Abstract

The oncogenic property of the adenovirus (Ad) transforming E1A protein is linked to its capacity to induce cellular DNA synthesis which occurs as a result of its interaction with several host proteins, including pRb and p300/CBP. While the proteins that contribute to the forced induction of cellular DNA synthesis have been intensively studied, the nature of the cellular DNA replication that is induced by E1A in quiescent cells is not well understood. Here we show that E1A expression in quiescent cells leads to massive cellular DNA rereplication in late S phase. Using a single-molecule DNA fiber assay, we studied the cellular DNA replication dynamics in E1A-expressing cells. Our studies show that the DNA replication pattern is dramatically altered in E1A-expressing cells, with increased replicon length, fork velocity, and interorigin distance. The interorigin distance increased by about 3-fold, suggesting that fewer DNA replication origins are used in E1A-expressing cells. These aberrant replication events led to replication stress, as evidenced by the activation of the DNA damage response. In earlier studies, we showed that E1A induces c-Myc as a result of E1A binding to p300. Using an antisense c-Myc to block c-Myc expression, our results indicate that induction of c-Myc in E1A-expressing cells contributes to the induction of host DNA replication. Together, our results suggest that the E1A oncogene-induced cellular DNA replication stress is due to dramatically altered cellular replication events and that E1A-induced c-Myc may contribute to these events.

INTRODUCTION

The adenovirus (Ad) transforming E1A protein [a 243-amino-acid E1A protein, also referred to as small E1A protein [1, 2]) has the capacity to induce S phase in quiescent cells, and in the presence of activated ras or virus-encoded E1B19K or 55K proteins, E1A can transform rodent cells in culture (1, 2). The S-phase induction and cell transformation activities of the small E1A protein are genetically linked and are dependent on the N-terminal region of E1A binding to cellular protein complexes, including TRRAP/p400/GCN5, histone acetyltransferase p300/CBP, and the Rb family tumor suppressor proteins (1–4). E1A-Rb interactions result in the release of the progrowth E2F family transcription factors from the Rb-histone deacetylase (HDAC) repressor complexes and the induction of the S phase (1, 5). However, studies have shown that in order for E1A to induce S phase efficiently, it must bind to p300/CBP and Rb family proteins simultaneously, suggesting that E1A must also alter the functions of p300/CBP (3, 6).

Although a large number of studies have focused on the cellular proteins that contribute to the forced induction of host DNA synthesis in E1A-expressing cells, the nature of the cellular DNA that replicates in these cells is not well understood. Previous studies have shown that the E1A-expressing cells fail to undergo proper mitosis and that such cells accumulate in the S and G2/M phases (7–10). Mammalian cells contain a large number of DNA replication origins, and these origins are present in clusters. A majority of the replication origins fired in the early S phase in normal cells map to CG islands in the vicinity of the polymerase II (Pol II) promoters (11–13). In eukaryotic cells, the initiation of DNA replication occurs in a stepwise manner, with, first, the Orc complex binding to origins. Cdt1 and Cdc6 then bind to Orc followed by the MCM2 to -7 helicase complex to form the prereplicative complex (pre-RC), a step referred to as the “licensing” of chromatin (14–17). Entry into S phase is dependent on the activation of pre-RC, which is accomplished by several proteins, including Cdc7 and Cdk2 kinases, Cdc45, and the GINS complex. With Cdc45 and GINS as accessory factors, MCM helicase unwinds DNA, followed by recruitment of the replication machinery to start DNA replication (18). As the MCM helicase complex moves away from the origins, pre-RCs are disassembled. Cdt1 is then degraded by proteosomal degradation to prevent origin rereplication, and chain elongation ensues (19, 20). Because E1A induces the synthesis of several replication initiation proteins to high levels (this report), activates E2F in the absence of mitogen stimulation (5), and also alters the properties of some of the important chromatin-modifying proteins, it has the potential to deregulate cellular DNA replication at many levels.

In this paper, we show that several key replication initiation factors (described above) are present at much higher levels in E1A-expressing cells than in serum-stimulated cells. These proteins also bind to chromatin at significantly higher levels in E1A-expressing cells, indicating increased replication initiation activity. Using the single-molecule DNA combing assay (21, 22), we compared the cellular DNA replication events in E1A-expressing quiescent cells with those of growth-stimulated normal cells. Our results show that E1A induces dramatic changes in the dynamics of cellular DNA replication and that the E1A-expressing cells appear to be firing fewer replication origins in a single replication cluster than normal cells. Importantly, in the late S phase, cellular DNA undergoes massive rereplication. These aberrant DNA replication events induce replication stress, as evidenced by the activation of the DNA damage response (DDR). In earlier studies, we showed that E1A induces c-Myc (referred to as Myc here) by binding to p300, which is a part of a tripartite repressor complex that keeps Myc in a repressed state in quiescent cells (23–26). Here we show that when induction of Myc is blocked by an antisense Myc, induction of the S phase is significantly reduced. This paper is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to report the analysis of the cellular DNA replication events induced by this widely studied model viral oncogene and the role of Myc in this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Growth conditions for the MCF10A cells were as described previously (23, 25). Viruses expressing the small E1A protein (dl1500; see reference 27), beta-galactosidase (Adb-gal), and Myc antisense (AS) (AdASMyc) sequences have previously been described (23). Myc AS sequences are expressed from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in the E1A region. AdM4 virus expresses the luciferase reporter gene in the E1A region and transcribed from the minimal CMV promoter sequences that are linked to 4 copies of the Myc binding sites (25). AdΔM4 is identical to AdM4 except that the 4 copies of the Myc binding sites are mutated (25).

Microarray analysis.

MCF10A cells were serum starved for 36 h followed by infection with the indicated viruses for 16 h, and RNA was isolated using a RNAeasy total RNA isolation kit (Qiagen). The RNA purification included an on-column DNase digestion step. The quality of RNA was assessed by running the samples on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100), and the estimation of the yield was done by NanoDrop spectroscopy (N-1000 spectrophotometer; Nanodrop Technologies). RNA samples with an RNA integrity number (RIN) of 10 were used for labeling. An Illumina TotalPrep RNA amplification kit (Ambion) was used to generate biotinylated cRNA from the total RNA. Briefly, 300 ng total RNA was reverse transcribed to synthesize first- and second-strand cDNA. The cDNA was purified and used in an in vitro transcription reaction to make biotinylated labeled cRNA. The quality and size distribution of the labeled cRNAs were evaluated by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. A 1.5-μg volume of amplified labeled cRNA was hybridized to an Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip array for 17 h at 58°C. Scanning of the chips was done on the BeadArray Reader from Illumina. Raw data were extracted using Beadstudio software from Illumina. Quality checks and the probe-level processing of the Illumina microarray data were performed with the R Bioconductor lumi package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/lumi.html). The data processing also included a normalization procedure utilizing a quantile normalization method (28) to reduce the obscuring variations between microarrays which might be introduced during the processes of sample preparation, manufacturing, fluorescence labeling, hybridization, and/or scanning. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis were performed on the normalized signal data to assess the sample relationship and variability. Probes absent in all samples were filtered out in the downstream analysis. Differential gene expression levels under the different conditions were assessed by a statistical linear model analysis using the Bioconductor limma package, in which an empirical Bayes method is used to moderate the standard errors of the estimated log-fold changes of gene expression, resulting in more stable inference and improved power, especially for experiments with small numbers of microarrays (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) (29). The moderated t-statistic P values derived from the limma analysis described above were further adjusted for multiple testing by the method of Benjamini and Hochberg to control the false-discovery rate (FDR). The lists of differentially expressed genes were obtained by the criteria of FDR < 5% and fold change cutoff > 1.5 (P < 0.05) and visualized by volcano plots. Functional analysis was performed on the differentially expressed gene lists using the R Bioconductor topGO package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/topGO.html).

DNA combing.

