Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive, facultative intracellular pathogen capable of causing severe invasive disease with high mortality rates in humans. While previous studies have largely elucidated the bacterial and host cell mechanisms necessary for invasion, vacuolar escape, and subsequent cell-to-cell spread, the L. monocytogenes factors required for rapid replication within the restrictive environment of the host cell cytosol are poorly understood. In this report, we describe a differential fluorescence-based genetic screen utilizing fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and high-throughput microscopy to identify L. monocytogenes mutants defective in optimal intracellular replication. Bacteria harboring deletions within the identified gene menD or pepP were defective for growth in primary murine macrophages and plaque formation in monolayers of L2 fibroblasts, thus validating the ability of the screening method to identify intracellular replication-defective mutants. Genetic complementation of the menD and pepP deletion strains rescued the in vitro intracellular infection defects. Furthermore, the menD deletion strain displayed a general extracellular replication defect that could be complemented by growth under anaerobic conditions, while the intracellular growth defect of this strain could be complemented by the addition of exogenous menaquinone. As prior studies have indicated the importance of aerobic metabolism for L. monocytogenes infection, these findings provide further evidence for the importance of menaquinone and aerobic metabolism for L. monocytogenes pathogenesis. Lastly, both the menD and pepP deletion strains were attenuated during in vivo infection of mice. These findings demonstrate that the differential fluorescence-based screening approach provides a powerful tool for the identification of intracellular replication determinants in multiple bacterial systems.

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive, facultative intracellular pathogen capable of causing severe invasive disease in humans (1). The events comprising intracellular infection by L. monocytogenes are well established (2). Host cell invasion occurs when bacteria either are phagocytosed by professional phagocytic cells or induce uptake into nonprofessional phagocytic cells. Following entry into a host cell, L. monocytogenes escapes the phagocytic vacuole to access the host cell cytosol, its primary replicative niche. Vacuolar escape is mediated by secretion of the cholesterol-dependent pore-forming cytolysin listeriolysin O (LLO) (3) and two phospholipases C, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) (4, 5) and phosphatidylcholine-specific (PC-PLC) (6). L. monocytogenes efficiently replicates within the host cell cytosol and exploits the host actin cytoskeletal machinery using a listerial surface protein, ActA, to mediate actin-based motility (7, 8). Utilizing actin-based motility, bacteria produce pseudopod-like protrusions that are taken up by neighboring cells through use of a poorly understood mechanism. Direct cell-to-cell spread and subsequent bacterial escape from double-membrane-bound spreading vacuoles (9) allow L. monocytogenes to rapidly disseminate within a host without exposure to the extracellular environment and humoral immune responses.

While previous studies have characterized L. monocytogenes invasion, vacuolar escape, and cell-to-cell spread, the bacterial and host factors necessary for efficient replication within the host cell cytosol are poorly understood. Previous genetic screens have used methicillin selection to successfully isolate L. monocytogenes mutants completely defective for intracellular replication (10, 11). However, as methicillin kills all actively replicating bacteria, this method cannot identify mutants with less severe intracellular replication defects that still permit limited bacterial growth. A screening methodology that allows for isolation of intracellular replication mutants with a greater range of replication defects would be highly informative for defining the requirements for intracellular replication of L. monocytogenes.

Differential fluorescence screening of infected host cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) has been previously used to isolate Shigella flexneri actin-based motility mutants (12) and to identify Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes genes differentially expressed intracellularly (13, 14). We adapted this technique for use in L. monocytogenes to identify bacterial genes involved in intracellular replication. Here, we describe the use of a recently developed Himar1 transposon mutagenesis system (15) to generate an L. monocytogenes transposon library amenable to differential fluorescence/FACS screening of infected host cells and the use of this library to identify bacterial genes stringently required for intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes.

Among the L. monocytogenes genes identified by the differential fluorescence screen are menD (LMRG_01292 [Broad Institute Listeria monocytogenes Database; http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/listeria_group/MultiHome.html), hepT (LMRG_01077), and the X-prolyl aminopeptidase family protein gene that we designate pepP (LMRG_00804). The menD gene encodes a 2-succinyl-5-enolpyruvyl-6-hydroxy-3-cyclohexene-1-carboxylate synthase, which is the first dedicated enzyme in the menaquinone biosynthesis pathway. Previous work by Stritzker and colleagues has shown that aro mutant strains of L. monocytogenes are auxotrophic for menaquinone and severely defective for intracellular growth and virulence in vivo (16). Members of the X-prolyl aminopeptidase protein family hydrolyze small peptides and are thought to play a role in bacterial protein turnover. While a pepP (lmo1354) Himar1 insertion mutant was recently identified by Zemansky and coworkers in a blood agar plate screen for L. monocytogenes hypohemolytic mutants (15), pepP has not been previously implicated in bacterial virulence. Using in-frame deletion mutants, we demonstrate that menD and pepP are necessary for optimal intracellular replication of L. monocytogenes during in vitro infection of cultured host cells and contribute to in vivo virulence in a murine infection model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani, medium and all Listeria monocytogenes strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Difco, Detroit, MI) medium. All bacterial stocks were stored at −80°C in BHI medium supplemented with 40% glycerol. The following antibiotics were used at the indicated concentrations: carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 30 μg/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; erythromycin, 3 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 7.5 μg/ml (L. monocytogenes) or 20 μg/ml (E. coli); and gentamicin, 10 to 50 μg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Cell culture.

Murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) were prepared as previously described (17). Briefly, femurs were removed from 6- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), and bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 7.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT), 2 mM glutamine, and 100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin (P-S) and then washed once with DMEM. Cells were cultured in 100-mm-diameter non-tissue-culture-treated petri dishes (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY) for 3 days in BMM medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μg/ml P-S, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol [BME], and 30% L-cell-conditioned medium). On day 3, fresh BMM medium was added to cultures. On day 6, BMM were harvested by the removal of medium, the addition of cell-harvesting solution (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 0.7 mM EDTA, and 3% FBS), and incubation at 4°C for 25 min. BMM were then plated as indicated for 18 to 24 hours prior to experiments. Murine L2 fibroblasts were grown in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 100 μg/ml P-S. All cell cultures were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Plasmid and strain construction.

The bGFP cassette (pHyper-hly 5′ untranslated region-green fluorescent protein [GFP] gene [18]) from pPL3-bGFP was amplified using primers bGFPforward and bGFPreverse and ligated into pIMK using the BamHI and SalI restriction sites to generate pIMK-bGFP. Electrocompetent L. monocytogenes strains were prepared as previously described (15). pIMK-bGFP was electroporated into DH-L487 to generate strain DH-L1956.

