Abstract

Background

Falls and resulting fractures are a leading cause of morbidity/mortality in the elderly. With the withdrawal of certain selective COX2 inhibitors in 2004, narcotic analgesics have increasingly been recommended as first-line therapy in guidelines for the treatment of chronic pain.

Objectives

To evaluate the changes in types of medications prescribed for pain pre- and post-withdrawal of certain selective COX2 inhibitors in 2004 and to determine if there was an association with fall events among elderly patients with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis.

Design

A nested case-control design using electronic medical records compiled between 2001–2009.

Setting

Electronic medical records for care provided in an integrated health system in rural Pennsylvania over a nine year period (2001–9), the midpoint of which rofecoxib (Vioxx) and valdecoxib (Bextra) were pulled from the market.

Participants

13,354 patients, aged 65–89, with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis (OA).

Measurements

The incidence of falls/fractures was examined in relation to analgesics prescribed: narcotics, COX2 inhibitors, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The comparison sample of no fall patients was matched 3:1 to fall patients according to age, gender and comorbidity.

Results

Narcotic analgesic prescriptions were associated with a significantly increased risk of falls/fractures. The odds ratio of experiencing a fall/fracture was higher in patients prescribed narcotic analgesics than those prescribed a COX2 inhibitor (3.3, 2.5–4.3) or NSAID (4.1, 3.7–4.5).

Conclusion

The increased use of narcotic analgesics is associated with an increased risk of falls/fractures in elderly patients with osteoarthritis, an observation that suggests the current guidelines for the treatment of pain, which include first-line prescription of narcotics, should be re-evaluated.

Keywords: aging, osteoarthritis, pain, health care

INTRODUCTION

Falls are a common occurrence in the elderly, with 30% of people age 65 and older and 50% of those aged 80 and older falling at least once each year.1 The consequences of a fall can be devastating to the aged with the result being severe injuries, loss of function and independence. Among patients older than 65 years with trauma related to a fall, 32% experienced a severe injury, and the fall was seven times more likely to be the cause of death than for those younger than 65 years.2 Half of all older adults hospitalized for hip fracture never regain their former level of function.3 Falls also have a significant psychological impact, as fear of falling can lead to reduction in physical function and social interactions.4 In 2000, the total direct cost of all fall injuries for people 65 and older exceeded $19 billion.5 This has led to a national mandate to lower the incidence of falls in elderly individuals.6

French et al reported that for non-hospitalized patients taking medications that affect the sensorium, such as narcotic analgesics, significantly more fall-coded health care encounters were documented.7 While studies have looked at medications and falls in inpatient or nursing home settings,8,9 only a few recent studies have examined the influence of prescription analgesics on falls in elderly populations outside of the hospital or nursing home setting and these studies measured falls by patient recall. However all the community based studies showed a significant association between falls and narcotics.10, 11, 12

COX2-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were initially hailed as a significant advance for the treatment of pain when first introduced in 1999: excellent analgesic effect without the GI toxicity of non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) nor the central nervous system (CNS) toxicity of opiates.13,14 However, after 5 years of use, certain COX2-selective agents were associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease leading to withdrawal of some of these agents at the end of 2004.15 In response, the American Heart Association (AHA) pain management recommendations identified the “…short-term use of narcotic analgesics as the first step in pain relief management.”16 The revised American Geriatrics Society (AGS) guidelines for the management of persistent pain in older adults recommends, “…nonselective NSAIDs and COX-2 selective inhibitors be considered rarely, with caution, in highly selected individuals and all patients with moderate to severe pain, pain-related functional impairment or diminished quality of life due to pain be considered for opioid therapy.”17 While these recommendations addressed concerns for cardiovascular complications related to these medications, Salomon et al reported that patients taking opiate analgesics suffered more cardiovascular complications and fractures than comparable patients taking either NSAIDs or COX2 selective agents.18,19

In this study, relationships are examined between analgesics prescribed for symptomatic management of pain in osteoarthritis and the incidence of falls and fractures among elderly patients with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis (OA). The focus was on changes after these COX-2 inhibitors were taken off the market. This understanding is timely, given the need to limit common adverse events and maximize potential health benefits in elderly patients. The hypothesis was that, since 2004, more narcotic analgesics would be used for pain management. The related hypothesis, an increased incidence of falls and fractures after 2004, was also examined.

