Abstract

Our understanding of human type 1 natural killer T (NKT) cells has been heavily dependent on studies of cells from peripheral blood. These have identified two functionally distinct subsets defined by expression of CD4, although it is widely believed that this underestimates the true number of subsets. Two recent studies supporting this view have provided more detail about diversity of the human NKT cells, but relied on analysis of NKT cells from human blood that had been expanded in vitro prior to analysis. In this study we extend those findings by assessing the heterogeneity of CD4+ and CD4− human NKT cell subsets from peripheral blood, cord blood, thymus and spleen without prior expansion ex vivo, and identifying for the first time cytokines expressed by human NKT cells from spleen and thymus. Our comparative analysis reveals highly heterogeneous expression of surface antigens by CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets and identifies several antigens whose differential expression correlates with the cytokine response. Collectively, our findings reveal that the common classification of NKT cells into CD4+ and CD4− subsets fails to reflect the diversity of this lineage, and that more studies are needed to establish the functional significance of the antigen expression patterns and tissue residency of human NKT cells.

Keywords: CD1-restricted/natural killer T (NKT) cells, immune regulation, NKT cells

Introduction

Type 1 natural killer T (NKT) cells (referred to hereafter as NKT cells) are a regulatory lineage of T cells that express a semi-invariant, CD1d-restricted T cell receptor (TCR) specific for glycolipid antigens [1]. Many immune activities are attributed to NKT cells, although they are associated most often with providing effective immunity against cancer, infections and autoimmune diseases [2–4]. Given these varied roles [5,6], it is surprising (and an issue of conjecture [7,8]) that usually only the CD4+ and CD4− subsets of mature human NKT cells are assayed when clinically assessing the human NKT cell pool [9]. CD4+ NKT cells produce cytokines associated with T helper type 0 (Th0) responses, and CD4− NKT cells are associated with Th1 responses [10,11]. The extent to which additional functionally distinct human NKT cell subsets exist is not known, but others have been defined in mice, and human NKT cells express differentially several cell surface antigens used to define conventional T cell subsets [8,10–13]. A recent study showed that both the CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets were highly heterogeneous in their expression of cell surface antigens and cytokine production, which suggested that unidentified functionally distinct subsets may exist within both these subsets [14]. This was an important finding, however, similar to earlier reports that examined the significance of CD8 expression by human NKT cells [15,16], the study used expanded NKT cell lines to obtain sufficient cell numbers and it is uncertain whether or not the phenotype of the expanded cells accurately reflected the in situ (i.e. non-expanded) human NKT cell pool.

Like many other NKT cell studies, the analysis was conducted using only NKT cells sourced from peripheral blood. This is an important issue to consider because, although analysis of blood is the dominant source of cells for assessing patient immunity, NKT cell tissue location is an important determinant of their function in mice [17]. Mouse studies have also shown that the profile of blood NKT cells often does not reflect NKT cells from other tissue sites [18]. It is not known whether this also applies to human NKT cells, although NKT cells from human thymus are functionally unresponsive compared to blood-derived NKT cells [19] and liver NKT cells are distinct from blood NKT cells in their expression of cell surface proteins [20].

In this study, we characterize the heterogeneity of the human NKT cell pool by analysing cell surface antigen and cytokine expression of the overall NKT cell pool and of the CD4+ and CD4− subsets from different tissues, with an emphasis on testing freshly isolated, rather than in-vitro-expanded, NKT cells. We detail significant heterogeneity within the established CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets from peripheral blood, thymus, spleen and cord blood and identify several candidate antigens where differential expression correlates with distinct patterns of cytokine production by blood-derived NKT cells. Our findings provide a platform for an improved understanding of the complex organization of the normal human NKT cell pool.

Materials and methods

Tissue origin and isolation of lymphocytes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from anti-coagulated blood of healthy donors (Australian Red Cross Blood Bank Service, Melbourne, Australia) and from cord blood from the Royal Children's Hospital (Melbourne, Australia). Thymus tissue was obtained from cardiac surgery patients at the Royal Children's Hospital (Melbourne, Australia). Our group's analysis of human NKT cells is part of an ongoing study and, as such, a proportion of the collective thymus and adult blood samples represented in this study was represented in collective data that formed part of earlier independent studies published by our group. Spleen was obtained from organ donor subjects (Melbourne, Australia). Informed consent was obtained from all donors or their legal guardians. The research was approved by one or more of the Health Sciences Human Ethics Committee (University of Melbourne), the Ethics in Human Research Committee (Royal Children's Hospital), the Human Research Ethics Committee (Royal Melbourne Hospital) and the Human Research Ethics Committee (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research).

PBMCs were isolated by gradient centrifugation using Histopaque (density 1·077 g/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Thymus tissue was pushed through a stainless steel sieve into complete media (RPMI-1640 medium; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KA, USA), 15 mM HEPES (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 0·1 mM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 2 mM glutamax (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich).

