Abstract

Combination therapy may be required for multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii. This study systematically investigated bacterial killing and emergence of colistin resistance with colistin and rifampin combinations against MDR A. baumannii. Studies were conducted over 72 h in an in vitro pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamic (PD) model at inocula of ∼106 and ∼108 CFU/ml using two MDR clinical isolates of A. baumannii, FADDI-AB030 (colistin susceptible) and FADDI-AB156 (colistin resistant). Three combination regimens achieving clinically relevant concentrations (constant colistin concentration of 0.5, 2, or 5 mg/liter and a rifampin maximum concentration [Cmax] of 5 mg/liter every 24 hours; half-life, 3 h) were investigated. Microbiological response was measured by serial bacterial counts. Population analysis profiles assessed emergence of colistin resistance. Against both isolates, combinations resulted in substantially greater killing at the low inoculum; combinations containing 2 and 5 mg/liter colistin increased killing at the high inoculum. Combinations were additive or synergistic at 6, 24, 48, and 72 h with all colistin concentrations against FADDI-AB030 and FADDI-AB156 in, respectively, 8 and 11 of 12 cases (i.e., all 3 combinations) at the 106-CFU/ml inoculum and 8 and 7 of 8 cases with the 2- and 5-mg/liter colistin regimens at the 108-CFU/ml inoculum. For FADDI-AB156, killing by the combination was ∼2.5 to 7.5 and ∼2.5 to 5 log10 CFU/ml greater at the low inoculum (all colistin concentrations) and high inoculum (2 and 5 mg/liter colistin), respectively. Emergence of colistin-resistant subpopulations was completely suppressed in the colistin-susceptible isolate with all combinations at both inocula. Our study provides important information for optimizing colistin-rifampin combinations against colistin-susceptible and -resistant MDR A. baumannii.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistance in Gram-negative bacteria is a serious concern (1, 2). Indeed, the World Health Organization has identified antimicrobial resistance as one of the three greatest threats to human health (3). Compounding this problem is a lack of novel antimicrobial agents in the drug development pipeline for infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens (2, 4). Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii is an increasingly important nosocomial pathogen which causes significant morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients (2, 5). Current treatment options for infections caused by A. baumannii are severely limited (6). Colistin (also known as polymyxin E), a previously abandoned polymyxin antibiotic, has reemerged as a last-resort therapeutic option (7–9). Unfortunately, the increased usage of colistin has led to the emergence of colistin resistance among clinical isolates of A. baumannii (10–12), threatening the future utility of this increasingly important antibiotic.

Of serious concern is that colistin heteroresistance, defined as the presence of resistant subpopulations within an isolate that is considered susceptible based upon its MIC, has been reported in a number of Gram-negative pathogens, including A. baumannii (13–18). Heteroresistance has been shown to contribute to regrowth following colistin monotherapy due to selective amplification of colistin-resistant subpopulations (14, 16–20), highlighting the importance of investigating rational combinations of colistin with other antibiotics. In recent years, rifampin has been used in patients in combination with colistin for the treatment of MDR Gram-negative infections (21–23), most likely due to results from in vitro studies that suggest synergy (24–30). None of these studies examined the impact of a high initial inoculum, which mimics the high bacterial densities found in some infections, on bacterial killing or emergence of colistin resistance of A. baumannii; importantly, none of the aforementioned studies utilized clinically relevant antibiotic dosage regimens. Studies of colistin-rifampin combinations in animal infection models (27, 30, 31) have provided equivocal results regarding the value of the combination (32), possibly due to the selection of antibiotic doses that did not fully account for animal scaling effects on pharmacokinetics, resulting in low in vivo concentrations. Thus, the aim of the present study was to systematically investigate the effect of colistin alone and in combination with rifampin on bacterial killing against MDR A. baumannii at two inocula and the emergence of colistin resistance. This was achieved using an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model in which the pharmacokinetics of colistin and rifampin in critically ill patients were simulated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Two clinical isolates of A. baumannii were used in this study: a colistin-susceptible MDR isolate, FADDI-AB030, and a colistin-resistant MDR isolate, FADDI-AB156. MICs of colistin (sulfate) and rifampin were 0.5 mg/liter and 64 mg/liter, respectively, for FADDI-AB030 and 16 mg/liter for both antibiotics for FADDI-AB156. MICs were determined in three replicates on separate days using broth microdilution (33) in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB; Ca2+ at 23.0 mg/liter, Mg2+ at 12.2 mg/liter) (Oxoid, Adelaide, Australia). Resistance to colistin was defined as an MIC of ≥4 mg/liter (33). Each isolate was stored in tryptone soy broth (Oxoid) with 20% glycerol (Ajax Finechem, Seven Hills, New South Wales, Australia) at −80°C in cryovials (Simport Plastics, Quebec, Canada).

Antibiotics and reagents.

For MIC determinations and in vitro PK/PD studies, colistin sulfate (C4461, lot number 118K0945; ≥15,000 U/mg) and rifampin (R3501, lot number 080M1506V) were used (Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill, Australia). Colistin sulfate was employed in the current study, as colistin is the active antibacterial agent formed in vivo after administration of its inactive prodrug, colistin methanesulfonate (CMS) (34). Stock solutions of colistin and rifampin were prepared immediately prior to each experiment. Colistin was dissolved in Milli-Q water (Millipore Australia, North Ryde, Australia) and sterilized by passage through a 0.20-μm cellulose acetate syringe filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Rifampin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma) and then serially diluted in filter-sterilized Milli-Q water to the desired final concentration; preliminary studies demonstrated that the final concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide (0.06% [vol/vol]) to which the bacteria were exposed had no effect on their growth. All other chemicals were from previously described suppliers (16).

