Abstract

Objectives

To describe the presenting symptoms, endoscopic and histologic findings, and clinical courses of pediatric patients diagnosed with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS).

Methods

We describe 15 cases of SRUS diagnosed at our institution over a 13-year period. Cases were identified by review of a pathology database and chart review and confirmed by review of biopsies. Data were collected by retrospective chart review.

Results

Presenting symptoms were consistent but non-specific, most commonly including blood in stools, diarrhea alternating with constipation, and abdominal/perianal pain. Fourteen of 15 patients had normal hemoglobin/hematocrit, ESR, and albumin at diagnosis. Endoscopic findings, all limited to the distal rectum, ranged from erythema to ulceration and polypoid lesions. Histology revealed characteristic findings. Stool softeners and mesalamine suppositories improved symptoms, but relapse was common.

Conclusions

SRUS in children presents with non-specific symptoms and endoscopic findings. Clinical suspicion is required, and diagnosis requires histologic confirmation. Response to current treatments is variable.

Keywords: solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, rectal bleeding, pediatrics, constipation, rectum, prolapse

Introduction

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare condition most commonly characterized by rectal pain and bleeding. It can be accompanied by diarrhea or constipation, tenesmus, and rectal prolapse1, 2. Given its non-specific symptoms, it is often difficult to diagnose, particularly in children. The incidence of SRUS has been estimated at 1 in 100,000 adults, with only a few reported pediatric cases1, 3. In the largest case series of children to date, 12 of 256 (5%) Iranian children with rectal bleeding and straining at the time of defecation were diagnosed with SRUS3. Given that the histological and endoscopic appearance mimics other disorders of the rectum, diagnosis of SRUS can be difficult1, 4.

We describe the range of presenting symptoms and endoscopic and histologic findings that should raise a clinician’s awareness for pediatric patients warranting further assessment for SRUS.

Methods

All pediatric patients diagnosed with SRUS at the University of California, San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital (UCSF) and an affiliated practice, Pediatric Gastroenterology Associates, were retrospectively reviewed. Cases were identified by searching medical records for ICD9 code 569.41 and the Department of Pathology’s biopsy database using “solitary (rectal) ulcer” and “mucosal prolapse” as search terms. Children less than 21 years old at diagnosis with biopsy proven cases of SRUS between 1997 and 2009 were included.

All slides (H&E) were reviewed by a pathologist (SJC) to confirm the SRUS diagnosis. SRUS was defined by characteristic changes on rectal biopsy including smooth muscle hyperplasia in the lamina propria, hyperplasia of the muscularis mucosae, surface ulceration, architectural distortion (misshapen crypts), and ectasia of superficial capillaries. Patients whose biopsies were not confirmed as SRUS were excluded. Clinical records were then reviewed to identify presenting symptoms, endoscopic findings, laboratory values, treatments and outcomes. Given the small number of patients in our series, we presented all descriptive statistics as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Results

Demographics (Table 1)

Table 1. Patient Demographics and Clinical Presentation.

| N | |

|---|---|

| Male | 12 |

| Female | 3 |

| Caucasian | 9 |

| Other | 6 |

| Symptoms at Diagnosis | |

| Blood in stool | 11 |

| Abdominal Pain | 9 |

| Diarrhea | 9 |

| Constipation | 6 |

| Perianal pain | 4 |

| Age at Diagnosis, (median years, IQR) | 13.9 (9.8-15.6) |

|

Symptomatic Before Diagnosis (median

years, IQR) |

3.2 (1.2-5.5) |

Fifteen pediatric patients from our database were diagnosed with SRUS between 1997 and 2009. Twelve were boys, and nine (60%) were Caucasian. Median age at diagnosis was 13.9 (IQR 9.8-15.6) years.

Clinical Presentation (Table 1)

Common presenting symptoms included rectal bleeding, alternating diarrhea and constipation, abdominal pain, and perianal pain with defecation. Nine of 15 (60%) complained of cramping abdominal pain, nine (60%) had diarrhea, and 11 (73%) had blood in stool. Median duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis was 3.2 (IQR 1.2-5.5) years. Two patients (13%) were diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) prior to diagnosis with SRUS.

Lab Values

Laboratory data were collected from the time of initial visit to UCSF. Despite rectal bleeding in 73% of the patients, none were anemic. Median hemoglobin value was 13.1 (IQR 12.6-14.0) g/dL. All nine patients with measured serum albumin levels had normal values (4.2, IQR 4.0-4.5 g/dL). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was normal (4.0, IQR 3.5-5 mm/h) in all but one patient, whose ESR was 17mm/h. This patient was subsequently diagnosed with HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathy, although endoscopy, colonoscopy, and abdominal imaging showed no evidence of IBD, and biopsies were consistent with SRUS.

