To the editor:

In coronary heart disease (CHD) patients, depression is highly prevalent (1). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended as first-line antidepressant treatments for this population (2,3). While there is a long-standing notion that SSRIs may improve cardiac prognosis by inhibiting platelet aggregation, SSRI use may also worsen prognosis by increasing bleeding (4), or arrhythmia risk (5).

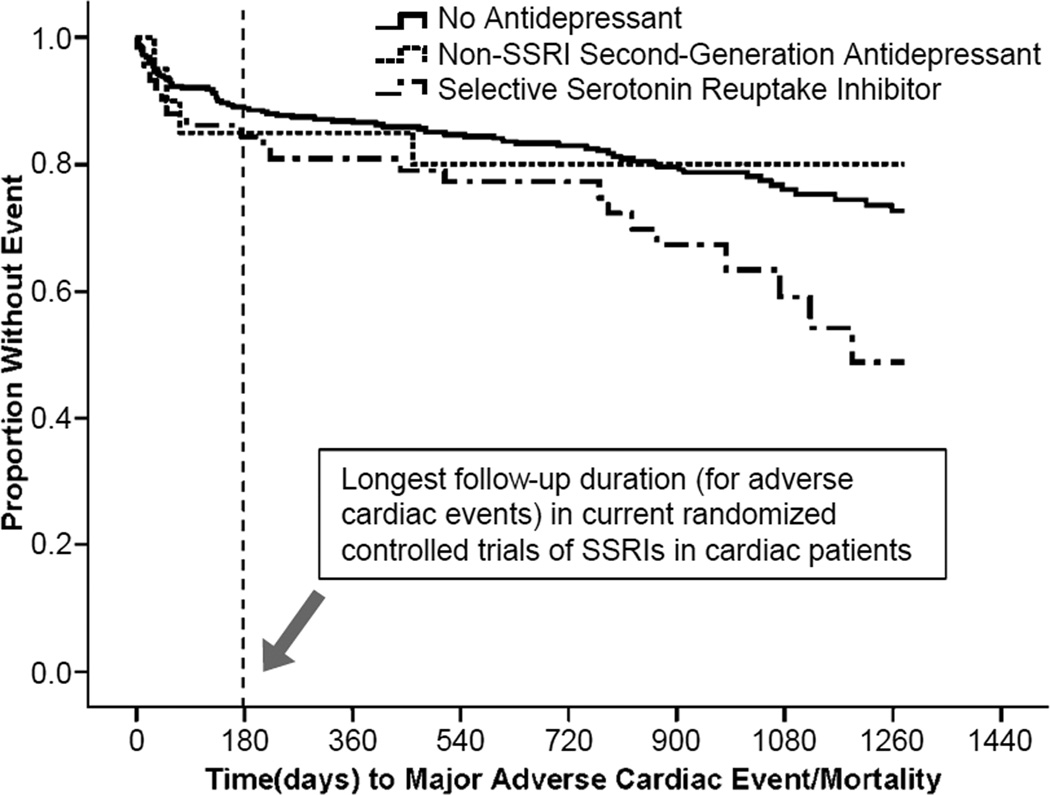

Only a few small randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with a total of 801 patients have assessed the efficacy of SSRIs in patients with a cardiac condition (6,7). Although no evidence for harm was detected in two meta-analyses, the follow-up periods for adverse cardiac events in these RCTs did not extend beyond six months, and patient samples were highly selected (i.e. only patients not already receiving antidepressant therapy in usual care were included, and patients with comorbid conditions were excluded).

Accordingly, we evaluated, in an observational cohort of patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS), the association of SSRI and non-SSRI second-generation antidepressant use with the occurrence of cardiac events and mortality across a period of 42 months.

Methods

Within 1 week of ACS hospitalization, 457 patients completed the Beck Depression Inventory and a diagnostic depression interview (see (8) for details). Antidepressant medication use at hospital admission and discharge was assessed by chart review and self-reports. Medical covariates including a post-ACS prognostic risk score, medical comorbidities, and left ventricular ejection fraction were also assessed. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (hospitalization for nonfatal myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or urgent/emergency percutaneous or surgical coronary revascularization) and mortality were surveyed for up to 42 months.

Statistical Analyses

Three groups were compared according to antidepressant class at admission and/or discharge from index hospitalization: (1) patients not on any antidepressant, (2) patients on SSRI only, and (3) patients on non-SSRI second-generation antidepressants only (see eFigure 1 for specific antidepressants). No patient switched from one to another class during the hospitalization. Because of low numbers (N=21), patients on other antidepressant classes or combinations of antidepressants were excluded. Four additional patients were excluded because they did not complete the depression clinical interview, leaving a sample of 432 patients.

Cox regression analyses were used to estimate differences in time to the first occurrence of either MACE or mortality among the groups (adjusted for age, sex, race, medical covariates (see eTable 2), and depression severity or diagnosis of major depressive episode [MDE]).

