Abstract

Recognition of microbial infection by certain intracellular pattern recognition receptors leads to the formation of a multiprotein complex termed the inflammasome. Inflammasome assembly activates caspase-1 and leads to cleavage and secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and IL-18, which help control many bacterial pathogens. However, excessive inflammation mediated by inflammasome activation can also contribute to immunopathology. Here, we investigated whether Haemophilus ducreyi, a Gram-negative bacterium that causes the genital ulcer disease chancroid, activates inflammasomes in experimentally infected human skin and in monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM). Although H. ducreyi is predominantly extracellular during human infection, several inflammasome-related components were transcriptionally upregulated in H. ducreyi-infected skin. Infection of MDM with live, but not heat-killed, H. ducreyi induced caspase-1- and caspase-5-dependent processing and secretion of IL-1β. Blockage of H. ducreyi uptake by cytochalasin D significantly reduced the amount of secreted IL-1β. Knocking down the expression of the inflammasome components NLRP3 and ASC abolished IL-1β production. Consistent with NLRP3-dependent inflammasome activation, blocking ATP signaling, K+ efflux, cathepsin B activity, and lysosomal acidification all inhibited IL-1β secretion. However, inhibition of the production and function of reactive oxygen species did not decrease IL-1β production. Polarization of macrophages to classically activated M1 or alternatively activated M2 cells abrogated IL-1β secretion elicited by H. ducreyi. Our study data indicate that H. ducreyi induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation via multiple mechanisms and suggest that the heterogeneity of macrophages within human lesions may modulate inflammasome activation during human infection.

INTRODUCTION

The Gram-negative bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi is the causative agent of the sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease (GUD) chancroid. Similar to other GUDs, chancroid facilitates the acquisition and transmission of HIV-1 by disruption of epithelial barriers, recruitment of HIV-1 target cells to infected sites, and immune activation of HIV-1 replication (1). Chancroid is endemic in resource-poor regions of Africa and Asia, but its prevalence is unknown due to the use of syndrome management for GUD. In the South Pacific islands, H. ducreyi also causes a chronic limb ulceration syndrome that does not appear to be sexually transmitted (2–4).

H. ducreyi is a strict human pathogen. To study the human immune response to H. ducreyi, we developed a human challenge model in which the skin of the upper arm is inoculated with H. ducreyi (5–7). Papules form within 24 h of inoculation and either spontaneously resolve or evolve into pustules. Experimental infection primarily elicits a local immune response, which includes a cutaneous infiltration of neutrophils, a mixture of M1- and M2-polarized macrophages, myeloid dendritic cells (DC), NK cells, effector/memory CD4 and CD8 T cells, and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (7–11). Despite the recruitment of various innate and adaptive immune cells, in most infected persons H. ducreyi persists extracellularly and causes abscess formation.

When challenged twice with H. ducreyi, volunteers tend to either resolve infection twice (RR group) or form pustules twice (PP group) (12). Microarray analysis of infected skin obtained from RR and PP subjects 48 h after a third challenge shows that compared to persons in the RR group, members of the PP group exhibit a hyperinflammatory response, expressing higher levels of transcripts for several genes encoding proinflammatory molecules, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) (12), a potent and pleiotropic inflammatory mediator (13).

The secretion of biologically active IL-1β during infection is a tightly regulated process that requires two distinct signals. Engagement of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) leads to the generation of the first signal, which induces the production of IL-1β mRNA and the IL-1β precursor pro-IL-1β. Activation of a subset of intracellular PRRs by microbial PAMPs as well as DAMPs (danger-associated molecular patterns) released from infected/damaged tissues provides the second signal, which promotes the assembly of a multiprotein complex called the inflammasome (14–17). Inflammasome activation leads to oligomerization and proteolytic cleavage of pro-caspase-1 to enzymatically active caspase-1, a member of the inflammatory caspases (18). Activated caspase-1 cleaves pro-IL-1β to mature and bioactive IL-1β, which is then released from activated cells.

At least four types of inflammasomes have been identified, each defined by a particular intracellular PRR sensor: three of them contain a specific nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR), and the fourth consists of the HIN200 family member, AIM2 (14–16, 19). The PRR sensors recruit and activate pro-caspase-1 either directly or through an adaptor protein, the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC). The human NLRP1 inflammasome is activated by bacterial muramyl dipeptide (MDP) derived from cell wall peptidoglycans (20). The NLRP3 inflammasome is assembled in response to numerous chemically and structurally unrelated PAMPs and DAMPs, such as intracellular MDP, bacterial pore-forming toxins, bacterial mRNA and DNA, and extracellular ATP (14, 16, 19, 21, 22). The NLRC4 inflammasome is activated by the binding of the NLR sensor NAIP to bacterial flagellin or a conserved type III secretion system (T3SS) rod protein motif found in several Gram-negative bacteria (23–25). The AIM2 inflammasome senses bacterial and viral DNA in the cytosol (14, 21, 26).

In both experimental and natural infections, H. ducreyi is surrounded by neutrophils and macrophages and predominantly evades phagocytic uptake (27, 28). However, subpopulations of H. ducreyi may be phagocytosed during human infection and initiate inflammasome activation. H. ducreyi does not make flagellin or a T3SS but does produce a pore-forming toxin, hemolysin. H. ducreyi mRNA and MDP could gain entrance to the cytosol through cytoplasmic membrane pores produced by hemolysin and induce the NLRP3 and NLRP1 inflammasomes. Alternatively, bacterial components from ingested organisms could leak from phagolysosomes into the cytosol and induce inflammasome activation (29, 30).

Here, we examined mRNA expression of inflammasome-associated genes in H. ducreyi-infected skin and inflammasome activation in H. ducreyi-infected monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM). We show that H. ducreyi infection enhanced the expression of several inflammasome-related transcripts at infected sites. We demonstrate that H. ducreyi infection of MDM induced IL-1β secretion, which required the enzymatic activity of caspase-1 and caspase-5, bacterial viability, and phagocytic uptake. We also show that the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome played a critical role in H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β production. Several activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome, including ATP, K+ efflux, cathepsin B activation, and lysosomal acidification, were critically involved. Finally, we demonstrate that H. ducreyi induced inflammasome activation in nonpolarized macrophages but not in polarized macrophages, which has implications for inflammasome activation at sites of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The H. ducreyi strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were grown on chocolate agar plates and in gonococcal (GC) medium broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml hemin, 1% IsoVitaleX, and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) as described previously (31). H. ducreyi cells were grown to mid-log phase and washed twice with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) before being cocultured with macrophages. To obtain heat-killed H. ducreyi, washed bacteria were suspended in HBSS and incubated at 65°C for 1 h.

Table 1.

H. ducreyi strains used in this study

Generation and infection of MDM derived from blood of uninfected donors.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque Plus gradient centrifugation from leukopacks purchased from the Central Indiana Regional Blood Center from 31 anonymous donors. PBMC were prepared from the peripheral blood of 10 healthy adult volunteers. Informed consent was obtained from the volunteers, in accordance with the human experimentation guidelines of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University.

CD14+ monocytes were purified from PBMC by positive selection using magnetic CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). To generate MDM, CD14+ monocytes were cultured in 24-well plates (106/well) in X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 1% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Invitrogen) for 5 to 6 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Half of the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium on day 3 and day 5. To infect MDM, bacteria were centrifuged onto wells containing MDM in X-VIVO 15 medium containing 5% to 10% FBS at an approximate multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1. After 90 min of incubation at 35°C, cells were incubated at 37°C for an additional 3.5 to 4.5 h or for various periods of time in time course studies.

To dissect the mechanisms of inflammasome activation induced by H. ducreyi, MDM were incubated with various pharmacological inhibitors for 1 h at 37°C prior to infection. To block the enzymatic activities of caspase-1 and caspase-5, MDM were treated with 40 μM Z-YVAD-FMK (BioVision) and 40 μM Z-WEHD-FMK (BioVision), respectively. To inhibit H. ducreyi uptake, MDM were treated with 10 μM cytochalasin D (Calbiochem). To block the contributions of ATP, K+ efflux, cathepsin B, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and lysosomal acidification to inflammasome activation, MDM were pretreated with various concentrations of oxidized ATP (Sigma-Aldrich), KCl, CA-074-Me (Calbiochem), apocynin (Sigma-Aldrich) or N-acetyl-l-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), and chloroquine phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DSMO), which was used to dissolve cytochalasin D, Z-YVAD-FMK, Z-WEHD-FMK, CA-074-Me, and apocynin, served as a vehicle control for these experiments.

Polarization of MDM.

