Abstract

Objective

Obesity is an enormous public health problem and children have been particularly highlighted for intervention. Of notable concern is the fast-food consumption of children. However, we know very little about how children or their parents make fast-food choices, including how they respond to mandatory calorie labeling. We examined children’s and adolescents’ fast-food choice and the influence of calorie labels in low-income communities in New York City (NYC) and in a comparison city (Newark, NJ).

Design

Natural experiment: Survey and receipt data were collected from low-income areas in NYC, and Newark, NJ (as a comparison city), before and after mandatory labeling began in NYC. Study restaurants included four of the largest chains located in NYC and Newark: McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Subjects

A total of 349 children and adolescents aged 1–17 years who visited the restaurants with their parents (69%) or alone (31%) before or after labeling was introduced. In total, 90% were from racial or ethnic minority groups.

Results

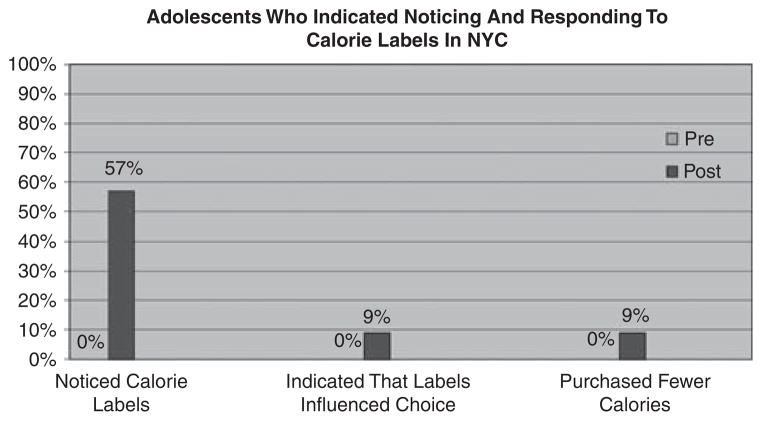

We found no statistically significant differences in calories purchased before and after labeling; many adolescents reported noticing calorie labels after their introduction (57% in NYC) and a few considered the information when ordering (9%). Approximately 35% of adolescents ate fast food six or more times per week and 72% of adolescents reported that taste was the most important factor in their meal selection. Adolescents in our sample reported that parents have some influence on their meal selection.

Conclusions

Adolescents in low-income communities notice calorie information at similar rates as adults, although they report being slightly less responsive to it than adults. We did not find evidence that labeling influenced adolescent food choice or parental food choices for children in this population.

Keywords: menu labeling, fast food, low-income communities, childhood nutrition

Introduction

Following 10 years of heightened public attention and alarm about a national ‘obesity epidemic,’1 the first significant policy effort to pass the US Congress was recently signed into law. Calorie menu labeling, implemented in a handful of American cities and counties beginning in New York City (NYC) in 2008, is mandated on a national level by the new health reform law, the ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’ of 2010 (hereafter referred to as ACA). Foremost among the claims in support of this policy innovation is that menu labeling will help consumers make better-informed and healthier food choices.2 Parents concerned about their children’s diets are advertised as particular beneficiaries; for example, menu labeling is prominent among the ‘recommendations for empowering parents and caregivers’ in the May 2010 report of the White House Task Force on Child Obesity, chaired by Michelle Obama.3

Recent increases in childhood obesity are attributed in significant part to unhealthy nutritional practices, along with limited physical activity.4 Fast food is a prominent contributor to caloric consumption, and has been directly linked to higher obesity rates among children and adolescents. 5,6 The spreading popularity among policymakers of menu labeling has made it a primary American policy approach to obesity.

The new ACA law mandates that restaurants with ≥20 locations nationally must post the caloric content of their menu items. Labels must appear ‘adjacent to the name’ and in the same size/font as the menu item: fast-food establishments are to list calorie counts on their menu boards, whereas sit-down restaurants should do so on the printed menu. In these specifications, the ACA resembles labeling laws passed in NYC and elsewhere.

Child and adolescent fast-food choice and menu labeling: current research

As a relatively new policy, few evaluations of menu labeling exist; those that do exist generally either note small effects or inconsistent results. One recent point-of-purchase study on fast-food restaurants in NYC and Newark, NJ— a comparison city, which had not considered labeling when New York implemented its law in 2008—found minimal impact of menu labeling on consumption choices.7 A smaller evaluation study of New York, involving no control city, performed by Downs et al.8 reached similar conclusions. Both these evaluations reported on the effects of labeling on exclusively adult consumers.