Binding of antibiotics in growth medium.

We have previously demonstrated that colistin is unbound in CAMHB (35). The binding of rifampin in CAMHB was measured using polytetrafluoroethylene equilibrium dialyzer units containing two 1-ml chambers (Dianorm, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) separated by a regenerated cellulose semipermeable membrane with a molecular mass cutoff of 10 kDa. Rifampin was spiked into CAMHB (donor chamber) to achieve a concentration of 5 mg/liter and dialyzed at 37°C against the same volume of isotonic phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (acceptor chamber); samples were prepared in three replicates. Samples of CAMHB and buffer were removed from each reservoir after 4 h (shown in preliminary studies to be sufficient time for equilibration) and immediately analyzed as described below. The unbound fraction of rifampin (ƒu) was calculated as the ratio of the rifampin concentration in buffer to that in CAMHB.

In vitro PK/PD model and antibiotic dosage regimens.

Experiments to examine the microbiological response and emergence of resistance to various dosage regimens of colistin and rifampin alone and in combination were conducted over 72 h at two different inocula (∼106 and ∼108 CFU/ml) using a one-compartment in vitro PK/PD model (19). For colistin-containing regimens, colistin was spiked into the broth reservoir (with the exception of the growth control) prior to the initiation of the experiment so that all media flowing through the system contained colistin at a constant concentration of 0.5, 2, or 5 mg/liter (Table 1) (as colistin is unbound in CAMHB, these represent unbound concentrations). Administration of colistin in this way mimicked the flat plasma concentration-time profiles of formed colistin at steady state that are observed in critically ill patients receiving CMS (36–39). For rifampin-containing regimens, rifampin was injected into each treatment compartment following bacterial inoculation to achieve an unbound steady-state peak concentration (fCmax) of 5 mg/liter, with intermittent dosing every 24 h thereafter (Table 1). The growth medium flow rate and central compartment volume employed allowed simulation of a rifampin elimination half-life (t1/2) of 3 h that mimics the PK of rifampin following a 600-mg intravenous (i.v.) dose administered every 24 hours in patients (40, 41). Due to the short t1/2 relative to the dosing interval, rifampin did not accumulate following such multiple dosing, and therefore, a loading dose was not required (40, 41). Combination regimens contained colistin at all three concentrations mentioned above, with a rifampin fCmax of 5 mg/liter (Table 1). As colistin and rifampin are almost entirely unbound in CAMHB, the specified concentrations represent unbound (free) concentrations.

Table 1.

Colistin and rifampin dosage regimens, PK/PD index values, and sampling times in the in vitro PK/PD modela

| Regimen | Dosage (mg/liter) | PK/PD index (FADDI-AB030 value/FADDI-AB156 value)b |

Sampling times (h) for microbiological measurementsf | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ƒAUC/MIC | ƒCmax/MIC | ƒT>MIC | |||

| Colistin monotherapy target concnc | 0.5 | 24/0.75 | 1.0/0.03 | 100/0 | 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24, 26, 28, 48, 50, 52, 72 |

| 2 | 96/3 | 4.0/0.13 | 100/0 | 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24, 26, 28, 48, 50, 52, 72 | |

| 5 | 240/7.5 | 10.0/0.31 | 100/0 | 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24, 26, 28, 48, 50, 52, 72 | |

| Rifampin monotherapy target Cmaxd | 5 | 0.34/1.35 | 0.078/0.31 | 0/0 | 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24, 26, 28, 48, 50, 52, 72 |

| Combination therapye | 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24, 26, 28, 48, 50, 52, 72 | ||||

Starting inocula of ∼106 and ∼108 CFU/ml.

Values shown are target values for PK/PD indices. For combination therapy, the PK/PD indices for each drug were the same as those for equivalent monotherapy. fAUC/MIC, area under the unbound concentration-time curve over 24 h at the steady state divided by the MIC; ƒCmax/MIC, unbound maximal concentration divided by the MIC; ƒT>MIC, cumulative percentage of a 24-h period that the unbound drug concentration exceeds the MIC under steady-state PK conditions.

Colistin dosage regimens involved a constant concentration of colistin simulating concentrations in critically ill patients (see the text).

The rifampin dosage regimen involved intermittent administration (every 24 h) to achieve the targeted Cmax of 5 mg/liter.

Combination dosage regimens were as follows: colistin at 0.5 mg/liter plus rifampin with a Cmax of 5 mg/liter, colistin at 2 mg/liter plus rifampin with a Cmax of 5 mg/liter, and colistin at 5 mg/liter plus rifampin with a Cmax of 5 mg/liter.

The number of CFU/ml was determined at all time points. Full PAPs were determined at 0 and 72 h, while mini-PAPs were examined at 6, 24, and 48 h.

Microbiological response and emergence of resistance to colistin.

