Abstract

Objective

To investigate genetic etiologies of preterm birth (PTB) in Argentina through evaluation of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in candidate genes and population genetic admixture.

Study Design

Genotyping was performed in 389 families. Maternal, paternal, and fetal effects were studied separately. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was sequenced in 50 males and 50 females. Y-chromosome anthropological markers were evaluated in 50 males.

Results

Fetal association with PTB was found in the progesterone receptor (PGR, rs1942836; p= 0.004). Maternal association with PTB was found in small conductance calcium activated potassium channel isoform 3 (KCNN3, rs883319; p= 0.01). Gestational age associated with PTB in PGR rs1942836 at 32 –36 weeks (p= 0.0004). MtDNA sequencing determined 88 individuals had Amerindian consistent haplogroups. Two individuals had Amerindian Y-chromosome consistent haplotypes.

Conclusions

This study replicates single locus fetal associations with PTB in PGR, maternal association in KCNN3, and demonstrates possible effects for divergent racial admixture on PTB.

Keywords: Prematurity, genetic admixture

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) complicates nearly 13 million pregnancies worldwide each year1. Rates of PTB are currently increasing in many countries including Argentina2. Health care costs for infants born premature are substantial3 and the risk of lifelong disabilities for survivors, including chronic lung disease, cognitive impairment, and cerebral palsy, are considerable4. While most PTB occurs spontaneously5, the greatest single risk factor for delivering an infant prematurely is a history of a prior PTB6.

A genetic contribution to PTB is widely accepted7. Twin studies and familial recurrences provide evidence that up to 40% of PTB risk is heritable8, 9. Racial differences in PTB rates are significant10 and may indicate unique genetic susceptibilities in certain populations11. Both maternal and paternal race have been shown independently to influence PTB12, 13, 14. Admixture studies in Latin America have shown tremendous geographic variability in Amerindian and European contributions to ancestry15 and in Argentina have shown extensive paternal directional mating between historic populations of European fathers and Amerindian mothers16, 17.

The complex interplay between genetics, population admixture, and the environment makes PTB a challenging condition to study. Candidate gene studies associating single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) with PTB have been difficult to replicate18. We created a biorepository of infants born prematurely in Argentina, including samples from their parents and extended families. We hypothesized that gene studies of our population with its unique admixture would complement previous studies of PTB and allow the discovery of distinct novel gene variation.

Methods

Collection of samples began in November 2005. Two public maternity centers in Argentina, the Instituto de Maternidad y Ginecología Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes in Tucumán and Hospital Provincial de Rosario in Rosario participated in sample collection. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and approved by both a local institutional review board and the University of Iowa (IRB200411759). Cases were identified when a singleton was delivered before 37 weeks of completed gestation. Gestational age (GA) was estimated by last menstrual period, ultrasound, or physical examination at the time of birth.

We attempted to collect samples from three generations including the preterm infant, the infant's parents, and maternal grandparents. This study design allowed separate investigation of transmission of genetic risk to a mother (maternal contribution to PTB) and the affected infant (fetal contribution to PTB). Maternal sisters with a history of PTB and premature siblings were included for study if available. Samples consisting of placental blood, cord blood, whole blood, or saliva were obtained during hospitalization. Extraction of DNA from biosamples was completed at either the Centro de Educación Médica e Inverstigaciones Clínicas in Buenos Aires or the University of Iowa.

Sample Genotyping

SNP genotyping was performed with TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described19. Sequence Detection Systems 2.2 software (Applied Biosystems) was utilized for allele determination. Genotypes were entered into a Progeny database (Progeny Software, LLC, South Bend, IN). The overall approach mirrored previously reported studies19, 20. Candidate genes were selected through literature review of biological pathways implicated in PTB. Attempts were made to replicate significant results from the study of a separate population of infants born prematurely at the University of Iowa. The genes/SNPs studied are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Candidate Genes

