Abstract

Shigella spp. are food- and water-borne pathogens that cause shigellosis, a severe diarrheal and dysenteric disease that is associated with a high morbidity and mortality in resource-poor countries. No licensed vaccine is available to prevent shigellosis. We have recently demonstrated that Shigella invasion plasmid antigens (Ipas), IpaB and IpaD, which are components of the bacterial type III secretion system (TTSS), can prevent infection in a mouse model of intranasal immunization and lethal pulmonary challenge. Because they are conserved across Shigella spp. and highly immunogenic, these proteins are excellent candidates for a cross-protective vaccine. Ideally, such a vaccine could be administered to humans orally to induce mucosal and systemic immunity. In this study, we investigated the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Shigella IpaB and IpaD administered orally with a double mutant of the Escherichia coli heat labile toxin (dmLT) as a mucosal adjuvant. We characterized the immune responses induced by oral vs. intranasal immunization and the protective efficacy using a mouse pulmonary infection model. Serum IgG and fecal IgA against IpaB were induced after oral immunization. These responses, however, were lower than those obtained after intranasal immunization despite a 100-fold dosage increase. The level of protection induced by oral immunization with IpaB and IpaD was 40%, while intranasal immunization resulted in 90% protective efficacy. IpaB- and IpaD-specific IgA antibody-secreting cells in the lungs and spleen and T-cell-derived IL-2, IL-5, IL-17 and IL-10 were associated with protection. These results demonstrate the immunogenicity of orally administered IpaB and IpaD and support further studies in humans.

Keywords: Shigella vaccines, oral immunization, type III secretion proteins

1.0 Introduction

Shigella spp. are food- and water-borne pathogens that are usually transmitted via the fecal/oral route. They are known for causing shigellosis, which is a severe dysenteric disease that continues to be associated with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in children under 5 years of age living in less-developed areas of the world [1]. Those who overcome the disease often suffer from health and developmental impairment and their life expectancy is reduced [2]. Four major species of Shigella have been described, and each includes several types and subtypes based on the antigenic differences on the O-antigen polysaccharide. Natural infection leads to protective immunity that is serotype specific [3;4]. S. dysenteriae 1, S. sonnei and all sixteen S. flexneri serotypes are associated with the highest morbidity rates and are the main targets of vaccine development efforts. No approved vaccine is presently available to prevent shigellosis. Research efforts to develop prophylactic measures have produced a number of promising vaccine candidates, including whole-cell inactivated organisms [5], live attenuated Shigella strains [6–8], O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines [9;10] and subcellular complexes containing invasion plasmid antigens (Ipas) and LPS [11;12]. These vaccines have been evaluated in human clinical trials with various degrees of success [Reviewed in [13–15]]. A disadvantage of these vaccine prototypes, however, is that they evoke serotype specific immunity associated with the O-polysaccharides, and would therefore protect only against the serotype from which they were derived, not being effective across Shigella spp.

Our group has been pursuing the development of a safe and broadly protective vaccine based on the Shigella type III secretion system (TTSS) proteins IpaB and IpaD as target protective antigens [16]. These proteins assemble at the tip of the TTSS apparatus, which forms a molecular needle and syringe that enables the transfer of microbial effector proteins into the cytoplasm of the host cell to initiate pathogenesis [16]. Because they are conserved across all Shigella spp., immune defenses against the TTSS proteins are expected to confer broad-spectrum protection against multiple serotypes. The concept of a Shigella vaccine based on IpaB/IpaD subunit proteins is also innovative because most of the vaccine candidates available rely on LPS (or a combination of LPS and proteins) to elicit immune responses based on epidemiological evidence of O-serotype-specific protection [3]. Nonetheless, these proteins are highly immunogenic in humans. Antibodies directed against Shigella Ipas have been found in the sera of dysenteric patients [17;18] and in people living in endemic areas [19;20]. The presence of serum IgG and IgA and circulating antibody secreting cells (ASC) specific for IpaB and IpaD has been reported in human adult volunteers who were immunized orally with live attenuated organisms [6;21]. Some of these vaccine recipients also developed B memory responses to IpaB [22].

We have recently shown that intranasal (i.n.) immunization of mice with IpaB and IpaD, along with a double mutant of the heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) of Escherichia coli (dmLT), results in potent immune stimulation and protection against lethal S. flexneri and S. sonnei pulmonary infection [23]. In humans, the administration of this vaccine via i.n. would not be advisable due to safety concerns associated with nasal delivery of LT-derived adjuvants [24;25] and the fact that this route might not be the most effective at inducing immune responses in the gut to protect against dysenteric disease. Ideally, Shigella IpaB and IpaD could be given to humans orally, in the presence of a mucosal adjuvant such as the dmLT, to engender robust mucosal and systemic immunity. Vaccine-induced immunological effectors in the gastrointestinal tract would provide the first line of defense against this pathogen and effectively block bacterial invasion and dissemination. The primary goal of this study was to evaluate the immune responses induced by Shigella IpaB and IpaD when given via the orogastric (o.g.) route in the presence of the E. coli dmLT and to assess the protective efficacy of this approach using a mouse pulmonary challenge model. Our second objective was to characterize the immune responses induced by o.g. and i.n. IpaB and IpaD administration side-by-side and to evaluate the efficacy of both routes of immunization. We also investigated mucosal and systemic immunological markers that were associated with protection.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Protein purification

The E. coli double mutant heat-labile toxin (LT (R192G/L211A) or dmLT) was purified by affinity chromatography as previously described [26]; a GLP-prepared antigen (lot 1575) produced at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research was acquired through PATH-EVI. Recombinant IpaB, IpaB complexed with the chaperone IpgC (IpaB/IpgC) and IpaD were overexpressed in E. coli and purified from the cytoplasmic fraction via standard immobilized metal affinity column (IMAC) chromatography as previously described [23;27]. Protein concentrations were determined though absorbance at 280 nm using extinction coefficients based on the amino acid composition of each protein [28].

2.2 Immunizations, specimen collection and challenge

Female BALB/c mice (8–10 weeks old, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were immunized i.n. on days 0, 14 and 28 with 2.5 μg of IpaB/IpgC combined with 10 μg of IpaD. The groups that were immunized o.g. either received IpaB/IpgC and IpaD individually or both antigens combined at two dosage levels: 200 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 300 μg of IpaD (referred to as the “low dose” group) or 500 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 600 μg of IpaD (referred to as the “high dose” group) on days 0, 14 and 28. The E. coli dmLT was used as adjuvant; 2.5 μg was administered i.n. and 25 μg was administered o.g. The control groups received 25 μg of dmLT or PBS o.g. The immunization procedures are described in detail in Supplementary Information. The animal studies were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3 Antibodies and antibody-secreting cells

Antibodies specific for IpaB, IpaD and dmLT were measured in serum, stool and mucosal lavages by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described [23]. Total IgG and IgA were measured using a similar assay, except that plates were coated with 0.5 μg/ml of goat anti-mouse IgG (γ-chain specific) or goat anti-mouse IgA (α chain specific, both from Southern Biotech). The frequency of IgG- and IgA-secreting cells was measured by ELISpot as previously described [23;29], with modifications. These assays are described in detail in Supplementary Information.

