Abstract

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is a severe idiosyncratic drug reaction with a long latency period. It has been described using many terms; however, drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome appears to be the most appropriate. This syndrome causes a diverse array of clinical symptoms, anywhere from 2 to 8 weeks after initiating the offending drug. Standardized criteria for the diagnosis have been developed; however, their utility remains to be validated. Unfortunately, the management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is not well supported by strong evidence-based data.

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is a distinct, severe, idiosyncratic reaction to a drug characterized by a prolonged latency period. It is followed by a variety of clinical manifestations, usually fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia, and a wide range of mild-to-severe systemic presentations.

EVOLVING NOMENCLATURE

The introduction of new drugs led to a wide range of systemic and cutaneous reactions. When hydantoin was introduced in the 1940s, reports of lymphadenopathy (LAP) soon followed.1 The lymph node biopsies in these cases demonstrated a lymphomatous appearance, which was termed drug-induced pseudolymphoma by Satlztein.2 This was followed by the introduction of another anticonvulsant drug, carbamazepine, which induced a reaction consisting of a rash, fever, and LAP. Such a reaction was termed anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS).3 Shortly thereafter, multiple drugs with a similar range of manifestations were observed. Hence the term drug-induced hypersensitivity (DIHS), also known as hypersensitivity syndrome (HSS), was coined. The term DRESS was introduced by Bocquet et al4 and was based on the observation of Callot et al5 who, in 1996, reported a series of 24 patients. Three of these patients had no constitutional symptoms and only pseudolymphomatous pathology, while the remaining 21 patients developed an acute systemic illness with eosinophilia. The “R” in DRESS was changed from rash to reaction due to its diverse cutaneous presentations. Furthermore, the term drug-induced delayed multiorgan hypersensitivity syndrome (DIDMOHS) was coined by Sontheimer6 to address this condition. All of these different terms add to the confusion in understanding and diagnosing this condition. A consensus should standardize the diagnosis and management of what the authors refer to as DRESS syndrome in this article.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome is not well understood and is hypothesized to consist of a complex interaction between two or more of the following:

A genetic deficiency of detoxifying enzymes leading to an accumulation of drug metabolites. The metabolites covalently bind to cell macromolecules causing cell death or inducing secondary immunological phenomena. Eosinophilic activation as well as activation of the inflammatory cascade may be induced by interleukin-5 release from drug-specific T-cells.7

Genetic associations between human leukocyte antigen (HLA) associations and drug hypersensitivity may occur. These include HLA-B*1502, associated with carbamazepine (CBZ)-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)8; HLA-B*1508, associated with allopurinol induced SJS/TEN9; and many others.10-13 It was also observed that the association of HLA-B*1502 and CBZ-induced SJS/TEN could be ethnicity-specific as observed in Chinese populations.14,15 Furthermore, the association of CBZ-induced drug hypersensitivity reactions seems to be phenotype-specific.9

A possible virus-drug interaction associated with viral reactivation may also exist. This phenomenon has been previously observed for herpes viruses (notably Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]).16 The clinical manifestations appear to be a result of an expansion of virus-specific and nonspecific T cells. In fact, drug-specific T-cells have been isolated from the blood and skin of patients in whom DRESS syndrome was induced by lamotrigine and CBZ.17-19 Shiohara et al20 reviewed the latest evidence regarding the association of viral infections and drug rashes as well as the mechanisms of how viral infections can induce drug rashes. They observed that sequential reactivations of several herpes viruses (HHV-6, HHV-7, EBV, and cytomegalovirus) can be detected coincident with the clinical symptoms of drug hypersensitivity reactions.20 The pattern of the herpes virus re-activation was noted to be similar to that observed in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD),21,22 thus suggesting that DRESS may resemble GVHD in the sense that antiviral T-cells can cross-react with the drugs and do not only arise from the oligoclonal expansion of drug-specific T-cells. Kano et aFReview due also studied whether immunosuppressive conditions that allow HHV-6 reactivation could be specifically detected in the setting of anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS). In order to test this idea, they performed serological tests for antibody titers for various viruses and found that serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels and circulating B-cell counts in patients with AHS were significantly decreased at onset compared with control groups (P<0.001 andP=0.007, respectively). These alterations returned to normal levels on the patient’s recovery. Additionally they observed that the reactivation of HHV-6 measured by a greater than fourfold increase in HHV-6 IgG titers was exclusively detected in patients with AHS who had decreased IgG levels and B-cell counts. These findings suggest an association between the severity of AHS and possibly DRESS syndrome.