METHODS

A cohort of 13,354 patients was used to examine the relationship between prescriptions for pain management and falls among community-dwelling elderly patients. The period of interest was the 9-year period of 2001 – 2009, the midpoint being the dates (Sept 2004 – April 2005) rofecoxib (Vioxx) and valdecoxib were pulled from the market. The study was approved by the Geisinger Institutional Review Board.

Study Participants

Geisinger Health System (GHS) is a vertically integrated system that provides primary and multispecialty health services to over 2.6 million people in central and northeast Pennsylvania, GHS has used an electronic medical records system (EMR) in all of its 41 ambulatory care clinics for over 10 years, facilitating research with community based populations and development of innovative care models. Patient information is routinely integrated into a common database that is shared across in-patient and out-patient settings. These data include personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender, height, weight; lifestyle (e.g., smoking, alcohol); clinical measures (e.g., BP, pulmonary function, BMD); digital imaging (MRI, CT, X-ray); ICD-9 diagnoses with labs, imaging, treatments or prescription orders. In addition, GHS provides a remarkably stable population across 31 counties (with the exception of two counties, the out migration rate is less than 1% per year) which offers unique opportunities for longitudinal research. The Geisinger EMR captures patients’ problem list as well as prescriptions provided to patients and the details surrounding the occurrence of adverse events.

Records of all elderly patients with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis during the years 2001–2009 were accessed from the Geisinger Health System data warehouse. Established for research purposes, the warehouse provides a shadow copy of the actual EMR and is housed on a separate server. Data is accessed by an honest broker (a non-research team member) and de-identified to comply with internal policy and the HIPAA Privacy Rule. For this study, the data set consisted of 13,354 patients for whom osteoarthritis was listed on their EMR problem list. Eligibility criteria included being 65 to 89 years of age (beyond 89 years is considered a potentially identifiable characteristic) and having received care from a Geisinger physician (in acute and ambulatory settings) between January 2001 and December 2009. During this 9 year period, a total of 3830 falls/fractures were documented for 2462 Geisinger patients.

Measurements and covariates

Diagnoses of falls and fractures were identified by ICD-9 codes (Table 1). These included codes for common falls among older individuals in non-hospital settings (i.e., from steps, furniture) as well as common fractures (i.e., hips, extremities). Falls that occurred in a hospital setting were excluded, as were spontaneous and spinal fractures. Conservative rules were established to address inconsistencies noted in the data accessed from the EMR. As one fall could be coded multiple times in different settings (e.g., emergency room, orthopedic follow-up visit) and coded both as a fall and as a resulting fracture, a combined fall/fracture variable was developed. Fall and fracture events were counted only once in a discrete 6-month period so that follow-up care was not considered a ‘new’ event.

Table 1.

ICD9 fall and fracture codes used to determine eligibility

| Accidental Falls | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| E880.0 | Fall on or from stairs or steps | E884.6 | Fall from commode |

| E880.1 | Escalator | E884.9 | Other fall from one level to another |

| E880.9 | Sidewalk curb | E887 | Fracture, cause unspecified |

| E881 | Fall from ladder or scaffolding | E888 | Other and unspecified fall |

| E884.2 | Fall from chair | E888.0 | Fall resulting in striking against sharp object |

| E884.3 | Gall from wheelchair | E888.1 | Fall resulting ins striking against other object |

| E884.4 | Fall from bed | E888.8 | Other fall |

| E884.5 | Fall from other furniture | E888.9 | Unspecified fall |

| Fractures | |||

| E800–804 | Fracture of skull (includes unspecified, none and any loss of consciousness | ||

| E807 | Fracture of rib(s), sternum, larynx, and trachea | ||

| E808 | Fracture of pelvis | ||

| E 809 | Ill-defined fractures of bones of trunk | ||

| E 810–819 | Fracture of upper limb | ||

| E 820–829 | Fracture of lower limb | ||

Analgesic prescriptions were categorized into the following hierarchy of three mutually exclusive analgesic treatment groups (1) Narcotics (NA) (opiate with or without other pain medication, including COX-2) (2) COX-2 (COX-2 selective agents with or without other pain medications but not Narcotics) or (3) NSAID group (NSAID with or without other pain medication, excluding Narcotics and COX-2) (Table 2). Many pain medications did not fit into these categories. For this preliminary study, the decision was made to exclude other medications, as the primary purpose was to compare narcotics with NSAIDS and COX-2 inhibitors.

