Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is believed to initially infect the liver through the basolateral side of hepatocytes, where it engages attachment factors and the coreceptors CD81 and scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI). Active transport toward the apical side brings the virus in close proximity of additional entry factors, the tight junction molecules claudin-1 and occludin. HCV is also thought to propagate via cell-to-cell spread, which allows highly efficient virion delivery to neighboring cells. In this study, we compared an adapted HCV genome, clone 2, characterized by superior cell-to cell spread, to its parental genome, J6/JFH-1, with the goal of elucidating the molecular mechanisms of HCV cell-to-cell transmission. We show that CD81 levels on the donor cells influence the efficiency of cell-to-cell spread and CD81 transfer between neighboring cells correlates with the capacity of target cells to become infected. Spread of J6/JFH-1 was blocked by anti-SR-BI antibody or in cells knocked down for SR-BI, suggesting a direct role for this receptor in HCV cell-to-cell transmission. In contrast, clone 2 displayed a significantly reduced dependence on SR-BI for lateral spread. Mutations in E1 and E2 responsible for the enhanced cell-to-cell spread phenotype of clone 2 rendered cell-free virus more susceptible to antibody-mediated neutralization. Our results indicate that although HCV can lose SR-BI dependence for cell-to-cell spread, vulnerability to neutralizing antibodies may limit this evolutionary option in vivo. Combination therapies targeting both the HCV glycoproteins and SR-BI may therefore hold promise for effective control of HCV dissemination.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an enveloped, positive-sense RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family. It is a major cause of chronic liver disease, with an estimated 130 million people infected worldwide. Most carriers are not aware of their status, as HCV infection can be asymptomatic for decades. Ultimately, however, infection can progress to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and end-stage liver disease, making it the leading cause for liver transplantation in the United States (1).

Infection with HCV is characterized by an extremely high rate of chronicity (>70%) in immunocompetent hosts. Despite high titers of circulating HCV envelope-specific antibodies in infected patients, the virus efficiently manages to escape neutralization (2). The ineffectiveness of humoral responses to HCV may partly reside in the high mutation rate of the viral glycoproteins in vivo as well as in the tight association of HCV with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) components, which may shield antibody binding to virions (3–6).

HCV circulates in the bloodstream of infected individuals as lipoviral particles (LVPs). The association of HCV with host lipoproteins may represent an efficient mode of entry into liver cells. Interestingly, HCV entry is facilitated by the lipoprotein/cholesterol binding molecule scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) (7–9). The low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) (10) and the cholesterol uptake molecule NPC1L1 have also been implicated in HCV entry (11). Additionally, receptors, including CD81 (12), claudin-1 (CLDN1) (13), occludin (OCLN) (14), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (15), are used to gain access into hepatocytes.

The current model of HCV entry suggests that LVPs initially reach the liver by crossing the fenestrated endothelium and interact with attachment factors like heparan sulfates and other entry factors localized on the basolateral surface of hepatocytes, such as CD81, SR-BI, and EGFR. The spatial segregation of HCV receptors into different subcellular domains also implies subsequent organized transport of the virions toward the apical interface, where the tight junction-associated viral entry factors CLDN1 and OCLN reside (16). HCV internalization then occurs by clathrin-mediated endocytosis (17). Finally, the delivery of the virus to Rab5a-positive early endosomes (18) likely provides the acidic environment necessary to induce fusion (19).

Besides this route of virus entry, referred to as cell-free infection, direct transmission of HCV particles between neighboring cells, so called cell-to-cell spread, has also been suggested (20–22). The extent to which cell-free versus cell-to-cell transmission contributes to HCV persistence is unknown, but the latter route provides potential advantages in terms of infection efficiency and immune evasion (23, 24). Therefore, insights into what favors cell-to-cell transmission that is characterized by resistance to HCV-neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) might inform a more effective design of antiviral strategies. The viral determinants, entry factor requirements, and molecular mechanisms involved in this transmission route are still incompletely characterized. For example, it is unclear if and to what extent CD81 plays a role in HCV spread. Here, we used a panel of assays to discriminate between CD81-dependent and -independent cell-to-cell transmission routes for HCV and demonstrate that they both contribute to virus propagation in cell culture.

We previously showed that blocking SR-BI prevents both in vitro and in vivo HCV infection (7, 25). In the present study, we focused on exploring the role of SR-BI in HCV cell-to-cell transmission. Expressed mainly in the liver and steroidogenic tissues, SR-BI functions as a lipoprotein receptor, interacting with high-density lipoprotein (HDL), VLDL, and native and chemically modified LDL (oxidized LDL and acetylated LDL, respectively) (26–29). Its physiological role is to mediate the bidirectional exchange of free cholesterol (FC) and cholesteryl ester (CE): uptake of FC and CE from HDL particles and efflux of FC to lipoprotein acceptors (30). Initially implicated as an HCV receptor by its ability to bind soluble E2, SR-BI likely plays additional roles in the viral entry process that are not mediated by direct interactions with the viral envelope (9). The tight interaction of HCV with host-derived lipoproteins might provide an effective strategy to exploit some of SR-BI's physiological roles to gain hepatocyte access. HDL binding to SR-BI per se does not seem to be essential for HCV uptake (7, 31) but was found to enhance infectivity, probably by exploiting the SR-BI lipid-transfer process since the effect is abrogated by BLT-3 and BLT-4, blockers of SR-BI lipid-transfer activity (32–35).

The in vitro kinetics of cell-free HCV infection, as probed with blocking antibodies, suggests that SR-BI binds the virus early in the entry process, in a step closely linked to CD81 (36, 37). In patients undergoing liver transplantation, a characteristic decay in serum viral load is observed soon after graft reperfusion, likely due to massive viral uptake by the liver. The observed HCV RNA decay strongly correlated with the SR-BI expression levels on the donor livers, indicating that this receptor plays a major role in the initial binding of the virus (38).

Nevertheless, further investigations revealed that SR-BI also acts at a postbinding step (31). ITX-5061, a small molecule interfering with SR-BI-mediated lipid transfer, potently inhibits HCV infection at postbinding steps, suggesting that the role of SR-BI may be important not only for initiation of viral infection but also for dissemination (39). Remarkably, treatment of human liver chimeric mice with SR-BI-targeting antibodies after HCV exposure resulted in suppression of viral spread (25).

In this report, using a fluorescent cell-based reporter system to image HCV focus formation in real time (40), we provide evidence for how treatment with anti-SR-BI antibody leads to containment of HCV spread. By selecting a viral variant with enhanced cell-to-cell spread, we also identified mutations in HCV glycoproteins E1 and E2 that decreased SR-BI dependence and reduced susceptibility to SR-BI-blocking antibodies in cell-to-cell transmission. However, less SR-BI dependence incurs a cost, rendering the virus more susceptible to antibody-mediated neutralization.

These observations suggest that combination antiviral therapies targeting both cell-free and cell-to-cell transmission routes may aid control of HCV immune evasion and dissemination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and antibodies.

Huh-7.5 and 293T cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (NEAA; Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Huh-7.5/CD81-knockdown (Huh-7.5/CD81kd) cells were generated as previously described (22) and were grown in complete medium containing 6 μg/ml blasticidin (22). All cells were maintained at 37°C with humidified 5% CO2. Human anti-SR-BI (C167) and mouse anti-NS5A (clone 9E/10) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), anti-HCV (clones 3/11, CBH-5, AR3A, AR3B, and AR4A) nAbs, and a human anti-HIV Ab (B6) have been described previously (7, 19, 41–43). Anti-CD81 (clone JS-81) and anti-SR-BI (Cla-1) mAbs were purchased from BD, anti-OCLN and anti-CLDN1 mAbs were purchased from Invitrogen, and anti-β-actin was purchased from Sigma.

Plasmid constructs. (i) HCV plasmids.

J6/JFH-1 is an intragenotypic recombinant genotype 2a virus containing J6 sequences from core to NS2 (41). Clone 2 is a cell culture-adapted J6/JFH-1 derivative that was obtained by serial passages of J6/JFH-1 on Huh-7.5 cells and that acquired 12 mutations throughout the polyprotein compared to the sequence of the parental genome (44). J6/JFH-1-ΔE1E2 and clone 2-ΔE1E2 genomes have a large in-frame deletion within the E1- and E2-coding sequence (nucleotides 989 to 2041), replicate similarly to their wild-type counterparts, but do not release infectious particles. The chimeric genomes clone 2J6 E1E2 and J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2 were constructed by digesting J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 cDNAs with KpnI and MluI and exchanging the 1,505-bp fragment encoding glycoproteins E1 and E2 between the two backbones. As a result, clone 2J6 E1E2 expressed wild-type J6/JFH-1 E1 and E2 in a clone 2 background and J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2 had a J6/JFH-1 genome containing the I374L (E1) and I411V (E2) mutations from clone 2.

(ii) Lentiviral plasmids for shRNA interference.

For the generation of knockdown (kd) cell lines Huh-7.5/CLDN1kd and Huh-7.5/OCLNkd, the following short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences targeting CLDN1 (shCLDN1; 5′-GAGGTAGTGTGAATATTAA-3′) and OCLN (shOCLN; 5′-GTGAAGAGTACATGGCTGC-3′) were cloned into the shRNA expression vector pLVTHM (Addgene). An HCV-specific shRNA sequence (shHCV; 5′-CCTCAAAGAAAAACCAAAC-3′) and an irrelevant sequence not predicted to target any human transcript (shIRR; 5′-TAGCGACTAAACACATCAA-3′) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The shRNA targeting SR-BI (shSR-BI), used to generate Huh-7.5/SR-BIkd cells, has been previously described (36). The TRIP-RFP-nls-IPS plasmid encodes the red fluorescent protein (RFP) with a simian virus 40 (SV40) nuclear localization signal (nls; PKKKRKVG) fused to IPS-1 residues 462 to 540, which contain the HCV NS3-4A cleavage site and mitochondrial localization sequence (25).

