Abstract

This paper examines geographic mobility and housing downsizing at older ages in Britain and America. Americans downsize housing much more than the British largely because Americans are much more mobile. The principal reasons for greater mobility among older Americans are two fold: (1) greater spatial distribution of geographic distribution of amenities (such as warm weather) and housing costs and (2) greater institutional rigidities in subsidized British rental housing providing stronger incentives for British renters not to move. This relatively flat British housing consumption with age may have significant implications for the form and amount of consumption smoothing at older ages.

Population ageing has led to an increasing interest amongst both policy makers and academic researchers alike in the consumption and wealth trajectories of individuals and households at older ages. The broad issue is one of whether individuals are accumulating enough assets to fund longer retirements, but within that overarching issue are a number of other questions relating to the way in which resources are accumulated prior to retirement and the degree to which they are drawn upon after retirement. One such set of questions relate to housing wealth, the consumption of housing services, and the role that each plays in life-cycle accumulation and decumulation trajectories.

The empirical study of home-ownership trajectories at older ages has a long history, dating back to the first studies of ‘downsizing’ of housing in the US by Merrill (1984) and Venti and Wise (1989, 1990). Evidence from these and subsequent studies was somewhat mixed with regard to the extent to which individuals and households drew down their housing wealth when observed at older ages in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

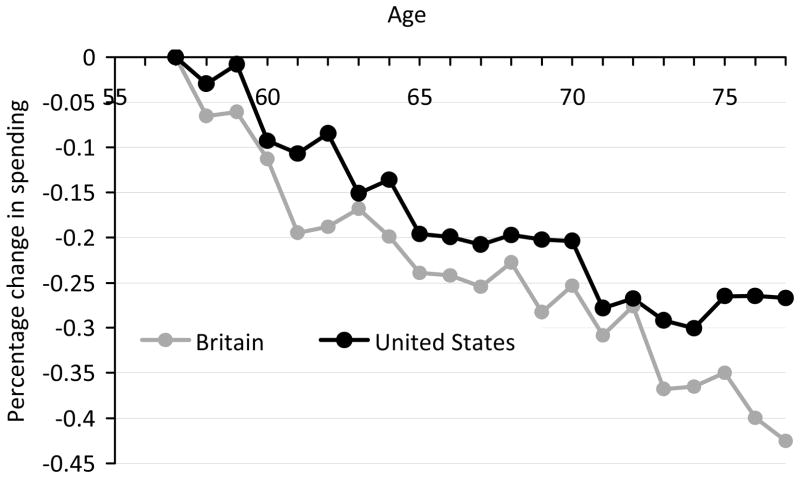

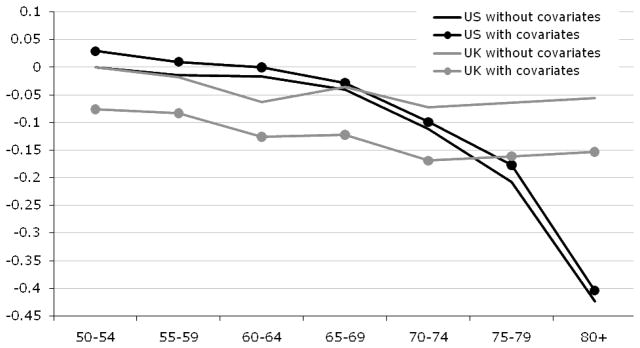

In a recent cross-national comparative study, we examined downsizing in the US and Britain. We showed, using the same household data that will be used in this study, that housing downsizing was an important part of life for many older households in both countries over the period 1984–2006 (Banks et al. 2010). Figure 1, taken from that analysis, shows more specifically that amongst those who moved at middle and older ages there is, on average, a reduction in the number of rooms in household residences as age increases. This reduction is somewhat larger in the United States than in Britain but is apparent in both countries, regardless of whether one looks at the raw data or controls for other marital status, family size, or employment transitions that occur with age. Other measures of downsizing, such as the change in gross house value for movers, demonstrated the same patterns.

Figure 1. Normalised change in number of rooms by age, movers only.

Note: Figure 1 depicts change in number of rooms across age groups normalized to zero change in age band 50–54. These changes are provided based on a model that only includes age dummies for each age band, and a model that also includes measures of changes in family composition for spouse and children living at home and changes in employment status. These models are estimated using PSID and BHPS data (see Banks et al. (2010) for further details).

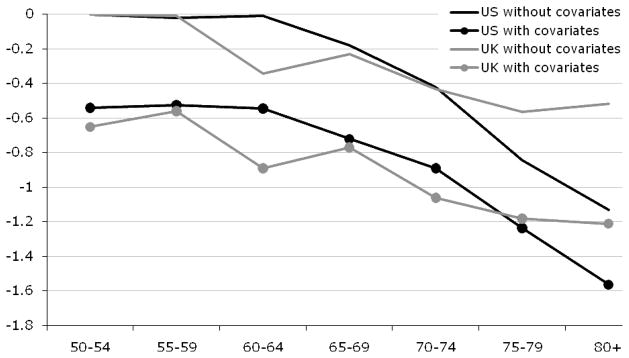

When one looks at the population level rather than only movers, however, the evidence points to much less downsizing in Britain than in the US. Figure 2, taken from the same study, shows that across all families aged 50 or more downsizing was much less common in Britain compared to the US. The two figures together suggest that the main factor underlying lower rates of downsizing in Britain is a much smaller frequency of moving amongst older households in Britain compared to America. This paper aims to investigate the reasons for this quite different pattern of residential mobility at older ages in the two countries.

Figure 2. Normalised change in number of rooms by age, all households.

Note: See notes to Figure 1.

In this paper we document and model housing mobility choices of the middle-aged and elderly in Great Britain and the United States. We show that the differential in mobility rates is particularly high among renters, indicating that a simple explanation of higher transactions costs for owner-occupier movers is unlikely to be the full explanation. Hence, we will examine a number of other potential factors. There are several reasons for housing mobility at older ages, including demographic transitions, particularly those associated with marital transitions and/or children leaving home, and labor force transitions primarily at these ages into retirement. But individuals may also move at older ages to consume higher levels of amenities such as a warmer winter climate, or to reduce the cost-of-living. Cost-of-living factors may include lower housing costs for either renters or owners or lower income taxes.

For many factors thought to induce greater mobility at older ages, there may be simply less opportunity in Britain to achieve these goals given the much smaller geographical size. Temperature and sunshine may exhibit less within-country variation, taxes and other location specific costs may be less spatially variable, and the structure of local tax rates may be more uniform in Britain compared to the United States. Hence we will document the extent of within-country variation in factors that are believed to encourage migration among older people and the degree to which actual moves that are made among older people appear to buy better amenities and lower taxes.

Higher mobility frictions may also differentiate the two countries. Many British renters have lived in council houses for long periods of time at subsidized rents with long waiting lists for new admissions. The incentives to remain in place for these people may be quite high. Higher transactions costs may also be associated with home ownership in Britain due to stamp taxes on sales of home. Taking into account all the factors mentioned in the last few paragraphs, these mobility decisions for renters and owners in both countries will be modeled separately in this paper. We will also separately model moves that take place within a British region or US State and those that cross between them, in order to separate out local amenity effects from those of national institutional differences.

This paper is divided into five sections. Section I describes the data sources used in both Britain and the US. Section II documents the principal facts about differential mobility of older households in Britain and the United States and describes their implications for housing consumption at older ages. In Section III we summarize the major factors that may produce differential mobility between these two countries. Section IV presents the results of models predicting mobility in the two countries for both renters and owners. In the final section, our principal conclusions are highlighted.

I. DATA

This research will rely on micro-data from the US (the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics (PSID)) and Britain (the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS)). Besides the standard set of demographics on age, schooling, family income, marriage and other aspects of family building, information available in all these surveys include several aspects of housing choice—ownership, size of house, and value of house.

The Panel Study of Income Dynamics

The PSID has gathered 40 years of extensive economic and demographic data on a nationally representative sample of approximately 5,000 (original) families and 35,000 individuals who live in those families. Details on family income and its components have been gathered in each wave since the inception of PSID in 1969. Starting in 1984 and in five-year intervals until 1999, PSID asked questions to measure household wealth. Starting in 1997, the PSID switched to a two-year periodicity, and wealth modules are now part of the core interview. Our analysis uses PSID data from the years 1969 to 2005. Attrition in the PSID is very low, averaging a few percentage points each wave (Becketti et al., 1988; Fitzgerald et al., 1998).