Experimental studies on food consumption among adolescents routinely find that caloric information or nutrition is not a major consideration in food selection. Taste, hunger, peer preferences and other factors appear to be more important.9,10,11 Involvement of parents in the food choices of their children is not well understood by researchers, although a clear association exists between young children’s food preferences—healthy or otherwise—and parent-reported food and beverage purchases, suggesting parent role modeling.12 A series of focus groups involving 9- to 12-year-old children and their parents, most from lower-middle socioeconomic groups, yielded two primary findings: the children regarded low-fat food as unappetizing, and the parents reported that the high cost of fruits, vegetables and 100% juice explained their relative unavailability at home.13 However, one recent experimental study that took place in a pediatric clinic in Seattle, Washington, did find that, in a hypothetical choice scenario, parents of children 3–6 years of age indicated that they would purchase an average of 102 fewer calories when provided with calorie information.14

Our study was designed in part to examine whether calorie labels help inform—and, ideally, enhance—parent/caregiver and adolescent food choices, as well as shed light on these fast-food choices more generally. Although the sample size available to study this important group was small, it was nevertheless critical that it be analyzed. We examined the natural experiment of labeling being introduced in NYC by using a pre-/post-design to gather data on adults purchasing food for their children, as well as adolescents purchasing for themselves, at a group of fast-food restaurants in NYC and in a comparison city before and after calorie labeling began in NYC. Given that low-income, racially and ethnically diverse populations bear a greater burden of obesity and its related health problems, we focused on this group. As experts in this area have recently noted: ‘Interventions that fail to account for the unique needs of disadvantaged communities risk the unintended effect of promoting greater health disparities.’15,16

Methods

Choice of cities, neighborhoods and restaurants

We collected data on adolescent and parent food choices from NYC—the first site in the country to introduce calorie labeling—and from a comparison city, Newark, NJ. Neither Newark nor New Jersey had passed a calorie labeling law when we conducted our study in summer 2008. Newark has similar urban and demographic characteristics and is close enough to NYC to permit a reasonably consistent comparison; also important for our purposes was the fact that relatively few Newark residents commute daily to New York to work (or purchase fast food).17

We surveyed restaurants representing four of the largest chains located in NYC and Newark: McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken. Two restaurants from each chain in NYC were matched with one from the same chain in Newark. We aligned restaurants/neighborhoods using six sets of population-level characteristics: population size, age, race/ethnicity, poverty level, obesity rates and diabetes rates. We also attempted to match key structural or geographic characteristics in our restaurant pairing (for example, relative location to public transportation; proximity to large apartment complexes, hospitals or other institutions; location in a downtown area). Our restaurant sample included five restaurants in Newark and 14 in NYC: five Wendy’s, eight McDonald’s, three Burger King and three Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets. In New York, our data collection locations encompassed lower-income areas in four of the five boroughs, with neighborhoods including the South Bronx; central Brooklyn; Harlem and Washington Heights in Manhattan; and the Rockaways in Queens. For more details see Elbel et al.7

Data collection

Over a two-week period beginning in early July 2008—before actual implementation of calorie labeling in NYC—a research team of 3–4 individuals visited selected restaurants during lunch (generally 12:30–3:00 PM) or dinner hours (4:30–7:00 PM). Restaurants were visited on a Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday (avoiding days most likely to consist of ‘special’ or ‘treat’ meals). We utilized a methodology based on established ‘street-intercept’ survey practices.18 All customers were approached as they entered the restaurant during designated survey periods. They were asked to bring their receipt back and answer a set of questions for a compensation of $2. Subjects were not told why the receipts were being collected. Anyone aged 13 years and above was eligible for data collection. (On response rates, see Elbel et al7).

On 19 July 2008, labeling began in NYC. Post-labeling data were collected from the same restaurants ~4 weeks after this date from a separate cross-section of fast-food consumers. The collection was headed by the same research staff, utilizing the same methodology on the same days of the week during the same time period. Collecting data from the same locations both before and after labeling should minimize any unobservable differences between restaurants. This paper includes results from (a) adolescents aged 13–17 years who answered the survey for themselves and (b) parents or caregivers who accompanied children 1–17 years of age at the restaurant, and who answered questions about the choices made for their child.

