Abstract

The contributing role of stereotype threat (ST) to learning and performance decrements for stigmatized students in highly evaluative situations has been vastly documented and is now widely known by educators and policy makers. However, recent research illustrates that underrepresented and stigmatized students’ academic and career motivations are influenced by ST more broadly, particularly through influences on achievement orientations, sense of belonging, and intrinsic motivation. Such a focus moves conceptualizations of ST effects in education beyond the influence on a student’s performance, skill level, and feelings of self-efficacy per se to experiencing greater belonging uncertainty and lower interest in stereotyped tasks and domains. These negative experiences are associated with important outcomes such as decreased persistence and domain identification, even among students who are high in achievement motivation. In this vein, we present and review support for the Motivational Experience Model of ST, a self-regulatory model framework for integrating research on ST, achievement goals, sense of belonging, and intrinsic motivation to make predictions for how stigmatized students’ motivational experiences are maintained or disrupted, particularly over long periods of time.

Keywords: stereotype, stereotype threat, motivation, self-regulation, interest, belonging

Introduction

“Our research on stereotype threat began with a practical question: Do social psychological processes play a significant role in the academic underperformance of certain minority groups, and if so, what is the nature of those processes?” (Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002, p. 379). After nearly 20 years of research on stereotype threat it is clear that, yes, social situational forces play a significant role in shaping the test performance of students who are the targets of competence stereotypes (Inzlicht & Schmader, 2012). The worry of confirming a negative stereotype undermines students’ performance on high stake exams; and this experience is called “stereotype threat” (ST). Research has clarified the cognitive processes underlying ST effects on learning and performance (for reviews see Appel & Kronberger, 2012; Ryan & Ryan, 2005; Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008; Spencer, Logel, & Davies, in press; Smith, 2004; Wheeler & Petty, 2001) and numerous interventions are in place to combat such ST performance decrements (Cohen, Purdie-Vaugns, & Garcia, 2012; Yeager & Walton, 2011). Yet, even when gaps in performance are experimentally neutralized or statistically accounted for, stigmatized students who are highly skilled and performing objectively well are still significantly more likely than non-stigmatized students to avoid or switch out of stereotype-related majors (Davies, Spencer, Quinn, & Gerhardstein, 2002; LeFevre, Kulak, & Heymans, 1992) and are less likely to engage in stereotype-related career pursuits (Lubinski & Benbow, 2006). Even in domains for which ability stereotypes have been successfully refuted (such as women’s experience with math; Else-Quest, Hyde, & Linn, 2010), the message to stigmatized students is “while you can do it, you shouldn’t” (AAUW, 2001, p. 12). Thus, it is time for theory and research on the “academic underperformance” that Steele and colleagues set out to understand to move beyond understanding test performance and ability per se, and more programmatically focus on the motivational processes that stigmatized students experience in the face of ST. The purpose of this review is to present an overview of such scholarship and offer a theoretical marriage of the self-regulation of motivation literature within the social identity threat framework.

ST is a specific type of social identity threat. Drawing from Social Identity Theory, it is well understood that people strive to maintain a positive perception of their groups and collectives (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). If these positive perceptions are challenged, a sense of threat arises. People who feel that one of their social identities is potentially devalued experience “social identity threat” which can be triggered in a variety of ways (e.g., Logel et al., 2009) in a variety of settings (Murphy & Taylor, 2011) and result in a variety of negative outcomes (Steele et al., 2002). Social identity threats can prompt people to treat others (Bushman & Baumeister, 2008), and even themselves (Allen & Smith, 2011; Logel et al., 2009; Smith & Lewis, 2009), in a manner consistent with group stereotypes. When social identity threat is triggered by a competence based stereotype in an achievement setting a person experiences concern about being judged by or confirming the ability stereotype; this experience is “stereotype threat” (Steele & Aronson, 1995; Steele, 1997).

As of September 2012, over 200 empirical studies exist illustrating the deleterious effects of ST on students’ performance (for reviews see Appel & Kronberger, 2012; Logel, Walton, Spencer, Peach, & Zanna, 2012; Nadler & Clark, 2011; Nguyen & Ryan, 2008; Walton & Spencer, 2009), although some still question the robustness of these findings (Sackett, Hardison, & Cullen, 2004; Stoet & Geary, 2012). Much is known about the moderators (for a review see Nguyen & Ryan, 2008) and mediating processes of ST effects on performance (for reviews see Smith, 2004; Schmader et al., 2008). Much less is known about the motivational processes and outcomes associated with ST experiences. However, attention from educational and social psychological researchers has recently begun to shift toward the broader context of ST and the motivational implications for students. Although most motivational researchers in educational psychology recognize that student motivation is best understood in the context of self-regulated learning processes (Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006; Schunk & Zimmerman, 1994; Wolters, 2003; Zimmerman, 2000), ST research primarily examines motivations as relatively static outcomes. This discontinuity between the self-regulated learning theories in educational psychology and the ST research likely developed because seminal ST research was grounded in theory and research paradigms from experimental social psychology (e.g., Steele & Aronson, 1995).

Now that educational researchers are examining ST effects on students’ educational motivations, we aim to integrate findings of motivational processes that follow from ST within the broader framework of self-regulation models from educational psychology that explicate the dynamic processes involved in student learning and motivation. We also expand the focus of ST theory beyond high stakes testing situations to daily educational experiences and choices. In doing so, this work demonstrates that ST can be triggered by a variety of situational cues in everyday educational contexts, in addition to those that occur prior to or during testing situations. More than 40 published papers (many with multiple studies) now demonstrate numerous effects of ST beyond performance, on a number of motivational variables that have long been important to the field of educational psychology. However, no theoretical framework integrates these varied effects of ST on students’ motivation, and most studies investigate ST effects on a single outcome. The result is a growing body of research on motivational effects of ST that appears disparate in the literature without clear integration, perhaps obfuscating the broader picture of motivational implications of ST from most teachers, educational stakeholders, and policy makers.

The aim of this paper is twofold. We first review the research literature demonstrating how ST affects motivational constructs relevant to educational and achievement pursuits. Second, we propose and review support for the Motivational Experience Model of Stereotype Threat, a new self-regulatory model framework for integrating research on stereotype threat, achievement goals, sense of belonging, and intrinsic motivation to make predictions about how stigmatized students’ motivational experiences are maintained or disrupted, particularly over long periods of time. In doing so, we aim to synthesize much of the research on motivational effects of ST, situate this work within the broader context of the self-regulated learning literature, highlight areas where new predictions can be derived from this integration and where research is needed, and suggest how intervention strategies can be designed to ameliorate effects of ST at particular points in the model that may be most relevant at different points in time.

Review of research on stereotype threat and educational motivations

We review the burgeoning literature of ST effects on educational motivations by describing studies that demonstrate relationships between ST and students’ adoption of achievement avoidance orientation, sense of belonging, situational interest, domain identification, and students’ career motivation and intentions. Variable definitions and measurement across studies create overlap across these categories, and although other categories of motivational outcomes could have been created, these represent the most prominently studied relevant variables in the literature and those most central to our Motivational Experiences Model of ST. We identified the significance of these variables on the basis of theoretical relevance and available empirical findings, and our review includes all studies identified through literature search conducted in PsychInfo through September 2012 demonstrating relationships between ST and these motivational variables. We do not review ST research on learning, competence, effort, and efficacy because these findings have been covered in previous reviews (Appel & Kronberger, 2012; Smith, 2004), and we focus our review on the motivational variables most central to the proposed model. In addition to examining the outcomes of ST, a handful of studies reviewed below examine the mediational processes of more than one of our review variables. It is noteworthy that some review sections are considerably longer than others, and this reflects the amount of work that has examined ST effects on different outcomes. Although we identified over 40 published papers (many with multiple studies) that demonstrate effects of ST on motivation, specific motivational variables have received more attention than others as an outcome of ST. The dearth of literature review in some areas suggests where data are limited in the field and more scholarship is needed.

