This review discusses how kinetic proofreading by Rab GTPases provides a speed-dating mechanism defining the identity of membrane domains in vesicle trafficking.

Abstract

Rab GTPases are highly conserved components of vesicle trafficking pathways that help to ensure the fusion of a vesicle with a specific target organelle membrane. Specific regulatory pathways promote kinetic proofreading of membrane surfaces by Rab GTPases, and permit accumulation of active Rabs only at the required sites. Emerging evidence indicates that Rab activation and inactivation are under complex feedback control, suggesting that ultrasensitivity and bistability, principles established for other cellular regulatory networks, may also apply to Rab regulation. Such systems can promote the rapid membrane accumulation and removal of Rabs to create time-limited membrane domains with a unique composition, and can explain how Rabs define the identity of vesicle and organelle membranes.

Rab GTPases regulate membrane tethering and vesicle fusion

Eukaryotic cells are defined in part by their complex membrane organelles. This organization permits the coexistence of different chemical environments within the same cell. For example, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a neutral pH, reducing environment containing chaperones conducive to protein folding and the formation of disulfide bonds, whereas the lysosomes are ∼pH 5 and contain catabolic enzymes maximally active at acidic pH. Though valuable, this organization requires some form of active transport machinery for the exchange of material between these compartments because large hydrophilic molecules such as proteins cannot easily cross membranes. This transfer of molecules between compartments is achieved by vesicular transport systems that use cytosolic coat protein complexes to select small regions of membrane and shape these into defined 40–80-nm-diameter transport vesicles (Bonifacino and Glick, 2004; Faini et al., 2013). Vesicle coats contain binding sites for specific transport sequences, and thus only transfer a subset of proteins into the vesicle. Once produced, these vesicles have to identify, tether to, and then fuse with a specific target organelle (Zerial and McBride, 2001). Research over many years has defined small transmembrane proteins (SNAREs) and a set of accessory factors as the minimal machinery for membrane fusion (McNew et al., 2000; Shi et al., 2012). Tethering is a less well-defined event involving the Rab GTPases and effector protein complexes, typically large extended molecules thought to bridge the space between two approaching membranes (Gillingham and Munro, 2003).

Rab GTPases were first linked to vesicle transport by groundbreaking genetic screens for mutants defective in protein secretion (Novick et al., 1980; Salminen and Novick, 1987). Sec4, Rab8 in humans, was found to function in the terminal step of the secretory pathway, delivery of Golgi-derived transport vesicles to the cell surface (Salminen and Novick, 1987; Goud et al., 1988). Ypt1, Rab1 in humans, was then shown to regulate secretion at the Golgi apparatus (Segev et al., 1988; Bacon et al., 1989). These findings led to an influential model for Rab function in which the cycle of GTPase activation and inactivation is coupled to recognition events in vesicle docking (Bourne, 1988). Consistent with the idea that they control vesicle targeting, work in mammalian cells then showed that there is a large family of highly conserved Rab GTPases, each with a specific subcellular localization (Chavrier et al., 1990). A series of seminal studies has since provided direct evidence that Rab1 and Rab5 promote membrane fusion (Gorvel et al., 1991; Segev, 1991) by regulating the activation and engagement of SNAREs (Lian et al., 1994; Søgaard et al., 1994), as a consequence of recruiting tethering factors to membrane surfaces (Segev, 1991; Sapperstein et al., 1996; Cao et al., 1998; Christoforidis et al., 1999; McBride et al., 1999; Allan et al., 2000; Shorter et al., 2002). Similar findings were also made for the Rab Ypt7, which functions in vacuole docking in yeast (Price et al., 2000; Ungermann et al., 2000), a system that allows direct visualization of docked or tethered intermediates due to the large size of the membrane structures (Wang et al., 2002).

The evidence that Rabs function upstream of SNARE protein in vesicle trafficking pathways has led to the notion that Rabs help to define the identity of vesicle and organelle membranes (Pfeffer, 2001; Zerial and McBride, 2001). This is best exemplified by the early endocytic pathway, where the identity of early and late endosomes is thought to be determined by Rab5 and Rab7, respectively (Rink et al., 2005). However, in most other cases it remains unclear if this is a causal relationship, where the Rab directly defines the identity of the membrane rather than acting as an upstream regulator of vesicle targeting before the SNARE-mediated membrane fusion event. In addition to Rabs, GTPases of the Arf/Arl family and specific phosphoinositide lipids have also been proposed to act in specifying membrane identity (Munro, 2002; Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006). It therefore seems likely that no single factor can explain how membrane identity is achieved in vesicle transport, and that Rabs, phosphoinositides, and other factors act in concert.

Rab GEFs provide the minimal machinery for targeting and activation

Despite the progress in defining Rab function, the claim that Rab GTPases define organelle identity therefore remains premature due to crucial unanswered questions. In particular, the issue of how Rabs are targeted to specific organelles, or even restricted to subdomains of these organelles, has remained problematic. Initial work using chimeric GTPases suggested that the variable C-terminal region of the different Rabs provided a targeting mechanism (Chavrier et al., 1991). However, subsequent work indicated that this failed to provide a general mechanism to explain specific Rab targeting, and that multiple regions of the Rab including C-terminal prenylation contribute to membrane recruitment (Ali et al., 2004). Emerging evidence based on the improved understanding of the family of Rab guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) now provides an alternative view for Rab activation at specific membrane surfaces. Mechanistic details of how Rab GEFs activate Rabs have been discussed elsewhere (Barr and Lambright, 2010), and are not directly relevant for this discussion so won’t be detailed further. Two studies now show that Rab GEFs can provide the minimal machinery needed to target a Rab to a specific membrane within the cell (Gerondopoulos et al., 2012; Blümer et al., 2013). In both cases, Rab GEFs were fused to mitochondrial outer membrane targeting sequences, and the effects on different Rabs observed. Using this strategy it was possible to specifically target Rab1, Rab5, Rab8, Rab35, and Rab32/38 to mitochondria with biochemically defined cognate GEFs (Gerondopoulos et al., 2012; Blümer et al., 2013). Mutants that either reduced the nucleotide exchange activity of the GEF or the target GTPase gave a correspondingly reduced rate of Rab targeting (Blümer et al., 2013). Alone this does not provide a full explanation for Rab targeting; for this an understanding of the interaction of prenylated Rabs with the chaperone GDI (guanine nucleotide displacement inhibitor) is needed. Structural and biophysical analysis of the Ypt1–GDI complex has revealed two components of this interaction relevant for Rab targeting (Pylypenko et al., 2006). Domain I of GDI interacts with the switch II region of Ypt1 only when this is in the GDP-bound inactive form. The doubly prenylated C terminus of Ypt1 occupies a hydrophobic cavity created by domain II of GDI. Simulation of this system and direct biophysical measurements suggests that in the absence of other factors GDI will rapidly deliver Rabs to and extract them from a lipid bilayer (Pylypenko et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2010). These ideas can be combined into a simple model for Rab activation at specific membrane surfaces (Fig. 1 A). In simple terms this model is a form of molecular speed-dating in which the Rab spends a short time sampling each membrane surface it encounters before finally meeting its cognate GEF partner, triggering a period of longer residence at that site (Fig. 1 A). In this model, GEF-mediated nucleotide exchange renders the Rab resistant to extraction by GDI, and thus drives accumulation of the active GTP-bound form of the Rab. This active Rab can then recruit effector proteins to the membrane surface and promote the desired recognition event. Such a system is analogous to the rapid proofreading of amino-acyl tRNAs during protein synthesis by the ribosome (Ibba and Söll, 1999). All amino-acyl tRNAs can enter the so-called acceptor site, but only if stable codon recognition occurs is the peptidyltransferase reaction initiated, otherwise the tRNA is rejected (Steitz, 2008). The two-stage kinetic proofreading of membrane surfaces by Rabs may similarly increase fidelity at little overall cost to the rate of vesicular traffic.