Serial broth samples (0.6 ml) were collected aseptically from each treatment and control compartment at the times shown in Table 1 for viable counting and population analysis profiles (PAPs). After appropriate dilution with sterile saline, samples of bacterial cell suspension (50 μl) were spirally plated on nutrient agar plates (Media Preparation Unit, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia) using an automatic spiral plater (WASP; Don Whitley Scientific, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom). Serial 10-fold dilutions and spiral plating, which further diluted the sample, minimized antibiotic carryover. Colonies were counted by a ProtoCOL automated colony counter (Synbiosis, Cambridge, United Kingdom) after 24 h of incubation at 35°C. The lower limit of counting was 20 CFU/ml (equivalent to 1 colony per plate) and the limit of quantification was 400 CFU/ml (equivalent to 20 colonies per plate), as specified in the ProtoCOL manual. In order to evaluate the development of colistin resistance, real-time PAPs incorporating colistin at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/liter were determined at baseline and at 72 h; mini-PAPs (0, 2, 4, and 8 mg/liter) were determined at 6, 24, and 48 h. Colistin concentrations used for PAPs were chosen after consideration of the MICs and clinically achievable concentrations (36–39).

Pharmacokinetic validation.

Samples (100 μl) collected in duplicate from each compartment of the in vitro PK/PD model were placed in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany) and immediately stored at −80°C until analysis; all samples were assayed within 4 weeks. Concentrations of colistin were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (42) with an assay range for colistin of 0.10 to 6.00 mg/liter. Rifampin concentrations were measured by HPLC. Briefly, to 100 μl of sample, 10 μl of 2-mg/ml ascorbic acid and 220 μl of acetonitrile were added, followed by vortex mixing and centrifugation at 9,300 × g for 10 min. A 50-μl aliquot of the supernatant was injected onto a Phenosphere NEXT 5-μm C18 column (150 mm by 4.6 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) operated at 22°C. The mobile phase consisted of a gradient mixture of 0.1% formic acid in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (mobile phase B). Gradient elution started with an isocratic elution of 70:30 (A/B), followed by a gradual decrease of A to 25:75 (A/B) over 5 min before a return to the initial conditions. The run time was 7 min, and the assay range was 0.5 to 32 mg/liter. Analysis of quality control (QC) samples with nominal concentrations of colistin of 0.40 and 4.0 mg/liter and of rifampin of 0.75, 7.5, and 15 mg/liter demonstrated accuracy (deviations from target concentrations) and precision (coefficients of variation) of <10% for both colistin and rifampin.

Pharmacodynamic analysis.

The microbiological response to monotherapy and combination therapy was examined using the log change method comparing the change in log10 (CFU/ml) from 0 h (CFU0) to time t (6, 24, 48, or 72 h; CFUt) (19) as follows: log change = log10(CFUt) − log10(CFU0) (14, 19). Monotherapy or combination regimens causing a reduction of ≥1 log10 CFU/ml below the initial inoculum at the specified time were considered active. Synergy was defined as ≥2 log10 CFU/ml lower for the combination than for its most active component at the specified time (43); additivity was defined as 1 to <2 log10 CFU/ml lower for the combination.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetic validation and rifampin binding.

The colistin concentrations achieved (means ± standard deviations [SD]) were 0.45 ± 0.05 mg/liter (n = 6), 1.78 ± 0.17 mg/liter (n = 6), and 4.73 ± 0.02 mg/liter (n = 6) for the targeted concentrations of 0.5, 2, and 5 mg/liter, respectively. The measured rifampin Cmax was 5.16 ± 0.55 mg/liter (n = 40) for the targeted value of 5 mg/liter. The observed mean t1/2 for rifampin was 3.13 ± 0.37 h for the targeted value of 3 h. The rifampin ƒu was 0.94, indicating practical equivalence of total and unbound concentrations.

Microbiological response. (i) Monotherapy.

