Abstract

Background

The oestrogen receptor (ER) co-activator amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1) has been suggested as a treatment predictive and prognostic marker in breast cancer. Studies have however not been unanimous.

Patients and methods

AIB1 protein expression was analysed by immunohistochemistry on tissue micro-arrays with tumour samples from 910 postmenopausal women randomised to tamoxifen treatment or no adjuvant treatment. Associations between AIB1 expression, clinical outcome in the two arms and other clinicopathological variables were examined.

Results

In patients with ER-positive breast cancer expressing low tumour levels of AIB1 (<75%), we found no significant difference in recurrence-free survival (RFS) or breast cancer-specific survival (BCS) between tamoxifen treated and untreated patients. In patients with high AIB1 expression (>75%), there was a significant decrease in recurrence rate (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.26–0.61, P < 0.001) and breast cancer mortality rate (HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.21–0.69, P = 0.0015) with tamoxifen treatment. In the untreated arm, we found high expression of AIB1 to be significantly associated with lower RFS (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.20–2.53, P = 0.0038).

Conclusion

Our results suggest that high AIB1 is a predictive marker of good response to tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal women and a prognostic marker of decreased RFS in systemically untreated patients.

Keywords: AIB1, breast cancer, HER2, prognosis, SRC-3, treatment prediction

introduction

About two-thirds of all breast cancers are oestrogen receptor (ER) positive and proliferate in response to oestrogenic stimulation [1]. The anti-oestrogen tamoxifen has been the first-line endocrine therapy for both pre- and post-menopausal women for many years. However, some tumours are de novo resistant, and a substantial fraction will eventually develop resistance to tamoxifen over time [2].

Tamoxifen competes with endogenous oestrogens for binding to the ER, but the effect of the binding is dependent on the recruitment of co-activators and co-repressors that modulate ER transcriptional activity [3]. Oestrogen binding normally favours the recruitment of co-activators, while tamoxifen binding leads to recruitment of co-repressors and inhibited transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation [2]. Thus, it has been hypothesised that tamoxifen resistance is associated with an increase in the amount of co-activators, leading to an agonistic activity of ER-bound tamoxifen [4].

Amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1) has been suggested in the development of breast cancer and tamoxifen resistance. AIB1 is a member of the SRC family of nuclear receptor co-activators. The gene is amplified in 10% and the mRNA was found over-expressed in 64% of breast cancers [5]. AIB1 interacts with the ER and enhances oestrogen-dependent gene transcription [6]. In addition, AIB1 interacts with several signalling molecules mediating proliferation, survival and migration of cells, including human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) [7]. Over-expression of AIB1 in breast cancer cell lines enhances both oestrogen-stimulated and hormone-independent cell proliferation and renders the cells resistant to anti-oestrogens [8]. In mouse models, AIB1 has been shown to be important for both normal mammary development and mammary tumour formation [9, 10].

Some previous studies have shown that high expression of AIB1 is associated with shorter survival, although others have found no such association or an association to increased survival [11–16]. Our aim was to investigate the role of AIB1 as a tamoxifen treatment predictive and prognostic marker by assessing the expression of AIB1 in tumours from women randomised to either adjuvant tamoxifen or no adjuvant therapy.

materials and methods

patients

A cohort of 1780 postmenopausal women with breast cancer was randomised between adjuvant tamoxifen and no adjuvant therapy during 1976 through 1990. The patients had a tumour size < 30 mm and negative lymph node status (N0). The trial has been described in detail previously [17]. For the present study, it was possible to retrieve archived tumour tissue from 910 patients. The clinicopathological characteristics in this subset were similar to those in the complete cohort. The tumours were graded retrospectively according to the Nottingham system (NHG) by one pathologist blinded to clinical outcome. The mean follow-up period was 17 years. The study was approved by the local ethical committee at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

breast cancer tissue micro-array and immunohistochemistry for AIB1

Tissue micro-arrays (TMA) were constructed as previously described [18]. TMA sections were deparaffinised in xylene and rehydrated in a series of ethanol of decreasing concentration. Antigen retrieval was carried out by cooking in Tris-EDTA, pH 9. A mouse monoclonal antibody recognising the amino acids 376–389 was used as the primary antibody in a 1 : 100 dilution (clone 34, BD BioScience, San José, CA) and incubation was done over night at 4°C. This antibody has been used previously [15], and it has been shown to be specific for AIB1 [19]. Further validation of the antibody is presented in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. For detection, the secondary antibody DAKO Envision+ System-HRP Labelled Polymer, was used (Dako North America, Inc., Carpinteria, CA).

