Abstract

Impaired local cellular immunity contributes to the pathogenesis of persistent high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) infection and related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), but the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Recently, the programmed death 1/programmed death 1 ligand (PD-1/PD-L1; CD279/CD274) pathway was demonstrated to play a critical role in attenuating T-cell responses and promoting T-cell tolerance during chronic viral infections. In this study, we examined the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 on cervical T cells and dendritic cells (DCs), respectively, from 40 women who were HR-HPV-negative (−) or HR-HPV-positive (+) with CIN grades 0, I and II–III. We also measured interferon-γ, interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-10 in cervical exudates. The most common HPV type was HPV 16, followed by HPV 18, 33, 51 and 58. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression on cervical T cells and DCs, respectively, was associated with HR-HPV positivity and increased in parallel with increasing CIN grade. The opposite pattern was observed for CD80 and CD86 expression on DCs, which decreased in HR-HPV(+) patients in parallel with increasing CIN grade. Similarly, reduced levels of the T helper type 1 cytokines interferon-γ and IL-12 and increased levels of the T helper type 2 cytokine IL-10 in cervical exudates correlated with HR-HPV positivity and CIN grade. Our results suggest that up-regulation of the inhibitory PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may negatively regulate cervical cell-mediated immunity to HPV and contribute to the progression of HR-HPV-related CIN. These results may aid in the development of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway-based strategies for immunotherapy of HR-HPV-related CIN.

Keywords: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, cytokines, human papillomavirus, programmed death-1, programmed death-1 ligand

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the first cancer recognized by the World Health Organization to be 100% attributable to infection. Persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) is the main aetiological factor in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancer.1 Infection of the cervix by HPV is relatively common in young sexually active women. In ∼ 70–90% of HPV-positive (+) women, the infection is spontaneously cleared by the immune response, but persistent HPV infection has been suggested to be a causative factor in the development of CIN.2 However, only a small proportion of HPV-infected women eventually develop cervical cancer, and there is a long latency period between primary infection and the appearance of cervical dysplasia, suggesting that additional factors are involved in disease progression.3,4

Human papillomavirus does not disseminate systemically and causes only localized mucosal infections that are not associated with significant inflammation, suggesting that HPV-specific cell-mediated immunity (CMI) plays an important role in the persistence or clearance of cervical HPV infection.5,6 Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells for naive T cells, and accordingly, are critical for the initiation of the HPV-specific immune response and destruction of virus-infected cells. Presentation of viral antigens by DCs activates naive T cells to proliferate and differentiate into effector cells, which produce cytokines that amplify the antiviral response or specifically recognize and eliminate virus-infected cells.7–9 Although HPV-encoded antigens can be detected in the cervix, the HPV-infected cells avoid eradication by the host immune system. Several studies have shown that local CMI is suppressed during HPV infection, especially in persistent infections with HR-HPV.10–12 However, the underlying molecular mechanisms by which this occurs remain largely undefined.

Several novel immunoregulatory molecules have been discovered, including two members of the B7-CD28 family: programmed death-1 (PD-1, CD279) and its ligand PD-L1 (CD274). PD-1 is expressed on lymphocytes, particularly T cells, and is an inducible negative regulator of T-cell activity. PD-L1 is one of two PD-1 ligands and is expressed on both antigen-presenting cells and T cells. Ligation of PD-1 by PD-L1 induces a co-inhibitory signal in activated T cells and promotes T-cell apoptosis, anergy and functional exhaustion.13,14 Related studies have shown that this pathway plays a critical role in attenuating T-cell activation and promoting T-cell tolerance during infection with human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and other pathogens capable of establishing chronic infections.15,16 Although considerable evidence supports the involvement of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in the negative regulation of many adaptive responses, it is not yet known whether it influences the human anti-HPV response or contributes to HPV immune evasion.

To evaluate the roles of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in the immunopathogenesis of HR-HPV-related CIN, we examined the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 on cervical T cells and DCs, respectively, from HR-HPV(−) women or HR-HPV(+) women with different CIN grades. We also measured levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-10 in the cervical exudates. We found a direct correlation between the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 and HPV positivity and CIN grade, supporting the hypothesis that this pathway impairs cervical immunity in HR-HPV-related CIN.

Materials and methods

Study participants and procedures

The study participants were recruited from first-time attendees at the First Hospital Affiliated to Chinese PLA (People's Liberation Army) General Hospital. The women had liquid-based cytological smear results of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. The women were examined by colposcopy at the second visit, and HPV sampling and biopsy specimens were obtained. Histological results were defined as no intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN 0), mild dysplasia (CIN I) or moderate to severe dysplasia (CIN II–III) based on a consensus review by two experienced pathologists. Exclusion criteria were as follows: other infectious disease, immunological disorder, postmenopausal state, pregnancy, anti-inflammatory treatment, sexually transmitted or neoplastic disease, immunocompromised state and use of steroids or immunosuppressive agents. The final cohort of 40 study participants was classified into four groups of 10: (i) HR-HPV(−) CIN 0; (ii) HR-HPV(+) CIN 0; (iii) HR-HPV(+) CIN I; (iv) HR-HPV(+) CIN II–III. All participants gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital.