Other Diagnoses and Family History

Of the two patients diagnosed with IBD, one patient had ulcerative colitis in conjunction with a history of autoimmune thyroiditis and autoimmune hepatitis. The other patient had a long-standing history of ulcerative colitis prior to the SRUS diagnosis. Both patients first presented with gastrointestinal symptoms, including loose bloody stools and abdominal pain, between 7 to 8 years of age. Both were initially diagnosed with IBD and then subsequently diagnosed with SRUS (2.5 and 7 years after presentation, respectively). Both had histologic findings consistent with SRUS in the distal rectum in addition to more proximal inflammation.

None of the 15 patients had a family history of SRUS. Neither of the patients diagnosed with IBD had a family history of IBD, but three of the other patients with SRUS (20%) had a family history of IBD.

Endoscopic Findings

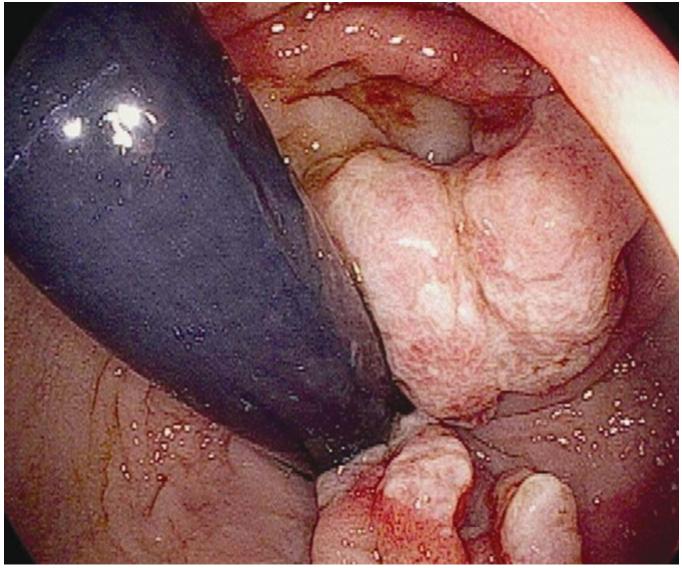

Endoscopic findings varied widely. All patients had endoscopic abnormalities in the distal rectum, mostly limited to within 10 cm of the anal verge. (Figure 1) Of the 10 patients with endoscopic reports available, 8 had visible erythema or inflammation. Four patients had polyps or polypoid lesions.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic image of SRUS patient, showing distal rectum on retroflexion. Multiple polypoid lesions surrounded by erythema and inflammatory infiltrates.

Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Patient characteristics.

| ID | Gender | Age at Diagnosis (Years) |

Years Symptomatic Before Diagnosis |

Presenting Symptoms | Endoscopic Findings at SRUS diagnosis |

Treatments | Remission | Time to Remission (months after diagnosis) |

Time to Relapse (months after remission achieved) |

Length of Follow-Up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 3.7 | 3.6 | Abdominal pain, distension, constipation |

NA** | Stool softeners, mesalamine suppositories/enemas |

NA | 3 | ||

| 2 | M | 13.6 | 1.0 | Blood in stools, diarrhea, Abdominal pain, Perirectal pain |

Sigmoid colon: nodular mucosa |

Stool softeners, mesalamine suppositories |

Y | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| 3 | F | 14.6 | 7.0 | Blood in stools, diarrhea and constipation, abdominal pain |

NA | Stool softeners, mesalamine suppositories |

N | 84 | ||

| 4 | M | 9.1 | NA | Blood in stools, constipation, rectal prolapse |

NA | NA | NA | 1 | ||

| 5 | M | 6.2 | 6.0 | Blood in stools, rectal prolapse | Distal colon/rectum: erythema |

Stool softeners, mesalamine suppositories |

Y | 12 | NA | 71 |

| 6 | M | 2.9 | 2.0 | Diarrhea and constipation, abdominal distension |

NA | Stool softeners, mesalamine suppositories/enemas |

NA | 1 | ||

| 7 | M | 17.1 | 3.7 | Blood in stools, diarrhea and constipation, abdominal pain, urgency, tenesmus |

