Abstract

Background:

Malaria is a public health problem globally especially in the Sub-Saharan Africa and among the under five children and pregnant women and is associated with a lot of maternal and foetal complications.

Objective:

The study was on the effect of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy on the prevalence of malaria in pregnancy and the outcome of pregnancy.

Materials and Methods:

In a descriptive cross-sectional study, a semi-structured questionnaire was administered to women admitted in Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital labour ward, Ado-Ekiti. About 4,200 women participated in the study and the inclusion criteria were women who were booked in the hospital, attended at least four antenatal clinic visits, and consented to the study while the exclusion criteria were those who didn't book in the hospital and failed to give their consent.

Results:

The study revealed that about 75% of the pregnant women studied had access to intermittent preventive treatment of malaria. Among the women attending the antenatal clinic that received sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), about 78% of them took two doses of SP. The prevalence of clinical malaria was statistically higher in women who did not receive intermittent preventive treatment with SP during pregnancy (44.7% vs. 31.3%, P = 0.0001) and among women who had one dose of the drug instead of two doses (40.0% vs. 28.7%, P = 0.0001). There was no statistical significant difference in the mean age in years (31.53 ± 5.238 vs. 31.07 ± 4.751, P = 0.09 and the gestational age at delivery (38.76 ± 1.784 vs. 38.85 ± 1.459, P = 0.122) between the women who did not receive SP and those who had it. There was a statistical significant difference in the outcome of pregnancy among women who had Intermittent Preventive Treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) and those who did not viz.-a-viz. in the duration of labor (8.6 ± 1.491 vs. 8.7 ± 1.634, P = 0.011) and the birth weight of the babies (3.138 ± 0.402 vs. 3.263 ± 0.398, P = 0.0001).

Conclusion:

SP is an effective malarial prophylaxis in pregnancy.

Keywords: Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria, outcome of pregnancy, sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is an important public health problem globally and especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. This is due to climatic factors, poor environmental sanitation and cultural habits in this region, which provide conducive atmosphere that allows transmission of the parasite throughout the year.1 It has been estimated that about 90% of the annual 500 million cases of malaria occur in the Sub-Saharan Africa with 80% of the 1.5-3.0 million annual deaths due to malaria.1 Most studies from Sub-Saharan Africa showed that about 25 million pregnant women are at risk of malaria infection every year2 while it is estimated that 40% of the world's pregnant women are exposed to malaria infection during pregnancy.3

In Nigeria, at least 50% of the population has malaria infection annually with under-five children and pregnant women at greater risk of the debilitating effects of the infection.3 Malaria accounts for 30% of childhood mortality and 11% of maternal deaths in Nigeria.1 In many African countries, malaria is holo-endemic and non-pregnant female adults have a significant level of immunity against malaria. However, during pregnancy, these women experience a considerable decline in their levels of immunity to malaria4 and several studies have reported that 1st and 2nd pregnancies are associated with a higher prevalence of malaria in the first half of pregnancy in women living in endemic malarious areas.5,6,7

Malaria is an important cause of maternal anaemia, intrauterine growth retardation, intrauterine death, still birth, premature delivery, low birth weight (LBW), perinatal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and post-partum morbidity.4,8,9 In Sub-Saharan Africa, poor nutrition, micronutrient imbalances (especially vitamin A, Zinc, Iron and Folate), Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection, poverty and limited access to effective primary healthcare and emergency obstetric services exacerbate the impact of malaria in pregnancy.8 Women are particular at risk of cerebral malaria, hypoglycaemia, pulmonary oedema and severe haemolytic anaemia. Foetal and perinatal loss has been documented to be as high as 60-70% in non-immune women with malaria.3 These complications are commoner in primigravidae than multigravidae.3,4

The renewed interest in protecting and promoting both maternal and child health has led to the three pronged approach of tackling malaria in pregnancy, namely: Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria using an effective antimalarial drug to address the heavy burden of asymptomatic infections among pregnant women living in areas of moderate to high transmission of Plasmodium falciparum; the use of insecticide treated nets by all pregnant women and effective case management of malaria illness and anaemia.10 Intermittent Preventive Treatment of pregnancy (IPTp) involves the administration of therapeutic doses of an antimalarial drug to a population at risk whether or not they are known to be infected, at specific point intervals usually with the aim of reducing morbidity and mortality.11

