Abstract

Objective

This study examined maternal warmth as a moderator of the relation between harsh discipline practices and adolescent externalizing problems 1year later in low-income, Mexican American families.

Design

Participants were 189 adolescents and their mothers who comprised the control group of a longitudinal intervention program.

Results

Maternal warmth protected adolescents from the negative effects of harsh discipline such that, at higher levels of maternal warmth, there was no relation between harsh discipline and externalizing problems after controlling for baseline levels of externalizing problems and other covariates. At lower levels of maternal warmth, there was a positive relation between harsh discipline practices and later externalizing problems.

Conclusions

To understand the role of harsh discipline in the development of Mexican American youth outcomes, researchers must consider contextual variables that may affect youths’ perceptions of their parents’ behavior such as maternal warmth.

INTRODUCTION

Although a vast literature supports the direct, positive association between harsh discipline and externalizing behaviors, emerging theoretical and empirical evidence has challenged broad generalization of these findings by positing that harsh discipline may not have similar effects for all children (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005). Scholars have highlighted the important role of context in understanding harsh discipline's effects on youth outcomes. One contextual variable is the emotional tone of the parent-child relationship, typically operationalized as the level of warmth. Several studies have found that maternal warmth attenuates the negative impact of physical discipline on youth externalizing in African American families such that, in the context of high parent-child warmth, there is no association between physical discipline and externalizing (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Deater-Deckard, Ivy, & Petrill, 2006; McLoyd & Smith, 2002).

The role of maternal warmth as a moderator of harsh discipline's effects on externalizing has been examined with African American families residing in the United States (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Deater-Deckard et al., 2006; McLoyd & Smith, 2002) and with families from various Asian countries (Chao & Aque, 2009). However, these ideas have rarely been tested empirically among Latino families (see McLoyd & Smith, 2002, for an exception) or on adolescents in general. Some evidence suggests Latino cultural norms support the use of harsh and restrictive discipline practices (Calzada, 2007). In a cross-ethnic group study of children ages 8 to 13 years, Hill and colleagues (2003) found that Mexican American (MA) mothers engaged in higher levels of harsh discipline compared to European American mothers even after controlling for socioeconomic status (SES). There is qualitative evidence that MA parents, in an effort to teach traditional Latino cultural values rooted in interdependence such as respeto (respect) and bien educación (social responsibility), are less accepting and more critical of their children when they display inappropriate behavior (Sirolli, 2004; Valdés, 1996).

Attachment theory suggests that warm, responsive parenting is the critical factor in producing securely attached children who, in turn, develop positive secure internal working models of their parents (Thompson, 2006). Children then interpret subsequent parental behaviors, including discipline attempts, through the context of a warm and secure parent-child relationship. Mothers high on warmth demonstrate positive affect and supportive and accepting behaviors which promote a stable and global belief in the child that their parents love them (Schaefer, 1965). Deater-Deckard and Dodge (1997) suggested this stable belief buffers the child from perceiving their parents’ behavior as rejecting even when parents utilize harsh discipline in response to child misbehavior.

Although a review of empirical studies on Latino parenting concluded that parents’ use of physical and verbal punishment is associated with poor youth adjustment (as a main effect), these studies did not examine potential moderators of this relation (Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006). This study examined the role of maternal warmth as a moderator of the prospective effects of harsh discipline on later externalizing for a sample of MA adolescents and their mothers living in low-income, urban neighborhoods. Given that theoretical explanations of the buffering effects of maternal warmth on harsh discipline have typically focused on youth perceptions of parenting (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997), this study used adolescent report of parenting practices. In addition, Larzelere and Kuhn (2005) recommended using different reporters for parenting practices and child outcomes to control for the same source bias effect; thus, this study used maternal reports of adolescent externalizing.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 189 adolescents and their caregivers who comprised the control group of an intervention program, Bridges to High School. The current study utilized data from Wave 1 (beginning of 7th grade; M age = 12.3, SD = .54) and Wave 3 (end of 8th grade; M age = 13.49, SD = .54). Eighty-nine percent of the control group sample completed Wave 3. Three cohorts of families were recruited from five, low-income public schools in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Of the 189 students in the control group sample, 102 (54%) were female. The majority of adolescents resided in two-parent households (85.7%). Of the female caregivers, 33.9% were born in the United States, 65.6% were born in Mexico, and 0.5% were born in another country. There were no differences between the intervention and control groups on any demographic or study variables at Wave 1.