| Gene | Chromosome | SNP marker(s) |

|---|---|---|

| LRP8 | 1p32.3 | rs3737983 |

| PCSK9 | 1p32.3 | rs11591147 |

| KCNN3 | 1q21.3 | rs883319 |

| CFHR1 | 1q31.1 | rs800292 |

| EPHX1 | 1q42.12 | rs1009668 |

| APOB | 2p24.1 | rs7575840 |

| AGTR1 | 3q24 | rs275649 |

| HPGD | 4q34.1 | rs8752 |

| HMGCR | 5q13.3 | rs3931914, rs2303152, rs12654264 |

| IL5 | 5q31.1 | rs743562 |

| NR3C1 | 5q31.3 | rs4128753 |

| ADRB2 | 5q33.1 | rs1042718 |

| C2 | 6p21 | rs7746553 |

| IGFBP3 | 7p13 | rs3793345 |

| DEFA6 | 8p23.1 | rs4458901 |

| NAT2 | 8p22 | rs1799930 |

| ABCA1 | 9q31.1 | rs2066716, rs4149313, rs2230806, rs3890182 |

| PTGES | 9q34.11 | rs3844048 |

| TRAF2 | 9q34.3 | rs2811761, rs10781522, rs3750512, rs4880166 |

| MBL2 | 10q21.1 | rs5030737, rs7096206 |

| DHCR7 | 11q13.4 | rs3763856, rs1630498, rs2002064 |

| SERPINH1 | 11q13.5 | rs667531, rs681390 |

| PGR | 11q22.1 | rs1042839, rs653752, rs1942836, rs1893505 |

| MMP1 | 11q22.2 | rs470215, rs7125062, rs996999 |

| MMP3 | 11q22.2 | rs650108, rs679620 |

| ALDH2 | 12q24.12 | rs2238151 |

| PTGER2 | 14q22.1 | rs17197 |

| LIPC | 15q22.1 | rs1800588, rs1968685, rs1973028, rs6083 |

| CYP11A1 | 15q24.1 | rs2073475 |

| CRHR1 | 17q21.31 | rs110402 |

| ACE | 17q23.3 | rs4351 |

| SMARCA4 | 19p13.2 | rs1529729 |

| APOE | 19q13.32 | rs405509, rs429358, rs7412 |

| APOC2 | 19q13.32 | 2288911 |

| BP1 | 20q11.23 | rs1341023 |

| MMP9 | 20q13.12 | rs17576, rs3918256 |

| PTGIS | 20q13.13 | rs6095545, rs6090996, rs493694 |

Abbreviation: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Admixture Analysis

To estimate genetic admixture in our study population, we evaluated anthropologically variable regions of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and the Y-chromosome. 100 individuals from the Tucumán study site (50 males and 50 females) were selected for MtDNA sequencing and Y-chromosome sequencing. Sequencing of purified DNA was performed by Functional Biosciences (Madison, WI, USA). Chromatograms were loaded to a UNIX workstation and displayed with the CONSED program (v. 4.0), as previously described19.

MtDNA was sequenced in hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) and hypervariable region 2 (HVR2). HVR1 was analyzed from 16049 – 16503 bp; HVR2 from 066 – 420 bp. Polymorphisms in mtDNA sequence were compared to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence21, publicly available mtDNA sequence22, and to previously published works16, 23 in order to assign haplogroups.

Y-chromosome sequencing was performed for DYS19 and DYS199. DYS19 is a Y-chromosome short tandem repeat which owes it diversity to a variable number of GATA repeats24. Sequencing of DYS19 was preformed utilizing primers as described by Hammer and Horai25. DYS199 is a Y-chromosome polymorphism with greater than 90% prevalence of the `T' allele in Amerindian populations26. Sequencing of DYS199 was performed utilizing primers as described by Underhill et al.26.

Statistical Analysis

SNP genotype data was analyzed for non-mendelian inheritance utilizing PedCheck27. Fetal and maternal associations with PTB were determined using the Family Based Association Test (FBAT)28, 29 and PLINK software (version 1.07)30. When multiple SNPs were tested in a gene, haplotype analysis was performed using FBAT. Maternal and paternal allelic transmissions were separately analyzed using PLINK to investigate parental differences in transmission. GA and birth weight (BW) were evaluated as continuous variables for SNP associations. GA was also evaluated in 4-week windows to determine allelic frequency at specific intervals of gestation. Given that analysis was completed for four independent tests (fetal affected status, maternal affected status, GA, BW), formal Bonferroni correction for multiple testing in this study at an α level of 0.05 was p< 0.0002.