Specimen collection

Three samples were collected from each woman. Two samples were collected with digene Cervical Samplers (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany); one for detection of infection and HPV typing and the second to obtain cervical cells for flow cytometry and cervical exudates for cytokine ELISAs. Abnormal cervical areas detected under colposcopic guidance were sampled using a punch biopsy forceps. Samples were not collected from women if they were menstruating on the day of enrolment.

Polymerase chain reaction for HPV DNA typing

One of the cervical cytobrushes was placed in 1·0 ml digene specimen transport medium (Qiagen) and analysed for the presence of HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 66, as described in detail elsewhere.17 Briefly, DNA was extracted from the cervical samples using a DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was analysed by qualitative PCR using type-specific and gene-specific primers. β-Globin was also amplified to verify that the samples contained a sufficient quality and quantity of DNA for HPV detection. Each experiment was performed with water as a negative PCR control.

Cytological and histological evaluation of the cervical tissue

A liquid-based Papanicolaou test slide was prepared using the liquid-based cervical cells following routine procedures. Cytological diagnoses were obtained using the Bethesda System (2002). For counting of immune cells, 10 slides per group (one from each patient) were selected and the total cell number in five visual fields per slide was counted under × 400 magnification. The average cell number per field was used for statistical comparisons. Biopsy specimens for histological examination were fixed in 10% formalin and then placed in fresh formalin for an additional 24 hr. Paraffin-embedded tissue was prepared by routine histological techniques and 5-μm-thick sections were stained with haematoxylin & eosin for analysis by light microscopy. The consensus diagnosis of two pathologists was considered the final diagnosis.

Flow cytometry

The second cytobrush was placed directly in a 15-ml tube containing 5 ml ice-cold RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum. The medium was supplemented with 5 mm dl-dithiothreitol (Sigma, St Louis, MO), then incubated at 37° for 15 min to reduce the mucous content. Cervical cells were then isolated by vigorously rotating the brush against the sides of the tube. The cell suspension was washed twice and the density was adjusted to 2 × 105 cells/ml. Non-specific antibody binding was blocked by pre-incubating the cells with an Fc-receptor blocking antibody (anti-CD16/CD32) for 10 min. The cells were then labelled by the addition of a mixture of monoclonal antibodies for the detection of DCs [CD11c-phycoerythrin (clone 3.9), CD80-FITC (clone 2D10), CD86-Peridinin chlorophyll protein (clone IT2.2) and PD-L1-allophycocyanin (clone 29E.2A3)] or T cells [CD3-phycoerythrin (clone HIT3a) and PD-1-FITC (clone EH12.2H7)] and incubated for 30 min at 4° in the dark. The appropriate IgG isotypes were used as controls. All antibodies were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Data were acquired on a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur (Mountain View, CA) and processed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). For analysis, the cells were first gated by forward and side scatter to include mononuclear cells and exclude cervical epithelial cells. Approximately 0·5 × 105 to 1·0 × 105 mononuclear cells were gated per sample. The gated cells were then analysed for the expression of combinations of fluorophores. To ensure that cervical samples were not contaminated by blood-derived leucocytes,18 we excluded samples containing more than 1% B lymphocytes in the gated mononuclear cells. If necessary, a fresh cervical sample was collected.

Cytokine ELISAs

The cervical exudate samples for quantification of cytokines were kept frozen at −80° until use. Standardized sandwich ELISA kits for human IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-12 were obtained from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA) and used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The detecting antibody in the IL-12 immunoassay recognized the bioactive heterodimeric (p40 + p35) cytokine as well as subunit p40 monomers or homodimers. Absorbances were measured on an automatic plate reader. The minimum detectable concentrations were 3 pg/ml for IFN-γ, 1 pg/ml for IL-10 and 1·5 pg/ml for IL-12.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Group differences in patient characteristics were analysed by the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. In the experiments involving histology or flow cytometry, the figures shown are representative of at least three experiments performed on different days on the tissue sections or mononuclear cells. All statistical assessments were two-sided, and P-values < 0·05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Description of the study groups

The baseline characteristics of the study groups are summarized in Table 1. The 40 study participants were aged between 26 and 38 years (mean 31·9 years) and there were no significant age differences among the groups. In the 30 HR-HPV(+) women, HPV 16 was the most common type (26·7%, 8/30) followed by HPV 18 (23·3%, 7/30), 33 (20·0%, 6/30) and 51 (16·7%, 5/30). A single HPV type was detected in 19 (63·3%) of the HR-HPV(+) women, and two or more HPV types were found in the same sample from 11 (36·7%) women. No HR-HPV infection was detected in the HR-HPV(−) CIN 0 group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and pathological features of the study groups

| CIN 0 HR-HPV(−) n = 10 | CIN 0 HR-HPV(+) n = 10 | CIN I HR-HPV(+) n = 10 | CIN II–III HR-HPV(+) n = 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age range (years) | 28–36 | 26–37 | 27–34 | 29–38 |

| Mean age (years)1 | 31·5 (3·24) | 30·8 (3·52) | 31·1 (2·51) | 34·2 (3·68) |

| Subjects infected with HPV types (n) | ||||

| 16 | – | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 18 | – | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 33 | – | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 51 | – | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 58 | – | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 52 | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Other | – | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Multiple infections | – | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| Pathological features | ||||

| Koilocytosis (n) | – | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Gland involvement (n) | – | – | 1 | 4 |

| Number of immune cells2 | 15·8 ± 4·5 | 18·6 ± 4·8* | 19·1 ± 4·3* | 18·3 ± 5·6 |

CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; high-risk human papillomavirus-negative, HR-HPV(–); high-risk human papillomavirus-positive, HR-HPV(+).

