Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationships among seven frailty domains: nutrition, physical activity, mobility, strength, energy, cognition, and mood, using data from three studies.

Study Design and Setting

Data from three studies were separately analyzed using Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). The graphical output of MCA was used to assess 1) if the presence of deficits in the frailty domains separate from the absence of deficits on the graph, 2) the dimensionality of the domains, 3) the clustering of domains within each dimension and 4) their relationship with age, sex and disability. Results were compared across the studies.

Results

In two studies, presence of deficits for all domains separated from absence of deficits. In the third study, there was separation in all domains except cognition. Three main dimensions were retained in each study however assigned dimensionality of domains differed. The clustering of mobility with energy and/or strength was consistent across studies. Deficits were associated with older age, female sex and disability.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that frailty is a multidimensional concept for which the relationships among domains differ according to the population characteristics. These domains, with the possible exception of cognition, appear to aggregate together and share a common underlying construct.

Keywords: Frailty, Domains of frailty, Older persons, Multiple correspondence analysis, Association, Epidemiology

Introduction

Frailty is generally acknowledged to be a state of decreased reserve and cumulative decline in multiple physiologic systems resulting in an increased risk of adverse outcomes [1–6]. Nevertheless, there remains debate on its characteristics [2]. Many studies have reported on the predictive validity of various operational definitions of frailty [3, 5–8]. However, there has been little research exploring the relationships among the proposed characteristics. Bandeen-Roche et al [9] delineated underlying classes of individuals based on the characteristics proposed by Fried et al [3]. We are unaware, however, of published research that has explicitly examined the relationships among the proposed characteristics. Evidence of these relationships is necessary to elucidate whether particular characteristics belong to the construct of frailty.

The objective of this study was to explore the relationships among seven frailty domains using Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). To assess the consistency of the findings, the methods were replicated using data from three studies.

Methods

Description of studies

Data collected at baseline were taken from the Montreal Unmet Needs Study (MUNS) [10], the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) [11] and the System of Integrated Services for Older Persons study (French acronym, SIPA) [12]. The MUNS sample consisted of community-dwelling persons aged 75 years and over living in the Montreal area, with no more than mild cognitive impairment. The CSHA was a study of dementia conducted on 10,263 institutionalized and community-dwelling Canadians aged 65 and over. For the current analysis, only the CSHA community-dwelling participants who completed a clinical assessment were retained. The SIPA study was conducted on community-dwelling persons, aged 65 years and over, living on the island of Montreal and with disability in at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADL).

Domains of frailty

Based on a literature review carried out as part of the Canadian Initiative on Frailty and Aging [13], an inclusive list of frailty criteria was generated. An expert panel grouped the criteria into broader domains using terminology proposed by Bergman et al [2], Ferrucci et al [14] and Studenski et al [15]. Seven domains were retained based on clinical and biological plausibility: nutrition, physical activity, mobility, strength, energy, cognition, and mood.

Measures of frailty

Two authors independently abstracted potential measures for each frailty domain from each of the three studies. Measures of disability as defined by Katz [16] were excluded. The final measures were selected based on how closely they operationalized the domain, their validity and their clinical relevance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Measures of the frailty domains

| Frailty Domain | MUNS | CSHA | SIPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | Self-reported:

|

Self-reported*:

|

NA |

| Physical activity | Self-reported never or from time to time:

|

Self-reported low or no exercise | Self-reported ≤ 4 times/month going to a:

|

| Mobility | Self-reported:

|

Questionably or definitively abnormal gait speed* | Self-reported difficulty walking up or down a flight of stairs |

| Energy | Self-reported difficulty, needing help or inability to walk a block | Participant feeling tired all the time* | Self-reported either:

|

| Strength | NA | Questionably or definitively abnormal*:

|

Self-reported difficulty lifting something that weighs over 5 kg |

| Cognition | ≤17 on the ALFI [25] | Diagnosis of cognitive impairment or dementia according to DSM-III-R criteria* [26] |

|

| Mood | > median (11.9) on the IDPESQ-14 [28] |

|

Determined during physician assessment as part of a medical history

MUNS: Montreal Unmet Needs Study; CSHA: Canadian Study of Health and Aging; SIPA: Integrated Services for Older Persons; NA: Not available; ALFI: Adult Lifestyles and Function Interview; IDPESQ-14: Indice de détresse psychologique de Santé Québec; DSM-III-R: Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; SPMSQ: Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale

There was no measure of nutrition in SIPA and no measure of strength in MUNS. Given the differences in questions selected for the same domain in each study, we found it necessary to dichotomize the questions to arrive at a common set of questions and to facilitate interpretation. Whenever possible, dichotomization was based on referenced cut-offs. Otherwise, cut-offs were defined favouring sensitivity over specificity in identifying subtle vulnerability. When more than one measure was available for a given domain, the overall domain was scored positive for a deficit if any measure was positive.

