Abstract

Background

Promoting resilience is an aspect of psychosocial care that affects patient and whole-family well-being. There is little consensus about how to define or promote resilience during and after pediatric cancer.

Objectives

The aims of this study were (1) to review the resilience literature in pediatric cancer settings; (2) to qualitatively ascertain caregiver-reported perceptions of resilience; and (3) to develop an integrative model of fixed and mutable factors of resilience among family members of children with cancer, with the goal of enabling better study and promotion of resilience among pediatric cancer families.

Methods

The study entailed qualitative analysis of small group interviews with eighteen bereaved parents and family members of children with cancer treated at Seattle Children's Hospital. Small-group interviews were conducted with members of each bereaved family. Participant statements were coded for thematic analysis. An integrative, comprehensive framework was then developed.

Results

Caregivers' personal appraisals of the cancer experience and their child's legacy shape their definitions of resilience. Described factors of resilience include baseline characteristics (i.e., inherent traits, prior expectations of cancer), processes that evolve over time (i.e., coping strategies, social support, provider interactions), and psychosocial outcomes (i.e., post-traumatic growth and lack of psychological distress). These elements were used to develop a testable model of resilience among family members of children with cancer.

Conclusions

Resilience is a complex construct that may be modifiable. Once validated, the proposed framework will not only serve as a model for clinicians, but may also facilitate the development of interventions aimed at promoting resilience in family members of children with cancer.

Introduction

There is growing recognition that “whole-patient” cancer care must focus not only on medical therapies, but also on the psychosocial well-being of patients and their families.1 Recent literature has called for the integration of psychosocial care into standard medical oncology practice,2,3 including routine screening for psychological distress and identification of those in need of additional support.4

As with studies conducted among adult cancer patients, pediatric studies have generally focused on negative psychosocial outcomes among cancer survivors5 and family members.6 Parent mental health can influence family function as well as affect patient and sibling quality of life and physical health7–9; hence, efforts to reduce parent distress are critical.10,11

Comparatively few studies have described factors of resilience during or after cancer; however, promoting positive psychosocial outcomes is just as critical as minimizing negative ones. Indeed, post-traumatic growth (making sense or finding meaning from traumatic experiences) has been shown to moderate the effects of medical stress and improve life satisfaction among cancer survivors.12 Likewise, personal characteristics such as optimism and perceptions of the cancer experience have been related to ultimate psychological health.13,14 Studies conducted in advanced palliative care settings have shown that supportive care teams, provider interactions, and evolving social support can all mitigate caregivers' sense of powerlessness.15

Some of the challenges in resilience research are due to a lack of consensus definitions or recommendations. The concept of resilience implies an ability to withstand stress or “bounce back” from traumatic events; however, resilience research has been predominantly theoretical and has drawn from the health services, psychiatry, and psychology fields. Some argue that resilience relates to a preexisting trait that allows individuals to thrive in the face of adversity,16,17 whereas others insist it is due to a dynamic process of positive adaptation.18,19 A third conceptualization is that resilience represents a final outcome, or relatively positive state of being.20–22 Clinicians tend to define resilience as a lack of psychological distress, or a positive outcome such as quality of life or post-traumatic growth. Existing clinical studies involve variable methodologies and patient populations, precluding techniques such as meta-analysis.23 This diversity makes it difficult to develop and evaluate resilience-enhancing interventions.

Our ultimate objective was to lay groundwork for future resilience research among pediatric cancer patients and their families. We aimed to: (1) review the resilience literature in pediatric cancer settings; (2) qualitatively ascertain family-member-reported definitions of resilience and perceptions of contributing factors; and (3) develop an integrative framework of fixed and mutable factors of resilience in the setting of childhood cancer. Once evaluated and refined, this framework may form the basis for studies aimed at fostering resilience and associated positive outcomes among caregivers of children with cancer and perhaps by extension, the entire family.

