Abstract

Background

Timeliness of care may contribute to racial disparities in breast cancer mortality. African American women experience greater treatment delay than White women in most, but not all studies. Understanding these disparities is challenging since many studies lack patient-reported data and use administrative data sources that collect limited types of information. We used interview and medical record data from the Carolina Breast Cancer Study (CBCS) to identify determinants of delay and assess whether disparities exist between White and African American women (n=601).

Methods

The CBCS is a population-based study of North Carolina women. We investigated the association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, healthcare access, clinical factors, and measures of emotional and functional well-being with treatment delay. The association of race and selected characteristics with delays of >30 days were assessed using logistic regression.

Results

Household size, losing a job due to one’s diagnosis, and immediate reconstruction were associated with delay in the overall population and among White women. Immediate reconstruction and treatment type were associated with delay among African American women. Racial disparities in treatment delay were not evident in the overall population. In the adjusted models, African American women experienced greater delay than White women for younger age groups: odds ratio (OR), 3.34; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.07–10.38 for ages 20–39, and OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 1.76–6.54 for ages 40–49.

Conclusions

Determinants of treatment delay vary by race. Racial disparities in treatment delay exist among women <50 years old.

Impact

Specific populations need to be targeted when identifying and addressing determinants of treatment delay.

Keywords: breast cancer, disparities, treatment delay, Carolina Breast Cancer Study

Introduction

African American women have a higher breast cancer mortality compared to White women, even after accounting for clinical and prognostic factors(1–4) and socioeconomic characteristics(5). Timeliness has been used as an indicator of quality of care (6, 7) and may contribute in part to these persistent disparities. African American women demonstrate greater delays in care than White women at multiple points along the treatment pathway from detection to medical consultation/diagnosis ("diagnostic delay")(7–12) and from diagnosis to the initiation of treatment (“treatment delay”)(7–9, 13–17). Although the majority of studies demonstrate that African American women are more likely than White women to experience treatment delay (8, 14, 15, 17–20), not all studies find differences between these groups (21–23).

The impact of socioeconomic characteristics has been heavily investigated, but does not fully explain racial disparities in timeliness of care. A study on Medicare beneficiaries found that African American women were more likely than White women to experience delays between initial consultation (a diagnostic imaging procedure or consultation for symptoms) and diagnosis, as well as between diagnosis and treatment(9). In a Washington, D.C. cohort, African American women were more likely than White women to experience delay between the identification of a suspicious finding and diagnostic resolution even among women with the same type of insurance coverage (private or government)(10). Even among low-income, uninsured women enrolled in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), African American women are more likely to experience diagnostic delay and treatment delay(7).

Limitations in the assessment of socioeconomic characteristics may affect the validity and interpretation of the results for many studies performed to date. First, detailed socioeconomic data is often unavailable in investigations with large study populations(24). Area-level data (e.g. census tracts, zip codes) are used as a proxy for individual-level income and education (8, 9, 15, 25–29). These measures may be unreliable when there is marked heterogeneity within the area being analyzed(30). Additionally, they may not adequately control for confounding since studies suggest that area-level and individual-level characteristics independently impact breast cancer outcomes(31, 32). Second, studies often combine persons with Medicare and Medicaid coverage into a single category (10, 13, 14). Results for this heterogeneous category are difficult to interpret, particularly given the marked distinctions in breast cancer outcomes for these groups(15, 16, 33).

Identifying additional determinants of treatment delay will improve our understanding of racial disparities and is critical for developing interventions and policy to ensure timely care. Investigations based solely on administrative, cancer registry, or medical record data are fairly limited in the types of information they collect and thus are less amenable to discovering novel determinants of delay(7, 28). The goals of this study were to identify determinants of breast cancer treatment delay and to determine whether disparities in treatment delay exist between White and African American women. We use data from a population-based study to assess the association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, indicators of healthcare access, clinical factors, and measures of emotional and functional well-being with treatment delay. By combining medical record and patient-reported data, we were able to assess several factors that are not typically evaluated in other investigations and to obtain individual-level socioeconomic data.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The Carolina Breast Cancer Study (CBCS) phase III is an ongoing population-based study of breast cancer in North Carolina. The design is similar to earlier phases (34, 35), except that it is a case-only study and has a larger recruitment area (44 counties). Eligible participants are 1) 20–74 years old, 2) North Carolina residents at the time of diagnosis, and 3) have incident, pathologically-confirmed invasive primary breast cancer. Women with a previous diagnosis of invasive breast cancer are excluded. A random sample of eligible women is selected from the following strata: 1) African Americans <50 years old, 2) African Americans ≥50 years old, 3) non-African Americans <50 years old, and 4) non-African Americans ≥50 years old. The sampling fractions are 100%, 60%, 40%, and 15%, respectively. At baseline participants are interviewed by a nurse, complete a quality-of-life questionnaire, and provide written consent for medical record requests.

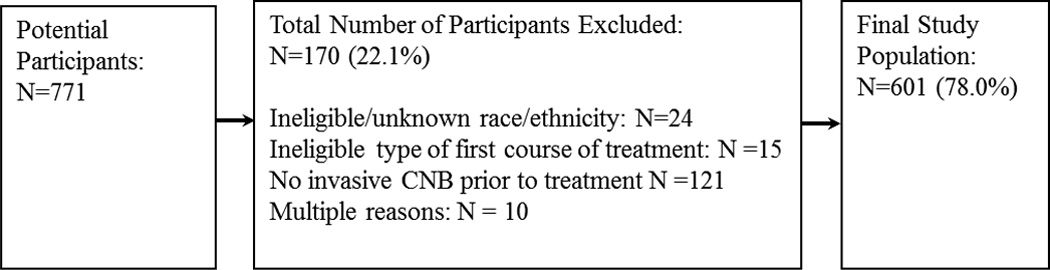

The present study uses abstracted medical record data and baseline nurse-administered interview and questionnaire data for women diagnosed between May 1, 2008 and January 29, 2010 (N=771). Participants were non-Hispanic White (“White”) or non-Hispanic African American (“African American”), received either surgery or neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or hormone therapy (“neoadjuvant therapy”) as their first course of treatment, had a known treatment date, and were diagnosed based on a core needle biopsy (CNB) prior to treatment. Participants who received pre-operative chemotherapy or hormonal therapy, or pre- and post-operative chemotherapy or hormone therapy were classified as having received neoadjuvant therapy as their first course of treatment. Hispanics and other racial groups were not analyzed due to small numbers (<3% for both). The final study population consisted of 601 women (Figure 1). This study was approved by the Office of Human Research Ethics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Figure 1.