Generation of HCVcc inocula.

Cell culture-derived HCV (HCVcc) stocks were prepared by electroporation of in vitro-transcribed viral RNA into Huh-7.5 or Huh-7.5/CD81kd cells. Virus was collected in 5% FBS, and titers were determined by limiting dilution assay, as described previously (41).

Generation of lentiviral pseudoparticles and transductions.

Pseudoparticles were generated by cotransfection of 293T cells with TRIP provirus, HIV gag-pol, and vesicular stomatitis virus envelope protein G (VSV-G) plasmids, as previously described (40). Huh-7.5 and Huh-7.5/CD81kd cells were transduced 2 days postplating by incubation for 6 h at 37°C with stocks diluted 1:3 in complete medium supplemented with 4 μg/ml Polybrene and 20 mM HEPES.

HCV infection assays.

For cell-free infection experiments, cells were incubated with HCVcc inocula at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 6 h, and then washed and replenished with fresh medium. To inhibit cell-free infection, anti-CD81 (JS-81) or anti-SR-BI (C167) mAbs were preincubated with Huh-7.5 cells for 1 h at 37°C, while HCV nAbs (3/11, CBH-5, AR3A, AR3B, and AR4A) were preincubated with HCVcc supernatants for 1 h at 4°C. Anti-CD81, anti-SR-BI, and HCV nAbs were kept on cultures until the viral inoculum was removed. The results of the neutralization experiments were analyzed by flow cytometric analysis (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS]) after staining for HCV NS5A (9E/10) at 48 h postinfection (hpi) to measure the percentage of infected cells. Data were plotted as variable-slope dose-response curves using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0) software.

To measure direct cell-to-cell transmission, we performed cocultures between HCV-positive (HCV+) producer cells (generated by infection or electroporation) and naive Huh-7.5/CD81kd target cells transduced with the pTRIP-RFP-nls-IPS1 reporter construct (40). A fraction of the producer cells was fixed and stained for NS5A to confirm that >99% of the cells were HCV+. Producer and target cells were mixed at a 1.5:1 ratio and seeded at 1.2 × 105 cells/well into 24-well plates. The number of target cells infected was determined at 48 h postcoculturing by monitoring the nuclear translocation of RFP at the fluorescence microscope and by measuring the number of NS5A-positive (NS5A+) cells in the RFP-positive (RFP+) population by flow cytometry.

HCV focus-forming assays were performed by infecting Huh-7.5 cells with J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 (MOI, 0.01) and adding an anti-E1-E2 HCV nAb (AR4A; 0.1 μg/ml) to the cultures after removal of the inoculum to prevent de novo cell-free entry. The nAb-containing supernatant was transferred onto naive cells at the end of the assay to ensure that total inhibition of the extracellular HCV particles had been achieved. HCV infectivity was assessed by fluorescence microscopy to track the nuclear localization of the RFP cellular reporter and NS5A staining using either immunohistochemistry (IHC) or flow cytometry (FACS) as a readout.

Flow cytometric analysis.

For flow cytometric analysis, cells were harvested using AccuMax medium (eBioscience), fixed, and permeabilized with Cytofix/CytoPerm buffers (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's directions. Cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647)- or Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488)-conjugated NS5A antibody (9E10-AF647 and 9E10-AF488, respectively; 1:4,000), washed three times, and resuspended in FACS buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 3% FBS). Total and cell membrane CD81 stainings were performed using JS81-allophycocyanin (APC) antibody (1:500; BD). A BD LSR II flow cytometer and BD FACSDiva software were utilized for acquisition. Analysis of the data was performed using FlowJo software.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells were lysed at the indicated times in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, mini-EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche, Basel, Switzerland]) for 30 min on ice. Thirty micrograms of protein lysate was separated on 4 to 12% bis-Tris NuPage polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). Blots were probed with primary antibodies against OCLN (1:500; Invitrogen), CLDN1 (1:500; Invitrogen), β-actin (1:10,000; Sigma), SR-BI (1:500; Cla-1; BD Pharmingen), or NS5A (1:5,000; 9E10), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and were developed using Super Signal West Pico substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Time-lapse live-cell imaging.

Reporter cells were plated on 35-mm collagen-coated optical dishes (MatTek) and maintained in complete growth medium. Time-lapse images were captured using an LCV110 VivaView incubator microscope (Olympus) equipped with an Orca ER cooled charge-coupled-device camera using a ×20 differential inference contrast objective. Visualization of RFP in transduced cells was achieved by a solid-state 561-nm laser (Spectral Applied) and ET605/70 emission filters (Chroma) for excitation and emission of RFP fluorescence, respectively. Image acquisition and processing were performed using Metamorph (Molecular Devices) and ImageJ64 (NIH, Bethesda, MD) software, respectively.

Statistical analyses.

Experimental data were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Prism (version 5.0) software. Significant differences were identified using an unpaired two-sided Student t test and 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A Bonferroni posttest correction was used to adjust significance levels and avoid false positives where appropriate.

RESULTS

Identification of a cell culture-adapted HCV genome with increased cell-to-cell spread properties.

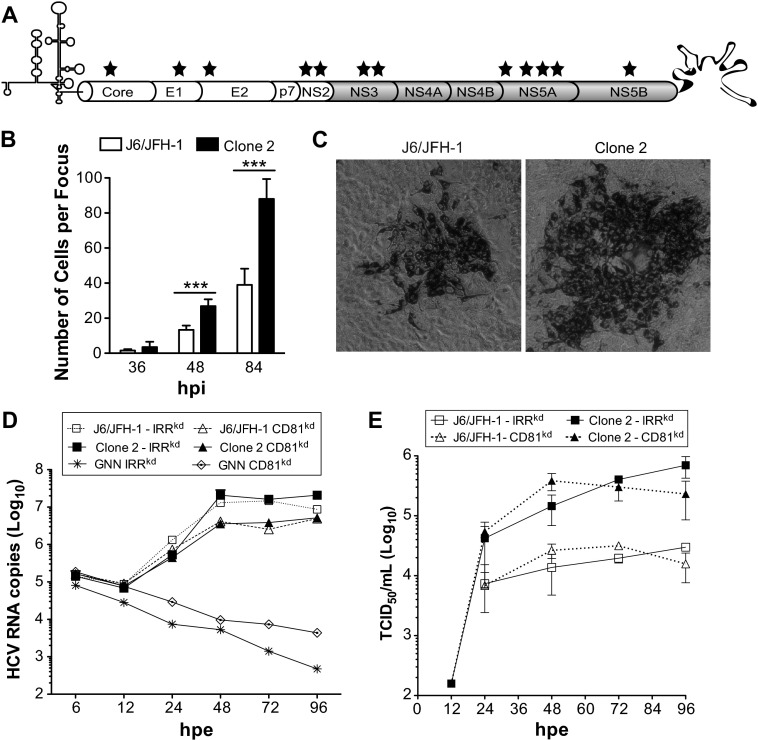

A J6/JFH-1 derivative, termed clone 2, was originally selected by serial passaging on Huh-7.5 cells (J. Loureiro, unpublished data). Compared to the parental J6/JFH-1 virus, this cell culture-adapted genome had acquired mutations throughout the polyprotein (12 in total; Fig. 1A and Table 1) and was characterized by significantly increased titers (45) and the ability to form larger foci.

Fig 1.

Increased cell-to-cell spread of cell culture-adapted HCV. (A) Schematic representation of the J6/JFH-1-derived clone 2 genome with the locations of mutations indicated (stars). (B) Sizes of J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 foci formed at 36, 48, and 84 hpi on Huh-7.5 cells in the presence of HCV nAb (AR4A; 0.1 μg/ml). Means and standard deviations (SDs) from three independent experiments are shown, and values that were significantly different are indicated (***, P < 0.001). (C) Representative images of J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 foci. Huh-7.5 cells were infected and stained with anti-NS5A antibody (9E10) at 84 hpi. (D, E) Kinetics of RNA replication (D) and production of infectious virus (E) following electroporation of J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 genomes into Huh-7.5 cells encoding an irrelevant shRNA (IRRkd) or CD81kd.

Table 1.

Mutations in clone 2 relative to parental J6/JFH-1 virus

| HCV protein | Amino acid in polyprotein |

|---|---|

| Core | K78E |

| E1 | I374L |

| E2 | I411V |

| NS2 | E863G |

| NS2 | V881G |

| NS3 | P1620S |

| NS3 | E1638D |

| NS5A | L2266P |

| NS5A | L2344F |

| NS5A | Q2346P |

| NS5A | A2348V |

| NS5B | P2577S |

To quantify J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 cell-to-cell transmission properties, we infected Huh-7.5 cells at a low MOI (0.01) with either virus and examined focus size over time by counting the number of cells positive for NS5A viral antigen (Fig. 1B). The inclusion of HCV nAb (AR4A; Table 2) in the cell culture medium after removal of the viral inoculum restricted de novo cell-free HCV transmission and resulted in localized viral spread and focus formation (Fig. 1C). No significant difference in the number of infected cells per focus was observed for the two viruses at 36 hpi. However, already at 48 hpi, the size of clone 2 foci was about twice that of J6/JFH-1 foci, with an average of 27 versus 13 NS5A+ cells per focus, respectively (n = 25; Fig. 1B). At later time points (84 hpi), the relative difference between clone 2 and J6/JFH-1 foci remained constant (mean size, 88 versus 39 cells; Fig. 1B), but their growth rate seemed to have slowed, suggesting nonlinear kinetics of cell-to-cell spread for both viruses under these conditions.

