Abstract

This study of 2,163 adult chronic, non-cancer-pain, long-term opioid therapy patients examines the relationship of depression to functional disability by measuring average pain interference, activity limitation days, and employment status. Those with more depression symptoms compared to those with fewer were more likely to have worse disability on all 3 measures (average pain interference score > 5, OR = 536, p < .0001; activity limitation days ≥ 30, OR = 4.05, p < .0001; unemployed due to health reasons, OR = 4.06, p < .0001). Depression might play a crucial role in the lives of these patients; identifying and treating depression symptoms in chronic pain patients should be a priority.

Keywords: activities of daily living, chronic pain, depression, disability, disability and employment, functional disability, opioids, pain interference

Although several million Americans receive long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain (Parsells Kelly et al., 2008), little is known about long-term outcomes for these patients, particularly their functional status. This is of particular concern because the use of opioid medications has increased dramatically in the past few decades: Between 1980 and 2000, the percentage of musculoskeletal pain patients in the United States who were prescribed opioids doubled (from 8% to 16%; Caudill-Slosberg, Schwartz, & Woloshin, 2004). This marked increase in opioid prescribing has occurred without a full understanding of its impact on the day-to-day functioning of patients. In addition to pain control, improved functioning is an important stated goal of opioid treatment. In a review article, Ballantyne and Mao (2003) found that, although the literature showed the analgesic efficacy of long-term opioids, the evidence for improved functioning was mixed. Moreover, the literature on the relationships between important individual characteristics such as depression, functional disability, and employment measures among patients on long-term opioid therapy is sparse. In this article we examine the relationship of depression (based on the Public Health Questionnaire) to functional disability and employment measures among patients with chronic, noncancer pain, who are prescribed long-term opiate therapy within two large, integrated health delivery systems. For the purposes of this article, functional disability is defined as a composite of a patient’s average pain interference with his or her usual activities, number of days during which activities were limited, and whether he or she was unable to work due to health reasons. Chronic noncancer pain is defined as pain episodes lasting at least 90 days, and long-term opioid episodes were classified as at least 10 dispensings, a 120+ day supply, or both (Von Korff &Weisner, 2008).

BACKGROUND

Chronic pain is common among those with major depression and vice versa; thus it is not surprising that in the United States, opioid use for chronic pain is more prevalent among patients with mood disorders than those without (Bair, Robinson, Katon, & Kroenke, 2003; Braden et al., 2009; Sullivan & Ferrell, 2005; Weisner et al., 2009). Braden et al. (2009) found that patients with depression, compared to those without, had long-term opioid use rates three times higher and higher average daily opioid doses and greater days’ supply.

Several recent studies suggest a relationship between depression and functional outcomes. A nationally representative survey found a higher prevalence of functional disability in patients with chronic medical conditions and comorbid major depression than in individuals with either only a chronic medical condition or major depression, suggesting a synergistic effect of depression and chronic conditions on functional outcomes (Schmitz, Wang, Malla, & Lesage, 2007). A study of outcomes among stroke patients assessed the role of psychological disorders in functional outcomes and found a strong association between the presence of psychological symptoms and functional disability that was not explained by age, sex, or initial disability after stroke (West, Hill, Hewison, Knapp, & House, 2010). Research suggests that interference with activities of daily living, number of days of pain, and number of pain sites all predict depression severity (Bair et al., 2003). Pain beliefs are partial mediators of the relationship between pain and disability, but depression is also a significant variable in explaining functional limitations among chronic pain patients (Alcantara et al., 2010); 41% of chronic pain patients with major depression experience disabling chronic pain compared to 10% of chronic pain patients without major depression (Arnow et al., 2006). However, other studies have not confirmed a strong relationship between psychological factors and pain-related disability (Schiphorst Preuper et al., 2008).