Spleen was digested in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 2 mg/ml collagenase and 0·5 mg/ml DNase at room temperature for 20 min with frequent pipetting; 20 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) was added to stop digestion and undigested fragments were filtered through a stainless steel sieve. Splenocytes were then overlayed on Ficoll and lymphocytes were isolated by gradient centrifugation. PBMCs and splenocytes were usually cryopreserved initially at −80°C [in 10% dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), 90% fetal bovine serum] before transfer to liquid nitrogen storage. Viability of thawed cells was typically > 90%.

NKT cells were isolated from PBMCs by magnetic bead-mediated enrichment and/or fluorescence-activated cell sorting. For magnetic bead enrichment, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated, alpha-galactosylceramide (αGalCer)-loaded CD1d tetramer-labelled PBMCs were incubated with anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and passed through an LS column (Miltenyi Biotech) on a MACS Separator (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PBMCs were eluted subsequently into complete media and prepared for cell sorting on a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Aria (BD Biosciences).

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Antibodies included: PE-conjugated anti-leucocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1 (LAIR-1) (DX26), PE-cyanin 7 (Cy7)-conjugated anti-CD3 (SK7) and anti-CCR7, Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-CD4 (RPA-T4) and anti-CD3 (UCHT), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD25 (M-A251), anti-CD45RA (HI100), anti-CD62L (Dreg 56), anti-CD16 (3G8), anti-CD127 (hIL-7R-M21), anti-interferon (IFN)-γ (B27) and anti-immunoglobulin (Ig)G1, allophycocyanin (APC)-H7-conjugated anti-CD8 (SK1), APC-conjugated anti-CD94 (HP-3D9), anti-CD56 (N-CAM), anti-IFN-γ (B27), anti-IL-4 (MP4-25D2), anti-IgG1, AlexaFluor 700-conjugated anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) (MAb11) used for FACs staining were all purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). APC-conjugated anti-CD161 was purchased from Miltenyi Biotech. PE-conjugated CD84 was a generous gift from Dr Stuart Tangye (Sydney, Australia). APC-conjugated CD154 (24–31) was purchased from Biolegend. The generation of PE-conjugated αGalCer-loaded and unloaded CD1d tetramer has been described previously. PE-conjugated αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer is produced in-house from a construct provided originally by Professor M. Kronenberg. The αGalCer (PBS44) was derived either from Alexis Biochemicals, Lausanne, Switzerland or from Dr Paul Savage (C24:1 PBS-44 analogue; Brigham Young University, UT, USA). Intracellular staining for cytokines was performed using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus Kit (BD Biosciences), as per the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry data was acquired using a LSRII or FACScanto flow cytometer (BD) and analysed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). Analysis excluded autofluorescent cells, doublets and non-viable cells on the basis of forward-/side-scatter and staining by 7-aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and vehicle-loaded CD1d tetramer [21].

Cell culture

For in-vitro stimulation of PBMCs, a minimum of 4 million cells were cultured in 12-well plates in 2 ml cell culture medium containing 10 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 μg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 μM monensin (Golgistop; BD Biosciences) for 4 h. Cells were then prepared for flow cytometric analysis of intracellular IFN-γ, TNF and IL-4 using the Cytofix/Cytoperm staining kit (BD Biosciences). Sorted NKT cell subsets were cultured in 96 well v-bottomed plates in a maximum of 50 μl of complete media containing 10 ng/ml PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 μg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h. Supernatants were subsequently removed, frozen and stored at −80°C for cytometric bead array analysis (CBA).

CBA

Cytokines produced by sorted and stimulated NKT cell subsets were quantified using the CBA assay (BD Biosciences). Capture and detection antibodies for human IL-2, IL-4, IL-13, IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF, regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were used and detected by flow cytometry. CBA data was analysed using fcap Array software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (Graphpad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis analysis with Dunn's multiple comparisons post-test and Wilcoxon tests.