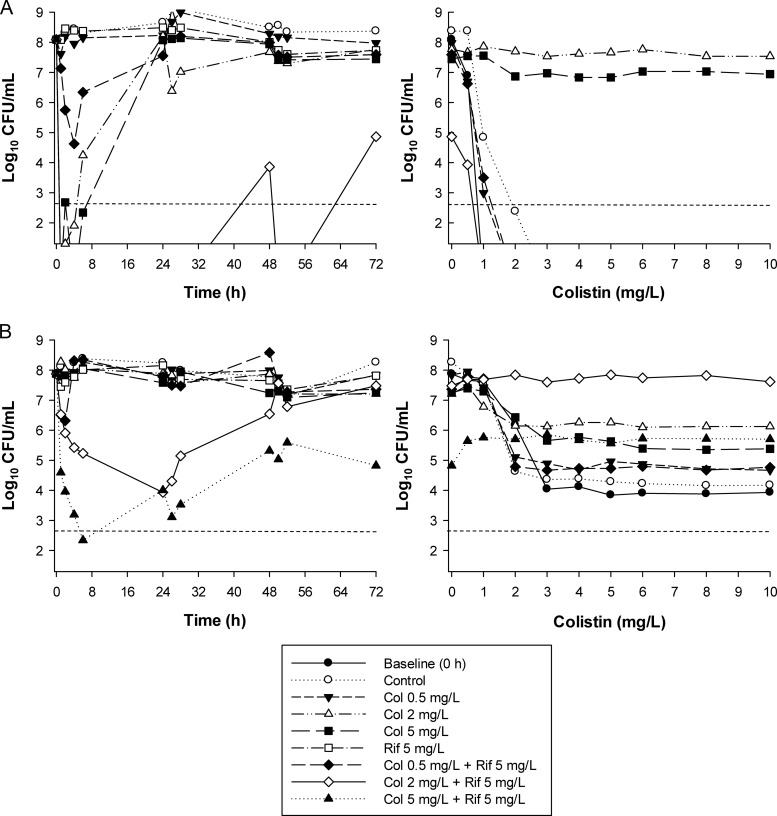

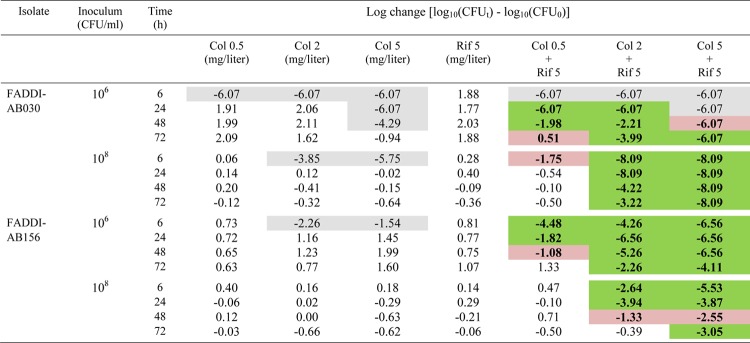

With the colistin-susceptible isolate FADDI-AB030 at the 106-CFU/ml inoculum, colistin monotherapy at all concentrations (0.5, 2, and 5 mg/liter) produced rapid bacterial killing and undetectable bacterial counts within 1 to 2 h after initiation of therapy (Fig. 1A). At the two lower concentrations, regrowth equivalent to control values occurred by 24 h. However, with the 5-mg/liter colistin regimen, regrowth to ∼2 log10 CFU/ml was observed at 48 h, with subsequent regrowth to ∼5 log10 CFU/ml at 72 h. Against the high inoculum (108 CFU/ml), initial bacterial killing by colistin at 0.5 mg/liter was markedly attenuated (<0.5 log10 kill), whereas colistin at 2 or 5 mg/liter resulted in no viable bacteria being detected at 1 h (Fig. 2A). Although no regrowth was observed in the first 6 h with any colistin regimen at the low inoculum, regrowth had commenced by 2 h at the high inoculum with the 2- and 5-mg/liter colistin regimens and had returned very close to control values by 24 h. Against the colistin-resistant isolate FADDI-AB156 at the low inoculum, initial bacterial killing ranged from essentially no effect with the 0.5-mg/liter colistin regimen to ∼3 log10 kill at 2 h, followed by rapid regrowth to control values with the 5-mg/liter regimen (Fig. 1B). In contrast, at the high inoculum, bacterial growth with colistin at all concentrations was similar to that of the control (Fig. 2B). Monotherapy with rifampin produced essentially no bacterial killing against either isolate at both inocula (Fig. 1 and 2).

Fig 1.

(Left) Time-kill curves with various clinically relevant dosage regimens of colistin (Col) and rifampin (Rif) alone and in combination at an inoculum of ∼106 CFU/ml. (Right) PAPs at baseline (0 h) and after 72 h of exposure to colistin monotherapy, colistin-rifampin combination therapy, or neither antibiotic (control). (A) FADDI-AB030 (colistin susceptible, rifampin resistant, MDR); (B) FADDI-AB156 (colistin resistant, rifampin resistant, MDR). The y axis starts from the limit of detection, and the limit of quantification is indicated by the dashed horizontal line.

Fig 2.

(Left) Time-kill curves with various clinically relevant dosage regimens of colistin (Col) and rifampin (Rif) alone and in combination at an inoculum of ∼108 CFU/ml. (Right) PAPs at baseline (0 h) and after 72 h of exposure to colistin monotherapy, colistin-rifampin combination therapy, or neither antibiotic (control). (A) FADDI-AB030 (colistin susceptible, rifampin resistant, MDR); (B) FADDI-AB156 (colistin resistant, rifampin resistant, MDR). The y axis starts from the limit of detection, and the limit of quantification is indicated by the dashed horizontal line.

Combination therapy.

With FADDI-AB030 at the 106-CFU/ml inoculum, the addition of rifampin to all colistin regimens substantially increased bacterial killing and delayed regrowth relative to monotherapy such that no viable bacteria were detected until at least 48 to 72 h. Enhanced bacterial killing was particularly evident for combinations containing the 0.5- or 2-mg/liter colistin regimens, with synergy (predominantly) or additivity produced on all occasions from 24 h onwards (Fig. 1A and Table 2). For example, whereas no viable bacteria were detected with either of the 0.2- and 2-mg/liter colistin combination regimens at 24 h, regrowth to ∼8 log10 CFU/ml had occurred at this time with equivalent colistin monotherapy. Substantial bacterial killing occurred across 48 h with the 5-mg/liter colistin monotherapy regimen; however, the addition of rifampin enhanced bacterial killing across 48 to 72 h by a further ∼2 to 3 log10 CFU/ml and produced synergy even at 72 h (Fig. 1A and Table 2). At the high inoculum, the combination containing 0.5 mg/liter colistin increased initial bacterial killing by ∼3 log10 CFU/ml over colistin monotherapy, although regrowth equivalent to control levels occurred rapidly (commencing at 6 h). However, with the higher colistin concentrations (2 and 5 mg/liter), combination therapy substantially increased bacterial killing across 72 h (by as much as ∼8 log10 CFU/ml) and, in the case of 5 mg/liter colistin plus rifampin, resulted in no viable bacteria being detected following commencement of treatment; synergy was recorded at all time points across 72 h with both regimens.

