Abstract

Treatment rates for hepatitis C virus (HCV) are low in actual clinical settings. However, the proportion of patients eligible for treatment, especially among those coinfected with HIV, is not well known. Our aim was to determine and compare the rates for HCV treatment eligibility among HCV and HCV-HIV-coinfected persons. We assembled a national cohort of HCV-infected veterans in care from 1998–2003, using the VA National Patient Care Database for demographic/clinical information, the Pharmacy Benefits Management database for pharmacy records, and the Decision Support Systems database for laboratory data. We compared the HCV-monoinfected and HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects for treatment indications and eligibility using current treatment guidelines. Of the 27,452 subjects with HCV and 1225 with HCV-HIV coinfection, 74.0% and 84.6% had indications for therapy and among these, 43.9% of HCV-monoinfected and 28.4% of HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects were eligible for treatment. Anemia, decompensated liver disease (DLD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), recent alcohol abuse, and coronary artery disease were the most common contraindications in the HCV, and anemia, DLD, renal failure, recent drug abuse, and COPD in the HCV-HIV-coinfected group. Among those eligible for treatment, only 23% of the HCV-monoinfected and 15% of the HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects received any treatment for HCV. Most veterans with HCV are not eligible for treatment according to the current guidelines. Even for those who are eligible for treatment, only a minority is prescribed treatment. Several contraindications are modifiable and aggressive management of those may improve treatment prescription rates.

Introduction

The current standard of care treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a combination of pegylated interferon alfa and ribavirin, which leads to sustained HCV eradication in 54–56% of the patients in clinical trials.1–3 The response rates are higher in patients infected with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 (∼80%) compared with those with HCV genotypes 1 and 4 (∼40%). Despite such advances in the pharmacotherapy of HCV, most HCV-infected persons are not initiated on treatment,4–10 and when initiated are unable to complete a full course.11 Reasons for nontreatment are poorly understood, but include nonadherence to follow-up visits, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and ongoing substance use.5,12–14 Treatment is indicated in patients with chronic HCV infection evidenced by the presence of HCV RNA, and with some degree of liver damage, evidenced by persistently elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or inflammation or fibrosis on liver biopsy.15,16 The presence of certain medical and psychiatric comorbidities including chronic kidney disease, active or uncontrolled depression, severe anemia, autoimmune disease, active substance abuse, significant coronary artery disease, and decompensated cirrhosis is considered a contraindication to treatment.15–18 Determining the proportion of HCV-infected subjects that is eligible for treatment according to the current guidelines is essential in planning effective intervention strategies at the population level. We determined the rate of treatment eligibility and contraindications to treatment in ERCHIVES (Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans), a national database of HCV-infected veterans in care at any of the Veterans Health Administration (VA) healthcare facilities.

Materials and Methods

ERCHIVES is a well-established cohort of HCV-infected Veterans and HCV-uninfected controls, and its creation has been described in previous publications.4,6,11,19–21 Briefly, we assembled a national cohort of HCV-infected veterans from the VA National Patient Care Database (NPCD), the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) data, and the Decisions Support System Database (DSS) between VA fiscal years (FY) 1998 and 2003 (October 1, 1997 through September 30, 2003). Demographic and clinical data were extracted from the NPCD. The utility and accuracy of the VA administrative and PBM data have been previously reported by our group and others.4,22–27 The NPCD contains hospitalization records including discharge diagnoses from 1970 onward. The discharge diagnoses are coded according to the Clinical Modification of International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9-CM). From 1997 onward, the NPCD also contains outpatient visit records, including diagnoses and clinic visits. The validity of ICD-9 codes has been tested previously for a range of comorbid conditions, and sensitivity, specificity, and agreement (kappa values) have been found to correlate well with chart abstractions.23,26,28 The PBM database contains records of all medications prescribed to the veterans by any of the VA pharmacies, including the dose, amount, and duration prescribed. The DSS database contains selected laboratories collected from 2000 onward during routine clinical care of veterans. For the current study we retained those subjects who had ≥1 HCV RNA and ≥2 serum alanine or aspartate aminotransferase (ALT or AST) available at or before baseline.