Table 2.

Analgesic medications examined in this study

| Narcotic Analgesics | Cox-2 Inhibitors | Non-Narcotic/non- Cox-2 Inhibitor Analgesics |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Covariates included the obvious patient characteristics associated with fall risk: age, gender, and co-morbidity. Charlson Index scores (range 0 – 9) were calculated to indicate the overall influence of concurrent conditions on health, as higher scores reflect more co-morbidities.20 Although the Charlson Index is not a comprehensive risk tool, it is a valid measure of the prognostic impact of co-morbid disease that allowed us to address some potential confounders in this population.

Statistics

Falls were identified as a time-specific event in order to examine a set of potential influences in the time prior to the fall; a 6-month period was set as a “clean period” such that separate falls were defined as occurring at least 6 months apart. Variations in sample characteristics, analgesic medications, and incidence of falls were examined for each of the 9-years of study data and in the 2-study periods, 2001–2004 and 2005–2009 (COX2 and post-COX2). The characteristics of patients who experienced multiple falls were examined by looking backwards over the whole time period.

Analysis was undertaken to determine whether the higher age and co-morbidity level among patients receiving narcotic analgesic prescriptions accounted for the increased number and percentage of patients suffering falls/fractures. Incidence density sampling was employed to obtain unbiased results. Using exact matching methods, controls were matched 3:1 to cases according to gender, age (+/− 1 year) and Charlson Index score (+/− 1) calculated specific to the time the fall occurred. For each patient case experiencing a fall, controls (no fall/fracture) were randomly selected at the time a fall event occurred, excluding other cases with falls. Under this scheme, a patient was capable of being selected multiple times as a control.

A conditional logistic regression model was used to compare the effect of the different pain medications on the risk of falls for the two study periods, using SAS V9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to conduct an analysis for a matched study. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were obtained. The use of conditional logistic regression accounts for correlations induced by the matching of cases and controls and the possible selection of one case multiple times.

RESULTS

Study data consisted of 13,354 records identified for patients aged 65 – 89 years with a diagnosis of OA. Across this set, 87% received care in both the COX-2 and post-COX-2 time periods. Before the nested case-control analysis, patients with osteoarthritis who suffered falls/fractures were older and had more co-morbidities than the patients who did not suffer falls/fractures (Table 3). In the later period, patients suffering falls/fractures were also significantly more likely to be male, although this difference was small (Table 3). The smaller sample of patient records available for study during the first two years was likely due to early use of the EMR. It affected the totals reported for prescriptions and falls/fractures in each medication group for the early years, however this variability was addressed in the subsequent analysis with a nested case-control design, which may have led to an apparent increase in the variability in medication use and the fall rate.

Table 3.

Age, gender and Charlson Index scores of patients with falls/fractures (fx) during study periods.

| Fall or Fx | No Fall or Fx | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2004 | N | 236 (2%) | 11,475 (98%) | |

