Abstract

The yellow dwarf viruses (YDVs) of the Luteoviridae family represent the most widespread group of cereal viruses worldwide. They include the Barley yellow dwarf viruses (BYDVs) of genus Luteovirus, the Cereal yellow dwarf viruses (CYDVs) and Wheat yellow dwarf virus (WYDV) of genus Polerovirus. All of these viruses are obligately aphid transmitted and phloem-limited. The first described YDVs (initially all called BYDV) were classified by their most efficient vector. One of these viruses, BYDV-RMV, is transmitted most efficiently by the corn leaf aphid, Rhopalosiphum maidis. Here we report the complete 5612 nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of a Montana isolate of BYDV-RMV (isolate RMV MTFE87, Genbank accession no. KC921392). The sequence revealed that BYDV-RMV is a polerovirus, but it is quite distantly related to the CYDVs or WYDV, which are very closely related to each other. Nor is BYDV-RMV closely related to any other particular polerovirus. Depending on the gene that is compared, different poleroviruses (none of them a YDV) share the most sequence similarity to BYDV-RMV. Because of its distant relationship to other YDVs, and because it commonly infects maize via its vector, R. maidis, we propose that BYDV-RMV be renamed Maize yellow dwarf virus-RMV (MYDV-RMV).

Keywords: Luteoviridae phylogenetics, P0, maize yellow dwarf virus, maize virus, rhopalosiphum maidis, luteovirid

Introduction

Barley yellow dwarf viruses (BYDVs), Wheat yellow dwarf virus (WYDV), and Cereal yellow dwarf viruses (CYDVs), collectively known as yellow dwarf viruses (YDVs) are among the most economically important causal agents of disease in cereal crops. YDVs have been reported in both agriculturally important cereal crops and non-crop grasses throughout the world (El-Muadhidi et al., 2001; Hawkes and Jones, 2005; Hesler et al., 2005; Kumari et al., 2006; Power et al., 2011; Siddiqui et al., 2012; Jarošová et al., 2013). YDVs vectored primarily by the bird cherry-oat aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi, can cause yield reductions of 15 to 25% in barley, wheat and oat (Lister and Ranieri, 1995). The presence of BYDV correlated with a reduction in yield of winter wheat (Banks et al., 1995) as well as wheat and oats (McKirdy et al., 2002). Perry et al. (Perry et al., 2000) found an average of 30% yield loss in affected winter wheat fields. Significant agricultural research efforts are aimed at reducing the impact of the YDVs on the yield of the various crop systems by (i) altering planting time and/or pesticide application regimes to avoid the accumulation of high densities of aphids, (ii) tilling practices, and (iii) developing virus-resistance crop varieties (Chain et al., 2005; Royer et al., 2005; Kennedy and Connery, 2012).

The YDVs are members of the Luteoviridae family. All members of the Luteoviridae (luteovirids) have linear, positive-sense, 5.5–6 kb RNA genomes and are obligately aphid-transmitted in a circulative, persistent manner, with the exception of Pea enation mosaic virus 1 (PEMV1), which is mechanically transmissible in the presence of the umbravirus, PEMV2. The key genes conserved in all luteovirids are the major coat protein (CP) and readthrough domain (RTD) generated by translational readthrough of the CP open reading frame (ORF) stop codon, which provides a long carboxy-terminal extension to the CP (Brault et al., 1995; Brown et al., 1996). The CP and CP-RTD proteins provide the virion structure and aphid transmission properties, and they play a role in virus movement and tissue specificity within the plant (Brault et al., 1995; Chay et al., 1996a; Van Den Heuvel et al., 1997; Peter et al., 2009). ORF 4, which is embedded in the CP ORF but in a different reading frame, is also conserved in all luteovirids, except PEMV1. The product of ORF 4 (P4) has features of a cell-to-cell movement protein (Chay et al., 1996a; Schmitz et al., 1997), which may confer the property that all Luteoviridae except PEMV1 are confined to the phloem. Because the sequence encoding CP-RTD and P4 is the only part of the genome conserved in all luteovirids with the aforementioned exception of PEMV1, we call this region the Luteoviridae block (Miller et al., 2002).

Luteoviridae fall into three genera: Luteovirus, Polerovirus, and Enamovirus (Domier, 2012). Outside of the Luteoviridae block, the viral genomes are completely different between Polerovirus and Luteovirus genera. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) genes (the key gene used for virus classification) of poleroviruses and the only enamovirus (PEMV1) are similar to each other but quite distantly related to those of genus Luteovirus (Miller et al., 2002; Domier, 2012). The polero/enamovirus RdRps are more similar to those of genus Sobemovirus, which has not been assigned to a family, than to those of genus Luteovirus. Moreover, outside of the Luteoviridae block, the genomes of genus Luteovirus (including the RdRp ORF) are most closely related to those of genus Dianthovirus in the Tombusviridae (Miller et al., 2002). In particular, the RdRp and translational control signals of genus Luteovirus resemble those of the Tombusviridae more than they resemble those of the Polerovirus or Enamovirus genera. Moreover, poleroviruses and the enamovirus contain a genome-linked protein (VPg), and also encode a viral suppressor of gene silencing (VSR) in ORF 0 (Pfeffer et al., 2002; Mangwende et al., 2009). Viruses in genus Luteovirus, like the Tombusviridae, have neither a VPg nor an ORF 0.

The original YDVs identified as the causal agents of yellow dwarf disease were all called BYDV and placed into five strains (now considered species) based on serotype, symptomatology and predominant aphid vector species (Rochow, 1969; Rochow and Muller, 1971). BYDV-RPV, -MAV, -SGV, and -RMV were found to be transmitted most efficiently by R. padi, Sitobion avenae, Schizaphus graminum and R. maidis, respectively. The most common virus is BYDV-PAV which is transmitted efficiently by R. padi and S. avenae (Rochow, 1969; Rochow and Muller, 1971).

Upon sequencing the complete genomes of some of the BYDV strains, it became clear that BYDV-RPV is a Polerovirus, renamed Cereal yellow dwarf (CYDV)-RPV, while BYDV-PAV and BYDV-MAV which have virtually identical RdRp sequences, are in genus Luteovirus. More recently discovered YDVs include CYDV-RPS, a CYDV-RPV-like virus that causes cork screw-shaped leaves and leaf notching in wheat; the former BYDV-GPV (now Wheat yellow dwarf virus-GPV (WYDV-GPV) (Zhang et al., 2009); and BYDV-PAS, a severe BYDV-PAV-like virus that breaks resistance in oat (Chay et al., 1996b).

In addition to the BYDVs, the genus Luteovirus includes Bean leafroll virus (BLRV), Soybean dwarf virus (SbDV), and (unofficially) Rose spring dwarf-associated virus (RSDaV). In addition to the CYDVs, the Polerovirus genus includes about two dozen viruses of diverse crops. Subsequently additional species have been identified in China, such as BYDV-GAV, and WYDV-GPV, transmitted primarily by S. graminum and S. avenae, and S. graminum and R. padi, respectively, and BYDV-PAV-CN which is transmitted efficiently by all three aphid species (Jin et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). BYDV-GAV is very similar to BYDV-MAV (Jin et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2009), WYDV-GPV is closely related to CYDV-RPV (Lucio-Zavaleta et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2009), while BYDV-PAV-CN is highly diverged from other BYDVs (Liu et al., 2007). It should be noted that the vector specificity of the YDVs can vary by isolate within a virus species, by genotype of an aphid species, or under different environmental conditions (Lucio-Zavaleta et al., 2001). Thus, the YDVs are now classified by nucleotide sequence identity and genome organization, rather than by the most efficient aphid vector.