The literature shows that employment status is an important indicator of pain-related disability, and that lower employment rates among chronic pain patients are associated with higher levels of pain ratings and depression symptoms (Dolce, Crocker, & Doleys, 1986). Mental health conditions also have an important relationship to employment status. Chronic pain patients with mental disorders had higher rates of functional interference from pain, and were more likely to be unable to work due to their health than those without mental disorders. A significant interaction was found between having a mental disorder and a chronic pain condition on the outcome of not working in the past year and number of days of work missed per month because of health (Braden, Zhang, Zimmerman, & Sullivan, 2008). However, few studies have examined functional disability and employment outcomes among patients on long-term opioid therapy, even though returning patients to their regular activities is a major reason for prescribing long-term opioid therapy (Stein, Reinecke, & Sorgatz, 2010).

Self-reported functional limitations and mental health are important factors in explaining work status (Kuijer et al., 2006). Mood disorders have been associated with worse employment outcomes, including not working in the last week and an increase in reported disability or bed days (el-Guebaly et al., 2007) and work impairment (Kessler, Greenberg, Mickelson, Meneades, & Wang, 2001). A population-based cohort study in Norway found that depression is a strong predictor of disability pension awards (Mykletun et al., 2006), and another study found that depression is predictive of persistent disability among patients with low back pain (Crook, Milner, Schultz, & Stringer, 2002). Among chronic low-back pain patients, those who are not working report lower levels of physical and mental health, more limitations in activities of daily living, and more depressive symptoms, suggesting a multidimensional relationship among work status, mental health, and functional limitations. In a study of chronic pain patients, level of depression and patient age were most predictive of posttreatment work status, suggesting that emotional distress might be the most important predictor of employment status following chronic pain treatment (Vowles, Gross, & Sorrell, 2004). Chronic pain patients not working due to health reasons or able to work but currently unemployed have higher disability scores, even when controlling for other confounding variables (Moffett, Underwood, & Gardiner, 2009). Further, high opioid use has been significantly related to lower levels of return to work and work retention and higher rates of disability income (Kidner, Mayer, & Gatchel, 2009).

Research is needed to adequately understand the relationship between long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain and functional status among vulnerable patient populations. This article contributes to the literature by examining a chronic pain population in a managed care health plan, a major organizational form for health care delivery (Selby et al., 2005). The reciprocal relationships between pain and depression are complex, presenting real clinical challenges for improving functional capacity. This study aims to increase our understanding of these relationships to inform appropriate pain care treatment for such patients. After controlling for patient characteristics, we hypothesized that those patients with a high level of depression symptoms would have worse functional disabilities and would be more likely to be unable to work than patients without a high level of depression symptoms.

METHOD

Study Sites

The Consortium to Study Opioid Risks and Trends (CONSORT) is a study developed to improve understanding of long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain among adults in the Group Health Cooperative (GHC) in the state of Washington, and Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC; Von Korff et al., 2008). Jointly KPNC and GHC serve about 4 million people (Saunders, Davis, & Stergachis, 2005; Selby et al., 2005). Both sites maintain their own pharmacy and medical encounter data, including services provided directly by the health plan and services provided by others charged to the health plan.

Sample and Procedures

Eligible individuals were chronic, noncancer pain patients at GHC and KPNC, between the ages of 21 and 80, who were receiving long-term opioid therapy. Eligibility was determined using automated pharmacy and membership data: Potential participants filled at least 10 prescriptions or received at least 120 days’ supply in a 1-year period prior to the sample selection date, with at least 90 days between the first and last opioid dispensing in that year. This threshold has been shown to predict high probability of sustained and frequent use of opioids (Von Korff et al., 2005). The study required that patients have a prescription whose days’ supply extended beyond the date of sampling to ensure that they were still current users. Ninety percent of members get their prescriptions from KPNC and GHC pharmacies (Saunders et al., 2005; Selby et al., 2005).

Respondents were selected using stratified random sampling, with an equal number from three opioid dosage strata: Level 1 (1–49 milligrams per day MED), Level 2 (50–99 milligrams per day MED), and Level 3 (100+ milligrams per day MED). The majority of long-term opioid users receive relatively low dosage levels, thus this approach oversampled the higher dosage recipients to ensure adequate numbers for analyses. The observations were then weighted by the inverse probability of selection within strata so they would be representative of the population of long-term opioid users from which they were drawn.