In 2002, World Health Organization (WHO) developed a strategic framework for the control of malaria during pregnancy in Africa. The document recommends that pregnant women receive at least two doses of Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine (SP) as intermittent preventive treatment during the second and third trimesters during the routine antenatal visit while chemoprophylaxis is no longer recommended for a no of reasons including the difficulty in the delivery of this strategy, poor adherence with weekly drug dosing and rising rate of resistance to most of the chemoprophylaxis regimens including chloroquine.12 Recently, IPT has been shown to be better than malarial chemoprophylaxis and has replaced it.3,4,11

The objective of this study was to determine the influence of the use of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria with SP during pregnancy on the prevalence of malaria in pregnancy and the outcome of pregnancy. The outcome of this would help to strengthen the use of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria by the pregnant women during routine antenatal care in this centre being a new and emerging teaching hospital. This study has also not being carried out in this centre before.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One of the guidelines in the routine management of pregnant women in our centre is to send blood sample of every pregnant woman with clinical diagnosis of malaria to the laboratory for examination for malaria parasite.

The National IPTp coverage is about 16.6% in the urban areas and 8.5% in the rural areas while the coverage is 14% for the south-west region.13 IPT of malaria with SP (500 mg Sulphadoxine and 25 mg Pyrimethamine) was given in the second and third trimester by direct observed therapy (DOT) under the supervision of nurses at the antenatal clinic and usually documented in the case record along with the number of doses the pregnant women had taken. Pregnant women on IPT of malaria with SP are usually instructed to return to the clinic in case of any febrile illness.

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out at the maternity department of the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, one of the referral centres in south western Nigeria.

Forty consecutive pregnant women at term, who gave an informed consent form or thumb-printing, were recruited into the study on each clinic day during the period of study. Data were collected using semi-structured questionnaire.

The social class of each woman was determined by adding the scores from the husband's occupation and woman's level of education as described by Olusanya et al.14

The data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 15. The association between discrete variables was tested using Chi-square test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. The main outcome variable is the birth weight of the baby.

RESULTS

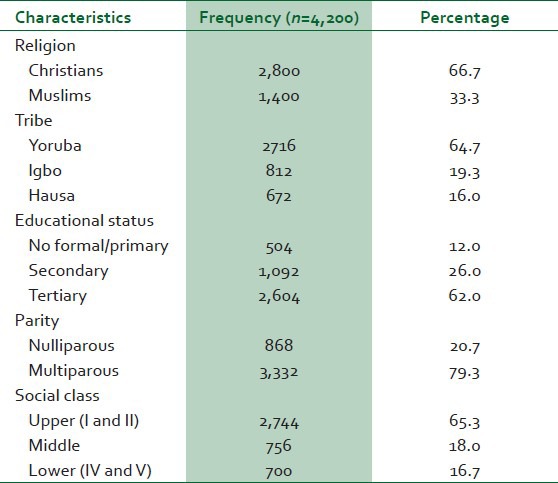

About 4,200 women recruited for the study participated by filling the questionnaires giving a response rate of 100%. Table 1 showed that 3,136 (74.7%) pregnant women received IPTp while 1064 (25.3%) did not receive this. Out of the 3,136 women that received the IPTp drug, 700 (22.3%) of them received one dose of IPTp while 2436 (77.7%) received two doses of the IPTp drug. Majority (76.9%) of the women that received IPTp drug were multiparous while 23.1% of them were nulliparous. The age range of the respondents was between 19-41 years with a mean age of 31.19 ± 4.88 years, the parity of the women was para 0-4 with a mean parity of 1.61 ± 1.09, their gestational age at booking ranged from 9-34 weeks with a mean gestational age of 21.13 ± 4.56 weeks and the gestational at presentation in labour was between 32-43 weeks with the age at 38.83 ± 1.54. The duration of labour was between 5-12 hours with a mean duration of 8.63 ± 1.53 and the birth weight of their babies ranged from 2.2-4.4 with a mean birth weight of 3.27 ± 0.40. Other socio-demographic variables are as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the pregnant women involved in the study