Until this report, the complete BYDV-RMV genome had not been sequenced, only the nucleotide region encoding the coat protein had been reported (Geske et al., 1996; Domier et al., 1997). RMV is the only BYDV transmitted efficiently by R. maidis, the corn leaf aphid. Hence it infects maize (Itnyre et al., 1999a,b). Moreover, maize serves as a reservoir for BYDV-RMV from which it can be transmitted to nearby wheat plots where stunting and yield losses ensue (Brown et al., 1984). BYDVs can reduce sweet corn yield dramatically by causing incomplete ear filling which can render entire harvests unmarketable (Beuve et al., 1999; Itnyre et al., 1999b). BYDV-RMV virions are difficult to purify, hence it has been little studied. Here, we report the first complete sequence of a BYDV-RMV genome. The genome organization and sequence of the RMV MTFE87 isolate indicates that BYDV-RMV is a member of genus Polerovirus, but it is not closely related to the CYDVs, WYDV or any other polerovirus. Therefore, we submit that BYDV-RMV is a unique species, with the proposed new name Maize yellow dwarf virus (MYDV).

Materials and methods

Biological characterization

The RMV MTFE87 isolate was obtained from Dr. T. W. Carroll, Montana State University in 1990. It was originally collected from an infected wheat plant growing on the Fort Ellis Experiment Station of Montana State University in 1987. The isolate has been continually propagated in Coast Black oats by regular transfer to new plants using R. maidis. Serological and aphid transmission properties of RMV MTFE87 were determined using a collection of antibodies to each of the YDV strains (Rochow and Carmichael, 1979; Webby and Lister, 1992). Double antibody sandwich (DAS) ELISA was carried out as described previously (Brumfield et al., 1992). Five different aphid species were used to determine the vector specificity of the RMV MTFE87 isolate. R. maidis, R. padi, S. avenae, S. graminum were previously described (Rochow and Carmichael, 1979; Power and Gray, 1995) and have been maintained as clonal lineages in the laboratory since their collection. The Metapalophium dirhodum colony was a gift from Fred Gildow (Gildow, 1993) and has been maintained in the laboratory in Ithaca, NY since 1993. Fourth instar or adult apterous aphids were allowed a 36–48 h acquisition access period on detached leaves of Coast Black oat plants infected with RMV MTFE87 4–5 weeks previously. Ten aphids were subsequently transferred to each of eight plants for a 72 h inoculation access period. Plants were fumigated and grown in a greenhouse and observed for symptoms for 3–4 weeks and tested using DAS-ELISA.

Virus purification and viral RNA extraction

Virions were extracted from infected Coast Black oat plants as described previously (Hammond et al., 1983; Webby and Lister, 1992). Viral RNA was extracted using the hot phenol method. All centrifugation was at 13,200 rpm (16,100 × g) in a 24 × 1.5 ml tube rotor in an Eppendorf 5415R centrifuge. Briefly: purified virions were added to 3 volumes of extraction buffer yielding a final concentration of 167 mM Tris base (pH 8.5), 1% SDS, and 12.5 mM EDTA (all reagents from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Hot (65°C) phenol was then added equal to the total volume, and after vortexing, the solution was incubated at 65°C for 15 min. The solution was vortexed again, centrifuged, and the aqueous phase saved. The phenol phase was back extracted using the above extraction buffer lacking SDS. After vortexing and centrifugation, the second aqueous phase was combined with the first. The combined aqueous phases were then extracted twice with equal volumes of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). The RNA was precipitated at −20°C after adding 1/15 volume 3M sodium acetate (pH 5.5) and 2.5 volumes 95% ethanol. After centrifugation, the pellet was washed in 70% ethanol, vacuum dried and dissolved in a small volume of nuclease-free water.

Amplification of genome downstream of the viral coat protein (CP)

The 3′ terminal region (1788 base pairs) of RMV MTFE87 was amplified and prepared for cloning using ligated-anchor PCR (LA-PCR) according to published protocols (Beckett and Miller, 2007). LA-PCR was performed on purified RMV MTFE87 viral RNA (500 ng). An anchor oligomer (5′-CTATAGTGTCACCTAAATGCGTGAAGAGCCTCCTACCAGCTGCTCCTATG-3′) was ligated directly to the 3′ end of the viral RNA. PCR amplification was conducted using an upstream primer (5′-AGATCACAAAAGTCATACTGGAGTTCATCT-3′) homologous to the viral coat protein (CP) and a downstream primer (5′-CATAGGAGCAGCTGGTAGGAGGCTCTTC-3′) complementary to the anchor.

Amplification of genome upstream of the viral coat protein

Overlapping genomic sections extending from the viral CP to the 5′ end of the genome were amplified and prepared for cloning using the SMART™ RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech) according to manufacturer's instructions. The following viral-specific primers were used in conjunction with the kit to walk step-by-step to the 5′ end of the genome: 5′-ATGCGAGGGTGCTGAGCTTGTTGTG-3′, 5′-GGATGTCATCCTCATCATCAGCCCAGTTTC-3′, 5′-AGCCGGAGTTGGAAGCGTTTATAGC-3′.

Cloning and sequencing of viral genome fragments

PCR amplified genome fragments were cloned using the Zero Blunt® TOPO® PCR Cloning Kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Chimeric plasmids were purified from positive transformants. The cloned viral fragments were sequenced either by primer-walking or by 96-well sequencing on an ABI 3730 × l DNA Analyzer at the ISU DNA Sequencing Facility. Plasmid template was transposon tagged in preparation for sequencing using the Template Generation System™ II (Finnzymes) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Sequence assembly and analysis

The Phred, Phrap, and Consed software programs were used in tandem to process and assemble raw sequencing reads for all clones which were sequenced in a 96-well plate format (Ewing and Green, 1998; Gordon et al., 1998). Vector NTI® (Invitrogen) was used to assemble the sequence reads from primer-walked clones. The complete nucleotide sequence of the RMV MTFE87 genome, as well as the amino acid sequences of all six major proteins, were compared with a range of other fully sequenced luteovirids (Table 1). The sequences were organized within the JalView alignment editor, version 2.4 (Clamp et al., 2004). The full length genomes were aligned with Clustal W (Thompson et al., 1994). The amino acid sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm (Edgar, 2004). Phylogenetic relationships were inferred from these alignments using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1000 replicates for bootstrapping in the MEGA4 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 4.0) software package (Tamura et al., 2007). Sequence identity was determined via the Needleman-Wunsch global alignment in the EMBOSS Pairwise Alignment Algorithms, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/emboss/align/index.html.

Table 1.

Virus abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers for viruses used for sequence comparisons in this study.

| Virus name | Abbreviation | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| Barley yellow dwarf virus—GAV | BYDV-GAV | NC_004666 |

| Barley yellow dwarf virus—MAV | BYDV-MAV | NC_003680 |

| Barley yellow dwarf virus—PAS | BYDV-PAS | NC_002160 |

| Barley yellow dwarf virus—PAV | BYDV-PAV | NC_004750 |

| Bean leafroll virus | BLRV | NC_003369 |

| Beet chlorosis virus | BChV | NC_002766 |

| Beet mild yellowing virus | BMYV | NC_003491 |

| Beet western yellows virus | BWYV | NC_004756 |

| Carrot red leaf virus | CtRLV | NC_006265 |

| Cereal yellow dwarf virus—RPS | CYDV-RPS | NC_002198 |

| Cereal yellow dwarf virus—RPV | CYDV-RPV | NC_004751 |

| Chickpea chlorotic stunt virus | ChCSV | NC_008249 |

| Cucurbit aphid-borne yellows virus | CABYV | NC_003688 |

| Melon aphid-borne yellows virus | MABYV | NC_010809 |

| Pea enation mosaic virus 1 | PEMV1 | NC_003629 |

| Potato leafroll virus | PLRV | NC_001747 |

| Barley yellow dwarf virus-RMV (proposed new name: Maize yellow dwarf virus-RMV) | BYDV-RMV (MYDV-RMV) | KC921392 |

