CEP120 cooperates with CPAP to promote centriole elongation in a cell cycle– and microtubule-dependent manner.

Abstract

Centriole duplication begins with the formation of a single procentriole next to a preexisting centriole. CPAP (centrosomal protein 4.1–associated protein) was previously reported to participate in centriole elongation. Here, we show that CEP120 is a cell cycle–regulated protein that directly interacts with CPAP and is required for centriole duplication. CEP120 levels increased gradually from early S to G2/M and decreased significantly after mitosis. Forced overexpression of either CEP120 or CPAP not only induced the assembly of overly long centrioles but also produced atypical supernumerary centrioles that grew from these long centrioles. Depletion of CEP120 inhibited CPAP-induced centriole elongation and vice versa, implying that these proteins work together to regulate centriole elongation. Furthermore, CEP120 was found to contain an N-terminal microtubule-binding domain, a C-terminal dimerization domain, and a centriolar localization domain. Overexpression of a microtubule binding–defective CEP120-K76A mutant significantly suppressed the formation of elongated centrioles. Together, our results indicate that CEP120 is a CPAP-interacting protein that positively regulates centriole elongation.

Introduction

Centrioles are conserved microtubule (MT)-based organelles that are essential for the formation of centrosomes, cilia, and flagella. Centriole duplication is a tightly ordered event that involves the growth of a procentriole orthogonal to a preexisting centriole (Azimzadeh and Marshall, 2010; Nigg and Stearns, 2011). A core of only a few evolutionarily conserved proteins, including SAS-6, CPAP/SAS-4, and STIL/Ana2/SAS-5, is indispensable for centriole assembly in worms, flies, and humans (Brito et al., 2012; Gönczy, 2012). The onset of centriole assembly in human cells is triggered by the activation of PLK4 (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007) and the recruitment of CEP152 (Cizmecioglu et al., 2010; Dzhindzhev et al., 2010; Hatch et al., 2010) to the surface of the mother centriole. STIL (Tang et al., 2011; Arquint et al., 2012; Vulprecht et al., 2012) and hSAS-6 (Strnad et al., 2007) are then recruited to the base of the nascent procentriole during the late G1 and early S phases. CEP135 directly binds to hSAS-6 and CPAP, linking the cartwheel to the outer MTs (Lin et al., 2013). CPAP then promotes the assembly of nine triplet MTs during centriole biogenesis (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009).

CEP120 contains a C-terminal coiled-coil domain that is conserved in many organisms (Mahjoub et al., 2010). The putative orthologue of CEP120 (Uni2) in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is essential for basal body maturation and flagellogenesis (Piasecki et al., 2008). In mice, Cep120 is preferentially expressed in neural progenitors and is involved in controlling interkinetic nuclear migration (Xie et al., 2007). A recent study showed that Cep120 is up-regulated during the differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells and is essential for centriole assembly (Mahjoub et al., 2010). However, the involved mechanisms are not yet clearly understood.

We initially identified CPAP as being associated with the γ-tubulin complex (Hung et al., 2000). More recent studies have demonstrated that CPAP is a positive regulator of centriole length (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009) and that mutations in CPAP/CENPJ cause primary microcephaly in humans (Bond et al., 2005). Here, we show that CEP120 cooperates with CPAP to regulate centriole elongation.

Results and discussion

CEP120 overexpression induces extra long MT-based filaments with centriolar proteins

To investigate the molecular mechanism through which CEP120 regulates centriole assembly, we generated U2OS-derived cell lines stably expressing full-length CEP120-Myc (CEP120-FL-Myc) under the control of tetracycline (Tet). CEP120-Myc–inducible cells were treated with or without Tet and analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. S1 A) and confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. S1 B). Intriguingly, nearly 80% of the CEP120-Myc–inducible cells (clone #5; Fig. S1 C) produced extra long MT-based filamentous structures that stained positive for acetylated-tubulin (Ac-Tub) and appeared to extend from the ends of the centrioles (Fig. S1 B). A similar phenotype of extra long filaments was also observed to various degrees in other CEP120-Myc–inducible lines and in HEK 293T or HeLa cells transiently transfected with a CEP120-Myc construct (unpublished data).