staining evaluation

AIB1 immunostaining was evaluated by light microscopy by two independent observers blinded to clinicopathological information. In cases of discrepant scoring, a consensus score was reached after re-evaluation. A proportion score, representing the estimated proportion of stained cell nuclei (0: <1%; 1: 1%–25%; 2: 26%–75%; 3: 76%–100%) and an intensity score (0: no staining; 1: weak staining; 2: moderate staining; 3: strong staining) was assigned. The proportion and intensity scores were added to obtain a total score, ranging from 0 to 6. We considered a proportion score of 3 (>75%) as high frequency and an intensity score of ≥2 as high intensity. A total score of 0–3, 4 and 5–6 were considered as low, intermediate and high expression, respectively, dividing the patients into three groups of approximately equal size.

immunohistochemistry for ER, PgR and HER2

Retrospective immunohistochemical evaluation of the expression of ER and progesterone receptor (PgR) was previously described [18]. Positivity was defined as >25% stained nuclei. High ER expression was defined as ≥90% positive cells. If immunohistochemical data were missing, ER positivity was defined as >0.05 fmol/μg DNA, based on biochemical assays carried out at the time of diagnosis [17]. Immunohistochemical staining for HER2 was carried out and scored (0, 1+, 2+, 3+) as described elsewhere [20].

statistical analysis

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and breast cancer-specific survival (BCS) were chosen as primary end points. Correlation between AIB1 and other clinicopathological factors was evaluated using χ2-test or χ2-test for trend. Survival curves and probabilities of RFS and BCS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox hazard regression analysis. To test for the interaction between AIB1 and treatment effect, a Cox model including AIB1, treatment and the interaction term treatment × AIB1 was carried out. The pattern of the treatment effect of tamoxifen for different AIB1 levels was studied using subpopulation treatment effect pattern plots (STEPP) analysis [21]. The method used was the tailored version with g = 11. All statistical calculations were done with the statistical software STATISTICA 8.0 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK). P-values <0.05 in two-sided tests were considered significant.

results

After excluding TMA cores that were missing or consisting of mainly stroma or non-malignant cells, 814 tumours (89.4%) were evaluated for AIB1 expression. The characteristics of the excluded tumours were similar to the ones included (data not shown). The flow of patients through the study is described in supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online.

AIB1 expression and association with clinicopathological factors

The expression of AIB1 was almost exclusively nuclear and therefore only staining of the nuclei was analysed. Different staining patterns of AIB1 are shown in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. AIB1 expression was found in 89.2% of the tumour samples. High staining frequency was found in 58.6% of the tumours and high staining intensity in 40.2%. When considering the total score, 31.7% were classified as having high expression of AIB1.

High staining frequency was correlated with expression of ER, PgR and HER2. Increasing total score was correlated with high tumour grade, PgR and expression of HER2 (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The association between AIB1 frequency score and ER became stronger when taking into account different levels of ER expression (<25%, 25%–89%, ≥90%) (P < 0.001).