In-frame menD and pepP deletion alleles were produced by splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) as previously described (19). The resulting ΔmenD and ΔpepP PCR products were ligated into pKSV7 using the HindIII/EcoRI and PstI/KpnI restriction sites, respectively, to generate pKSV7 ΔmenD and pKSV7 ΔpepP. pKSV7 ΔmenD and pKSV7 ΔpepP were electroporated into 10403S, and allelic exchange was induced as previously described (20) to generate strains DH-L2036 and DH-L2039, respectively. Complementing plasmids were produced by amplifying the menD and pepP open reading frames (ORFs) from 10403S genomic DNA with primer pairs pLOVmendfor/pLOVmendrev and pLOVpepPfor/pLOVpepPrev and ligating the resulting PCR products into pLOV using the ClaI and KpnI restriction sites to generate pLOV-menD and pLOV-pepP, respectively, placing expression of the cloned genes under constitutive control of the pHyper promoter and ermC ribosome binding site (RBS) (21). pLOV and pLOV-menD were electroporated into DH-L2036 to generate strains DH-L2037 and DH-L2038, respectively. pLOV and pLOV-pepP were electroporated into DH-L2039 to generate strains DH-L2041 and DH-L2042, respectively. All PCR amplifications for cloning were performed using PfuTurbo DNA Polymerase AD (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. All plasmids and strains were verified by DNA sequencing.

Generation of Himar1 transposon libraries.

Approximately 1 μg of pJZ037 was electroporated into six aliquots of electrocompetent DH-L1956. Bacteria were recovered in 1 ml of vegetable peptone broth (Remel, Lenexa, KS) with 0.5 M sucrose and plated on ∼20 plates of BHI plus erythromycin (BHI-erythromycin plates). Following incubation at 30°C for 48 hours, transformant colonies were replica plated onto BHI-erythromycin plates and incubated at 42°C for 16 to 18 hours for plasmid curing. Colonies from all six electroporations, representing over 100,000 colonies, were then pooled and resuspended in BHI plus 40% glycerol to generate a transposon library designated strain DH-L2021.

FACS and flow cytometry.

DH-L2021 aliquots or selected strains were grown in BHI plus kanamycin plus erythromycin with shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C for 14 or 18 hours, respectively, prior to use. BMM (5 × 106) were seeded into 60-mm-diameter non-tissue-culture-treated petri dishes (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY) at 18 hours prior to infection. BMM were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 by replacing the culture medium with fresh medium containing DH-L2021. At 1 hour postinfection, BMM were washed three times with PBS and fresh medium containing 50 μg/ml gentamicin was added to kill extracellular bacteria. At 6 hours postinfection, BMM were harvested as described above and resuspended in PBS with 1% FBS for FACS or flow cytometry. FACS collection of the indicated GFPlow gate was performed using a FACSAria system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at the Flow and Imaging Cytometry Resource (http://flowimagingcytometry.org/) at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). Eight percent (∼46,924 of 586,560), 9.2% (∼102,391 of 1,112,179), and 40% (∼196,019 of 490,049), respectively, of the recovered GFPlow BMM from three independent FACS sorts were then plated onto BHI-kanamycin-erythromycin plates to recover intracellular bacteria. Colonies (6,800 total) were picked and arrayed into the wells of 1-ml-deep-well 96-well plates containing BHI plus kanamycin plus erythromycin and grown for 16 hours at 25°C without shaking. Aliquots of bacterial cultures were then mixed with sterile glycerol to a final concentration of 40% glycerol in separate wells of 200-μl 96-well plates and stored at −80°C. Analysis of flow cytometry data was performed using FloJo analysis software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Fluorescence microscopy counterscreen.

BMM (5 × 104) were seeded into clear-bottom, black-wall 96-well plates (Corning Costar, Corning, NY). Sixteen hours later, BMM were infected at an MOI of 1 with the above-described arrayed putative intracellular replication mutants. At 1 hour postinfection, gentamicin was added to each well to a final concentration of 40 μg/ml to kill extracellular bacteria. At 6 hours postinfection, the medium was removed and BMM were washed once with PBS and fixed with 3.2% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 18 hours at 4°C. BMM were then washed and stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in PBS for 10 min at 25°C. Fluorescence microscopy images were acquired at 4 positions per well using an ImageXpress Micro automated microscope system and analyzed using MetaMorph image analysis software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at the ICCB-Longwood Screening Core Facility (http://iccb.med.harvard.edu) at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). Images were scored to identify mutants producing GFPdown infections (mutants exhibiting a discernible reduction in GFP fluorescence intensity by visual inspection). Mutant bacteria producing GFPdown infections compared to DH-L1956 infections in two independent experiments were identified as intracellular replication mutants and subjected to further study. False-positive mutants (those lacking GFP expression) were identified by GFP fluorescence plate reading of 18-hour BHI cultures using the Fluorskan Ascent FL system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Mutants that produced less than 50% of DH-L1956 GFP fluorescence were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Identification of transposon insertion sites.

Himar1 insertion sites were identified by amplifying the insertion junctions using a two-round semiarbitrary PCR. Bacteria from single colonies of intracellular replication mutants were used as templates in 25-μl PCR mixtures containing 1× ThermPol buffer, 0.5 μg/μl bovine serum albumin (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTPs) (Promega, Madison, WI), 1.24 M betaine monohydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.2 μM (each) primers ARB1 and marK3, and 1.67 U Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) using PCR program 1. One microliter of the first-round PCR product was then used as the template for a second-round PCR as indicated above with primers ARB2 and marK4 using PCR program 2. PCR products from the second PCR were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions and submitted to the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center DNA Resource Core (http://dnaseq.med.harvard.edu) at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA) for sequencing with primer marK4. PCR program 1 was as follows: 1 cycle of 91°C for 2 min; 6 cycles of 91°C for 15 s, 29°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 75 s; 30 cycles of 91°C for 15 s, 52°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 75 s; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 5 min. PCR program 2 was as follows: 1 cycle of 91°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 91°C for 15 s, 52°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 2 min; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 5 min.

Transductions.

Transductions were performed as previously described using the phage P35 (22). Briefly, 1 × 107 phage particles raised on selected donor strains were incubated with 1 × 108 10403S bacteria and plated for 48 hours on BHI-erythromycin plates. Himar1 transposon site locations in recovered transductants were verified as described above.

In vitro growth analysis.

Sixteen-hour cultures of the indicated strains were diluted 1:50 in triplicate in BHI plus chloramphenicol and grown with shaking at 37°C. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the triplicate cultures was measured every 30 min and averaged. To measure anaerobic growth, BHI-erythromycin was equilibrated with the atmosphere in an anaerobic chamber for 16 hours and then used to inoculate 5-ml cultures of the indicated strains, which were then incubated without shaking at 25°C. Sixteen hours later, cultures were diluted 1:50 in triplicate in fresh degassed medium. Cultures were then grown anaerobically in a rolling drum at 37°C and the OD600 measured every 30 min and averaged.

L2 fibroblast plaquing assay.

Murine L2 fibroblast plaquing assays were performed as previously described (23) with minor modifications. Briefly, 2 ×106 L2 cells per well were seeded into 6-well plates. Sixteen hours later, L2 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.03 by replacing the medium with fresh medium containing the indicated strains, which were grown in BHI-chloramphenicol for 16 hours at 30°C without shaking. At 1 hour postinfection, L2 cells were washed three time with cold PBS and overlaid with 0.7% agarose in DMEM plus 30 μg/ml gentamicin. At 72 hours postinfection, a second agarose overlay containing neutral red (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to aid visualization of plaques. Sixteen hours later, the tissue culture plates were scanned and plaque size measured using Canvas X (ACD Systems, Miami, FL). Ten plaques per strain were measured to determine mean plaque size.

Intracellular growth assay.

