Highlights

► We present a novel method for the causal analysis of high-dimensional time series. ► This method combines factor models and Granger causal analysis. ► An application is the detection of epileptic seizure onset zone based on ECoG data.

Keywords: Granger causality, Factor model, Principal Component Analysis, EEG, Epilepsy, Onset zone detection

Abstract

Granger causality is a useful concept for studying causal relations in networks. However, numerical problems occur when applying the corresponding methodology to high-dimensional time series showing co-movement, e.g. EEG recordings or economic data. In order to deal with these shortcomings, we propose a novel method for the causal analysis of such multivariate time series based on Granger causality and factor models. We present the theoretical background, successfully assess our methodology with the help of simulated data and show a potential application in EEG analysis of epileptic seizures.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

In many cases the problem of identification of the dependence structure in multivariate time series arises. This is important, for example, in biology and economics, and in particular for neuroscience data, e.g. electroencephalographic (EEG) data, where the connections between brain regions are analyzed.

Investigations of this kind have been conducted in several ways, which include (Formisano et al., 2008; Astolfi et al., 2005; Pereda et al., 2005; Möller et al., 2001; Cassidy and Brown, 2002; Gates et al., 2010).

The focus of this paper will be on the detection of Granger causality in multivariate time series which show strong co-movement, i.e. high correlation between the component-series. In Granger (1969) the causality between two time series is analyzed. The idea of this causality concept is based on predictability: if the knowledge of the past of one time series improves the prediction of a second one, the first is said to be Granger causal for the second. Note that this specific definition is just one possible way among many of defining causality. We refer the interested reader to Bressler and Seth (2011) for background information on Granger causality and to Pearl (2000) for a historical overview of causality.

Multivariate extensions of this causality concept have been developed, for recent references see e.g. Lütkepohl (2007) or Eichler (2007). Besides, various topics of Granger causality have been discussed, see e.g. Sims (1972), Geweke (1982), Dhamala et al. (2008), Barnett and Seth (2011) and Marinazzo et al. (2011). For recent applications in neuroscience see e.g. Guo et al. (2008), Liao et al. (2010), Sommerlade et al. (2012) and Flamm et al. (2012).

In practice we often encounter high-dimensional time series, which show co-movement. As this co-movement normally generates numerical problems, the question arises how to investigate the causality structure of these data.

For the analysis of highly correlated data, such as EEG data, factor models are a useful tool, see e.g. Molenaar and Nesselroade (2001) and Molenaar (1985). The idea behind factor models is the separation of the observations into latent variables (describing the co-movement) and noise. The latent variables are described by a small number of factors. In this modeling approach, up to now causality was not considered.

In this paper we propose a methodology for the causal analysis of high-dimensional co-moving data, by combining factor models and Granger causality analysis. We will present the theoretical background as well as an application to simulated data and to EEG recordings.

This paper is structured as follows: in order to get a grasp of Granger causality and factor models, we give a short introduction to both topics in the remainder of this section. In Section 2 we apply Granger causality to factor models and discuss the challenges arising. In Section 3 we propose a methodology for this kind of analysis. We apply this methodology to simulated and EEG data and present the results in Section 4. This paper is concluded in Section 5.

1.2. Mathematical background and notation

In this paper we distinguish between two different types of processes. In the classic Granger causal analysis we investigate n-dimensional stochastic processes generated by n components, as discussed in this section. In the factor model case we analyze n-dimensional stochastic processes , whose latent variable process is generated by a small number of components, as discussed in Section 1.5. For notational purposes we simply write y when referring to the whole stochastic process , this also applies for all other processes.

For the classic Granger causal analysis, we consider an n-dimensional stochastic process , , which is weakly stationary with mean zero. We refer to Hannan and Deistler (2012) and Brockwell and Davis (1991) for treatment of time series.

In this paper we only consider linearly regular processes, which admit a Wold representation, see Rozanov (1967) and Hannan (1970). The covariance function of y is given by . For the remainder of the paper we assume, that ∑∥ γ(s) ∥ < ∞ holds and that the spectral density

| (1) |

is uniformly bounded above and below, i.e. there exists a real constant c such that1

| (2) |

holds. According to Wiener and Masani (1957), this assumption yields that y(t) has an AR(∞) representation

| (3) |

where , and A(0) = In holds. The right-hand side ɛ(t) is white noise, i.e. , and Σ denotes its positive definite covariance matrix. We additionally assume that even holds.

We use z to denote the backshift operator on : , as well as a complex variable. Using this notation we may rewrite Eq. (3) as

| (4) |

where exists inside and on the unit circle.

We additionally assume that the stability condition det a(z) ≠ 0 for |z| ≤ 1 holds.

By using we rewrite (4) as

| (5) |

The transfer function exists inside and on the unit circle. There is a unique weakly stationary solution of (3) of the form

| (6) |

This solution (6) of the system (3) is called an autoregressive (∞) process. It corresponds to the Wold representation. For the sake of simplicity of notation we will skip the (∞) sign henceforth.

For a stationary process z, let denote the space spanned by the past and present of z in the Hilbert space of all square integrable random variables. Time t represents the present unless noted otherwise.

Note that, if (2) holds for the whole process, it also holds for all sub-processes, and therefore all subprocesses have AR representations.

Due to the nature of our application, we will often refer to their components as channels in this paper.

1.3. Granger causality

There have been long and thorough discussions about causality throughout the last decades, a brief summary can be found in Pearl (2000). As already stated various ideas exist how to formalize causality. The definition we will use for our causal investigation is Granger causality, as introduced in Granger (1969), based on a suggestion in Wiener (1956).

According to the original definition in Granger (1969), we say a time series y1 is causing another time series y2, denoted by y1 → y2, if we are able to predict y2 better using all available information in the universe than using all information apart from y1.

Granger's definition is based on the decrease of the variance of the (linear least squares) prediction error. For a better understanding we present an equivalent definition of Granger causality based on the autoregressive coefficients for the bivariate case.

1.3.1. Definition of bivariate Granger non-causality

Let y(t) = (y1(t), y2(t))′ satisfy the assumptions of Section 1.2, then we consider the joint AR representation (5) at time point t + 1.

| (7) |

We say that y1 is Granger non-causal for y2 if A21(m) = 0 ∀ m (i.e. ). In other words does not influence the prediction of y2(t + 1).

Otherwise we say y1 is Granger causal for y2. In this case the knowledge of the present and past of y1 improves the prediction of y2(t + 1), i.e. the variance of the prediction error is smaller when using the past and present of both y1 and y2 compared to using only the past and present of y2 itself.

Because of the properties of AR representations, the lower line of Eq. (7) represents the orthogonal projection of (y1(t + 1), y2(t + 1))′ onto its past, which is its best linear (least squares) predictor.

1.4. Multivariate Granger causality

In the last section we considered the bivariate case. For our purposes we use the multivariate extension of Granger's classic definition according to Eichler (2007), restricted to the causality between two component-processes.

For the remainder of the paper we will focus on n-dimensional stationary processes. Let V = {1, …, n}, and we use the notation yV for y to stress the fact that the elements of V correspond to the one-dimensional component processes of y. To refer to a subprocess corresponding to I ⊂ V we write yI(t) = (yi(t)|i ∈ I)′, for a (univariate) component process we simply write yi. With these notations we are able to state the following definition.

