Smokers with human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS receiving a cell phone–based intervention with supportive counseling were more likely to demonstrate smoking abstinence over 12 months compared to smokers receiving usual care. The greatest impact was at 3 months, and intervention efficacy decreased over time.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, smoking cessation, cell phone intervention

Abstract

Background. People living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS (PLWHA) have a substantially higher prevalence of cigarette smoking compared to the general population. In addition, PLWHA are particularly susceptible to the adverse health effects of smoking. Our primary objective was to design and test the efficacy over 12 months of a smoking cessation intervention targeting PLWHA.

Methods. Participants were enrolled from an urban HIV clinic with a multiethnic and economically disadvantaged patient population. Participants received smoking cessation treatment either through usual care (UC) or counseling delivered by a cell phone intervention (CPI). The 7-day point prevalence abstinence was evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 months using logistic regression and generalized linear mixed models.

Results. We randomized 474 HIV-positive smokers to either the UC or CPI group. When evaluating the overall treatment effect (7-day abstinence outcomes from 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups), participants in the CPI group were 2.41 times (P = .049) more likely to demonstrate abstinence compared to the UC group. The treatment effect was strongest at the 3-month follow-up (odds ratio = 4.3, P < .001), but diminished at 6 and 12 months (P > .05).

Conclusions. Cell phone–delivered smoking cessation treatment has a positive impact on abstinence rates compared to a usual care approach. Future research should focus on strategies for sustaining the treatment effect in the long term.

The disproportionate burden of cigarette smoking among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS (PLWHA) represents a pressing public health problem. In contrast to the documented prevalence of smoking in the general United States population, substantial evidence indicates that smoking prevalence is 2–3 times higher among PLWHA, with estimates ranging from 45% to 70% [1]. Furthermore, PLWHA are particularly susceptible to the adverse health consequences of tobacco use, such as elevated risks of major cardiovascular disease, cancer, bacterial pneumonia, and overall mortality [2]. In fact, recent evidence from a large cohort study indicates that >60% of deaths among PLWHA can be attributed to smoking [3].

Although compelling evidence suggests that PLWHA suffer disproportionately from the negative health consequences related to smoking and would benefit considerably from smoking cessation treatment, few large-scale smoking cessation randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been conducted exclusively with PLWHA [4]. The few RCTs targeting PLWHA have not yielded statistically significant treatment effects on long-term smoking abstinence [5, 6]. However, several small pilot and demonstration trials have shown promising results for developing interventions that combine supportive counseling with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to enhance smoking abstinence in PLWHA [7–10].

In the current large-scale RCT (N = 474), a usual care approach was compared to an innovative cell phone counseling–based smoking cessation intervention in a sample of low-income, multiethnic, HIV-positive smokers. To our knowledge, this is the largest smoking cessation intervention study exclusively targeting PLWHA conducted to date, and among the few to focus on the unique needs of an economically disadvantaged population of PLWHA. The 3-month outcomes from this trial showed that participants receiving the cell phone–based smoking cessation intervention were 4.3 times more likely to be abstinent compared to those individuals receiving usual care (P < .001) [11]. In this report, the long-term smoking-related outcomes from our intervention trial up through the 12-month follow-up are described.

METHODS

Participants and Screening

Study participants were recruited from Thomas Street Health Center, a county-operated HIV clinic serving a predominantly low-income, medically indigent patient population. A total of 474 participants were recruited between February 2007 and December 2009. Research staff screened all clinic patients for eligibility as they arrived for primary care appointments. Inclusion criteria were as follows: HIV-positive, age ≥18 years, current smoker (≥5 cigarettes daily and expired carbon monoxide [CO] level of ≥7 ppm), willing to set a quit date within 7 days, and ability to speak English or Spanish. Exclusion criteria included current enrollment in another smoking cessation program and/or physician-deemed ineligibility based on medical or psychiatric conditions.

Study Design and Procedures

After obtaining informed consent, participants completed an audio computer–assisted self-interview (ACASI), then received provider advice to quit smoking. Subsequently, participants were randomized to 1 of 2 treatment groups: usual care (UC) vs cell phone intervention (CPI). Both the UC and CPI treatments were informed by recommendations from the Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline [12]. Participants assigned to the UC group were provided with targeted written smoking cessation materials (ie, a “tip sheet” designed to address concerns of HIV-positive smokers) and instructions on how to obtain NRT in the form of nicotine patches at the clinic.

