Abstract

Baculovirus VP1054 protein is a structural component of both of the virion types budded virus (BV) and occlusion-derived virus (ODV), but its exact role in virion morphogenesis is poorly defined. In this paper, we reveal sequence and functional similarity between the baculovirus protein VP1054 and the cellular purine-rich element binding protein PUR-alpha (PURα). The data strongly suggest that gene transfer has occurred from a host to an ancestral baculovirus. Deletion of the Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) vp1054 gene completely prevented viral cell-to-cell spread. Electron microscopy data showed that assembly of progeny nucleocapsids is dramatically reduced in the absence of VP1054. More precisely, VP1054 is required for proper viral DNA encapsidation, as deduced from the formation of numerous electron-lucent capsid-like tubules. Complementary searching identified the presence of genetic elements composed of repeated GGN trinucleotide motifs in baculovirus genomes, the target sequence for PURα proteins. Interestingly, these GGN-rich sequences are disproportionally distributed in baculoviral genomes and mostly occurred in proximity to the gene for the major occlusion body protein polyhedrin. We further demonstrate that the VP1054 protein specifically recognizes these GGN-rich islands, which at the same time encode crucial proline-rich domains in p78/83, an essential gene adjacent to the polyhedrin gene in the AcMNPV genome. While some viruses, like human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and human JC virus (JCV), utilize host PURα protein, baculoviruses encode the PURα-like protein VP1054, which is crucial for viral progeny production.

INTRODUCTION

Baculoviruses constitute a group of insect-infecting, enveloped viruses with a circular double-stranded DNA genome loaded in a rod-shaped nucleocapsid. They replicate their DNA in the nuclei of infected cells, where also progeny nucleocapsids are assembled. A typical baculovirus infection includes the production of two virion types: (i) extracellular budded virus (BV) formed from nucleocapsids leaving the cell nucleus and budding through the plasma membrane and (ii) occlusion-derived virus (ODV) assembled from nucleocapsids accumulated in the nuclear periphery, where envelopment occurs prior to embedding into viral occlusion bodies (OBs) (see references 1 and 2 for a review). BVs are responsible for the spread of infection within the bodies of insect larvae, while ODVs encapsulated in OBs mediate horizontal virus transmission between insects via oral infection.

The nucleocapsid assembly mechanism used by baculoviruses such as Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) is poorly understood. The most abundant component of the nucleocapsids, which are typically 40 by 250 to 300 nm (3), is the VP39 protein (4, 5). VP39 monomers assemble in the nuclei of infected cells into oligomeric ring-like structures, which are further folded into capsid tubules, likely with the help of the host actin cytoskeleton (6, 7). These preformed capsid tubules are tethered to the virogenic stroma (VS) (8), the viral replication factory, where viral DNA is synthesized and processed for packaging (9, 10). Baculovirus capsids are polar, showing a base on one end and an apical cap on the other end. During nucleocapsid loading, the apical cap is oriented toward the reticulate matrix of the virogenic stroma and likely serves as a portal for loading of the viral genome (8).

Little is known about protein-DNA interactions that determine which DNA will be encapsidated from a mixture of viral and host DNA molecules present in nuclei of virus-infected cells. Unlike for other DNA viruses (11–14), in which encapsidation signal sequences were identified, the nature of analogous signals in baculovirus DNA genomes remains enigmatic. In addition to the above-mentioned VP39, there are a number of minor, but functionally important, capsid-associated proteins (see references 1, 2, and 15 for reviews), which may play essential roles in both recognition of target DNA and its packaging. Among these capsid-associated proteins are two end-linked proteins, very late factor 1 (VLF-1) (16) and VP80 (17, 18), which exhibit DNA-binding activities. VLF-1 is a site-specific recombinase and is likely implicated in postreplication processing of viral DNA preceding its packaging (16). On the other hand, the coupling of the DNA-binding function of VP80 to virus morphogenesis has not been established yet. VP80 contains an atypical basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) DNA-binding domain at its essential C-terminal end (18) and N-terminally located paramyosin-like motifs, likely responsible for the experimentally shown association of VP80 with host nuclear filamentous actin (F-actin) (17). Furthermore, VP80 has been previously shown to interact with 38K, another nucleocapsid-associated protein (19). Hence, it is quite possible that 38K and VP80, together with another 38K interaction partner, such as the structural protein VP1054 (19), may form or are part of a machinery that drives viral DNA encapsidation.

In the current study, we performed functional analysis of the AcMNPV VP1054 protein. Deletion analysis was performed to show the requirement of VP1054 for proper viral DNA encapsidation. In addition, our studies reveal resemblance between VP1054 and the cellular purine-rich-element-binding protein PUR-alpha (PURα), a DNA- and RNA-binding protein with specificity for GGN repeats (20). Genetic elements composed of repeated GGN trinucleotide motifs were identified in baculovirus genomes, and subsequently, the binding of AcMNPV VP1054 protein to these elements was tested. Together, our data provide evidence that VP1054 is a functional, virally encoded PURα-like protein, which is essential for nucleocapsid assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells (Invitrogen) were maintained in SF900-II serum-free medium (Invitrogen) at 27°C under standard conditions. All AcMNPV recombinant bacmids and viruses were derived from the commercially available bacmid bMON14272 (20), which was propagated and engineered in Escherichia coli strain DH10β. The bMON14272 bacmid carrying an expression cassette with an egfp reporter gene under p10 promoter control inserted in the polh locus was used as a positive control and is designated Ac-wt (21) in this report. An Ac-Δgp64 bacmid (22) carrying the same egfp reporter downstream of the p10 promoter, and with a deletion of gp64, the BV fusion protein gene, served as a negative control, representing a virus mutant lacking the ability of cell-to-cell spread.

Construction of an AcMNPV vp1054 knockout.

An AcMNPV bacmid with a deletion of the vp1054 open reading frame (ORF) was derived from bMON14272 (20) via lambda Red recombination in E. coli by a strategy similar to that previously reported (21). Since the vp1054 ORF overlaps the essential lef-10 ORF, only a 955-bp-long sequence of the 3′ end of the ORF was removed (Fig. 1). To prevent translation of the resulting C-truncated VP1054 mutant in insect cells, the first translation codon, ATG (Met), was simultaneously mutated to ACG. This single nucleotide substitution also changed internal codon no. 32 (AAT) of the lef-10 ORF to AAC; however, both encode the same amino acid (Asn) as schematically depicted in Fig. 1. To accomplish this, the 5′ end of the vp1054 ORF was amplified using primers vp1054-ko-F and vp1054-ko-R1 (Table 1) from bacmid bMON14272 (Invitrogen). The 214-bp PCR product contained a 49-bp sequence homologous to the 5′ end of the vp1054 ORF preceded by a mutated vp1054 ATG start codon and had at the 3′ end homology to the chloramphenical acetyltransferase (cat) cassette of plasmid pCRTopo-lox-cat-lox (a gift from L. Galibért, Généthon, France). The 214-bp fragment was subsequently used as a forward primer in a second PCR with reverse primer vp1054-ko-R2 (Table 1) using pCRTopo-lox-cat-lox as the template. The resulting 1,230-bp PCR product, which contained the cat gene flanked by mutant loxP sites (23) and vp1054 sequences, was used for homologous recombination in E. coli cells containing bMON14272 (20) and plasmid pKD46 (24). Chloramphenicol-resistant clones were checked for deletion of the vp1054 ORF by PCR with primers 45510 and 46235 (Table 1) and for the insertion of the cat cassette with primers cat-F and cat-R (21). In the last step, the cat gene was eliminated from the bacmid by cre-based recombination as recently described (21). The elimination of the cat cassette was verified by PCR with primers 45122 and 46441 (Table 1), and a final confirmation was obtained by DNA sequencing. To facilitate monitoring of viral replication in cell culture, a cassette carrying an egfp reporter gene under p10 promoter control (21) was introduced by following the Bac-to-Bac protocol (Invitrogen) to obtain the deletion bacmid designated Ac-Δvp1054.

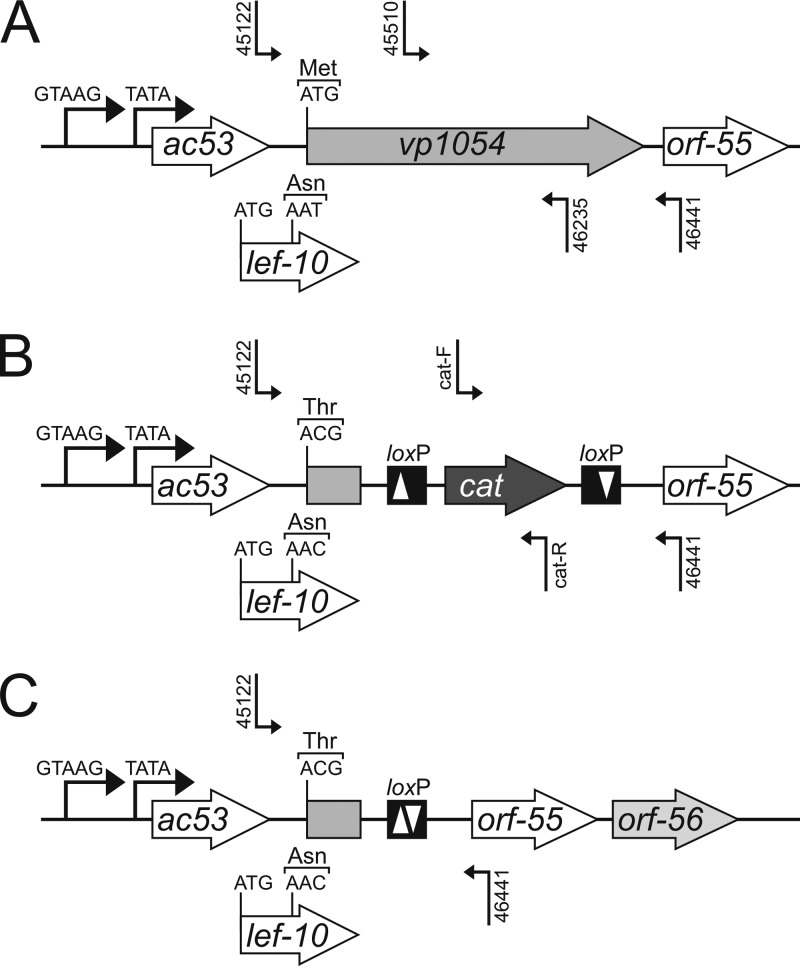

Fig 1.