1.4.1. Definition of Granger non-causality

Let i, j ∈ V (i ≠ j). Then the process yi is Granger non-causal for yj with respect to yV, denoted by yi ↛ yj|yV, if

| (8) |

(⇔Aji(m) = 0 ∀ m) i.e. if the (j, i)-element of the AR power series in the AR representation (5) is zero. Of course, this means aji(z) = 0 in (4).

In other words, the past and the present of yi do not influence the linear prediction of yj(t + 1) in the AR representation of yV.

Otherwise we say the process yi is Granger causal for yj with respect to yV, which we will denote as yi → yj|yV. If the relation has not been derived yet we will sloppily write .

This definition of causality is sometimes referred to as conditional Granger causality, because the causal effect of yi on yj conditioned on yV∖{i,j} is analyzed.

For the interested reader we note that for a complete causal analysis of a process yV all causality relations for arbitrary sub-processes have to be considered, not only the causality relations between two component-processes with respect to the whole process, see Eichler (2006). However, the causality relations between two component-processes with respect to the whole process are sufficient for our purposes.

Note that up to now we have only considered regular AR systems, i.e. AR systems where Cov(ɛ(t)) = Σ is regular, because the presented definition of Granger causality is based on them. In Section 2 we will loosen this restriction.

1.5. Factor models

Factor models are useful for the analysis and forecasting of high-dimensional time series, when the single time series show similarities or a kind of co-movement. The idea of factor models is to separate the n-dimensional observations x(t) into a part representing the co-movement χ(t) (also referred to as latent variables) and a part representing the noise of the data η(t):

| (9) |

Hereby the n-dimensional latent variables χ are generated by a q-dimensional process, where q << n. These q driving processes are called factors, there from the term factor model. We assume that x is stationary with mean zero.

The co-movement χ(t) describes the common movement of the data and η(t) the residual part of the data, for ECoG data we describe this in detail in Section 4.2.

For our purposes we will separate the latent variables χ(t) from the noise by means of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and derive the static factors z(t). See Pearson (1901), Hotelling (1933) and Jackson (2004) for background information on PCA.

In the second step we will model the static factors z(t) as a regular AR process.

The described modeling approach is sometimes referred to as a quasi-static factor model, see e.g. Deistler and Zinner (2007).

In detail we proceed as follows:

In order to separate x(t) = χ(t) + η(t), we apply the PCA: we calculate the eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix Ω of the observed variables x(t)

where Γ = diag(λ1, …, λn) contains the ordered eigenvalues λ1 ≥ λ2 ≥ … ≥ λn > 0 and O is an orthogonal matrix. O1 contains the first q columns of O corresponding to the q largest eigenvalues, respectively O2 the remaining n − q columns.

Let

be the q-dimensional (q < n) static factors. Then the n-dimensional latent variables are obtained by

| (10) |

where Λ is termed factor loading matrix. As is well known, one could generate other static factors by premultiplication with a regular (in particular orthogonal) matrix U

However, this will not impair our causality analysis in Section 2, because the spaces spanned by the original static factor z(t) and the rotated ones are equal.

Proceeding, we assume the static factors z(t) to satisfy the requirements of Section 1.2, in particular assumption (2), and we model them as a regular AR process

| (11) |

where a(0) = Iq and Cov(ɛ(t)) = Σ > 0.

Eqs. (10) and (11) and the causal invertability of a(z) together yield

| (12) |

In other words the q-dimensional white noise process ɛ generates the n-dimensional latent variables χ.

2. Granger causality for factor models

In this section we discuss the application of Granger causality to factor models.

2.1. Challenge

What is the challenge in using Granger causality for the analysis of high dimensional co-moving data? The naïve approach would be to fit an n-dimensional AR model to the n-dimensional observations x(t). In practice we typically encounter two problems:

First, Granger causality analysis is usually considered in the case of regular AR systems, i.e. where the error covariance matrix Σ is regular (compare Section 1.4). As EEG data are highly correlated and show strong co-movement, regular AR models lead to a poor estimation and misleading results of the subsequent causality analysis. A visual analysis of EEG data quickly confirms this co-movement.

Second, fitting of a n-dimensional AR(p) model requires the estimation of n2p parameters. In order to obtain reliable estimators a large sample size is required, in particular for large cross-sectional dimension n. However, as neurological signals (in particular EEG) show a highly non-stationary behavior, such large sample sizes impair the estimation quality. Again, this leads to poor results of the causality analysis.

In order to avoid these problems we consider factor models. Naturally the question arises, which causalities can be reasonably analyzed in this context. In this paper we assume that the dependence of the latent variables χ(t) properly reflects the causal structure of the observations x(t). This assumption seems meaningful despite the separation (9) into noise and latent variables, as will be discussed in Section 5.1. This assumption is not necessarily satisfied, see Anderson and Deistler (1984).

The first idea for a causal analysis in the factor model case would be to consider relations of the form

| (13) |

However the usage of the exhaustive set V leads to problems: relation (13) is derived from the projection of χj(t + 1) onto , compare criterion (8). Although the projection itself is unique, the projection coefficients are not, i.e. the contribution of the single χi(t), χi(t− 1), … to the explanation of χj(t + 1) is not uniquely determined. This is due to the fact that χV(t) contains linear dependent elements. As these contributions are not unique, the application of criterion (8) is not reasonable. Thus an analysis involving relations of the form (13) is not meaningful.

Note that in special cases the above problem might not arise.

Therefore we restrict the conditioning set, instead of V we use channel selections I ⊂ V, # I = q < n.2

We consider relations of the form

| (14) |

In the following we will discuss the choice of the channel selection I, such that relations of the type (14) yield reasonable results.

2.2. Framework

For a channel selection I ⊃ i, j we consider the corresponding sub-system of (12)

| (15) |

where ΛI is the square sub-matrix of Λ corresponding to the selected components χI.

In order to yield reasonable causal relations of the form (14) we only consider channel selections I where the corresponding ΛI is regular. In the remainder of this paper we will call such I admissible.

By rewriting (15) as an AR representation we obtain

| (16) |

with det(ΛI) ≠ 0. Note that we premultiply (16) with ΛI in order to obtain the leading coefficient of the left-hand side polynomial as the identity, .

