Abstract

Aminoglycosides, such as amikacin and kanamycin, are powerful broad-spectrum antibiotics used for the treatment of many bacterial infections. The widely used aminoglycosides have the unfortunate side effects of targeting sensory hair cells of the inner ear, so that treatment often results in permanent hair cell loss. The aim of the study was to evaluate the influence of incubation time and drug concentration on viability of melanocytes cultured in the presence of amikacin or kanamycin. The normal human melanocytes HEMa-LP and the different concentrations of amikacin (0.075, 0.75 and 7.5 mmol/l) and kanamycin (0.06, 0.6 and 6.0 mmol/l), were used. The estimations were performed after 24, 48 and 72 h. The observed decrease in melanocytes viability may be an explanation for the mechanisms involved in aminoglycosides toxicity on pigmented tissues during high-dose and/or long-term therapy.

Keywords: Amikacin, cell viability, kanamycin, melanocytes

Amikacin and kanamycin are recommended for the treatment of Gram-negative and some Gram-positive microorganisms infections, especially in severe and bacteremic infections. However, an excessive dosage of the aminoglycosides may cause the side effects of ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity. In addition, a long-term usage of these antibiotics may result in high and persistent tissue residues due to their tissue affinity.[1,2]

Many drugs are extensively accumulated in melanin-containing tissues.[3] Antibiotics, psychotropic, antirheumatic, anaesthetic and antitumour agents are reported to possess high affinity to melanin biopolymers.[3–9] However, a physiological function of this binding is not fully understood.

It has been earlier demonstrated that amikacin[8] and kanamycin[10] form stable complexes with model synthetic melanin in vitro. Drug-melanin interactions are still not fully characterised, partly because melanins are not well-defined chemical entities but rather mixtures of more or less similar polymers apparently made up of different structural units linked by nonhydrolysable bonds.

Melanin is synthesised in the melanosomes in melanocytes and produced by a process that involves the transformation of tyrosine into 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) by the enzyme tyrosinase and the subsequent transformation of L-DOPA into melanin.[11] The quantity of melanin in various organs has been shown to vary with age, e.g., age-related reduction of melanin in the hair, epidermis, retinal pigment epithelial cells, and certain areas of the central nervous system.[12] There are two basic types of melanins: Eumelanin and pheomelanin, in mammalian neural crest-derived melanocytes. Each of them has been suggested to possess different chemical and biological properties. In the ear eumelanin may principally scavenge toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) and play an otoprotective role, whereas pheomelanin may produce toxic ROS and exert toxic effects on the cochlea.[12,13]

The aim of the presented work was to examine the impact of different concentrations of amikacin and kanamycin as well as of incubation time on the viability of normal human melanocytes.

Amikacin sulphate was obtained in the form of solution - Biodacyna (250 mg/2 ml) from Bioton, Poland. Kanamycin A (sulphate salt) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc., USA. Penicilin was obtained from Polfa Tarchomin, Poland. Growth medium M-254, gentamicin, amphotericin B and human melanocyte growth supplement-2 (HMGS-2) were obtained from Cascade Biologics, UK. Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 was purchased from Roche GmbH, Germany. The remaining chemicals were produced by POCH S.A., Poland.

The normal human epidermal melanocytes (HEMa-LP, Cascade Biologics, UK) were grown according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The cells were cultured in M-254 medium supplemented with HMGS-2, penicillin (100 U/ml), gentamicin (10 μg/ml) and amphotericin B (0.25 μg/ml) at 37° in 5% CO2. All experiments were performed using cells in passages 5-7.

The viability of melanocytes was evaluated by WST-1 (4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-l, 3-benzene disulfonate) colorimetric assay. WST-1 is a water-soluble tetrazolium salt, the rate of WST-1 cleavage by mitochondrial dehydrogenases correlates with the number of viable cells. Briefly, 5×l03 cells per well were placed in a 96-well microplate in a supplemented M-254 growth medium and incubated at 37° and 5% CO2 for 48 h. Then the medium was removed and cells were treated with aminoglycoside antibiotics solutions in the concentration range from 0.075 mmol/l to 7.5 mmol/l for amikacin and from 0.06 mmol/l to 6.0 mmol/l for kanamycin. The estimations were performed after 24, 48 and 72 h. Ten microliters of WST-1 were added to 100 μl of culture medium in each well 3 h before the end of incubation time. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 440 nm with a reference wavelength of 650 nm, against the controls (the same cells but not treated with a drug) using a microplate reader UVM 340 (Biogenet, Piaseczno, Poland). The controls were normalised to 100% for each assay and treatments were expressed as percentage of the controls.