| Rose spring dwarf-associated virus | RSDaV | NC_010806 |

| Soybean dwarf virus | SbDV | NC_003056 |

| Sugarcane yellow leaf virus | ScYLV | NC_000874 |

| Tobacco vein distorting virus | TVDV | NC_010732 |

| Turnip yellows virus | TuYV | NC_003431 |

| Wheat yellow dwarf virus—GPV | WYDV-GPV | NC_012931 |

Results

Biological characterization of the RMV MTFE87 isolate

BYDV-RMV MTFE87 reacted in DAS-ELISA with antibodies to BYDV-RMV, but not to antibodies made against the other viruses (BYDV-PAV, BYDV-MAV, BYDV-SGV or CYDV-RPV). RMV MTFE87 was transmitted efficiently by R. maidis to eight of eight plants, to a lesser extent by S. graminum (4/8) and R. padi (1/8) and was not transmitted by Metapalophium dirhodum or S. avenae (both 0/8) FE87 was passaged six times in Coast Black oats using 10 R. maidis or S. graminum apterous adults for each passage. Transmission efficiency remained at 100% for R. maidis and increased to 95% for S. graminum by the sixth serial passage. The virus continued to react only with anti-BYDV-RMV antibodies following all of the serial passages by either aphid. Symptoms induced by RMV MTFE87 isolate were more severe on oat and wheat than the type RMV isolate from NY (RMV-NY) (Rochow and Norman, 1961). The RMV-NY isolate rarely induces visible symptoms in wheat and many cultivars of oat. Symptoms in Coast Black oat are mild chlorosis or reddening of mature leaf tips, whereas the RMV MTFE87 isolate induced yellowing or reddening of flag leaves in wheat, noticeable stunting of the plants and incomplete filling of heads. Oat plants infected with RMV MTFE87 were severely stunted, with reddening and necrosis of leaves and incomplete formation of seed. The severe symptoms in oat and wheat are typical of RMV isolates collected in Montana (Brumfield et al., 1992) in contrast to RMV isolates collected in NY (Lucio-Zavaleta et al., 2001).

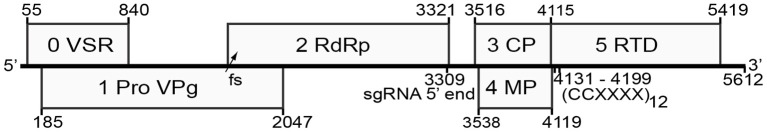

Genome organization of BYDV-RMV

The nucleotide sequence of RMV MTFE87 genomic RNA was found to be 5612 nt long, encoding six ORFs (Figure 1). The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) are 54 and 158 nt long, respectively, and the only intergenic region spans nucleotides 3322–3515. The arrangement and sequences of ORFs resemble those of poleroviruses (Figure 1, Table 2). Based on sequence comparisons with poleroviruses, the ORFs encode a putative viral suppressor of silencing (VSR, ORF 0), serine protease and VPg (both in ORF 1), RdRp (ORF 2), coat protein (ORF 3), putative movement protein (ORF 4, which overlaps with ORF 3), and the CP readthrough domain (ORF 5) (Figure 1). A feature found in only three other luteovirids—Chickpea chlorotic stunt virus (ChCSV), Melon aphid-borne yellows virus (MABYV), and Cucurbit aphid-borne yellows virus (CABYV), is that ORF 4 of BYDV-RMV extends beyond the end of ORF 3, in this case by 4 nt. In all other Luteoviridae, the stop codon of ORF 4 is upstream of the CP ORF stop codon.

Figure 1.

Genome organization of BYDV-RMV. Numbers in small font indicate genomic positions of each ORF (numbered in large font) and the position of the predicted subgenomic RNA 5′ end and the readthrough sequence. VPg, viral genome-linked protein; VSR, putative viral suppressor of RNA silencing; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; CP, coat protein; MP, movement protein; RTD, readthrough domain; fs, site of −1 ribosomal frameshift; sgRNA 5′ end, predicted 5′ end of subgenomic RNA1 at nt 3309; (CCXXXX)12, repeat motif required for readthrough of the CP ORF stop codon at nts 4131–4199.

Table 2.

Sequence identity (%)a of BYDV-RMV proteins to those of other luteovirids.

| Genus | Virusa | P0 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luteovirus | BLRV | NAb | 7 | 14 | 51 | 31 | 26 |

| Luteovirus | BYDV-GAV | NAb | 10 | 16 | 45 | 28 | 31 |

| Luteovirus | BYDV-MAV | NAb | 9 | 15 | 45 | 26 | 29 |

| Luteovirus | BYDV-PAS | NAb | 7 | 14 | 42 | 19 | 31 |

| Luteovirus | BYDV-PAV | NAb | 10 | 15 | 45 | 21 | 31 |

| Luteovirus | RSDaV | NAb | 2 | 19 | 32 | 25 | 31 |

| Luteovirus | SbDV | NAb | 7 | 14 | 51 | 38 | 26 |

| Polerovirus | BChV | 15 | 27 | 57 | 60 | 37 | 25 |

| Polerovirus | BMYV | 20 | 33 | 59 | 60 | 39 | 25 |

| Polerovirus | BWYV | 22 | 31 | 57 | 61 | 38 | 24 |

| Polerovirus | CABYV | 22 | 34 | 57 | 59 | 43 | 33 |

| Polerovirus | ChCSV | 18 | 30 | 60 | 59 | 37 | 29 |

| Polerovirus | CtRLV | 17 | 32 | 62 | 48 | 28 | 30 |

| Polerovirus | CYDV-RPS | 19 | 30 | 52 | 58 | 32 | 28 |

| Polerovirus | CYDV-RPV | 20 | 29 | 51 | 61 | 33 | 27 |

| Polerovirus | MABYV | 23 | 33 | 58 | 55 | 41 | 31 |

| Polerovirus | PLRV | 11 | 30 | 56 | 55 | 35 | 25 |

| Polerovirus | ScYLV | 18 | 30 | 56 | 40 | 29 | 37 |

| Polerovirus | TuYV | 21 | 39 | 64 | 61 | 38 | 26 |

| Polerovirus | TVDV | 23 | 32 | 62 | 53 | 31 | 26 |

| Polerovirus | WYDV-GPV | 20 | 30 | 53 | 59 | 35 | 27 |

| Enamovirus | PEMV1 | 23 | 18 | 37 | 30 | NAb | 30 |

The identity of the sequences to BYDV-RMV was determined with the EMBOSS Needle global pairwise alignment algorithm. Molecular weights for the BYDV-RMV proteins were estimated using the ExPASy Server (Gasteiger et al., 2003).

NA, not applicable.

Whole genome alignments of Luteoviridae

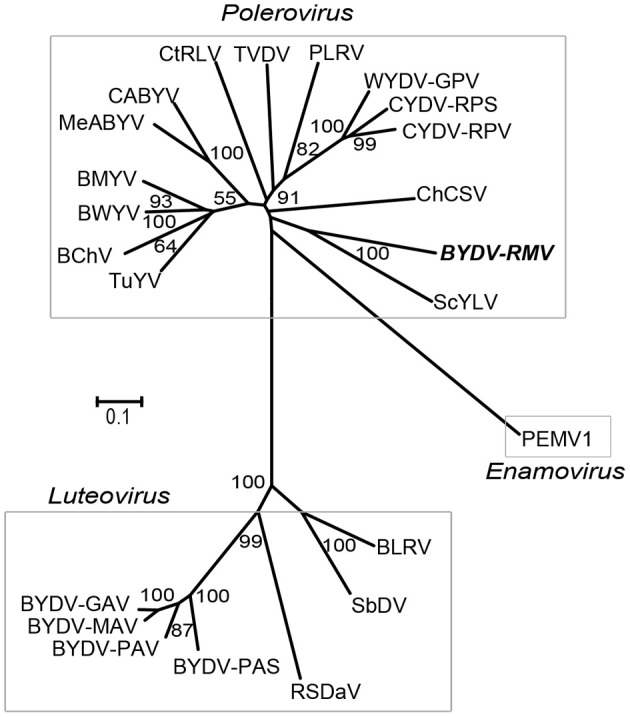

The full-length luteovirid genomes found in GenBank REFSEQ database were aligned by the neighbor-joining method using MEGA4 (Tamura et al., 2007) with 1000 replications (Figure 2). BYDV-RMV was grouped with the Polerovirus genus and in 100% of the replicates was closest to, but highly distinct from, Sugarcane yellow leaf virus (ScYLV). The BYDV-RMV/ScYLV branch was separated deeply from the CYDV and WYDV grouping indicating that BYDV-RMV is more closely related to other poleroviruses than it is to CYDVs and WYDV. As expected in this comparison, genus Luteovirus was well-separated from the Polerovirus and Enamovirus groups.