The review includes both applied and experimental studies; ST has been measured and manipulated in a number of ways. The focus of our review is on the effects of ST on motivation, rather than how it is triggered per se (for more complete discussion of how ST is triggered see Logel et al., 2009; Murphy & Taylor, 2011). Although in describing the research it is often helpful to include information about how ST was measured or manipulated, the primary focus of this review is on details of the motivational outcomes most relevant to education and to our Motivational Experiences Model of ST, which is described after the review of evidence for relationships between ST and students’ adoption of achievement avoidance orientation, sense of belonging, situational interest, domain identification, and students’ career motivation and intentions.

Review of research on stereotype threat and avoidance achievement orientation

A student’s orientation toward achievement is more than just a level of achievement motivation (as high or low, Elliot & Church, 1997; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1994; Harackiewicz & Elliot, 1993; Jackson, 1974); it is also a function of the type of achievement orientation a student adopts for a particular assignment or activity. The particular performance-goal orientation a student adopts, for example, can be delineated as either fear of underperforming/ working to avoid failure (avoidance) or working toward success and doing well (approach; e.g., Elliot, 1999; Harackiewicz, Durik, Barron, Linnenbrink-Garcia, & Tauer, 2008). Research is replete with evidence that performance-avoidance goals are associated with negative outcomes (e.g., lower self-efficacy, test anxiety, shallow cognitive processing, poor performance, low levels of intrinsic motivation, high negative achievement emotions, for reviews see Elliot, 1999; Senko, Durik, & Harackiewicz, 2008; Huang, 2011).

In what might be considered a first test of the role ST plays in inducing performance-avoidance goals, Brown and Joseph (1999) told student participants that a diagnostic math test would reveal whether they were “exceptionally weak” (avoidance manipulation) or “exceptionally strong” (approach manipulation) in math. Consistent with the stereotype that women are bad at math, women performed worse on the task when the avoidance (vs. approach) orientation was induced. Following this work, Smith (2004) suggested that the various processes and outcomes of ST might be a function of achievement goal adoption (see also Ryan & Ryan, 2005), and subsequent research has supported this hypothesis. Smith (2006) found that when women were reminded of the stereotype that they are poor at math (ST condition), they endorsed more performance-avoidance goals toward an upcoming math exam compared to women who were told that men and women perform the same on the math task (no-stereotype threat condition) (see also Brodish & Devine, 2009). ST has been shown to trigger performance-avoidance goals both when goals were measured with open-ended and Likert scale items (Smith, Sansone, & White, 2007).

An avoidance orientation toward a task can take many forms. For example, a “prevention” focus is conceptually similar to a performance-avoidance goal (Chalabaev, Major, Cury, & Sarrazin, 2012), but grounded in social-development and regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1998). Prevention-focused students strive for the absence of losses and try to avoid losses (Molden, Lee, & Higgins, 2008). A prevention focus induces a wide range of security-related processing (Evans & Petty, 2003; Freitas, Azizian, Travers,s & Berry, 2005) including an aversion to making mistakes (Crowe & Higgins, 1997), less creativity (e.g., Friedman & Forster, 2001; Crow & Higgins, 1997), increased preference for stability (Liberman, Idson, Camacho, & Higgins, 1999), and an increased desire to engage in behaviors that maintain relationships (e.g., Ayduk, May, Downey, & Higgins, 2003; Molden & Finkel, 2006). Because most tasks used in ST research evoke penalties for doing poorly on the task (e.g., incorrect items on the GRE) and penalties are eliminated for success on the task, this theory predicts that a prevention focus should arise as a consequence of ST (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Shah & Higgins, 1997).

Seven experiments have examined the association between ST and prevention focus at both a chronic and situational level of analysis. Under ST students hone in on avoidance-related (versus approach-related) cues and information (Seibt & Forster, 2004), and such a focus can result in decreased performance. For instance, men who believed that gender differences had emerged on a verbal task (negative expectancy/ST) and were in a prevention focused mind set (instructed to “avoid errors”) performed worse on a test of verbal ability than men in a promotion focused mind set (instructed to “solve as many items as possible;” Keller, 2007). Replicating these results at a situational level of analysis, women in a prevention focus who were told that men performed better on the driving exam than women (negative expectancy/ST) actually did perform worse on a subsequent driving test than women who were told that women tend to outperform men (Keller & Bless, 2008).

A key point in the regulatory focus literature is how the task at hand matches the current focus of the individual (either promotion or prevention). If students are told to work on a task slowly and to avoid making mistakes on a word puzzle, for example, they perform better on the word puzzle if they are under a prevention focus (versus a promotion focus) because the strategies that accompany a prevention focus are consistent with the task instructions (e.g., Markman, Baldwin, & Maddox, 2005). Given that ST induces a prevention focus (Smith et al., 2007) the regulatory fit prediction is somewhat counterintuitive: performance is better under ST when the task is framed in terms of avoiding loss (ie., participations are told they will lose more points for incorrect as opposed to correct responses) as opposed to approaching gains (participates are told they will gain more points for correct as opposed to incorrect responses) because the loss framing of the task matches the prevention focus evoked by ST (Grimm, Markman, Maddox, & Baldwin, 2009). Because of this “matching” hypothesis, there may be a short term advantage to adopting performance-avoidance goals under ST, to the extent that the task a stigmatized student will work on invokes penalties for both correct and incorrect responses (thus matching the regulatory-focus of the student). Indeed, adopting a prevention-focus under ST and engaging in a task that matches the individual’s regulatory focus is associated with increased flexibility in trying different strategies to perform better on the task (Grimm et al., 2009). Furthermore, two studies have shown that adopting a prevention focus under ST can ready a students’ cognitive resources for “flight or fighting” the stereotype (Stahl, Van Laar, & Ellemers, 2012). For example, when the “social science-major” group stereotype was activated (i.e., social science students perform worse on the task than “exact” science students), social science students who were induced to adopt a prevention focus gained cognitive control (Stahl et al., 2012), which is consistent with the hypothesis that ST increases cognitive control. However, compared to women in the control condition (when the task was framed as about working memory capacity), women under ST (when task was framed as understanding differences in math ability) performed worse on a stereotyped task given five minutes after the ST induction, suggesting that the initial increase in cognitive control results in cognitive fatigue over time because of the cognitively demanding nature of ST (Stahl, et al., 2012; see also Hutchison, Smith, & Ferris, 2012). Thus, when individuals are prevention focused, ST initially causes increased cognitive resources to be pooled in the short term, potentially providing some short term performance benefits. However, in the long term, ST causes performance decrements due cognitive fatigue.

The literature supports the conclusion that ST results in avoidance of undesirable outcomes, whether it be because individuals adopt performance-avoidance goals or a prevention focused orientation. The adoption of avoidance related goals and motivations not only have implications for performance within the stereotyped domain (e.g., Brodish & Devine, 2009; Gaillard, Desmette, & Keller, 2011; Keller, 2007; Keller & Bless, 2008), but might also impact interest in the stereotyped domain (Smith et al., 2007), the availability of cognitive resources (Stahl et al., 2012), and result in threat-related physiological responses (Chalabaev, Major, Cury, & Sarrazin, 2009). In our model (presented below) we argue that these achievement orientations with which students approach an activity influence motivational experiences (belonging and interest) during activity engagement.