Fast-food receipts

The receipt indicating food items purchased by each adolescent for his or her consumption, or by a parent/caregiver for their child, was obtained by study staff in order to objectively determine nutritional data. Food items purchased, along with any modifications or additions (for example, added cheese, regular or diet soda), were confirmed by study staff with verbal review. We utilized the nutritional data provided on the corporate website of each fast-food establishment to calculate—for each item purchased and for the order as a whole—nutritional information about calories, saturated fat, sodium and sugar. These aspects were chosen on the basis of their associations with obesity, chronic disease and overall health. We did not notice any significant changes to the restaurant menus or nutritional information between our pre- and post-study periods.

Surveys

On verifying and confirming food purchase details, a short survey was conducted that included questions about the respondent’s age, sex, race (African American/Black, Latino and other race/White), and whether the food was consumed in the restaurant or taken away by the customer. We also asked each adolescent or parent/caregiver respondent whether they noticed any calorie information posted in the establishment. If so, we asked whether the information influenced their food choice and whether this calorie information caused them to purchase more or fewer calories.

Adolescents were asked additional questions: whether they were with their parents at the restaurant; who decides what they eat at home; and how (if at all) what their parents want them to eat influences their decision making. We also asked adolescents what was most important to them in their fastfood choice (nutrition, taste or both), and the extent to which price mattered to them in their choice of what they had just purchased (on a 4-point scale from mattering ‘Not At All’ to ‘A Lot’). Using the same scale, we examined whether each of the following influenced their decision to go to the fast-food restaurant on that day: habit, ease, location and price. We also asked this group whether they limited the amount of food they ate to control their weight, as adapted from the restrained eating scale (responses on a 5-point scale from ‘Not at All’ to ‘Always’).

In addition, we asked adolescents to estimate the total amount of calories they consumed in the food and drink (separately) that they purchased, and compared this amount with the actual amount of calories purchased. We assumed that consumers were ‘correct’ if their estimate fell within 100 calories of the actual amount. To gather data on the knowledge of calories, we asked adolescents, ‘What do you think is the recommended daily calorie intake for an average American to maintain a normal weight?’ We asked this same question (about adults) to both adolescents and adults. Finally, to ascertain the role that parents had in adolescent food choice, we asked, if the parent/caregiver was present, the extent to which they influenced the adolescents’ food choice. If this individual was not present, we ascertained the extent to which the adolescent reported that parental preferences influenced their food choices more generally (4-point scale, ‘Not at All’ to ‘A Lot’) and who decided what they ate at home (adolescent or parent, or whether they decided together). We asked all parents who answered the survey for their children, who actually chose the food that was ordered: the parent or the child, or did they decide jointly. The survey took only a few minutes to complete for adolescents and only slightly longer for adults (given the additional questions on children’s eating habits).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study participants and to evaluate the distribution of key variables. Differences in the amount of calories purchased before and after labeling in NYC and Newark were examined for adolescents and children. For this and for other mean differences, the t-test and analysis of variance were used. For all differences in categorical variables, the χ2 statistic was used. Because of the very limited sample size, we were not able to perform multivariate analyses. The study review was conducted by the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. All analyses were carried out with SAS version 9.1. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Across New York and Newark, before and after labeling, a total of 427 children and adolescents were sampled. We excluded 78 respondents (18%) who indicted that they shared food listed on the receipt, as it was difficult to ascertain the relative amount of food eaten. Children and adolescents who came to the restaurant with a caretaker/parent comprised 69% of the study sample, with 31% visiting the restaurant alone. By design, 76% of our sample was drawn from NYC (see Table 1). Conditional on providing data on at least one child, parents/caregivers provided data on 1.4 children.

Table 1.

Descriptions of children and adolescents and their parent/caregiver

| Full sample (n =349)

|

NYC (n =266)

|

Newark (n =83)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N |

Pre-labeling

|

Post-labeling

|

Pre-labeling

|

Post-labeling

|

|||||

| % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | |||

| Total | 100 | 349 | 53 | 142 | 47 | 124 | 59 | 49 | 41 | 34 |

| Child was at restaurant | ||||||||||

| With caretaker/parent | 69 | 241 | 73 | 103 | 65 | 80 | 71 | 35 | 68 | 23 |

| Without caretaker/parent | 31 | 108 | 28 | 39 | 36 | 44 | 29 | 14 | 32 | 11 |

| Male | 47 | 164 | 46 | 66 | 49 | 61 | 37 | 18 | 56 | 19 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 0–6 | 20 | 69 | 18 | 26 | 23 | 28 | 14 | 7 | 24 | 8 |

| 7–12 | 26 | 92 | 28 | 40 | 46 | 57 | 24 | 12 | 18 | 6 |

| 13 or older | 54 | 188 | 54 | 76 | 31 | 39 | 61 | 30 | 59 | 20 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Black | 66 | 230 | 68 | 97 | 60 | 74 | 55 | 27 | 94 | 32 |