Study inclusion criteria

CNB: core needle biopsy

Study variables

The main exposure, race, was obtained from self-report. We calculated treatment delay (main outcome) as the time in days between the date of the CNB used to diagnose invasive disease and the initiation of the first course of treatment. Treatment delay was dichotomized as >30 days (“delay”) or ≤30 days. Although this is a commonly used threshold (7, 9, 16, 17), the clinically relevant delay for first course of treatment is unknown. Additional details on the study variables are provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Statistical Analysis

The percentages shown in Tables 1–2 were weighted to obtain North Carolina population estimates (hereafter referred to as the “overall population”). The sample sizes shown in the tables are unweighted. The study design was accounted for in tests of associations between categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (95% CIs) for the association between each exposure and delay. Separate models were developed for each exposure (race and characteristics of delay identified in bivariate analyses) to account for the different sets of explanatory variables necessary to control for confounding (36, 37). Based on the literature, the following explanatory variables were included in the adjusted models to estimate the direct effect of race (White or African American) on delay: age (20–39, 40–49, 50–64, 65–74); income (≤$20,000, $20,000-$30,000, >$30,000); insurance coverage (private, Medicare, Medicaid, none); education (0–12 years, but no high school degree; high school graduate; some college; technical or business school; college degree or higher); lost a job due to one’s diagnosis (yes or no); American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) disease stage (I, IIA, IIB, III/IV); symptoms (yes or no); first treatment/reconstruction (breast conserving surgery [BCS], mastectomy without reconstruction, mastectomy with reconstruction, neoadjuvant therapy); and marital status (married, unmarried). We estimated the total effect of the following characteristics on delay: the number of people supported by the household income ("household size"; explanatory variables: age, race, marital status), losing a job due to one's diagnosis (explanatory variables: age, race, education), and first treatment/reconstruction (explanatory variables: age, race, education, income, insurance, education, disease stage). All variables were treated as categorical. An interaction term between age and race was included in all models to account for the study design. The study population rather than the overall population was used in the models to ensure a sufficient number of women of both races for each age group. All P values were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Table 1.

Population characteristics and breast cancer treatment delay

| Treatment Delay > 30 days |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | %b | Mean Treatment Delay (SE) [days] |

N | %b | Pc | |

| All | 601 | 100.0 | 28.0 (0.7) | 240 | 39.5 | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 314 | 79.0 | 27.3 (0.9) | 112 | 38.4 | 0.24 |

| African American | 287 | 21.0 | 30.4 (1.0) | 128 | 43.4 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 20–39 | 69 | 6.9 | 26.9 (1.4) | 27 | 36.5 | 0.22 |

| 40–49 | 221 | 21.3 | 27.0 (1.0) | 86 | 34.2 | |

| 50–64 | 214 | 46.8 | 29.3 (1.2) | 91 | 44.3 | |

| 65–74 | 97 | 25.1 | 26.6 (1.5) | 36 | 35.7 | |

| Education | ||||||

| 0–12 years, no high school degree | 65 | 10.1 | 27.9 (2.3) | 21 | 40.4 | 0.23 |

| High school graduate/GED | 119 | 19.9 | 28.1 (1.6) | 55 | 43.8 | |

| Technical or business school | 59 | 10.7 | 28.3 (2.4) | 24 | 42.5 | |

| Some college | 125 | 20.3 | 24.5 (1.5) | 42 | 27.8 | |

| College degree or higher | 233 | 39.0 | 29.6 (1.1) | 98 | 42.2 | |

| Income ($) | ||||||

| ≤20,000 | 124 | 20.1 | 28.6 (1.5) | 50 | 39.0 | 0.45 |

| 20,000 – 30,000 | 67 | 8.6 | 32.9 (2.0) | 38 | 54.6 | |

| 30,000 – 50,000 | 98 | 19.0 | 27.8 (1.8) | 38 | 37.2 | |

| 50,000 – 100,000 | 162 | 29.2 | 28.0 (1.5) | 62 | 39.6 | |

| >100,000 | 109 | 23.1 | 26.8 (1.6) | 40 | 36.0 | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 336 | 59.3 | 27.8 (0.9) | 135 | 41.0 | 0.72 |

| Formerly married | 191 | 33.1 | 28.1 (1.3) | 76 | 36.9 | |

| Never married | 74 | 7.6 | 28.9 (2.2) | 29 | 38.8 | |

| Household size | ||||||

| 1 | 151 | 28.0 | 27.4 (1.5) | 51 | 35.2 | 0.011 |

| 2 | 212 | 42.6 | 29.3 (1.1) | 102 | 47.3 | |

| 3 | 103 | 12.4 | 28.6 (1.8) | 45 | 40.7 | |

| 4 | 84 | 10.4 | 25.6 (1.9) | 29 | 28.5 | |

| >4 | 50 | 6.6 | 24.1 (1.8) | 13 | 22.7 | |

| Working since diagnosis | ||||||

| No | 303 | 54.0 | 26.4 (1.0) | 110 | 36.6 | 0.24 |

| Yes | 295 | 46.0 | 29.7 (1.1) | 129 | 42.5 | |

| Lost job due to diagnosis | ||||||

| No | 568 | 96.5 | 27.5 (0.7) | 221 | 37.8 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 29 | 3.5 | 38.1 (3.3) | 17 | 73.6 | |