Participants assigned to the CPI group received the UC components plus a cell phone–delivered counseling intervention over 3 months and access to a supportive hotline. The CPI was designed to (1) reduce access to care barriers, (2) provide an intensive level of support, and (3) meet the special needs of the target population. Counseling content was drawn from cognitive-behavioral and motivational interviewing techniques that are empirically supported in the literature for smoking cessation [12]. Further description of counseling session content, call schedule, and call completion rates have been previously published [11]. Participants in the CPI group were provided with a prepaid cell phone. All counselors were trained and supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist.

Follow-up assessments were conducted at 3, 6, and 12 months postenrollment, and included an ACASI and biological confirmation of smoking status using expired CO. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Additional details about treatment, study design, follow-up, and assessment procedures have been previously published [11].

Baseline and follow-up assessments included measures to assess demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial characteristics. Tobacco-related items administered at baseline included age of smoking initiation, number of cigarettes smoked per day, and quit attempt history. At follow-up, items were administered to assess smoking abstinence (24-hour, 7-day, and 30-day), number of quit attempts, length of abstinence (in days), use of NRT, use of other cessation treatments, and exposure to other forms of tobacco. Other smoking-related measures included the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [13]; the Reasons for Quitting scale (intrinsic and extrinsic quit motivation) [14]; and the 9-item quitting self-efficacy scale [15]. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 20-item Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) [16], and current anxiety was assessed with the State component of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [17]. Quality of life (QOL) was assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV), which provided both mental and physical functional status summary scores [18]. Alcohol use was measured with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [19]. A single item was used to assess illicit drug use in the past month.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed separately for the UC and CPI groups, and included generating means, standard deviations, and frequencies of demographic, psychosocial, tobacco-related, and alcohol and illicit drug use variables at baseline. A series of univariable regression models were used to evaluate baseline differences of potential confounders between the 2 treatment groups; statistical significance was tested using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence was the primary outcome measure for smoking abstinence, and 24-hour and 30-day abstinence were assessed as secondary outcomes. Expired CO level was used to biochemically verify self-reported smoking status. Thus, participants who self-reported abstinence but had a CO level of ≥7 ppm were coded as smokers. All smoking abstinence outcomes were expressed as dichotomous variables. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used to evaluate the overall treatment effect on each of the abstinence outcomes. The primary outcome of smoking abstinence was repeatedly measured at different time points (3, 6, and 12 months) for each participant; therefore, GLMM was utilized in this analysis as it can accommodate repeated measures and within-subject correlations [20]. GLMM can also handle missing data without imputing values. All GLMM models for this analysis used a logit link function and binomial error variance to generate odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs). All models included variables for follow-up time point and age as fixed effects, and subject as a random effect. An interaction term between follow-up visit and treatment group was used to evaluate whether the treatment effect varied statistically over time.

All analyses were conducted using an intent-to-treat (ITT) approach (those lost to follow-up are coded as smokers) and then repeated using a complete case (CC) approach (only included data on participants who completed at least 1 of the follow-up assessments) [21]. All analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