In each wave, the PSID asks detailed questions on family size and composition, schooling, education, age, and marital status. State of residence is available in every year and individuals are followed to new locations if they move. Unlike other American wealth surveys, PSID is representative of the complete age distribution. Yearly housing tenure questions determine whether individuals own, rent, or live with others. Questions on value and mortgage were asked in each wave of the PSID. Renters are asked the rent they pay, and both owners and renters are asked the number of rooms in the residence. In this paper, we use PSID data for the years 1969 through 2005.

British Household Panel Survey—BHPS

The BHPS has been running annually since 1991 and, like the PSID, is also representative of the complete age distribution. The wave 1 sample consisted of some 5,500 households and 10,300 individuals. The BHPS contains annual information on individual and household income and employment as well as a complete set of demographic variables and has several other features to recommend it. There is an extensive amount of information on mortgages and housing (including number of rooms) that enables us to measure housing wealth in each wave of the data.1 Regional variation in ownership and housing wealth accumulation will be essential in our tests and the data will provide us with sufficient observations per year in each region to carry out our tests. We use BHPS data for the years 1991–2007.

Throughout the paper, the unit of analysis is the individual. A family is defined as a single person or a couple (and any dependent children they may have). Any demographic information included in the analysis such as age or education relates to the individual. Financial information (income and wealth) is defined at the “family unit” level. This means that each individual is assigned the sum of income and wealth that they and their spouse have. We take care to define tenure in terms of the family unit rather than the household. In both countries, an individual is defined as an owner or a renter only if they are the individual (or the spouse of the individual) responsible for the property. This is to ensure that adults living in accommodation with other family members are not lost from the analysis as subsidiary adults in households headed by other individuals. Hence an 80 -year-old living rent-free with their adult children in an owned property is not defined as an owner (unless they own the property jointly)—they would be captured in our “other tenure” group.

II. TENURE STATUS AND TENURE TRANSITIONS

Homeownership rates and tenure transitions at older ages

Especially at older ages most Americans are homeowners. Based on multiple waves of the PSID and BHPS, Table 1 presents tenure status for individuals by age for ten-year age groups starting at age 50, concluding with a residual category of those 80 plus years old. To eliminate any differences due to a secular trend toward increased home ownership at older ages which exists in both countries, tenure status is defined over the same post-1990 time period in both countries. Table 1 shows that more than four in five of all Americans over age 50 are homeowners. Fifteen percent of Americans in this age group are renters, while a relatively small fraction are in the catch all ‘other categories’ that largely consist of those living with relatives or in a nursing home.2 Among older Americans, there is a decline in the fraction who are home owners across age groups after age 70, especially for those above age 80 where the home owner rate is only 63%. Most of the decline in the probability of owning a home appears as an increase in renting but some of it, particularly among those over age 70, reflects an increase in the likelihood of living with others or in a nursing home.

Table 1.

Tenure Status for Individuals by Age

| United States | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total 50+ | |

| Owner | 83.6 | 87.6 | 82.9 | 63.1 | 82.6 |

| Renter | 14.6 | 10.9 | 14.2 | 30.1 | 15.0 |

| Other | 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 6.8 | 2.4 |

|

| |||||

| Great Britain | |||||

| 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total 50+ | |

|

| |||||

| Owner | 79.8 | 73.4 | 64.5 | 48.3 | 70.2 |

| Renter | 17.7 | 24.2 | 32.4 | 45.1 | 26.6 |

| Other | 2.5 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 3.2 |

Source: PSID (1991–2005) and BHPS (1991–2007); Authors’ calculations from weighted individual level data. The table reports the fraction of individuals within each age group who own a home, rent a home, or have another tenure arrangement (largely living with other family members or in an institution such as a nursing home).

For British individuals over age 50, the probability of being a homeowner is about twelve percentage points lower than that of Americans, a deficit mostly offset by a higher probability of renting. There exists a much sharper negative homeownership age pattern in Britain compared to the US in Table 1. Among those in their fifties for example, there is about a four percentage point difference in home ownership rates between the two countries—by ages 80+ the likelihood of owning a home is 15 percentage points lower in Britain compared to the US. As documented in Banks et al. (2003), this sharp negative age gradient in home owning rates in Britain largely reflects cohort effects associated with the sale at subsidized rates of government owned council housing that made the previous renters now owners.

Changes in housing tenure with age

The very pronounced cohort effects in housing status in Britain mentioned in the previous section indicate that it would be perilous to attempt to read housing transitions from cross-sectional age housing tenure patterns, especially in Britain. Instead, in this section the most salient transitions are highlighted using the panel nature of the data in the US and Britain.

Since much of the existing research on downsizing at older ages focuses on the decision to sell one’s original home and become a renter (Venti and Wise 2001; Sheiner and Weil 1992), we begin with transitions conditional on originally being a homeowner. Table 2 examines these post 1991 tenure transitions in the United States (using the PSID) and Britain (using the BHPS) for a sub population who are at least 50 years old and who were originally home owners in the initial period. 3 Because the extent of any transitions that take place will depend on the length of the window during which households are allowed to adjust their status, the data are presented for five year durations between waves of the panel. Table 3 organizes the data in precisely the same way for those who were initially renters. We separate transitions in this data by the nature of the tenure transition—i.e., whether to owner or renter in the new home, and within these categories by whether the move went across a state line in the United States or across one of nine regions in Britain.

Table 2.

Five year housing transitions by age, owners at baseline

| United States | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total 50+ | |

| Owners who remained owners | |||||

| No move | 76.6 | 81.3 | 78.1 | 69.3 | 78.2 |

| Moved within state | 15.4 | 12.4 | 10.0 | 6.7 | 12.8 |

| Moved out of state | 4.0 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| Owners to renters | |||||

| Moved within state | 2.7 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 14.9 | 3.5 |

| Renter, Moved out of state | 0.65 | 0.54 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.78 |

| Owners to “other tenure” | |||||

| Moved within state | 0.43 | 0.77 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 |

| Moved out of state | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 1.3 | 0.34 |

|

| |||||

| Great Britain | |||||

|

| |||||

| 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total 50+ | |

|

| |||||

| Owners who remained owners | |||||

| No move | 85.6 | 88.9 | 88.8 | 89.5 | 87.5 |

| Moved within region | 9.6 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 3.2 | 7.9 |

| Moved out of region | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.6 |

| Owners to renters | |||||

| Moved within region | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 4.6 | 1.4 |

| Renter, Moved out of region | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Owners to “other tenure” | |||||

| Moved within region | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Moved out of region | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.09 |

Source: PSID (1991–2005) and BHPS (1991–2007); Authors’ calculations from weighted individual level data. Tenure transitions are defined over a five year period among individuals who were owners at the beginning of the time interval. These transitions are all defined by the end of five year period tenure status based on whether the respondent did not move, moved within a state or region or moved across state or region between the beginning and end of the five year period.

Table 3.

Five Year Housing Transitions by Age, Renters at Baseline

| United States | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | All 50+ | |

| Renters who remained renters | |||||

| No move | 33.0 | 35.4 | 43.8 | 45.0 | 37.3 |

| Moved within state | 26.2 | 36.8 | 33.5 | 30.0 | 30.8 |

| Moved out of state | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 2.4 |

| Renters to owners | |||||

| Moved within state | 28.6 | 14.2 | 12.3 | 10.4 | 19.3 |

| Renter, Moved out of state | 5.8 | 7.6 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| Renters to “other tenure” | |||||

| Moved within state | 3.0 | 3.9 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 4.4 |

| Moved out of state | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.73 |

Over a five year period, more than one in every five American home owners who were at least 50 years old moved out of an originally owned home. Among Americans who did move, however, three-quarters remained homeowners by purchasing another home. Another 20% of them became renters while the rest do a combination of things, including moving in with family members or into group dwellings. Mobility among homeowners is clearly less in Britain for older households. Across the same five year span, about one in every eight British homeowners relocated compared to about one in five American households. If we extend the horizon over which we examine mobility to ten years instead of five, one in every three American home owners would move compared to one in every four British homeowners.

Table 2 also shows that the majority of moves of home owners take place within the same region or state of their original home. In both Britain and the United States, 80% of the moves that homeowners did make left them residing in the same region or state of their original residence.

We turn next to the age pattern of mobility among homeowners. In the United States, amongst those who do move, the fraction that do not purchase another home increases with age—at older ages American owner occupiers increasingly move into rental properties and to a lesser extent into either assisted living or to stay with family members. The probability of a homeowner moving into a rental property is far less in Britain than in the US and it is a good deal less likely at older ages for an home owner in Britain to subsequently become a renter.

Table 3 demonstrates—not surprisingly—that renters in both countries are far more mobile than owners. Across the five year survey interval, almost two-thirds of American renters moved at least once compared to only one-in-five British renters. Once again, the majority of moves amongst American renters are within-state residential moves, but this is especially the case when the move is from one rental property to another. One in five American moves from rental to owner tenure status is across state lines.