Cells were serum starved and then infected with the indicated viruses and pulse-labeled sequentially with 100 μM iododeoxyuridine (IdU) and 100 μM chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU) (both from Sigma) for 20 min each as described previously (21, 22). Cells were harvested, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then embedded in 1% low-melting agarose in plugs at a volume of 100 μl and a final cell concentration of 5 × 105 cells/plug. To deproteinize the genomic DNA, the agarose plugs were immersed in a suitable volume of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) and treated overnight with 1% N-lauryl sarcosyl and 1 mg/ml proteinase K (Sigma) at 50°C. The plugs were then washed in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer several times to remove the digested proteins. Agarose plugs were melted at 70°C for 20 min with 1.8 ml/plug of 100 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) (pH 6.5) (Sigma). The solution was kept at 42°C for 15 min and treated overnight with 2 μl β-agarase (New England BioLabs). The solution was transferred to a Teflon reservoir. A silane-coated coverslip (Microsurfaces Inc.) was dipped in the solution for 5 min, to allow DNA molecules to anchor to the coverslip surface, and lifted at constant speed to create an array of combed molecules. Coverslips with combed DNA were dried for 1.5 h at 60°C, and then they were incubated in 0.5 M NaOH for 10 min with gentle agitation to denature the DNA. After several quick washes in PBS, coverslips were incubated for 1 h in a humidified chamber with a 1% blocking solution (Roche) and mouse α-bromodeoxyuridine (α-BrdU) (BD PharMingen) and rat α-CldU (Axyll) antibodies. The coverslips were then washed in PBS and incubated for 20 min at 37°C with donkey α-mouse-488 (Molecular Probes) and donkey α-rat-594 (Molecular Probes) secondary antibodies. Following three washes in PBS, coverslips were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and then scanned with an inverted fluorescence microscope using a 40× objective. Images were recorded using IPLab software (BD Biosciences Bioimaging, Rockville, MD); fluorescent signals were measured using the ImageJ program (National Cancer Institute) and converted to base-pair values according to the criteria that 1 μm equals 2 kb and that, under our conditions, 1 pixel encompasses 340 bp (21, 22). Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Flow cytometry.

Cells were infected as described for the indicated time periods, harvested, and fixed in 70% ethanol. After two washes with PBS, nuclei were resuspended in 100 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma) and 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI). Flow cytometric analysis was performed in a LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD-Biosciences), and curves were deconvoluted with ModFit. For BrdU incorporation, after fixation in 70% ethanol, cells were treated in 2 M HCl for 20 min, washed, neutralized in Na2B4O7, and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (BD PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

qPCR assays.

RNA levels for several genes shown in Fig. 1A were subjected to quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis using a QuantiFast SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA was transcribed from 2 μg of RNA isolated from MCF10A cells infected with various viruses for the time periods indicated in the legend to Fig. 1 using a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen), and a 1/20 volume of the cDNA was used as a template for the qPCR assay. Reactions were carried out in a final volume of 20 μl in QuantiFast SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) using an ABI Prism 7900HT Fast real-time PCR system, and average threshold cycle (CT) values were calculated. Expression levels of RNA were normalized using a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) internal control. Fold change was calculated based on the 2−ΔΔCt method (30).

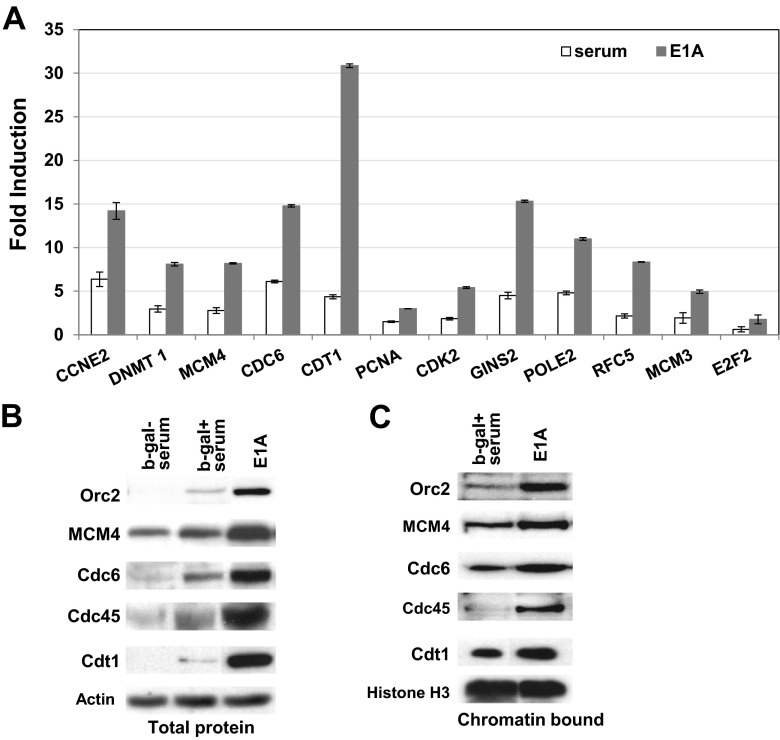

Fig 1.

Levels of mRNA of genes related to initiation of DNA replication (A) and levels of replication initiation proteins present in whole-cell extracts (B) and chromatin-bound fractions (C). (A) RNA levels as determined by qPCR. MCF10A cells (3 × 106/plate) were seeded overnight, serum starved for 32 h, and then infected with Adb-gal or AdE1A at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50. One set of plates infected with Adb-gal was stimulated with serum. Another set of Adb-gal-infected plates (control) and E1A-infected plates was maintained in serum-free medium. Cells were harvested at 16 h, the total RNA was isolated, and the mRNAs for each gene were quantified by qPCR assays as described in Materials and Methods. GAPDH was used as an internal control to normalize the values. The fold increase relative to b-gal control sample values was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. Average values (with error bars) determined for RNA samples prepared in duplicate are shown. (B) Western blot showing the levels of several replication initiation proteins expressed in serum-stimulated and E1A-expressing cells. Western blot analysis was carried out using whole-cell extracts. (C) Chromatin loading of the indicated replication initiation proteins. For chromatin-loading assays, chromatin-bound proteins were isolated as described in Materials and Methods. Virus infection conditions in the experiments represented in panels B and C were as described for panel A. In panel C, histone H3 levels indicate that equal amounts of chromatin proteins were present in the chromatin extracts. Membranes in Western blots were probed sequentially with several antibodies. The PCR primers used for the qPCR assays represented in panel A are shown in Table S3 in the supplemental material.

Preparation of whole-cell extracts and isolation of chromatin-bound proteins.

To prepare the whole-cell extracts, cells were seeded overnight at a density of 3 × 106 cells per 100-mm-diameter dish and then starved for 32 h. They were then infected with the indicated viruses, serum stimulated where appropriate, and lysed in 300 μl of buffer containing NP-40 for 15 min on ice as described earlier (26, 31). The cell extracts were clarified by centrifuging at 30,000 × g for 40 min. The supernatants were analyzed on Western blots using relevant antibodies. Chromatin-bound proteins were isolated as described by Méndez and Stillman (32). Briefly, serum-starved cells infected as described above were washed once with PBS and collected by scraping and then pelleting at 2,000 rpm using a tabletop centrifuge. The cell pellets (3.0 × 107 cells) were resuspended in 300 μl of buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.34 M sucrose, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors), Triton X-100 was then added to reach a final concentration of 0.1%, and the sample was incubated on ice for 5 min. Nuclei were collected as a pellet by low-speed centrifugation for 5 min at 3,000 × g at 4°C. Nuclei were washed once with buffer A and then lysed in 150 μl of buffer B (1 mM dithiothreitol, 3 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitors). Insoluble chromatin was collected by centrifugation at 1,700 × g for 4 min, and the pellet was washed once with buffer B. The final chromatin pellet was resuspended in Laemmli buffer and sonicated for 15 s. Proteins released from the chromatin were analyzed on Western blots using appropriate antibodies.

Other procedures.