Eligible individuals were sent invitational letters explaining the study, including a notice that they would be called in 3 weeks, and a toll-free number to contact the study coordinators for more information or to decline participation. A $5 gift card was included as a preincentive. Patients were then telephoned by study interviewers who further explained the study requirements, obtained verbal consent, and scheduled the 1-hour computer-assisted telephone interview. Participants were compensated $50 at KPNC and $20 at GHC for their interviews. Interviewers were trained in the use of a fully structured questionnaire based on a common set of interview specifications and field work procedures. A total of 2,163 participants completed the interview (1,191 at GHC and 972 at KPNC), for an overall response rate of 60% (57% at GHC and 65% at KPNC). The response rate difference between sites was presumably due to lower incentive payments at GHC. All study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards for both health plans.

Measures

Individual characteristics

Demographics

The instrument included items on age, gender, and ethnicity (White, other). Education level was dichotomized based on college education (no college, at least some college).

Depression

Patients were assessed using an 8-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), a widely used, validated, self-report measure of depressive symptoms (Dobscha et al., 2009). Based on recommended cut points, participants with scores greater than or equal to 10 were classified as having high depression symptoms (Kroenke et al., 2009).

Dependent variables

Functional disability measures

We were interested in three discrete functional disability measures: average pain interference score, activity limitation days, and employment status.

Average pain interference

The average pain interference score is composed of three activity interference rating items as based on prior work (Von Korff, Ormel, Keefe, & Dworkin, 1992): (a) daily activities; (b) recreational, social, and family activities; and (c) work, including housework. Patients were asked to recall pain interference with activities of daily living over the last 3 months and rate it on a scale of 0 (no interference) to 10 (unable to carry on any activities). We averaged the three interference rating variables and dichotomized the measure using a score greater than 5 to indicate a functional disability due to pain interference (median score was 6).

Activity limitation days

The activity limitation days variable asked participants how many days in the last 3 months they were kept from doing their usual activities. A cut point of 1 month (30 days) or greater was chosen to indicate a functional disability outcome due to days of limited activity; the average was 37 days.

Employment status

The final functional disability measure was employment status. Unemployed status is defined as an individual being permanently or temporarily unable to work due to health reasons. Employed status is defined as an individual being able to work full-time or part-time; retired individuals, students, homemakers, and those unemployed but currently looking for work were not included. We excluded these individuals to avoid confounding of the relationship between disability and employment status. Employment is often considered a surrogate, but not interchangeable, measure for functional limitation, and an effective correlate with a longitudinal, rather than instantaneous, measure of pain (Dionne et al., 1999).

Statistical Analysis

Methods for stratified random samples were used to obtain unbiased estimates, namely SAS PROC SURVEYFREQ and SAS PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC. Chi-square analyses were used to compare the difference between the disability measures and the covariates. We estimated and tested weighted logistic regression models for each of the three disability outcomes with the weighted survey logistic procedure in SAS, version 9.1 (SAS, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

The sample was 37% male, 90% White, 60% with at least some college education, and the average age was 55. Of the sample, 41% had a score of 10 or higher on the depression scale indicating a high level of depression symptoms; 60% had an average pain interference score greater than 5, 49% had at least 30 activity limitation days in the past 3 months, 35% were unable to work due to disability, and 70% had at least one of the three significant functional disabilities.

Bivariate Results

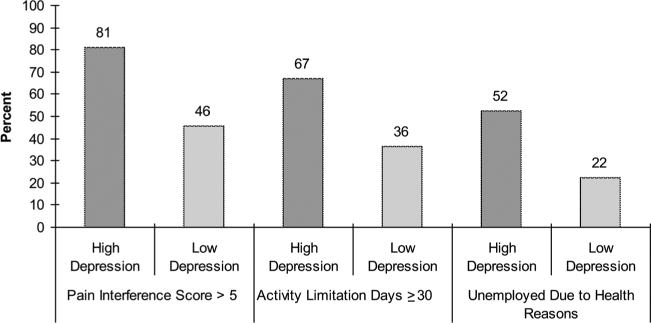

Figure 1 presents the percentage of the sample with a significant functional disability by depression level for the three functional disability measures. The percentages of individuals with disabilities were significantly higher among those with high depression symptoms. Comparing those with high depression symptoms to those with low depression symptoms, 81% of the high group had an average pain interference score greater than 5 versus 46% of the low group; 67% of the high group had an activity limitation days score of 30 or more versus 37% of the low group; and 52% of the high group were unable to work versus 22% of the low group (p values all < .0001).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage With Functional Disability by Depression Level.