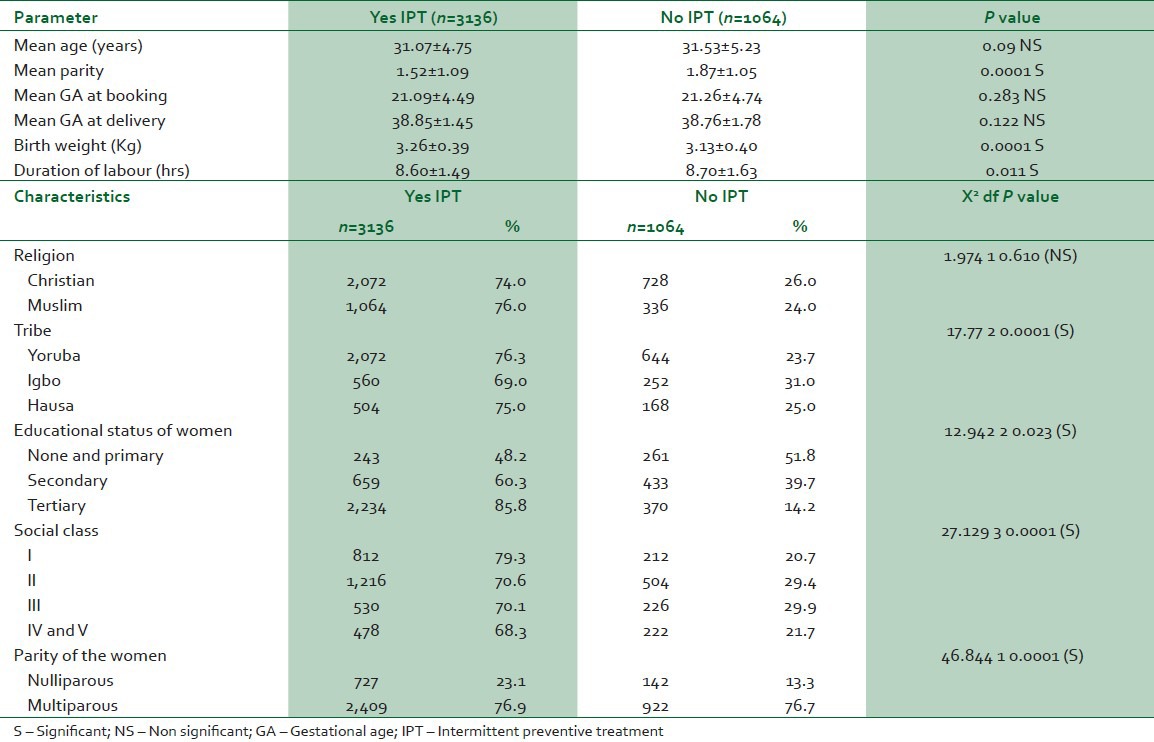

Table 2 showed the comparison of the characteristics between the women who received IPTp and the women who did not receive the treatment.

Table 2.

The comparison of demographic characteristics and obstetric outcome between pregnant women who used IPTp and those who did not use IPTp

There was no significant difference in the mean age, mean gestational age at booking and delivery between the women that used IPTp drug and those who didn't use but there was significant difference in the mean parity, birth weight and duration of labour of the women.

More women who are multiparous, Yoruba and with higher educational status and social class were associated with increased use of IPTp during pregnancy in this study with P value of 0.001, 0.023 and 0.001, respectively.

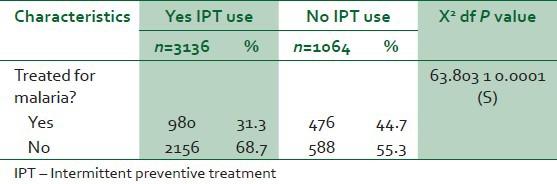

Table 3 showed the prevalence of malaria in pregnancy among the women who had IPTp and those who did not have IPTp.

Table 3.

The prevalence of malaria in pregnancy among women who had IPTp and those who did not have IPTp

There was a higher prevalence of malaria in pregnancy among women who did not receive intermittent preventive treatment of malaria compared to women who used it and P = 0.0001.