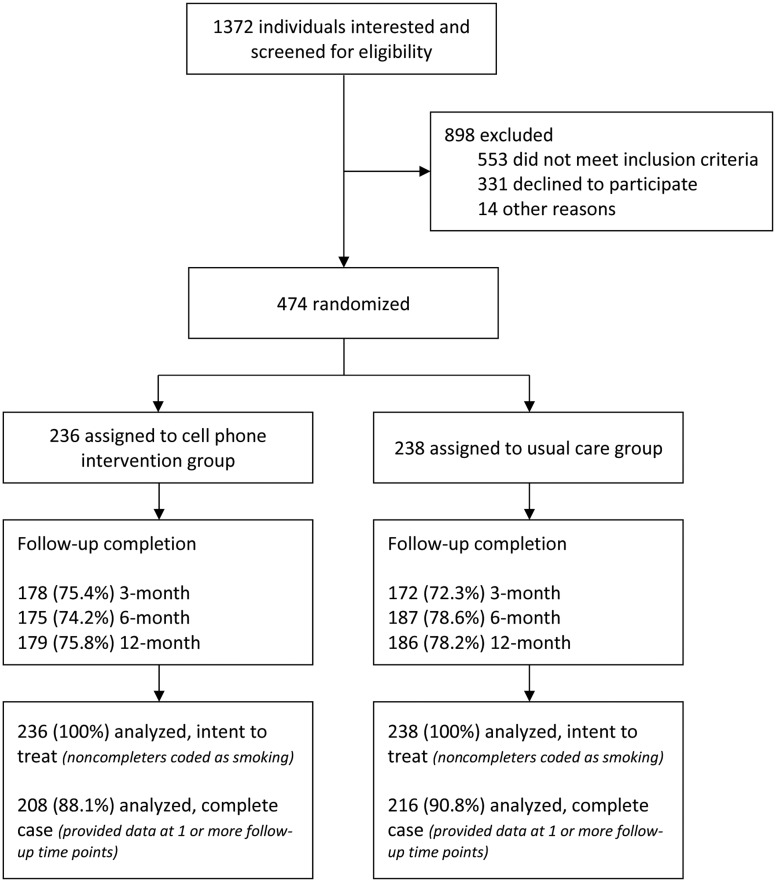

We screened a total of 1372 individuals for this study, and 553 were excluded due to failure to meet the study inclusion criteria (Figure 1). A total of 474 participants were randomized to the UC group (n = 238) or the CPI group (n = 236). Participant follow-up rates at 3, 6, and 12 months postenrollment were 73.8%, 76.4%, and 77.0%, respectively; there were no statistically significant differences in follow-up rates between the treatment conditions. Baseline characteristics by treatment group are presented in Table 1. The treatment groups were balanced with regard to demographic, psychosocial, tobacco-related, and alcohol and illicit drug use variables at baseline. With the exception of age, there were no statistically significant differences in the baseline variables between the treatment conditions.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram, showing screening, study enrollment, and retention through 12-month follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants, by Treatment Group

| Characteristic | Cell Phone Intervention Group (n = 236) | Usual Care Group (n = 238) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||

| Age, y, mean (SD)* | 43.9 (8.3) | 45.7 (7.8) |

| Women | 68 (28.8) | 74 (31.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 30 (12.7) | 29 (12.2) |

| Black/African American | 176 (74.6) | 185 (77.7) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 24 (10.2) | 19 (8.0) |

| Other | 6 (2.5) | 5 (2.1) |

| Years of formal education, mean (SD) | 10.9 (2.7) | 10.8 (2.5) |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 94 (39.8) | 88 (37.0) |

| High school or equivalent | 89 (37.7) | 91 (38.2) |

| More than high school | 53 (22.5) | 59 (24.8) |

| Current employment status | ||

| Working full or part time | 53 (22.5) | 47 (19.7) |

| Not working due to health | 143 (60.6) | 157 (66.0) |

| Unable to find work | 20 (8.5) | 16 (6.7) |

| Not working for other reasons | 20 (8.5) | 18 (7.6) |

| HIV transmission | ||

| Male homosexual contact | 62 (26.4) | 57 (24.1) |

| Heterosexual contact | 108 (46.0) | 107 (45.2) |

| Injection drug use | 34 (14.5) | 47 (19.8) |

| Other | 31 (13.2) | 26 (11.0) |

| Married/living with partner | 39 (16.5) | 45 (18.9) |

| Psychosocial variables | ||

| Depression (CES-D score), mean (SD) | 22.0 (11.2) | 21.5 (11.4) |

| CES-D scores ≥16 | 167 (70.8) | 152 (63.9) |

| Anxiety (STAI, state score), mean (SD) | 43.6 (13.6) | 43.0 (13.2) |

| Physical health summary (MOS-HIV PHS score), mean (SD) | 39.8 (11.2) | 40.3 (10.4) |

| Mental health summary (MOS-HIV MHS score), mean (SD) | 41.9 (11.4) | 42.3 (11.1) |

