Abstract

Cyclophilin A (CypA) is a ubiquitously distributed protein present both in intracellular and extracellular spaces. In atherosclerosis, various cells, including endothelial cells, monocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells and platelets, secrete CypA in response to excessive levels of reactive oxygen species. Atherosclerosis, a complicated disease, is the result of the interplay of different risk factors. Researchers have found that CypA links many risk factors, including hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes, to atherosclerosis that develop into a vicious cycle. Furthermore, most studies have shown that secreted CypA participates in the developmental process of atherosclerosis via many important intracellular mechanisms. CypA can cause injury to and apoptosis of endothelial cells, leading to dysfunction of the endothelium. CypA may also induce the activation and migration of leukocytes, producing proinflammatory cytokines that promote inflammation in blood vessels. In addition, CypA can promote the proliferation of monocytes/macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells, leading to the formation of foam cells and the remodelling of the vascular wall. Studies investigating the roles of CypA in atherosclerosis may provide new direction for preventive and interventional treatment strategies in atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Cyclophilin A, CD147

Atherosclerosis is a complicated, progressive inflammatory disease resulting from various risk factors including hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes (1–2). Many proinflammatory cytokines and immune factors are involved in atherogenesis and exert their roles in an interplay with atherosclerosis-related cells such as endothelial cells (ECs), T lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs).

Recently, mounting evidence has highlighted the potential effects of cyclophilin A (CypA) in atherosclerosis. The CypA protein belongs to the immunophilin superfamily, which is widely distributed both in intracellular and extracellular spaces. In response to a variety of inflammatory stimuli (3–4), CypA can be secreted by ECs, monocytes, VSMCs and platelets in atherosclerotic lesions (5–8). Large quantities of CypA have been found in plaques from mouse models of atherosclerosis (Figure 1) (9–11). Extracellular CypA is strongly associated with various risk factors for atherosclerosis including hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes (12–14). In addition, CypA is capable of triggering the activation and apoptosis of ECs (10). CypA also exhibits potent chemotactic effects on inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and T lymphocytes, by promoting their inflammatory activities (10,15). For example, the production of macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) – two key proatherosclerotic cytokines secreted by inflammatory cells that facilitate plaque formation and instability – are markedly increased by the stimulation of CypA (10,11). However, the absence of CypA decreases lesion area (10). All of this evidence suggests that CypA plays an important role in the development of atherosclerosis. CypA, therefore, represents a potential new target for the treatment of atherosclerosis. The purpose of the present article is to summarize the multiple functions of CypA in atherosclerosis.

Figure 1).

Immunostaining of cyclophilin A (CypA) in atherosclerotic plaques from ApoE−/− mice. Sections of aortic sinus lesions of ApoE−/− mice after 12 weeks of Western diet were stained with hematoxylin-eosin or polyclonal anti-CypA antibodies. A and C Hematoxylin-eosin stain (original magnification ×10 and ×40, respectively). B and D CypA staining with anti-CypA antibody (original magnification ×10 and ×40, respectively). Solid arrowhead indicates vascular smooth muscle cells in media, solid arrow indicates cholesterol clefts, open arrowhead indicates extracellularly near the elastic lamina, and open arrow indicates endothelial cells. Results are representative of four vessels (9). Reproduced with permission from reference 9

DISTRIBUTION, STRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONS OF CypA

Cyclophilins are proteins belonging to the superfamily of immunophilins. They have been found in many types of cells in different organisms and all have peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) activity. CypA was first purified from bovine thymocytes in 1984 and was identified as an intracellular protein with a high affinity for the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporin A (CsA). Human genes of CypA, also known as Cyp18, are located on chromosome 7p11.2–p13 and encode the protein, which consists of 165 amino acid residues with a relative molecular mass of approximately 18×103 Daltons (16–18). While other cyclophilins exist in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria and nucleus, previous studies found that archetypal CypA existed only in the cytoplasm of tissue cells. Later studies revealed that CypA could also be released into the extracellular space. CypA is expressed by various cell types, although its expression levels differ depending on cell type and environmental conditions. For example, CypA levels are higher in the serum and synovial fluids of rheumatoid arthritis patients (3); CypA levels are also elevated in tumours including non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer and breast cancer (19). In atherosclerosis, activated ECs, monocytes, VSMCs and platelets are all able to secrete CypA (5–8).

The structure of human CypA is highly conserved: an eight-stranded antiparallel beta-barrel structure with two alpha helices enclosing the barrel from either side and a compact hydrophobic core formed by seven aromatic and other hydrophobic residues within the barrel where CsA usually binds constitute one CypA molecule. A loop from amino acid residue Lys 118 to His 126 and four beta strands (β3–β6) compose the binding site for CsA (Figure 2) (16,17).

Figure 2).