Mean (standard deviation).

Average cells/field under × 400 magnification.

P < 0·05 compared with the HR-HPV(−) group.

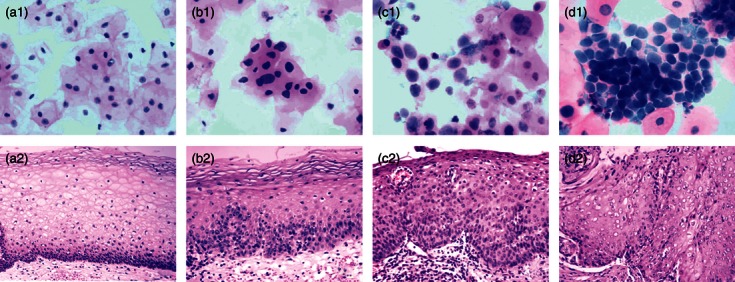

Cytological and histological diagnosis and CIN grading

Figure 1 shows representative examples of the typical cytological and histological changes in the cervix for the four groups. There were no morphological changes in cervical smears and biopsy sections in either the HR-HPV(−) and HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 groups (Fig. 1a1,a2). Slides from the CIN I group showed slight dysplasia limited to the basal third of the epithelial layer. The nuclei of the dysplastic cells were enlarged, irregular and hyperchromatic. Disorganization of the basal layer was an important characteristic (Fig. 1b1, b2). In the CIN II–III group, moderate or severe dysplasia could be seen and abnormal cells occupied at least two-thirds of the epithelial layer. The normal cell polarity was lost, and abundant mitotic figures were present at all levels. There was also a markedly increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of the individual cells (Fig. 1c1,c2,d1,d2). Extension into the endocervical glands was common, but no invasive squamous cell carcinomas were diagnosed. Samples from the HR-HPV(+) groups frequently showed koilocytosis of the epidermal prickle cell layer and increased numbers of infiltrating immune cells (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cytological and histological changes in the cervix. No cytological or histological alterations were observed in samples from the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 0 groups (a1 and a2). Slides from the CIN I group showed slight dysplasia limited to the basal third of the epithelial layer, and the nuclei of the dysplastic cells were enlarged, irregular and hyperchromatic (b1 and b2). Slides from the CIN II–III group showed markedly increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios in the dysplastic cells, and these atypical cells occupied at least two-thirds of the epithelial layer (CIN II: c1 and c2; CIN III: d1 and d2). a1–d1, Papanicolaou staining of cervical smears, original magnification × 800. a2–d2, haematoxylin & eosin staining of tissue sections, original magnification × 400.

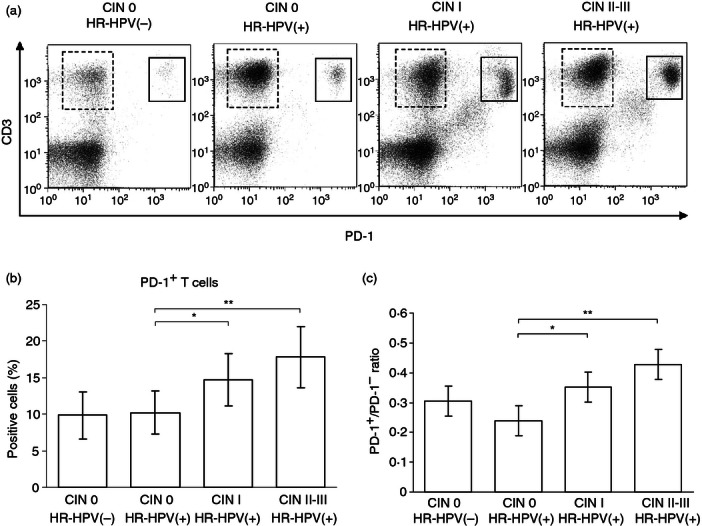

Increased PD-1 expression on cervical T cells in HR-HPV-related CIN

To explore whether PD-1 and PD-L1 might be involved in the interactions between T cells and DCs in HR-HPV-related CIN, we first examined the frequency of PD-1+ T cells in cervical samples by flow cytometry. Figure 2(a) shows representative dot plots indicating the presence of CD3+ PD-1− and CD3+ PD-1+ T-cell subsets. As shown in Fig. 2(b,c), the percentage of PD-1+ T cells and the ratio of PD-1+ to PD-1− cells was significantly increased in the cervical cell population from patients in the CIN I and CIN II–III groups compared with the HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 group (P < 0·05 and P < 0·01, respectively). This finding suggests a possible association between the increased PD-1 expression on T cells, persistent HR-HPV infection and the development of CIN.