MDM were polarized into M1 cells by treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O26:B6 (100 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (10 ng/ml), M2a cells with IL-4 (10 ng/ml), and M2c cells with IL-10 (10 ng/ml) for 2 days. Nonpolarized and polarized MDM were washed once before bacterial infection.

THP-1 cell lines.

The THP-1 human monocytic leukemia cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The construction of THP-1 cell lines stably expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting NLRP3 and ASC, control shRNA (scrambled sequence with base content equal to shASC), and the empty retroviral vector has been previously described (32, 33), and the cells were kindly provided by Joseph A. Duncan of the University of North Carolina. THP-1 cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 10% FBS and infected at an MOI of 3:1 for 6 h.

H. ducreyi uptake and intracellular survival assays.

To examine the effect of cytochalasin D on H. ducreyi uptake, MDM were pretreated with medium, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), or 10 μM cytochalasin D for 1 h and infected with H. ducreyi at an MOI of 10:1. The plates were centrifuged at 180 × g for 5 min to synchronize infection and incubated for 30 min at 35°C. The cocultures were then treated with 100 μg/ml of gentamicin for 30 min at 35°C to kill extracellular bacteria, washed three times with HBSS, lysed with 0.2% saponin for 10 min at room temperature, and quantitatively cultured. The percentage of internalized bacteria was calculated as the ratio of gentamicin-protected geometric mean CFU to the initial geometric mean CFU added per well × 100.

To determine the intracellular survival rates of H. ducreyi, MDM were infected with H. ducreyi at an MOI of 10:1 for 30 min and treated with gentamicin (100 μg/ml) for 30 min at 35°C in 5% CO2. After three washes with HBSS, MDM were lysed with 0.2% saponin and quantitatively cultured. The resulting CFU represented the amount of H. ducreyi ingested at 0 h. To determine the survival of the ingested bacteria, additional cocultures were incubated in antibiotic-free medium for 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 and quantitatively cultured. The percentage of survival of intracellular bacteria was calculated as the ratio of CFU recovered at different time points to CFU ingested at 0 h × 100.

ELISA of cytokines in cell culture supernatants.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were used to measure the levels of IL-1β (eBioscience), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; BD Biosciences), and IL-10 (BD Biosciences) in the culture supernatants. Purified mouse anti-human IL-18 antibody (clone 152-2H; R&D Systems) and biotinylated rat anti-human IL-18 antibody (clone 159-12B; R&D Systems) were used to measure secreted IL-18.

Western blot analysis.

MDM cell pellets were harvested, lysed in Laemmli buffer, sonicated, and boiled. Cell lysates were electrophoresed in 15% or 10% acrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. To detect protein expression of pro-IL-1β, mature IL-1β, and IL-18, the membranes were probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies to human IL-1β (clone 8516; R&D Systems), rabbit polyclonal antibodies to human IL-1β (catalog no. 2022; Cell Signaling Technology), and rabbit polyclonal antibodies to human IL-18 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), respectively. To detect protein expression of inflammasome components in nonpolarized and polarized MDM, the membranes were probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies to human NLRP3 (clone Cryo-2; AdipoGen) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies to human ASC, caspase-1, and caspase-5 (Cell Signaling Technology). As a loading control, the membranes were stripped and reprobed with mouse monoclonal antibody 6C5 (Abcam) against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

To detect secreted IL-1β, culture supernatants were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-human IL-1β monoclonal antibodies (clone CMR56; eBioscience) and probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies to human IL-1β (catalog no. 2022; Cell Signaling Technology). In some experiments, culture supernatants were loaded onto the gel without immunoprecipitation.

Detection of enzymatically active caspase-1 by flow cytometry.

A Green FLICA caspase-1 assay kit (ImmunoChemistry Technologies) was used to detect caspase-1 enzymatic activity according to the manufacturer's instructions with some minor modifications. Two hours after an experiment was initiated, the fluorescently labeled inhibitor probe of caspase-1 FAM-YVAD-FMK (FLICA-1) was added to wells containing uninfected or infected cells. The cells were cultured for 3 more hours, washed once, and incubated in fresh medium for another hour. MDM were then collected and subjected to flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of FLICA-1-positive MDM.

Statistical analysis.

For experiments with more than 2 groups, a mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the donor as a random effect followed by Dunnett's or Tukey's procedure was used for comparisons between one group and all other groups or for pairwise multiple comparisons, respectively. For experiments with 2 groups, we used paired t tests. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Transcriptional activation of inflammasome-related genes in H. ducreyi-infected human skin.

Inflammasome function is tightly controlled through a two-step process, in which signal 1 induces gene expression of inflammasome components and cytokine precursors and signal 2 induces inflammasome assembly and cleavage of key proteins (14, 34). To evaluate whether H. ducreyi infection induces inflammasome activation, we reexamined previously published microarray data generated from H. ducreyi-infected skin biopsy specimens. The biopsy specimens were obtained 48 h after a third infection of volunteers who had resolved infection twice or formed pustules twice (12). In both groups, we found that, relative to sham-infected skin, H. ducreyi-infected skin showed enhanced expression of genes encoding several inflammasome-associated sensors of microbial PAMPs (AIM2, NLRC4/NAIP, and NLRP3), three inflammatory caspases (caspase-1, caspase-4, and caspase-5), and IL-1β, whereas the NLRP1 sensor was downregulated (Table 2). Due to the small sample size, we were unable to statistically compare the levels of differential regulation between the two groups of subjects. Nevertheless, the data suggest that inflammasome activation is involved in the cutaneous immune response to H. ducreyi.

Table 2.

Transcriptional activation of inflammasome-associated genes in H. ducreyi-infected human skin

| Gene designation | Protein | Fold change in transcript levela |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | PP | ||

| AIM2 | Absent in melanoma 2 | 13.8 | 8.3 |

| NAIP | NLR containing a baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis domain-1 | 3.8 | 6.4 |

| NLRC4 | NLR family, CARD domain-containing protein 4 | 3.8 | 2.9 |

| NLRP1 | NLR family, pyrin domain-containing protein 1 | −3.0 | −2.1 |

| NLRP3 | NLR family, pyrin domain-containing protein 3 | 5.2 | 5.3 |

| CASP1 | Caspase-1 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| CSAP4 | Caspase-4 | 4.6 | 4.2 |

| CASP5 | Caspase-5 | 20.1 | 2.7 |

| IL1B | IL-1β | 11.0 | 21.2 |

Values represent fold changes in transcript levels between infected and sham-infected skin tissue samples obtained 48 h after a third H. ducreyi infection from volunteers who had previously been challenged twice and either resolved all inoculated sites twice (RR) or formed pustules twice (PP).

H. ducreyi induces IL-1β processing and secretion in MDM.

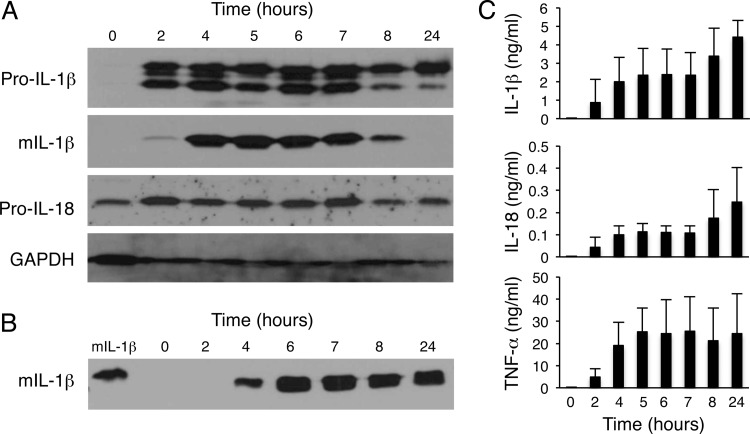

Although the cellular source of the transcripts of inflammasome-associated genes in H. ducreyi-infected skin was not defined, macrophages are a major producer of IL-1β due to inflammasome activation under a myriad of conditions. In H. ducreyi-infected lesions, there is a rapid and abundant infiltration of macrophages, which form a collar underneath the neutrophil-containing abscess (27, 35, 36). To investigate whether and how H. ducreyi activates inflammasomes in human macrophages, we used in vitro-differentiated MDM as surrogates for lesional macrophages. Dose-ranging experiments using MOIs from 1:1 to 100:1 showed that MDM infected with H. ducreyi at an MOI of 10:1 had the highest level of IL-1β expression (data not shown). Thus, all subsequent experiments were done at an MOI of 10:1. In a time course study, MDM were infected with live H. ducreyi for various periods of time; cell lysates and culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for the production of the inflammasome-dependent cytokine IL-1β and the inflammasome-independent cytokine TNF-α. Uninfected MDM did not express detectable levels of pro-IL-1β, mature IL-1β, or TNF-α (Fig. 1). Exposure to H. ducreyi stimulated pro-IL-1β production by 2 h and IL-1β cleavage by 4 h (Fig. 1A). Secretion of mature IL-1β and TNF-α was evident 4 to 24 h after infection (Fig. 1B and C). We also examined whether H. ducreyi induced secretion of IL-18, another inflammasome-dependent cytokine. As shown in Fig. 1A, uninfected MDM expressed pro-IL-18; H. ducreyi infection enhanced pro-IL-18 production. Although we were unable to detect mature IL-18 by Western blotting, IL-18 secretion was detected by ELISA within 2 h of infection and peaked at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

Time course of H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β processing and secretion in MDM. Macrophages were infected with live H. ducreyi for the indicated times (hours) at an MOI of 10:1. (A) Whole-cell lysates were probed with antibodies recognizing unprocessed IL-1β (pro-IL-1β), processed mature IL-1β (mIL-1β), IL-18, or GAPDH. (B) Cell culture supernatants were immunoprecipitated and probed with antibodies against IL-1β; a mature IL-1β standard is loaded in the first lane. (C) Culture supernatants were assessed for secreted IL-1β, IL-18, and TNF-α by ELISA. The bars represent the means + standard deviations (SD) of the results of assays performed with samples from 4 donors.