Methods

Literature review

Medline, CINAHL, and PSYCInfo were searched for manuscripts indexed with the following terms, in various combinations, through March, 2012: childhood cancer, pediatric cancer, parent, caregiver, family, supportive care, psychosocial outcomes, resilience, coping, post-traumatic growth, benefit-finding, and quality of life. Titles and abstracts of all identified citations were screened and included if they involved theoretical, stated, or implied definitions of resilience. Additional manuscripts were identified from references of selected articles. Whereas pediatric cancer caregivers were the intended target of the resilience model, most of the studies reviewed did not specifically target pediatric populations. As such, the model was developed based on results extrapolated from studies in other populations and our qualitative interviews.

Small group interviews

After approval from the Seattle Children's Hospital Institutional Review Board, eight bereaved families were invited to participate in family group interviews. Eligible families were at least 2 years bereaved and were identified by their primary oncology care teams. Each interview included all interested and available family members, lasted 1.5 to 3 hours, and was conducted by the same, trained moderator who had not been previously involved in the patient's care (ARR). No incentive or compensation was offered except refreshments. The following question stems were incorporated into each interview: “What does the word ‘resilience’ mean to you?” and, “What has enabled your resilience?” Participant responses were transcribed and coded for thematic analysis using the grounded theory-based inductive process of identifying emerging themes of common responses.24 Specifically, concepts identified from the literature search were incorporated into coding for the first interview; then, coding strategies were re-addressed based on each subsequent interview.

Framework development

Literature findings were synthesized with focus group themes to develop a single conceptual framework that describes potentially modifiable elements of resilience among family members of children with cancer. The final model proposes new language to be applied in clinical settings.

Results

Literature review

The review identified exceptionally heterogenous manuscripts that we describe narratively. We identified 481 unique papers (392 with the search term “resilience”). Not all gave explicit definitions of resilience; rather, several manuscripts suggested evidence of resilience in introductory or discussion sections. Likewise, when “resilience” was not a listed key word, implied definitions were extrapolated from authors' descriptions. The majority of clinical studies were cross-sectional or retrospective evaluations of psychosocial outcomes; comparatively few were performed in prospective or longitudinal manners.

Clinical studies echoed three divergent theories that resilience is defined by pre-existing traits,16,17 evolving processes of adaptation,18,19 or psychosocial outcomes.20–22,25 For example, some authors described baseline characteristics associated with resilience, including demographics (education, income), inherent traits (optimism, hardiness, self-esteem, self-efficacy), immutable aspects of the cancer diagnosis (prognosis), and prior expectations of illness.26–34

Others used the term “process” to equate resilience with adaptation over time35 such as families' learning to deal with new demands, symptoms, lifestyles, relationships, and perceptions, as well as maintaining normalcy in the face of adversity.18,36 Evolving personal states (coping skills, spirituality, hope),16,33 social support,36 family cohesion, spousal communication, and changes in socioeconomic status37 were all associated with caregiver resilience, as were modifiable aspects of the medical experience (caregiver perceptions of the experience and associated stressors).5, 38–41 Parents with better insight into their child's prognosis were better able to set realistic goals42,43 or prepare for their child's death;43,44 such abilities may encourage more positive psychosocial outcomes.11,42–45

Finally, much of the clinical literature related resilience to positive psychosocial outcomes, a lack of adverse outcomes (comparative normalcy), or those patients and families who go on to lead psychologically healthy or productive lives.46–48 Many cited specific psychosocial outcomes as evidence for or against resilience; however, the timing of the outcome and its definition varied widely. As mentioned previously, phenomena such as post-traumatic growth and finding meaning from the cancer experience were equated with resilience because they were associated with overall psychosocial adjustment after cancer.13,14,40