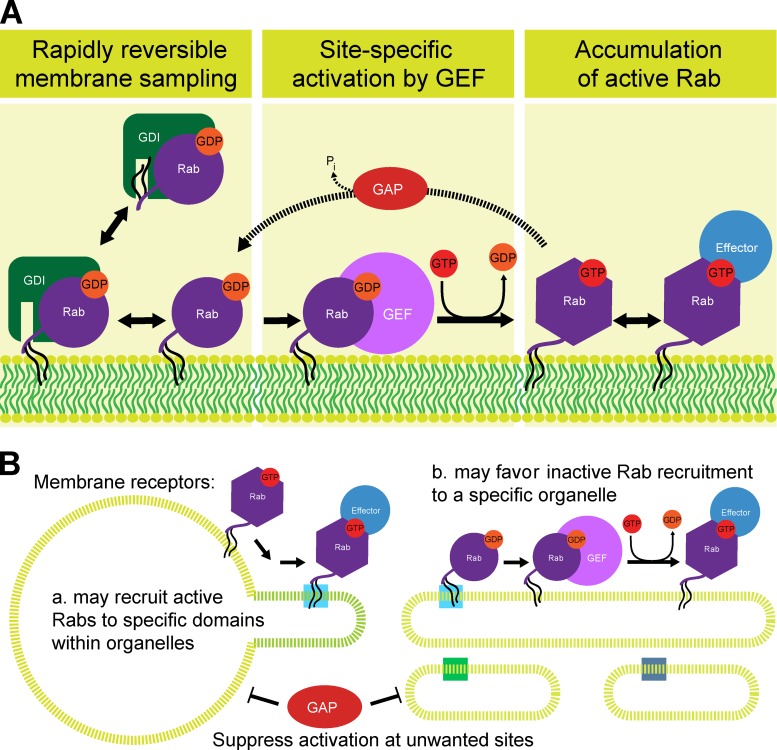

Figure 1.

The Rab activation and inactivation cycle. (A) Prenylated Rabs (black wavy lines) are bound by the chaperone GDI in the cytosol. Partitioning of the prenylated tail moiety between the hydrophobic pocket in GDI and the membrane bilayer allows Rabs to rapidly and reversibly sample membrane surfaces. When the GDP-bound inactive Rab encounters a cognate GEF nucleotide exchange occurs. This GTP-bound active Rab species does not interact with GDI and can therefore accumulate on the membrane surface, where it may further recruit effector proteins with specific biological functions. This cycle is reset when a GTP-bound Rab encounters a GAP (GTPase-activating protein) and the bound GTP is hydrolyzed to generate GDP and inorganic phosphate. (B) Additional specification of membrane domains within complex organelles, such as tubular domains of endosomes, or the fenestrated rims and different cisternae of the Golgi apparatus, may involve membrane receptors for Rabs (shown as light blue, dark blue, and green boxes). This could either involve (a) sequestration of the active Rab to a subdomain defined by the membrane receptor, or (b) direction of GDI unloading of an inactive Rab to specific sites on the organelle membrane also defined by a membrane receptor. Accumulation of a Rab at a specific site may be favored by GAPs opposing Rab activation at unwanted sites (Haas et al., 2007).

Although this minimal Rab-targeting system does not require any additional factors, it is important to mention that this does not mean such factors do not exist. A family of membrane proteins with prenylated Rab-binding activity that can promote dissociation of some prenylated Rabs from GDI and favor retention of the GDP-bound form of the Rab downstream of membrane delivery by GDI has been identified (Dirac-Svejstrup et al., 1997; Martincic et al., 1997; Hutt et al., 2000; Sivars et al., 2003). These may therefore favor Rab activation, although recent data has suggested that such factors are not generally essential (Blümer et al., 2013). Intriguingly, other evidence links this family of proteins to factors involved in shaping subdomains of the ER and to the Golgi apparatus (Yang et al., 1998; Calero et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2004; Voeltz et al., 2006), perhaps suggesting that they may play roles in defining at which subdomain of an organelle an active Rab is enriched (Fig. 1 B).

In addition to these regulatory factors, covalent modification can also be used to modulate the Rab activation cycle. Phosphorylation of Rab1 and Rab4 in mitosis alters the fraction of these GTPases that can associate with membranes (Bailly et al., 1991; van der Sluijs et al., 1992), although the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Furthermore, emerging evidence indicates that one Rab in yeast, Ypt11, is controlled by a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism regulating its activation and abundance (Lewandowska et al., 2013). A number of bacterial pathogens also encode enzymes that directly modify Rab GTPases and as a consequence alter the Rab regulatory cycle. During Legionella infection, Rab1 is modulated by a cycle of adenylylation and de-adenylylation by DrrA and SidA, respectively, and this modification of the conserved tyrosine residue in the switch II renders the protein constitutively active (Müller et al., 2010; Neunuebel et al., 2011; Tan and Luo, 2011). DrrA also has a GEF domain and can therefore directly activate and trap Rab1 in an active form independent of other cellular factors (Schoebel et al., 2009). A second bacterial protein, AnkX, mediates phosphocholination of an adjacent serine within the switch II region (Mukherjee et al., 2011; Campanacci et al., 2013). Pathogens such as Legionella use this covalent modification of Rabs to modulate their localization and activation (Stein et al., 2012). Although cellular enzymes that carry out related modification of Rabs are currently unknown, it would be premature to dismiss the possibility of their existence and use by cells to similarly control Rab activation and inactivation at specific sites.