Inflammasome activation by bacterial pathogens often causes pyroptosis/pyronecrosis, a specific form of cell death that results in cell lysis (37, 38). Thus, we performed lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assays to monitor H. ducreyi-induced cell lysis. Compared to uninfected MDM, H. ducreyi did not induce LDH release from macrophages infected for up to 24 h (data not shown). Trypan blue staining of MDM also showed that most of the cells were viable after 24 h of infection. Thus, H. ducreyi infection of MDM for up to 24 h led to production of the inflammasome-dependent cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 but did not induce appreciable pyroptosis/pyronecrosis.

H. ducreyi-induced caspase-1 and caspase-5 activation is required for IL-1β secretion.

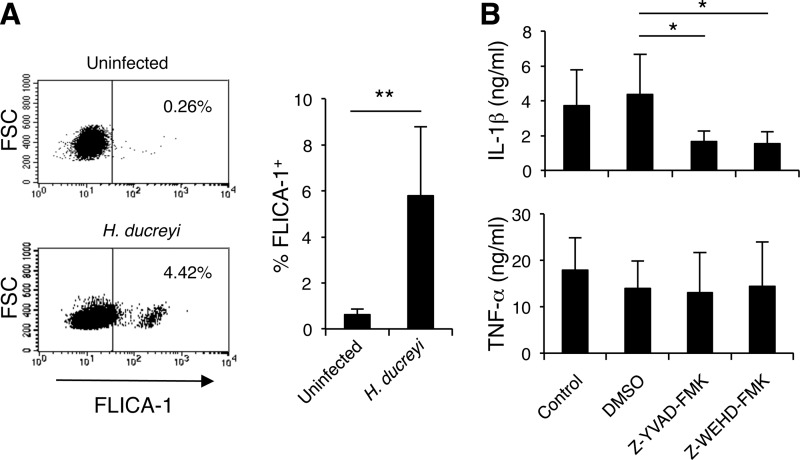

IL-1β processing and secretion are usually mediated by caspase-1 and can be enhanced by caspase-5 under certain circumstances (17, 39). To determine whether H. ducreyi infection of MDM activated caspase-1, we utilized the cell-permeative, fluorescently labeled caspase-1 inhibitor FLICA-1. The probe irreversibly binds to activated caspase-1, and the fluorescent signal is a direct measure of caspase-1 enzyme activity. Compared to uninfected MDM, a small but significantly higher percentage of H. ducreyi-infected MDM were labeled by FLICA-1 (Fig. 2A). To examine the functional role of caspase-1 and caspase-5 in IL-1β secretion, we used pharmacological inhibitors of caspase-1 (Z-YVAD-FMK) and caspase-5 (Z-WHED-FMK) to block enzymatic activity of these two caspases. Compared to the vehicle control DMSO, both inhibitors significantly reduced production of IL-1β but not of TNF-α (Fig. 2B). These results confirmed that IL-1β maturation was driven by inflammasome and that H. ducreyi-promoted activation of caspase-1 and caspase-5 is critically involved in IL-1β production.

Fig 2.

H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β secretion requires caspase-1 and caspase-5 activation. (A) Detection of active caspase-1. The fluorescently labeled probe of caspase-1 FAM-YVAD-FMK (FLICA-1) was incubated with uninfected MDM (top panel) or H. ducreyi-infected MDM (bottom panel). After washing, the fluorescent intensity retained by the MDM was determined by flow cytometry. The numbers in the dot plots represent the percentages of cells that were stained by FLICA-1. Summary data of FLICA-1-positive MDM were derived from 6 donors (right panel). The bars represent the means + SD of the percentages of cells labeled with FLICA-1. **, P ≤ 0.01 (infected versus uninfected MDM). FSC, forward scatter. (B) Effect of caspase-1 (Z-YZAD-FMK) and caspase-5 (Z-WEHD-FMK) inhibitors on IL-1β and TNF-α secretion. MDM were infected with H. ducreyi alone (control) or in the presence of Z-YZAD-FMK, Z-WEHD-FMK, or the vehicle control DMSO. Culture supernatants were measured for secreted IL-1β and TNF-α by ELISA. The bars represent the means + SD of the results of assays performed with cells from 5 donors. *, P ≤ 0.05 (DMSO versus other groups).

H. ducreyi viability and uptake are important for IL-1β secretion.

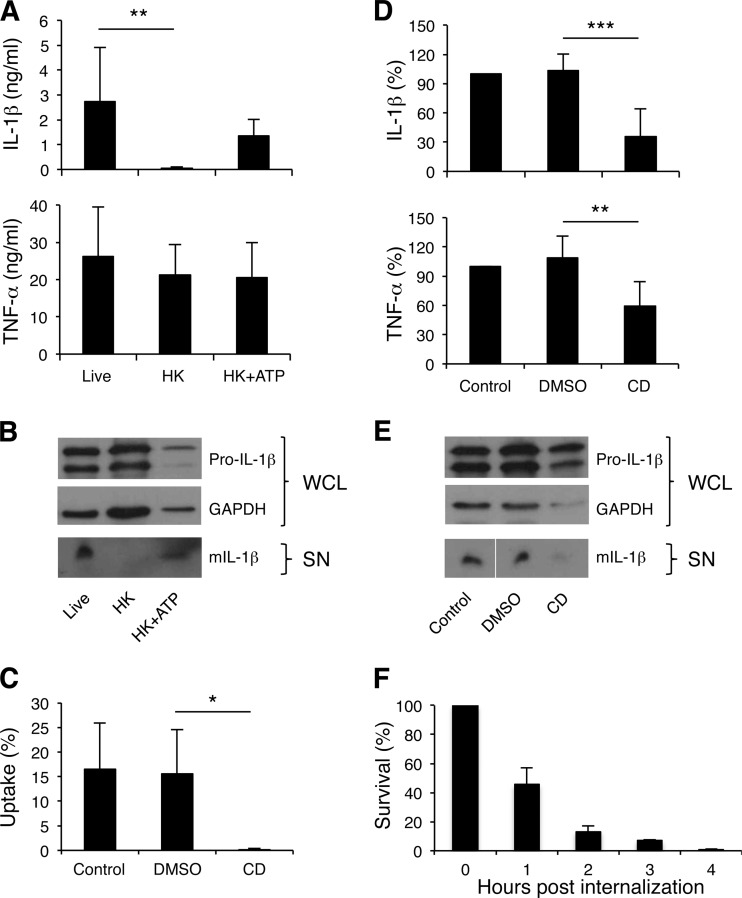

Dead bacteria are usually unable to activate inflammasomes (29, 40, 41). To determine whether bacterial viability is required for H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome activation, MDM were treated with both live and heat-killed bacteria. While heat inactivation of H. ducreyi did not compromise TNF-α secretion, heat-killed H. ducreyi induced slightly less pro-IL-1β production but little or no IL-1β secretion (Fig. 3A and B). The classic inflammasome activator ATP induces caspase-1 activation, leading to processing of pro-IL-1β and secretion of mature IL-1β. As expected, adding ATP to MDM treated with heat-killed H. ducreyi partially restored IL-1β secretion (Fig. 3A).

Fig 3.