Intracellular growth assays were performed as previously described (17). Briefly, 4 × 105 BMM were seeded in 24-well plates. Sixteen hours later, BMM were infected at an MOI of 1 by replacing the medium with fresh medium containing the indicated strains, which were grown in BHI-chloramphenicol for 16 hours at 30°C without shaking. At 1 hour postinfection, BMM were washed three times with PBS and supplemented with fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. At the indicated time points, the number of intracellular bacteria was determined by removing the medium from wells and lysing host cells with 1.0% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS. Dilutions of host cell lysates were then plated on BHI-chloramphenicol plates and grown for 24 hours at 37°C to allow enumeration of bacteria. Where noted, tissue culture medium was supplemented with 50 μg/ml menaquinone (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA). Values given are the mean for three wells per strain per time point.

In vivo virulence assessment.

In vivo infections were performed as previously described (3). Briefly, 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were injected intravenously with 1.23 × 104 to 1.56 × 104 bacteria of the indicated strains, which were grown in BHI-streptomycin for 16 hours at 30°C without shaking. Seventy-two hours later, mice were euthanized and livers and spleens were harvested and homogenized in 5 ml of PBS. The bacterial burdens in organs were determined by plating dilutions of organ homogenates on BHI agar plates plus streptomycin followed by 24 hours of incubation at 37°C to allow enumeration of bacteria. All animal studies were performed in accordance with IACUC regulations.

RESULTS

A FACS/fluorescence microscopy-based genetic screen for L. monocytogenes intracellular replication mutants.

To identify bacterial genes involved in the intracellular replication of L. monocytogenes, we developed a transposon screen based on differential fluorescence of infected host cells. We constructed a Himar1 transposon library in a constitutive GFP-expressing ΔactA mutant of L. monocytogenes strain 10403S (DH-L2021). Since ΔactA L. monocytogenes is defective in actin-based motility and cell-to-cell spread (24), host cells infected at a low multiplicity of infection with the DH-L2021 transposon library remain clonally infected with a single Himar1 insertion mutant. As a result, the GFP fluorescence intensity of a host cell during the course of infection directly correlates with the number of mutant bacteria replicating within the host cell and therefore with the growth rate of the individual mutant bacterial strain. Utilizing this principle, host cells infected with DH-L2021 transposon mutants that exhibit a lower GFP fluorescence intensity than host cells infected with the screening background strain (DH-L1956) are considered GFPdown cells. FACS collection of GFPdown host cells allows the recovery of L. monocytogenes mutants harboring transposon insertions within genes contributing to intracellular bacterial replication.

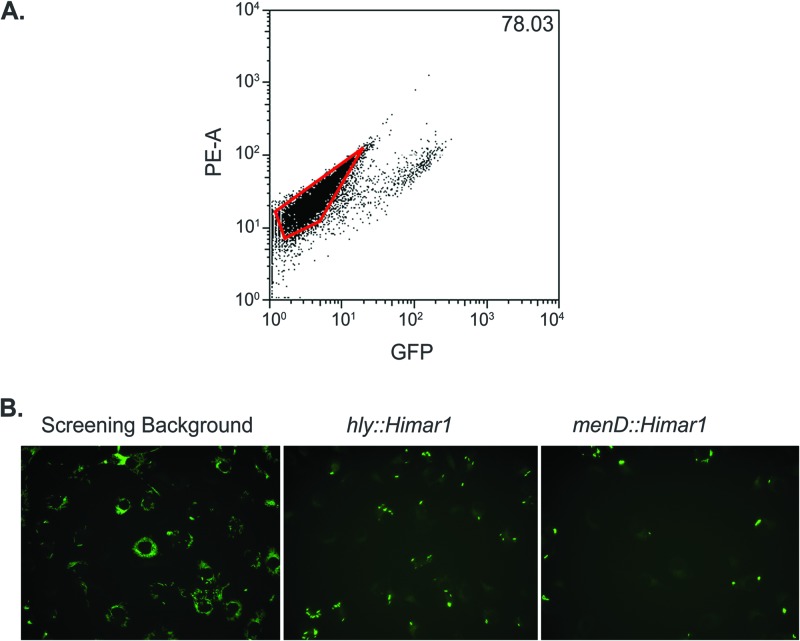

A screen was performed to isolate severely intracellular replication-defective mutants, as the difference in GFP fluorescence intensity between a host cell infected with a strongly growth-attenuated mutant and a growth-neutral mutant would be the greatest observed and thus the easiest to differentiate by FACS. To screen for severe intracellular replication mutants in a physiologically relevant context, 5 × 106 primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) were infected with the DH-L2021 transposon library at an MOI of 1. At 6 hours postinfection, BMM displaying host cell GFP autofluorescence intensities were recovered by FACS (Fig. 1A). A total of 6,800 Himar1 insertion mutants were isolated following three independent infection/FACS events, representing all colonies arising after plating 8%, 9.2%, and 40%, respectively, of the recovered GFPlow BMM. To confirm the presence of intracellular replication defects, the 6,800 transposon mutants were analyzed in a secondary counterscreen using automated fluorescence microscopy of infected BMM (Fig. 1B). Additionally, to eliminate GFP transposon insertion mutants, GFP expression from broth cultures of all transposon mutants was determined using a fluorescence plate reader, and transposon mutants producing less GFP fluorescence than the screening background strain (DH-L1956) were discarded from further analysis. Following the fluorescence microscopy counterscreen, a total of 12 GFP-positive (GFP+) Himar1 insertion mutants were found to result in GFPdown BMM infections in two independent experiments. The Himar1 insertion site within each L. monocytogenes mutant (Table 1) was then determined by semiarbitrary PCR.

Fig 1.

Differential fluorescence/FACS microscopy screen for L. monocytogenes intracellular replication mutants. (A) Representative FACS plot of DH-L2021-infected BMM during FACS. BMM (5 × 106) were infected at an MOI of 1 with DH-L2021. At 1 hour postinfection, BMM were washed and medium with gentamicin was added to kill extracellular bacteria. At 6 hours postinfection, BMM were harvested and subjected to FACS. Host cell GFP fluorescence and phycoerythrin channel autofluorescence (PE-A) are plotted. GFPdown BMM (outlined gate) were collected to recover intracellular bacteria. Three independent FACS collections were performed. The value given represents the percentage of GFPdown BMM in the infection. (B) Fluorescence microscopy counterscreening of post-FACS-recovered mutants. BMM (5 × 104) were infected as described above with individual post-FACS-recovered mutants, and at 6 hours postinfection BMM were fixed and subjected to automated fluorescence microscopy. Shown are images of BMM infected with the screening background strain DH-L1956 (left), DH-L1956 harboring a Himar1 insertion in hly, which is deficient in vacuolar escape (middle), and a representative GFPdown mutant isolated from the above-described FACS screen (right).

Table 1.