In all experiments, mean values of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate±standard deviations (SD) were calculated. The results were analysed statistically with the ANOVA test using GraphPad Prism 5.04 Software GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, USA. In all cases, the statistical significance was found at least at P<0.05.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics still find frequent use in today’s hospitalised patient population owing to their spectrum of activity and unique mode of bacterial killing. Although, highly effective, reservations concerning potential oto- and nephrotoxicity have often limited the use of these agents.[1,2]

Animal studies concerning ototoxicity have shown that the degree of cochlear damage is more related to the total daily dose of the aminoglycoside rather than to the frequency with which the drug is administered. Saturation of cochlear cells may play a role in determining ototoxicity.[14]

Melanin has been described in the cochlear labyrinth and it has been suggested that its function is to protect the cochlea from various types of trauma, including the effects of ototoxic drugs, such as aminoglycoside antibiotics.[3] The intermediate cells in the stria vascularis of the inner ear are melanocytes capable of synthesizing melanin and are important for the maintenance of endocochlear potential as well as for the normal function of marginal cells and the stria capillary system.[12,13]

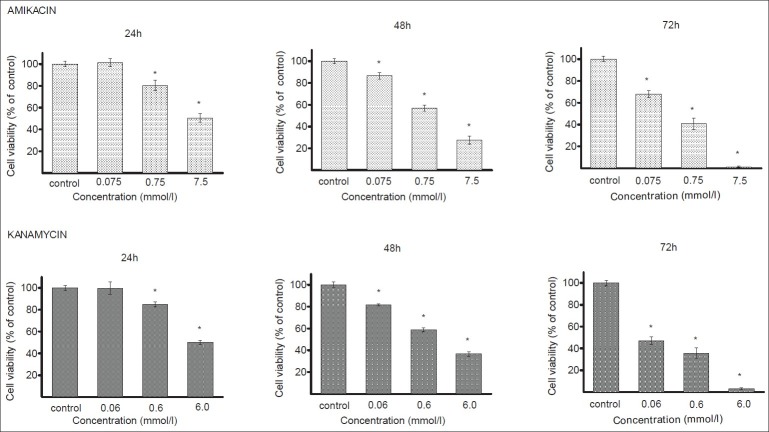

In this study, human melanocytes were cultured for 24, 48 or 72 h in the presence of different amikacin or kanamycin concentrations. The rates of melanocytes viability after treatment with the tested antibiotics are presented in fig. 1. A growth inhibition of melanocytes exposed to amikacin at concentrations of 0.75 mmol/l and 7.5 mmol/l was observed at each time interval. The strongest antiproliferating activity was observed for 7.5 mmol/l after 72 h where the viability of cells decreased to 1% as compared with the control. There was no growth inhibition at the amikacin concentration of 0.075 mmol/l after 24 h. Kanamycin in the concentrations of 0.6 mmol/l and 6.0 mmol/l decreased melanocytes viability after 24, 48 and 72 h. The greatest effect was observed at 6 mmol/l after 72 h, reaching an inhibition by about 97% with respect to the control. The growth of melanocytes was not reduced by kanamycin at the concentration of 0.06 mmol/l after 24 h.

Fig. 1.

Viability of melanocytes cultured in the presence of amikacin and kanamycin

Viability of melanocytes cultured in the presence of amikacin (0.075-7.5 mmol/l) and kanamycin (0.06-6.0 mmol/l) for 24-72 h. Each bar represents the mean±SD. *P<0.05 compared with control.