Overview of the construction of an AcMNPV-Δvp1054 genome containing a major deletion in the vp1054 ORF. (A and B) Using homologous recombination in E. coli, a 955-bp sequence from the 3′ end of the vp1054 ORF was replaced with an antibiotic resistance cassette (cat) flanked by loxP sites. At the same time, a single point mutation was introduced to change the first translation codon ATG (Met) to ACG, to prevent translation into a C-terminally truncated VP1054 protein. (C) Finally, the cat cassette was eliminated from the bacmid sequence using the Cre/loxP recombination system. Locations of primer pairs used in PCR analyses are indicated by unilateral broken arrows.

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR amplifications in this study

| Name | Sensea | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| vp1054-ko-F | F | GTACTGAAAGATAATTTATTTTTGATAGATAATAATTACATTATTTTAAACGTGTTCGACCAAGAAACCGAT |

| vp1054-ko-R1 | R | AGGGCGAATTCCAGCACACTTTATTACGTGGACGCGTTACTTTGC |

| vp1054-ko-R2 | R | GATAAGAATGCTTGTTTAACAAATAGGTCAGCTGTTAAATACTGGCGATGTACCGTTCGTATAGCATACAT |

| 45122 | F | GCAATCATGACGAACGTATGG |

| 46441 | R | CGATAATTTTTCCAAGCGCTAC |

| 45510 | F | ACAGCGTGTACGAGTGCAT |

| 46235 | R | ATCTCGAGCGTGTAGCTGGT |

| vp1054-Rep-F | F | GGTTGTTTAGGCCTGAGCTCCTTTGGTACGTGTTAGAGTGT |

| vp1054-Rep-R | R | TCCTTTCCTCTAGATTACACGTTGTGTGCGTGCAGA |

| lef-10-R | R | TCCTTTCCTCTAGATTACGTGGACGCGTTACTTTGC |

| flag-vp1054-F | F | GGTTGTTTAGGCCTGAGCTCAATATGGATTACAAGGATGACGACGATAAGTGTTCGACCAAGAAACCGAT |

| vp1054-E-F | F | GGATATCCATATGTGTTCGACCAAGAAACCG |

| vp1054-E-R | R | CGCGGATCCCTACACGTTGTGTGCGTGCA |

| GGN-F | F | GGCGGTGGTAACATTTCAGAC |

| GGN-R | R | CCGCCGTCTGCATCACCG |

| T7-GGN-F | F | GCTTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCGGTGGTAACATTTCAGAC |

| T7-GGN-R | R | GCTTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCCGCCGTCTGCATCACCG |

F, forward; R, reverse.

AcMNPV vp1054 knockout repair constructions.

To prepare a vp1054 repair donor vector, plasmid pFB-egfp (21) was modified by removing the polh promoter sequence and replacing it with a fragment containing the vp1054 promoter region and the vp1054 ORF. First, a 1,714-bp fragment containing both the vp1054 promoter and ORF was amplified, using primers vp1054-Rep-F and vp1054-Rep-R (Table 1) from bacmid bMON14272, and cloned into pJet1.2/Blunt (Fermentas). The error-free vp1054 cassette was then subcloned between the Bst1107I and XbaI sites in pFB-egfp (21), creating pFB-egfp-vp1054-Rep. To prove the integrity of the lef-10 ORF in the created Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid, an additional cassette that encoded the lef-10 promoter plus ORF was amplified with primers vp1054-Rep-F and lef-10-R (Table 1). The PCR product was cleaved with StuI and XbaI and cloned between the Bst1107I and XbaI sites in pFB-egfp (21), creating pFB-egfp-lef-10-Rep.

Finally, both donor plasmids, pFB-egfp-vp1054-Rep and pFB-egfp-lef-10-Rep, were independently used for transposition into the polh locus of the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid. Screening of transposition-positive bacmids was performed by a triplex PCR strategy (21). The final recombinant bacmids/viruses were named Ac-Δvp1054-Rep and Ac-Δvp1054-lef-10.

Cell-based assays and electron microscopy (EM).

Two micrograms of DNA of the deletion and repair bacmids was used to transfect 1 × 106 Sf9 cells with Cellfectin II (Invitrogen). At 4 days posttransfection (p.t.), the culture supernatant was centrifuged for 5 min at 2,000 × g and used to infect 1.5 × 106 Sf9 cells. Viral propagation was followed by fluorescence microscopy at various time points p.t. or postinfection (p.i.). The Ac-wt (21) bacmid/virus that also carried an egfp marker served as a positive control.

To compare BV release kinetics, one million cells were either transfected with 2 μg of bacmid DNA or infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) unit/cell. Cell culture media were harvested at various time points and analyzed for the presence of infectious BV by endpoint dilution. The averages of the infectious titers from three independent transfections or infections were calculated and plotted into graphs.

To evaluate the level of viral very late gene expression in the absence of VP1054, Sf9 cells (1.5 × 106) were transfected with 2 μg of bacmid DNA of Ac-Δvp1054 or Ac-Δgp64 (22). At 4 days p.t., the cells were harvested and processed for Western blot analysis. Expression of egfp, driven by the very late p10 promoter, was detected by anti-enhanced green fluorescent protein (anti-EGFP) antiserum (Molecular Probes) and quantified by densitometric analysis using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The significance of the observed differences was analyzed by the Student t test.

For EM studies, Sf9 cells (3.5 × 106 cells/flask) transfected with 15 μg of DNA of Ac-Δvp1054, Ac-Δvp1054-Rep or Ac-wt were harvested at 24 h p.t. and processed for transmission electron microscopy as described previously (25). Specimens were observed in a Philips CM12 electron microscope.

Purification and fractionation of BV virions.

To produce BVs with incorporated Flag-tagged VP1054, an expression cassette coding for N-terminally Flag-fused VP1054 was amplified with primers flag-vp1054-F and vp1054-rep-R (Table 1) from bacmid bMON14272. The error-free cassette was then cloned between the SacI and XbaI sites of pIB plasmid (Invitrogen), creating pIB-flag:vp1054.

In the next step, 3.0 × 108 Sf9 cells were cotransfected with the Ac-wt bacmid and pIB-flag:vp1054 plasmid. Five days p.t., BV-enriched medium was collected and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 80,000 × g (Beckman SW28 rotor) for 60 min at 4°C. The BV pellet was resuspended in 350 μl of 0.1× TE (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]) buffer, loaded onto a linear sucrose gradient (25 to 56%, wt/vol), and ultracentrifuged at 80,000 × g (Beckman SW55 rotor) for 90 min at 4°C. The formed BV band was collected and diluted in 12 ml of 0.1× TE. The BV preparation was concentrated at 80,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C, and the final virus pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of 0.1× TE.

The purified BV virions were separated into nucleocapsid and envelope fractions as described previously (26). Final fractions were processed for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted against either mouse monoclonal anti-Flag antibody (Stratagene), rabbit polyclonal anti-VP39 antiserum (directed against the major capsid protein and kindly provided by Lorena Passarelli, Kansas State University), or rabbit polyclonal anti-GP64 antiserum (directed against the BV envelope protein GP64) (27).

Viral DNA replication assay.

To determine the viral DNA replication capacity of the AcMNPV Δvp1054 genome, a quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)-based assay was carried out as previously described (16, 18), in which we monitored levels of viral DNA in insect cells transfected either with Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid or Ac-Δvlf1 bacmid. The latter bacmid, which was constructed analogously to a published protocol (16), served as a referential genotype for a “single-cell infection phenotype” virus.

Production and purification of His-tagged VP1054 proteins.

To produce His-tagged VP1054, the full-length AcMNPV vp1054 ORF was amplified with primers vp1054-E-F and vp1054-E-R (Table 1) and cloned between the NdeI and SacI sites of the pET28a (Novagen) expression vector. Overexpression was performed by induction of Escherichia coli BL21 DE cells grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼1.0) with 0.5 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h. Harvested bacteria were resuspended and sonicated in buffer A (200 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.3% N-lauryl sarkosine, 5 mM imidazole, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatants were loaded onto nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose affinity columns (Qiagen), and bound proteins were eluted with 250 mM imidazole in buffer A and stored in this solution at 4°C or flash frozen at −80°C for long-term storage. The concentrations of purified proteins were determined by the standard Bradford method.

To generate a triple-alanine mutant of VP1054 (R152A/Y154A/D156A), for simplicity further referred to as VP1054-AAA, a fusion PCR strategy was used. Primers are listed in Table 1. The gene construct was cloned between the NdeI and SacI sites of the pET28a (Novagen) expression vector, and overexpression in E. coli was performed in a manner similar to that described above for wild-type VP1054.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

A 152-bp DNA probe encompassing a GGN repeat-rich sequence as is found in the p78/83 ORF of the AcMNPV genome was amplified from bMON14272 (20) bacmid DNA with GGN-F and GGN-R (Table 1) primers. In the next step, the PCR product was used as the template for asymmetric PCRs, in which either positive (GGN-rich) or negative (CCN-rich) single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules were synthesized using GGN-F and GGN-R primers, respectively.

To generate RNA probes, an analogous 152-bp DNA fragment was amplified with primer pair T7-GGN-F/GGN-R or GGN-F/T7-GGN-R (Table 1), thereby introducing a T7 promoter sequence. One microgram of purified PCR product was used as the template for RNA synthesis using the T7 RiboMAX Express RNAi system (Promega). After RNA synthesis, DNA templates were removed with DNase I. The RNAs were isopropanol precipitated, resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water, and kept at −80°C.

The synthesized ssDNA and RNA probes were then terminally labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using polynucleotide kinase (Fermentas). The binding reactions (30 μl) were carried out in 10 mM HEPES (pH 8.0)–200 mM KCl–1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), in which the labeled DNA or RNA probe (∼100 nmol) was mixed with various amounts of VP1054 protein or bovine serum albumin (BSA) control protein. The assembled reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 15°C. One-half of the reaction volume was then run on 6% polyacrylamide gels in standard 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (pH 8.3) buffer at room temperature. Autoradiographs were made using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The EMSA results were quantified by densitometric analysis of the bands corresponding to unbound (free) DNA or RNA probes using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The significance of the observed differences was analyzed by the Student t test.

Computational biology methods.

The AcMNPV VP1054 sequence was searched against the nonredundant protein database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (28) with the iterated PSI BLAST algorithm (29) to identify VP1054 homologues. The sequence similarity between baculovirus VP1054 and cellular PURα proteins was revealed by a SMART (30) search. Multiple-sequence alignments were constructed using MUSCLE (31) with default parameters and manually edited in JalView (32). A phylogenetic tree was inferred on the basis of multiple alignments using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method as implemented in the software package MEGA4 (33), which was also used for bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates) and graphical representation of the tree. Theoretical molecular masses and isolectric points (pIs) of proteins were calculated with help of the Compute pI/Mw (34) tool on the EXPASY (35) server.