Figure 2.

Increased programmed death 1 (PD-1) expression on T cells in high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) -related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Cervical cells were labelled with a mixture of monoclonal antibodies against CD3 and PD-1 and the percentage of positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. Representative dot plots showing CD3+ PD-1− (dashed lines) and CD3+ PD-1+ (solid lines) T-cell subsets (a), percentage of PD-1+ T cells (b) and ratio of PD-1+ to PD-1– cells (c). Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

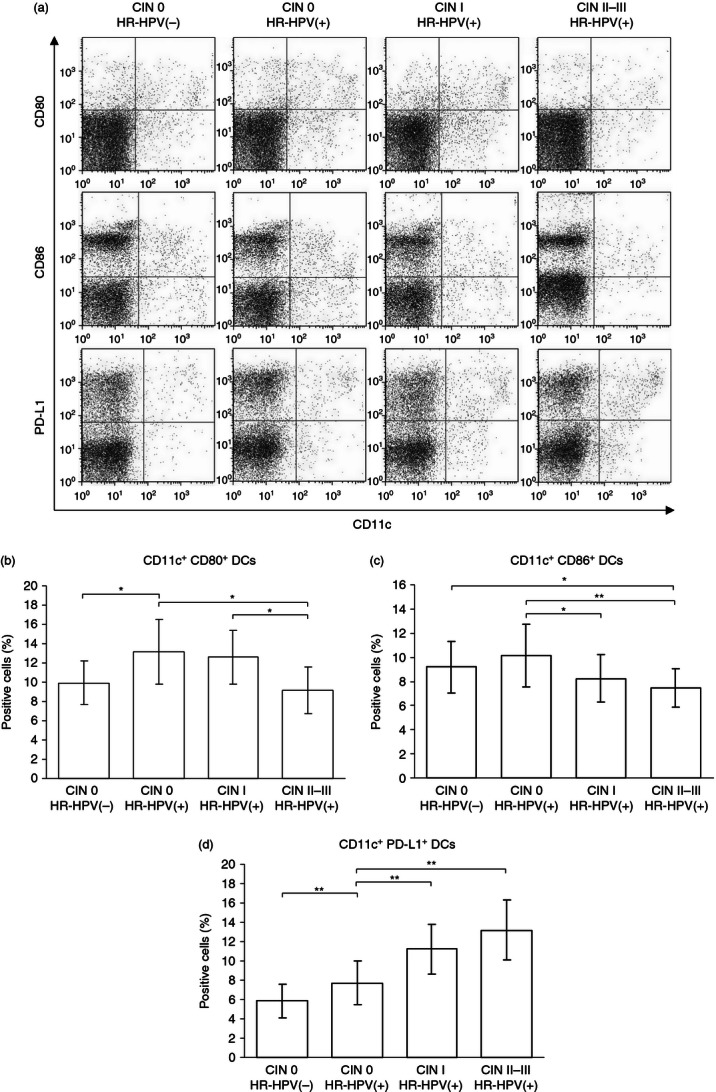

Reduced CD80 and CD86 expression and increased PD-L1 expression on cervical DCs in HR-HPV-related CIN

We next examined the frequency of DCs expressing the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 and the co-inhibitory molecule PD-L1 in the cervical cells. Representative dot plots showing the distinct CD11c+ CD80+, CD11c+ CD86+ and CD11c+ PD-L1+ subsets of DCs are shown in Fig 3(a). As shown in Fig 3(b), a significantly higher percentage of CD11c+ CD80+ DCs was found in samples from HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 patients than from HR-HPV(−) CIN 0 patients (P < 0·05). However, the percentage of CD11c+ CD80+ DCs was significantly lower in the CIN II–III group than in the CIN I group or the HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 group (all P < 0·05). As shown in Fig. 3(c), the percentage of CD11c+ CD86+ DCs in the HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 group was slightly higher than in the HR-HPV(−) CIN 0 group, although the difference was not statistically significant. The percentage of CD11c+ CD86+ DCs in the HR-HPV(+) groups declined significantly in parallel with increasing CIN grade (CIN I versus CIN 0: P < 0·05; CIN II–III versus CIN 0: P < 0·01) (Fig. 3c). In contrast to the findings with the CD80+ and CD86+ DC subsets, we found that the CD11c+ PD-L1+ DC population in cervical cells was higher in the HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 group than in the HR-HPV(−) CIN 0 group, and also increased in parallel with the increasing CIN grade (Fig. 3d). We found significant differences in the frequency of CD11c+ PD-L1+ DCs in the HR-HPV(−) versus HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 group (P < 0·01) and the HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 versus CIN I or CIN II–III groups (all P < 0·01). Hence, the observed combination of reduced CD80 and CD86 expression and increased PD-L1 expression on cervical DCs from HR-HPV-infected women suggests that HR-HPV infection and the progression of HR-HPV-related CIN may be associated with changes in DC function.

Figure 3.