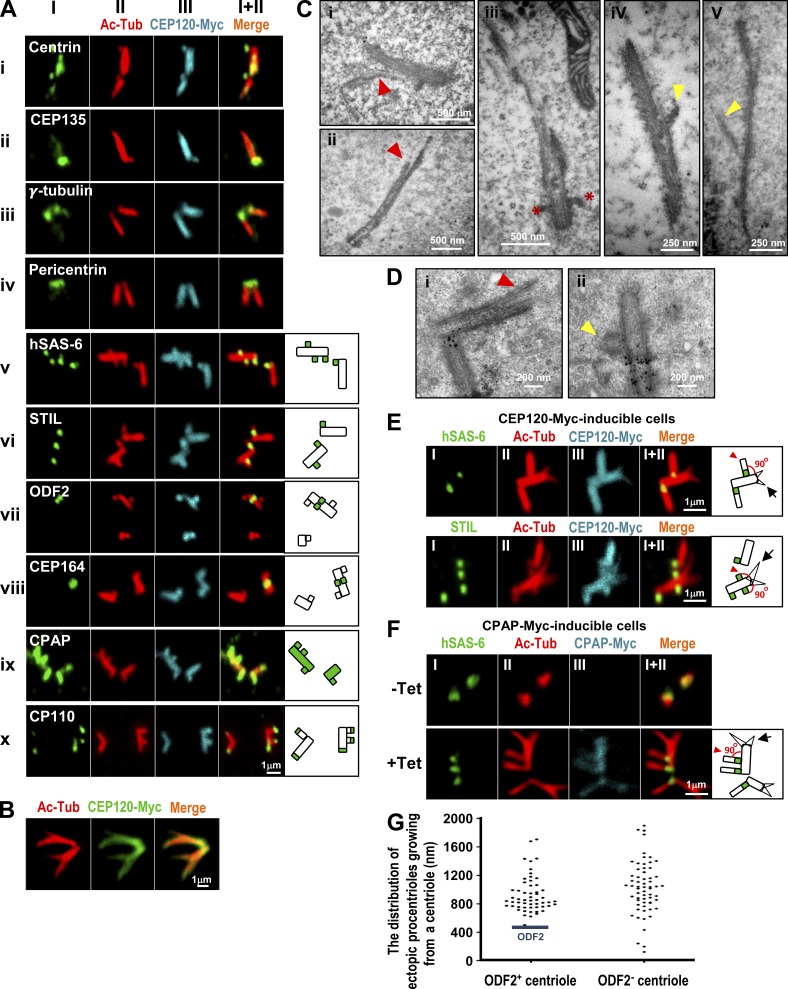

Further immunofluorescence staining indicated that the extra long filaments contained several known centriolar proteins, including centrin (Fig. 1 A, i) and CEP135 (Fig. 1 A, ii), and the bases of these long filaments appeared to be surrounded by the pericentriolar proteins γ-tubulin (Fig. 1 A, iii) and pericentrin (Fig. 1 A, iv). Two procentriole markers (hSAS-6 and STIL) were detected at the base of the centrioles (Fig. 1 A, v and vi). ODF2 and CEP164, two mother centriole appendage proteins, were observed in the filaments (Fig. 1 A, vii and viii). The CPAP present in both mother and daughter centrioles was colocalized with CEP120 and spread along the Ac-Tub filaments (Fig. 1 A, ix). CP110, which normally marks the distal regions of centrioles, was frequently detected at the ends of these long filaments (Fig. 1 A, x). Intriguingly, a portion of cells with long branched filaments were also found in CEP120-Myc–inducible cells (∼10%; Fig. 1 B).

Figure 1.

Overexpression of either CEP120 or CPAP induces atypical centriole amplification with extra long centrioles. (A–E) CEP120-Myc–inducible cells were treated with Tet for 48 h and analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy using the indicated antibodies (A, B, and E) or by EM (C and D). (C and D) The branched or vertically aligned MT-based filaments are marked by red or yellow arrowheads, respectively. Red asterisks in C (iii) represent appendage structures. (D) The small black dots are nonspecific precipitates that possibly formed during sample preparation. (C) The mean length and width of these CEP120-induced filaments were ∼1,000 and ∼195 nm, respectively (n = 40). (F) Excess CPAP induces the formation of atypical supernumerary centrioles from a preexisting centriole. CPAP-Myc–inducible cells were treated without (−Tet) or with (+Tet) Tet for 48 h and analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. (G) The distribution of atypical ectopic procentrioles growing from ODF2-positive or -negative centrioles (n = 119 from a single experiment). CEP120-Myc–inducible cells were treated with Tet for 48 h and immunostained with antibodies against ODF2 and Ac-Tub.

Electron microscopy (EM) revealed that the extra long filaments contained MT-based structures (Fig. 1, C [i and ii] and D [i]) that strongly resembled those previously observed in CPAP-inducible cells (Tang et al., 2009). A portion of the long MT-based filaments appeared to extend from the ends of mother centrioles, as marked by appendages (Fig. 1 C, iii). Based on these results, we conclude that CEP120 induced the production of long filaments containing proteins that are characteristic of centriolar cylinders and have a MT-based structure similar to that of a centriole.

Excess CEP120 induces atypical supernumerary centrioles extending from a preexisting long centriole

Unexpectedly, CEP120 overexpression also induced atypical centriole amplification. As shown in Fig. S1 D, 48 h after CEP120 induction, nearly 35% of asynchronously proliferating cells showed amplified (greater than four) centrioles with elongated filaments (Fig. S1 E).

Careful examination of the CEP120-induced filaments revealed a striking phenotype in a portion of CEP120-inducible cells (∼15%), with multiple short protruding filaments growing from a preexisting long centriole (Fig. 1 A, v–x). In contrast to the branched filaments described in Fig. 1 B, these Ac-Tub–labeled filaments appeared to align almost vertically at a 90° angle to the preexisting filaments (Fig. 1 E), in a pattern similar to the growth of a procentriole from a mother centriole. Intriguingly, hSAS-6 (Fig. 1, A [v] and E) and STIL (Fig. 1, A [vi] and E), which are located asymmetrically to the proximal end of a daughter centriole (Strnad et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2011), were clearly detected at the bases of the protruding filaments. Furthermore, some of the short Ac-Tub–labeled filaments appeared to protrude from the mother centrioles, which were marked by ODF2 (Fig. 1 A, vii) and CEP164 (Fig. 1 A, viii).

Interestingly, the vertically aligned filaments (Fig. 1 E, arrowhead) induced by CEP120 overexpression appeared to differ from the branched filaments (Fig. 1 E, arrow) in two ways: nearly all of the branched filaments lacked the daughter centriolar proteins hSAS-6 and STIL at their branching sites (Fig. 1 E, arrow) and the branched filaments were usually not aligned vertically with respect to each other (Fig. 1 E). Thus, the branched filaments induced by CEP120 overexpression most likely represented abnormally splayed MTs extending from the elongated centrioles. Indeed, both the branched (Fig. 1, C [i and ii] and D [i], red arrowheads) and vertically aligned MT-based filaments (Fig. 1, C [iv and v] and D [ii], yellow arrowheads) could be clearly visualized by EM using different preparation methods (Fig. 1, C vs. D; and see Materials and methods). Furthermore, amplified atypical centrioles with vertically aligned filaments containing hSAS-6 at their bases were also detected in CPAP-Myc–inducible cells (∼6%; Fig. 1 F, arrowhead).