British renters are far less mobile than their American renter counterparts, a much larger between country mobility differential than that which existed among home-owners. In the US, about half of originally renting households remained so and simply settle into another rented apartment or flat. But around 40% of American renters who do relocate over age 50 subsequently become homeowners. The comparable British number is less than half that – eighteen percent. In the US and in Britain, renters become increasingly less mobile with age. Forty-four percent of American renters in their seventies stay in the same place over a ten year horizon compared to 33% of American renters in their fifties. Eighty-nine percent of British renters over age 80 stay in the same place.

III. FACTORS RELATED TO GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY

Why is there so much less mobility at older ages in Britain compared to the United States? To attempt to address that question, Table 4.a lists summary statistics about the distribution of state level attributes that are potentially related to migration across states in the United States while Table 4.b displays a similar but not identical array of attributes for regions in Britain. These attributes include measures of spatially specific amenities that make a location an attractive place to live or not and the economic costs associated with living in one place rather than another. In addition to the mean, our summary stats on spatial distributions include minimum and maximum values, and the 90th minus 10th percentiles and 75th minus 25th percentile, both expressed relative to the median value.

Table 4A.

Distribution of Regional Assets—United States

| Min | (90th-10th)/50th | (75th-25th)/50th | Max | Mean* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean January Temperature | 6.73 | 0.99 | 0.45 | 61.65 | 32.03 |

| Cumulative Inches of Annual rainfall (inches) | 7.11 | 1.03 | 0.47 | 59.74 | 34.27 |

| Average Tax Rate-Lowest Incomea | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Average Tax Rate-Second Lowest | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Average Tax Rate-Third Highest | 0.12 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| Average Tax Rate-Highest Income | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.20 |

| Average Rent per room in1995 ($) | 225.00 | 1.57 | 0.68 | 5882.82 | 1308.95 |

| Average House Price per room in1995 ($’000) | 1.75 | 1.40 | 0.52 | 32.93 | 15.06 |

| Fraction of renters in Public or Subsidized Housing in1995c | 0.0 | 2.25 | 1.57 | 1.0 | 0.27 |

All taxes in year 1995

Table 4B.

Distribution of Regional Attributes—Britain

| Min | (90th-10th)/50th | (75th-25th)/50th | Max | Mean* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January Mid-Temperature | 36.32 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 39.56 | 37.49 |

| Annual rainfall (inches) | 23.67 | 0.89 | 0.63 | 59.90 | 43.33 |

| Average Annual Rent/room in1995 (£) | 569.41 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 1715.36 | 776.86 |

| Average House Price per room-1995 (£’000) | 12.49 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 26.48 | 16.86 |

| Fraction of renters in1995 | 0.18 | 0.74 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.24 |

| Fraction of renters in public Housing in 1995 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.91 | 0.81 |

| Fraction of renters in subsidized Housing | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.67 | 0.46 |

| (private or public) in1995 |

Notes: January Temperature and annual rainfall were obtained from the World Almanac in the United States and from the Met Office (http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/averages/) in Britain. Average tax rates in the United States were obtained using the NBER Taxsim program evaluated at four real income levels ($20,000, $40,000, $60,000 and $80,000 in year 1995) and reflect the federal and state tax codes in each year. We assign an individual the average tax rate in that year closest to their annual family income. The average rent per room and house price per room are means across the relevant geographic areas in 1995 using the PSID and BHPS. Similarly, the fraction of respondents who were renters and the fraction of renters who lived in subsidized or public housing were also computed at state or region levels in 1995 using the PSID and BHPS.

There is considerable variation amongst American states in spatial amenities compared to those in Britain—in particular mean winter temperature, hours of sunshine in January, and yearly rainfall. For example, the January spread between the 90th and 10th percentile state is equal to the median temperature State- thirty one degrees Fahrenheit. In contrast, in Britain the spread between the coldest and warmest region in January is only three degrees Fahrenheit. While the contrast between the two countries in the other spatial amenities is not as extreme, in all cases there exists far more diversity in the US compared to Britain. In general, and largely due to the much smaller size of the country, these types of spatially specific amenities are unlikely to generate much within country migration in Britain as there simply exists so little geographic variation that the opportunities to improve your lot through migration are quite small. This is clearly not the case in the United States.4

Turning to economic variables that might be related to migration, we focus on the following dimensions in the US—income taxes and rental and owning price of housing. Once again, there exists considerable variability across American States especially compared to limited regional variation in Britain. Some of this is inherent in governance difference between the two countries in the fiscal role assigned to local government units compared to the central government. In the US, income taxes are set at both the individual state level and a common federal level and states and local communities can also access property, sales, and occasionally income taxes. In Britain, the only major tax set at the local level is the council tax. This tax was introduced in 1993 (its predecessor was the community charge or poll tax). It is paid by both renters and owners and the level is roughly related to the value of your home.

Since tax rates vary by income in the United States, we characterize the geographical distribution of taxes by a small set of average tax rates per state. These tax rates are computed at four real income levels in each year ($20,000; $40,000; $60,000 and $80,000) for each state using the NBER Taxsim program. A family is assigned the tax rate closest to their family income. Average tax rates are a more appropriate indicator of tax incentives than marginal tax rates in this case since location choices are discrete (see Diamond (1980) or Griffith and Devereux (1998)). Not surprisingly, average tax rates by state increase significantly with income. Evaluated at the mean, average tax rate at the highest income is 20%, four times that at the lowest income group—5% at the lowest income level. For mobility decisions, it is variation in average tax rates among states at a given income level that is relevant. For those with low incomes, variation in average tax rates across states is relatively small and thus provides little incentive for mobility. For example, the difference in average tax rate at the 90th and 10th percentile is only 2.5% in the lowest income group. Variation in average taxes does increase as income rises. Comparing the 90th to 10th percentile, the difference in average taxes is 6 percentage points in the highest income group compared to 2.5 percentage points in the lowest income group.

Similarly, the average price per room whether computed as house price per room for owners or rental price per room for renters varies much more across American states than across British regions. Relative to the median, the spread between the 90th and 10th percentile in house price per room is 1.4 in the United States compared to 0.5 in Britain. Variation in rental prices shows a similar contrast between the countries. Using the same metric, relative to the median, the spread between the 90th and 10th percentile in rental price per room is 1.6 in the United States compared to 0.50 in Britain. These relative housing cost variations are a combination of the composition and quality of dwelling types and the cost of the area across the 50 US states or the 12 British regions.

The final row in Tables 4.a and 4.b captures a different aspect of geographic mobility by showing the fraction of rental homes that are subsidized in some way by government. There are two dimensions of subsidies that are recorded in the PSID—whether you live in a public housing project and whether a government subsidies part of the rent.5 Families in subsidized housing may be more reluctant to move or less able to move whilst retaining their subsidy. In the United States in 1995, about one in four renters aged over 50 live in some form of public or subsidized housing but once again there is a great deal of variation across states in this proportion.

In Great Britain, subsidized and public rental accommodation makes up a much larger proportion of the rental market particularly for the over fifties. There are two main programs providing financial support for housing. Both are aimed exclusively at renters and are means tested. The first is a system of subsidized housing, often referred to as local authority, social or council housing.6 Those who are allocated a property will pay a below-market rent and the landlord will be either the local authority or a housing association. Individuals who are entitled to such a property are placed on a waiting list until suitable accommodation becomes available.7 Whilst entitlement to live in social housing is subject to a strict means test, once allocated a property, tenants can usually stay for life irrespective of any changes in circumstance.8

The second program of financial assistance for British renters is the housing benefit system which was introduced in the late 1980s. This is a substantial component of the British welfare system and is simply a cash transfer from the government to the renter. It is not tied to a particular property but it is subject to a strict means test. The amount of benefit received is determined by personal circumstances and also the characteristics of the property (for example, whether the house is a reasonable size for the family). Housing benefit payments may fully cover the total amount of rent or may only partially do so. Social renters are also entitled to receive housing benefit if they pass the means test.

Table 4.b, which shows proportions of renters living in social housing, reveals that 81% of renters aged over fifty in Great Britain live in public rental accommodation (either local authority housing or housing association housing). The comparable fraction in the United States is only 27%. In Britain, there is little escape from the large role played by the public sector in the rental marker as this proportion varies from 60% to 90% across the regions. Of those living in social housing, around 50% also receive housing benefit (not shown in table).

Social renters have a severely reduced incentive and ability to move or to downsize their property for several reasons. Even if a tenant’s current circumstances means that they are still entitled to social housing, moving can be very difficult because of the shortage of social housing: existing tenants are treated in the same way as new applicants, so if they are not in a priority group they may not be allocated a different property. For those whose circumstances have changed in such a way that they would no longer be entitled to social housing if they were to reapply, there is a large incentive not to move as they may not be allocated a different property at all and may have to move into the private sector and pay full market rent.

