Abstract

An airway-selective DNase-hypersensitive site (DHS) at kb −35 (DHS-35kb) 5′ to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene is evident in many lung cell lines and primary human tracheal epithelial cells but is absent from intestinal epithelia. The DHS-35kb contains an element with enhancer activity in 16HBE14o- airway epithelial cells and is enriched for monomethylated H3K4 histones (H3K4me1). We now define a 350-bp region within DHS-35kb which has full enhancer activity and binds interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) and nuclear factor Y (NF-Y) in vitro and in vivo. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated depletion of IRF1 or overexpression of IRF2, an antagonist of IRF1, reduces CFTR expression in 16HBE14o- cells. NF-Y is critical for maintenance of H3K4me1 enrichment at DHS-35kb since depletion of NF-YA, a subunit of NF-Y, reduces H3K4me1 enrichment at this site. Moreover, depletion of SETD7, an H3K4 monomethyltransferase, reduces both H3K4me1 and NF-Y occupancy, suggesting a requirement of H3K4me1 for NF-Y binding. NF-Y depletion also represses Sin3A and reduces its occupancy across the CFTR locus, which is accompanied by an increase in p300 enrichment at multiple sites. Our results reveal that the DHS-35kb airway-selective enhancer element plays a pivotal role in regulation of CFTR expression by two independent regulatory mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple regulatory mechanisms orchestrate the tight control that is essential for the normal expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. Mutations in CFTR cause the common inherited disorder cystic fibrosis (CF). CFTR expression levels in different tissues vary widely, with about 10,000-fold fewer transcripts in adult human lung epithelium than in epithelia within pancreatic ducts, small intestine, and colon (1–4), suggesting that its regulation in human airways is distinct from that in other tissues. Though the basal promoter of CFTR is required for gene expression (5, 6), tissue specificity is conferred by cis-regulatory elements located outside the promoter, and recruitment of a distinct set of cis elements occurs in different cell types (6–9). We previously identified intestine-specific enhancers in introns 1 and 11 of the CFTR gene that act cooperatively to increase its expression in colon carcinoma cells (4, 7, –12). Moreover, we, along with others, demonstrated that these cis-acting enhancers are brought in close proximity to the CFTR promoter by chromosome looping in the active locus (4, 13). In contrast, we showed that critical CFTR cis-regulatory elements in the airway were located in DNase I-hypersensitive sites (DHS) at kb −35 and kb −3.4 5′ to the translation start site and in intron 23 (designated DHS-35kb, DHS-3.4kb, and DHS23, respectively) (14). Additional airway-selective DHS were seen at kb −44, in introns 18 and 19, and at kb +21.5 and kb +36.6 (3′ to the last exon) (4, 14). The DHS-35kb, DHS-3.4kb, and DHS23 elements were enriched for monomethylated histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1) (15) and showed cooperative enhancer activity in 16HBE14o- airway epithelial cells (14). The DHS at kb −35 encompasses 1.6 kb of genomic DNA that drives enhancer activity in luciferase reporter assays in airway cells but is inactive in intestinal epithelial cells (14) (Fig. 1A). DHS-35kb is evident in several human airway cell lines that express abundant CFTR including simian virus 40 (SV40) ori− immortalized 16HBE14o- cells (16) and Calu3 lung adenocarcinoma cells (17, 18), and is just detectable in human tracheal (HTE) and bronchial (NHBE) epithelial cells that express low levels of CFTR. However, the DHS is not seen in Caco2 colon carcinoma cells (4, 14, 17). Here, we further characterize the DHS-35kb cis-regulatory element, identify trans-acting factors, and demonstrate its functional contribution to airway regulation of CFTR. The airway-selective expression of CFTR appears to be controlled by two independent mechanisms at this distal cis-regulatory element.

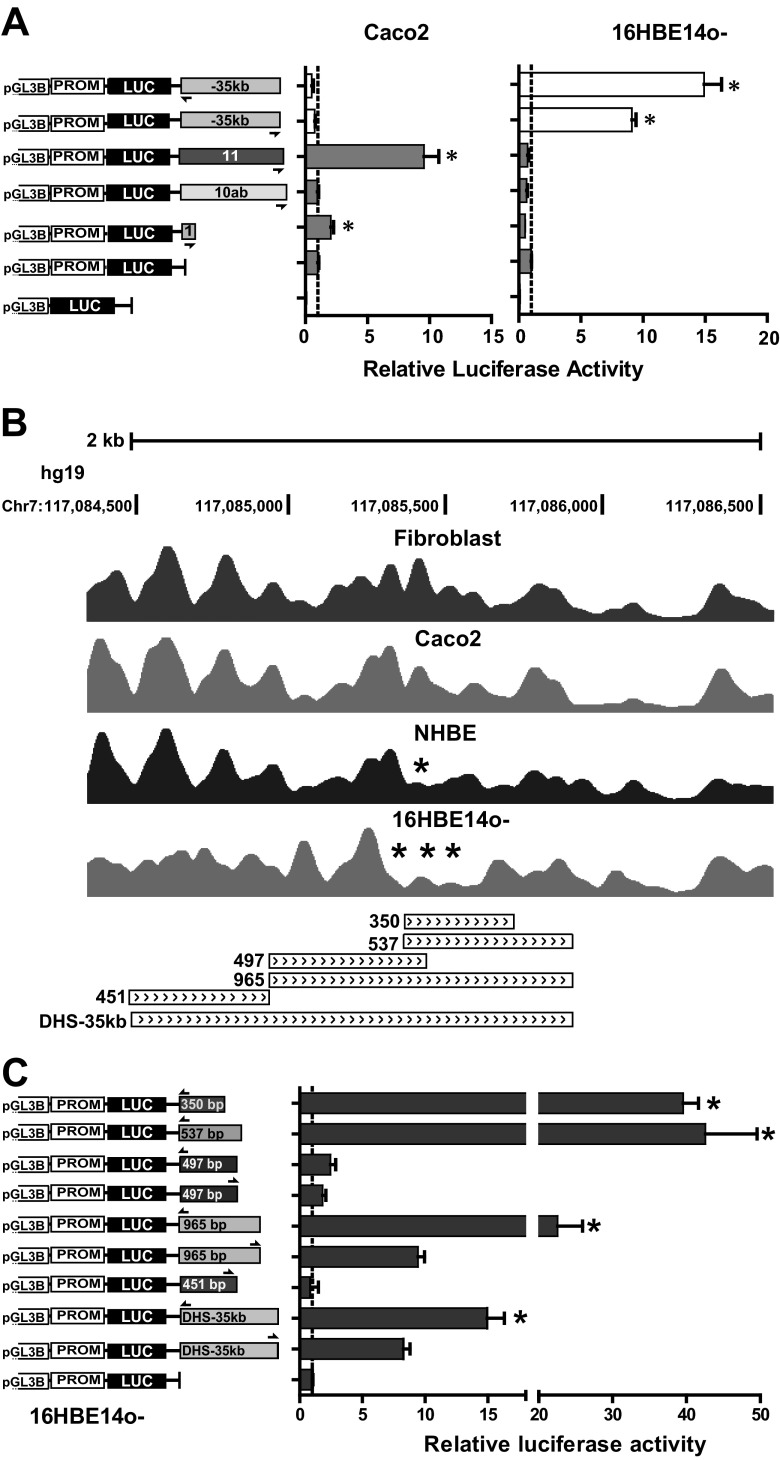

Fig 1.

Enhancer activity of the DHS-35kb region is cell type selective and is located in a nucleosome-depleted 350-bp fragment. (A) Airway-selective enhancer activities of DHS-35kb (14). Data show luciferase activities relative to the CFTR basal promoter vector (= 1). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean (n = 6; *, P < 0.001, using unpaired t tests). (B) Nucleosome occupancy across the DHS-35kb core in fibroblasts, Caco2, NHBE, and 16HBE14o- cells (adapted from reference 24 with permission of the publisher). *, specific depletion of a nucleosome at the DHS core. Truncations of the DHS-35kb region that were assayed for enhancer activity are shown below. The 350-bp fragment located at the nucleosome-depleted region in 16HBE14o- cells has full enhancer activity. (C) 16HBE14o- cells were transfected with pGL3B luciferase reporter constructs containing the 787-bp CFTR basal promoter (pGL3B 245) and DHS-35kb fragments cloned into the enhancer site of the vector in either forward or reverse orientations, as shown by half arrows. Data show luciferase activities relative to the CFTR basal promoter vector (= 1). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean (n = 6; *, P < 0.001 using unpaired t tests).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

NHBE cells, a mixture of primary human bronchial and tracheal epithelial cells (CC-2541; Lonza), were cultured in bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM; Lonza) per the manufacturer's instructions. 16HBE14o- human bronchial epithelial cells (16), Calu3 lung carcinoma cells (17, 18), and Caco2 colon carcinoma cells (19) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% serum.