Procedures

Interviewers used laptop computers and conducted the caregiver and adolescent surveys in separate rooms and/or out of the hearing of other family members. The interviewers read questions and possible responses aloud in Spanish or English to reduce problems associated with literacy levels. Adolescents completed interviews in the language their family selected for the intervention, unless they were unable or requested a different language. Each family member who completed an interview received $30. Preparation of materials consisted of translating English text into Spanish, and then translating the Spanish text back into English to ensure language equivalence of all measures (Behling & Law, 2000).

Maternal warmth and harsh discipline were measured with 8 items each adapted from the Acceptance subscale of the Children's Reports of Parents’ Behavior Inventory (Schaefer, 1965). Adolescents rated how often in the last month (1=Almost never or never; 5 = Almost always or always) each statement described their thoughts or feelings about their parent. For warmth, “My caregiver told or showed me that she liked me just the way I was,” and for harsh discipline, “My caregiver spanked or slapped me when I did something wrong” and “My caregiver got so mad at me he/she called me names.” Alpha for Wave 1 youth reports were.90 and .71, respectively.

Externalizing

Externalizing was assessed by maternal report on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). Each item was answered using a 3-point Likert-type scale (e.g., Not true to Very true or often true). Coefficient alphas at Wave 1 and Wave 3 = .89.

Demographic variables

Demographic variables were used as covariates in this study. These included youth gender, mother and youth nativity, family structure (1- versus 2- parent family) and SES. SES was comprised using the highest level of parental education and parent occupation reported in the family (male or female caregiver) and the household income per capita. The composite SES score is the M of the standardized z-scores of these indicators. Also, mother and youth acculturation levels were measured using 13 items that comprise the Anglo orientation subscale of the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). Adolescents and mothers independently rated how often items were true for them (1=Not at all; 5=Extremely often or almost always). Wave 1 coefficient alphas for the Anglo subscale = .81 for adolescents and .85 for mothers.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the study variables. Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted in Mplus 5.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2005) to utilize full information maximum likelihood (Schafer & Graham, 2002) to address the missing data at Wave 3. The regression analysis included maternal warmth and harsh discipline at Wave 1, the interaction between maternal warmth and harsh discipline, and the covariates as predictors. As hypothesized, adolescent reports of their mothers’ warmth and harsh discipline in 7th grade operated interactively to predict maternal report of externalizing 1 year later. The interaction was significant after controlling for baseline levels of externalizing and other covariates. The main effects of maternal warmth and harsh discipline were not significant. This model accounted for 49% of the variance in externalizing behaviors (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Warmth W1 | -- | -.11 | -.23** | -.10 | .13 | .06 | -.03 | -.08 | .03 | .06 | .16* |

| 2. Harsh Discipline W1 | -- | .21* | .11 | -.02 | .00 | .11 | .07 | -.04 | -.00 | .08 | |

| 3. Externalizing W1 | -- | .67*** | -.07 | -.05 | -.23** | -.05 | .05 | .02 | -.06 | ||

| 4. Externalizing W3 | -- | .04 | -.13 | -.23** | -.15 | .01 | .12 | .02 | |||

| 5. Adolescent Gendera | -- | .02 | .02 | -.10 | -.11 | .06 | .07 | ||||

| 6. SES | -- | .19** | -.30*** | -.22** | .40*** | .33*** | |||||

| 7. Family Structureb | -- | .22** | .13 | -.25*** | -.09 | ||||||

| 8. Maternal Nativity | -- | .35*** | -.83*** | -.40*** | |||||||

| 9. Youth Nativity | -- | -.41*** | -.28*** | ||||||||

| 10. Maternal Acculturation | -- | .48*** | |||||||||

| 11. Youth Acculturation | -- | ||||||||||

| n | 183 | 183 | 183 | 161 | 180 | 189 | 189 | 183 | 189 | 175 | 189 |

| Range | 1.00-5.00 | 1.00-5.00 | 0-35.00 | 0-40.00 | 1.00-2.00 | -2.83-1.75 | 1.00-2.00 | 1.00-2.00 | 1.00-2.00 | 1.08 – 5.00 | 2.15-5.00 |

| M | 4.15 | 2.08 | 7.95 | 7.58 | 1.54 | -.01 | 1.86 | 1.67 | 1.20 | 2.93 | 3.90 |

| SD | .79 | .79 | 7.04 | 7.57 | .50 | .78 | .35 | .48 | .40 | 1.15 | .56 |

Note. W1 = Wave 1 and W3 = Wave 3; a1 = male, 2 = females. b1 = single parent household, 2 = dual parent household.

p< .05.

p< .01.

p< .001.