The Granger causality relations of this representation (16) can easily be checked by criterion (8), which is of the form

However, it is important to note that the causality relations do depend on the channel selection I. This can be seen from the following example. Consider the following system

| (17) |

with Cov(ɛ(t)) = I3. The sub-process χ123 has the following AR representation

| (18) |

and for the sub-process χ124 we have

| (19) |

with

| (20) |

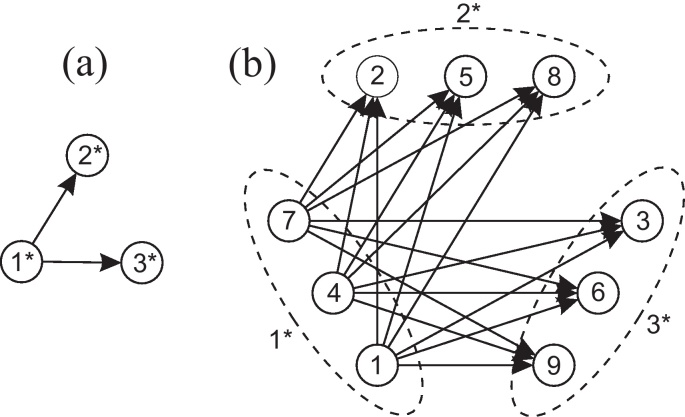

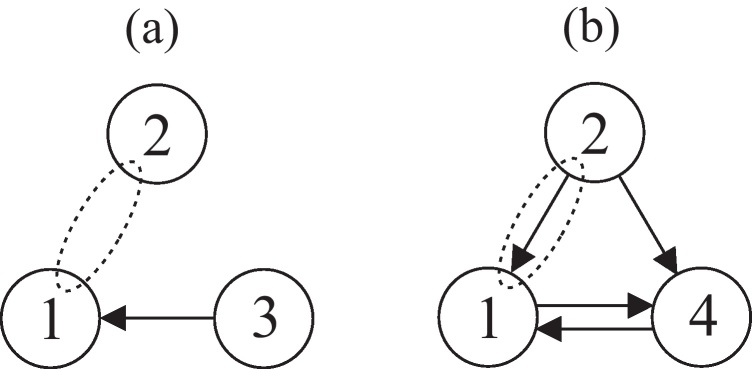

According to criterion (8), in subsystem (18), χ2 is Granger non-causal for χ1 due to a12(z) = 0. In subsystem (19) a12(z) ≠ 0, thus χ2 is Granger causal for χ1. Compare Fig. 1 for a graphical representation of these two subsystems.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the dependence relations of two subsystems of system (17), an arrow indicates Granger causality. Different causality relations between χ2 and χ1 depending on the considered channels: (a) associated path diagram for sub-system (18): χ2 ↛ χ1|χ123 and (b) associated path diagram for sub-system (19): χ2 → χ1|χ124.

For the interested reader we note that it is also possible to use generalized dynamic factor models, as discussed in Deistler et al. (2010), as a basis for the Granger causal analysis.

3. Methods and materials

We apply the method discussed above to EEG recordings. As we have seen in the previous section, a strict Granger causality investigation between channel i and j depends on the chosen channel set I. Different channel selections I and may lead to different results. However, we are interested in a single overall statement, whether channel i influences channel j or not.

For this purpose we propose a workable methodology, which is based on the ideas of Section 2.2. We will apply it to simulated data and to EEG recordings taken from an epilepsy patient.

3.1. Proposed method

Our methodology consists of three steps. First, we use PCA to separate the observations into the latent variables (explaining the co-movement) and the noise, see Section 2.2. As discussed in Section 2.1, we assume that the causal structure of the observations is reflected in the causality structure of the latent variables.

Second, for fixed i and j we analyze the conditional Granger causality relation , given a fixed channel selection I ⊃ i, j.

Third, we perform this analysis for all admissible channel selections and derive a heuristic statement for the influence from χi to χj, condensing the information of all sub-systems.

In detail we proceed as follows:

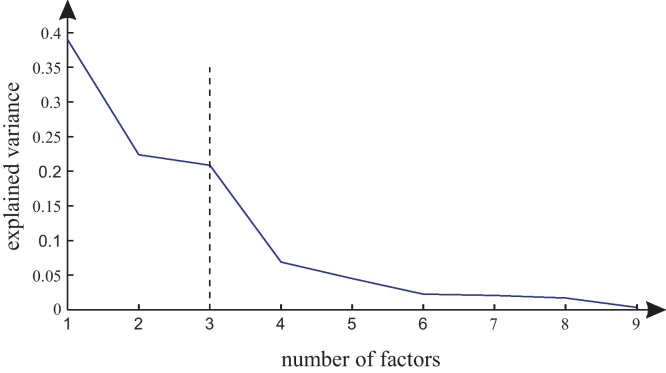

First we perform a PCA on the observations x in order to obtain the factor loading matrix Λ and the static factors z. The dimension of the static factors q is determined via a Scree plot, see Cattell (1966). In this graphical method the principal components are sorted according to their explanation of the total variance of the data in descending order. Usually some kind of bending point can be observed in this graphical representation, which divides the principal components into important and unimportant ones, see Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Scree plot of the Principal Component Analysis of the simulated data from signal model (21). Three factors explain the majority of the variance.

Now let i, j, I be fixed. The straight-forward application of the approach of Section 2.2 yields two problems:

While in theory we can easily distinguish regular and singular matrices ΛI in Eq. (16) by considering the determinant, the estimator will typically yield . The causality relations drawn from systems with very small values of are not meaningful, which is due to the fact that in (16) cannot be computed reliably. The term is a measure for the similarity of the selected channels. Therefore we only consider channel selections I with exceeding a threshold τ. This threshold is chosen empirically in order to yield reasonable results.

A similar challenge arises in the estimation of (which has a finite order now). In theory signifies that χi is Granger non-causal for χj. However, in estimation we typically have , so we have to statistically test whether the polynomial coefficients (for all lags m) are significantly jointly different from zero.

For this purpose we use an F-test (), which is implemented in the GCCA toolbox and described in Seth (2010). We consider the p-value of the test as a measure for Granger causality: rejection of (p < 0.03) signifies Granger causality, acceptance means non-causality.

In order to sum up, for each channel selection I (for fixed i, j) we obtain two values: as a similarity measure of the channels in I and the p-value as an indicator for the causality from χi to χj.

As a global influence statement from χi to χj is our goal, we want to condense the different conditional causality statements based on distinct channel selections I into a single one. For this purpose we propose an intuitive rule: if all statements for distinct channel selections match, we conclude a global influence statement.

In other words: if χi → χj|χI for all I with , we say that χi influences χj. On the other hand, if χi ↛ χj|χI for all I with , we say that χi does not influence χj. In case of non-conclusive Granger causality statements we do not derive any global influence statement.

Finally, as the causality structures of the observations and the latent variables are equal by assumption (compare Section 2.1), we say xi influences xj if χi influences χj. The analog reasoning holds in case of non-influence.

