Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the impact of methadone dose on post-release retention in treatment among HIV-infected prisoners initiating methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) within prison.

Methods

Thirty HIV-infected prisoners meeting DSM-IV pre-incarceration criteria for opioid dependence were enrolled in a prison-based, pre-release MMT program in Klang Valley, Malaysia; 3 died before release from prison leaving 27 evaluable participants. Beginning 4 months before release, standardized methadone initiation and dose escalation procedures began with 5mg daily for the first week and 5mg/daily increases weekly until 80 mg/day or craving was satisfied. Participants were followed for 12 months post-release at a MMT clinic within 25 kilometers of the prison. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate the impact of methadone dose on post-release retention in treatment.

Findings

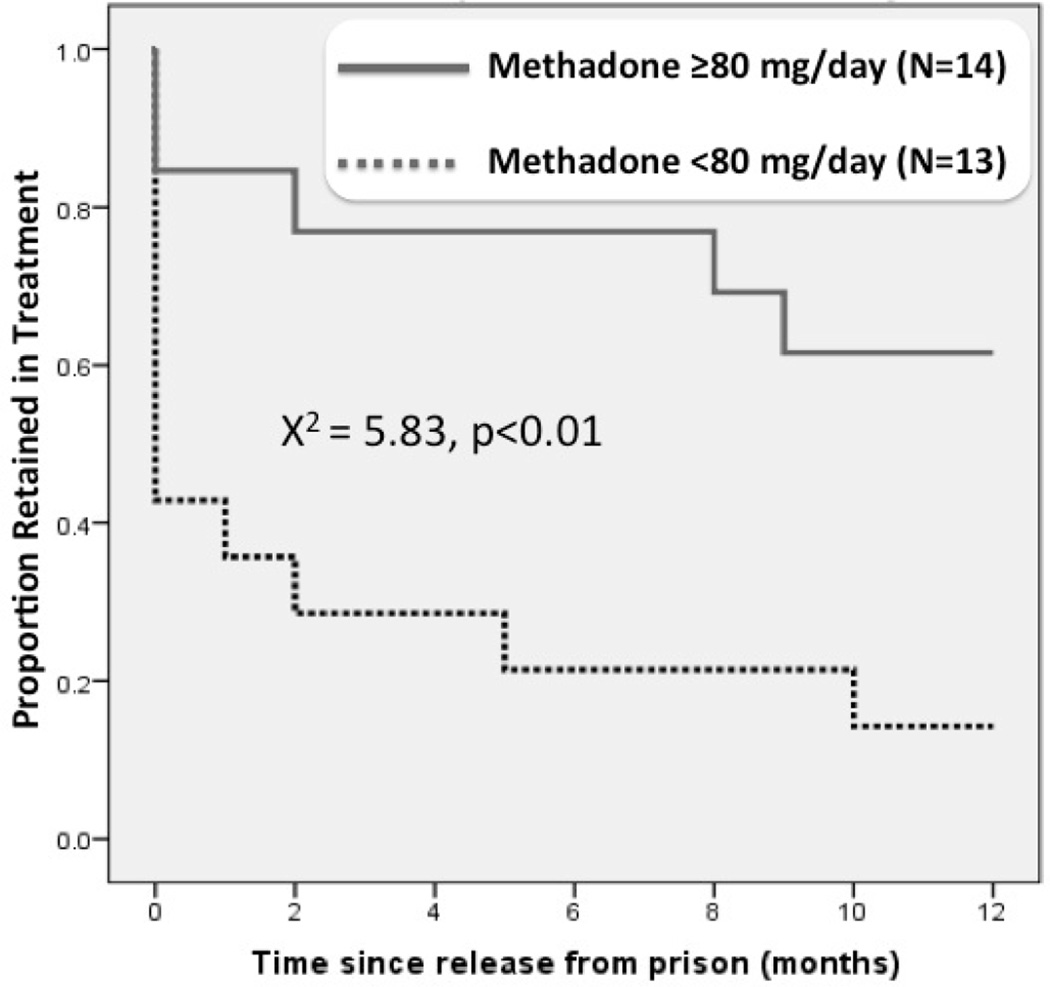

Methadone dose ≥80 mg/day at the time of release was significantly associated with retention in treatment. After 12 months of release, only 21.4% of participants on <80mg were retained at 12 months compared to 61.5% of those on ≥80mg (Log Rank χ2=(1,26) 7.6, p <0.01).