We examined the distribution of these atypical ectopic procentrioles from either ODF2-positive or -negative elongated centrioles. Our results showed that these ectopic procentrioles appeared to be distributed along the elongated centrioles and often formed above the ODF2 appendage protein (Fig. 1 G). A few ectopic procentrioles (<3%) grew from the bases of ODF2-negative centrioles (Fig. 1 G). Together, we conclude that overexpression of CEP120 or CPAP produces atypical supernumerary centrioles and extra long MT-based filaments. This type of centriole amplification appears to differ from that observed in cells overexpressing PLK4 (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007) or STIL (Tang et al., 2011), in which the amplified centrioles are observed around the base of the mother centriole. The involved mechanism is not yet known.

CEP120-induced centriole elongation shows a biphasic pattern

We next examined the timing of CEP120-induced filament formation during the cell cycle by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. S2 A) and FACS (Fig. S2 B), as shown in Fig. S2 C. After withdrawal of aphidicolin, we commonly observed a biphasic centriole elongation pattern during the cell cycle. The Ac-Tub–labeled filaments from both mother and daughter centrioles appeared to elongate slowly during S phase (0–4 h after Tet induction), but increased rapidly during G2 and M phases (∼8–12 h after Tet induction; Fig. S2, A and D). A similar pattern was previously observed in CPAP-inducible cells (Tang et al., 2009). Interestingly, endogenous CEP120 levels oscillated during the cell cycle; they increased gradually from early S to G2/M and decreased significantly after mitosis (Fig. S2 E). This suggests that the protein levels of CEP120 must be carefully regulated to ensure that centrioles are formed correctly in terms of their numbers and lengths.

CEP120 directly interacts with CPAP

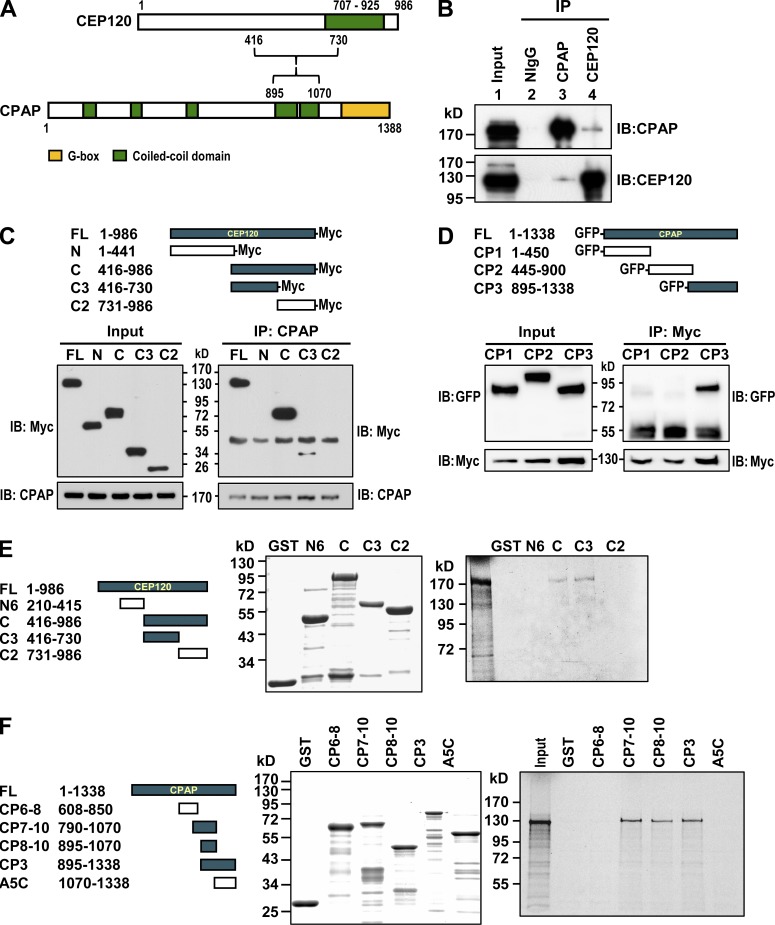

We next examined whether endogenous CEP120 can form a complex with CPAP. Our coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that endogenous CEP120 did coprecipitate with CPAP (Fig. 2 B). To further map the interacting domains of CEP120 and CPAP, we transfected Myc-tagged cDNA constructs encoding various portions of CEP120 into HEK 293T cells and performed immunoprecipitation with an anti-CPAP antibody. The CPAP-interacting domain was mapped to the central region (C3) of CEP120 (Fig. 2 C). Using a similar approach, we found that the C terminus of CPAP (CP3) interacts with CEP120 (Fig. 2 D). Furthermore, GST pull-down assays demonstrated that GST-CEP120 (C3, residues 416–730) and GST-CPAP (CP8–10, residues 895–1,070) directly interacted with [35S]methionine-labeled full-length CPAP (Fig. 2 E) and CEP120 (Fig. 2 F), respectively. Together, these findings indicate that CEP120 directly interacts and forms a complex with CPAP both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2.

CEP120 interacts with CPAP. (A) A schematic representation of the interaction between CEP120 and CPAP. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that endogenous CEP120 and CPAP form a complex in vivo. (C) CPAP interacts with the C3 domain of CEP120. (D) CEP120 interacts with the CP3 domain of CPAP. (E) Mapping the CPAP-interacting domain in CEP120 by GST pull-down assays. Full-length [35S]methionine-labeled CPAP proteins were incubated with bead-bound GST or various GST-CEP120–truncated proteins and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (F) Mapping the CEP120-interacting domain in CPAP.