2.4 Cytokine secretion

Splenocytes were incubated for 48 h with 5 μg/ml of IpaB, IpaD or dmLT, and the supernatants were removed and stored at −20°C until analysis. Cytokine levels were measured using an MSD Mouse TH1/TH2 9-Plex Assay to measure IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-10 and MSD Mouse IL-17 Assay Ultra-Sensitive Kit to determine levels of IL-17 (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). Culture supernatants were added to plates pre-coated with cytokine-specific antibodies following manufacturer’s instructions. The results are reported in pg/ml as the means from triplicate wells.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The overall differences in antibody responses among groups over time and between mice immunized o.g. vs. i.n. were determined using Two-way ANOVA with Bonferonni correction. Unpaired t test with a 95% confidence interval was used to compare responses at single time points between a specific group and PBS controls. Vaccine-induced IgG and IgA ASC responses within groups were compared using One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Survival curves were analyzed using a logrank (Mantel-Cox) test. Linear regressions of the percent survival vs. the levels of antibodies, ASC frequency and concentration of cytokines were generated, and analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) with a two-tailed 95% confidence interval to determine significance. A P value <0.05 was considered significant in all analyses.

3.0 Results

3.1 Serum and mucosal antibodies induced by orally and intranasally delivered IpaB and IpaD

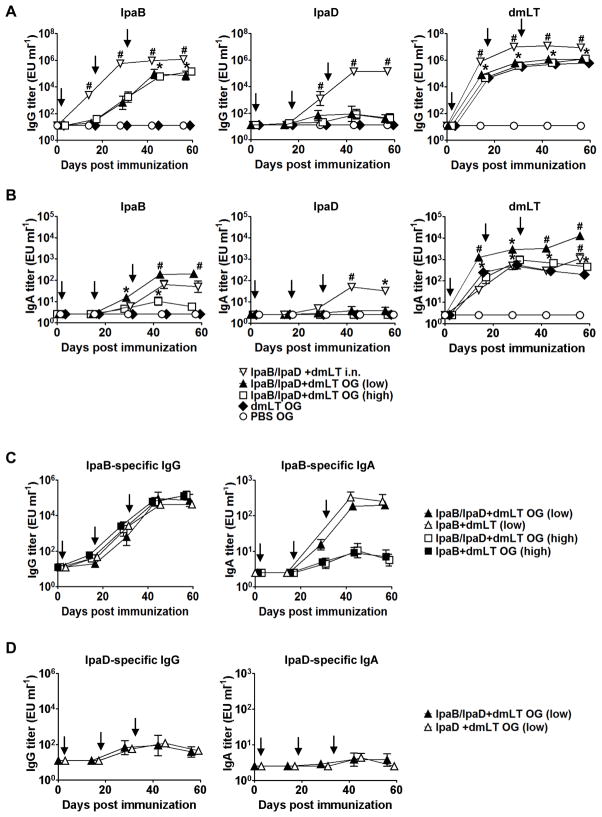

Previous results from our group have shown that mice immunized i.n. with Shigella IpaB and IpaD admixed with E. coli dmLT were protected against lethal pulmonary S. flexneri and S. sonnei challenge [23]. Because shigellosis causes an enteric infection in humans, oral immunization would be ideal to engender local immunity that could block the pathogen at the entry site. With this goal in mind, we examined the immunogenicity of IpaB/IpgC and IpaD when administered to mice orally in the presence of the E. coli dmLT as adjuvant. Two studies were performed in which we tested different amounts of protein: 200 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 300 μg of IpaD (low dose) or 500 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 600 μg of IpaD (high dose). In either treatment, the proteins were admixed with 25 μg of dmLT. Mice immunized i.n. with 2.5 μg of IpaB/IpgC, 10 μg of IpaD and 2.5 μg of dmLT were included as positive controls. The group vaccinated i.n. exhibited the highest levels of serum IgG in response to each of the vaccine antigens: IpaB, IpaD and dmLT (Figure 1A). Mice that were vaccinated orally developed high serum IgG responses against IpaB. Interestingly, there was no difference between the IpaB-specific IgG titers produced by the high- and low-dose groups despite the ~2-fold difference in the amount of protein administered; mean kinetic peak titers were 3.5×105 EU/ml and 5.7×105 EU/ml, respectively (Figure 1A). The antibody responses in mice immunized orally were also delayed when compared with the responses of mice immunized i.n. The group immunized i.n. had IpaB-specific IgG titers of 5.5×103 EU/ml by day 14, while mice immunized orally did not attain this level until day 28, which was 1 week after the second immunization (Figure 1A). Despite being delayed, the IpaB IgG responses of orally immunized mice continued to rise and reached a plateau on day 42. Mice immunized i.n. also developed robust serum IgG responses to IpaD, which achieved a mean peak titer of 3.9×105 EU/ml. In contrast, the groups that were immunized o.g. responded poorly to IpaD (mean IgG peak titers ~3×102 EU/ml) (Figure 1A). As observed for IpaB, the larger amount of IpaD in the high-dose treatment failed to enhance the serum IgG responses (Figure 1A). Regardless of the route of immunization, the IgG responses to IpaD were consistently lower than the responses produced against IpaB (Figure 1A). This observation raised the question as to whether the immunogenic capacity of the proteins would be different when combined as opposed to when given alone. In parallel experiments, we compared the serum IgG and IgA responses induced by oral administration of IpaB/IpgC and IpaD in the presence of dmLT given either individually or combined, and found that very similar responses were induced by both proteins regardless of how they were administered (i.e., individually or combined) (Figure 1C and D). High levels of dmLT-specific serum IgG were induced following i.n. and o.g. immunization. Despite a significant half-log difference in the titers across time points, the kinetics of dmLT antibody production were identical for both routes (Figure 1A). No differences were found among the dmLT titers in the orally immunized groups at any time point, which indicates that for all treatments the dosing procedure was adequate and consistent (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. IpaB-, IpaD-, and dmLT-specific serum IgG and stool IgA levels.