Recovered intracellular replication mutants

| Gene | No. of insertions recovered |

|

|---|---|---|

| Himar1 insertions | Independent insertions | |

| prfA (LMRG_02622) | 3 | 2 |

| hly (LMRG_02624) | 4 | 3 |

| menD (LMRG_01292) | 1 | 1 |

| hepT (LMRG_01077) | 1 | 1 |

| pepP (LMRG_00804) | 1 | 1 |

Multiple independent Himar1 insertions within the prfA and hly genes were recovered. As both genes are known to be required for L. monocytogenes intracellular replication and virulence (3, 25), the recovery of transposon insertions within known virulence genes validated the ability of the differential FACS/fluorescence microscopy screen to identify genes required for L. monocytogenes intracellular replication. Furthermore, single Himar1 insertions were recovered in five additional genes (Table 1). Adenylosuccinate synthetase (LMRG_02498) is a protein involved in purine biosynthesis. A previous study has shown that an L. monocytogenes adenine auxotroph is attenuated during in vivo infection of mice (26). plsX (LMRG_00956) encodes an enzyme mediating the activation of acyl chain moieties during phospholipid synthesis in most Gram-positive bacteria (27, 28). As plsX is essential in the closely related bacterium Bacillus subtilis (29) and no additional L. monocytogenes plsX homologs were identified by a BLAST search of the genome, we hypothesize that plsX may be essential for L. monocytogenes growth in general and that the recovered insertion mutant produces a less stable or less active variant of the protein. The finding that the recovered plsX Himar1 insertion maps to the extreme C terminus of the open reading frame supports this hypothesis. LMRG_00804 is annotated by the Broad Institute Listeria monocytogenes Database as encoding an X-prolyl aminopeptidase. Members of this protein family cleave the N-terminal amino acid of small peptides containing a proline residue at the second position (30) and are thought to play a role in general protein turnover in bacteria (31). As the corresponding gene has been designated pepP in the previously sequenced L. monocytogenes strain M7 (32), we have designated LMRG_00804 pepP. menD (LMRG_01292) encodes the menaquinone biosynthetic enzyme catalyzing the addition of 2-oxoglutarate to isochorismate to generate 2-succinyl-5-enolpyruvyl-6-hydroxy-3-cyclohexene-1-carboxylate (33), and hepT (LMRG_01077) encodes the heptaprenyl diphosphate synthase component II, a protein involved in the synthesis of the heptaprenyl moiety that anchors menaquinone to the plasma membrane (34, 35). Interestingly, L. monocytogenes lacks the genes necessary for ubiquinone biosynthesis and therefore requires menaquinone to complete a functional electron transport chain.

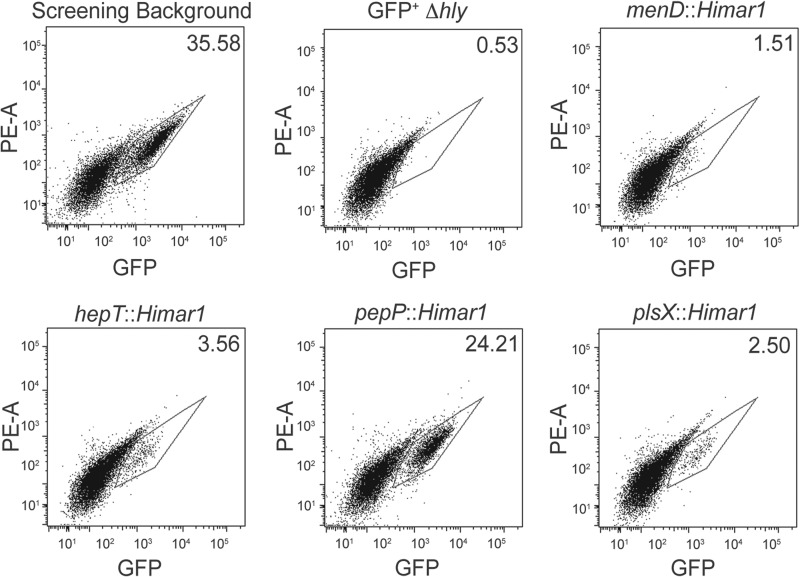

To further verify the GFPdown phenotype of the mutants recovered in the differential fluorescence screen, we used flow cytometry to determine the GFP fluorescence intensity profiles of BMM infected with individual isolated transposon mutants (Fig. 2). As an L. monocytogenes strain containing a deletion of hly (the gene encoding LLO) does not effectively escape the phagocytic vacuole and replicate intracellularly, only 0.53% of BMM infected with a GFP-expressing Δhly strain (GFP+ Δhly; DH-L1958) were GFPhigh (defined as a GFP fluorescence intensity greater than host cell autofluorescence). In contrast, 35.58% of BMM infected with the DH-L1956 screening background strain were found to be GFPhigh. Consistent with the fluorescence microscopy results, 1.51% of BMM infected with the menD insertion mutant (DH-L2024) and 3.56% of BMM infected with the hepT insertion mutant (DH-L2025) were found to be GFPhigh (Fig. 2). Similarly, only 2.50% of BMM infected with the plsX insertion mutant (DH-L2027) were found to be GFPhigh. In contrast, BMM infected with the pepP insertion mutant (DH-L2026) did not exhibit as great an infection defect as measured by flow cytometry, resulting in 24.21% of BMM infected with DH-L2026 being GFPhigh. The finding that all of the recovered transposon mutants resulted in reduced GFPhigh BMM populations further validates the ability of the differential fluorescence screening approach to identify L. monocytogenes genes necessary for optimal intracellular infection.

Fig 2.

Flow cytometry of BMM infected with individual intracellular replication mutants. BMM (5 × 106) were infected as described for Fig. 1 with the screening background strain (DH-L1956), 10403S Δhly + pIMK-bGFP (DH-L1958), or isolated screening background strain mutants bearing Himar1 insertions in the indicated genes. At 6 h postinfection, BMM were harvested and subjected to flow cytometry. Values given represent the percentage of GFPhigh BMM (gate) in each infection. Flow cytometry data are representative of three independent experiments.

In vitro characterization of ΔmenD and ΔpepP strains.