The immunofluorescence and Western blot protocols were described in our earlier papers (33). For immunofluorescence, quiescent cells grown on coverslips were infected as indicated in the figure and then immunoreacted with a α-H2AX-specific antibody (Cell Signaling) followed by detection using α-mouse antibody conjugated with Alexafluor 488 (green). DNA was detected by staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). Sources and antibodies used in the Western immunoblot analyses were as follows: α-Cdt1 (3386S; Cell Signaling), α-MCM4 and α-Orc2 (kind gifts from B. Stillman, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory), α-Cdc6 (sc-8341; Santa Cruz), α-Cdc45 (sc-20685; Santa Cruz), α-histone H3 (05-928; Millipore), α-actin (sc-1919; Santa Cruz), α-Chk2 (2662; Cell Signaling), α-pChk2 Thre68 (2661S; Cell Signaling), α-Myc (9402S; Cell Signaling), and α-E1A (sc-430; Santa Cruz). For promoter-reporter assays, MCF10A cells were seeded overnight, starved for 32 h, and then infected with the indicated viruses. At 12 h postinfection (p.i.), the luciferase activity in cells was assayed using equal quantities of protein as described previously (24). Luciferase assays were always carried out in duplicate, starting with seeding the cells.

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data are deposited in GEO under accession number GSE47140.

RESULTS

E1A induces cell cycle progression genes in MCF10A cells.

All of the studies presented here were carried out using MCF10A cells (a nontransformed breast epithelial cell line; see reference 34). The induction of DNA synthesis by the transforming E1A protein is a basic property of E1A, and it occurs in many cell types, including those of human and rodent origin (35, 36). To determine which of the cell cycle and DNA replication genes are induced in MCF10A cells, we carried out a microarray analysis of RNA samples prepared from quiescent cells infected with an Ad variant that expresses only the transforming E1A gene (dl1500; see reference 27) (referred to as AdE1A in this report). A replication-defective Ad variant expressing the beta-galactosidase gene in the E1A region (Adb-gal) was used as a control. Infection was carried out for 16 h, a time point before cells exit G1 (as determined by flow cytometry using PI-stained cells). The RNA samples were then subjected to microarray analysis as described in Materials and Methods. We found a total of 855 genes induced in E1A-expressing cells compared to that of Adb-gal-infected cells (fold change cutoff > 1.5; P < 0.05). Gene ontology analysis indicated that a large number of these genes belonged to various pathways that lead to cell cycle progression, including initiation and elongation of DNA replication, and that several genes are involved in the DNA damage response (a partial list of these genes is shown in Table S1 and Table S2 in the supplemental material). These results are in broad agreement with two other published reports that studied the E1A-induced genes in serum-starved cells (37, 38). To confirm the induction of these genes and to get an idea as to how the induction by E1A compares with that of serum-stimulated cells, induction of 12 of the genes was compared to induction of those induced in serum-stimulated MCF10A cells using qPCR assays. As shown in Fig. 1A, all of the replication initiation genes tested in these experiments (Cdt1, Cdc6, MCM3, MCM4, GINS2, RFC5, and Cdk2; see reference 15) and genes involved in other aspects of DNA replication (DNMT1, PolE2, PCNA) and cell cycle progression genes (CCNE2 or Cyclin E2 and E2F2) were induced at levels significantly higher than those seen with serum-stimulated cells. The magnitude of induction was quite variable, ranging from 2-fold (PCNA) to 6-fold (Cdt1). It is interesting that of the E2F family members, only E2F2 was induced in these experiments. The significance of E2F2 induction in E1A-induced cell cycle progression is not clear.

Replication initiation proteins bind to chromatin at significantly higher levels in E1A-expressing cells than in serum-stimulated cells.

To determine whether increased expression of DNA replication genes promotes initiation of DNA replication, we first compared the levels of several DNA replication initiation proteins in whole-cell extracts prepared from cells infected with AdE1A with those found in serum-stimulated cells. Cells were serum starved and then infected with Adb-gal or AdE1A. One set of Adb-gal-infected plates was serum stimulated. The other sets of Adb-gal-infected plates (control) and AdE1A-infected plates were maintained in serum-free medium. All samples were harvested at 16 h after infection, whole-cell extracts were prepared, and the total proteins were analyzed by the use of Western blots for some of the key replication initiation proteins, including Cdt1, Cdc6, MCM3, MCM5, and Cdc45 (15). At this time point, both serum-stimulated and E1A-expressing cells were in the late G1 or early S phase (flow cytometric data; not shown). The Western blots shown in Fig. 1B suggest that the levels of replication initiation proteins in whole-cell extracts of E1A-expressing cells were increased significantly compared to those of serum-stimulated cells. Although a strict comparison of RNA levels with protein levels is difficult, in general, the protein levels showed a good correlation with their RNA levels (Fig. 1A). To determine the levels of binding of replication initiation proteins to chromatin, which is an indication of replication initiation activity, chromatin was prepared as described in Materials and Methods from serum-stimulated cells or cells infected with viruses as described above. The replication initiation proteins bound to chromatin were extracted and assayed for Orc2, MCM4, Cdc6, and Cdc45 by Western blots. Serum-stimulated cells infected with Adb-gal were used as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 1C, all 4 initiation proteins bound to chromatin at significantly increased levels in E1A-positive cells compared to those of serum-stimulated cells. Comparable levels of histone H3 in Fig. 1C indicate that the chromatin extracts contained comparable levels of total chromatin proteins. Overall, these results indicate that there is an increased synthesis of replication initiation proteins in E1A-expressing cells which results in increased replication initiation activity at the global level.

E1A induces massive rereplication of cellular DNA.

While E1A has been known to induce host DNA replication in a variety of quiescent cells, the nature of DNA replicated in these cells has not been analyzed before. Therefore, we monitored the S-phase progression of cells expressing E1A using flow cytometry. In the flow cytometry approaches, we used both propidium iodide (PI)-stained cells and cells pulse-labeled with bromodeoxy uridine (BrdU). Monitoring the cells using PI allows the quantification of DNA in various cell cycle fractions, whereas pulse-labeling with BrdU allows one to determine whether or not DNA is actively replicating at the time points tested.