Table 2.

Log changes at 6, 24, 48, and 72 h at an inoculum of 106 or 108 CFU/ml with colistin and/or rifampin against A. baumanniia

Gray background indicates activity (a reduction of ≥1 log10 CFU/ml below the initial inoculum); green background indicates synergy (a decrease of ≥2 log10 in the number of CFU/ml between the combination and its most active component); red background indicates additivity (a decrease of 1.0 to <2 log10 in the number of CFU/ml between the combination and its most active component).

Remarkably, against the colistin-resistant isolate FADDI-AB156 at the 106-CFU/ml inoculum, all combinations increased initial bacterial killing by ∼2 to 5 log10 CFU/ml. Synergy was maintained across 48 h for the combination containing colistin at 0.5 mg/liter and across 72 h for combinations containing the higher colistin concentrations (Fig. 1B and Table 2). For the latter two combinations, bacterial killing was typically between ∼2.5 and 7.5 log10 CFU/ml greater than that with the equivalent monotherapy at all times, with each combination reducing bacteria to below the limit of detection on at least one occasion (at 24 h with the 2-mg/liter colistin regimen and on multiple occasions with the 5-mg/liter regimen) (Fig. 1B). At the 108-CFU/ml inoculum, the enhancement of bacterial killing by combination therapy was attenuated, although combinations containing the 2- and 5-mg/liter colistin regimens still increased initial bacterial killing (by ∼2 and 5 log10 CFU/ml, respectively). Gradual regrowth occurred with both these combinations, although growth remained ∼1.5 to 2.5 log10 CFU/ml lower than that with the equivalent monotherapy for the 5-mg/liter colistin combination, where synergy or additivity was produced at all times across 72 h.

Resistance emergence.

Real-time PAPs at 72 h show the changes of subpopulations with different colistin susceptibilities that occurred during treatment. Apart from a small shift to the right from 0 to 72 h at the 106-CFU/ml inoculum, the PAPs for the FADDI-AB030 growth control at 72 h closely matched those observed at baseline at both inocula (Fig. 1A and 2A); no colistin-resistant subpopulations (i.e., subpopulations growing in the presence of ≥4 mg/liter colistin) were detected for the growth control for this isolate at any time (data not shown). At the low inoculum, no colistin-resistant subpopulations were detected up to 48 h with any colistin monotherapy regimen (data not shown). However, at 72 h, virtually all colonies (with the 0.5-mg/liter colistin regimen) or a high proportion of colonies (with the 2- and 5-mg/liter colistin regimens) grew in the presence of 10 mg/liter colistin (Fig. 1A). At the high inoculum, colistin-resistant subpopulations emerged by 6 h with the 2- and 5-mg/liter colistin monotherapy regimens (data not shown), and by 72 h, virtually all colonies grew in the presence of 10 mg/liter colistin (Fig. 2A); no colistin-resistant subpopulations were detected at any time at this inoculum with the 0.5-mg/liter colistin monotherapy regimen. Combination therapy against this isolate completely suppressed the emergence of colistin-resistant subpopulations such that at 72 h, no colistin-resistant colonies were detected with any colistin-rifampin combination at either inoculum (Fig. 1A and 2A).

With colistin-resistant isolate FADDI-AB156, the proportion of colistin-resistant subpopulations at baseline increased rapidly at the low inoculum with all colistin monotherapy regimens. By 24 h, virtually all colonies from the 2- and 5-mg/liter colistin regimens grew in the presence of 10 mg/liter colistin (data not shown); by 72 h, a high proportion of colonies from the 0.5-mg/liter regimen grew in the presence of 10 mg/liter colistin (Fig. 1A). At the high inoculum, the proportion of colistin-resistant subpopulations at 72 h was only marginally higher than that at baseline for all colistin monotherapy regimens. While no colistin-resistant colonies were detected from 24 h onwards with combinations containing the 2- or 5-mg/liter colistin regimen at the low inoculum, the 0.5-mg/liter colistin and rifampin regimen at this inoculum and all combinations at the high inoculum did not substantially change the proportion of colistin-resistant subpopulations.

DISCUSSION

Colistin has emerged as a last-line therapy for treatment of severe infections caused by MDR Gram-negative pathogens. At present, the unbound fraction of colistin in human plasma is not fully defined. However, assuming that the plasma binding of colistin in humans is similar to that in experimental animals (i.e., ∼50% bound [44]), the dosage regimens of colistin employed in this study simulated clinically achievable unbound plasma colistin concentrations following i.v. administration of CMS in critically ill patients (36–39); in this patient group, steady-state plasma colistin concentrations average ∼2 to 3 mg/liter (with some patients achieving up to ∼10 mg/liter), and there is only a small degree of fluctuation in the concentration of formed colistin across a CMS dosage interval (36–39). The low plasma colistin concentrations achieved in patients, together with regrowth commonly observed both in vitro (18) and in vivo (12) with colistin monotherapy, highlight a need for caution with the use of CMS monotherapy. Given this situation, colistin combination therapy is now increasingly used (32, 45).