Our primary outcome measure was eligibility for treatment for HCV in the HCV-monoinfected and HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects based on the definitions provided below. The criteria for eligibility (presence of indications and absence of contraindications for treatment) were adapted from current treatment guidelines for HCV15,17,18 (see Table 1 for operational definitions). Subjects were considered to have HCV infection if at least one antibody test, or a qualitative or quantitative HCV RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), was positive. We determined a subject had an indication present for treatment if the HCV RNA was detectable by the standard assay being used by the local laboratory and the serum ALT or AST level was above 40 IU/ml on ≥2 occasions prior to any initiation of treatment for HCV. We then determined the presence of contraindications to treatment. The list of comorbid conditions considered a contraindication to treatment is provided in Table 1, along with the operational definitions used in this study. A diagnosis of anemia was based on the hemoglobin value preceding and closest to initiation of treatment. For our study we defined anemia as a contraindication to treatment if hemoglobin was <12.0 g/dl for men and 11.0 g/dl women, which is the definition used in the recent VA guidelines on treatment of HCV.15 If more than one hemoglobin value was recorded on the same date, the mean of the values was used. Data retrieved from the PBM included prescription of interferon alfa, pegylated interferon alfa, ribavirin, and combinations of either type of interferon with ribavirin. Prescription for HCV was defined as having received a prescription for interferon alfa, pegylated interferon alfa, or a combination of either plus ribavirin for any duration of time.

Table 1.

Operational Definitions of Contraindications to Hepatitis C Virus Therapy Used for the Current Study

| Contraindications to HCV treatment | Operational definition |

|---|---|

| Life threatening medical illness | |

| Malignancy | ≥2 ICD-9 codes any time prior to treatment |

| Coronary artery disease | ≥2 ICD-9 codes within past 12 months |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ≥2 ICD-9 codes within past 12 months |

| Uncontrolled seizures | ≥ICD-9 codes within past 12 months |

| Autoimmune disorders | ≥2 ICD-9 codes for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hepatitis, any time prior to treatment |

| Decompensated liver disease | Any of the following at anytime prior to treatment or last observation date, whichever came first: |

| INR >1.3 | |

| Albumin <2.5 g/dl | |

| Diagnosis of esophageal varices, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy | |

| Total bilirubin >2.0 mg/dl | |

| Active psychiatric illness | Any one inpatient admission with condition listed as primary reason for admission, or two or more clinic visits to a psychiatric clinic within 12 months prior to entering the cohort, or any time during follow-up |

| Recent alcohol abuse | Any primary alcohol-related admission (e.g., alcohol withdrawal syndrome, delirium tremens, alcohol rehabilitation admission, etc. with condition listed as primary reason for admission) within 12 months prior to entering the cohort, or any time during follow-up |

| Recent drug use | Any one inpatient admission with condition listed as primary reason for admission, or two or more clinic visits to a drug rehabilitation clinic within 12 months prior to entering the cohort, or any time during follow-up |

| Renal failure | Serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dl collected as an outpatient |

| Uncontrolled diabetes | ≥2 glucose levels >250 mg/dl within 12 month prior to entering the cohort or any time during follow-up (only outpatient values) |

| Moderate to severe anemia | Hemoglobin <12 g/dl for men, <11.0 g/dl for women, within 12 months prior to treatment date or last observation date |

| Neutropenia | Total white blood cell count <1.5×103 cells/mm3 |

| Heart, lung, kidney transplant | ICD-9 code at any time prior to HCV treatment; if no HCV treatment, then at any time prior to last observation date |

| Advanced HIV disease | Lowest CD4 count <100 per mm3 |

The laboratory values retrieved from the DSS included HCV antibody, HCV RNA, hemoglobin, and ALT and AST aminotransferase levels, serum albumin, bilirubin, INR, and blood glucose level. These values have been included in the DSS database from 2000 onward. To validate the DSS data, we compared data collected in DSS and the Immunology Case Registry (ICR) for 22,647 HIV+ veterans with an inpatient or outpatient visit in FY 2002 for nine laboratory tests. For six of the nine laboratory tests, DSS provided laboratory values on more individuals. Overlapping results were nearly perfectly correlated.29

To test for any bias in our final evaluable sample, we compared the demographics of our final sample with the subjects who were excluded based on nonavailability of HCV RNA levels. We also determined the prevalence of contraindications in the group of subjects with HCV infection diagnosed based on at least one inpatient and two outpatient codes, and who had evidence of liver injury based on elevation of serum ALT/AST levels.