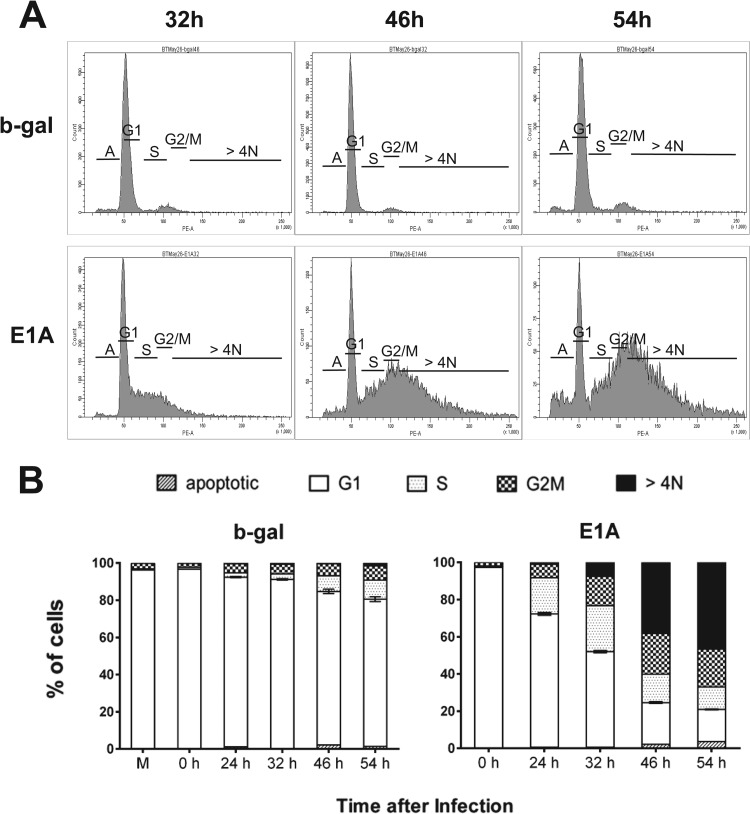

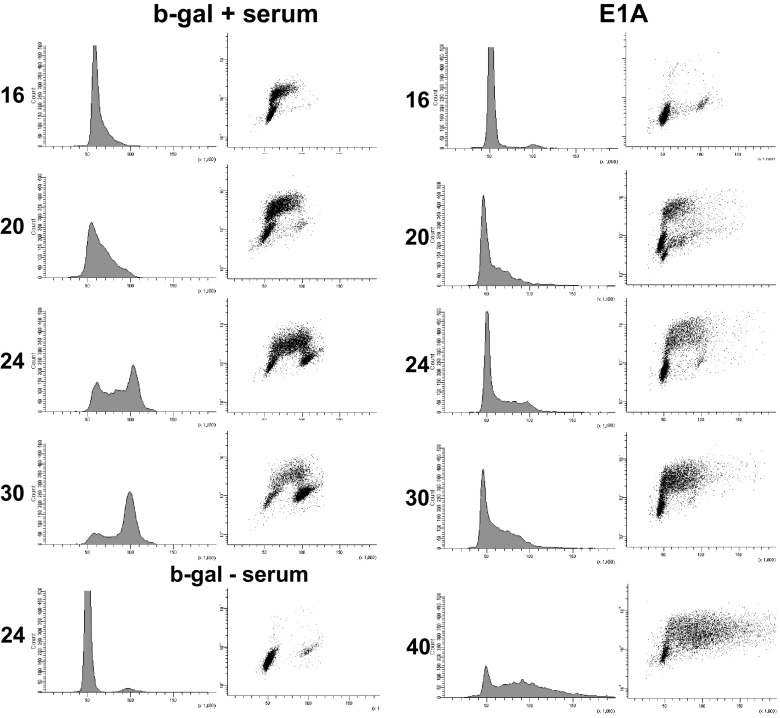

Serum-starved cells were infected with AdE1A or Adb-gal and then harvested at various time points and analyzed for their DNA content and replication by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 2, by about 32 h postinfection (p.i.), a significant percentage of E1A-expressing cells fractionated at a region that contained >4 N DNA. By 54 h p.i., the percentage of cells containing >4 N DNA content increased to about 60% in E1A-expressing cells. Serum-stimulated cells cycled normally under these conditions (data not shown). Cells were then pulse-labeled at the indicated time points with BrdU and analyzed by flow cytometry to generate BrdU versus PI staining (Fig. 3, right panels). This allowed us to determine the level of DNA replication activity in E1A-expressing cells at different stages of cell cycle progression and to further confirm whether the cells containing >4 N were still replicating. Control cells (Adb-gal plus serum) were able to reenter the cell cycle progressively and move from the early S phase (16 h post-serum stimulation) to the mid-to-late S phase (24 h) with a significant level of BrdU incorporation. At a later time point (30 h), these cells accumulated in G2 as expected. In contrast, the E1A-expressing cells were mainly in G1 at 16 h postinfection. However, at 20 to 24 h, a significant portion of these cells were incorporating BrdU into their DNA at higher levels than those of control cells. Also, while still replicating, they started accumulating with DNA content > 4 N without reaching G2. At 40 h p.i., approximately 35% of the cells were replicating their DNA with a total DNA content significantly higher than 4 N. These results suggest an ongoing DNA replication activity in cells that are undergoing rereplication. In summary, these results show that cellular DNA undergoes massive rereplication in E1A-expressing cells and that the replication origins in these cells most likely continue to fire even in late S phase.

Fig 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of PI-stained quiescent E1A-expressing cells showing rereplication of cellular DNA in the late S phase. (A) Cell cycle profiles of quiescent cells expressing E1A at various time points. Serum-starved MCF10A cells were infected with Ad viruses for various time periods as indicated and maintained in serum-free medium. Cells were harvested at indicated time points, stained with PI, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Quantification of the PI-stained cells present in various cell cycle fractions. Cell cycle profiles for 24-h samples in panel A are not shown. M, mock-infected quiescent MCF10A cells. The 0-h sample data refer to cells infected with virus for 60 min and then harvested.

Fig 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of cells pulse-labeled with BrdU, showing active DNA replication in the late S phase. Serum-starved cells were infected with Adb-gal and then serum stimulated (left) or quiescent cells were infected with AdE1A (right) for various time periods as shown and pulse-labeled for 20 min with 100 μg BrdU/ml before harvesting. Cells were analyzed for BrdU incorporation after fixation in 70% ethanol (EtOH). The BrdU-labeled cells were then processed as detailed in Materials and Methods.

E1A induces dramatically altered DNA replication dynamics.

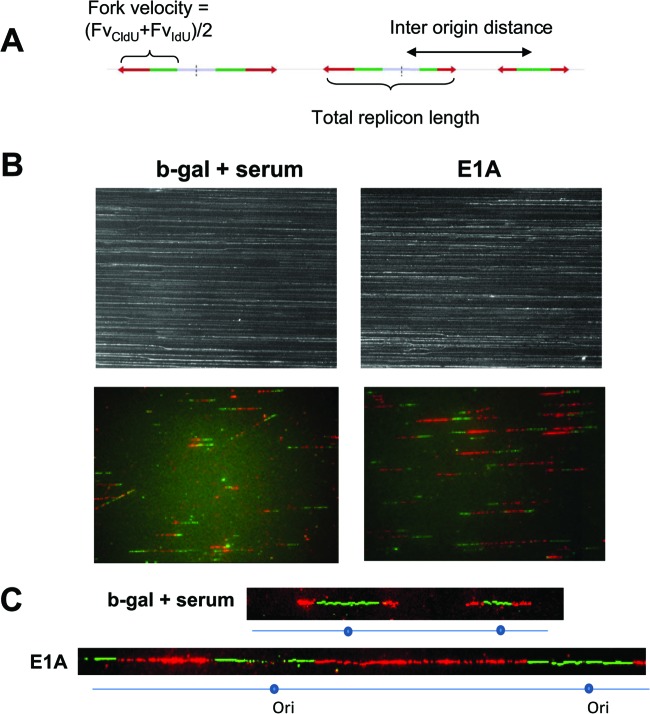

Our observations showing increased cellular replication origin firing and extensive rereplication in E1A-expressing cells suggest that the dynamics of DNA replication are significantly altered in these cells. Therefore, to understand the changes in DNA replication patterns, we took advantage of the single-molecule DNA fiber assay (also referred to as DNA combing; see references 21 and 22). This assay allows one to visualize at the single-molecule level the pattern of replication origin firing, including the fork velocity (measured as the length of the signals divided by the duration of pulses), replicon length, and the interorigin distance. Serum-starved cells infected with Adb-gal and then serum stimulated or E1A-infected cells maintained in serum-free medium were harvested at the early (20 to 24 h) and late (36 to 40 h) S phases. Cells were sequentially pulse-labeled with IdU and CldU for 20 min each before harvesting. Cells were collected and embedded in agarose plugs; genomic DNA were prepared, combed in silanized and coated coverslips, and treated as previously described (22) (see Materials and Methods). The two halogenated nucleotides incorporated into growing replication forks of the replication bubble were visualized using two different fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. Schematic images of the signals detected in a replicating DNA fiber stained with IdU (green) and CldU (red) and of the parameters analyzed in the single-molecule experiments are shown in Fig. 4A (see legend to Fig. 4A for further details). The density and quality of the combed DNA fibers (visualized by yoyo staining) prepared from the serum-stimulated and E1A-expressing cells shown in the top panel of Fig. 4B indicate that they were comparable. The bottom panel of Fig. 4B shows the IdU- and CldU-labeled tracts (replication signals). The replication signals in E1A-expressing cells appear as tracts longer than those of serum-stimulated cells, suggesting faster progression of replication forks. Examples of images of two replication tracks with origins from Adb-gal-plus-serum and E1A-expressing cells are shown in Fig. 4C (images are enlarged for clarity).

Fig 4.

DNA combing assay results, showing longer replication signals in E1A-expressing cells attributed to faster replication forks and increased interorigin distance. (A) Schematic images of the signals detected in a replicating DNA fiber stained with IdU (green) and CldU (red) and of the parameters analyzed in the single-molecule experiments. Fork velocity is measured as the average of the lengths of two consecutive signals divided by the time of the pulses. The total replicon length is the portion of DNA that replicates from one origin. The interorigin distance is the distance between two replication origins. (B) Representative images of DNA fibers (40× magnification). The top images show the density and the quality of the combed DNA fibers visualized after yoyo staining. The bottom images show the replication tracts as visualized by immunofluorescence after sequential IdU and CldU incorporation (see Materials and Methods). Serum-starved cells were infected with Adb-gal and then serum stimulated or infected with AdE1A and maintained in serum-free medium. The duration of infection was adjusted such that about 20% of each cell population was in the S phase. Cells were sequentially pulse-labeled with IdU and CldU for the last 60 min of the infection and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Replication tracts were visualized by immunofluorescence, and the images were translated to measurements as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Examples of images of two replication tracks with origins (Ori) from b-gal plus serum and E1A-expressing cells are shown (images are enlarged for clarity).