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining tree of Clustal W-aligned whole genome sequences of luteovirids generated in the MEGA 4 software package. Numbers representing bootstrap values when greater than 50% for 1000 replicates are shown.

Protein alignments and analyses of RMV MTFE87 and selected luteovirids

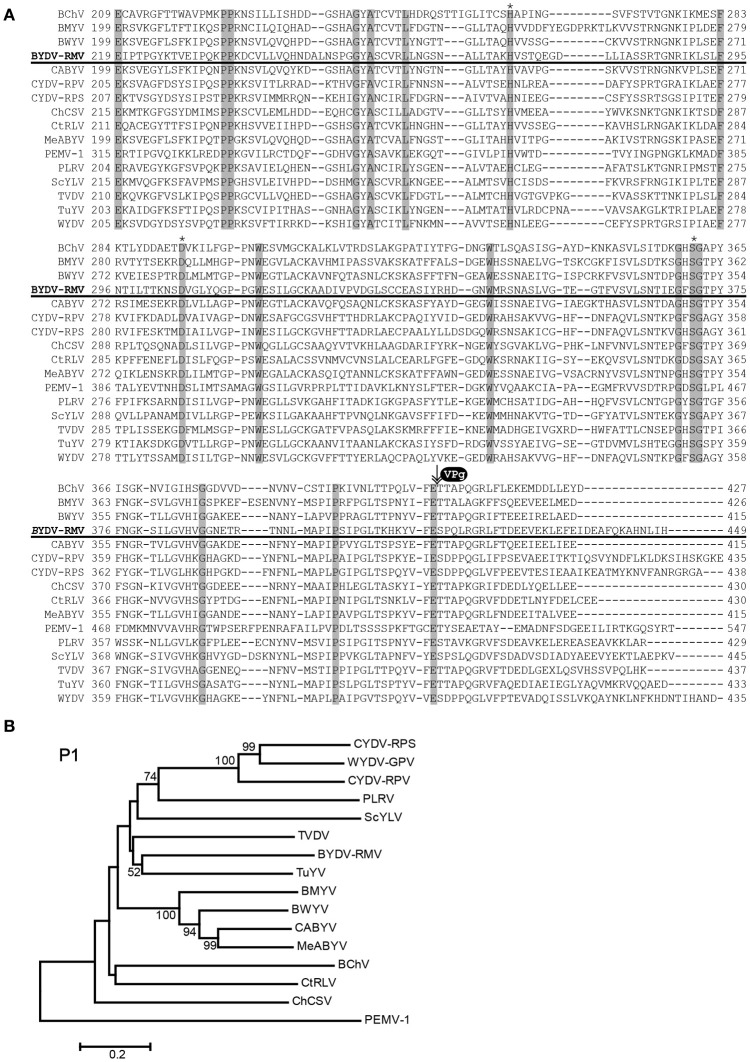

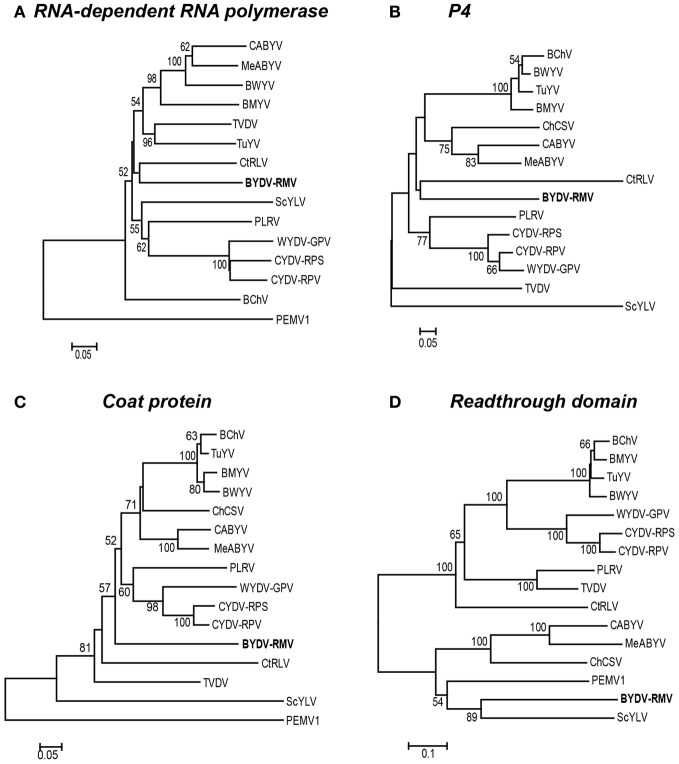

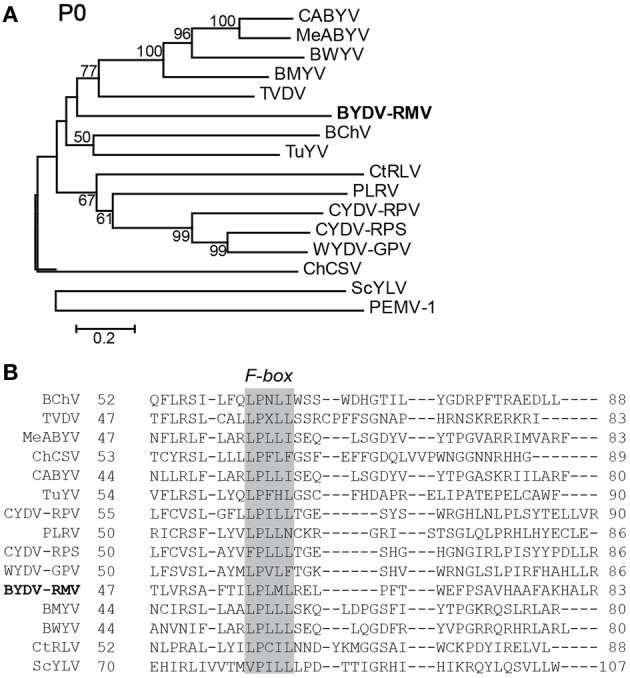

The amino acid sequences of selected polerovirus and enamovirus proteins were aligned using the MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) algorithm and from these alignments we created neighbor-joining trees via the MEGA4 software package (Tamura et al., 2007). P0 of RMV MTFE87 is separated readily from the CYDV/WYDV group and is most closely related to the Beet chlorosis virus (BChV)/Turnip yellows virus (TuYV) branch (Figure 3A). The CYDV-RPS, CYDV-RPV, and WYDV group separates from the remainder of the sequences in 99% of the bootstrap replicates.

Figure 3.

Analysis of P0 amino acid sequences. (A) Amino acid sequences of the P0s for viruses in the Polereovirus and Enamovirus genera were aligned with the MUSCLE algorithm within JalView. The aligned sequences were used for inferring evolutionary relationships using the Neighbor-Joining method. The resultant tree, drawn to scale, is shown with the percentage (greater than 50% only) of 1000 bootstrap replicates. (B) A portion of the MUSCLE aligned P0 showing the conserved F-box domain LPxxL/I among the Polerovirus members. Accession numbers of viral genome sequences used in the alignment are in Table 1.