Results

Human NKT cells from peripheral blood, thymus, spleen and cord blood

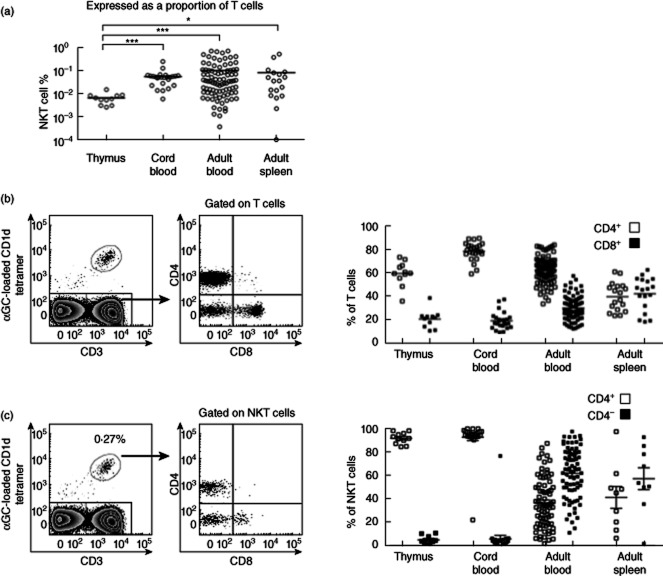

We analysed NKT cells isolated from fresh human thymus, spleen, cord blood and adult peripheral blood. The mean NKT cell frequency of donor tissues were similar for peripheral blood (0·1 (mean) ± 0·02 [standard error of the mean (s.e.m.)], cord blood (0·06 ± 0·01) and spleen (0·08 ± 0·03), but significantly lower in thymus (0·007 ± 0·001). Most (> 90%) thymus and cord blood NKT cells were CD4+, with CD4− NKT cells seen mainly in peripheral blood and spleen (Fig. 1). In contrast to findings in mice that blood NKT cells provide a poor measure of NKT cell frequency in spleen [18], we found that human spleen and blood had similar mean frequencies of NKT cells and of CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets, although this applies to group analysis, rather than to each individual donor.

Figure 1.

Human natural killer T (NKT) cell frequency and CD4+ and CD4− subset distribution. (a) Frequency of total NKT cells expressed as a percentage of CD3+ cells in thymus (n = 11), spleen (n = 18), cord blood (n = 25) and peripheral blood (n = 89) from adults. Representative distribution of T cells (b) and NKT cell subsets (c) defined by expression of CD4 and CD8. Right-hand graphs show collective results. Statistical analysis using Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn's multiple comparisons post-test (b,c).

Differential cell surface antigen expression by CD4+ and CD4− NKT cells

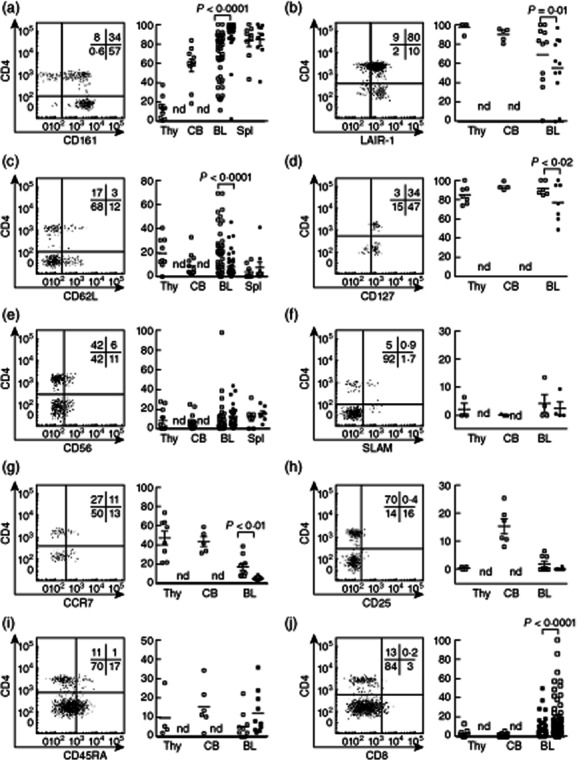

A recent publication identified diversity within CD4+, CD4− and CD8+ NKT cell subsets, but these cells had been expanded prior to analysis. We analysed cell surface antigen expression by CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets without in-vitro expansion and compared blood-derived NKT cells to those from cord blood, thymus and spleen (Fig. 2). Many antigens were expressed differentially by the CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets (Fig. 2a–j), including CD56 and CD161 (confirming these as ineffective surrogate markers for human NKT cells), with CD161 expressed more highly in peripheral blood and spleen than cord blood or thymus. This confirms CD161's status as a marker of NKT cell maturity [19,22,23]. Interestingly, CD161 was expressed by more CD4− than CD4+ NKT cells (Fig. 2a), which supports the hypothesis that comparatively immature precursors of CD4− NKT cells are present within the CD4+ subset [22] [19,23].

Figure 2.

Heterogeneous cell surface antigen expression within CD4+ (white squares) and CD4− (black squares) natural killer T (NKT) cell compartments. (a) CD161 (thymus: n = 10; cord blood: n = 10; adult blood: n = 50); (b) leucocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1 (LAIR-1) (thymus: n = 5; cord blood: n = 5; adult blood: n = 11); (c) CD62L (thymus: n = 9; cord blood: n = 11; adult blood: n = 43); (d) CD127 (thymus: n = 7; cord blood: n = 3; adult blood: n = 5); (e) CD56 (thymus: n = 12; cord blood: n = 14; adult blood: n = 28); (f) signalling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) (thymus; n = 3, cord blood; n = 3, adult blood; n = 4) (g) CCR7, (h) CD25, (i) CD45RA and (j) CD8; n.d. denotes that CD4− NKT cells from thymus and cord blood were not detected or were at frequencies too low for meaningful comparisons with CD4+ NKT cells. Representative plots are lymphocytes from adult blood. Histograms show means ± standard error of the mean in CD4+ (white squares) and CD4− (black squares). n-values are thymus: n = 3–10; cord blood: n = 3–10; adult blood: n = 4–50. Statistical analysis using Wilcoxon test.