Evidence for Rab activation on vesicle and target membrane surfaces

Based on the model and discussion so far it seems obvious that Rabs accumulate on the same membrane as their cognate GEF. Indeed, there is evidence that Rab1 may be activated and recruit the p115 tethering factor during the COP II vesicle formation stage of ER-to-Golgi transport (Allan et al., 2000). This would have the advantage that identity would be created at an early stage in vesicle biogenesis, and the vesicle could therefore be tethered to the Golgi before completion of the vesicle, thus increasing targeting efficiency. However, there is also evidence that Rab activation can occur at the target membrane and not only on a vesicle surface. Careful analysis of cell-free ER–Golgi transport assays revealed that Ypt1–Rab1 is not always required on the vesicle fraction, but is essential on the target Golgi membranes (Cao and Barlowe, 2000). Furthermore, a Ypt1 mutant with reduced nucleotide hydrolysis (which prevents its recycling from the Golgi compartment; Richardson et al., 1998), or Golgi membrane-anchored forms of Ypt1 (Cao and Barlowe, 2000) both support apparently normal ER–Golgi transport and cell growth. Subsequently, it was found that the COP II coat required to form ER–Golgi transport vesicles is the membrane receptor for the Ypt1–Rab1 GEF TRAPP (transport protein particle; Jones et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000; Cai et al., 2007), indicating that Rab1 activation may occur on the coated vesicle. This raises questions about how the cytosolic Rab–GDI complex can access the membrane surface of a still-coated vesicle. However, because the COP II coat has an open lattice structure (Faini et al., 2013), it may be possible in this case for Ypt1–Rab1 to approach the membrane and insert. A further possibility is that COP II vesicles recruit TRAPP and promote the activation of Ypt1–Rab1 at the adjacent Golgi membranes to signal that an ER-derived vesicle is in close proximity (Fig. 2 A). This Golgi pool of activated Rab would then recruit effector proteins such as Uso1/p115 that trap and tether the incoming vesicle by directly engaging with vesicle SNAREs (Cao et al., 1998; Shorter et al., 2002).

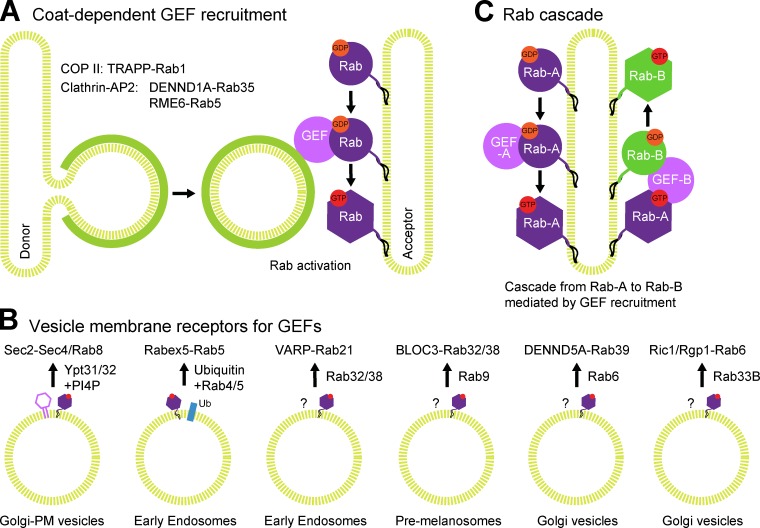

Figure 2.

Recruitment mechanisms for Rab GEFs. Rab GEFs can be divided into two groups according to the mechanism of membrane recruitment. (A) Discrete coat protein complexes (green) recruit the first group. For example, COP II recruits the Rab1 GEF TRAPP to ER-Golgi vesicles, while clathrin-AP2 recruits DENND1A, the Rab35 GEF, to endocytic sites at the cell surface. In the case of TRAPP, biochemical and genetic data suggest that Rab1 can be activated on the target membrane, before vesicle tethering and SNARE-mediated fusion. (B) The larger second group of Rab GEFs is recruited by Rab GTPases either alone or in combination with a second factor (Rabs/factors listed next to arrow). For example, the GEF Sec2 is recruited to late-Golgi vesicles trafficking to the bud in yeast by the activated Rab Ypt31/32 and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P), where it activates the Rab Sec4 (Rab8 in humans). The Rabex5–rabaptin complex, which is a Rab5 GEF, interacts with activated Rab4 or Rab5 and ubiquitylated cargo proteins on endocytic vesicles and early endosomes. A number of other GEFs (some additional examples shown) have been found to interact with active Rabs. Whether or not these represent the sole mode of membrane interaction for these GEFs is not defined at this time. PM, plasma membrane. (C) In situations where the GEF for a second Rab in the pathway is an effector for the first, a cascade can develop, where Rab-A promotes the recruitment of GEF-B for this second Rab-B.

Rab GEF targeting and regulation

The mechanism of GEF targeting is of crucial importance for understanding how Rabs are activated at a particular membrane site. At present, two different solutions to the problem depending on the GEF are known. First, as already mentioned, is vesicle coat–dependent GEF targeting (Fig. 2 A). Three examples are known at present: COP II recruitment of the Rab1 GEF TRAPP-I (Cai et al., 2007), and clathrin-adaptor protein complex 2–dependent recruitment of either the Rab35 GEF DENND1A (Allaire et al., 2010; Yoshimura et al., 2010) or the Rab5 GEF RME-6 (Sato et al., 2005; Semerdjieva et al., 2008) during endocytic transport from the plasma membrane. In the latter cases the exact nature of the membrane on which the target Rab is activated is unclear, but it is tempting to speculate that like COP II, the coated vesicle promotes Rab activation on the target organelle to signal the presence of an incoming vesicle to be tethered. The second larger group of GEFs comprises those known to interact with active Rab GTPases (Fig. 2 B). The first of these Rab GEF effectors defined was the Rabex-5–rabaptin complex, which is both a Rab5 exchange factor and effector for Rab4 and Rab5 (Horiuchi et al., 1997). Rabex-5 also binds to ubiquitin via a specific domain and this is important for regulating its recruitment to early endosomes (Lee et al., 2006; Mattera et al., 2006; Mattera and Bonifacino, 2008) where it activates Rab5.

Specific phosphatidylinositols play a key role in defining membrane identity (Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006)), and this is in part due to a role in recruitment or regulation of Rab exchange factors. Sec2, the exchange factor for Sec4–Rab8, is recruited to post-Golgi vesicles by a combination of the Rab Ypt32 and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate generated by Pik1 (Ortiz et al., 2002; Sciorra et al., 2005; Mizuno-Yamasaki et al., 2010). Similarly, in mammalian cells the Rab GEF Sec2–Rabin8 is recruited by the Ypt31/32 orthologue Rab11 (Knödler et al., 2010), and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate generated by the Pik1 orthologue Fwd is important for Rab11 regulation in Drosophila (Polevoy et al., 2009). Although less is known about the targeting of other Rab GEFs, the clear theme is that many are effectors for a Rab other than the one they activate (Fig. 2 B). The Ric1–Rgp1 complex is a GEF for Rab6 and effector for Rab33B at the Golgi (Pusapati et al., 2012) and the Rab21 GEF VARP is an effector for Rab32/38 (Zhang et al., 2006; Tamura et al., 2009). Additionally, a GEF for Rab32/38 is an effector for Rab9 (Kloer et al., 2010; Gerondopoulos et al., 2012), and the DENND5A Rab39 GEF is an effector for Rab6 (Recacha et al., 2009; Yoshimura et al., 2010). In addition to these canonical trafficking functions there are specialized examples that indicate there is some plasticity to both GEF targeting and specificity. The Ypt1 GEF TRAPP exists in an alternate form (TRAPP-II) with additional subunits that promote late-Golgi targeting and may create additional GEF activity toward Ypt31/32 (Morozova et al., 2006). Interestingly, in higher eukaryotes there is evidence that TRAPP-II may regulate the Ypt31/32 orthologues Rab11 in male meiotic cytokinesis in flies (Robinett et al., 2009) and Rab-A in plant cell polarization and division (Qi et al., 2011), respectively. TRS85 in another alternate TRAPP complex (TRAPP-III) promotes localization to the forming autophagosome and activates Rab1 during autophagy (Lynch-Day et al., 2010).