Small group interviews

Seven of eight invited families (88%) and 18 total family members agreed to participate. Participants were predominantly parents; however, adult siblings and extended family members were also present (Table 1). Identified themes echoed existing resilience theories; family members described baseline characteristics, evolving processes, and psychosocial outcomes as factors of resilience. Additionally, they cited their own perceptions and appraisals of stressors and their child's legacy (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Small Group Participants and Deceased Cancer Patients

| Participant characteristics (n=18) | |

| Age range: | 22 to 65 years |

| Sex: | 8 male, 10 female |

| Relationship to deceased cancer patient: | |

| Mother | N=6 |

| Father | N=6 |

| Sibling | N=3 |

| Aunt | N=1 |

| Grandmother | N=2 |

| Cancer patient characteristics (n=7) | |

| Age range (at diagnosis): | 2 to 21 years |

| Age range (at death): | 3 to 22 years |

| Time since patient death: | 2 to 4 years |

| Sex: | 2 male, 5 female |

| Deceased patient's cancer type: | |

| Osteosarcoma | N=2 |

| Ewing sarcoma | N=1 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | N=1 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | N=1 |

| Burkitt's lymphoma | N=1 |

| Neuroblastoma | N=1 |

Table 2.

Identified Resilience Themes and Exemplary Quotes from Bereaved Family Members of Children with Cancer

| Theme | Exemplary quotes |

|---|---|

| Child legacy | • “Even though is still hurts, living my life with joy is what she would want me to do. I learned that life is short and I appreciate everything around me now. I take nothing for granted. To love others, to help others, to serve others. That will be my daughter's legacy…and now my own.” |

| • “I will live a long life and never have made the impact she did. But I sure am going to try.” | |

| • “She conquered. Even though she died, she conquered. I'm gonna’ keep conquering.” | |

| • “There is this feeling of guilt that I survived. But, I take that and incorporate it into my life. This has not defeated me.” | |

| Baseline resilience characteristics | • “I think some people have that…view on life? Thinking style? Approach to problems? I don't know, that ‘thing’ that will enable them to make it. Some don't have that. You either have it or you don't.” |

| • “Maybe we all accomplish the same thing in different ways. We all have some strength we draw from, some personal attribute that enables us to survive…but it is probably different for different people.” | |

| • “There is an aspect of cancer that is just cruel. Painful, little things on top of everything else. It mattered that we had this terrible prognosis from the beginning. We couldn't change that, so we changed what we wanted to fight for.” | |

| • “I think it depends on your background. Our education helped.” | |

| Evolving resilience | • “We had to think about what we hoped for. We had to change our goals of hope.” |

| • “Every day is different. Has different challenges. You have to adapt and change with time.” | |

| • “I don't know what we would have done without our church community. How do people do this without a community?” | |

| • “This is a family you never want to be a part of. But once you are there, that family helps. You need to let people help you.” | |

| • “The [hematology/oncology]floor was the only place we had where our joy, terror, anger, and sorrow were never judged even if we moved from one to the other quickly.” | |

| • “It was our team. The doctors, nurses…everyone. How they were there, fighting with us. That was so important.” | |

| • “Communication skill really depends on the team. When it was our primary team, that helped. We weren't prepared or willing to listen to a final answer from unfamiliar faces.” | |

| Resilience outcomes | • “I wouldn't wish this experience on anybody. But, when I look back on it, I learned something about life. About what matters.” |

| • “Cancer was a huge gift to our family in weird ways. We learned to give of ourselves.” | |

| • “My life-satisfaction is no longer defined by my job or my health. I have found other meaning in life.” | |

| • “I saw some families, you know, where a parent couldn't hold it together. Would get depressed or too stressed out. And then, they couldn't take care of their kid. Having that kind of problem makes it really hard to be resilient.” | |

| • “People live through this. I'm still worried for my own emotional health, but I also still remember to brush my teeth. Living normal and surviving this is resilience to me.” | |

| Perceptions and appraisals | • “Resilience is different for every person…every family. We don't always get to know that everything will be okay, or even what ‘okay’ means. But, we can strive for okay. Every day, we can strive for okay.” |

| • “The experience is so personal. What we value is so personal. How we fight…it is so personal.” |