Plasmids and reporter assays.

Sequences encompassing DHS-35kb (human genome build 19, chromosome 7 [hg 19, chr7]:117084449 to 117086049) and subfragments (Fig. 1) of 965 bp (hg 19, chr7:117084943 to 117085907), 451 bp (hg 19, chr7:117084505 to 117084955), 497 bp (hg 19, chr7:117084943 to 117085439), 537 bp (hg 19, chr7:117085370 to 117085907), and 350 bp (hg 19, chr7:117085371 to 117085720) were amplified using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and inserted into the enhancer site of the pGL3B 245 luciferase reporter vector which is driven by a 787-bp CFTR basal promoter fragment (10). Primers are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The constructs (and a modified pRL, Renilla luciferase control reporter [Promega, Madison, WI]) were transiently transfected into 16HBE14o- cells with Lipofectin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) per the manufacturer's instruction. Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were measured 48 h after transfection by standard methods (20).

In vitro DNase I footprinting.

The minimal 350-bp DHS-35kb [DHS-35kb(350)] enhancer element (hg 19, chr7:117085371 to 117085720) was amplified with Pfu DNA polymerase (for primers, see Table S1) and cloned into the pSC-B vector using a StrataClone Blunt PCR cloning kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Cleavage of this construct with XhoI and SmaI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) enabled Klenow DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) fill-in with [32P]dCTP. DNase I footprinting experiments were then performed as described previously (21).

EMSA.

Complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides spanning DNase I footprint 1 (FP1) and FP2 were annealed and labeled with [32P]dCTP using Klenow DNA polymerase. Electrophoretic mobility gel shift assays (EMSAs) were done by standard protocols (21) (probes and competitor sequences are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material). Antibodies (1 to 2 μg) specific for interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) (sc-497; Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), IRF2 (ABE115; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), nuclear factor Y subunit A (NF-YA) (ab6558; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), HNF1β (sc-7411), and HOXA9 (07-178; Millipore) were used for supershift assays.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

A total of 1 × 107 cells were cross-linked with 0.37% (for histone modifications) or 1% (for transcription factors) formaldehyde for 10 min, and the reaction was stopped with glycine at 0.125 M. Cross-linked chromatin was sonicated to 200 to 500 bp and immunoprecipitated using 3 to 10 μg of antibodies specific for NF-YB (Pab001; Genespin, Italy), IRF1 (sc-497x), Sin3A (sc-994x), p300 (sc-585x) (all from Santa Cruz), H3K4me1 (07-436; Millipore), and normal rabbit IgG (Millipore 12-370 or Santa Cruz sc-2027) as described previously (14). Enrichments were analyzed relative to IgG by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using FastStart SYBR green master mix (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). qPCR primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were located at airway-selective DHS at kb −44, kb −35, and kb −3.4, in introns 19 and 23, and at kb +15.6, kb +21.5, and kb +36.6 (14). Additional primers were located at critical regulatory elements including a CTCF-enriched insulator DHS at kb −20.9 (22), promoter at kb −2 (upstream of the translation start site), a basal promoter region (kb −0.5), DHS10c in intron 10 (hg 19, chr7:117222349 to 117223049), and intestine-specific enhancer sites at introns 1 and 11 (4).

Transient siRNA-mediated depletion of IRF1, SETD7, NF-YA, or Sin3A and cDNA-encoded overexpression of IRF1, IRF2, or NF-Y subunits.

siRNA targeted at IRF1 (sc-35706), SETD7 (sc-44094), NF-YA (sc-29947), Sin3A (EHU082221; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and relevant negative controls (sc-37007 and EHUFLUC) were reverse transfected into 16HBE14o- cells by Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) per the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were harvested 72 h after transfection to isolate whole-cell lysate and total RNA. cDNA clones of IRF1 (SC118744; OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD), IRF2 (SC118745), or NF-YA short/long isoforms, NF-YB, and NF-YC (gifts from Roberto Mantovani) were transfected into 16HBE14o- cells by Lipofectin (Life Technologies) per the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were harvested at 48 h (luciferase assays) or 72 h (Western blotting) after transfection. For cotransfection of both siRNA and cDNA, cDNA was first transfected into 16HBE14o- cells by Lipofectin in serum-free medium for 12 h, and then siRNA was introduced by Lipofectamine RNAiMAX with serum. Cells were harvested 48 h after siRNA transfection.

To examine the direct influence of each binding factor on the enhancer alone, the relevant cDNA clones were transfected with the pRL Renilla luciferase control reporter and pGL3-245 or pGL3-245 containing the minimal 350 bp of DHS-35kb at the enhancer site by Lipofectin.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were lysed by standard protocols using 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (1% Igepal CA-630 [Sigma-Aldrich], 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA). Western blots of whole-cell lysates were probed with antibodies specific for IRF1, IRF2, SETD7, Sin3A, NF-YA, H3K4me1, and β-tubulin (T4026; Sigma-Aldrich). The results were analyzed using the Adobe Photoshop lasso tool (Adobe Photoshop CS5 Extended) to calculate protein expression relative to β-tubulin expression. All of the protein quantitation experiments were repeated at least twice.

qRT-PCR (quantitative reverse transcription-PCR).

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). cDNA synthesis was performed by TaqMan reverse-transcription reactions (Roche Applied Science). CFTR expression was measured using a TaqMan primer/probe set spanning CFTR exons 5 and 6 (21, 23). Relative gene expression levels were calculated after normalization with an internal control 18S rRNA. Primer sequences are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

Identification of a 350-bp sequence containing the minimal airway enhancer element of DHS-35kb.

The DHS-35kb region exhibits cell type specificity since it has enhancer activity in 16HBE14o- airway cells but not in Caco2 intestinal cells (Fig. 1A). To identify the minimal airway enhancer element at DHS-35kb, 350- to 965-bp subfragments (Fig. 1B) of the 1.6-kb DHS region were generated by PCR and inserted into the enhancer site of the pGL3B 245 vector. In this vector luciferase reporter gene expression is driven by a 787-bp CFTR basal promoter fragment (10). The constructs were transiently transfected into 16HBE14o- cells, and firefly luciferase activities were measured relative to a Renilla luciferase control at 48 h after transfection. The 1.6-kb DHS-35 kb sequence showed 8.2-fold enhancement in comparison to pGL3 245 in the forward orientation with respect to the promoter and 14.9-fold enhancement in the reverse orientation. Fragments of 451 bp and 497 bp at the 5′ end and middle of the DHS had no enhancer activity, but a 965-bp fragment and, within it, 537 bp in the 3′ half of the DHS showed between 10- and 40-fold enhancement (Fig. 1C). Within the 537-bp fragment a 350-bp region had maximal enhancer activity. This 350-bp fragment coincides with a region of cell type-selective nucleosome depletion that we identified previously in 16HBE14o- cells in comparison to skin fibroblasts and Caco2 cells (24) (Fig. 1B). The nucleosome-free region coincides with a peak of enrichment for BAF155 (a component of the SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin structure [SMARC]) (24). The data suggest that the 350-bp DNA fragment identified in 16HBE14o- cells serves as the core enhancer element at DHS-35kb. Moreover, since BAF155 is recruited by many different transcription factors, its presence in this region suggests that important transcription factors are also interacting here.