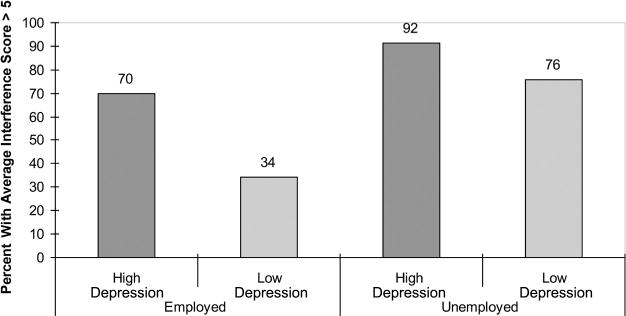

The percentage of the sample with an average interference score greater than 5 by employment status and depression level is presented in Figure 2. For individuals who were employed, 70% of the high depression group had an average interference score greater than 5, versus 34% of the low group (p < .0001). For individuals unable to work due to health reasons, 92% of those with high depression had an average interference score greater than 5, versus 76% of those with low depression (p = .0002).

FIGURE 2.

Average Interference Score Disability by Employment Status and Depression Level.

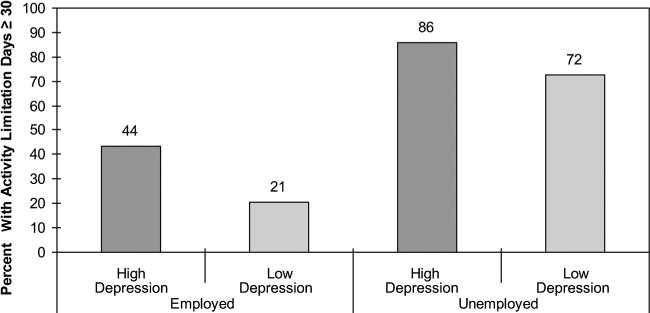

Figure 3 presents the percentage with activity limitation days greater than or equal to 30 days by employment status and depression level. For individuals who were employed, 44% of those with high depression had at least 30 activity limitation days, versus 21% of the low group (p < .0001). For individuals unable to work, 86% of the high depression group had activity limitation days greater than or equal to 30 days, versus 72% of the low depression group (p = .0043).

FIGURE 3.

Activity Limitation Days Disability by Employment Status and Depression Level.

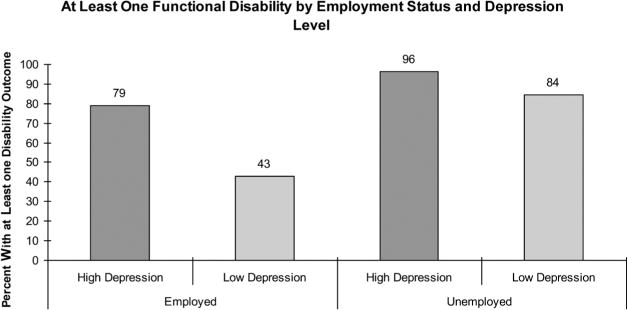

The percentage of the sample with at least one disability by employment status and depression is presented in Figure 4. Only two of the three functional disability measures were used (average interference score > 5, activity limitation days > 30) because employment status is already in the model. Of those employed, 79% of the high depression group had at least one functional disability, versus 43% of the low group (p < .0001). For individuals unable to work, 96% of the high depression group had at least one functional disability, versus 84% of the low group (p = .0002).

FIGURE 4.

At Least One Functional Disability by Employment Status and Depression Level.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Models of Functional Disability

Table 1 presents three logistic regression models for each of the three functional disability measures: average pain interference score (> 5), activity limitation days (> 30), and employment status (unable to work due to health reasons). For all three outcomes, men had lower odds of having a functional disability compared to women (average pain interference score, OR = 0.47, p < .0001; activity limitation days, OR = 0.61, p = .0048; employment status, OR = 0.63, p = .0058). For every year increase in age, the odds that an individual has 30 or more days of limited activity increased by 2% (p = .0108) and the odds that he or she is unable to work due to health reasons increased by 4% (p < .0001). Participants with at least some college education had 45% lower odds of being unemployed due to health reasons compared to those with lower levels of education (p = .0004). Individuals with more depression symptoms (high depression) had higher odds of having a worse functional disability as gauged by all three measures (average pain interference score, OR = 5.36, p < .0001; activity limitation days, OR = 4.05, p < .0001; employment status, OR = 4.06, p < .0001).