We compared the presence of indications and contraindications for treatment in the HCV-monoinfected and HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects. The demographic characteristics were compared using the chi-square or the t-test as appropriate. The proportion of subjects with each contraindication was compared between the two groups using the chi-square test. We used Stata (version 9.2, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses.

Results

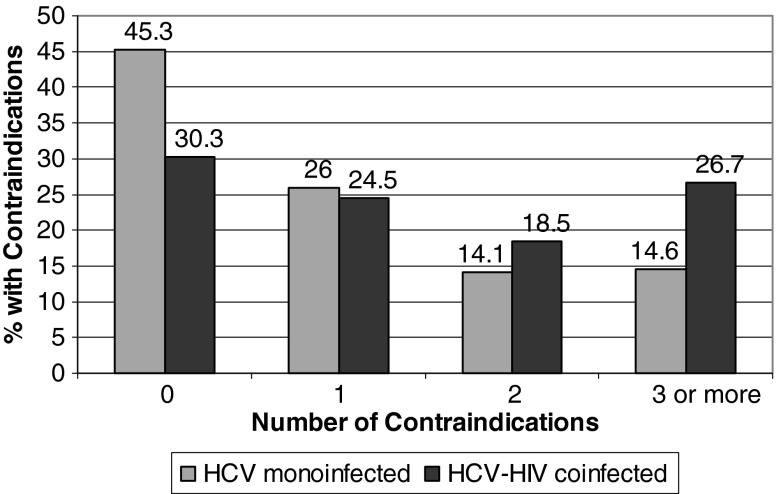

Overall, 28,677 subjects had HCV RNA levels available. Of these, 27,452 were HIV uninfected and 1225 were HIV infected. Among the HIV-uninfected group, 23,813 (86.7%) had detectable HCV RNA and 21,849 (79.6%) subjects had ≥2 elevated ALT/AST values. Among the HIV-infected group, 1127 (92.0%) had detectable HCV RNA and 1099 (89.7%) had ≥2 elevated ALT/AST values (Fig. 1). Comparing the two groups, HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects were younger and more likely to be black, but were less likely to have a diagnosis of autoimmune disease or recent alcohol use, or have been seen by a gastroenterologist/hepatologist and undergo a liver biopsy (Table 2). HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects were more likely to have anemia, decompensated liver disease, neutropenia, active psychiatric disease, recent drug abuse, and renal failure (Table 2). Among the HCV-monoinfected subjects, the 20,302 subjects who had a detectable HCV RNA as well as ≥2 serum ALT or AST levels >40 IU/ml were considered to have an indication for therapy. Of these, 11,396 (56.1%) had at least one contraindication to therapy, and the remaining 8906 (43.9%) had no contraindications to therapy, and were considered to be eligible for treatment. Among those HCV-monoinfected subjects eligible for treatment, 2045 (23.0%) received a prescription for HCV treatment (Fig. 1). Among the HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects, 1036 (84.6%) had an indication for therapy, and among those with an indication 294 (28.4%) were eligible for therapy. Among those HCV-HIV-coinfected treatment eligible subjects, only 44 (15.0%) received any prescription for HCV treatment (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Treatment eligibility, contraindications and rate of treatment prescription for hepatitis C virus (HCV) in HCV-monoinfected subjects in ERCHIVES (Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans). Contraindications listed in this figure are in the subgroup of subjects who had indications for treatment present.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics and Treatment Contraindications for Hepatitis C Virus Among HCV- and HCV-HIV-Coinfected Subjects in Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans

| HCV Only (n=27,452) | HCV and HIV coinfected (n=1225) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Mean (SD) age, years | 50.5 (7.8) | 48.6 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 46.4 | 23.8 | |

| Black | 23.9 | 53.3 | |

| Hispanic | 6.3 | 12.4 | |

| Other/unknown | 23.4 | 10.5 | |

| Gender (% male) | 96.8 | 98.4 | <0.001 |

| Liver biopsy performed | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.4 |

| Referred to GI | 65.4 | 43.4 | <0.001 |

| Contraindicationsa | |||

| Anemia (Hb <12 for men, <11 for women) | 17.5 | 42.7 | <0.001 |

| Autoimmune disorders | 1.6 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 14.8 | 12.5 | 0.2 |