| Latino/a | 24 | 82 | 23 | 32 | 31 | 38 | 24 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| White/other | 11 | 37 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

| Order to stay (vs to go) | 39 | 132 | 38 | 52 | 42 | 52 | 40 | 19 | 26 | 9 |

| Post-labeling (vs pre) | 45 | 158 | ||||||||

| New York (vs Newark) | 76 | 266 | ||||||||

| Full sample (n =128) |

NYC (n =101)

|

Newark (n =27)

|

||||||||

| Pre-labeling | Post-labeling | Pre-labeling | Post-labeling | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Caretaker/parent characteristics | ||||||||||

| Total | 100 | 128 | 52 | 53 | 48 | 48 | 56 | 15 | 44 | 12 |

| Male | 13 | 17 | 19 | 10 | 42 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 25 | 3 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | 32 | 41 | 28 | 15 | 35 | 17 | 27 | 4 | 42 | 5 |

| 30–39 | 29 | 37 | 26 | 14 | 33 | 16 | 27 | 4 | 25 | 3 |

| 40–49 | 24 | 31 | 34 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 27 | 4 | 25 | 3 |

| 50 or older | 15 | 19 | 11 | 6 | 19 | 9 | 20 | 3 | 8 | 1 |

| Calories (mean, (s.d.)) | 554 | (445) | 526 | (464) | 595 | (420) | 650 | (434) | 408 | (487) |

Abbreviation: NYC, New York City.

Approximately 47% of the respondents were male. Adolescents aged 13–17 years made up 54% of our sample. In total, 66% of the participants identified themselves as Black, 24% were Latino and the remaining 11% were of mixed race or White. These demographic characteristics remained consistent across our two data collection periods, except that the Newark post-labeling sample included a higher proportion of Black respondents (94%). We also provide data on the parents/caretakers of the children in our sample. Only 13% were male, and approximately one-third were between the ages of 18 and 29 years.

Table 2 describes differences in the total amount of calories purchased, and whether this changed as a result of labeling. Overall, the 349 children and adolescents in our sample purchased an average of 645 calories; those without a caregiver tended to be older and purchased a higher amount of calories. We did not observe any differences before or after labeling in NYC or Newark. The same was true for male and female participants of various age groups. We did occasionally see a nonsignificant decrease (females <13 years old) as well as a nonsignificant increase (males ≥13 years) in calories consumed, but no consistent patterns emerged. Again, we note our limited sample size.

Table 2.

Mean calorie intake of children and adolescents from fast food

| Full sample (n = 349)

|

New York (n =266)

|

Newark (n =83)

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | s.d. | Pre-labeling

|

Post-labeling

|

P-value | Pre-labeling

|

Post-labeling

|

P-value | |||||||||

| N | Mean | s.d. | N | Mean | s.d. | N | Mean | s.d. | N | Mean | s.d. | ||||||

| Full sample | 349 | 645 | 330 | 142 | 643 | 334 | 124 | 652 | 330 | 0.82 | 49 | 611 | 366 | 34 | 673 | 265 | 0.37 |

| Child was at restaurant | |||||||||||||||||

| With caretaker | 241 | 609 | 321 | 103 | 610 | 327 | 80 | 595 | 319 | 0.76 | 35 | 609 | 347 | 23 | 650 | 268 | 0.62 |

| Without caretaker | 108 | 725 | 339 | 39 | 730 | 341 | 44 | 755 | 327 | 0.73 | 14 | 617 | 425 | 11 | 722 | 264 | 0.46 |

| Gender differences | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 164 | 684 | 340 | 66 | 681 | 352 | 61 | 686 | 348 | 0.93 | 18 | 735 | 367 | 19 | 636 | 250 | 0.35 |

| Female | 180 | 612 | 321 | 74 | 615 | 319 | 62 | 620 | 312 | 0.92 | 30 | 545 | 356 | 14 | 706 | 288 | 0.12 |

| Male 0–12 | 82 | 575 | 284 | 35 | 622 | 315 | 27 | 526 | 283 | 0.21 | 10 | 621 | 256 | 10 | 493 | 175 | 0.21 |

| Male 13 and up | 82 | 792 | 357 | 31 | 747 | 383 | 34 | 814 | 347 | 0.47 | 8 | 878 | 449 | 9 | 795 | 230 | 0.65 |

| Female 0–12 | 78 | 519 | 265 | 31 | 480 | 271 | 34 | 541 | 282 | 0.38 | 9 | 511 | 222 | 4 | 645 | 157 | 0.25 |

| Female 13 and up | 102 | 684 | 341 | 43 | 712 | 319 | 28 | 716 | 325 | 0.96 | 21 | 560 | 404 | 10 | 730 | 331 | 0.23 |

Note: P-value tests for differences between the pre vs post period within the same city (New York City or Newark).