A structural model of the AcMNPV VP1054 core region (Asp54 to Ser217) was generated by a homology modeling method using the crystal structure of Drosophila melanogaster PURα (Glu41-Asn185) (Protein Data Bank [PDB] entry 3K44 [36]) as a template structure. Briefly, sequence alignment was constructed with MUSCLE (31), and the structural model was generated using the automodel function in Modeler 9v6 (37). The resulting model was evaluated by PROCHECK (38) and ANOLEA (39) to check for backbone problems and Ramachandran outliers. Calculation of evolutionary conservation between baculoviral VP1054 and cellular PURα proteins was performed on the ConSurf server (40). Structural alignment was computed on the DALI (41) webspace. Final adjustments and graphical visualization of the three-dimensional (3D) model were performed with PyMOL, version 1.5 (DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA).

RESULTS

Evolutionary conservation of VP1054.

To obtain better insight into the diversity and phylogeny of the VP1054 protein family, we used the PSI-BLAST (29) method to search the GenBank database using AcMNPV VP1054 as a query. After five iteration cycles, a set of 52 protein sequences was collected, which possessed significant similarity to AcMNPV VP1054. All VP1054 homologues were recognized in viruses from the family Baculoviridae, and all sequenced baculoviruses possessed a vp1054 gene. No VP1054-related sequences were identified in genomes of other arthropod-infecting DNA viruses, such as, for instance, nudiviruses, ascoviruses, nimaviruses, iridoviruses, and entomopoxviruses.

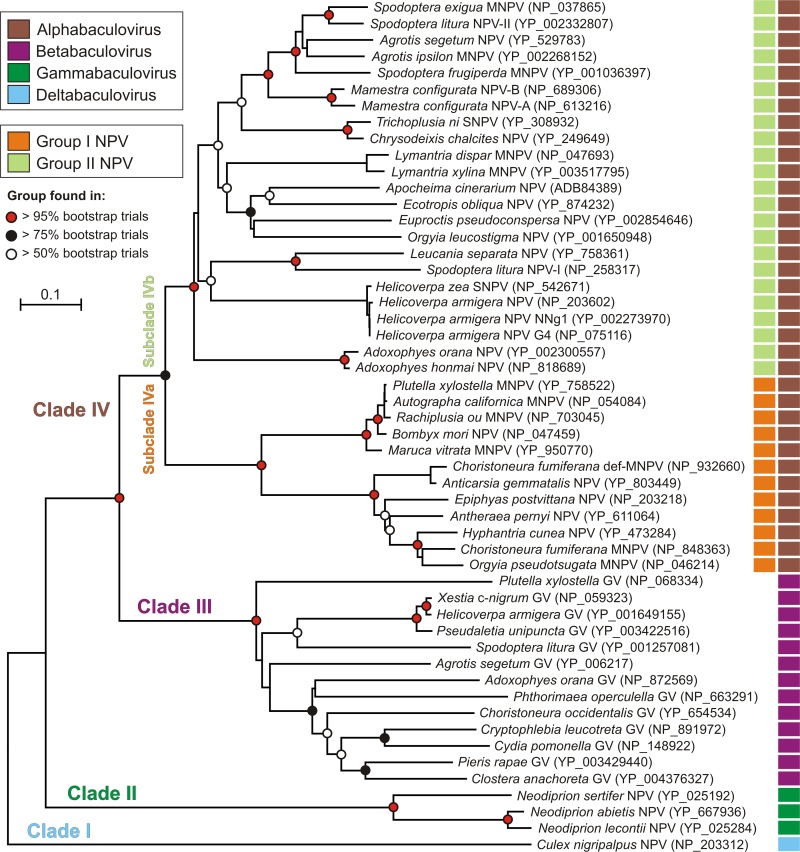

Using the collected VP1054 sequence data, a detailed phylogenetic NJ tree was inferred. The tree perfectly reflects the previously designed evolution scenario of all major baculovirus lineages (Fig. 2), indicating that a vp1054 gene was present in an ancestor of the current baculoviruses. The VP1054-based tree topology consists of four distinct clades (I to IV), where basal clade I represents the genus Deltabaculovirus with one member, dipteran-specific Culex nigripalpus NPV (CuniNPV). Clade II displays hymenopteran-specific NPVs, which belong to the genus Gammabaculovirus. Clade III shows the uniform group of lepidopteran-specific granuloviruses (GVs) belonging to the genus Betabaculovirus. Finally, clade IV includes the most abundantly analyzed group, the lepidopteran-infecting NPVs representing the genus Alphabaculovirus (Fig. 2). Noticeably, clade IV is further separated into two subclades (IVa and IVb) that correspond to the so-called group I and group II NPVs (42). While grouping within subclade IVb (group II NPVs) is poorly resolved at basal levels, subclade IVa is clearly separated into two monophyletic groups. The first group includes Bombyx mori NPV, AcMNPV, and AcMNPV-like viruses such as, for example, Rachiplusia ou MNPV. The second group includes, for instance, Choristoneura fumiferana MNPV, Orgyia pseudotsugata MNPV, and Anticarsia gemmatalis NPV.

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of baculovirus VP1054 protein sequences. All recognizable VP1054 homologous sequences were aligned with MUSCLE. The positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the data set, and phylogenetic neighbor-joining analysis was conducted in MEGA4. Numbers in parentheses are GenBank accession numbers. Color squares at each baculovirus strain indicate baculovirus classification as explained in the symbol key at the top left. Colored circles at branches denote the confidence estimations based on bootstrap sampling (out of 1,000 replicates) as described in the symbol key.

The results show that the vp1054 gene is conserved in all baculovirus genomes (hence is a core gene), which strongly hints at its functional importance for baculovirus biology. Moreover, the evolutionary conservation of VP1054 makes it a powerful tool for baculovirus phylogenetic studies as demonstrated in Fig. 2.

VP1054 is nucleocapsid-associated protein.

The VP1054 protein has been shown to be a component of both BV (43) and ODV (44). To determine whether VP1054 is a component of nucleocapsid or envelope, Sf9 cells were cotransfected with the Ac-wt bacmid and plasmid pIB-Flag:vp1054 coding for Flag-tagged VP1054. Harvested BVs were split into nucleocapsid and envelope fractions, which were then subjected to Western blot analysis. The incorporated Flag-VP1054 protein was detected as a band of ∼43 kDa in the nucleocapsid fraction (Fig. 3A, top). Proper separation of BV into nucleocapsid and envelope fractions was checked with antibodies against the major capsid protein (VP39) and the BV envelope protein (GP64) (Fig. 3A, middle and bottom panels). In summary, the BV fractionation provided information that VP1054 is a nucleocapsid-associated protein.

Fig 3.

VP1054 is required for cell-to-cell spread of virus infection. (A) VP1054 copurifies with nucleocapsids of budded virions. Budded virions (BV) released from Sf9 cells cotransfected with Ac-wt bacmid and pIB-Flag:vp1054 plasmid were separated into nucleocapsid (Nc) and envelope (Env) fractions. The incorporated Flag-VP1054 protein was detected on Western blots with anti-Flag antibody (top). Correct separation into Nc and Env fractions was controlled with anti-VP39 (middle) and anti-GP64 (bottom) antibodies. (B) Viral replication capacities of the Ac-Δvp1054 genome and its repaired versions. (i) Diagram of the egfp expression cassettes transposed into the polh loci of Ac-wt (a), Ac-Δgp64 (b), and Ac-Δvp1054 bacmids, leading to a vp1054 deletion (c) and repair (d) virus, and a lef10-repaired control (e). (ii) Time course fluorescence microscopy showing the propagation of the infection in Sf9 cells transfected with the resulting bacmid constructs. The progress of viral infection was followed by p10 promoter-driven egfp expression (converted green to black) at the indicated times p.t. At 96 h p.t., the cell culture supernatants were collected to initiate a secondary infection. (iii) Secondary infection assay. EGFP was detected at 48 and 72 h p.i. to signal the progress of infection. (C) One-step growth curves of the Ac-Δvp1054, Ac-Δvp1054-Rep, and Ac-wt bacmids following transfection (a) or infection (MOI = 1) (b). Cell culture supernatants were harvested at the indicated times p.t. or p.i. and analyzed for the release of infectious BV particles by endpoint dilution. Infectivity was monitored by EGFP expression. The points indicate the average titer derived from three independent transfections or infections, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. (D) Analysis of viral late gene expression. Sf9 cells were transfected with Ac-Δvp1054 and Ac-Δgp64 bacmids, both expressing the egfp reporter gene from the p10 promoter. At 72 h p.t., the production of EGFP was analyzed by Western blotting. Detection of cellular actin was used as an internal loading control. The values below the bands show the results of densitometric analysis indicating the relative proportion of detected proteins. The representative results from three independent measurements are shown. (E) Viral DNA replication assay. Sf9 cells transfected with the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid were harvested, and total DNA was purified at the indicated time points. A referential bacmid, Ac-Δvlf1, was used as a prototype for a “single-cell infection phenotype” that replicates viral DNA to normal levels. The data are expressed as percentages of DNA copies relative to the level of DNA synthesized by the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid at 72 h p.t. and represent the results of three separate assays (means ± standard deviations).

Deletion of vp1054 prevents cell-to-cell spread of the virus.

To confirm its functional importance, the vp1054 gene was deleted from the AcMNPV genome (in the form of a bacmid [45] in E. coli) by homologous recombination, thereby preventing mutations in the overlapping lef10 gene, as shown in Fig. 1 and described in Materials and Methods. A repair construct was also generated, designated Ac-Δvp1054-Rep, with the wild-type vp1054 ORF inserted into the polyhedrin (polh) locus under the control of the native vp1054 promoter. As an extra control, Ac-Δvp1054-lef-10 was constructed, in which the lef-10 ORF with its native promoter sequence was introduced at the polh locus. All constructs (Fig. 3Bi) contained an egfp reporter gene under the control of the AcMNPV p10 promoter in order to follow the spread of infection in cell culture and to measure viral very late gene expression.

To investigate the effect of the deletion of the vp1054 gene on baculovirus infection, insect cells were separately transfected with the Ac-Δvp1054 knockout genome and its repaired versions and monitored for infection spread. When the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid was introduced into Sf9 cells, no viral propagation was observed in the cell culture (Fig. 3B). We could observe only a “single-cell infection” phenotype similar to the phenotype of an Ac-Δgp64 bacmid, indicating that the vp1054 deletion prevented formation of infectious BV particles.