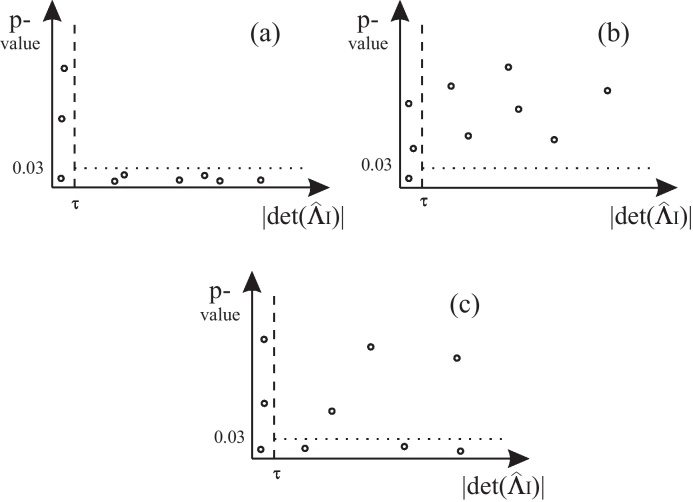

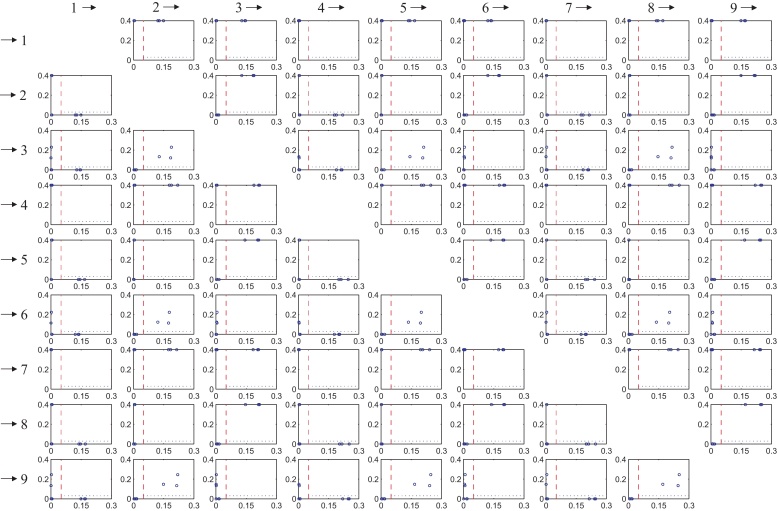

For a better understanding we want to visualize the described methodology: for i, j fixed we plot a point for each distinct channel selection I ⊃ i, j into the plane spanned by on the x-axis and the p-value on the y-axis. This procedure yields graphs such as shown in Fig. 2. In such a plot we only consider points with , which are located to the right of the dashed vertical threshold line. Points to the left of this determinant threshold line are ignored, because the corresponding p-values are not meaningful due to numerical instabilities.

Fig. 2.

Visualization of the proposed method. Analysis for all causality relations χi → χj|χI for distinct channel selections I ⊃ i, j. In each plot a point shows the p-value (as a measure of causality) and (as a measure of channel similarity) for the respective channel selection I. Points with only are considered in the analysis (numerical reasons). (a) All relevant points have an associated p-value <0.03, i.e. indicate causality (for each respective I). We conclude that xiinfluences xj, (b) all relevant points have an associated p-value >0.03, i.e. indicate non-causality (for each respective I). We conclude that xidoes not influence xj and (c) for different I, causality as well as non-causality statements are indicated. We do not conclude any influence statement.

A point situated below the dotted line represents a p-value <0.03 and therefore indicates Granger causality. Consequently a point lying above the dotted line indicates Granger non-causality.

Fig. 2, where each plot is constructed as described above, illustrates the three cases we distinguish:

In plot (a) all relevant points are situated below the dotted line, i.e. each point individually indicates causality ( of non-causality rejected due to p < 0.03), thus we have global influence. We observe the opposite situation in plot (b), where all relevant points are above the dotted line, i.e. each point individually indicates non-causality, so we speak of global non-influence.

Plot (c) illustrates a situation where distinct channel selections lead to Granger causality as well as Granger non-causality statements. In this case, we refrain from concluding on global influence.

In the final application we distinguish only if χi influences χj (and therefore xi influences xj) or not. Bayesian inference could be used in this context to distinguish between these two cases. However, the calculation of prior distributions and a Bayes factor would be difficult.

3.2. Signal model

In order to assess the proposed methodology we apply it to simulated data where we know the imposed dependence structure. Consider the following signal model

| (21) |

First we simulate the 3-dimensional static factors z(t) as an AR(2) process with

and Cov(ɛ(t)) = I3.3 For the construction of x(t) we choose the factor loading matrix

and the variance of the noise

The Granger causality structure of the simulated 3-dimensional static factors is depicted in Fig. 3(a), the resulting influence structure of the 9-dimensional co-moving system (x1, …, x9)′ in Fig. 3(b). Note that the simple design of Λ yields the clear graph in plot (b).

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the dependence structure of signal model (21). (a) Granger causality structure of the simulated static factors (arrows indicate conditional Granger causality) and (b) influence structure of the simulated observations (arrows indicate influence).

3.3. ECoG data

In order to demonstrate the practicability of our methodology we apply it to invasive EEG data taken from a patient suffering from epilepsy.

Epilepsy is defined as a neurological disorder with recurring unprovoked seizures, it affects 0.7% of the general population (see Hirtz et al., 2007). Seizures are characterized by abnormal hypersynchronous neuronal activity, which can affect both hemispheres of the brain (generalized seizure) or a circumscribed area in one hemisphere (focal seizure). About one third of patients with focal epilepsies develop drug resistant seizures, which cannot be cured with a medical therapy. If a clear identification of the seizure onset zone, i.e. the area where the seizure starts, is possible, a resective surgical intervention is a valuable treatment option (see Schuele and Lüders, 2008). This identification is done by a visual inspection of the EEG data by clinicians, which is a difficult and time consuming task. For a better spatial resolution (in particular if EEG is insufficient for the localization) an invasive recording using subdural strip electrodes (electrocorticography, ECoG), which are placed directly on the brain surface, is performed (see Pondal-Sordo et al., 2007).

While the visual inspection of the ECoG data is still regarded as gold standard, see Götz-Trabert et al. (2008) and Jenssen et al. (2011) for two recent studies, there has been an increasing interest in a mathematical analysis of these data. In particular causality measures, aiming at the quantification of the aforementioned synchronous activity, have been used to detect the seizure onset zone, see e.g. Kim et al. (2010) and Wilke et al. (2008).

By applying our proposed methodology to ictal ECoG data, i.e. recordings during an epileptic seizure, we follow this technical approach of locating the seizure onset zone.

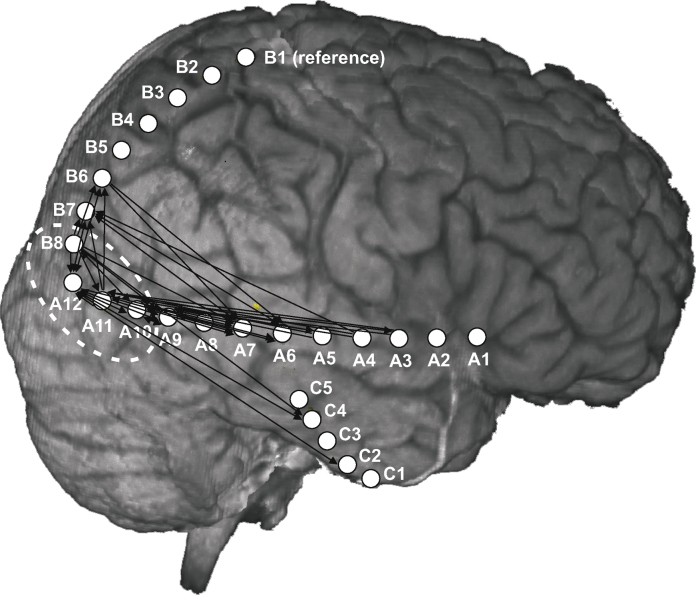

The ECoG data used in this exemplary study are taken from a patient (male, 43 years) suffering from therapy-resistant focal epilepsy. The patient underwent a presurgical long-term video EEG monitoring at the Hospital Hietzing with Neurological Center Rosenhügel. Three subdural strip electrodes with a total of 25 channels were implanted, and the electrode B1 (outside the seizure focus) was chosen as reference. Compare the MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan in Fig. 8 for details. Recording was performed using a Micromed® system at a sampling frequency of 1024 Hz. After recording, the ECoG data were preprocessed in Matlab®: line interference was removed using a notch filter at 50 Hz, and a high-pass filter at 1 Hz was applied in order to get rid of physiologically irrelevant low-frequency contributions. The signals were low-pass filtered at 64 Hz in order to avoid aliasing and then downsampled to 128 Hz sampling rate.