Table 2.

Neutralizing activities of anti-HCV antibodies

| Antibody | Antibody EC50 (μg/ml) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J6/JFH-1 | Clone 2 | Clone 2J6 E1E2 | J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2 | |

| 3/11 | 3.0E+01 | 7.2E−01 | 5.5E+02 | 1.1E+00 |

| CBH5 | 2.3E+00 | 8.3E−01 | 3.8E+00 | 1.0E+00 |

| AR3A | 2.6E−01 | 7.0E−03 | 1.1E−01 | 2.5E−02 |

| AR3B | 5.6E−04 | 3.5E−04 | 4.7E−04 | 4.7E−04 |

| AR4A | 3.3E−05 | 4.7E−05 | 2.2E−05 | 1.4E−05 |

To further characterize J6/JFH-1 and clone 2, we measured viral replication (Fig. 1D) and production of infectious particles (Fig. 1E) after electroporation of their genomes in Huh-7.5 and Huh-7.5/CD81kd cells. RNA replication of J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 was similar and about 8-fold lower in CD81kd cells than in parental Huh-7.5 cells. However, despite comparable replication levels, clone 2 yielded about 10-fold more infectious particles than J6/JFH-1 in both cell types. Interestingly, infectious clone 2 particles could be detected in the cell culture medium at 12 h postelectroporation (hpe), suggesting faster kinetics of assembly and release of infectious virus.

Receptor requirements for cell-free infectivity with J6/JFH-1 and clone 2.

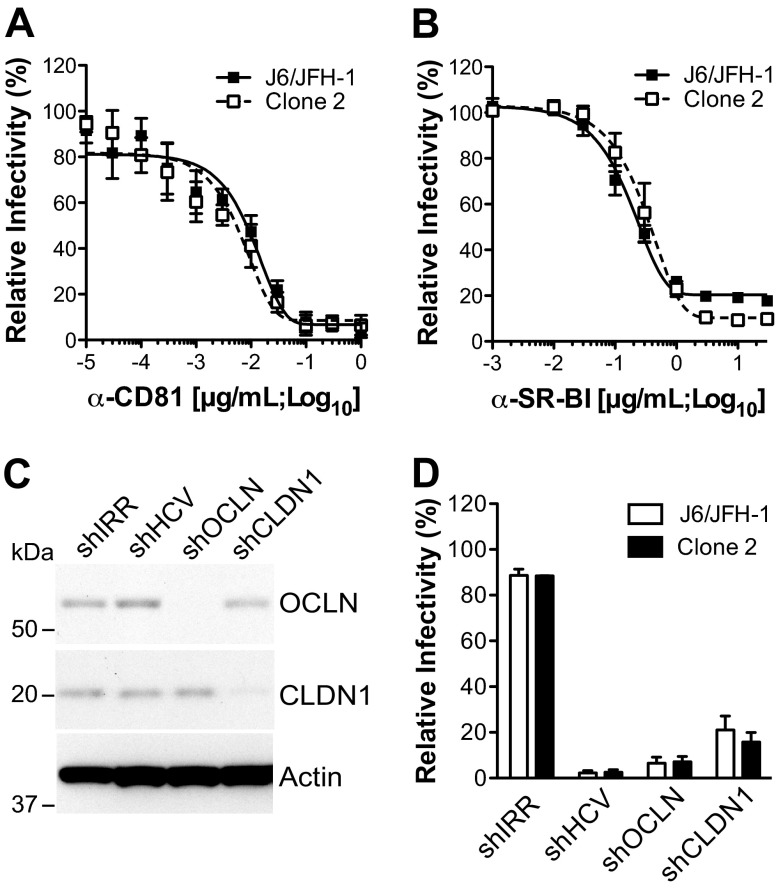

Given that clone 2 possesses two potentially adaptive mutations in the envelope glycoproteins relative to the parental J6/JFH-1 genome, I374L (in E1) and I411V (in E2), we initially addressed whether the two viruses had a similar receptor usage for cell-free entry. We focused on the HCV receptors that were previously implicated in both cell-free and cell-to-cell transmission: CD81, SR-BI, CLDN1, and OCLN. Our rationale was that clone 2 might have acquired an altered dependence on one or more of these receptors, accounting for its higher fitness and the formation of larger foci. The infectivities of both J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 were reduced in a dose-dependent manner with mAbs targeting human CD81 or SR-BI (Fig. 2A and B). The mAb 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) were comparable for J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 (for anti-CD81, 8.7E−03 versus 3.7E−03 μg/ml, respectively; for anti-SR-BI, 1.6E−01 versus 3.1E−01 μg/ml, respectively). To assess the role of CLDN1 and OCLN in mediating entry for these viruses, Huh-7.5 cells transduced with lentiviral particles encoding CLDN1- and OCLN-targeting shRNAs were utilized (Fig. 2C). In this background, where a strong, specific knockdown of CLDN1 and OCLN protein expression was obtained (Fig. 2C), a marked impairment of both J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 infection was measured, similar to what was observed for the positive control, an HCV-targeting shRNA (shHCV) (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the degree of inhibition for both receptor-targeting shRNAs was comparable between the two viruses. This indicates that the two HCV genomes, clone 2 and J6/JFH-1, which are distinct in their cell-to-cell spread properties, still require CD81, SR-BI, CLDN1, and OCLN during cell-free virus infection.

Fig 2.

Receptor requirements for cell-free infectivity with J6/JFH-1 and clone 2. (A, B) J6/JFH-1 or clone 2 cell-free infection efficiency in the presence of anti-CD81 (A) or anti-SR-BI (B) mAb. Huh-7.5 cells were preincubated with the indicated concentrations of mAb (μg/ml; log10) and infected with HCVcc in the presence of the mAb. The percentage of HCV-infected cells at 48 hpi was measured by flow cytometry using Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-NS5A antibody (9E10-AF647). MFIs obtained with isotype-matched controls were subtracted. Curves were extrapolated by fitting experimental data with GraphPad Prism (version 5.0) software. (C) Immunoblot for OCLN, CLDN1, and β-actin expression in Huh-7.5 cells expressing shIRR, shHCV, shOCLN, and shCLDN1. Cells were harvested at 72 h posttransduction, and 30 μg total cell lysate was loaded per lane. (D) Huh-7.5 cells expressing the indicated shRNAs were inoculated with J6/JFH-1 or clone 2 at an MOI of 0.1, and HCV infection frequency was measured at 48 hpi at the flow cytometer by staining the cells for NS5A with 9E10-AF647. The value for parental Huh-7.5 cells was set to 100%. Mean values and SDs from three independent experiments are plotted.

HCV cell-to-cell transmission is modulated by CD81 levels on producer cells.