Complete restoration of viral infectivity was achieved when the vp1054 ORF was introduced into the heterologous polh locus of the vp1054 null genome. Time course fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3B) and endpoint dilution assays (Fig. 3C) proved that the rescued Ac-Δvp1054-Rep bacmid showed viral replication kinetics similar, if not identical, to those of Ac-wt. On the other hand, insertion of the lef-10 ORF into the polh locus did not recover virus propagation, demonstrating that the observed loss of infectivity of the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid was entirely associated with the VP1054 function (Fig. 3B).

In addition, in insect cells transfected with the vp1054 null baculovirus genome, infection proceeded into the very late phase of infection. As shown in Fig. 3B, very late gene expression is still achieved, as demonstrated by p10 promoter-driven egfp expression. A comparative immunoassay was performed in order to quantify very late gene expression. Sf9 cells were transfected in parallel with either the Ac-Δvp1054 or Ac-Δgp64 bacmid, both encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) under the control of the p10 promoter and both displaying the single-cell infection phenotype. Western blotting profiles showed that EGFP was produced at similar levels with both tested baculovirus genotypes (Fig. 3D). Thus, the results show that VP1054 is not required for viral very late gene expression, suggesting an essential role for VP1054 in another viral process.

VP1054 is not required for viral DNA replication.

To assess whether the VP1054 protein is involved in the replication of the viral genome, a comparative DNA replication assay was performed. Sf9 cells were transfected with the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid, and the level of viral DNA was monitored at different time points as indicated in Fig. 3E using qPCR. In order to be able to evaluate the DNA replication kinetics of the vp1054 knockout bacmid, a control AcMNPV mutant, Ac-Δvlf-1, was used. Analogous to the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid, this mutant bacmid is not able to initiate viral cell-to-cell transmission. Deletion of vlf-1 (16) does not affect viral DNA replication capacity, allowing its application in comparative replication assays. As shown in Fig. 3E, we demonstrate that the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid is capable to synthesize amounts of nascent DNA similar, if not identical, to those synthesized by the Ac-Δvlf-1 bacmid by 72 h posttransfection. These data show that the phenotype of the vp1054 knockout does not result from a deficiency in viral DNA synthesis.

Cellular features of baculovirus infection without VP1054.

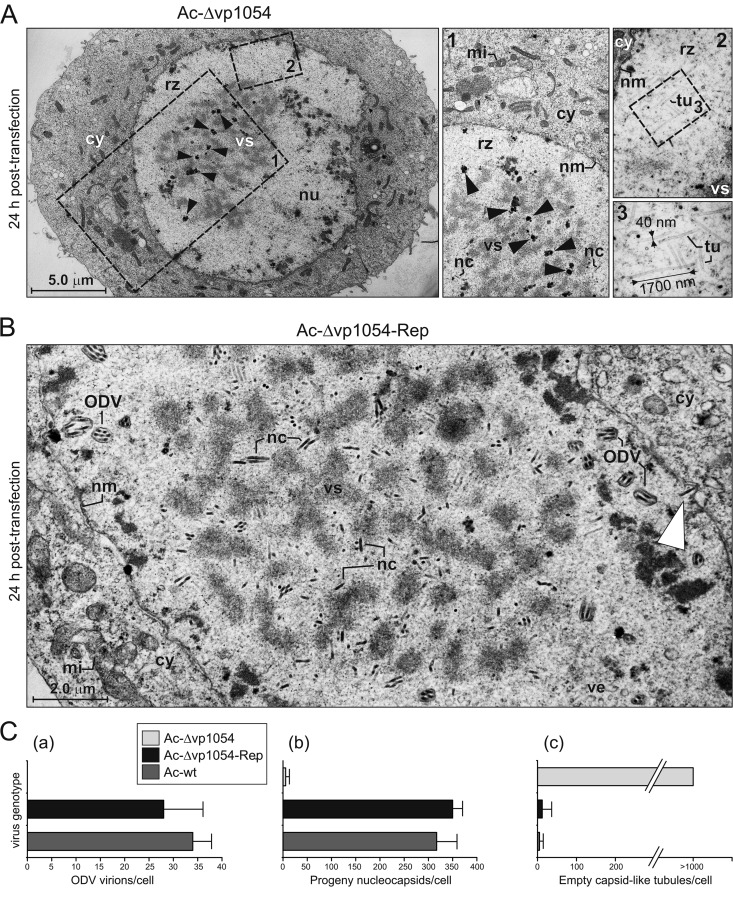

To study the effect of the deletion of the vp1054 gene on the baculovirus infection cycle at the cellular level, EM was performed on ultrathin sections generated from bacmid-transfected cells. The Ac-Δvp1054-transfected cells developed the typical cytopathic effects of a baculovirus infection, characterized by an enlarged nucleus in which the reticulate viral replication factory, the so-called virogenic stroma (VS), was formed (Fig. 4A). A first remarkable feature of Ac-Δvp1054-transfected cells, distinguishing them from both Ac-Δvp1054-Rep- and Ac-wt-transfected cells, was the absence of ODV virions, which are typically built up in the nuclear periphery, as shown and evaluated in Fig. 4B and C.

Fig 4.

Novel electron-dense bodies and electron-lucent capsid-like tubules are formed in the absence of the VP1054 protein. (A) Sf9 cells transfected with the Ac-Δvp1054 bacmid were harvested at 24 h p.t. and processed for EM. Black arrowheads indicate the presence of novel, electron-dense bodies (EDBs) distributed within the virogenic stroma. The magnified insets point out the atypical EDBs associated with the viral replication factory (inset 1) and the presence of translucent, capsid-like tubules of aberrant lengths in the peristromal space (ring zone) (insets 2 and 3). (B) Sf9 cell transfected with the rescued Ac-Δvp1054-Rep bacmid, and processed for EM as indicated above. The white arrowhead indicates a progeny nucleocapsid leaving the cell nucleus to form a BV particle. Abbreviations (A and B): cy, cytoplasm; nc, nucleocapsid; nm, nuclear membrane; nu, nucleus; rz, ring zone; mi, mitochondrion; tu, capsid-like tubules; ve, virus-induced intranuclear membrane vesicles; vs, virogenic stroma. (C) Quantitative analysis of the number of ODV virions (a), progeny nucleocapsids (b), and aberrant capsid-like tubules (c) occurring in cells transfected with Ac-Δvp1054, Ac-Δvp1054-Rep, and control Ac-wt bacmids. In total, 26 cells were inspected for each virus genotype, and the data are expressed as means ± the standard deviations.

Careful inspection of cell nuclei further showed that deletion of the vp1054 gene strongly affected the formation of progeny nucleocapsids, which normally assemble and mature within the virogenic stroma, as was observed for Ac-wt (data not shown) or rescued Ac-Δvp1054-Rep genomes (Fig. 4B). While we could count hundreds of progeny nucleocapsids in cells transfected with either Ac-wt (344 ± 21) or Ac-Δvp1054-Rep (318 ± 36), in the Ac-Δvp1054-transfected cells, only minimal numbers (5 ± 3) of normally appearing, VS-associated nucleocapsids were found (Fig. 4A to C). Instead, dozens of novel, electron-dense bodies (EDBs) distributed within the VS of the Ac-Δvp1054-transfected cells were observed (Fig. 4A). In addition, a considerably high number of electron-lucent, capsid-like tubules were observed in the peristromal compartment of the nucleoplasm (the so-called ring zone) in the Ac-Δvp1054-transfected cells (Fig. 4A). These capsid-resembling tubules were ∼40 nm in diameter and had variable lengths, ranging from 100 to 2,600 nm.

Taking these EM observations together, the presence of the atypical EDBs in the VS, the site of viral DNA amplification and processing, and the electron-lucent (DNA-free) capsid-like structures in the Ac-Δvp1054-transfected cells suggest that VP1054 performs a crucial role in processing of viral genomes and/or their packaging into progeny nucleocapsids.

In silico analyses predict that VP1054 is a PURα-like protein.

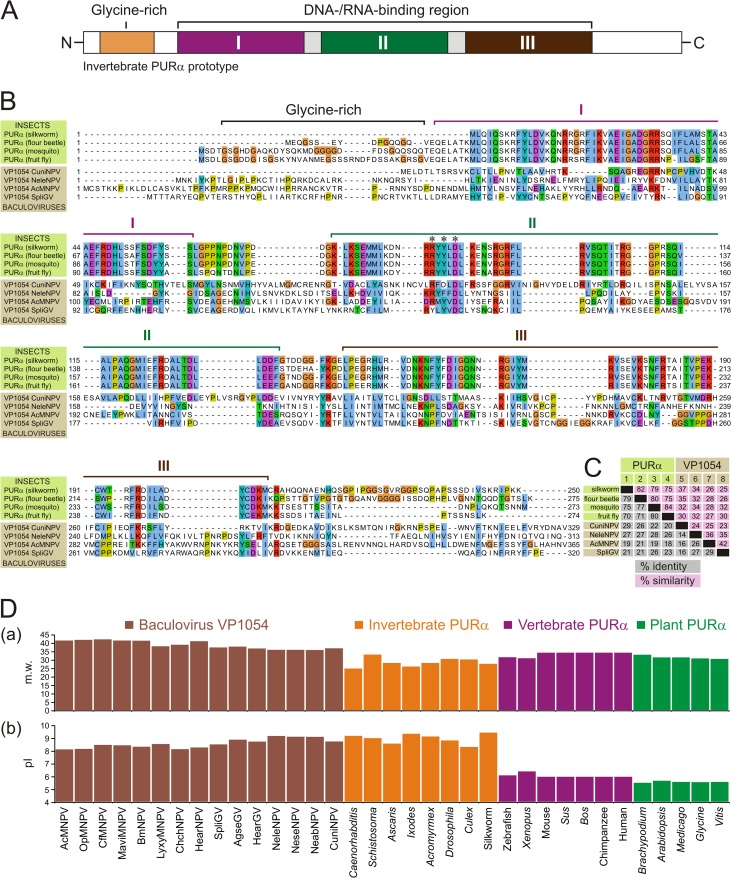

In order to reveal the biological properties of the VP1054 protein, in silico approaches have been applied. With help of RADAR (46), a tool for the identification of repeats in protein sequences, we noted that VP1054 proteins contain repeated motifs that are markedly preserved in members of the genus Gammabaculovirus, for instance, Neodiprion lecontii NPV (NeleNPV) (data not shown). Unexpectedly, database mining using NeleNPV VP1054 as a query revealed an apparent sequence similarity with the family of cellular purine-rich-element-binding PURα proteins. In general, PURα is a multifunctional, single-stranded DNA-/RNA-binding protein which specifically recognizes GGN repeats and functions in many cellular events, including the initiation of DNA replication, DNA recombination, viral and cellular regulation of gene transcription, cell cycle regulation, and mRNA export and translation (see references 47 and 48 for reviews). Notably, PURα proteins contain three large repeated domains (PUR-I to PUR-III), as schematically depicted in Fig. 5A. The VP1054 sequences of representative members of the four baculovirus genera aligned with a set of well-defined insect PURα proteins are illustrated in Fig. 5B. The calculated values of identities and similarities between baculovirus VP1054 and insect PURα proteins are summarized in Fig. 5C. For instance, AcMNPV and NeleNPV VP1054 sequences showed 21% (28%) and 27% (32%) identity (similarity), respectively, to the Tribolium castaneum (flour beetle) PURα sequence. Unlike PURα, baculovirus VP1054 proteins lack the typical N-terminal glycine-rich domain (Fig. 5). In addition, sequence comparison showed that VP1054 sequences contain several major insertions, whereas the dipteran-specific CuniNPV VP1054 has the largest number of such insertions (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

