Abstract

The efficacies of many antimicrobial peptides are greatly reduced under high salt concentrations, therefore limiting their use as pharmaceutical agents. Here, we describe a strategy to boost salt resistance and serum stability of short antimicrobial peptides by adding the nonnatural bulky amino acid β-naphthylalanine to their termini. The activities of the short salt-sensitive tryptophan-rich peptide S1 were diminished at high salt concentrations, whereas the activities of its β-naphthylalanine end-tagged variants were less affected.

TEXT

Antimicrobial peptides have been found to play important roles in the host defense (1). Most of the antimicrobial peptides are polycationic, amphipathic, and generally interact and permeabilize microbial membranes (1). Development of antimicrobial peptides as therapeutic agents could be promising due to their special microbicidal mechanism (2).

Development of antimicrobial peptides has been hindered by several problems, such as salt sensitivity, cost of synthesis, bioavailability, and stability. Salt sensitivity is directly related to the antimicrobial peptide's microbicidal mechanism. The efficacy of human β-defensin-1 is greatly reduced in the high-salt bronchopulmonary fluids in cystic fibrosis patients (3). Similar problems were observed for the clinically active peptide P-113, indolicidins, gramicidins, bactenecins, and magainins (4–7). Studies have been reported on the design of salt-resistant antimicrobial peptides. However, most of them were focused on overall structure modifications (4, 8–13).

Previously, we developed an easy strategy to increase salt resistance of Trp- and His-rich antimicrobial peptides by replacing their tryptophans or histidines with the bulky amino acid β-naphthylalanine (14). This strategy has been applied successfully to the Trp-rich peptide Pac-525 (Ac-KWRRWVRWI-NH2) and the clinically active His-rich peptide P-113 (AKRHHGYKRKFH-NH2).