Ribbon representation of Cyclophilin A (CypA). Cyclosporine A (CsA) – Calcineurin (Cn). Colour codes are CnA, gold; CnB, cyan; CsA, green; CypA, red; Zn2+ and Fe3+, pink; and calcium, blue. The residues from Cn involved in binding of CypA-CsA are shown as blue spheres (17). Reproduced with permission from reference 17

Although structurally conserved, CypA is a protein with various biological functions (3,4,15–29). Similar to other cyclophilins, CypA possesses PPIase activity that can catalyze cis-trans isomerization reactions of proline peptide bonds. It is very important to the folding, assembly and trafficking of proteins, especially proteins containing many proline residues. The PPIase activity of CypA also enables it to act as a chaperone, regulating the activities of a variety of proteins (15–16,20,21). As the target of CsA in cells, CypA may function as an immunomodulator. The compound CsA-CypA is reported to inhibit the activity of calcineurins and block the dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells; consequently, it inhibits the synthesis and release of some cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-2 and promotes the immunosuppressive role of CsA (16–18). In addition, CypA plays important roles in various pathological process such as rheumatoid arthritis, cancers, viral infection and atherosclerosis (3,5,15,19,22,24,25,27–30) (Box 1).

BOX 1. Functions of cyclophilin A (CypA) in various pathological process.

Rheumatic arthritis:

CypA contributes to the inflammatory process through enhacing neutrophils, eosinophils and monocytes chemotaxis, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) production and invasiveness of synoviocytes (3,22–24).

Cancer:

CypA plays important roles in tumour development, malignant transformation, increased proliferation, blockage of apoptosis and metastasis (19).

Viral infection:

For example, CypA is involved in the assembly/deassembly of HIV-1 virion and is required for the full infectious activity of HIV (25).

Atherosclerosis:

CypA initiates the apoptosis of endothelial cells, which may lead to the dysfunction of endothelium. CypA may also function as a chemotactic factor that attracts inflammatory cells, such as T lymphocytes and monocytes, to migrate to inflammatory areas. CypA participates in the formation of the compound caveolin-1/CyPA cyclophilin40/HSP56 in NIH3T3 cells, which is the main carrier of cholesterols, maintaining the balance between intracellular and extracellular cholesterols. It promotes the proliferation of monocytes/macrophages, which causes the remodelling of the vascular wall (5,15,27–30).

RECEPTORS OF CypA IN ATHEROSCLEROSIS

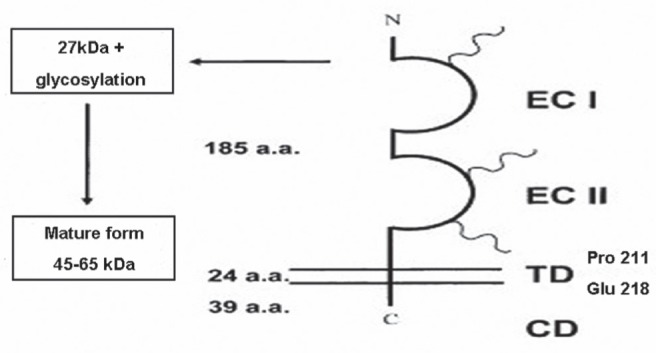

Several molecules have been reported to be extracellular receptors of CypA, including CD147, CD14 and CD91 (31). Among these, it has been suggested that CD147 is the most involved in atherosclerosis. CD147 is a single transmembrane glycoprotein belonging to the superfamily of immunoglobulins (Figure 3) (32). It plays a critical role in fetal, neuronal and lymphocyte development, and is associated with pathological conditions such as heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, tumour, inflammation and autoimmune disease. The proline 180 and glycine 181 residues in the extracellular domain of CD147 are important to CypA-induced signalling events involving mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), which may participate in many biological functions in atherosclerosis, including the activation, migration and proliferation of atherosclerosis-related cells and the regulation of various proinflammatory cytokines. Active site residues of CypA are also crucial to the structural stability of CD147 (33).

Figure 3).

Scheme of the CD147 molecule. CD147 is a transmembrance glycoprotein composed of an extracellular domain of 185 residues, a 24-residue transmembrance domain and a 39-amino acid cytoplasmic region. Three N-linked glycosylation sites critical to the function of CD147 have been identified with CD47 immunoglobulin domains. Three N-linked oligosaccharides are shown by helixes (31). CD Cytoplasmic domain; ECI First extracellular immunoglobulin domain; ECII Second extracellular immunoglobulin domain; TD Transmembrane domain. Reproduced with permission from reference 31

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CypA AND RISK FACTORS IN ATHEROGENESIS

Atherosclerosis is a complicated disease with many different risk factors implicated in, for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes. CypA is tightly associated with the atherogenic process mediated by these risk factors (2,12–14,34,35).

CypA and hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia causes injury to the vascular endothelium and is an important risk factor for atherosclerosis. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) is known to damage endothelium by disrupting the activation of the compound caveolin-1/CyPA/cyclophilin40/HSP56, preventing the translocation and stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS), leading to reduced NO expression, abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation, decreased blood flow, platelet aggregation, leukocyte adhesion and migration, and VSMC proliferation. All of these changes increase the risk for atherosclerosis (36,37).