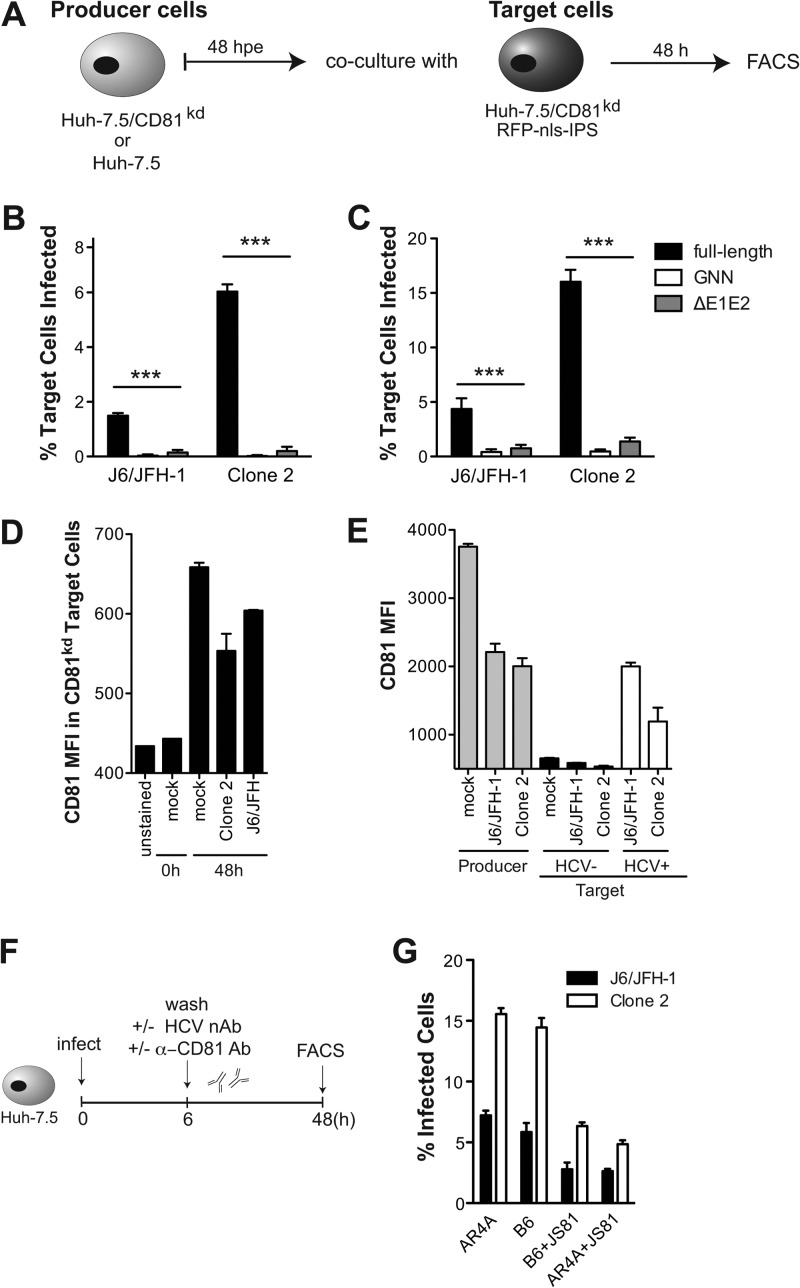

The role of CD81 in direct cell-to-cell spread of HCV is still controversial (20–22). To address CD81 involvement in cell-to-cell transmission, Huh-7.5/CD81kd cells that have undetectable levels of CD81 protein and are nonpermissive for cell-free HCV entry have been used as target cells in coculture experiments with preinfected producer cells (22, 40). However, producer cells in these experiments had normal CD81 expression levels, raising the possibility that producer CD81 might function in cell-to-cell transmission. To examine this possibility, a rigorous assay was developed where both the producer and target populations were knocked down for CD81. Target cells were distinguishable from producer cells, in that they had been transduced with the pTRIP-RFP-nls-IPS1 reporter construct prior to coculturing. The percentage of cells in the target population (RFP+) that stained positive for NS5A (NS5A+/RFP+) by FACS analysis represented a measure of the extent of HCV cell-to-cell transmission (Fig. 3A). We observed cell-to-cell spread of both J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 full-length genomes when CD81 was knocked down on both producer and target cells (Fig. 3B). Nevertheless, when CD81+ cells were used as producers, the number of infected target cells was about 2.5-fold higher (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that CD81 knockdown, while completely abolishing HCV cell-free entry, still allows virus spread between neighboring cells. Moreover, CD81 levels on producer cells do modulate the efficiency of cell-to-cell transmission. In both cases, clone 2 cell-to-cell transfer was 4-fold more efficient than J6/JFH-1 cell-to-cell transfer, indicating that CD81 is likely not responsible for clone 2's increased lateral transmission. Deletion of the viral glycoproteins (ΔE1E2) resulted in a lack of NS5A+ cells in the target population (Fig. 3B and C), demonstrating that E1 and E2 are necessary for cell-to-cell transmission of HCV, as expected (22).

Fig 3.

Effect of CD81 levels on HCV cell-to-cell transmission. (A) Schematic of coculture experiments. Producer cells (Huh-7.5/CD81kd or Huh-7.5) were cultured for 48 h after electroporation with HCV genomes before mixing with naive Huh-7.5/CD81kd/RFP-nls-IPS target cells at a 1.5:1 ratio. Cocultures were analyzed by flow cytometry 48 h later, after staining with anti-NS5A Ab. The NS5A+ cells in the RFP+ population represented infected target cells. (B, C) NS5A expression in the target cell population was analyzed by FACS to quantify HCV cell-to-cell spread. Graphs show the percentage of infected target cells when cocultured with either Huh7.5/CD81kd (B) or Huh-7.5 (C) producer cells. Full-length, polymerase-defective (GNN), and virus assembly-impaired genomes (ΔE1E2) were tested in parallel. Means and SDs from two independent experiments are shown, and values that differ significantly from the values for HCV spread obtained in the presence of the full-length genomes are indicated. ***, P < 0.001. (D) Cell surface CD81 expression on Huh-7.5/CD81kd target cells was measured by FACS prior to and at 48 h after cultivation with uninfected (mock) or J6/JFH-1- or clone 2-infected Huh-7.5 cells. MFIs of anti-CD81–APC antibody and SDs from two independent experiments are shown. (E) Cocultures between uninfected (mock) or J6/JFH-1- or clone 2-infected Huh-7.5 and naive Huh-7.5/CD81kd/RFP-nls-IPS target cells were permeabilized 48 h later and costained with anti-NS5A/AF488 and anti-CD81–APC antibodies. MFIs obtained with anti-CD81–APC in the CD81+ producer (RFP−) and CD81kd target (RFP+) populations are plotted. Target cells were further classified HCV negative (HCV−; black bars) and HCV+ (white bars) on the basis of the staining with anti-NS5A/AF488. (F) Schematic of HCV cell-to-cell spread experiments in CD81+ cultures in the presence or absence of HCV-neutralizing and anti-CD81 antibodies. (G) Percentage of infected cells obtained with the two viruses when cultures were treated postinfection (MOI, 0.1) with the indicated single antibody or combinations (each at 1 μg/ml).

To elucidate possible mechanisms of CD81 enhancement of cell-to-cell spread, we measured cell surface CD81 protein levels on CD81kd target cells prior to and 48 h after coculturing with CD81+ cells that were either naive (mock), J6/JFH-1, or clone 2 infected (Fig. 3D). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of target CD81kd cells incubated with an anti-CD81–APC antibody prior to coculture was indistinguishable from that of the unstained control. Interestingly, however, a clear staining was observed 48 h later, irrespective of whether the CD81+ population had been infected or not, suggesting that coculture itself was sufficient to promote transfer of CD81 to the target population. Figure 3E provides a closer look at total CD81 protein levels in both producer and target cells in relation to those in cells in their infected state via costaining with anti-NS5A–AF488. Our results demonstrated that the CD81kd cells that became HCV+ displayed the highest CD81 levels within the target population, similar to infected producer cells.

In a further attempt to determine the role of CD81 in HCV cell-to-cell transmission, we infected Huh-7.5 cells with J6/JFH-1 or clone 2 at a low MOI for 6 h, washed the inoculum away, and added an HCV-neutralizing antibody (AR4A), either alone or in combination with anti-CD81 antibody (JS81; Fig. 3F). The comparison of the two treatments should reveal the contribution of CD81 to HCV cell-to-cell spread when both producer and target cells express CD81 and de novo cell-free entry is inhibited by AR4A (see Fig. 6 and Table 2 for EC50 details). Interestingly, we did not observe a reduced number of HCV+ cells when AR4A was added to the culture medium postinfection compared to the number when an irrelevant, HIV-specific IgG (B6) was added. This may indicate that the majority of entry events in the second round of infection (viz., postremoval of the inoculum) is due to cell-to-cell spread rather than de novo cell-free HCV transmission. The addition of JS81 postinfection at a concentration that completely blocks cell-free entry (1 μg/ml) reduced cell-to-cell transmission only by 60% in both cases (Fig. 3G). While confirming the involvement of CD81 in HCV cell-to-cell spread, these results also raise the possibility that a CD81-independent cell-to-cell transmission route accounts for the residual 40% signal. This observation would be consistent with the difference in cell-to-cell transfer shown in Fig. 3B versus that in Fig. 3D, with the former being approximately 60% less efficient.

Fig 6.

Mutations in clone 2 E1 and E2 affect sensitivity to cell-free antibody-mediated neutralization. J6/JFH-1, clone 2, and the chimeric viruses clone 2J6 E1E2 and J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2 were preincubated with increasing concentrations (μg/ml) of HCV-specific antibodies 3/11 (A), CBH-5 (B), AR3A (C), AR3B (D), or AR4A (E) or with a human anti-HIV antibody, B6, that served as a negative control (F). The residual virus infectivity at the indicated antibody concentrations (the logarithm of the concentration of antibody is plotted on the x axis) was calculated at 3 days postinfection by NS5A staining and flow cytometric analysis. Infectivity without antibody was set to 100%. Mean values and SDs from four independent experiments are plotted.

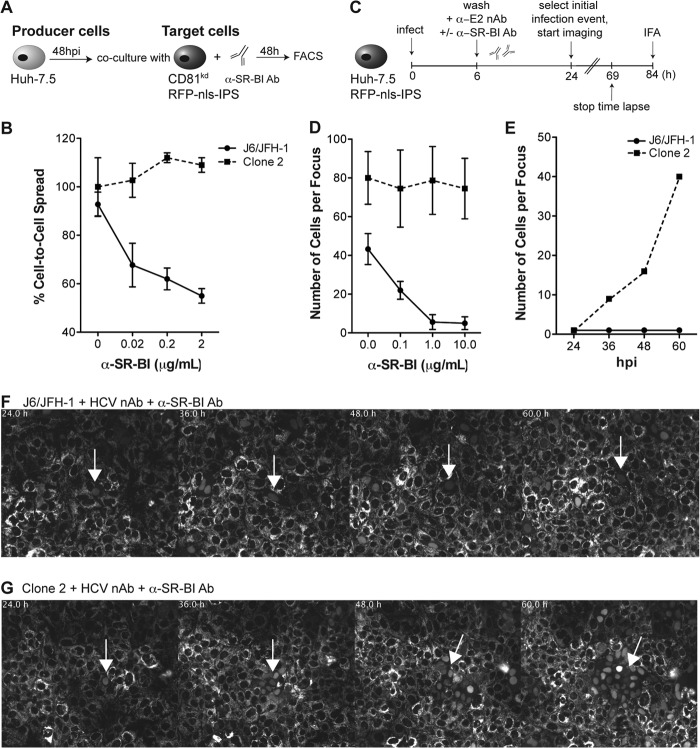

J6/JFH-1, but not clone 2, requires high levels of SR-BI for cell-to-cell spread.