The area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC is the PK/PD index most closely correlated with colistin bacterial killing of A. baumannii (46). In a murine thigh infection model, fAUC/MIC ratios of ∼10 and ∼20 were associated with 1 and 2 log10 killing, respectively, of colistin-susceptible MDR clinical strains of A. baumannii (46). In the present study, the fAUC/MIC for all colistin regimens was >20 against the isolate FADDI-AB030 (colistin susceptible) (Table 1); against the colistin-resistant isolate FADDI-AB156, all regimens had an fAUC/MIC ratio of <10. However, even with an fAUC/MIC ratio of 24 (0.5-mg/liter colistin regimen) or 96 (2-mg/liter colistin regimen), regrowth very close to or above the initial inoculum occurred by 24 h with colistin monotherapy against the colistin-susceptible isolate, even at the low inoculum; only the 5-mg/liter colistin regimen (fAUC/MIC of 96) produced net bacterial killing at this time, and only at the low inoculum (Fig. 1). The rifampin concentration-time profiles in our model simulated those achieved in humans with a commonly used rifampin dosage regimen. In our study, both isolates were rifampin resistant (MIC ≥ 16) with low fAUC/MIC values (≤1.35); rifampin monotherapy produced virtually no bacterial killing. Despite low index values for both colistin (isolate FADDI-AB156) and rifampin (both isolates), bacterial killing was substantially enhanced with the colistin-rifampin combination against both isolates at both inocula (Fig. 1 and 2). For the regimens containing 2 or 5 mg/liter colistin, enhanced killing (>6 log10 CFU/ml on many occasions) was maintained across 72 h in 7 of 8 cases (i.e., 2 combinations across 2 isolates and 2 inocula) (Fig. 1 and 2 and Table 2), including against the colistin-resistant isolate. In line with previous studies employing colistin-susceptible isolates of A. baumannii (13, 18, 47), we observed substantial regrowth with colistin monotherapy at all concentrations. The emergence or amplification of colistin-resistant subpopulations has been shown to contribute to the observed regrowth with colistin monotherapy (13, 18). Considering the PK/PD and potential nephrotoxicity of colistin (37, 48, 49), our data indicate the great potential of an optimized combination of colistin and rifampin against A. baumannii.

Previous studies examining colistin in combination with rifampin against A. baumannii and which utilized static time-kill methods employed MIC-based concentrations rather than clinically relevant free drug concentrations and a single low (≤106-CFU/ml) initial inoculum (24, 26, 28); only one study included colistin-resistant strains (28). These studies were performed over a relatively short period (up to 24 h) and, importantly, did not examine the impact of combination therapies on development of resistance. The present investigation is the first to utilize an in vitro PK/PD model to evaluate the effects on bacterial killing of combinations of colistin and rifampin against A. baumannii, including the effects of combination therapy on the development of colistin resistance, and to examine effects over a longer (72-h) time frame and at both high and low inocula. In addition to the substantially enhanced bacterial killing observed with the colistin-rifampin regimens, combination therapy against the colistin-susceptible isolate completely suppressed the emergence of colistin-resistant subpopulations at both inocula. Importantly, combinations containing the 2- or 5-mg/liter colistin regimen reduced the preexisting colistin-resistant subpopulations of the colistin-resistant isolate to below the limit of detection (i.e., 20 CFU/ml) at the low inoculum. This finding may have major therapeutic implications in that use of colistin-rifampin combination therapy may suppress the emergence of de novo colistin resistance.

One possible mechanism for the enhanced bacterial killing of colistin-rifampin combinations involves the disruption of the bacterial outer membrane by colistin, facilitating penetration of rifampin. Rifampin is a hydrophobic antibiotic which ordinarily does not effectively penetrate the outer membrane in Gram-negative pathogens (50). The elevated rifampin MICs of Gram-negative bacteria appear in general to be attributable to impeded penetration of rifampin through the outer membrane rather than to reduced specific target susceptibility (50). The initial target of colistin against Gram-negative bacteria is lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of the outer membrane, wherein the interaction is initiated by electrostatic attraction between the cationic amine functionalities on colistin and the anionic phosphate and carboxylate functionalities on LPS. This interaction displaces the native divalent cations and results in considerable membrane disruption, increasing the permeability of the outer membrane not only to itself (so-called self-promoted uptake) but also to other compounds (51); this may improve access of rifampin to its target site within the cytoplasm. While this may explain increased activity for the combination against the colistin-susceptible isolate, bacterial killing with the combination was also greatly increased against the colistin-resistant isolate. Colistin-resistant subpopulations of A. baumannii typically show increased susceptibility to antibiotics that are usually ineffective against colistin-susceptible strains (52). This may be due to the substantial changes to the outer membrane of A. baumannii associated with the development of colistin resistance (53, 54) that facilitate access of these antibiotics to their intracellular target sites.