Receiving housing benefit may also reduce the incentive to downsize. For tenants who receive housing benefit that fully meets the cost of the rent, moving into smaller or cheaper accommodation would reduce their housing consumption and would have no offsetting reduction in cost. The disincentive to move is somewhat reduced for renters who receive housing benefit that only partially covers the rent, although it is still present. Whilst a reduction in housing consumption would lead to a reduction in housing costs, this might not be a one-for-one reduction due to the partial subsidy.

Our multivariate analysis will control for both social renting and receipt of full or partial housing benefit subsidies. Table 5 highlights large mobility differences among British renters depending on whether they are a social or private renter and within these categories depending on the extent of the benefit subsidy. Social housing is highly correlated with mobility rates—37% of private renters move over a five-year period compared to only 16% of social renters. Among social renters, they least mobile are those who are receiving no social benefit and who presumably may have difficultly qualifying for a social flat if they moved. Care needs to be taken because there are many other differences across the various groups, not least in their average incomes. Hence further discussion will be left to the multivariate models of section four.

Table 5.

Mobility Among British Renters

| Renter Type | % of Renters | Prob of moving in five years |

|---|---|---|

| Social, no benefit | 36.8 | 0.14 |

| Social, partial benefit | 25.7 | 0.16 |

| Social, 100% benefit | 17.8 | 0.22 |

| All social renters | 80.3 | 0.16 |

| Private, no benefit | 10.3 | 0.35 |

| Private, partial benefit | 2.0 | 0.34 |

| Private, 100% benefit | 7.5 | 0.40 |

| All private renters | 19.7 | 0.37 |

Note: Social renters in Britain are those who live in public or Council housing. Private renters are those who live in private rental housing. We separate each group by whether they receive no housing benefit (a cash transfer to renters for housing), a partial benefit, or a 100% benefit.

Geographical mobility and the changes in amenities for movers

Even when older householders remain home owners and stay in a home of about the same size, they can purchase improved spatial amenities and lower their costs of living by moving to places where amenities are better and/or costs are lower. Once one moves to a new place and leaves the old, one buys the entire package of amenities and economic costs and benefits of the new location compared to the old. It is possible that one may gain in one dimension (a more pleasant climate) at the expense of another (a more affordable place to live).

In this section, we summarize results obtained from our analysis of the change in spatial amenities and economic costs associated with mobility among HRS and BHPS respondents who are at least 50 years old. Due to data limitations, these amenities can only be measured at the region (in Britain) or state (in the United States) level even though there are differences in amenities and economic costs associated with within-region and within-state moves, especially in the United States. Since the desire for better amenities and lower costs may be age dependent, we include in all models a set of age dummies for the age intervals 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80 plus. In these models the constant term is suppressed. The British data spans years 1991–2007 while the American data spans years 1969–2005.

In this analysis, our aim is simply to describe the nature of changes observed in the two datasets. However, due to the small number of moves observed, particularly across regions, in some country-age cells we want to be sure that any differences are statistically significant. Hence we estimated models with a discrete outcome—being either the change in amenity or economic cost associated with a move—and a set of categorical age dummies as explanatory variables. In addition, this allows us to make certain that our comparative results are not affected by secular trends given that the data in the two countries covers a different time period. We therefore include a dummy variable in the American models for the years 1991–2005, which are the years where BHPS data are available. That dummy variable is never statistically significant.

Table 6 summarizes our results for spatial amenities. We will illustrate our format with mean January temperature. A positive number in this table indicates that the area that a person left was colder than the area to which they moved—that is, a household was purchasing some additional warmth in the winter. Most of the American numbers in Table 6 are positive, indicating that on average American movers are going to warmer winter climates. Buying additional warmth during winter months is more common among those under 70 years old and is particularly large among those who move during the retirement years. Among those 60 to 70 years old, when most retirement-related moves take place in the United States, American across state movers ‘purchase’ six and half degrees Fahrenheit warmer winter climates. This may well be an understatement given the absence of data within states on amenities. Especially around the retirement age span and given the size of some American states, movers may well be heading for the warmer, more pleasant areas of the State which often are in the southern most parts. Not only is the new location more pleasant, winter heating costs are presumably lower in the new locale.

Table 6.

Change in U.S. and Britain Amenities Associated with Mobility across States or Regions, by Age

| American individuals who move states | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in | January temperature | Annual rainfall | Hours of January sunlight | |||

|

| ||||||

| coeff | t | coeff | t | coeff | t | |

|

|

||||||

| 50–59 | 2.679 | 2.80 | 1.149 | 1.43 | 8.860 | 2.81 |

| 60–69 | 6.526 | 6.18 | 3.057 | 3.41 | 16.704 | 4.78 |

| 70–79 | 1.140 | 0.76 | −0.947 | 0.74 | 9.098 | 1.84 |

| 80+ | −1.345 | 0.60 | −1.293 | 0.68 | −0.798 | 0.11 |

| 1991–2005 | −0.040 | 0.04 | 1.098 | 1.17 | −6.790 | 1.86 |

| British individuals who move regions

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in | January temperature | Annual rainfall | Hours of January sunlight | |||

|

| ||||||

| coeff | t | coeff | t | coeff | t | |

|

|

||||||

| 50–59 | −0.094 | −0.989 | 3.743 | 3.473 | −1.541 | −3.564 |

| 60–69 | 0.082 | 0.741 | 1.881 | 1.503 | −0.483 | −0.962 |

| 70–79 | 0.203 | 1.419 | −1.990 | −1.221 | 1.417 | 2.168 |

| 80+ | −0.259 | −1.150 | −7.177 | −2.798 | 1.615 | 1.569 |

Note: This table shows the estimated change in each location specific amenity associated with moves that are across states in the United States or across regions in Britain. The data used are the PSID for years 1969–2005 and the BHPS for years 1991–2007. The coefficients in each column are from separate models of each amenity with age bands as explanatory variables and the constant term suppressed. The American model adds a dummy for years 1991–2005 to make test whether there were significant time trends which there are not.

For those above age 70, and particularly over age 80, Americans actually move to slightly colder winter climates indicating that moves at very old age may reflect quite different motives, such as being closer to relatives (moving back to where relatives live) when elderly parents become increasingly frail and dependent. Sample sizes are also much lower at these older ages, making the patterns more erratic.

Not surprisingly in light of the data presented above in Table 4.b about the lack of variability in spatial amenities, our estimated models for Britain show virtually no relation between a region’s winter climate and the direction of a move. The estimated coefficients are never statistically significant and are as often negative as positive.

Rainfall does not appear to be an important amenity inducing across region or state migration. Annual rainfall generally tends not to be statistically significant. In the three cases where we do find an effect, those aged 60–69 in the US and 50–59 in Britain move towards slightly wetter climates, while those aged 80+ in Britain move away from such areas. Rainfall is a complicated amenity—while constant rain is not a desirable trait, hot dry summers (particularly in the US) are also associated with lower rainfall.

The other amenity that does appears to matter was hours of January sunshine.9 American movers across states apparently not only desire warmth but also sunlight. For people who move across state, January sunlight hours increase by almost seventeen hours in the retirement age span and about nine hours for movers in their fifties or seventies. Once again, this pattern disappears among the elderly where there is no improved sunshine for those over 80. In Britain, our model shows that once again there is little opportunity for gain for the British in terms of sunshine achieved through migration. In fact, among those in their fifties the days become a bit darker when people in Britain moved across regions.

We next consider in Table 7 changes in costs associated with the move by comparing average state housing and rental prices per room of the new location compared to the previous one. To avoid confusion in the units associated with switching between owner and rental prices when the move involves a change in tenure, prices in the destination location reflect the same type of tenure of the location of origin. To illustrate, if the move was from owner to renter, we compare mean state housing (as opposed to rental) prices in the two locations. To eliminate the confounding effect of housing price inflation, we compare origin and destination housing prices in the wave prior to the actual move. In addition to modeling these changes in cost per room by tenure status at location or origin, we also estimate models separately by whether the transition was to an owner or rental status.

Table 7.