AIB1 as a treatment predictive factor

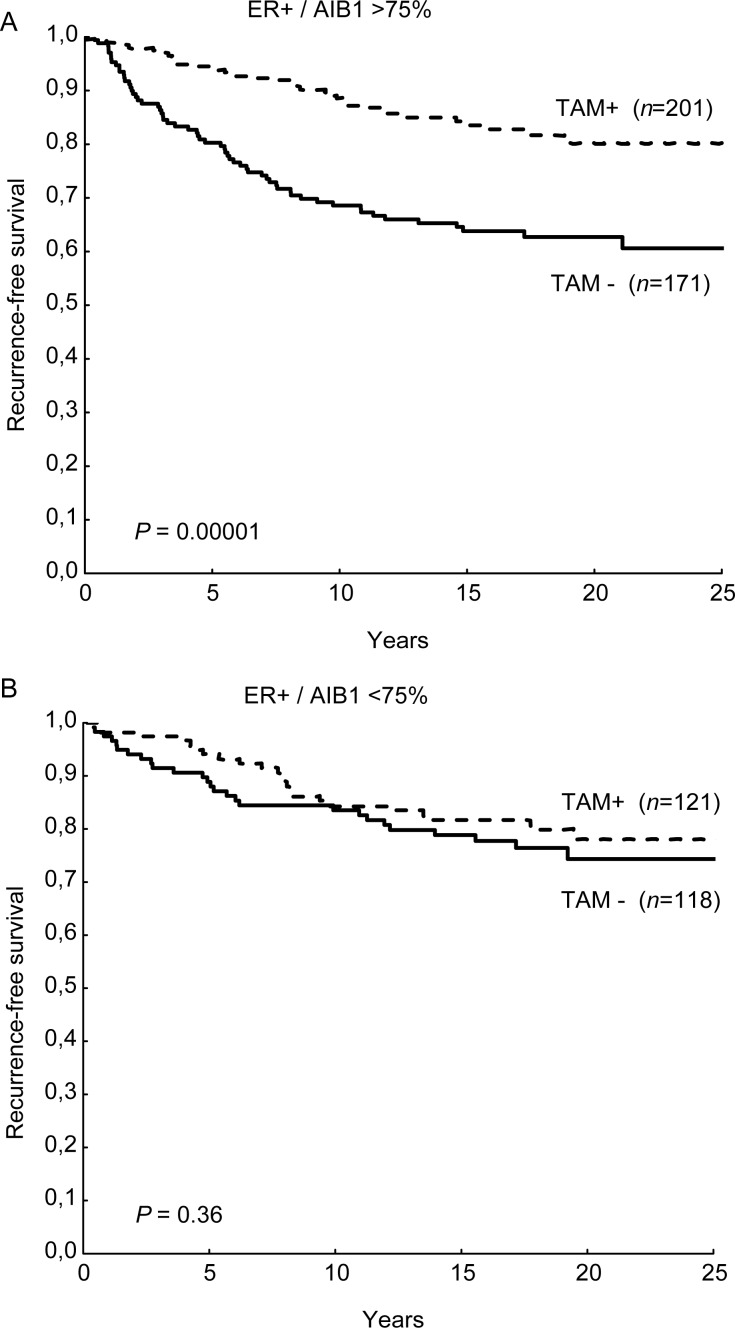

In patients with ER-positive tumours with low AIB1 expression (total score 0–3 or proportion score <3) we found no significant difference in RFS between the group of patients receiving and those not receiving tamoxifen. In the group with intermediate (total score 4) or high AIB1 expression (total score 5–6), there was a significant increase in RFS with tamoxifen treatment. This was also true for patients with high proportion score (Table 1, Figure 1). High AIB1 expression was also associated with good benefit from tamoxifen in terms of BCS (HR = 0.38 95% CI 0.21–0.69 P = 0.0015). A test for interaction between AIB1 and tamoxifen benefit reached borderline significance (P = 0.064). However, when adjusting for tumour size, NHG, PgR and HER2, the interaction was significant (P = 0.023) (Table 1). The intensity score alone was not significantly associated with differences in tamoxifen benefit (data not shown).

Table 1.