Results

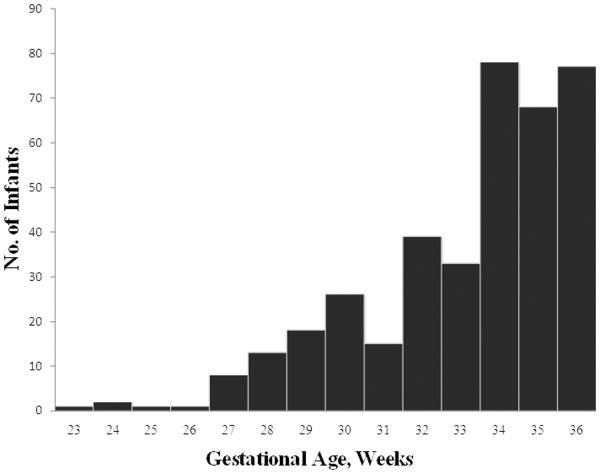

A total of 387 families were studied. 294 prematurely born probands were available for genotyping. Sampling of three generations, including the proband infant, parents, and maternal grandparents, was complete for 96 families. An additional 103 infants had both parents available for study. Mean GA of case infants was 33.2 ± 2.6 weeks. Mean BW was 1886 grams ± 542 grams. GA distribution of study infants is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Frequency Distribution of Study Infants by Gestational Age

Population Admixture

Analysis of mtDNA sequence HVR1 and HVR2 classified 88 individuals into Amerindian haplogroups A2 (n= 13), B1 (n= 9), C1 (n= 37), or D1 (n= 29). Two individuals had evidence of African ancestry, L1b and L2a. Other haplogroups represented included X and I, with one individual each. Eight individuals were not strictly classifiable due to either lack of informative polymorphisms or poor sequence quality. Mitochondrial sequence data can be viewed at GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) with accession numbers HM592299 though HM592389 (HVR1) and HM592390 through HM592487 (HVR2).

Y-chromosome sequencing of DYS19 was successful in 44 individuals. Six individuals genotyped with the most common Amerindian GATA repeat number, 13 GATA repeats. Twenty-five individuals had the most common European variant of 14 repeats. Seven individuals had 15 repeats, three had 16 repeats, and three had 17 repeats. DYS19 sequence data can be viewed at GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) with accession numbers HM592488 through HM592531. Of the six individuals with 13 DYS19 GATA repeats, only two also had the T allele of the Amerindian marker DYS199. No other individuals in our study cohort had the T allele.

Fetal Effects

Genetic predisposition for PTB in the fetus was associated (p< 0.05) with multiple genes in our study as shown in Table 2. The T allele of rs1942836 in PGR showed the strongest fetal association with PTB (p= 0.004).

Table 2.

Fetal Significant Effects

| Gene | SNP | Allele (frequency) | Informative Families | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| DEFA6 | rs4458901 | C (77%) | 71 | p= 0.02 |

| NAT2 | rs1799930 | G (86%) | 49 | p= 0.04 |

| TRAF2 | rs3750512 | T (55%) | 101 | p= 0.03 |

| TRAF2 | rs4880166 | G (64%) | 97 | p= 0.04 |

| PGR | rs1942836 | T (66%) | 96 | p= 0.004 |

| APOC2 | rs2288911 | C (76%) | 67 | p= 0.04 |

| MMP2 | rs17576 | A (79%) | 94 | p= 0.02 |

DEFA6: defensin alpha 6; NAT2: N-acetyltransferase 2; TRAF2: TNF receptor-associated factor 2; PGR: progesterone receptor; APOC2: apolipoprotein C2; MMP2: matrix metallopeptidase 2

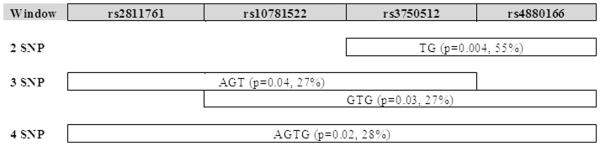

In haplotype analysis, TRAF2 showed multiple positive fetal associations with PTB as shown in Figure 2. Notably, the combination of a T allele at rs3750512 and a G allele at rs4880166 in TRAF2 was observed in 55% of our population (p= 0.004).

Figure 2.

TRAF2 Haplotype Blocks

Maternal Effects

Maternal associations (p< 0.05) with PTB are shown in Table 3. The T allele of rs883319 in KCNN3 showed the strongest maternal association with PTB (p= 0.01).

Table 3.

Maternal Significant Effects

| Gene | SNP | Allele frequency) | Informative families | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| KCNN3 | rs883319 | T (18%) | 51 | p= 0.01 |

| HMGCR | rs2303152 | C (57%) | 15 | p= 0.05 |

| SERPINH1 | rs667531 | G (60%) | 56 | p= 0.04 |

| PTGER2 | rs17197 | T (73%) | 50 | p= 0.04 |

| LIPC | rs1973028 | G (53%) | 53 | p= 0.03 |

KCNN3: potassium intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily N, member 3; HMGCR: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; SERPINH1: serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade H, member 1; PTGER2: prostaglandin E2 receptor; LIPC: hepatic lipase

Parental Specific Transmission and PTB

Parental specific allele transmission effects on PTB are shown in Table 4. Although, none of the SNP transmissions achieved statistical significance, a trend towards significance was shown in DEFA6, PGR, and PTGIS.