Baculovirus VP1054 proteins share sequence similarity with cellular nucleic acid-binding PURα proteins. (A) Schematic representation of the domain topology of insect PURα proteins. A glycine-rich N-terminal part is followed by three repeats (I, II, and III), which are responsible for nucleic acid recognition. Domain colors correspond to the ribbon diagram in Fig. 6A. (B) Sequence alignment of the well-defined insect PURα and baculovirus VP1054 proteins. The alignment was constructed using the MUSCLE algorithm, and coloring was performed in JalView. (C) Pairwise sequence comparison between cellular PURα and baculovirus VP1054 proteins. Percent identity and percent similarity were computed using SIAS. The similarity was scored using the BLOSUM62 matrix. (D) Overview of estimated molecular weights (m.w.; in thousands) (a) and isoelectric points (b) computationally calculated for a set of representative baculovirus VP1054 and cellular PURα proteins.

Besides the sequence similarity, baculovirus VP1054 proteins also share some physicochemical parameters with invertebrate PURα proteins. While theoretical molecular masses of baculoviral VP1054 proteins are moderately higher than for cellular PURα, likely due to the above-mentioned insertions, their isoelectric points (pIs) are very similar (Fig. 5D). Both VP1054 and invertebrate PURα proteins have a conserved basic pI, typically ranging between 8.0 and 9.2. On the other hand, pI values of vertebrate (∼6.0) and plant (∼5.5) PURα proteins are markedly lower (Fig. 5D). This substantial difference between invertebrate PURα, including the baculovirus PURα-like protein VP1054, and vertebrate and plant PURα proteins may reflect diverse biological properties.

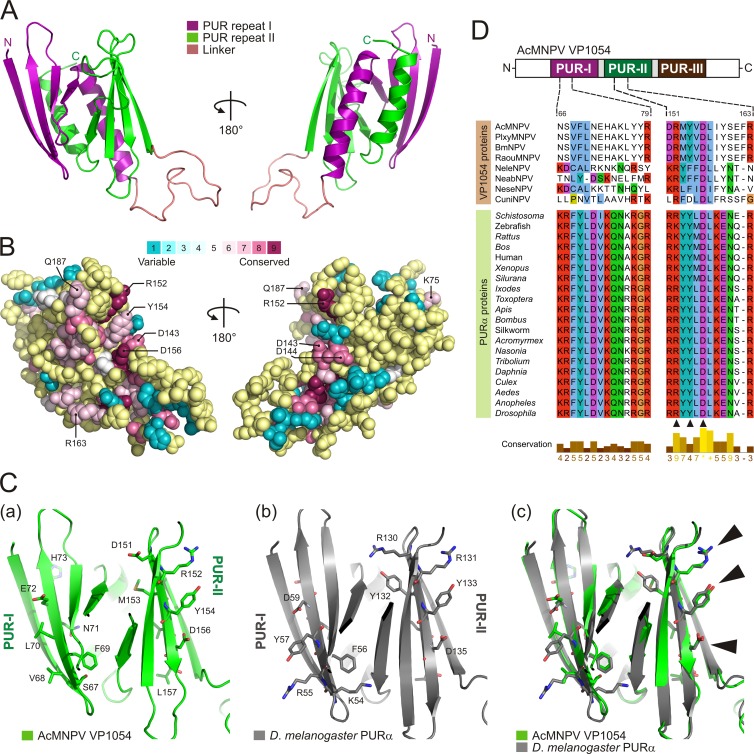

Structural model of VP1054.

Homology-based modeling of the core region (Asp54-Ser217) of AcMNPV VP1054 yielded a pseudoatomic model similar to the template structure of D. melanogaster PURα, with a Cα root mean square deviation of 1.1 Å. The overall model adopts a PUR domain structure (36), in which two PUR repeats, both with ββββα topology, interact with each other (Fig. 6A). Two PUR repeats (I and II) are connected by a linker loop, which is extremely extended in VP1054 due to the above-mentioned insertions. A ConSurf analysis (40) for VP1054 revealed that several highly conserved residues are present on the surface of the PUR-II repeat, one of the putative sites recognizing target nucleic acid (36). These residues include Asp143, Asp144, Arg152, Tyr154, Asp156, and several others as marked in Fig. 6B.

Fig 6.

Homology-derived structural model of the AcMNPV VP1054 protein. (A) Ribbon backbone model of the AcMNPV VP1054 sequence Asp54-Ser217. The PUR-like repeat domains I and II (both with ββββα topology) are connected by a linker loop. (B) ConSurf analysis for the VP1054 protein. The 3D structure is presented using a space-filled model. The amino acids are colored by their degree of conservation as explained in the color key. Yellow spheres indicate insufficient data. The model reveals that several conserved amino acid positions are found within PUR repeat II, while PUR I does not contain highly conserved residues. The analysis was performed using a pseudoatomic model of AcMNPV VP1054 (sequence Asp54 to Ser217), and the image was generated in PyMol script output by ConSurf. (C) Ribbon diagrams of the putative nucleic acid-binding regions of the AcMNPV VP1054 and D. melanogaster PURα rendered in separate (a and b) and superposed (c) views. Arrowheads indicate the presence of the evolutionarily conserved triad of amino acids (Arg-Tyr-Asp) on the surface of the PUR-II domain. (D) Alignment of the baculovirus VP1054 and cellular PURα proteins. Only the sequence encompassing the surface regions of both PUR-I (left) and PUR-II (right) are shown. The top scheme shows topology of the domains in a typical PURα. The alignment demonstrates high conservation of some amino acid positions within the PUR-II domain, which include Arg152, Tyr154, Asp156, and Leu157 in AcMNPV VP1054. Black triangles below the alignment mark the conserved triad of amino acids.

Importantly, a common structural feature characteristic for both PURα and VP1054 is the presence of a highly conserved triad of residues, Arg-Tyr-Asp, on the surface of the PUR-II repeat (Fig. 6D). Only a few exceptions were found, including the substitution of Tyr into Phe or Asp in the hymenopteran or dipteran NPVs, respectively. While an analogous triad (Arg-Tyr-Asp) is also present in the PUR-I repeat of cellular PURα proteins, the PUR-I-like repeat of VP1054 proteins has strongly diverged and is much more variable (Fig. 6C and D). The biological implications of these structural dissimilarities between PURα and VP1054 proteins are not clear. Nevertheless, although structural information on how PURα proteins recognize their target nucleic acid molecules is still missing, the presence of the conserved triad (Arg-Tyr-Asp) in the PUR-II repeat suggests that these residues may be involved in nucleic acid binding.

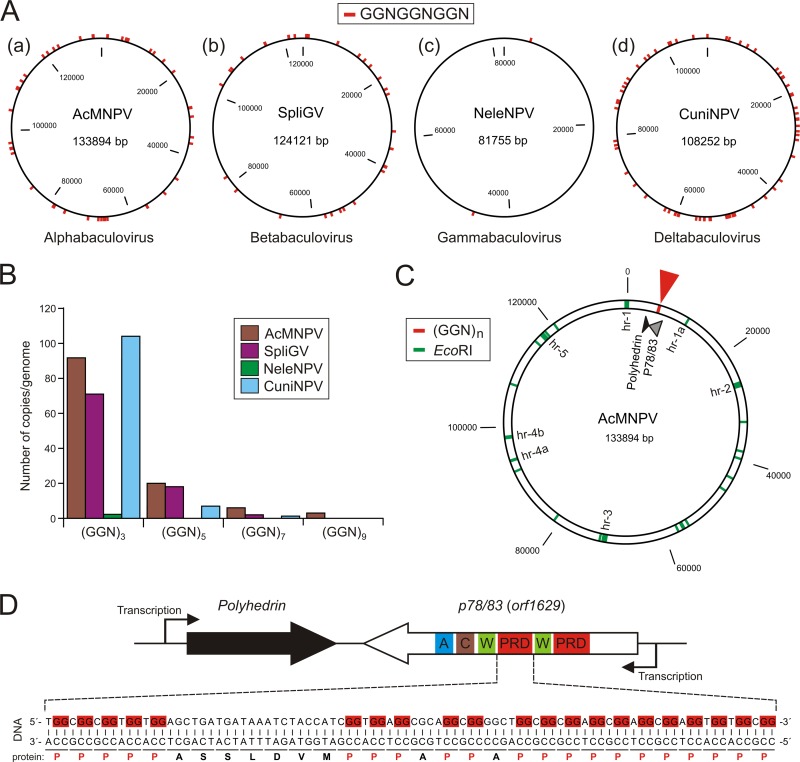

Disproportionate distribution of GGN repeats in baculovirus genomes.

Since the in silico analyses revealed apparent resemblance of baculovirus VP1054 with cellular, GGN repeat-binding PURα proteins, we aimed in the next step to search for such putative recognition sites in baculoviral genomes. The results of the scanning of baculoviral genomes using a tandem sequence of three GGN repeats, (GGN)3, as a query are shown in Fig. 7A. Generally, while members of the alphabaculovirus, betabaculovirus, and deltabaculovirus genera contain several dozens of (GGN)3 repeats, gammabaculovirus genomes carry a substantially lower number of these repeats (Fig. 7A). For instance, in the NeleNPV genome, only two (GGN)3 motifs were found, which are, interestingly, situated on opposite positions on the circular genome map (Fig. 7A).