| Tobacco-related variables | ||

| Age of smoking initiation, y, mean (SD) | 18.2 (9.0) | 17.4 (6.8) |

| Cigarettes smoked per day, mean (SD) | 18.6 (11.3) | 19.7 (11.8) |

| Nicotine dependence (FTND score), mean (SD) | 5.73 (2.3) | 5.82 (2.3) |

| Previous quit attempt | 137 (58.1) | 145 (60.9) |

| Another smoker in home | 133 (56.3) | 113 (47.5) |

| Smoking self-efficacy, mean (SD) | 24.9 (9.1) | 25.8 (8.4) |

| Intrinsic quit motivation, mean (SD) | 38.4 (9.1) | 38.7 (8.7) |

| Extrinsic quit motivation, mean (SD) | 27.3 (8.7) | 28.1 (9.4) |

| Alcohol and illicit drug use | ||

| Alcohol use (AUDIT score), mean (SD) | 5.8 (8.2) | 6.1 (8.3) |

| AUDIT score ≥8 | 68 (28.8) | 78 (32.8) |

| Illicit drug use in past 30 d | 99 (42.0) | 91 (38.2) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CES-D, Centers for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression scale; FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MHS, Mental Health Survey; MOS-HIV, Medical Outcomes Study–HIV Health Survey; PHS, Physical Health Survey; SD, standard deviation; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

*P < .05.

The sample was 70.0% male, 76.2% African American, and 17.7% married (or living with a significant other). The majority of the sample was unemployed at baseline (78.9%), primarily due to health reasons (49.2%), and 38.4% had less than a high school education. The primary mode of self-reported HIV acquisition was heterosexual contact (45.6%); participants also reported HIV transmission via men having sex with men (25.2%) and injection drug use (17.2%). The mean age at baseline was 44.8 (SD, 8.1) years. Mean age was the only baseline variable with a statistically significant difference between the 2 treatment conditions (UC = 45.7 [SD, 7.8] and CPI = 43.9 [SD, 8.3]; P = .017), and therefore age was adjusted for in all regression models when evaluating smoking abstinence outcomes.

More than half the sample (67.3%) reported high levels of depressive symptoms at baseline (CES-D ≥ 16). Overall, the study sample reported poor physical and mental functional status when assessing QOL using the MOS-HIV Physical Health Summary (PHS) score and the Mental Health Summary (MHS) score. Both summary scores were below the population mean of 50, with participants reporting an average PHS score of 40.0 (SD, 10.8) and MHS score of 42.1 (SD, 11.2) at baseline. Approximately 31% of participants were classified as having a harmful or hazardous level of alcohol use (AUDIT score ≥ 8), and 40.1% reported using illicit drugs in the past 30 days. At baseline, participants reported smoking a mean of 19.2 (SD, 11.5) cigarettes per day, and 51.9% reported living with other smokers. The mean FTND score was 5.8 (SD, 2.3) indicating an overall, moderately high level of nicotine dependence [13].