To analyze the role of SR-BI in cell-to-cell transmission, we used an anti-SR-BI mAb, C167, in coculture assays and compared the degree of HCV transmission to target CD81kd cells (Fig. 4A and B). C167 binds to conformation-dependent SR-BI determinants and efficiently inhibits cell-free HCV infection, HDL binding, and SR-BI-mediated lipid transfer (7). Coculture experiments between J6/JFH-1- or clone 2-infected producer cells and CD81kd RFP+ target cells resulted in 4 to 6% and 16 to 18% target infected cells (NS5A+/RFP+), respectively. Addition of C167 to the cocultures impaired the transmission of J6/JFH-1 to target cells in a dose-dependent manner but, intriguingly, had no effect on clone 2 cell-to-cell spread (Fig. 4B). These findings prompted us to carry out HCV focus formation assays where we took advantage of the IPS1-based HCV reporter cell system previously described to measure viral spread by both live-cell microscopy and endpoint fluorescence microscopy of parallel phosphonoformic acid (PFA)-fixed cultures (Fig. 4C) (40). Huh-7.5/RFP-nls-IPS cell monolayers were infected at a low MOI (0.01) for 6 h, followed by washing and replenishing with fresh medium. HCV-neutralizing antibodies were then added to the culture medium to block de novo cell-free infection events but not cell-to-cell spread. In agreement with the IHC data shown in Fig. 1B, measuring HCV foci by tracking RFP nuclear translocation showed that the mean size of clone 2 foci was approximately twice that of J6/JFH-1 foci at 84 hpi (80 ± 16 versus 43 ± 8 infected cells per focus, respectively; Fig. 4D). Similar to the results obtained in coculture assays, we observed that addition of C167 postinfection impaired J6/JFH-1 spread in a dose-dependent manner but did not alter the size of clone 2 foci. Maximal inhibition of J6/JFH-1 spread was achieved with between 1 and 10 μg/ml of anti-SR-BI antibody, where the mean focus size was 5 ± 3 cells per focus (Fig. 4D). HCV cell-to-cell transmission was also monitored by live-cell microscopy starting at 24 hpi, when complete translocation of RFP to the nucleus could be readily detected. Areas of the dish with a single RFP+ nucleus, indicative of productive infection, were monitored for 48 h by time-lapse microscopy. Figure 4E shows the effect of the highest dose of C167 (10 μg/ml) on J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 propagation in Huh-7.5/RFP-nls-IPS cells from a representative microscopy field. The corresponding still images from the time lapse are shown as a montage in Fig. 4F and G. Video files are available in the supplemental material. Over the time course of the experiment, cells surrounding those initially infected with J6/JFH-1 very rarely became infected in the presence of C167, suggesting that the antibody blocked cell-to-cell spread (Fig. 4E and F; see Video S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast, a steady increase in the number of infected cells surrounding the initially clone 2-infected cells was observed in either the presence or absence of anti-SR-BI antibody (Fig. 4E and G; see Video S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig 4.

Impact of anti-SR-BI antibody on J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 cell-to-cell spread kinetics. (A) Schematic of coculture of HCV-infected Huh-7.5 producer cells with Huh7.5/CD81kd target reporter cells. Producer cells were preinfected with J6/JFH-1 or clone 2 virus for 48 h before mixing at a 1.5:1 ratio with uninfected Huh7.5/CD81kd/RFP-nls-IPS target cells and adding anti-SR-BI antibody. Cocultures were incubated for an additional 48 h and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) The percentage of target infected cells at increasing concentrations of SR-BI mAb (C167; 0.02, 0.2, and 2 μg/ml) was measured by FACS by gating on NS5A+/RFP+ double-positive cells. Data are expressed as the percentage of cell-to-cell spread relative to that of an isotype-matched irrelevant control antibody. Mean values and SDs from three independent experiments are plotted. (C) Schematic of HCV focus-forming assay. Huh-7.5 cells stably expressing RFP-nls-IPS were infected with J6/JFH-1 or clone 2 at a low MOI (0.01) for 6 h prior to removal of the inoculum and addition of imaging medium containing anti-E1-E2 (AR4A; 0.1 μg/ml) and anti-SR-BI (C167; 0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) antibodies. Time-lapse live-cell imaging of viral spread was started at 24 hpi, when single infected cells could be visualized by nuclear translocation of RFP, and stopped at 69 hpi. Parallel cultures were fixed and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy at 84 hpi to quantify the endpoint size of HCV foci. (D) The size of HCV foci was determined by scoring the number of RFP-positive nuclei in PFA-fixed cell monolayers at 84 hpi. The mean size and SD of 30 distinct HCV-infected cell clusters from three independent experiments are shown. (E) The number of HCV-positive cells over time from representative time-lapse live-cell imaging (see also panels F and G and Videos S1 and S2 in the supplemental material) is shown. RFP-positive nuclei from the same imaging stage position were counted at the indicated time points (hpi). (F, G) Montages of images taken from selected time points beginning at 24 hpi show the formation of J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 foci, respectively, with the highest anti-SR-BI antibody concentration tested (10 μg/ml). Images were captured every 30 min to up to 69 hpi. RFP fluorescence is shown in gray scale. Times (h) from the start of infection are shown on the top left corner, and the white arrows indicate the initially selected HCV-infected cells. See Videos S1 and S2 in the supplemental material for the full time course.

Mutations in the HCV glycoproteins modulate SR-BI requirements and sensitivity to antibody-mediated neutralization.

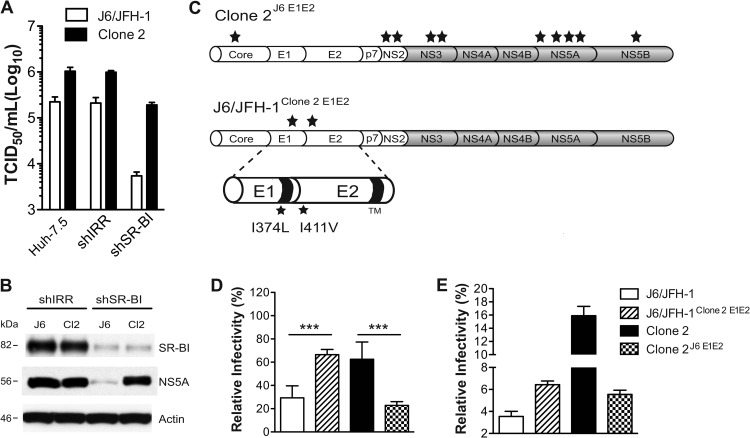

To further address the role of SR-BI in J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 propagation, we titrated the same virus stocks side-by-side on three different cell lines: parental Huh-7.5 cells and Huh-7.5 cells transduced with shIRR- or shSR-BI-encoding lentiviruses (Fig. 5A). The growth of J6/JFH-1 virus was severely compromised in Huh-7.5/SR-BIkd cells, with titers reduced 43-fold compared to those for a control cell line expressing an irrelevant shRNA (shIRR). These results are in agreement with recent findings suggesting that SR-BI expression is a limiting factor for HCV transmission (46). In contrast, however, propagation of clone 2 was much less affected in Huh-7.5/SR-BIkd cells (the 50% tissue culture infective dose [TCID50] decreased 5-fold compared to that for shIRR cells), indicating that this virus has a reduced dependence on SR-BI for propagation in vitro. The limiting dilution assay used here is developed at 72 hpi and reflects the total virus yield generated by both cell-free and cell-to-cell transmission. The residual SR-BI protein expression in SR-BIkd cells (Fig. 5B) explains why cell-free entry of both viruses can still occur to some extent. Nevertheless, the increase in the relative permissiveness of clone 2 over that of J6/JFH-1 observed with SR-B1kd cells (35-fold) compared to Huh-7.5 and shIRR-expressing Huh-7.5 cells (approximately 7-fold) suggests that silencing of SR-BI represents a factor strongly limiting J6/JFH-1 propagation in cell culture while only marginally affecting clone 2 fitness. The comparison of NS5A intracellular protein levels by immunoblot analysis in control and SR-BIkd cells infected with the two viruses confirmed a marked impairment in J6/JFH-1 propagation. In contrast, lysates obtained from clone 2-infected Huh-7.5/SR-BIkd cells had NS5A levels similar to those of the shIRR-expressing cell line (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

E1 and E2 mutations in clone 2 influence SR-BI use in cell-to-cell spread. (A) The dependence of J6/JFH-1 and clone 2 on SR-BI for propagation in cell culture was assessed by titrating the same viral supernatants on Huh-7.5 wild-type cells or Huh-7.5 cells expressing shIRR or shSR-BI. At 3 days postinoculation, virus titers (TCID50/ml) were determined. Means and SDs from two independent assays are plotted. (B) Immunoblot for SR-BI, NS5A, and β-actin in Huh-7.5 cells expressing shIRR or shSR-BI infected with either J6/JFH-1 (J6) or clone 2 (Cl2) viruses at 72 hpi. Whole-cell lysates (30 μg per lane) were loaded on a 4 to 12% bis-Tris NuPage gel. (C) Schematic representation of the chimeric viruses clone 2J6 E1E2, harboring parental J6/JFH-1 E1-E2 sequences in a clone 2 background, and J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2, a J6/JFH-1 genome bearing the clone 2 I374L (E1) and I411V (E2) mutations. Stars, approximate positions of the acquired mutations on the polyprotein. (D) Huh-7.5 cells were transduced with lentiviruses encoding shIRR or shSR-BI and challenged 48 h later with HCV (clone 2, J6/JFH-1, or chimeric viruses). At 3 days postinfection, cells were stained for NS5A and analyzed by FACS. Data are expressed as the percentage of shSR-BI-infected cells relative to the number of cells infected with the shIRR counterpart (set as 100%). Mean values and SDs from three independent experiments are shown, and values that differ significantly are indicated. ***, P < 0.001. (E) Huh-7.5 cells were electroporated with the indicated genomes and used as producers in cocultures with Huh-7.5/CD81kd/RFP-nls-IPS/SR-BIkd/GFP target cells. The graph shows the percentage of infected cells in the double CD81kd/SR-BIkd target population. Means and SDs from two independent experiments are plotted.