Mice were immunized via orogastric (o.g.) or intranasal (i.n.) routes with IpaB that was complexed to its chaperone, IpgC (IpaB/IpgC), and/or IpaD admixed with the E. coli double mutant heat-labile toxin (dmLT) on days 0, 14 and 28 (arrows). The low o.g. dose corresponds to 200 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 300 μg of IpaD (n=10). The high OG dose corresponds to 500 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 600 μg of IpaD. The same amount of dmLT (25 μg) was used in all of the experimental groups. Mice that were immunized i.n. received 2.5 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 10 μg of IpaD with 2.5 μg of dmLT (n=10). These data combine the results from two independent studies with 10–20 mice per group. (A) IpaB-, IpaD- and dmLT-specific serum IgG and (B) stool sIgA levels measured by ELISA. (C) IpaB- and (D) IpaD-specific serum IgG and stool IgA levels induced by the Ipas individually or combined. The mice received 200 and 500 μg of IpaB/IpgC and 300 μg of IpaD. The data represent mean titers ±SEM from 10 mice in each group. Statistically significant differences are indicated by * for P < 0.05 compared to PBS and # for P < 0.05 compared to the high-dose o.g. and PBS groups.

To assess the mucosal antibody responses, we measured the kinetics of IpaB and IpaD-specific IgA in stools (Figure 1B). Mice that were immunized o.g. developed the highest levels of IpaB-specific secretory IgA (sIgA), which slightly surpassed the levels produced by mice immunized i.n. Surprisingly, the mice that received the lowest amount of IpaB had the highest stool sIgA responses. This group also developed the highest sIgA responses to dmLT, which also surpassed the responses of mice immunized i.n. The difference in dmLT responses among orally vaccinated mice was unexpected because all of the groups received the same amount of dmLT and exhibited similar serum antibody levels. Oral delivery of IpaD failed to induce stool sIgA, whereas significant titers were observed in mice that had been immunized via the nasal route. No response to any of the vaccine antigens was observed in the negative control groups (<25 EU/ml) (Figure 1 A & B). In addition to the vaccine-specific IgA, we also measured the total amount of IgA in each stool supernatant. The fecal IgA content of the individual samples clustered within a narrow range, from 1.5 to 2.5 pg/ml, and there were no statistically significant differences among the various groups; for that reason, no further normalization of the data was deemed necessary.

3.2 Systemic and mucosal ASCs induced by orally delivered IpaB and IpaD

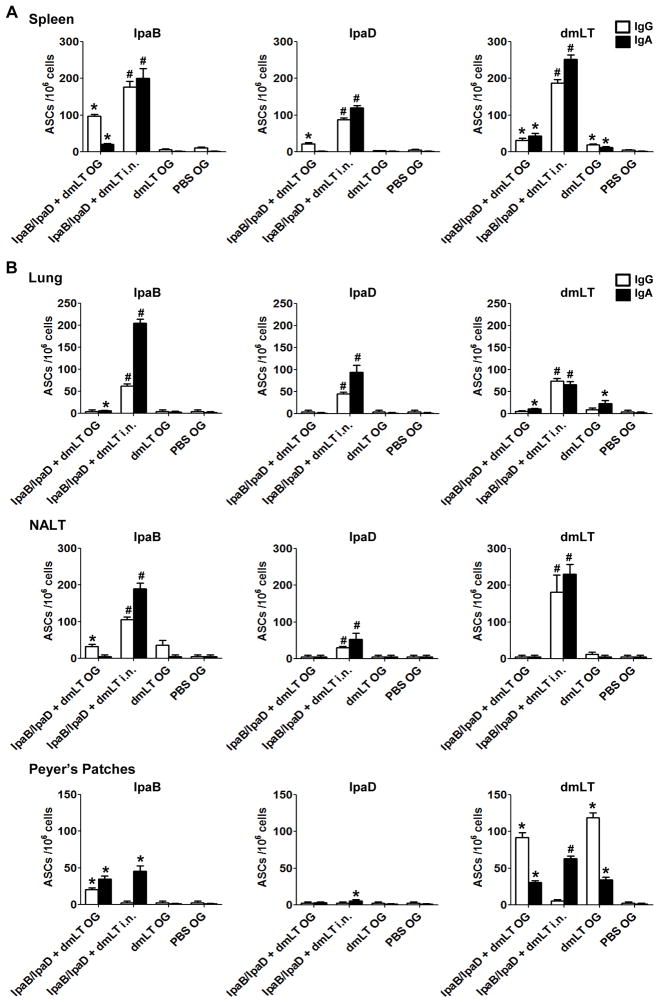

To further characterize the responses induced by oral immunization with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD, we investigated the presence of IgG and IgA ASCs in the spleen. These cells are believed to represent plasma cells that actively secrete antibodies to maintain antibody levels in the circulation. Only mice immunized with the high dose of Ipas were included in these experiments. IpaB-specific IgG and IgA were detected in mice immunized orally; the number of IgA ASCs was significantly lower than the number of IgG ASCs, yet above the negative controls (Figure 2A). Mice that were immunized i.n. developed very strong IgG and IgA IpaB ASC responses that exceeded the responses of the orally immunized mice. The pattern of responses was similar for IpaD, except that the magnitude was considerably lower. The groups immunized orally also developed IgG and IgA ASC responses to dmLT, although again the levels were lower than mice that were immunized i.n. (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the proportion of IgG vs. IgA ASCs induced varied depending on the antigen and route delivery. For the most part, mice immunized i.n. developed higher frequencies of IgA ASC, whereas the mice that were immunized orally produced predominantly IgG ASCs. A very similar IpaB and IpaD ASC response profile, but with lower counts, was found in the bone marrow (data not shown).

Figure 2. IpaB-, IpaD- and dmLT-specific IgG and IgA ASCs in spleens and mucosal tissues.

Mice were immunized with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD (high dose) as described in Figure 1. Cells from (A) Spleen and (B) lungs, nasal tissue (NALT) and Peyer’s patches were obtained on day 35 post-vaccination from 5 mice in each group and stimulated overnight with IpaB, IpaD and dmLT. ASC frequencies were measured by ELISpot. The results show mean IgG and IgA ASC counts per 106 cells +SEM from quadruplicate wells. Statistically significant differences are indicated by * for P < 0.05 compared to PBS and # for P < 0.05 compared to the o.g. and PBS groups.