| Age(SD) | 73.8 (6.3) | 72.3 (6.6) | <.0001 | |

| Female | 91% | 91 % | 0.8540 | |

| Charlson Index (range) | 2.3 (0–12) | 1.7 (0–13) | <.0001 | |

| 2005–2009 | N | 1358 (10%) | 11,743 (90%) | |

| Age(SD) | 78 (6.7) | 77 (6.6) | <.0001 | |

| Female | 89% | 92% | 0.0007 | |

| Charlson Index (range) | 2.3 (0–12) | 1.6 (0–13) | <.0001 | |

SD=Standard Deviation

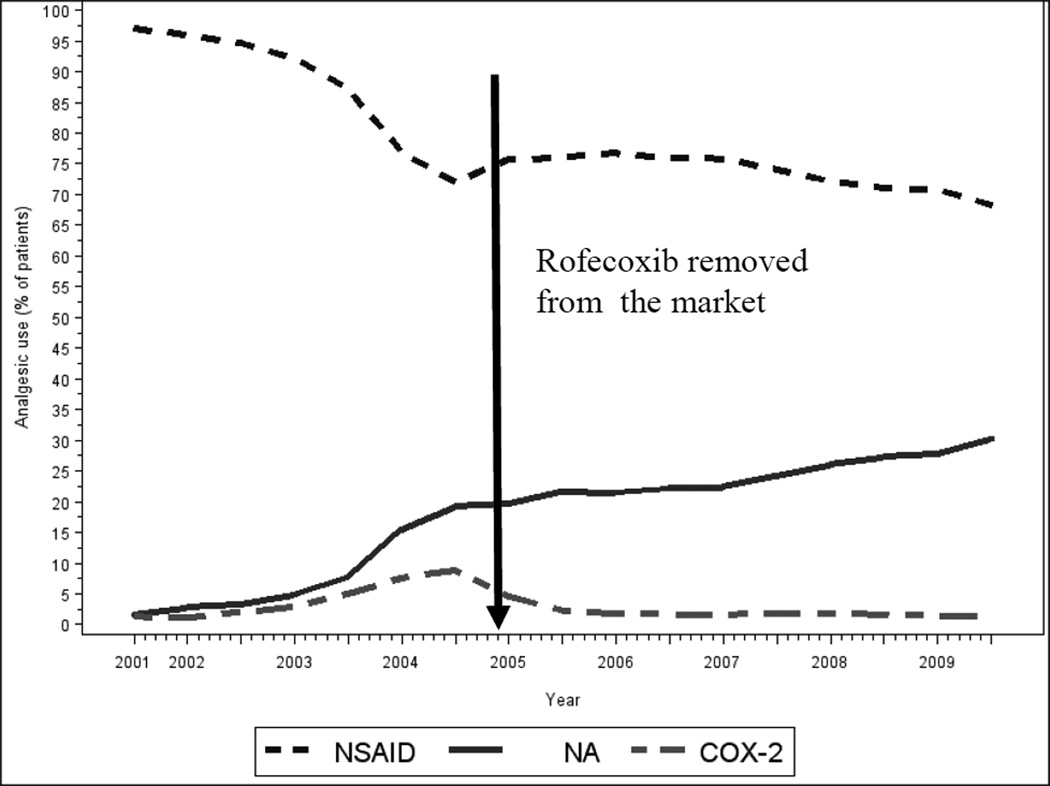

The percentage of patients who received narcotic prescriptions increased steadily over the period of study (Figure 1). In 2001, only 61 (1.6%) of the 3731 active patients were prescribed narcotic analgesics. This peaked in 2009, with 3329 (30.2%) of 11,012 active patients prescribed narcotic analgesics. In contrast, the percentage of patients who received prescriptions for COX2-selective agents reached a peak of 10% in 2004 followed by a rapid decline to 4% in subsequent years. At the outset of this study, nearly all of the OA patients received a prescription for NSAIDs. This declined by approximately one fourth by 2004, after which the percentage of OA patients who were prescribed NSAIDs remained stable for the duration of the period included in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prescription trends for the 3 analgesic groups

Fall rates for the entire group of elderly patients in this study increased 3-fold over the study period (Figure 2). A higher percentage of OA patients suffered falls/fractures in the post-COX2 study period (2005–2009) than in the earlier time period. The group of patients treated with narcotic analgesics accounted for the greatest number of falls/fractures. Although there appeared to be marked fluctuations and an overall increase in the percentage of patients suffering falls/fractures that were prescribed COX2-selective analgesics, the number of patients in the COX2 group was very small, leading to variability in the rate of falls and fractures (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Incidence of fall/fracture events for the 3 analgesic groups

Table 4.