Review of research on stereotype threat and sense of belonging

Although motivation for educational tasks is often identified as deriving purely from goals or individual achievement motives, students’ sense of belonging in the activity context (e.g., in the classroom, the school, or the study group) is a critical motivational experience. Maintaining a sense of belonging, or social connection, is a fundamental human motivation, and people seek out environments that fulfill that motivation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Murray, 1938). Student belonging, and related variables such as classroom social environment, students’ relationships with peers and teachers, and social goals are important for academic success (Anderman & Kaplan, 2008; Juvonen,1996), particularly for underrepresented minority students who face chronic stereotypes (Hurtado & Carter, 1997). Student belonging is a stable predictor of achievement, achievement motivation and behavior, interest and enjoyment, as well as persistence and engagement (Freeman, Anderman, & Jensen, 2007; Goodenow, 1993; Goodenow & Grady, 1993; Hurtado & Carter, 1997; Juvonen, 2007; Sage & Kinderman, 1999; Patrick, Ryan, & Kaplan, 2007; Ryan & Shim, 2006; Urdan & Maehr, 1995; Wentzel, 1994; 1997). Belonging predicts task motivation and persistence even when derived from a minimal social connection (Walton, Cohen, Cwir, & Spencer, 2012).

Belonging has been identified as a critical mediating process in the effects of ST on the underachievement of stigmatized students (Cohen & Garcia, 2008; Mendoza-Denton, Downey, Purdie, Davis, & Pietrzak, 2002; Walton & Carr, 2012). Walton and Cohen (2007) suggest that, “in academic and professional settings, members of socially stigmatized groups are more uncertain of the quality of their social bonds and thus more sensitive to issues of social belonging” (p. 82). Walton and Cohen call this state belonging uncertainty, suggesting that belonging, for most individuals, is a hypothesis, not a belief, and that the lack of certainty about one’s belonging, rather than clearly knowing that one does not fit it, creates tension against this fundamental social need to belong (Walton & Cohen, 2007). Other researchers measure this experience as low on continuous measures of belonging, rather than defining low belonging as uncertainty. From both theoretical conceptualizations, research has demonstrated ST effects on students’ sense of belonging through both experimental and classroom studies, and across studies this work illustrates that many different types of contextual ST cues (e.g. being a numerical minority) can negatively affect belonging (Smith, Lewis, Hawthorne, & Hodges, 2013).

Three studies have examined the relationship between ST and belonging by tapping into stigmatized students’ perceptions of other people in stereotyped domains. African American students who received an experimental manipulation of belonging uncertainty (they believed they would have few friends in computer science) reported lower belonging and lower likelihood of potential success in computer science than those who received positive belonging cues or no cues (Walton & Cohen, 2007). Self-report survey data similarly demonstrate that across social groups and academic fields individuals’ lower interest in potentially pursuing stereotype-threatening fields can be explained by decreased feelings of belonging. For example, women’s lower ratings of whether they considered majoring in STEM, compared to men, was accounted for by their lack of perceived similarity to others in the field (Cheryan & Plaut, 2010). Additionally, students’ perceptions of the numeric make-up of individuals in a field also influence their sense of belonging to the field (Murphy, Steele, & Gross, 2007; Smith et al., 2013). For example, when math, science, and engineering (MSE) majors watched a conference video showing higher number of males than females (thus subtly reinforcing the stereotype that science is for men), women, but not men, reported lower belonging in MSE fields (Murphy et al., 2007).

Several studies have also shown ST effects on belonging when stereotypes were communicated through more subtle means. When job descriptions used more masculine themed words (e.g., emphasizing competitiveness and dominance) women reported lower levels of anticipated belongingness and decrease job appeal, compared to descriptions that used more neutral words (Gaucher, Friesen, & Kay, 2011). In addition, results indicated that the effect of gendered wording on job appeal was mediated by sense of anticipated belonging. Similarly, greater use of masculine (vs. feminine) pronouns in a job description predicted lower belonging for female, but not male, potential applicants (Stout & Dasgupta, 2011). The physical classroom environment can also communicate stereotypes and affect stigmatized students’ sense of belonging. Women brought to a computer science classroom decorated primarily stereotypically masculine objects (e.g., Rubik’s cube, Star Trek poster) reported lower sense belonging in computer science than those brought to a classroom with objects not considered stereotypical of computer science (e.g., nature posters, phone books), whereas these classrooms had no effect on men (Cheryan, Plaut, Davies, & Steele, 2009). These findings also extend to a virtual classroom environment. Even when the learning material, gender of the professor, and ratio of classmates were identical, women reported lower belonging when participating in a virtual class environment (using Second Life classroom simulation) designed to be representative of masculine computer science stereotypes than in a class that did not convey these stereotypes (Cheryan, Meltzoff, & Kim, 2011). Thus, even subtle manipulations of ST are enough to cause decreased feelings of belonging.

In addition to studies demonstrating negative effects of ST on belonging, a successful intervention study designed to combat ST by increasing student belonging illustrates the central role of belonging in ST processes. This intervention is grounded in the theory that students are motivated to seek out information regarding their sense of belonging, which prompts stigmatized students, in particular, to notice threatening cues that may have gone unnoticed otherwise (Cohen & Garcia, 2008). The intervention was designed to provide stigmatized students with an alternative hypothesis for adversity that is not based on social groups (i.e., gender, ethnicity). By framing social adversity (which includes feeling belonging uncertainty) as universal, typical, and short-lived, stigmatized students were provided with an alternative explanation for negative feelings that was not based on their group membership (Walton & Cohen, 2011). Researchers presented a narrative about how belonging uncertainty is common for incoming college students to a randomly chosen group of African American students. Only students in this intervention condition, but not control conditions, reported elevated feelings of belonging with the university over time. This intervention also helped these stigmatized students sustain their sense of belonging on adverse days, compared to students who did not receive the intervention. The positive benefits associated with feeling a sense of belonging were clear: African American students who received the belonging intervention also reported greater engagement and persistence with achievement behavior, such as studying longer, sending more emails to professors, as well as an overall increase in GPA, compared to those in control condition and White students. The effects were seen even three years after the intervention, where African American students who received the intervention continued to show positive achievement motivation and behavior, and outperformed the expectations of the typical African American student at the school (Walton & Cohen, 2011).

Taken together, considerable research provides support for the influence of ST on students’ sense of belonging, and an intervention designed to address this core social motivation have alleviated ST effects on student achievement. Although sense of belonging has long been recognized as an important psychological variable for student success, the recent research on ST effects on belonging demonstrates that it is even more important to understanding the choices and achievement of stigmatized and underrepresented students (Cohen & Garcia, 2008).

Review of research on stereotype threat and situational interest

Whereas sense of belonging represents students’ motivational experience with the (real or implied) social context of the activity, situational interest represents students’ phenomenological experience of engagement (or involvement) with the learning activity or material. Catching a student’s interest is an important step for promoting potential development of longer term individual interest and overall academic domain identification (Hidi, 1990; Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Renninger, Sansone & Smith, 2004; Sansone, Thoman, & Smith, 2010). Situational interest has often been conflated with enjoyment. Though both are positive emotions (Silvia, 2008), enjoyment encourages individuals to choose what is familiar and provides rewards for goal attainment whereas experiencing interest promotes engagement with novel and complicated concepts, focuses attention, and replenishes cognitive resources, all of which facilitates the development of understanding and expertise (Silvia, 2008; Thoman, Smith, & Silvia, 2011). Situational interest (also described as the experience of interest (Sansone & Thoman, 2005)) is a phenomenological experience that occurs when characteristics of the situation catch the student’s attention whereby emersion, engagement, and involvement are high (e.g., Hidi, 1990; Hidi & Baird, 1988; Krapp, 1989). This experience is akin to feeling “intrinsically motivated” (Sansone & Thoman, 2005) and at an optimal level may be experienced as “flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975). Other educational researchers describe this experience as “engagement”, but engagement also includes an explicit behavioral dimension and is typically defined at the broader level of engagement in school (Wang & Holcombe, 2010), whereas interest more specifically describes the motivational experience during an activity relevant to that interest. Situational interest in learning activities and classes is a strong predictor of persistence and identification with educational and career pursuits (Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, & Elliot, 2002; Harackiewicz et al., 2008; Hidi & Renninger, 2006). Thus, by understanding how ST is associated with situational interest, researchers can begin to examine one of the motivational precursors to the development of sustained individual interest (or lack thereof) within a stereotyped domain (Thoman & Sansone, 2012).