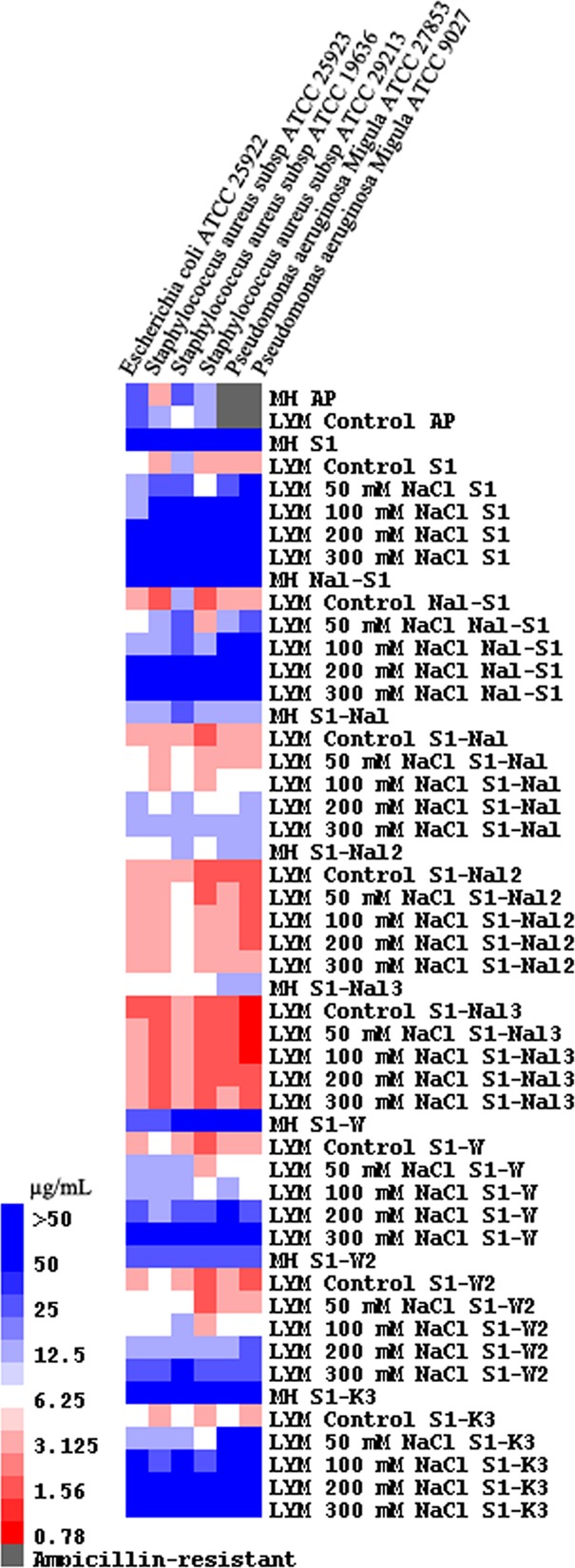

A short Trp-rich antimicrobial peptide, S1 (Ac-KKWRKWLAKK-NH2), was designed based on studies of PEM-2-W5K/A9W (Ac-KKWRKWLKWLAKK-NH2) (15). PEM-2-W5K/A9W was found to be very effective against both bacteria and fungi under high-salt conditions (15). S1 demonstrates promising antimicrobial activities in the low-salt LYM broth medium (Fig. 1). However, the antimicrobial activities of S1 were diminished at high salt concentrations (Fig. 1). Replacement of tryptophan residues of S1 with β-naphthylalanine may generate a potent peptide (Nal-S1) with improved antimicrobial activity and salt resistance. Unfortunately, Nal-S1 does not have the expected salt resistance.

Fig 1.

MIC values displayed on a color scale for ampicillin (AP), S1, Nal-S1, S1-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal-Nal, S1-W, S1-WW, and S1-KKK with different concentrations of NaCl.

Recently, Malmsten and coworkers developed a strategy to boost activities of short antimicrobial peptides by modulating their lipophilicity with the addition of tryptophan and/or phenylalanine end tags (16–18). The addition of fatty acid, vitamin E, or cholesterol to the termini of antimicrobial peptides has been shown to have similar results (19–23). It is thus hypothesized that addition of the bulky amino acid β-naphthylalanine to the termini of short antimicrobial peptides may improve their antimicrobial activity and salt resistance.

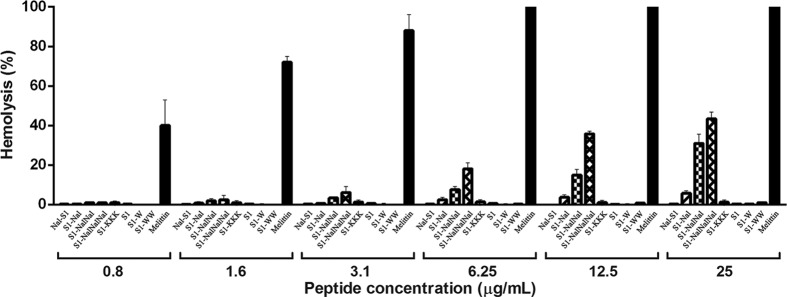

We designed and synthesized S1, Nal-S1, S1-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal-Nal, S1-W, S1-WW, and S1-KKK. The tryptophan end-tagged S1-W and S1-WW and lysine end-tagged S1-KKK were used for comparisons. Bacterial strains from ATCC are listed in Fig. 1. Antibacterial activities were determined by the standard broth microdilution method of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of peptide at which there was no change in optical density. MICs were converted to a color scale and displayed using the TreeView program (19, 24). The serum stability of the peptides was determined in 25% (vol/vol) aqueous bovine calf serum (catalog number AUE-34962; HyClone). Peptides were dissolved in serum at a concentration of 150 μg/ml and incubated at 37°C. After 45 min on ice to precipitate serum proteins, the samples were centrifuged (10 min, 12,000 × g, 4°C) and the supernatants were lyophilized. The remaining amount of the peptides was determined by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. All MIC and serum stability tests were performed in triplicate. Toxicities of the peptides were determined from lysis of human red blood cells (hRBC) (Fig. 2) and human fibroblast cells (25). Although S1-Nal-Nal and S1-Nal-Nal-Nal had higher cell lytic activities than the other peptides, all of the peptides exhibited <5% cell lytic activity at their effective MIC.

Fig 2.

Hemolytic assay results for S1, Nal-S1, S1-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal-Nal, S1-W, S1-WW, and S1-KKK. Melittin (black bar) was used as a control. The antibacterial activities of S1, Nal-S1, S1-W, S1-WW, and S1-KKK were reduced (MICs, >25 μg/ml) under the salt concentration used in the hemolytic assay, whereas S1-Nal (MIC, ∼6.25 μg/ml), S1-Nal-Nal (MIC, ∼3.1 μg/ml), and S1-Nal-Nal-Nal (MIC, ∼1.6 μg/ml) still retained antibacterial activities.

