more than one reference motor unit was available to calculate ΔF for a given test motor unit within the same test contraction, ΔF was assessed multiple times for the same test motor unit. A histogram of the absolute difference between the smallest and largest ΔF estimate obtained for a given test motor unit was constructed to assess the within-trial variability of ΔF, dependent on the selection of the reference motor unit.

3. Results

In total, 334 discriminated motor unit pairs were considered for analysis. These motor units were discriminated from 176 test contractions in 9 participants, with an average (SD) of 19.6 (3.7) test contractions per subject. Rate-rate correlation could only be calculated when the test motor unit was active for more than 2 s, i.e. the correlation comprised more than three data points. Of the 312 pairs for which rate-rate correlation could be calculated, 55 pairs (18%) were excluded because the correlation was less than r=0.7. Of the remaining 279 pairs, 121 pairs (43%) were excluded because the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit was within 0.5 pps of ΔF, indicating potential saturation of the discharge rate in the reference motor unit (see Figure 3). It was possible for some motor unit pairs that exhibited this behavior to have rate-rate correlations greater than r=0.70 due to similar decreases in discharge rates of the reference and test motor units on the descending limb of the contraction. The upper limit imposed on ΔF calculations by the range of discharge rate modulation present in human tibialis anterior motor neurons is illustrated by the large number of excluded motor unit pairs (gray circles) surrounding the line of identity in Figure 4A. This exclusion criterion left 158 motor unit pairs for analysis. These motor units were discriminated from 119 test contractions in 9 participants, with an average (SD) of 13.2 (5.1) test contractions per subject. The details of these contractions are provided in Table 1.

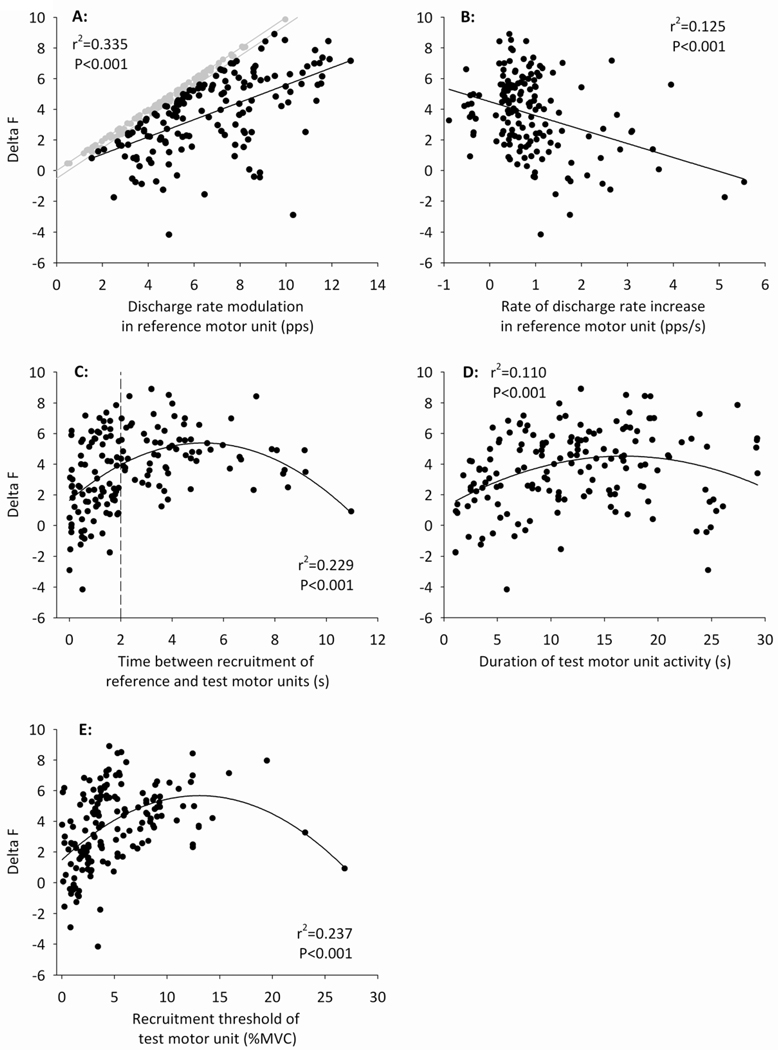

Figure 4.