Our analysis did not identify any preferential surface antigen expression by either of the CD4+ or CD4 NKT cell subsets. CD8, CD45RA and CD94 were expressed typically by more CD4− NKT cells (Fig. 2i,j and data not shown), whereas CD62L, CD127 and LAIR-1 (Fig. 2c,d,b) were expressed by a higher proportion of CD4+ NKT cells. CD25, CD56, CD16, CD45RO, CD84, CCR7 and signalling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) were expressed differentially by both CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets, but the pattern of expression was similar for each subset (Fig. 2a–j and data not shown). NKT cells from thymus, cord blood, peripheral blood and spleen expressed similar levels of most antigens, although there were exceptions: CD4 was expressed by more NKT cells in thymus and cord blood, CD161 was higher in peripheral blood, CCR7 expression was lowest in peripheral blood and CD25 was highest in cord blood.

NKT cell subset cytokine profiling

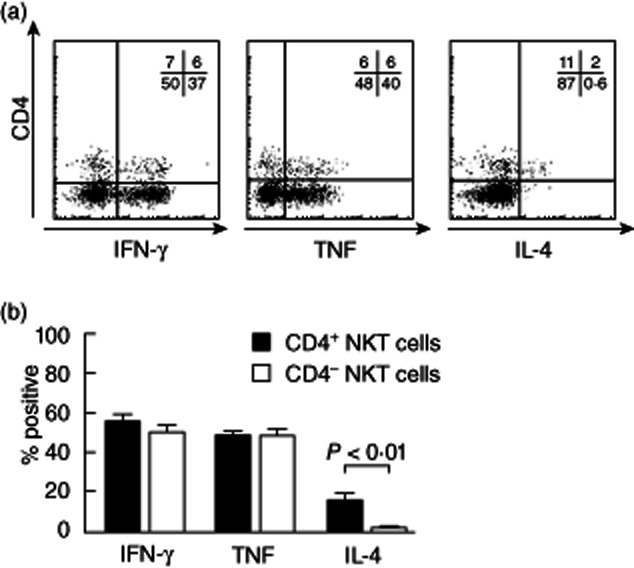

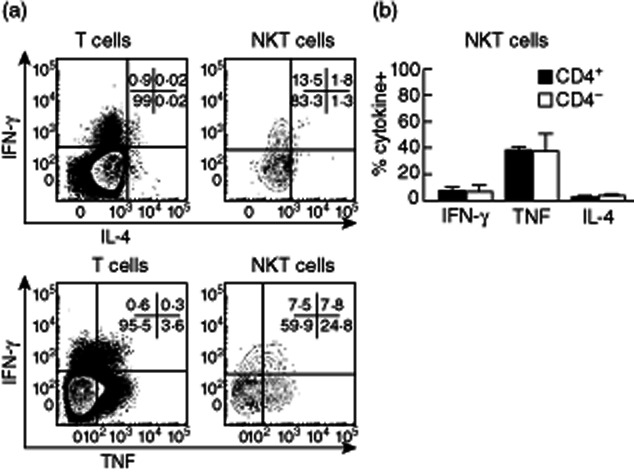

To determine whether the heterogeneity of human NKT cell antigen expression reflected functional differences between subpopulations, we analysed cytokine production by NKT cells from human adult blood after short-term in-vitro stimulation. Intracellular cytokine staining for IFN-γ, TNF and IL-4 confirmed Th0 (IFN-γ+, TNF+ and IL-4+) and Th1 (IFN-γ+, TNF+ and IL-4low) cytokine profiles for CD4+ and CD4− NKT cells, respectively (Fig. 3). More extensive cytokine analysis was conducted using CBA to analyse supernatants from cultures of FACS-sorted NKT cell populations stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 16 h to maximize cytokine output (Fig. 4). A striking finding was that CD4+ NKT cells produced higher cytokine concentrations of IFN-γ, TNF, IL-4, IL-13, GM-CSF and IL-2, despite intracellular flow cytometry analysis showing similar proportions of IFN-γ+ and TNF+ cells in CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell cultures after 4 h stimulation. We did not detect NKT cell production of IL-17 or IL-10 (data not shown). Our data suggest that CD4+ NKT cells exhibit a more prolonged cytokine production than CD4− NKT cells.

Figure 3.

Differential cytokine production by human CD4+ and CD4− natural killer T (NKT) cell subsets derived from peripheral blood. (a) Representative fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) plots show interferon (IFN)-γ, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-4 production by CD4+ and CD4− NKT cells after 4 h phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin stimulation. (b) Histograms show the proportion of NKT cells that secrete IFN-γ (n = 27), TNF (n = 27) and IL-4 (n = 9) after 4 h PMA/ionomycin stimulation. Error bars show standard error of the mean.

Figure 4.

Cytokine yields in CD4+ and CD4− natural killer T (NKT) cell culture supernatants. CD4+ and CD4− (n = 9) subsets were sorted and cultured overnight with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin. Cytometric bead array (CBA) was used to quantify cytokines in culture supernatants. Data are normalized to reflect cultures of 10 000 cells equivalent. Statistical analysis using Wilcoxon test.