Caveolae are flask-shaped invaginations of the plasma membrane involved in transcytosis. Early studies showed that caveolin-1 plays an important role in intracellular cholesterol trafficking from the ER to the plasma membrane by forming a complex with CypA, Cyp40 and heat-shock protein 56, maintaining the balance between intracellular and extracellular cholesterols. CypA has been associated with the cytoplasmic side of plasma membrane caveolae. The inhibitor CsA was tested to determine whether it could prevent the rapid translocation of cholesterol from the ER to caveolae (12).

Cholesterol is critical to the structure and function of caveolae. Studies have reported that ox-LDL disrupts the organization of the complex by removing caveolae cholesterol, while high-density lipoprotein prevented the depletion of caveolae cholesterol by ox-LDL. Therefore, a damaging effect has been attributed to ox-LDL, whereas high-density lipoprotein appears to play a general protective role in vascular disease including atherosclerosis. It is believed that both cholesterol carriers and lipoprotein dysfunction are involved in hyperlipidemia in blood vessels (12).

CypA and hypertension

Hypertension is another important risk factor for atherosclerosis. As a reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediator that secretes oxidative stress-induced factor, CypA mediates the production of ROS through the ERK1/2, AKT and JAK signalling pathways from various cells, such as ECs and VSMCs, causing the decrease of eNOS levels, whose function is to promote the generation of NO and blood pressure regulation (26). In addition, CypA affects the activity of atrial natriuretic factor and its receptor membrane-bond guanylate cyclase-A (GC-A), which are involved in the regulation of blood pressure. Previous studies have shown that CypA can inhibit the activation of GC-A by atrial natriuretic factor. A hypothesized mechanism is that CypA binds to GC-A and catalyzes the cis-trans isomerization of Pro 822, 902 or 958, which maintains GC-A in the inactive state (13). Evidence suggests that CypA is associated with blood pressure regulation. CypA-mediated hypertension may be an promotor of atherogenesis.

CypA and diabetes

Diabetes characterized by metabolic abnormalities, such as hyperglycemia, increased free fatty acid levels, insulin resistance and the constant rate of low-grade inflammation of endothelium, is also an important risk factor for atherosclerosis. In diabetes, high glucose levels and ROS activate monocytes to secrete CypA via vesicles. CypA is a potential screening marker for vascular disease in diabetes (14). It was observed that CypA levels in plasma samples of patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease were higher compared with plasma obtained from healthy volunteers, suggesting that CypA secreted from monocytes in patients with diabetes is an important pro-inflammatory stimulus for vascular inflammation (14). Secreted CypA acts as a proinflammtory cytokine that activates endothelial cells and leukocytes, increasing inflammation in vessels and promoting atherogenesis. Subsequently, inflammation influences blood glucose levels, generating a vicious cycle that exacerbates diabetes mellitus. It is clear that diabetes and atherosclerosis can affect one another, with CypA being one of the factors connecting diabetes and atherosclerosis.

Interaction of risk factors

Atherosclerosis is the result of the complex interplay among different risk factors. Endothelial damage, ROS and other free radicals have predominantly emerged as factors in virtually all pathways leading to the development of atherosclerosis due to hyperlipidemia, hypertension or diabetes (34,35). For example, excessive ox-LDL levels cause decreased NO expression from the endothelium, leading to abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation and decreased blood flow. This is one of the primary causes of hypertension. Consequently, endothelial dysfunction induced by hypertension intervenes in the metabolism of lipids, promoting hyperlipidemia. Hyperlipidemia and hypertension are part of the metabolic syndrome, which is characteristic of diabetes. Once diabetes develops, chronic inflammation in vessels, together with the metabolic syndrome, disturbs the regulation of blood lipid levels and blood pressure. These risk factors interact with one another, generating a vicious cycle to accelerate atherogenesis, and CypA appears to be an important cytokine in this process.

DIRECT EFFECTS OF CypA ON CELLS IN ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Effects of CypA on ECs

Dysfunction of ECs:

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease in which many proinflammatory factors are implicated. As a mediator of proinflammatory factors, normal ECs play an important role in preventing atherosclerosis. The dysfunction of ECs may be the first step in the development of atherosclerosis (33,38). The endothelial monolayer, which is in contact with flowing blood, maintains the integrity of the vascular wall and resists pathological adhesion of leukocytes (39,40). Once injured, the endothelium becomes dysfunctional by releasing less NO and losing the function of endothelium-dependent vasodilation, thereby facilitating the aggregation of platelets and promoting the expression of adhesion molecules (37). In response to risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia and smoking, several ROS, including superoxide anion (O2−.), hydroxyl radical (HO.), nitric oxide (NO.), lipid radicals, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and hypochlorous acid (HOCL), are released from various cells, leading to the injury of ECs and the secretion of CypA (5,7,15,41,42). Secreted CypA mediates the production of ROS through the ERK1/2, AKT and JAK signalling pathways via a positive feedback loop, causing a decrease in eNOS activity, whose function is to promote the generation of NO, thus leading to further damage to the intima (10,20).