Conclusions

Higher doses of MMT at time of release are associated with greater retention on MMT after release to the community. Important attention should be given to monitoring and optimizing MMT doses to address cravings and side effects prior to community re-entry from prisons.

Keywords: Prisoners, Malaysia, Opioid Dependence, Methadone, Retention in Care, Craving

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, people who inject drugs (PWIDs) continue to contribute greatly to HIV transmission (Mathers et al., 2008). The intertwined epidemics of HIV and drug injection are especially salient in the countries of Southeast Asia, especially Malaysia (Kamarulzaman, 2009; Todd et al., 2007). It is estimated that 1.3% of all adult Malaysians are PWIDs, of which 11% are HIV-infected (UNAIDS, 2009). The epidemic of HIV among PWIDs is further complicated by government policies that criminalize drug use, systematically favoring incarceration over rehabilitation.

In Malaysia, nearly two thirds of newly diagnosed HIV infections are among PWIDs, the highest such prevalence in the region (Malaysian AIDS Council, 2010; World Health Organization, 2004). Among HIV-infected populations, PWIDs have persistently poorer health outcomes compared to their non-drug using counterparts primarily because they are less likely to access routine health care, be prescribed and adhere to combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), and be provided with medication-assisted therapy (MAT) for drug dependence (Altice et al., 2010; Oppenheimer et al., 2003; Wolfe et al., 2010).

As in the United States and elsewhere, the HIV epidemic among PWIDs in Malaysia is disproportionately concentrated within the criminal justice system (CJS). Results from mandatory HIV testing of the approximately 40,000 prisoners in Malaysia documents HIV prevalence to be ten to fifteen times greater (4.6% vs. 0.40%) than in the general community (Choi et al., 2010; Mathers et al., 2008). Moreover, substance use disorders are twenty to forty times greater (38% vs. 1.33%) and underlying psychiatric illness is greater than found in the general population (Zahari et al., 2010), each of which contributes to HIV transmission. Surveys among HIV-infected prisoners suggest that 97% of them meet pre-incarceration criteria for opioid dependence (Bachireddy et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2010). In the absence of evidence-based treatment, relapse to opioid injection is high after release, which underscores the importance of implementing pre-release methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) for HIV-infected PWIDs because only HIV-infected persons can transmit to others.

In 2005, Malaysia aligned its drug policies with accepted HIV treatment and prevention strategies by introducing harm reduction interventions, including syringe exchange and MMT programs. Unfortunately, due to continued criminalization of PWIDs and a relative scarcity of harm reduction initiatives in prisons (Wolfe et al., 2010), the concentration of HIV within Malaysian prisons remains unacceptably high. Moreover, upon re-entry to the community, this vulnerable population faces inordinate challenges including relapse to drug use, difficulty in finding employment, as well as the hazards of recidivism, and loss of follow-up to HIV care (Choi et al., 2010). In light of the high rates of pre-incarceration HIV-related risk behaviors and reported negative attitudes toward opioid substitution therapy among prisoners (Bachireddy et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2010), Malaysian prisoners constitute an important target for primary and secondary HIV risk reduction interventions (Bachireddy et al., 2011).

1.1 Methadone Maintenance Programs in Correctional Settings

MMT is highly effective for treating opioid dependence in both community (Schwartz et al., 2006, 2008) and prison (Dolan et al., 1998; Gorta, 1992; Hedrich et al., 2012; Howells et al., 2002; Kerr and Jurgens, 2004; Kinlock et al., 2009a) settings. After release, relapse is high and associated with high rates of overdose, criminal activity and recidivism (Hanlon et al., 1990; Nurco et al., 1991, 1990). Although MMT has been demonstrated to reduce post-release relapse to drug use, overdose and death, and improve general quality of life and employment stability, programs within CJS settings remains insufficient (Amato et al., 2005; Larney and Dolan, 2009; Mathers et al., 2010; Mattick et al., 2009). Though underutilized, CJS settings are crucial for initiating evidence-based treatment for opioid dependence (Altice et al., 2010; Springer et al., 2011). Opportunities for introducing MMT post-release quickly dwindle as relapse often occurs within two weeks and exceeds 85% within one year (Binswanger et al., 2007; Leach and Oliver, 2011; Strang et al., 2010).