Baseline resilience characteristics

Some caregivers described inherent traits as elements of resilience; for example, one parent suggested it is something “you either have…or you don't.” Another parent noted that such traits might be “different for different people.” Several caregivers noted that their child's diagnosis and the family's initial impressions thereof affected their later adjustment. Families cited their own sociodemographic characteristics as factors of resilience, including prior education, finances, family structure, and level of preexisting social support. Finally, they recognized that some aspects of the cancer experience were “out of their control,” and that resilience must be built on the foundation of these preexisting or immutable baseline characteristics.

Evolving resilience

Families described several aspects of resilience that evolved over time. First, they described changing personal states such as hope or coping skills. They recognized that the cancer experience changed daily and required variable levels of adaptation over time. Families also described changing levels of social support, not only from local communities, but also from new and developing relationships with other families. Other support came from dynamic relationships with their medical care team and other supportive care services. Caregivers described modifiable aspects of the medical experience as factors of resilience; in particular, they cited communication and provider interactions as experiences that either enabled or detracted from their ability to be resilient.

Resilience outcomes

Caregivers also described specific consequences of their cancer experience as factors of resilience. Despite the loss of their child, many had identified some benefit or meaning from the experience. Some families felt that the ability to care for themselves and other children in the home was evidence of resilience. Likewise, many felt that any level of normalcy after losing a child with cancer was indicative of resilience.

Child's legacy

One recurrent consequence, or outcome, of the cancer experience was the recognition of a child's legacy and the corresponding sense of purpose families attributed to their ultimate resilience. For example, many said that they now focused on what was important to their children. They described living to do things their children valued, or that their children had not been able to do. In addition, caregivers described their child's “fight” or “battle” with cancer, the courage their child had exhibited, and how they, as caregivers, would honor their child by continuing “to conquer life.”

Perceptions and appraisals

Finally, caregivers related resilience to their overarching perceptions and appraisals of strengths and stressors over time. They recognized that no one definition of resilience fits all; resilience factors and definitions are personal and unique to each individual.

Framework development

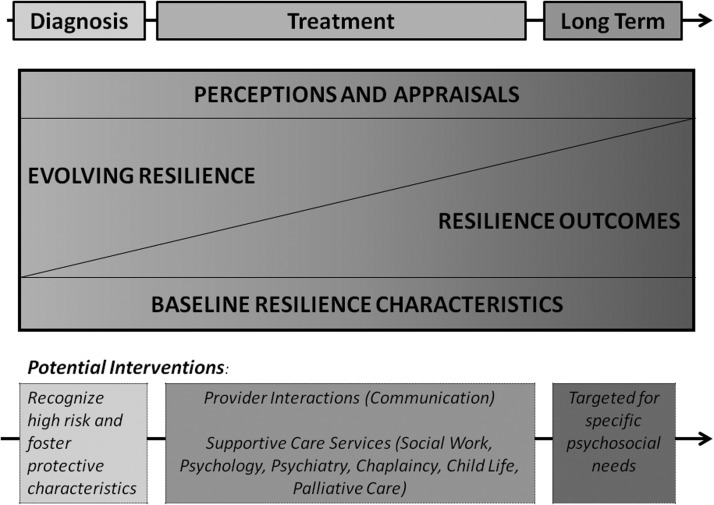

Using findings from the reviewed literature and small group interviews, we first developed a set of terminology to describe factors of resilience (Table 3). “Baseline resilience” relates to theories of inherent traits and is characterized by preexisting risk factors or strengths identified at the time of diagnosis or soon thereafter. “Evolving resilience” refers to theories of resilience as a process and includes elements of the illness experience that change over time. “Resilience outcomes” are those measures of positive or normal psychosocial functioning that develop during or after, as a consequence of, the illness. We highlighted factors that may be measured with existing, validated, standard instruments as well as those that must be more subjectively measured in clinical settings.