CEP120 and CPAP work together to promote centriole elongation

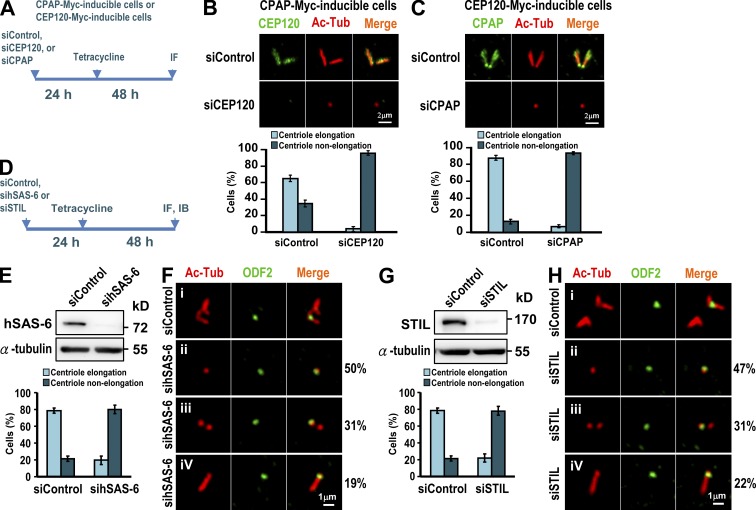

To test whether CEP120 is required for CPAP-induced centriole elongation, we treated CPAP-Myc–inducible cells (Tang et al., 2009) as shown in Fig. 3 A. Our results showed that depletion of CEP120 significantly inhibited CPAP-induced centriole elongation, from 65% (siControl) to 4% (siCEP120; Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

CEP120 cooperates with CPAP to promote centriole elongation and both hSAS-6 and STIL are required for CEP120-induced centriole elongation. (A–C) CPAP-Myc– (B) and CEP120-Myc (C)–inducible cells were treated as shown in A and analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. The percentages of CPAP-Myc– or CEP120-Myc–induced elongated or nonelongated procentrioles formed after siCEP120 (B) or siCPAP (C) treatment are shown. (D–H) Depletion of hSAS-6 or STIL inhibits CEP120-induced centriole elongation. CEP120-Myc–inducible cells were transfected with siControl, sihSAS-6 (E and F), or siSTIL (G and H) as shown in D. Histograms illustrating the percentages of elongated or nonelongated centrioles induced by CEP120 overexpression in sihSAS-6– (E) or siSTIL-treated cells (G). Error bars represent means ± SD of 100 cells from three independent experiments.

We next examined whether depletion of CEP120 affects the centriolar localization of CPAP. U2OS cells were transfected with siControl or siCEP120 as described in Fig. S3 A. We observed a weak to moderate reduction of CPAP targeting to the centriole in siCEP120-depleted cells (91% in siControl vs. 62% in siCEP120; Fig. S3 C, bottom). Furthermore, CEP120 depletion did not appear to affect the recruitment of hSAS-6 to the procentriole (Fig. S3 D), suggesting that the early step of procentriole formation was not perturbed by CEP120 depletion. Similarly, depletion of CPAP also severely decreased CEP120-induced centriole elongation (Fig. 3 C) and appeared to have weak or no effect on the targeting of CEP120 (Fig. S3 E) or hSAS-6 (Fig. S3 F) to the centriole. We thus conclude that CEP120 and CPAP are both required for centriole elongation and seem to have a weak mutual dependence for their centriolar localization.

STIL and hSAS-6 are required for CEP120-induced centriole elongation

Previous studies showed that two centriolar proteins located at the proximal end of the procentriole, hSAS-6 (Strnad et al., 2007) and STIL (Tang et al., 2011), are required for the early events of procentriole formation. To examine whether hSAS-6 and STIL are required for CEP120-induced centriole elongation, we treated CEP120-Myc inducible cells with sihSAS-6 (Fig. 3, E and F) or siSTIL (Fig. 3, G and H), as described in Fig. 3 D. Our results showed that hSAS-6 depletion significantly inhibited CEP120-induced centriole elongation (∼79% vs. ∼20%; Fig. 3 E). Intriguingly, ∼50% of sihSAS-6–treated cells contained a single mature mother centriole labeled by ODF2 (Fig. 3 F, ii), whereas the other cells contained either two short centrioles (∼31%; Fig. 3 F, iii) or a single long ODF2-labeled centriole (∼19%; Fig. 3 F, iv). Thus, hSAS-6 depletion seems to mostly affect CEP120-induced centriole elongation extending from newly assembled procentrioles. Similar effects were also observed in STIL-depleted cells (Fig. 3, G and H). Collectively, our results indicate that hSAS-6 and STIL are required for CEP120-mediated centriole elongation.