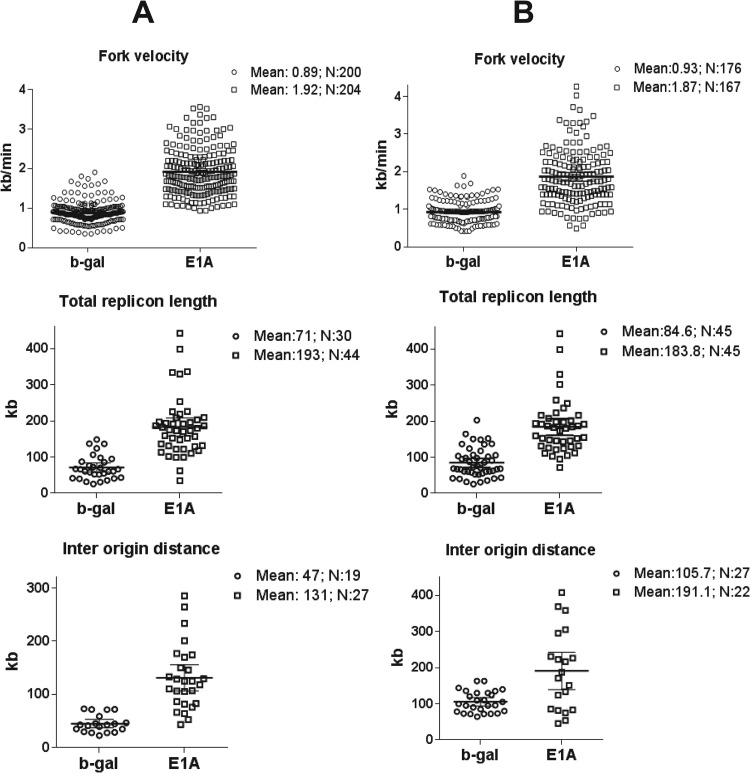

The summary of the measurements of different DNA replication parameters described above for control (serum-stimulated) and growth-arrested E1A-positive cells in early S phase is shown in Fig. 5A. The most striking results were that the replicon length, fork velocity, and interorigin distance of replicating DNAs were significantly increased in E1A-expressing cells at both early and late S phase (Fig. 5B) compared to serum-stimulated cells. For example, the mean values of fork velocity (0.88 kb/min) and total replicon length (70.8 kb) observed for serum-stimulated cells in early S phase were increased by more than 2-fold in E1A-positive cells. The mean interorigin distance of 47 kb observed in serum-stimulated cells was increased (2.7-fold) to 127 kb in E1A-positive cells. Similar differences were also found between serum-stimulated and E1A-expressing cells at late S phase (Fig. 5B). However, the mean interorigin distance increased in both control and E1A-positive cells, suggesting that as the cells approach late S phase, fewer origins are fired within each group.

Fig 5.

Summary of the DNA combing analysis, showing changes in fork velocity, replicon length, and interorigin distance of DNA replication patterns in E1A-expressing cells compared to serum-stimulated cells at both early (A) and late (B) time points. (A) Combing analysis of DNA at early S phase. Top: analysis of the fork velocity (Fv) distribution of the two samples calculated as (IdU Fv + CldU Fv)/2. Middle: analysis of the total replicon length. Bottom: analysis of the interorigin distance. For each sample, the mean value (Mean) and the number of observed events (N) are reported. The error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. Data sets were analyzed with the nonparametric test for unpaired data (Mann-Whitney). E1A-expressing cells and b-gal samples showed P < 0.001 for fork velocity and replicon length and P < 0.01 for interorigin distance. (B) Summary of DNA combing assay results determined for DNA samples isolated from cells harvested in late S phase. Details of the experiment were as described above with the exception that infection was allowed to proceed for 48 h. Top: analysis of the fork velocity distribution. Middle: analysis of the total replicon length. Bottom: analysis of the interorigin distance. Analysis of data sets and P values was performed as described for panel A.

The DNA damage response is activated in E1A-expressing cells.

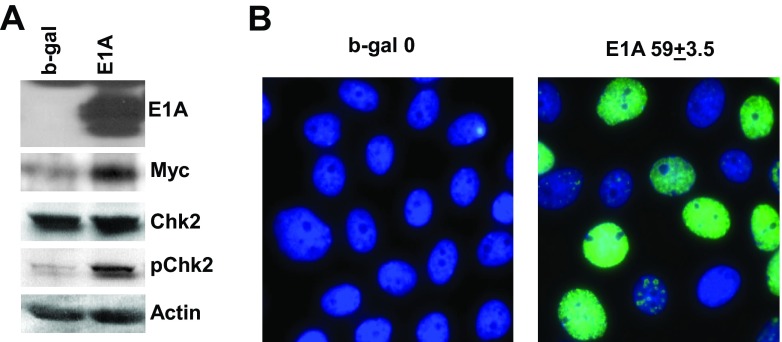

A consequence of aberrant DNA replication and the resulting replication stress and genome instability is the activation of the DNA damage response (DDR; see references 39, 40, and 41). Thus, we assayed the phosphorylation of Chk1 and Chk2, the two key regulators of DDR that are downstream targets of ATR and ATM signaling, respectively. We also assayed for the formation of γ-H2AX foci, an early step in response to double-strand breaks, using immunofluorescence techniques (33, 42). As shown in Fig. 6A, Chk2 was phosphorylated significantly in E1A-expressing cells at 24 h p.i. whereas Chk2 protein levels were not altered. This figure also shows elevated Myc levels in E1A-expressing cells, the significance of which is described below. We could not detect phosphorylation of Chk1 in E1A-expressing cells (data not shown). The number of E1A-positive cells that were found to be positive for γ-H2AX-containing foci was nearly half the control cell level (Fig. 6B). This is consistent with the number of cells in S phase (about 50%) at that time point (data not shown). Overall, these results suggest that E1A activates DNA damage response and that the ATM signaling pathway may be involved in this process.

Fig 6.

Activation of the DNA damage response in cells infected with AdE1A. (A) Phosphorylation of Chk2 in E1A-expressing cells. Quiescent MCF10A cells were infected with the indicated viruses at 50 PFU/cell and harvested after 24 h. The indicated proteins were detected in Western immunoblots using equal amounts of protein. (B) Formation of γ-H2AX-containing foci in cells expressing E1A. Quiescent cells grown on coverslips were infected as described above and then analyzed for γ-H2AX-containing foci (green) by immunofluorescence as described in Materials and Methods. DNA was detected by staining with DAPI (blue). The percentages of γ-H2AX-positive cells were scored from three different fields, and the average value ± standard deviation (SD) is shown. At least 100 cells were counted in each field.

Myc plays an important role in E1A-induced cellular DNA replication.