Patient characteristics for analgesic prescriptions groups and overall sample according to study period and case-control status

| Case (OA with fall/fracture) | Control (OA without fall/fracture) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narcotics | Cox2 | NSAID | Overall | Narcotics | Cox2 | NSAID | Overall | |||||

| 2001–2004 | N | 251 | 44 | 547 | 842 | 343 | 152 | 2031 | 2526 | |||

| Mean Age (SD) | 72.5 (6.7) | 75.0 (5.3) | 72.0 (6.6) | 72.3 (6.6) | 73.1 (6.1) | 72.0 (6.3) | 71.9 (6.2) | 72.1 (6.2) | ||||

| Female CI Score (%) | 223 (88.8) | 41 (93.2) | 490 (89.6) | 754 (89.6) | 301 (87.8) | 140 (92.1) | 1821 (89.7) | 2262 (89.6) | ||||

| 0 | 83 (33.1) | 15 (34.1) | 274 (50.1) | 372 (44.2) | 90 (8.1) | 54 (35.5) | 972 (47.9) | 1116 (44.2) | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 115 (45.8) | 23 (52.3) | 211 (38.6) | 349 (41.5) | 175 (26.2) | 72 (47.4) | 800 (39.4) | 1047 (41.5) | ||||

| 3+ | 53 (21.1) | 6 (13.6) | 62 (11.3) | 121 (14.4) | 78 (22.7) | 26 (17.1) | 259 (12.8) | 363 (14.4) | ||||

| 2005–2009 | N | 1643 | 40 | 1305 | 2988 | 2028 | 173 | 6763 | 8964 | |||

| Mean Age (SD) | 76.1 (6.6) | 77.4 (6.5) | 75.8 (6.8) | 76.0 (6.7) | 75.8 (6.2) | 75.4 (6.4) | 75.9 (6.4) | 75.9 (6.3) | ||||

| Female CI Score (%) | 1444 (87.9) | 35 (87.5) | 1206 (92.4) | 2685 (89.9) | 1802 (88.9) | 157 (90.8) | 6096 (90.1) | 8055 (89.9) | ||||

| 0 | 378 (23.0) | 12 (30.0) | 474 (36.3) | 864 (28.9) | 385 (19.0) | 44 (25.4) | 2163 (32.0) | 2592 (28.9) | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 803 (48.9) | 19 (47.5) | 561 (43.0) | 1383 (46.3) | 974 (48.0) | 94 (54.3) | 3081 (45.6) | 4149 (46.3) | ||||

| 3+ | 462 (28.1) | 9 (22.5) | 270 (20.7) | 741 (24.8) | 669 (33.0) | 35 (20.2) | 1519 (22.7) | 2223 (24.8) | ||||

As noted above, in the total un-matched cohort of patients studied, falls/fractures were significantly more common among older patients with higher Charlson scores (Table 3). A total of 3830 fall/fracture events were experienced by 2462 patients during the study period. Patients suffering falls/fractures were matched 1:3 with osteoarthritis controls (no falls/fractures) according to age, gender and Charlson Index score at the time of the fall/fracture and calendar time, a sample totaling 7214 unique patients (Table 2). Most patients experienced a single fall/fracture (n = 1709, 69.4%); some fell twice (n = 443, 18.0%) and 310 (12.6%) fell 3 or more times. Patients who received narcotic analgesics were significantly more likely to suffer a fall/fracture in both study periods. Overall there was an odds ratio of 3.3 for falls/fractures for patients who received a narcotic analgesic when compared to patients who received a COX2 inhibitor, and 4.1 when compared to patients who received a NSAID (Table 5).

Table 5.

Fall risk by medication group

| Medication group | 2001–2009 study period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Narcotics vs. COX2 | 3.3 (2.5, 4.3) | <.001 | ||

| Narcotics vs. NSAID | 4.1 (3.7, 4.5) | <.001 | ||

| COX2 vs. NSAID | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | .095 | ||

| 2001–2004 study period 842 cases, 2526 controls | 2005–2009 study period 2988 cases, 8964 controls | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Narcotics vs. COX2 | 2.5 (1.7, 3.6) | <.001 | 3.7 (2.6, 5.4) | <.001 |

| Narcotics vs. NSAIDs | 3.0 (2.4, 3.7) | <.001 | 4.4 (4.0, 4.9) | <.001 |

| COX2 vs. NSAIDs | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | .289 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | .373 |