Cox regression analysis of recurrence-free survival among patients with ER-positive tumours

| Recurrence-free survival |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen versus no tamoxifen | |||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | aPInteraction | |

| All ER+ | |||

| AIB1 frequency | |||

| AIB1 ≤75% | 0.77 (0.45–1.34) | 0.36 | 0.023 |

| AIB1 >75% | 0.40 (0.26–0.61) | <0.001 | |

| AIB1 total score | |||

| 0–3 | 0.66 (0.36–1.22) | 0.18 | 0.46 |

| 4 | 0.47 (0.26–0.86) | 0.015 | |

| 5–6 | 0.47 (0.28–0.81) | 0.006 | |

| Highly ER+ (≥90%) | |||

| AIB1 frequency | |||

| AIB1 ≤75% | 1.52 (0.57–4.1) | 0.40 | 0.0036 |

| AIB1 >75% | 0.28 (0.15–0.52) | <0.001 | |

| AIB1 total score | |||

| 0–3 | 1.07 (0.35–3.3) | 0.91 | 0.079 |

| 4 | 0.52 (0.22–1.23) | 0.14 | |

| 5–6 | 0.29 (0.13–0.63) | 0.002 | |

Tamoxifen benefit in relation to AIB1 expression.

AIB1 amplified in breast cancer 1.

aAdjusted for tumour size, NHG, PgR and HER2.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of recurrence-free survival (RFS) in tamoxifen-treated and -untreated patients in relation to AIB1 expression; AIB1 >75% (A) and AIB1 ≤75% (B).