As part of Malaysia’s plan to expand MMT to prisoners, we analyzed the 12-month post-release data from the country’s first prison-based pre-release MMT pilot program of HIV-infected males who met pre-incarceration criteria for opioid dependence.

2. METHODS

The first 30 HIV-infected men who met criteria and volunteered were prospectively enrolled in a prison-initiated, pre-release pilot methadone program in Kajang prison in Selangor, Malaysia between September 2009 and December 2010; women were not included in the pilot due to selection of a single site. Volunteers were recruited and consented within prison after information sessions and then meeting inclusion criteria: 1) ! 18 years of age; 2) HIV-infected; 3) pre-incarceration opioid dependence using DSM-IV criteria; 4) returning to live within 25 kilometers of the post-release MMT site; and 5) within 4 months of release from prison. To ensure safety, a research-based addiction psychiatrist assessed participants before initiating MMT using a standardized induction protocol. To avoid opioid excess, participants initially received 5 mg daily and daily doses were increased by 5 mg every 7 days; 80 mg/day was targeted, but doses were individualized based on having sufficient time to achieve the target before release and to balance cravings and side effects. Transitional MMT care included transmittal of methadone dose to the community-based MMT program, meeting clients on the day of release and transportation to the MMT program.

Three participants died in prison before release from prison (2 had tuberculosis and 1 had a seizure), resulting in 27 subjects evaluable for the retention in care outcome. Participants were assessed at baseline and monthly for 12 months. Baseline measures included the HIV Symptom Index (Justice et al., 2001), HIV-related Stigma (Berger et al., 2001), Social Support (Sherbourne and Stewart, 1991), depression using the Clinical Epidemiological Scale for Depression (CES-D) with scores ≥16 being consistent with moderate to severe depression (Radloff, 1977), self-reported chronic illnesses, and drug use characteristics. Retention was defined as not missing 14 consecutive days of methadone and lost to follow-up was coded as the last day of receipt of methadone. Survival analysis was stratified by the daily MMT dose at the time of release (<80 mg versus ≥80 mg) in order to evaluate the effect of dosing on post-release MMT retention. This stratification is based on evidence from reviews of MMT dosing (Mattick et al., 2009) and results from randomized controlled trials (Faggiano et al., 2003) that report higher methadone doses (≥80 mg) improve treatment outcomes. Institutional Review Boards at Yale University and the University of Malaya approved the study.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. Overall, the sample is similar to other studies of opioid dependent, HIV-infected prisoners in Malaysia (Bachireddy et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2010). Nearly all (96.7%) reported prior injection drug use and had been incarcerated for an average of 12.5 months before MMT initiation. Mean time since HIV diagnosis was 8.3 years and only one participant (3.3%) reported being on cART (he was also receiving treatment for tuberculosis). HIV-associated symptoms suggested high levels of depressive symptoms (46.7%), loss of appetite (46.7%), trouble with memory (36.7%), and difficulty sleeping (36.7%) and 40% met criteria for moderate to severe depression.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants (N=30)

| Variable | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| 30 (100) | |

| Ethnicity | |

| 22 (73.3) | |

| 6 (20.0) | |

| 2 (6.7) | |

| Religion | |

| 22 (73.3) | |

| 4 (13.3) | |

| 3 (10.0) | |

| 1 (3.3) | |

| Employed full time prior to prison | |

| 16 (53.3) | |

| 13 (43.3) | |

| Highest level of education completed | |

| Elementary | 5 (16.3) |

| Some Secondary | 16 (53.3) |

| Completed secondary or higher | 9 (30.0) |

| Age (years) | |

| (SD) | 7.1 (37.1) |

| Previous injection drug use | |

| 96.7 (29) | |

| 3.3 (1) | |

| Mean current incarceration time, years (S.D.) | 1.04 (0.5) |

| Mean lifetime incarceration, years (S.D.) | 6.6 (4.2) |

| Mean time since HIV diagnosis, years (S.D.) | 8.3 (6.5) |

| Depression (CES-D) | |

| or none (0–15) | 60.0 (18) |

| Moderate to Severe (16–60) | 40.0 (24) |

3.2 Survival Analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate retention on MMT (See Figure 1). The mean daily MMT dose at time of release was 90.9 mg (range=45–120mg). At the time of release, MMT dose <80mg was prescribed for 51.9% (N=14) of the sample; of note, no one received 81–99 mg leaving the remaining 13 participants receiving ≥100 mg per day. During the post-release follow-up period, there were no recorded decreases in MMT dose and mean retention was 172.5 days.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier retention curve comparing prisoners released from prison (N=27)

At 12 months, participants on ≥80mg were significantly more likely than those on lower doses to be retained [61.5% (8/13) vs 21.4% (3/14)] in treatment (Log Rank χ2=(1,26) 7.6, p <0.01). Most of the attrition occurs within one month post-release, especially for those receiving <80mg compared to higher doses [64% (9/14) vs 15.4% (1/13)].