| Current insurance | ||||||

| Private | 404 | 69.2 | 28.3 (0.9) | 165 | 41.3 | 0.31 |

| Medicare | 88 | 19.9 | 26.0 (1.6) | 30 | 34.3 | |

| Medicaid | 66 | 6.0 | 29.6 (2.7) | 29 | 45.7 | |

| None | 38 | 4.9 | 28.1 (2.0) | 14 | 26.5 | |

|

Unable to see a doctor because of finances (in past 10 years) |

||||||

| No | 475 | 83.9 | 27.6 (0.8) | 184 | 39.0 | 0.67 |

| Yes | 126 | 16.1 | 29.7 (1.6) | 56 | 41.7 | |

|

Unable to see a doctor because of lack of transportation (in past 10 years) |

||||||

| No | 568 | 97.1 | 27.9 (0.7) | 226 | 39.4 | 0.82 |

| Yes | 33 | 2.9 | 30.0 (3.4) | 14 | 41.6 | |

| Family history | ||||||

| None | 345 | 56.3 | 28.6 (1.0) | 137 | 40.6 | 0.90 |

| First-degree | 81 | 14.0 | 26.2 (1.7) | 33 | 40.1 | |

| Second-degree | 132 | 21.6 | 28.1 (1.5) | 53 | 38.3 | |

| Both | 43 | 8.1 | 26.4 (2.4) | 17 | 33.8 | |

| Method of detection | ||||||

| Routine mammogram | 260 | 52.6 | 29.3 (1.1) | 111 | 44.0 | 0.27 |

| Clinical breast exam | 33 | 5.5 | 24.2 (3.0) | 11 | 31.5 | |

| Self-or spouse-detected | 293 | 40.1 | 26.5 (0.9) | 110 | 34.7 | |

| Other | 12 | 1.9 | 32.3 (6.1) | 6 | 40.5 | |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| No | 384 | 68.5 | 28.9 (0.9) | 163 | 42.5 | 0.064 |

| Yes | 217 | 31.5 | 26.0 (1.2) | 77 | 32.9 | |

| AJCC disease stage | ||||||

| I | 245 | 47.4 | 27.6 (1.1) | 94 | 39.5 | 0.60 |

| IIA | 160 | 26.3 | 28.9 (1.5) | 67 | 42.2 | |

| IIB | 94 | 13.1 | 28.6 (1.6) | 47 | 41.9 | |

| III/IV | 101 | 13.1 | 26.8 (1.7) | 32 | 31.7 | |

| First treatment | ||||||

| Breast conserving surgery | 312 | 55.2 | 26.3 (1.0) | 104 | 35.6 | 0.16 |

| Mastectomy | 180 | 30.0 | 30.8 (1.4) | 89 | 46.0 | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 109 | 14.8 | 28.3 (1.6) | 47 | 40.7 | |

| Immediate reconstructiond | ||||||

| No | 112 | 64.6 | 26.0 (1.5) | 43 | 35.6 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 68 | 35.4 | 39.4 (2.1) | 46 | 64.9 | |

| I am satisfied with how I am coping | ||||||

| Quite a bit/very much | 423 | 71.1 | 27.6 (0.8) | 166 | 38.0 | 0.50 |

| Somewhat/ a little bit | 153 | 24.3 | 28.4 (1.5) | 63 | 41.9 | |

| Not at all | 23 | 4.6 | 31.1 (3.7) | 11 | 51.0 | |

| I have accepted my illness | ||||||

| Quite a bit/very much | 471 | 80.1 | 28.0 (0.8) | 193 | 39.6 | 0.75 |

| Somewhat/ a little bit | 118 | 18.4 | 27.9 (1.8) | 41 | 37.9 | |

| Not at all | 11 | 1.5 | 26.3 (5.7) | 6 | 53.4 | |

SE: standard error; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer

Category totals may not sum to 601 (study population total) due to missing values

Percentages represent overall population estimates calculated using weighted frequency data

P value from χ2 test

Percentages were calculated based on women who underwent mastectomy as their first course of treatment

Table 2.

Race, population characteristics, and breast cancer treatment delay

| Treatment Delay >30 days |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | African American |

White | African American |

||||||

| N | %a | N | %a | Pb | N | %a | N | %a | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||||||

| 20–39 | 39 | 6.7 | 30 | 7.8 | <0.01 | 13 | 33.3 | 14 | 46.7 |

| 40–49 | 114 | 19.6 | 107 | 27.6 | 32 | 28.1 | 54 | 50.5 | |

| 50–64 | 101 | 46.3 | 113 | 48.7 | 46 | 45.5 | 45 | 39.8 | |

| 65–74 | 60 | 27.5 | 37 | 15.9 | 21 | 35.0 | 15 | 40.5 | |

| Education | |||||||||

| 0–12 years, but no high school degree | 23 | 8.8 | 42 | 15.0 | <0.01 | 9 | 46.8 | 12 | 26.4 |

| High school graduate/GED | 51 | 18.5 | 68 | 25.0 | 22 | 42.1 | 33 | 48.6 | |

| Technical or business school | 27 | 10.4 | 32 | 12.1 | 11 | 43.1 | 13 | 40.7 | |

| Some college | 60 | 20.0 | 65 | 21.4 | 12 | 23.1 | 30 | 44.2 | |

| College degree or higher | 153 | 42.3 | 80 | 26.5 | 58 | 41.1 | 40 | 48.7 | |

| Income ($) | |||||||||

| ≤20,000 | 41 | 16.9 | 83 | 31.7 | <0.01 | 16 | 38.4 | 34 | 40.2 |

| 20,000 – 30,000 | 17 | 5.7 | 50 | 19.2 | 8 | 48.4 | 30 | 61.5 | |

| 30,000 – 50,000 | 52 | 19.6 | 46 | 16.8 | 17 | 35.7 | 21 | 43.4 | |

| 50,000 – 100,000 | 94 | 30.4 | 68 | 24.4 | 34 | 39.8 | 28 | 38.6 | |

| >100,000 | 87 | 27.2 | 22 | 7.8 | 28 | 34.6 | 12 | 54.8 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 212 | 63.6 | 124 | 43.2 | <0.01 | 77 | 40.1 | 58 | 45.4 |