CLINICAL FEATURES

DRESS syndrome is a complex syndrome with a broad spectrum of clinical features. The clinical manifestations are not immediate and usually appear 2 to 8 weeks after introduction of the triggering drug.23 Common features consist of fever, rash, LAP, hematological findings (eosinophilia, leukocytosis, etc.), and abnormal liver function tests, which can mimick viral hepatitis. The cutaneous manifestations typically consist of an urticarial, maculopapular eruption and, in some instances, vesicles, bullae, pustules, purpura, target lesions, facial edema, cheilitis, and erythroderma (Figures 1, 2).22,24 Visceral involvement (hepatitis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, nephritis, and colitis) is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in this syndrome.4,25 Many cases are associated with leukocytosis with eosinophilia (90%) and/or mononucleosis (40%).5

Figures 1A and 1B.

Erythematous scaly patch with papules on forearm (A). Desquamation of soles. Upon closer inspection, petechiae were visible (B).

Reproduced with the permission from The Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.37

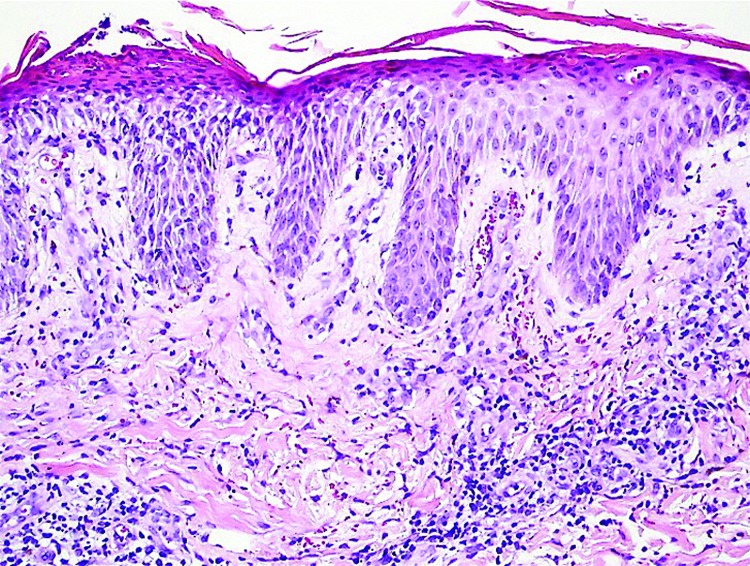

Figure 2.

Parakeratosis, intracorneal neutrophilic pustule, spongiosis, and mixed perivascular infiltrate (Hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification: ×200.)

Reproduced with the permission from The Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.37

The life-threatening potential of DRESS syndrome is high and the mortality is estimated to be around 10 percent in multiple studies.24,26 Antiepileptic medications, such as phenytoin and Phenobarbital, are thought to be the predominant cause of DRESS syndrome with an incidence of 1 per 5,000 to 10,000 exposures.27