H. ducreyi viability and uptake are required for optimal IL-1β secretion. (A and B) MDM were treated with live or heat-killed (HK) bacteria at an MOI of 10:1 or 30:1, respectively; for the HK+ATP group, 3 mM ATP was added for the last 30 min of incubation. (C to E) MDM were infected with H. ducreyi alone (control) or in the presence of 10 μM cytochalasin D (CD) or the vehicle control DMSO. (A and D) ELISA of IL-1β and TNF-α in cell culture supernatants. The cytokine levels presented in panel D were normalized to those of MDM infected with H. ducreyi alone, whose value was set at 100%. The bars represent the means + SD of the results of assays performed with cells from 8 donors (A) and 9 donors (D). **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (live versus HK and HK+ATP; cytochalasin D versus DMSO). (B and E) Western blot analysis of IL-1β. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) were probed with antibodies recognizing unprocessed IL-1β (Pro-IL-1β) or GAPDH. Cell culture supernatants (SN) were probed with antibodies against mature IL-1β. The bottom blot in panel E is shown as a composite image. The blots are representative of experiments done using cells from 3 donors. (C) Cytochalasin D inhibition of H. ducreyi uptake. MDM pretreated with medium (control), DMSO, or cytochalasin D were infected with H. ducreyi for 30 min followed by 30 min of treatment with gentamicin. Bacterial uptake was calculated as the percentage of gentamicin-protected CFU versus the inoculum. The bars represent the means + SD of the results of assays performed with cells from 4 donors. (F) Intracellular survival of H. ducreyi in MDM. Macrophages were infected with H. ducreyi for 30 min, treated with gentamicin for 30 min, washed, and either immediately cultured or incubated in antibiotic-free medium for various periods of time prior to culture. Percent bacterial survival was calculated as the ratio of the CFU recovered after incubation to the CFU recovered immediately after gentamicin treatment. Data were generated with cells from 4 donors.

To examine the role of bacterial phagocytosis in inflammasome activation, cytochalasin D, an actin polymerization inhibitor, was used to block H. ducreyi uptake by MDM. As determined by gentamicin protection assays, approximately 15% of viable H. ducreyi bacteria were ingested by MDM; cytochalasin D almost completely abolished H. ducreyi uptake (Fig. 3C). Treatment with the inhibitor significantly reduced the amount of secreted IL-1β (Fig. 3D). Cytochalasin D also significantly reduced the production of TNF-α (Fig. 3D) but did not appear to affect pro-IL-1β expression (Fig. 3E). Together, these results suggested that H. ducreyi viability, heat-labile bacterial factors, and phagocytosis are required for optimal IL-1β production.

During human infection, H. ducreyi colocalizes with macrophages and neutrophils but is not found within the phagocytes (27, 28). To investigate the fate of internalized H. ducreyi in MDM, we determined the survival rate of bacteria that had been ingested prior to gentamicin treatment. Less than 50%, 20%, 10%, and 1% of the intracellular bacteria survived at 1, 2, 3, and 4 h postingestion, respectively (Fig. 3F). Thus, the data suggest that intracellular H. ducreyi bacteria are rapidly killed and that intracellular survival or replication is not critical in H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome activation.

Role of H. ducreyi CDT and hemolysin in IL-1β secretion.

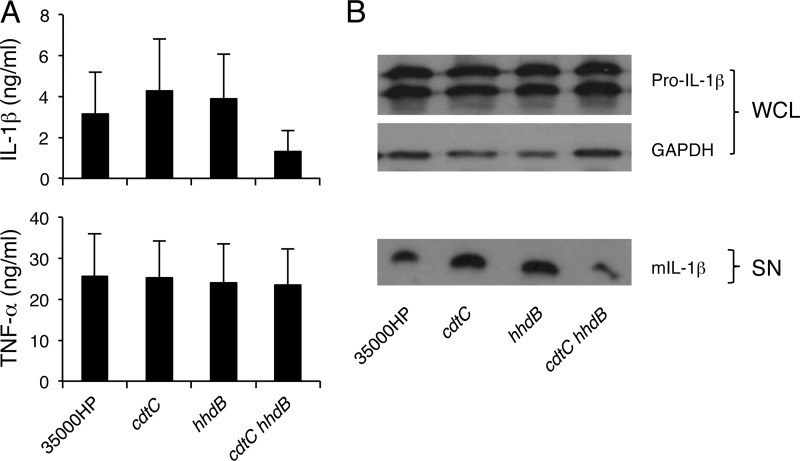

In an attempt to identify the heat-labile H. ducreyi components that induce IL-1β secretion, a cdtC mutant and a hhdB mutant, which do not produce the heat-labile proteins cytolethal extending toxin (CDT) and hemolysin, respectively, were used to infect MDM. Relative to wild-type 35000HP, both mutant strains were fully capable of promoting IL-1β secretion (Fig. 4A). A cdtC hhdB double mutant induced 48% ± 22% less mature IL-1β than the parent strain. However, this difference did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.21), likely due to donor-to-donor variations in IL-1β production (Fig. 4A). All three mutants were as efficient as the wild-type strain in inducing the production of TNF-α and pro-IL-1β (Fig. 4). Therefore, neither hemolysin nor CDT was essential for H. ducreyi-induced secretion of IL-1β or TNF-α.

Fig 4.

Inflammasome activation by H. ducreyi and its isogenic cdtC, hhdB, and cdtC hhdB mutants. (A) ELISA of IL-1β and TNF-α released by MDM that were infected with 35000HP or the mutants. The bars represent the means + SD of the results of assays performed with cells from 8 donors. (B) Immunoblot analysis of IL-1β. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) of MDM infected with the parent and the mutant strains were probed with antibodies recognizing unprocessed IL-1β (Pro-IL-1β) or GAPDH. Culture supernatants (SN) were probed with anti-mature IL-1β antibodies. The blots are representative of experiments done using samples from 3 donors.

NLRP3 and ASC mediate H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome activation.

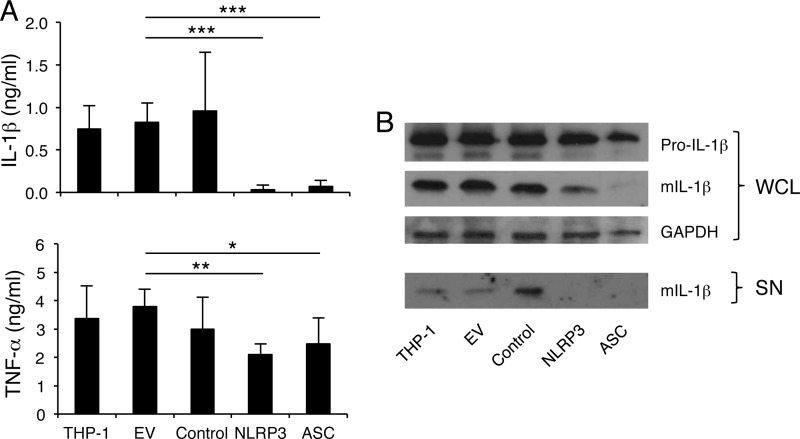

Bacterial pathogens induce the assembly of several types of inflammasomes (22, 34, 42–44). The NLRP3 inflammasome is the most versatile type, sensing diverse microbial components as well as danger signals associated with tissue damage, and plays a crucial role in response to different bacterial infections (45). To determine whether NLRP3 and the associated adaptor protein ASC were critical for H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome formation, we utilized THP-1 cell lines that express reduced levels of NLRP3 and ASC proteins (32, 33). THP-1 cells and their stably transduced derivatives carrying an empty retroviral vector or vectors expressing control, NLRP3, or ASC shRNA were infected with H. ducreyi. As shown in Fig. 5A, THP-1 cells secreted IL-1β and TNF-α in response to H. ducreyi infection. As expected, THP-1 cells lines transduced with the empty vector were not different from the parental THP-1 cells or the cell lines transduced with a control shRNA in IL-1β and TNF-α production. However, knocking down either NLRP3 or ASC almost completely abolished the secretion and processing of IL-1β in response to H. ducreyi (Fig. 5). The production of TNF-α was slightly but significantly reduced by the NLRP3 and the ASC knockdowns (Fig. 5A). Pro-IL-1β was similarly expressed in the different THP-1 cell lines (Fig. 5B). Since THP-1 cells exhibit a monocytic phenotype, we also differentiated THP-1 cells into macrophage-like cells with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) before infection. Similar results were obtained using PMA-treated cells as the undifferentiated THP-1 cells (data not shown). Thus, NLRP3 together with the adaptor protein ASC played a major role in sensing H. ducreyi infection to induce IL-1β maturation and secretion.

Fig 5.