| Formerly married | 82 | 31.3 | 109 | 39.9 | 29 | 35.2 | 47 | 42.1 | |

| Never married | 20 | 5.2 | 54 | 16.9 | 6 | 36.7 | 23 | 41.3 | |

| Household size | |||||||||

| 1 | 71 | 27.4 | 80 | 30.1 | 0.046 | 23 | 35.4* | 28 | 34.9 |

| 2 | 114 | 44.3 | 98 | 36.3 | 52 | 46.8* | 50 | 49.8 | |

| 3 | 43 | 10.8 | 60 | 18.1 | 16 | 38.6* | 29 | 45.2 | |

| 4 | 55 | 10.9 | 29 | 8.7 | 13 | 23.2* | 16 | 53.5 | |

| >4 | 30 | 6.6 | 20 | 6.7 | 8 | 20.9* | 5 | 29.5 | |

| Working since diagnosis | |||||||||

| No | 151 | 53.7 | 152 | 55.3 | 0.69 | 48 | 35.8 | 62 | 39.5 |

| Yes | 162 | 46.3 | 133 | 44.7 | 63 | 40.8 | 66 | 48.9 | |

| Lost job due to diagnosis | |||||||||

| No | 303 | 97.3 | 265 | 93.4 | 0.032 | 103 | 36.5* | 118 | 43.1 |

| Yes | 9 | 2.7 | 20 | 6.6 | 7 | 87.2* | 10 | 52.6 | |

| Current insurance | |||||||||

| Private | 238 | 72.3 | 166 | 57.5 | <0.01 | 89 | 40.6 | 76 | 44.4 |

| Medicare | 47 | 20.6 | 41 | 17.1 | 15 | 33.7 | 15 | 37.1 | |

| Medicaid | 12 | 3.0 | 54 | 17.6 | 5 | 49.0 | 24 | 43.6 | |

| None | 14 | 4.2 | 24 | 7.8 | 2 | 15.3 | 12 | 48.9 | |

| Unable to see a doctor because of |

|||||||||

| No | 272 | 87.3 | 203 | 70.9 | <0.01 | 98 | 38.6 | 86 | 41.1 |

| Yes | 42 | 12.7 | 84 | 29.1 | 14 | 37.1 | 42 | 49.1 | |

|

Unable to see a doctor because of lack of transportation (in past 10 years) |

|||||||||

| No | 311 | 99.2 | 257 | 89.1473 | <0.01 | 110 | 38.4 | 116 | 43.7 |

| Yes | 3 | 0.8 | 30 | 10.8527 | 2 | 42.9 | 12 | 41.3 | |

| Family history | |||||||||

| None | 170 | 55.0 | 175 | 61.2 | 0.35 | 62 | 40.2 | 75 | 41.8 |

| First-degree | 44 | 14.1 | 37 | 13.5 | 17 | 40.9 | 16 | 36.9 | |

| Second-degree | 72 | 22.1 | 60 | 19.8 | 24 | 35.5 | 29 | 50.0 | |

| Both | 28 | 8.8 | 15 | 5.4 | 9 | 30.5 | 8 | 54.0 | |

| Method of detection | |||||||||

| Routine mammogram | 154 | 55.6 | 106 | 41.0 | <0.01 | 64 | 44.2 | 47 | 43.0 |

| Clinical breast exam | 17 | 5.5 | 16 | 5.2 | 4 | 28.1 | 7 | 45.0 | |

| Self-or spouse-detected | 136 | 37.0 | 157 | 52.0 | 42 | 32.0 | 68 | 41.7 | |

| Other | 6 | 1.9 | 6 | 1.7 | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 70.0 | |

| Symptoms | |||||||||

| No | 214 | 70.5 | 170 | 60.8 | 0.018 | 85 | 42.2 | 78 | 43.6 |

| Yes | 100 | 29.5 | 117 | 39.2 | 27 | 29.3 | 50 | 43.1 | |

| AJCC disease stage | |||||||||

| I | 144 | 50.3 | 101 | 36.8 | <0.01 | 52 | 39.5 | 42 | 39.8 |

| IIA | 83 | 26.3 | 77 | 26.4 | 34 | 42.9 | 33 | 39.4 | |

| IIB | 41 | 11.9 | 53 | 17.7 | 17 | 36.5 | 30 | 55.6 | |

| III/IV | 45 | 11.5 | 56 | 19.1 | 9 | 26.0 | 23 | 44.6 | |

| First treatment | |||||||||

| Breast conserving surgery | 158 | 55.2 | 154 | 55.1 | 0.46 | 51 | 36.1 | 53 | 33.6* |

| Mastectomy | 102 | 30.7 | 78 | 27.4 | 42 | 43.1 | 47 | 58.2* | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 54 | 14.1 | 55 | 17.5 | 19 | 37.2 | 28 | 51.2* | |

| Immediate reconstructionc | |||||||||

| No | 56 | 62.1 | 56 | 74.8 | 0.079 | 16 | 32.4* | 27 | 46.6* |

| Yes | 46 | 37.9 | 22 | 25.2 | 26 | 60.6* | 20 | 92.5* | |

| I am satisfied with how I am coping | |||||||||

| Quite a bit/very much | 226 | 71.4 | 197 | 69.9 | 0.66 | 78 | 36.4 | 88 | 44.2 |

| Somewhat/ a little bit | 75 | 23.8 | 78 | 26.4 | 28 | 41.9 | 35 | 41.8 | |

| Not at all | 13 | 4.8 | 10 | 3.6 | 6 | 51.2 | 5 | 50.0 | |

| I have accepted my illness | |||||||||

| Quite a bit/very much | 250 | 80.7 | 221 | 77.8 | 0.26 | 90 | 37.9 | 103 | 46.2 |

| Somewhat/ a little bit | 61 | 18.2 | 57 | 19.3 | 20 | 39.3 | 21 | 32.7 | |

| Not at all | 3 | 1.1 | 8 | 2.9 | 2 | 57.9 | 4 | 47.1 | |

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer

Percentages represent overall population estimates calculated using weighted frequency data

P-value from χ2 test

Percentages were calculated based on women who underwent mastectomy as their first course of treatment

P value from χ2 test <0.05 for the association of the characteristic with delay

Results

Population characteristics

The contact rate for the study (number of women selected for the study - number of women who could not be located or did not respond) was 95.4%. The cooperation rate (number of women who completed interviews/number of women contacted and eligible) was 80.2%. The overall response rate (number of completed interviews/[number of women selected - number ineligible or deceased]) (38) was 75.9%. The median time elapsed between diagnosis and the baseline interview was 5.1 months (interquartile range [IQR] = 4.0–6.2 months). The median time from diagnosis until treatment was 27.0 days (IQR = 18.0–37.0 days) for the study population and 26.2 days (IQR = 16.3–36.1 days) for the overall population. The majority (84.2%) of women in the overall population had a CNB prior to treatment. There was no association between receipt of a CNB and race (P = 0.39) in the overall population (or study population). There was a significant association between receipt of a CNB and income (P = 0.047) in the overall population: 93.3% of women with an income of >$100,000 had a CNB versus 79.2%–81.6% of women with lower incomes.