CD80, CD86 and programmed death 1 ligand (PD-L1) expression on dendritic cells (DCs) in high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) -related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Cervical cells were labelled with monoclonal antibodies against CD11c plus CD80, CD86 or PD-L1 and the percentage of positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. Representative dot plots (a). Percentage of DC subsets expressing CD11c+ CD80+ (b), CD11c+ CD86+ (c) and CD11c+ PD-L1+ (d). Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

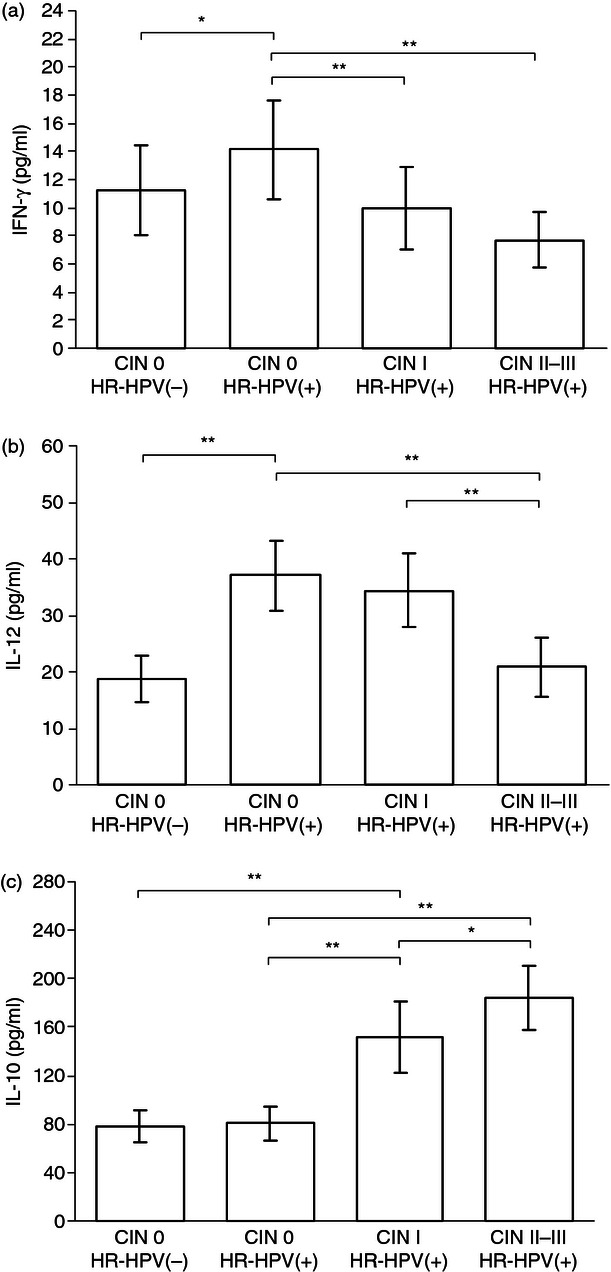

Alterations in cervical exudate cytokine levels

Measurement of cytokine production is an important factor in evaluating HPV-specific CMI, which is thought to influence the persistence or clearance of cervical HPV infection and the development of CIN. Here, we analysed the levels of T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 cytokines in cervical exudates to characterize the local immune response in HR-HPV-related CIN. As shown in Fig 4(a,b), the cervical exudates from the HR-HPV(+) CIN 0 group contained significantly higher levels of the Th1-type cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12 than those from the HR-HPV(−) CIN 0 group (P < 0·05 and P < 0·01, respectively). However, the levels IFN-γ and IL-12 decreased significantly with increasing CIN grade. In the HR-HPV(+) groups, the levels of IFN-γ were significantly different between the CIN 0 and CIN I groups (P < 0·01) and between the CIN 0 and CIN II–III groups (P < 0·01). Levels of IL-12 were significantly different between the CIN 0 and CIN II–III groups (P < 0·01) and between the CIN I and CIN II–III groups (P < 0·01). As shown in Fig. 4(c), the expression pattern of the Th2 cytokine IL-10 was quite different. Levels of IL-10 were significantly increased in the CIN I and CIN II–III groups compared with the CIN 0 group (all P < 0·01). In addition, the maximum levels of IL-10 were observed in the CIN II–III group, which in turn were significantly higher than the levels in the CIN I group (P < 0·05).

Figure 4.

Cytokine levels in cervical exudates. Levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (a), interleukin-12 (IL-12) (b) and IL-10 (c). Compared with the high-risk human papillomavirus-positive [HR-HPV(+)] cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 0 group, samples from the CIN I and CIN II–III groups contained reduced levels of the T helper type 1 cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12 and increased levels of the T helper type 2 cytokine IL-10. Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

Discussion

Persistent infection with HR-HPV is necessary for the development of CIN and cervical cancer. Cell-mediated immunity is thought to be an important mechanism in protection against the virus and elimination of virus-infected cells, and is therefore among the factors that influence the likelihood of a cervical HPV infection becoming persistent.11,12 Because HPV causes only localized mucosal infections and does not spread systemically, examination of the cervical microenvironment is important to fully understand the host response to HPV and related cervical disease.19 Recent studies have demonstrated that integrin β7+ intraepithelial T cells are significantly increased in patients with spontaneously regressing CIN lesions, regardless of HPV genotype.20 In addition, T cells isolated from dysplastic mucosa are skewed toward a central memory phenotype, and dysregulated expression of vascular adhesion molecules plays a role in immune evasion very early in the course of HPV disease.21 The present study is the first to examine the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 on cervical cells in HR-HPV(−) women and HR-HPV(+) women with different grades of CIN, and the first to investigate Th1 and Th2 cytokine levels in the cervical microenvironment.