Relations between ΔF and (A) the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit; (B) the rate of increase in discharge rate of the reference motor unit; (C) the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units; (D) the duration of time for which the test motor unit was active; and (E) the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit. Each relation was fitted with a linear or quadratic function (solid lines), according to the best fit achieved by each model. The variance in ΔF explained by each variable (r2) is displayed on the respective subplots. Data points shown in gray in panel A were excluded from the model because discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit was within 0.5 pps of ΔF, suggesting saturation of the discharge rate (see Methods). Note that negative values of ΔF were obtained only when the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units was less than 2 s (vertical dashed line; panel C).

The mean (SD) ΔF across all included motor unit pairs was 3.7 (2.5) pps, and ranged from −4.2 pps to 8.9 pps. ΔF was significantly related to the discharge characteristics of the reference and test motor units selected for analysis (Figure 4). The amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit was linearly related to ΔF, explaining 34% of the variance in this estimate of PIC magnitude (r2=0.335; P<0.001; Figure 4A). The direction of the linear association was positive, and using a quadratic equation to model this relation did not improve the fit (F=1.636; P=0.203). The rate of increase in discharge rate of the reference motor unit was also linearly related to ΔF, explaining 13% of the variance in ΔF (r2=0.125; P<0.001; Figure 4B). The direction of the linear association was negative, and using a quadratic equation to model this relation did not improve the fit (F=0.187; P=0.666). A quadratic function provided the best fit for relations between ΔF and the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units (r2=0.229, F=27.356, P<0.001; Figure 4C), the duration of test motor unit activity (r2=0.110, F=12.6634, P<0.001; Figure 4D), and the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit (r2=0.237, F=25.157, P<0.001; Figure 4E).

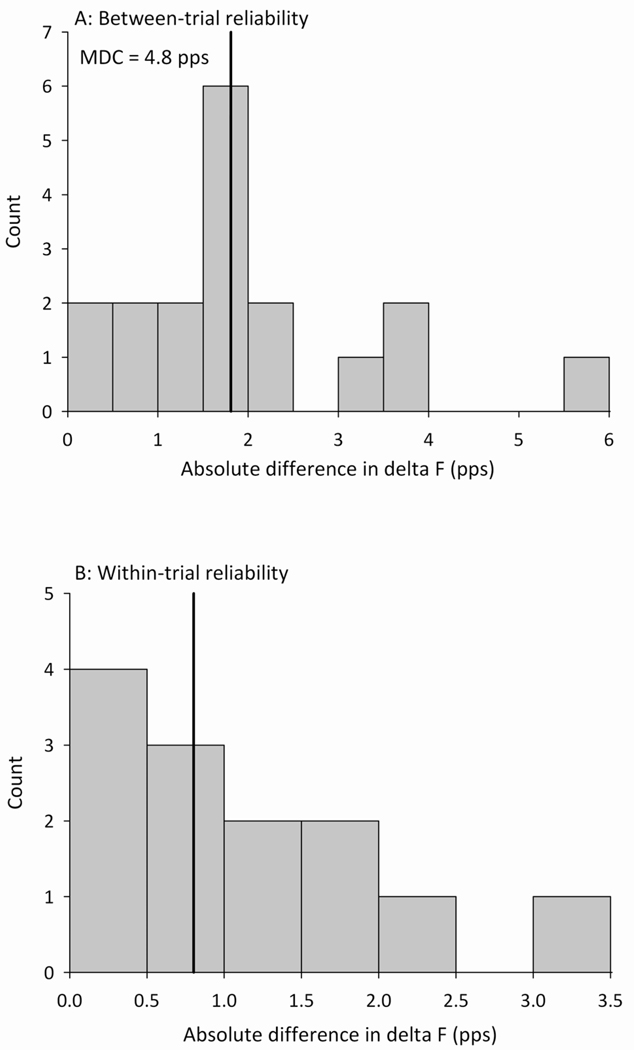

There were several instances (N=18) in which we could confidently identify the same motor unit pair in two or more trials with identical force profiles (peak force within 1% MVC and rate of change in force within 1%MVC/s). These trials were used to assess the between-trial variability in ΔF estimates of PIC magnitude. The median absolute difference in ΔF for the same motor unit pair across trials was 1.8 pps, and the maximum difference was 5.9 pps (Figure 5A). Fourteen of the 18 motor unit pairs (78%) had an absolute difference in ΔF of more than 1 pps between trials. The minimal detectable change in ΔF required to exceed measurement error based on these data is 4.8 pps.