As shown in Table 1, delay was significantly associated with household size (P = 0.011), losing a job due to one's diagnosis (P < 0.01), and immediate reconstruction after mastectomy (P < 0.01). Women with smaller households were more likely than women with larger households to experience delay: 35.2%–47.3% for households of ≤ 3 people versus <30% for households of >3 people. Women who lost a job due to their diagnosis and who underwent immediate reconstruction were nearly twice as likely to experience delay compared to women who did not (73.6% versus 37.8%, and 64.9% versus 35.6%, respectively). The prevalence of women in the overall population with households of ≤ 3 people, who lost a job due to their diagnosis, and who underwent immediate reconstruction was 17.0%, 3.5%, and 10.6%, respectively. The latter value is the product of the immediate reconstruction and mastectomy rates. African American women were slightly more likely than White women to experience delay (43.4% versus 38.4%; P = 0.24). None of the other characteristics were significantly associated with delay.

Few women experienced a delay of >60 days (2.6%; data not shown). Race was strongly associated with delays of this length, with African American women being more than three times as likely as White women to experience delay (6.0% versus 1.7%; P = 0.013). For most categories, less than 5% of women experienced a delay of >60 days. Women in the following categories were exceptions: underwent immediate reconstruction (12.9%), were unable to see a doctor in the past 10 years due to a lack of transportation (9.3%), completed technical or business school (6.3%), underwent mastectomy (6.1%), had not accepted their illness at all (6.1%), had Medicaid coverage (5.5%), and had a household of 4 people (5.3%).

Race, population characteristics, and breast cancer treatment delay

African American women differed markedly from White women for nearly every demographic and socioeconomic characteristic, measure of healthcare access, and clinical factor (Table 2). The following characteristics were exceptions: working since diagnosis (P = 0.69), family history (P = 0.35), first course of treatment (P = 0.46), and immediate reconstruction (P = 0.079). Race was not associated with the measures of emotional and functional well-being: P = 0.67 and P = 0.26 for the degree of satisfaction with their coping and acceptance of their illness, respectively. Among the characteristics associated with delay, African American women were more than twice as likely as White women to lose a job due to their diagnosis (6.6% versus 2.7%), slightly more likely to have a household of ≤ 3 people, (84.6% versus 82.5%), and less likely to undergo immediate reconstruction (25.2% versus 37.9%).

The stratified data (Table 2) revealed that the determinants of delay are not equivalent for White and African American women. The only determinant common to both groups was immediate reconstruction (P < 0.01 for each group). Household size and losing a job due to one’s diagnosis were significantly associated with delay among White women (P = 0.027 and P < 0.01, respectively), while the first course of treatment was significantly associated with delay among African American women (P < 0.01).

While race was not associated with delay in the aggregated data, the stratified data revealed racial disparities for women with similar characteristics (e.g. same educational level). African American women were more likely than White women to experience delay for most characteristics. For instance, 55.6% of African American women with stage IIB disease experienced delay versus 36.5% of White women with stage IIB disease. The frequency of delay for African American women exceeded the frequency for White women by >30% for the following categories: detection by a method other than a routine mammogram, clinical breast exam, or self-or spouse-detection (70.0% for African American women versus 33.3% for White women), no insurance coverage (48.9% for African American women versus 15.3% for White women), households of 4 people (53.5% for African American women versus 23.2% for White women), and undergoing immediate reconstruction (92.5% for African American women versus 60.6% for White women).

Losing a job due to one’s diagnosis was associated with the highest probability of delay among White women. It was also the only characteristic in which the frequency of delay among White women was >30% higher than for African American women: 87.2% versus 52.6%. Having no insurance coverage was associated with the lowest probability of delay among White women (15.3%). Age (P = 0.067) and symptoms (P = 0.051) also showed evidence of an association with delay among White women. Women ages 50–64 and without symptoms tended to be more likely to experience delays. Undergoing immediate reconstruction was associated with the highest probability of delay among African American women, while having less than a high school degree was associated with the lowest probability of delay (26.4%). Income (P = 0.090) showed evidence of an association with delay among African American women, but there was no clear trend among categories.

Association of selected study population characteristics with delay

In the fully adjusted models, women with 2-person households were more likely than single person households to experience delay (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.19–3.63) (Table 3). The probability of delay decreased with increasing household size for households of ≥2 people. Women who lost a job due to their diagnosis were more likely to experience delay compared to women who did not (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.00–4.81), although the result was not significant (P = 0.050). Women who underwent mastectomy with immediate reconstruction (OR, 6.18; 95% CI, 3.27–11.68) and neoadjuvant therapy (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.16–3.66) were more likely than women who received BCS to experience delay.

Table 3.

Association of selected characteristics with treatment delays of >30 days in the study population

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Crude Model | Fully Adjusted Model |

| Household size | ||

| 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2 | 1.89 (1.22–2.94)* | 2.08(1.19–3.63)* |

| 3 | 1.48 (0.85–2.58) | 1.61(0.86–3.02) |

| 4 | 1.18 (0.64–2.20) | 1.30(0.64–2.68) |

| >4 | 0.79 (0.37–1.66) | 0.87(0.38–2.01) |

| Lost job due to diagnosis | ||

| No | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Yes | 2.04 (0.94–4.42) | 2.19(1.00–4.81) |

| First treatment/reconstruction | ||

| Breast conserving surgery | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 1.30 (0.82–2.05) | 1.45 (0.84–2.50) |

| Mastectomy with reconstruction | 5.82 (3.16–10.73)* | 6.18 (3.27–11.68)* |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 1.68 (1.05–2.71)** | 2.06 (1.16–3.66)** |

CI: confidence interval; Crude Model: adjusted for race, age, race x age; Fully Adjusted models: Household size additionally adjusted for marital status; Lost job due to diagnosis additionally adjusted for education; First treatment/reconstruction additionally adjusted for income, insurance, education, disease stage

P < 0.01

P < 0.05

Association of race with delay for the study population

Racial disparities in delay were significant among women <50 years old (Table 4). The disparity was largely explained by the low likelihood of delay among younger White women. African American women were more than three times as likely as White women to experience delay among women 20–39 years old (OR, 3.34; 95% CI, 1.07–10.38) and 40–49 years old (OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 1.76–6.54). Among White women, delays were less likely for 20–39 year old and 40–49 year old women (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.13–0.80 and OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.20–0.73, respectively) relative to women 50–64 years old. The likelihood of delay for African American women did not differ significantly based on age.

Table 4.