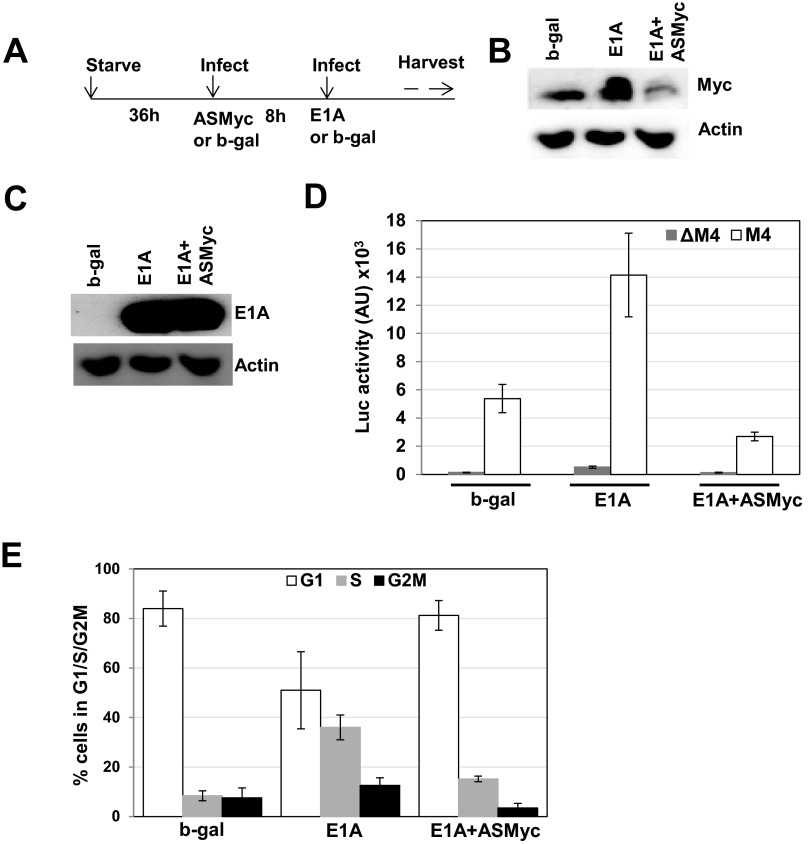

We previously showed that in quiescent cells, p300/CBP keeps Myc in a repressed state by forming a tripartite repressor complex consisting of p300, transcription factor YY1, and HDAC3 (23, 24, 26). This repressor complex binds to the upstream YY1 site of the Myc promoter to repress transcription and prevent premature G1 exit of the growth-arrested cells. E1A induces Myc by binding to p300 and dissociating the repressor complex (31, 43). Induction of Myc by this mechanism by E1A contributes to the induction of the S phase. To determine whether blocking Myc expression would inhibit S-phase induction by E1A, we infected quiescent cells with an Ad vector expressing Myc antisense sequences (AdASMyc) before AdE1A infection and cells were maintained in serum-free medium after infection (see Fig. 7A for schematic of the infection protocol). As shown in Fig. 7B (see also Fig. 6A), Myc protein levels increased in E1A-expressing cells significantly compared to that of the b-gal control. Note that MCF10A cells contain detectable basal levels of Myc (our unpublished results). Expression of antisense Myc sequences reduced the Myc protein levels to slightly less than basal levels. Expression of E1A was not affected when Myc expression was blocked by Myc AS sequences (Fig. 7C). To confirm that the reduced Myc protein levels correlated with Myc activity levels, we performed a Myc promoter-reporter assay in which the virus infection protocol included a Myc promoter-reporter virus (AdM4). In AdM4, the E1A region was replaced with the luciferase gene in which transcription was driven by the CMV minimal promoter that is linked to 4 copies of the Myc binding sites (25). To rule out the possibility that the increase in luciferase activity was due to upstream adenoviral sequences, a variant of AdM4 in which the Myc binding sites were mutated (AdΔM4; see reference 25) was assayed in parallel. Figure 7D shows that the luciferase activity increased in E1A-expressing cells by about 3.5-fold over that observed for the Adb-gal-infected cells, as is consistent with the increase in Myc protein levels. AdΔM4-infected cells showed negligible levels of luciferase activity. Myc activity in E1A-expressing cells was reduced to basal levels in the presence of Myc AS sequences. Next, we determined the effects of blocking Myc expression on S-phase induction by E1A. Serum-starved cells were infected with AdASMyc for 8 h and then infected with AdE1A, and after 24 h, the distribution of cells in the G1, S, and G2/M fractions was determined. The results shown in Fig. 7E indicate that AdASMyc inhibited the E1A-mediated S-phase induction. For example, the number of ASMyc-plus-E1A-expressing cells in both the S and G2/M fractions decreased by more than 50%, with a corresponding increase in the G1 fraction. These results suggest that in the presence of Myc antisense sequences, E1A-expressing cells exit G1 more slowly. Thus, we conclude that the E1A-induced S-phase entry is at least in part dependent on the induction of Myc.

Fig 7.

Myc and E1A protein levels in quiescent MCF10A cells infected with viruses as indicated and reversal of S-phase entry of E1A-positive cells by antisense Myc. (A) Schematic of the infection protocol. (B) Western immunoblot showing Myc protein levels in cells infected with Adb-gal, AdE1A, or AdE1A plus AdASMyc. Serum-starved cells were infected with Adb-gal (150 PFU/cell), Ad E1A (50 PFU/cell), or AdE1A after infection with AdASMyc (150 PFU/cell). Adb-gal virus was used for infection where appropriate to ensure that each group of cells received the same infection protocol. Cells were harvested 16 h after infection and then lysed, and Myc protein was detected in Western immunoblots. (C) E1A levels in serum-starved AdE1A- or AdE1A-plus-AdASMyc-infected cells at 16 h after infection. Infection conditions were as described above. (D) Myc activity levels determined using AdM4 promoter-reporter virus. Virus infections were as described above except that cells were also infected with AdM4 or AdΔM4 viruses (10 PFU/cell). AU, absorbance units. (E) Quantification of PI-stained cells in various cell cycle fractions at 24 h p.i. using flow cytometry.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we have for the first time described several novel aspects of E1A-induced cellular DNA replication, including massive rereplication of cellular DNA that occurs in late S phase, grossly altered dynamics of DNA replication patterns, and the importance of Myc in the induction of E1A-mediated S phase. Our results raise several important questions related to replication stress that is induced by a viral oncogene that is used as a paradigm cooperating oncogene.

This is the first report of a detailed analysis of the aberrant DNA replication events that occur in nontransformed human cells expressing small E1A protein. An earlier study showed that quiescent baby rat kidney cells expressing only the small E1A protein failed to undergo mitosis and that these cells accumulated in the S and G2/M phases (7). A minor portion of these cells also contained >4 N DNA. Human cells infected with Ad type 5 or type 12 expressing both E1A proteins were also shown to progress from the G1 to S phase, but progression was blocked between the G2 and M phases (8–10). A significant portion of the G2-arrested cells in these studies contained DNA copy numbers > 4 N, and such DNA replication was described as overreplication or endoreduplication. Since viruses used in these studies expressed both E1A proteins (large E1A protein is a powerful transactivator) and also contained deletions in other parts of the genome (8–10), the contribution of the small E1A protein in inducing G2 arrest in human cells is not clear. Nonetheless, these earlier studies have collectively indicated that E1A proteins interfere in the proper cell cycle progression beyond the S phase.

Our data suggest that the grossly altered DNA replication patterns, including DNA rereplication in E1A-positive cells, result in replication stress, as evidenced by the activation of a DNA damage response (DDR). In eukaryotic cells, when cells encounter DNA damage, two parallel check point signaling pathways are activated, both of which inhibit Cdc25, a positive modulator of cell cycle progression. The first signaling module, ATM/Chk2, is activated after DNA double-strand breaks, whereas the ATR/Chk1 module is activated in response to single-strand breaks or bulky lesions (40, 41). Phosphorylation of Chk2 and the formation of γ-H2AX foci (Fig. 6) indicate the existence of double-strand breaks. We could not detect phosphorylation of Chk1 in these studies. Therefore, it is not clear whether ATR pathway is activated in these cells, although studies have shown that there is cross-talk between these two kinases (40, 41).

Activation of DDR associated with aberrant host cell DNA replication appears to be a common feature of the virus-infected cells (44). The oncogenes harbored by the small DNA tumor viruses contribute at least in part to the induction of the DDR (reference 44 and this report). However, some small DNA tumor viruses take advantage of the DDR for their own replication (45, 46), whereas other viruses such as adenovirus need to inhibit the DDR for the efficient viral DNA replication (47).