Analysis

Bivariate correlations between the frailty domains were examined using the tetrachoric correlation coefficient. The graphical output of the Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) was used to assess if the presence of deficits in the frailty domains separate from the absence of deficits on the graph, the dimensionality of the domains, the clustering of domains within each dimension and their relationship with age, sex and disability. A detailed description of this method is presented in Sourial et al (2009) (Ms. Ref. No.: JCE-08-215). Briefly, MCA is used to identify a small number of dimensions in which the largest deviations from independence can be represented. These dimensions are identified through decomposition of the total inertia (a function of the chi-square statistic). Dimension 1 represents the greatest deviation from independence in the data; Dimension 2, the second greatest deviation and so on. Each dimension can be interpreted based on how the presence and absence of deficit for the domains separate on either side of the dimension. Moreover, the further away from the origin a domain’s response category is along a certain dimension, the greater its importance in interpreting that dimension. This positioning also provides insight into the dimensionality of the response categories and which group or “load” together on a same dimension. “Clusters” or response categories very close together on the graph and loading on a same dimension tend to indicate similarities between the responses with moderate to high correlations. Although related, dimensionality of domains differs from clustering since domains can load on the same dimension without necessarily clustering very closely together. Because domain variables are dichotomous, the two points for presence and absence of deficit in each domain are symmetric around the origin. Consequently, the dimensionality and clustering of points is the same whether looking at the presence or the absence of deficit. Given this symmetry, throughout the paper, we refer to dimensionality and clustering of the domains rather than the domain categories. Since we plan to study disability in activities of daily living (ADL) as an outcome of frailty in subsequent analyses, the main analysis was carried out only using the subsamples without disability. For comparison, however, MCA was repeated using all subjects. ADL disability was defined as being unable or needing help to eat, dress, transfer, bathe or toilet [16]. The relationship between the domain variables and age (65–74, 75–84, 85+), sex and disability was investigated using all subjects by including the variables in the MCA as supplementary variables. MCA was performed using PROC CORRESP (SAS 9.1, Cary, NC). Multiple Imputation (MI) was used for missing data [17] and was performed using the Imputation and Variance Estimation Software [18].

Results

Table 2 describes the demographic and frailty characteristics of the three samples. There were 839 participants in MUNS, a subsample of 1,600 from CSHA and 1,164 in SIPA. The proportion of missing data in the proposed frailty domains varied across the three samples. No data were missing in the MUNS. In SIPA, domains had less than 2% missing data with the exceptions of cognition (8.3%) and mood (17.9%). In the CSHA, less than 4% of data were missing except for physical activity (13.8%). Age, presence of disability, and the average number of frailty deficits were lowest in MUNS and highest in SIPA. There were more women than men in all three samples. The percentage of subjects with deficits in mobility, energy, strength and mood was highest in SIPA, while the percentage of subjects with poor physical activity and cognitive deficits was highest in CSHA. The most common deficits in MUNS were nutrition and mood; in CSHA, physical activity and cognition; and, in SIPA, physical activity and energy.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

| MUNS (n=839) | CSHA (n=1600) | SIPA (n=1164) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 79.6 (3.9) | 80.1 (6.9) | 82.2 (7.3) |

| [Range] | [74–96] | [65–99] | [64–104] |

| Female (%) | 68.7 | 58.9 | 70.9 |

| Any ADL disability (%) | 5.5 | 26.1 | 42.4 |

| Mean number of frailty | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.6) | 4.5 (1.3) |

| deficits per subject (SD) | |||

| Percentage (%) with deficit | |||

| Nutrition | 52.3 | 16.8 | NA |

| Physical activity | 20.5 | 67.7 | 57.5 |

| Mobility | 16.0 | 33.6 | 75.0 |

| Energy | 19.4 | 10.4 | 87.3 |

| Strength | NA | 16.9 | 74.2 |

| Cognition | 6.2 | 53.3 | 52.8 |

| Mood | 51.3 | 22.0 | 71.2 |

MUNS: Montreal Unmet Needs Study; CSHA: Canadian Study of Health and Aging; SIPA: Integrated Services for Older Persons; SD: Standard deviation; NA: Not available.