Association of race with treatment delays of >30 days in the study population

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race, Age range | Crude Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Fully Adjusted Model |

| White, 20–39 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American, 20–39 | 1.75 (0.66–4.66) | 1.52 (0.55–4.15) | 1.91 (0.68–5.37) | 3.34(1.07–10.38)** |

| White, 40–49 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American, 40–49 | 2.61 (1.50–4.56)* | 2.45 (1.37–4.39)* | 2.56 (1.42–4.64)* | 3.40(1.76–6.54)* |

| White, 50–64 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American, 50–64 | 0.79 (0.46–1.36) | 0.84 (0.47–1.52) | 0.84 (0.46–1.52) | 0.95 (0.51–1.77) |

| White, 65–74 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American, 65–74 | 1.27 (0.54–2.94) | 1.38 (0.54–3.53) | 1.34 (0.51–3.51) | 1.45 (0.54–3.91) |

| White, 20–39 | 0.60 (0.28–1.29) | 0.64 (0.29–1.42) | 0.57 (0.25–1.30) | 0.32(0.13–0.80)** |

| White, 40–49 | 0.47 (0.26–0.82)* | 0.52 (0.29–0.93)** | 0.49 (0.27–0.89)** | 0.38(0.20–0.73)* |

| White, 50–64 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| White, 65–74 | 0.64 (0.33–1.24) | 0.81 (0.37–1.78) | 0.77 (0.34–1.75) | 0.87(0.38–2.02) |

| African American, 20–39 | 1.32 (0.59–2.97) | 1.15 (0.50–2.67) | 1.30 (0.55–3.08) | 1.12(0.44–2.86) |

| African American, 40–49 | 1.54 (0.90–2.63) | 1.49 (0.85–2.62) | 1.48 (0.84–2.63) | 1.37(0.75–2.48) |

| African American, 50–64 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American, 65–74 | 1.03 (0.48–2.20) | 1.32 (0.54–3.20) | 1.23 (0.50–3.03) | 1.33(0.52–3.40) |

CI: confidence interval; Crude Model: adjusted for age, race x age; Model 1: adjusted for age, race x age, income, insurance; Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 variables, education, lost job; Fully Adjusted Model: adjusted for Model 2 variables, marital status, disease stage, symptoms, first treatment/reconstruction

P < 0.01

P < 0.05

Discussion

This study found that African American women were more likely than White women to experience delay among younger age groups (<50 years), but not among older age groups. This disparity was not evident in the overall population, as we found no association between race and delay in the aggregated data. Household size, losing a job due to one’s diagnosis, and immediate reconstruction were associated with delay in the overall population and among White women, respectively. Among African American women, who were a minority in the overall population, immediate reconstruction and first course of treatment were associated with delay. The adjusted models demonstrated that women with 2-person households experienced greater delay than women with other household sizes and women who had mastectomy with immediate reconstruction experienced greater delay than women who received other treatments.

It is unclear why a smaller household size was associated with delay. Further investigation is needed to understand this finding. Increased delay among women who lose a job due to their diagnosis may be related to a loss of employer-based insurance coverage, greater financial constraints, or an unsupportive work environment. We are unaware of any quantitative studies of treatment delay that evaluate employment changes. Losing a job may impact delay only among White women because they are more likely to have private coverage(1, 29, 39, 40). African American women were more likely than White women to lose a job due even though the frequency of working since one's diagnosis was comparable for both racial groups. This result is in agreement with a study that found that African American women were more likely than White women, to stop working (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.3–6.7) or miss work for >1month (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.2–7.4), respectively, compared to missing work for ≤ 1 month(41). African American women are also less likely than White women to be employed 18 months following diagnosis (OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.18–0.68)(42).

The additional time necessary for consultation and coordination of the schedules of the plastic surgeon and primary surgeon may explain the increased delay associated with immediate reconstruction. This is not the first study to report increased delay associated with this procedure(19, 43), but most studies on treatment delay do not consider this factor. Immediate reconstruction was the only factor associated with delay for both racial groups. African American women were less likely than White women to undergo immediate reconstruction, but more likely to experience delays if they underwent this procedure. Although not significant, our finding that African American women are less likely to undergo immediate reconstruction has been observed in several studies(44–46). First course of treatment was associated with delay only among African American women and was not explained by differences in the types of treatment received. African American and White women may differ in this determinant because they receive care at different types of healthcare facilities as a result of insurance status and income(16, 47, 48), residential segregation(49, 50), and urban/rural residence(48). Healthcare facility characteristics are known to affect treatment delay(15, 17). Immediate reconstruction rates also vary based on the healthcare facility (51).

It is challenging to compare the frequency of treatment delay across studies due to variations in study design, recruitment criteria, and study population characteristics. The start point of the treatment delay period has been defined in various ways, including the date of first clinical confirmation (15, 23), a suspicious finding (15), and pathological diagnosis (7). Eligibility restrictions based on disease stage (15, 21, 43) and type of treatment received (e.g. one type (16, 43, 52) versus all types (14, 47)) also limit comparability. Recruitment of women from a specific healthcare facility or set of facilities (e.g. single versus multiple, public/public safety net versus private)(16, 23, 53) and a specific program(22, 52) may lead to marked differences in population characteristics. The frequency of delay (>30 days) reported in the literature (7–9, 14–18, 52) ranges from 21.8% (7) to 68.9% (16). Our result (39.4%) is similar to the results from two different national studies (15, 17) that obtained values of 34.9% and 42.6%, respectively.

The frequency of delay reported in the literature for African American and White women (7–9, 14, 16–18) ranges from 18.7% (14) to 70.8% (16) and 4.7% (14) to 56.1% (16), respectively. Our results (43.3% and 38.4% for African American and White women, respectively) are fairly similar to those from a national study that reported values of 53.0% and 40.4%, respectively (17). Delays of >60 days were uncommon in this population, but are more frequent in studies focusing on women who are uninsured, have Medicaid coverage, or have low incomes(23, 54). Our finding that African American women are more likely to experience a delay of >60 days is consistent with other studies(17, 18). Since the determinants of delay identified in bivariate analysis are highly dependent on the predominant study population characteristics, this may explain the conflicting literature on racial disparities in treatment delay. Studies that do not report an association between race and delay tend to restrict the study population based on socioeconomic characteristics, disease stage, or the healthcare facility at which they receive care(21–23, 52). Differences in the determinants of treatment delay and racial disparities in delay are likely diminished for more homogeneous populations.