We also assessed the presence of vaccine-induced ASCs in the lungs, nasal tissues and Peyer’s patches. ASCs residing in the lungs are relevant for protection against pulmonary infection in our mouse model, whereas ASCs in the gut would be important for protection against enteric infection in humans. IpaB- and IpaD-specific IgG and IgA ASCs were found in the lungs of i.n. immunized mice but were nearly absent in mice that were immunized orally, except for very low levels of IgA ASCs against IpaB and dmLT (Figure 2B). A very similar response pattern was observed in nasal tissues (Figure 2B). IgA and IgG ASCs against IpaB were detected in the Peyer’s patches of orally immunized mice whereas only an IgA ASC response, albeit of similar level, was detected in mice immunized i.n. The ASC responses to IpaD were negligible. Interestingly, orally delivered dmLT induced robust IgG ASCs as well as mid-level IgA responses, whereas dmLT administered i.n. only produced IgA ASC. Consistent with the pattern of ASC responses found in the spleen, a larger proportion of vaccine-specific IgA ASCs (as compared to IgG) was seen in mucosal tissues of mice immunized i.n. (Figure 2).

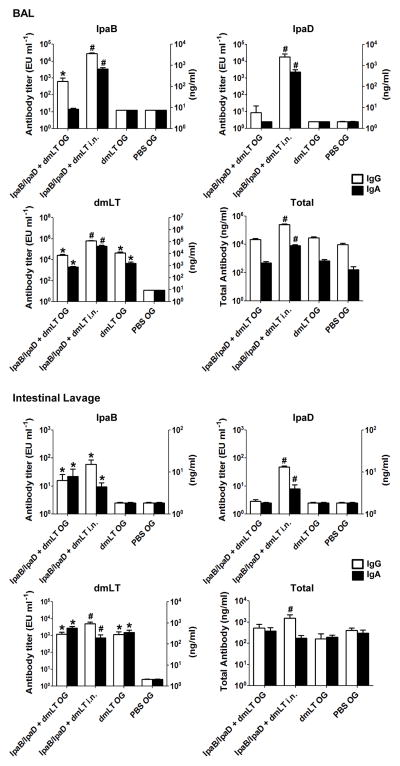

3.3 Antibodies in bronchoalveolar and intestinal lavages

We also assessed the mucosal immune responses induced through o.g. and i.n. immunization with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD by measuring vaccine-specific and total IgG and IgA antibodies in bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) and intestinal lavage fluid (Figure 3). Mice immunized i.n. exhibited the highest levels of alveolar IgG and IgA specific for all 3 antigens. In fact, intranasal vaccination per se enhanced the production of total bronchoalveolar IgG and IgA, which was not seen in the orally immunized groups. Mice immunized orally developed IpaB-specific IgG BAL responses as well as IgG and IgA responses to dmLT; the magnitude of these responses, however, was somewhat lower compared with mice immunized i.n. To our surprise, IgG responses (as opposed to IgA) prevailed in the BAL fluids, regardless of treatment. Vaccinated mice also exhibited IpaB-specific IgG and IgA in intestinal secretions in levels that were similar between i.n. and o.g. immunized mice. Antibodies to IpaD were detected in mice immunized i.n. only. All vaccinated groups had relatively high and broadly similar levels of intestinal dmLT-specific IgG and IgA (Figure 3). The intestinal fluids contained similar amounts of total IgG and IgA, except for a significant increase of total IgG in the i.n. group. The levels of IgG specific for all 3 antigens also exceeded those of IgA in this particular group. No responses to IpaB or IpaD were detected in the BAL or intestinal washes of the PBS controls.

Figure 3. IpaB-, IpaD- and dmLT-specific IgG and IgA in BAL and intestinal fluids.

Mice were immunized orally with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD (high dose). BAL and intestinal fluids were collected on day 35 from 5 mice in each group, and antigen-specific, total IgG and total IgA antibody titers were measured by ELISA. The results shown are mean titers ±SEM from individual mice. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test: * P < 0.05 compared to PBS and # P < 0.05 compared to the o.g. and PBS groups.

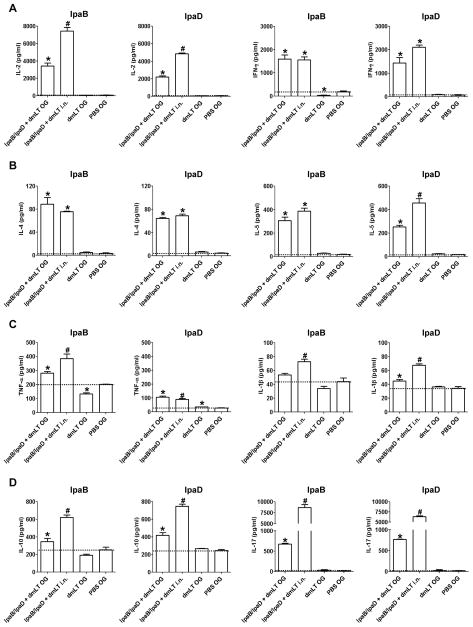

3.4 Cytokine responses induced by mucosally delivered IpaB and IpaD

To investigate the induction of antigen-specific T cells following vaccination, we measured the levels of Th1, Th2, Th17 and pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by spleen cells stimulated in vitro with IpaB and IpaD. We examined the production of IL-2 as a marker of activated and proliferating T cells and IFN-γ as an indicator of Th1 immunity. Mice that were immunized with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD, either orally or i.n., produced high levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ upon antigenic stimulation (Figure 4A). Higher IL-2 responses were observed in mice that were immunized i.n. whereas the production of IFN-γ was similar, regardless of the immunization route. In addition, we measured the levels of IL-4 and IL-5 as Th2 cytokines involved in the activation of B cells and antibody production. Both the o.g. and i.n. vaccinated mice produced significant levels of IL-4 and IL-5 in response to IpaB and IpaD (Figure 4B). The IL-5 responses to IpaD were significantly higher in the i.n. vaccinated group. We also measured the induction of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, which contribute to protection by recruiting neutrophils and phagocytic cells to the site of infection and promoting Th1 adaptive effector responses during bacterial invasion. TNF-α and IL-1β were produced in response to IpaB and IpaD stimulation in both the o.g. and i.n. immunized animals (Figure 4C). Mice that were immunized i.n. produced significantly higher levels of TNF-α in response to IpaB than mice immunized orally, although both groups responded similarly to IpaD (Figure 4C). Mice that were immunized i.n. also produced larger amounts of IL-1β in response to both IpaB and IpaD (Figure 4C). As an indicator of regulatory T cell responses, we measured the production of IL-10 by IpaB- and IpaD-stimulated splenocytes. The levels of IL-10 were elevated in the vaccinated groups; most notably in the i.n. immunized mice (Figure 4D). Lastly, we measured the production of IL-17, which is known to induce isotype class switch and activation and recruitment of CD4+ Th1 cells in mucosal tissues. Significant production of IL-17 by IpaB and IpaD-specific T cells was observed in mice immunized o.g. and i.n., the latter being the highest responders (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. IpaB- and IpaD-specific cytokine responses.