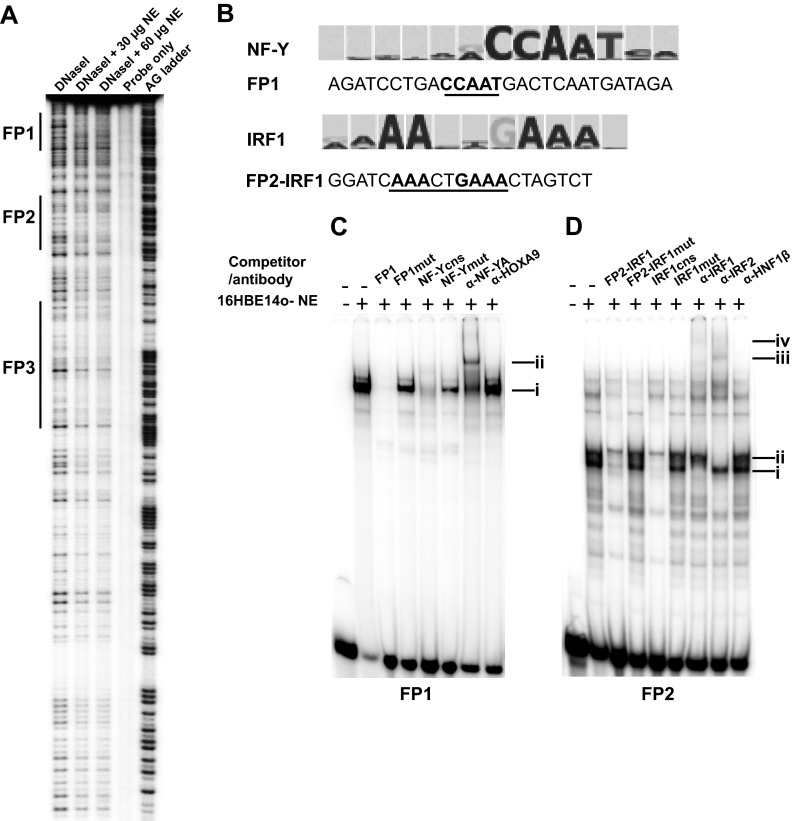

Transcription factors NF-Y and IRF1 are recruited to the DHS-35kb enhancer.

To identify the transcription factor binding sites at the 350-bp enhancer element, in vitro DNase I footprinting was performed. Three footprints (FP1, FP2, and FP3) were observed when 16HBE14o- nuclear extracts were incubated with a 32P-labeled probe for the sense strand of the 350-bp DNA fragment (Fig. 2A). To predict putative transcription factor (TF)-binding sites within FP1 to FP3 (31 bp, 35 bp, and 42 bp, respectively), we performed in silico analysis using MatInspector (http://www.genomatix.de). Multiple TF binding sites were found, but we examined only candidate factors relevant to airway cell biology or CFTR expression and excluded those with known functions restricted to other differentiated lineages. Potential binding sites for CDP, MEF, HNF6, and PBX1/MEIS occur within FP1, but preliminary experiments generated no robust evidence for the interactions of these factors (data not shown), so they will not be considered further here. A CCAAT binding site on the plus strand of FP1 was shown not to bind C/EBP and thus became a candidate for interaction with nuclear factor Y (NF-Y) (Fig. 2B). NF-Y protein, also known as CAAT binding factor (CBF), is a ubiquitous transcription factor that recognizes the CCAAT motif and influences local histone modifications such as H3K4me1 (25, 26). It is composed of three subunits, NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC (27–30), all of which are essential for sequence-specific DNA binding (27).

Fig 2.

NF-Y and IRF1 bind to the DHS-35kb(350) core fragment in vitro. (A) In vitro footprinting reveals three distinct protected regions, FP1, FP2, and FP3. The 32P-labeled 350-bp enhancer element probe was digested by DNase I, alone or after incubation with 30 μg or 60 μg of nuclear extract from 16HBE14o- cells. The AG ladder provides a sequence reference. (B) Comparison of footprints FP1 and FP2 with consensus matrices for NF-Y and IRF1. (C) EMSAs show in vitro binding of NF-Y to an FP1 probe. 16HBE14o- nuclear extracts (NE) were incubated with a 32P-labeled FP1 probe. DNA-protein complex (i) is competed by 100× molar excess of unlabeled FP1 probe and by an NF-Y/CBF consensus probe (cns suffix) but not by mutant versions (mut suffix) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). A supershift (ii) is seen on incubation of the DNA-protein complex with an antibody specific for NF-YA but not with the isotype control (HOXA9). (D) EMSAs show in vitro binding of IRF1 and IRF2 to an FP2 probe. 16HBE14o- nuclear extracts were incubated with a 32P-labeled FP2 probe. DNA-protein complexes (i and ii) are competed by a 100× molar excess of unlabeled FP2-IRF1 probe (a shorter version of FP2 encompassing the predicted IRF1 binding site only) and by an IRF1 consensus probe but not by mutant versions (see Table S1). Supershifts (iii and iv) are seen on incubation of the DNA-protein complex with antibodies specific for IRF1 (iv) and IRF2 (iii) but not with an isotype control (HNF1β).

The strongest candidate predicted to bind to the sense strand of FP2 was interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) (Fig. 2B). The IRF1 binding site consensus sequence is GAAANNGAAA(G/C)(T/C), and both IRF1 and IRF2 may be recruited to this site. These proteins, which are members of the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family of transcription factors, are structurally related, particularly in their N-terminal regions, which confer DNA binding specificity (31, 32). IRF1 is well characterized in the context of the enhancer-mediated activation of interferon and interferon-inducible genes after exposure of cells to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; one component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria) (33). IRF2, which is constitutively expressed by many cell types, inhibits IRF1 function by direct competition at their common consensus DNA-binding motifs and suppresses gene expression (34–36). No relevant candidate transcription factors were predicted to bind in FP3, so this element was not examined further here.

Next, EMSAs were performed to determine whether NF-Y and IRF1 bound in vitro to FP1 and FP2, respectively. Nuclear extracts from 16HBE14o- cells were incubated with 32P-labeled double-stranded DNA probes encompassing the FP1 or FP2 sequence (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (Fig. 2C and D). FP1 generated a single major DNA-protein complex (Fig. 2C and D, complex i), and the interaction was specific, as shown by effective competition with a 100-fold molar excess of the corresponding unlabeled probe (Fig. 2C). Competition with an NF-Y/CBF consensus oligonucleotide (37) and lack of competition by the same consensus carrying a mutation in the CCAAT element confirmed the interaction of NF-Y protein at this site. The same mutation in the FP1 probe also abolished its ability to compete. Finally, addition of an antibody specific for NF-Y subunit A (NF-YA) caused a supershift (Fig. 2C, complex ii), showing that NF-YA contributed to the complex. An isotype control antibody (anti-HOXA9) had no effect.

In EMSAs with the FP2 probe, two major protein-DNA complexes (Fig. 2D, i and ii) were observed which were competed by a 100-fold molar excess of FP2-IRF1, a shorter version of FP2 encompassing the predicted IRF1 binding site, and by an IRF1 consensus site oligonucleotide (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The equivalent mutant IRF1 consensus site oligonucleotide and FP2-IRF1mut, with a mutation in the IRF binding site, failed to compete the complexes (Fig. 2D). Finally, supershift experiments with antibodies specific for IRF1 and IRF2 both retarded (complexes iii and iv) parts of the main protein complex binding at FP2. Complex i was shifted with the IRF1 antibody, and complex ii was shifted with the IRF2 antibody. The isotype control antibody specific for HNF1β had no effect on the mobility of complexes i and ii.

IRF1 contributes to high CFTR expression levels in 16HBE14o- bronchial epithelial cells.

To confirm IRF1 binding at DHS-35kb in vivo, ChIP experiments were performed using an antibody specific for IRF1. IRF1 was enriched 5-fold over IgG at DHS-35kb in 16HBE14o- cells and 4-fold in Calu3 cells, another airway line that expresses high levels of CFTR (Fig. 3A). In contrast, NHBE cells, which express low levels of CFTR (14), showed only 2-fold enrichment of IRF1 at this site, and DHS-35kb was only weakly evident. These data suggest a role for IRF1 in vivo at the DHS-35kb enhancer; however, this is unlikely to be a cell-type-selective function since nearly 4-fold enrichment of IRF1 is also seen in this genomic region in Caco2 colon carcinoma cells, which do not exhibit DHS-35kb (Fig. 3A). The ChIP data also showed enrichment of IRF1 at the DHS in intron 19 and at DHS+15.6kb and DHS+21.5kb 3′ to the locus in several cell types although the functional significance of these interactions will not be considered here.