Next, we examined whether adolescents noticed and/or indicated that they responded to calorie labels (Figure 1). No adolescent respondent said that they noticed the calorie labels in NYC and Newark before labeling began. After labeling began in NYC, 57% of the same group in NYC (and 18% in Newark) reported noticing calorie information. A total of 9% indicated that the labels influenced their meal choice; 9% also claimed that they purchased fewer calories as a result. In other words, of adolescents who reported noticing the labels, 16% reported that the information influenced their food choice.

Figure 1.

Adolescents noticing and indicating responses to calorie labels.

We next turned to the factors that adolescents described as influencing their fast-food choice, and examined whether these differences correlated with the amount of calories purchased (Table 3). Of the factors we examined, ‘ease’ mattered ‘some’ or ‘a lot’ for 57% of respondents. After this, location was the most important factor, with 48% of respondents falling into one of the categories (of course, these characteristics are likely correlated). Adolescents who indicated that these factors mattered purchased somewhat fewer calories.

Table 3.

Additional factors influencing adolescent fast-food choices, and their correlation with calories consumed

| Adolescents, n = 168

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | Mean | s.d. | P | |

| Factors influencing choice of restaurants | |||||

| Habit mattered | |||||

| Not at all | 38 | 64 | 756 | 372 | |

| A little | 21 | 35 | 756 | 320 | ANOVA |

| Some/a lot | 40 | 67 | 666 | 329 | P =0.26 |

| χ2 | P =0.000 | ||||

| Ease mattered | |||||

| Not at all | 22 | 37 | 766 | 337 | |

| A little | 20 | 33 | 817 | 413 | ANOVA |

| Some/a lot | 57 | 96 | 668 | 315 | P =0.07 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Location mattered | |||||

| Not at all | 40 | 67 | 799 | 361 | |

| A little | 12 | 20 | 698 | 360 | ANOVA |

| Some/a lot | 48 | 80 | 657 | 316 | 0.04 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Price mattered | |||||

| Not at all | 46 | 78 | 741 | 363 | |

| A little | 23 | 38 | 691 | 314 | ANOVA |

| Some/a lot | 30 | 50 | 708 | 344 | P =0.74 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Factors influencing choice of food | |||||

| What was important? | |||||

| Nutrition | 9 | 15 | 699 | 394 | |

| Taste | 72 | 121 | 722 | 325 | ANOVA |

| Both | 19 | 31 | 688 | 395 | P =0.88 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Price mattered | |||||

| Not at all | 30 | 51 | 679 | 296 | |

| A little | 19 | 31 | 732 | 316 | ANOVA |

| Some/a lot | 50 | 84 | 740 | 382 | P =0.59 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Factors influencing choice of food | |||||

| Limit food to control weight | |||||

| Not at all | 29 | 49 | 665 | 331 | |

| Seldom/sometimes | 43 | 72 | 733 | 331 | ANOVA |

| Often/always | 27 | 46 | 754 | 377 | P =0.41 |

| χ2 | P =0.03 | ||||

Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance. Note: χ2-tests for differences in response categories, and the ANOVA for differences in mean calories by response category.

Turning to the characteristics that adolescents used to determine which food to eat, taste was rated as most important by 72% of respondents, but these consumers did not appear to purchase more calories. As for price, 46% of consumers said this was not at all a factor in their choice. Finally, just over a quarter of adolescent consumers reported that they often, or always, limited the amount of food they ate in an attempt to control their weight, with an almost equal number never limiting food for this reason. This was not correlated with any difference in the number of calories purchased.

More accurate calorie information is a key benefit claimed for calorie labeling. As Table 4 indicates, a majority of adolescents underestimated the calorie counts for the meals that they purchased. In New York, 63% underestimated the total calories they purchased before labeling, and 59% did so afterward (n.s.). Of those who underestimated, the mean underestimate was 466 calories before labeling and 494 after labeling in NYC (n.s.). In response to the question determining the amount of calories an adult should consume to maintain a normal weight (Table 5), approximately a quarter of adolescents provided a number between 1500 and 2500. The vast majority of consumers underestimated the recommended calories, 63% before labeling in NYC and 61% after labeling.