Functional significance of CD62L and CD161 expression by CD4+ and CD4− NKT cells

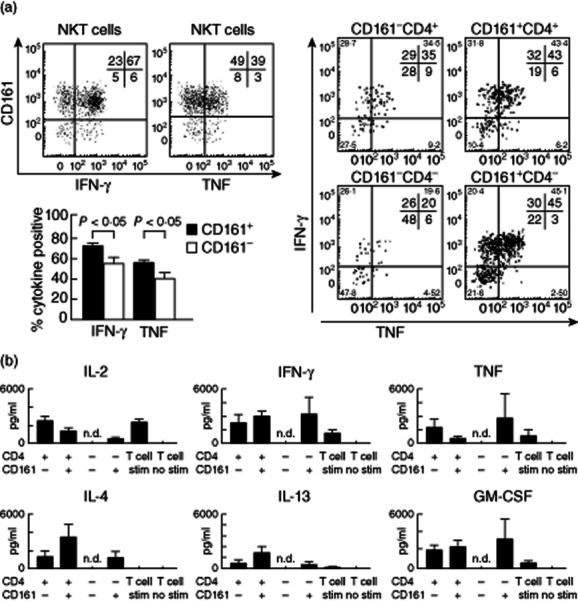

Having identified differential cell surface antigen expression within the CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets, we examined whether this reflected unreported functional heterogeneity. We focused on two antigens (CD161 and CD62L) known to be significant for classifying conventional T cell subsets. Analysis of FACS-sorted subpopulations showed that more CD161+ NKT cells were IFN-γ+ or TNF+ after 4 h stimulation than CD161− cells (Fig. 5a). This was broadly consistent with CBA analysis of supernatants after 16 h of in-vitro stimulation (Fig. 5b). Differences were seen in cytokine production of sorted CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets separated on the basis of CD161; however, these were inconsistent and the trend varied between cytokine types (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

CD161 expression identifies functionally distinct natural killer T (NKT) cells within established subsets. Representative fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) plots show interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) production by CD4+ and CD4− NKT cells from adult human blood after 4 h PMA/ionomycin stimulation. Graphs show the proportion of NKT cells that secrete IFN-γ and/or TNF after 4 h PMA/ionomycin stimulation (n = 18). Cytokine expression by sorted populations of CD4+CD161−, CD4+CD161+, CD4−CD161− and CD4−CD161+ (n = 4) NKT cell subsets are shown in right-hand representative plots. (b) Cytometric bead array (CBA) was used to quantify concentrations of six different cytokines in culture supernatants; n.d. indicates that insufficient numbers of CD4−CD161− cells were sorted to generate meaningful CBA data. Data are normalized to reflect cultures of 10 000 cells equivalent. Statistical analysis using Wilcoxon test.