TABLE 1.

Multivariate Logistic Regression for Functional Disabilities

| Average Pain Interference Score

|

Activity Limitation Days

|

Employment Status

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio of disability (score > 5) | 95% confidence intervals | Odds ratio of disability (days ≥ 30) | 95% confidence intervals | Odds ratio of disability (unemployed due to health reasons) | 95% confidence intervals | |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.47*** | [0.34, 0.66] | 0.61* | [0.43, 0.86] | 0.63* | [0.45, 0.88] |

| Age | 1.01 | [0.99, 1.03] | 1.02* | [1.01, 1.04] | 1.04*** | [1.01, 1.05] |

| Ethnicity | 0.67 | [0.38, 1.17] | 1.21 | [0.70, 2.08] | 0.78 | [0.46, 1.35] |

| (White vs. non-White) | ||||||

| Education level | 0.72 | [0.51, 1.01] | 0.87 | [0.62, 1.22] | 0.55** | [0.40, 0.77] |

| (some college vs. no college) | ||||||

| Depression | 5.36*** | [3.84, 7.50] | 4.05*** | [2.91, 5.64] | 4.06*** | [2.93, 5.63] |

| symptoms (high vs. low) | ||||||

Note. N = 1,526.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to the literature by examining the roles of depression and important demographic characteristics in functional disability and employment status among chronic pain patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. Although there is no consensus on whether the primary objective of prescribing long-term opioids is pain relief, functional improvement, quality of life, or patient satisfaction, helping patients to return to their regular activities is certainly a major motivation for prescribing long-term opioid therapy (Stein et al., 2010), and few studies have examined functional disability and employment among these patients. Further research is needed to improve standards for the use of opioids in pain care to improve these functional measures, and this study adds to the literature in this area (Ballantyne & Mao, 2003; Franklin et al., 2005).

We add new information to the mixed evidence in the literature on how the pain-depression relationship influences functional disabilities, and our findings are consistent with those in the literature suggesting a strong relationship between depression and functional disabilities in chronic pain patients. While some earlier studies found a weak relationship between pain severity and depression (explaining only 9.0% of the variance with maximum correlations of 0.30) (Angst, Verra, Lehmann, Aeschlimann, & Angst, 2008), we found depression to be strongly associated with functional disabilities; in the analyses, high depression severity was associated with a higher level of disability. It is possible that functional disability operates differently than self-reported pain severity, although the two variables are likely strongly correlated. Patients might report high levels of pain severity while exhibiting a low level of functional disability, whereas others might report low levels of pain severity yet exhibit a high level of functional disability. This complex relationship between the self-reported experience of pain and functionality should be explored in future studies to better guide clinical decision making regarding long-term use of opioid medication and complementary treatments such as physical therapy and talk therapy. It is also important to acknowledge that our findings apply to a limited, medical approach to the concept of disability.

The relationship between depression and pain is complex and bidirectional, with each able to exacerbate the other condition (Arnow et al., 2006; Bair et al., 2003). Our findings point to the potential benefits of both targeted screening of chronic pain patients for depression, and a more integrated model of treatment for chronic pain (Geisser, Robinson, Miller, & Bade, 2003), an approach supported by the literature. Dobscha and colleagues (2009) found evidence for a collaborative treatment plan to improve chronic pain outcomes in a random assignment study that stratified by proportion of patients receiving opioids. In their cluster randomized trial, patients receiving (a) collaborative integrated treatment intervention including a clinician education program; (b) patient assessment, education, and activation; (c) symptom monitoring; (d) feedback and recommendations to clinicians; and (e) specialty care showed improvements in both functional disability and pain severity. Comprehensive collaborative interventions can improve outcomes for chronic conditions by optimizing patient and clinician contact through education and activation while offering care management and clinician feedback. For patients with baseline depression, there were also improvements in depression severity, along with disability and pain severity (Dobscha et al., 2009). Lin et al. (2003) found that comprehensive, integrated depression care reduced depression symptoms, decreased pain, and improved functional status in a population of older adults with arthritis and comorbid depression.