Table 3.

Table of Definitions Based on Small Group Results

| Baseline resilience – Suggest existing risk or resistance factors identified at the time of diagnosis or soon thereafter. | Evolving resilience – Elements of the illness experience that change over time. | Resilience outcomes– Positive measures of psychosocial functioning that develop during or after the illness. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential for modification; (Intervention) | Not modifiable; (Resilience may be enhanced by recognizing high risk and/or fostering protective characteristics.) | Potentially modifiable; (Resilience may be fostered via enhanced provider interactions [ideal communication] and supportive care services [social work, psychological, psychiatry, chaplaincy, child life, palliative care teams].) | Potentially modifiable; (Resilience may be optimized with directed interventions toward minimizing negative outcomes or encouraging of positive outcomes.) |

| Examples: |

Demographicsa – age, sex, education, family structure, baseline income Prior experience, beliefs or expectations of illnessb Inherent traitsa,b – i.e., hardiness, self-efficacy, self-esteem Medical characteristicsb – i.e., diagnosis, prognosis, duration of therapy |

Personal statesa,b – i.e., hope, humor, coping strategies Socioeconomic statusa – i.e., financial hardship Spiritualitya Family function/Cohesiona Social supporta – individual and community levels of support Medical experienceb – i.e., health care team communication, parent perceptions of prognosis, appropriate goals of therapy, decision making, involvement of interdisciplinary team |

Good care for selfa,b Good quality of lifea Post-traumatic growth,abenefit findinga Lack or low-levels of psychological distressa |

Validated standard instruments for clinical study already in existence.

Subjectively measured (suggests opportunity to develop validated instruments).

Then, we empirically created a framework of fixed and modifiable components of resilience among family members of children with cancer from the time of diagnosis, based on both literature and qualitative findings (Fig. 1). As caregivers suggested, resilience is built on a foundation of baseline characteristics that remain over time. Resilience then evolves. Like frameworks for the role of palliative care teams over the duration of an illness, different elements of resilience predominate at different time points. For example, “evolving resilience” plays a larger role early on, while patients and families are learning to cope. Over time, however, “resilience outcomes” become increasingly important and ultimately become the predominant focus. Overarching all of these factors are the subjective perceptions and appraisals of medical stressors over time, as well as the child's legacy.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual framework of resilience among caregivers of pediatric cancer patients. As reflected in the literature and by caregiver report, resilience develops over time. It is built on a foundation of baseline characteristics, evolves as patients and families adapt, and is affected by the development of specific psychosocial outcomes. Overarching all of these factors are the subjective perceptions and appraisals of strengths and stressors over time. Potential interventions may correspond to specific time points along the cancer continuum and may support each of these factors of resilience. (Please see also Table 3.)

The framework also provides suggestions for interventions. In the peri-diagnostic period, for example, resilience may be fostered by recognizing high-risk or fostering protective characteristics. During a child's treatment phase, supportive care services (social work, psychology, psychiatry, chaplaincy, child life or palliative care teams) may provide critical assistance to families and thereby affect the direction of resilience trajectories. Medical personnel may be able to directly modify the evolution of resilience by optimizing communication and thus parent perceptions and concordance with the medical team, perhaps facilitating decision making. Resilience outcomes may be targeted for specific needs as they arise. Outcomes are considered mutable in that they can be affected by directed interventions (i.e., psychiatric referrals for parents with new depression or anxiety).

Discussion

Among life's stressful events, few can be considered more difficult than that of a parent or caregiver facing the loss of a child. When present, parental distress can influence family structure and function, patient and sibling quality of life, and family survivorship as a whole.7–9 Still, many demonstrate remarkable resilience in the face of this challenge, and resilience is a critical component of overall psychosocial care. Although there is general agreement that the concept of resilience implies an ability to withstand or recover from traumatic stress including life-threatening illness, there has been debate about how to formally define, operationalize, or clinically study resilience.