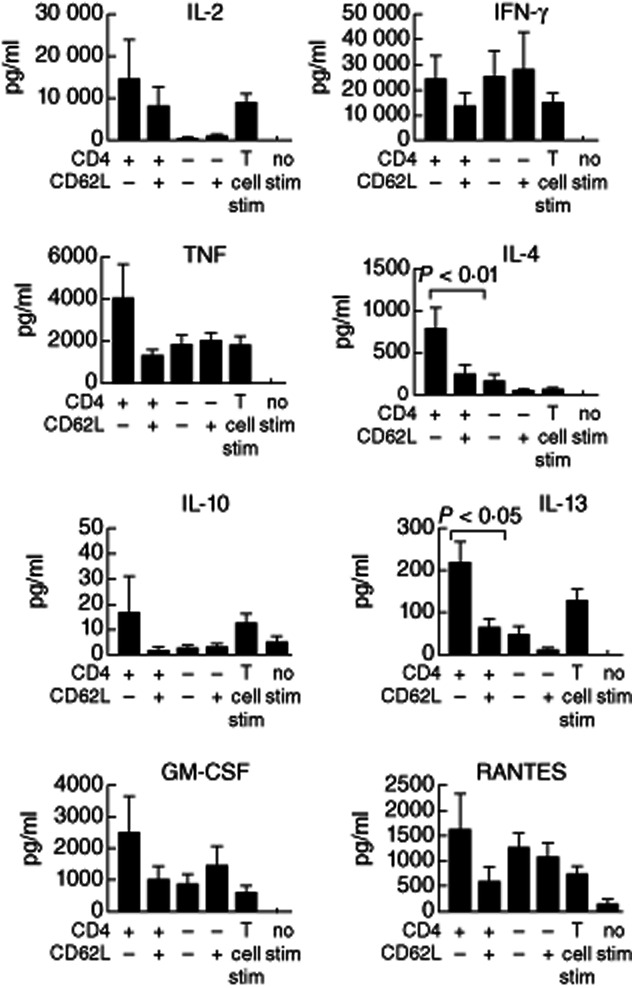

NKT cell subsets defined by CD62L and CD4 expression provided more consistent trends. CD62L expression is lost transiently after stimulation, which prevented intracellular flow cytometry of unsorted NKT cell cultures, but CBA analysis of supernatants from sorted cells revealed striking differences in the cytokine profiles at 16 h (Fig. 6). As expected, cultures of CD4+ NKT cells had the highest cytokine concentrations, but differential CD62L expression correlated well with cytokine production within each subset. For example, CD62L−CD4+ NKT cells were the most potent producers of IL-4 and IL-13 (with a similar trend for many other cytokines (Fig. 6), whereas the lower cytokine production by CD62L+ NKT cells was similar to CD4− NKT cells (CD4−CD62L+ and CD4−CD62L−). IFN-γ was an exception, with a similar concentration of IFN-γ detected in cultures of all four subsets defined by CD62L and CD4 expression.

Figure 6.

CD62L expression identifies functionally distinct blood natural killer T (NKT) cells within established subsets. CD4+CD62L−, CD4+CD62L+, CD4−CD62L− and CD4−CD62L+ (n = 6) NKT cell subsets from adult human blood were sorted and cultured overnight with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin. Cytometric bead array (CBA) was used to quantify cytokines in culture supernatants. Data are normalized to 10 000 cells equivalent.

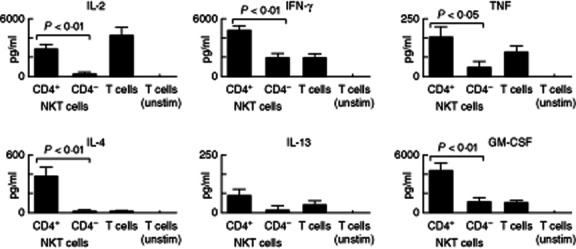

Cytokine analysis of NKT cells from thymus, cord blood and spleen

Most human NKT cell studies have involved cells derived exclusively from peripheral blood. A small number of studies have analysed NKT cells from thymus [19,22,23], liver [20], bone marrow [24] and lung NKT cells [25,26], although these have been mainly in association with diseases such as cancer or asthma. We are unaware of any published study where NKT cells from human spleen have been characterised.