Table 4.

Parent-of-origin specific effects for PTB infants

| Gene | SNP | Allele | Paternal transmission | Paternal ORa | Maternal transmission | Maternal ORa | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEFA6 | rs4458901 | C | P=0.005 | 2.5 | P=0.65 | 1.15 | 0.09 |

| PGR | rs1042839 | C | P=0.47 | 1.3 | P=0.10 | 1.9 | 0.10 |

| PTGIS | rs493694 | G | P=0.18 | 1.8 | P=0.03 | 0.90 | 0.07 |

Abbreviations: PTB, preterm birth; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

OR is odds ratio of having the associated allele versus the other allele.

Null hypothesis: paternal odds ratio=maternal odds ratio.

Birth Weight/Gestational Age Effects

The T allele of PGR rs1942836 was associated with higher BW in infants born prematurely when studied as a continuous variable (p= 0.007). The T allele of PGR rs1942836 remained significant when evaluating the association of higher GA (studied as continuous outcome) and genotype (p= 0.03). The A allele of HPGD rs8752 was also associated with higher GA as a continuous outcome (p= 0.03).

In evaluation of GA effects on PTB utilizing 4 week windows, the PGR rs1942836 T allele had association with PTB at GA 33 to 36 weeks (p= 0.0004). In addition, the T allele was associated with longer gestation and higher BW when the effects of GA and BW on PTB were evaluated as continuous variables. Both TRAF2 rs4880166 and rs2811761 had associations with PTB at GA 29 to 32 weeks (p= 0.002 for both SNPs). A 4 week window haplotype analysis of APOE showed association between the rs405509 A allele, rs429358 T allele, and PTB at 32 to 35 weeks (p= 0.003). Additionally, a 4 week window haplotype analysis of PTGIS showed association between the rs6095545 G allele, rs493694 G allele, and PTB at 33 to 36 weeks (p= 0.001).

Discussion

Global reduction in PTB rates could have a substantial impact on worldwide infant morbidity and mortality. Discovering genetic susceptibilities to PTB could allow for novel treatments and interventions that might lessen the impact PTB has on families and society. In this study, we attempted to replicate previous candidate gene investigations that found associations with PTB and to uncover associations unique to our Argentine cohort.

When evaluating fetal associations with PTB, we were able to replicate significance in a SNP previously studied in the PGR gene. This SNP, rs1942836, is located in a possible regulatory region of PGR. Fetal association with PTB in rs1942836 was first reported by Ehn et al. with p= 0.002 (23). SNP rs1942836 had a similar association in our population with p= 0.004. We speculate that this region of PGR may have a role in altering expression of progesterone receptor isoforms. Progesterone has an important role in pregnancy maintenance particularly in later gestation31, 32. Supplementation of progesterone in high-risk pregnancies has been effective in reducing the incidence of repeat PTB33. Progesterone has also been shown to protect fetal membranes from TNF-induced apoptosis34. Progesterone receptors are found in many pregnancy associated tissues including fetal amniotic and chorionic membranes35, 36. Our finding that polymorphisms in rs1942836 are associated with PTB in the latter GA window of 32 to 36 weeks (p= 0.0004) is consistent with the important role of progesterone in maintaining uterine quiescence late in pregnancy.

Fetal association with PTB was also found in haplotype analysis of TRAF2. The haplotype block containing rs3750512 (T allele) and rs4880166 (G allele) in TRAF2 had association with PTB at p= 0.004. Evaluating polymorphisms in TRAF2 for gestational age effects revealed that rs4880166 was most strongly associated with PTB at GA 29 to 32 weeks (p= 0.002). TRAF2, which encodes TNF receptor-associated factor 2, is involved in signal transduction in the TNF cascade and is an activator of the transcription factor NF-kappa B37, 38. NF-kappa B works in conjunction with TRAF1, TRAF2, to suppress caspase-8 induced apoptosis of cell membranes39. Elevations in amniotic fluids levels of TNF have been demonstrated in both preterm labor and premature rupture of membrane40, 41. Previous studies have also linked genetic polymorphisms of TNF and TNF Fas-mediated pathways to premature membrane rupture42, 43. Our findings suggest that alterations of TNF pathway proteins may lead to PTB.