Mice were immunized with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD (high dose). Spleens were obtained on day 56 from 5 mice in each group and single-cell suspensions were prepared. The cells were incubated for 48 h with IpaB or IpaD, and cytokine levels in the culture supernatants were measured using a Th1/Th2 9-Plex Assay or IL-17 Assay Ultra-Sensitive Kit (MSD). The results shown are the mean concentrations of (A) IL-2 and IFN-γ, (B) IL-4 and IL-5, (C) TNF-α and IL-1β and (D) IL-10 and IL-17 in pg/ml +SEM from triplicate wells. The dotted lines denote the baseline cytokine levels from PBS controls. Statistically significant differences are denoted by * for P < 0.05 compared to PBS and # for P < 0.05 compared the o.g. and PBS groups.

3.5 Protective efficacy against lethal S. flexneri pulmonary challenge

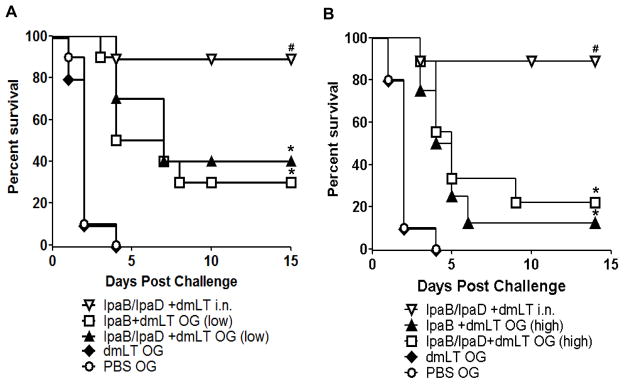

Finally, to assess the protective efficacy of orally delivered IpaB/IpgC and IpaD, the mice were subjected to pulmonary challenge with virulent S. flexneri one month after the last immunization (Figure 5). Two studies were performed in mice that were immunized with the low- and high-dose vaccines, and each study included a challenge step with appropriate controls. In both challenges, the attack rate in the dmLT and PBS controls was 100% with deaths occurring 2–4 days after challenge (Figure 5A–B). Mice that were immunized i.n. exhibited the highest level of protection (90%), whereas in the mice that were immunized orally the protective efficacy varied from 20% to 40%. Mice receiving the lower dose of IpaB/IpgC and IpaD had a moderate 40% protection (Figure 5A), while those immunized with the higher dose exhibited 20% protection (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Protection against lethal S. flexneri pulmonary challenge.

Mice were immunized as described in Figure 1 and challenged on day 56 post-vaccination with 4.7×107–5.3×107 CFU of virulent S. flexneri 2a. The data represent survival curves from 10 mice per group. Statistical significance was determined using a logrank (Mantel-Cox) test with a 95% confidence interval. Statistically significant differences are indicated by * P < 0.05 compared to PBS and # P < 0.05 compared to the IpaB/IpaD+dmLT o.g. and PBS groups.

3.6 Analysis of responses associated with protection against Shigella pulmonary infection

To identify immunological markers associated with protection in this model, we compared key immune responses relevant to pulmonary protection in vaccinated mice with the group’s corresponding percent survival after challenge using linear regression analysis (Table 1). Despite that only a few groups could be included in this analysis, the trend observed was that IpaB- and IpaD-specific antibody titers in the BAL and the frequencies of spleen and lung ASCs were the responses more closely associated with protection, with correlation coefficients≥0.85 (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Among the cytokines measured, IL-2, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-17 were associated with protection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association between immune responses to IpaB and IpaD and protection against lethal challenge.

| IpaB-specific responses | IpaD-specific responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Immune response | Correlation coefficient (Pearson r)a | Correlation coefficient (Pearson r)a |

| Serum IgG b | 0.47 | 0.94 |

| BAL IgG c | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| BAL IgA c | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Spleen IgG ASC c | 0.85 | 0.98 |

| Spleen IgA ASC c | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Lung IgG ASC c | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| Lung IgA ASC c | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| NALT IgG ASC c | 0.80 | 0.99 |

| NALT IgA ASC c | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| IL-2 d | 0.97 | 0.99 |

| IFN-γ d | −0.62 | 0.99 |

| IL-4 d | −0.05 | 0.75 |

| IL-5 d | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| IL-10 d | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| TNF-α d | 0.66 | 0.29 |

| IL-1β d | 0.67 | 0.99 |

| IL-17 d | 0.99 | 0.99 |

The immune responses measured in groups vaccinated with the IpaB and IpaD i.n. and o.g. and their respective percent survival were analyzed using linear regression and Pearson correlation coefficients (r) calculated. Control mice that received PBS or dmLT were excluded from the correlation analysis.

The serum antibody levels correspond to the mean titers from each of the vaccinated groups shown in Figure 1, measured on day 55 post-immunization.

The BAL antibody levels, spleen, NALT and lung ASC correspond to the values measured in mice vaccinated with IpaB and IpaD i.n. and o.g (high dose); cells were obtained on day 35 post-primary vaccination.

The cytokine responses were measured in spleen cell cultures from mice vaccinated with the Ipas i.n. and o.g. (high dose); spleens were obtained on day 56 after primary immunization.

4.0 Discussion

We have previously reported that Shigella TTSS proteins IpaB and IpaD are highly immunogenic and protective against lethal pulmonary infection with S. flexneri and S. sonnei when administered to mice i.n. [23]. These results generated great enthusiasm to further investigate the usefulness of a TTSS protein-based vaccine for broad protection against shigellosis. Because Shigella is an enteric pathogen, it would be ideal to have a vaccine that could be administered orally to maximize in the induction of protective immunity in the gut. Oral immunization would favor the induction of mucosal immunity at the site of infection where local defenses could inhibit bacterial invasion and colonization, thus preserving the integrity of the colonic epithelial barrier, which is typically disrupted during Shigella pathogenesis [31]. The oral route is also desirable because it allows for practical vaccine delivery (i.e., it can be self-administered); oral administration is also safer and better tolerated than parenteral injection.

Extending the successful results that were obtained using the nasal route, we demonstrate in this study that both IpaB/IpgC and IpaD are likewise immunogenic when administered to mice via the o.g. route. IpaB induced the highest levels of antibodies in serum and mucosal secretions and the highest frequencies of systemic and mucosal ASCs. These responses, however, were not as robust as the responses of mice immunized i.n. Oral immunization with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD also resulted in the activation of T cells and the production of Th1- and Th2-type cytokines. Unlike the serological and ASC responses, which were mainly against IpaB, both of the proteins evoked comparable levels of cytokines, which suggests a differential capacity for stimulation of B and T cells for each of the proteins. The higher levels of IL-2, IL-5, IL-17 and IL-10 that were observed in mice that were immunized i.n. also suggest more robust T-cell priming when the proteins are delivered through this route.