4. DISCUSSION

This study represents one of the first published studies of HIV-infected prisoners meeting criteria for opioid dependence, receiving prison-based MMT and being released to the community in Asia. The implications for treatment, however, extend well beyond this region. Data from randomized controlled trials of MMT confirm the superiority of initiating MMT prior to release among opioid dependent prisoners with regard to a number of post-release substance abuse treatment outcomes (Kinlock et al., 2009b). In Kinlock’s study, prison-based MMT outcomes were superior to those who received vouchers for immediate referral to MMT post-release, but the retention in treatment at 12 months was only 36.7%, perhaps due to targeted daily methadone dosing being only 60 mg. Results from other international studies suggest there is considerable benefit to initiating MMT during incarceration to individuals meeting pre-incarceration opioid dependence prior to reentering the community. In a quality improvement study of MMT dosing at Rykers Island jail in New York City, increased methadone doses were associated with increased likelihood of being “linked” to post-release MMT, but doses were generally around 55 mg per day and no retention on treatment data were available (Harris et al., 2012). These conclusions are also significant as they reflect previous international findings that demonstrate the important role MMT plays in improving substance use and health-related outcomes after release (Dolan et al., 1998; Gibson et al., 2008; Kinlock et al., 2009a).

Moreover, these data confirm the need to achieve adequate methadone dosing while still incarcerated in order to optimize substance abuse treatment benefits after release and in community settings (Faggiano et al., 2003; Mattick et al., 2009). In community settings, daily doses >80 mg were associated with the highest levels of retention on treatment (Caplehorn and Bell, 1991). Although we stratified methadone at the 80 mg dose, our data, where all participants on doses greater than 80 mg per day were actually on 100 mg or more, confirm markedly higher rates of retention in community-based MMT using higher doses (Peles et al., 2006). The structure of prison settings often results in reduced, but not absent illicit drug use in prison. Such perspectives often result in the perception of needing to prescribe subtherapeutic methadone doses within prison with the primary goal to avoid withdrawal and reduce the likelihood from overdose. Such approaches, however, do not address the issue of craving which has been associated with opioid relapse (Fareed et al., 2010, 2011; Preston and Epstein, 2011). Data from this study suggest that in order to achieve optimal dosing (actual doses were ≥100 mg/day) prior to release, prison-based MMT programs should initiate methadone no later than six months before the scheduled release date (Wickersham et al., 2013). Providing this longer induction window among individuals who are not tolerant to opioids will allow medical staff to closely monitor patients during weekly dose increases, address craving and determine when optimal dosing is achieved. This approach also allows longer assessment periods of side effects, which can be addressed more immediately in the correctional setting than after release, when risk of relapse sharply increases (Kinlock et al., 2005).

While this study evaluated MMT as a pre-release intervention, it should be noted, however, that ideal programs should consider opioid dependence as a chronic, relapsing condition and MMT should optimally be provided throughout incarceration, particularly to reduce within prison-related injection, intra-prison transmission of blood-borne viruses and other negative consequences of injection (Dolan et al., 2003). Moreover, opioid substitution therapy using buprenorphine is an option, has fewer side effects than methadone, and improves both post-release HIV treatment (Springer et al., 2012) and emergency room outcomes (Meyer et al., 2012).

There are several limitations to this study. First, the relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability of findings, which reinforces the need for a large, randomized controlled trial to address the question of the optimal MMT dose and its impact on retention and relapse. Despite this limitation, even results from this small sample are compelling and reflect empirical evidence that higher MMT doses results in longer treatment retention (Faggiano et al., 2003; Kinlock et al., 2005; Peles et al., 2006).