P1 of poleroviruses is a polyprotein that is cleaved by its internal protease into functional polypeptides that include the N terminus, the protease, the VPg, and a downstream RNA-binding fragment of unknown function (Prüfer et al., 1999, 2006; Li et al., 2000). The key amino acids of the catalytic triad in the protease (Li et al., 2000) are at positions 272, 306 and 373 (Figure 4A). Based on the known N-termini of the Potato leafroll virus (PLRV) VPg (Van Der Wilk et al., 1997b) and the enamovirus PEMV1 (Wobus et al., 1998), the N-terminus of the VPg of RMV MTFE87 is predicted to be amino acid T417 (Figure 4A). RMV MTFE87 P1 is most closely related to P1 of TuYV and TVDV, distinct from the CYDV/WYDV group linked in 100% of the bootstrap replicates (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Analysis of P1 amino acid sequences. (A) Amino acid sequences of P1 were aligned with the MUSCLE algorithm within JalView. The region with the protease domain is shown. Shaded boxes indicated conserved amino acids. Asterisks indicate amino acids of the catalytic triad in the protease active site. VPg and arrow indicate predicted proteolytic cleavage site that forms the C-terminus of the protease and the N-terminus of the VPg. (B) The MUSCLE aligned P1s for virus in the Polerovirus and Enamovirus genera were used for inferring evolutionary relationships using the Neighbor-Joining method. The resultant tree, drawn to scale, is shown with the percentage (greater than 50% only) of 1000 bootstrap replicates.

In all studied poleroviruses, P2, which encodes the active site of the RdRp, is expressed only as a fusion with P1, as it is translated by frameshifting of ribosomes from ORF 1 to ORF 2 in the region of overlap (Prüfer et al., 1992; Kujawa et al., 1993; Miller and Giedroc, 2010). The CYDV/WYDV RdRp (P2) sequences clustered tightly in 100% of the replicates, but they all were strikingly distinct from RMV MTFE87 P2, which groups rather distantly with CtRLV (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationships of four luteoviral proteins. For each protein, the amino acid sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm in the JalView program and subsequently used to generate a Neighbor-Joining tree with the percentage of 1000 bootstrap replicates reported on a drawn-to-scale tree. Phylogenetic trees of: (A) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (P2), (B) putative movement protein of P4, (C) the major coat protein (P3), and (D) the readthrough domain (P5) are shown.

The relationship of the RMV MTFE87 CP to that of other poleroviruses is not well resolved. The CP sequences of PEMV1 (Enamovirus), and ScYLV are distinct from all of the remaining Polerovirus members, while 57 and 52% of bootstrap replicates support BYDV-RMV separation from TVDV and the large group of the remaining poleroviruses, respectively. But the close relatedness of the CYDV/WYDV CP to each other is present in 98% of the bootstrap replicates (Figure 5C).

The P4 proteins of TVDV and ScYLV are discretely separated from the remaining poleroviruses. BYDV-RMV and CtRLV form an intermediate between two larger clusters, one housing PLRV and CYDV/WYDV group while the other contains all others used in our study (Figure 5B). The readthrough domain, P5, is expressed as a fusion with the CP by leaky scanning through the amber stop codon of P3 (Brault et al., 1995; Brown et al., 1996). For the RTD, the Polerovirus and Enamovirus members branch into two distinct clades. RMV MTFE87 P5 groups with Sugarcane yellow leaf virus (ScYLV), CABYV, MABYV, ChCSV and PEMV1, in one clade. The remaining poleroviruses are in the other major clade including the CYDV/WYDV group present in 100% of bootstrap replicates (Figure 5D).

Discussion

Proteins of the Luteoviridae

P0 of RMV MTFE87 is a putative viral suppressor of RNA silencing (VSR) because it shares homology with other poleroviruses in which P0 is a VSR. P0 of TuYV (formerly Beet western yellows virus-FL, BWYV-FL), PLRV and PEMV1 has been shown to suppress the host plant's defensive posttranscriptional gene silencing (PTGS) system (Pfeffer et al., 2002; Mangwende et al., 2009; Fusaro et al., 2012) by inducing the host to degrade the key Argonaute 1 (AGO1) protein (Baumberger et al., 2007; Bortolamiol et al., 2007). The F-box domain, LPxxL/I, which is conserved in the otherwise highly variable P0 of all luteovirids including BYDV-RMV (Figure 3B), is required for VSR activity, as it recruits proteins to form the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity that ubiquitylates AGO1, which leads to its degradation (Pazhouhandeh et al., 2006; Bortolamiol et al., 2007) by the autophagy pathway (Derrien et al., 2012). Moreover, transgenic expression of ORF0 of PLRV in potatoes, but not Nicotiana, is sufficient to produce virus-like symptoms (Van Der Wilk et al., 1997a). However, not all P0 proteins show VSR activity, for example those of Beet chlorosis virus (BChV) and some strains of Beet mild yellowing virus (BMYV) (Kozlowska-Makulska et al., 2010) and CYDV-RPV (Véronique Ziegler-Graff, personal communication) do not display VSR activity in standard assays. Thus, VSR function may vary depending on the virus strain–host species interaction.

The putative movement proteins of BYDV (Chay et al., 1996a,b) and PLRV (Lee et al., 2002) encoded by ORF 4 have been shown to allow host-dependent movement of the virus throughout the plant. P4 of BYDV-GAV was reported to contain an RNA-binding motif at its C-terminus with four arginine residues (Xia et al., 2008). The P4 proteins of other luteovirids were also shown to contain multiple arginine residues. In line with these observations, there are four arginine residues within the C-terminal 11 amino acids of the RMV P4 sequence.

Modular evolution of Luteoviridae

As has been apparent since the first luteoviruses were sequenced, it is clear that luteovirid genes evolve at different rates. Note the striking lack of sequence homology among the P0 proteins (other than the F-box motif) which have around 15–23% homology to that of RMV MTFE87 (Table 2). This high sequence divergence of VSRs relative to other ORFs in related viruses occurs in other virus families with VSRs that act by entirely different mechanisms (Nayak et al., 2010). We speculate that VSRs are at the forefront of the evolutionary back-and-forth between virus and host immune system, which leads to rapid change, as the VSR must constantly out-evolve the host's defenses. In contrast, P2 is more conserved with 51–62% sequence identity among all of the members of the genus Polerovirus. The CPs of other poleroviruses have 40–60% sequence identity to the RMV MTFE87 CP, while the overlapping P4s have significantly less similarity (Table 2). This suggests that base changes in the ORF 3/4 sequence that alter the meaning of ORF 4 codons are more often tolerated than those that alter the amino acid sequence of the CP. Overall, the lack of high similarity of any luteovirid ORF with those of RMV MTFE87 emphasizes its uniqueness as a virus.

CIS-acting signals

Cis acting sequences required for polerovirus translation, subgenomic mRNA (sgRNA) transcription and RNA synthesis have been identified in PLRV and others. The genomes of all poleroviruses begins with the sequence ACAAAA. Similarly, where known, the 5′ end of the sgRNA of the poleroviruses begins with ACAAAA (Miller and Mayo, 1991). This leads us to predict that the sgRNA required for translation of BYDV-RMV ORFs 3, 4, and 5 begins at position 3309ACAAAA3314. This is 202 nt upstream of the CP ORF that starts at position 3516, giving an sgRNA leader sequence similar to the 212 nt leader of PLRV sgRNA1.