Two studies have examined how ST influences students’ experience of situational interest. Both focused on whether stereotype threat reduces women’s experience of interest when working on a science task. In the first study, prior to engaging in a computer science programming task women were either told that men are better than women in mathematical domains (ST condition) or that no gender differences emerged in mathematical domains (no ST condition, Smith, et al., 2007). Women in the ST condition were less absorbed in and rated the computer science task as less interesting than those in the no threat condition. Reports of situational interest were particularly low when the ST trigger was coupled with adoption of a performance-avoidance achievement goal (see Smith et al., 2007 as reviewed in the section above).

The second study manipulated whether or not science task performance feedback was perceived as being due to gender bias (Thoman & Sansone, 2012). Though not a typical manipulation of ST, it is reasonable to assume that receiving more negative feedback than a man on a science task because of gender bias would trigger ST for women. Both a woman participant and a man confederate completed a science task, which the experimenter was to grade. Participants were told that the person who performed best on the task would lead the second science task. When the experimenter left the room to ostensibly consult her supervisor about the experiment, participants either heard the supervisor arbitrarily choosing the male participant to be the leader, the supervisor choosing the male participant to be the leader because men are better at science (pro-male bias/ST), or no information pertaining to who would be the leader (control). Women in the pro-male bias/ST condition rated the science task as less interesting than women in the no feedback and the feedback no reason conditions, and ratings of task interest predicted their likelihood of requesting information on related careers (Thoman & Sansone, 2012).

Although only two studies have directly examined ST effects on situational interest, these studies provide converging evidence that ST decreases an individual’s experience of situational interest within the stereotyped domain. Although other studies within the research literature describe effects of ST on interest, these studies have typically measured interest in terms of participants’ likelihood of pursuing a domain in the future (e.g., Cheryan et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2007). To maintain conceptual distinctions between situational interest and career intentions that have been established by educational interest researchers (cf. Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Renninger & Hidi, 2011), we review those studies below in the section on career motivation and intentions. Because future domain pursuit can arise from a number of motivations (e.g., belonging, interest, domain identification), it is unlikely that these measures purely reflect participants’ situational interest. Thus, we only reviewed those studies where situational interest in a task was clearly measured. Because individual long-term interest and domain identification develop, in part, out of situational interest, we will next discuss the influence of situational interest on domain identification and individual interest.

Review of research on stereotype threat and domain identification

A well-developed sense of identification with an educational/career domain is among the strongest psychological predictors of future choices and continued engagement with classes and activities related to that domain (for review see Osborne & Jones, 2011). A strong sense of domain identity is experienced when a given course of study (e.g., science) is tied to the student’s sense of self and becomes more centrally integrated into the self-concept (Osborne & Jones, 2011); when this occurs the field provides meaning and definition to the student (Smith & White, 2002). Domain identification then is commitment to a category that is tied up with self-esteem. Disidentification is not the absence of such a commitment, but rather the active distancing of one’s self-esteem from a category or domain (Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001; Kreiner & Ashforth, 2004; Matschke & Sassenberg, 2010; Verkuyten & Tildiz, 2007). Because both identification and disidentification involve a relationship between one’s self-esteem and the ST domain, work on identification can certainly inform whether and how disidentification might be triggered and/or circumvented as domain disidentification is associated with a host of negative outcomes (e.g., delinquency, Hindelang, 1973). In this section we will focus primarily on disidentification because it has received considerable attention from a few ST researchers. Over time, repeated exposure to ST is posited to lead to disidentification as a means to protect the self from feelings of threat (Crocker & Major, 1989; Steele, 1992; 1997).

Two large-sample educational studies provide evidence for the relationship between ST and disidentification. The first is a national longitudinal study of students who participated in funded programs designed to increase representation of minority students in science (Woodcock, Hernandez, Estrada, & Schultz, 2012). Results suggested that reported levels of ST predicted subsequent disidentification from science for Hispanic/Latino students, which in turn predicted later decreased desire to pursue a scientific career (Woodcock et al., 2012). Providing indirect evidence for this relationship, results from a survey of high school students suggested that African American students who strongly identified with academics were more likely to withdraw from high school in the next two years, but no association between academic identification and withdrawal emerged for Caucasian students (Osborne & Walker, 2006). Thus, this work suggests that the most highly identified students, when exposed to negative stereotypes about their group, suffer the strongest negative effects and subsequently disidentify by withdrawing from school Together, these data suggest that greater ST predicts students’ subsequent disidentification from stereotyped domains.

Several smaller correlational and experimental studies have also examined the link between ST and disidentification, providing further evidence that under chronic or situational ST conditions students disconnect their identities and evaluations of self-worth from (potentially unfair) evaluations of performance in the ST domain. Two studies demonstrated this effect by comparing correlational data for Caucasian and African American students, who face chronic negative academic stereotypes about their group. Both studies found that for Caucasian students, self-esteem consistently positively correlated to academic outcomes throughout high school. Thus, self-esteem for these students increased following success and decreased following failures. For African American students, however, the positive correlations between self-esteem and academic outcomes (i.e., grades/achievement) became weaker over time (Osborn, 1995, 1997). These studies demonstrate that the process of disconnecting self-esteem from academic outcomes for African American students occurred gradually over time.

Experimental studies have replicated these effects using laboratory manipulations of ST and measuring temporary disengagement of self-esteem from achievement in the ST domain. Across two studies, Major and colleagues hypothesized that in the face of negative academic stereotypes about their group, students’ self-esteem would be insensitive to performance feedback (Major & Schmader, 1998; Major et al., 1998). Indeed, in both studies they found although European American students’ self-esteem increased (or decreased) following positive (or negative) performance feedback, when stereotypes were salient African American students’ self-esteem was not influenced by performance feedback (positively or negatively). Thus, ST can not only lead to disidentification through students’ efforts to cope with the threat by decoupling evaluations of self-worth from achievement outcomes over time, but students’ may also temporarily disengage their self-esteem from the domain based on performance feedback (Major et al., 1998). In a temporary situation, this coping mechanism may help students deal with anxiety related to ST and even aid performance on a single task (Nussbaum & Steele, 2007), but over time this process might result in disidentification with the stereotyped domain.

In short, feelings of ST lead to decreased identification with the ST domain. Although variables representing the connection between students’ sense of self/identity and academics are important in their own right, scholars and educators are typically interested in these variables to the extent that they predict actual career aspirations and pursuits (Nye, Su, Rounds, & Drasgow, 2012). Research on domain identification has demonstrated strong connections to these educational and career outcomes (Osborne & Jones, 2011); but other research has more directly examined the relationship between ST and career motivations and intentions.

Review of research on stereotype threat and career motivations and intentions

Understanding stigmatized student’s specific career motivations and intentions are particularly important as scholars aim to assist in the broadening of participation of underrepresented minorities (URMs) in various fields. As such, understanding the role of ST and career motivations is particularly relevant and important as an area of inquiry. Perhaps one reason URMs opt out of certain fields is because of repeated exposure to ST situations. Certainly performance and achievement are necessary for considering one’s probable career options; however, these variables are not sufficient for accounting for why stigmatized students choose certain career paths (e.g., Hofer, 2010; Lubinski & Benbow, 2006; Osborne & Jones, 2011). ST has been shown to influence student’s motivations and career intentions across a number of studies, separately from effects on performance.