Using a comprehensive literature review as well as extensive interviews with bereaved family members, we found that resilience in pediatric cancer is shaped by baseline characteristics, evolving states, and psychosocial outcomes. In the setting of pediatric cancer, it is colored by on-going perceptions and appraisals of stressors over time and illustrated by overall psychosocial well-being, functional outcomes, and a sense of purpose. Our novel framework not only integrates these findings, but it also supports longitudinal changes in patient and family needs that may enhance or detract from positive psychosocial outcomes. It provides a platform for clinicians and researchers alike to develop resilience-enhancing interventions.

Our findings are similar to family systems theories, which suggest that crises and persistent challenges impact the whole family.18 Such studies also suggest that family resilience must incorporate characteristics such as flexibility with processes of adaptation as well as outcomes such as finding meaning in adversity.18 Like other models of medical traumatic stress49 or preventative health10 for pediatric cancer patients and their families, our framework also suggests that a subset of families will have preexisting vulnerabilities that may be exacerbated by the diagnosis of cancer. Some families will develop difficulties negotiating specific challenges during their treatment. Likewise, we attempted to highlight changing goals of potential interventions at different phases of treatment. For example, early interventions may attempt to modify the subjective experience of parenting a child with serious illness, whereas later interventions may aim to mitigate negative outcomes such as parent psychological distress.

The timing and structure of such interventions remains uncertain. Prior studies of psychological interventions have demonstrated promise in decreasing distress and improving the adjustment of parents of children with cancer.50 Others have suggested methods to integrate multiple family members, but have highlighted the variability of modalities employed,51 or the challenges inherent to conducting randomized controlled trials to evaluate such interventions among parents who are already overwhelmed.52 Future studies must attempt to overcome these obstacles and better determine methods to promote resilient outcomes.

Our findings and model also raise several challenges to the existing resilience paradigms: (1) Does the absence of adverse outcomes (or “normalcy”) imply resilience? The literature in this matter is controversial53; however, the parents we interviewed argued that surviving the cancer experience without adverse psychosocial sequelae is highly indicative of resilience. They also stated that comparative normalcy (without measureable positive outcomes) should be labeled as resilience. Unfortunately, we may not recognize such families as easily as we do those with comparatively higher or lower psychosocial function. (2) Can an individual or family have positive and negative psychosocial outcomes at the same time? Historical research has often focused on a single psychosocial outcome measure; however, individuals may have evidence of both positive and negative “outcomes” at the same time. For example, a parent with anxiety may still report finding meaning from the cancer experience; how to determine if this person is “resilient” or not remains unclear. It may ultimately depend on that person's subjective opinion. (3) At what time point in a medical system is it appropriate to define an “outcome?” For example, psychological distress may develop at any time during the cancer experience; to promote resilience, providers must recognize such consequences when they develop and also understand how they affect ultimate physical and psychosocial functioning. (4) Is there a cumulative risk pattern that ultimately “tips the scale” and, if so, how do we identify this threshold? Some families may be better able to deal with progressive increases in stress levels and resilience interventions may need to recognize a tipping point. (5) How might this model vary between bereaved and nonbereaved caregivers? We suggest that elements of resilience are true in both populations (i.e., the ability to find meaning from adversity); however, there are certainly aspects of the illness and death experiences that are unique to each population. The proposed framework provides guidelines to better explore this phenomenon in diverse populations.

Our methods also had several limitations. First, our review methodologies were deliberately broad: We identified many studies whose aims were not explicitly to define resilience, but rather to subjectively describe it. We included diverse settings, both adult and pediatric populations, various study designs, and descriptions of resilience. Likewise, we included all described associations including theoretical and opinion-based, regardless of statistical significance. As such, our model remains a testable hypothesis as opposed to a proven representation of associations. It is exploratory in nature and further evaluation requires formal, confirmatory assessment of the factors and relationships described.