Change in Costs Per Room Associated with Mobility across Regions or States

| United States | All Owners | Owners who remained owners | Owners who became renters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| coeff | t | coeff | t | coeff | t | |

|

|

||||||

| 50–59 | −27.1 | −0.04 | 127.8 | 0.13 | 158.1 | 0.14 |

| 60–69 | −1481.1 | −1.83 | −1871.3 | 1.91 | 856.9 | 0.49 |

| 70–79 | −678.5 | −0.64 | −391.9 | 0.25 | −582.9 | 0.38 |

| 80+ | −2297.4 | −1.42 | −1457.3 | 0.61 | −7094.0 | 2.91 |

| 1991–2005 | −7.3 | −0.01 | −194.4 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| United States | All renters | Renters who remained renters | Renters who became owners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| coeff | t | Coeff | t | coeff | t | |

|

|

||||||

| 50–59 | 120.1 | 0.89 | 196.9 | 1.18 | 77.1 | 0.25 |

| 60–69 | −70.7 | −0.48 | 55.9 | 0.29 | −187.3 | 0.60 |

| 70–79 | 180.7 | 0.72 | 221.7 | 0.74 | 61.7 | 0.09 |

| 80+ | −383.5 | −1.17 | −407.3 | 1.24 | NC | NC |

| 1991–2005 | −60.9 | −0.37 | −57.1 | 0.27 | −207.9 | 0.56 |

| Britain | All renters | Owners who remained owners | Owners who became renters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| coeff | t | Coeff | t | |||

|

|

||||||

| 50–59 | −3534.4 | −3.35 | −3589.5 | −3.20 | 750.8 | 0.29 |

| 60–69 | −3764.7 | −3.07 | −4192.0 | −3.38 | −396.5 | −0.12 |

| 70–79 | −272.5 | −0.16 | −1048.4 | −0.62 | (3600.2) | 0.82 |

| 80+ | (4089.38) | 1.33 | (1146.0) | 0.26 | (4472.8) | 1.00 |

| Britain | All renters | Renters who remained renters | Renters who became owners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| coeff | t | Coeff | t | Coeff | t | |

|

|

||||||

| 50–59 | 25.1 | 0.29 | −77.0 | −0.97 | (198.6) | 0.82 |

| 60–69 | −113.5 | −1.33 | −123.6 | −1.72 | (−198.5) | −0.60 |

| 70–79 | −75.9 | −0.74 | (−89.9) | −1.08 | (−18.6) | −0.05 |

| 80+ | (−48.3) | −0.27 | (−60.5) | −0.45 | NC | NC |

NC = no cases.

Note: This table lists the estimated change in location-specific housing costs associated with each move that was across states in the United States or across regions in Britain. When a move changes type of tenure (such as owner-renter or renter-owner) we evaluate the new location cost at the tenure type pre move. Individuals changing tenure from owning or renting to “other” are not reported as a separate group. To eliminate the confounding effect of housing price inflation, we compare origin and destination housing prices in the wave prior to the actual move. The data used are the PSID for years 1969–2005 and the BHPS for years 1991–2007. The coefficients in each column are from separate models of housing costs with age bands as explanatory variables and the constant term suppressed. The only explanatory variables are the age bands with the constant term suppressed. The American model adds a dummy for years 1991–2005 to make test whether there were significant time trends which there are not. Numbers in parentheses indicate cells with less than 10 cases.

In the US, homeowners in the retirement age span apparently move to less expensive places per room than those that they left, particularly when they remain owners. Owners who remain owners and who are moving across state boundaries are associated with average state costs about one thousand nine hundred dollars less per room. In contrast, there appears to be no real association with area specific costs per room among renters. Thus, holding the number of rooms constant, owners (but not renters) who migrate across state lines do appear to be moving to less expensive states.

Similar to the US, it appears that when British owners move when they are less than 70 years old, they also on average move to a less expensive region. Essentially at these ages, people are moving from the city (expensive) to the country (cheaper). Almost all of this effect is associated with moves where the person remained a home owner. In contrast, British renters who move experience no statistically significant cost change per room.

Especially in the United States, these location specific costs might include income or property tax changes which can vary considerably across states and localities. Property taxes are set at the local level in the United States so that they are outside the scope of our analysis. As described above, we computed average tax rates (combined federal and state) associated with a state for four different income levels with people assigned the income bracket closest to their actual income. Since taxes can change both due to a change in average income tax rates between the two locations or a change in income of the household, we evaluate the impact of changing taxes by holding income constant at the time of the move. By doing so, the pure impact of income tax rates can be isolated.

Table 8 lists changes in income tax rates associated with a move. For Americans over age 50 but under age 70, average state and federal taxes are lower after the move. The changes are relatively small—a little less than two percentage points. To some extent, the impact of income tax variation is undoubtedly understated in these computations due to the use of the only four income brackets to assign tax rates, it does not appear at present that this may not turn out to be a primary motive for migration in the pre-and post-retirement years. Once again reflecting a pattern seen before, this pattern reverses after age 70 when economic factors apparently play less of a role in the migration decision.

Table 8.

Change in U.S. Tax Rates Associated with Mobility Individuals Who Moved Across States

| Income Tax Rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| coeff | t | |||||

| 50–59 | −0.018 | −6.06 | ||||

| 60–69 | −0.018 | −5.42 | ||||

| 70–79 | −0.015 | −3.35 | ||||

| 80+ | 0.001 | 0.19 | ||||

| 1991–2005 | 0.002 | 0.66 | ||||

Note: Data used are the PSID for years 1969–2005. Coefficients reported are from a model for change in tax rates where the only explanatory variables are the age bands with the constant term suppressed and a dummy for the years 1991–2005. Average tax rates in the United States were obtained using the NBER Taxsim program evaluated at four real income levels ($20,000, $40,000, $60,000 and $80,000 in year 1995) and reflect the federal and state tax codes in each year. We assign an individual the average tax rate in that year closest to their annual family income in the year of the move for the origin and destination state.

In sum then, how would we characterize mobility in terms of the overall cost implications for housing consumption? We know from Figures 1 and 2 that that Americans, and to a much less extent the British, tend to downsize during these ages so that when they move they select smaller homes which by itself would make them cheaper. This is true for both owners and renters. This downsizing alone would imply that less housing is being consumed and less is being spent on housing. For Americans and British homeowners, especially if they remain owners as most do and are less than 70 years old, the price per room is also lower in the new location compared to the old augmenting the lower expenditures on housing for across region and state moves.

IV. MODELING MOBILITY AT OLDER AGES

In this section, we present our full empirical models of mobility at older ages in the US and Britain. Reflecting our discussions above, several factors hypothesized to be related to mobility at older ages are included in our analysis. These are conceptually organized into four groups—economic, family, location specific amenities, and institutional constraints—each of which potentially vary across our spatial units which will be States in the US and regions in Britain. Inter-state (or inter-region) migration is modeled separately from all moves.

Individual economic indicators in both countries include the ln of real annual family income and education. In the United States education is separated into three groups—13–16 years of schooling, 16 or more years of schooling with 12 or fewer years the reference group. In Britain, broadly comparable groups are constructed based on educational qualifications—the lowest education (reference) group are those with compulsory schooling only, the middle group has some post-compulsory schooling or vocational qualifications but less than a college degree, and the final group has college degrees or higher. The models also contain measures of individual values of baseline house value, the amount of home equity (for home owners only), and the average amount of inflation adjusted financial assets in the family.10

In addition to economic indicators measured at the individual level, our mobility models include measures of area specific housing costs—either mean rents per room (for renter models) or mean housing price per room (for the owner model). In the United States, we include a measure of the average income tax rates. As described above, these tax rates were computed based on year, state, and income of respondents.

The probability of moving may be related to work transitions especially those induced by retirement that take place at these ages. Therefore, a set of work transitions are entered into the models (work-no work, no work-work, no work-no work with work-work as the omitted category). All work variables are defined at the individual level but if the family unit is a couple, we include these work transitions for both partners.

Family related forces include whether there were any demographic transitions in the household in terms of marital status, whether any children are at home, and the number of people in the household. More specifically, all models have the following sets of demographic variables—a quadratic in age, the change in the number of people living in the house, three marital status transitions (married-single, single-married, single-single with married-married as the omitted group), and children living at home transitions (kids-no kids, no kids-kids, no kids-no kids with kids-kids as the omitted group11). The marital and child transition indicators tell us, conditional on changes in number of residents, whether changes in the type of resident living in the home matters.

While neither PSID nor BHPS have extensive measures of health, they do measure health status along the standard five point scale—excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor.12 Using this information, we construct two variables about health change between the waves of the panel—whether your general health status improved and whether your general health status got worse. The reference group is that your health status remained the same.

Based on our results above, our amenity measure is mean temperature in January. Institutional factors are meant to capture institutional arrangements in the two countries that may promote or inhibit mobility at older ages particularly among renters—whether one lives in public or subsidized housing (in the US) or in council housing in Britain. All area specific variables are interacted with age being at least 70 to gauge whether the influence of such factors vary with age.