Figure 5.

(A) Distribution of the absolute difference in ΔF estimates for trials in which the same motor unit pair was identified in two or more trials with identical force profiles (N=18). The median difference was 1.8 pps (solid vertical line), with a maximum difference of 5.9 pps between trials. Based on these data, the minimal detectable change (MDC) in ΔF is 4.8 pps. (B) Distribution of the absolute difference in ΔF estimates for cases in which more than one reference motor unit was available to calculate ΔF for a given test motor unit within the same trial (n=13). The median difference was 0.8 pps (solid vertical line), with a maximum difference of 3.4 pps within trials.

There were also several instances (N=13) in which more than one reference motor unit was available to calculate ΔF for a given test motor unit within the same test contraction. These trials were used to assess the within-trial variability of ΔF estimates, dependent on the selection of the reference motor unit. The median absolute difference in ΔF across reference motor units was 0.8 pps, and the maximum difference was 3.4 pps (Figure 5B). In six of the 13 motor unit pairs (46%), ΔF differed by more than 1 pps depending on the choice of reference motor unit.

4. Discussion

This study quantified the variability and the dependence of ΔF estimates on the discharge characteristics of the motor units selected for analysis using the paired motor unit technique in the human tibialis anterior muscle. We found that ΔF was related to the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit, the rate of increase in discharge rate of the reference motor unit, the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units, the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit, and the duration of test motor unit activity. We also found considerable variability in ΔF estimates, both within trials as assessed using different reference and test motor unit combinations and between trials as assessed for the same motor unit pair active during contractions with identical force profiles.

4.1 Dependence of ΔF on discharge rate modulation

The positive linear relation between ΔF and the amount of discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit supports previous findings in the decerebrate cat (Powers et al., 2008). These authors suggested that discharge rate modulation may impose an upper limit on ΔF estimates, which are derived from changes in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit. In the present study, we excluded motor unit pairs for which discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit during test motor unit activity was within 0.5 pps of ΔF. This criterion excluded motor unit pairs for which the discharge rate of the reference motor unit did not continue to increase with further increases in force after the test motor unit was recruited, indicating potential saturation of the discharge rate. Application of this criterion resulted in exclusion of a large proportion (43%) of the motor unit sample for the tibialis anterior muscle. This finding suggests that large numbers of motor unit pairs must be sampled and screened to identify conditions that satisfy the assumptions of the paired motor unit analysis in humans, a procedure which may introduce a sampling bias toward motor neurons with the most prominent PICs. In contrast to our findings, a recent report by Udina et al (2010) found that discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit was typically twice the magnitude of ΔF. This discrepancy is unlikely due to differences in contraction strength or speed, which were similar across the two studies. Methodological differences in the calculation of discharge rate modulation provide a more likely explanation, as we calculated discharge rate modulation of the reference motor unit only during the period of time when the test motor unit was active. This method has been recommended to assess the sensitivity of the reference motor unit to changes in synaptic input that occur in the same timeframe that the PIC is estimated in the test motor unit (Powers et al., 2008). The period of time over which discharge rate modulation was quantified by Udina et al (2010) is not clear, but if the full duration of the reference motor unit activity was assessed, this may explain the apparent discrepancy between studies.

The relation between ΔF and discharge rate modulation in the reference motor unit was present even after excluding ΔF values that were potentially limited by saturation of the discharge rate (Figure 4A). For motor units that did not exhibit saturation, changes in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit reflected variations in synaptic drive to the motor neuron pool. The relation in Figure 4A indicates that ΔF estimates were larger when synaptic input varied over a greater range while the test motor unit was active. This observation is consistent with the graded activation of PICs with increasing levels of synaptic input (Elbasiouny et al., 2006), and may therefore represent a true physiologic variation in the amplitude of the PIC in the test motor unit.