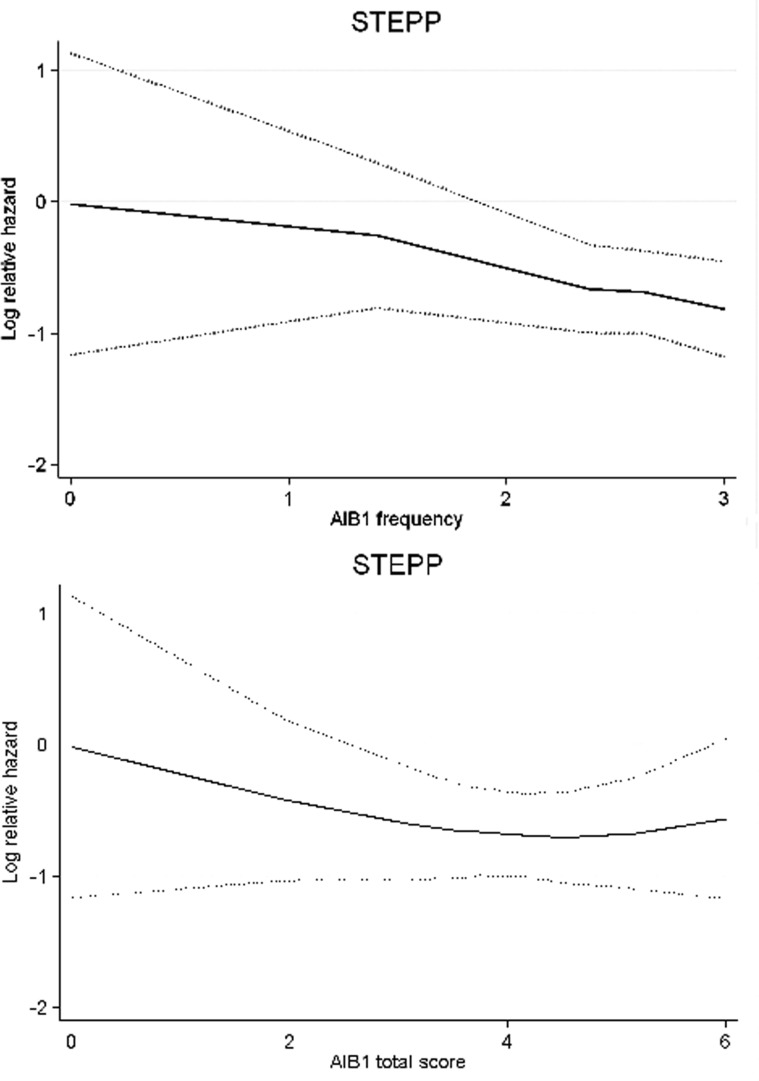

To further illustrate the trends in tamoxifen treatment effect in relation to AIB1 expression, we carried out STEPP analysis (Figure 2). The STEPP curves indicated that the benefit from tamoxifen was absent for low levels of AIB1 and increased with higher levels. As AIB1 and ER expression levels were correlated, we investigated whether AIB1 could predict the efficacy of tamoxifen also when restricting the analysis to patients with highly ER-positive tumours (ER > 90%). The significance of the interaction between AIB1 and treatment benefit was increased for this group of patients, showing that AIB1 is predictive in addition to ER (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Sub-population treatment effect pattern plots (STEPP) showing the effect of tamoxifen for AIB1 frequency and AIB1 total score. Log-relative hazard for recurrence-free survival (RFS) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (dotted lines) is plotted against the mean AIB1 for overlapping subgroups.

AIB1 as a prognostic factor

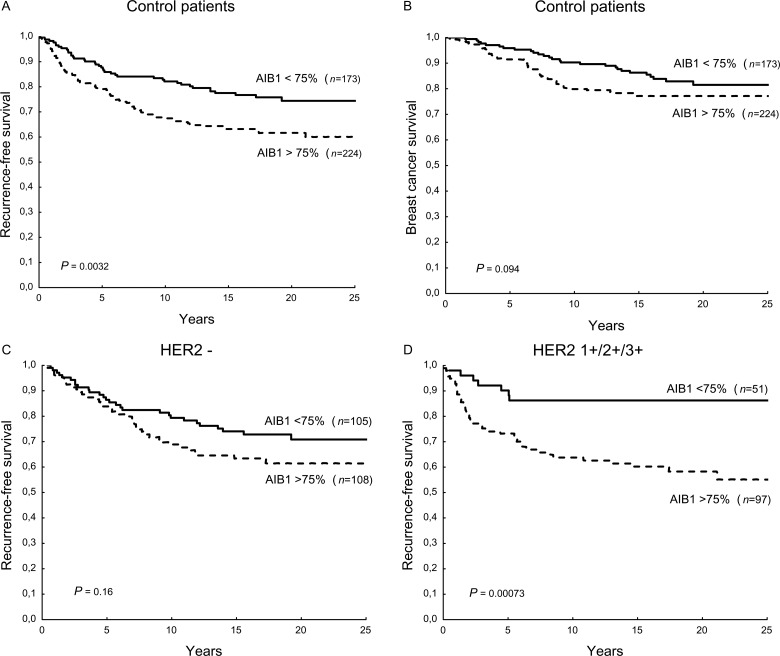

The prognostic importance of AIB1 was analysed in the group of patients not treated with tamoxifen. A high AIB1 proportion score was significantly associated with lower RFS (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.20–2.53, P = 0.0038), as was a high total score of AIB1 in the ER-positive group (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.09–2.52, P = 0.019) (Figure 3). The proportion score was not significantly associated with BCS, but showed a similar trend as for RFS (HR 1.49, 95% CI 0.93–2.39, P = 0.098), and tended to be associated with lower RFS also when restricting the analysis to ER-negative disease (HR 1.96, 95% CI 0.96–4.0, P = 0.065). Refining the analysis to more than two categories based on AIB1 frequency did not further improve the prognostic significance (data not shown). In multivariate analysis, AIB1 remained a significant prognostic factor (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). The intensity of stained cells was not significantly associated with RFS (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of recurrence-free survival (RFS) (A) and breast cancer survival (BCS) (B) in the control arm in relation to AIB1 expression. RFS was further analysed in relation to AIB1 and HER2 expression. RFS is shown for patients with tumours graded as HER2-negative (C) and HER2 1+/2+/3+ (D).

The prognostic significance of AIB1 frequency was clearly seen in patients with tumours expressing HER2 (HR 3.55, 95% CI 1.59–7.94, P = 0.002) as opposed to patients with tumours lacking HER2 (HR 1.41, 95% CI 0.87–2.29, P = 0.16) (Figure 3). A test for interaction between AIB1 and HER2 on the effect on RFS was significant (P = 0.042).

discussion

This cohort based on a randomised tamoxifen trial gave a unique opportunity to study AIB1 both as a treatment predictive and prognostic factor. High expression of AIB1 predicted a good response to tamoxifen treatment, but a poor prognosis among systemically untreated patients. Both results are consistent with the view of AIB1 being an important co-activator for ER signalling and as such a marker for oestrogen dependence. The association between AIB1 and tamoxifen efficacy was in particular evident when the tumours were highly ER positive.