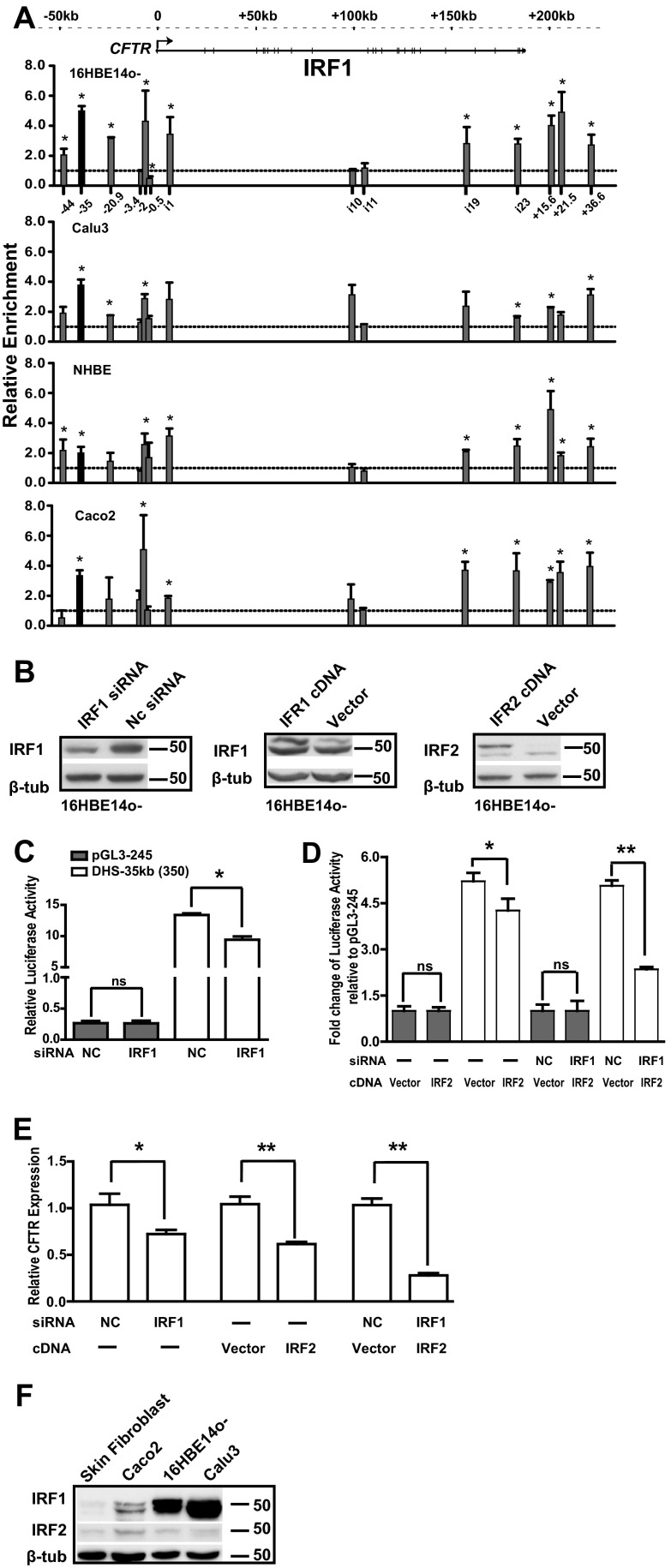

Fig 3.

IRF1 binds to the DHS-35kb region in airway epithelial cells and together with IRF2 modulates CFTR expression. (A) IRF1 binds the cis-regulatory element at DHS-35kb in vivo. ChIP was performed with an antibody specific for IRF1 followed by qPCR analysis of chromatin from 16HBE14o-, Calu3, NHBE, and Caco2 cells. Primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) are located at multiple DHS across the locus, as shown on the x axis of the top graph. IRF1 enrichment is shown relative to the IgG control ChIP (lines at 1.0). Data are combined from at least two ChIP experiments and are normalized to 18S rRNA levels and then IgG; error bars represent standard errors of the means of at least two ChIP experiments. *, P < 0.05, using an unpaired t test. The CFTR locus is shown at the top of the figure. (B) Western blot analysis to show the efficiency of knockdown or overexpression of IRF1 and IRF2 in 16HBE14o- cells. (C and D) siRNA-mediated IRF1 knockdown or overexpression of IRF2 suppresses the DHS-35kb enhancer (350-bp minimal fragment) activity in 16HBE14o- cells. pGL3 245 or pGL3 245 DHS-35kb(350) was transfected first alone or with an IRF2 cDNA clone (pCMV-XL5-hIRF2 cDNA) or vector plasmid (pCMV-XL5), and then after 12 h with an siRNA targeting human IRF1 or a negative-control siRNA (NC). The cells were harvested 36 h after initial transfection. The gray bars show the relative activity of the CFTR promoter (pGL3 245), and white bars show the activity of the enhancer [pGL3-245 DHS-35kb(350)] compared to that of the Renilla vector (C) or to pGL3B 245, set to 1 (D). Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n ≥ 6; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001, using an unpaired t test). (E) IRF1 and IRF2 show antagonistic regulation of CFTR expression in 16HBE14o- cells. siRNA targeting human IRF1, a negative-control siRNA (NC), and/or an IRF2 expression plasmid (pCMV-XL5-hIRF2 cDNA) or vector plasmid (pCMV-XL5) was transfected into 16HBE14o- cells, and cells were lysed after 48 to 72 h to evaluate CFTR expression. CFTR mRNA levels assayed by TaqMan qRT-PCR from total RNA are shown. Results were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n ≥ 9; *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001, using an unpaired t test). (F) Endogenous expression of IRF1 and IRF2 in different cell types.

Since IRF1 and IRF2 are known to bind to the same consensus motif and since IRF1 is known to be an activator of gene expression while IRF2 usually functions as a repressor, we next evaluated the impact of IRF1 and IRF2 on the DHS-35kb(350) enhancer element defined in in vitro luciferase assays (Fig. 1C). Overexpression of IRF1 (Fig. 3B) had no effect on the enhancer activity of DHS-35kb(350) in 16HBE14o- cells (data not shown), as would be expected given the very high levels of endogenous IRF1 in this cell line (Fig. 3F). However, siRNA-mediated depletion of IRF1 (40%) (Fig. 3B) resulted in a 30% decrease in luciferase activity driven by the enhancer (Fig. 3C). A 4-fold increase in IRF2 levels following transfection of the cDNA (Fig. 3B) also significantly reduced DHS-35kb(350) enhancer activity (by 37%) (Fig. 3D). Further, when IRF2 overexpression was combined with IRF1 siRNA-mediated depletion, enhancer activity decreased to about 50% of the control values (Fig. 3D). Next, we examined the effects of IRF1 and IRF2 expression on endogenous CFTR expression in airway epithelial cells. To achieve this, we changed the IRF1/IRF2 ratio by siRNA-mediated depletion of IRF1, overexpression of exogenous IRF2 by transient transfection of its cDNA into 16HBE14o- cells, or both. When IRF1 protein was depleted to 40% of its normal levels, the expression of CFTR mRNA fell by 28% by 72 h after siRNA transfection (Fig. 3E). Moreover, when IRF2 protein was overexpressed, CFTR mRNA levels were reduced by 40% at 48 h after transfection (Fig. 3E). Sequential cotransfection of both IRF1 siRNA and IRF2 cDNA repressed CFTR mRNA levels by 80% (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that IRF1 plays a role as an activator and IRF2 as a repressor of CFTR expression, and these functions may in part be mediated by interactions with the DHS-35kb enhancer element.