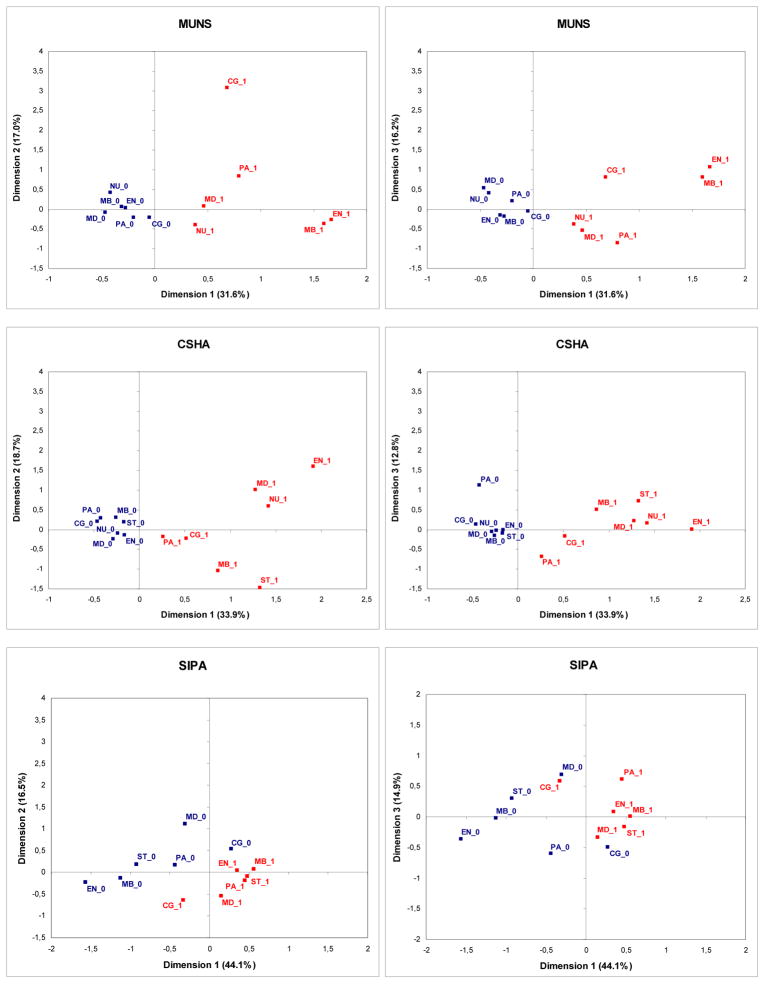

Three main dimensions were identified in each study. The proportion of inertia explained by Dimensions 1, 2 and 3 was 64.8% in MUNS, 65.4% in CSHA and 75.5% in SIPA. Figure 1 presents the results among the disability-free participants. In MUNS and the CSHA, there was complete separation between presence and absence of deficits on either side of Dimension 1. This suggests that the most important difference in the samples was between having frailty markers and not, indicating a positive correlation between these domains. However, cognition was only weakly associated with the other domains in MUNS, as seen by the relatively wide angle between cognition and the others in Figure 1. This weak association was also supported by the low tetrachoric correlation coefficients (TCCs) ranging from −0.05 to 0.14 for the correlation between cognition and the other domains (Table 3). In SIPA, cognition did not separate to the same side as the other domains. Indeed, its correlation with the other domains was found to be negligible and in some cases negative (TCCs = −0.25 to 0.00).

Figure 1. Relationship among the frailty domain variables across the three studies -Results of the multiple correspondence analysis.

MUNS: Montreal Unmet Needs Study; CSHA: Canadian Study of Health and Aging; SIPA: Integrated Services for Older Persons; NU: Nutrition, PA: Physical Activity, MB: Mobility, ST: Strength, EN: Energy, CG: Cognition, MD: Mood; Suffix 1 = presence of deficit; Suffix 0 = absence of deficit; Percentages for each axis correspond to proportion of explained inertia in each dimension.

Table 3.