Clone 2 harbors 12 mutations relative to the sequence of the parental J6/JFH-1 genome, including mutations in two residues in E1 and E2 at positions I374L and I411V, respectively. To address whether changes in the glycoprotein sequences were responsible for the altered dependence on SR-BI, we constructed chimeric HCV genomes in which the E1 and E2 glycoproteins of J6/JFH-1 were replaced with those of clone 2 (J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2) and vice versa (clone 2J6 E1E2). No difference in RNA replication was observed between J6/JFH-1, clone 2 (Fig. 1D), and the chimeric derivatives (Loureiro, unpublished). Figure 5D shows that introduction of the clone 2 E1 and E2 mutations into the J6/JFH-1 backbone rendered propagation of the recombinant J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2 virus less SR-BI dependent and similar to that of clone 2. Conversely, clone 2 virus lacking the I374L (E1) and I411V (E2) mutations exhibited a growth phenotype similar to that of J6/JFH-1 in Huh-7.5/SR-BIkd cells. Since the assay described in the legend to Fig. 5D does not discriminate between cell-free infection and cell-to-cell transmission, we next compared the parental and chimeric viruses in an assay specific for cell-to-cell spread (Fig. 5E). Producer Huh-7.5 cells electroporated with each of the four genomes were cocultured with Huh-7.5/CD81kd/RFP-nls-IPS target cells transduced with a lentivirus expressing shSR-BI and green fluorescent protein (GFP) (the same as for Fig. 5A, B, and D). The efficiency of spread of each virus was determined by measuring the percentage of target cells (RFP and GFP double positive) that stained positive for NS5A (using 9E10-AF647). Similar to the data in Fig. 5D, the introduction of clone 2 glycoproteins in the J6/JFH-1 backbone improved viral fitness in SR-BIkd cells compared to that of the parental virus. In contrast, removing clone 2's E1 and E2 mutations strongly compromised the ability of that virus to spread in SR-BI-silenced cells. Interestingly, these data also show that clone 2's glycoproteins in a J6/JFH-1 background per se are not sufficient to achieve cell-to-cell spread at the clone 2 levels, suggesting that other mutations in clone 2 contribute, possibly by improving virus assembly/release. Taken together, these results show that SR-BI is important in the lateral transfer of J6/JFH-1 between cells and mutations in the glycoproteins of clone 2 virus diminish this requirement.

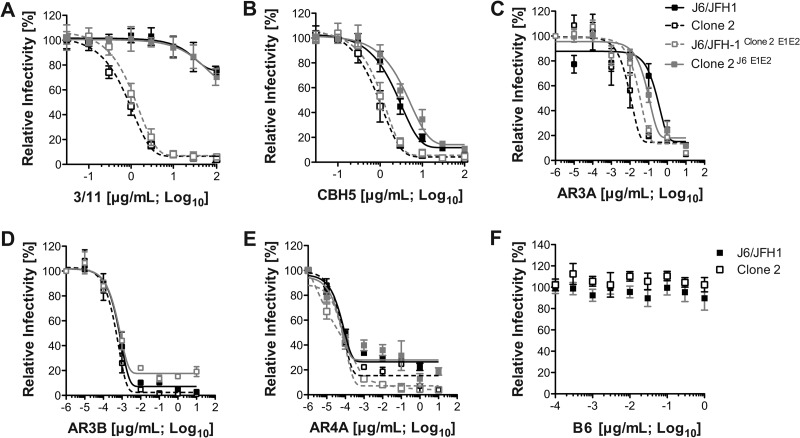

We further analyzed J6/JFH-1, clone 2, and the glycoprotein chimeras for their sensitivity to a panel of well-characterized neutralizing monoclonal antibodies recognizing linear (3/11) and conformational (CBH-5, AR3A, AR3B) E2 epitopes or spanning E1-E2 (AR4A), blocking (3/11, CBH-5, AR3A, AR3B) or not (AR4A) the E2-CD81 interaction (19, 42, 43) (Fig. 6). AR3A has been shown to compete with 3/11 and CBH-5 for binding, suggesting overlapping epitopes (43). The I374L and I411V mutations in clone 2 are outside the epitopes reported for these antibodies. We found similar neutralization profiles for J6/JFH-1, clone 2, and the chimeric viruses using the AR3B and AR4A antibodies. In contrast, 3/11, CBH-5, and AR3A exhibited enhanced neutralization of clone 2 cell-free infectivity compared to that of J6/JFH-1. Notably, J6/JFH-1clone 2 E1E2 virus, harboring clone 2 glycoproteins, displayed a neutralization profile similar to that of clone 2, while clone 2J6 E1E2 was more resistant to neutralization, similar to J6/JFH-1 (Fig. 6 and Table 2). These data suggest that the E1-E2 glycoprotein mutations in clone 2 render this virus more susceptible to cell-free neutralization by certain HCV-specific antibodies.

DISCUSSION

The ability of HCV to infect through direct cell-to-cell contact might contribute to the escape from neutralizing anti-HCV antibodies and the establishment and maintenance of chronic infection (47). Previous reports demonstrate that CLDN1 and OCLN are required for cell-cell spread (21, 48), while the involvement of CD81 is still controversial. HCVcc with mutations of E2 residues critical for CD81 binding (W529 or D535) was shown to be capable of cell-to-cell spread but not cell-free infection, suggesting that CD81 is dispensable for HCV spread (22). Cell-to-cell spread between CD81-knockdown donor or producer cells was further documented (20, 40). In contrast, another study reported that anti-CD81 antibodies inhibited both cell-free and cell-to-cell infection and proposed that both routes of transmission are CD81 dependent (21).

In this study, we used both Huh-7.5/CD81kd cells and anti-CD81 antibody to examine the contribution of CD81 to HCV cell-to-cell transmission. Huh-7.5/CD81kd cells were previously characterized for CD81 silencing and shown to be refractory to HCV cell-free entry (40). We cannot rule out the possibility that undetectable levels of CD81 on the knocked down cells insufficient for cell-free HCV entry are sufficient to allow cell-to-cell spread. However, when both producer and target cells were knocked down for CD81, HCV cell-to-cell spread still occurred, albeit with reduced efficiency (Fig. 3). Our data also indicate that CD81 on producer cells facilitates spread. We observed lower RNA replication of both viruses in CD81kd cells than in parental Huh-7.5 cells (Fig. 1D), a finding which is in agreement with a recent report by Zhang et al. (49). Nonetheless, this did not translate into reduced release of infectious particles in the cell culture medium. Therefore, diminished viral replication in Huh-7.5/CD81kd cells may not fully explain the reduced HCV cell-to-cell transmission observed when these cells are used as producers. Interestingly, our results rather suggest that the lack of CD81 exchange between donor and target cells and blockade of the functions of cell surface CD81 by an antibody negatively impact viral spread (Fig. 3E and G). CD81 has also been implicated in cell adhesion and morphology as well as signal transduction (50) and forms complexes with CLDN1 that play an essential role in HCV infection (51). Thus, CD81-silenced cells might be less efficient at transmitting HCV because of indirect effects on intercellular adhesion and receptor mislocalization. In vivo studies using human liver chimeric mice have provided evidence that CD81 might not be essential for HCV cell-to-cell transmission. In spite of potent prophylactic efficacy, anti-CD81 antibody did not prevent virus spread when administered therapeutically very soon after viral challenge (25, 52). However, these in vivo data are limited to a single monoclonal antibody, raising the possibility that the observed lack of efficacy is due to the intrinsic properties of the antibody rather than true CD81-independent cell-to-cell spread.

In contrast, treatment of human liver chimeric mice with SR-BI-targeting antibody after HCV exposure can result in efficient suppression of viral dissemination (25). Here, using time-lapse live-cell imaging and coculture assays, we show that the same anti-SR-BI antibody potently inhibits J6/JFH-1 cell-to-cell spread (Fig. 4; see also Video S1 in the supplemental material). Our data support a role for SR-BI in cell-to-cell HCV spread and demonstrate that SR-BI-specific antibodies can be effectively used to block both routes of HCV infection.

Interestingly, we identified a cell-culture adapted HCV genome, clone 2, which spreads much faster than the parental J6/JFH-1 virus (Fig. 1), requires SR-BI for cell-free entry (Fig. 2B), but shows less dependence on SR-BI for cell-to-cell spread (Fig. 4 and 5; see also Video S2 in the supplemental material). This reveals distinct requirements for SR-BI in HCV cell-free versus cell-to-cell transmission. Specific residues in E1 and E2, at polyprotein positions 374 and 411, respectively, were responsible for this phenotype (Fig. 5D and E), and both mutations were required (data not shown). It remains unclear how clone 2 glycoproteins facilitate spread under low-SR-BI conditions and whether these mutations enhance binding to SR-BI or other factors involved in viral spread. The same mutations found in clone 2 E1 and E2 glycoproteins have also been observed in independently derived HCV variants with increased titers and focus size (Loureiro, unpublished). In all cases, both mutations were coselected, suggesting that both are necessary for optimal viral fitness. Both mutations together might directly affect E1-E2 heterodimer-receptor interactions, or alternatively, one mutation might contribute this effect, with the other acting in a compensatory role to maintain proper folding and assembly of a functional E1-E2 heterodimer. In this vein, lysates from cells infected with clone 2 and clone 2J6 E1E2 (harboring wild-type J6 glycoproteins) had comparable intracellular E2 protein levels; however, clone 2 with either the E1 or the E2 mutation alone displayed significantly reduced E2 levels (data not shown). Residue 374 is in the E1 transmembrane domain, previously implicated in E1-E2 heterodimerization (53). Mutations at position 411 in E2 were identified after serial passage of a strongly attenuated genotype 2b ΔHVR1 mutant genome and shown to rescue viral viability (54).