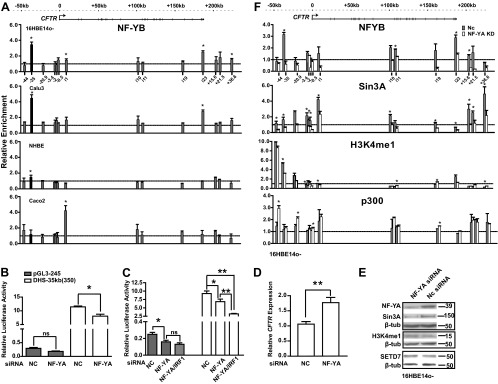

NF-Y recruits monomethylated histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1) to DHS-35kb.

All three subunits of the NF-Y complex are required for stable binding to DNA (27). However, since robust ChIP-grade antibodies are currently available only for NF-YB, we evaluated the interaction of this subunit across the CFTR locus by ChIP. NF-YB binding showed some cell type specificity, with ∼4-fold enrichment at DHS-35kb in both 16HBE14o- and Calu3 airway cells, which express high levels of CFTR, but only 1.2-fold enrichment in NHBE cells expressing low levels of CFTR (Fig. 4A). In Caco2 intestinal cells NF-YB was enriched (∼5-fold) only at the intestine-specific enhancer in intron 1 and not at DHS-35kb. Thus, NF-YB enrichment at DHS-35kb correlated with the presence or absence of DHS at kb −35 in the four different cell types, suggesting that NF-Y has a specific role in CFTR expression in the airway.

Fig 4.

NF-Y regulates CFTR expression by stabilizing H3K4me1 at the DHS-35kb core. (A) NF-YB binds the cis-regulatory element at DHS-35kb in vivo. ChIP with an antibody specific for NF-YB was performed, followed by qPCR analysis of chromatin from 16HBE14o-, Calu3, NHBE, and Caco2 cells. Primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) are located at multiple DHS across the locus, as shown on the x axis of the top graph. NF-YB enrichment is shown relative to the IgG control ChIP (lines at 1.0). Data are presented as described in the legend of Fig. 3A legend. (B and C) siRNA-mediated knockdown of NF-YA alone or NF-YA and IRF1 in combination represses the DHS-35kb(350) enhancer element in 16HBE14o- cells. pGL3-245 or pGL3-245 DHS-35kb(350) was transfected into 16HBE14o- cells first; 12 h later NF-YA siRNA alone (B) or with IRF1 siRNA (C) was transfected. Luciferase assays were done 36 h after the initial transfection. The gray bars show CFTR promoter activity, and white bars show the enhancer activity relative to the Renilla vector. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n ≥ 6; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001, using an unpaired t test). (D) NF-Y represses CFTR expression in 16HBE14o- cells. NF-YA siRNA and a negative control (NC) were transfected into 16HBE14o- cells. Cells were lysed after 72 h to evaluate CFTR mRNA expression by TaqMan qRT-PCR from total RNA. Results were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n > 9; **, P < 0.001, using an unpaired t test). (E) Western blot analysis shows the efficiency of NF-YA depletion by siRNA and concurrent reduction of Sin3A (but not SETD7 or H3K4me1) in 16HBE14o- cells. (F) NF-YA depletion reduces binding of NF-YB, Sin3A, and H3K4me1 at DHS-35kb in 16HBE14o- cells. 16HBE14o- cells were reverse transfected for 72 h with siRNA targeting human NF-YA (white bars) or a negative control (NC, gray bars). ChIP with antibodies specific for NF-YB, Sin3A, H3K4me1, or p300 was performed, followed by qPCR analysis of chromatin from 16HBE14o- cells. Primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) are located at multiple DHS across the locus, as shown on the x axis of the top graph. NF-YB, Sin3A, H3K4me1, and p300 enrichment is shown relative to the IgG control ChIP (lines at 1.0). Data are from a single representative ChIP experiment (though each experiment was repeated at least twice and shown to be consistent) and are normalized to 18S rRNA levels. Error bars represent standard errors of the means of at least two PCRs for biological replicas of each fragment. The CFTR locus is shown at the top of the figure.

To further examine the specific effect of NF-Y on the DHS-35kb(350) enhancer element, transient transfections were carried out with the luciferase reporter constructs.

siRNA-mediated loss of NF-YA (75%) (Fig. 4E) significantly reduced (by 30%) the enhancer activity of DHS-35kb(350) (Fig. 4B and C; the single asterisk indicates a P value of <0.05). This suggests that NF-Y has an important role as an activator of the enhancer element. Next, luciferase reporter gene assays were done with NF-YA and IRF1 siRNA-mediated depletion concurrently, and the combined repression (66%) of the DHS-35kb(350) enhancer was significantly greater than with NF-YA depletion alone (Fig. 4C; the double asterisks indicate a P value of <0.001). These data indicate independent mechanisms for NF-Y and IRF activation of the DHS-35kb(350) element. However, in contrast, siRNA-mediated depletion of NF-YA in 16HBE14o- cells increased CFTR expression ∼2-fold (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the NF-Y complex has other roles in regulating CFTR expression which are dominant to its activating role in the DHS-35kb enhancer. A possible explanation is provided by the repression (45%) of Sin3A by NF-YA siRNA depletion (Fig. 4E), which is accompanied by loss of enrichment of Sin3A at DHS-35kb and other sites across the whole CFTR locus (Fig. 4F). Sin3A is a transcriptional corepressor that directly recruits histone deacetylase 1/2 (HDAC1/2) (38, 39), and since DHS-35kb itself is enriched with H3K4me1 (14), we next investigated whether alterations in NF-YA changed histone modification profiles.

We examined the enrichment of H3K4me1 and p300, a histone acetyltransferase (40), across the locus in 16HBE14o- cells after siRNA-mediated depletion of NF-YA, which will also result in loss of NF-YB binding to DNA. Loss of NF-YA had no effect on global levels of H3K4me1 or SETD7, a histone H3K4 methyltransferase, as shown by Western blotting (Fig. 4E). Levels of NF-YB and H3K4me1 decreased at DHS-35kb after NF-YA knockdown in comparison to negative-control siRNA transfection, suggesting that NF-Y is critical for H3K4me1 methylation at DHS-35kb (Fig. 4F). Concurrently, p300 enrichment at DHS across the CFTR locus showed a minor increase after NF-YA depletion but was most evident at DHS-44kb (Fig. 4F), suggesting a previously unidentified role for this element in CFTR expression in the airway. As DHS-44kb and DHS-35kb are always evident simultaneously in airway cells, it may not be surprising that they are functionally linked.