Table 4.

Adolescents estimate of calories purchased vs actual calories purchased

| % in each group | NYC, pre-labeling (n =65)

|

% in each group | NYC, post-labeling (n =59)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated calories | Actual calories | Difference | Estimated calories | Actual calories | Difference | |||

| Overestimate | 18 | 989 | 559 | 430 | 24 | 1450 | 761 | 689 |

| Accurate | 11 | 449 | 454 | −5 | 15 | 513 | 549 | −36 |

| Underestimate | 63 | 311 | 777 | −466 | 59 | 341 | 835 | −494 |

| Missing | 8 | — | 642 | — | 2 | — | 810 | — |

Abbreviation: NYC, New York City. Note: Accurate refers to estimates being within 100 of the number of calories purchased.

Table 5.

NYC, adolescent estimates of calories that should be consumed by adults to maintain healthy weight

| Pre-labeling (%) | Post-labeling (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate over 2500 | 3 | 5 |

| Estimate between 1500 and 2500 | 23 | 25 |

| Estimate below 1500 | 63 | 61 |

| Missing | 11 | 8 |

Abbreviation: NYC, New York City.

Finally, another little understood aspect of child obesity concerns parental influence on food decisions in general, and fast-food decisions in particular. Approximately 30% of parents/caregivers indicated that the child chose what to eat that day, whereas 57% indicated that they chose for the child. For adolescents, in most cases (61%), no caregiver was present; the adolescents almost always chose what they ate by themselves. Only 30% of adolescents said that their parents had no influence on their food choice, with an almost equal number saying that they influenced their decisions ‘some’ or ‘a lot.’ Half of the adolescents reported that they decided what to eat at home, 24% indicated that their parent decided and the remaining (17%) reported that the decision was made jointly. There was no apparent trend toward greater parental involvement being associated with lower fast-food calorie consumption in our sample (Table 6).

Table 6.

Fast-food intake and decision making among families

|

Question asked of parent/caregiver about their child

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n =181

|

|||||

| % | N | Mean | s.d. | ||

| Who decided what the child ate today? | |||||

| Child | 31 | 57 | 501 | 251 | |

| Caretaker/parent | 57 | 103 | 630 | 322 | ANOVA |

| Together | 6 | 10 | 555 | 313 | P =0.04 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Questions asked of adolescents | |||||

|

n =168

|

|||||

| % | N | Mean | s.d. | ||

| Who decided what you ate at restaurant? | |||||

| Adolescent | 33 | 55 | 677 | 348 | |

| Caretaker | 1 | 2 | 655 | 502 | |

| Decided together | 3 | 5 | 1005 | 276 | ANOVA |

| Caretaker not present | 61 | 102 | 720 | 338 | P =0.23 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Who decides what you eat at home? | |||||

| Adolescent | 49 | 83 | 698 | 359 | |

| Caretaker/parent | 24 | 41 | 742 | 357 | ANOVA |

| Decided together | 17 | 28 | 750 | 313 | P =0.85 |

| χ2 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Caretaker influence on food choice? | |||||

| Not at all | 30 | 50 | 642 | 310 | |

| A little | 27 | 45 | 697 | 354 | |

| Some | 18 | 31 | 801 | 368 | ANOVA |

| A lot | 15 | 26 | 809 | 368 | P =0.18 |

| χ2 | P =0.02 | ||||

Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Discussion

Similar to adult respondents in the handful of other evaluation studies conducted to date on the effects of calorie labeling, adolescents and children in this study—a group of racial and ethnic minorities from low-income areas—did not respond in any measurable way to the presence of labels within our study time period. We note, though, that our study was not powered to find a very small change in the amount of calories purchased for these groups. Although adolescents did appear to notice labels at similar rates to adults, those who did notice the information reported responding to it at somewhat lower rates than adults. Just over a quarter of adults who noticed the information reported using it (Elbel et al.17); this was true of only 16% of adolescents.

Also of note are data on how adolescents make fast-food choices, both in coming to the restaurant and in deciding what to purchase. Most important for the latter were concerns such as ease and location, which even appeared to trump price for many adolescents. After entering the restaurant, taste was overwhelmingly what drove adolescent food choice. Adolescents are on average significantly underestimating the amount of calories in the fast food they purchase; although a few adolescents could properly estimate the amount of calories that adults should consume in a day, the majority provided estimates that are below 1500 calories. They could be misinterpreting the question and answering for themselves. If they truly believe that the daily caloric intake should be less than it actually is, then greater knowledge surrounding the proper amount of calories could give license for greater consumption of calories.