Tetrachoric correlation coefficients for the seven frailty domains by study

| Study | Domain | Nutrition | Physical activity | Mobility | Strength | Energy | Cognition | Mood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| MUNS | Nutrition | 1.00 | ||||||

| Physical activity | 0.10 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Mobility | 0.14 | 0.20 | 1.00 | |||||

| Strength | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Energy | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.57 | NA | 1.00 | |||

| Cognition | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.10 | NA | 0.10 | 1.00 | ||

| Mood | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.25 | NA | 0.22 | 0.08 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||||||

| CSHA | Nutrition | 1.00 | ||||||

| Physical activity | 0.21 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Mobility | 0.20 | 0.28 | 1.00 | |||||

| Strength | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 1.00 | ||||

| Energy | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 1.00 | |||

| Cognition | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 1.00 | ||

| Mood | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||||||

| SIPA | Nutrition | NA | ||||||

| Physical activity | NA | 1.00 | ||||||

| Mobility | NA | 0.32 | 1.00 | |||||

| Strength | NA | 0.18 | 0.60 | 1.00 | ||||

| Energy | NA | 0.43 | 0.72 | 0.48 | 1.00 | |||

| Cognition | NA | −0.03 | −0.25 | −0.15 | −0.23 | 1.00 | ||

| Mood | NA | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

MUNS: Montreal Unmet Needs Study; CSHA: Canadian Study of Health and Aging; SIPA: Integrated Services for Older Persons; NA: Not available.

Table 4 presents the dimensionality and clustering of domains across the three studies. Frailty domains enumerated on the same line for a given dimension indicate a moderate to high correlation and clustering of these domains on the graph. In MUNS, separation of presence from absence of deficits in energy and mobility appears to be the most important in explaining the deviation from independence in this sample given their strong representation on Dimension 1. Moreover, these two domains form a close cluster on the graph (TCC=0.57). Cognition and, to a lesser degree, nutrition load best onto Dimension 2 but are almost 90 degrees apart from the origin indicating a weak relationship (TCC=−0.05). Physical activity and, to a lesser extent, mood are best represented on Dimension 3 and are moderately correlated (TCC=0.22). In CSHA, Dimension 1 is mainly characterized by mood, nutrition and energy, which cluster closely together in the upper right quadrant. (TCC=0.44 to 0.62). Cognition does not contribute much information given its relatively low loading on all three dimensions, although slightly higher on Dimension 1. Along Dimension 2, mobility and strength have the most importance and also form a cluster (TCC=0.59). Physical activity seems to form a separate dimension, loading on Dimension 3. In SIPA, energy, mobility and strength are most important on Dimension 1 and cluster very closely on the graph given their strong correlation (TCC=0.48 to 0.72). Physical activity, although close to energy, mobility and strength on Dimension 1, had a slightly higher contribution on Dimension 3. Cognition and mood were well represented on Dimension 2 and Dimension 3 but were strongest on Dimension 2. These two domains, however, did not cluster on the graph and were not correlated (TCC=0.00).

Table 4.

Comparison of dimensionality and clustering of domains

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| MUNS | Energy, mobility | Nutrition | Physical activity |

| Cognition | Mood | ||

|

| |||

| CSHA | Nutrition, energy, mood | Mobility, strength | Physical activity |

| Cognition | |||

|

| |||

| SIPA | Mobility, strength, energy | Cognition | Physical activity |

| Mood | |||

Frailty domains enumerated on the same line for a given dimension indicate a moderate to high correlation and clustering of these domains on the graph.

MUNS: Montreal Unmet Needs Study; CSHA: Canadian Study of Health and Aging; SIPA: Integrated Services for Older Persons;

Findings using all subjects in each study (i.e. including those with ADL disability) were similar, with minor variations in coordinates of responses on the graph. In SIPA, where the proportion with ADL disability was highest, using the full sample sometimes resulted in a different assignment of dimensionality for domains which contributed to more than one dimension, e.g. in SIPA, physical activity loaded on both Dimension 1 and 3 but was slightly higher on Dimension 1 (results not shown). When adding age, sex and disability to the analysis using all subjects, the presence of frailty deficits was found, in all three studies, to be associated with older age, female sex and the presence of disability. The most important separation in relation to age was between participants under 85 and those 85 and over, the latter being associated with the presence of deficits.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly investigate the relationships among frailty domains. The replication of the methodology in samples from three elderly target populations allowed us to assess the consistency of the findings.