The most prevalent HR-HPV type associated with CIN in our study participants was HPV 16, followed by HPV 18, 33, 51 and 58. Infection with more than one HR-HPV type and histological endocervical gland involvement were more common in patients with high-grade CIN. We found that expression of the co-inhibitory molecules PD-1 and PD-L1 on cervical T cells and DCs, respectively, was significantly increased in HR-HPV(+) patients and correlated positively with the CIN grade. In parallel, DC expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 decreased as the CIN grade progressed from 0 to II–III. In addition, reduced levels of the Th1 cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12 and an increased level of the Th2-type cytokine IL-10 were associated with HR-HPV positivity and increasing CIN grade. Hence, activation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway appeared to correlate with dysfunctional CMI to HR-HPV infection and altered production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines. These data suggest that the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway participates in the immunopathogenesis of HR-HPV-related CIN.

Dendritic cells are the most important antigen-presenting cells in the cervical microenvironment, and the capacity of DCs to deliver co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory signals plays a significant role in determining whether the responding T cells undergo activation or tolerance.22 The involvement of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in chronic viral infection-associated T-cell exhaustion was first demonstrated in a murine lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus model.23 Infection of mice with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus led to the functional exhaustion of virus-specific CD8+ T cells and the continuous elevated expression of PD-1. Functional recovery of the exhausted T cells was also shown to be possible with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, which restored proliferation, cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity and decreased the viral load.23 The inhibitory effect of PD-1 was also demonstrated in patients with self-limiting HBV infection, where elevated PD-1 during the acute phase of infection correlated with reduced T-cell function.24 These results suggest that the interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1 plays a critical role in the dysfunction of T cells during chronic viral infections and serves as a checkpoint in determining the fate of T-cell activation or tolerance during T-cell priming. The latest related study has reported that the proportions of regulatory T cells and/or PD-1+ cells in cervical CD4+ T cells were significantly lower in CIN regressors than non-regressors.25 Furthermore, another study recently demonstrated that prophylactic vaccination against HPV combined with soluble PD-1 to block the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction resulted in an enhanced HPV-specific cytotoxic T-cell response and a potent anti-tumour effect in a mouse model of HPV infection.26 There is now substantial evidence that the prevalence of cervical PD-1+ cells may play an important role in HPV-related neoplastic immuno-evasion. The present study showed that PD-1/PD-L1 molecules were up-regulated on cervical DCs and T cells from HR-HPV(+) patients, indicating that the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may act as an important negative regulator in the local cervical CMI response to HR-HPV infection and participate in the immunopathogenesis of persistent HPV infection and related CIN progression.

As mentioned, the balance between co-inhibitory and co-stimulatory molecules on DCs may regulate their interactions with T cells.27–29 A recent study demonstrated that the co-stimulatory capacity of DCs was impaired and inversely correlated with PD-L1 expression and the PD-L1/CD86 ratio in HCV-infected patients, indicating that the effect of PD-L1 overwhelmed the effect of the co-stimulatory molecules and down-regulated T-cell activation.30 The present data suggest that the decreased expression of CD80 and CD86 on DCs in HR-HPV(+) patients could inhibit T-cell activation, whereas the elevated levels of PD-1 on T cells and the increased expression of PD-L1 on DCs may induce T-cell tolerance and may be responsible for the depressed CMI response to the persistent HPV infection. Enhanced PD-1/PD-L1 interactions may also inhibit the antigen-presenting function of DCs, which in turn would suppress T-cell activation, prevent clearance of the HR-HPV infection and contribute to HPV immune escape, resulting in CIN progression. However, PD-1 expression on cervical T cells was not significantly different between the two CIN 0 groups in our study, indicating that the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway might not be involved in limiting T-cell activation at the acute stage of virus infection.

Cervical mucosal expression of immunomodulatory cytokines is believed to influence persistent HPV infection and the development of CIN.31–33 A related study has demonstrated that a shift from a Th1 to a Th2 cytokine response was observed when healthy controls or women with low-grade CIN were compared with women with high-grade CIN or cervical cancer.34 In the present study, we examined cervical expression of three key cytokines involved in CMI. Interferon-γ is the signature cytokine of Th1 responses, IL-12 is a key cytokine involved in inducing and maintaining such responses, and IL-10 is one of the predominant anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive Th2 cytokines. The significant increase of IFN-γ and IL-12 in our HR-HPV(+) patients with CIN 0 suggested that the initial viral infection activated the local cytokine network and induced cervical CMI. The lack of a significant difference in IL-10 levels between the two CIN 0 groups is not surprising, because ∼ 70–90% of infected women clear HPV infection spontaneously, indicating that local immunosuppression caused by immunosuppressive cytokines was not still present at the stage of CIN 0.2,35 However, the finding that IFN-γ and IL-12 levels decreased and IL-10 levels increased in the HR-HPV(+) women in parallel with the increasing CIN grade suggests that a shift from a Th1 to a Th2 cytokine response occurs during persistent HR-HPV infection and CIN progression.