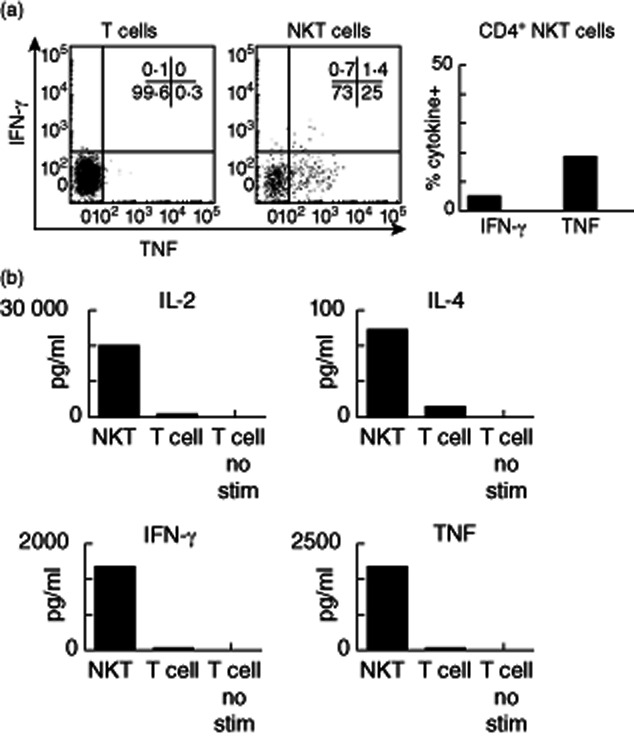

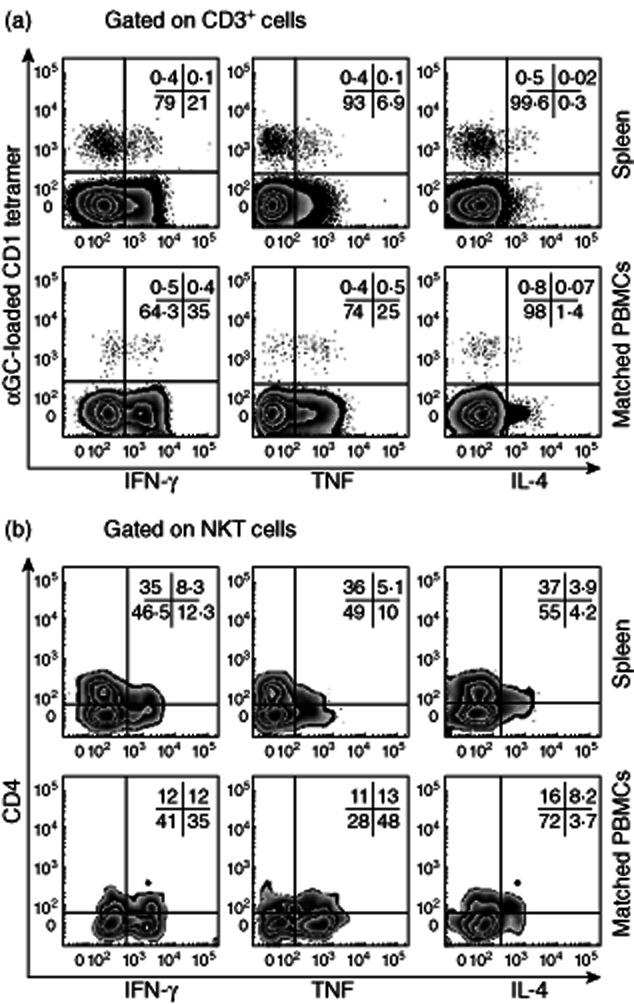

We employed intracellular cytokine staining and CBA analysis to first analyse cytokine production by FACS-sorted thymus NKT cells. Thymus NKT cells (and NKT cells from cord blood) are mainly CD4+ and are reported to be functionally immature cells that do not produce cytokines when stimulated [19]. Curiously, most thymus NKT cells from mice are very strong cytokine producers [27], with mature, functionally competent thymus-resident NKT cells identified alongside developing NKT cells [28]. In contrast to the earlier study, we detected TNF and IFN-γ using intracellular cytokine staining of human thymus NKT cells (Fig. 7a), and IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF were all detected in culture supernatants of thymic NKT cells stimulated for 16 h (Fig. 7b). Human cord blood NKT cells also produced cytokines. These cells had a similar surface antigen expression to NKT cells from thymus (i.e. predominantly CD4+); however, their cytokine profile was more reminiscent of CD4− NKT cells from peripheral blood [IFN-γ, TNF and IL-2, but little IL-4 (IFN-γ and TNF shown)] (Fig. 7b). Cell numbers and tissue availability restricted our analysis of spleen NKT cells, although cytokine profiles were broadly similar to NKT cells from blood (Fig. 9 and data not shown). Analysis of matched blood and spleen NKT cells from a single donor revealed similar cytokine profiles for IFN-γ, TNF and IL-4 (Fig. 9).

Figure 7.

Cytokine expression by thymic natural killer T (NKT) cells. (a) NKT cells from adult thymus were sorted and stimulated overnight with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin. Representative fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) profiles (left and middle) and the proportion of cytokine-positive NKT cells are shown (upper right) (n = 2). (b) Cytometric bead array (CBA) was used to quantify cytokines from sorted thymic NKT cells and T cells in culture supernatants. Data are from two experiments normalized to 10 000 cells equivalent.

Figure 9.

Cytokine production by natural killer T (NKT) cells from spleen. (a) Cytokine expression by donor-matched T and NKT cells from spleen and blood. (b) Cytokine expression by donor-matched CD4+ and CD4− NKT cells from spleen and blood (representative of four spleen samples; one with matched blood sample shown).

Discussion

There is guarded optimism that human NKT cells could become important clinical tools, but an incomplete understanding of the subsets that make up the NKT cell pool has hampered progress and contributed to a lack of consensus about the importance of NKT cells (and NKT cell defects) in different patient groups. We were especially interested to determine the extent of heterogeneity within freshly isolated CD4+ and CD4− NKT cell subsets from a range of human tissues. We found both subsets to be diverse in their expression of antigens and cytokines, consistent with the possibility that each may contain functionally distinct subpopulations. We used NKT cells from blood to confirm that cytokine expression by human NKT cells correlates with the expression of CD4, but we also found correlations with expression of CD62L and CD161, indicating that differential antigen expression may be a useful way to identify new candidate NKT cell subsets. We also demonstrated that analysis of cytokines secreted by NKT cells over an extended time may not correlate with the snapshot view afforded by flow cytometry analysis. This has important implications for analysing how NKT cells contribute to different areas of immunity through release of cytokines, and for predicting the impact of new treatments that seek to stimulate NKT cell subsets selectively.

We analysed cytokine production by NKT cells from tissues other than blood, including thymus, cord blood and spleen. A previous study found that human thymus (and cord blood) NKT cells did not produce cytokines after stimulation unless they had been expanded for up to 3 weeks [19], which differs sharply from results using thymic NKT cells from mice [17]. We confirmed that thymus NKT cells in humans were predominantly CD4+, but found that they were capable of significant cytokine production, including IFN-γ, TNF and IL-4. Strong cytokine staining was also observed using NKT cells from cord blood, illustrating that many CD4+ NKT cells in thymus and cord blood are functionally competent, although the pattern of cytokine expression was distinct from CD4+ NKT cells isolated from peripheral blood (Fig. 8). It also raises the question of whether or not there is a similar resident mature NKT cell population in the human thymus to that identified recently in mice [28]. We also performed the first analysis of NKT cells from human spleen. Fewer surface antigens were analysed for spleen NKT cells, but these appeared to be similarly heterogeneous in expression of cell surface antigens to blood-derived NKT cells, and were similar in their overall frequency and cytokine profile (IFN-γ, TNF and IL-4). This supports the analysis of blood NKT cells as a representative source of systemic NKT cells, at least relative to spleen, although more work is needed to confirm this, including comparative functional analysis of NKT cells from peripheral blood and from other peripheral tissues, such as liver and lymph nodes.