4.2 Dependence of ΔF on rate of increase in the discharge rate

The negative relation between ΔF and the rate of increase in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit supports the recent observation by Revill and Fuglevand (2009) that ΔF decreases with increasing contraction speed. Modeling work from this group suggests that this relation may result from spike-threshold accommodation causing a shift in the threshold for action potential generation to more depolarized levels with slower rates of rise in the depolarizing current, or from spike-frequency adaptation causing a progressive decrease in firing rates that depends on the initial rate of change in current.

Although a linear model provided the best fit for the relation between ΔF and the rate of increase in the discharge rate, it is apparent from Figure 4B that this relation is driven by low ΔF values obtained when the rate of increase in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit was greater than approximately 1 pps/s. Baldissera et al. (1982) demonstrated that motor neuron discharge rates are sensitive to both the magnitude and the rate of change in current. Similarly, Bennett et al. (2001b) reported that the input-output function of a motor neuron becomes non-linear with fast current ramps in the spinal rat preparation, potentially due to spike frequency adaptation (Kernell & Monster, 1982) and rate-dependent dynamics causing the discharge rate to slow over time. The present results indicate that ΔF is strongly related to the rate of increase in the reference motor unit discharge rate at values above 1 pps/s. Bennett and colleagues previously suggested that synaptic inputs must be slowly graded for valid application of the paired motor unit analysis (Bennett et al., 2001a). Our findings refine this recommendation for human applications by demonstrating that ΔF is minimally influenced by the rate of increase in the reference motor unit discharge rate at values less than 1 pps/s.

4.3 Dependence of ΔF on the recruitment interval

The quadratic relation observed between ΔF and the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units supports the hypothesis that ΔF is strongly dependent on the recruitment interval when this time is brief. This is likely due to incomplete activation of the PIC in the reference motor unit upon recruitment of the test motor unit. Figure 4C illustrates that lower ΔF estimates were obtained for recruitment intervals of less than approximately 2 s. These data support a recent report (Udina et al., 2010) that the time course of PIC activation in human motor neurons is likely greater than 1 s as reported for cellular recordings (Bennett et al., 2001b). If the PIC in the reference motor neuron is still activating as the test motor unit is recruited, the discharge rate of the reference motor unit no longer provides a linear estimate of the net synaptic input to the motor neuron pool as has been demonstrated when the PIC is either absent (Granit et al., 1966) or fully activated (Bennett et al., 1998a, b; Bennett et al., 2001b). With incomplete activation of the PIC, Fstart will be falsely low, leading to an underestimation of ΔF. This agrees with the observation that ΔF was lower when the time between recruitment of the reference and test motor units was brief, and may indicate that the magnitude of the PIC in the test motor neuron was underestimated in these cases. Furthermore, we found that all occurrences of negative ΔF values occurred when the test motor unit was recruited less than 2 s after recruitment of the reference motor unit (cf Figure 4C). This is consistent with a previous report of negative ΔF values for motor neurons that are recruited in quick succession in the decerebrate cat (Powers et al 2008). Results from the present study provide the first empirical support for previous recommendations to select trials for the paired motor unit analysis in which the test motor unit is recruited more than 2 s after recruitment of the reference motor unit to allow sufficient time for the PIC to become fully active (Udina et al., 2010).

4.4 Dependence of ΔF on the duration of motor unit activity

The suggestion that the PIC may still be activating up to 2 s after recruitment is supported by the quadratic relation observed between ΔF and the duration of activity in the test motor unit (Figure 4D). This relation is similar to that reported by Udina et al. (2010); ΔF was greater in test motor units that were active for a longer duration, and this relation was present for durations of activity up to 2 s, after which there was a plateau in ΔF. To prevent underestimation of the PIC by ΔF it is recommended that trials selected for the paired motor unit analysis have a duration of test motor unit activity that exceeds 2 s. Interestingly, the quadratic relation between ΔF and both the recruitment interval and the duration of test motor unit activity revealed a decline in at longer durations (Figure 4C–D). This observation may reflect a gradual decline in the magnitude of the PIC over time, however, the time course for the decay of PICs in human motor neurons is currently unknown.