The first study of AIB1 and clinical outcome by Osborne et al. [11] found high expression to be associated with lower survival in patients treated with tamoxifen. We found that there was no significant benefit from tamoxifen for patients with low AIB1 expression, in line with the findings reported by Alkner et al. [15], in which high expression of AIB1 was found to predict a good response to tamoxifen in premenopausal women. Our results suggest that high AIB1 could predict a good response to tamoxifen also for postmenopausal patients. In contrast to previous studies, the study by Alkner et al. [15] and the present were based on randomised, controlled trials.

Previous studies have used different cut-off values for positivity or high expression, and the results have varied from 10% to 75% [11–16]. When using the frequency score, we found over-expression in 59% of the tumours. This is similar to the finding that 64% of breast cancers over-express AIB1 mRNA [5]. The STEPP analysis suggests that the prediction of tamoxifen benefit may be favoured by a high cut-off value for the frequency score.

In patients not receiving tamoxifen, we found high expression of AIB1 to be associated with lower RFS and BCS, indicating that AIB1 could be a prognostic marker. The expression of AIB1 has been shown to increase when breast epithelium transforms from normal to malignant [22]. AIB1 may also increase the invasiveness of tumour cells [23]. This implicates that AIB1 could be important in tumour formation and subsequent spread of the cancer cells. Similar to our results, Alkner et al. [15] found that high AIB1 was associated with lower RFS in untreated patients. A recent report based on a large cohort confirmed that AIB1 has a negative impact on prognosis in ER-negative breast cancer [16], and our results suggest that this holds true also when confining the analysis to systemically untreated patients.

High expression of AIB1 was associated with expression of ER, PgR, HER2 and high tumour grade. The association between HER2 and AIB1 was stronger regarding the total score when compared with frequency score (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online), which indirectly reflects a strong association between HER2 and AIB1 intensity score. This in turn may explain why the ability to predict tamoxifen benefit was slightly different when applying the different AIB1 scores.

There is a bidirectional cross-talk between the ER and growth factor receptors. This may be a way of overcoming the antiproliferative effects of anti-oestrogens that could lead to insensitivity to tamoxifen in breast cancer cells over-expressing both AIB1 and HER2 [24]. Patients with tumours expressing high levels of both proteins exhibited the worst clinical outcome [11]. Similarly, others have found an association between AIB1 and shorter survival only in the subgroup over-expressing HER2 [12, 14]. We found that high expression of AIB1 was significantly associated with HER2 expression and the prognostic importance of AIB1 was only seen when the tumours also expressed HER2. For patients with tumours over-expressing both proteins, RFS was not increased in the tamoxifen-treated group. However, this group consisted of only 18 patients, and the results should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, our results suggest that high AIB1 is a predictive marker of tamoxifen benefit among postmenopausal women with ER-positive breast cancer and a prognostic marker of worse survival in systemically untreated patients. AIB1 has been shown to enhance the effects of oestrogen, which may be in accordance with the view of AIB1 as a negative prognostic factor that at the same time predicts good benefit from tamoxifen. However, this study does not exclude that a minor subgroup of patients with ER-positive tumours simultaneously over-expressing AIB1 and HER2 exhibit resistance to tamoxifen.

funding

The work was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society (#110504) and the Swedish Research Council (#B0771901).