Rectum: 3 pedunculated polyps surrounded by inflammation, exudate. |

Polypectomy, stool softeners, mesalamine suppositories |

Y | 3 | 1.5 | 12 |

| 8 | M | 13.1 | 0.5 | Blood in stools, diarrhea, abdominal pain, perianal pain, tenesmus, rectal prolapse |

Rectum (to 5 cm from anal verge): Inflammation, erythema with exudate. |

Stool softeners, mesalamine suppositories |

Y | 11 | 4 | 40 |

| 9 | M | 15.7 | 1.1 | Blood in stools, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, urgency, tenesmus |

Rectum (to 5 cm from anal verge): patchy erythema and nodular mucosa. |

Stool softeners | NA | 3 | ||

| 10 | M | 14.3 | 1.0 | Blood in stools | NA | Polypectomy | Y | NA | NA | 1 |

| 11 | F | 13.9 | 4.0 | Blood in stools, difficulty with defecation; |

Rectum: multiple sessile polyps (recurrent). |

Polypectomy, then partial proctectomy for recurrent polyps/bleeding. Persistent constipation with hemorrhoids but no recurrent polyps. Stool softeners. |

NA | 152 | ||

| 12 | M | 15.9 | 7.3 | Blood in stools, perianal pain | Rectum (to 2 cm from anal verge): erythema |

Stool softeners | N | 87 | ||

| 13 | M | 15.5 | 1.4 | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, fevers, hip pain. Also with persistently elevated ESR and anemia; later diagnosed with HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathy. |

Rectum (at 5 cm from anal verge): one sessile polyp |

Polypectomy | Y | 2 | NA | 13 |

| 14* | M | 16.6 | 7.7 | Blood in stools, diarrhea and constipation, abdominal pain. History of ulcerative coliits. |

Rectum (to 10 cm from anal verge): erythema, multiple erosions. Later developed nodularity, polypoid lesions in the distal rectum. |

Mesalamine suppositories, Corticosteroid, Oral and Rectal 5-ASA, Enema |

NA | 83 | ||

| 15* | F | 10.5 | 2.7 | Blood in stools, diarrhea, abdominal pain, perianal pain. History of autoimmune hepatitis, thyroiditis, ulcerative colitis. |

Rectum (to 10 cm frrom anal verge): erythema, inflammation. Also had ulcers in proximal colon and cecum. |

Stool softeners, mesalamine enemas, oral 5-ASA, oral steroids, antibiotics |

N | 24 |

Patients with IBD

NA: Data not available

Histologic Findings (Table 3)

Table 3. Histologic Findings in Patients at Diagnosis.