NSAIDs – non-steroidal anti-inflammatories

OR– Odds Ratio

95% CI – 95% Confidence Interval

DISCUSSION

It is reported here that, as the percentage of elderly patients with osteoarthritis who were prescribed opiate analgesics increased, there was a corresponding increase in the percentage of elderly patients who suffered falls or fractures. Moreover, most of the increase in the percentage of patients suffering falls/fractures after 2004 was accounted for by patients who were prescribed narcotic analgesics. While patients suffering falls and fractures were older with significantly more comorbidities, after controlling for age and comorbidities, narcotic analgesic prescriptions remained a significant risk factor. This emphasizes the salience of discussing fall precautions and assessing fall risks as part of analgesic treatment.

The investigation of a disease such as osteoarthritis has inherent difficulties as the severity and chronicity of pain can be difficult to judge from an objective standpoint. To address the concern that patients who were prescribed narcotics are different than patients given COX2s or NSAIDS the Charlson index score was used and patients were also matched based on age and gender. As falls are so closely associated with mortality2, utilizing a risk tool such as the Charlson index that predicts risk of death from other comorbidities provided a way of ensuring that matched patients’ mortality risks were similar.

Study limitations include lack of data regarding the duration of analgesic use in relation to a fall/fracture event or the use of other medications associated with falls or known to affect sensorium. Likewise, no data were collected to confirm that analgesic prescriptions were filled or if other prescriptions were received from physicians in other health systems. Certain medications were not included in our analysis such as tramadol which has some narcotic properties and propoxyphene hydrochloride, a narcotic which has been removed from the market. Baseline pain levels and effectiveness of pain management among patients with falls was not explored. The conservative coding rules likely undercounted falls, as some elderly patients have recurrent falls and many do not seek medical attention for falls. No data were examined regarding the fall risks surrounding gait, vision, living situation, and social supports. Likewise, the data did not capture the possible influence of disability level, neurologic disorders (e.g., Parkinson), obesity, and concurrent drugs (e.g., antidepressants), nor were the data reviewed for fractures unrelated to other traumas, such as an auto accident. As with all case-control studies, this study was susceptible to confounding. Attempts to control were made by matching based on Charlson Index score, age and gender. Clearly, there are other risks that would need to be controlled for in a more detailed, thorough study.

Over the course of this decade, physician prescribing habits underwent a significant change for this elderly population suffering from osteoarthritis. At the beginning of the decade an increasing number of elderly patients were prescribed selective COX2 inhibitors for the treatment of osteoarthritis. As the number of reports of cardiovascular toxicity of COX2 inhibitors and NSAIDs increased in 2003–2004 there was a concomitant decline in use of these agents and a growing percentage of patients were prescribed narcotic analgesics. By the end of the decade, nearly 40% of this population was being treated with narcotic analgesics. Guidelines promulgated in 2007 by the American Heart Association validated and encouraged this prescribing trend although the morbidity and mortality of falls and fractures associated with narcotic analgesic use was not considered in developing these practice guidelines. A recent epidemiologic study suggests that use of narcotic analgesics is associated with a significantly greater risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality than NSAIDs and selective COX2 inhibitors.21 It is unlikely that guidelines recommending use of narcotic analgesics, even short term use as first line therapy for elderly patients with osteoarthritis, would have been promulgated by the American Heart Association or the American Geriatrics Society if information about the risks were known at the time. Nonetheless, we suggest that some consideration be taken to revise these guidelines with new emerging evidence associated with narcotics.

The association between prescriptions for narcotic analgesics and falls/fractures in this population may reflect the known CNS effects of narcotics analgesics, which is often compounded by age.21,22 Younger patients are at less risk of injury from falls/fractures than elderly patients because of greater muscle mass, better balance, and less osteoporosis. Nonetheless, prescription of even short term narcotics for relief of osteoarthritis pain is likely to lead to other forms of morbidity and mortality.