Results

Compared to patients not taking any antidepressants (N=354), those on antidepressants (N=78) were more likely to be female and to have current MDE, increased medical comorbidities, and increased depressive symptoms (eTable 1). Compared to patients on non-SSRI second-generation antidepressants (N=20), those on SSRIs (N=58) were more likely to have a prior history of MDE (p=0.06); otherwise, these two groups did not differ.

During a median follow up of 1192 days (range, 1–1278 days), 101 (23.4%) patients had a confirmed MACE or died. Among users of SSRIs, non-SSRI second-generation antidepressants, and patients not on any antidepressant MACE/mortality rates were 36.2%, 20.0%, and 21.5%, respectively.

The Figure shows the Kaplan-Meier survival-curves in the three medication groups. Controlling for demographics, medical covariates, and depression severity, SSRI use carried an increased risk for MACE/mortality compared to no antidepressant use (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–3.06; P=0.02); non-SSRI second-generation antidepressant use did not (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.31–2.42; P=0.78) (eTable 2). Depressive symptom severity was also an independent predictor in the fully adjusted model. Compared to non-SSRI second-generation antidepressant users, SSRI users had an increased hazard of MACE/mortality but this difference was not statistically significant (age- and sex-adjusted HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 0.68–5.81, P=0.21).

Figure.

Event-Free Survival for Combined Major Adverse Cardiac Events/Mortality in Three Medication Groups

There was a significant interaction between antidepressant use (yes/no) and timing of antidepressant use initiation (prior to versus only after the ACS; P = 0.005). Among the 78 AD users, 20 initiated use between the date of admission and the time of hospital discharge. These patients had an increased risk for MACE/mortality compared to patients who did not use antidepressants at all, whereas those who continued SSRIs prescribed prior to the ACS were not at increased risk (eFigure2 and eTable 3).

Comment

Our study shows that SSRI-use may be associated with longer-term risk for adverse prognosis in ACS patients. Limitations are that these analyses were post-hoc, and not powered to detect significant associations between antidepressant exposure and rare adverse outcomes (e.g. stroke, sudden death). Also, the power for analysis of the effects of non-SSRI second-generation antidepressants was limited due to the small number of users. Finally, we could not reliably assess the dosage of antidepressants or the length of time prior to, or after the ACS that patients took a prescribed antidepressant.

We conclude that the comparative safety and efficacy of SSRIs and non-SSRI second generation antidepressants should be investigated in RCTs with larger samples, in “real world” care settings, and critically, with longer follow-up monitoring. The association between dosage, duration of drug coverage, and adherence to antidepressant medications in relation to adverse events after ACS also needs further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Joseph E. Schwartz, Siqin Ye and Matthew M. Burg for their comments on the analyses and an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Dr. Rieckmann conducted the analyses. She had full access to all the data in the study. She takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding / Support:

Funding: This work was supported by grants HC-25197, HL-088117, HL-76857, and HL-84034 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, and supported in part by Columbia University's CTSA grant No.UL1TR000040 from NCATS/NIH. Dr. Kronish received support from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (K23 HL-098359). Dr. Whang received support from the American Heart Association Founders Affiliate (10SDG3720001).

Role of the Sponsor: The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACS

Acute Coronary Syndrome

- MACE

Major Adverse Cardiac Events

- MDE

Major Depressive Episode

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Study concept and design: Rieckmann, Kronish, Shapiro, Whang, Davidson. Acquisition of data: Rieckmann. Analysis and interpretation of data: Rieckmann, Kronish, Davidson. Drafting of the manuscript: Rieckmann, Kronish, Davidson. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Rieckmann, Kronish, Shapiro, Whang, Davidson. Statistical analysis: Rieckmann. Obtained funding: Davidson. Administrative, technical, and material support: Davidson. Study supervision: Davidson.

Relationship with Industry: None declared.

References

- 1.Kent LK, Shapiro PA. Depression and related psychological factors in heart disease. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17:377–388. doi: 10.3109/10673220903463333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Jr, Blumenthal JA, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768–1775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AAFP guideline for the detection and management of post-myocardial infarction depression. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:71–79. doi: 10.1370/afm.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Abajo FJ, Montero D, Rodriguez LA, Madurga M. Antidepressants and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) 2011 Available at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm269086.htm.

- 6.Pizzi C, Rutjes AW, Costa GM, Fontana F, Mezzetti A, Manzoli L. Meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in patients with depression and coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazza M, Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A, Sheiban I, Romagnoli E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors provide significant lower re-hospitalization rates in patients recovering from acute coronary syndromes: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1785–1792. doi: 10.1177/0269881109348176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson KW, Burg MM, Kronish IM, et al. Association of anhedonia with recurrent major adverse cardiac events and mortality 1 year after acute coronary syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:480–488. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.