Data used for estimation are based on a sample of individuals ages 50 and more using the PSID for the US (years 1968–2005) and the BHPS for Britain (years 1991–2007.)13 Separate models were estimated for owners and renters and all models include a linear time trend. Tables 9 and 11 (for owners) and Tables 10 and 12 (for renters) list estimated coefficients and associated z statistics obtained from OLS models of three types of migration decisions in the US and Britain—the probability of changing residence (regardless of destination), the probability of moving across a state or region boundary, and the conditional probability of moving across a state or region boundary given that you relocate. All decisions are modeled over a one year time frame.

Table 9.

OLS Models of the Probability of Moving Between Waves—United States One Year Horizon—Owners

| Any mobility | Cross-state mobility | Cross-state mobility if a mover | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Coeff | z | Coeff | z | Coeff | z | |

|

|

||||||

| Education 13–15 baseline | .00935 | 3.52 | .00382 | 2.71 | .02686 | 1.34 |

| Education ≥ 16 baseline | .01277 | 4.83 | .00668 | 4.44 | .05181 | 2.46 |

| Year at baseline | .00092 | 7.36 | .00025 | 3.71 | −.00245 | 2.92 |

| Age | −.00283 | 9.16 | −.00016 | 1.10 | .00442 | 2.06 |

| Age squared | .00009 | 8.96 | 3.99e-06 | 0.99 | −.00015 | 2.87 |

| ≥ age 70 | −.01734 | 1.91 | −.01226 | 2.44 | −.07600 | 0.98 |

| ln income at baseline | .00633 | 4.80 | .00420 | 7.40 | .02880 | 3.55 |

| Negative income | .06335 | 4.44 | .03590 | 6.18 | .28156 | 3.42 |

| Married/single | .12619 | 11.68 | .02005 | 4.23 | −.01193 | 0.41 |

| Single/married | .28088 | 11.89 | .04638 | 4.04 | −.02364 | 0.67 |

| Single/single | .02682 | 10.70 | .00464 | 4.09 | −.01040 | 0.52 |

| Kids/no kids | .04941 | 5.37 | .01466 | 3.10 | .07734 | 1.90 |

| No kids/kids | .03728 | 5.02 | .00471 | 1.39 | .01393 | 0.26 |

| No kids/no kids | .02359 | 8.49 | .00652 | 4.43 | .00980 | 0.37 |

| Change in household size | −.01247 | 5.24 | −.2.42e-06 | 0.00 | .01511 | 2.53 |

| Work/not work | .04035 | 8,94 | .02130 | 7.60 | .13246 | 4.80 |

| Not work/work | .01793 | 3.29 | .01216 | 3.82 | .13948 | 3.34 |

| Not work/not work | .01337 | 6.50 | .00821 | 7.60 | .08785 | 4.79 |

| Partner Work/not work | .03435 | 7.01 | .02002 | 6.19 | .13414 | 3.77 |

| Partner Not work/work | .00990 | 1.82 | .00713 | 2.18 | .06714 | 1.24 |

| Partner Not work/not work | .01281 | 6.27 | .00561 | 5.31 | .02178 | 1.07 |

| ln house value (baseline) | .00477 | 2.82 | .00147 | 1.98 | .00309 | 0.33 |

| ln home equity (baseline) | −.01575 | 9.76 | −.00350 | 4.74 | −.00031 | 0.04 |

| (Have negative home equity) | −.05860 | 9.07 | −.01555 | 5.46 | −.00748 | 0.23 |

| Average financial assets | 1.07e-06 | 0.57 | −1.97e-06 | 3.36 | −.00004 | 5.51 |

| ≥70 x Average financial assets | −4,30e-06 | 0.90 | 2.07e-06 | 1.08 | .00003 | 1.38 |

| Health got better | .00617 | 1.94 | .00136 | 0.79 | 01583 | 0.48 |

| ≥70 x Health got better | −.00408 | 0.69 | −.00110 | 0.36 | .04930 | 0.82 |

| Health got worse | −.00045 | 0.15 | .00082 | 0.50 | .00329 | 0.10 |

| ≥70 x Health got worse | −.00155 | 0.29 | −.00337 | 1.24 | −.02229 | 0.41 |

| Mean January temperature | .00024 | 2.79 | −.00006 | 1.41 | −.00227 | 3.33 |

| ≥70 x Mean January temp | .00028 | 1.63 | .00019 | 2.08 | .00224 | 1.78 |

| Cost of housing per room | 7.56e-07 | 4.67 | 1.59e-07 | 1.85 | 3.12e-06 | 2.37 |

| ≥70 x Cost of housing per room | 7.44e-08 | 0.26 | 3.27e-07 | 1.95 | −3.64e-07 | 0.17 |

| Average tax rate | .02219 | 1.25 | .00999 | 1.23 | .30021 | 2.10 |

| ≥ 70 x Average tax rate | −.04341 | 1.19 | −.00451 | 0.22 | .04347 | 0.14 |

| Public or subsidized housing | −.01031 | 2.19 | −.00138 | 0.55 | −.00949 | 0.23 |

| ≥70 x Public or sub housing | .00659 | 0.66 | .00354 | 0.64 | .02677 | 0.32 |

| Constant | −.06330 | 4.57 | −.04815 | 7.51’ | −.16988 | 1.83 |

Table 11.

OLS Models for Mobility of Owners—Britain (One Year Horizon—Owners)

| Prob Moving | Prob Move X region | Conditional X Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educated to A-level standard | .00748 | 2.44 | .00186 | 1.28 | .01254 | 0.31 |

| Educated to Higher Education level | −.00479 | −1.74 | .00113 | 0.87 | .09343 | 2.30 |

| Year at baseline | .00047 | 0.83 | −.00019 | −0.72 | −.00668 | −0.73 |

| Age | −.00688 | −4.95 | −.00200 | −3.03 | −.00796 | −0.39 |

| Age squared | .00005 | 4.56 | .00001 | 2.70 | .00005 | 0.31 |

| ≥ age 70 | −.07609 | −0.63 | −.04165 | −0.73 | −.49904 | −0.26 |

| ln income at baseline | −.00190 | −1.03 | −.00037 | −0.43 | −.00469 | −0.20 |

| Negative income | −.01811 | −0.49 | ||||

| Married/single | .05279 | 5.72 | .00867 | 1.98 | −.11392 | −1.31 |

| Single/married | .26011 | 14.26 | .04748 | 5.49 | −.13425 | −1.45 |

| Single/single | .01126 | 4.43 | .00037 | 0.31 | −.05996 | −1.62 |

| Kids/no kids | .02004 | 2.05 | .00494 | 1.06 | .09259 | 0.72 |

| No kids/no kids or No kids/kids | .01139 | 2.31 | .00593 | 2.54 | .10367 | 1.37 |

| Change in household size | .00660 | 2.48 | .00154 | 1.22 | −.00213 | −0.10 |

| Work/not work | .03184 | 6.80 | .01873 | 8.43 | .22597 | 4.26 |

| Not work/work | .00993 | 1.56 | .00498 | 1.65 | .15652 | 1.84 |

| Not work/not work | .00906 | 3.26 | .00699 | 5.30 | .13912 | 3.34 |

| Partner Work/not work | .03091 | 6.21 | .01698 | 7.19 | .18072 | 3.00 |

| Partner Not work/work | .00358 | 0.53 | .00581 | 1.82 | .21188 | 2.36 |

| Partner Not work/not work | .00827 | 3.01 | .00499 | 3.83 | .10856 | 2.53 |

| Ln House Value (baseline) | .02432 | 5.81 | .00450 | 2.27 | .01170 | 0.22 |

| ln home equity (baseline) | −.02078 | −5.74 | −.00351 | −2.04 | −.00174 | −0.04 |

| Have negative home equity | −.22404 | −5.25 | −.03598 | −1.78 | −.21004 | −0.42 |

| Average financial assets £’000 | −.00004 | −1.57 | −.00002 | −2.13 | −.00034 | −0.99 |

| ≥ 70 x Average financial assets | .00009 | 2.32 | .00005 | 2.73 | .00081 | 1.46 |

| Health got better | −.00237 | −0.79 | −.00107 | −0.75 | .01754 | 0.40 |

| ≥ 70 x Health got better | .00172 | 0.33 | .00261 | 1.05 | .04447 | 0.54 |

| Health got worse | −.00045 | −0.15 | −.00131 | −0.90 | −.01847 | −0.43 |

| ≥ 70 x Health got worse | .00905 | 1.62 | .00435 | 1.65 | .02634 | 0.34 |

| Mean January temperature | −.00247 | −1.38 | −.00114 | −1.34 | −.00484 | −0.19 |

| ≥70 x Mean January temp | .00173 | 0.60 | .00094 | 0.68 | .01409 | 0.31 |

| Cost of housing per room, £annual | 2.57E-07 | 1.36 | 6.36E-07 | 7.07 | 1.74E-05 | 6.68 |

| ≥70 x Cost of housing per room | −2.16E-07 | −0.79 | −3.95E-07 | −3.03 | −1.10E-05 | −2.62 |

| Band council tax rate in region | .00000 | −0.29 | −1.65E-05 | −2.16 | −.00057 | −2.15 |

| ≥ 70 x Band council tax rate | −5.23E-06 | −0.46 | 5.74E-06 | 1.05 | .00025 | 1.33 |

| % in Local Authority housing | −.03257 | −2.69 | −.00160 | −0.28 | .34538 | 1.87 |

| ≥70 x % in Local Authority housing | .01340 | 0.60 | .00799 | 0.75 | −.04767 | −0.14 |

Table 10.