Activation of ECs:

Extracellular CypA also triggers the activation of ECs to produce various adhesion molecules that attract leukocytes. Studies show that a high concentration of CypA induces the expression of adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 and E-selectin via signalling pathways involving MAPK and NF-κB, with increases in the expression of toll-like receptors (TLRs) such as TLR-4 (5,10,42). TLR-4 is found to be able to initiate a signalling cascade including the binding of adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor 88 and the activation of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase and tumour-necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor-6, resulting in the final translocation of NF-κB (43). It also initiates the activation of MAPK (43). Therefore, the mechanism of the activation of ECs is possibly associated with the expression of TLRs. These adhesion molecules, together with many other proinflammatory cytokines, such as very late antigen (VLA)-4 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1, which are released by leukocytes, induce the adhesion of leukocytes to the vascular endothelium where atheroma initiates.

Apoptosis of ECs:

CypA acts as a proapoptotic cytokine that triggers the apoptosis of ECs. In vitro studies have found that low concentrations of CypA increases EC proliferation, while high concentrations of CypA has the opposite effect, decreasing EC viability (5). Similar to TNF-α, CypA has been found to induce cell death in the presence of cycloheximide (9). The mechanism is associated with increased JNK and p38 activities (10,44). Recently, CypA has also been found to bind to apoptosis-inducing factor and participate in the unclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor to induce apoptosis (45). CypA deficiency was associated with a marked decrease in ECs apoptosis in early stages of atherosclerosis (10). This information may provide new insight for the study of EC apoptosis and atherosclerosis development.

Regenerative ECs will settle at sites where an atheroma grows to repair the vascular wall, but they do not possess all of the properties of normal ECs. For example, they lack the signalling pathway that is dependent on Gi (38). Many leukocytes and lipids deposit under the dysfunctional endothelium to initiate atherogenesis.

Effects of CypA on leukocytes

Recruitment of leukocytes:

The initial process of active leukocyte recruitment is the tethering and rolling of leukocytes. Together with other chemokines and adhesion molecules, E-selectin expressed on the activated endothelium induced by CypA plays an important role in the rolling of leukocytes through binding with its ligands such as glycoprotein P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1, which is expressed as a homodimer on leukocytes (46).

As a direct chemoattractant for leukocytes, CypA also induces the accumulation of leukocytes, such as neutrophils, eosinophils, T lymphocytes and monocytes within atheroma lesions, which facilitate their adhesion to the injured endothelium (23,27,47). In vivo studies have shown that most leukocytes tend to migrate toward extracellular CypA when it is injected into the body. Activated T lymphocytes and monocytes, which are critical for the development of atherosclerosis, show high chemotaxis to extracellular CypA and its receptor CD147 (27). The process by which CypA mediates chemotaxis is largely unclear, but studies have shown that CypA is involved in chemokine receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor (CXCR) 4-mediated chemotaxis. It has also been proposed that CypA mediates CXCL12-induced chemotaxis by regulating MAPK (48). These two mechanisms may provide new insights for research on the migration of leukocytes induced by CypA.

Adhesion of leukocytes:

Once recruited to the injured endothelium, leukocytes will adhere to ECs on stimulation of adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1, whose expression is induced by CypA (10). Endothelial VCAM-1 is a ligand for the integrin α4β1 (VLA-4) predominantly found on lymphocytes and monocytes. The interaction between VCAM-1 and VLA-4 mediates rolling and firm adhesion of leukocytes (49).

Leukocytes then pass through the junctions between the ECs and differentiate, producing various bioactive factors such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor-β, interferon (IFN)-γ, CD25, IFN-induced transmember 1 (IFITM1), macrophage chemoattractant protein-1, M-CSF and MMPs which interplay to promote inflammation in atherosclerosis. This activation process of leukocytes is also associated with CypA (3,4,41,50). Among these cytokines, some, such as TNF and IFN, promote atherosclerosis, while others, such as transforming growth factor, play an anti-inflammatory role. Although it is a complicated pathological process, a remarkable reduction in atherosclerosis in CypA-deficient mice than normal mice strongly supports that CypA contributes to atherosclerosis.

Formation and activation of foam cells:

Hypercholesterolemia is an important causative risk factor for atherosclerosis. It is well established that the transport of LDL cholesterol into the artery wall promotes atherosclerosis (10). Studies (10) have reported that apolipoprotein E-deficient mice fed a high-cholesterol diet developed more severe atherosclerosis compared with apolipoprotein E- and CypA-deficient mice, demonstrating that CypA was atherogenic by enhancing LDL uptake. This mechanism was associated with the regulation of the expression of scavenger receptor on the vessel wall.