Peyriere et al22 investigated the marked variability in the clinical patterns of cutaneous and systemic manifestations of DRESS syndrome in 2006. Their goal was to better define the relationship of the clinical features with the instigating medications.22 In their retrospective study, 216 cases of drug-induced cutaneous side effects with systemic symptoms were investigated between 1985 and 2000. They compared these records with reports from the literature for the potential DRESS syndrome-inducing drugs. The patients who had febrile skin eruptions accompanied by eosinophilia and/or systemic symptoms occurred during treatment with anticonvulsants, minocycline, allopurinol, abacavir, or nevirapine. The only feature that was found to be consistently present was a 2- to 6-week latency period for carbamazepine. Cutaneous findings were present in the majority of cases (70-100%). However, a wide variety of cutaneous findings were observed; notably, diffuse maculopapular inflammatory reactions (most common), erythroderma, SJS/TEN, erythema multiforme (EM), and pruritic eruptions. Eosinophilia was the most frequently occurring hematological abnormality (>50% of the cases). Other hematological abnormalities observed were thrombocytopenia, anemia, neutropenia, and the presence of large, activated lymphocytes (atypical lymphocytes). LAP was present in a majority (80%) of the cases involving minocycline, while it was a rare finding in cases where other drugs were used. Hepatic involvement in the form of hepatocellular necrosis was the most common visceral abnormality; however, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea were noted with abacavir. Renal dysfunction (mostly proteinuria) was observed most often with allopurinol. Minocycline (eosinophilic pneumopathy, 33% of cases) and abacavir (tachypnea, cough, and pharyngitis) were the drugs associated with lung involvement. It was speculated that the different symptoms associated with each drug were in some way related to the degree of chemical specificity to each drug itself or to its reactive metabolites. It was clear from the study that data from the Peyriere et al study and the literature were similar.22 Although no clear relationships could be established, some general trends were noted, which have been listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Drugs and their constellation of manifestations observed as DRESS syndrome22

| NAME OF DRUG | CONSTELLATION OF MANIFESTATIONS OBSERVED |

|---|---|

| Lamotrigine | Fever and toxic epidermal necrosis |

| Allopurinol | Dysfunction and eosinophilia without fever appearing several months after the start of treatment |

| Minocycline | Peripheral adenopathies, eosinophilia, heart abnormalities, and eosinophilic pneumopathy |

| Abacavir | Gastrointestinal and acute viral pneumonia-like symptoms of rapid occurrence after the introduction of treatment |

Following this study, other retrospective analyses were conducted in 60 patients in Taiwan by Chen et al,28 38 cases in Korea by Um et al,29 30 cases in another study in Taiwan by Chiou et al,26 and 15 patients in France by Eshki et al24 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

(continued). Retrospective analyses detailing patient characteristics

| SKIN MANIFESTATIONS | OTHER SIGNS/SYMP- TOMS AND CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS | HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS | LABORATORY FINDING | MORTALITY | SEQUELAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

17 had skin biopsy

|

|

10% |

|

| Not described |

|

Not described |

|

10% | Discussed under treatments |

|

|

8 skin biopsies done:

|

|

10% |

|

| Erythroderma and facial edema | Not quantified— hepatitis, pneumonitis, renal failure, hemophagocytic syndrome, encephalitis | Not described |

|

20% | Death—3 patients |

CBZ=Carbamazepine; CTS=corticosteroids; IVIG=intravenous immunoglobulin; EM= erythema multiforme; DM=Diabetes mellitus

TABLE 2.

Retrospective analyses detailing patient characteristics

| STUDY (LOCATION AND YEAR) | NUMBER OF PATIENTS (TIME PERIOD WHERE PATIENTS WILL BE ENROLLED) | MOST COMMON CAUSATIVE DRUGS | LATENCY PERIOD RANGE (MEAN) IN DAYS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al (Taiwan 2010)28 | 38 (18 men and 20 women) March 2004–January 2009 |

|

3–76 (20.7) |

|

| Um et al (Korea 2010)29 | 60 (26 men and 34 women) June 1998–May 2008 |

|

3–105 (25.2) |

|

| Chiou et al (Taiwan 2008)26 | 30 (15 men and 15 women) Jan 2001–June 2006 |

|

3–60 (23.49) |

|

| Eshki et al (France 2009)24 | 15 (5 men and 10 women) Jan 1995–Dec 2006 |

|

5–95 (18) |

|

CBZ=Carbamazepine; CTS=corticosteroids; IVIG=intravenous immunoglobulin; EM= erythema multiforme; DM=Diabetes mellitus

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome is mainly clinical and one must consider the latency period, diversity of symptoms, and exclusion of similar non-drug-induced conditions. Multiple diagnostic criteria have been developed and used in order to standardize the diagnosis and management of DRESS, albeit with limited success. The RegiSCAR group suggested criteria for hospitalized patients with a drug rash to diagnose DRESS syndrome (Table 3).24 A Japanese group suggested another set of diagnostic criteria, which includes HHV-6 activation (Table 4).30

TABLE 3.