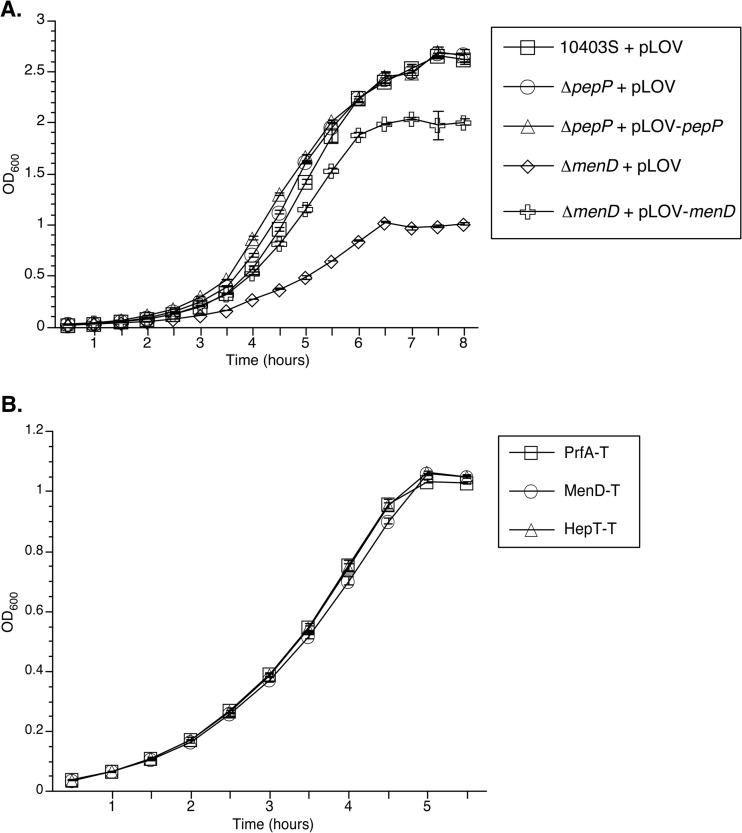

After eliminating L. monocytogenes genes identified by the differential fluorescence screen which were presumably essential for general bacterial growth, had been previously implicated to play a role during intracellular infection, or, in the case of hepT, participated in the same biosynthetic pathway as another identified gene, we selected menD and pepP for further study. To determine whether the contribution of menD and pepP to L. monocytogenes growth is specific to intracellular replication or a general requirement, we measured the replication of ΔmenD and ΔpepP in-frame deletion strains during growth in broth culture (Fig. 3). The ΔmenD strain harboring the pLOV expression vector (ΔmenD + pLOV) displayed a significant growth defect during aerobic growth in BHI broth, while the menD complementation strain (ΔmenD + pLOV-menD) displayed a partial (>50%) restoration of the growth defect compared to wild-type bacteria (10403S + pLOV) (Fig. 3A). This result suggests that the decrease in intracellular replication of the menD insertion mutant observed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2) is primarily due to a general growth defect. However, both the ΔpepP strain harboring pLOV (ΔpepP + pLOV) and the pepP complementation strain (ΔpepP + pLOV-pepP) displayed wild-type growth levels in BHI (Fig. 3A). This result suggests that the decrease in intracellular infection by the pepP insertion mutant observed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2) is due to a specific intracellular growth defect resulting from the lack of PepP. As previous work by Stritzker and coworkers demonstrated that the slow growth of L. monocytogenes aro deletion strains could be rescued by either the addition of exogenous menaquinone or anaerobic growth conditions (16), we examined the growth of menD and hepT Himar1 insertion mutants under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 3B). When grown in degassed BHI broth, the menD and hepT transductant strains (MenD-T and HepT-T, respectively) displayed growth identical to that of a neutral transposon mutant, PrfA-T (prfA is dispensable for anaerobic growth of L. monocytogenes [data not shown]). This result suggests that the growth defects observed with the menD and hepT mutants are strictly aerobic phenotypes and that the decrease in intracellular replication of these mutants is due to a defect in aerobic metabolism during intracellular infection.

Fig 3.

In vitro growth of intracellular replication mutants. (A) Aerobic growth of intracellular replication mutants. Sixteen-hour cultures of the indicated strains were diluted 1:50 in triplicate in BHI-chloramphenicol and grown with shaking at 37°C. The OD600s of the triplicate cultures were measured every 30 min and averaged (± standard deviation [SD]). (B) Anaerobic growth of suspected electron transport chain mutants. Cultures of the indicated strains were grown for 16 hours without shaking in degassed BHI-erythromycin in an anaerobic chamber at 25°C and then diluted 1:50 in triplicate in fresh degassed medium. Cultures were then grown anaerobically in a rolling drum at 37°C and the OD600 measured every 30 min and averaged (±SD). The data are representative of three independent experiments.

We next determined the ability of the ΔmenD and ΔpepP strains to undergo productive intracellular infection by measuring plaque formation in monolayers of L2 fibroblasts (Table 2). Plaque formation by L. monocytogenes requires the sequential events of host cell invasion, vacuolar escape, intracellular replication, actin-based motility, and cell-to-cell spread; defects in any of these processes results in a decrease in plaque size. Previous studies have shown that the magnitude of the plaquing defect correlates well with the severity of in vivo virulence defects of L. monocytogenes strains. The ΔmenD + pLOV strain failed to produce any visible plaques, indicating that the product of the menD gene is absolutely required for productive intracellular infection. The ΔpepP + pLOV strain displayed a 22.2% decrease in plaque size compared to the wild type (10403S + pLOV). This defect is comparable to the plaquing defects observed for plcA and plcB deletion strains (36) (plcA and plcB encode PI-PLC and PC-PLC, respectively). This result suggests that the pepP gene product is required for optimal intracellular infection by L. monocytogenes. Furthermore, the menD and pepP complementation strains fully rescued the plaquing defects of the corresponding deletion strains (Table 2), demonstrating that the observed plaquing defects are due solely to the absence of menD or pepP.

Table 2.

Plaque formation by intracellular replication mutants

| Genotype | Plaque size (%)a |

|---|---|

| 10403S + pLOV | 100 ± 2.5 |

| ΔmenD + pLOV | No plaques |

| ΔmenD + pLOV-menD | 97.7 ± 3.4 |

| ΔpepP + pLOV | 77.8 ± 3.3 |

| ΔpepP + pLOV-pepP | 95.9 ± 3.4 |

Plaque size values are the means ± SD for 10 plaques per strain compared to wild-type (10403S + pLOV) plaque size. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