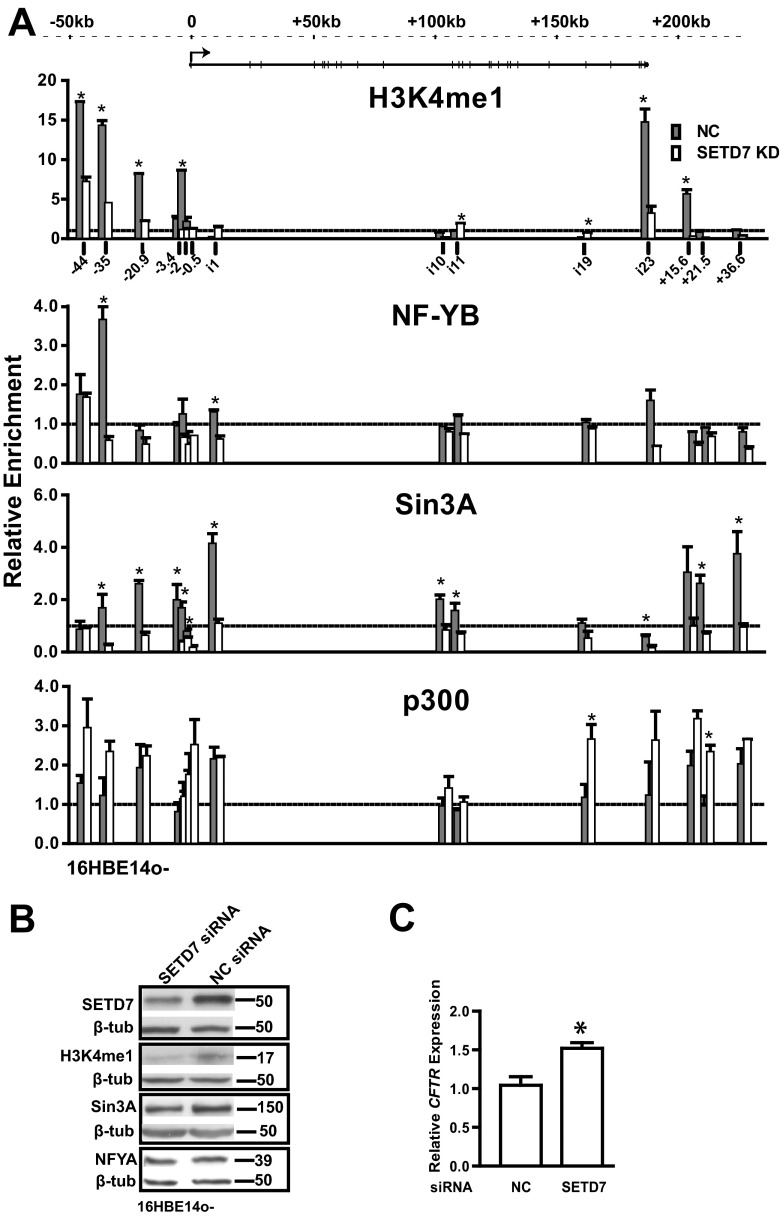

Effects of H3K4me1 on transcription factor recruitment at DHS-35kb in 16HBE14o- cells.

DHS-35kb is marked by H3K4me1 in both 16HBE14o- and Caco2 cells; however, the enhancer element functions only in 16HBE14o- airway cells (14). Moreover, NF-Y binding at this site is evident in 16HBE14o- but not Caco2 cells. We hypothesized that the H3K4me1 epigenetic modification might facilitate recruitment of tissue-specific transcription factors in 16HBE14o- cells. To test this hypothesis, SETD7, a methyltransferase that generates monomethylated H3 lysine 4, was targeted by siRNA-mediated knockdown, and the levels of H3K4me1 as shown by Western blotting decreased by 50% in 16HBE14o- cells (Fig. 5B). Depletion of SETD7 greatly reduced the H3K4me1 mark at DHS-35kb and at multiple other DHS across the CFTR locus (Fig. 5A). Moreover, depletion of SETD7 was accompanied by loss of NF-YB enrichment at DHS across the CFTR locus, suggesting that NF-Y binding may be dependent on H3K4me1 at multiple sites in addition to DHS-35kb. Another effect of SETD7 depletion was a reduction in Sin3A enrichment at DHS across the locus in 16HBE14o- cells, which was accompanied by an increase in p300 enrichment (Fig. 5A). Concurrently, a 50% depletion of SETD7 by siRNA-mediated knockdown increased CFTR mRNA expression levels by 1.5-fold (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5.

Reduction of H3K4me1 by SETD7 depletion decreases NF-Y binding at DHS-35kb and increases p300 binding across the CFTR locus and CFTR gene expression in 16HBE14o- cells. (A) SETD7 depletion alters enrichment of H3K4me1, NF-YB, Sin3A, and p300 at DHS-35kb in 16HBE14o- cells. 16HBE14o- cells were reverse transfected for 72 h with an siRNA targeting human SETD7 (SETD7 KD) or a negative control (NC). ChIP with antibodies specific for H3K4me1, NF-YB, Sin3A, or p300, followed by qPCR analysis of chromatin from 16HBE14o- cells, shows enrichment relative to the IgG control (lines at 1.0). Primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) are located at multiple DHS across the locus, as shown on the top graph. Data are presented as described in the legend of Fig. 4F. (B) Western blot analysis showing the efficiency of SETD7 siRNA-mediated depletion and an associated reduction in H3K4me1 protein in 16HBE14o- cells. Sin3A and NF-YA abundance remain unchanged. (C) SETD7 depletion increases CFTR expression in 16HBE14o- cells. siRNA targeting human SETD7 and a negative control (NC) were transfected into 16HBE14o- cells. Cells were lysed after 72 h to evaluate CFTR mRNA expression by TaqMan qRT-PCR from total RNA. Results were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n > 9; *, P < 0.01, using an unpaired t test).

Sin3A represses CFTR expression in 16HBE14o- cells.

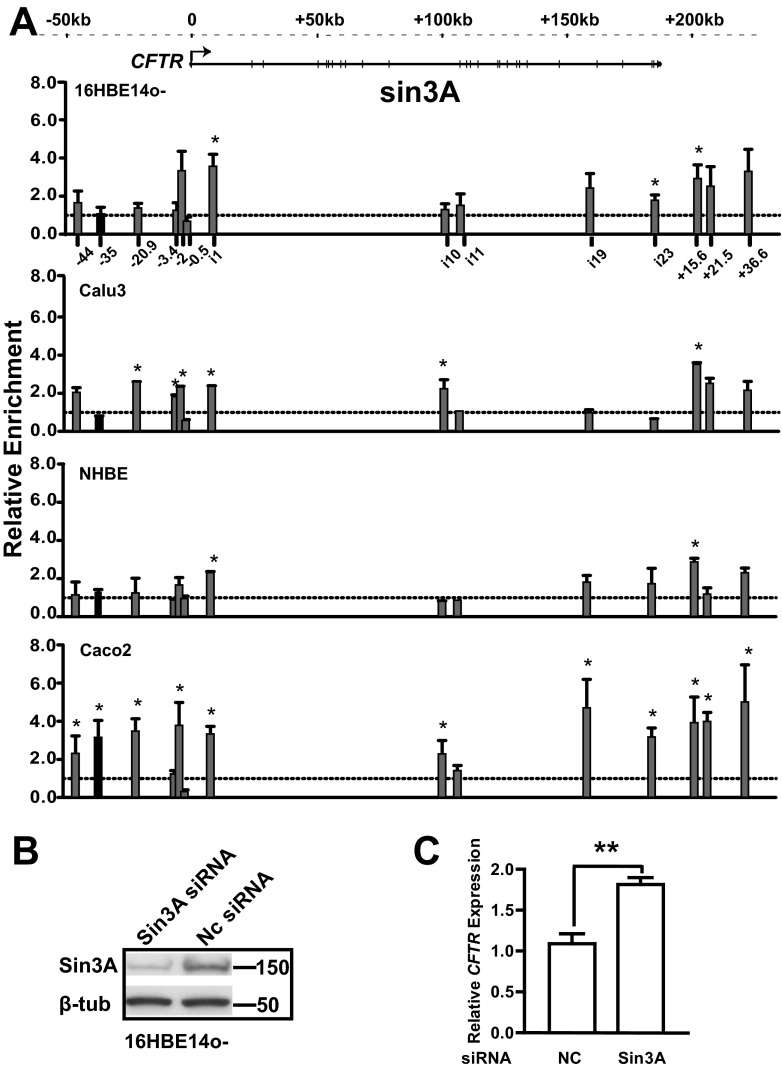

Our data on SETD7 and NF-Y suggested that Sin3A might play a key role in regulating CFTR expression in the airway. To investigate this directly, we performed ChIP with an antibody specific for Sin3A to measure Sin3A occupancy at DHS across the locus in 16HBE14o-, Calu3, and NHBE airway cells and in Caco2 intestinal cells (Fig. 6A). Of particular note is the lack of Sin3A at DHS-35kb in the three airway cells, but a 4-fold enrichment of Sin3A was observed at this site in intestinal Caco2 cells (where the DHS is not evident). Moreover, siRNA-mediated depletion of Sin3A (70%) in 16HBE14o- cells, confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 6B), resulted in a nearly 2-fold increase (P < 0.001) of CFTR expression (Fig. 6C), suggesting that Sin3A may have a critical role in repressing CFTR expression in the airway.

Fig 6.