The results of this preliminary study, that narcotic use increased alongside documented fall events and fracture injuries, suggests an unintended consequence of adoption of a change in treatment practices without due consideration of potential side effects. This deleterious change in prescribing habits, even though effected to combat a potentially serious side effect of a new and expensive form of drug therapy, selective COX2 inhibitor-associated cardiovascular toxicity14, led to a significant increase in morbidity in this elderly population of patients with osteoarthritis. The growing national movement to develop and enforce practice guidelines to improve quality of care is likely to reduce prescription of unnecessary or dangerous procedures and drugs and reduce complications. Nonetheless, we believe the current guidelines for the treatment of pain, which include first-line prescription of narcotics, should be re-evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We also recognize the contributions of our project manager, Mary Ann Blosky, MHA MSN RN.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AR56672, AR56672S1, and AR54897; the NYU-HHC Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1RR029893); and a joint New York University Langone Medical Center/Geisinger Health Systems seed grant.

Consultant (within last 2 years, all <10,000): Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Novartis, CanFite Biopharmaceuticals, Cypress Laboratories, Regeneron (Westat, DSMB), Endocyte, Protalex, Allos, Inc., Savient, Gismo Therapeutics, Antares Pharmaceutical, Medivector

Stock: CanFit biopharmaceuticals received for membership in Scientific Advisory Board.

Grants: King Pharmaceuticals, NIH, Vilcek Foundation, OSI Pharmaceuticals, URL Pharmaceuticals, INC., Gilead Pharmaceuticals

Board member: Vilcek Foundation

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor of this study had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Cronstein would like to disclose the following, none of which are relevant to this work: Intellectual property: patents on use of adenosine A2A receptor antagonists to promote wound healing and use of A2A receptor antagonists to inhibit fibrosis. Patent on use of adenosine A1 receptor antagonists to treat osteoporosis and other diseases of bone. Patent on use of adenosine A1 and A2B Receptor antagonists to treat fatty liver. Patent on the use of adenosine A2A receptor agonists to prevent prosthesis loosening.

Author Contributions: Lydia Rolita, Adele Spegman and Bruce Cronstein were involved in the study concept design, interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript. Xiaoqin Tang was involved in the data analysis, interpretation of data and manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Loughlin JL, Robitaille Y, Boivin JF, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for falls and injurious falls among the community-dwelling elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;37:342–354. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterling DA, O'Connor JA, Bonadies J, et al. Geriatric falls: Injury severity is high and disproportionate to mechanism. J Trauma. 2001;50:116–119. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1279–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710303371806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romero LJ, et al. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility in elderly fallers. Age Ageing. 1997;26:189–193. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens JA, Corso PS, et al. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev. 2006;12:290–295. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:664–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French DD, Campbell R, Spehar A, et al. Drugs and falls in community-dwelling older people: A national veterans study. Clin Ther. 2006;28:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang CM, Chen MJ, Tsai CY, et al. Medical conditions and medications as risk factors of falls in the inpatient older people: A case-control study. Int J Psychiatry. 2011;26:602–607. doi: 10.1002/gps.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agashivala N, Wu WK. Effects of potentially inappropriate psychoactive medications on falls in US nursing home residents: Analysis of the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey database. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:853–860. doi: 10.2165/11316800-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller M, Sturmer T, Azreal D, et al. Opoid analgesics and the risk of fractures in older adults with arthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebly EM, Hogan DB, Fung DS, et al. Potential adverse outcomes of psychotropic and narcotic drug use in Canadian seniors. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:857–863. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Mangione CM, et al. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Central nervous system-active medications and risk for falls in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1629–1637. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laine L, Connors LG, Reicin A, et al. Serious lower gastrointestinal clinical events with nonselective NSAID or coxib use. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:288–292. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines: Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1905–9015. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1905::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1092–1102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. An update for clinicians: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115:1634–1642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.181424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1979–1986. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1968–1975. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic co-morbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Incalzi RA, et al. Age related pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic changes and related risk of adverse drug reactions. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:571–584. doi: 10.2174/092986710790416326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercadente S, Ferrera P, Villari P, et al. Opioid escalation in patients with cancer pain. The effect of age. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]