Another intriguing result involves the role of parents in influencing their children’s food choices. This topic has generated a complex array of research questions, including the extent to which children’s and adolescent’s diets are ‘co-constructed’ with parents,19 the effects of permissive vs restrictive ‘parenting styles’ on obesity and overweight,20,21 and whether parental intervention on food choices heightens child obesity, perhaps through inciting rebellious behavior.22 Our finding that parent–child joint food decision making did not dramatically change purchasing practices points to the need for further investigation.

Additional research is also necessary to determine whether menu labels can fruitfully be coupled with greater education regarding caloric content. Although as a general rule public education campaigns by themselves have not been found to affect obesity rates—among children or adults—one recent experimental study suggests that a combination of calorie labeling and ‘anchoring’ reminders of the recommended daily calorie intake can make a meaningful difference in consumption practices, at least among adults.23 However, another study carried out in a location more closely resembling a fast-food restaurant found no influence of labeling even when this prompt was present; in fact, male consumers ordered food with a greater amount of calories.24 NYC initiated an educational campaign (after our data collection) to inform residents that ‘2000 calories a day is all most adults should eat.’ To this end, the new national labeling law specifically requires ‘a succinct statement concerning suggested daily caloric intake, as specified by the Secretary by regulation and posted prominently on the menu and designed to enable the public to understand, in the context of a total daily diet, the significance of the caloric information that is provided on the menu.’25 However, given that few consumers overestimated recommended caloric consumption, it is unclear whether this information will provide a motivation to decrease caloric purchasing or provide a justification to purchase additional calories.

Calorie labeling could have the effect of dissuading some adolescents, or parents/caregivers with children, from visiting fast-food restaurants. We are not able to observe any such result, as we sampled only customers who entered a location that features labeling. If such avoidance behavior does exist, attention must be paid to consumers’ substitution behavior: where they are going instead—whether to restaurants with less healthy or healthier food—and what they are consuming at these locations.

Strengths and limitations

This study contributes in important ways to the limited existing research on point-of-purchase calorie labeling and its influence on children’s and adolescents’ food choices. In addition to sampling the same restaurants before and after the introduction of labeling, which limits the effects of differences across restaurants, our study examined labeling as it was implemented in the ‘real world,’ as opposed to a hypothetical or laboratory setting. Collection of food receipts from respondents allowed us to verify—and estimate the calorie content of—the food that consumers purchased. The narrow study period allowed us to better attribute any change in calories purchased to the introduction of labeling, eliminating other factors that could affect people’s food choices.26 Finally, we controlled for secular trends in food choice by including a comparison city in our study design.

The short study period mentioned above is also a limitation. The effects of labeling may well require a longer time to develop among a population; our results may have differed if we collected post-labeling data after a longer interval, particularly given that eating behaviors are incredibly resistant to change.27 However, we note that adult consumers in our sample reported visiting fast-food restaurants on average five times per week, suggesting repeated exposure to calorie labels before our follow-up data collection. 7 (Of course, this also means that the same consumer could be present in pre- and post-labeling data, although anecdotally this was rare.) It is not clear whether continued exposure beyond a month would make consumers more or less likely to respond to labels. In addition, the one study of which we are aware that does have a longer time period of data, on the basis of daily receipts from Starbucks, found the influence of labeling to be immediate and persistent, albeit very small (a 6% reduction in calories purchased per transaction).28

Second, the timing of our post-labeling data collection may involve some instability in the format of labels. Although all the locations we studied posted calorie labels, New York authorities had begun fining restaurants that were not in full compliance with regulations requiring specific font and placement.29 It is possible that labeling that is in full compliance with the regulation would alter our findings.

Third and finally, as noted above, our sample is not able to register small effects of labeling. Larger studies are needed to examine fully the influence of labeling on children and adolescents. We note, however, that small effects from labeling alone are not likely to influence obesity in a meaningful way, unless combined with other policy approaches to further contribute to a reduction in calories.30