The findings of this study suggest the need to focus on well-defined populations when using treatment delay to make comparisons between groups, monitor changes over time, or assess quality of care. Interpreting this measure is not straightforward since it is affected by many factors, including disease stage (15), education (14), poverty index (14), urban/rural residence (9), marital status (14, 16), comorbidities (14, 15, 17), signs/symptoms at presentation (55), mammography history (14), hospital type(15–17, 47), whether diagnosis and treatment occur at the same or different hospitals (15), and year of diagnosis(15, 17). Treatment delay has been used to evaluate the quality of the NBCCEDP and the impact of policy changes(56). Although 94% of women meet their target of initiating treatment ≤60 days after diagnosis, racial disparities exist and could be related to programmatic differences and geographic distinctions among other factors(7, 56). Therefore, interpreting and addressing this disparity is challenging even though participants share many characteristics and follow similar treatment guidelines.

Our findings also suggest that developing effective interventions for treatment delay require studies targeting specific populations. The impact of treatment delay on survival has been investigated in highly selected populations, including women in a program targeting underserved populations (22), with Medicaid coverage(54), with triple negative breast cancer(57), receiving care at two hospitals served by the same providers following identical clinical protocols (47), and with metastatic disease (21). The results may not be generalizable, but these studies are helpful for identifying specific populations who may experience negative outcomes and the clinically relevant delay period. For instance, a study of Medicaid recipients in North Carolina found that a treatment delay of ≥60 days was associated with higher breast cancer–specific mortality among women with late stage disease (hazard ratio, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.04–3.27), but not among women with early stage disease(54). Characterizing and addressing the determinants of delay for this specific subgroup of Medicaid recipients could have a major public health impact.

One study limitation is that baseline interviews are conducted 5 months after diagnosis. Treatments subsequent to the first course of treatment may affect responses, and some factors may have changed during this interval. Recall bias may also influence the results. Detailed household composition information (e.g. number of children, wage earners) was not collected, which limits our ability to interpret findings for this determinant. We could not calculate poverty indices based on household size and income because we only collect information on income categories.

Several factors known to impact timeliness of care were not captured in our study. We did not have information on the healthcare facility where the women received care (e.g. urban/rural location, type). A greater number of comorbidities is associated with increased treatment delay (14, 15, 17) and African American race(14, 17), but was not assessed in our analysis. Finally, we did not collect information from participants about their interaction with providers. African American women are less trusting of their cancer treatment team(58). Providers also communicate differently with African American and White patients(59).

In conclusion, we found that the determinants of treatment delay vary by race, a finding that may help explain the conflicting literature on racial disparities. Further investigation is needed to determine the clinical relevance of the determinants we identified. Younger African American women may need additional support to ensure timely care comparable to White women. Our findings support targeting specific populations when identifying and addressing determinants of treatment delay.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susan Campbell for her expert guidance on the medical record data, the Carolina Breast Cancer Study research team for their hard work to collect the data, and all of the study participants who share their personal and medical information and make this research possible.

Grant Support

This research was funded in part by the University Cancer Research Fund of North Carolina and the National Cancer Institute Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer (NIH/NCI P50-CA58223).