Importantly, the mutations in clone 2 conferring an advantage in cell-to-cell spread strongly penalized cell-free transmission by rendering this virus more susceptible to Ab-mediated neutralization (Fig. 6 and Table 2). The lack of high-resolution structures for E1, E2, and E1-E2 heterodimers complexed with receptors and/or neutralizing antibodies precludes an understanding of how glycoprotein variations might influence receptor engagement and accessibility to neutralizing antibodies. Nonetheless, our data are suggestive of an interplay between clone 2 E1-E2 and SR-BI that drives fitness for cell-free and cell-to-cell transmission. Further studies will be needed to determine if enhanced fitness for cell-to-cell spread is always associated with increased exposure of neutralizing epitopes.

SR-BI's involvement in both primary attachment and entry of extracellular virions (cell-free entry route) and spread (cell-to-cell transmission route) suggests that antibodies or small molecules targeting SR-BI might be especially useful for therapeutic approaches in patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). Viral quasispecies characterized by superior entry kinetics are a hallmark in OLT patients (55). However, such variants, like mP05, can still be blocked by anti-SR-BI antibodies in the humanized urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)-SCID model (56). Although not all treated animals are completely protected, an additive to synergistic effect of anti SR-BI antibodies with HCV envelope-specific antibodies has been documented (31, 57). Thus, the combination of HCV-targeting and SR-BI-specific antibodies could transform OLT from a palliative into a curative procedure. Moreover, SR-BI blockers might also be valuable in chronic disease, for example, to slow the spread of resistant variants in patients undergoing treatment with other direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). Indeed, the SR-BI antagonist ITX 5061 displayed an additive to synergistic effect in combination with HCV protease or polymerase inhibitors in vitro (31, 57). Other practical considerations contribute to making SR-BI an attractive target for antiviral therapy. First, no significant alteration of hepatic serum markers has been observed in mice treated for 2 weeks with the anti-SR-BI antibody, suggesting that blockade of this molecule in humans might be tolerated (25). Second, among the different cell surface molecules required for HCV entry, SR-BI displays a significantly more liver-restricted expression pattern, which may minimize the likelihood of off-target effects. Finally, anti-SR-BI antibodies that do not interfere with HDL binding at concentrations sufficient to efficiently block HCV infection, thus reducing the risk of side effects due to the inhibition of SR-BI's physiologic functions, have recently been generated (31).

In terms of resistance issues, viral variants less dependent on SR-BI have been previously reported in cell culture systems. A JFH-1 genome containing a single amino acid change in E2 (G451R) bound to CD81 more efficiently and was less dependent on SR-BI for cell-free HCV entry (58) but was also compromised for cell-to-cell spread (21). Another E2 mutant, N415D, conferred resistance to ITX 5061 but increased sensitivity to anti-CD81 antibodies (57). Further studies will be required to address whether the HCV genomes with altered SR-BI usage in vitro are fit in vivo and can be successfully blocked by SR-BI-targeting antibodies or small molecules.

In conclusion, our results reveal a fine balance between glycoprotein-dependent changes in receptor engagement and increased susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies. Because of the possible emergence of HCV variants less dependent on SR-BI for cell-to-cell spread, it will be worth considering the use of a combination of antireceptor drugs with others targeting the viral envelope to maximize the chances of viral control.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Julia Sable, Ellen Castillo, and the Rockefeller University BioImaging Core Facility for the outstanding technical support and Cynthia de La Fuente for excellent editing of the manuscript and insightful discussions. We thank Alfredo Nicosia (CEINGE) and Mansun Law (The Scripps Research Institute) for generously providing antibody reagents.

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (R01 AI072613 to C.M.R.), The Greenberg Medical Research Institute, and The Starr Foundation. M.T.C. and J.L. are recipients of The Rockefeller University Women & Science Fellowship. M.D. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the German Research Foundation.

M.T.C. and C.M.R. designed the research; M.T.C., J.L., C.T.J., and M.D. performed the research; M.T.C., J.L., C.T.J., M.D., and C.M.R. analyzed the data; T.V.H. contributed new reagents/analytical tools; M.T.C. and C.M.R. wrote the paper.