Ligation of PD-1 by PD-L1 not only inhibits T-cell proliferation, but also influences cytokine production by activated T cells or DCs.36–38 As a pro-inflammatory molecule, IFN-γ is known to be a major regulator of PD-L1 expression for a wide range of cell types. A study of cancer-associated PD-L1 up-regulation found that IFN-γ induced the expression of the transcription factor IFN regulatory factor 1, which binds to regulatory sites in the PD-L1 gene and is largely responsible for the observed increase in PD-L1.39 Binding of PD-L1 to the PD-1 receptor negatively regulates T cells, causing decreased proliferation and production of effector cytokines, such as IL-2 and IFN-γ.38–40 The relationship between CIN grade and increased expression of PD-L1 on DCs, together with the decreased production of IFN-γ in our HR-HPV(+) patients, suggests that the pro-inflammatory activity might be modulated through a negative feedback loop. In this scenario, activated Th1 cells producing high levels of IFN-γ are forced to reduce their cytokine levels via IFN-γ-induced PD-1 and PD-L1 expression. Our data suggest that the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may modulate T-cell proliferation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, resulting in the suppression of cellular responses that clear the persistent HR-HPV infection.

One limitation of our study is that we only assessed the non-specific cytokine response, and have no evidence that this response was directly correlated with HPV infection or some other factors. Future investigations will focus on analysing the HPV-specific cytokine response in enriched cervical T cells isolated from patients with CIN, which would help elucidate the mechanism of impaired CMI in HR-HPV-related CIN. In addition, our results suggest that the expression of the inhibitory molecule PD-L1 countered the effects of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on cervical DCs and correlated with down-regulation of Th1-type cytokines such as IFN-γ. However, it will be necessary to explore whether increased PD-L1 expression on different DC subsets or on other antigen-presenting cells is associated with the imbalance in cytokine production. This hypothesis will also need to be addressed in future investigations, especially using PD-1/PD-L1 blockage between DCs and T cells.