Most of the current literature examining the role of ST on career intentions finds that ST is linked with a decreased desire to pursue stereotyped domains. Feelings of ST have been associated with women’s greater likelihood of changing majors away from male-dominated fields (i.e., math, science, or engineering) and towards female-dominated fields (i.e., arts, education, humanities, or social science; Steele, James, & Barnett, 2002; also see Davies et al., 2002). An experimental study demonstrated that when women were exposed to gender-stereotypic commercials they expressed less motivation to be a leader (a male-stereotypic domain) and greater motivation to be a problem solver (a gender-neutral domain) on a subsequent task (Davies, Spencer, & Steele, 2005). Even reading a paragraph describing an entrepreneur as having masculine characteristics (aggressive, risk taking, autonomous) as opposed to gender neutral characteristics (creative, well-informed, steady, and generous) caused proactive women (i.e., highly likely to strive to change their environments) to be less likely to believe that they could be self-employed or have a small business (Gupta & Bhawe, 2007). In fact, when job advertisements contain fewer feminine than masculine words, women report the advertised jobs are less appealing (Gaucher, Friesen, & Kay, 2011). Feelings of gender role incongruence have also been shown to elicit ST for men (Koenig & Eagly, 2005); activating homosexual stereotypes caused heterosexual men to express less willingness to engage in tasks related to feminine domains in the future (i.e., elementary school teacher and nurse) in comparison to heterosexual men in the control condition (Allen & Smith, 2010). Thus, ST causes individuals to express a decreased desire to pursue stereotyped domains.

In addition, career motivations and intentions, as well as behaviors and choices that indicate these motivations, can be influenced by subtle cues in the educational environment that trigger ST. For example, when women watched a video of a math, science, and engineering conference that contained an unequal ratio of men to women, they were less likely to want to participate in the conference than women who watched a video containing an equal ratio of men to women (Murphy et al., 2007). Likewise, when female students looked over an eco-psychology program brochure with all male professors they reported lower willingness to apply to a similar master’s program than women who looked over the same brochure with an equal number of male and female professors (Smith et al., 2013). Even mere interactions with a stereotypical (vs. non-stereotypical) role model in computer science decreased women’s beliefs about their future in computer science (Cheryan, Siy, Vichayapai, Drury, & Kim, 2011). In another study, when working in a room that was outfitted with objects consistent (vs. inconsistent) with the “nerdy male-centric” stereotype of computer science, women reported less interest in majoring in computer science, even when only women were in the environment (Cheryan et al., 2009). This pattern was also replicated in a virtual (online) classroom with women being more interested in enrolling in an online computer science class when the virtual environment emphasized non-stereotypical (with pictures of nature posters, water bottles) than stereotypical (ST; science fiction items, videogames) objects (Cheryan et al., 2011). Taken together, these studies support the conclusion that ST decreases intentions to pursue stereotype-relevant domains in the future, even when ST is elicited by subtle cues within the educational environment.

Although stereotype endorsement is not a requisite for ST to occur in a given situation, internalization of stereotypes can be one outcome of chronic stereotype salience, and endorsement of domain-related stereotypes decreases one’s desire to pursue the stereotyped domain. For example, women college students who endorsed statements pertaining to inequality between the sexes (i.e., women are worse than men in math) expressed less interest in continuing to study as a math major (Schmader, Johns, & Barquisau, 2004). Furthermore, endorsement of the female gender role (either implicitly or explicitly) coupled with implicit beliefs associating men with being better at math and or science lead to decreased desire to pursue STEM related careers in the future (Keifer & Sekaquaptewa, 2007; Lane, Goh, & Driver, 2012).

Further, ST not only influences career intentions, but when ST occurs, individuals who have chosen to pursue a stereotyped career feel less committed to their career. Holleran, Whitehead, Schmader, and Mehl (2011) investigated workplace conversations of STEM faculty to examine the relationship between job disengagement and the content of conversations with colleagues (male-stereotypic: talking about research; female-stereotypic: talking about social topics). When women faculty conversed about research with male colleagues they reported more disengagement from their job, whereas when women conversed about social topics with male colleagues they reported less disengagement from their job. These patterns did not hold for male colleagues’ interactions with female colleagues. Thus, ST not only influences an individual’s intention to pursue a career, but also their dedication to their career after a career has been chosen.

Taken together, the literature consistently demonstrates that ST influences stigmatized student’s motivations to (not) pursue stereotyped domains and related career intentions, as well as well as commitment to one’s current career. Several of these studies demonstrating this relationship have also examined what variables mediate this effect of ST, and the mediating variables identified are typically ones reviewed in sections above, though different studies focus on different mediating motivational processes. Given this state of the literature, we have opted to focus this review (and the scope of our model) on how ST can influence students’ educational and career path choices apart from their achievement and performance. In the Motivational Experience Model of ST, presented below, we fully explore these mediating processes and how ST can influence students’ efforts to regulate their motivations that promote sustained academic and career engagement.

Putting it all together: The Motivational Experiences Model of Stereotype Threat

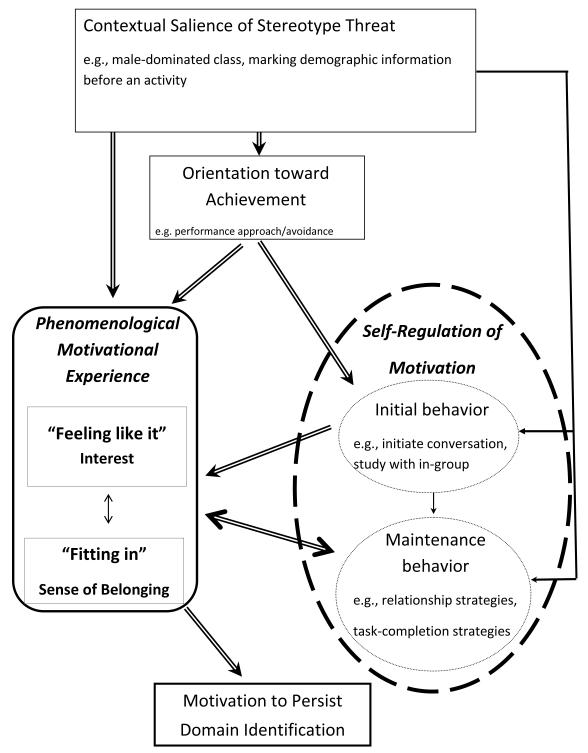

Review of the above research literature provides compelling evidence that ST affects a number of motivational variables central to educational and achievement pursuits. However, there is currently no model that integrates how these ST effects on different motivational variables fit together; we do so by introducing the Motivation Experiences Model of Stereotype Threat. The model’s foundation is the conceptualization of students as active and their motives as interrelated dynamic processes embedded within a self-regulatory framework that unfolds over time during stereotyped activity engagement. This conceptualization places ST effects within a model that is consistent with contemporary educational psychology views of motivation and self-regulated learning, proving a link that is currently missing between these literatures. Viewing motivation as a process within the context of activity engagement allows for specification of relationships between goals-defined (e.g., achievement goals and orientations) and phenomenological (e.g., experience of interest and belonging) motivations, as well as consideration for how individuals’ actions during activity engagement influence motivation to persist (Sansone & Smith, 2000; Sansone & Thoman, 2005), which ultimately include their development of domain identification in addition to educational/career intentions and behaviors. A diagram of the model is provided in Figure 1. The diagram illustrates the interrelations among motivational experiences and self-regulatory processes during the course of stereotyped activity engagement. All specified causal links between variables have been established in previous research (either reviewed above or cited below), with the exception of the direct link from ST to self-regulation behaviors, which represents a new prediction that derives only from situating ST effects within a self-regulation model. We focus particular attention to this new theoretical prediction below, but first we describe each step of the model by starting at the top of the diagram, where ST is triggered by contextual cues, and moving down.