Our study showed that E1A dramatically alters host DNA replication at many levels and that E1A induces extensive rereplication in late S phase. The molecular basis on which E1A induces extensive rereplication of host DNA in late S phase and the reasons for the failure of E1A-expressing cells to progress beyond S phase are as yet not clear. In metazoans, deregulation of Cdt1 in S phase is considered to be the major reason for DNA rereplication (48, 49). Cells have developed multiple mechanisms to prevent DNA rereplication. As described in the introduction, when the prereplication complex dissociates from the origin, Cdt is degraded by proteosomal degradation and thus prevents its accumulation in S phase (19, 20, 50). Cdt1 is destroyed in S phase after initiation by the CUL4-DDB1-Cdt2 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (CRL4Cdt2) via the 26S proteosome (19, 20, 50). CRL4Cdt2 also degrades two additional substrates, Set8 methylase (monomethylates H4 to K20) and p21 (implicated in nuclear export of Cdc6 in Caenorhabditis elegans; see reference 51), failure of which has been shown to contribute to origin rereplication (48). Another E3 ligase, SCFSkp2, is also known to degrade Cdt1, but the CRL4 ligase is recognized as the major contributor to Cdt1 degradation (52). As the S phase begins, Cdt1 activity is also inhibited by geminin, which is expressed at the beginning of the S phase. Geminin binds to Cdt1 and inhibits its activity, which provides an additional safety mechanism to prevent Cdt1 accumulation in S phase (53). These multiple mechanisms prevent rereplication of origins in S phase. E1A may interfere with CRL4 ligase activity by directly binding to proteins of this ligase complex. Other possibilities include E1A interference with the SCFSkp2 ligase system or functions of geminin. Studies are in progress to determine the mechanisms by which E1A induces cellular DNA rereplication.

Using a DNA combing assay, we measured three aspects of DNA replication, namely, replicon length, fork velocity, and interorigin distance. All these patterns changed dramatically in E1A-expressing cells. For example, fork velocity increased by about 2.5-fold whereas replicon length increased by about 2.7-fold. The interorigin distance increased by about 3-fold. The increase in fork velocity and related increase in interorigin distance suggest that fewer replication origins are used in E1A-expressing cells (54). A majority of the replication origins fired in the early S phase in normal cells map to CG islands in the vicinity of Pol II promoters (11–13). One possibility is that only those origins closer to the Pol II genes induced by E1A may be licensed in E1A-expressing cells. It may be that fewer genes (and hence fewer origins) are induced by E1A compared to those in serum-stimulated cells. It will be interesting to determine whether E1A influences origin selection and whether the origins fired in E1A-positive cells are a subset of the origins used in serum-stimulated cells. Others have shown that the speed with which replication forks progress correlates with increased origin activity and inversely correlates with the number of origins activated in a replication cluster (54). It is conceivable that because fewer origins are activated in E1A-expressing cells, fork velocity is increased. Additionally, in serum-stimulated cells, synthesis of proteins involved in replication initiation and elongation is temporally controlled such that origin licensing is coordinated with fork elongation. In contrast, this temporal regulation is altered in E1A-expressing cells and the proteins involved in initiation and fork elongation may be synthesized at nonphysiological levels so that fork elongation occurs at a much higher rate. Clearly, additional experiments are needed to clarify these issues.

Release of E2F transcription factors in quiescent cells from the E2F-Rb-HDAC repressor complex has been shown to be important in E1A-induced S phase (5). However, it is not clear whether this event alone is sufficient for E1A to induce S phase, as earlier studies have shown that E1A cannot induce S phase in quiescent cells unless it also binds to p300/CBP (6). Recent structural studies support this observation (3). In our earlier studies, we showed that p300/CBP plays an important role in keeping Myc in a repressed state in quiescent cells by forming a tripartite repressor complex consisting of transcription factor YY1, p300, and HDAC3 (26). E1A binds to p300, dissociates the repressor complex, and then induces Myc. In vitro studies also supported this observation (31). In this paper, we showed that blocking the Myc induction that occurs in E1A-expressing quiescent cells significantly reduces the S-phase induction. Thus, E1A-induced Myc in quiescent cells at least in part contributes to the induction of the S phase. The mechanism by which Myc contributes to the induction of the S phase remains to be determined. Using qPCR assays, we have tried to quantify the RNA levels of many DNA replication genes in E1A-expressing cells in which Myc expression is blocked by AdASMyc. Using this approach, we could not unambiguously identify the Myc target genes in that context. Myc exerts its biological functions at many levels (55). At the transcriptional level, Myc functions as a transcription factor by binding to the cognate binding sites of the Myc target promoters (55). Higher levels of Myc in cells can also amplify transcription by binding to lower-affinity noncanonical E boxes at more distant enhancer regions (56–58). Recent studies show that Myc can also function at the level of transcriptional elongation by releasing paused transcription elongation complexes (59). Furthermore, Myc was shown to function as a DNA replication initiation factor, which is not related to its transcriptional activation function (60). Thus, Myc may function at multiple levels to induce DNA replication in E1A-expressing cells. Therefore, a combination of mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (Chip-seq) approaches may be necessary to unravel the contribution of Myc in S-phase induction. Nonetheless, data presented here show that Myc plays a significant role in the induction of DNA replication in E1A-expressing cells.

E1A has been shown to stabilize p53 through the p19Arf protein that is important in E1A-induced apoptosis (61). Studies also show that overexpression of oncogenes such as Myc induces replication stress, leading to activation of DDR that involves ATM, a protein which activates p53 (62, 63). This mechanism restrains tumor development. Thus, it is likely that E1A is using Myc to induce replication stress and activate DDR, contributing to the stabilization of p53. Proteins encoded by the Ad E1B region or activated ras may protect these cells from apoptosis to induce cell transformation. Thus, Myc may be an important player in E1A-mediated apoptosis and cell transformation, depending on the physiological context (55, 64).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are particularly grateful to Bruce Stillman for providing us with some of the antibodies used in this study, Anindya Dutta for discussion at various stages of this work, and Kathleen Rundell for helpful discussion and editing the manuscript. We are also grateful to Nadereh Zafri and Chunfa Jie of the Northwestern University Genomic Core facility for helpful discussion in the design of microarray studies.