Many lipid-laden monocytes/macrophages, also known as foam cells, characterize the early atherosclerotic lesion. After settling under the endothelium, quantities of monocytes will differentiate into macrophages that endocytose lipids. They accumulate under the vascular endothelium to form fatty streaks. CypA contributes to the formation of foam cells and the upregulation of NF-κB-related proteins, such as the cytokine M-CSF and MMPs, which are released from foam cells. Experiments show that the expression of M-CSF, cell-derived MMP-9 and member type 1 MMP (MT1-MMP, MMP-14) are effectively hindered after either CypA or CD147 inhibition (11,51). M-CSF plays an important role in the transition of monocytes to lipid-laden macrophages by increasing the expression of scavenger receptor A, which functions to internalize modified lipoproteins to form fatty streaks (10). This augments the production of cytokines and growth factors from foam cells and promotes the proliferation of monocytes/macrophages (1). MMPs, such as MMP-9 and MT1-MMP, which are released from macrophages induced by CypA and its receptor, CD147, are the main causes for acute cardiovascular events. MMPs mainly degrade extracellular matrix, resulting in the weakening of plaque stability and even the fracture of the fibrous cap. We found that the expression of MMP-9 from macrophages required the activation of MAPK (ERK1/2), which initiated Iκ-B/NF-κB(4). Therefore, the cascade EMMPRIN (CD147)-ERK-NF-κB may be the main signalling pathway for CypA-induced MMP-9 upregulation (4). MT1-MMP is likely to be expressed through the same pathway because NF-κB is an important transcriptional factor of MT1-MMP expression (50,51). Besides MMP-9 and MT1, MMP are produced by macrophages within vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques, MMP-2 derived from activated VSMCs is also speculated to be associated with plaque instability (52) because CypA has been reported to be essential to the production of MMP-2 in the pathological progression of diseases such as acute myocardial infarction, rheumatosis and cancers.

Similarly, macrophages may proliferate to try to eliminate excessive lipids, forming more foam cells (53). CypA is essential to macrophage proliferation, which depends on M-CSF. In the early stage of M-CSF signalling, immunosuppressor sanglifehrin A, a member of the CypA inhibitor family, is able to inhibit the phosphorylation of Raf-1 and ERK1/2, arresting the G1 phase of the cell cycle. This indicates that the proliferation of macrophages may be dependent on the activation of the Raf-1/ MEK/ ERK signal pathway that is regulated by CypA and its receptor (28).

In addition, on coincubation with platelets, CD34+ progenitor cells have the potential to differentiate into foam cells (11). Although no direct evidence regarding influence of CypA on progenitor cell number, size, morphology or the expression of the differentiation marker CD68 has been found, it was observed that inhibition of soluble CypA by its inhibitor N1M811 reduced MMP-9 activity during the CD34+ progenitor cell differentiation process (11), demonstrating that CypA was an important promoter of atherogenesis.

Consequently, an increasing number of foam cells accumulate under the injured endothelium, which is an important component for atherosclerotic plaques.

Effects of CypA on VSMCs

Another important feature of atherosclerosis is the thickening of the arterial wall. In addition to inducing the proliferation of macrophages, CypA is necessary for the multiplication of VSMCs, which also accumulate in plaques and contribute to the formation of a complicated atheroma. VSMCs secrete CypA in a vesicular manner (7), and CypA can initiate the ERK1/2 and JAK/STAT signalling pathways, which are beneficial to DNA synthesis in VSMCs, and promote the thickening of the intima and the medial layer (30,31). On stimulation of growth factors and cytokines, such as platelet-derived growth factor, fibroblast growth factor-b, TNF-α and epidermal growth factor, masses of VSMCs migrate to the endothelium and alter their phenotype from contractile to the synthetic type, laying down an abundant extracellular matrix and various fibres to form fibrous caps in plaques. CypA also promotes the multiplication of fibroblasts by inducing excessive production of ROS, which directly stimulates the migration and proliferation of fibroblasts and contributes to the remodelling of the vascular wall.

As a large number of foam cells and VSMCs gradually accumulate under the intima, the lesion will become bulkier until it narrows the arterial lumen and even hampers blood flow, thus leading to clinical manifestations such as unstable angina pectoris. MMPs released by foam cells and VSMCs, which mainly degrade extracellular matrix, may cause the weakening of plaque stability and even the fracture of fibrous caps, resulting in acute myocardial infarction.

SIGNALLING PATHWAYS MEDIATED BY CypA IN ATHEROSCLEROSIS

In atherogenesis, CypA mediates a variety of signalling pathways, such as MAPK, NF-κB and JAK/STAT, to regulate various pathological processes (Figure 4) (20,26,28,31,54,55).

Figure 4).