Figure 1.

Motivational Experience Model of Stereotype Threat. Double lines indicate direct motivational effects and single lines indicate indirect effects of stereotype threat via perceived situational constrains on options for regulating motivation.

When a student begins a stereotyped activity, the salience of ST can be triggered by a variety of educational contextual cues. ST can be triggered by features of the task itself, such as having students report demographic information before a test or activity (Steele & Aronson, 1995) or by describing the task in a stereotype consistent manner (Brown & Day, 2006; Huguet & Regner, 2007). In the classroom, stereotype threat can be triggered by being or expecting to be a numerical minority among a group of students (Stout, Dasgupta, Hunsinger, & McManus,, 2011; Huguet & Regner, 200; Inzlicht & BenZeev, 2000; Murphy et al., 2007; Sekaquaptewa, Waldman, & Thompson, 2007), by the gender or ethnicity of the instructor (Stout et al., 2011; Marx & Goff, 2005), as well as by stereotype-consistent physical contextual features of the classroom or learning environment (Cheryan et al., 2009) and even online learning environments (Cheryan et al., 2011). Stereotype threat can also be triggered by the actions of others, including explicit statements about relevant stereotypes (Aronson, Lustina, Good, & Keough., 1999; Smith & White, 2002; Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999), relatively more subtle interpersonal interactions with other students or teachers (Logel et al., 2009; Marx & Goff, 2005), and even interacting with someone who is perceived as holding stereotype-consistent attitudes (Adams, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, & Steele, 2006). Activities that are chronically perceived as negatively stereotyped can also trigger stereotype threat by implicitly activating the psychological link between this activity and the stereotype for the student (Dasgupta, 2011), even in the absence of additional cues (Smith & White, 2002). We suggest that what matters for students’ motivational experience is not what triggers the threat (but see Stone & McWhinnie, 2008), but the implications of ST once triggered psychologically.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the model suggests that, once triggered, ST can influence both how a student approaches and experiences stereotyped task engagement. Although contextual cues can influence motivation through processes other than by triggering ST, given the present focus we limit the model and discussion of contextual effects to ST only (for a broader discussion of contextual effects on the self-regulation of motivation, see Sansone & Smith, 2000; Sansone et al., 2010). Specifically, ST first affects the student’s orientation toward achievement (with which she or he approaches the task), phenomenological experience of motivation during the task, as well as initial task behaviors and task behaviors used to regulate one’s motivational experience during task engagement. Orientation toward achievement represents the academic achievement goals and orientations (e.g., promotion vs. prevention focus) that are set prior to task engagement. Both the type of achievement goal adopted and the cognitive expectancy and value components of goals play a critical role in student motivation and achievement (Ames, 1992; Elliot, 1999; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Maehr & Midgley, 1991; Pajares, 1996; Schunk & Miller, 2002). Achievement orientation is associated with most student outcomes, including performance, efficacy, learning, effort, and career motivation (Anderman, 1999; Dweck, 1986; Elliot, 1999; Meece, Anderman, & Anderman, 2006; Shim, Ryan, & Anderson, 2008). Smith’s (2004) Stereotype Task Engagement Process Model explicates the critical mediating role of achievement orientations, particularly avoidance motivational orientations, in ST effects on achievement (Smith, 2006; Smith et al., 2007). Once set, this orientation toward achievement directs initial task-related behaviors (note that in the Figure constructs inside the dashed oval represent task-related behaviors, to distinguish task-related behaviors from the motivations they are associated with). These initial task behaviors are shaped by features and constraints of the task itself (e.g., in some learning activities a teacher may allow students to work flexibility alone or with others whereas other activities are more tightly constrained by detailed inflexible task instructions) and by the student’s orientation toward achievement. These behaviors include both intra- and interpersonal interactions with the activity itself and other people who comprise the activity’s social context. The experience of ST can further shape these initial behaviors, particularly acting as a constraint to social task-related behaviors.

Once students begin working on the activity, a phenomenological motivational experience corresponding to these initial behaviors develops. The model distinguishes between two components of the student’s phenomenological motivational experience: interest (or intrinsic motivation) and sense of belonging (or social/affiliation motivation). The first component represents students’ feelings toward and engagement in the task. The phenomenological experience of interest is a dynamic state, involving both cognitive and affective components, that arises through an ongoing transaction among goals, context, and actions (Sansone & Smith, 2000). The experience of interest is similar to the construct of situational interest (Hidi, 1990), and at its extreme this motivational process may be experienced as “flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975). The experience of interest focuses students’ attention, promotes, and harnesses resources for sustained engagement, aids knowledge and skill development, and helps students overcome feelings of frustration (Harackiewicz et al., 2008; Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Silvia, 2008; Thoman et al., 2011). Maintaining interest is critical for long-term persistence (Sansone & Thoman, 2005; Sansone et al., 2010).

The second component of students’ phenomenological motivational experience represents feelings about their perceived social connectedness to others in this activity or domain. This experience captures whether students feel like they ‘fit in’ or not (with real or imagined people) within this activity context. People are fundamentally motivated to experience a sense of belonging, or a sense of social connectedness, and seek out environments that fulfill their affiliation and relatedness needs (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Murray, 1938). Sense of belonging is a critical motivational variable for students; greater belonging predicts achievement, achievement motivation and behavior, interest and initial appeal, as well as persistence and engagement (see review above). These two phenomenological motivational components, interest and belonging, are expected to be positively related in most achievement contexts (Anderman & Kaplan, 2008), but as reviewed above, the experience of stereotype threat in that context may disrupt one or both components. The bidirectional arrow between these motivational experiences in the diagram represents the potential reciprocal relationship between the experience of interest and belonging during activity engagement. Thus, if ST disrupts either motivational experience, it may indirectly affect the other while the student’s experience unfolds over time during engagement.

As time passes during task engagement, if feelings of interest or belonging are low, the model suggests that the student will either quit the task or engage in task-related maintenance behaviors designed to strategically regulate one or more of these motivational processes. This self-regulation of motivation component of the model derives from the Self-Regulation of Motivation (SRM) model (Sansone & Harackiewicz, 1996; Sansone & Smith, 2000; Sansone & Thoman, 2005), but differs from previous writing on and research support for the SRM model in the explicit proposal of not only regulating interest but also students’ sense of belonging, specifically during stereotyped task engagement when stereotype threat is “in the air” (Steele, 1992; 1997). The behavioral regulatory options available to students are constrained by features of the task (e.g., whether students are allowed to work in ways that make the activity more interesting or increase feelings of connectedness with classmates), and a constant feedback loop develops between task-related behaviors and the phenomenological motivational experience. If ST directly or indirectly (via the mediated paths illustrated in the Figure) influences a student’s experience of interest or belonging and he or she has a good reason to continue (such as wanting to achieve in this class or activity), the student may attempt to enhance feelings of interest or belonging, or both. The salience of ST may also influence students’ motivation regulation behaviors in two ways. First, regulatory behaviors that may normally be available to students for regulating their motivational experience (e.g., working with other people, Isaac, Sansone, & Smith, 1999) may be constrained (psychologically) under stereotype threat situations (Holleran et al., 2011). That is, feeling threatened may limit a stigmatized student’s perceived options, particularly social options, that may otherwise promote interest and/or belonging for activities in the absence of threat. Second, experiencing ST may promote behaviors that can be effective for regulating the student’s immediate motivational experience but which have negative implications for academic achievement and/or the development of domain identification. We further explicate and review research evidence for this self-regulation of motivation component of the model below.