In summary, in this study we have demonstrated a correlation between up-regulated expression PD-1 on T cells and PD-L1 on DCs and increasing CIN grades in HR-HPV infection. The up-regulated PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may contribute, at least in part, to the suppression of the CMI response in HR-HPV-related CIN progression. Furthermore, up-regulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway was associated with altered production of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, which also contributed to localized immunosuppression. Therefore, blocking PD-1/PD-L1 interactions may represent a potential therapeutic option for HR-HPV-infected patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (Project No. 81000848) of China and the Capital Health Research and Development of Special of China (Project No. 2011-5002-01). We thank the patients who participated in this study.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Insinga RP, Perez G, Wheeler CM, et al. Incident cervical HPV infections in young women: transition probabilities for CIN and infection clearance. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:287–96. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mougin C, Mo L, Dalstein V. Natural history of papillomavirus infections. Rev Prat. 2006;56:1883–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheu BC, Chang WC, Lin HH, Chow SN, Huang SC. Immune concept of human papillomaviruses and related antigens in local cancer milieu of human cervical neoplasia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:103–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebner CM, Laimins LA. Human papillomaviruses: basic mechanisms of pathogenesis and oncogenicity. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:83–97. doi: 10.1002/rmv.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Passmore JA, Milner M, Denny L, et al. Comparison of cervical and blood T-cell responses to human papillomavirus-16 in women with human papillomavirus-associated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Immunology. 2006;119:507–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng S, Trimble C, Wu L, Pardoll D, Roden R, Hung CF, Wu TC. HLA-DQB1*02-restricted HPV-16 E7 peptide-specific CD4+ T-cell immune responses correlate with regression of HPV-16-associated high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2479–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen XZ, Mao XH, Zhu KJ, Jin N, Ye J, Cen JP, Zhou Q, Cheng H. Toll like receptor agonists augment HPV 11 E7-specific T cell responses by modulating monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0976-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudolf MP, Fausch SC, Da Silva DM, Kast WM. Human dendritic cells are activated by chimeric human papillomavirus type-16 virus-like particles and induce epitope-specific human T cell responses in vitro. J Immunol. 2001;166:5917–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.5917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiriva-Internati M, Liu Y, Salati E, et al. Efficient generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against cervical cancer cells by adeno-associated virus/human papillomavirus type 16 E7 antigen gene transduction into dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:30–8. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200201)32:1<30::AID-IMMU30>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott M, Nakagawa M, Moscicki AB. Cell-mediated immune response to human papillomavirus infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:209–20. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.2.209-220.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzmán-Olea E, Bermúdez-Morales VH, Peralta-Zaragoza O, Torres-Poveda K, Madrid-Marina V. Molecular mechanism and potential targets for blocking HPV-induced lesion development. J Oncol. 2012;2012:278312. doi: 10.1155/2012/278312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen HH, Broker TR, Chow LT, et al. Immune responses to human papillomavirus in genital tract of women with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:452–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;27:111–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3015–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmeyer KA, Jeon H, Zang X. The PD-1/PD-L1 (B7-H1) pathway in chronic infection-induced cytotoxic T lymphocyte exhaustion. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:451694. doi: 10.1155/2011/451694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe T, Bertoletti A, Tanoto TA. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and T-cell exhaustion in chronic hepatitis virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:453–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Syrjänen S, Naud P, Sarian L, et al. Up-regulation of 14-3-3sigma (Stratifin) is associated with High-Grade CIN and high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) at baseline but does not predict outcomes of HR-HPV infections or incident CIN in the LAMS study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:232–40. doi: 10.1309/AJCP49DOITYDCTQJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prakash M, Patterson S, Kapembwa MS. Evaluation of the cervical cytobrush sampling technique for the preparation of CD45+ mononuclear cells from the human cervix. J Immunol Methods. 2001;258:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00464-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castle PE, Giuliano AR. Genital tract infections, cervical inflammation, and antioxidant nutrients – assessing their roles as human papillomavirus cofactors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;31:29–34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kojima S, Kawana K, Fujii T, et al. Characterization of gut-derived intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) residing in human papillomavirus (HPV)-infected intraepithelial neoplastic lesions. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:435–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trimble CL, Clark RA, Thoburn C, et al. Human papillomavirus 16-associated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in humans excludes CD8 T cells from dysplastic epithelium. J Immunol. 2010;185:7107–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Jin B, Zhang JY, et al. Dynamic decrease in PD-1 expression correlates with HBV-specific memory CD8 T-cell development in acute self-limited hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojima S, Kawana K, Tomio K, et al. The prevalence of cervical regulatory T cells in HPV-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) correlates inversely with spontaneous regression of CIN. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69:134–41. doi: 10.1111/aji.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song MY, Park SH, Nam HJ, Choi DH, Sung YC. Enhancement of vaccine-induced primary and memory CD8+ T-cell responses by soluble PD-1. J Immunother. 2011;34:297–306. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318210ed0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okazaki T, Honjo T. The PD-1–PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wölfle SJ, Strebovsky J, Bartz H, Sähr A, Arnold C, Kaiser C, Dalpke AH, Heeg K. PD-L1 expression on tolerogenic APCs is controlled by STAT-3. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:413–24. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peña-Cruz V, McDonough SM, Diaz-Griffero F, Crum CP, Carrasco RD, Freeman GJ. PD-1 on immature and PD-1 ligands on migratory human Langerhans cells regulate antigen-presenting cell activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2222–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen T, Chen X, Chen Y, Xu Q, Lu F, Liu S. Increased PD-L1 expression and PD-L1/CD86 ratio on dendritic cells were associated with impaired dendritic cells function in HCV infection. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1152–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bais AG, Beckmann I, Ewing PC, Eijkemans MJ, Meijer CJ, Snijders PJ, Helmerhorst TJ. Cytokine release in HR-HPV(+) women without and with cervical dysplasia (CIN II and III) or carcinoma, compared with HR-HPV(–) controls. Mediators Inflamm. 2007;2007:24147. doi: 10.1155/2007/24147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott ME, Ma Y, Kuzmich L, Moscicki AB. Diminished IFN-γ and IL-10 and elevated Foxp3 mRNA expression in the cervix are associated with CIN 2 or 3. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1379–83. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bermudez-Morales VH, Gutierrez LX, Alcocer-Gonzalez JM, Burguete A, Madrid-Marina V. Correlation between IL-10 gene expression and HPV infection in cervical cancer: a mechanism for immune response escape. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:1037–43. doi: 10.1080/07357900802112693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bais AG, Beckmann I, Lindemans J, Ewing PC, Meijer CJ, Snijders PJ, Helmerhorst TJ. A shift to a peripheral Th2-type cytokine pattern during the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer becomes manifest in CIN III lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1096–100. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.025072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mocellin S, Marincola FM, Young HA. Interleukin-10 and the immune response against cancer: a counterpoint. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1043–51. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0705358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1027–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Said EA, Dupuy FP, Trautmann L, et al. Programmed death-1-induced interleukin-10 production by monocytes impairs CD4+ T cell activation during HIV infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:452–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blank C, Gajewski TF, Mackensen A. Interaction of PD-L1 on tumor cells with PD-1 on tumor-specific T cells as a mechanism of immune evasion: implications for tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:307–14. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0593-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SJ, Jang BC, Lee SW, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-1 is prerequisite to the constitutive expression and IFN-γ-induced upregulation of B7-H1 (CD274) FEBS Lett. 2006;580:755–62. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter L, Fouser LA, Jussif J, et al. PD-1: PD-L inhibitory pathway affects both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and is overcome by IL-2. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:634–43. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<634::AID-IMMU634>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]