Various signalling pathways that cyclophilin A (CypA) mediates. CypA mediates a variety of signalling pathways involving mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and JAK/STAT to regulate various pathological processes in atherogenesis

In response to various intracellular and extracellular stimuli, including cytokines, hormones, growth factors and cellular stressors, CypA initiates the MAPK signalling pathway via its receptor CD147, which appears to be at the crossroads of the inflammatory response (56–58). In the MAPK mammalian family, MAPK (ERK1/2) induces many pathological processes of atherosclerosis such as the injury of ECs, the chemotactic migration and adhesion of leukocytes, the formation of foam cells, the secretion of MMPs and the proliferation of atherosclerosis-related cells. However, MAPK (JNK2) and MAPK (P38) contribute to the formation of foam cells and the proliferation of VSMCs (59).

NF-κB is another important signalling molecule activated by CypA-CD147 that participates in the process of atherogenesis. It regulates the genes that encode proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, chemokines, growth factors and inducible enzymes, fine-tuning the response of the vascular wall to injury and facilitating the formation, growth and even rupture of plaques (60,61). For example, NF-κB potentiates the production of chemokines such as MCP-1 and IL-8, which induce the migration of inflammatory cells; adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 that facilitate the adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium and pro-inflammtory cytokines such as M-CSF and MMPs, which promote the formation of foam cells and the rupture of plaques. NF-κB is a heterodimer of p50 and p65, which usually remains inactive by combining with IκB in the cytoplasm. When activation signals arrive, IκB will be phosphorylated and consequently degraded by proteasomes. The free NF-κB heterodimer then moves into the nucleus, inducing various biological activities (54,62). Some studies have reported that ERK inhibitors, not JNK and P38 inhibitors, are able to decrease NF-κB activation, demonstrating that ERK may be the upstream pathway leading to NF-κB activation (4).

CypA also activates JAK/STAT, which participates in the development of atherosclerosis. STAT3 appears to play a negative role in controlling inflammation, and STAT4 drives the differentiation of naive T cells into T helper 1 (Th1) cells, which promote inflammation; STAT6 facilitates the differentiation of Th2 cells that inhibit the functions of Th1 (60). In addition, JAK/STAT induces the production of ROS and the proliferation of VSMCs, contributing to atherogenesis.

Many other signalling pathways in the development of atherosclerosis may also be associated with CypA; therefore, more studies are required to fully understand the specific mechanisms linking CypA to atherogenesis.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

CypA is an inflammatory mediator in atherosclerosis. It links various risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes, which promote atherogenesis. It also induces endothelial dysfunction, inflammation in vessels, the production of foam cells, the remolding of vascular wall and the weakening of plaque stability. In vivo experiments show that CypA deficiency leads to a marked reduction in atherosclerosis (9,10). All of the evidence discussed, including the biological functions and signalling pathways that CypA mediates, shows that CypA serves as an important atherogenic factor in the development of atherosclerosis, demonstrating that CypA could be a therapeutic target for the prevention of and intervention in atherosclerosis.

This evidence helps us understand the relationship between CypA and atherosclerosis. However, many other specific mechanisms and biological functions that are induced by CypA in atherogenesis remain unclear. For example, the signalling pathway of EC apoptosis, the activation mechanisms of ECs and leukocytes, the migration and adhesion process of inflammatory cells, the details of the formation of foam cells and the complicated interaction of various proinflammatory cytokines and biological signalling pathways all remain unclear. Studies of these mechanisms may provide more information about how CypA promotes atherogenesis. More research is needed on the specific signalling pathways, such as JNK and p38, that help CypA to induce apoptosis in ECs, TLR-associated activation process of ECs, the relationship of CXCR4 and CXCR12 to CypA-mediated chemotaxis and the influence of CypA to the growth of vascular progenitor cells. However, it is not enough to fully understand atherosclerosis simply at the molecular and cellular level because atherosclerosis is a complicated disease that involves many biological and pathological processes. Therefore, many animal experiments and clinical trials are needed to objectively and thoroughly study it. Although a few in vivo models have verified that CypA expression is increased in atherosclerosis and it promotes atherogenesis (9,10), more models will help to explore specific biological functions of CypA in atherosclerosis.

Moreover, many new viewpoints about CypA in atherosclerosis should be considered. Recent publications indicate that CypA is involved in diseases such as acute lung injury, HIV infection, hepatitis and rheumatoid arthritis by its interplay with its receptor CD147 (21–24,32); therefore, we may be able to determine whether these diseases are additional risk factors for atherosclerosis. It may also be valuable to investigate immunological activity of CypA in atherosclerosis. In addition, determining which inhibitors can target CypA to block the development of atherosclerosis could be of great significance. Although the immunosuppressant drug CsA has been reported to be able to inhibit some functions of CypA, it is not a specific ligand, and may cause certain side effects. Therefore, a specific inhibitor will be more valuable.

Studies investigating the functions of CypA in atherosclerosis will provide new insights for preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Innovative research project of Shanghai Education Committee (09YZ80, to Dr Zhang).