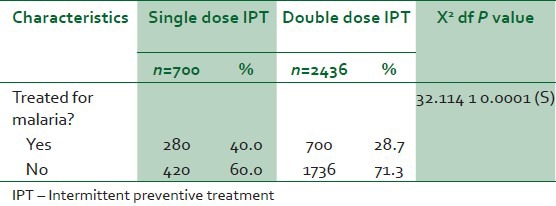

Table 4 showed the prevalence of malaria in pregnancy among the women who had a single dose of IPTp and those women who had double dose of IPTp.

Table 4.

The prevalence of malaria in pregnancy among women who had single dose of IPTp and those who had double dose of IPTp

Among the women who used IPTp and had malaria in pregnancy, the prevalence of malaria was higher in those who had a single dose of the drug compared to those who had two doses with P = 0.0001.

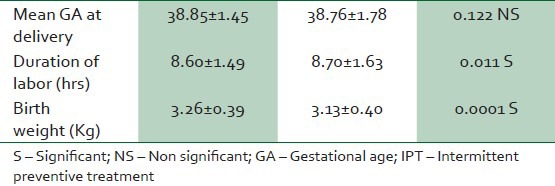

Table 5 showed the outcome of pregnancy among the women who had IPTp and those who did not have during pregnancy.

Table 5.

The outcome of pregnancy among women who had IPTp and those who did not have IPTp

The mean gestational age at presentation in labour were comparable between the women who received IPTp and those women who did not receive even though the women who received IPTp presented at a higher gestational age in labour, however this was not significant, P value = 0.122

The duration of labour was higher in women who did not use IPTp and the birth weight of babies was also lower in them, P values are 0.011 and 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

The present study revealed that more than two-thirds of the pregnant women studied had access to IPTp of malaria and took the recommended two doses of SP. The high coverage recorded in this study is similar to that reported in previous studies done among pregnant women in Beua and Ibadan by Takem et al.,12 and Falade et al.,15 respectively, but higher than that in previous hospital based studies among pregnant women in Tanzania and Kenya, respectively, by Nganda et al.,16 and Van Ejik et al.,17 This higher coverage was due to the fact that the study was done in the antenatal clinic where the drug was being administered by direct observed therapy. It also showed that the program implementation is improving gradually over time.

There was a low prevalence of clinical malaria among women who used intermittent preventive treatment compared to those who did not use it and this was statistically significant. Even among the women that took the drug, those that took two doses of SP experienced a lower prevalence of clinical malaria compared to those who took one dose of the drug. This demonstrates the efficacy of SP in improving the outcome of pregnancy. This is comparable to reports by Takem et al.,12 and Mbonye et al.,18 who reported a reduction in the prevalence of peripheral parasitaemia and parasite density among women of all parities.

The increased use of intermittent preventive treatment with increasing level of education found in this study is not surprising since those with higher educational status are more health conscious and can easily apply health education programs to their daily living. This finding is consistent with report in previous studies by Takem et al.,12 and Marchant et al.,19 Women in the higher social class and parity were also associated with greater tendency to use the intermittent preventive treatment drug. This is because women in that class tend to know and appreciate the benefits of the preventive measures against malaria in pregnancy like the use of insecticide treated nets and intermittent preventive treatment amongst others. Women who are multiparous comply more with antenatal instructions including the use of prescribed drugs compared to women who are primigravidae women since they would have discovered the benefits associated with these drugs in their previous pregnancies. This is similar to finding earlier reported by Marchant et al.,19 but not consistent with that of Takem et al.,12 who reported that the effect of socio-economic status on the use of IPTp was close to null in their studies.

Women who received intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy had better outcome of their pregnancy. Low birth weight and prematurity are the greatest risk factors for neonatal mortality and a major contribution to infant mortality.15 In this study, babies born to mothers who received intermittent preventive treatment of SP on the average weighed more than babies born to women who did not received the drug. They also had shorter duration of labour which reduced the length of time the babies had to be exposed to the stress of labour. The birth weight of babies in this study may not only be attributed to the low prevalence of malaria in pregnancy in them since other factors such as socio-economic level may also play a role but this was statistically significant. This is similar to reports from Falade et al.,15 Mbonye et al.,18 and Shulman et al.20

High educational status and gravidity are associated with the use of IPTp among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in this study and that use of SP as intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy has been accepted by women as a malaria control strategy in pregnancy. However, much work still need to be done to improve the uptake of the drug especially among the pregnant women who are of low educational status and low parity, who incidentally had a higher prevalence of clinical malaria in this study and to ensure that all pregnant women received the recommended two doses of the intermittent preventive treatment of SP during pregnancy.