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank Birgitta Holmlund for excellent technical assistance.

references

- 1.Ali S, Coombes R. Endocrine responsive breast cancer and strategies for combating resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:101–110. doi: 10.1038/nrc721. doi:10.1038/nrc721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green K, Carroll J. Oestrogen-receptor mediated transcription and the influence of co-factors and chromatin state. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:713–719. doi: 10.1038/nrc2211. doi:10.1038/nrc2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith C, Nawaz Z, O'Malley B. Coactivator and corepressor regulation of the agonist/antagonist activity of the mixed antiestrogen, 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:657–666. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0009. doi:10.1210/me.11.6.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takimoto G, Graham J, Jackson T, et al. Tamoxifen resistant breast cancer: coregulators determine the direction of transcription by antagonist-occupied steroid receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;69:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00148-4. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(98)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anzick S, Kononen J, Walker R, et al. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997;277:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suen CS, Berrodin T, Mastroeni R, et al. A transcriptional coactivator, steroid receptor coacivator-3, selectively augments steroid receptor transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27645–27653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27645. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.42.27645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan J, Tsai S, Tsai M. SRC-3/AIB1: transcriptional coactivator in oncogenesis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00315.x. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louie M, Zou J, Rabinovich A, et al. ACTR/AIB1 functions as an E2F1 coactivator to promote breast cancer cell proliferation and antiestrogen resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5157–5171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5157-5171.2004. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.12.5157-5171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J, Lioao L, Ning G, et al. The steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 (p/CIP/RAC3/AIB1/ACTR/TRAM-1) is required for normal growth, puberty, female reproductive function, and mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;12:6379–6384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120166297. doi:10.1073/pnas.120166297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torres-Arzayus M, Font de Mora J, Yuan J, et al. High tumor incidence and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in transgenic mice define AIB1 as an oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.027. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborne CK, Bardou V, Hopp T, et al. Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) and HER-2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:353–361. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.353. doi:10.1093/jnci/95.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkegaard T, McGlynn L, Campbell F, et al. Amplified in breast cancer 1 in human epidermal growth factor receptor-positive tumors of tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1405–1411. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1933. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harigopal M, Heymann J, Ghosh S, et al. Estrogen receptor co-activator (AIB1) protein expression by automated quantitative analysis (AQUA) in a breast cancer tissue micro array and association with patient outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0063-9. doi:10.1007/s10549-008-0063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redmond A, Bane F, Stafford A, et al. Coassociation of estrogen receptor and p160 proteins predicts resistance to endocrine treatment; SRC-1 is an independent predictor of breast cancer recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2098–2106. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1649. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alkner S, Bendahl PO, Grabau D, et al. AIB1 is a predictive factor for tamoxifen response in premenopausal women. Ann Oncol. 2009;21:238–244. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp293. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spears M, Oesterreich S, Migliaccio I, et al. The p160 ER co-regulators predict outcome in ER negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:463–472. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1426-1. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutqvist LE, Johansson H. Long-term follow-up of the randomised Stockholm trial on adjuvant tamoxifen among postmenopausal patients with early stage breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:133–145. doi: 10.1080/02841860601034834. doi:10.1080/02841860601034834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoshnoud MR, Löfdahl B, Fohlin H, et al. Immunohistochemistry compared to cytosol assays for determination of estrogen receptor and prediction of the long-term effect of adjuvant tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:421–430. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1202-7. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.List HJ, Reiter R, Singh B, et al. Expression of the nuclear coactivator AIB1 in normal and malignant breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;68:21–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1017910924390. doi:10.1023/A:1017910924390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansson A, Delander L, Gunnarsson C, et al. Ratio of 17HSD1 to 17HSD2 protein expression predicts the outcome of tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3610–3616. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2599. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonetti M, Gelber RD. A graphical method to assess treatment-covariate interactions using the Cox model on subsets of the data. Stat Med. 2000;19:2595–2609. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001015)19:19<2595::aid-sim562>3.0.co;2-m. doi:10.1002/1097-0258(20001015)19:19<2595::AID-SIM562>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy L, Simon S, Parkes A, et al. Altered expression of estrogen receptor coregulators during human breast tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6266–6271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Louie M, Chen HW, et al. Proto-oncogene ACTR/AIB1 promotes cancer cell invasion by up-regulating specific matrix metalloproteinase expression. Cancer Lett. 2008;261:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.11.013. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shou J, Massarweh S, Osborne CK, et al. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:926–935. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh166. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.