In summary, we have shown for the first time that the combination of colistin and rifampin, with dosage regimens that achieve clinically relevant concentrations, substantially increased killing of both MDR colistin-susceptible and -resistant A. baumannii and that combination therapy prevented or suppressed the emergence of colistin-resistant subpopulations. Clinical studies are warranted to optimize colistin-rifampin combination therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; grant numbers R01AI079330 and R01AI070896 to R.L.N. and J.L.). R.L.N. and J.L. are supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

The content is the responsibility of solely the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

J.L. is an Australian NHMRC Senior Research Fellow. J.B.B. is an ARC DECRA Fellow (DE120103084).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. 2009. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Talbot GH, Bradley J, Edwards JE, Jr, Gilbert D, Scheld M, Bartlett JG. 2006. Bad bugs need drugs: an update on the development pipeline from the Antimicrobial Availability Task Force of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:657–668 (Erratum, 42:1065) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2010. The 10 × '20 initiative: pursuing a global commitment to develop 10 new antibacterial drugs by 2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1081–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spellberg B, Blaser M, Guidos RJ, Boucher HW, Bradley JS, Eisenstein BI, Gerding D, Lynfield R, Reller LB, Rex J, Schwartz D, Septimus E, Tenover FC, Gilbert DN. 2011. Combating antimicrobial resistance: policy recommendations to save lives. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52(Suppl 5):S397–S428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:538–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peleg AY, Hooper DC. 2010. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N. Engl. J. Med. 362:1804–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. 2005. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1333–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL. 2006. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6:589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michalopoulos AS, Karatza DC. 2010. Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections: the use of colistin. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 8:1009–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ko KS, Suh JY, Kwon KT, Jung SI, Park KH, Kang CI, Chung DR, Peck KR, Song JH. 2007. High rates of resistance to colistin and polymyxin B in subgroups of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Korea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:1163–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park YK, Jung SI, Park KH, Cheong HS, Peck KR, Song JH, Ko KS. 2009. Independent emergence of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter spp. isolates from Korea. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 64:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodriguez CH, Bombicino K, Granados G, Nastro M, Vay C, Famiglietti A. 2009. Selection of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in postneurosurgical meningitis in an intensive care unit with high presence of heteroresistance to colistin. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 65:188–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li J, Rayner CR, Nation RL, Owen RJ, Spelman D, Tan KE, Liolios L. 2006. Heteroresistance to colistin in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2946–2950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bergen PJ, Forrest A, Bulitta JB, Tsuji BT, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL, Li J, Nation RL. 2011. Clinically relevant plasma concentrations of colistin in combination with imipenem enhance pharmacodynamic activity against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa at multiple inocula. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5134–5142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meletis G, Tzampaz E, Sianou E, Tzavaras I, Sofianou D. 2011. Colistin heteroresistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:946–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poudyal A, Howden BP, Bell JM, Gao W, Owen RJ, Turnidge JD, Nation RL, Li J. 2008. In vitro pharmacodynamics of colistin against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1311–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yau W, Owen RJ, Poudyal A, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, Yu HH, Nation RL, Li J. 2009. Colistin hetero-resistance in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates from the Western Pacific region in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance programme. J. Infect. 58:138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tan CH, Li J, Nation RL. 2007. Activity of colistin against heteroresistant Acinetobacter baumannii and emergence of resistance in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3413–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bergen PJ, Tsuji BT, Bulitta JB, Forrest A, Jacob J, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL, Nation RL, Li J. 2011. Synergistic killing of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa at multiple inocula by colistin combined with doripenem in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5685–5695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hawley JS, Murray CK, Jorgensen JH. 2008. Colistin heteroresistance in acinetobacter and its association with previous colistin therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:351–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aydemir H, Akduman D, Piskin N, Comert F, Horuz E, Terzi A, Kokturk F, Ornek T, Celebi G. 2013. Colistin vs. the combination of colistin and rifampicin for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia. Epidemiol. Infect. 141:1214–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsioutis C, Kritsotakis EI, Maraki S, Gikas A. 2010. Infections by pandrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: clinical profile, therapeutic management, and outcome in a series of 21 patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:301–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI, Matthaiou DK, Virtzili S, Nikita D, Michalopoulos A. 2008. Pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii infections: characteristics and outcome in a series of 28 patients. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 32:450–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Xirouchaki E, Giamarellou H. 2001. Interactions of colistin and rifampin on multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 40:117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hogg GM, Barr JG, Webb CH. 1998. In-vitro activity of the combination of colistin and rifampicin against multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:494–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liang W, Liu XF, Huang J, Zhu DM, Li J, Zhang J. 2011. Activities of colistin- and minocycline-based combinations against extensive drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from intensive care unit patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 11:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Montero A, Ariza J, Corbella X, Domenech A, Cabellos C, Ayats J, Tubau F, Borraz C, Gudiol F. 2004. Antibiotic combinations for serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a mouse pneumonia model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:1085–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peck KR, Kim MJ, Choi JY, Kim HS, Kang CI, Cho YK, Park DW, Lee HJ, Lee MS, Ko KS. 2012. In vitro time-kill studies of antimicrobial agents against blood isolates of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, including colistin- or tigecycline-resistant isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 61:353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tripodi MF, Durante-Mangoni E, Fortunato R, Utili R, Zarrilli R. 2007. Comparative activities of colistin, rifampicin, imipenem and sulbactam/ampicillin alone or in combination against epidemic multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates producing OXA-58 carbapenemases. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:537–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pachon-Ibanez ME, Docobo-Perez F, Lopez-Rojas R, Dominguez-Herrera J, Jimenez-Mejias ME, Garcia-Curiel A, Pichardo C, Jimenez L, Pachon J. 2010. Efficacy of rifampin and its combinations with imipenem, sulbactam, and colistin in experimental models of infection caused by imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1165–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pantopoulou A, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Raftogannis M, Tsaganos T, Dontas I, Koutoukas P, Baziaka F, Giamarellou H, Perrea D. 2007. Colistin offers prolonged survival in experimental infection by multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: the significance of co-administration of rifampicin. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29:51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petrosillo N, Ioannidou E, Falagas ME. 2008. Colistin monotherapy vs. combination therapy: evidence from microbiological, animal and clinical studies. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:816–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 20th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S20. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bergen PJ, Li J, Rayner CR, Nation RL. 2006. Colistin methanesulfonate is an inactive prodrug of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1953–1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bergen PJ, Bulitta JB, Forrest A, Tsuji BT, Li J, Nation RL. 2010. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic investigation of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa using an in vitro model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3783–3789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mohamed AF, Karaiskos I, Plachouras D, Karvanen M, Pontikis K, Jansson B, Papadomichelakis E, Antoniadou A, Giamarellou H, Armaganidis A, Cars O, Friberg LE. 2012. Application of a loading dose of colistin methanesulfonate in critically ill patients: population pharmacokinetics, protein binding, and prediction of bacterial kill. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4241–4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V, Paterson DL, Shoham S, Jacob J, Silveira FP, Forrest A, Nation RL. 2011. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3284–3294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Markou N, Markantonis SL, Dimitrakis E, Panidis D, Boutzouka E, Karatzas S, Rafailidis P, Apostolakos H, Baltopoulos G. 2008. Colistin serum concentrations after intravenous administration in critically ill patients with serious multidrug-resistant, gram-negative bacilli infections: a prospective, open-label, uncontrolled study. Clin. Ther. 30:143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Plachouras D, Karvanen M, Friberg LE, Papadomichelakis E, Antoniadou A, Tsangaris I, Karaiskos I, Poulakou G, Kontopidou F, Armaganidis A, Cars O, Giamarellou H. 2009. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of colistin methanesulphonate and colistin after intravenous administration in critically ill patients with gram-negative bacterial infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3430–3436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Loos U, Musch E, Jensen JC, Mikus G, Schwabe HK, Eichelbaum M. 1985. Pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous rifampicin during chronic administration. Klin. Wochenschr. 63:1205–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruslami R, Nijland HM, Alisjahbana B, Parwati I, van Crevel R, Aarnoutse RE. 2007. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of a higher rifampin dose versus the standard dose in pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2546–2551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Coulthard K. 2003. Stability of colistin and colistin methanesulfonate in aqueous media and plasma as determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1364–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pillai SK, Moellering RC, Eliopoulos GM. 2005. Antimicrobial combinations, p 365–440 In Lorian V. (ed), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 5th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K. 2003. Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1766–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kasiakou SK, Michalopoulos A, Soteriades ES, Samonis G, Sermaides GJ, Falagas ME. 2005. Combination therapy with intravenous colistin for management of infections due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in patients without cystic fibrosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3136–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dudhani RV, Turnidge JD, Nation RL, Li J. 2010. fAUC/MIC is the most predictive pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic index of colistin against Acinetobacter baumannii in murine thigh and lung infection models. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1984–1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Owen RJ, Li J, Nation RL, Spelman D. 2007. In vitro pharmacodynamics of colistin against Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:473–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hartzell JD, Neff R, Ake J, Howard R, Olson S, Paolino K, Vishnepolsky M, Weintrob A, Wortmann G. 2009. Nephrotoxicity associated with intravenous colistin (colistimethate sodium) treatment at a tertiary care medical center. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1724–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kwon JA, Lee JE, Huh W, Peck KR, Kim YG, Kim DJ, Oh HY. 2010. Predictors of acute kidney injury associated with intravenous colistin treatment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:473–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wehrli W. 1983. Rifampin: mechanisms of action and resistance. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5(Suppl 3):S407–S411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hancock RE, Chapple DS. 1999. Peptide antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1317–1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li J, Nation RL, Owen RJ, Wong S, Spelman D, Franklin C. 2007. Antibiograms of multidrug-resistant clinical Acinetobacter baumannii: promising therapeutic options for treatment of infection with colistin-resistant strains. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:594–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Henry R, Vithanage N, Harrison P, Seemann T, Coutts S, Moffatt JH, Nation RL, Li J, Harper M, Adler B, Boyce JD. 2012. Colistin-resistant, lipopolysaccharide-deficient Acinetobacter baumannii responds to lipopolysaccharide loss through increased expression of genes involved in the synthesis and transport of lipoproteins, phospholipids, and poly-β-1,6-N-acetylglucosamine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:59–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moffatt JH, Harper M, Harrison P, Hale JD, Vinogradov E, Seemann T, Henry R, Crane B, St Michael F, Cox AD, Adler B, Nation RL, Li J, Boyce JD. 2010. Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by complete loss of lipopolysaccharide production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4971–4977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]