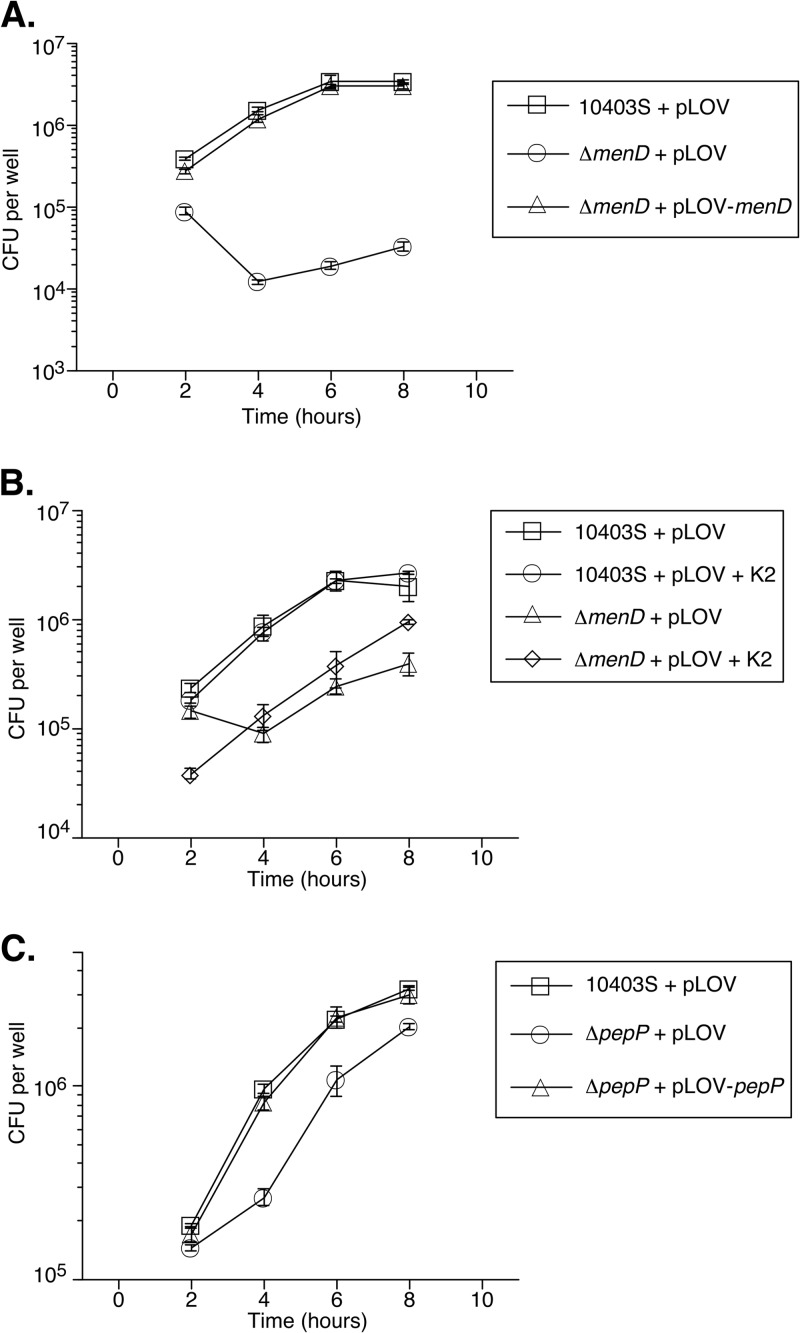

As the L2 plaquing defects observed with the ΔmenD and ΔpepP strains indicated that these genes play a role in one or multiple processes necessary for productive intracellular infection, we next measured the contribution of menD and pepP specifically to intracellular replication. BMM were infected with the ΔmenD or ΔpepP strain, and at multiple time points postinfection, host cells were lysed and plated to enumerate intracellular bacteria (Fig. 4). While the number of intracellular ΔmenD + pLOV bacteria decreased 10-fold between 2 and 4 hours postinfection before slowly increasing at later time points, the menD complementation strain displayed wild-type intracellular growth throughout the infection period (Fig. 4A). Additionally, during infection of nonbactericidal L2 fibroblasts, the ΔmenD + pLOV strain showed no initial decrease in bacterial numbers, with only a 4-fold increase in bacteria during the 8-hour infection. In contrast, wild-type bacteria (10403S + pLOV) and the menD complementation strain displayed a 55-fold increase in bacterial numbers over the same infection period (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). These data suggest that the menD deletion strain is initially more susceptible to killing by the macrophages and that the bacteria replicate dramatically more slowly than wild-type bacteria within host cells. As Stritzker and colleagues had previously shown that exogenous menaquinone rescued the aerobic growth defect of aro deletion strains during growth in broth culture (16), we examined the ability of exogenous menaquinone to rescue the intracellular growth defect of ΔmenD + pLOV bacteria. Whereas the addition of 50 μg/ml menaquinone to the tissue culture medium did not affect the growth of wild-type bacteria, supplementation of exogenous menaquinone fully rescued the growth defect of ΔmenD + pLOV bacteria (Fig. 4B). This result suggests that the observed intracellular replication defect of ΔmenD + pLOV bacteria is due solely to the lack of menaquinone and disruption of aerobic metabolism, providing further evidence for the important role that this process plays during intracellular pathogenesis of L. monocytogenes.

Fig 4.

Intracellular growth of ΔmenD and ΔpepP mutants. (A) Intracellular growth of ΔmenD strains in BMM. BMM (4 × 105) were infected with the indicated strains at an MOI of 1. At 1 h postinfection, BMM were washed and medium with gentamicin added to kill extracellular bacteria. At the indicated time points, BMM in three wells per strain were lysed with 1.0% Triton X-100 and the number of intracellular bacteria determined by plating on agar medium. CFU per well per strain were then averaged (±SD). (B) Menaquinone complementation of ΔmenD. BMM were infected as described above with the indicated strains in the presence or absence of 50 μg/ml menaquinone (K2). (C) Intracellular growth of ΔpepP strains. BMM were infected as described above with the indicated strains. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments.

In contrast to the case for ΔmenD + pLOV bacteria, the intracellular replication rate of ΔpepP + pLOV bacteria was reduced between 2 and 4 hours postinfection before becoming comparable to that of wild-type bacteria, suggesting that the intracellular replication defect of the ΔpepP strain stems from a defect early in the intracellular infection process in BMM (Fig. 4C). As observed with the plaquing experiments, the pepP complementation strain displayed wild-type intracellular growth throughout the infection period (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, ΔpepP + pLOV bacteria displayed no intracellular growth defect during an 8-hour infection of L2 fibroblasts (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Intracellular replication of L. monocytogenes during the first 8 hours of infection is predominantly restricted to initially infected host cells. As the pepP deletion strain displays a 22% plaquing defect in L2 cells (Table 2), during which multiple rounds of intracellular replication and cell-to-cell spread occur, this result suggests PepP is dispensable for intracellular replication in L2 cells but may contribute to an aspect(s) of bacterial cell-to-cell spread.

ΔmenD and ΔpepP strains are attenuated during in vivo infection.

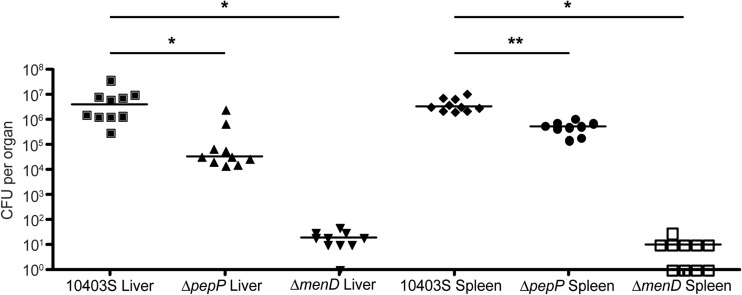

To assess the contribution of menD and pepP to L. monocytogenes virulence, we infected BALB/c mice intravenously with wild-type (10403S), ΔmenD (DH-L2036), or ΔpepP (DH-L2039) bacteria and at 72 hours postinfection harvested livers and spleens and plated dilutions of homogenized organs to determine the bacterial burden in each organ (Fig. 5). Infection with the ΔmenD mutant resulted in a 105-fold decrease in liver and splenic burdens (P < 0.0001 by the Mann-Whitney test), while infection with ΔpepP L. monocytogenes resulted in 100-fold and 6.4-fold decreases in liver and splenic burdens, respectively (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0004, respectively, by the Mann-Whitney test), compared to those in wild-type infected mice. Additionally, the pepP complementation strain produced wild-type bacterial burdens during infection of BALB/c mice, while infection with the menD complementation strain resulted in a 103-fold increase in liver and splenic burdens compared to infection with the parental ΔmenD strain (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These data demonstrate the importance of menD and pepP during in vivo infection by L. monocytogenes.

Fig 5.