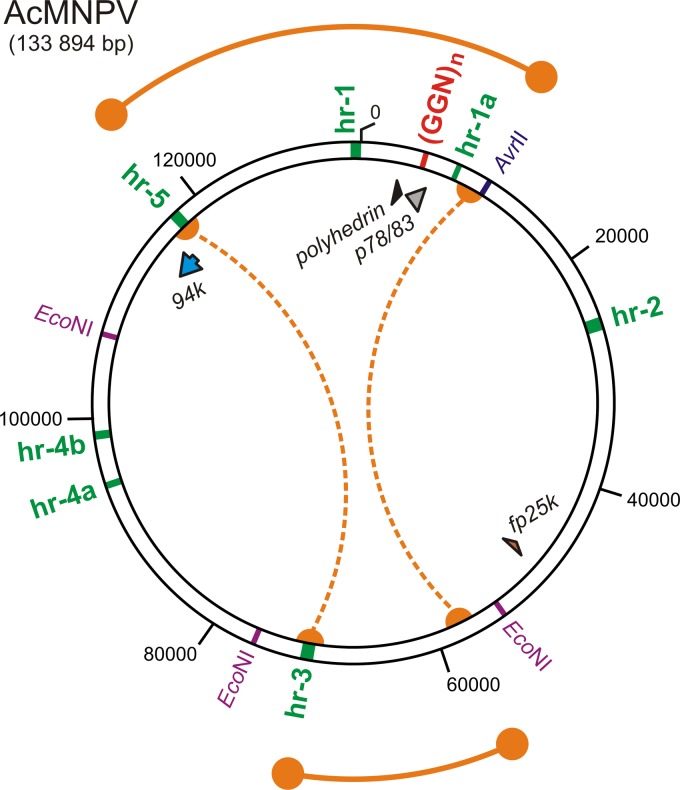

Fig 7.

Presence and distribution of GGN repeats in baculovirus genomes. (A) Schematic representation of the overall occurrence of basic (GGN)3 repeats in representative members of all baculovirus genera, namely, the baculovirus prototype AcMNPV, Spodoptera litura granulovirus (SpliGV), Neodiprion lecontii nucleopolyhedrovirus (NeleNPV), and Culex nigripalpus (CuniNPV). The baculovirus genomes are depicted as black circles, and the red marks indicate positions of (GGN)3 repeats. (B) Clustering of GGN repeats. Numbers of (GGN)n clusters were calculated for representative baculovirus genomes and plotted into the graph. The data demonstrate the trend of GGN motif clustering typical for all baculovirus genera with the exception of gammabaculoviruses, in which only the basic (GGN)3 repeats are found. (C) Position of GGN clustered sequences in the AcMNPV genome. The AcMNPV genome is represented as a black, double-line circle with depicted homologous regions (hr-1 to hr-5) revealed by accumulated EcoRI recognition sites (green marks). The diagram shows the close proximity of the major GGN cluster sequence (red mark) and the polh locus coding for the major occlusion protein, polyhedrin. (D) The GGN clusters in AcMNPV genome are hidden in the essential orf1629 gene, which codes for the actin-interacting phosphoprotein P78/83. The top scheme shows the organization and transcriptional direction of the two neighboring loci, polh and orf1629. The domain topology of encoded protein ORF1629 (P78/83) is also shown. W, WH2; C, connector (C-motif); A, acidic region. The bottom PRD-coding DNA sequence reveals the presence of clustered GGN motifs.

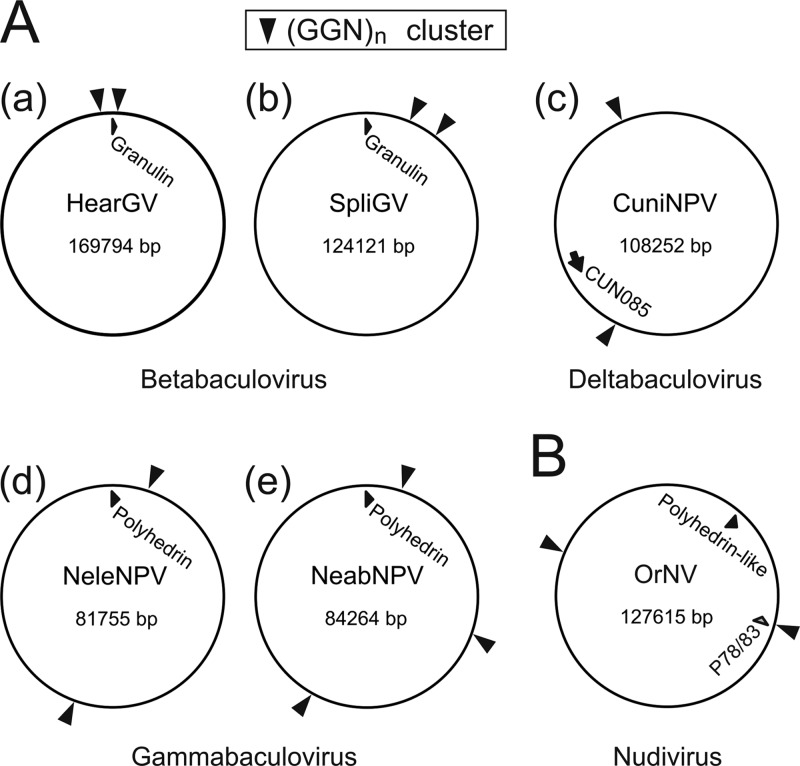

Further searches revealed that GGN repeats are markedly clustered in most baculoviral genomes, with the exception of hymenopteran-specific NPVs, in which limited (GGN)3 repeats are found (Fig. 7B). The highest level of GGN clustering is observed in the genomes of the evolutionarily most advanced group of baculoviruses, the lepidopteran-specific NPVs (42). For instance, the AcMNPV genome contains several GGN islands formed by up to 11 GGN repeat sequences. A fundamentally interesting fact is that these GGN islands tend to be located in a distinct area of the genome, typically in close proximity to the major occlusion body protein (polyhedrin/granulin)-encoding gene (Fig. 7C and D). In AcMNPV and other alphabaculoviruses, the GGN islands are hidden in the polyhedrin-adjoining essential gene p78/83 (orf1629), where the repeated GGN motifs encode proline-rich domains (PRDs) (Fig. 7C and D). Surprisingly, most baculoviruses that lack a p78/83 gene also contain GGN clusters located in proximity to the major occlusion body protein gene, as schematically depicted in Fig. 8A. Lastly, additional searches showed that GGN clusters are also abundantly present in genomes of other large nucleus-replicating arthropod-infecting DNA viruses, despite the absence of a vp1054 homologue, as shown, for example, in the Oryctes rhinoceros nudivirus (OrNV) genome (Fig. 8B), in which, however, the GGN cluster-containing p78/83 gene (ORF37) is rather separated from the polyhedrin-like gene (ORF16).

Fig 8.

(A) Occurrence of GGN repeat clusters in genomes of baculoviruses lacking a p78/83 gene. A schematic diagram shows positions of GGN-rich clusters in relation to the major occlusion protein coding gene in Helicoverpa armigera granulovirus (HearGV) (a) and Spodoptera litura granulovirus (SpliGV) (b), CuniNPV (c), NeleNPV (d), and Neodiprion abietis nucleopolyhedrovirus (NeabNPV) (e). Arrowheads on the surface indicate the presence of GGN repeat clusters, and the black arrows represent the major occlusion body protein genes. (B) Presence of GGN-rich sequences in the genome of the Oryctes rhinoceros nudivirus (OrNV). Arrowheads indicate the positions of GGN clusters, the black arrow indicates the gene coding for a polyhedrin-like protein, and the gray arrow shows the position of the p78/83 homologue.

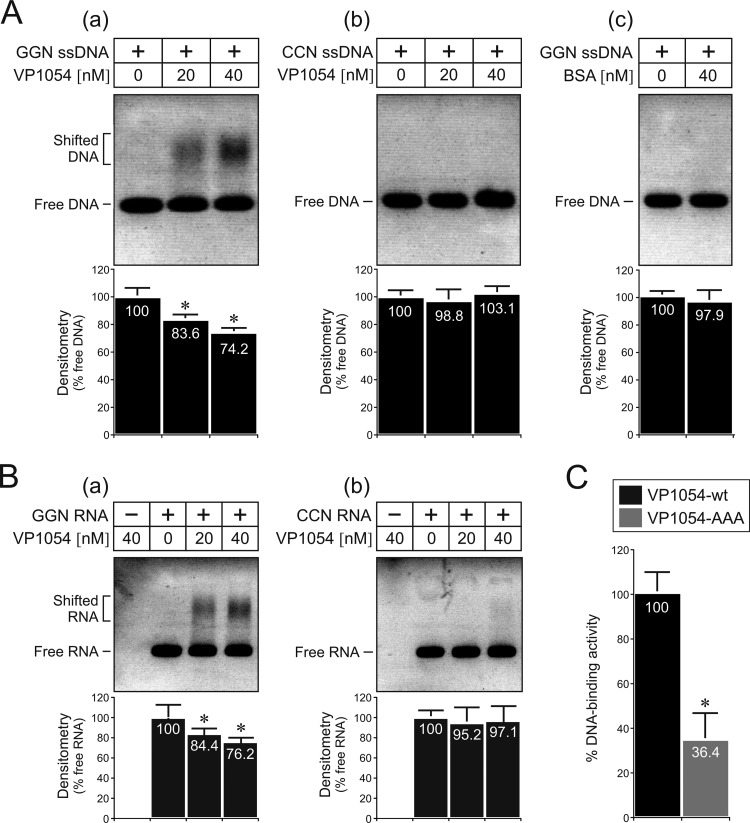

VP1054 is a nucleic acid-binding protein that recognizes GGN repeats.

To examine the nucleic acid-binding properties of the putative baculovirus PURα-like protein, recombinant full-length AcMNPV VP1054 was produced and analyzed by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Both positive and negative strands of the GGN repeat-rich sequence as present in the AcMNPV p78/83 gene (see Fig. 7D) were used as ssDNA probes. The VP1054 protein obviously showed the ability to interact with the ssDNA probe containing the repeated GGN motifs in a dose-dependent manner, as demonstrated by the shift in DNA migration in the presence of VP1054 (Fig. 9Aa). On the other hand, no migration shift was observed when the complementary ssDNA probe was used that contained CCN repeats, or when VP1054 was replaced with the control protein BSA (Fig. 9Ab and c), signifying that VP1054 specifically recognizes GGN repeats. These observations were confirmed by densitometric measurements, which showed a statistically significant preference of VP1054 for the GGN repeat-rich ssDNA sequence (Fig. 9A). Since cellular PURα proteins also bind RNA molecules, we examined whether VP1054 has the capacity to interact with in vitro-synthesized RNAs. The RNA-binding assays showed that the VP1054 interacts with a GGN motif-containing RNA probe in a manner similar to how it interacts with the GGN ssDNA (Fig. 9B).