Sin3A regulates CFTR expression in 16HBE14o- cells. (A) Sin3A occupancy across the CFTR locus in 16HBE14o-, Calu3, NHBE, and Caco2 cells. ChIP was performed with an antibody specific for Sin3A followed by qPCR analysis of chromatin from each cell line. Primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) are located at multiple DHS across the locus, as shown on the x axis of the top graph. Sin3A enrichment is shown relative to the IgG control ChIP (lines at 1.0). Data are presented as described in the legend of Fig. 3A. (B) Western blot analysis shows effective siRNA-mediated depletion of Sin3A in 16HBE14o- cells. (C) Sin3A represses CFTR expression in 16HBE14o- cells. Sin3A siRNA and a negative control (NC) were transfected into 16HBE14o- cells. Cells were lysed after 72 h to evaluate CFTR mRNA expression by TaqMan qRT-PCR from total RNA. Results were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n > 9; **, P < 0.001, using an unpaired t test).

DISCUSSION

Through investigation of a distal cis-regulatory element at kb −35 5′ to the CFTR promoter and its associated trans-acting factors, we identified novel regulatory mechanisms for CFTR expression in airway epithelial cells. A 350-bp region that encompasses an enhancer element at the DHS-35kb core binds both the NF-Y and IRF1/2 transcription factors in vitro and in vivo. Though mediators of the immune response were implicated previously in regulating CFTR mRNA and protein expression, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. The cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) were shown to downregulate CFTR mRNA in intestinal epithelial cells by decreasing mRNA stability but not the rate of transcription (41, 42). In contrast, IFN-γ was reported to upregulate CFTR mRNA in rat and human mast cells (43). The interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family is a group of transcription factors that play critical roles in the immune response, immune cell development, and regulation of cell growth and apoptosis (32, 44, 45). IRF1, the IRF family member identified first, is induced by IFN-γ in most cell types, and it binds to the promoter region of IFN-γ-responsive genes, activating their expression. IRF2 is also induced by IFN-γ but is synthesized after IRF1 expression and acts as an IRF1 antagonist. Our data identify an IRF1 binding site at the DHS-35kb tissue-specific enhancer element and show that both IRF1 and IRF2 can bind at this site in 16HBE14o- airway epithelial cells. Moreover, the competition between these two factors is seen to modulate CFTR expression levels. These results suggest that IRF1 and IRF2, which are critical components of the immune response, directly influence CFTR expression and, hence, can modulate CFTR-mediated transmembrane Cl− conductance in human airways.

Though IRF1 and IRF2 are both expressed in many epithelial cell types and thus would not be obvious candidates for tissue-specific regulation of CFTR expression, the ratio between these two factors could play an important role and show cell type specificity. IRF2 is generally more abundant and stable than IRF1 in growing cells, but the levels of IRF1 increase substantially following stimulation by IFN or viruses (46, 47). Consistent with these observations, in cultured primary human tracheal and bronchial epithelial cells, IRF2 is robustly expressed, while levels of IRF1 mRNA are very low (48; also data not shown). However, our Western blot data show very high levels of IRF1 in both 16HBE14o- and Calu3 cells. This is consistent with microarray data (data not shown) demonstrating that IRF1 mRNA levels are much higher than those of IRF2 in both of these cell lines. Moreover, these results are consistent with Calu3 cell data from other investigators (Oncomine database [https://www.oncomine.org]). This difference in the IRF1/IRF2 ratio could underlie the mechanism that maintains low CFTR expression in primary airway cells but supports abundant CFTR mRNA in 16HBE14o- and Calu3 cells.

In vivo enrichment of NF-YB at DHS-35kb coincides with the presence of this hypersensitive site in 16HBE14o- and Calu3 cells. NF-Y has an important role early in transcriptional activation when it binds to the CCAAT box at active promoters by replacing H2A/H2B, with which it has structurally similarities. This replacement results in a region of open chromatin, which is readily accessible to specific histone modifications and facilitates the binding of transcription factors that, in turn, complete the process of gene activation (30, 49, 50). Here, we show that DHS-35kb is enriched for H3K4me1 and NF-Y in 16HBE14o- cells, suggesting that NF-Y may function at this airway-specific enhancer by facilitating histone monomethylation on H3K4. Since siRNA-mediated depletion of NF-YA decreased Sin3A levels and increased p300 occupancy across the whole CFTR locus, NF-Y may have a more global role in maintaining monomethylation of H3 lysine 4 across the gene. Similar to NF-YA knockdown, siRNA-mediated depletion of SETD7 removed the H3K4me1 mark, decreased Sin3A occupancy, and increased p300 binding at many sites across the CFTR locus, causing elevated CFTR expression. Concurrently, SETD7 knockdown abolished NF-Y binding at DHS-35kb, suggesting that the H3K4me1 epigenetic modification is required for NF-Y recruitment to this enhancer. Our data on the contribution of Sin3A to mediating these epigenetic modifications are of additional interest since a role for Sin3A in regulating CFTR expression in the airway was identified recently using a completely different approach (51).

The NF-Y complex can act as a link between epigenetic modification and transcriptional activity (30). NF-Y, in complex with p53, Sin3, and HDAC1, apparently inhibits estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) gene expression in human breast cancer cells (52). Moreover, SETDB1, another histone methyltransferase of H3K4, also interacts with HDAC1/2 and Sin3A/B (53). Hence, we envisage a mechanism whereby NF-Y forms a complex including IRF1/IRF2, H3K4me1, and SETD7 at DHS-35kb, which controls CFTR expression in airway epithelial cells. Our data suggest that airway-specific regulation of CFTR expression is mediated by sequences within DHS-35kb and that this depends on molecular mechanisms that involve both transcription factor binding and epigenetic modification of histones. These two processes are of fundamental importance at many sites across the locus though their relative contributions at individual regulatory elements may vary. This is consistent with an overall model in which cell-type-specific transcription factors bind at multiple but distinct sites across the CFTR locus and, through three-dimensional interactions, bring these sites in close proximity to the gene promoter. Simultaneously, a higher-order organization is maintained by separate structural elements outside (and possibly within) the gene that isolates it from transcriptional interference by nearby loci.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL094585 and R01HD068901) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