All of the peptides studied demonstrated promising activities in the LYM broth medium (Fig. 1). However, the activities of S1, Nal-S1, S1-W, S1-WW, and S1-KKK were reduced or diminished in Mueller-Hinton broth or under high-salt conditions. The MICs of S1-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal, and S1-Nal-Nal-Nal were found to be more potent than S1 in both Mueller-Hinton and modified LYM broth medium. S1-Nal-Nal and S1-Nal-Nal-Nal still retained their antibacterial activities with 300 mM NaCl added. The N-terminal-tagged variant had similar MICs and hemolytic activities as the C-terminal-tagged S1-Nal-Nal. Results from fluorescence quenching experiments indicated that β-naphthylalanine end tagging may help these peptides penetrate deeper into the membranes, hence making them more efficient at disrupting the membranes.

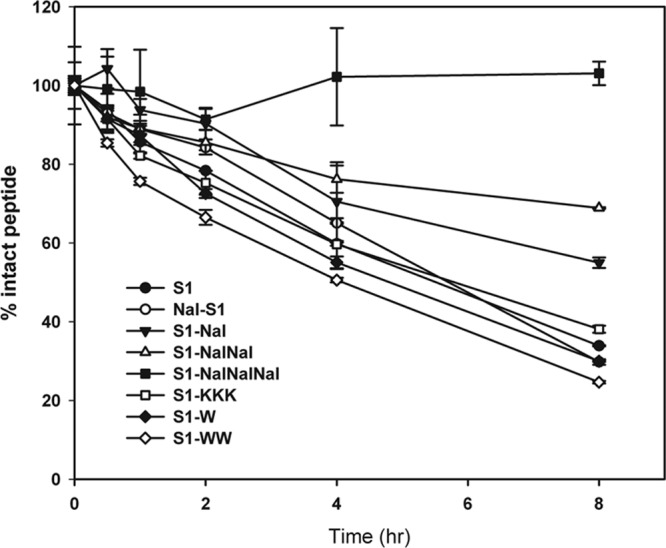

Additionally, β-naphthylalanine end tagging was found to protect S1 from degradation in serum. S1-Nal-Nal-Nal retained almost 100% of its integrity after 8 h in bovine calf serum (Fig. 3). The degrees of protection of these peptides from degradation in bovine calf serum were found to be S1-Nal-Nal-Nal > S1-Nal-Nal > S1-Nal > S1-KKK > S1 > Nal-S1 = S1-W > S1-WW.

Fig 3.

Serum stability results for S1, Nal-S1, S1-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal, S1-Nal-Nal-Nal, S1-W, S1-WW, and S1-KKK.

There are several advantages of using β-naphthylalanine rather than tryptophan as end tags. Five tryptophan end tags were needed to provide salt resistance to the antimicrobial peptide KNK10 in 150 mM NaCl (17). Only one β-naphthylalanine end tag was needed to provide substantial salt resistance in the present study. This is particularly important for design and development of short antimicrobial peptides for clinical use and to lower the cost of synthesis. Furthermore, β-naphthylalanine end tagging provides superior serum stability compared to tryptophan end tagging, probably because of its nonnatural and bulky characteristics.

Tryptophan or β-naphthylalanine end tagging can also be complementary. The advantage of tryptophan end tagging is the relatively low hemolytic activity compared to β-naphthylalanine end tagging. However, β-naphthylalanine end tagging demonstrates better salt resistance and serum stability. A peptide could be generated to have both tryptophan and β-naphthylalanine end tags. This peptide might exhibit lower hemolytic activity and still possess salt resistance and serum stability.

In addition to S1, we studied β-naphthylalanine end tagging on an ultrashort peptide, KWWK. The ultrashort peptide KWWK-Nal-Nal has a MIC of 1.6 μg/ml at 100 mM NaCl, while its parent peptide, KWWK, has no antimicrobial activity.