Similar to other literature that has noted the strong relationship between depression and function disability among those with chronic pain (Dobscha et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2003; West et al., 2010), we found that among those unable to work with high depression symptoms, more than 9 out of 10 (92%) reported a high level of interference with daily activities, suggesting very high disability among this group. Even among the individuals with a low level of depression symptoms who were unable to work, more than three quarters (76%) reported a high level of interference with daily activities. An overwhelming majority of the study population reported at least one disability outcome. Among those unable to work with high depression symptoms, nearly every individual reported at least one disability (96%), and among those with low depression symptoms, about 84% reported at least one disability.

These findings underscore the crucial role that depression could play in the lives of patients on long-term opioid therapy, and the importance of identifying and treating depressive symptoms in these patients. Further, individuals with a high level of depression symptoms had five times the odds of having an average pain interference score greater than 5, more than three times the odds of having 30 or more activity limitation days, and more than four times the odds of being unable to work compared to those with low depression symptoms. These findings suggest that depression plays a role in influencing these patients’ ability to carry out normal activities on a daily basis, including the ability to participate in the workforce.

To better understand the unique needs of chronic pain patients using opioids long term, further research should consider types of medication and types of pain, and how to best combine pharmaceutical treatment and social support to improve functional status. The cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow us to pinpoint the onset and chronology of various symptoms or establish causal relationships. Specifically, it is difficult to determine whether the onset of depression worsened functional disabilities, or whether greater functional disability contributes to more severe depression symptoms. Future studies could be designed for a prospective, longitudinal comparison of chronic pain patients on long-term opioid therapy with and without a history of depression. Such research could track patient measures over the course of several years. By gathering data about patients’ depression symptoms and employment status before the start of opioid therapy, researchers would be better able to determine causal inference in relation to their functional disabilities and to examine the relationship between pain perception and functional status.

Study Limitations

Limitations of this study include the use of a privately insured population, which might not be generalizable to other health plans or public populations. KPNC and GHC represent populations with regular access to health services and thus they might have less severe problems. However, the managed care health plans are an increasingly common form of health care organization. Because of mental health parity and health care reform legislation, in coming years more of the general population will be members of similar health systems, making this study of particular relevance to a rapidly growing population of pain patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. Moreover, depression, chronic pain, and functionality are important issues outside of integrated systems, with implications for the larger health care system as well. A limitation to the employment measure is that there might be a bidirectional relationship between depression symptoms and being unable to work.

Although acknowledging these limitations, our findings strengthen the evidence for a strong relationship between depression and functional disability in chronic pain patients on long-term opioid therapy, and suggest the need for screening and continued monitoring of depression symptoms among these patients. Integrated models of depression and pain treatment have the potential for considerable benefit for this population, and deserve further study. Long-term opioid use might not be producing significant improvements in functional status among this patient population, with an overwhelming majority indicating very high levels of functional disabilities.