We thank Calvin Cotton, Case Western Reserve University, for HTE cells and Roberto Mantovani for the NF-YB antibody and NF-YA, -YB, and -YC plasmids.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 May 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00003-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou J-L, Drumm ML, Iannuzzi MC, Collins FS, Tsui L-C. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245:1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trezise AEO, Chambers JA, Wardle CJ, Gould S, Harris A. 1993. Expression of the cystic fibrosis gene in human foetal tissues. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kreda SM, Mall M, Mengos A, Rochelle L, Yankaskas J, Riordan JR, Boucher RC. 2005. Characterization of wild-type and ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in human respiratory epithelia. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:2154–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ott CJ, Blackledge NP, Kerschner JL, Leir S-H, Crawford GE, Cotton CU, Harris A. 2009. Intronic enhancers coordinate epithelial-specific looping of the active CFTR locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19934–19939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koh J, Sferra TJ, Collins FS. 1993. Characterization of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator promoter region. Chromatin context and tissue-specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 268:15912–15921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshimura K, Nakamura H, Trapnell BC, Dalemans W, Pavirani A, Lecocq JP, Crystal RG. 1991. The cystic fibrosis gene has a “housekeeping”-type promoter and is expressed at low levels in cells of epithelial origin. J. Biol. Chem. 266:9140–9144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ott CJ, Blackledge NP, Leir S-H, Harris A. 2009. Novel regulatory mechanisms for the CFTR gene. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37:843–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ott CJ, Harris A. 2011. Genomic approaches for the discovery of CFTR regulatory elements. Transcription 2:23–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gillen AE, Harris A. 2012. Transcriptional regulation of CFTR gene expression. Front. Biosci. (Elite ed) 4:587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith AN, Barth ML, McDowell TL, Moulin DS, Nuthall HN, Hollingsworth MA, Harris A. 1996. A regulatory element in intron 1 of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. J. Biol. Chem. 271:9947–9954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ott CJ, Suszko M, Blackledge NP, Wright JE, Crawford GE, Harris A. 2009. A complex intronic enhancer regulates expression of the CFTR gene by direct interaction with the promoter. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13:680–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kerschner JL, Harris A. 2012. Transcriptional networks driving enhancer function in the CFTR gene. Biochem. J. 446:203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gheldof N, Smith EM, Tabuchi TM, Koch CM, Dunham I, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dekker J. 2010. Cell-type-specific long-range looping interactions identify distant regulatory elements of the CFTR gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:4325–4336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Z, Ott CJ, Lewandowska MA, Leir S-H, Harris A. 2012. Molecular mechanisms controlling CFTR gene expression in the airway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 16:1321–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou VW, Goren A, Bernstein BE. 2011. Charting histone modifications and the functional organization of mammalian genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12:7–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cozens AL, Yezzi MJ, Kunzelmann K, Ohrui T, Chin L, Eng K, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH, Gruenert DC. 1994. CFTR expression and chloride secretion in polarized immortal human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 10:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fogh J, Fogh JM, Orfeo T. 1977. One hundred and twenty-seven cultured human tumor cell lines producing tumors in nude mice. J. Nat. Cancer Inst. 59:221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shen BQ, Finkbeiner WE, Wine JJ, Mrsny RJ, Widdicombe JH. 1994. Calu-3: a human airway epithelial cell line that shows cAMP-dependent Cl− secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 266:L493–L501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fogh J, Wright WC, Loveless JD. 1977. Absence of hela cell contamination in 169 cell lines derived from human tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 58:209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Phylactides M, Rowntree R, Nuthall H, Ussery D, Wheeler A, Harris A. 2002. Evaluation of potential regulatory elements identified as DNase I hypersensitive sites in the CFTR gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:553–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mouchel N, Henstra SA, McCarthy VA, Williams SH, Phylactides M, Harris A. 2004. HNF1α is involved in tissue-specific regulation of CFTR gene expression. Biochem. J. 378:909–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blackledge NP, Carter EJ, Evans JR, Lawson V, Rowntree RK, Harris A. 2007. CTCF mediates insulator function at the CFTR locus. Biochem. J. 408:267–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mouchel N, Broackes-Carter F, Harris A. 2003. Alternative 5′ exons of the CFTR gene show developmental regulation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12:759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yigit E, Bischof JM, Zhang Z, Ott CJ, Kerschner JL, Leir S-H, Buitrago-Delgado E, Zhang Q, Wang J-PZ, Widom J, Harris A. 2013. Nucleosome mapping across the CFTR locus identifies novel regulatory factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:2857–2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donati G, Gatta R, Dolfini D, Fossati A, Ceribelli M, Mantovani R. 2008. An NF-Y-dependent switch of positive and negative histone methyl marks on CCAAT promoters. PLoS One 3:e2066. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gatta R, Mantovani R. 2008. NF-Y substitutes H2A-H2B on active cell-cycle promoters: recruitment of CoREST-KDM1 and fine-tuning of H3 methylations. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:6592–6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27. Mantovani R. 1999. The molecular biology of the CCAAT-binding factor NF-Y. Gene 239:15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hatamochi A, Golumbek PT, Vanschaftingen E, Decrombrugghe B. 1988. A CCAAT DNA-binding factor consisting of two different components that are both required for DNA-binding. J. Biol. Chem. 263:5940–5947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim IS, Sinha S, deCrombrugghe B, Maity SN. 1996. Determination of functional domains in the C subunit of the CCAAT-binding factor (CBF) necessary for formation of a CBF-DNA complex: CBF-B interacts simultaneously with both the CBF-A and CBF-C subunits to form a heterotrimeric CBF molecule. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:4003–4013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dolfini D, Gatta R, Mantovani R. 2012. NF-Y and the transcriptional activation of CCAAT promoters. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 47:29–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tanaka N, Kawakami T, Taniguchi T. 1993. Recognition DNA sequences of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2, regulators of cell growth and the interferon system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4531–4538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taniguchi T, Ogasawara K, Takaoka A, Tanaka N. 2001. IRF family of transcription factors as regulators of host defense. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:623–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lohoff M, Mak TW. 2005. Roles of interferon-regulatory factors in T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang Y, Liu D-P, Chen P-P, Koeffler HP, Tong X-J, Xie D. 2007. Involvement of IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-1 and IRF-2 in the formation and progression of human esophageal cancers. Cancer Res. 67:2535–2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harada H, Fujita T, Miyamoto M, Kimura Y, Maruyama M, Furia A, Miyata T, Taniguchi T. 1989. Structurally similar but functionally distinct factors, IRF-1 and IRF-2, bind to the same regulatory elements of IFN and IFN-inducible genes. Cell 58:729–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harada H, Willison K, Sakakibara J, Miyamoto M, Fujita T, Taniguchi T. 1990. Absence of the type I IFN system in EC cells: transcriptional activator (IRF-1) and repressor (IRF-2) genes are developmentally regulated. Cell 63:303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shiraga T, Winpenny JP, Carter EJ, McCarthy VA, Hollingsworth MA, Harris A. 2005. MZF-1 and DbpA interact with DNase I hypersensitive sites that correlate with expression of the human MUC1 mucin gene. Exp. Cell Res. 308:41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nagy L, Kao H-Y, Chakravarti D, Lin RJ, Hassig CA, Ayer DE, Schreiber SL, Evans RM. 1997. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell 89:373–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roopra A, Sharling L, Wood IC, Briggs T, Bachfischer U, Paquette AJ, Buckley NJ. 2000. Transcriptional repression by neuron-restrictive silencer factor is mediated via the Sin3-histone deacetylase complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2147–2157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vo N, Goodman RH. 2001. CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:13505–13508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Besancon F, Przewlocki G, Baro I, Hongre AS, Escande D, Edelman A. 1994. Interferon-gamma downregulates CFTR gene expression in epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol 267:C1398–C1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nakamura H, Yoshimura K, Bajocchi G, Trapnell BC, Pavirani A, Crystal RG. 1992. Tumor necrosis factor modulation of expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. FEBS Lett. 314:366–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kulka M, Dery R, Nahirney D, Duszyk M, Befus AD. 2005. Differential regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by interferon γ in mast cells and epithelial cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315:563–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. 2008. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26:535–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Savitsky D, Tamura T, Yanai H, Taniguchi T. 2010. Regulation of immunity and oncogenesis by the IRF transcription factor family. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 59:489–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Harada H, Kitagawa M, Tanaka N, Yamamoto H, Harada K, Ishihara M, Taniguchi T. 1993. Anti-oncogenic and oncogenic potentials of interferon regulatory factors-1 and -2. Science 259:971–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abdollahi A, Lord K, Hoffman-Liebermann B, Liebermann D. 1991. Interferon regulatory factor 1 is a myeloid differentiation primary response gene induced by interleukin 6 and leukemia inhibitory factor: role in growth inhibition. Cell Growth Differ. 2:401–407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bischof JM, Ott CJ, Leir S-H, Gosalia N, Song L, London D, Furey TS, Cotton CU, Crawford GE, Harris A. 2012. A genome-wide analysis of open chromatin in human tracheal epithelial cells reveals novel candidate regulatory elements for lung function. Thorax 67:385–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Baxevanis AD, Arents G, Moudrianakis EN, Landsman D. 1995. A variety of DNA-binding and multimeric proteins contain the histone fold motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2685–2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Romier C, Cocchiarella F, Mantovani R, Moras D. 2003. The NF-YB/NF-YC structure gives insight into DNA binding and transcription regulation by CCAAT factor NF-Y. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1336–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ramachandran S, Karp PH, Jiang P, Ostedgaard LS, Walz AE, Fisher JT, Keshavjee S, Lennox KA, Jacobi AM, Rose SD, Behlke MA, Welsh MJ, Xing Y, McCray PB. 2012. A microRNA network regulates expression and biosynthesis of wild-type and ΔF508 mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:13362–13367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. De Amicis F, Giordano F, Vivacqua A, Pellegrino M, Panno ML, Tramontano D, Fuqua SAW, Andò S. 2011. Resveratrol, through NF-Y/p53/Sin3/HDAC1 complex phosphorylation, inhibits estrogen receptor α gene expression via p38MAPK/CK2 signaling in human breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 25:3695–3707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yang L, Mei Q, Zielinska-Kwiatkowska A, Matsui Y, Blackburn ML, Benedetti D, Krumm AA, Taborsky GJ, Chansky HA. 2003. An ERG (ETS-related gene)-associated histone methyltransferase interacts with histone deacetylases 1/2 and transcription corepressors mSin3A/B. Biochem. J. 369:651–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.