TABLE 2.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses

| Variable | Externalizing W3 |

|---|---|

| Maternal Warmth | -.003 |

| Harsh Discipline | .01 |

| Maternal Warmth × Harsh Discipline | -.13* |

| Externalizing, W1 | .64*** |

| Youth Gender | .08 |

| SES | -.13* |

| Family Structure | -.05 |

| Maternal Nativity | .07 |

| Youth Nativity | .05 |

| Maternal Acculturation | .21 |

| Youth Acculturation | .03 |

| Total R2 | .49 |

Note. βs are standardized regression coefficients.

p< .05.

p< .001.

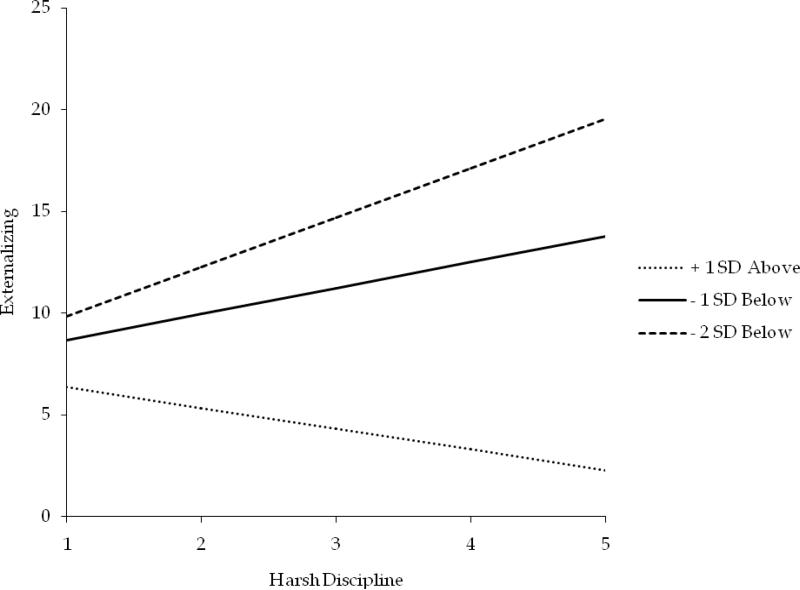

Simple slope analyses indicated that at high levels of maternal warmth (1 SD > M), there was no relation between harsh discipline and externalizing, B = -1.02, ns. At 1SD < M on maternal warmth, there was also no relation between harsh discipline and later externalizing, B = 1.27, ns. Therefore, an additional simple slope analysis was conducted at 2 SDs < M on maternal warmth. This analysis resulted in a relation between harsh discipline and later externalizing, B = 2.42, p < .05. Figure 1 presents the three simple slopes (+1SD, -1SD, -2SD). In this study, 1SD > M on warmth (higher warmth) referred to adolescents who perceived their mothers as engaging in warm and supportive behaviors almost always or always, +1SD = 4.94; lower warmth mothers who were 1SD < M were perceived by their adolescents as sometimes engaging in these behaviors, -1SD = 3.36; mothers at 2SDs < M were perceived as engaging in these behaviors once in a while, -2SD = 2.57.

Figure 1.

Plot of the simple slopes for the relation between harsh discipline and adolescent externalizing at +1SD, -1SD, and –2SD of maternal warmth.

DISCUSSION

The effects of harsh discipline on adolescent externalizing for low-income MA youth are conditional. The effects of harsh discipline depend on the level of maternal warmth, such that, under conditions of high warmth, there was no relation between harsh discipline and adolescent externalizing. However, under conditions of low maternal warmth, there was a positive relation between harsh discipline and externalizing. This result was found assessing MA adolescents from the 7th through 8th grades, a time when externalizing typically begins to increase.