In vivo growth of ΔmenD and ΔpepP mutants. Six- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were infected with 1.0 × 104 to 1.6 × 104 bacteria of the indicated strains by tail vein injection. At 72 hours postinfection, mice were euthanized and livers and spleens were harvested. Harvested organs were then homogenized, and dilutions were plated to allow enumeration of bacteria. *, P < 0.0001; **, P = 0.0004 (Mann-Whitney test).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe the development of a differential fluorescence screening approach to identify L. monocytogenes genes required for optimal intracellular replication. Whereas methicillin selection-based screens allow the recovery only of mutants completely defective in intracellular growth, the utilization of a differential fluorescence screen enables the recovery of mutants exhibiting a broad range of intracellular replication defects. As proof of principle, using FACS collection of infected BMM exhibiting host cell autofluorescence levels, we isolated L. monocytogenes transposon mutants possessing severe intracellular replication defects (Fig. 1A). Since mutants with Himar1 insertion mutations within the GFP gene were expected to constitute the majority of the recovered mutants, we counterscreened 6,800 mutants recovered by FACS for GFP expression and performed automated fluorescence microscopy of infected BMM to verify the presence of GFP-expressing intracellular replication-defective mutants. A total of 12 intracellular replication-defective transposon mutants representing 7 distinct loci were identified (Table 1). The recovery of multiple independent transposon insertions within the known virulence genes prfA and hly, which are essential for L. monocytogenes pathogenesis, confirmed the ability of the differential fluorescence screening approach to isolate intracellular replication mutants. Furthermore, the subsequent observation that BMM infected with the identified Himar1 mutants resulted in substantially smaller GFPhigh subpopulations than BMM infected with the screening background strain (Fig. 2) further validated the differential fluorescence screening strategy. The fact that the majority of the post-FACS-recovered mutants were GFP negative also demonstrates the high stringency achievable by differential fluorescence screening. It is also possible that the 14-hour growth period for the Himar1 library that was used to reduce the frequency of transposon mutants with general growth defects prior to BMM infection and FACS resulted in an overrepresentation of a small number of transposon mutants with severe intracellular replication defects. This may explain the recovery of relatively few independent Himar1 insertions in the 7 identified genetic loci. As the DH-L2021 Himar1 library affords extensive genomic coverage (the library contains over 100,000 independent insertion mutants pooled from 6 separate transposition experiments) and the Himar1 transposon does not exhibit significant insertional bias in the L. monocytogenes genome (15), the lack of diversity of recovered mutants is not attributable to insufficient transposon library complexity. We hypothesize that additional differential fluorescence screens performed without prior outgrowth of the DH-L2021 library may produce a more comprehensive collection of intracellular replication-defective mutants, although an increased majority of Himar1 insertion mutants possessing general growth defects would be expected in the resultant mutant pool.

Among the identified loci contributing to L. monocytogenes intracellular replication (Table 1) menD, hepT, and pepP were chosen for further study. MenD is a dedicated menaquinone biosynthesis enzyme, while HepT is a component of the protein complex that produces heptaprenyl diphosphate, the side chain moiety that anchors menaquinone to the plasma membrane to properly localize the molecule for participation in the electron transport chain and aerobic metabolism. Stritzker and colleagues previously reported that defined L. monocytogenes aro deletion strains possess severe general and intracellular replication defects in vitro and are attenuated in vivo (16). While the aro pathway produces precursor molecules used in aromatic amino acid, folate, and menaquinone biosynthesis pathways, the authors observed that only exogenous menaquinone or growth under anaerobic conditions rescued the slow-growth phenotype of aro deletion strains, implicating menaquinone auxotrophy as the cause of the intracellular replication-defective phenotype. The isolation of menD and hepT transposon insertion mutants by the differential fluorescence screen and the observation of an aerobic growth defect in the menD mutant strain (Fig. 3A) corroborate these prior findings and provide further evidence for the importance of menaquinone and aerobic metabolism for L. monocytogenes intracellular pathogenesis. PepP is an X-prolyl aminopeptidase protein family member, a bacterial peptidase involved in protein degradation through hydrolysis of small peptides to release free amino acids for reuse. While Zemansky and colleagues have identified a pepP Himar1 insertion mutant as having a slightly hypohemolytic phenotype on blood agar plates (15), to our knowledge no link between pepP and bacterial virulence has been previously described.

We determined that a ΔmenD strain possesses a range of defects, including slow aerobic growth (Fig. 3A), complete abrogation of plaque formation in monolayers of L2 fibroblasts (Table 2), defective intracellular infection in primary BMM (Fig. 4A) and L2 fibroblasts (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), and a 5-log decrease in in vivo virulence (Fig. 5). The complete rescue of the plaquing and intracellular replication defects by the menD complementation strain, yet the failure to fully rescue aerobic growth in broth culture, suggests a possible lower requirement for menaquinone and aerobic metabolism during intracellular infection by L. monocytogenes. The additional evidence for the requirement of menaquinone for L. monocytogenes intracellular replication provides further insight into the conditions encountered by intracellular pathogens during growth in the host cell cytosol. The adoption of aerobic metabolism by L. monocytogenes in the cytosolic environment indirectly suggests that the cytosol contains sufficient oxygen levels to support aerobic growth, an intuitive though underappreciated aspect of intracellular infection by many pathogens. While the intracellular replication defect of ΔmenD strains is presumably due at least in part to a shift to less energetically favorable anaerobic metabolism necessitated by menaquinone auxotrophy, additional work is warranted to identify a possible metabolism-independent mechanism(s) for the requirement of menD or to definitively determine if downstream effects of aberrant bacterial metabolism facilitate the intracellular replication defect.

Perhaps the most interesting discovery in this study is the identification of PepP as an L. monocytogenes factor required for optimal intracellular replication and virulence in mice. The finding that a ΔpepP strain possessed no growth defect in broth culture (Fig. 3A) while exhibiting defects in plaque formation, intracellular replication, and in vivo virulence (Table 2 and Fig. 4C and 5, respectively) strongly suggests that PepP is specifically required for intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes. The transient difference in the intracellular growth rate of the ΔpepP mutant during BMM infection (Fig. 4C) suggests that PepP acts early during the infection process. Moreover, the observation that the ΔpepP mutant displays no intracellular growth defect during an 8-hour infection of L2 fibroblasts (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material) yet possesses a 22% plaquing defect suggests PepP is not required for optimal intracellular growth in L2 cells but may contribute to cell-to-cell spread. Additional work is required to elucidate the specific role(s) of PepP during intracellular infection. Potential roles of PepP may include (i) an increased need for bacterial protein turnover during intracellular growth, (ii) the degradation of host-derived small peptides to salvage amino acids for use by bacteria, (iii) the posttranslational processing of other L. monocytogenes factors necessary for intracellular infection, and/or (iv) an as-yet-unidentified mechanism.