Whether regulated or not, the model suggests that this phenomenological motivational experience shapes students’ motivation to persist or quit the activity, to re-engage similar activities, and their ability to develop strong identification with the domain. This emphasis on the motivational experience during activity engagement as the critical mediating process for how ST affects motivation to persist and domain identification provides a clear distinction between our model and those that represent motivation at the cognitive (rather than experiential) level. For example, models such as Social Cognitive Career Theory (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994) and Eccles’s expectancy value theory (Eccles, 1994; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002) specify social cognitive representations as the critical variables that explain how stereotypes shape motivation to persist. Our model includes these social cognitive variables within the ‘orientation toward achievement’ component, and links these variables with the phenomenological motivations of interest and belonging within the self-regulatory framework (cf. Sansone & Thoman, 2005; Smith, 2004). Our model’s emphasis on the self-regulation of the motivational experiences of interest and belonging is also unique to motivational models of ST effects. This critical component of the model suggests that in addition to the directly disruptive effects of ST on motivational expectations and motivation experienced during stereotyped engagement, the activation of ST for a stigmatized student may also constrain that student’s efforts to regulate motivation. For example, relative to when working on a non-stereotyped task, the experience of ST may limit the student’s perceived options for task-related behaviors (particularly social behaviors such as working in teams) that would normally increase interest and/or belonging. Just as concern about confirming the negative stereotype about one’s group can disrupt task performance, we propose that this concern makes stigmatized students acutely aware that task-related behaviors and task-related interactions with others could also potentially confirm the stereotype. Students may subsequently avoid any behaviors that could potentially confirm the stereotype, even if these same behaviors would increase their motivational experience. Thus, this regulatory framework includes conceptualization of reciprocal processes that unfold over time and are recognized as critical to understanding the effects of ST and interventions strategies designed to ameliorate effects of ST (Cohen & Garcia, 2012; Yeager & Walton, 2011).

How stereotype threat disrupts students’ self-regulation of motivation

Self-regulated learning is a central construct in educational psychology (Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006; Schunk & Zimmerman, 1994; Zimmerman, 2000). Educational researchers widely recognize that regulation strategies take a variety of forms and that the regulation of motivation represents one component of self-regulated learning (Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006; Wolters, 2003). Further, researchers in this area have recognized the general principal that one’s social environment and interpersonal behaviors can create social demands that in turn impose restrictions on various regulatory efforts (Boekaerts 1993; 1998; Kuhl, 2000), and that students from minority backgrounds may face specific barriers to regulating motivation for school and future educational goals (Phalet, Andriessen, & Lens, 2004). The focus of our model is much more narrow than self-regulated learning theories (see Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006), but we view our conceptualization of how ST influences stigmatized individuals’ regulation of motivation as consistent with the broader principles of this work, which has not previously focused on the specific social context of ST. Indeed, we consider the effects of ST on student regulation of motivation as a specific person by situation case that concretely illustrates how and why students’ social environments can restrict specific types of strategic regulatory efforts.

To detail how ST influences the regulation of motivation, we describe student strategies that have been identified in the literature for regulating the motivational experiences of interest and belonging, as well as regulating motivation associated with achievement orientations within typical or everyday learning contexts. Within each section, we review relevant research and describe predictions for how the experience of ST could disrupt potentially useful regulatory actions or promote potentially unhealthy (from an educational achievement perspective) regulatory strategies. The available options for regulating motivation are necessarily dependent upon the kind of learning activity the student is engaged in and the context in which it occurs. For example, different options are available for a student who is studying outside of class than for a student working on a highly structured in-class exercise. Restrictions on available options can be imposed also by teachers, task demands, and by other students. However, in many situations students have some (at least minimal) level of flexibility with which they can engage a learning activity, and students generally have both an implicit knowledge that motivation can be regulated as well as an understanding of how to do so within the environment’s affordances (Sansone & Morgan, 1992; Wolters, 1998). We suggest that concern about confirming negative stereotypes about one’s group can further psychologically influence whether and how students experiencing ST regulate their motivation. We do not attempt to address motivation regulation strategies for all learning contexts or even all motivation regulation strategies identified in past research (for reviews see Wolters, 1998; 2003), but rather we discuss examples of strategies that students have reported or demonstrated which seem most relevant to typical learning activities (e.g., studying, working on class activities or homework, etc.) and likely to be influenced by ST.

Regulating the experience of interest

When a student has a good reason to persist on a learning activity (e.g., wanting to achieve) but the activity is boring, the student may attempt to make the experience of doing the activity more interesting through variety of possible strategies (Sansone, Weir, Harpster, & Morgan, 1992; Wolters, 1998). Depending on available options, students may change either how they do the task or change something about the context of the task. Initially, the extent to which any type of interest-enhancing strategy will be perceived as available depends on the student’s perception of the flexibility of the activity definition and/or activity context (Sansone & Morgan, 1992). That is, if the student feels that the procedures for doing the task and the context within which the task is done are tightly constrained (by teachers or others) the students will perceive interest-enhancing strategies as unavailable. This is the first point in the regulation process where ST may affect stigmatized students’ regulation of interest. Carr and Steele (2009) demonstrated that experiencing ST promotes “inflexible perseverance” or decreases the likelihood of adopting new, more efficient strategies during a task when older ones were ineffective. Carr and Steele examined strategies related to performance rather than interest regulation, but other research demonstrates that ST leads to decreased creative task engagement more generally (Seibt & Forster, 2004). Thus, it seems likely that the inflexible cognitive style promoted by ST would extend to inflexibility with how a student defines a learning task as well as perceptions of how to change it to make it more interesting.

If a student experiencing ST does identify the need to regulate interest and perceives that options are available, this cognitive inflexibility created by ST may also constrain one of the options most commonly reported by students for enhancing interest: turning studying (and other activities) into a game (Wolters, 1998) and add creativity or playfulness into how they do the activity (Sansone & Morgan, 1992). Further, even if a stigmatized student does think of a way to turn an activity into a game or be more creative with it, the heightened social awareness and concern with confirming negative stereotypes about one’s group created by ST may make the student specifically concerned of what others (real or imagined) will think about the student for doing the activity in a playful way. Women in STEM, for example, report feeling that their male classmates struggle to relate to them as colleagues, study partners or friends (Seymour & Hewitt, 1997), so these women report efforts to stand out from others as little as possible and prove that they fit in (Seymour & Hewitt, 1997). If working more creatively on a task could be noticed by peers in a way that makes one stand out, students experiencing ST may be motivated to work on activities in less creative ways so as to not stand out by veering from stereotypical schemas of how a student should do a STEM activity.

Another way that students regulate their experience of interest is by seeking interesting but off-task information on a topic. Sometimes referred to as “seductive details” (Harp & Mayer, 1998), pursuing interesting information that is not the focus of the learning activity can lead to tradeoffs between interest and performance (Sansone, 2009), and this may be particularly true in online learning contexts where students have access to many interesting but only tangentially-related website links. For example, students who regulated interest in an online class by clicking on related links reported greater subsequent interest but also lower subsequent performance (Sansone, Smith, Thoman, & McNamara, 2012). For stigmatized students, this tradeoff may be particularly worrisome, given the heightened concern with confirming negative performance stereotypes. If a stigmatized student perceives that interest-enhancing efforts to explore related information lead to lower performance that confirms the stereotype, she or he may be less likely to pursue those in the future, at a cost to her/his experience of interest and the development of deeper knowledge that is critical to developing a strong individual interest or domain identification (Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Osborne & Jones, 2011).