These findings replicate similar interactions found in previous studies with other ethnic groups (Deater-Deckard et al., 2006; Simons, Wu, Lin, Gordon, & Conger, 2000) and extend the finding to a population that is Mexican American and examines early- to middle-age adolescents. The protective effects of adolescent perceptions of maternal warmth extend to a broader measure of punitive discipline practices. These findings are longitudinal, not likely biased by method variance, and controlled for youths’ previous levels of externalizing, increasing confidence in the results. This is the first study we know of to demonstrate such effects with a MA population.

It is important to note the study used a community sample which likely does not represent the full distribution of harsh discipline in the population (abusive discipline strategies that would necessitate the involvement of child protective services). Similarly, the low extreme of the distribution on maternal warmth is not likely represented in this sample. However, neither maternal warmth nor harsh discipline exceeded the cutoffs for skewness or kurtosis characterized by West, Finch, and Curran (1995) as being problematic for path models. Nevertheless, it is important to interpret the results of this study based on the descriptive definitions of what higher and lower levels of warmth meant in this specific population.

For example, it is interesting to note that adolescents only had to perceive their mothers as sometimes engaging in warmth-type behaviors for the protective effect to hold. It is possible that cultural variables not included in this study (such as familism) could potentially explain this finding. Familism values, a set of normative beliefs espoused by Latino populations that emphasize the importance of having a strong and cohesive family unit with obligations to support both nuclear and extended kin, have been found to have links to externalizing among MA youth (Germán, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009). Among MA families with strong familism values, maternal demonstration of warmth may not be consistently needed to buffer the effects of harsh discipline in response to child misbehavior on youth externalizing. In support of this supposition, it was solely the subset of adolescents in this sample who perceived their mothers as only engaging in warm and supportive behaviors “once in a while” (a value of 2 on a 5-point Likert scale) who experienced higher levels of externalizing over time as mothers’ use of harsh discipline increased.

These results are consistent with attachment research which indicates that insecure attachment styles predict higher levels of behavior problems in children (Cassidy, Kirsh, Scolton & Parke, 1996). Adolescents who perceive their mothers as high on warmth and live in high-crime neighborhoods may likely perceive their parents’ harsh discipline as motivated by a desire to keep them safe. Parental safety concerns in Arizona may also extend to the larger social climate in which there may be anti-immigrant sentiments. Also, there is evidence that the use of harsh discipline in response to children's misbehavior is normative among low-income MA families (Hill, Bush & Roosa, 2003). Cultural normativeness, combined with high levels of maternal warmth, likely decrease adolescent cognitions of harsh discipline as rejecting or unfair (Lansford et al., 2005). In contrast, adolescent children of mothers who are low on warmth are likely to perceive their parents’ use of harsh discipline as rejection (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). Feeling emotionally rejected and angry is thought to promote poor emotional regulation (Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000) and enhance attributions of threat (Cassidy et al., 1996), two factors related to externalizing behaviors.

Study Limitations

This study's effect was measured exclusively with adolescent perceptions of parenting in low-income MA families with a majority of mothers reporting Mexican nativity and a majority of adolescents completing the interview in Spanish. These families lived in high-crime neighborhoods which may not generalize to other reporters of parenting and other families living in different contexts. Using adolescents’ perceptions of maternal warmth may be a strength of the study because it suggests that youth perceptions may be the true explanatory variable of this study's effect. However, using multiple reporters on the study variables may also have strengthened the measurement validity of the study's constructs. Also, the non-experimental design of this study does not allow us to rule out third variables that may potentially explain the parenting effects (e.g., child temperament). Perhaps children with particular types of temperaments facilitate the development of warmth in the parent-child dyad.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE, APPLICATION, AND POLICY

The use of harsh discipline by parents as a method to address child misbehavior is controversial. In response to severe abuse cases and a large body of literature that has supported positive associations between harsh discipline and negative youth outcomes, many states have adopted public policies aimed at reducing such discipline practices. However, these policies are contentious in part because they contradict many adults’ own childhood experiences with discipline and their long-term outcomes. For example, one nationally representative sample found that over 90% of parents reported using corporal punishment on children yet the overwhelming majority of these children do not grow up to develop conduct problems (Straus & Stewart, 1999). This study's findings demonstrate one condition under which harsh discipline does not promote the development of youth externalizing.