REFERENCES

- 1.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao X, Ait-Aissa X, Lagrange J, Youcef G, Louis H. Hypertension, hypercoagulability and the metabolic syndrome: A cluster of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Biomed Mater Eng. 2012;22:35–48. doi: 10.3233/BME-2012-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim H, Kim WJ, Jeon ST, et al. Cyclophilin A may contribute to the inflammatory processes in rheumatoid arthritis through induction of matrix degrading enzymes and inflammatory cytokines from macrophages. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:217–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan W, Ge H, He B. Pro-inflammatory activities induced by CyPA-EMMPRIN interaction in monocytes. Atherosclerosis. 2010;213:415–21. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SH, Lessner SM, Sakurai Y, Galis ZS. Cyclophilin A as a novel biphasic mediator of endothelial activation and dysfunction. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1567–74. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63715-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherry B, Yarlett N, Strupp A, Cerami A. Identification of cyclophilin as a proinflammatory secretory product of lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3511–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki J, Jin ZG, Meoli DF, Matoba T, Berk BC. Cyclophilin A is secreted by a vesicular pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:811–7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216405.85080.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coppinger JA, Cagney G, Toomey S, et al. Characterization of the proteins released from activated platelets leads to localization of novel platelet proteins in human atherosclerotic lesions. Blood. 2004;103:2096–104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin Z-G, Lungu AO, Xie L, Wang M, Wong C, Berk BC. Cyclophilin A is a proinflammatory cytokine that activates endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1186–91. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000130664.51010.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nigro P, Satoh K, O’Dell MR, et al. Cyclophilin A is an inflammatory mediator that promotes atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:53–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seizer P, Schonberger T, Schott M, et al. EMMPRIN and its ligand cyclophilin A regulate MT1-MMP, MMP-9 and M-CSF during foam cell formation. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everson WV, Smart EJ. Influence of vaveolin, cholesterol, and lipoproteins on nitric oxide synthase implications for vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2001;11:246–50. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen ZJ, Vetter M, Chang GD, et al. Cyclophilin A functions as an endogenous inhibitor for membrane-bound guanylate cyclase-A. Hypertension. 2004;44:963–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145859.94894.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramachandran S, Kartha CC. Cyclophilin-A: A potential screening marker for vascular disease in type-2 diabetes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90:1005–15. doi: 10.1139/y2012-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palacin M, Rodriguez I, Garcia-Castro M, et al. A search for cyclophilin-A gene (PPIA) variation and its contribution to the risk of atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Int J Immunogenet. 2008;35:159–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2008.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang P, Heitman J. The cyclophilins. Genome Biol. 2005;6:226. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-7-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huai Q, Kim HY, Liu Y, et al. Crystal structure of calcineurin-cyclophilin-cyclosporin shows common but distinct recognition of immunophilin-drug complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12037–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192206699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obchoei S, Wongkhan S, Wongkham C, Li M, Yao Q, Chen C, Cyclophilin A. Potential functions and therapeutic target for human cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:RA221–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Kim SS. An overview of cyclophilins in human cancers. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1561–674. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh K, Shimokawa H, Berk BC. Cyclophilin A: Promising new target in cardiovascular therapy. Circ J. 2010;74:2249–56. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Yang F, Robotham JM, Tang H. Critical role of cyclophilin A and its prolyl-peptidyl isomerase activity in the structure and function of the hepatitis C virus replication complex. J Virol. 2009;83:6554–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02550-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Wang CH, Jia JF, et al. Contribution of cyclophilin A to the regulation of inflammatory processes in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:24–33. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arora K, Gwinn WM, Bower MA, et al. Extracellular cyclophilins contribute to the regulation of inflammatory responses. J Immunol (Baltimore, 1950) 2005;175:517–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang CH, Dai JY, Wang L, Jia JF, Zheng ZH, Ding J. Expression of CD147 (Emmprin) on neutrophilins in rheumatoid arthritis enhances chemotaxis, matrix metalloproteinase production and invasiveness of synoviocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:850–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01084.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ke H, Huai Q. Crystal strutures of cyclophilin and its partners. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2285–96. doi: 10.2741/1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satoh K, Matoba T, Suzuki J, et al. Cyclophilin A mediates vascular remodeling by promoting inflammation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation. 2008;117:3088–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.756106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damsker JM, Bukrinsky MI, Constant SL. Preferential chemotaxis of activated human CD4+ T cells by extracellular cyclophilin A. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:613–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez-Tillo E, Wojciechowska M, Comalada M, Farrera C, Lioberas J, Celada A. Cyclophilin A is required for M-CSF-dependent macrophage proliferation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2515–24. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satoh K, Nigro P, Matoba T, et al. Cyclophilin A enhances vascular oxidative stress and the development of angiotensin II-induced aortic aneurysms. Nat Med. 2009;15:649–56. doi: 10.1038/nm.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satoh K, Matoba T, Suzuki J, et al. Cyclophilin A mediates vascular remodeling by promoting inflammation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation. 