Fig. 8.

Results of the influence analysis of the ictal ECoG data. MRI scan of the patient's brain together with the subdural electrode strip positions, arrows indicate influence between the respective electrodes. Electrodes with the highest number of departing arrows are considered to represent the seizure onset zone (B8, A12, A11 and A10), compare the out-degree histogram in Fig. 9.

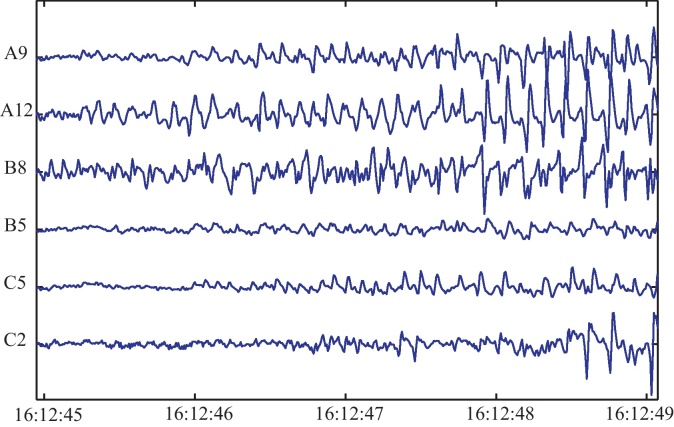

In this paper we analyze the beginning of the first seizure which occurred during the recording time. For the identification of the seizure onset zone we use data from a 4 s time window (as indicated by the clinicians) consisting of 24 recorded channels. Fig. 4 shows 6 selected channels of the ECoG recordings during the investigated time interval.

Fig. 4.

Ictal ECoG data. 6 selected channels of the analyzed 4-s segment from the initial phase of the seizure.

As can be seen, the data seem to be non-stationary, this point will be discussed thoroughly in Section 5.2.

4. Results

4.1. Signal model

We apply our methodology to the simulated data from the signal model (21).

For the initial calculation of the PCA, we determine the number of static factors q by considering the Scree plot, see Fig. 5. This figure shows the percentage of the explained variance per factor. We observe that three factors explain the majority of the variance, thus we choose q = 3. Furthermore, by application of the BIC criterion we obtain an AR-model order of p = 2 (matching the imposed model order).

Proceeding according to our methodology, for fixed source i and target j we obtain causality relations for all channel selections I ⊃ i, j. They are represented as points in a graph as described in Section 3.1. Compare Fig. 2 for the idea. Hereby points with p-values >0.4 are displayed with p-value = 0.4, because this does not change the results of the analysis (highly non-significant anyway) and facilitates the visualization.

In Fig. 6 all these plots are arranged in a 9 × 9 matrix plot, where the columns indicate the source channels xi and the rows the target channels xj. Clearly, the (j, i)-subplot quantifies the influence from xi to xj. Obviously, diagonal elements are not displayed.

Fig. 6.

Results of the influence analysis of signal model (21) in matrix plot form. Columns indicate the source channels xi and the rows the target channels xj, the (j, i)-subplot quantifies the influence from xi to xj. Only points to the right of the dashed threshold line are considered due to numerical reasons (reasonable points). If all reasonable points are located under the dotted line we say xi influences xj, compare the interpretation in Fig. 2. This analysis yields the influence structure illustrated in Fig. 3(b).

Let us consider the interpretation of three selected subplots in Fig. 6 in detail:

In subplot (3, 1) all points to the right of the determinant threshold line are located below the dotted line, and therefore represent p-values smaller than 0.03 (i.e. the null hypothesis of non-causality is rejected). This means that for all admissible channel selections I, we have χ1 → χ3|χI. Thus we say x1 influences x3.

In subplot (3, 2) all points to the right of the determinant threshold line are located above the dotted line. Thus we say x2 does not influence x3.

In subplot (4, 1) all points are located to the left of the determinant threshold line, therefore we do not draw any conclusions. The reason for this behavior is that x1 and x4 are both generated by and therefore are highly correlated.

Thus we have shown that we successfully retrieve the imposed dependence structure of (21) by interpreting each of the subplots in the described way. Channel x1 influences channels x2, x3, x5, x6, x8, x9, so do channels x4 and x7. This is illustrated in Fig. 3(b) where each influence relation is symbolized by an arrow.

4.2. ECoG data

We apply our methodology (see Section 3.1) to ictal invasive EEG (ECoG) data described in Section 3.3. We process a 4-s segment from the initial phase of a seizure in order to locate the seizure onset zone. Fig. 4 shows 6 out of the 24 processed channels.

The number of static factors is determined by a Scree plot as before in Section 4.1. In order to achieve an explained variance greater than 80% we choose q = 5.

The choice of the AR-model order for the application was challenging. The problem is that filtering (in the preprocessing step of the data) could affect the AR-model order (and the Granger causal analysis of the data), see Barnett and Seth (2011). The application of AIC and BIC criteria in a sliding data window revealed optimal AR-orders in the range from 4 to 40. In the rhythmic epochs of the data AR-model orders of 6 or 8 dominate. Hence, in accordance with the survey paper (Tseng et al., 1995), we choose the AR-model order for the Granger causal analysis p = 8. This chosen model order corresponds to a time lag of 62.5 ms.

Furthermore, we choose τ = 0.05 in order to discard points of the causality analysis which yield unreasonable results due to numerical problems caused by channel similarity.

In the application of our methodology to ECoG data the co-movement χ(t) from Eq. (9) represents the common movement of the data. This common movement is the synchronized epileptic activity (we are interested in) and is characterized by high amplitude wave forms. On a theoretical level η(t) is noise, but in the application it is simply the rest after the important parts of the data (common movement) have been removed. According to our key assumption that the causality structure of the latent variables reflects the causality structure of the data, no important causal information is found in these low amplitude residuals. This assumption holds in the case of the observed ECoG data, as we discuss in Section 5.1.

In analogy to the analysis of the signal model (21) in Section 4.1 we obtain a 24 × 24 matrix plot. Fig. 7 shows a 6 × 6 sub-matrix, corresponding to the 6 channels displayed in Fig. 4.

Fig. 7.