Financial Support: S. McGee, R. Millikan+, C. Tse: University Cancer Research Fund of North Carolina and the National Cancer Institute Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer (NIH/NCI P50-CA58223)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Berz JPB, Johnston K, Backus B, Doros G, Rose AJ, Pierre S, et al. The influence of black race on treatment and mortality for early-stage breast cancer. Medical care. 2009;47:986–992. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819e1f2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menashe I, Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Rosenberg PS. Underlying causes of the black-white racial disparity in breast cancer mortality: A population-based analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albain KS, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr., Hershman DL. Racial disparities in cancer survival among randomized clinical trials patients of the southwest oncology group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:984–992. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer-Chammard A, Taylor TH, Anton-Culver H. Survival differences in breast cancer among racial/ethnic groups: A population-based study. Cancer detection and prevention. 1999;23:463–473. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1500.1999.99049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman LA, Griffith KA, Jatoi I, Simon MS, Crowe JP, Colditz GA. Meta-analysis of survival in african american and white american patients with breast cancer: Ethnicity compared with socioeconomic status. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:1342–1349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman CS, Shockney L, Rabinowitz B, Coleman C, Beard C, Landercasper J, et al. National quality measures for breast centers (nqmbc): A robust quality tool: Breast center quality measures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:377–385. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan LS, May DS, Richardson LC. Time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: Results from the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program, 1991–1995. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:130–134. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmore JG, Nakano CY, Linden HM, Reisch LM, Ayanian JZ, Larson EB. Racial inequities in the timing of breast cancer detection, diagnosis, and initiation of treatment. Med Care. 2005;43:141–148. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorin SS, Heck JE, Cheng B, Smith SJ. Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by racial/ethnic group. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2244–2252. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman HJ, LaVerda NL, Levine PH, Young HA, Alexander LM, Patierno SR, et al. Having health insurance does not eliminate race/ethnicity-associated delays in breast cancer diagnosis in the district of columbia. Cancer. 2011;117:3824–3832. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:923–930. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, Wong YN, Edge SB, et al. Time to diagnosis and breast cancer stage by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;136:813–821. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2304-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashing-Giwa KT, Gonzalez P, Lim JW, Chung C, Paz B, Somlo G, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic delays among a multiethnic sample of breast and cervical cancer survivors. Cancer. 2010;116:3195–3204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwyn K, Bondy ML, Cohen DS, Lund MJ, Liff JM, Flagg EW, et al. Racial differences in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical delays in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:1595–1604. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS, Stewart AK, Talamonti MS, Hynes DL, et al. Wait times for cancer surgery in the united states: Trends and predictors of delays. Annals of Surgery. 2011;253:779–785. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318211cc0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosunjac M, Park J, Strauss A, Birdsong G, Du V, Rizzo M, et al. Time to treatment for patients receiving bcs in a public and a private university hospital in atlanta. Breast J. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fedewa SA, Edge SB, Stewart AK, Halpern MT, Marlow NM, Ward EM. Race and ethnicity are associated with delays in breast cancer treatment (2003–2006) Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22:128–141. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund MJ, Brawley OP, Ward KC, Young JL, Gabram SSG, Eley JW. Parity and disparity in first course treatment of invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2008;109:545–557. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, Ross E, Wong Y-N, Patel SA, et al. Preoperative delays in the us medicare population with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:4485–4492. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halpern MT, Holden DJ. Disparities in timeliness of care for u.S. Medicare patients diagnosed with cancer. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:e404–e413. doi: 10.3747/co.19.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung SY, Sereika SM, Linkov F, Brufsky A, Weissfeld JL, Rosenzweig M. The effect of delays in treatment for breast cancer metastasis on survival. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011;130:953–964. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith ER, Adams SA, Das IP, Bottai M, Fulton J, Hebert JR. Breast cancer survival among economically disadvantaged women: The influences of delayed diagnosis and treatment on mortality. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2008;17:2882–2890. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams DL, Tortu S, Thomson J. Factors associated with delays to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in women in a louisiana urban safety net hospital. Women & Health. 2010;50:705–718. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2010.530928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler LM, Potischman NA, Newman B, Millikan RC, Brogan D, Gammon MD, et al. Menstrual risk factors and early-onset breast cancer. Cancer Causes & Control. 2000;11:451–458. doi: 10.1023/a:1008956524669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, Epstein AM. The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 1993;329:326–331. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:490–496. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roetzheim RG, Gonzalez EC, Ferrante JM, Pal N, Van Durme DJ, Krischer JP. Effects of health insurance and race on breast carcinoma treatments and outcomes. Cancer. 2000;89:2202–2213. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2202::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halpern MT, Ward EM, Pavluck AL, Schrag NM, Bian J, Chen AY. Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: A retrospective analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:222–231. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedman RA, Virgo KS, He Y, Pavluck AL, Winer EP, Ward EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity, insurance status, and socioeconomic factors with breast cancer care. Cancer. 2011;117:180–189. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diez-Roux AV. Bringing context back into epidemiology: Variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:216–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webster TF, Hoffman K, Weinberg J, Vieira V, Aschengrau A. Community- and individual-level socioeconomic status and breast cancer risk: Multilevel modeling on cape cod, massachusetts. Environmental health perspectives. 2008;116:1125–1129. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert SA, Strombom I, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, McElroy JA, Newcomb PA, et al. Socioeconomic risk factors for breast cancer: Distinguishing individual- and community-level effects. Epidemiology. 2004;15:442–450. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000129512.61698.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, Cokkinides V, DeSantis C, Bandi P, et al. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2008;58:9–31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman B, Moorman PG, Millikan R, Qaqish BF, Geradts J, Aldrich TE, et al. The carolina breast cancer study: Integrating population-based epidemiology and molecular biology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;35:51–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00694745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the carolina breast cancer study. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westreich D, Greenland S. The table 2 fallacy: Presenting and interpreting confounder and modifier coefficients. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:292–298. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moorman P, Newman B, Millikan R, Tse C-K, Sandler D. Participation rates in a case-control study:: The impact of age, race, and race of interviewer. Annals of Epidemiology. 1999;9:188–195. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, Schrag D, Godfrey H, Hiotis K, et al. Missed opportunities: Racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reynolds P, Hurley S, Torres M, Jackson J, Boyd P, Chen VW. Use of coping strategies and breast cancer survival: Results from the black/white cancer survival study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:940–949. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;119:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0389-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo ZH. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:345–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner JL, Warneke CL, Mittendorf EA, Bedrosian I, Babiera GV, Kuerer HM, et al. Delays in primary surgical treatment are not associated with significant tumor size progression in breast cancer patients. Annals of Surgery. 2011;254:119–124. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318217e97f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agarwal S, Pappas L, Neumayer L, Agarwal J. An analysis of immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction frequency using the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Breast J. 2011;17:352–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alderman AK, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. Use of breast reconstruction after mastectomy following the women's health and cancer rights act. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:387–388. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosson GD, Singh NK, Ahuja N, Jacobs LK, Chang DC. Multilevel analysis of the impact of community vs patient factors on access to immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy in maryland. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1076–1081. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1076. discusion 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brazda A, Estroff J, Euhus D, Leitch AM, Huth J, Andrews V, et al. Delays in time to treatment and survival impact in breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2010;17:S291–S296. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong AL, Yen TW, Pezzin LE, Miao H, Sparapani RA, Laud PW, et al. Socioeconomic and racial differences in treatment for breast cancer at a low-volume hospital. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3220–3227. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2001-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary R. Residential segregation and disparities in health care services utilization. Medical Care Research and Review. 2012;69:158–175. doi: 10.1177/1077558711420263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White K, Haas JS, Williams DR. Elucidating the role of place in health care disparities: The example of racial/ethnic residential segregation. Health services research. 2012;47:1278–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hershman DL, Richards CA, Kalinsky K, Wilde ET, Lu YS, Ascherman JA, et al. Influence of health insurance, hospital factors and physician volume on receipt of immediate post-mastectomy reconstruction in women with invasive and non-invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136:535–545. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2273-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balasubramanian BA, Demissie K, Crabtree BF, Strickland PA, Pawlish K, Rhoads GG. Black medicaid beneficiaries experience breast cancer treatment delays more frequently than whites. Ethnicity & disease. 2012;22:288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Komenaka IK, Martinez ME, Pennington RE, Jr., Hsu CH, Clare SE, Thompson PA, et al. Race and ethnicity and breast cancer outcomes in an underinsured population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1178–1187. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLaughlin JM, Anderson RT, Ferketich AK, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R, Paskett ED. Effect on survival of longer intervals between confirmed diagnosis and treatment initiation among low-income women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:4493–4500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.39.7695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramirez AJ, Westcombe AM, Burgess CC, Sutton S, Littlejohns P, Richards MA. Factors predicting delayed presentation of symptomatic breast cancer: A systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353:1127–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson LC, Royalty J, Howe W, Helsel W, Kammerer W, Benard VB. Timeliness of breast cancer diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program, 1996–2005. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1769–1776. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eastman A, Tammaro Y, Moldrem A, Andrews V, Huth J, Euhus D, et al. Outcomes of delays in time to treatment in triple negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2835-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaiser K, Rauscher GH, Jacobs EA, Strenski TA, Ferrans CE, Warnecke RB. The import of trust in regular providers to trust in cancer physicians among white, african american, and hispanic breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH. Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: Disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient education and counseling. 2006;62:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.