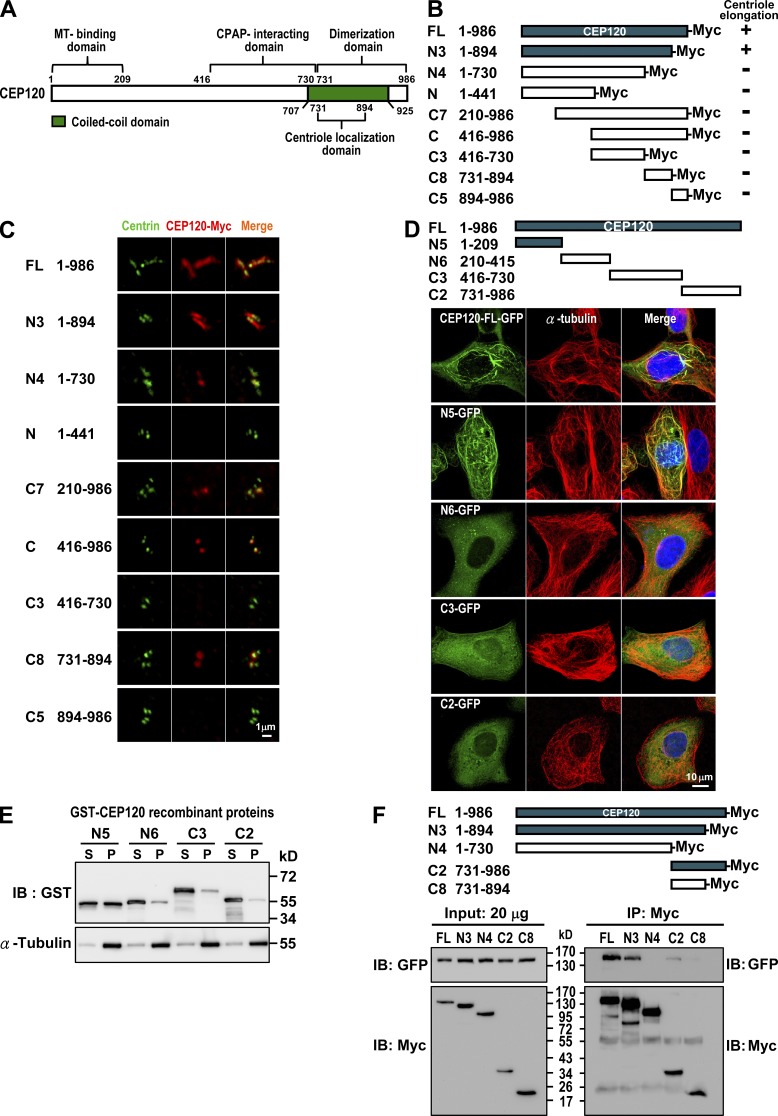

Characterization of CEP120 functional domains

Given that CEP120 overexpression can induce extra long centrioles (Fig. 1), we sought to define the minimum region of CEP120 for such a function. We generated a series of CEP120-Myc deletion mutants (Fig. 4 B), transiently expressed them in U2OS cells, and analyzed them by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4 C). To our surprise, only the N3 construct (residues 1–894), comprising nearly the full-length CEP120, induced extra long centrioles (Fig. 4 C). Other mutants that lacked either the C (N4) or the N terminus (C7) of CEP120 failed to induce longer centrioles, implying that both termini are important for CEP120-mediated centriole elongation.

Figure 4.

Mapping the functional domains of CEP120. (A) Summary of CEP120 functional domains. (B and C) Mapping the region required for CEP120-induced centriole elongation. U2OS cells were transiently transfected with various CEP120-Myc–truncated constructs (B) and analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy using antibodies against centrin and Myc (C). (D and E) Mapping the MT-binding domain in CEP120. Various GFP-tagged CEP120-truncated constructs (D) were transiently expressed in U2OS cells and analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. (E) A MT cosedimentation assay was performed by incubating various recombinant GST-CEP120 proteins with purified tubulins and Taxol (20 µM). The supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were analyzed by immunoblotting. (F) Mapping the dimerization domain in CEP120. HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with various Myc-tagged CEP120-truncated constructs and a full-length CEP120-GFP. 24 h after transfection, cell lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

To examine whether CEP120 possesses MT-binding activity, we generated a series of CEP120-GFP deletion constructs (Fig. 4 D) and transiently expressed them in U2OS cells. Our results showed that both CEP120-FL-GFP (∼30%) and N5-GFP (∼42%) revealed a strong MT association pattern (Fig. 4 D). Furthermore, MT cosedimentation experiments showed that GST-N5 could bind to and cosediment with MTs in the pellet (Fig. 4 E). These results suggest that the N terminus of CEP120 (N5, residues 1–209) directly binds to MTs.

We next examined the possible function of the C terminus of CEP120. A previous study showed that the C-terminal domain of mouse Cep120 is required for centriolar localization (Mahjoub et al., 2010). Consistent with this finding, we further narrowed down the centriolar localization to the C8 (residues 731–894) of human CEP120 (Fig. 4 C). Unexpectedly, the C-terminal C2 domain (Fig. 4 F) also possessed the ability to homodimerize. Our coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that the full-length CEP120-Myc and deletion constructs containing the C8 fragment (N3 and C2) were able to form complexes with full-length CEP120-GFP (Fig. 4 F), whereas the C8 fragment alone exhibited a very weak association (Fig. 4 F). These results suggest that the C terminus of CEP120 is required for both centriolar localization and self-dimerization.