We declare the following conflicts of interests, which are managed under university policy: C.M.R. has equity in Apath, LLC, which holds commercial licenses for the Huh-7.5 cell line and the HCVcc cell culture system.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 May 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01102-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lavanchy D. 2011. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zeisel MB, Cosset FL, Baumert TF. 2008. Host neutralizing responses and pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 48:299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andre P, Komurian-Pradel F, Deforges S, Perret M, Berland JL, Sodoyer M, Pol S, Brechot C, Paranhos-Baccala G, Lotteau V. 2002. Characterization of low- and very-low-density hepatitis C virus RNA-containing particles. J. Virol. 76:6919–6928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nielsen SU, Bassendine MF, Burt AD, Martin C, Pumeechockchai W, Toms GL. 2006. Association between hepatitis C virus and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)/LDL analyzed in iodixanol density gradients. J. Virol. 80:2418–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maillard P, Huby T, Andreo U, Moreau M, Chapman J, Budkowska A. 2006. The interaction of natural hepatitis C virus with human scavenger receptor SR-BI/ClaI is mediated by ApoB-containing lipoproteins. FASEB J. 20:735–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomssen R, Bonk S, Propfe C, Heermann KH, Kochel HG, Uy A. 1992. Association of hepatitis C virus in human sera with beta-lipoprotein. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 181:293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Catanese MT, Graziani R, von Hahn T, Moreau M, Huby T, Paonessa G, Santini C, Luzzago A, Rice CM, Cortese R, Vitelli A, Nicosia A. 2007. High-avidity monoclonal antibodies against the human scavenger class B type I receptor efficiently block hepatitis C virus infection in the presence of high-density lipoprotein. J. Virol. 81:8063–8071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grove J, Huby T, Stamataki Z, Vanwolleghem T, Meuleman P, Farquhar M, Schwarz A, Moreau M, Owen JS, Leroux-Roels G, Balfe P, McKeating JA. 2007. Scavenger receptor BI and BII expression levels modulate hepatitis C virus infectivity. J. Virol. 81:3162–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, Roccasecca RM, Acali S, Filocamo G, Traboni C, Nicosia A, Cortese R, Vitelli A. 2002. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 21:5017–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Agnello V, Abel G, Elfahal M, Knight GB, Zhang QX. 1999. Hepatitis C virus and other flaviviridae viruses enter cells via low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:12766–12771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sainz B, Jr, Barretto N, Martin DN, Hiraga N, Imamura M, Hussain S, Marsh KA, Yu X, Chayama K, Alrefai WA, Uprichard SL. 2012. Identification of the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor as a new hepatitis C virus entry factor. Nat. Med. 18:281–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, Petracca R, Weiner AJ, Houghton M, Rosa D, Grandi G, Abrignani S. 1998. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282:938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM, Syder AJ, Panis M, Wolk B, Hatziioannou T, McKeating JA, Bieniasz PD, Rice CM. 2007. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 446:801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ploss A, Evans MJ, Gaysinskaya VA, Panis M, You H, de Jong YP, Rice CM. 2009. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature 457:882–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lupberger J, Zeisel MB, Xiao F, Thumann C, Fofana I, Zona L, Davis C, Mee CJ, Turek M, Gorke S, Royer C, Fischer B, Zahid MN, Lavillette D, Fresquet J, Cosset FL, Rothenberg SM, Pietschmann T, Patel AH, Pessaux P, Doffoel M, Raffelsberger W, Poch O, McKeating JA, Brino L, Baumert TF. 2011. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat. Med. 17:589–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeisel MB, Fofana I, Fafi-Kremer S, Baumert TF. 2011. Hepatitis C virus entry into hepatocytes: molecular mechanisms and targets for antiviral therapies. J. Hepatol. 54:566–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blanchard E, Belouzard S, Goueslain L, Wakita T, Dubuisson J, Wychowski C, Rouille Y. 2006. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 80:6964–6972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coller KE, Berger KL, Heaton NS, Cooper JD, Yoon R, Randall G. 2009. RNA interference and single particle tracking analysis of hepatitis C virus endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000702. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hsu M, Zhang J, Flint M, Logvinoff C, Cheng-Mayer C, Rice CM, McKeating JA. 2003. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7271–7276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Timpe JM, Stamataki Z, Jennings A, Hu K, Farquhar MJ, Harris HJ, Schwarz A, Desombere I, Roels GL, Balfe P, McKeating JA. 2008. Hepatitis C virus cell-cell transmission in hepatoma cells in the presence of neutralizing antibodies. Hepatology 47:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brimacombe CL, Grove J, Meredith LW, Hu K, Syder AJ, Flores MV, Timpe JM, Krieger SE, Baumert TF, Tellinghuisen TL, Wong-Staal F, Balfe P, McKeating JA. 2011. Neutralizing antibody-resistant hepatitis C virus cell-to-cell transmission. J. Virol. 85:596–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Witteveldt J, Evans MJ, Bitzegeio J, Koutsoudakis G, Owsianka AM, Angus AG, Keck ZY, Foung SK, Pietschmann T, Rice CM, Patel AH. 2009. CD81 is dispensable for hepatitis C virus cell-to-cell transmission in hepatoma cells. J. Gen. Virol. 90:48–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sattentau Q. 2008. Avoiding the void: cell-to-cell spread of human viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:815–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mothes W, Sherer NM, Jin J, Zhong P. 2010. Virus cell-to-cell transmission. J. Virol. 84:8360–8368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meuleman P, Catanese MT, Verhoye L, Desombere I, Farhoudi A, Jones CT, Sheahan T, Grzyb K, Cortese R, Rice CM, Leroux-Roels G, Nicosia A. 2012. A human monoclonal antibody targeting scavenger receptor class B type I precludes hepatitis C virus infection and viral spread in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology 55:364–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. 1996. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science 271:518–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Connelly MA, Williams DL. 2004. Scavenger receptor BI: a scavenger receptor with a mission to transport high density lipoprotein lipids. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 15:287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Calvo D, Gomez-Coronado D, Lasuncion MA, Vega MA. 1997. CLA-1 is an 85-kD plasma membrane glycoprotein that acts as a high-affinity receptor for both native (HDL, LDL, and VLDL) and modified (OxLDL and AcLDL) lipoproteins. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 17:2341–2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rigotti A, Trigatti BL, Penman M, Rayburn H, Herz J, Krieger M. 1997. A targeted mutation in the murine gene encoding the high density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor scavenger receptor class B type I reveals its key role in HDL metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:12610–12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ji Y, Jian B, Wang N, Sun Y, Moya ML, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH, Swaney JB, Tall AR. 1997. Scavenger receptor BI promotes high density lipoprotein-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20982–20985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zahid MN, Turek M, Xiao F, Thi VL, Guerin M, Fofana I, Bachellier P, Thompson J, Delang L, Neyts J, Bankwitz D, Pietschmann T, Dreux M, Cosset FL, Grunert F, Baumert TF, Zeisel MB. 2013. The postbinding activity of scavenger receptor class B type I mediates initiation of hepatitis C virus infection and viral dissemination. Hepatology 57:492–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Voisset C, Callens N, Blanchard E, Op De Beeck A, Dubuisson J, Vu-Dac N. 2005. High density lipoproteins facilitate hepatitis C virus entry through the scavenger receptor class B type I. J. Biol. Chem. 280:7793–7799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dreux M, Pietschmann T, Granier C, Voisset C, Ricard-Blum S, Mangeot PE, Keck Z, Foung S, Vu-Dac N, Dubuisson J, Bartenschlager R, Lavillette D, Cosset FL. 2006. High density lipoprotein inhibits hepatitis C virus-neutralizing antibodies by stimulating cell entry via activation of the scavenger receptor BI. J. Biol. Chem. 281:18285–18295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bartosch B, Vitelli A, Granier C, Goujon C, Dubuisson J, Pascale S, Scarselli E, Cortese R, Nicosia A, Cosset FL. 2003. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278:41624–41630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bartosch B, Verney G, Dreux M, Donot P, Morice Y, Penin F, Pawlotsky JM, Lavillette D, Cosset FL. 2005. An interplay between hypervariable region 1 of the hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein, the scavenger receptor BI, and high-density lipoprotein promotes both enhancement of infection and protection against neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 79:8217–8229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Catanese MT, Ansuini H, Graziani R, Huby T, Moreau M, Ball JK, Paonessa G, Rice CM, Cortese R, Vitelli A, Nicosia A. 2010. Role of scavenger receptor class B type I in hepatitis C virus entry: kinetics and molecular determinants. J. Virol. 84:34–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zeisel MB, Koutsoudakis G, Schnober EK, Haberstroh A, Blum HE, Cosset FL, Wakita T, Jaeck D, Doffoel M, Royer C, Soulier E, Schvoerer E, Schuster C, Stoll-Keller F, Bartenschlager R, Pietschmann T, Barth H, Baumert TF. 2007. Scavenger receptor class B type I is a key host factor for hepatitis C virus infection required for an entry step closely linked to CD81. Hepatology 46:1722–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mensa L, Crespo G, Gastinger MJ, Kabat J, Perez-del-Pulgar S, Miquel R, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, Forns X. 2011. Hepatitis C virus receptors claudin-1 and occludin after liver transplantation and influence on early viral kinetics. Hepatology 53:1436–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Syder AJ, Lee H, Zeisel MB, Grove J, Soulier E, Macdonald J, Chow S, Chang J, Baumert TF, McKeating JA, McKelvy J, Wong-Staal F. 2011. Small molecule scavenger receptor BI antagonists are potent HCV entry inhibitors. J. Hepatol. 54:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jones CT, Catanese MT, Law LM, Khetani SR, Syder AJ, Ploss A, Oh TS, Schoggins JW, MacDonald MR, Bhatia SN, Rice CM. 2010. Real-time imaging of hepatitis C virus infection using a fluorescent cell-based reporter system. Nat. Biotechnol. 28:167–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, Hynes RO, Burton DR, McKeating JA, Rice CM. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hadlock KG, Lanford RE, Perkins S, Rowe J, Yang Q, Levy S, Pileri P, Abrignani S, Foung SK. 2000. Human monoclonal antibodies that inhibit binding of hepatitis C virus E2 protein to CD81 and recognize conserved conformational epitopes. J. Virol. 74:10407–10416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Giang E, Dorner M, Prentoe JC, Dreux M, Evans MJ, Bukh J, Rice CM, Ploss A, Burton DR, Law M. 2012. Human broadly neutralizing antibodies to the envelope glycoprotein complex of hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:6205–6210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Walters KA, Syder AJ, Lederer SL, Diamond DL, Paeper B, Rice CM, Katze MG. 2009. Genomic analysis reveals a potential role for cell cycle perturbation in HCV-mediated apoptosis of cultured hepatocytes. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000269. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Horwitz JA, Dorner M, Friling T, Donovan BM, Vogt A, Loureiro J, Oh T, Rice CM, Ploss A. 2013. Expression of heterologous proteins flanked by NS3-4A cleavage sites within the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Virology 439:23–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Meredith LW, Harris HJ, Wilson GK, Fletcher NF, Balfe P, McKeating JA. 2013. Early infection events highlight the limited transmissibility of hepatitis C virus in vitro. J. Hepatol. 58:1074–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Di Lorenzo C, Angus AG, Patel AH. 2011. Hepatitis C virus evasion mechanisms from neutralizing antibodies. Viruses 3:2280–2300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ciesek S, Westhaus S, Wicht M, Wappler I, Henschen S, Sarrazin C, Hamdi N, Abdelaziz AI, Strassburg CP, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP, Pietschmann T, von Hahn T. 2011. Impact of intra- and interspecies variation of occludin on its function as coreceptor for authentic hepatitis C virus particles. J. Virol. 85:7613–7621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang YY, Zhang BH, Ishii K, Liang TJ. 2010. Novel function of CD81 in controlling hepatitis C virus replication. J. Virol. 84:3396–3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Levy S, Todd SC, Maecker HT. 1998. CD81 (TAPA-1): a molecule involved in signal transduction and cell adhesion in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:89–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harris HJ, Davis C, Mullins JG, Hu K, Goodall M, Farquhar MJ, Mee CJ, McCaffrey K, Young S, Drummer H, Balfe P, McKeating JA. 2010. Claudin association with CD81 defines hepatitis C virus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 285:21092–21102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Meuleman P, Hesselgesser J, Paulson M, Vanwolleghem T, Desombere I, Reiser H, Leroux-Roels G. 2008. Anti-CD81 antibodies can prevent a hepatitis C virus infection in vivo. Hepatology 48:1761–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Op De Beeck A, Montserret R, Duvet S, Cocquerel L, Cacan R, Barberot B, Le Maire M, Penin F, Dubuisson J. 2000. The transmembrane domains of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 play a major role in heterodimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31428–31437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Prentoe J, Jensen TB, Meuleman P, Serre SB, Scheel TK, Leroux-Roels G, Gottwein JM, Bukh J. 2011. Hypervariable region 1 differentially impacts viability of hepatitis C virus strains of genotypes 1 to 6 and impairs virus neutralization. J. Virol. 85:2224–2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fafi-Kremer S, Fofana I, Soulier E, Carolla P, Meuleman P, Leroux-Roels G, Patel AH, Cosset FL, Pessaux P, Doffoel M, Wolf P, Stoll-Keller F, Baumert TF. 2010. Viral entry and escape from antibody-mediated neutralization influence hepatitis C virus reinfection in liver transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 207:2019–2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lacek K, Vercauteren K, Grzyb K, Naddeo M, Verhoye L, Slowikowski MP, Fafi-Kremer S, Patel AH, Baumert TF, Folgori A, Leroux-Roels G, Cortese R, Meuleman P, Nicosia A. 2012. Novel human SR-BI antibodies prevent infection and dissemination of HCV in vitro and in humanized mice. J. Hepatol. 57:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhu H, Wong-Staal F, Lee H, Syder A, McKelvy J, Schooley RT, Wyles DL. 2012. Evaluation of ITX 5061, a scavenger receptor B1 antagonist: resistance selection and activity in combination with other hepatitis C virus antivirals. J. Infect. Dis. 205:656–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Grove J, Nielsen S, Zhong J, Bassendine MF, Drummer HE, Balfe P, McKeating JA. 2008. Identification of a residue in hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein that determines scavenger receptor BI and CD81 receptor dependency and sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 82:12020–12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.