| Coronary artery disease | 12.0 | 7.9 | <0.001 |

| Decompensated liver disease | 14.4 | 26.4 | <0.001 |

| Neutropenia | 0.4 | 3.3 | <0.001 |

| Organ transplant | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.005 |

| Active psychiatric disease | 6.5 | 9.5 | <0.001 |

| Recent alcohol use | 11.9 | 10.2 | 0.008 |

| Recent drug use | 6.3 | 13.4 | <0.001 |

| Renal failure (serum Cr >1.5) | 8.8 | 19.1 | <0.001 |

| Seizures | 4.9 | 5.6 | 0.003 |

| Uncontrolled diabetes | 8.0 | 7.8 | 0.1 |

Percentage of subjects with contraindications in the entire group.

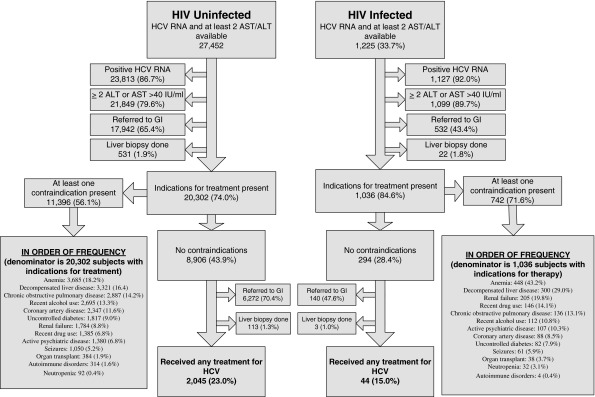

Among the HCV-monoinfected group subjects who were eligible for treatment (n=8,906) 6272 (70.4%) were seen by a gastroenterologist/hepatologist and 113 (1.3%) underwent a liver biopsy (Fig. 1). Among the HCV-HIV-coinfected group who were eligible for treatment (n=294), 140 (47.6%) were seen by a gastroenterologist/hepatologist and 3 (1.0%) underwenta liver biopsy (Fig. 1). Finally, we compared the number of contraindications to treatment in the two groups (Fig. 2). HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects were almost twice as likely to have three or more contraindications compared with the HCV-monoinfected subjects, but were significantly less likely to have zero contraindications.

FIG. 2.

Number of contraindication to HCV treatment in HCV and HCV/HIV-coinfected subjects in ERCHIVES.

A comparison of subjects who were excluded due to lack of HCV RNA with those retained for analysis was performed. For HCV-monoinfected as well as HCV/HIV-coinfected subjects, the two groups were generally comparable for demographics as well as presence of several contraindications (data not shown).

Discussion

HCV-infected persons are frequently not prescribed treatment.4–6 Various studies have reported factors associated with nonprescription of treatment, but the proportion of HCV-infected persons actually eligible for treatment per the current guidelines is not well known. We studied a large national sample of HCV-infected persons to determine treatment eligibility in HCV- and HCV-HIV-coinfected persons.

Even when indications for pharmacotherapy were present, a majority of subjects in both HCV-monoinfected and HCV-HIV-coinfected groups were ineligible for treatment due to the presence of at least one contraindication. HCV-HIV-coinfected persons were less likely to be eligible for treatment compared with the HCV-monoinfected subjects. Our finding that only ∼44% of the HCV-monoinfected and ∼28% of the HCV-HIV-coinfected persons were eligible for treatment should prompt healthcare providers and policy makers to address the modifiable contraindications to optimize care of this population.

The pattern of conditions that led to ineligibility for HCV treatment was somewhat different in the HCV-monoinfected and HCV-HIV-coinfected group. It has previously been demonstrated that HCV-HIV-coinfected persons have a higher prevalence of medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse comorbidities. We found that anemia, decompensated liver disease, renal failure, active psychiatric disease, and recent drug abuse or dependence were 1.5 to 2 times more prevalent in the HCV-HIV-coinfected persons, while coronary artery disease and alcohol use were less prevalent in the coinfected group. This is consistent with previous data comparing overall prevalence of comorbidities in these groups.4 These findings will help determine priorities for targeted intervention in both groups to improve treatment eligibility, and eventually treatment prescription. Conditions such as anemia, psychiatric disease, and substance abuse are potentially modifiable factors.