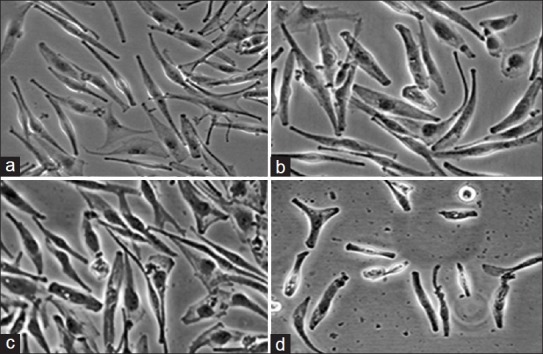

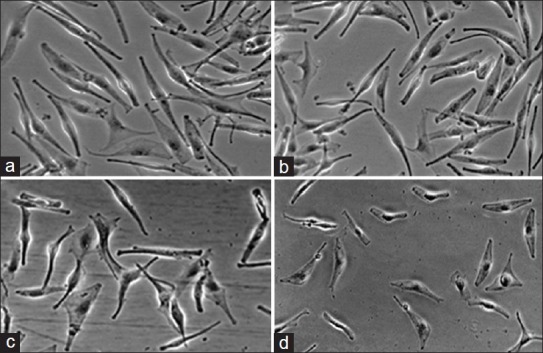

Estimation of HEMa-LP cells by inverted microscopy following their incubation with amikacin (fig. 2) or kanamycin (fig. 3) has demonstrated the toxicity similar to the pattern of cell viability measured with the WST-1 assay. Figs. 2a and 3a, represent control cells with normal dendritic morphology. No changes were observed after 24 h exposure to the lowest amikacin (0.075 mmol/l) or kanamycin (0.06 mmol/l) concentrations (figs. 2b and 3b). However, the HEMa-LP melanocytes morphology was changed after exposure to increased antibiotics concentrations (fig. 2c and d for amikacin; fig. 3c and d for kanamycin). These changes were characterised by a decrease in number and length of dendrites.

Fig. 2.

Morphological changes of normal human melanocytes HEMa- LP exposed to different amikacin concentrations for 24 h.

Cell monolayer treated with the lowest concentration of amikacin (b - 0.075 mmol/l) is similar to the control culture (a - free of antibiotic). The higher concentrations of amikacin induced detectable changes in cell morphology (c - 0.75 mmol/l, d - 7.5 mmol/l). Cells were observed under an inverted microscope at ×200 magnification.

Fig. 3.

Morphological changes of normal human melanocytes HEMa- LP exposed to different kanamycin concentrations for 24 h.

Cell monolayer treated with the lowest concentration of kanamycin (b - 0.06 mmol/l) is similar to the control culture (a - free of antibiotic). The higher concentrations of kanamycin induced detectable changes in cell morphology (c - 0.6 mmol/l, d - 6.0 mmol/l). Cells were observed under an inverted microscope at ×200 magnification.

Damage of melanocytes in stria vascularis may lead to loss of these cells via trauma, infection, or perhaps noise. Ototoxic agents, such as aminoglycoside antibiotics, may damage intermediate cells, resulting in hearing loss.[14]

It has been demonstrated that the aminoglycosides ototoxicity may be correlated to pigmentation. In an animal model, albino guinea pigs were found to be more susceptible to these antibiotics toxicity than the pigmented strain.[15] The pathophysiological significance of this finding is unclear, but it may be suggested that melanin may protect the cochlea by accumulating or binding aminoglycosides. Loss of melanin and its relation to hearing loss have been sparsely investigated. It is known that aminoglycoside antibiotics have the capacity to form complexes with melanin[8,10,16,17] and subsequently may affect the activity of melanocytes.[12] Melanin has a potent antioxidant capacity, and intermediate cells that lack this pigment have obviously less ability to reduce the generation of ROS. The regulation of these processes in human melanocytes is complex and there are indications that aminoglycosides may alter the melanin function in cells.[18–20]

In conclusion, the obtained results are consistent with the possibility that melanin may binds with aminoglycosides and decrease the severity of their ototoxicity in pigmented inner ear. The ability of melanin to bind low doses of amikacin or kanamycin may prevent cells against the antibiotic-induced toxic effects. However, amikacin and kanamycin in higher concentrations reduced the viability of normal human melanocytes, what may explain the aminoglycosides toxicity on pigmented tissues during high-dose and/or long-term therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland (Grant No. KNW-1-003/P/2/0).