This work was supported by NIH/NCI grants RO1CA 74403 and R21AI094296. The Genomic Core and Flow Cytometry facilities used in this study were supported by Cancer Center Support grant NCI CA060553. E.L. was supported by the Center for Cancer Research intramural program of the NCI/NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00879-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berk AJ. 2005. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene 24:7673–7685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frisch SM, Mymryk JS. 2002. Adenovirus-5 E1A: paradox and paradigm. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:441–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferreon JC, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. 2009. Structural basis for subversion of cellular control mechanisms by the adenoviral E1A oncoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:13260–13265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu X, Marmorstein R. 2007. Structure of the retinoblastoma protein bound to adenovirus E1A reveals the molecular basis for viral oncoprotein inactivation of a tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 21:2711–2716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harbour JW, Dean DC. 2000. The Rb/E2F pathway: expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev. 14:2393–2409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang HG, Moran E, Yaciuk P. 1995. E1A promotes association between p300 and pRB in multimeric complexes required for normal biological activity. J. Virol. 69:7917–7924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howe JA, Bayley ST. 1992. Effects of Ad5 E1A mutant viruses on the cell cycle in relation to the binding of cellular proteins including the retinoblastoma protein and cyclin A. Virology 186:15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grand RJ, Ibrahim AP, Taylor AM, Milner AE, Gregory CD, Gallimore PH, Turnell AS. 1998. Human cells arrest in S phase in response to adenovirus 12 E1A. Virology 244:330–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cherubini G, Petouchoff T, Grossi M, Piersanti S, Cundari E, Saggio I. 2006. E1B55K-deleted adenovirus (ONYX-015) overrides G1/S and G2/M checkpoints and causes mitotic catastrophe and endoreduplication in p53-proficient normal cells. Cell Cycle 5:2244–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nichols GJ, Schaack J, Ornelles DA. 2009. Widespread phosphorylation of histone H2AX by species C adenovirus infection requires viral DNA replication. J. Virol. 83:5987–5998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cadoret JC, Meisch F, Hassan-Zadeh V, Luyten I, Guillet C, Duret L, Quesneville H, Prioleau MN. 2008. Genome-wide studies highlight indirect links between human replication origins and gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:15837–15842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karnani N, Taylor CM, Malhotra A, Dutta A. 2010. Genomic study of replication initiation in human chromosomes reveals the influence of transcription regulation and chromatin structure on origin selection. Mol. Biol. Cell 21:393–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Méchali M. 2010. Eukaryotic DNA replication origins: many choices for appropriate answers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:728–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Machida YJ, Hamlin JL, Dutta A. 2005. Right place, right time, and only once: replication initiation in metazoans. Cell 123:13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Masai H, Matsumoto S, You Z, Yoshizawa-Sugata N, Oda M. 2010. Eukaryotic chromosome DNA replication: where, when, and how? Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79:89–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alabert C, Groth A. 2012. Chromatin replication and epigenome maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Symeonidou IE, Taraviras S, Lygerou Z. 2012. Control over DNA replication in time and space. FEBS Lett. 586:2803–2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ilves I, Petojevic T, Pesavento JJ, Botchan MR. 2010. Activation of the MCM2-7 helicase by association with Cdc45 and GINS proteins. Mol. Cell 37:247–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jin J, Arias EE, Chen J, Harper JW, Walter JC. 2006. A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol. Cell 23:709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abbas T, Dutta A. 2011. CRL4Cdt2: master coordinator of cell cycle progression and genome stability. Cell Cycle 10:241–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Conti C, Caburet S, Schurra C, Bensimon A. 2001. Molecular combing. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 8:10.1–8:10.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schurra C, Bensimon A. 2009. Combing genomic DNA for structural and functional studies. Methods Mol. Biol. 464:71–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kolli S, Buchmann AM, Williams J, Weitzman S, Thimmapaya B. 2001. Antisense-mediated depletion of p300 in human cells leads to premature G1 exit and up-regulation of c-MYC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:4646–4651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rajabi HN, Baluchamy S, Kolli S, Nag A, Srinivas R, Raychaudhuri P, Thimmapaya B. 2005. Effects of depletion of CREB-binding protein on c-Myc regulation and cell cycle G1-S transition. J. Biol. Chem. 280:361–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baluchamy S, Rajabi HN, Thimmapaya R, Navaraj A, Thimmapaya B. 2003. Repression of c-Myc and inhibition of G1 exit in cells conditionally overexpressing p300 that is not dependent on its histone acetyltransferase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:9524–9529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sankar N, Baluchamy S, Kadeppagari RK, Singhal G, Weitzman S, Thimmapaya B. 2008. p300 provides a corepressor function by cooperating with YY1 and HDAC3 to repress c-Myc. Oncogene 27:5717–5728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Montell C, Fisher EF, Caruthers MH, Berk AJ. 1982. Resolving the functions of overlapping viral genes by site-specific mutagenesis at a mRNA splice site. Nature 295:380–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19:185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smyth GK. 2004. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3:Article3. 10.2202/1544-6115.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔ Ct) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kadeppagari RK, Sankar N, Thimmapaya B. 2009. Adenovirus transforming protein E1A induces c-Myc in quiescent cells by a novel mechanism. J. Virol. 83:4810–4822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Méndez J, Stillman B. 2000. Chromatin association of human origin recognition complex, cdc6, and minichromosome maintenance proteins during the cell cycle: assembly of prereplication complexes in late mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8602–8612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sankar N, Kadeppagari RK, Thimmapaya B. 2009. c-Myc-induced aberrant DNA synthesis and activation of DNA damage response in p300 knockdown cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284:15193–15205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soule HD, Maloney TM, Wolman SR, Peterson WD, Jr, Brenz R, McGrath CM, Russo J, Pauley RJ, Jones RF, Brooks SC. 1990. Isolation and characterization of a spontaneously immortalized human breast epithelial cell line, MCF-10. Cancer Res. 50:6075–6086 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mymryk JS, Bayley ST. 1993. Multiple pathways for gene activation in rodent cells by the smaller adenovirus 5 E1A protein and their relevance to growth and transformation. J. Gen. Virol. 74:2131–2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moran E. 1994. Cell growth control mechanisms reflected through protein interactions with the adenovirus E1A gene products. Semin. Virol. 5:327–340 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferrari R, Pellegrini M, Horwitz GA, Xie W, Berk AJ, Kurdistani SK. 2008. Epigenetic reprogramming by adenovirus e1a. Science 321:1086–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dazard JE, Zhang K, Sha J, Yasin O, Cai L, Nguyen C, Ghosh M, Bongorno J, Harter ML. 2011. The dynamics of E1A in regulating networks and canonical pathways in quiescent cells. BMC Res. Notes 4:160. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Branzei D, Foiani M. 2010. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:208–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reinhardt HC, Yaffe MB. 2009. Kinases that control the cell cycle in response to DNA damage: Chk1, Chk2, and MK2. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21:245–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. 2010. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 108:73–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shiloh Y. 2006. The ATM-mediated DNA-damage response: taking shape. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:402–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baluchamy S, Sankar N, Navaraj A, Moran E, Thimmapaya B. 2007. Relationship between E1A binding to cellular proteins, c-myc activation and S-phase induction. Oncogene 26:781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Turnell AS, Grand RJ. 2012. DNA viruses and the cellular DNA-damage response. J. Gen. Virol. 93:2076–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jiang M, Zhao L, Gamez M, Imperiale MJ. 2012. Roles of ATM and ATR-mediated DNA damage responses during lytic BK polyomavirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002898. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sowd GA, Li NY, Fanning E. 2013. ATM and ATR activities maintain replication fork integrity during SV40 chromatin replication. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003283. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stracker TH, Carson CT, Weitzman MD. 2002. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature 418:348–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hook SS, Lin JJ, Dutta A. 2007. Mechanisms to control rereplication and implications for cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19:663–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Blow JJ, Dutta A. 2005. Preventing re-replication of chromosomal DNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:476–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Havens CG, Walter JC. 2011. Mechanism of CRL4(Cdt2), a PCNA-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase. Genes Dev. 25:1568–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim J, Feng H, Kipreos ET. 2007. C. elegans CUL-4 prevents rereplication by promoting the nuclear export of CDC-6 via a CKI-1-dependent pathway. Curr. Biol. 17:966–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nishitani H, Sugimoto N, Roukos V, Nakanishi Y, Saijo M, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T, Nakayama KI, Nakayama K, Fujita M, Lygerou Z, Nishimoto T. 2006. Two E3 ubiquitin ligases, SCF-Skp2 and DDB1-Cul4, target human Cdt1 for proteolysis. EMBO J. 25:1126–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. De Marco V, Gillespie PJ, Li A, Karantzelis N, Christodoulou E, Klompmaker R, van Gerwen S, Fish A, Petoukhov MV, Iliou MS, Lygerou Z, Medema RH, Blow JJ, Svergun DI, Taraviras S, Perrakis A. 2009. Quaternary structure of the human Cdt1-Geminin complex regulates DNA replication licensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19807–19812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Conti C, Sacca B, Herrick J, Lalou C, Pommier Y, Bensimon A. 2007. Replication fork velocities at adjacent replication origins are coordinately modified during DNA replication in human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 18:3059–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dang CV. 2012. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 149:22–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin CY, Loven J, Rahl PB, Paranal RM, Burge CB, Bradner JE, Lee TI, Young RA. 2012. Transcriptional amplification in tumor cells with elevated c-Myc. Cell 151:56–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nie Z, Hu G, Wei G, Cui K, Yamane A, Resch W, Wang R, Green DR, Tessarollo L, Casellas R, Zhao K, Levens D. 2012. c-Myc is a universal amplifier of expressed genes in lymphocytes and embryonic stem cells. Cell 151:68–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Littlewood TD, Kreuzaler P, Evan GI. 2012. All things to all people. Cell 151:11–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rahl PB, Lin CY, Seila AC, Flynn RA, McCuine S, Burge CB, Sharp PA, Young RA. 2010. c-Myc regulates transcriptional pause release. Cell 141:432–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dominguez-Sola D, Ying CY, Grandori C, Ruggiero L, Chen B, Li M, Galloway DA, Gu W, Gautier J, Dalla-Favera R. 2007. Non-transcriptional control of DNA replication by c-Myc. Nature 448:445–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. de Stanchina E, McCurrach ME, Zindy F, Shieh SY, Ferbeyre G, Samuelson AV, Prives C, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Lowe SW. 1998. E1A signaling to p53 involves the p19(ARF) tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 12:2434–2442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Campaner S, Amati B. 2012. Two sides of the Myc-induced DNA damage response: from tumor suppression to tumor maintenance. Cell Div. 7:6. 10.1186/1747-1028-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Soucek L, Evan GI. 2010. The ups and downs of Myc biology. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20:91–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. 2008. Apoptotic signaling by c-MYC. Oncogene 27:6462–6472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.