NALP3 and ASC are essential for H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome activation. The human monocytic THP-1 cell line and THP-1 cells stably transduced with an empty retroviral vector (EV) or a vector expressing control shRNA, NLRP3 shRNA, or ASC shRNA were infected with H. ducreyi. (A) ELISA of secreted IL-1β and TNF-α. The bars represent the means + SD of values obtained from 8 experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (EV group versus the other groups). (B) Immunoblot analysis of IL-1β. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) were probed with antibodies recognizing unprocessed IL-1β (Pro-IL-1β), mature IL-1β (mIL-1β), or GAPDH. Culture supernatants (SN) were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with anti-IL-1β antibodies. The blots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Mechanisms of inflammasome activation by H. ducreyi.

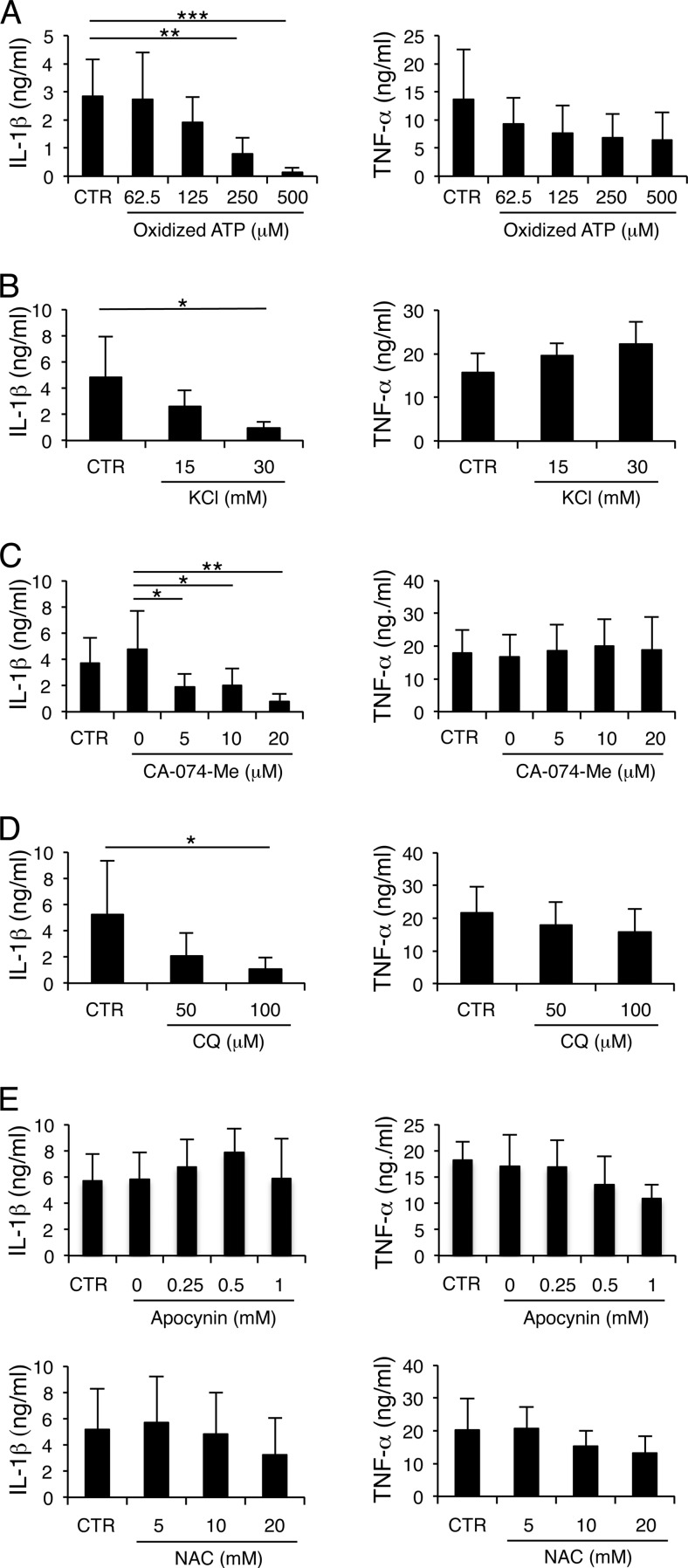

Many bacteria activate the NLRP3 inflammasome through potassium (K+) efflux induced by pore-forming toxins (46). Extracellular ATP released from infected cells is another potent inducer of the NLRP3 inflammasome (47). ATP binds to the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor (P2X7R), leading to K+ efflux and the release of cathepsins from lysosomes (48, 49). Cathepsin B released into the cytosol is associated with NLRP3 inflammasome activation (50). NLRP3 can also be activated by ROS generation (51) or lysosomal acidification (52–54). To test the role of endogenously produced ATP, K+ efflux, cathepsin B, ROS, and lysosomal acidification in H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β maturation, specific inhibitors were used to block their activity. The presence of the ATP antagonist, oxidized ATP, high concentrations of extracellular K+, the inhibitor of cathepsin B, CA-074-Me, and raising cellular pH with chloroquine phosphate or NH4Cl all abrogated production of IL-1β, but not TNF-α, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A to D). However, neither an inhibitor of ROS generation, apocynin, nor the ROS scavenger, NAC, significantly impacted IL-1β or TNF-α production (Fig. 6E). Thus, except for ROS generation, most of the cellular activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome were important for H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome activation.

Fig 6.

H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β secretion requires ATP signaling, K+ efflux, cathepsin B activation, and lysosomal acidification but not ROS generation. MDM were infected with H. ducreyi in the absence (CTR) or presence of oxidized ATP (A), KCl (B), CA-074-Me or the vehicle control DMSO (0) (C), chloroquine phosphate (CQ) (D), or apocynin or the vehicle control DMSO (0) and N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) (E) at the indicated concentrations. Cell culture supernatants were analyzed for secreted IL-1β and TNF-α by ELISA. The bars represent the means + SD of the results of assays performed with cells from 4 to 5 donors. The untreated group was compared with all other groups in panels A, B, and D and the bottom panels of E; DMSO results were compared with all other groups as indicated in panel C and the top row in panel E. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

Macrophage polarization of MDM dampens IL-1β production.

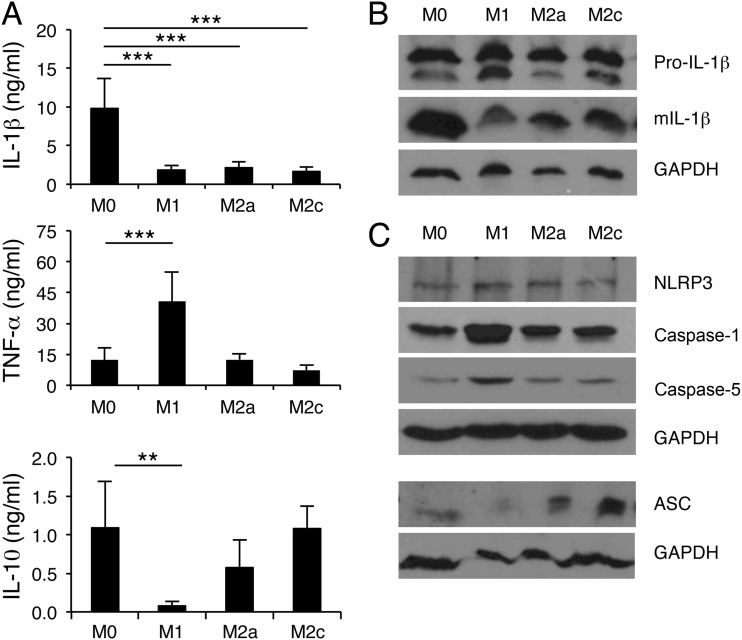

Macrophages are a heterogeneous population of cells. During bacterial infection, macrophages can be polarized to classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) macrophages in response to microenvironmental signals. Polarized macrophages express distinct phenotypes and have specialized functions in infection. Recently, we reported that macrophages at H. ducreyi-infected sites exhibit a mixed M1 and M2 activation phenotype and that M2c cells have a higher phagocytic activity against H. ducreyi than M1 cells or nonpolarized macrophages (11). Therefore, we examined the effect of M1 and M2 polarization on H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome activation. MDM were polarized to M1, M2a, and M2c cells with IFN-γ/LPS, IL-4, and IL-10, respectively. The MDM were then infected with H. ducreyi, and the production of IL-1β and TNF-α was determined. Compared to nonpolarized MDM, M1, M2a, and M2c cells all had significant reductions in IL-1β secretion (Fig. 7A), as well as reduced IL-1β processing (Fig. 7B). However, macrophage polarization had no effect on pro-IL-1β production (Fig. 7B). Except for inconsistent downregulation of ASC in M1 macrophages, polarized macrophages did not downregulate expression of the inflammasome proteins critical for H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β processing (Fig. 7C).

Fig 7.