| N | |

|---|---|

| Muscularization of lamina propria | 14 |

| Thickened muscularis mucosae | 13 |

| Ulceration / Mixed inflammatory infiltrate | 11 |

| Epithelial hyperplastic changes | 10 |

| Misshapen crypts | 8 |

| Vascular ectasia | 8 |

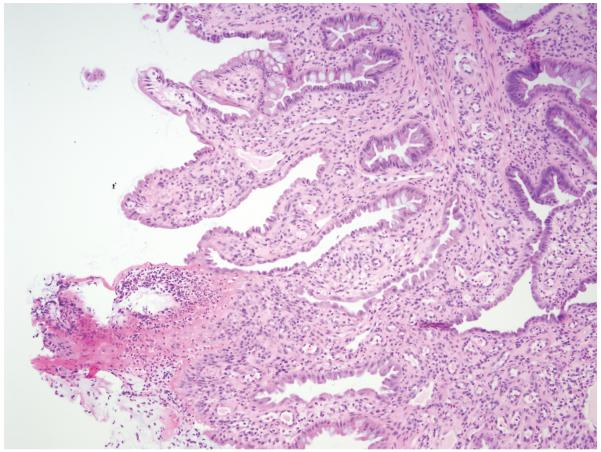

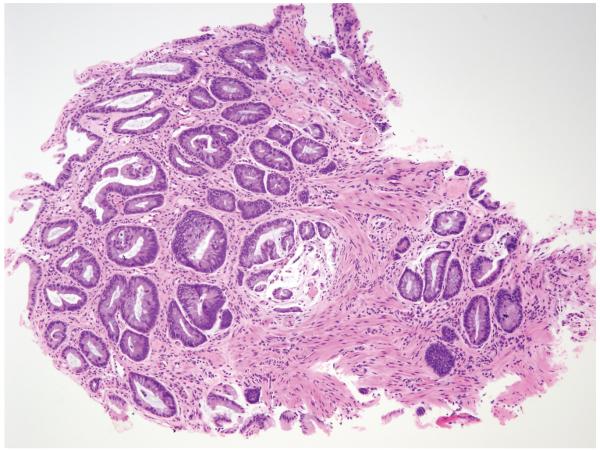

All patients (15) had at least one rectal biopsy with histologic findings consistent with SRUS or mucosal prolapse. Multiple biopsies were available for review for 6 patients, with histologic features of SRUS seen in multiple biopsies for 4 of these patients. Common histologic findings included muscularization of the lamina propria with strands or bundles of smooth muscle extending between crypts, thickening or hyperplasia of the muscularis mucosae, surface ulceration with inflammation, focal hyperplastic changes in the epithelium, misshapen crypts, and vascular ectasia/congestion, which have all been described in previous reports of SRUS or mucosal prolapse5-10. (Figures 2, 3) A mixed inflammatory infiltrate was often seen in areas of ulceration, but cryptitis or crypt abscesses and chronic changes characteristic of inflammatory bowel disease were not seen in most biopsies. In the 2 patients with a concurrent diagnosis of IBD, one of the patients had a single biopsy available for review which showed features of SRUS without features of IBD. Five biopsies were available for review for the other patient with IBD, one of which showed features of SRUS without features of IBD, 1 of which showed features of an inflammatory polyp, and 2 of which showed overlapping features (particularly surface ulceration with granulation tissue and dense inflammation). In addition, while reactive epithelial atypia was seen in biopsies of 3 of the patients, none of the biopsies had definitive evidence of dysplasia or adenocarcinoma.

Figure 2.

Rectal biopsy from the SRUS patient whose endoscopy is shown in Figure 1. Histology (H&E) shows smooth muscle hyperplasia in the lamina propria and surface ulceration with associated acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrates. Crypt architectural changes as well as vascular proliferation and ectasia of superficial mucosa are also present.

Figure 3.

Rectal biopsy (H&E) from another SRUS patient showing smooth muscle hyperplasia in the lamina propria and of the muscularis mucosae, as well as crypt architectural distortion with misshapen crypts, mild vascular ectasia of superficial mucosa, and minimal inflammatory infiltrate.

Treatment

The thirteen patients without IBD were treated with laxatives, stool softeners, and mesalamine suppositories or enemas. Four underwent polypectomy at diagnosis. One patient required proctectomy for recurrent symptomatic polyps. The two patients with IBD were treated with stool softeners, oral or rectal aminosalicylates, oral or rectal corticosteroids, and antibiotics throughout the course of their follow-up. Several of the patients were lost to follow-up after initial diagnosis and treatment, precluding assessment of their response to treatment. In those patients who did have long-term follow-up, 6 of 9 responded to treatment, but at least 50% had recurrent symptoms, particularly after medication adherence lapsed.

Discussion

Our review of pediatric patients at our institution revealed 15 cases of SRUS over a 13-year period. Presenting symptoms were consistent but non-specific. Delay in diagnosis was common, likely because of the non-specific symptoms and rarity of SRUS in the pediatric population. Our cases had a median 3.2 year delay between symptom onset and diagnosis. This is similar to the delay in diagnosis seen in pediatric IBD patients, who also often present with similar symptoms11. Treatment led to clinical improvement in most patients, but symptoms often recurred with poor medication adherence.

Our series confirms that SRUS is a misnomer since not all lesions are solitary nor ulcers. Previous reports support this characterization 4, 12. SRUS has also been referred to as mucosal prolapse to avoid this confusion10. Endoscopically, the distal rectal mucosa typically appears erythematous, and lesions can be ulcerative or polypoid 3, 13. Differential diagnosis in children includes juvenile polyps, infections, IBD, sexual abuse, or rectal digitations. Because our case search strategy relied on cases confirmed by pathology, we were not able to include cases suspected to be SRUS that did not have pathologic confirmation or were diagnosed as other disorders on histology.

Given the lack of symptom specificity and endoscopic findings seen in our cases, this series supports the necessity for histological diagnosis. The histologic changes are similar to those seen in adults. Characteristic findings include muscularization of the lamina propria, hyperplastic muscularis mucosa, and distortion of crypt architecture9, 10,14. SRUS is distinguished from IBD by scarring of the lamina propria with only a relatively mild inflammatory infiltrate, as well as the accompanying muscular hyperplasia14. Our patients without coexistent IBD had findings limited to the distal rectum.