The reduced immune responses following oral vaccination were reflected in the decreased survival rates following experimental lethal challenge. The highest protective efficacy for orally administered IpaB/IpgC and IpaD was 40%, while almost full protection was consistently achieved when the proteins were delivered via the nasal route. The oral route had a modest performance despite a 10–200 fold increase in the dosage that was delivered compared to the i.n. route. Although disappointing, the lower efficiency of oral immunization was not surprising. The limited performance of this route for the purposes of vaccination, both in animal models and in humans, is well documented in the literature [32–34]. Some of the possible reasons that could explain our limited success include the tolerogenic environment prevalent in the gut [35], protein degradation, competition with food and flora [36], and the use of different routes for vaccination and challenge. The difference in immune responses observed might also reflect the intrinsic immunogenic capacity of each of the proteins, which is more noticeable when using a less efficient route (oral, as opposed to intranasal). However, the finding that the immune responses to the adjuvant dmLT were lower when it was administered orally than when administered i.n. points to a lower efficiency of the oral route per se. Despite this difference, the responses to the dmLT were steady and robust, consistent with previously reported results [23;37;38].

We hypothesized that we could enhance the immune responses by increasing the amount of Ipas in the vaccine dose. The opposite was true; doubling the amount of protein not only failed to improve the serum IgG levels, but it also greatly reduced the sIgA and protection levels. One possible explanation is that at higher dosage levels the efficiency of antigen uptake and/or presentation is compromised or further reduced.

Our analysis of protective efficacy was performed using the pulmonary mouse model, but this model may not accurately reflect the potency of orally delivered vaccines. In addition to the decreased immune responses, the mismatch in routes (oral vaccination and intranasal challenge) may have resulted in insufficient levels of specific immune effectors at the site of infection. Intranasal vaccination may afford better protection against pulmonary challenge, whereas a model of gut infection that recapitulates human disease would be more suitable to test oral vaccines and may show different (and potentially better) results.

The superior immunogenicity and efficacy of the Ipas when administered i.n. and the limited protection achieved through oral vaccination provided us with an opportunity to study the immunological effectors potentially associated with protection. Mice that were immunized i.n. had very high numbers of IgG and IgA ASCs, both in the systemic and mucosal tissues. The high frequencies of IgG and IgA ASCs in the lung were particularly notable. These cells are expected to become activated when exposed to vaccine antigens and secrete antibodies that can recognize the organism and block mucosal invasion. Goldberg et al. reported the presence of plasma cells in histological lung sections of mice that have been immunized i.n. with a S. flexneri live attenuated vaccine (SSW) and that were protected against pulmonary challenge [39]. Here, we quantified the frequency of IpaB- and IpaD-induced ASCs in the lungs and spleens of mucosally immunized mice and provide evidence of their capacity to secrete antibodies and of their association with a protective outcome. Elevated sIgA and IgG levels in the BALs of vaccinated mice also correlated with increased survival in the pulmonary challenge model, which supports the hypothesis that local antibodies contribute to preventing infection. The superior levels of IgG, as opposed to IgA, in the BAL fluids and the lack of correspondence with IgG and IgA ASC frequencies in the lung were intriguing. The higher IgG titers might reflect additional IgG not produced by local ASC but transudated or “leaked” from circulation into the alveolar space. Alternatively, the superior IgG titers might imply that more antibodies were produced by IgG ASCs compared to IgA ASCs. Modest levels of antibodies and very low to negligible ASC numbers were found in the intestines of orally vaccinated mice. The majority of these animals succumbed to disease, which suggests that a threshold level of mucosal ASCs capable of promptly synthesizing antibodies upon infection, rather than a constitutive level of sIgA, is needed for protection. Mucosally primed ASCs induced by oral Shigella vaccines have been associated with reduced disease in humans experimentally challenged with virulent strains [40]. In our mouse model, the ASCs that were detected in the spleen and bone marrow might represent reservoirs of the ASCs that were detected in the lungs; vaccine-induced ASC and plasma cells residing in central lymphoid tissues could migrate quickly to mucosal effector sites upon antigen exposure.

While the protective mechanisms of mucosal IgA are well described, the contribution of IgG to the protection of mucosal surfaces is less clear. Proponents of O-polysaccharide Shigella conjugate vaccines, for which protection has been associated with the production of IgG, contend that the organism is cleared through IgG-dependent complement-mediated lysis and opsonophagocytosis [41]. IgG (and IgA) antibodies against IpaB and IpaD may act differently considering the way in which the TTSS contributes to pathogenesis. Shigella invasion requires the assembly of the TTSS machinery. Once the Shigella needle has been polymerized, IpaD positions itself at the tip of the TTSS needle and controls the translocation of IpaB and IpaC [27]. IpaD senses the environment and the location in the gastrointestinal tract, and once inside the colon, it recruits IpaB to the needle tip. This complex then interacts with the host cell and inserts itself to deliver Shigella effector proteins. Thus, IpaB- and IpaD-specific antibodies could block bacterial-host cell contact and prevent the translocation of virulent proteins. Consistent with this hypothesis, we have observed that maximum protection is achieved when both IpaB and IpaD are part of the vaccine [23]. Orally vaccinated mice not only had reduced IpaB responses, but they also failed to produce antibodies against IpaD, which may explain, in part, their lower survival. The exact mechanisms by which both IgG and IgA against the Ipas mediate protection and their relative contributions remain to be explored.