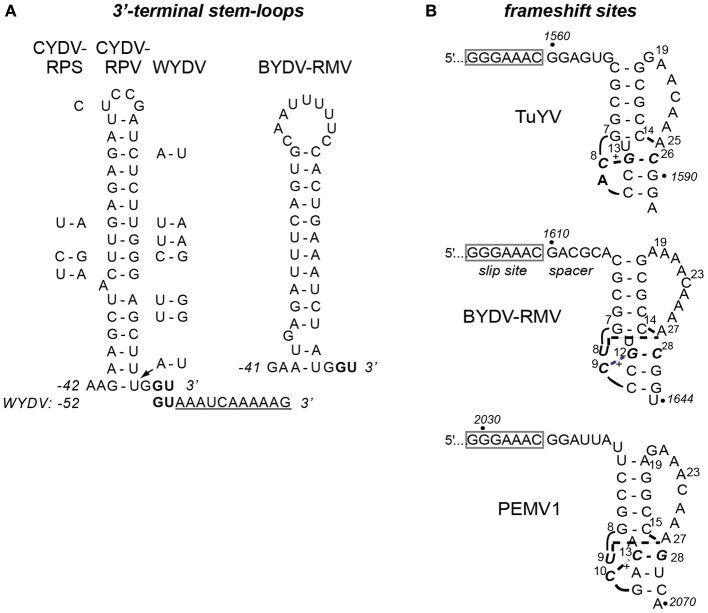

A 40 nt stem-loop containing a bulged adenosine, ending 3 nt upstream of the 3′ end of the genome, was shown to be required for initiation of CYDV-RPV negative strand synthesis (Osman et al., 2006). This stem-loop is conserved in CYDV-RPS and WYDV, which are very closely related to CYDV-RPV (Figure 6A). In contrast, RMV MTFE87 has a different predicted stem-loop that is 39 nt long with a much larger loop and a bulged guanosine (Figure 5A). Like all other poleroviruses (except WYDV), the two bases at the 3′ end of the RMV MTFE87 genome are GU (bold, Figure 6A). Thus, the first two bases incorporated by the RdRp initiating synthesis of either strand are AC. Surprisingly, WYDV is reported to contain an 11 nt A-rich tract at the 3′ end downstream of the GU (Figure 6A). We speculate that this is either sequence added during 3′ RACE, or sequence of a defective WYDV genome. The distinct 3′ stem-loop of RMV MTFE87 further supports that above phylogenetic comparisons about the un-CYDV-like nature of BYDV-RMV.

Figure 6.

Predicted secondary structures in BYDV-RMV RNA. (A) Stem-loop at the 3′ terminus of CYDV-RPV genome as determined by Osman et al. (2006), flanked by base differences in CYDV-RPS (left) and WYDV (right) which show covariations in base pairing that maintain secondary structure. Conserved 3′ terminal bases, GU are shown in bold. Eleven extra bases at the 3′ end of the WYDV genome, not present in any other polerovirus, are shown below the CYDV-RPV sequence in underlined text. The proposed secondary structure of the 3′ end of the BYDV-RMV genome was predicted using Mfold (Zuker, 2003). Base numbering (negative) is from the 3′ end of the genomes. (B) Predicted (BYDV-RMV) and known (PEMV1 and TuYV) (Su et al., 1999; Nixon et al., 2002; Miller and Giedroc, 2010) tertiary structures of pseudoknots downstream of the frameshift sites (boxed). Italics indicate base numbers in the genome. Other numbering is the position in the fragment used for nmr (except BYDV-RMV where the number allows comparison with the other structures). Short curved lines indicate phosphodiester backbone as necessary for two-dimensional rendering. Bold, dashed lines indicate non-Watson-Crick interactions between bases. +indicated protonated cytidine that participates in base triples. Due to the recent change of the name of the BWYV isolate used in previous structural studies (Domier, 2012) it is now indicated by the new name, TuYV.

We also identified probable translational control sequences. In all Luteoviridae, ORF2 encoding the active site of the RdRp is translated via ribosomal frameshifting at a shifty heptanucleotide, fitting the motif XXXYYYZ (where X is any base, Y is A or U, and Z is any base except G), in the region of ORF1–ORF2 overlap. Seven nt downstream of this site, the polero- and enamovirus genomes fold into a small, compact pseudoknot that pauses the ribosome to facilitate frameshifting (Su et al., 1999; Nixon et al., 2002; Miller and Giedroc, 2010). Indeed, in the region of ORF1–ORF2 overlap in the RMV MTFE87 genome, we found the shifty heptanucleotide 1603GGGAAAC1609, followed by a predicted pseudoknot that spans bases 1616–1643 (Figure 6B). This pseudoknot closely resembles those of other poleroviruses and the enamovirus, the structures of which have been determined at high resolution by NMR (Su et al., 1999; Nixon et al., 2002). The Watson–Crick helices of the RMV MTFE87 pseudoknot, CGCGG:CCGCG and CCG:CGG are identical to those in TuYV, but the helical junction region includes a predicted C+-AU triplet that resembles the junction in the PEMV1 pseudoknot (Figure 6B).

The sequence required for translational readthrough of the CP ORF stop codon also resembles those of other Luteoviridae. Readthrough of the BYDV-PAV CP ORF stop codon was shown to require at least five repeats of the sequence CCXXXX, where X is any base, beginning about 16–22 nt downstream of the stop codon (Brown et al., 1996). Indeed, in the RMV MTFE87 genome, a tract of 12 CCXXXX repeats starting at nt 4131 begins 16 nt downstream of the CP ORF stop codon (Figure 1). This codes for an amino acid sequence of alternating proline residues, which is a likely spacer to permit separate folding of the CP and RTD protein domains. In summary, BYDV-RMV has all the known cis-acting signals of a polerovirus to control translation of viral proteins.

Proposed name change of BYDV-RMV to maize yellow dwarf virus-RMV

The RMV MTFE87 sequence shows that the viruses once called BYDV are even more diverse than previously thought. The sequence also shows clearly that BYDV-RMV is not in genus Luteovirus, to which all other sequenced viruses currently called BYDV are assigned. Nor is it a type of CYDV or WYDV. Therefore, we propose to change the name of BYDV-RMV to Maize yellow dwarf virus-RMV (MYDV-RMV) (Miller et al., 2013). This name (1) acknowledges that the virus is clearly a new species (2) is consistent with observations that BYDV-RMV often infects maize (Brown et al., 1984; Beuve et al., 1999; Itnyre et al., 1999a,b), (3) retains the RMV notation for the predominant vector, R. maidis (although S. graminum and R. padi can also be efficient vectors, particularly in the western United States), and (4) retains the YDV descriptor long used for luteovirids that infect cereals.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This journal paper of the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station, Ames, Iowa, Project No. IOW06664, was supported by National Science Foundation grant number DEB–0843140 and USDA National Research Initiative grant no. 2004-35600-14227. The authors thank Dai Nguyen for administrative support, Dawn Smith for assistance with the aphid transmission experiments, and Véronique Ziegler-Graff for helpful comments on this manuscript.

References

- Banks P., Davidson J., Bariana H., Larkin P. (1995). Effects of barley yellow dwarf virus on the yield of winter wheat. Aust. J. Agri. Res. 46, 935–946 10.1071/AR9950935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberger N., Tsai C.-H., Lie M., Havecker E., Baulcombe D. C. (2007). The Polerovirus silencing suppressor P0 targets ARGONAUTE proteins for degradation. Curr. Biol. 17, 1609–1614 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett R., Miller W. A. (2007). Rapid full-length cloning of non-polyadenylated RNA virus genomes, in Current Protocols in Microbiology, eds Coico R., Kowalik T., Quarles J., Stevenson B., Taylor R. (New York, NY; John Wiley and Sons, Inc; ), 16F.3.1–16F.3.18. [Google Scholar]