In conclusion, the results from the study also showed that IPTp of malaria during pregnancy with SP is beneficial in improving pregnancy outcome and is widely used by the pregnant women attending antenatal clinic though not optimal. Therefore, health education programs for pregnant women in this area should be intensified in women of low educational status and low parity to improve the uptake among them. Direct observation therapy system (DOTS) can also be employed in which the pregnant women would be asked to take the drug under the observation of the nurses in the antenatal clinic. This would help in improving the compliance rate since some women may get the drug and not use it. Government should be encouraged to make the drug available in the various antenatal clinics to be distributed to pregnant women free or at subsidized rate as part of efforts at improving maternal and child health to achieve the millennium development goals (MDGS) four and five.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to appreciate all the pregnant women who voluntary took part in the study, the nurses in the antenatal clinic and the house officers and the registrars who assisted in administering the questionnaires.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asa OO, Onayande AA, Fatusi AO, Ijadunola KT, Abiona TC. Efficacy of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in preventing anaemia in pregnancy among Nigeria women. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:692–8. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, McGready R, Asamoa K, Brabin B, et al. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shulum CE, Dorman EK. Importance and prevention of malaria in pregnancy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:30–5. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nwonwu EU, Ibekwe PC, Ugwu JI, Obarezi HC, Nwangbara OC. Prevalence of malaria parasitaemia and malaria related anaemia among pregnant women in Abakaliki, south-east Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12:182–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okonofua FE. Malaria in pregnancy in Africa. A review. Niger J Med. 1991:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulman CE, Dorman EK. Intermittent sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine to prevent severe anaemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:632–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okwu OO. The status of malaria among pregnant women: A study in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2003;7:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valley A, Valley L, Changalucha J, Greenwood B, Chandramohan D. Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy in Africa: What's new, what's needed? Malar J. 2007;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyatt TK, Snow RW. The epidemiology and burden of Plasmodium falciparum related anemia among pregnant women in sub-saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:36–44. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyibo WA, Agomo CA. Scaling up of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine: Prospects and challenges. Matern Child Health J. 2010;4:12–5. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman RD, Moran AC, Kayenta K, Benga-De E, Yameogo M, Gaye O, et al. Prevention of malaria during pregnancy in west-Africa. Policy change and the power of sub-regional action. Eur J Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:462–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takem EN, Achidi EA, Ndumbe PM. Use of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria by pregnant women in Beua, Cameroon. Acta Trop. 2009;112:54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nigeria demographic and health survey 2008. Abuja, Nigeria: National Population Commission and ICF Macro; 2009. National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF Macro. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olusanya O, Okpere E, Ezimokhai M. The importance of social class in voluntary fertility control in a developing country. West Afr J Med. 1985;4:205–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falade CO, Yusuf BO, Fadero IF, Mokoulu OA, Hamer DA, Salako LA. Intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine is effective in preventing maternal and placental malaria in Ibadan, south-west Nigeria. Malar J. 2007;6:88. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nganda RY, Drakeley C, Reyburn, Marchant T. Knowledge of malaria influences the use of insecticide treated nets but not intermittent preventive treatment of malaria by pregnant women in Tanzania. Malar J. 2004;3:42. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Ejik AM, Ayisi JG, ter Kuile FO, Otieno JO, Misore AO, Odondi JO, et al. Effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for control of malaria in pregnancy in western Kenya: A hospital based study. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:351–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mbonye AK, Bygbjerg IB, Magnussen P. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: A community based delivery-system and its effects on parasitaemia, anaemia and low birth weight in Uganda. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;2:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchant T, Nathan R, Jones C, Mponda H, Bruce J, Sedekia Y, et al. Individual, facility and policy level influences on national coverage estimates for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in Tanzania. Malar J. 2008;7:260. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shulman CE, Marshall T, Dorman EK, Bulmer JN, Cutts E, Peshu N, et al. Malaria in pregnancy: Adverse effects on haemoglobin levels and birth weight in primigravidae and multigravidae. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:770–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]