4.5 Dependence of ΔF on recruitment threshold

The relation between ΔF and the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit was best modeled as a quadratic function. From Figure 4E it is apparent that ΔF increases with the recruitment threshold of the test motor unit up to recruitment thresholds of approximately 15–20% of maximum force. This finding supports the results of ΔF estimates in the decerebrate cat (Powers et al., 2008), and may reflect a greater PIC magnitude in higher threshold motor neurons. However, findings based on ΔF estimates are in contrast to cellular recordings in animal models which suggest that, although PICs are more persistent in low threshold motor neurons (Lee & Heckman, 1998a), there is no difference in PIC magnitude across test motor units within a moderate range of recruitment thresholds (Lee & Heckman, 1998a; Bennett et al., 2001a). This discrepancy may be related to the reduced preparation used in animal studies, or may indicate that the relation is caused by factors other than PIC magnitude. Interestingly, our data indicate that ΔF may begin to decline for motor neurons with recruitment thresholds greater than 20% of maximum force (Figure 4E), although this observation requires confirmation with a larger number of motor neurons sampled at high forces.

4.6 Between- and within-trial variability of ΔF

ΔF estimates of PIC magnitude in the human tibialis anterior muscle exhibited considerable variability across trials, even when the force profiles were identical. This observation extends a previous report of significant variability in ΔF estimates in the decerebrate cat (Powers et al., 2008). These authors speculated that the variability observed during reflexive contractions in the cat gastrocnemius muscle might be reduced by controlling the speed and amplitude of voluntary contractions in humans (Powers et al., 2008). To the contrary, results from the present study demonstrate that the variability of ΔF estimates remains high for precisely controlled voluntary contractions. Although we cannot determine whether this variability reflects measurement error or true variation in the magnitude of the PIC across trials, our data do indicate that the paired motor unit analysis may not be sensitive enough to detect subtle physiologic differences in ΔF across different motor behaviors. Calculation of the minimal detectable change indicates that a difference in ΔF of at least 4.8 pps is required to confidently exceed measurement error and detect a change between experimental conditions. A relatively large value for the minimal detectable change in ΔF may explain why previous studies have failed to detect significant differences in ΔF across experimental conditions (Stephenson & Maluf, 2010) or between study populations (Mottram et al., 2009). In contrast to these studies, the paired motor unit analysis has shown significant changes of 2.3 pps in ΔF following amphetamine ingestion (Udina et al., 2010). In this study 5–10 test contractions were used to calculate the average ΔF within each experimental condition, suggesting that the sensitivity of this technique to detect change may be improved by averaging ΔF from several contractions. We also observed variability in ΔF estimates of PIC magnitude for the same test motor unit within a given trial, depending on the reference motor unit that was selected for analysis. This observation suggests that the reliability of the paired motor unit analysis may be improved by using the same reference motor unit to estimate ΔF for a given test motor across experimental conditions. However, the finding that estimates of ΔF for the same motor unit can vary up to 3.4 pps suggests a need for further examination of the validity of this technique.

4.7 Recommendations and Conclusions

Previous authors have indicated that the paired motor unit analysis requires test motor unit activations to be separated by at least 5 s (Bennett et al., 1998a; Bennett et al., 2001b), and rate-rate correlations of at least r=0.7 in the motor unit pairs selected for analysis (Gorassini et al., 2002). Data from the present study indicate that the following additional selection criteria may be useful in further reducing the variability in ΔF estimates of PIC magnitude using the paired motor unit analysis in humans: (1) Discharge rate modulation of the reference motor unit should be greater than ΔF so as not to restrict the upper limit of this measure; (2) The rate of increase in the discharge rate of the reference motor unit should be between 0–1 pps/s to avoid underestimation of ΔF at higher contraction speeds; (3) At least 2 s should separate recruitment of the reference and the test motor units to avoid underestimation of ΔF at shorter recruitment intervals; (4) The test motor unit should be active for at least 2 s to allow sufficient time for full activation of the PIC; and (5) Studies should sample test motor units with a similar range of recruitment thresholds when comparing ΔF across experimental conditions or study populations to avoid sampling bias in ΔF estimates.