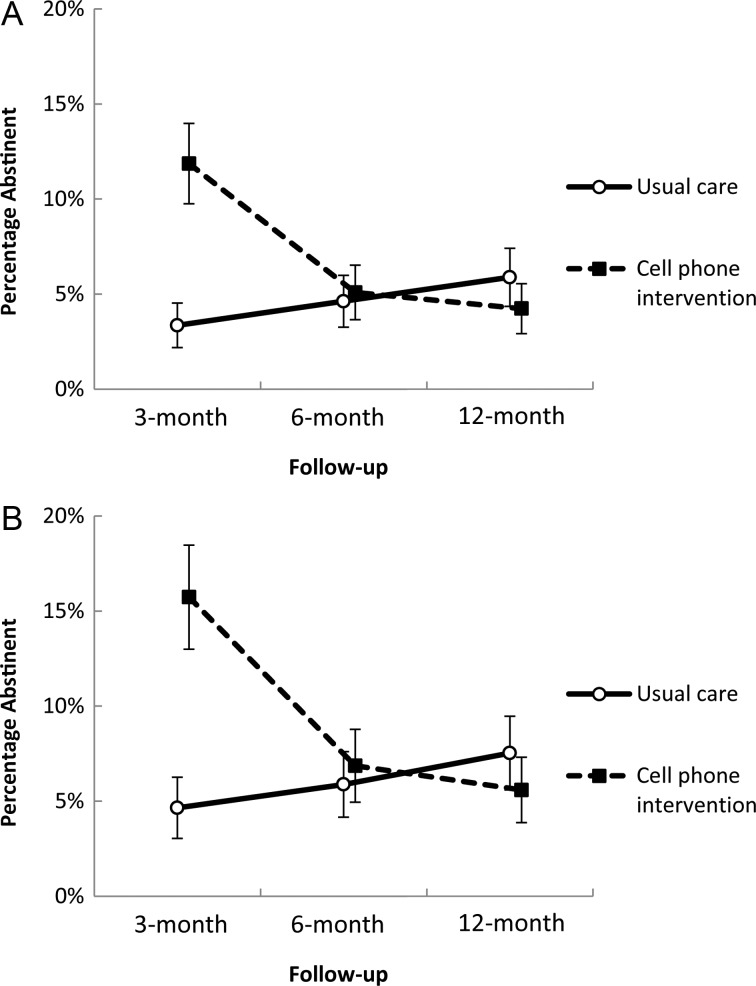

The overall treatment effect on smoking abstinence outcomes are presented in Table 2. For the primary outcome—7-day point prevalence abstinence through 12-month follow-up—results from ITT analysis indicated that participants in the CPI group were 2.41 times (95% CI, 1.01–5.76) more likely to be abstinent compared to those in the UC group. Results are similar when evaluating 7-day abstinence using the CC approach (OR = 2.46 [95% CI, 1.03–5.94]). Evaluation of the secondary smoking abstinence outcomes, 24-hour abstinence and 30-day abstinence, yielded similar ORs to those for 7-day abstinence (ORs ranging between 2.20 and 2.47). Inclusion of the interaction term for follow-up time point by treatment group in the GLMM model yielded a statistically significant change in slope (P < .0001), indicating that the treatment effect varied over each follow-up time point. This is further illustrated in Figure 2, which presents the prevalence of 7-day abstinence at the individual follow-up time points by treatment group. Participants randomized to the CPI group were 4.3 times (95% CI, 1.9–9.8) more likely to report smoking abstinence at 3 months after study enrollment compared to those in the UC group when using ITT analysis; when using CC analysis, the results were similar, yielding an OR of 4.5 (95% CI, 2.0–10.3). The treatment effect evident at the 3-month time point diminished when evaluating abstinence at the 6- and 12-month follow-up time points (P > .05).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Smoking Abstinence Outcomes for Participants Randomized to the Cell Phone Intervention Group vs the Usual Care Group

| Smoking Abstinence, Using Data Through 12-mo Follow-up | Intent-to-Treat (N = 474) |

Complete Case (n = 423) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Primary | ||||

| 7-d | 2.41 (1.01–5.76) | .049 | 2.46 (1.03–5.94) | .044 |

| Secondary | ||||

| 24-h | 2.36 (1.28–4.38) | .006 | 2.47 (1.31–4.64) | .005 |

| 30-d | 2.20 (.83–5.83) | .114 | 2.29 (.85–6.15) | .133 |

All estimates generated using generalized linear mixed-model regression using a logit link function. Models adjusted for fixed effect of time (follow-up time point) and age, and random effect of subject.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Figure 2.

Smoking abstinence by treatment group, showing the percentage of participants in each treatment condition (usual care vs cell phone intervention) who reported 7-day smoking abstinence at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up periods. Bars represent the standard error of the mean. A and B, Percentage abstinent using the intent-to-treat and complete-case approach, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to develop and implement a smoking cessation intervention intended to address the complex medical and social needs encountered by PLWHA from low-income and multiethnic backgrounds. To this end, we provided participants with prepaid cell phones, given the lack of resources and unstable telephone service among the population. The proactive telephone calls were designed to address HIV-specific issues, such as treatment response and risk of HIV-related diseases. Cognitive and behavioral components were designed to help modify thoughts and behaviors that serve as barriers to quitting smoking and remaining abstinent. Finally, the motivational component was designed to address fluctuations in quit motivation and promote greater self-efficacy for quitting smoking during the treatment delivery phase. We believe that the objective success in demonstrating a significant treatment effect in the CPI group compared to the UC group attests to the targeting and personalization of the interventions for PLWHA, combined with the focus on delivering empirically validated treatment strategies for smoking cessation. However, these findings show that absolute quit rates were low in both CPI and UC groups and diminished over time. Substantial work remains to be accomplished to assist this underserved population in tobacco cessation.

Several aspects of this study deserve further comment. First, participants were selected based on a demonstrated level of smoking (≥5 cigarettes/day and expired breath CO ≥7 ppm), leading to the exclusion of 40.3% of the smokers who were screened (Figure 1). Even participants who did not reach the screening cutoffs applied in this study are likely to have substantial levels of nicotine dependence. Population-level data indicate that African American and Hispanic individuals smoke fewer cigarettes per day compared to white individuals, yet remain nicotine dependent [22]. The exact reasons for this trend of lighter smoking are not known, but the lack of economic resources to purchase cigarettes for daily use may be a contributing factor. Given that HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minorities and low-income populations [23], future smoking cessation efforts should be more inclusive of lighter and nondaily smokers.