Results of the influence analysis of the ictal ECoG data from six selected channels (displayed in Fig. 4) in matrix plot form (submatrix of the full 24 × 24 matrix). Columns indicate the source channels and the rows the target channels. Compare Fig. 6.

Here we briefly want to discuss 4 subplots of Fig. 7 in detail:

Subplot (2, 3) describes the causality relations from B8 to A12. All points to the right of the determinant threshold are located below the dotted line, thus we say channel B8 influences channel A12.

In subplot (5, 3) all points located to the right of the determinant threshold are above the dotted line. Therefore B8 does not influence C5.

An interesting case occurs in subplot (3, 2). We have admissible points above and below the dotted line. In this case we refrain from any influence statement.

Finally in subplot (4, 2) all points are located to the left of the determinant threshold. We do not draw any conclusion in this case, as there are no admissible channel selections.

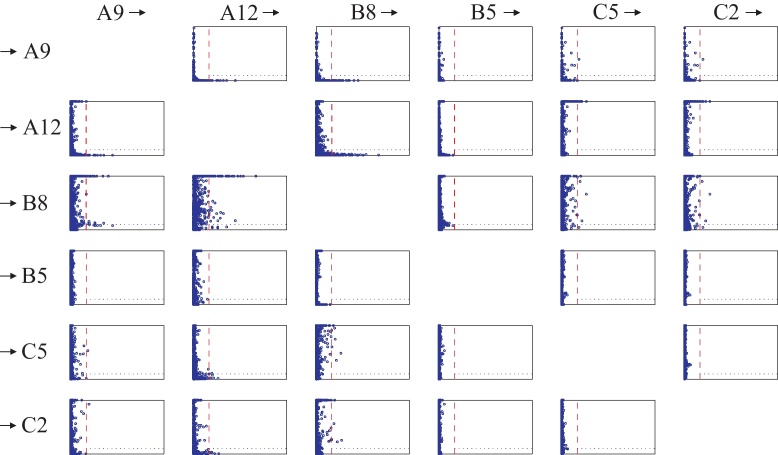

By interpreting each subplot in the 24 × 24 matrix in this way, we obtain all influence relations. In particular we are interested in the (source, target) channel pairs, where the source does influence the target channel. Fig. 8 shows a MRI scan of the patient's brain together with the electrode positions, the calculated influences are represented by arrows.

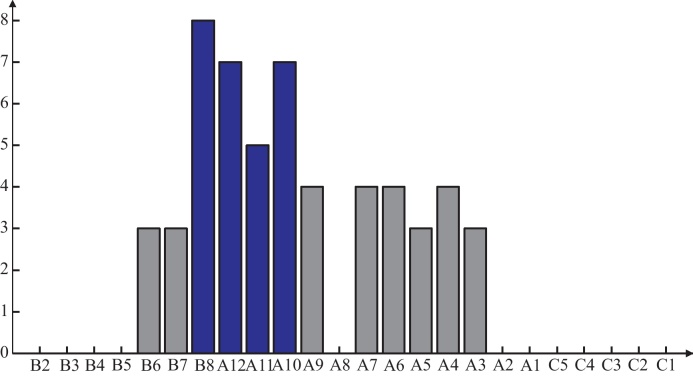

Channels B8, A12, A11 and A10 have the highest number of outgoing arrows, see Fig. 9 for a quantification of the out-degree per channel. This observation suggests that the seizure onset zone comprises these four electrodes, which is in good accordance with the visual analysis of the clinicians. In Section 5.2 we will discuss the neurophysiological aspects of this result.

Fig. 9.

Results of the influence analysis of the ictal ECoG data. Histogram of the out-degree of the electrodes represented in Fig. 8. Electrodes with the highest number of departing arrows are considered to represent the seizure onset zone (B8, A12, A11 and A10).

5. Discussion

In this paper we propose a procedure for deriving influence relations in high-dimensional and co-moving time series using PCA and Granger causality. In this section we discuss various aspects of our approach. We start with a discussion of the methodology proposed in Section 3.1, followed by a discussion of its application to simulated data and ECoG recordings.

5.1. Methodology

A key assumption of this paper is that the latent variables reflect the causality structure of the observations. In other words, that we can infer the dependencies between the channels from the latent variables, and that the noise is assumed not to contain any causality information. Although this is a strong assumption, it seems reasonable to us: this assumption is very similar to the one that the causal dependencies are reflected by distinct, high-amplitude wave forms in the signal, e.g. high amplitudes in ictal ECoG recordings. We believe that in particular in neurophysiological applications this is meaningful, as we expect these high-amplitude oscillations to carry substantial information about the causality structure of the generating cortical mechanisms.

In our approach we investigate all dependencies in all q-dimensional subsystems corresponding to the latent variables. By the application of the PCA we perform this analysis in a computationally efficient way, as we only have to compute one PCA and estimate one single AR-model. Of course it would also be possible to refrain from the usage of factor models. In this case one would fit an AR-model for each q-dimensional sub-process of the observations, which would result in a higher computational effort.

In contrast, the proposed factor model-based methodology yields a simple mathematical method for the causal analysis of the whole multivariate system. Another advantage of our method lies in the simple measure for the channel similarity of a channel selection I, , which allows for a straightforward comparison for different channel selections.

As mentioned in Section 3.1, our methodology consists of three steps: PCA, Granger causality analysis for fixed channel selection I and derivation of an influence statement. This modular design allows for an easy adaptation of each single step, i.e. alternative methods could be used in each step independently of the others.

First, the usage of sparse PCA would enforce additional zeros in the loading matrix Λ. Thurstone (1947) suggested five criteria for a simple structure and (d’Aspremont et al., 2007) gave a direct formulation for sparse PCA.

Second, here we use two central indicators in the Granger causality analysis for a fixed channel selection: as a measure of channel similarity (as mentioned above) and the p-value of an F-test as an indicator for Granger causality. We employ the latter due to its well-established theory. Note that in neuroscience literature various other directed dependency measures are used. Prominent ones include the linear measure of conditional dependence introduced by Geweke (1984), the Partial Directed Coherence (PDC) introduced by Baccala and Sameshima (2001), its numerous modifications and the Directed Transfer Function (DTF) proposed by Kaminski and Blinowska (1991). Compare Flamm et al. (2012) for an overview and a discussion of these measures with regard to Granger causality.

Other measures for the channel similarity would also be conceivable, e.g. the determinant of the covariance matrix of the errors in (16). However, we note that revealed good numerical properties.

Third, in this paper we propose a workable rule for the derivation of influence statements: If χi → χj|χI for all admissible I, we say that xi influences xj. One could imagine other rules depending on specific applications. For example only the channel selection with the largest could be taken into account for the influence statement. Another possible rule for influence statements might be based on the comparison of the number of points above and below the dotted line, e.g. the majority or a certain percentage.

A naturally arising question is whether and to which extent our definition of influence is meaningful. In our opinion it is a workable procedure for causality analysis in high-dimensional co-moving systems: Intuitively one expects a certain kind of dependence if χi is causal for χj for all (admissible) channel selections.