If the proposed frailty domains aggregate as a syndrome, a necessary although not sufficient condition is that the presence of deficits in all domains aggregate together on the same side of Dimension 1 on the correspondence analysis graph, separated from the absence of deficits on the other side of Dimension 1. This complete separation of presence from absence of deficits across all domains occurred in the MUNS and CSHA studies, although the aggregation of cognition with the other domains was weak in MUNS. In SIPA, there was separation in all domains except cognition. In all three studies, MCA produced very similar results whether or not we included participants with ADL disability, indicating that the findings were not affected by underlying disability. As expected, a positive correlation was also found between the presence of frailty deficits and older age, female sex and the presence of disability. With the possible exception of cognition, these results support the necessary condition required to suggest that there is commonality among these domains which may be capable of distinguishing frail from non-frail individuals.

The inconsistency in the association between cognition and the other domains may imply that cognition is not a domain of frailty. Alternatively it may be that frailty involves specific aspects of cognition not measured in the three studies, such as executive function or psychomotor speed [2, 15, 19], rather than overall impairment. It should also be noted that the analysis of the relationship of cognition with other domains in MUNS was limited since only 6% of subjects were classified as having cognitive deficits as a result of the study inclusion criteria.

Dimensionality and clustering of domains varied in three studies. The degree of clustering differed according to the prevalence of frailty deficits. In SIPA, where the average number of frailty deficits was high, deficits across domains clustered tightly together and were strongly correlated. By contrast, in MUNS, where participants had few frailty deficits, points representing deficits were more dispersed and at most moderately correlated. In CSHA, the degree of clustering was intermediate. Despite differences in sample characteristics and frailty domain measures in the three studies, some similarities were detected. The most consistent feature appeared to be the clustering of mobility with energy and/or strength in all three samples. Cognition seemed to cluster poorly with the other domains although found on a common dimension with mood or nutrition. Physical activity was consistently found on Dimension 3, either alone or with mood. Although exploratory, these findings may reflect different pathways or subdimensions of frailty or redundancy in the domains clustering on a common dimension.

Our study shares the limitations of all other studies on frailty to date that have also been based on secondary analyses of existing databases. Measures were selected based on how closely they operationalized the domain as well as on their validity and clinical relevance. It remains unclear what the most appropriate measures of these domains are. Although we selected measures which did not also measure disability as defined by Katz [16], certain measures such as the ability to walk up and down the stairs have been classified by some as a functional limitation or mobility disability [20].

Our decision to dichotomize our domain variables, while required to facilitate the interpretation of results, did result in loss of information. The absence of a measure of nutrition in SIPA and strength in MUNS may also have influenced the relationships among the other domains. As with all multivariate techniques, only a subset of the total number of dimensions corresponding to the most salient features in the data was retained for interpretation. Findings regarding the dimensionality of domains may have varied with the inclusion of additional dimensions. Finally, while the statistical analysis employed a rigorous imputation method for missing data, the results may have differed had complete data been available.

This study also has important strengths. This is the first study to provide insight into the relationships among potential frailty domains. A standardized methodological approach was used to allow comparison of results from the three studies. All studies had fairly large sample sizes, together totalling more than 3,500 seniors. To illustrate the relationships among the candidate frailty domains, we used Multiple Correspondence Analysis. MCA is designed specifically for the analysis of categorical variables and is particularly advantageous for analyzing nominal variables. MCA can be useful for epidemiologists to include in their array of statistical tools as it provides an ‘all-in-one’ graphical overview of the relationship between variable response categories. Indeed, some researchers have used MCA as the primary analysis to answer their research question [21, 22] or as a guide to building statistical models such as in log-linear analysis [23, 24]. By virtue of having a better understanding of the data and study population, results of MCA can assist researchers by providing valuable insights that can guide subsequent analyses and the interpretation of results.

In conclusion, our results showed aggregation of presence of frailty deficits for all domains and in all three studies with the exception of cognition in one study. These results support the necessary although not sufficient condition that these domains belong as part of a common underlying construct, possibly capable of distinguishing frail from non-frail individuals. In all three studies, frailty domains were best represented using three dimensions. Dimensionality and clustering of domains differed across the studies although the clustering of mobility with energy and/or strength was consistent. This exploratory study is the first phase as part of the International Database Inquiry on Frailty (FrData), where the methodology will be replicated using 11 additional databases from 8 different countries in order to investigate the consistency of the findings in other study populations. The ability of the frailty domains to predict adverse outcomes will also be examined.