Two of our cases, however, illustrate that SRUS and IBD can coexist in children and adolescents. Previous case reports in the adult literature have also noted concurrent SRUS and IBD, particularly ulcerative colitis (UC)15,16. Thus, a diagnosis of IBD should not preclude consideration of SRUS, as management may differ. For those with concurrent SRUS and IBD, stool softeners and/or anti-inflammatory enemas to treat the SRUS may be necessary even when systemic medications are used to treat the IBD.

Since SRUS and IBD can present with identical symptoms—and have similar endoscopic features—SRUS can also be misdiagnosed as IBD. Misdiagnosis is concerning because the oral or intravenous immunosuppressive medications used for ulcerative colitis are unlikely to be effective in SRUS. In addition, since patients with long-standing IBD colitis can develop malignant lesions in the colon, SRUS could be misdiagnosed as tumor16. Thus, histologic confirmation of the diagnosis is important to guide management. IBD with rectal ulcers could also be mistaken for SRUS; in general, features of systemic disease, such as weight loss, extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD, or elevated serum inflammatory markers, should not be present in isolated SRUS.

While its etiology is unclear, SRUS has been linked to direct mucosal trauma, rectal dysmotility, and ischemia. Strained defecation in some patients may lead to direct ulceration of the mucosa. In others, the anterior rectal mucosa is forced into the anal canal, causing rectal prolapse and mucosal injury4, 14. Rectal prolapse and high intra-abdominal pressures may contribute to vascular compression, leading to mucosal ischemia1. Tenesmus and straining related to IBD colitis have been theorized contributors to the development of SRUS in patients with both disorders.

SRUS is not considered to be invasive or progressive. However it tends to be refractory5, as the outcomes of our patients suggest. Common treatments include laxatives, stool softeners, and rectal aminosalicylates 1,2,17. Surgery has also occasionally been used with minimal long-term success, since the lesions often recur if the straining and dysmotility continue. In our patients, stool softeners and mesalamine suppositories were most often used. The small number of patients and variable follow-up prevent us from drawing robust conclusions about treatment efficacy.

Our analysis was limited due to the relatively small sample size and missing data. Multi-center prospective cohort studies would help identify treatment methods and outcome of pediatric patients with SRUS.

Acknowledgments

Partial support for this work is from NIH Grants DK060617 and DK007762.

Footnotes

No authors have any conflicts of interest related to this report.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Keshtgar AS. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008:89–92. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f402c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De la Rubia L, Ruiz Villaespesa A, Cebrero M, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in a child. J Pediatr. 1993:733–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehghani SM, Haghighat M, Imanieh MH, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children: A prospective study of cases from southern iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008:93–5. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f1cbb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ertem D, Acar Y, Karaa EK, et al. A rare and often unrecognized cause of hematochezia and tenesmus in childhood: Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Pediatrics. 2002:e79. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madigan MR, Morson BC. Solitary ulcer of the rectum. Gut. 1969:871–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.10.11.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren BF, Dankwa EK, Davies JD. ‘Diamond-shaped’ crypts and mucosal elastin: Helpful diagnostic features in biopsies of rectal prolapse. Histopathology. 1990:129–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franzin G, Scarpa A, Dina R, et al. “Transitional” and hyperplastic-metaplastic mucosa occurring in solitary ulcer of the rectum. Histopathology. 1981:527–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1981.tb01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tendler DA, Aboudola S, Zacks JF, et al. Prolapsing mucosal polyps: An underrecognized form of colonic polyp--a clinicopathological study of 15 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002:370–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang JM, Changchien CR, Chen JR. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: An endoscopic and histological presentation and literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006:348–56. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh B, Mortensen NJ, Warren BF. Histopathological mimicry in mucosal prolapse. Histopathology. 2007:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyman MB, Kirschner BS, Gold BD, et al. Children with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Analysis of a pediatric IBD consortium registry. J Pediatr. 2005:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin CJ, Parks TG, Biggart JD. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in Northern Ireland. Br J Surg. 1981:744–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800681021. 1971-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.du Boulay CE, Fairbrother J, Isaacson PG. Mucosal prolapse syndrome--a unifying concept for solitary ulcer syndrome and related disorders. J Clin Pathol. 1983:1264–1268. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharara AI, Azar C, Amr SS, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: Endoscopic spectrum and review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005:755–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arhan M, Onal IK, Ozin Y, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in association with ulcerative colitis: A case report. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Feb;:190–1. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uza N, Nakase H, Nishimura K, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome associated with ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Feb;:355–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bishop PR, Nowicki MJ, Subramony C, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer: A rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in an adolescent with hemophilia A. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001:72–6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200107000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]