Cell-mediated immune responses induced by IpaB and IpaD might also contribute to protection through the induction of cytotoxic effectors and the production of Th1- and Th2-type cytokines [42]. The consistently high and sustained systemic and mucosal antibody responses to the Ipas, particularly IpaB, denote an underlying T-helper response, which is essential for B-cell activation, differentiation and the generation of B-cell memory. IFN-γ-secreting T cells specific for IpaB and IpaD were produced after o.g. and i.n. immunization, and they produced similar amounts of cytokine. IFN-γ recruits and activates phagocytic and cytotoxic cells, which further enhance innate defenses to clear the organism [43;44]. TNF-α and IL-1β were also induced, although the induction was stronger when the proteins were administered i.n. TNF-α recruits phagocytic cells, while IL-1β activates the vascular epithelium to allow access of effector cells to the site of infection; together, they assist in microbial clearance. IL-1β has also been implicated in the activation of Th17 cells [45]. CD4+Th17 cells, which secrete IL-17, IL-21, IL-22, IL-6 and TNF-α, have been shown to contribute to protection against respiratory and intestinal bacterial infections [30;46]. In our study, high levels of IL-17 were produced by IpaB and IpaD-specific T cells induced by o.g and i.n. vaccination, which correlated with protection against pulmonary lethal infection. This finding is in agreement with the reported preferential induction of Th17 cells in lungs of mice after primary S. flexneri infection, which restricted bacterial growth and reinfection [47]. While Th17-mediated protection may involve multiple mechanisms, the recruitment of neutrophils and Th1 type cells and the stimulation of antibody production (mucosal IgA and opsonic IgG) [30] could be particularly relevant for clearance of Shigella. Comparable levels of vaccine-induced IL-4 and IL-5 were found in orally and i.n immunized mice, which is consistent with the elevated levels of serum antibodies. IL-10 was also produced, and at higher levels when the Ipas were given i.n. IL-10 is expected to suppress macrophages and modulate T and B cells. Shigella spp. invade macrophages and induce apoptosis, and the released organisms further spread through the mucosal epithelium [48]. IL-10 may help reduce the number of apoptotic macrophages, which would prevent further microbial dissemination.

Interestingly, significant associations were observed between the level of IL-2, IL-5 and IL-10 and IL-17 induced by both IpaB and IpaD and protection in our mouse model. This is the first description of multiple antigen-specific cytokines being produced in animals immunized o.g. or i.n. with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD; their concerted role in protection infection has yet to be elucidated. We also report an association between BAL antibodies, lung and spleen IgA ASCs and protection against Shigella infection in this model. These measurements could be helpful to predict vaccine performance during pre-clinical evaluation of vaccine candidates.

In conclusion, we show for the first time that o.g. immunization with IpaB/IpgC and IpaD admixed with the E. coli dmLT elicits a mucosal and systemic immunity that includes antigen-specific antibodies, ASCs and cytokine-secreting T-cells. We also provide evidence of protection against lethal infection. Although oral immunization was significantly less effective than i.n. vaccination, this approach could be improved by adjusting the vaccine formulation or by using delivery systems and alternative adjuvants. Overall, these results support further investigation of these proteins in other animal models and in humans.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Mice were immunized orally with Shigella TTSS proteins IpaB/IpaD and E. coli dmLT

Vaccine-specific immune responses and moderate protection were observed

Compared side-by-side, the nasal route was more effective than the oral route

IgA secreting cells and IL-2, IL-5 and IL-10 were associated with protection

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. Lillian Van De Verg, Dr. Richard Walker and Dr. Lou Burgeois from PATH-EVI for their contributions to the design of the experiments, guidance and critical reading of this manuscript. We also thank Olga Franco-Mahecha, Kathryn Bowser, Ifayet Mayo and Mardi Reymann from the CVD Applied Immunology Section and Dr. William D. Picking, Jamie Greenwood, Amy Quick, Kirk Pendleton and Daniel Picking in the Picking laboratory for their assistance and reading of the manuscript. Lastly, we acknowledge Dr. William Blackwelder and Yukun Wu from the CVD Statistics Unit, for guidance in the data analyses. This research was funded by PATH-EVI and, in part, by NIH R01 AI089519 (to MFP and WLP).