As previously mentioned, the absolute quit rates in both the CPI and UC treatment groups were low. This may be due to low NRT utilization and high nicotine dependence among this sample of PLWHA smokers. Although all participants received information for obtaining free NRT, the actual utilization rate was low and likely due to requirements imposed by the county clinic to participate in additional classes to receive NRT. Several characteristics of the study sample indicate a moderately high level of nicotine dependence, including a mean FTND score of 5.8, a high rate of alcohol and illicit drug use [24–26], and a substantial rate of poly-tobacco use (21.6%), including cigars and smokeless tobacco [27, 28]. Consequently, greater utilization of NRT might have positively affected quit rates in this dependent sample of smokers [12, 29]. The importance of NRT is further supported by the findings of Lloyd-Richardson and colleagues, who reported that NRT adherence was predictive of abstinence among PLWHA enrolled in a cessation trial [5].

Other important descriptors of our sample at baseline were the high levels of depressive symptoms and poor mental and physical health functional status. There is a substantial burden of mental illness among smokers and PLWHA, and persons suffering from depression are known to have lower quit rates than nondepressed individuals [30–33]. Again, pharmacological support has been shown to differentially benefit such persons [34, 35]. Finally, although our intervention featured personalized counseling to address barriers to cessation, we were not able to directly connect study participants to social services, mental health counselors, drug abuse counselors, or other specialties to address their real-world problems. Thus, we are currently developing an intervention that incorporates such features into our future research.

The strengths of this study include its large sample size and its urban, multiethnic population representative of PLWHA, 2 elements that few prior studies have matched. Because we used expired breath CO to verify self-report of smoking abstinence and classified those who did not meet the criterion as smokers, we had a particularly rigorous measure of abstinence. Other studies that used only self-report may be subject to reporting bias.

Limitations include use of a single HIV clinic, albeit a county site with a large patient population. Furthermore, the study was not designed to test whether the intervention would have been more effective if delivered at a given stage of HIV diagnosis or treatment (eg, at initial diagnosis; successful course of antiretroviral treatment as defined by CD4 count or viral load; or disease progression). Research is currently under way to address the point of optimal smoking cessation treatment. Furthermore, our design did not permit a more nuanced efficacy assessment of the specific counseling treatment components. The use of expired CO to validate smoking status is also a potential limitation. Misclassification of smoking status may have occurred due to marijuana use (ie, marijuana users could have incorrectly been classified as smokers). Alternatively, the relatively short half-life of CO may have also resulted in misclassification (ie, smokers could have been coded as abstinent due to low CO levels). However, CO-related misclassification would likely be nondifferential and have little or no impact on the treatment effect outcomes.

In the absence of evidence-based cessation programs for PLWHA and HIV-specific clinical smoking guidelines, recent recommendations call for clinical, behavioral, and systems-based research tailored to the unique medical and social needs of PLWHA [4, 36]. It is well recognized that PLWHA from economically disadvantaged backgrounds face significant barriers that subsequently prevent this population from participating in smoking cessation programs. Barriers germane to economically disadvantaged PLWHA include transportation difficulties, lack of resources including telephones, competing medical and social needs, high frequency of household moves, and limited access to smoking cessation programs [37–39]. This study is unique as it aims to address these barriers by using cell phone technology to deliver treatment. Future studies have an imperative to make pharmacologic and behavioral support readily available to this target population, and to continue to tailor interventions to address the specific needs of PLWHA.

This is among the first large-scale RCTs of a smoking cessation intervention for PLWHA. The use of a proactive cell phone–based intervention that combined supportive counseling, motivational intervention, and materials/topics targeted to PLWHA was successful compared to an UC intervention that included physician advice to quit and tip sheets. However, the intervention effect declined over time, with the greatest impact occurring at the 3-month follow-up. The findings indicate that, while efficacious, the CPI effect is not well sustained beyond the 3-month treatment period, suggesting that an extended intervention approach may be beneficial. Future studies will address sustaining the intervention effect, raising the overall absolute quit rates, and reducing real-life barriers to cessation associated with psychiatric comorbidity, as well as environmental and lifestyle characteristics of this underserved population.