References

- Alcantara MA, Sampaio RF, Pereira LS, Fonseca ST, Silva FC, Kirkwood RN, Mancini MC. Disability associated with pain—A clinical approximation of the mediating effect of belief and attitudes. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2010;26(7):459–467. doi: 10.3109/09593980903580233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst F, Verra ML, Lehmann S, Aeschlimann A, Angst J. Refined insights into the pain–depression association in chronic pain patients. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(9):808–816. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31817bcc5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow B, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, Lee J, Constantino MJ, Fireman B, Hayward C. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68(2):262–268. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: A literature review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(20):2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(20):1943–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden JB, Sullivan MD, Ray GT, Saunders K, Merrill J, Silverberg MJ, Von Korff M. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain among persons with a history of depression. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden JB, Zhang L, Zimmerman FJ, Sullivan MD. Employment outcomes of persons with a mental disorder and comorbid chronic pain. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(8):878–885. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.8.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in the US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook J, Milner R, Schultz IZ, Stringer B. Determinants of occupational disability following a low back injury: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2002;12(4):277–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1020278708861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne CE, Von Korff M, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA, Barlow WE, Checkoway H. A comparison of pain, functional limitations, and work status indices as outcome measures in back pain research. Spine. 1999;24(22):2339–2345. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Leibowitz RQ, Doak MN, Gerrity MS. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolce JJ, Crocker MF, Doleys DM. Prediction of outcome among chronic pain patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24(3):313–319. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Guebaly N, Currie S, Williams J, Wang J, Beck CA, Maxwell C, Patten SB. Association of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders with occupational status and disability in a community sample. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):659–667. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin GM, Mai J, Wickizer T, Turner JA, Fulton-Kehoe D, Grant L. Opioid dosing trends and mortality in Washington State workers’ compensation, 1996–2002. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2005;48(2):91–99. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisser ME, Robinson ME, Miller QL, Bade SM. Psychosocial factors and functional capacity evaluation among persons with chronic pain. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2003;13(4):259–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1026272721813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Greenberg PE, Mickelson KD, Meneades LM, Wang PS. The effects of chronic medical conditions on work loss and work cutback. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2001;43(3):218–225. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidner CL, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. Higher opioid doses predict poorer functional outcome in patients with chronic disabling occupational musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2009;91(4):919–927. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;114(1–3):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijer W, Brouwer S, Preuper HR, Groothoff JW, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU. Work status and chronic low back pain: Exploring the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2006;28(6):379–388. doi: 10.1080/09638280500287635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Tang L, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K, Unutzer J. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(18):2428–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett JA, Underwood MR, Gardiner ED. Socioeconomic status predicts functional disability in patients participating in a back pain trial. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009;31(10):783–790. doi: 10.1080/09638280802309327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykletun A, Overland S, Dahl AA, Krokstad S, Bjerkeset O, Glozier N, Prince M. A population-based cohort study of the effect of common mental disorders on disability pension awards. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1412–1418. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsells Kelly J, Cook SF, Kaufman DW, Anderson T, Rosenberg L, Mitchell AA. Prevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult population. Pain. 2008;138(3):507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders KW, Davis RL, Stergachis A. Group health cooperative. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 4. New York, NY: Wiley; 2005. pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Schiphorst Preuper HR, Reneman MF, Boonstra AM, Dijkstra PU, Versteegen GJ, Geertzen JH, Brouwer S. Relationship between psychological factors and performance-based and self-reported disability in chronic low back pain. European Spine Journal. 2008;17(11):1448–1456. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Wang J, Malla A, Lesage A. Joint effect of depression and chronic conditions on disability: Results from a population-based study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(4):332–338. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31804259e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby JV, Smith DH, Johnson ES, Raebel MA, Friedman GD, McFarland BH. Kaiser Permanente medical care program. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 4. New York, NY: Wiley; 2005. pp. 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Stein C, Reinecke H, Sorgatz H. Opioid use in chronic noncancer pain: Guidelines revisited. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2010;23(5):598–601. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32833c57a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Ferrell B. Ethical challenges in the management of chronic nonmalignant pain: Negotiating through the cloud of doubt. Journal of Pain. 2005;6(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Crane P, Lane M, Miglioretti DL, Simon G, Saunders K, Kessler R. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain. 2005;113(3):331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, Boudreau D, Campbell C, Merrill J, Weisner C. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(6):521–527. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318169d03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Weisner C. Long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain, initial CONSORT study results; Paper presented at HMO Research Network Conference; Minneapolis, MN. 2008. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Vowles KE, Gross RT, Sorrell JT. Predicting work status following interdisciplinary treatment for chronic pain. European Journal of Pain. 2004;8(4):351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner CM, Campbell CI, Ray GT, Saunders K, Merrill JO, Banta-Green C, Von Korff M. Trends in prescribed opioid therapy for non-cancer pain for individuals with prior substance use disorders. Pain. 2009;145(3):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Hill K, Hewison J, Knapp P, House A. Psychological disorders after stroke are an important influence on functional outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2010;41(8):1723–1727. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]