Second, our focus groups were conducted among a high-functioning group of individuals who willingly maintained relationships with our institution after the death of their loved one. They already embodied clinical impressions of resilience and may therefore have provided biased opinions. Likewise, the medical teams' perception of resilience does not necessarily mean that the interviewed families believed themselves to be resilient. Nevertheless, ours is one of the first descriptions of caregiver reported perspectives of resilience and therefore should serve as a starting point for future investigations.

Conclusions

The Institute of Medicine has recommended that cancer care include the provision of appropriate integrated services to optimize psychosocial outcomes.1 This “care for the whole patient” must include care for parents and family members, in particular in the setting of pediatric cancer. Our framework highlights the diverse elements of resilience among parents of children facing cancer and suggests pathways for future evaluation. In its current form, it may be used as a guideline for clinicians and researchers alike, as a platform for collaboration across disciplines, or as a model to direct future research. Ultimately, it may assist the clinical research community to design interventions that enable us to foster greater resilience among parents of children with life-threatening illness and their families.

Acknowledgments

Abby R. Rosenberg is a St. Baldrick's Foundation Fellow and was supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32CA009351 and a Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO Jane C. Wright Young Investigator Award, supported by the ASCO and the Conquer Cancer Foundation Board of Directors. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Conquer Cancer Foundation, or the ASCO and the Conquer Cancer Foundation Board of Directors.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Institute of: Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial needs. 2007. www.iom.edu/Reports/2007. [May 20;2011 ]. www.iom.edu/Reports/2007