Notes

Acknowledgments. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01CA097893 to E. R. G. and P30CA16672 to R. DePinho).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Vidrine DJ. Cigarette smoking and HIV/AIDS: health implications, smoker characteristics and cessation strategies. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3 suppl):3–13. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, van den Berg-Wolf M, Labriola AM, Read TR. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1896–903. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1-infected individuals: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:727–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds NR. Cigarette smoking and HIV: more evidence for action. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3 suppl):106–21. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Richardson EE, Stanton CA, Papandonatos GD, et al. Motivation and patch treatment for HIV+ smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104:1891–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moadel AB, Bernstein SL, Mermelstein RJ, Arnsten JH, Dolce EH, Shuter J. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored group smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:208–15. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182645679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummins D, Trotter G, Moussa M, Turham G. Smoking cessation for clients who are HIV-positive. Nurs Stand. 2005;20:41–7. doi: 10.7748/ns2005.11.20.12.41.c4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elzi L, Spoerl D, Voggensperger J, et al. A smoking cessation programme in HIV-infected individuals: a pilot study. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:787–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wewers ME, Neidig JL, Kihm KE. The feasibility of a nurse-managed, peer-led tobacco cessation intervention among HIV-positive smokers. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2000;11:37–44. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidrine DJ, Arduino RC, Lazev AB, Gritz ER. A randomized trial of a proactive cellular telephone intervention for smokers living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2006;20:253–60. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198094.23691.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vidrine DJ, Marks RM, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. Efficacy of cell phone-delivered smoking cessation counseling for persons living with HIV/AIDS: 3-month outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:106–10. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. In: Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al., editors. Service USDoHaHSPH. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curry S, Wagner EH, Grothaus LC. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:310–6. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. A comparison of four self-report smoking cessation outcome measures. Addict Behav. 2004;29:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith RC, Lay CD. State and trait anxiety: an annotated bibliography. Psychol Rep. 1974;34:519–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu AW, Hays RD, Kelly S, Malitz F, Bozzette SA. Applications of the Medical Outcomes Study health-related quality of life measures in HIV/AIDS. Qual Life Res. 1997;6:531–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1018460132567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied mixed models in medicine. 2nd ed. West Sussex, England: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Health and Human Services. Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998. Tobacco use among U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vol 21. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. Diagnosis of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Degenhardt L, Hall W. The relationship between tobacco use, substance-use disorders and mental health: results from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:225–34. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldman JG, Minkoff H, Schneider MF, et al. Association of cigarette smoking with HIV prognosis among women in the HAART era: a report from the women's interagency HIV study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1060–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vidrine DJ, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. The effects of smoking abstinence on symptom burden and quality of life among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:659–66. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klesges RC, Ebbert JO, Morgan GD, et al. Impact of differing definitions of dual tobacco use: implications for studying dual use and a call for operational definitions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:523–31. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tami-Maury I, Vidrine DJ, Fletcher FE, Danysh HE, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. Society on Research for Nicotine and Tobacco 19th Annual International Meeting. Boston, MA: 2013. Impact of innovative smoking cessation interventions for HIV-positive smokers who are multiple tobacco product users. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biener L, Hamilton WL, Siegel M, Sullivan EM. Individual, social-normative, and policy predictors of smoking cessation: a multilevel longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:547–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blalock JA, Lam C, Minnix JA, et al. The effect of mood, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders on smoking cessation in cancer patients. J Cogn Psychother. 2011;25:82–96. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.25.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penzak SR, Reddy YS, Grimsley SR. Depression in patients with HIV infection. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57:376–86. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.4.376. quiz 87–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness—United States, 2009–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:81–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnoll RA, Martinez E, Tatum KL, et al. A bupropion smoking cessation clinical trial for cancer patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:811–20. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cinciripini PM, Lapitsky L, Seay S, Wallfisch A, Meyer WJ, Van Vunakis H. A placebo-controlled evaluation of the effects of buspirone on smoking cessation: differences between high- and low-anxiety smokers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15:182–91. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nahvi S, Cooperman NA. Review: the need for smoking cessation among HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3 suppl):14–27. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honjo K, Tsutsumi A, Kawachi I, Kawakami N. What accounts for the relationship between social class and smoking cessation? Results of a path analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:2110–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazev A, Vidrine D, Arduino R, Gritz E. Increasing access to smoking cessation treatment in a low-income, HIV-positive population: the feasibility of using cellular telephones. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:281–6. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001676314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]