RegiSCAR criteria for diagnosis of DRESS24

| Hospitalization |

| Reaction suspected to be drug-related |

| Acute rash |

| Fever >38°C* |

| Enlarged lymph nodes at a minimum of 2 sites* |

| Involvement of at least 1 internal organ* |

| Blood count abnormalities* |

| Lymphocytes above or below normal limits |

| Eosinophils above the laboratory limits |

| Platelets below the laboratory limits |

Three out of four asterisked (*) criteria are required for making the diagnosis.

TABLE 4.

Japanese group’s criteria for diagnosis of DRESS/DIHS30

| Maculopapular rash developing >3 weeks after starting with the suspected drug |

| Prolonged clinical symptoms 2 weeks after discontinuation of the suspected drug |

| Fever >38°C |

| Liver abnormalities (alanine aminotransferase>100U/L) |

| Leucocyte abnormalities |

| Leucocytosis (>11 X 109/L) |

| Atypical lymphocytosis (>5%) |

| Eosinophilia (>1.5 x 109 /L) |

| Lymphadenopathy |

| Human Herpes 6 reactivation |

The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of the 7 criteria (typical DHS).

Certain diagnostic tools have been tried to predict the possibility of DRESS in certain patients. Rechallenging with the suspected drug is considered the gold standard for drug eruptions; however, it cannot be used to confirm the culprit drug for DRESS due to the possible life-threatening consequences. Unfortunately, the lymphocyte transformation/activation test is not standardized for most drugs, it is difficult to perform, has low sensitivity and specificity, and was found to be negative during the acute phase of DRESS syndrome.31

In an attempt to identify a more effective diagnostic test, Santiago et al32 evaluated the safety and usefulness of patch testing in DRESS, thus attempting to identify a drug-dependent delayed hypersensitivity mechanism. A positive patch test reaction was observed in 18 out of 56 patients (32.1%) (17 with antiepileptics and 1 with tenoxicam). In the antiepileptics group, CBZ alone was responsible for 13 of 17 positive reactions (76.5%). Patch tests with allopurinol and its metabolite were negative in all cases attributed to this drug. It was concluded that patch testing is a safe and useful method in confirming the culprit drug in DRESS induced by antiepileptic drugs, but it had no value in DRESS induced by allopurinol.

The high sensitivity/specificity of some genetic markers provides a plausible basis for the future development of tests to identify individuals at risk for drug hypersensitivity. Genotyping for HLA markers can be used as a screening tool before prescribing such drugs and can therefore prevent DRESS occurrences in specific populations.

MANAGEMENT

DRESS syndrome must be recognized promptly and the causative drug withdrawn. Indeed, it has been reported that the earlier the drug withdrawal, the better the prognosis.32 Treatment is largely supportive and symptomatic; corticosteroids are often used, but the evidence regarding their effectiveness is scant.34 Other immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporin, may also be required.35,36