We found that HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects were less likely to be seen by a gastroenterologist/hepatologist compared with HCV-monoinfected persons. The reason for this is unclear, but possibilities include provider perception that they may be poor candidates for treatment, advanced HIV disease, and fear of drug toxicities or drug interactions. A higher prevalence of contraindications to treatment lends credence to the first possibility. CD4+ lymphocyte counts were available for 714 of the 1036 subjects who had indications for treatment; of those, 39.6% had at least one value less than 100 cells/mm3. We did not study the number of subjects on combination antiretroviral therapy, or whether such therapy led to any improvement in the CD4+ lymphocyte counts. The proportion of subjects that underwent a liver biopsy was less than 2% in each group. This is a strikingly low number, but should be interpreted with some caution, since we did not capture any biopsies that may have been performed outside the VA on a fee-for-service basis.

Even when subjects had indications for treatment and no contraindications, only a small number was prescribed treatment in either group. Treatment prescription rates were lower in the HCV-HIV-coinfected group (15%) compared with the HCV-monoinfected group (23%). The reasons for nontreatment when there are no contraindications to treatment are unclear, and need further study. It is possible that patient-, provider-, and healthcare system-level factors each plays some part in such a low level of treatment prescription for a disease that has been declared a priority in the veterans.

There are many strengths to this study. To our knowledge, this is the first national study of treatment eligibility, and directly compares HCV-monoinfected with HCV-HIV-coinfected persons. The study was conducted in veterans who received care at any of the VA medical facilities. The VA is the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, and because of the computerized integration of records, and national coverage of eligible veterans, this system is able to track, follow, and treat patients even when they move from one geographic area to another. The number of subjects suggests that the VA healthcare system is one of the largest providers of healthcare to persons infected with HCV. It has been argued that the veterans in care are a nonrepresentative sample for the U.S. population in general. Veterans are predominantly men, and have a higher prevalence of several comorbidities compared with the general population. However, most HCV-infected persons in the United States are between 30 and 49 years old, are more likely to be black, and are more likely to have a higher rate of drug use. Furthermore, the prevalence of HCV is about twice as high in men as women,30 factors similarly seem among HCV-infected veterans in care.

Despite the strengths of our analyses, limitations of the VA data and large database analyses need to be understood. We may not have captured laboratory data on many subjects.29 The diagnosis of certain comorbidities was made on the basis of ICD-9 codes. Although we took care to use a narrow time window in an attempt to include only current or active diagnoses, some conditions may change in a shorter period of time. The referral to a gastroenterologist/hepatologist was determined by the stop codes used in the VA for such visits, and the liver biopsy rates were determined based on ICD-9 and CPT procedure codes. Events may have been missed if they were not coded appropriately, or if such referrals/procedures were performed outside the VA healthcare system. We limited our final dataset to subjects who had HCV RNA as well as AST/ALT levels, since they are prerequisites in determining treatment eligibility. Only about one-third of the subjects had these laboratory values recorded. We compared the demographics of the evaluable dataset with those that were excluded, and also compared the rates of various contraindications in all subjects with diagnosis based on ICD-9 codes. The results were generally comparable in those groups, strongly suggesting that our reported data represent the overall HCV-infected veterans. Antiretroviral therapy in the HIV-coinfected group can lead to liver enzyme elevations, and this was not studied.

It is important to note that the time frame for our study was 1998–2003. In the past few years, treatment rates may have improved due to increased awareness on the part of both patients and providers, and a better understanding and management of drug-related toxicities. Although we have reported treatment prescription rates in our study, this was not its focus. Subsequent studies to determine such rates in a more recent cohort will be undertaken in the future.