A potential weakness of our definition of influence is the fact that in practical applications one is often confronted with the case where no influence statement can be inferred. Compare subplot (3, 2) in Fig. 7, where causality as well as non-causality relations are symbolized. In such cases we recommend a more precise investigation which particular channel selections yield causality and which do not. If, in applications, the conditioning on channels of a specific region yields non-causality between channels i and j, but the conditioning on all other regions indicates causality, further investigation could be performed to explain this. Due to the existence of such undecidable cases we avoid the term causality and refer to the derived dependence statement as influence.

We want to conclude this first part of the discussion with a side remark.

The problem of high-dimensional co-moving data often occurs in practical applications. We propose a methodology connecting Granger causal analysis and factor models. Other ideas in order to cope with the co-movement include the analysis of manually selected subsystems (where the number of observations equals the number of driving components) or the causal analysis of so-called extracted atoms, which represent condensed information of the system, see Eichler (2005).

5.2. Application

Our methodology correctly identifies the dependence structure of the signal model (21) (see Section 3.2), as we have discussed in Section 4.1. During this analysis we encountered the challenges discussed in the previous section.

The determination of q, i.e. the dimension of the static (and the dynamic) factors, is very important for the simulated data as well as the ECoG recordings and potentially has great influence on the analysis. In both applications we chose q based on Scree plots in a reasonable way. The assumption that the dimension of the dynamic and the static factors match is very strong. If the dimension of the dynamic factors is lower than the one of the static factors, the AR modeling of the static factors (11) does not hold any longer. The resulting model class is richer but the proposed approach would have to be generalized.

A major problem of the presented causal analysis of the ECoG data is the stationarity. As can be seen in Fig. 4 the data do not seem to be stationary. During the main phase of the epileptic seizure the channels show distinct rhythmic behavior, which is stationary in nature. However, we are interested in the beginning of the epileptic seizure where the rhythmic activity starts to spread. Due to this evolution our period of interest is non-stationary.

There are two main approaches to cope with the problem of causal analysis of non-stationary data: the first is to use non-linear methods, see e.g. Marinazzo et al. (2011), the second is to employ the shortest possible time window for the analysis. We focus on the second approach and use a short time window:

The segment length of the analyzed data is bounded below with 4 s (at a sampling rate of 128 Hz) in order to yield a reasonable result in the causal analysis. This is the lowest possible reasonable window length for the used methods (first PCA extraction of 5 important components and second AR-modeling with order p = 8) due to parameter estimation, compare Section 2.1. Reasonable in this sense means stability of the results: a slight temporal shift of the analyzed data window will only cause small changes in the causal analysis; for shorter segments the window shift will cause significant changes in the causal analysis.

The application of our methodology to ictal ECoG data shows promising results. We successfully localize the seizure onset zone of the analyzed patient by identifying the zone with the highest number of outgoing arrows. In this manner we define the area comprising the electrodes B8, A12, A11 and A10 as the seizure onset zone, compare the MRI scan in Fig. 8 and the out-degree histogram in Fig. 9. This result correlates well with the visual inspection of the raw ECoG data by clinicians. They mark the beginning of the epileptic activity on each channel, and by the temporal delay between channels the propagation and seizure onset zone are determined. Table 1 summarizes the findings of three clinical experts who independently marked the electrodes initially involved in the epileptic activity. For each of the three investigations the electrodes identified by our methodology are comprised in the set of initial and follow-up electrodes. Electrodes B8, A12 and A11 are specified as initial in two out of three cases and as follow-up in the third case. Inversively, electrode A10 is indicated as initial in one case and as follow-up in two cases.

Table 1.

Onset zone and initial propagation of the analyzed seizure according to the visual inspection by clinicians.

| Investigator | Initial electrodes | Close follow-up |

|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | B8 | A10, A11, A12 |

| Expert 2 | A11, A12, B8 | A9, A10, B7 |

| Expert 3 | A10, A11, A12 | B8 |

The visual analysis investigates each channel on its own and then compares all channels. In contrast our proposed methodology analyzes the whole multivariate set of channels at once. So the two underlying ideas are different, and therefore it is remarkable that the results correlate so well.

In our opinion the reason for this good correlation between our results and the clinical findings is the following:

In case of focal epilepsy, the pathological synchronous activity (characterizing the epileptic seizure) starts at a circumscribed brain area. From this seizure onset zone ictal activity spreads to its immediate vicinity recruiting more and more parts of the neural network. This leads to distinct co-movement of the observations. One could imagine a “focus” located in the seizure onset zone driving the surrounding channels by imposing its oscillatory frequency in the course of the recruiting process. This could be interpreted as a kind of information transfer or causal interaction: the electrodes in the focus influence the behavior of the surrounding electrodes in the initial phase of the seizure.

Therefore we expect to obtain indications for the seizure onset zone by applying a Granger-causal analysis to factor models within the initial seconds of the seizure. We think that the aforementioned results strengthen this hypothesis. However, for a confirmation of this hypothesis the application of the proposed methodology to a broader data basis is essential.

In the course of this recruiting process we obviously expect feedback mechanisms between the channels (besides unidirectional dependence). This can be observed in Fig. 8, consider e.g. channels A9 ↔ A10, A10 ↔ A12 and B6 ↔ A12. However, in the seizure onset zone the departing arrows predominate, i.e. we have channels with a high out-degree. This situation is reflected in the out-degree histogram in Fig. 9. Channels with the highest out-degrees coincide with the seizure onset zone, and with increasing distance to the seizure onset zone the respective out-degree decreases. Channel A8 with an out-degree of zero is an exception, as we cannot infer any influence statement for this source channel (only non-admissible channel selections for all target channels).

Finally we want to address a general problem of EEG/ECoG analysis: coverage, i.e. cortical activity is only measured at certain points. Usually the focus of a seizure is located in deeper brain regions or is not directly covered by an electrode. Therefore, the presented methodology as well as the visual analysis only detect a circumscribed area where the epileptic activity is noticed first.

In case of incomplete coverage our algorithm would detect the area which influences the other areas to the greatest extent. However, this is not necessarily the seizure onset zone.

Concluding we think that our methodology might have the potential to assist clinicians in the presurgical evaluation by objectivating their visual ECoG examination (e.g. as an Add-on to clinical recording software).

6. Conclusion

In this paper we propose a causal analysis of high-dimensional co-moving data, connecting the topics of Granger causality and factor models. The application of Granger causality to factor models is not straightforward, and we propose a natural extension termed influence. The latter allows for an investigation of the dependence structure in certain cases.

This methodology might often allow an insight into the dependence structure of highly correlated data in neuroscience such as EEG.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (Grants P22961 and L630).

We wish to thank Prof. Czech from the Vienna General Hospital, University Clinic for Neurosurgery, for providing the MR image with the subdural electrode strip positions.

We are grateful to Sandra Zeckl from the Hospital Hietzing, Neurological Center Rosenhügel, for the visual inspection of the ECoG data.

Furthermore, we want to thank our colleague Elisabeth Felsenstein for helpful discussions on factor models.

Footnotes

In this context A < B means that B − A is a positive definite matrix.

In this context # denotes the number of elements in a set.

Simulation is done using the function arsim of the Matlab® package arfit, described in Schneider and Neumaier (2001).