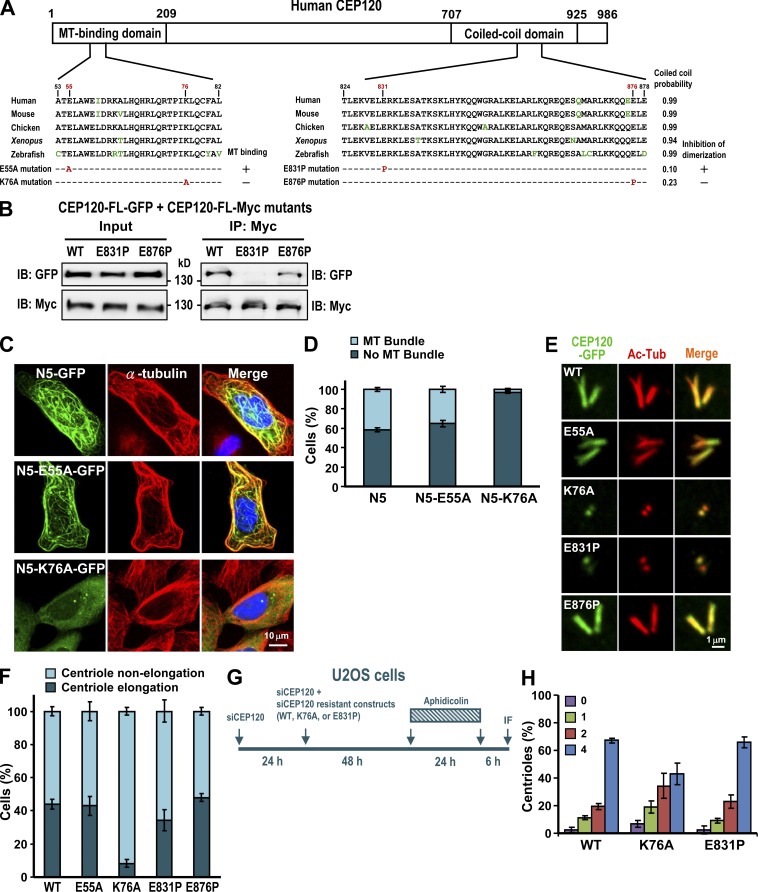

To examine whether MT binding or self-dimerization is essential for CEP120-mediated centriole elongation, we generated two different types of mutants. The first contained a proline mutation (E831P or E876P) that disrupted the predicted α-helical structure in the C-terminal coiled-coil domain (Fig. 5 A). In the second (K76A or E55A), highly conserved basic (lysine, K) or acidic (glutamic acid, E) residues at the N terminus were replaced with a more neutral residue (alanine, A). Immunofluorescence analyses showed that N5-K76A, but not N5-E55A, was impaired in its ability to bind MTs (Fig. 5, C and D). Furthermore, the formation of extra long centrioles was significantly inhibited in cells expressing full-length K76A construct (Fig. 5, E and F). We thus conclude that the MT-binding activity of CEP120 is essential for its centriole-elongating activity. We also examined the dimerization activity of CEP120 and found that the E831P mutant greatly reduced the binding to itself (Fig. 5 B), but had only a mild inhibitory effect on centriole elongation (Fig. 5 F). Furthermore, the K76A mutant seemed to moderately inhibit normal centriole duplication (Fig. 5 H).

Figure 5.

Functional characterization of the MT-binding and dimerization activities of CEP120. (A) Schematic representation of the CEP120 protein showing the mutations in the MT-binding and dimerization domains. (B) The E831P mutant showed decreased dimerization activity. HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with vectors encoding CEP120-FL-GFP and a CEP120-FL-Myc (E831P or E876P) mutant, and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. (C and D) The N5-GFP-K76A mutant showed reduced MT-binding activity. U2OS cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant N5-GFP constructs. 48 h after transfection, cells were analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (C). The percentages of transfected cDNA constructs that bound to MTs (MT bundle) are shown in D. (E and F) The effects of various CEP120 mutants on centriole elongation. U2OS cells were transfected with wild-type CEP120-FL-GFP or various CEP120-FL-GFP mutant constructs. 48 h after transfection, the cells were analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (E) and the percentages of cells with elongated or nonelongated centrioles were calculated (F). (G and H) The effects of various CEP120 mutants on normal centriole duplication. U2OS cells were treated as described in G. (H) Histogram illustrating the percentages of cells showing various centriole numbers after treatment. Error bars represent means ± SD of 100 cells from three independent experiments.

How do centriolar MT triplets elongate and what molecular mechanism determines their final length? A recent study showed that the nucleotide status of tubulin controls Sas-4 (a fly homologue of CPAP)–dependent recruitment of pericentriolar material (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2012). One possible scenario is that CPAP at the proximal end of a centriole may bind to either tubulin-GDP or tubulin-GTP via its intrinsic tubulin dimer binding domain. Such an interaction might then induce a conformational change that regulates the formation of CPAP–CEP120 complex and other associated proteins. This CPAP–CEP120 complex may help to assemble nine triplet MTs during centriole biogenesis. Future experiments are clearly needed to verify this hypothesis.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and antibodies

The cDNA encoding full-length CEP120 was RT-PCR amplified from total RNA of human HEK 293T cells and subcloned in-frame into the pEGFP-N2 (BD) or pcDNA4/TO/Myc–His-A (Invitrogen) vectors. To construct the GST fusion plasmids, cDNAs encoding various portions of CEP120 were fused in-frame to GST in the pGEX-4T vector. The GFP- or Myc-tagged CEP120 mutant constructs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange kit (Agilent Technologies). For siRNA-resistant CEP120 plasmid construction, the nucleotides targeted by siCEP120#3 within the full-length wild-type CEP120 in the pcDNA4/TO/Myc-His-A vector (5′-GGAAGGAGATGCAAGAAGATATATT-3′) were partially replaced without changing the amino acid sequence (5′-GGAAGGAGATGCAGGAGGACATCTT-3′) using the QuickChange kit. The sequences of all constructed plasmids were confirmed. The rabbit polyclonal antibody against CEP120 was raised using recombinant CEP120-His (residues 639–986) and affinity purified. The antibodies against CPAP (1:1,000 dilution; rabbit polyclonal raised against the C terminus of CPAP, residues 1,070–1,338; Hung et al., 2000), hSAS-6 (1:500 dilution; rabbit polyclonal against hSAS-6, residues 1–489; Tang et al., 2009), and centrin 2 (1:500 dilution; rabbit polyclonal against centrin2, residues 1–173; Tang et al., 2009) were obtained as described previously. Other commercially available antibodies used in this study included anti-ODF2 and anti-Myc-FITC (Abcam); anti-Ac-Tub (Sigma-Aldrich); anti-STIL-441a (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.); anti-Myc (4A6 [EMD Millipore] or NB600-336 [Novus Biologicals]); and anti-GFP (BD).