Conclusion

This study examined the effects of menu labeling in a natural environment among children and adolescents in low-income communities, and assessed the practical effects of this now-national mandate. Our evaluation of NYC’s labeling law suggests that, although most parents and adolescents report seeing calorie information posted in restaurants, this public policy intervention had no significant effect on purchasing behavior within our study period for a low-income, racially and ethnically diverse population of parents and adolescents. Future studies should apply similar real-world tests across a larger cross-section of the population when menu labeling is implemented nationwide in the United States.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Healthy Eating Research program, Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, the NYU Wagner Dean’s Fund and the National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (R01HL095935). Special thanks to Kevin Lyu, Kristin Van Busum and Melinda Newe for their excellent research assistance, as well as to Courtney Abrams. We also express our appreciation to Kelly Brownell and Marion Nestle for their thoughtful advice on this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kersh R. The politics of obesity: a current assessment and look ahead. Milbank Q. 2009;87:295–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pomerantz J, Brownell KD. Legal and public health considerations affecting the success, reach, and impact of menu-labeling laws. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1578–1583. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity. Solving the problem of childhood obesity within a generation. Fed Regist. 2011:76. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.9980. forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360:473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman SA, Gortmaker SL, Ebbeling CB, Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey. Pediatrics. 2004;113:112–118. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes. 2001;25:1823–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbel B, Kersh R, Brescoll BL, Dixon LB. Calorie labeling and food choices: a first look at the effects on low-income people in New York City. Health Aff. 2009;28:w1110–w1121. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downs JS, Loewenstein G, Wisdom J. Strategies for promoting healthier food choices. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc. 2009;99:1–10. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto JA, Yamamoto JB, Yamamoto BE, Yamamoto LG. Adolescent fast food and restaurant ordering behavior with and without calorie and fat content menu information. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Contento IR, Williams SS, Michela JL, Franklin AB. Understanding the food choice process of adolescents in the context of family and friends. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Story MT, Wall MM, Harnack LJ, Eisenberg ME. Fast food intake: longitudinal trends during the transition to young adulthood and correlates of intake. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland LA, Beavers DP, Kupper LL, Bernhardt AM, Heatherton T, Dalton MA. Like parent, like child: child food and beverage choices during role playing. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2008;162:1063–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Rittenberry L, Olvera N. Social-environmental influences on children’s diets: results from focus groups with African-, Euro- and Mexican-American children and their parents. Health Educ Res. 2000;15:581–590. doi: 10.1093/her/15.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tandon PS, Wright J, Zhou C, Rogers CB, Christakis DA. Nutrition menu labeling may lead to lower-calorie restaurant meal choices for children. [Accessed 27 May 2010];Pediatrics. 2010 125:244–248. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1117. Available at http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/reprint/125/2/244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang TK, Story M. A journey just started: renewing efforts to address childhood. Obesity. 2010;18:S1–S3. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Zhang Q. Are American children and adolescents of low socioeconomic status at increased risk of obesity? Changes in the association between overweight and family income between 1971 and 2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:707–716. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bram J, McKay A. The evolution of commuting patterns in the New York City area. Fed Res Bank NY Current Issues Econ Finance. 2005;11:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology. Altamira Press; Lanham, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassett R, Chapman GE, Beagan BL. Autonomy and control: the co-construction of adolescent food choice. Appetite. 2008;50:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowne M. A comparative study of parental behaviors and children’s eating habits. Infant Child Adolesc Nutr. 2009;1:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wake M, Nicholson JM, Hardy P, Smith K. Preschooler obesity and parenting styles of mothers and fathers: Australian national population study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1353–1354. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar D. Childhood obesity treatment: targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. Brit J Nutr. 2006;95:1008–1015. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberto C, Larsen P, Agnew H, Baik J, Brownell K. Evaluating the impact of menu labeling on food choices and intake. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:312–318. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harnack LJ, French SA, Oakes JM, Story MT, Jeffery RW, Rydell SA. Effects of calorie labeling and value size pricing on fast food meal choices: results from an experimental trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:63. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.PPACA. [Accessed 1 June 2010];2010 Available at: http://www.foodlabelcompliance.com/Sites/5/Downloads/HR-3962-Div-C-Title-V-Subtitle-C-Sec-2572-Restaurant-Nutrition-Labeling-pp-1527-1536.pdf.

- 26.Sobal J, Bisogni CA, Devine C, Jastran M. A conceptual model of the food choice process. In: Shepherd R, Raats M, editors. The Psychology of Food Choice. 1. CABI; Cambridge, MA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew A, Samuels B, Chatman J. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol. 2007;62:220–233. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollinger B, Leslie P, Sorensen A. Calorie posting in chain restaurants. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2010. Working Paper 15648. Also available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w15648. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordova EB. Health department issues mass citations to food chains; McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts amass most calorie citations. Crain’s NY. 2008 Oct 20; [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katan MB, Ludwig DS. Extra calories cause weight gain but how much? JAMA. 2010;303:65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]