Moreover, the current results raise the question of whether the term “harsh discipline” is a culturally inappropriate description of the disciplinary practices of Latino parents. Given our supposition that cultural normativeness, combined with high levels of maternal warmth, may help adolescents not perceive the discipline as “harsh”, it would be interesting to conduct a phemonological study from MA adolescents’ perspectives to inquire how they would describe their mothers’ discipline.

It is important to note that we are not endorsing the use of harsh discipline practices since under conditions of low warmth, the use of such practices predicted higher levels of externalizing over time. Nevertheless, this study joins a small, but growing body of literature that suggests the effects of harsh discipline are not direct but conditional. Given the controversial nature of parents’ harsh discipline practices and the impact of past research on public policy, it is important that researchers continue to examine contextual influences that may give us a clearer picture of the long-term effects of harsh discipline on youth from ethnically diverse backgrounds.

In closing, the topic of what constitutes “optimal” parental discipline practices continues to be debated in our society. Kazdin and Benjet (2003) identified three contrasting views about harsh discipline that capture the range of viewpoints in the general public, among policymakers, and among clinical and research professionals: (1) the pro-harsh discipline view; (2) the anti-harsh discipline view; and (3) the conditional harsh discipline view. For psychologists, who are often asked for parenting advice and also play an important role in training the next generation of clinicians, the implications of the current study suggest that they should discuss the impact of discipline on low-income, Mexican American children in a nuanced way (i.e., conditional harsh discipline view), acknowledging that the empirical literature has a growing body of evidence to suggest ethnicity and other parenting practices interact in a complex way to impact child outcomes over time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was supported by NIMH grant 1-R01-MH64707-01 to fund a Preventive Intervention for Mexican American Adolescents.

Footnotes

In a sample of low-income, Mexican American adolescents and mothers, the impact of harsh discipline on later adolescent externalizing behaviors depended on the level of warmth that adolescents perceived in their mothers.

Contributor Information

Miguelina Germán, Montefiore Medical Center, 3444 Kossuth Avenue, Bronx, NY 10467..

Nancy A. Gonzales, Darya Bonds McClain, Larry Dumka, and Roger Millsap are at Arizona State University.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM. Manual of the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Behling O, Law KS. Translating questionnaires and other research instruments: Problems and solutions. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada E. From el cuco to time out: Bringing culture into Latino parent training programs; Paper presented at the conference for Developing Interventions for Latino children, youth, and families; St. Louis, MO. May, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Kirsh S, Scolton K, Parke R. Attachment and representations of peer relationships. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:892–904. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK, Aque C. Interpretations of parenting control by Asian immigrant and European American youth. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:342–354. doi: 10.1037/a0015828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–303. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge K. Al, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European-American mothers: Links to children's externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Ivy L, Petrill S. Maternal warmth moderates the link between physical punishment and child externalizing problems: A parent-offspring behavior genetic analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6:59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Germán M, Gonzales NA, Dumka L. Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin adolescents exposed to deviant peers. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(1):16–42. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth L, Ispa J, Rudy D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development. 2006;77:1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill N, Bush K, Roosa M. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children's mental health: Low-income Mexican American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74:189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Benjet C. Spanking children: evidence and issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford J, Chang L, Dodge K, Malone P, Oburu P, Palmerus K, et al. Physical discipline and children's adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development. 2005;76:1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Kuhn BR. Comparing child outcomes of physical punishment and alternative disciplinary tactics: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8:135–148. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise E, Arsenio W. An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development. 2000;71:107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V, Smith J. Physical discipline and behavior problems in African American, European American, and Hispanic children: Emotional support as a moderator. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 4th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children's reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirolli A. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Arizona State University; 2004. The relation of Mexican American cultural orientation to familism. [Google Scholar]

- Simons R, Wu C, Lin KH, Gordon L, Conger R. A cross cultural examination of the link between corporal punishment and adolescent antisocial behavior. Criminology. 2000;38:47–79. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:55–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, conscience, self. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of child psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, US: 2006. pp. 24–98. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés G. Con Respecto: Bridging the distance between culturally diverse families and schools. Teachers College Press; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with non-normal variables. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]