Here, we have described a strategy to boost salt resistance and serum stability of short antimicrobial peptides by adding β-naphthylalanine to their termini. This strategy has been applied successfully to S1 and the ultrashort peptide KWWK. We have also added S1-Nal and S1-Nal-Nal into a mouthwash solution formulation and tested their antiplaque and antigingivitis effects. We have not noticed any adverse results. In vivo tests of efficacy and toxicity of these modified peptides are ongoing in our laboratory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by grants from the National Science Council, Taiwan. Bak-Sau Yip was supported by a research grant from National Taiwan University Hospital Hsinchu Branch.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Zasloff M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hancock REW, Sahl HG. 2006. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:1551–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldman MJ, Anderson GM, Stolzenberg ED, Kari UP, Zasloff M, Wilson JM. 1997. Human β-defensin-1 is a salt-sensitive antibiotic in lung that is inactivated in cystic fibrosis. Cell 88:553–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee IH, Cho Y, Lehrer RI. 1997. Effects of pH and salinity on the antimicrobial properties of clavanins. Infect. Immun. 65:2898–2903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rothstein DM, Spacciapoli P, Tran LT, Xu T, Roberts FD, Dalla Serra M, Buxton DK, Oppenheim FG, Friden P. 2001. Anticandida activity is retained in P-113, a 12-amino-acid fragment of histatin 5. Antimcrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1367–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang CW, Yip BS, Cheng HT, Wang AH, Chen HL, Cheng JW, Lo HJ. 2009. Increased potency of a novel D-β-naphthylalanine-substituted antimicrobial peptide against fluconazole-resistant fungal pathogens. FEMS Yeast Res. 9:967–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu M, Maier E, Benz R, Hancock REW. 1999. Mechanism of interaction of different classes of cationic antimicrobial peptides with planar bilayers and with the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 38:7235–7242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deslousches B, Phadke SM, Lazarevic V, Cascio M, Islam K, Montelaro RC, Mietzner TA. 2005. De novo generation of cationic antimicrobial peptides: influence of length and tryptophan substitution on antimicrobial activity. Antimcrob. Agents Chemother. 49:316–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Friedrich C, Scott MG, Karunaratne N, Yan H, Hancock REW. 1999. Salt-resistant alpha-helical cationic antimicrobial peptides. Antimcrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1542–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harwig SSL, Waring A, Yang HJ, Cho Y, Tan L, Lehrer RI. 1996. Intramolecular disulfide bonds enhance the antimicrobial and lytic activities of protegrins at physiological sodium chloride concentrations. Eur. J. Biochem. 240:352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park IY, Cho JH, Kim KS, Kim YB, Kim MS, Kim SC. 2004. Helix stability confers salt resistance upon helical antimicrobial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 279:13896–13901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rydlo T, Rotem S, Mor A. 2006. Antibacterial properties of dermaseptin S4 derivatives under extreme incubation conditions. Antimcrob. Agents Chemother. 50:490–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tam JP, Lu YA, Yang JL. 2000. Design of salt-insensitive glycine-rich antimicrobial peptides with cyclic tricystine structures. Biochemistry 39:7159–7169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu HY, Tu CH, Yip BS, Chen HL, Cheng HT, Huang KC, Lo HJ, Cheng JW. 2011. Easy strategy to increase salt resistance of antimicrobial peptides. Antimcrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4918–4921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu HY, Huang KC, Yip BS, Chen HTCHL, Cheng HT, Cheng JW. 2010. Rational design of tryptophan-rich antimicrobial peptides with enhanced antimicrobial activities and specificities. Chembiochem 11:2273–2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pasupuleti M, Chalupka A, Morgelin M, Schmidtchen A, Malmsten M. 2009. Tryptophan end-tagging of antimicrobial peptides for increased potency against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790:800–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pasupuleti M, Schmidtchen A, Chalupka A, Ringstad L, Malmsten M. 2009. End-tagging of ultra-short antimicrobial peptides by W/F stretches to facilitate bacterial killing. PLoS One 4:e5285. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidtchen A, Pasupuleti M, Morgelin M, Davoudi M, Alenfall J, Chalupka A, Malmsten M. 2009. Boosting antimicrobial peptides by hydrophobic oligopeptide end tags. J. Biol. Chem. 284:17584–17594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arnusch CJ, Ulm H, Josten M, Shadkchan Y, Osherov N, Sahl HG, Shai Y. 2012. Ultrashort peptide bioconjugates are exclusively antifungal agents and synergize with cyclodextrin and amphotericin B. Antimcrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Avrahami D, Shai Y. 2002. Conjugation of a magainin analogue with lipophilic acids controls hydrophobicity, solution assembly, and cell selectivity. Biochemistry 41:2254–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Makovitzki A, Avrahami D, Shai Y. 2006. Ultrashort antibacterial and antifungal lipopeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15997–16002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenfeld Y, Lev N, Shai Y. 2010. Effect of the hydrophobicity to net positive charge ratio on antibacterial and anti-endotoxin activities of structurally similar antimicrobial peptides. Biochemistry 49:853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Serrano GN, Zhanel GG, Schweizer F. 2009. Antibacterial activity of ultrashort cationic lipo-β-peptides. Antimcrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2215–2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:14863–14868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wei SY, Wu JM, Kuo YY, Chen HL, Yip BS, Tzeng SR, Cheng JW. 2006. Solution structure of a novel tryptophan-rich peptide with bidirectional antimicrobial activity. J. Bacteriol. 188:328–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]