Cell culture and transfection

U2OS, HEK 293T, or HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were transfected with various cDNA constructs using Lipofectamine 2000. To generate U2OS-based CEP120-Myc– and CPAP-Myc–inducible lines, cDNAs encoding full-length CEP120 or CPAP were subcloned into the pcDNA4/TO/Myc-His-A vector (Invitrogen), which is under the control of the CMV promoter and two Tet operator 2 sites. The Tet-inducible lines expressing CEP120-Myc or CPAP-Myc (Tang et al., 2009) were generated by transfection of U2OS-T-Rex cells that stably express the Tet repressor TetR. U2OS-T-Rex cells were produced by transfection with pcDNA6/TR encoding TetR. To produce a functional construct, the Myc tag must place at the C terminus of CEP120. The expressions of CEP120-Myc and CPAP-Myc were induced by the addition of 1 µg/ml Tet to the culture medium.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy and EM analysis

Cells on coverslips were cold treated for 1 h at 4°C and then fixed in methanol at −20°C for 10 min. The cells were washed in PBS, blocked in 10% normal goat serum in PBS, and incubated with the indicated primary antibodies. The cells were washed with PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–, Alexa Fluor 568–, or Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). DNA was counterstained with DAPI. The samples were mounted in Vectashield mounting media (Vector Laboratories) and viewed on a confocal system (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss) with a Plan Apochromat 100×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective. Images were acquired with the ZEN or AimImage Browser software (Carl Zeiss).

For EM, CEP120-Myc–inducible cells (Fig. 1 C) were treated with Tet for 2 d. Cells were fixed in glutaraldehyde (2.5%) for 1 h, washed three times with PBS buffer, post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) for 1 h, dehydrated with serial ethanol, and embedded in LR white resin (Lin et al., 2013). The samples were examined with a transmission electron microscope (H7000; Hitachi). Alternatively, CEP120-Myc–inducible cells (Fig. 1 D) were grown on ACLAR embedding film (7.8-mil thickness; EMS) for 1 d and induced with Tet for 2 d. The cells were then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer at 4°C for 1 h. The fixed cells were washed three times with washing buffer (0.1 M sodium cacodylate/4% sucrose, pH 7.4) at 4°C, post-fixed in 1% OsO4/0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h at 4°C, stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 1 h at 4°C, dehydrated with serial ethanol, and embedded in Spur resin. Thin sections (80 nm) were stained with 4% uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate for 10 min. The samples were examined with an electron microscope (Tecnai G2 Spirit TWIN; FEI).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting experiments

To investigate whether endogenous CEP120 and CPAP forms a complex in vivo, HEK 293T cells were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitors including 1 µg/µl leupeptin, 1 µg/µl pepstatin, and 1 µg/µl aprotinin) for 30 min at 4°C. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatants were immunoprecipitated with anti-CEP120, anti-CPAP, or an irrelevant rabbit immunoglobulin (NIgG as a negative control) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with Protein G–Sepharose beads at 4°C for 2 h. The immunoprecipitates were then separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride microporous membrane (EMD Millipore), and probed with anti-CEP120 and anti-CPAP antibodies. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used in a 1:5,000 dilution. The immunoreactive bands were visualized using Luminata Crescendo Western HRP Substrate (EMD Millipore).

To study whether exogenously expressed CEP120-Myc is associated with GFP-CPAP, HEK 293T cells were transfected with indicated CEP120-Myc and GFP-CPAP constructs. 24 h after transfection, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 g at 4°C for 15 min and the supernatants were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody followed by incubation with Protein G–Sepharose beads at 4°C overnight. The immunoprecipitated complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-GFP or anti-Myc antibodies. To map the dimerization domain of CEP120, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with various Myc-tagged CEP120-truncated constructs and a full-length CEP120-GFP. 24 h after transfection, the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Cell synchronization and FACS analysis

For synchronization studies, cells were arrested at early S phase by double-thymidine block (2 mM) or aphidicolin (2 µg/ml). To analyze endogenous CEP120 during the cell cycle, HeLa cells were incubated with 2 mM thymidine for 15 h before transfer into fresh medium for 12 h, and were then incubated again in 2 mM thymidine for another 15 h. The synchronized cells were collected at different time points and subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies or FACS (FACScan; BD) analysis. For FACS analysis, cells were fixed in ice-cold 100% ethanol for 30 min, washed with PBS, and stained with 40 µg/ml propidium iodide. To examine the timing of CEP120-induced centriole elongation during the cell cycle, CEP120-Myc–inducible cells were treated with 2 µg/ml aphidicolin and 1 µg/ml Tet as shown in Fig. S2 C. At the indicated times after removal of aphidicolin, cells were analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy and FACS.

siRNA studies

The siRNAs used for hSAS-6, STIL, and CPAP were as described previously (Tang et al., 2011). The siRNAs used for CEP120 are as follows: siCEP120#1, 5′-AAAUCAAAUGCACAGUAAGACUGGG-3′; siCEP120#2, 5′-UGCAAGAGCCUGCAUAUGAGCCAGU-3′; siCEP120#3, 5′-AAUAUAUCUUCUUGCAUCUCCUUCC-3′. All siRNAs and a nontargeting siRNA control were purchased from Invitrogen. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagents (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer protocol. In brief, siRNAs (33 nM) were incubated with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagents for 20 min at room temperature. The siRNA–reagent complexes were added into the cells. After transfection, the cells were analyzed by immunoblotting and confocal fluorescence microscopy.

GST pull-down assay

To examine a direct interaction between CEP120 and CPAP, various portions of GST-CPAP or GST-CEP120 recombinant proteins were affinity purified by glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) and used to pull down [35S]methionine-labeled full-length CEP120 or CPAP that had been generated using an in vitro transcription/translation using the TNT T7 Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega). GST was used as a negative control. After binding, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography.