Footnotes

Wrześniok, et al.: Impact of Aminoglycosides on Melanocytes Viability

REFERENCES

- 1.Durante-Mangoni E, Grammatikos A, Utili R, Falagas ME. Do we still need the aminoglycosides? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buszman E, Wrzesniok D, Grzegorczyk A, Matusiñski B, Molêda K. Aminoglycoside antibiotics: Contemporary hypotheses on side effects. Sci Rev Pharm. 2007;4:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsson BS. Interaction between chemicals and melanin. Pigment Cell Res. 1993;6:127–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1993.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beberok A, Buszman E, Zdybel M, Pilawa B, Wrze, Wrzesniok D. EPR examination of free radical properties of DOPA-melanin complexes with ciprofloxacin, lomefloxacin, norfloxacin and sparfloxacin? Chem Phys Lett. 2010;497:115–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beberok A, Buszman E, Wrzesniok D, Otreba M, Trzcionka J. Interaction between ciprofloxacin and melanin: The effect on proliferation and melanization in melanocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;669:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buszman E, Beberok A, Rózañska R, Orzechowska A. Interaction of chlorpromazine, fluphenazine and trifluoperazine with ocular and synthetic melanin in vitro. Pharmazie. 2008;63:372–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buszman E, Wrzesniok D, Surazynski A, Palka J, Moleda K. Effect of melanin on netilmicin-induced inhibition of collagen biosynthesis in human skin fibroblasts. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:8155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buszman E, Wrzesniok D, Trzcionka J. Interaction of neomycin, tobramycin and amikacin with melanin in vitro in relation to aminoglycosides-induced ototoxicity. Pharmazie. 2007;62:210–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surazyñski A, Pa³ka J, Wrzesniok D, Buszman E, Kaczmarczyk P. Melanin potentiates daunorubicin-induced inhibition of collagen biosynthesis in human skin fibroblasts. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;419:139–45. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrzesniok D, Buszman E, Karna E, Palka J. Melanin potentiates kanamycin-induced inhibition of collagen biosynthesis in human skin fibroblasts. Pharmazie. 2005;60:439–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otrêba M, Rok J, Buszman E, Wrzesniok D. Regulation of melanogenesis: The role of cAMP and MITF. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2012;66:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plonka PM, Passeron T, Brenner M, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, Thomas A, et al. What are melanocytes really doing all day long.? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:799–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scherer D, Kumar R. Genetics of pigmentation in skin cancer: A review. Mutat Res. 2010;705:141–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araki S, Mizuta K, Takeshita T, Morita H, Mineta H, Hoshino T. Degeneration of the stria vascularis during development in melanocyte-deficient mutant rats (Ws/Ws rats) Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:309–15. doi: 10.1007/s00405-002-0480-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conlee JW, Bennett ML, Creel DJ. Differential effects of gentamicin on the distribution of cochlear function in albino and pigmented guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol. 1995;115:367–74. doi: 10.3109/00016489509139331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wrzesniok D, Buszman E, Karna E, Nawrat P, Palka J. Melanin potentiates gentamicin-induced inhibition of collagen biosynthesis in human skin fibroblasts. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;446:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buszman E, Pilawa B, Zdybel M, Wrzesniok D, Grzegorczyk A, Wilczok T. EPR examination of Zn2+ and Cu 2+ effect on free radicals in DOPA-melanin-netilmicin complexes. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;403:22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gratacap B, Charachon R, Stoebner P. Results of an ultrastructural study comparing stria vascularis with organ of Corti in guinea pigs treated with kanamycin. Acta Otolaryngol. 1985;99:339–42. doi: 10.3109/00016488509108920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forge A, Wright A, Davies SJ. Analysis of structural changes in the stria vascularis following chronic gentamicin treatment. Hear Res. 1987;31:253–65. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conlee JW, Gill SS, McCandless PT, Creel DJ. Differential susceptibility to gentamicin ototoxicity between albino and pigmented guinea pigs. Hear Res. 1989;41:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]