Fig 9.

Baculovirus VP1054 is a nucleic acid-binding protein that recognizes purine-rich GGN repeats. (A) Full-length VP1054 interacts with GGN repeat-containing ssDNA (a) but does not bind to control ssDNA with CCN repeats (b). Control EMSA with a GGN ssDNA probe in combination with BSA (c). The results of three independent measurements, with error bars giving the standard deviations, are shown. The bars with an asterisk are significantly different from the control without VP1054 (P = 1.8 × 10−5 by Student t test). (B) VP1054 also recognizes and binds to GGN-rich RNA (a) but not to control (CCN) RNA sequences (b), as determined by EMSA. The graphs below the blots all show the results of densitometric analysis, indicating the proportion of unbound (free) DNA/RNA relative to the input. The results of three independent measurements, with error bars giving the standard deviations, are shown. The bars with an asterisk are significantly different from the control without VP1054 (P = 8.2 × 10−4 by Student t test). (C) DNA-binding activity of the triple-alanine VP1054 mutant (VP1054-AAA). The experiment was performed in triplicate; data indicate the averages of relative GGN-containing ssDNA-binding activity (VP1054-wt = 100%), and error bars represent the standard deviations.*, P = 1.3 × 10−5 (Student t test).

The EMSA results thus demonstrated that the baculovirus putative PURα-like protein VP1054 exhibits nucleic acid-binding capacity with preference for GGN repeats. Such repeats are part of the viral genome (see Fig. 7).

Surface mutations in PUR-II-like domain abolish DNA-binding activity.

Homology modeling revealed that baculovirus VP1054 proteins share with cellular PURα proteins a highly conserved triad of surface residues, Arg-Tyr-Asp, located in the PUR-II repeat (Fig. 6C and D). To examine whether these residues play a role in target DNA recognition, we cloned and produced a triple-alanine mutant of VP1054 (R152A/Y154A/D156A), for simplicity referred as VP1054-AAA. Subsequent in vitro DNA-binding assays showed that these surface mutations in the putative PUR-II domain dramatically abolished DNA-binding activity compared to wild-type VP1054 (VP1054-wt) protein (Fig. 9C). The results thus strongly suggest that these conserved residues (R152, Y154, and D156) are a part of molecular surface, which recognizes target GGN repeat-containing nucleic acids.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we applied multiple approaches to understand the biological functions of the baculovirus structural protein VP1054. We also addressed the question of whether sequence similarities existed between VP1054 and proteins deposited in the protein databases in order to get insight into the evolutionary history of VP1054.

VP1054 is encoded by one of the evolutionarily conserved baculovirus core genes (Fig. 2), which indirectly highlights its functional importance in viral infection. To explore the role of VP1054 in the baculovirus infection cycle, we deleted the vp1054 gene from the AcMNPV genome. Cell culture assays showed that removal of the vp1054 gene completely prevents cell-to-cell spread of the virus (Fig. 3), confirming the functional essentiality of VP1054. Nevertheless, the individually infected cells proceeded into the very late phase of infection (Fig. 3D). The ultrastructural analysis revealed that assembly of progeny nucleocapsids is dramatically reduced in the absence of VP1054 (Fig. 4A). Instead, novel electron-dense structures or EDBs, associated with the virogenic stroma, and numerous electron-lucent capsid-like tubules were formed (Fig. 4A). These observations are not fully in accordance with results (49) obtained previously for an AcMNPV strain containing a temperature-sensitive (ts) mutation in the vp1054 gene (Ac-tsVP1045). This ts mutation (49) corresponded to the presence of valine at position 293 of the VP1054 protein, while phenylalanine at this position, which maps to the putative PUR-III repeat (Fig. 5B), is present in the wild-type sequence. Recently, it has been shown for cellular PURα protein (36) that the PUR-III repeat is involved in self-association of this protein. Therefore, the analyzed ts mutation in VP1054 (49) might affect VP1054 dimerization. Crucially, while VS-associated EDBs were also observed in study by Olszewski and Miller (49), no electron-lucent capsid-resembling structures were observed in cells upon Ac-tsVP1045 infection under nonpermissive conditions (49). This difference may be explained by either different host cell lines, variations in specimen treatments for EM analysis (in which electron-lucent tubules could have been overlooked [49]), or different behaviors of the two AcMNPV genotypes. Unlike Olszewski and Miller (49), we do not conclude that the VS-associated EDBs are improperly folded nucleocapsids. These EDBs may be accumulated viral genomes, since genome encapsidation and consequent export by progeny nucleocapsids are likely impaired, as demonstrated by thousands of electron-lucent capsid-like tubules (Fig. 4A).

It should also be noted that the vp1054 ORF is located in a gene cluster of five ORFs (ac53, lef-10, vp1054, ac55, and ac56) which all have the same clockwise orientation. This cluster is markedly conserved in many NPVs (15), suggesting some common function(s) of the encoded proteins. Indeed, deletion of the ac53 gene in AcMNPV prevented assembly of nucleocapsids, and instead masses of electron-lucent tubular structures were produced (50). These structures show parameters similar to those observed in our study, such as the diameter and variability in length (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we hypothesize that VP1054 and AC53 may work in concert to package viral DNA into progeny capsids to form mature nucleocapsids.

Surprising findings were obtained by in silico analyses, in which sequence similarity between baculovirus VP1054 and cellular PURα proteins was revealed (Fig. 5 and 6). The cellular PURα is a key multifunctional protein involved in many cellular events (see references 47 and 48 for reviews). PURα binds to both single-stranded DNA and RNA, and its preferred recognition sequence is composed of GGN repeats, where N is an arbitrary nucleotide. There is strong evidence that host PURα participates in pathogenesis of some viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (51–53) and human JC virus (JCV) (54, 55). Until now, no PURα-like proteins had been reported for any viral genome. Since PURα proteins are typical prerequisites of all multicellular organisms, it is more than evident that baculovirus acquired and adapted a host gene encoding PURα to make VP1054, a baculovirus-encoded protein essential for virus progeny production.

We mapped the distribution of putative recognition sites (GGN repeats) of the baculovirus-encoded PURα-like protein VP1054 in baculoviral genomes (Fig. 7 and 8) and showed that such GGN repeats are unequally distributed in the baculovirus genomes, tending to cluster in proximity to the major occlusion body protein-coding gene. We performed in vitro EMSAs showing that VP1054 is indeed capable of binding to these GGN repeats (Fig. 9). This nucleic acid-binding activity of the VP1054 is likely mediated by putative PUR-II-like domain, as demonstrated by its mutagenesis (Fig. 9C). In AcMNPV, there are two main (GGN)n clusters, both located in the essential p78/83 ORF. The protein encoded by this ORF shows sequence homology to and shares functional properties with the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), and it is required for the movement of the nucleocapsid to the cell nucleus after virus entry (56, 57). The further analysis of these GGN-rich islands, especially their requirement for viral DNA encapsidation, is hampered, since the GGN sequences are part of PRDs in the p78/83 ORF. Hence, no synonymous mutations can be generated without affecting the PRDs of the baculovirus WASP-like protein, which were shown to be critical for proper actin polymerization by WASPs (58). As a consequence, it also remains unclear whether VP1054 possesses other biological properties. One may think of abilities of DNA duplex unwinding and uncoiling of circular covalently closed DNA, functions previously described for cellular PURα proteins (59, 60). Nevertheless, our data provide evidence that baculoviruses constitute a unique group of viruses, which acquired and adapted a cellular PURα protein for their own viral needs.

It is known that the genomes of some DNA viruses, like polyomaviruses and adenoviruses, contain so-called encapsidation signal sequences, which are crucial for the recognition and packaging into progeny virions (11–13), but so far, there has been no indication of how baculovirus DNA is recognized to be packaged into preassembled capsid tubules to form mature nucleocapsids. If we adopt the hypothesis that there are analogous encapsidation signals in baculovirus genomes, logically, such a putative sequence should be present in all DNA molecules, which are competent to be encapsidated. It is widely known that during serial passage of AcMNPV in bioreactors, so-called defective interfering particles (DIPs) are produced (61, 62). These DIPs result from genetic alterations, in which up to 43% of the genetic information may be lost, including essential genes such as DNA polymerase genes (61). Therefore, DIPs can be propagated only in the presence of the standard virus, which complements the deleted essential gene functions. Nevertheless, according to our theory, the altered genomes of DIPs should still contain at least one encapsidation signal sequence, which mediates their packaging into capsids. Recently, Giri and coworkers (63) performed mapping of putative recombination sites during the genesis of AcMNPV DIPs. According to their findings, there are two main parts of the genome, which may be removed in DIPs, as schematically depicted in Fig. 10. On the other hand, a genetic element encompassing homologous regions hr1 and hr1a appears to be always present in both the standard and altered genomes (DIPs). Interestingly, between these two hr elements the GGN-rich sequence is located within the p78/83 gene, which was shown to be recognized by VP1054 (Fig. 9). Therefore, we speculate that this GGN-rich sequence, likely in cooperation with the hr1 and hr1a elements, may play an important role in the recognition of target DNA to be packaged into progeny nucleocapsids.

Fig 10.

Baculovirus encapsidation-competent DNA contains GGN-rich islands. Shown is a schematic diagram of the AcMNPV genome with positions of the hr elements (hr1, hr1a, hr2, hr3, hr4a, hr4b, and hr5), the GGN-rich island (GGN)n, and putative recombination sites during DIP generation (orange semicircles) indicated. Regions which often have deletions of DIPs are indicated by orange dotted lines. Sequences that are common for both the infectious BV virions and DIPs are depicted by orange lines terminated by orange circles.

Collectively, our results point to an ancestral host as the evolutionary origin of the baculovirus VP1054 protein and reveal its nucleic acid-binding activity, in a GGN repeat-specific manner. We further identified GGN-rich islands as the putative VP1054-binding sites, which are hidden in crucial amino acid residues encoded by the essential p78/83 ORF in the AcMNPV genome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to René Lai Kuen (Université Paris Descartes, France) for kind assistance in electron microscopy, Delphine Bonnin (Généthon, France) for kind assistance with viral replication assays, and Gerline van de Glind for her help with cell culture. We also thank Lorena Passarelli (Kansas State University, USA) and Feifei Yin (Wuhan Institute of Virology, China) for the anti-VP39 and anti-GP64 antibody, respectively.