OLS Models of the Probability of Moving Between Waves—United States One Year Horizon—Renters

| Any mobility | Cross-state mobility | Cross-state mobility if a mover | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Coeff | z | Coeff | z | Coeff | z | |

|

|

||||||

| Education 13–15 baseline | .04092 | 3.86 | .00348 | 0.85 | .00759 | 0.46 |

| Education ≥ 16 baseline | .03031 | 2.28 | .02254 | 3.32 | .05930 | 2.33 |

| Year at baseline | .00460 | 10.50 | .00059 | 3,68 | −.00022 | 0.36 |

| Age | −.00600 | 6.66 | −.00034 | 1.05 | .00167 | 1.07 |

| Age squared | .00007 | 3.23 | .00001 | 1.37 | −.7.67e-06 | 0.19 |

| ≥ age 70 | .03833 | 1.26 | .00287 | 0.27 | −.03458 | 0.57 |

| ln income at baseline | .01350 | 3.78 | .00578 | 4.40 | .01345 | 2.13 |

| Negative income | .08054 | 2.34 | .05166 | 4.23 | .15259 | 2.52 |

| Married/single | .22107 | 8.03 | .03366 | 2.48 | .00935 | 0.28 |

| Single/married | .28464 | 8.22 | .03613 | 2.35 | .02945 | 0.87 |

| Single/single | .01593 | 1.93 | .00381 | 1.33 | .00270 | 0.19 |

| Kids/no kids | .17973 | 5.53 | .01898 | 1.40 | .00213 | 0.07 |

| No kids/kids | .06181 | 2.58 | .02443 | 2.40 | .08001 | 1.94 |

| No kids/no kids | .04162 | 3.67 | .01726 | 4.58 | .04877 | 2.84 |

| Change in household size | −.00861 | 1.56 | −.00476 | 1.59 | −.01209 | 1.55 |

| Work/not work | .12031 | 7.95 | .04781 | 6.06 | .11729 | 4.91 |

| Not work/work | .08075 | 4.20 | .02693 | 3.14 | .06482 | 2.27 |

| Not work/not work | .03203 | 4.30 | .01257 | 4.61 | .03904 | 2.87 |

| Partner Work/not work | .07355 | 3.04 | .04169 | 3,20 | .10819 | 2.54 |

| Partner Not work/work | .03852 | 1.36 | .05365 | 3.00 | .18862 | 3.06 |

| Partner Not work/not work | −.09933 | 1.02 | .00542 | 1.49 | .02888 | 1.43 |

| Average financial assets | .00010 | 2.57 | .00004 | 2.18 | .00001 | 0.25 |

| ≥ 70 x Average financial assets | −.00007 | 0.94 | −.00003 | 1.32 | .00002 | 0.21 |

| Health got better | .03135 | 2.21 | −.00049 | 0.09 | −.02110 | 0.88 |

| ≥ 70 x Health got better | −.00924 | 0.44 | .00591 | 0.75 | .05566 | 1.27 |

| Health got worse | .00621 | 0.47 | −.00247 | 0.48 | −.01634 | 0.66 |

| ≥ 70 x Health got worse | .01867 | 0.97 | .00887 | 1.24 | .02905 | 0.78 |

| Mean January temperature | .00187 | 5.50 | .00018 | 1.44 | −.00032 | 0.61 |

| ≥70 x Mean January temp | −.00148 | 2.53 | −.00005 | 0.23 | .00111 | 1.02 |

| Cost of housing per room | −1.69e-06 | 1.23 | 6.14e-07 | 0.34 | 2.73e-06 | 0.40 |

| ≥70 x Cost of housing per room | .00001 | 1.76 | −1.05e-07 | 0.04 | −3.87e-06 | 0.33 |

| Average tax rate | −.25411 | 3.67 | .06372 | 2.23 | .58293 | 4.07 |

| ≥ 70 x Average tax rate | −.17583 | 1.23 | −.11112 | 2.07 | −.47822 | 1.37 |

| Public or subsidized rent | −.02048 | 0.99 | .01122 | 1.33 | .04268 | 1.20 |

| ≥70 x Public or sub rent | .05703 | 1.62 | −.01481 | 1.17 | −.07370 | 1.06 |

| Public or subsidized housing | −.05294 | 5.04 | −.01318 | 4.40 | −.04159 | 2.57 |

| ≥70 x Public or sub housing | 00646 | 0.42 | .00962 | 2.06 | .01626 | 0.58 |

| Constant | −.11806 | 2.80 | −.08888 | 5.61 | −.15780 | 2.23 |

Table 12.

OLS Models for Mobility of Renters—Britain (One Year Horizon—Renters)

| Any mobility | Cross-region mobility | Cross-Region if a mover | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educated to A-level standard | .03228 | 2.84 | .00591 | 1.61 | .02187 | 0.46 |

| Educated to Higher Education level | .04314 | 3.72 | .02003 | 5.35 | .14182 | 2.78 |

| Year at baseline | −.00079 | −0.60 | −.00081 | −1.90 | −.01232 | −1.54 |

| Age | −.00663 | −2.45 | .00010 | 0.11 | .00450 | 0.31 |

| Age squared | .00005 | 2.53 | .00000 | −0.17 | −.00004 | −0.36 |

| ≥ age 70 | .25157 | 0.98 | .16672 | 2.01 | 1.25875 | 0.79 |

| ln income at baseline | .01035 | 1.96 | .00157 | 0.92 | −.02145 | −0.81 |

| Negative income | .12573 | 1.64 | ||||

| Married/single | .07178 | 3.52 | −.01373 | −2.09 | −.18870 | −2.26 |

| Single/married | .25159 | 6.51 | −.00207 | −0.17 | −.04662 | −0.47 |

| Single/single | .00023 | 0.04 | −.00286 | −1.70 | −.05126 | −1.57 |

| Kids/no kids | .01426 | 0.54 | −.00325 | −0.38 | −.05158 | −0.42 |

| No kids/no kids or No kids/kids | .00237 | 0.19 | .00654 | 1.59 | .05347 | 0.85 |

| Change in household size | .02619 | 3.84 | −.00331 | −1.50 | −.01611 | −0.78 |

| Work/not work | .05400 | 3.96 | .01219 | 2.76 | .03450 | 0.61 |

| Not work/work | .01077 | 0.62 | −.00377 | −0.67 | −.04025 | −0.45 |

| Not work/not work | .01396 | 1.79 | .00226 | 0.90 | .00569 | 0.13 |

| Partner Work/not work | .06453 | 3.97 | .01900 | 3.62 | .03093 | 0.49 |

| Partner Not work/work | .03958 | 1.94 | −.00465 | −0.70 | −.02483 | −0.29 |

| Partner Not work/not work | −.00341 | −0.40 | .00010 | 0.04 | −.00732 | −0.15 |

| Average financial assets £’000 | −.00007 | −0.85 | .00002 | 0.86 | .00015 | 0.24 |

| ≥ 70 x Average financial assets | −.00025 | −1.60 | −.00005 | −0.93 | .00229 | 0.85 |

| Health got better | .00295 | 0.37 | .00088 | 0.34 | .00855 | 0.20 |

| ≥ 70 x Health got better | .01023 | 0.91 | −.00145 | −0.40 | −.01311 | −0.19 |

| Health got worse | .01038 | 1.30 | .00228 | 0.88 | .01917 | 0.46 |

| ≥ 70 x Health got worse | .00774 | 0.67 | .00144 | 0.38 | .03939 | 0.59 |

| Mean January temperature | .00975 | 2.21 | .00364 | 2.55 | .02730 | 1.13 |

| ≥70 x Mean January temp | −.00795 | −1.28 | −.00376 | −1.88 | −.02600 | −0.69 |

| Cost of housing per room, £ annual | .00000 | −0.96 | .00000 | 4.06 | .00001 | 4.47 |

| ≥70 x Cost of housing per room | .00000 | 0.95 | .00000 | −0.34 | .00000 | 0.59 |

| Band council tax rate in region | 4.48E-05 | 1.14 | 9.33E-06 | 0.73 | −5.29E-05 | −0.23 |

| ≥ 70 x Band council tax rate | −2.26E-05 | −1.15 | −9.01E-06 | −1.42 | −.00017 | −1.46 |

| % in Public or subsidized housing | −.07888 | −2.35 | .03568 | 3.28 | .68438 | 4.05 |

| ≥70 x % in Public or sub housing | .04051 | 0.82 | −.02313 | −1.46 | −.28481 | −0.98 |

| Local authority renter | −.07701 | −9.46 | −.00571 | −2.17 | −.00753 | −0.19 |

| 100% HB recipient | −.02368 | −2.23 | .01215 | 3.54 | .11840 | 2.77 |

| Partial HB recipient | −.02922 | −1.69 | −.00533 | −0.95 | −.02203 | −0.29 |

| 100% HB recipient*LA renter | .04789 | 3.82 | −.00645 | −1.59 | −.03486 | −0.58 |

| Partial HB recipient*LA renter | .03941 | 2.19 | .00910 | 1.56 | .07897 | 0.95 |