- 2.Jacobsen PB. Wagner LI. A new quality standard: The integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1154–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fann JR. Ell K. Sharpe M. Integrating psychosocial care into cancer services. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1178–1186. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson LE. Waller A. Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: Review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1160–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazak AE. Derosa BW. Schwartz LA, et al. Psychological outcomes and health beliefs in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer and controls. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2002–2007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazak AE. Alderfer M. Rourke MT. Simms S. Streisand R. Grossman JR. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:211–219. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazak AE. Barakat LP. Brief report: Parenting stress and quality of life during treatment for childhood leukemia predicts child and parent adjustment after treatment ends. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:749–758. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.5.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vannatta K. Zeller M. Noll RB. Koontz K. Social functioning of children surviving bone marrow transplantation. J Pediatr Psychol. 1998;23:169–178. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/23.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrera M. Boyd-Pringle LA. Sumbler K. Saunders F. Quality of life and behavioral adjustment after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:427–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazak AE. Rourke MT. Alderfer MA. Pai A. Reilly AF. Meadows AT. Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: A blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1099–1110. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg AR DV. Kang T. Geyer JR. Gerhardt CA. Feudtner C. Wolfe J. Psychological distress in parents of children with advanced cancer. Arch Ped Adolesc Med. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.628. [In press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JH. Kim SG. Effect of cancer diagnosis on patient employment status: A nationwide longitudinal study in Korea. Psychooncolog. 2009;18:691–699. doi: 10.1002/pon.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel G. Taylor N. Absolom K. Eiser C. Benefit finding in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents: Further empirical support for the Benefit Finding Scale for Children. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jim HS. Jacobsen PB. Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in cancer survivorship: A review. Cancer J. 2008;14:414–419. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milberg A. Strang P. Protection against perceptions of powerlessness and helplessness during palliative care: The family members' perspective. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9:251–262. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connor KM. Assessment of resilience in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 2):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson GE. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58:307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rolland JS. Walsh F. Facilitating family resilience with childhood illness and disability. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:527–538. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245354.83454.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luthar SS. Cicchetti D. Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutter M. Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:1–12. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mancini AD. Bonanno GA. Predictors and parameters of resilience to loss: Toward an individual differences model. J Pers. 2009;77:1805–1832. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parry C. Chesler MA. Thematic evidence of psychosocial thriving in childhood cancer survivors. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(8):1055–1073. doi: 10.1177/1049732305277860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shudy M. de Almeida ML. Ly S, et al. Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: A systematic literature review. Pediatrics. 2006;118(Suppl 3):S203–S218. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0951B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pope C. Ziebland S. Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonanno GA. Westphal M. Mancini AD. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:511–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor KM. Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacelon CS. The trait and process of resilience. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:123–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ong AD. Bergeman CS. Boker SM. Resilience comes of age: Defining features in later adulthood. J Pers. 2009;77:1777–1804. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waugh CE. Fredrickson BL. Taylor SF. Adapting to life's slings and arrows: Individual differences in resilience when recovering from an anticipated threat. J Res Pers. 2008;42:1031–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim DH. Yoo IY. Factors associated with resilience of school age children with cancer. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46(7–8):431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowen EL. Work WC. Resilient children, psychological wellness, and primary prevention. Am J Community Psychol. 1988;16:591–607. doi: 10.1007/BF00922773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabkin JG. Remien R. Katoff L. Williams JB. Resilience in adversity among long-term survivors of AIDS. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:162–167. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho SM. Ho JW. Chan CL. Kwan K. Tsui YK. Decisional consideration of hereditary colon cancer genetic test results among Hong Kong chinese adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:426–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabin C. Rogers ML. Pinto BM. Nash JM. Frierson GM. Trask PC. Effect of personal cancer history and family cancer history on levels of psychological distress. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patterson JM. Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. J Marriage Family. 2002;64:349–360. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brody AC. Simmons LA. Family resiliency during childhood cancer: the father's perspective. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24:152–165. doi: 10.1177/1043454206298844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grootenhuis MA. Last BF. Adjustment and coping by parents of children with cancer: A review of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5:466–484. doi: 10.1007/s005200050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barakat LP. Alderfer MA. Kazak AE. Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:413–419. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bishop MM. Beaumont JL. Hahn EA, et al. Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1403–1411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zebrack BJ. Chesler MA. Quality of life in childhood cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:132–141. doi: 10.1002/pon.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stuber ML. Meeske KA. Krull KR, et al. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1124–1134. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ullrich CK. Dussel V. Hilden JM. Sheaffer JW. Lehmann L. Wolfe J. End-of-life experience of children undergoing stem cell transplantation for malignancy: Parent and provider perspectives and patterns of care. Blood. 2010;115:3879–3885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfe J. Klar N. Grier HE, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: Impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valdimarsdottir U. Kreicbergs U. Hauksdottir A, et al. Parents' intellectual and emotional awareness of their child's impending death to cancer: A population-based long-term follow-up study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:706–714. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mack JW. Joffe S. Hilden JM, et al. Parents' views of cancer-directed therapy for children with no realistic chance for cure. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4759–4764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davydov DM. Stewart R. Ritchie K. Chaudieu I. Resilience and mental health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:479–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haase JE. The adolescent resilience model as a guide to interventions. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21:289–299. doi: 10.1177/1043454204267922. discussion 300–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gudmundsdottir E. Schirren M. Boman KK. Psychological resilience and long-term distress in Swedish and Icelandic parents' adjustment to childhood cancer. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:373–380. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.489572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pai AL. Kazak AE. Pediatric medical traumatic stress in pediatric oncology: Family systems interventions. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:558–562. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245358.06326.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pai AL. Drotar D. Zebracki K. Moore M. Youngstrom E. A meta-analysis of the effects of psychological interventions in pediatric oncology on outcomes of psychological distress and adjustment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:978–988. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyler E. Guerin S. Kiernan G. Breatnach F. Review of family-based psychosocial interventions for childhood cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:1116–1132. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stehl ML. Kazak AE. Alderfer MA, et al. Conducting a randomized clinical trial of an psychological intervention for parents/caregivers of children with cancer shortly after diagnosis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:803–816. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonanno GA. Uses and abuses of the resilience construct: Loss, trauma, and health-related adversities. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:753–756. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]