Martin Marek, Lionel Galibert, and Otto-Wilhelm Merten were financed by the project BACULOGENES of the European Union, contract no. FP6 to 037541. Monique van Oers was sponsored partially by the Program Strategic Alliances of the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences, grant 08-PSA-BD-01.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Slack J, Arif BM. 2006. The baculoviruses occlusion-derived virus: virion structure and function. Adv. Virus Res. 69:99–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Oers MM, Vlak JM. 2007. Baculovirus genomics. Curr. Drug Targets 8:1051–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Au S, Pante N. 2012. Nuclear transport of baculovirus: revealing the nuclear pore complex passage. J. Struct. Biol. 177:90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thiem SM, Miller LK. 1989. Identification, sequence, and transcriptional mapping of the major capsid protein gene of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 63:2008–2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blissard GW, Quant-Russell RL, Rohrmann GF, Beaudreau GS. 1989. Nucleotide sequence, transcriptional mapping, and temporal expression of the gene encoding p39, a major structural protein of the multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Orgyia pseudotsugata. Virology 168:354–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lanier LM, Volkman LE. 1998. Actin binding and nucleation by Autographa californica M nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 243:167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu S, Ge G, Qi Y. 2004. Ha-VP39 binding to actin and the influence of F-actin on assembly of progeny virions. Arch. Virol. 149:2187–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fraser MJ. 1986. Ultrastructural observations of virion maturation in Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus infected Spodoptera frugiperda cell cultures. J. Ultrastruct. Mol. Struct. Res. 95:189–195 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kool M, Ahrens CH, Vlak JM, Rohrmann GF. 1995. Replication of baculovirus DNA. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2103–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carstens EB. 2009. AcMNPV as a model for baculovirus DNA replication. Virol. Sin. 24:243–267 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fujisawa H, Hearing P. 1994. Structure, function and specificity of the DNA packaging signals in double-stranded DNA viruses. Semin. Virol. 5:5–13 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hammarskjöld ML, Winberg G. 1980. Encapsidation of adenovirus 16 DNA is directed by a small DNA sequence at the left end of the genome. Cell 20:787–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oppenheim A, Sandalon Z, Peleg A, Shaul O, Nicolis S, Ottolenghi S. 1992. A cis-acting DNA signal for encapsidation of simian virus 40. J. Virol. 66:5320–5328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hodge PD, Stow ND. 2001. Effects of mutations within the herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA encapsidation signal on packaging efficiency. J. Virol. 75:8977–8986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cohen DPA, Marek M, Davies BG, Vlak JM, van Oers MM. 2009. Encyclopedia of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus genes. Virol. Sin. 24:359–414 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vanarsdall AL, Okano K, Rohrmann GF. 2006. Characterization of the role of very late expression factor 1 in baculovirus capsid structure and DNA processing. J. Virol. 80:1724–1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marek M, Merten Galibert O-WL, Vlak JM, van Oers MM. 2011. Baculovirus VP80 protein and the F-actin cytoskeleton interact and connect the viral replication factory with the nuclear periphery. J. Virol. 85:5350–5362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marek M, Merten Francis-Devaraj O-WF, van Oers MM. 2012. Essential C-terminal region of the baculovirus minor capsid protein VP80 binds DNA. J. Virol. 86:1728–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu W, Liang H, Kan J, Liu C, Yuan M, Liang C, Yang K, Pang Y. 2008. Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus 38K is a novel nucleocapsid protein that interacts with VP1054, VP39, VP80, and itself. J. Virol. 82:12356–12364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luckow VA, Lee SC, Barry GF, Olins PO. 1993. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 67:4566–4579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marek M, van Oers MM, Devaraj FF, Vlak JM, Merten O-W. 2011. Engineering of baculovirus vectors for the manufacture of virion-free biopharmaceuticals. Biotech. Bioeng. 108:1056–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lung O, Westenberg M, Vlak JM, Zuidema D, Blissard GW. 2002. Pseudotyping Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV): F proteins from group II NPVs are functionally analogous to AcMNPV GP64. J. Virol. 76:5729–5736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suzuki N, Nonaka H, Tsuge Y, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2005. New multiple-deletion method for the Corynebacterium glutamicum genome, using a mutant lox sequence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8472–8480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Lent JWM, Groenen JTM, Klinge-Roode EC, Rohrmann GF, Zuidema D, Vlak JM. 1990. Localization of the 34 kDa polyhedron envelope protein in Spodoptera frugiperda cells infected with Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Arch. Virol. 111:103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braunagel SC, Summers MD. 1994. Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus, PDV, and ECV viral envelopes and nucleocapsids: structural proteins, antigens, lipid and fatty acid profiles. Virology 202:315–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang M, Yin F, Shen S, Tan Y, Deng F, Vlak JM, Hu Z, Wang H. 2010. Partial functional rescue of Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus infectivity by replacement of F protein with GP64 from Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Virol. 84:11504–11514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. 2011. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D32–D37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Altschul S, Madden T, Schaffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. 2009. SMART 6: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D229–D232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. 2009. Jalview Version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25:1189–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596–1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bjellqvist B, Basse B, Olsen E, Celis JE. 1994. Reference points for comparisons of two-dimensional maps of proteins from different human cell types defined in a pH scale where isoelectric points correlate with polypeptide compositions. Electrophoresis 15:529–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. 2003. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3784–3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Graebsch A, Roche S, Niessing D. 2009. X-ray structure of Pur-α reveals a Whirly-like fold and an unusual nucleic-acid binding surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:18521–18526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fiser A, Sali A. 2003. MODELLER: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol. 374:461–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laskowski RA, Macarthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. 1993. PROCHECK—a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Melo F, Feytmans E. 1998. Assessing protein structures with a non-local atomic interaction energy. J. Mol. Biol. 277:1141–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ashkenazy H, Erez E, Martz E, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. 2010. ConSurf 2010: calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:W529–W533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Holm L, Kääriäinen S, Wilton C, Plewczynski D. 2006. Using Dali for structural comparison of proteins. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 14:5.5.1–5.5.24. 10.1002/0471250953.bi0505s14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Herniou EA, Jehle JA. 2007. Baculovirus phylogeny and evolution. Curr. Drug Targets 8:1043–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang R, Deng F, Hou D, Zhao Y, Guo L, Wang H, Hu Z. 2010. Proteomics of the Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus budded virions. J. Virol. 84:7233–7242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Braunagel SC, Russell WK, Rosas-Acosta G, Russell DH, Summers MD. 2003. Determination of the protein composition of the occlusion-derived virus of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:9797–9802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luckow VA. 1993. Baculovirus systems for the expression of human gene products. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 4:564–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heger A, Holm L. 2000. Rapid automatic detection and alignment of repeats in protein sequences. Proteins 41:224–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. White MK, Johnson EM, Khalili K. 2009. Multiple roles for Purα in cellular and viral regulation. Cell Cycle 8:414–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gallia GL, Johnson EM, Khalili K. 2000. Purα: a multifunctional single-stranded DNA- and RNA-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3197–3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Olszewski J, Miller LK. 1997. Identification and characterization of a baculovirus structural protein, VP1054, required for nucleocapsid formation. J. Virol. 71:5040–5050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu C, Li Z, Wu W, Li L, Yuan M, Pan L, Yang K, Pang Y. 2008. Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus ac53 plays a role in nucleocapsid assembly. Virology 382:59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wortman MJ, Krachmarov CP, Kim JH, Gordon RG, Chepenik LG, Brady JN, Gallia GL, Khalili K, Johnson EM. 2000. Interaction of HIV-1 Tat with Purα in nuclei of human glial cells: characterization of RNA-mediated protein-protein binding. J. Cell. Biochem. 77:65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gallia GL, Darbinian N, Tretiakova A, Ansari SA, Rappaport J, Brady J, Wortman MJ, Johnson EM, Khalili K. 1999. Association of HIV-1 Tat with the cellular protein, Purα, is mediated by RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:11572–11577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang H, White MK, Kaminski R, Darbinian N, Amini S, Johnson EM, Khalili K, Rappaport J. 2008. Role of Purα in the modulation of homologous recombination-directed DNA repair by HIV-1 Tat. Anticancer Res. 28:1441–1447 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chang CF, Gallia GL, Muralidharan V, Chen NN, Zoltick P, Johnson E, Khalili K. 1996. Evidence that replication of human neurotropic JC virus DNA in glial cells is regulated by the sequence-specific single-stranded DNA-binding protein Pur alpha. J. Virol. 70:4150–4156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chen NN, Chang CF, Gallia GL, Kerr DA, Johnson EM, Krachmarov CP, Barr SM, Frisque RJ, Bollag B, Khalili K. 1995. Cooperative action of cellular proteins YB-1 and Pur alpha with the tumor antigen of the human JC polyomavirus determines their interaction with the viral lytic control element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:1087–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ohkawa T, Volkman LE, Welch MD. 2010. Actin-based motility drives baculovirus transit to the nucleus and cell surface. J. Cell Biol. 190:187–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Machesky LM, Insall RH, Volkman LE. 2001. WASP homology sequences in baculoviruses. Trends Cell Biol. 11:286–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Castellano F, Clainche CL, Patin D, Carlier MF, Chavrier P. 2001. A WASp-VASP complex regulates actin polymerization at the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 20:5603–5614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wortman MJ, Johnson EM, Bergemann AD. 2005. Mechanism of DNA binding and localized strand separation by Pur-alpha and comparison with Pur family member, Pur-beta. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1743:64–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Darbinian N, Gallia GL, Khalili K. 2001. Helix-destabilizing properties of the human single-stranded DNA- and RNA-binding protein Purα. J. Cell. Biochem. 80:589–595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kool M, Voncken JW, van Lier FL, Tramper J, Vlak JM. 1991. Detection and analysis of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus mutants with defective interfering properties. Virology 183:739–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pijlman GP, Dortmans JC, Vermeesch AM, Yang K, Martens DE, Goldbach RW, Vlak JM. 2002. Pivotal role of the non-hr origin of DNA replication in the genesis of defective interfering baculoviruses. J. Virol. 76:5605–5611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Giri L, Feiss MG, Bonning BC, Murhammer DW. 2012. Production of baculovirus defective interfering particles during serial passage is delayed by removing transposon target sites in fp25k. J. Gen. Virol. 93:389–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]