Figure 8.

Cord blood natural killer T (NKT) cells produce cytokines when stimulated. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from cord blood were stimulated for 4 h with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin. (a) Fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) plots show the percentage of T cells and NKT cells that produced interferon (IFN)-γ, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-4. (b) Histograms represent mean percentages of CD4+ and CD4− cord blood NKT cell subsets that make IFN-γ, TNF and IL-4 (n = 6).

Our data clearly support the concept that heterogeneity within the NKT cell pool extends well beyond the CD4+ and CD4− subsets. More investigations are needed to define the functional diversity that exists within the human NKT cell compartment and to correlate this with patterns of antigen expression and tissue residency, but it appears likely that that the diverse activities attributed to human NKT cells relies on an equally diverse array of subsets.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the kind donation of tissue for research purposes by donors and their families. This research was supported by an NHMRC Project Grant (no. 454363) and an NHMRC Program Grant (no. 454569). S.P.B. was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (no. 454731) and by the Australian Government Collaborative Research Network (CRN). S.P.B. is currently supported as a Dorevitch Senior Research Fellow (at FECRI) and as a Robert H. T. Smith Fellow (Uni of Ballarat). D.I.G. is supported by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (no. 1020770).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what's in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. The role of NKT cells in tumor immunity. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;101:277–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balato A, Unutmaz D, Gaspari AA. Natural killer T cells: an unconventional T-cell subset with diverse effector and regulatory functions. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1628–1642. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu L, Van Kaer L. Natural killer T cells and autoimmune disease. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:4–14. doi: 10.2174/156652409787314534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasan S, Tsuji M. A double-edged sword: the role of NKT cells in malaria and HIV infection and immunity. Semin Immunol. 2010;22:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berzins SP, Smyth MJ, Baxter AG. Presumed guilty: natural killer T cell defects and human disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:131–142. doi: 10.1038/nri2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ni.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. J Exp Med. 2002;195:625–636. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PT, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Distinct functional lineages of human V(alpha)24 natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:637–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim CH, Butcher EC, Johnston B. Distinct subsets of human Valpha24-invariant NKT cells: cytokine responses and chemokine receptor expression. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:516–519. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montoya CJ, Pollard D, Martinson J, et al. Characterization of human invariant natural killer T subsets in health and disease using a novel invariant natural killer T cell–clonotypic monoclonal antibody, 6B11. Immunology. 2007;122:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Reilly V, Zeng SG, Bricard G, et al. Distinct and overlapping effector functions of expanded human CD4+, CD8alpha+ and CD4−CD8alpha− invariant natural killer T cells. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e28648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi T, Chiba S, Nieda M, et al. Cutting edge: analysis of human V alpha 24(+)CD8(+) NKT cells activated by alpha-galactosylceramide-pulsed monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:3140–3144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin H, Nieda M, Rozenkov V, Nicol AJ. Analysis of the effect of different NKT cell subpopulations on the activation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, NK cells, and B cells. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowe NY, Coquet JM, Berzins SP, et al. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1279–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berzins SP, Kyparissoudis K, Pellicci DG, et al. Systemic NKT cell deficiency in NOD mice is not detected in peripheral blood: implications for human studies. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:247–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2004.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baev DV, Peng XH, Song L, et al. Distinct homeostatic requirements of CD4+ and CD4− subsets of V{alpha}24-invariant natural killer T cells in humans. Blood. 2004;104:4150–4156. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenna T, Golden-Mason L, Porcelli SA, et al. NKT cells from normal and tumor-bearing human livers are phenotypically and functionally distinct from murine NKT cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1775–1779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berzins SP, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Working with NKT cells – pitfalls and practicalities. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandberg JK, Stoddart CA, Brilot F, Jordan KA, Nixon DF. Development of innate CD4+ alpha-chain variable gene segment 24 (Valpha24) natural killer T cells in the early human fetal thymus is regulated by IL-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7058–7063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305986101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berzins SP, Cochrane AD, Pellicci DG, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Limited correlation between human thymus and blood NKT cell content revealed by an ontogeny study of paired tissue samples. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1399–1407. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan AC, Neeson P, Leeansyah E, et al. Testing the NKT cell hypothesis in lenalidomide-treated myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Leukemia. 2010;24:592–600. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matangkasombut P, Marigowda G, Ervine A, et al. Natural killer T cells in the lungs of patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1181–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas SY, Chyung YH, Luster AD. Natural killer T cells are not the predominant T cell in asthma and likely modulate, not cause, asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:980–984. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammond KJ, Pelikan SB, Crowe NY, et al. NKT cells are phenotypically and functionally diverse. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3768–3781. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3768::AID-IMMU3768>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berzins SP, McNab FW, Jones CM, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Long-term retention of mature NK1.1+ NKT cells in the thymus. J Immunol. 2006;176:4059–4065. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]