Macrophage polarization suppresses inflammasome activation by H. ducreyi. (A) ELISA of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-10 in culture supernatants of H. ducreyi-infected nonpolarized (M0) and polarized (M1, M2a, or M2c) MDM. The bars represent the means + SD of the results of assays performed with cells from 6 donors. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (nonpolarized MDM versus polarized MDM). (B) Immunoblot analysis of IL-1β. Whole-cell lysates of H. ducreyi-infected nonpolarized and polarized MDM were probed with antibodies recognizing unprocessed IL-1β (Pro-IL-1β), mature IL-1β (mIL-1β), or GAPDH. The blots are representative of experiments done using cells from 4 donors. (C) Immunoblot analysis of the inflammasome proteins that are critical for H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β production. Whole-cell lysates of nonpolarized and polarized MDM were probed with antibodies recognizing NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, caspase-5, or GAPDH. The blots are representative of experiments done using cells from 3 donors.

Macrophage polarization did not suppress TNF-α production (Fig. 7A), but M1 skewing significantly enhanced the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 (Fig. 7A and data not shown). Compared to infected nonpolarized cells, infected M1 cells produced significantly less IL-10; neither M2a nor M2c polarization affected IL-10 expression (Fig. 7A). We conclude that macrophage heterogeneity modulates H. ducreyi-induced production of both inflammasome-dependent and inflammasome-independent cytokines. By an unknown mechanism, M1/M2 polarization suppresses the processing and release of the inflammasome-dependent cytokine IL-1β.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that H. ducreyi infection enhanced transcription of several genes encoding inflammasome-related proteins in infected human skin, indicating that inflammasome activation likely is an integral part of the innate immune response to H. ducreyi. Samples from infected subjects contained upregulated transcripts for the inflammasome sensors AIM2, NLRC4/NAIP, and NLRP3, the inflammatory caspases caspase-1, caspase-4, and caspase-5, and the inflammasome-dependent cytokine IL-1β. The enhanced accumulation of inflammasome-related mRNA is likely due to infiltration of immune cells to H. ducreyi-infected sites as well as transcriptional upregulation of inflammasome-associated genes. Consistent with the later point, stimulation of monocytes/macrophages with microbial components or proinflammatory cytokines upregulates the expression of pro-IL-1β as well as of many other inflammasome-associated genes such as AIM-2 (55), NLRP3 (50, 56–58), caspase-1 (59), and caspase-5 (60).

Microbial pathogens induce inflammasome activation in several types of innate immune cells, including DC, monocytes, and macrophages. Here, we focused on macrophages and showed that H. ducreyi infection of MDM in vitro induced caspase-1- and caspase-5-dependent secretion of IL-1β. Only live, but not heat-killed, H. ducreyi induced IL-1β processing and maturation, suggesting that either heat-labile bacterial factors or bacterial viability provides the second signal required for inflammasome activation. However, a H. ducreyi mutant lacking the production of two known heat-labile toxins, hemolysin and CDT, was not significantly impaired in its ability to induce IL-1β secretion. Bacterial mRNA, which is heat sensitive, signifies bacterial viability and promotes NLRP3 inflammasome assembly (29). Whether H. ducreyi mRNA serves as a heat-labile activator of inflammasomes requires further study. In addition to bacterial viability, phagocytosis of H. ducreyi by MDM was required for the optimal production of mature IL-1β. MDM uptake of nonopsonized or opsonized H. ducreyi is mainly mediated by scavenger receptors (11); approximately 10% to 15% of viable H. ducreyi cells are ingested by MDM (Fig. 3C) (11). Gentamicin protection assays showed that the ingested H. ducreyi cells were rapidly killed by MDM. Using confocal microscopy, we attempted to localize the ingested bacteria over the same time course; however, these experiments were unsuccessful due to the paucity of intracellular H. ducreyi, suggesting that the internalized bacteria were quickly degraded, likely within the phagolysosome. These results are consistent with the observation that H. ducreyi is predominantly extracellular during human infection (27, 28). Currently, how phagocytosis contributes to H. ducreyi-induced inflammasome activation is unclear. Phagocytosis of H. ducreyi by MDM might be required to deliver inflammasome-activating bacterial components, such as MDP and mRNA, to the cytosol or to activate signaling pathways that enhance generation of intermediate cellular activators of inflammasomes.

Microbial infection often activates multiple types of inflammasomes, which may play redundant or additive roles in host defense (34, 42–44, 61–65). Using THP-1 cell lines with stable knockdowns of NLRP3 and ASC, we demonstrated that the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome was responsible for H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β production. It is conceivable that other types of inflammasomes are also activated by H. ducreyi infection and synergize with the NLRP3 inflammasome. Consistent with this notion, we showed that caspase-5 also played a critical role in IL-1β processing. Although the mechanism of caspase-5-mediated inflammasome activation is not well characterized, caspase-5 is known to act upstream of caspase-1 in the assembly of the NLRP1 inflammasome (17). Phagocytosis and phagolysosome acidification, both critical for optimal secretion of IL-1β by H. ducreyi-infected MDM, might play a role in delivering MDP from phagolysosomes to the cytosol and activating the NLRP1 inflammasome.

Structurally diverse stimuli trigger NLRP3 activation through several common intermediate cellular signals: cytosolic K+ efflux induced by extracellular ATP or pore-forming toxins, lysosomal membrane damage and cytosolic release of lysosomal cathepsin B, and ROS generation (19, 21, 42). In our study, we demonstrated that ATP, K+ efflux, and cathepsin B activity, but not ROS generation, were critically involved in H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β production. Similarly, ROS generation is not critical for NLRP3 inflammasome activation by Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan, or Streptococcus pneumoniae (41, 66–68). Given the role of ATP in promoting K+ efflux and cathepsin B release (68), our study results suggest that ATP released by MDM may act as the pivotal secondary signal in activating H. ducreyi-induced NLRP3 inflammasomes in an autocrine- or paracrine-like manner.

Macrophages are dynamic and heterogeneous cells whose phenotypes and functions are shaped by microenvironmental signals during infection. M1 and M2 cells represent extremes of a continuum of macrophage heterogeneity. Generally speaking, M1 macrophages are more microbicidal and produce high levels of proinflammatory cytokines and low levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, whereas M2 cells have higher phagocytic activity and produce fewer proinflammatory cytokines and more anti-inflammatory cytokines. We previously reported that lesional macrophages at H. ducreyi-infected sites express markers characteristic of M1 and M2 polarization. In vitro, M2c cells take up more H. ducreyi than M1 cells, whereas M1 cells have a higher killing activity with respect to the bacteria than M2a cells (11). In this study, we showed that macrophages skewed to the M1 or M2 states and infected with H. ducreyi downmodulated IL-1β processing and secretion, indicating that the production of inflammasome-dependent IL-1β is repressed by macrophage polarization. However, since macrophage polarization did not suppress H. ducreyi-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12, this suppression was specific to H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β production. We speculate that during H. ducreyi infection, macrophage polarization might dampen immunopathology through a less efficient activation of the inflammasomes.

The mechanisms by which macrophage polarization modulates inflammasome activation in response to H. ducreyi are unknown. It is conceivable that differential phagocytic and microbicidal activities generate different levels of inflammasome activators or inhibitors. Macrophage polarization might also affect the subcellular distribution of inflammasome proteins. Expression and posttranslational modification of inflammasome-associated proteins could also be responsible. IL-10, which is used to polarize MDM to the M2c state, downregulates the transcription of NLRP3 and many other genes in human monocytes (69). However, neither M2c polarization nor M1 and M2a polarization appeared to affect the expression of NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and caspase-5 proteins or H. ducreyi-induced pro-IL-1β, suggesting a possible role of posttranslational modifications in inflammasome activation. IFN-γ, a cytokine used in combination with LPS to generate the M1 cells, interferes with the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome through the production of nitric oxide and thio-nitrosylation of NLRP3 in murine macrophages (70). Since human macrophages produce much less NO than their murine counterparts in response to IFN-γ and/or LPS stimulation (71), whether a similar modification of NLRP3 by M1 polarization occurs in MDM is uncertain.

Inflammasome-induced production of IL-1β and IL-18 is a protective innate immune response to many intracellular and extracellular bacteria (22). However, inappropriate or excessive inflammasome activation and subsequent IL-1β production can have detrimental effects on the host due to immunopathology. For example, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β production are associated with more-severe diseases in mycobacterial infections (72, 73). Blockage of IL-1 family cytokine signaling is protective during pneumococcal meningitis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia (68, 74). IL-1β also has detrimental effects on Burkholderia pseudomallei lung infection (64). In experimental H. ducreyi infection, hyperinflammation is associated with pustule formation (12); whether inflammasome responses by H. ducreyi-infected macrophages cause hyperinflammation is unknown. Neutrophils, a major component of the abscess at H. ducreyi-infected sites, might also contribute to hyperinflammation through their capacity to process pro-IL-1β in inflammasome-dependent and -independent manners (75, 76). Future studies will focus on the role of macrophages and neutrophils in H. ducreyi-induced IL-1β production, hyperinflammation, and pustule formation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant AI059384 to S.M.S. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

We declare that we have no financial relationships representing conflicts of interest.