- Beuve M., Naïbo B., Foulgocq L., Lapierre H. (1999). Irrigated hybrid maize crop yield losses due to barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV luteovirus. Crop. Sci. 39, 1830–1834 10.2135/cropsci1999.3961830x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolamiol D., Pazhouhandeh M., Marrocco K., Geschik P., Ziegler-Graff V. (2007). The polerovirus F Box protein P0 targets ARGONAUTE1 to suppress RNA silencing. Curr. Biol. 17, 1615–1621 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault V., Van Den Heuvel J. F., Verbeek M., Ziegler-Graff V., Reutenauer A., Herrbach E., et al. (1995). Aphid transmission of beet western yellows luteovirus requires the minor capsid read-through protein P74. EMBO J. 14, 650–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. M., Dinesh-Kumar S. P., Miller W. A. (1996). Local and distant sequences are required for efficient readthrough of the barley yellow dwarf virus PAV coat protein gene stop codon. J. Virol. 70, 5884–5892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. K., Wyatt S. D., Hazelwood D. (1984). Irrigated corn as a source of barley yellow dwarf virus and vector in eastern Washington. Phytopathology 74, 46–49 10.1094/Phyto-74-46 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brumfield S. K. Z., Carroll T. W., Gray S. M. (1992). Biological and serological characterization of three Montana RMV-like isolates of barley yellow dwarf virus. Plant Dis. 76, 33–39 10.1094/PD-76-0033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chain F., Riault G., Trottet M., Jacquot E. (2005). Analysis of accumulation patterns of barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV (BYDV-PAV) in two resistant wheat lines. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 113, 343–355 10.1007/s10658-005-7966-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chay C. A., Gunasinge U. B., Dinesh-Kumar S. P., Miller W. A., Gray S. M. (1996a). Aphid transmission and systemic plant infection determinants of barley yellow dwarf luteovirus-PAV are contained in the coat protein readthrough domain and 17-kDa protein, respectively. Virology 219, 57–65 10.1006/viro.1996.0222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chay C. A., Smith D. M., Vaughn R., Gray S. M. (1996b). Diversity among isolates within the PAV serotype of barley yellow dwarf virus. Phytopathology 86, 370–377 10.1094/Phyto-86-37018944888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clamp M., Cuff J., Searle S. M., Barton G. J. (2004). The jalview java alignment editor. Bioinformatics 20, 426–427 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien B., Baumberger N., Schepetilnikov M., Viotti C., De Cillia J., Ziegler-Graff V., et al. (2012). Degradation of the antiviral component ARGONAUTE1 by the autophagy pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15942–15946 10.1073/pnas.1209487109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domier L. L. (2012). Family - Luteoviridae, in Virus Taxonomy, 9th Edn, eds Andrew M. Q. K., Elliot L., Michael J. A., Carstens E. B. (San Diego, CA: Elsevier; ), 1045–1053 [Google Scholar]

- Domier L. L., Lukasheva L. I., D'arcy C. J. (1997). Coat protein sequence of RMV-like strains of barley yellow dwarf virus separate them from other luteoviruses. Intervirology 37, 2–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Muadhidi M. A., Makkouk K. M., Kumari S. G., Myasser J., Murad S. S., Mustafa R. R., et al. (2001). Survey for legume and cereal viruses in Iraq. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 40, 224–233 [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B., Green P. (1998). Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. error probabilities. Genome Res. 8, 186–194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusaro A. F., Correa R. L., Nakasugi K., Jackson C., Kawchuk L., Vasline M. F. S., et al. (2012). The Enamovirus P0 protein is a silencing suppressor which inhibits local and systemic RNA silencing through AGO1 degradation. Virology 426, 178–187 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E., Gattiker A., Hoogland C., Ivanyi I., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2003). ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 10.1093/nar/gkg563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geske S. M., French R., Robertson N. L., Carroll T. W. (1996). Purification and coat protein gene sequence of a Montana RMV-like isolate of barley yellow dwarf virus. Arch. Virol. 141, 541–556 10.1007/BF01718316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildow F. E. (1993). Evidence for receptor-mediated endocytosis regulating luteovirus acquisition by aphids. Phytopathology 83, 270–277 10.1094/Phyto-83-270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D., Abajin C., Green P. (1998). Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8, 195–202 10.1101/gr.8.3.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J., Lister R. M., Foster J. E. (1983). Purification, identity and some properties of an isolate of barley yellow dwarf virus from Indiana. J. Gen. Virol. 65, 667–676 10.1099/0022-1317-64-3-667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes J. R., Jones R. A. C. (2005). Incidence and distribution of Barley yellow dwarf virus and cereal yellow dwarf virus in over-summering grasses in a Mediterranean-type environment. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 56, 257–270 10.1071/AR04259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hesler L. S., Riedell W. E., Langham M. A., Osborne S. L. (2005). Insect infestations, incidence of viral plant diseases, and yield of winter wheat in relation to planting date in the northern great plains. J. Econ. Entomol. 98, 2020–2027 10.1603/0022-0493-98.6.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itnyre R. L. C., D'arcy C. J., Pataky J. K., Pedersen W. L. (1999a). Symptomatology of barley yellow dwarf virus-RMV infection in sweet corn. Plant Dis. 83, 781–781 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.8.781C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itnyre R. L. C., D'arcy C. J., Pedersen W. L., Sweets L. E. (1999b). Reaction of sweet corn to inoculation with barley yellow dwarf virus RMV-IL. Plant Dis. 83, 566–568 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.6.566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarošová J., Chrpová J., Šíp V., Kundu J. K. (2013). A comparative study of the Barley yellow dwarf virus species PAV and PAS: distribution, accumulation and host resistance. Plant Pathol. 62, 436–443 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2012.02644.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Wang X., Chang S., Zhou G. (2004). The complete nucleotide sequence and its organization of the genome of barley yellow dwarf virus-GAV. Sci. China C Life Sci. 47, 175–182 10.1360/03yc0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy T. F., Connery J. (2012). Control of barley yellow dwarf virus in minimum-till and conventional-till autumn-sown cereals by insecticide seed and foliar spray treatments. J. Agric. Sci. 150, 249–262 10.1017/S0021859611000505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowska-Makulska A., Guilley H., Szyndel M. S., Beuve M., Lemaire O., Herrbach E., et al. (2010). P0 proteins of European beet-infecting poleroviruses display variable RNA silencing suppression activity. J. Gen. Virol. 91, 1082–1091 10.1099/vir.0.016360-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A. B., Drugeon G. L., Hulanicka D., Haenni A.-L. (1993). Structural requirements for efficient translational frameshifting in the synthesis of the putative viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of potato leafroll virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2165–2171 10.1093/nar/21.9.2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S. G., Muharram I., Makkouk K. M., Al-Ansi A., El-Pasha R., Al-Motwkel W. A., et al. (2006). Identification of viral diseases affecting barley and bread wheat crops in yemen. Aust. Plant Pathol. 35, 563–568 10.1071/AP06061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L., Palukaitis P., Gray S. M. (2002). Host-dependent requirement for the Potato leafroll virus 17-kDa protein in virus movement. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 15, 1086–1094 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.10.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Ryan M. D., Lamb J. W. (2000). Potato leafroll virus protein P1 contains a serine proteinase domain. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 1857–1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R. M., Ranieri R. (1995). Distribution and economic importance of barley yellow dwarf, in Barley Yellow Dwarf: 40 Years of Progress, eds D'Arcy C. J., Burnett P. A. (St. Paul, MN: APS Press; ), 29–53 [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Wang X., Liu Y., Xie J., Gray S. M., Zhou G., et al. (2007). A Chinese isolate of barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV represents a third distinct species within the PAV serotype. Arch. Virol. 152, 1365–1373 10.1007/s00705-007-0947-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucio-Zavaleta E., Smith D., Gray S. (2001). Variation in transmission efficiency among barley yellow dwarf virus-RMV isolates and clones of the normally inefficient aphid vector, Rhopalosiphum padi. Phytopathology 91, 792–796 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.8.792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangwende T., Wang M.-L., Borth W., Hu J., Moore P. H., Mirkov T. E., et al. (2009). The P0 gene of Sugarcane yellow leaf virus encodes an RNA silencing suppressor with unique activities. Virology 384, 38–50 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirdy S. J., Jones R. A. C., Nutter F. W. (2002). Quantification of yield losses caused by barley yellow dwarf virus in wheat and oats. Plant Dis. 86, 769–773 10.1094/PDIS.2002.86.7.769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. S., Mayo M. A. (1991). The location of the 5' end of the potato leafroll luteovirus subgenomic coat protein mRNA. J. Gen. Virol. 72, 2633–2638 10.1099/0022-1317-72-11-2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. A., Giedroc D. (2010). Ribosomal frameshifting in decoding plant viral RNAs, in Recoding: Expansion of Decoding Rules Enriches Gene Expression, eds. Atkins J. F., Gesteland R. F. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 193–220 10.1007/978-0-387-89382-2_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. A., Krueger E. N., Gray S. M. (2013). ICTV taxonomic proposal 2013.016a,bP: In the family Luteoviridae, create species Maize yellow dwarf virus-RMV in the genus Polerovirus and remove the unassigned species Barley yellow dwarf virus-RMV. Available online at: http://talk.ictvonline.org/files/proposals/taxonomy_proposals_plant1/m/plant01/4600.aspx