What is new?

Key finding

Our results suggest that the proposed domains of frailty (nutrition, physical activity, mobility, strength, energy, cognition, and mood), with the possible exception of cognition, appear to aggregate together and are multidimensional.

What this adds to what was known

Much debate still exists over the characteristics of frailty. While some studies have reported on the predictive validity of various frailty definitions, there has been little research exploring the relationship among individual frailty characteristics.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly elucidate the relationships among potential frailty characteristics.

What is the implication, what should change now

More research is needed to explore the relationships between these seven proposed domains of frailty and the presence of possible subgroups of frailty.

This exploratory study is the first phase of a larger study, the International Database Inquiry on Frailty (FrData), where the methodology will be replicated using data from 11 different studies to investigate the consistency of the findings in other populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Russell Steele for his statistical expertise in multiple imputation. Sources of funding include the Solidage Research Group and Dr. Joseph Kaufmann Chair in Geriatric Medicine, McGill University; Canadian Initiative on Frailty and Aging; Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) International Opportunity Program Development Grant 68739; CIHR team grant in frailty and aging 82945; Johns Hopkins Older Americans Independence Center (National Institutes of Health award P50AG-021334-01).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Hogan DB, MacKnight C, Bergman H. Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003 Jun;15(3 Suppl):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman H, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J, Hogan DB, Hummel S, Karunananthan S, et al. Frailty: an emerging research and clinical paradigm--issues and controversies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007 Jul;62(7):731–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 Mar;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, Aragaki A, Cochrane BB, Brunner RL, et al. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Aug;53(8):1321–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Balfour JL, Higby HR, Kaplan GA. Antecedents of frailty over three decades in an older cohort. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998 Jan;53(1):S9–16. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.s9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin APM, Dekker JM, Feskens EJ, Schouten EG, Kromhout D. How to select a frail elderly population? A comparison of three working definitions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999 Nov;52(11):1015–21. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puts MT, Lips P, Deeg DJ. Static and dynamic measures of frailty predicted decline in performance-based and self-reported physical functioning. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Nov;58(11):1188–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitnitski A, Song X, Skoog I, Broe GA, Cox JL, Grunfeld E, et al. Relative fitness and frailty of elderly men and women in developed countries and their relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Dec;53(12):2184–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, Walston J, Guralnik JM, Chaves P, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006 Mar;61(3):262–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quail JM, Addona V, Wolfson C, Podoba JE, Levésque LY, Dupuis J. Association of unmet need with self-rated health in a community dwelling cohort of disabled seniors aged 75 and over. Eur J Ageing. 2007 Mar;4(1):45–55. doi: 10.1007/s10433-007-0042-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. CMAJ. 1994;150:899–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Clarfield AM, Tousignant P, Contandriopoulos AP, et al. A system of integrated care for older persons with disabilities in Canada: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006 Apr;61(4):367–73. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman H. The Canadian Initiative on Frailty and Aging. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15(3 Suppl):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, Fried LP, Cutler GB, Jr, Walston JD, et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. [Review] [70 refs] J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Apr;52(4):625–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Studenski S, Hayes RP, Leibowitz RQ, Bode R, Lavery L, Walston J, et al. Clinical Global Impression of Change in Physical Frailty: development of a measure based on clinical judgment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Sep;52(9):1560–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;(31):721–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: J. Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Frailty is associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in the elderly. Psychosom Med. 2007 Jun;69(5):483–9. doi: 10.1097/psy.0b013e318068de1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verbrugge LM. Flies without wings. In: Carey J, Robine JM, Michel JP, Christen Y, editors. Longevity and Frailty. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2005. pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakker BFM. A new measure of social status for men and women: The social distance scale. Netherlands J Soc Sci. 1993;29:113–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton ML, Greenberger E, Hayward C. Mapping the ethnic landscape: Personal beliefs about own group’s and other groups’ traits. Cross-Cult Res. 2005;39:351–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Heijden PGM, de Leeuw J. Correspondence analysis used complementary to loglinear analysis. Psychometrika. 1985;50:429–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C. Interpretation of Epidemiological Data Using Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Log-linear Models. Journal of Data Science. 2004;2:75–86. [Google Scholar]