We thank Carlos H. Serezani for critical review of the manuscript. We thank Deborah Taxman and Joseph A. Duncan for providing shRNA-expressing THP-1 cell lines.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 10 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Spinola SM. 2008. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi, p 689–699 In Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, Cohen MS, Watts DH. (ed), Sexually transmitted diseases, 4th ed McGraw-Hill, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ussher JE, Wilson E, Campanella S, Taylor SL, Roberts SA. 2007. Haemophilus ducreyi causing chronic skin ulceration in children visiting Samoa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:e85–e87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McBride WJ, Hannah RC, Le Cornec GM, Bletchly C. 2008. Cutaneous chancroid in a visitor from Vanuatu. Australas. J. Dermatol. 49:98–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peel TN, Bhatti D, De Boer JC, Stratov I, Spelman DW. 2010. Chronic cutaneous ulcers secondary to Haemophilus ducreyi infection. Med. J. Aust. 192:348–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Janowicz DM, Ofner S, Katz BP, Spinola SM. 2009. Experimental infection of human volunteers with Haemophilus ducreyi: 15 years of clinical data and experience. J. Infect. Dis. 199:1671–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spinola SM, Wild LM, Apicella MA, Gaspari AA, Campagnari AA. 1994. Experimental human infection with Haemophilus ducreyi. J. Infect. Dis. 169:1146–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spinola SM, Bauer ME, Munson RS., Jr 2002. Immunopathogenesis of Haemophilus ducreyi infection (chancroid). Infect. Immun. 70:1667–1676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Banks KE, Humphreys T, Li W, Katz BP, Wilkes DS, Spinola SM. 2007. Haemophilus ducreyi partially activates human myeloid dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 75:5678–5685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li W, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Janowicz DM, Fortney KR, Katz BP, Spinola SM. 2010. Role played by CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in suppression of host responses to Haemophilus ducreyi during experimental infection of human volunteers. J. Infect. Dis. 201:1839–1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li W, Janowicz DM, Fortney KR, Katz BP, Spinola SM. 2009. Mechanism of human natural killer cell activation by Haemophilus ducreyi. J. Infect. Dis. 200:590–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li W, Katz BP, Spinola SM. 2012. Haemophilus ducreyi-induced IL-10 promotes a mixed M1 and M2 activation program in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 80:4426–4434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Humphreys T, Li L, Li X, Janowicz D, Fortney KR, Zhao Q, Li W, McClintick JN, Katz BP, Wilkes DS, Edenberg HJ, Spinola SM. 2007. Dysregulated immune profiles for skin and dendritic cells are associated with increased host susceptibility to Haemophilus ducreyi infection in human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 75:5686–5697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dinarello CA. 2009. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27:519–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elinav E, Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Flavell RA. 2011. Regulation of the antimicrobial response by NLR proteins. Immunity 34:665–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franchi L, Warner N, Viani K, Nunez G. 2009. Function of Nod-like receptors in microbial recognition and host defense. Immunol. Rev. 227:106–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. 2011. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29:707–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. 2002. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol. Cell 10:417–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martinon F, Tschopp J. 2004. Inflammatory caspases: linking an intracellular innate immune system to autoinflammatory diseases. Cell 117:561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schroder K, Tschopp J. 2010. The inflammasomes. Cell 140:821–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Faustin B, Lartigue L, Bruey JM, Luciano F, Sergienko E, Bailly-Maitre B, Volkmann N, Hanein D, Rouiller I, Reed JC. 2007. Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase-1 activation. Mol. Cell 25:713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bryant C, Fitzgerald KA. 2009. Molecular mechanisms involved in inflammasome activation. Trends Cell Biol. 19:455–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Moltke J, Ayres JS, Kofoed EM, Chavarria-Smith J, Vance RE. 2013. Recognition of bacteria by inflammasomes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31:73–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miao EA, Leaf IA, Treuting PM, Mao DP, Dors M, Sarkar A, Warren SE, Wewers MD, Aderem A. 2010. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 11:1136–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao Y, Yang J, Shi J, Gong YN, Lu Q, Xu H, Liu L, Shao F. 2011. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature 477:596–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kofoed EM, Vance RE. 2011. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature 477:592–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schattgen SA, Fitzgerald KA. 2011. The PYHIN protein family as mediators of host defenses. Immunol. Rev. 243:109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bauer ME, Goheen MP, Townsend CA, Spinola SM. 2001. Haemophilus ducreyi associates with phagocytes, collagen, and fibrin and remains extracellular throughout infection of human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 69:2549–2557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bauer ME, Townsend CA, Ronald AR, Spinola SM. 2006. Localization of Haemophilus ducreyi in naturally acquired chancroidal ulcers. Microbes Infect. 8:2465–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sander LE, Davis MJ, Boekschoten MV, Amsen D, Dascher CC, Ryffel B, Swanson JA, Muller M, Blander JM. 2011. Detection of prokaryotic mRNA signifies microbial viability and promotes immunity. Nature 474:385–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marina-García N, Franchi L, Kim YG, Miller D, McDonald C, Boons GJ, Nunez G. 2008. Pannexin-1-mediated intracellular delivery of muramyl dipeptide induces caspase-1 activation via cryopyrin/NLRP3 independently of Nod2. J. Immunol. 180:4050–4057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Banks KE, Fortney KR, Baker B, Billings SD, Katz BP, Munson RS, Jr, Spinola SM. 2008. The enterobacterial common antigen-like gene cluster of Haemophilus ducreyi contributes to virulence in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1531–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taxman DJ, Zhang J, Champagne C, Bergstralh DT, Iocca HA, Lich JD, Ting JP. 2006. Cutting edge: ASC mediates the induction of multiple cytokines by Porphyromonas gingivalis via caspase-1-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Immunol. 177:4252–4256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Willingham SB, Bergstralh DT, O'Connor W, Morrison AC, Taxman DJ, Duncan JA, Barnoy S, Venkatesan MM, Flavell RA, Deshmukh M, Hoffman HM, Ting JP. 2007. Microbial pathogen-induced necrotic cell death mediated by the inflammasome components CIAS1/cryopyrin/NLRP3 and ASC. Cell Host Microbe 2:147–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Skeldon A, Saleh M. 2011. The inflammasomes: molecular effectors of host resistance against bacterial, viral, parasitic, and fungal infections. Front. Microbiol. 2:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palmer KL, Schnizlein-Bick CT, Orazi A, John K, Chen CY, Hood AF, Spinola SM. 1998. The immune response to Haemophilus ducreyi resembles a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction throughout experimental infection of human subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1688–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spinola SM, Orazi A, Arno JN, Fortney K, Kotylo P, Chen CY, Campagnari AA, Hood AF. 1996. Haemophilus ducreyi elicits a cutaneous infiltrate of CD4 cells during experimental human infection. J. Infect. Dis. 173:394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miao EA, Rajan JV, Aderem A. 2011. Caspase-1-induced pyroptotic cell death. Immunol. Rev. 243:206–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. 2009. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:99–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bian ZM, Elner SG, Khanna H, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Patil S, Elner VM. 2011. Expression and functional roles of caspase-5 in inflammatory responses of human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52:8646–8656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Prantner D, Darville T, Sikes JD, Andrews CW, Jr, Brade H, Rank RG, Nagarajan UM. 2009. Critical role for interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) during Chlamydia muridarum genital infection and bacterial replication-independent secretion of IL-1beta in mouse macrophages. Infect. Immun. 77:5334–5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Chen S, Chiba N, Ramanujan VK, Vergnes L, Ojcius DM, Arditi M. 2011. Caspase-1 dependent IL-1beta secretion is critical for host defense in a mouse model of Chlamydia pneumoniae lung infection. PLoS One 6:e21477. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Broz P, Monack DM. 2011. Molecular mechanisms of inflammasome activation during microbial infections. Immunol. Rev. 243:174–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sahoo M, Ceballos-Olvera I, del Barrio L, Re F. 2011. Role of the inflammasome, IL-1beta, and IL-18 in bacterial infections. ScientificWorldJournal 11:2037–2050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Franchi L, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G. 2012. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat. Immunol. 13:325–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Kanneganti TD. 2011. Role of the nlrp3 inflammasome in microbial infection. Front. Microbiol. 2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Koizumi Y, Toma C, Higa N, Nohara T, Nakasone N, Suzuki T. 2012. Inflammasome activation via intracellular NLRs triggered by bacterial infection. Cell Microbiol. 