Adhering to strict criteria regarding the selection of motor units that meet the primary assumptions of the paired motor unit analysis may increase the reliability of ΔF, however, the validity of ΔF as an in vivo estimate of PIC magnitude in human motor neurons is still unknown. The validity of this measure is supported by results from the chronic spinal rat, where ΔF has been shown to correspond with cellular recordings of PIC magnitude (Bennett et al 2001). However, recent modeling work indicates that factors other than the presence of a PIC may also result in positive ΔF values (Fuglevand & Revill, 2009). Experimental investigations using the paired motor unit analysis to quantify changes in ΔF across different motor behaviors and study populations will benefit from empirically defined selection criteria to optimize the reliability of this technique. Further, the quantitative relations derived from a large sample of human motor units in the present study may be used by future modeling studies to assess the validity of ΔF as an indirect measure of PICs in humans.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH awards R21-AR054181 and TL1-RR025778 to KSM

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baldissera F, Campadelli P, Piccinelli L. Neural encoding of input transients investigated by intracellular injection of ramp currents in cat alpha-motoneurones. J Physiol. 1982;328:73–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin ER, Klakowicz PM, Collins DF. Wide-pulse-width, high-frequency neuromuscular stimulation: implications for functional electrical stimulation. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:228–240. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00871.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton DE. Understanding the relevance of measured change through studies of responsiveness. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3192–3199. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DJ, Hultborn H, Fedirchuk B, Gorassini M. Short-term plasticity in hindlimb motoneurons of decerebrate cats. Journal of neurophysiology. 1998a;80:2038–2045. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DJ, Hultborn H, Fedirchuk B, Gorassini M. Synaptic activation of plateaus in hindlimb motoneurons of decerebrate cats. Journal of neurophysiology. 1998b;80:2023–2037. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DJ, Li Y, Harvey PJ, Gorassini M. Evidence for plateau potentials in tail motoneurons of awake chronic spinal rats with spasticity. Journal of neurophysiology. 2001a;86:1972–1982. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DJ, Li Y, Siu M. Plateau potentials in sacrocaudal motoneurons of chronic spinal rats, recorded in vitro. Journal of neurophysiology. 2001b;86:1955–1971. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin JS, Walsh LD, Nickolls P, Gandevia SC. High-frequency submaximal stimulation over muscle evokes centrally-generated forces in human upper limb skeletal muscles. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:370–377. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90939.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DF, Burke D, Gandevia SC. Large involuntary forces consistent with plateau-like behavior of human motoneurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4059–4065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-04059.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DF, Burke D, Gandevia SC. Sustained contractions produced by plateau-like behaviour in human motoneurones. J Physiol. 2002;538:289–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway BA, Hultborn H, Kiehn O, Mintz I. Plateau potentials in alpha-motoneurones induced by intravenous injection of L-dopa and clonidine in the spinal cat. J Physiol. 1988;405:369–384. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbasiouny SM, Bennett DJ, Mushahwar VK. Simulation of Ca2+ persistent inward currents in spinal motoneurones: mode of activation and integration of synaptic inputs. J Physiol. 2006;570:355–374. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.099119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglevand AJ, Dutoit AP, Johns RK, Keen DA. Evaluation of plateau-potential-mediated 'warm up' in human motor units. J Physiol. 2006;571:683–693. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.099705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglevand AJ, Revill AL. Society for Neuroscience. Chicago, IL: 2009. Effects of persistent inward currents, accomodation, and adaptation on motor unit activity: A simulation study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini M, Yang JF, Siu M, Bennett DJ. Intrinsic activation of human motoneurons: possible contribution to motor unit excitation. Journal of neurophysiology. 2002;87:1850–1858. doi: 10.1152/jn.00024.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini MA, Bennett DJ, Yang JF. Self-sustained firing of human motor units. Neuroscience letters. 