The counterpart to this interlinked network of Rab activation is an equally complex set of interactions between Rabs and Rab GAPs. The GAP Gyp1 is an effector for Ypt32 and promotes GTP hydrolysis by Ypt1 in budding yeast (Rivera-Molina and Novick, 2009). In the absence of Gyp1, Ypt1 spreads into the later compartments of the secretory pathway that should be occupied by Ypt32 (Rivera-Molina and Novick, 2009). Interestingly, one of the cellular GAPs for Ypt1–Rab1 is a transmembrane protein of the ER that may prevent Rab1 activity from spreading earlier in the pathway to the ER rather than act to terminate Rab1 activity at the Golgi (Haas et al., 2007; Sklan et al., 2007). Similarly, two related proteins, RUTBC1 and RUTBC2, bind to active Rab9 and are GAPs for Rab32 and Rab36, respectively (Nottingham et al., 2011, 2012).

Together, these findings have led to the general idea that the order of trafficking events in a pathway can potentially be defined by a series of Rabs acting as a cascade (Fig. 2 C). In such models one Rab triggers the next in the pathway by recruiting its cognate GEF, and then feedback develops as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) is recruited to terminate the action of the previous Rab in the series (Mizuno-Yamasaki et al., 2012; Pfeffer, 2013). In part, this simply passes the problem on because we are then left with the question of how the previous Rab in the pathway or a cofactor for recruitment such as phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate or ubiquitin is localized and generated only when required. In the case of the secretory pathway the ER provides a defined starting point where activation of Rab1–Ypt1 will inevitably result in a defined and correctly timed wave of Rab activation through the secretory pathway. However, a note of caution is needed when considering these ideas because far more support from experimental data looking at the biochemical properties of these systems both in vitro and in vivo is required to come to any definitive conclusions.

Ultrasensitive Rab activation switches

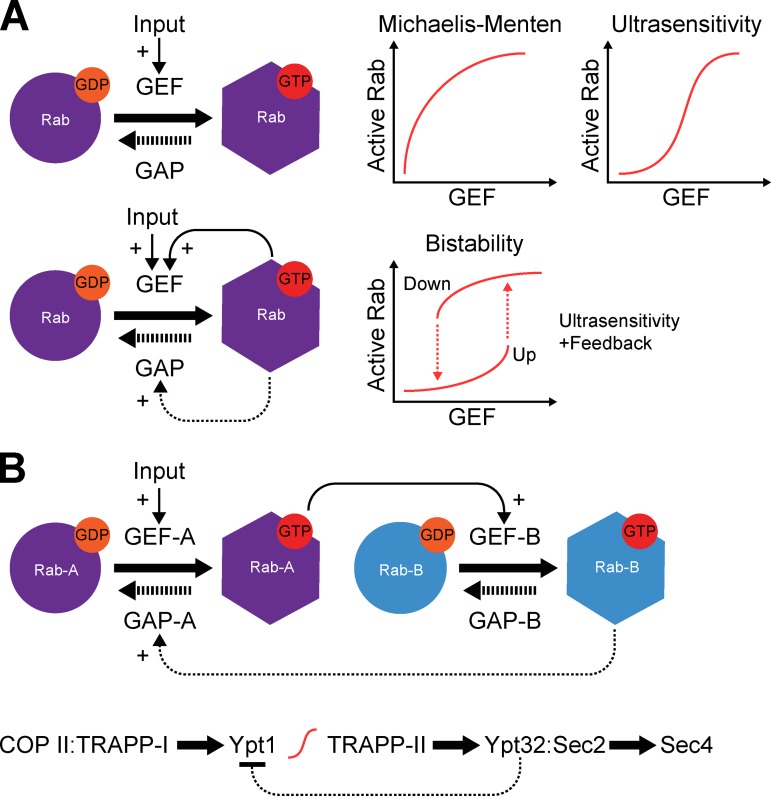

One of the key tenets of the membrane identity hypothesis is that Rabs should rapidly and accurately establish membrane identity and then be lost once the membrane recognition event is over. Although biochemical data on Rab GEFs clearly indicate these molecules generally have sufficiently high specificity to ensure activation of only one Rab or a set of closely related Rabs (Delprato et al., 2004; Yoshimura et al., 2010; Gerondopoulos et al., 2012), how rapid switch-like accumulation is ensured is less obvious. Similar issues exist for termination of the Rab cycle by Rab GAPs. As already mentioned, Rab cascade models give part of the solution to this problem, and provide features that can ensure vectorial flow in a membrane traffic pathway (Mizuno-Yamasaki et al., 2012; Pfeffer, 2013). However, they do not fully explain how switch-like transitions and defined compartmental boundaries are achieved (Del Conte-Zerial et al., 2008). A possible solution to this problem comes from studies on the regulation of other complex biological systems, exemplified by control of cell cycle transitions (Tyson et al., 2001). Rather than displaying the expected Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 3 A), Rab cycles may yield properties of ultrasensitivity (Goldbeter and Koshland, 1981, 1984). This would appear to be a valid proposal if the Rab cycle is treated as being analogous to a covalent modification (Rab and Rab-modified, for GDP and GTP forms, respectively) and because GEF activity is generally assumed to be limiting (Blümer et al., 2013). In such a situation, inputs activating the GEF, for example membrane recruitment requiring multiple or binding of an activator, would be amplified and give rise to very large changes in the amount of activated Rab (Fig. 3 A). When combined with feedback loops, this can create a bistable switch between two states as shown for cell cycle transitions (Novak and Tyson, 1993; Pomerening et al., 2003). In the case of GTPase regulation, as the input controlling the GEF increases then the system transitions to a Rab-active state that remains stable over a wide range of GEF activity. GAP activation could then trigger exit from this state. This is also useful for providing a potential explanation for the timing properties of a Rab cascade. Ultrasensitivity and bistability are therefore likely to be useful concepts when explaining the behavior of Rabs, especially when considering complex interlinked cycles (Fig. 3 B) because they avoid the futile cycles where GAPs and GEFs fight one another and thus don’t do any useful work.

Figure 3.