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE:The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coope R, Burrows R. Treatment of epilepsy with sodium diphenyl hydantoine. Lancet. 1940;1:490–492. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saltzstein SL, Ackerman LV. Lymphadenopathy induced by anticonvulsant drugs and mimicking clinically pathologically malignant lymphomas. Cancer. 1959;12:164–182. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195901/02)12:1<164::aid-cncr2820120122>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vittorio CC, Muglia JJ. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2285–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms: DRESS) Semin Gutan Med Surg. 1996;15:250–257. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callot V, Roujeau JC, Bagot M, et al. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and hypersensitivity syndrome. Two different clinical entities. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1315–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sontheimer RD, Houpt KR. DIDMOHS: a proposed consensus nomenclature for the drug-induced delayed multiorgan hypersensitivity syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:874–876. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.7.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choquet-Kastylevsky G, Intrator L, Chenal C, et al. Increased levels of interleukin 5 are associated with the generation of eosinophilia in drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1026–1032. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, et al. Medical genetics: a marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Nature. 2004;428:486. doi: 10.1038/428486a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, et al. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Set USA. 2005;102:4134–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman JA, Yunis J, Egea E, et al. HLA-B38, DR4, DQw3 and clozapine-induced agranulocytosis in Jewish patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:945–948. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810220061007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlahov V, Bacracheva N, Tontcheva D, et al. Genetic factors and risk of agranulocytosis from metamizol. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:67–72. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199602000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diez RA. HLA-B27 and agranulocytosis by levamisole. Immunol Today. 1990;11:270. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90109-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Perez M, Gonzalez-Dominguez J, Mataran L, et al. Association of HLA-DR5 with mucocutaneous lesions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving gold sodium thiomalate. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung SI, Chung WH, Jee SH, et al. Genetic susceptibility to carbamazepine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:297–306. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000199500.46842.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonjou C, Thomas L, Borot N, et al. A marker for Stevens- Johnson syndrome: ethnicity matters. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:265–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kano Y, Shiohara T. Sequential reactivation of herpesvirus in drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Acta Derm Venereal, 2004;84:484–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles SR, Uetrecht J, Shear NH. Idiosyncratic drug reactions: the reactive metabolite syndromes. Lancet. 2000;356:1587–1591. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naisbitt DJ, Farrell J, Wong G, et al. Characterization of drug-specific T cells in lamotrigine hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1393–1403. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naisbitt DJ, Britschgi M, Wong G, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to carbamazepine: characterization of the specificity, phenotype, and cytokine profile of drug-specific T cell clones. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:732–741. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiohara T, Kano Y. A complex interaction between drug allergy and viral infection. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2007;33:124–133. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaia JA. Viral infections associated with bone marrow transplantation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1990;4:603–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peyriere H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rzany B, Correia O, Kelly JP, et al. Risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis during first weeks of antiepileptic therapy: a case-control study. Study Group of the International Case Control Study on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions. Lancet. 1999;353:2190–2194. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eshki M, AUanore L, Musette P, et al. Twelve-year analysis of severe cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a cause of unpredictable multiorgan failure. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:67–72. doi: 10.1001/archderm.145.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eland IA, Dofferhoff AS, Vink R, et al. Colitis may be part of the antiepileptic drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1780–1783. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiou CC, Yang LC, Hung SI, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a study of 30 cases in Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereal, 2008;22:1044–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tennis P, Stern RS. Risk of serious cutaneous disorders after initiation of use of phenytoin, carbamazepine, or sodium valproate: a record linkage study. Neurology. 1997;49:542–546. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YC, Chiu HC, Chu CY. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1373–1379. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Um SJ, Lee SK, Kim YH, et al. Clinical features of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in 38 patients. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20:556–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, Hashimoto K. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1083–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kano Y, Hirahara K, Mitsuyama Y, et al. Utility of the lymphocyte transformation test in the diagnosis of drug sensitivity: dependence on its timing and the type of drug eruption. Allergy. 2007;62:1439–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santiago F, Goncalo M, Vieira R, et al. Epicutaneous patch testing in drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS) Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Doval I, LeCleach L, Bocquet H, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:323–327. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1272–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuliani E, Zwahlen H, Gilliet F, Marone C. Vancomycin-induced hypersensitivity reaction with acute renal failure: resolution following cyclosporine treatment. Clin Nephrol. 2005;64:155–158. doi: 10.5414/cnp64155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harman KE, Morris SD, Higgins EM. Persistent anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome responding to ciclosporin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:364–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaughnessy KK, Bouchard SM, Mohr MR, et al. Minocycline-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome with persistent myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]