MT sedimentation assay

For in vitro MT cosedimentation assays, purified brain tubulin (2.5 mM; Cytoskeleton) was incubated with various GST-CEP120–truncated recombinant proteins in BRB80 buffer (80 mM Pipes, pH 6.9, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM MgCl2) containing 20 µM Taxol, 1 mM GTP, and 1 mM DTT for 30 min at 30°C (Lin et al., 2013). The samples were layered on top of 50 µl of BRB80 buffer containing 50% glycerol and centrifuged in an ultracentrifuge (TLA-100; Beckman Coulter) at 100,000 g for 20 min at 30°C. The supernatants and pellets were then analyzed with SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows additional data complementary to Fig. 1. Fig. S2 shows that CEP120-induced centriole elongation exhibits a biphasic pattern with slow growth in S phase and fast growth in G2 phase. Fig. S3 shows data on the centriolar localization of CPAP, CEP120, and hSAS-6 in CEP120- or CPAP-depleted cells. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201212060/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shin-Yi Lin for generating the U2OS-based CEP120-Myc–inducible cell lines. We also thank Sue-Ping Lee and Sue-Ping Tsai at the EM core facility of Institute of Molecular Biology and the staff at the DNA sequencing core facility and the confocal microscopy core facility of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences for their technical assistance.

This work was supported by Academia Sinica Investigator Award and partially by a grant from the National Science Council, Republic of China.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- Ac-Tub

- acetylated-tubulin

- MT

- microtubule

- Tet

- tetracycline

References

- Arquint C., Sonnen K.F., Stierhof Y.D., Nigg E.A. 2012. Cell-cycle-regulated expression of STIL controls centriole number in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 125:1342–1352 10.1242/jcs.099887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimzadeh J., Marshall W.F. 2010. Building the centriole. Curr. Biol. 20:R816–R825 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J., Roberts E., Springell K., Lizarraga S.B., Scott S., Higgins J., Hampshire D.J., Morrison E.E., Leal G.F., Silva E.O., et al. 2005. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat. Genet. 37:353–355 (published erratum appears in Nat. Genet. 2005. 37:555) 10.1038/ng1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito D.A., Gouveia S.M., Bettencourt-Dias M. 2012. Deconstructing the centriole: structure and number control. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24:4–13 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizmecioglu O., Arnold M., Bahtz R., Settele F., Ehret L., Haselmann-Weiss U., Antony C., Hoffmann I. 2010. Cep152 acts as a scaffold for recruitment of Plk4 and CPAP to the centrosome. J. Cell Biol. 191:731–739 10.1083/jcb.201007107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhindzhev N.S., Yu Q.D., Weiskopf K., Tzolovsky G., Cunha-Ferreira I., Riparbelli M., Rodrigues-Martins A., Bettencourt-Dias M., Callaini G., Glover D.M. 2010. Asterless is a scaffold for the onset of centriole assembly. Nature. 467:714–718 10.1038/nature09445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönczy P. 2012. Towards a molecular architecture of centriole assembly. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:425–435 10.1038/nrm3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan J., Chim Y.C., Ha A., Basiri M.L., Lerit D.A., Rusan N.M., Avidor-Reiss T. 2012. Tubulin nucleotide status controls Sas-4-dependent pericentriolar material recruitment. Nat. Cell Biol. 14:865–873 10.1038/ncb2527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch E.M., Kulukian A., Holland A.J., Cleveland D.W., Stearns T. 2010. Cep152 interacts with Plk4 and is required for centriole duplication. J. Cell Biol. 191:721–729 10.1083/jcb.201006049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung L.Y., Tang C.J., Tang T.K. 2000. Protein 4.1 R-135 interacts with a novel centrosomal protein (CPAP) which is associated with the gamma-tubulin complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7813–7825 10.1128/MCB.20.20.7813-7825.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Habedanck R., Stierhof Y.D., Nigg E.A. 2007. Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev. Cell. 13:190–202 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmaier G., Loncarek J., Meng X., McEwen B.F., Mogensen M.M., Spektor A., Dynlacht B.D., Khodjakov A., Gönczy P. 2009. Overly long centrioles and defective cell division upon excess of the SAS-4-related protein CPAP. Curr. Biol. 19:1012–1018 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.C., Chang C.W., Hsu W.B., Tang C.J.C., Lin Y.N., Chou E.J., Wu C.T., Tang T.K. 2013. Human microcephaly protein CEP135 binds to hSAS-6 and CPAP, and is required for centriole assembly. EMBO J. 32:1141–1154 10.1038/emboj.2013.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahjoub M.R., Xie Z., Stearns T. 2010. Cep120 is asymmetrically localized to the daughter centriole and is essential for centriole assembly. J. Cell Biol. 191:331–346 10.1083/jcb.201003009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E.A., Stearns T. 2011. The centrosome cycle: centriole biogenesis, duplication and inherent asymmetries. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1154–1160 10.1038/ncb2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki B.P., LaVoie M., Tam L.W., Lefebvre P.A., Silflow C.D. 2008. The Uni2 phosphoprotein is a cell cycle regulated component of the basal body maturation pathway in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19:262–273 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T.I., Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Lavoie S.B., Stierhof Y.D., Nigg E.A. 2009. Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr. Biol. 19:1005–1011 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strnad P., Leidel S., Vinogradova T., Euteneuer U., Khodjakov A., Gönczy P. 2007. Regulated HsSAS-6 levels ensure formation of a single procentriole per centriole during the centrosome duplication cycle. Dev. Cell. 13:203–213 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.J., Fu R.H., Wu K.S., Hsu W.B., Tang T.K. 2009. CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:825–831 10.1038/ncb1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.J., Lin S.Y., Hsu W.B., Lin Y.N., Wu C.T., Lin Y.C., Chang C.W., Wu K.S., Tang T.K. 2011. The human microcephaly protein STIL interacts with CPAP and is required for procentriole formation. EMBO J. 30:4790–4804 10.1038/emboj.2011.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulprecht J., David A., Tibelius A., Castiel A., Konotop G., Liu F., Bestvater F., Raab M.S., Zentgraf H., Izraeli S., Krämer A. 2012. STIL is required for centriole duplication in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 125:1353–1362 10.1242/jcs.104109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Moy L.Y., Sanada K., Zhou Y., Buchman J.J., Tsai L.H. 2007. Cep120 and TACCs control interkinetic nuclear migration and the neural progenitor pool. Neuron. 56:79–93 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.