If we examine first the set of transition variables included in the model for the US (marriage, kids, and work), the stable no transition reference group (married-married, kids-kids, and work-work) is generally the one least associated with mobility for both owners and renters alike. The transition into marriage generates the highest probability of a move, both within and across state moves. For Britain, a very similar pattern is found in that the most stable reference group is generally least likely to move, but the impacts of the marital transitions on mobility are typically quite smaller.

All ‘kids’ transitions motivate additional mobility both within and across states for renters and owners alike in the US. Especially for owners, the transition from no kids to kids in the home is associated with a move across states and for higher induced mobility (compared to the other types of kids transitions) for renters. This is most likely due to parents moving to their child’s home and place of residence as they get older. The effect of these children transitions is once again similar in Britain but not as pronounced.

Work transitions also generate mobility both within and across states for both renters and owners in the US and in Britain. This is the case for one’s own work transition and those of one’s spouse or partner. The transition from work to non-work by either partner, which in this age group is most likely associated with retirement, induces households to move across state and region boundaries, presumably as the link between place of work and place of residence is broken. We find little systematic association of changes in health with mobility in either country although it is important to remember that the measurement of health is not a strength of either the PSID or BHPS.

We next describe estimated impacts of economic variables. Several dimensions of economic resources are measured, including household income, education, house value and home equity among home owners, and average financial wealth holdings. In the United States, statistically significant positive effects on the probability of moving are estimated for education and income, and higher incomes and more schooling are also more likely to generate inter-states moves in the US. Given the phase of the life-cycle we are examining, income is mostly not a proxy for job market opportunities in alternative labor markets. Instead these income effects are more likely to capture the ability to finance moves or to purchase amenities associated with localities that are no longer tied to jobs.

While average financial assets among American home-owners do not appear to be related to within State moves, more financial assets discourage across state moves. One interpretation may be that home-owners with little financial liquidity (controlling for net equity in their home), relocate in order to achieve greater financial liquidity. We find the same effect for across region moves of home owners in Britain and in both countries this effect is mitigated among older people. Greater financial assets encourage renter mobility in the United States but have no association with mobility in Britain.

In Britain, economic status variables—schooling and income—are far less important for mobility outcomes than in the US. We find a significant positive effect of education on the probability of moving but only for renters. There is no income effect on the probability of moving, either unconditionally or conditionally, for owners or renters alike.

Conditional on being a homeowner, mobility rises with the value of the house but declines with home equity when both variables are in the model both in the US and Britain. One interpretation of the home value effect (in addition to a normal income effect) is that as the value of home goes up people are consuming a lot of housing relative to their income, inducing them to want to downsize their house. Conditional of the value of house, an increase in home equity is equivalent to a reduction in the stock and flow of mortgage payments, which makes it less likely that people move to reduce those payments. In both countries, these house value variables do not affect whether or not the move is inter or intra-state (with the exception of a possible positive effect of ln house value on probability of moving regions in Britain).

There are several indicators of the economic costs associated with living in one’s current location—average income tax rate (US only), council tax rate,14 cost of housing per room (house price per room for owners and rental price per room for renters), and the fraction of rental residents of that state who live in public or subsidized housing. Based on transitions tables discussed above, all variables are interacted with whether the respondent was 70 years old or older.

Among owners, higher state or region wide cost per room encourages additional mobility and makes it more likely that the move is across states in the United States or regions in Britain. These effects become smaller in Britain and for those over 70 years old. Among renters in both countries these effects are weaker with the only statistically significant effect being that high rental costs per room encourage mobility across regions among British renters.

Conditional on moving, a high income tax in the origin state encourages additional across state mobility among owners. Renters in high tax states are discouraged from moving, although once again if they do move it will be across state.

Finally, a larger fraction of state rental units in public or subsidized housing discourages mobility in the US, although this effect is quite small. In Britain, for owners, the fraction living in public housing (local authority housing) in a region has a negative effect on the probability of moving. For renters, the proportion living in public housing in the region also discourages mobility, but it has a positive effect on the probability of moving region both unconditionally and conditionally. When an area is dominated by public housing which is often characterized by long queues, it may be very difficult to find alternative rental properties unless one is willing to move from the region.

Given our previous discussion about the possible effect of housing benefit and social renting on mobility, we also include individual level dummies in the rental models to indicate whether the individual is a Local Authority renter or a housing benefit recipient at either the full 100% rate or a partial rate. It is possible (and indeed common) for individuals to live in local authority housing and receive housing benefit. The mobility effect of receiving housing benefit in the private sector may be different (where the effect on mobility may be smaller, particularly for those receiving partial housing benefit), so we also include interactions of receipt of housing benefit and being a Local Authority (LA) renter.

Looking first at the effect of being an LA renter on mobility we can see that, as expected, being a social renter is strongly negatively associated with moving both within and across regions. This effect is mitigated to some extent if the social renter also receives a 100% housing benefit or a partial housing benefit. Recipients of such housing benefits typically have low current incomes and would have less difficulty qualifying for social council housing in another place if they did move. For renters in the private sector, receiving 100% housing benefit discourages mobility overall, but encourages cross-region mobility. Those receiving 100% housing benefit have no incentive to downsize as they will be consuming less housing with no offsetting reduction in cost. This would explain the negative effect on overall mobility. Private market rental coupled with receipt of partial housing benefit is not statistically significantly associated with differential mobility, which accords with our earlier discussion that the negative incentive to downsize is much less when rent is only partially covered by housing benefit.

The estimated impacts of amenity variables are more mixed, with only the January temperature measure indicating consistent results. In the US higher January temperature deters mobility across states, but only for those less than 70, with much stronger effects for owners than for renters. For moves which do not go across state boundaries, higher January temperature actually encourages mobility for renters and owners alike. As expected, these temperature-related effects are much weaker in Britain.

V. CONCLUSIONS

Housing wealth is a major component of individual retirement resources, and the dynamics of housing wealth trajectories at older ages are not well understood. But housing is also durable good providing, for homeowners at least, consumption services both contemporaneously and in the future. Consequently wealth trajectories need to be analyzed somewhat differently to other forms of wealth where one might naturally expect individuals to run down their wealth as they age in order to finance consumption in retirement.

When looking at trajectories of housing consumption (as measured by number of rooms) or housing wealth, differences between the US and Britain are driven not so much by differences in behavior of movers, but by differences in proportions of households who move. In this paper, we have investigated possible causes of these mobility differences, whether these be constraints in terms of the possible improvements that could be had by moving (in terms of climate etc.) or disincentives to move that may be inherent in the various national and state-level economic institutions.

We found a role for geographic, demographic, economic, and social factors that was surprisingly consistent across countries. In each case, the magnitude of the underlying variation in factors within each country leads to less housing mobility in Britain than the US. For example, whilst subsidized housing disincentivizes mobility in both countries, the higher proportion of subsidized renters in Britain (combined with a greater marginal effect of subsidized renting on mobility) leads to considerably less mobility in Britain. Similarly, while living in a colder or darker region leads to more mobility at older ages in both countries. The fact that regions differ by only one or two degrees (or one or two hours of sunshine) in Britain again leads to less mobility for older British households than for their American counterparts where state climate variation is much larger.

One obvious omission from our analysis is a measure of geographical proximity to other members of the family, and in particular children and grandchildren. While we do not have information on this in the individual level data we use in our analysis, the international differences are likely to be such that this would be in line with other effects we find. There is less geographical mobility at younger ages in Britain than there is in the US, and thus older adults are already closer to their families and their children’s families in their working years. Hence if geographical proximity to family is a motivation for mobility at older ages, then it is likely to lead to more mobility in the US than in Britain.