14:149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Di Virgilio F. 2007. Liaisons dangereuses: P2X(7) and the inflammasome. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28:465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Kim YG, Chen G, Park JH, Franchi L, Vandenabeele P, Nunez G. 2007. Pannexin-1-mediated recognition of bacterial molecules activates the cryopyrin inflammasome independent of Toll-like receptor signaling. Immunity 26:433–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lopez-Castejon G, Theaker J, Pelegrin P, Clifton AD, Braddock M, Surprenant A. 2010. P2X(7) receptor-mediated release of cathepsins from macrophages is a cytokine-independent mechanism potentially involved in joint diseases. J. Immunol. 185:2611–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hornung V, Latz E. 2010. Critical functions of priming and lysosomal damage for NLRP3 activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 40:620–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tschopp J, Schroder K. 2010. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: the convergence of multiple signalling pathways on ROS production? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen CC, Tsai SH, Lu CC, Hu ST, Wu TS, Huang TT, Said-Sadier N, Ojcius DM, Lai HC. 2012. Activation of an NLRP3 inflammasome restricts Mycobacterium kansasii infection. PLoS One 7:e36292. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McNeela EA, Burke A, Neill DR, Baxter C, Fernandes VE, Ferreira D, Smeaton S, El-Rachkidy R, McLoughlin RM, Mori A, Moran B, Fitzgerald KA, Tschopp J, Petrilli V, Andrew PW, Kadioglu A, Lavelle EC. 2010. Pneumolysin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes proinflammatory cytokines independently of TLR4. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001191. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. He X, Mekasha S, Mavrogiorgos N, Fitzgerald KA, Lien E, Ingalls RR. 2010. Inflammation and fibrosis during Chlamydia pneumoniae infection is regulated by IL-1 and the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome. J. Immunol. 184:5743–5754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jones JW, Kayagaki N, Broz P, Henry T, Newton K, O'Rourke K, Chan S, Dong J, Qu Y, Roose-Girma M, Dixit VM, Monack DM. 2010. Absent in melanoma 2 is required for innate immune recognition of Francisella tularensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:9771–9776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. O'Connor W, Jr, Harton JA, Zhu X, Linhoff MW, Ting JP. 2003. Cutting edge: CIAS1/cryopyrin/PYPAF1/NALP3/CATERPILLER 1.1 is an inducible inflammatory mediator with NF-kappa B suppressive properties. J. Immunol. 171:6329–6333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA, Hornung V, Latz E. 2009. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J. Immunol. 183:787–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gurung P, Malireddi RK, Anand PK, Demon D, Walle LV, Liu Z, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. 2012. Toll or interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-beta (TRIF)-mediated caspase-11 protease production integrates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) protein- and Nlrp3 inflammasome-mediated host defense against enteropathogens. J. Biol. Chem. 287:34474–34483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Abdelaziz DH, Gavrilin MA, Akhter A, Caution K, Kotrange S, Khweek AA, Abdulrahman BA, Grandhi J, Hassan ZA, Marsh C, Wewers MD, Amer AO. 2011. Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC) controls Legionella pneumophila infection in human monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 286:3203–3208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lin XY, Choi MS, Porter AG. 2000. Expression analysis of the human caspase-1 subfamily reveals specific regulation of the CASP5 gene by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma. J. Biol. Chem. 275:39920–39926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McCoy AJ, Koizumi Y, Higa N, Suzuki T. 2010. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation via NLRP3/NLRC4 inflammasomes mediated by aerolysin and type III secretion system during Aeromonas veronii infection. J. Immunol. 185:7077–7084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brodsky IE, Palm NW, Sadanand S, Ryndak MB, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Bliska JB, Medzhitov R. 2010. A Yersinia effector protein promotes virulence by preventing inflammasome recognition of the type III secretion system. Cell Host Microbe 7:376–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fang R, Tsuchiya K, Kawamura I, Shen Y, Hara H, Sakai S, Yamamoto T, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yang R, Hernandez-Cuellar E, Dewamitta SR, Xu Y, Qu H, Alnemri ES, Mitsuyama M. 2011. Critical roles of ASC inflammasomes in caspase-1 activation and host innate resistance to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. J. Immunol. 187:4890–4899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ceballos-Olvera I, Sahoo M, Miller MA, Del Barrio L, Re F. 2011. Inflammasome-dependent pyroptosis and IL-18 protect against Burkholderia pseudomallei lung infection while IL-1beta is deleterious. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002452. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Atianand MK, Duffy EB, Shah A, Kar S, Malik M, Harton JA. 2011. Francisella tularensis reveals a disparity between human and mouse NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Biol. Chem. 286:39033–39042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shimada T, Park BG, Wolf AJ, Brikos C, Goodridge HS, Becker CA, Reyes CN, Miao EA, Aderem A, Gotz F, Liu GY, Underhill DM. 2010. Staphylococcus aureus evades lysozyme-based peptidoglycan digestion that links phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, and IL-1beta secretion. Cell Host Microbe 7:38–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dorhoi A, Nouailles G, Jorg S, Hagens K, Heinemann E, Pradl L, Oberbeck-Muller D, Duque-Correa MA, Reece ST, Ruland J, Brosch R, Tschopp J, Gross O, Kaufmann SH. 2012. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is uncoupled from susceptibility to active tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 42:374–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hoegen T, Tremel N, Klein M, Angele B, Wagner H, Kirschning C, Pfister HW, Fontana A, Hammerschmidt S, Koedel U. 2011. The NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to brain injury in pneumococcal meningitis and is activated through ATP-dependent lysosomal cathepsin B release. J. Immunol. 187:5440–5451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gopinathan U, Ovstebo R, Olstad OK, Brusletto B, Dalsbotten Aass HC, Kierulf P, Brandtzaeg P, Berg JP. 2012. Global effect of interleukin-10 on the transcriptional profile induced by Neisseria meningitidis in human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 80:4046–4054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mishra BB, Rathinam VA, Martens GW, Martinot AJ, Kornfeld H, Fitzgerald KA, Sassetti CM. 2013. Nitric oxide controls the immunopathology of tuberculosis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent processing of IL-1beta. Nat. Immunol. 14:52–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Weinberg JB, Misukonis MA, Shami PJ, Mason SN, Sauls DL, Dittman WA, Wood ER, Smith GK, McDonald B, Bachus KE, et al. 1995. Human mononuclear phagocyte inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS): analysis of iNOS mRNA, iNOS protein, biopterin, and nitric oxide production by blood monocytes and peritoneal macrophages. Blood 86:1184–1195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Carlsson F, Kim J, Dumitru C, Barck KH, Carano RA, Sun M, Diehl L, Brown EJ. 2010. Host-detrimental role of Esx-1-mediated inflammasome activation in mycobacterial infection. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000895. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mishra BB, Moura-Alves P, Sonawane A, Hacohen N, Griffiths G, Moita LF, Anes E. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein ESAT-6 is a potent activator of the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome. Cell Microbiol. 12:1046–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schultz MJ, Rijneveld AW, Florquin S, Edwards CK, Dinarello CA, van der Poll T. 2002. Role of interleukin-1 in the pulmonary immune response during Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 282:L285–L290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cho JS, Guo Y, Ramos RI, Hebroni F, Plaisier SB, Xuan C, Granick JL, Matsushima H, Takashima A, Iwakura Y, Cheung AL, Cheng G, Lee DJ, Simon SI, Miller LS. 2012. Neutrophil-derived IL-1beta is sufficient for abscess formation in immunity against Staphylococcus aureus in mice. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003047. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Netea MG, Simon A, van de Veerdonk F, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW, Joosten LA. 2010. IL-1beta processing in host defense: beyond the inflammasomes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000661. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Al-Tawfiq JA, Thornton AC, Katz BP, Fortney KR, Todd KD, Hood AF, Spinola SM. 1998. Standardization of the experimental model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection in human subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1684–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stevens MK, Latimer JL, Lumbley SR, Ward CK, Cope LD, Lagergard T, Hansen EJ. 1999. Characterization of a Haemophilus ducreyi mutant deficient in expression of cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 67:3900–3908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Palmer KL, Thornton AC, Fortney KR, Hood AF, Munson RS, Jr, Spinola SM. 1998. Evaluation of an isogenic hemolysin-deficient mutant in the human model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection. J. Infect. Dis. 178:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Young RS, Fortney KR, Gelfanova V, Phillips CL, Katz BP, Hood AF, Latimer JL, Munson RS, Jr, Hansen EJ, Spinola SM. 2001. Expression of cytolethal distending toxin and hemolysin are not required for pustule formation by Haemophilus ducreyi in human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 69:1938–1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]