Ultrasensitivity and bistability in Rab regulatory networks. (A) A simplified schematic of a Rab activation cycle is shown treating GDP–GTP exchange as equivalent to a covalent modification cycle such as phosphorylation. Because the reaction can only occur at a membrane surface, membrane recruitment factors are treated as activating inputs. Assuming no feedback and normal first-order reaction kinetics, Rab recruitment would be expected to follow Michaelis-Menten behavior. In cases where substrate is saturating and the reaction becomes zero-order, Goldbeter and Koshland (1984) have shown that product formation becomes more sensitive to enzyme concentration. In this case, generation of GTP-bound Rab becomes ultrasensitive to GEF concentration at the membrane surface. If additional positive feedback controls exist as shown in the bottom panel, then bistability may develop. In this case a rapid switch-like transition in Rab activity develops as Rab GEF concentration increases. Once in the active state the system becomes less dependent on continued high GEF activity. (B) A model for an interlinked Rab cascade is shown. The GEF for Rab-B is an effector for activated Rab-A, while the GAP for Rab-A is regulated by Rab-B. An example of this latter situation is provided by the Ypt1–Yp32 system discussed in the main text and shown in the bottom panel, where a Ypt1 GAP Gyp1 is an effector for Ypt32 (Rivera-Molina and Novick, 2009) and inhibits Ypt1. This coupling of the two cycles can result in coupled ultrasensitive switch-like transitions or bistability.

A groundbreaking study in this area has applied these ideas to the conversion of Rab5-positive early endosomes to Rab7-positive late endosomes and lysosomes (Del Conte-Zerial et al., 2008). This analysis has provided strong evidence that positive and negative feedback loops in this system mediated by Rab GEFs and GAPs result in bistability in the form of a cut-out switch, so that Rab5 accumulation is followed by an abrupt transition at which Rab5 is rapidly lost and Rab7 accumulates (Del Conte-Zerial et al., 2008). Underpinning this is a biochemical network in which the Mon1–Ccz1 Rab7 GEF complex displaces Rabex-5, thus breaking the positive feedback loop to Rab5 activation (Poteryaev et al., 2010) and simultaneously promoting recruitment and activation of Rab7 (Nordmann et al., 2010; Gerondopoulos et al., 2012). Although there are only few studies where these ideas have been considered, they can be experimentally tested and are likely to be of increasing importance in membrane traffic regulation.

Origins of Rab GTPase control systems

One of the most difficult questions in membrane trafficking relates to the origins of complex internal membrane systems in eukaryotes. Analysis of Rab GTPases themselves suggests a pattern of evolution of Rabs consistent with the evolution of a core set of membrane organelles of the endocytic and secretory pathways (Diekmann et al., 2011; Klöpper et al., 2012). Yet, this provides little insight into how membrane organelles initially arose. Recent data on the structure of Rab GTPase regulators and coat protein complexes has identified common features with GTPase regulators in other systems including prokaryotes (Kinch and Grishin, 2006; Zhang et al., 2012; Levine et al., 2013). The conserved Longin–Roadblock fold has emerged as a structural feature of the large family of DENN-domain Rab GEFs in human cells (Yoshimura et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2011; Levine et al., 2013). Intriguingly, related domains are also present in the signal sequence receptor involved in protein translocation into the ER, vesicle coat protein complexes, and the MglA GTPase–MglB bacterial cell polarity regulator (Sun et al., 2007; Miertzschke et al., 2011; Levine et al., 2013). Although far from conclusive, these findings provide important pointers to the development of GTPase control systems, and more generally the early origins of membrane traffic pathways in eukaryotes from membrane-associated GTPases and their effector proteins.

Are Rabs alone capable of triggering the pathways defining membrane identity? Multiple lines of evidence show Rab GTPases are clearly important and far from inconsequential regulators of vesicle traffic; however, further evidence is required before we should conclude that they are causal regulators of vesicle or organelle membrane identity. Neither of the studies using strategies to modulate the cellular localization of Rab GEFs reported that the mitochondria altered their identity or were converted into an endosome or Golgi because of the mistargeted Rabs (Gerondopoulos et al., 2012; Blümer et al., 2013). The picture emerging is therefore one in which Rabs cannot program membrane identity alone and must work in concert with other factors. Defining and reconstituting the systems needed to create membrane identity is therefore a major goal for membrane traffic research.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Bela Novak for helpful discussions.

A Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (097769/Z/11/Z) supports research into membrane trafficking by F.A. Barr.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- GAP