- Miller W. A., Liu S., Beckett R. (2002). Barley yellow dwarf virus: Luteoviridae or Tombusviridae? Mol. Plant Pathol. 3, 177–183 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2002.00112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak A., Berry B., Tassetto M., Kunitomi M., Acevedo A., Deng C., et al. (2010). Cricket paralysis virus antagonizes Argonaute 2 to modulate antiviral defense in drosophila. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 547–554 10.1038/nsmb.1810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon P. L., Cornish P. V., Suram S. V., Giedroc D. P. (2002). Thermodynamic analysis of conserved loop-stem interactions in P1-P2 frameshifting RNA pseudoknots from plant Luteoviridae. Biochemistry 41, 10665–10674 10.1021/bi025843c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman T. A. M., Coutts R. H. A., Buck K. W. (2006). In vitro synthesis of minus-strand RNA by an isolated Cereal yellow dwarf Virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase requires VPg and a stem-loop structure at the 3' end of the virus RNA. J. Virol. 80, 10743–10751 10.1128/JVI.01050-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazhouhandeh M., Dieterle M., Marrocco K., Lechner E., Berry B., Brault V., et al. (2006). F-box-like domain in the polerovirus protein P0 is required for silencing suppressor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1994–1999 10.1073/pnas.0510784103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry K. L., Kolb F. L., Sammons B., Lawson C., Cisar G., Ohm H. (2000). Yield effects of barley yellow dwarf virus in soft red winter wheat. Phytopathology 90, 1043–1048 10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.9.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter K. A., Gildow F., Palukaitis P., Gray S. M. (2009). The C terminus of the polerovirus p5 readthrough domain limits virus infection to the phloem. J. Virol. 83, 5419–5429 10.1128/JVI.02312-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S., Dunoyer P., Heim F., Richards K. E., Jonard G., Ziegler-Graff V. (2002). P0 of beet western yellows virus is a suppressor of posttranscriptional gene silencing. J. Virol. 76, 6815–6824 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6815-6824.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Power A. G., Borer E. T., Hosseini P., Mitchell C. E., Seabloom E. W. (2011). The community ecology of barley/cereal yellow dwarf viruses in Western US grasslands. Virus Res. 159, 95–100 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power A. G., Gray S. M. (1995). Aphid transmission of barley yellow dwarf viruses: interactions between viruses, vectors, and host plants, in Barley Yellow Dwarf: 40 Years of Progress, eds D'Arcy C. J., Burnett P. A. (St. Paul, MN: APS Press; ), 259–291 [Google Scholar]

- Prüfer D., Kawchuk L., Monecke M., Nowok S., Fischer R., Rohde W. (1999). Immunological analysis of potato leafroll luteovirus (PLRV) P1 expression identifies a 25 kDa RNA-binding protein derived via P1 processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 421–425 10.1093/nar/27.2.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prüfer D., Kawchuk L. M., Rohde W. (2006). Polerovirus ORF0 genes induce a host-specific response resembling viral infection. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 28, 302–309 10.1080/07060660609507299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prüfer D., Tacke E., Schmitz J., Kull B., Kaufmann A., Rhode W. (1992). Ribosomal frameshifting in plants: a novel signal directs the -1 frameshift in the synthesis of the putative viral replicase of potato leafroll luteovirus. EMBO J. 11, 1111–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochow W. F. (1969). Biological properties of four isolates of barley yellow dwarf virus. Phytopathology 59, 1580–1589 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochow W. F., Carmichael L. E. (1979). Specificity among barley yellow dwarf viruses in enzyme immunosorbent assays. Virology 95, 415–420 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90496-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochow W. F., Muller I. (1971). A fifth variant of barley yellow dwarf virus in New York. Plant Dis. Rep. 55, 874–877 [Google Scholar]

- Rochow W. F., Norman A. G. (1961). The barley yellow dwarf virus disease of small grains. Adv. Agron. 13, 217–248 10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60960-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Royer T. A., Giles K. L., Nyamanzi T., Hunger R. M., Krenzer E. G., Elliot N. C., et al. (2005). Economic evaluation of the effects of planting date and application rate of imidacloprid for management of cereal aphids and barley yellow dwarf in winter wheat. J. Econ. Entomol. 98, 95–102 10.1603/0022-0493-98.1.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J., Stussi-Garaud C., Tacke E., Prufer D., Rohde W., Rohfritsch O. (1997). In situ localization of the putative movement protein (pr17) from potato leafroll luteovirus (PLRV) in infected and transgenic potato plants. Virology 235, 311–322 10.1006/viro.1997.8679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui N. N., Ilyas M., Mansoor S., Azhar A., Saeed M. (2012). Cloning and phylogenetic analysis of coat protein of barley yellow dwarf virus isolates from different regions of pakistan. J. Phytopathol. 160, 13–18 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2011.01853.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su L., Chen L., Egli M., Berger J. M., Rich A. (1999). Minor groove RNA triplex in the crystal structure of a ribosomal frameshifting viral pseudoknot. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 285–292 10.1038/6722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007). MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Heuvel J. F., Bruyere A., Hogenhout S. A., Ziegler-Graff V., Brault V., Verbeek M., et al. (1997). The N-terminal region of the luteovirus readthrough domain determines virus binding to buchnera GroEL and is essential for virus persistence in the aphid. J. Virol. 71, 7258–7265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Wilk F., Houterman P., Molthoff J., Hans F., Dekker B., Van Den Heuvel J., et al. (1997a). Expression of the potato leafroll virus ORF0 induces viral-disease-like symptoms in transgenic potato plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 10, 153–159 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.2.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Wilk F., Verbeek M., Dullemans A. M., Van Den Heuvel J. F. J. M. (1997b). The genome-linked protein of potato leafroll virus is located downstream of the putative protease domain of the ORF1 product. Virology 234, 300–303 10.1006/viro.1997.8654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webby G. N., Lister R. M. (1992). Purification of the NY-RMV and NY-SGV isolates of barley yellow dwarf virus and the production and properties of their antibodies. Plant Dis. 76, 1125–1132 10.1094/PD-76-1125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wobus C. E., Skaf J. S., Schultz M. H., De Zoeten G. A. (1998). Sequencing, genomic localization and initial characterization of the VPg of pea enation mosaic enamovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 79, 2023–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z., Wang Y., Du Z., Li J., Zhao R. Y., Wang D. (2008). A potential nuclear envelope-targeting domain and an arginine-rich RNA binding element identified in the putative movement protein of the GAV strain of Barley yellow dwarf virus. Funct. Plant Biol. 35, 40–50 10.1071/FP07114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Cheng Z., Xu L., Wu M., Waterhouse P., Zhou G., et al. (2009). The complete nucleotide sequence of the barley yellow dwarf GPV isolate from China shows that it is a new member of the genus polerovirus. Arch. Virol. 154, 1125–1128 10.1007/s00705-009-0415-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. (2003). Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415 10.1093/nar/gkg595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]