1998;247:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini MA, Knash ME, Harvey PJ, Bennett DJ, Yang JF. Role of motoneurons in the generation of muscle spasms after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2004;127:2247–2258. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granit R, Kernell D, Lamarre Y. Algebraical summation in synaptic activation of motoneurones firing within the 'primary range' to injected currents. J Physiol. 1966;187:379–399. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Hyngstrom AS, Johnson MD. Active properties of motoneurone dendrites: diffuse descending neuromodulation, focused local inhibition. J Physiol. 2008a;586:1225–1231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Johnson M, Mottram C, Schuster J. Persistent inward currents in spinal motoneurons and their influence on human motoneuron firing patterns. Neuroscientist. 2008b;14:264–275. doi: 10.1177/1073858408314986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornby TG, Rymer WZ, Benz EN, Schmit BD. Windup of flexion reflexes in chronic human spinal cord injury: a marker for neuronal plateau potentials? Journal of neurophysiology. 2003;89:416–426. doi: 10.1152/jn.00979.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsgaard J, Hultborn H, Jespersen B, Kiehn O. Bistability of alpha-motoneurones in the decerebrate cat and in the acute spinal cat after intravenous 5-hydroxytryptophan. J Physiol. 1988;405:345–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyngstrom AS, Johnson MD, Heckman CJ. Summation of Excitatory and Inhibitory Synaptic Inputs by Motoneurons with Highly Active Dendrites. Journal of neurophysiology. 2008;99:1643–1652. doi: 10.1152/jn.01253.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamen G, Sullivan R, Rubinstein S, Christie A. Evidence of self-sustained motoneuron firing in young and older adults. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2006;16:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernell D, Monster AW. Time course and properties of late adaptation in spinal motoneurones of the cat. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung. 1982;46:191–196. doi: 10.1007/BF00237176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Eken T. Discontinuous changes in discharge pattern of human motor units. J Physiol. 1992;452:277P. [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Eken T. Prolonged firing in motor units: evidence of plateau potentials in human motoneurons? Journal of neurophysiology. 1997;78:3061–3068. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo: systematic variations in persistent inward currents. Journal of neurophysiology. 1998a;80:583–593. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo: systematic variations in rhythmic firing patterns. Journal of neurophysiology. 1998b;80:572–582. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Enhancement of bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo by the noradrenergic alpha1 agonist methoxamine. Journal of neurophysiology. 1999;81:2164–2174. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gorassini MA, Bennett DJ. Role of persistent sodium and calcium currents in motoneuron firing and spasticity in chronic spinal rats. Journal of neurophysiology. 2004;91:767–783. doi: 10.1152/jn.00788.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram CJ, Suresh NL, Heckman CJ, Gorassini MA, Rymer WZ. Origins of abnormal excitability in biceps brachii motoneurons of spastic-paretic stroke survivors. Journal of neurophysiology. 2009;102:2026–2038. doi: 10.1152/jn.00151.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RK, Nardelli P, Cope TC. Estimation of the contribution of intrinsic currents to motoneuron firing based on paired motoneuron discharge records in the decerebrate cat. Journal of neurophysiology. 2008;100:292–303. doi: 10.1152/jn.90296.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather JF, Powers RK, Cope TC. Amplification and linear summation of synaptic effects on motoneuron firing rate. Journal of neurophysiology. 2001;85:43–53. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revill AL, Fuglevand AJ. Society for Neuroscience. Chicago, IL: 2009. Evalutation of an in vivo method to detect persistent inward currents in motor neurons. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson JL, Maluf KS. Discharge behaviors of trapezius motor units during exposure to low and high levels of acute psychosocial stress. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;27:52–61. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3181cb81d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udina E, D'Amico J, Bergquist AJ, Gorassini MA. Amphetamine increases persistent inward currents in human motoneurons estimated from paired motor-unit activity. Journal of neurophysiology. 2010;103:1295–1303. doi: 10.1152/jn.00734.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton C, Kalmar JM, Cafarelli E. Effect of caffeine on self-sustained firing in human motor units. J Physiol. 2002;545:671–679. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]