In addition to changing how they perform the activity, students also commonly change something about their learning context to promote interest (Sansone et al., 1992; Wolters, 1998). Although these strategies include individual actions such as listening to music, ST is most likely to influence social contextual strategies that students employ to regulate interest, such as working with others. The expectation of working with people is an important source of educational and career interest (Morgan, Isaac, & Sansone, 2001), and working together or even alongside another person promotes interest in achievement activities, particularly for individuals higher in interpersonal orientation (Isaac et al., 1999). Students report working with others as a common interest-enhancing strategy (Sansone & Morgan, 1992) and most students can recall academic situations when working with others made an activity more interesting (Thoman, Sansone, & Pasupathi, 2007). Even after the activity, talking with peers who engage responsively in conversation about class-related topics promotes students’ maintenance of interest in the class (Thoman et al., 2007; Thoman, Sansone, Fraughton, & Pasupathi, 2012). For stigmatized students, however, the experience of ST may make them less likely to socially integrate with classmates, participate in campus clubs, approach others about working together, and to talk with others (both peers and instructors) about class-related topics (Fischer, 2007; Hurtado & Carter, 1997; May & Chubin, 2003; Seymour & Hewitt, 1997; Treisman, 1992). Even if students do make efforts to work with others, non-minorities often avoid interactions with stigmatized others (Plant & Devine, 2003; Holleran et al., 2011; Seymour & Hewitt, 1997). Further, those who hold stereotypic views and prejudice often interact awkwardly with stigmatized students, sometimes in a manner that further promotes ST (Logel et al., 2009; Plant & Devine, 2003; Purdie-Vaughns, Steele, Davies, & Ditlmann , 2008). Interactions following learning activities that fail to provide normal positive social feedback may be particularly harmful for the development of student interest (Thoman et al., 2012b).

Regulating feelings of belonging

The interpersonal interest regulation strategies described above have been studied with respect to effects on interest (because of the theory and paradigms driving that research), but from the perspective of our model, which considers belonging as a second experiential motivational process, it seems evident that these interpersonal regulation strategies also have implications for students’ sense of belonging. Positive effects of these strategies on students’ experience of interest may even reflect indirect effects via belonging in some circumstances, given the generally positive relationship between interest and belonging (Anderman & Kaplan, 2008; Thoman, Arizaga, Story, Soncuya, & Smith, 2012). However, this link has not yet been directly empirically investigated, although some studies testing other hypotheses provide preliminary support (e.g., Holleran et al., 2011), so we can only make explicit the assumption that regulation strategies related to working with and talking to others may be affected by ST and can affect both interest and belonging. Beyond studies of these interpersonal interest-enhancing strategies, though, more general research illustrates a number of ways in which individuals actively regulate their sense of belonging following some threat to belonging. This work also highlights the special psychological status of regulating sense of belonging, suggesting that because of our core need for affiliation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995) people seek to repair their sense of belonging following social threats in more specific ways than we regulate other threats to self (e.g., competence threats; Knowles, Lucas, Molden, Gardner, & Dean, 2010). We describe some of these strategies below, discussing how triggered ST may constrain the efforts for stigmatized students.

Failing to fit stereotypical prototypes of academic domains can have negative implications for students’ social relations and self-views (Kessels, 2005). When people experience a threat to belonging, a central feature of ST (Cohen & Garcia, 2008; Walton & Cohen, 2007), one strategy for regaining social acceptance is attempting to fit in by conforming to norms and/or appearing similar to the majority group (Smith & Lewis, 2009). Research has demonstrated such consequences of ST, including distancing oneself from the stigmatized group and distancing only from the stigmatized characteristics of one’s identity (e.g., women distance themselves from feminine aspects of their personality in order to fit into masculine domains such as science; Major, Quinton, McCoy & Schmader, 2000; Pronin, Steele, & Ross, 2003; von Hippel, Walsh, & Zouroudis, 2010). An alternative to distancing oneself from the stigmatized group identity is to disidentify with or disengage from the stereotyped domain (Major et al., 1998; Osborne, 1995; Schmader, Major, & Gramzow, 2001; Woodcock et al., 2012). Both of these strategies for regulating belonging are promoted by stereotype threat and may be effective at alleviating the threat, but from an educational psychology perspective these strategies would be considered unhealthy for the individual and his or her educational achievement.

Another common method for repairing one’s sense of belonging is to simply act friendlier toward others, including offering praise and demonstrating interpersonally nonverbal behaviors (Leary & Kelly, 2009). However, the salience of ST triggers a number of social appraisals, as well as emotional and behavioral responses that are likely to make it more difficult for a stigmatized student to engage others in this ingratiating manner. For example, ST makes people more defensive (Forster, Higgins & Werth, 2004), makes it more difficult to trust teachers, tests, and critical feedback (Steele et al., 2002), and makes people feel dejected (Keller & Dauenheimer, 2003). To the extent that ST is experienced as socially rejecting (Richman & Leary, 2009) research suggests that individuals respond to social rejection by prevention-related behaviors including social withdrawal and agitation (Molden, Lucas, Gardner, Dean, & Knowles, 2009). Further, when stigmatized students fear or expect discrimination from a non-minority student, the interaction is sabotaged through a pattern of reciprocal behaviors of both students in the interaction (Shelton, Richeson, & Salvatore, 2005). This interpretation of ST triggering a prevention focus toward social cues is consistent with the triggering of avoidance orientation toward achievement (Smith, 2004).

Regulating achievement orientation

Although the primary focus of the regulatory component of our model is on the motivational experiences of interest and belonging, it is important to note that students regulate motivation associated with achievement orientations and that the experience of ST may also constrain some of these options. In addition to increasing achievement-related motivation, these regulation strategies can also indirectly influence the experience of interest when they promote the use of interest-enhancing strategies. For example, Sansone et al. (1992) demonstrated that students were more likely to utilize interest-enhancing strategies in a boring activity when they were provided a good reason for doing the task. Thus, when additional value for achievement (or reasons for doing the activity) was added to increase a student’s orientation toward achievement the experience of interest indirectly benefitted. We therefore discuss efforts to regulate achievement orientations briefly because these efforts may have implications for students’ motivational experiences following triggered ST.

Students’ regulation of achievement orientations, or approach to a learning task, can take several forms, and Wolters (2003) provides an excellent review of these strategies. Rather than cover all strategies reviewed by Wolters, which is beyond the present scope, we describe a few examples of strategies that may be constrained by triggered ST. One strategy frequently used by students is to remind themselves of the importance of the learning activity (Wolters, 1998; 2003). Employing this strategy may be difficult for stigmatized students, however, because ST promotes discounting of task value (Keller, 2002; Lesko & Corpus, 2006). Students also report using goal-oriented self-talk, particularly with regard to performance goals (Wolters, 1998). Unfortunately, if students experiencing ST use this strategy it may backfire because ST promotes performance avoidance goals that subsequently negatively affect activity interest and performance (Ryan & Ryan, 2005; Smith, 2004; Smith et al., 2007). Goal-oriented self-talk typically serves to strengthen one’s present goals (Wolters, 1998), so utilizing self-talk when ST is salient may strengthen these performance avoidance goals rather than more beneficial mastery or performance approach goals.

Furthermore, when some students are concerned about performing poorly, they engage in self-handicapping (Martin, Marsh, & Debus, 2001; Riggs, 1992; Urdan & Midgley, 2001). By avoiding positive behaviors or engaging in negative behaviors related to preparation, students can discount poor performance in order to maintain positive feelings of self-esteem (Rhodewalt, 1994). Of course, these behaviors paradoxically lead to worse performance, but they are also associated with increased experience of interest because the individual is protected from the worry of performance evaluation (Deppe & Harackiewicz, 1996). Research suggests that ST promotes greater self-handicapping (Keller, 2002; Stone, 2002). By self-handicapping, not only does the student relieve anxiety related to performance evaluation, but also that her or his performance would reflect upon the abilities of his group.

Research Implications and Future Directions