- GTPase-activating protein

- GDI

- guanine nucleotide displacement inhibitor

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- TRAPP

- transport protein particle

References

- Ali B.R., Wasmeier C., Lamoreux L., Strom M., Seabra M.C. 2004. Multiple regions contribute to membrane targeting of Rab GTPases. J. Cell Sci. 117:6401–6412 10.1242/jcs.01542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaire P.D., Marat A.L., Dall’Armi C., Di Paolo G., McPherson P.S., Ritter B. 2010. The Connecdenn DENN domain: a GEF for Rab35 mediating cargo-specific exit from early endosomes. Mol. Cell. 37:370–382 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan B.B., Moyer B.D., Balch W.E. 2000. Rab1 recruitment of p115 into a cis-SNARE complex: programming budding COPII vesicles for fusion. Science. 289:444–448 10.1126/science.289.5478.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon R.A., Salminen A., Ruohola H., Novick P., Ferro-Novick S. 1989. The GTP-binding protein Ypt1 is required for transport in vitro: the Golgi apparatus is defective in ypt1 mutants. J. Cell Biol. 109:1015–1022 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly E., McCaffrey M., Touchot N., Zahraoui A., Goud B., Bornens M. 1991. Phosphorylation of two small GTP-binding proteins of the Rab family by p34cdc2. Nature. 350:715–718 10.1038/350715a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr F., Lambright D.G. 2010. Rab GEFs and GAPs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22:461–470 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blümer J., Rey J., Dehmelt L., Mazel T., Wu Y.W., Bastiaens P., Goody R.S., Itzen A. 2013. RabGEFs are a major determinant for specific Rab membrane targeting. J. Cell Biol. 200:287–300 10.1083/jcb.201209113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J.S., Glick B.S. 2004. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell. 116:153–166 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01079-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne H.R. 1988. Do GTPases direct membrane traffic in secretion? Cell. 53:669–671 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90081-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H., Yu S., Menon S., Cai Y., Lazarova D., Fu C., Reinisch K., Hay J.C., Ferro-Novick S. 2007. TRAPPI tethers COPII vesicles by binding the coat subunit Sec23. Nature. 445:941–944 10.1038/nature05527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calero M., Whittaker G.R., Collins R.N. 2001. Yop1p, the yeast homolog of the polyposis locus protein 1, interacts with Yip1p and negatively regulates cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 276:12100–12112 10.1074/jbc.M008439200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanacci V., Mukherjee S., Roy C.R., Cherfils J. 2013. Structure of the Legionella effector AnkX reveals the mechanism of phosphocholine transfer by the FIC domain. EMBO J. 32:1469–1477 10.1038/emboj.2013.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Barlowe C. 2000. Asymmetric requirements for a Rab GTPase and SNARE proteins in fusion of COPII vesicles with acceptor membranes. J. Cell Biol. 149:55–66 10.1083/jcb.149.1.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Ballew N., Barlowe C. 1998. Initial docking of ER-derived vesicles requires Uso1p and Ypt1p but is independent of SNARE proteins. EMBO J. 17:2156–2165 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavrier P., Parton R.G., Hauri H.P., Simons K., Zerial M. 1990. Localization of low molecular weight GTP binding proteins to exocytic and endocytic compartments. Cell. 62:317–329 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90369-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavrier P., Gorvel J.P., Stelzer E., Simons K., Gruenberg J., Zerial M. 1991. Hypervariable C-terminal domain of rab proteins acts as a targeting signal. Nature. 353:769–772 10.1038/353769a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.Z., Calero M., DeRegis C.J., Heidtman M., Barlowe C., Collins R.N. 2004. Genetic analysis of yeast Yip1p function reveals a requirement for Golgi-localized rab proteins and rab-Guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor. Genetics. 168:1827–1841 10.1534/genetics.104.032888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforidis S., McBride H.M., Burgoyne R.D., Zerial M. 1999. The Rab5 effector EEA1 is a core component of endosome docking. Nature. 397:621–625 10.1038/17618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Conte-Zerial P., Brusch L., Rink J.C., Collinet C., Kalaidzidis Y., Zerial M., Deutsch A. 2008. Membrane identity and GTPase cascades regulated by toggle and cut-out switches. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4:206 10.1038/msb.2008.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delprato A., Merithew E., Lambright D.G. 2004. Structure, exchange determinants, and family-wide rab specificity of the tandem helical bundle and Vps9 domains of Rabex-5. Cell. 118:607–617 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. 2006. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 443:651–657 10.1038/nature05185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann Y., Seixas E., Gouw M., Tavares-Cadete F., Seabra M.C., Pereira-Leal J.B. 2011. Thousands of rab GTPases for the cell biologist. PLOS Comput. Biol. 7:e1002217 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirac-Svejstrup A.B., Sumizawa T., Pfeffer S.R. 1997. Identification of a GDI displacement factor that releases endosomal Rab GTPases from Rab-GDI. EMBO J. 16:465–472 10.1093/emboj/16.3.465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faini M., Beck R., Wieland F.T., Briggs J.A. 2013. Vesicle coats: structure, function, and general principles of assembly. Trends Cell Biol. 23:279–288 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerondopoulos A., Langemeyer L., Liang J.R., Linford A., Barr F.A. 2012. BLOC-3 mutated in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome is a Rab32/38 guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Curr. Biol. 22:2135–2139 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillingham A.K., Munro S. 2003. Long coiled-coil proteins and membrane traffic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1641:71–85 10.1016/S0167-4889(03)00088-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbeter A., Koshland D.E., Jr 1981. An amplified sensitivity arising from covalent modification in biological systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 78:6840–6844 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbeter A., Koshland D.E., Jr 1984. Ultrasensitivity in biochemical systems controlled by covalent modification. Interplay between zero-order and multistep effects. J. Biol. Chem. 259:14441–14447 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvel J.P., Chavrier P., Zerial M., Gruenberg J. 1991. rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell. 64:915–925 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90316-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goud B., Salminen A., Walworth N.C., Novick P.J. 1988. A GTP-binding protein required for secretion rapidly associates with secretory vesicles and the plasma membrane in yeast. Cell. 53:753–768 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90093-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A.K., Yoshimura S., Stephens D.J., Preisinger C., Fuchs E., Barr F.A. 2007. Analysis of GTPase-activating proteins: Rab1 and Rab43 are key Rabs required to maintain a functional Golgi complex in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 120:2997–3010 10.1242/jcs.014225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi H., Lippé R., McBride H.M., Rubino M., Woodman P., Stenmark H., Rybin V., Wilm M., Ashman K., Mann M., Zerial M. 1997. A novel Rab5 GDP/GTP exchange factor complexed to Rabaptin-5 links nucleotide exchange to effector recruitment and function. Cell. 90:1149–1159 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80380-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutt D.M., Da-Silva L.F., Chang L.H., Prosser D.C., Ngsee J.K. 2000. PRA1 inhibits the extraction of membrane-bound rab GTPase by GDI1. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18511–18519 10.1074/jbc.M909309199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibba M., Söll D. 1999. Quality control mechanisms during translation. Science. 286:1893–1897 10.1126/science.286.5446.1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Newman C., Liu F., Segev N. 2000. The TRAPP complex is a nucleotide exchanger for Ypt1 and Ypt31/32. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:4403–4411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinch L.N., Grishin N.V. 2006. Longin-like folds identified in CHiPS and DUF254 proteins: vesicle trafficking complexes conserved in eukaryotic evolution. Protein Sci. 15:2669–2674 10.1110/ps.062419006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloer D.P., Rojas R., Ivan V., Moriyama K., van Vlijmen T., Murthy N., Ghirlando R., van der Sluijs P., Hurley J.H., Bonifacino J.S. 2010. Assembly of the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex-3 (BLOC-3) and its interaction with Rab9. J. Biol. Chem. 285:7794–7804 10.1074/jbc.M109.069088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klöpper T.H., Kienle N., Fasshauer D., Munro S. 2012. Untangling the evolution of Rab G proteins: implications of a comprehensive genomic analysis. BMC Biol. 10:71 10.1186/1741-7007-10-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knödler A., Feng S., Zhang J., Zhang X., Das A., Peränen J., Guo W. 2010. Coordination of Rab8 and Rab11 in primary ciliogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:6346–6351 10.1073/pnas.1002401107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Tsai Y.C., Mattera R., Smith W.J., Kostelansky M.S., Weissman A.M., Bonifacino J.S., Hurley J.H. 2006. Structural basis for ubiquitin recognition and autoubiquitination by Rabex-5. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13:264–271 10.1038/nsmb1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine T.P., Daniels R.D., Wong L.H., Gatta A.T., Gerondopoulos A., Barr F.A. 2013. Discovery of new Longin and Roadblock domains that form platforms for small GTPases in Ragulator and TRAPP-II. Small GTPases. 4:62–69 10.4161/sgtp.24262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska A., Macfarlane J., Shaw J.M. 2013. Mitochondrial association, protein phosphorylation, and degradation regulate the availability of the active Rab GTPase Ypt11 for mitochondrial inheritance. Mol. Biol. Cell. 24:1185–1195 10.1091/mbc.E12-12-0848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J.P., Stone S., Jiang Y., Lyons P., Ferro-Novick S. 1994. Ypt1p implicated in v-SNARE activation. Nature. 372:698–701 10.1038/372698a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch-Day M.A., Bhandari D., Menon S., Huang J., Cai H., Bartholomew C.R., Brumell J.H., Ferro-Novick S., Klionsky D.J. 2010. Trs85 directs a Ypt1 GEF, TRAPPIII, to the phagophore to promote autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:7811–7816 10.1073/pnas.1000063107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martincic I., Peralta M.E., Ngsee J.K. 1997. Isolation and characterization of a dual prenylated Rab and VAMP2 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 272:26991–26998 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattera R., Bonifacino J.S. 2008. Ubiquitin binding and conjugation regulate the recruitment of Rabex-5 to early endosomes. EMBO J. 27:2484–2494 10.1038/emboj.2008.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattera R., Tsai Y.C., Weissman A.M., Bonifacino J.S. 2006. The Rab5 guanine nucleotide exchange factor Rabex-5 binds ubiquitin (Ub) and functions as a Ub ligase through an atypical Ub-interacting motif and a zinc finger domain. J. Biol. Chem. 281:6874–6883 10.1074/jbc.M509939200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride H.M., Rybin V., Murphy C., Giner A., Teasdale R., Zerial M. 1999. Oligomeric complexes link Rab5 effectors with NSF and drive membrane fusion via interactions between EEA1 and syntaxin 13. Cell. 98:377–386 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81966-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNew J.A., Parlati F., Fukuda R., Johnston R.J., Paz K., Paumet F., Söllner T.H., Rothman J.E. 2000. Compartmental specificity of cellular membrane fusion encoded in SNARE proteins. Nature. 407:153–159 10.1038/35025000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miertzschke M., Koerner C., Vetter I.R., Keilberg D., Hot E., Leonardy S., Søgaard-Andersen L., Wittinghofer A. 2011. Structural analysis of the Ras-like G protein MglA and its cognate GAP MglB and implications for bacterial polarity. EMBO J. 30:4185–4197 10.1038/emboj.2011.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno-Yamasaki E., Medkova M., Coleman J., Novick P. 2010. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate controls both membrane recruitment and a regulatory switch of the Rab GEF Sec2p. Dev. Cell. 18:828–840 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno-Yamasaki E., Rivera-Molina F., Novick P. 2012. GTPase networks in membrane traffic. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81:637–659 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052810-093700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova N., Liang Y., Tokarev A.A., Chen S.H., Cox R., Andrejic J., Lipatova Z., Sciorra V.A., Emr S.D., Segev N. 2006. TRAPPII subunits are required for the specificity switch of a Ypt-Rab GEF. Nat. Cell Biol. 8:1263–1269 10.1038/ncb1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S., Liu X., Arasaki K., McDonough J., Galán J.E., Roy C.R. 2011. Modulation of Rab GTPase function by a protein phosphocholine transferase. Nature. 477:103–106 10.1038/nature10335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M.P., Peters H., Blümer J., Blankenfeldt W., Goody R.S., Itzen A. 2010. The Legionella effector protein DrrA AMPylates the membrane traffic regulator Rab1b. Science. 329:946–949 10.1126/science.1192276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S. 2002. Organelle identity and the targeting of peripheral membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14:506–514 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00350-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neunuebel M.R., Chen Y., Gaspar A.H., Backlund P.S., Jr, Yergey A., Machner M.P. 2011. De-AMPylation of the small GTPase Rab1 by the pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science. 333:453–456 10.1126/science.1207193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann M., Cabrera M., Perz A., Bröcker C., Ostrowicz C., Engelbrecht-Vandré S., Ungermann C. 2010. The Mon1-Ccz1 complex is the GEF of the late endosomal Rab7 homolog Ypt7. Curr. Biol. 20:1654–1659 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottingham R.M., Ganley I.G., Barr F.A., Lambright D.G., Pfeffer S.R. 2011. RUTBC1 protein, a Rab9A effector that activates GTP hydrolysis by Rab32 and Rab33B proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286:33213–33222 10.1074/jbc.M111.261115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottingham R.M., Pusapati G.V., Ganley I.G., Barr F.A., Lambright D.G., Pfeffer S.R. 2012. RUTBC2 protein, a Rab9A effector and GTPase-activating protein for Rab36. J. Biol. Chem. 287:22740–22748 10.1074/jbc.M112.362558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak B., Tyson J.J. 1993. Numerical analysis of a comprehensive model of M-phase control in Xenopus oocyte extracts and intact embryos. J. Cell Sci. 106:1153–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P., Field C., Schekman R. 1980. Identification of 23 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 21:205–215 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz D., Medkova M., Walch-Solimena C., Novick P. 2002. Ypt32 recruits the Sec4p guanine nucleotide exchange factor, Sec2p, to secretory vesicles; evidence for a Rab cascade in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 157:1005–1015 10.1083/jcb.200201003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S.R. 2001. Rab GTPases: specifying and deciphering organelle identity and function. Trends Cell Biol. 11:487–491 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02147-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S.R. 2013. Rab GTPase regulation of membrane identity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 25:1–6 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevoy G., Wei H.C., Wong R., Szentpetery Z., Kim Y.J., Goldbach P., Steinbach S.K., Balla T., Brill J.A. 2009. Dual roles for the Drosophila PI 4-kinase four wheel drive in localizing Rab11 during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 187:847–858 10.1083/jcb.200908107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerening J.R., Sontag E.D., Ferrell J.E., Jr 2003. Building a cell cycle oscillator: hysteresis and bistability in the activation of Cdc2. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:346–351 10.1038/ncb954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteryaev D., Datta S., Ackema K., Zerial M., Spang A. 2010. Identification of the switch in early-to-late endosome transition. Cell. 141:497–508 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A., Seals D., Wickner W., Ungermann C. 2000. The docking stage of yeast vacuole fusion requires the transfer of proteins from a cis-SNARE complex to a Rab/Ypt protein. J. Cell Biol. 148:1231–1238 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusapati G.V., Luchetti G., Pfeffer S.R. 2012. Ric1-Rgp1 complex is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the late Golgi Rab6A GTPase and an effector of the medial Golgi Rab33B GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 287:42129–42137 10.1074/jbc.M112.414565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pylypenko O., Rak A., Durek T., Kushnir S., Dursina B.E., Thomae N.H., Constantinescu A.T., Brunsveld L., Watzke A., Waldmann H., et al. 2006. Structure of doubly prenylated Ypt1:GDI complex and the mechanism of GDI-mediated Rab recycling. EMBO J. 25:13–23 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X., Kaneda M., Chen J., Geitmann A., Zheng H. 2011. A specific role for Arabidopsis TRAPPII in post-Golgi trafficking that is crucial for cytokinesis and cell polarity. Plant J. 68:234–248 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recacha R., Boulet A., Jollivet F., Monier S., Houdusse A., Goud B., Khan A.R. 2009. Structural basis for recruitment of Rab6-interacting protein 1 to Golgi via a RUN domain. Structure. 