2008;117:3088–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.756106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nabeshima K, Iwasaki H, Koga K, Hojo H, Suzumiya J, Kikuchi M. Emmprin (basigin/CD147): Matrix metalloproteinase modulator and multifunctional cell recognition molecule that plays a critical role in cancer progression. Pathol Int. 2006;56:359–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yurchenko V, Constant S, Bukrinsky M. Dealing with the family: CD147 interactions with cyclophilins. Immunology. 2006;117:301–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanhoutte PM. Endothelial dysfunction: The first step toward coronary arteriosclerosis. Circ J. 2009;73:595–601. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh RB, Mengi SA, Xu YJ, Arneja AS, Dhalla NS. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: A multifactorial process. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2002;7:40–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alavantic D, Djuric T. Risk factors of atherosclerosis: A review of genetic epidemiology data from a Serbian population. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2006;11:78–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toda N, Tanabe S, Nakanishi S. Nitric Oxide-mediated coronary flow regulation in patients with coronary artery disease: Recent advances. Int J Angiol. 2011;20:121–34. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1283220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sagach V, Bondarenko A, Bazilyuk O, Kotsuruba A. Endothelial dysfunction: Possible mechanisms and ways of correction. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2006;11:107–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Guelte A, Gavard J. Role of endothelial cell-cell junctions in endothelial permeability. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;763:265–79. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-191-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Alexander JS. Analysis of endothelial barrier function in vitro. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;763:253–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-191-8_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JY, Kim H, Suk K, Lee WH. Activation of CD147 with cyclophilin a induces the expression of IFITM1 through ERK and PI3K in THP-1 cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:821940. doi: 10.1155/2010/821940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kondo T, Hirose M, Kageyama K. Roles of oxidative stress and redox regulation in atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16:532–8. doi: 10.5551/jat.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeuke S, Ulmer AJ, Kusumoto S, Katus HA, Heine H. TLR4-mediated inflammatory activation of human coronary artery endothelial cells by LPS. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:126–34. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu J, Eto M, Akishita M, Okabe T, Ouchi Y. A selective estrogen receptor modulator inhibits TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by activating ERK1/2 signaling pathway in vascular endothelial cells. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;51:21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu C, Wang X, Deinum J, et al. Cyclophilin A participates in the nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor in neurons after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1741–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langer HF, Chavakis T. Leukocyte-endothelial interactions in inflammation. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1211–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu P, Ding J, Zhou J, Dong WJ, Fan CM, Chen ZN. Expression of CD147 on monocytes/macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis: Its potential role in monocyte accumulation and matrix metalloproteinase production. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1023–33. doi: 10.1186/ar1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan H, Luo C, Li R, et al. Cyclophilin A is required for CXCR4-mediated nuclear export of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2, activation and nuclear translocation of ERK1/2, and chemotactic cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:623–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: Pathogenic and regulatory pathways. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:515–81. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt R, Bultmann A, Fischel S, et al. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (CD147) is a novel receptor on platelets, activates platelets, and augments nuclear factor kappa B-dependent inflammation in monocytes. Circ Res. 2008;102:302–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park JM, Kim A, Oh JH, Chung AS. Methylseleninic acid inhibits PMA-stimulated pro-MMP-2 activation mediated by MT1-MMP expression and further tumor invasion through suppression of NF-kappaB activation. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:837–847. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Satoh K, Nigro P, Berk BC. Oxidative stress and vascular smooth muscle cell growth: A mechanistic linkage by cyclophilin A. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:675–82. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vukovic I, Arsenijevic N, Lackovic V, Todorovic V. The origin and differentiation potential of smooth muscle cells in coronary atherosclerosis. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2006;11:123–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim JY, Kim WJ, Kim H, Suk K, Lee WH. The Stimulation of CD147 induces MMP-9 Expression through ERK and NF-kappaB in Macrophages: Implication for atherosclerosis. Immune Netw. 2009;9:90–97. doi: 10.4110/in.2009.9.3.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurdi M, Booz GW. JAK redux: A second look at the regulation and role of JAKs in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1545–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00032.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1263–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim EK, Choi EJ. Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Motoshima H, Goldstein BJ, Igata M, Araki E. AMPK and cell proliferation – AMPK as a therapeutic target for atherosclerosis and cancer. J Physiol. 2006;574:63–71. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muslin AJ. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;115:203–18. doi: 10.1042/CS20070430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidt R, Bultmann A, Fischel S, et al. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (CD147) is a novel receptor on platelets, activates platelets, and augments nuclear factor kappaB-dependent inflammation in monocytes. Circ Res. 2008;102:302–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dabek J, Kulach A, Gasior Z. Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kappaB): A new potential therapeutic target in atherosclerosis? Pharmacol Rep. 2010;62:778–83. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Majdalawieh A, Ro HS. Regulation of I kappa B alpha function and NF-kappaB signaling: AEBP1 is a novel proinflammatory mediator in macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:823821. doi: 10.1155/2010/823821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]