Second, due to the pilot nature of this study and inclusion of only men, there are no insights into the unique factors that may be associated with women’s experience in pre-release MMT programs. Given the increased injection of opioids among women in Southeast Asia (Nguyen et al., 2008) and evidence that women are significantly less likely than men to enter substance abuse treatment (Greenfield et al., 2007), future studies must examine the gender-specific factors associated with key outcomes in prison-based, pre-release MMT programs. Such approaches will inevitably enhance the quality of care received by both genders by providing more customized treatments. Last, it is worthwhile examining MMT for opioid dependent prisoners not infected with HIV or HCV to examine its impact on primary prevention (Dolan et al., 2005).

5. CONCLUSIONS

Medication-assisted therapy, including MMT, is not routinely available in prison settings, but emerging data confirm its benefit in improving both substance abuse treatment (Kinlock et al., 2009b) and HIV treatment outcomes (Springer et al., 2010, 2012). In the case of methadone, it appears that the dose of methadone achieved prior to release has a profound impact on retention with higher doses resulting in prolonged treatment retention. The impact of such approaches is likely to have secondary improvements in outcomes given the high degree of medical and psychiatric morbidity and mortality that also require concomitant treatment.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse for research (R01 DA025943, Altice, PI) and career development (K24 DA017072, Altice). These funding agencies had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Authors Altice and Kamarulzaman designed the study and wrote the protocol. Authors Wickersham, Azar, and Zahari managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work. Author Wickersham undertook the statistical analysis, and authors Wickersham, Azar, and Zahari wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:59–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato L, Davoli M, Perucci CA, Ferri M, Faggiano F, Mattick RP. An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005;28:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachireddy C, Bazazi AR, Kavasery R, Govindasamy S, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Attitudes toward opioid substitution therapy and pre-incarceration HIV transmission behaviors among HIV-infected prisoners in Malaysia: implications for secondary prevention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res. Nurs. Health. 2001;24:518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, Koepsell TD. Release from prison--a high risk of death for former inmates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplehorn JR, Bell J. Methadone dosage and retention of patients in maintenance treatment. Med. J. Aust. 1991;154:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P, Kavasery R, Desai MM, Govindasamy S, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Prevalence and correlates of community re-entry challenges faced by HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2010;21:416–423. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan KA, Shearer J, MacDonald M, Mattick RP, Hall W, Wodak AD. A randomised controlled trial of methadone maintenance treatment versus wait list control in an Australian prison system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan KA, Shearer J, White B, Zhou J, Kaldor J, Wodak AD. Four-year follow-up of imprisoned male heroin users and methadone treatment: mortality, re-incarceration and hepatitis C infection. Addiction. 2005;100:820–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan KA, Wodak AD, Hall WD. Methadone maintenance treatment reduces heroin injection in New South Wales prisons. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1998;17:153–158. doi: 10.1080/09595239800186951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggiano F, Vigna-Taglianti F, Versino E, Lemma P. Methadone maintenance at different dosages for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003:CD002208. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareed A, Vayalapalli S, Casarella J, Amar R, Drexler K. Heroin anticraving medications: a systematic review. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:332–341. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.505991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareed A, Vayalapalli S, Stout S, Casarella J, Drexler K, Bailey SP. Effect of methadone maintenance treatment on heroin craving, a literature review. J. Addict. Dis. 2011;30:27–38. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.531672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson A, Degenhardt L, Mattick RP, Ali R, White J, O'Brien S. Exposure to opioid maintenance treatment reduces long-term mortality. Addiction. 2008;103:462–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorta A. Monitoring the New South Wales Methadone Program: 1986–1991. New South Wales: Department of Corrective Services; 1992. (ISSN 0813 5800) [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Hien D, Miele GM. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon TE, Nurco DN, Kinlock TW, Duszynski KR. Trends in criminal activity and drug use over an addiction career. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:223–238. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Selling D, Luther C, Hershberger J, Brittain J, Dickman S, Glick A, Lee JD. Rate of community methadone treatment reporting at jail reentry following a methadone increased dose quality improvement effort. Subst. Abuse. 2012;33:70–75. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.620479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich D, Alves P, Farrell M, Stover H, Moller L, Mayet S. The effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment in prison settings: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107:501–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells C, Allen S, Gupta J, Stillwell G, Marsden J, Farrell M. Prison based detoxification for opioid dependence: a randomised double blind controlled trial of lofexidine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, Rabeneck L, Zackin R, Sinclair G, Weissman S, Neidig J, Marcus C, Chesney M, Cohn SE, Wu AW. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. J. Clin. Epi. 2001;54:S77–S90. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarulzaman A. Impact of HIV Prevention programs on Drug Users in Malaysia. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009;52:S17–S19. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bbc9af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Jurgens R. Methadone Maintenance Therapy in Prisons: Reviewing the Evidence. Montreal: Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Battjes RJ, Schwartz RP. A novel opioid maintenance program for prisoners: report of post-release outcomes. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31:433–454. doi: 10.1081/ada-200056804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O'Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months post release. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009a;37:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O'Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months postrelease. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009b;37:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larney S, Dolan K. A literature review of international implementation of opioid substitution treatment in prisons: equivalence of care? Eur. Addict. Res. 2009;15:107–112. doi: 10.1159/000199046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach D, Oliver P. Drug-related death following release from prison: a brief review of the literature with recommendations for practice. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:292–297. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104040292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaysian AIDS Council. AIDS in Malaysia: 2010 Update. Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers B, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee S, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndall M, Toufik M, Mattick R. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372:1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Mattick RP, Myers B, Ambekar A, Strathdee SA. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375:1014–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009:CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Qiu J, Chen NE, Larkin GL, Altice FL. Emergency department use by released prisoners with HIV: an observational longitudinal study. PloS One. 2012;7:e42416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TA, Oosterhoff P, Hardon A, Tran HN, Coutinho RA, Wright P. A hidden HIV epidemic among women in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurco DN, Hanlon TE, Kinlock TW. Recent research on the relationship between illicit drug use and crime. Behav. Sci. Law. 1991;9:221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Nurco DN, Stephenson PE, Hanlon TE. Aftercare/relapse prevention and the self-help movement. Int. J. Addict. 1990;25:1179–1200. doi: 10.3109/10826089109081041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer E, Hernandez A, Stimson G. Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behaviour. England: Imperial College, London; 2003. Treatment and Care for Drug Users Living with HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Peles E, Schreiber S, Adelson M. Factors predicting retention in treatment: 10-year experience of a methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clinic in Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Epstein DH. Stress in the daily lives of cocaine and heroin users: relationship to mood, craving, relapse triggers, and cocaine use. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:29–37. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2183-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Highfield DA, Jaffe JH, Brady JV, Butler CB, Rouse CO, Callaman JM, O'Grady KE, Battjes RJ. A randomized controlled trial of interim methadone maintenance. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:102–109. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O'Grady KE, Mitchell SG, Peterson JA, Reisinger HS, Agar MH, Brown BS. Attitudes toward buprenorphine and methadone among opioid-dependent individuals. Am. J. Addict. 2008;17:396–401. doi: 10.1080/10550490802268835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS Social Support Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Chen S, Altice FL. Improved HIV and substance abuse treatment outcomes for released HIV-infected prisoners: the impact of buprenorphine treatment. J. Urban Health. 2010;87:592–602. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Qiu J, Saber-Tehrani AS, Altice FL. Retention on buprenorphine is associated with high levels of maximal viral suppression among HIV-infected opioid dependent released prisoners. PloS One. 2012;7:e38335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications of adequate transitional care for HIV-infected Prisoners: five essential components. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;53:469–479. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, Hall W, Hickman M, Bird SM. Impact of supervision of methadone consumption on deaths related to methadone overdose (1993–2008): analyses using OD4 index in England and Scotland. BMJ. 2010;341:c4851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd CS, Nassiramanesh B, Stanekzai MR, Kamarulzaman A. Emerging HIV epidemics in Muslim countries: assessment of different cultural responses to harm reduction and implications for HIV control. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:151–157. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Malaysia Country Advocacy Brief. Geneva, Switzerland: Injecting Drug Use and HIV; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wickersham JA, Marcus R, Kamarulzaman A, Zahari MM, Altice FL. Implementing prison-based methadone in Malaysia. Bull WHO. 2013 doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109132. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Annual Report: Western Pacific Regional Office. Bangkok, Thailand: HIV/AIDS in Asia and the Pacific Region; 2004. pp. 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zahari MM, Hwan Bae, W, Zainal NZ, Habil H, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidity among HIV seropositive and HIV seronegative prisoners in Malaysia. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:31–38. doi: 10.3109/00952990903544828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]