Abbreviations

- Ipas

invasion plasmid antigens

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TTSS

type III secretion system

- i.n

intranasal

- LT

heat-labile enterotoxin

- dmLT

double mutant of the heat-labile enterotoxin

- o.g

orogastric

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- ASC

antibody secreting cells

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EU

Elisa Unit

- ELIspot

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot

- MSD

Meso Scale Discovery

- NALT

nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissues

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for the work presented herein.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2197–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreccio C, Prado V, Ojeda A, et al. Epidemiologic patterns of acute diarrhea and endemic Shigella infections in children in a poor periurban setting in Santiago, Chile. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(6):614–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen D, Green MS, Block C, Slepon R, Ofek I. Prospective study of the association between serum antibodies to lipopolysaccharide O antigen and the attack rate of shigellosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(2):386–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.386-389.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenzie R, Walker RI, Nabors GS, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral, inactivated, whole-cell vaccine for Shigella sonnei: preclinical studies and a Phase I trial. Vaccine. 2006 May 1;24(18):3735–45. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotloff KL, Pasetti MF, Barry EM, et al. Deletion in the Shigella enterotoxin genes further attenuates Shigella flexneri 2a bearing guanine auxotrophy in a phase 1 trial of CVD 1204 and CVD 1208. J Infect Dis. 2004 Nov 15;190(10):1745–54. doi: 10.1086/424680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotloff KL, Taylor DN, Sztein MB, et al. Phase I evaluation of delta virG Shigella sonnei live, attenuated, oral vaccine strain WRSS1 in healthy adults. Infect Immun. 2002 Apr;70(4):2016–21. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2016-2021.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman KM, Arifeen SE, Zaman K, et al. Safety, dose, immunogenicity, and transmissibility of an oral live attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine candidate (SC602) among healthy adults and school children in Matlab, Bangladesh. Vaccine. 2011 Feb 1;29(6):1347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen D, Ashkenazi S, Green M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of investigational Shigella conjugate vaccines in Israeli volunteers. Infect Immun. 1996;64(10):4074–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4074-4077.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passwell JH, Ashkenzi S, Banet-Levi Y, et al. Age-related efficacy of Shigella O-specific polysaccharide conjugates in 1–4-year-old Israeli children. Vaccine. 2010 Mar 2;28(10):2231–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oaks EV, Turbyfill KR. Development and evaluation of a Shigella flexneri 2a and S sonnei bivalent invasin complex (Invaplex) vaccine. Vaccine. 2006 Mar 20;24(13):2290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riddle MS, Kaminski RW, Williams C, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an intranasal Shigella flexneri 2a Invaplex 50 vaccine. Vaccine. 2011 Sep 16;29(40):7009–19. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Barry EM, Pasetti MF, Sztein MB. Clinical trials of Shigella vaccines: two steps forward and one step back on a long, hard road. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007 Jul;5(7):540–53. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venkatesan MM, Ranallo RT. Live-attenuated Shigella vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006 Oct;5(5):669–86. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminski RW, Oaks EV. Inactivated and subunit vaccines to prevent shigellosis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009 Dec;8(12):1693–704. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olive AJ, Kenjale R, Espina M, Moore DS, Picking WL, Picking WD. Bile salts stimulate recruitment of IpaB to the Shigella flexneri surface, where it colocalizes with IpaD at the tip of the type III secretion needle. Infect Immun. 2007 May;75(5):2626–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01599-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberhelman RA, Kopecko DJ, Salazar-Lindo E, et al. Prospective study of systemic and mucosal immune responses in dysenteric patients to specific Shigella invasion plasmid antigens and lipopolysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1991;59(7):2341–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2341-2350.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cam PD, Pal T, Lindberg AA. Immune response against lipopolysaccharide and invasion plasmid-coded antigens of shigellae in Vietnamese and Swedish dysenteric patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1993 Feb;31(2):454–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.454-457.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van de Verg LL, Herrington DA, Boslego J, Lindberg AA, Levine MM. Age-specific prevalence of serum antibodies to the invasion plasmid and lipopolysaccharide antigens of Shigella species in Chilean and North American populations. J Infect Dis. 1992;166(1):158–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cam PD, Achi R, Lindberg AA, Pal T. Antibodies against invasion plasmid coded antigens of shigellae in human colostrum and milk. Acta Microbiol Hung. 1992;39(3–4):263–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotloff KL, Simon JK, Pasetti MF, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of CVD 1208S, a Live, Oral ΔaguaBA Δsen Δset Shigella flexneri 2a Vaccine Grown on Animal-Free Media. Hum Vaccin. 2007 Jul 15;3(6):268–75. doi: 10.4161/hv.4746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon JK, Wahid R, Maciel M, Jr, et al. Antigen-specific B memory cell responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and invasion plasmid antigen (Ipa) B elicited in volunteers vaccinated with live-attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine candidates. Vaccine. 2009 Jan 22;27(4):565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Becerra FJ, Kissmann JM, Diaz-McNair J, et al. Broadly protective Shigella vaccine based on type III secretion apparatus proteins. Infect Immun. 2012 Mar;80(3):1222–31. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06174-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis DJ, Huo Z, Barnett S, et al. Transient facial nerve paralysis (Bell’s palsy) following intranasal delivery of a genetically detoxified mutant of Escherichia coli heat labile toxin. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(9):e6999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mutsch M, Zhou W, Rhodes P, et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell’s palsy in Switzerland. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 26;350(9):896–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summerton NA, Welch RW, Bondoc L, et al. Toward the development of a stable, freeze-dried formulation of Helicobacter pylori killed whole cell vaccine adjuvanted with a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin. Vaccine. 2010 Feb 3;28(5):1404–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Espina M, Olive AJ, Kenjale R, et al. IpaD localizes to the tip of the type III secretion system needle of Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 2006 Aug;74(8):4391–400. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00440-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mach H, Middaugh CR, Lewis RV. Statistical determination of the average values of the extinction coefficients of tryptophan and tyrosine in native proteins. Anal Biochem. 1992 Jan;200(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90279-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramirez K, Ditamo Y, Rodriguez L, et al. Neonatal mucosal immunization with a non-living, non-genetically modified Lactococcus lactis vaccine carrier induces systemic and local Th1-type immunity and protects against lethal bacterial infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2010 Mar;3(2):159–71. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khader SA, Gaffen SL, Kolls JK. Th17 cells at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity against infectious diseases at the mucosa. Mucosal Immunol. 2009 Sep;2(5):403–11. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boullier S, Tanguy M, Kadaoui KA, et al. Secretory IgA-mediated neutralization of Shigella flexneri prevents intestinal tissue destruction by down-regulating inflammatory circuits. J Immunol. 2009 Nov 1;183(9):5879–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conway MA, Madrigal-Estebas L, McClean S, Brayden DJ, Mills KH. Protection against Bordetella pertussis infection following parenteral or oral immunization with antigens entrapped in biodegradable particles: effect of formulation and route of immunization on induction of Th1 and Th2 cells. Vaccine. 2001 Feb 28;19(15–16):1940–50. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00433-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moldoveanu Z, Clements ML, Prince SJ, Murphy BR, Mestecky J. Human immune responses to influenza virus vaccines administered by systemic or mucosal routes. Vaccine. 1995 Aug;13(11):1006–12. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00016-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qadri F, Bhuiyan TR, Sack DA, Svennerholm AM. Immune responses and protection in children in developing countries induced by oral vaccines. Vaccine. 2012 Nov 12;31(3):452–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strobel S, Mowat AM. Oral tolerance and allergic responses to food proteins. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Jun;6(3):207–13. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000225162.98391.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasetti MF, Simon JK, Sztein MB, Levine MM. Immunology of gut mucosal vaccines. Immunol Rev. 2011 Jan;239(1):125–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu YJ, Yadav P, Clements JD, et al. Options for inactivation, adjuvant, and route of topical administration of a killed, unencapsulated pneumococcal whole-cell vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010 Jun;17(6):1005–12. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00036-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Remot A, Roux X, Dubuquoy C, et al. Nucleoprotein nanostructures combined with adjuvants adapted to the neonatal immune context: a candidate mucosal RSV vaccine. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e37722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Way SS, Borczuk AC, Goldberg MB. Thymic independence of adaptive immunity to the intracellular pathogen Shigella flexneri serotype 2a. Infect Immun. 1999 Aug;67(8):3970–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3970-3979.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kotloff KL, Losonsky GA, Nataro JP, et al. Evaluation of the safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy in healthy adults of four doses of live oral hybrid Escherichia coli- Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine strain EcSf2a-2. Vaccine. 1995;13(5):495–502. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00011-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robbins JB, Chu C, Schneerson R. Hypothesis for vaccine development: protective immunity to enteric diseases caused by nontyphoidal salmonellae and shigellae may be conferred by serum IgG antibodies to the O-specific polysaccharide of their lipopolysaccharides. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15(2):346–61. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klimpel GR, Niesel DW, Klimpel KD. Natural cytotoxic effector cell activity against Shigella flexneri- infected HeLa cells. J Immunol. 1986;136(3):1081–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raqib R, Ljungdahl A, Lindberg AA, Andersson U, Andersson J. Local entrapment of interferon gamma in the recovery from Shigella dysenteriae type 1 infection. Gut. 1996;38(3):328–36. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raqib R, Gustafsson A, Andersson J, Bakhiet M. A systemic downregulation of gamma interferon production is associated with acute shigellosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65(12):5338–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5338-5341.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coccia M, Harrison OJ, Schiering C, et al. IL-1beta mediates chronic intestinal inflammation by promoting the accumulation of IL-17A secreting innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2012 Aug 27;209(9):1595–609. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sellge G, Magalhaes JG, Konradt C, et al. Th17 cells are the dominant T cell subtype primed by Shigella flexneri mediating protective immunity. J Immunol. 2010 Feb 15;184(4):2076–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sansonetti PJ. Shigella flexneri: from in vitro invasion of epithelial cells to infection of the intestinal barrier. Biochem Soc Trans. 1994;22(2):295–8. doi: 10.1042/bst0220295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.