The development of a differential fluorescence screening approach for L. monocytogenes provides a powerful new tool for the identification of bacterial mutants possessing various severities of intracellular infection defects. Shifting the FACS collection gate to a higher host cell GFP fluorescence intensity would allow the recovery of Himar1 transposon mutants bearing intermediate intracellular growth defects. Furthermore, incorporation of a second fluorescent protein into the screening background strain or cloning of the GFP gene expression cassette into the transposon would also eliminate the need for counterscreening of recovered mutants. Additionally, differential fluorescence screening of a GFP+, ActA-expressing L. monocytogenes transposon library by FACS collection of the extreme GFPhigh host cell population would allow the recovery of mutants bearing Himar1 insertions in genes required for actin-based motility of L. monocytogenes. Collectively, our studies further demonstrate that differential fluorescence/FACS screening is amenable to multiple bacterial systems and can provide novel insights into the requirements for intracellular pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dan Portnoy for the generous gift of pJZ037, Colin Hill for the generous gift of pIMK, Ken Ketman for flow cytometry instruction, Keith Ketterer for assistance in the generation of figures, the ICCB-Longwood Screening Facility, and Jimmy Regeimbal and Elizabeth Halvorsen for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI53669 from the National Institutes of Health (D.E.H.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 May 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00210-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vazquez-Boland JA, Kuhn M, Berche P, Chakraborty T, Dominguez-Bernal G, Goebel W, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Wehland J, Kreft J. 2001. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:584–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. 1989. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J. Cell Biol. 109:1597–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portnoy DA, Jacks PS, Hinrichs DJ. 1988. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Exp. Med. 167:1459–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geoffroy C, Raveneau J, Beretti J, Lecroisey A, Vazquez-Boland J, Alouf JE, Berche P. 1991. Purification and characterization of an extracellular 29-kilodalton phospholipase C from Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 59:2382–2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camilli A, Goldfine H, Portnoy DA. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes mutants lacking phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C are avirulent. J. Exp. Med. 173:751–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marquis H, Doshi V, Portnoy DA. 1995. The broad-range phospholipase C and a metalloprotease mediate listeriolysin O-independent escape of Listeria monocytogenes from a primary vacuole in human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 63:4531–4534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pizarro-Cerda J, Cossart P. 2006. Subversion of cellular functions by Listeria monocytogenes. J. Pathol. 208:215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocks C, Gouin E, Tabouret M, Berche P, Ohayon H, Cossart P. 1992. L. monocytogenes-induced actin assembly requires the actA gene product, a surface protein. Cell 68:521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberti-Segui C, Goeden KR, Higgins DE. 2007. Differential function of Listeria monocytogenes listeriolysin O and phospholipases C in vacuolar dissolution following cell-to-cell spread. Cell. Microbiol. 9:179–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camilli A, Paynton CR, Portnoy DA. 1989. Intracellular methicillin selection of Listeria monocytogenes mutants unable to replicate in a macrophage cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5522–5526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Riordan M, Moors MA, Portnoy DA. 2003. Listeria intracellular growth and virulence require host-derived lipoic acid. Science 302:462–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathman M, Jouirhi N, Allaoui A, Sansonetti P, Parsot C, Tran Van Nhieu G. 2000. The development of a FACS-based strategy for the isolation of Shigella flexneri mutants that are deficient in intercellular spread. Mol. Microbiol. 35:974–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RL, Tvinnereim AR, Jones BD, Harty JT. 2001. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes in vivo-induced genes by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Infect. Immun. 69:5016–5024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bumann D, Valdivia RH. 2007. Identification of host-induced pathogen genes by differential fluorescence induction reporter systems. Nat. Protoc. 2:770–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zemansky J, Kline BC, Woodward JJ, Leber JH, Marquis H, Portnoy DA. 2009. Development of a mariner based transposon and identification of Listeria monocytogenes determinants, including the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase PrsA2, that contribute to its hemolytic phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 191:3950–3964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stritzker J, Janda J, Schoen C, Taupp M, Pilgrim S, Gentschev I, Schreier P, Geginat G, Goebel W. 2004. Growth, virulence, and immunogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes aro mutants. Infect. Immun. 72:5622–5629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lieberman LA, Higgins DE. 2009. A small-molecule screen identifies the antipsychotic drug pimozide as an inhibitor of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:756–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen A, Higgins DE. 2005. The 5′ untranslated region-mediated enhancement of intracellular listeriolysin O production is required for Listeria monocytogenes pathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1460–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith K, Youngman P. 1992. Use of a new integrational vector to investigate compartment-specific expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIM gene. Biochimie 74:705–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins DE, Buchrieser C, Freitag NE. 2006. Genetic tools for use with Listeria monocytogenes, p 620–623 Fischetti VA, Novick RP, Ferretti JJ, Portnoy DA, Rood JI. (ed), Gram-positive pathogens, 2nd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodgson DA. 2000. Generalized transduction of serotype 1/2 and serotype 4b strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:312–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun AN, Camilli A, Portnoy DA. 1990. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect. Immun. 58:3770–3778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skoble J, Portnoy DA, Welch MD. 2000. Three regions within ActA promote Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation and Listeria monocytogenes motility. J. Cell Biol. 150:527–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leimeister-Wachter M, Haffner C, Domann E, Goebel W, Chakraborty T. 1990. Identification of a gene that positively regulates expression of listeriolysin, the major virulence factor of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:8336–8340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marquis H, Bouwer HG, Hinrichs DJ, Portnoy DA. 1993. Intracytoplasmic growth and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes auxotrophic mutants. Infect. Immun. 61:3756–3760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu YJ, Zhang YM, Grimes KD, Qi J, Lee RE, Rock CO. 2006. Acyl-phosphates initiate membrane phospholipid synthesis in Gram-positive pathogens. Mol. Cell 23:765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paoletti L, Lu YJ, Schujman GE, de Mendoza D, Rock CO. 2007. Coupling of fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 189:5816–5824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi K, Ehrlich SD, Albertini A, Amati G, Andersen KK, Arnaud M, Asai K, Ashikaga S, Aymerich S, Bessieres P, Boland F, Brignell SC, Bron S, Bunai K, Chapuis J, Christiansen LC, Danchin A, Debarbouille M, Dervyn E, Deuerling E, Devine K, Devine SK, Dreesen O, Errington J, Fillinger S, Foster SJ, Fujita Y, Galizzi A, Gardan R, Eschevins C, Fukushima T, Haga K, Harwood CR, Hecker M, Hosoya D, Hullo MF, Kakeshita H, Karamata D, Kasahara Y, Kawamura F, Koga K, Koski P, Kuwana R, Imamura D, Ishimaru M, Ishikawa S, Ishio I, Le Coq D, Masson A, Mauel C, Meima R, Mellado RP, Moir A, Moriya S, Nagakawa E, Nanamiya H, Nakai S, Nygaard P, Ogura M, et al. 2003. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:4678–4683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller CG, Green L. 1983. Degradation of proline peptides in peptidase-deficient strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 153:350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzales T, Robert-Baudouy J. 1996. Bacterial aminopeptidases: properties and functions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 18:319–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Xia Y, Cheng C, Fang C, Shan Y, Jin G, Fang W. 2011. Genome sequence of the nonpathogenic Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4a strain M7. J. Bacteriol. 193:5019–5020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson A, Chen M, Fyfe PK, Guo Z, Hunter WN. 2010. Structure and reactivity of Bacillus subtilis MenD catalyzing the first committed step in menaquinone biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 401:253–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang YW, Koyama T, Ogura K. 1997. Two cistrons of the gerC operon of Bacillus subtilis encode the two subunits of heptaprenyl diphosphate synthase. J. Bacteriol. 179:1417–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang YW, Koyama T, Marecak DM, Prestwich GD, Maki Y, Ogura K. 1998. Two subunits of heptaprenyl diphosphate synthase of Bacillus subtilis form a catalytically active complex. Biochemistry 37:13411–13420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marquis H, Goldfine H, Portnoy DA. 1997. Proteolytic pathways of activation and degradation of a bacterial phospholipase C during intracellular infection by Listeria monocytogenes. J. Cell Biol. 137:1381–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.