17:21–30 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C.J., Jones S., Litt R.J., Segev N. 1998. GTP hydrolysis is not important for Ypt1 GTPase function in vesicular transport. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:827–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink J., Ghigo E., Kalaidzidis Y., Zerial M. 2005. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell. 122:735–749 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Molina F.E., Novick P.J. 2009. A Rab GAP cascade defines the boundary between two Rab GTPases on the secretory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:14408–14413 10.1073/pnas.0906536106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinett C.C., Giansanti M.G., Gatti M., Fuller M.T. 2009. TRAPPII is required for cleavage furrow ingression and localization of Rab11 in dividing male meiotic cells of Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 122:4526–4534 10.1242/jcs.054536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A., Novick P.J. 1987. A ras-like protein is required for a post-Golgi event in yeast secretion. Cell. 49:527–538 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90455-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapperstein S.K., Lupashin V.V., Schmitt H.D., Waters M.G. 1996. Assembly of the ER to Golgi SNARE complex requires Uso1p. J. Cell Biol. 132:755–767 10.1083/jcb.132.5.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Sato K., Fonarev P., Huang C.J., Liou W., Grant B.D. 2005. Caenorhabditis elegans RME-6 is a novel regulator of RAB-5 at the clathrin-coated pit. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:559–569 10.1038/ncb1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoebel S., Oesterlin L.K., Blankenfeldt W., Goody R.S., Itzen A. 2009. RabGDI displacement by DrrA from Legionella is a consequence of its guanine nucleotide exchange activity. Mol. Cell. 36:1060–1072 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciorra V.A., Audhya A., Parsons A.B., Segev N., Boone C., Emr S.D. 2005. Synthetic genetic array analysis of the PtdIns 4-kinase Pik1p identifies components in a Golgi-specific Ypt31/rab-GTPase signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:776–793 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev N. 1991. Mediation of the attachment or fusion step in vesicular transport by the GTP-binding Ypt1 protein. Science. 252:1553–1556 10.1126/science.1904626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev N., Mulholland J., Botstein D. 1988. The yeast GTP-binding YPT1 protein and a mammalian counterpart are associated with the secretion machinery. Cell. 52:915–924 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90433-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semerdjieva S., Shortt B., Maxwell E., Singh S., Fonarev P., Hansen J., Schiavo G., Grant B.D., Smythe E. 2008. Coordinated regulation of AP2 uncoating from clathrin-coated vesicles by rab5 and hRME-6. J. Cell Biol. 183:499–511 10.1083/jcb.200806016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Shen Q.T., Kiel A., Wang J., Wang H.W., Melia T.J., Rothman J.E., Pincet F. 2012. SNARE proteins: one to fuse and three to keep the nascent fusion pore open. Science. 335:1355–1359 10.1126/science.1214984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorter J., Beard M.B., Seemann J., Dirac-Svejstrup A.B., Warren G. 2002. Sequential tethering of Golgins and catalysis of SNAREpin assembly by the vesicle-tethering protein p115. J. Cell Biol. 157:45–62 10.1083/jcb.200112127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivars U., Aivazian D., Pfeffer S.R. 2003. Yip3 catalyses the dissociation of endosomal Rab-GDI complexes. Nature. 425:856–859 10.1038/nature02057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklan E.H., Serrano R.L., Einav S., Pfeffer S.R., Lambright D.G., Glenn J.S. 2007. TBC1D20 is a Rab1 GTPase-activating protein that mediates hepatitis C virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 282:36354–36361 10.1074/jbc.M705221200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søgaard M., Tani K., Ye R.R., Geromanos S., Tempst P., Kirchhausen T., Rothman J.E., Söllner T. 1994. A rab protein is required for the assembly of SNARE complexes in the docking of transport vesicles. Cell. 78:937–948 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90270-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M.P., Müller M.P., Wandinger-Ness A. 2012. Bacterial pathogens commandeer Rab GTPases to establish intracellular niches. Traffic. 13:1565–1588 10.1111/tra.12000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz T.A. 2008. A structural understanding of the dynamic ribosome machine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:242–253 10.1038/nrm2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Anderl F., Fröhlich K., Zhao L., Hanke S., Brügger B., Wieland F., Béthune J. 2007. Multiple and stepwise interactions between coatomer and ADP-ribosylation factor-1 (Arf1)-GTP. Traffic. 8:582–593 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00554.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Ohbayashi N., Maruta Y., Kanno E., Itoh T., Fukuda M. 2009. Varp is a novel Rab32/38-binding protein that regulates Tyrp1 trafficking in melanocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:2900–2908 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y., Luo Z.Q. 2011. Legionella pneumophila SidD is a deAMPylase that modifies Rab1. Nature. 475:506–509 10.1038/nature10307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson J.J., Chen K., Novak B. 2001. Network dynamics and cell physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:908–916 10.1038/35103078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungermann C., Price A., Wickner W. 2000. A new role for a SNARE protein as a regulator of the Ypt7/Rab-dependent stage of docking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:8889–8891 10.1073/pnas.160269997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluijs P., Hull M., Huber L.A., Mâle P., Goud B., Mellman I. 1992. Reversible phosphorylation—dephosphorylation determines the localization of rab4 during the cell cycle. EMBO J. 11:4379–4389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz G.K., Prinz W.A., Shibata Y., Rist J.M., Rapoport T.A. 2006. A class of membrane proteins shaping the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 124:573–586 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Seeley E.S., Wickner W., Merz A.J. 2002. Vacuole fusion at a ring of vertex docking sites leaves membrane fragments within the organelle. Cell. 108:357–369 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00632-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Sacher M., Ferro-Novick S. 2000. TRAPP stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on Ypt1p. J. Cell Biol. 151:289–296 10.1083/jcb.151.2.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Bradley M.J., Cai Y., Kümmel D., De La Cruz E.M., Barr F.A., Reinisch K.M. 2011. Insights regarding guanine nucleotide exchange from the structure of a DENN-domain protein complexed with its Rab GTPase substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:18672–18677 10.1073/pnas.1110415108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.W., Oesterlin L.K., Tan K.T., Waldmann H., Alexandrov K., Goody R.S. 2010. Membrane targeting mechanism of Rab GTPases elucidated by semisynthetic protein probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6:534–540 10.1038/nchembio.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Matern H.T., Gallwitz D. 1998. Specific binding to a novel and essential Golgi membrane protein (Yip1p) functionally links the transport GTPases Ypt1p and Ypt31p. EMBO J. 17:4954–4963 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura S., Gerondopoulos A., Linford A., Rigden D.J., Barr F.A. 2010. Family-wide characterization of the DENN domain Rab GDP-GTP exchange factors. J. Cell Biol. 191:367–381 10.1083/jcb.201008051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerial M., McBride H. 2001. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:107–117 10.1038/35052055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Iyer L.M., He F., Aravind L. 2012. Discovery of novel DENN proteins: implications for the evolution of eukaryotic intracellular membrane structures and human disease. Front Genet. 3:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., He X., Fu X.Y., Chang Z. 2006. Varp is a Rab21 guanine nucleotide exchange factor and regulates endosome dynamics. J. Cell Sci. 119:1053–1062 10.1242/jcs.02810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]