References

- Anderson B., Deistler M. Identifiability in dynamic errors-in-variables models. J Time Ser Anal. 1984;5:1–13. doi: 10.1111/jtsa.12430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astolfi L., Cincotti F., Babiloni C., Carducci F., Basilisco A., Rossini P. Estimation of the cortical connectivity by high-resolution EEG and structural equation modelling: simulations and application to fingertapping data. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52(5):757–768. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.845371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccala L., Sameshima K. Partial directed coherence: a new concept in neural structure determination. Biol Cybern. 2001;84:463–474. doi: 10.1007/PL00007990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett L., Seth A. Behaviour of Granger causality under filtering: theoretical invariance and practical application. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;201:404–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler S., Seth K. Wiener–Granger causality: a well established methodology. Neuroimage. 2011;58(2):323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell P., Davis R. Springer; New York: 1991. Time series: theory and methods. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy M., Brown P. Hidden Markov based autoregressive analysis of stationary and nonstationary electrophysiological signals for functional coupling studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;116:35–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell R.B. The Scree test for the number of factors. Multivar Behav Res. 1966;1(2):245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Aspremont A., Ghaoui L.E., Jordan M., Lanckriet G. A direct formulation for sparse PCA using semidefinite programming. SIAM Rev. 2007;49(3):434–448. [Google Scholar]

- Deistler M., Anderson B., Filler A., Zinner C., Chen W. Generalized dynamic factor models – an approach via singular autoregressions. Eur J Contr. 2010;16(3):211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Deistler M., Zinner C. Modelling high-dimensional time series by generalized linear dynamic factor models: an introductory survey. Commun Inf Syst. 2007;7:153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Dhamala M., Rangarajan G., Ding M. Analyzing information flow in brain networks with nonparametric Granger causality. Neuroimage. 2008;41:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler M. A graphical approach for evaluating effective connectivity in neural systems. Philos Trans Roy Soc B. 2005;360:953–967. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler M. Graphical modeling of dynamic relationships in multivariate time series. In: Schelter B., Winterhalder M., Timmer J., editors. Handbook of time series analysis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. pp. 335–372. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler M. Granger causality and path diagrams for multivariate time series. J Econom. 2007;137:334–353. [Google Scholar]

- Flamm C., Kalliauer U., Deistler M., Waser M., Graef A. Graphs for dependence and causality in multivariate time series. In: Wang L., Garnier H., editors. System identification, environmental modelling, and control system design. Springer; London: 2012. pp. 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Formisano E., Martino F.D., Valente G. Multivariate analysis of fMRI time series: classification and regression of brain responses using machine learning. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:921–934. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates K.M., Molenaar P.C., Hillary F.G., Ram N., Rovine M.J. Automatic search for fMRI connectivity mapping: an alternative to Granger causality testing using formal equivalences among SEM path modeling, VAR, and unified SEM. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1118–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geweke J. Measurement of linear dependence and feedback between multiple time series. J Am Stat Assoc. 1982;77(378):304–313. [Google Scholar]

- Geweke J. Measurement of conditional linear dependence and feedback between multiple time series. J Am Stat Assoc. 1984;79:907–915. [Google Scholar]

- Granger C. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and crossspectral methods. Econometrica. 1969;37:424–438. [Google Scholar]

- Götz-Trabert K., Hauck C., Wagner K., Fauser S., Schulze-Bonhage A. Spread of ictal activity in focal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49(9):1594–1601. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S., Seth A., Kendrick K., Zhou C., Feng J. Partial granger causality – eliminating exogenous inputs and latent variables. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;172:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan E. Wiley; New York: 1970. Multiple time series. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan E., Deistler M. SIAM; 2012. The statistical theory of linear systems. Classics in applied mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Hirtz D., Thurman D., Gwinn-Hardy K., Mohamed M., Chaudhuri A., Zalutsky R. How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology. 2007;68:326–337. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252807.38124.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J Educ Psychol. 1933;26(6):417–441. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J. John Wiley and Sons; 2004. A user's guide to principal components. [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen S., Roberts C., Gracely E., Dlugos D., Sperling M. Focal seizure propagation in the intracranial EEG. Epilepsy Res. 2011;93:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski M., Blinowska K. A new method of the description of the information flow in the brain structures. Biol Cybern. 1991;65:203–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00198091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Hwan C., Jung Y.J., Kim E.Y., Lee S.K., Chung C.K. Localization and propagation analysis of ictal source rhythm by electrocorticography. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W., Mantini D., Zhang Z., Pan Z., Ding J., Gong Q. Evaluating the effective connectivity of resting state networks using conditional granger causality. Biol Cybern. 2010;102:57–69. doi: 10.1007/s00422-009-0350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütkepohl H. Springer; Berlin: 2007. New introduction to multiple time series analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Marinazzo D., Liao W., Chen H., Stramaglia S. Non-linear connectivity by Granger causality. Neuroimage. 2011;58:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller E., Schack B., Arnold M., Witte H. Instantaneous multivariate EEG coherence analysis by means of adaptive high-dimensional autoregressive models. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;105:143–158. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar P.C. A dynamic factor model for the analysis of multivariate timeseries. Psychometrika. 1985;50(2):181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar P.C., Nesselroade J.R. Rotation in the dynamic factor modelling of multivariate stationary time series. Psychometrika. 2001;66(1):99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J. Cambridge University Press; 2000. Causality. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson K. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Philos Mag. 1901;2(6):559–572. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda E., Quiroga R.Q., Bhattacharya J. Nonlinear multivariate analysis of neurophysiological signals. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:1–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondal-Sordo M., Diosy D., Tellez-Zenteno J.F., Sahjpaul R., Wiebe S. Usefulness of intracranial EEG in the decision process for epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Res. 2007;74:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanov Y. Holden Day; San Francisco: 1967. Stationary random processes. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T., Neumaier A. Algorithm 808: Arfit, a matlab package for the estimation of parameters and eigenmodes of multivariate autoregressive models. ACM Trans Math Softw. 2001;27(1):58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schuele S., Lüders H. Intractable epilepsy: management and therapeutic alternatives. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(6):514–524. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70108-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth A. A matlab toolbox for granger causal connectivity analysis. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;186:262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims C. Money, income, and causality. Am Econ Rev. 1972;62(4):540–552. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerlade L., Thiel M., Platt B., Planod A., Riedel G., Grebogic C. Inference of Granger causal time-dependent influences in noisy multivariate time series. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;203:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone L. University of Chicago Press; Chiacago: 1947. Multiple factor analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng S.Y., Chen R.C., Chong F.C., Kuo T.S. Evaluation of parametric methods in EEG signal analysis. Med Eng Phys. 1995;17:71–78. doi: 10.1016/1350-4533(95)90380-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener N. The theory of prediction. Mod Math Eng. 1956 (Series 1, Chapter 8) [Google Scholar]

- Wiener N., Masani P. The prediction theory of multivariate stochastic processes II. The linear predictor. Acta Math. 1957;99(1):93–137. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke C., Ding L., He B. Estimation of time-varying connectivity patterns through the use of an adaptive directed transfer function. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2008;55(11):2557–2564. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2008.919885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]