In summary, most veterans with HCV are ineligible for treatment according to the current guidelines, even when they have indications for treatment. HCV-HIV-coinfected veterans are even more likely to be ineligible. Even when veterans were eligible for treatment, only a small proportion ever received any treatment. Several contraindications to treatment are potentially modifiable, and aggressive management of those may lead to better treatment prescription rates.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the central data repositories maintained by the VA Information Resource center, including the National Patient Care Database, Decisions Support System database, and the Pharmacy Benefits Management database. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author contributions: AA Butt: study design, analysis, and writing the manuscript. KA McGinnis: statistical analysis and data retrieval. M Skanderson: data retrieval and data analysis. AC Justice: study design, data analysis, and critical appraisal of the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Zeuzem S. Feinman SV. Rasenack J, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried MW. Shiffman ML. Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(13):975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadziyannis SJ. Sette H., Jr Morgan TR, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: A randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt AA. Justice AC. Skanderson M. Good CB. Kwoh CK. Rates and predictors of HCV treatment in HCV-HIV coinfected persons. Alim Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:585–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butt AA. Wagener M. Shakil AO. Ahmad J. Reasons for non-treatment of hepatitis C in veterans in care. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:81–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butt AA. Justice AC. Skanderson M, et al. Rate and predictors of treatment prescription for hepatitis C. Gut. 2007;56(3):385–389. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallinan R. Byrne A. Agho K. Dore GJ. Referral for chronic hepatitis C treatment from a drug dependency treatment setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(1):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irving WL. Smith S. Cater R, et al. Clinical pathways for patients with newly diagnosed hepatitis C–what actually happens. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13(4):264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zinkernagel AS. von W, V. Ledergerber B, et al. Eligibility for and outcome of hepatitis C treatment of HIV-coinfected individuals in clinical practice: The Swiss HIV cohort study. Antivir Ther. 2006;11(2):131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrill JA. Shrestha M. Grant RW. Barriers to the treatment of hepatitis C. Patient, provider, and system factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):754–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butt AA. McGinnis KA. Skanderson M. Justice AC. Hepatitis C treatment completion rates in routine clinical care. Liver Int. 2009;30:240–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muir AJ. Provenzale D. A descriptive evaluation of eligibility for therapy among veterans with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34(3):268–271. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falck-Ytter YM. Kale HM. Mullen KDM, et al. Surprisingly small effect of antiviral treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(4):288–292. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-4-200202190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fultz SL. Justice AC. Butt AA, et al. Testing, referral, and treatment patterns for hepatitis C coinfection in a cohort of veterans with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1039–1046. doi: 10.1086/374049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yee HS. Currie SL. Darling JM. Wright TL. Management and treatment of hepatitis C viral infection: Recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center program and the National Hepatitis C Program office. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2360–2378. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butt AA. Hepatitis C virus infection: The new global epidemic. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2005;3(2):241–249. doi: 10.1586/14787210.3.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NIH Consensus Statement on Management of Hepatitis C: 2002. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19(3):1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.APASL Hepatitis C Working Party: Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus statements on the diagnosis, management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(5):615–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butt AA. Wang X. Budoff M, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and the risk of coronary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(2):225–232. doi: 10.1086/599371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butt AA. Wang X. Moore CM. Effect of HCV and its treatment upon survival. Hepatology. 2009;50:387–392. doi: 10.1002/hep.23000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butt AA. Khan UA. McGinnis KA. Skanderson M. Kwoh CK. Co-morbid medical and psychiatric illness and substance abuse in HCV-infected and uninfected veterans. J Viral Hepatol. 2007;14:890–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozzette SA. Ake CF. Tam HK. Chang SW. Louis TA. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Eng J Med. 2003;348(8):702–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer JR. Giordano TP. Souchek J. El Serag HB. Hepatitis C coinfection increases the risk of fulminant hepatic failure in patients with HIV in the HAART era. J Hepatol. 2005;42(3):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer JR. Giordano TP. Souchek J, et al. The effect of HIV coinfection on the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in U.S. veterans with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giordano TP. Kramer JR. Souchek J. Richardson P. El Serag HB. Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected veterans with and without the hepatitis C virus: A cohort study, 1992–2001. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(21):2349–2354. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.21.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fultz SL. Skanderson M. Mole LA, et al. Development and verification of a "virtual" cohort using the National VA Health Information System. Med Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S25–S30. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223670.00890.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Justice AC. Lasky E. McGinnis KA, et al. Medical disease and alcohol use among veterans with human immunodeficiency infection: A comparison of disease measurement strategies. Med Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S52–S60. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228003.08925.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goulet JL. Fultz SL. McGinnis KA. Justice AC. Relative prevalence of comorbidities and treatment contraindications in HIV-mono-infected and HIV/HCV-co-infected veterans. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 3):S99–S105. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192077.11067.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGinnis KA. Skanderson M. Levin F, et al. Comparison of two VA laboratory data repositories indicates that missing data vary despite originating from the same source. Med Care. 2009;47(1):121–124. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d69c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong GL. Wasley A. Simard EP, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):705–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]