The strongest maternal association with PTB was seen in KCNN3 rs883319 with p= 0.01. KCNN3 (also known as SK3) channels are expressed in tissues responsible for maintaining gestation and inducing parturition including the uterine myometrium44 and are subject to regulation by estrogen45. Overexpression of KCNN3 has been linked to compromised parturition through reduced uterine contractility in mouse models46, and overexpression of this channel precludes the ability of mice to give birth prematurely47. We recently reported both association and sequence data suggesting a role for both rare and common variants in KCNN3 in European populations further supporting the observations made in this South American population48. KCNN3 rs883319 was specifically associated with early PTB in that study.

Prior investigations of genetic admixture in Argentina have revealed evidence of selective mating between European males and Amerindian females16, 17. As a result, Amerindian mtDNA haplogroups are found throughout Argentina in sizeable proportions but Amerindian Y-chromosome inheritance is more limited17. The sequencing of males and females in our study population for mtDNA haplogroup and Y-chromosome haplotype markers estimates that our population has similar historical divergent admixture with evidence of Amerindian ancestry in mtDNA but lacking in the Y-chromosome.

The contribution of genetic admixture to PTB is not known but significant racial differences exist in PTB. The risk ratio of PTB for an Amerindian in the US is 1.32 compared to Caucasians49. Studies of PTB in populations relatively lacking in admixture have shown that maternal genetics may play a more substantial role in PTB than fetal (and thereby paternal) contributions50, 51 . The high prevalence of Amerindian mtDNA haplogroups in our study cohort may therefore place this population at increased risk for PTB.

Hypothesis generating candidate gene studies of association for complex diseases such as PTB have intrinsic limitations and are often difficult to replicate. A potential confounder of this study is the underlying heterogeneity of causes of PTB. Attempts were not made to stratify this population by indication for PTB. Uniformity in gestational age estimation was also limited in this study because of greatly variable levels of prenatal care in this population.

Findings in this study did not reach formal statistical significance when correcting for multiple comparisons. However, Bonferroni correction may be overly conservative when applied to studies such as PTB where intricate interactions between multiple genetic and environmental risk factors are likely contributory to disease burden52.

In summary, this study has replicated a polymorphism in PGR with a fetal association and in KCNN3 with a maternal association with PTB in a novel population. PGR and TRAF2 have shown association with PTB during specific time periods in gestation in this population. Asymmetric racial ancestry exists in mtDNA and Y-chromosome markers in our cohort, highlighting potential consequences for divergent admixture and role for further investigation of parental specific effects on PTB.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express our gratitude to the Argentine families who participated in this study and the extraordinary efforts by the coordinating medical staff in Tucuman. Financial support for this investigation was provided through the March of Dimes (grants 1-FY05-126 and 6-FY08-260) and the NIH (grants R01 HD-52953 and HD-57192). Dr. Mann's fellowship has been supported by a NIH T-32 training grant (5T32 HL07638-23).

Footnotes

Statement of financial support: Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants NIH 1R01 HD-52953 and NIH 1U01 HG-004423; and from the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, grants #6-FY08-260 and #21-FY10-180.

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, Pilar Bertran A, Meraldi M, Harris Requejo J, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:31–38. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramer MS, Barros FC, Demissie K, Liu S, Kiely J, Joseph KS. Does reducing infant mortality depend on preventing low birthweight? An analysis of temporal trends in the Americas. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:445–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell RB, Green NS, Steiner CA, Meikle S, Howse JL, Poschman K, et al. Cost of Hospitalization for Preterm and Low Birth Weight Infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1–e9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dammann O, Leviton A, Gappa M, Dammann CE. Lung and brain damage in preterm newborns, and their association with gestational age, prematurity subgroup, infection/inflammation and long term outcome. BJOG. 2005;112(Suppl 1):4–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Das A, Moawad AH, Iams JD, Meis PJ, et al. The preterm prediction study: a clinical risk assessment system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1885–1893. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70225-9. discussion 1893–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeFranco E, Teramo K, Muglia L. Genetic Influences on Preterm Birth. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 2007;25:040–051. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muglia LJ, Katz M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:529–535. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treloar SA, Macones GA, Mitchell LE, Martin NG. Genetic influences on premature parturition in an Australian twin sample. Twin Res. 2000;3:80–82. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clausson B, Lichtenstein P, Cnattingius S. Genetic influence on birthweight and gestational length determined by studies in offspring of twins. BJOG. 2000;107:375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;202:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anum EA, Springel EH, Shriver MD, Strauss JF. Genetic Contributions to Disparities in Preterm Birth. Pediatric Research. 2009;65:1–9. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31818912e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palomar L, DeFranco EA, Lee KA, Allsworth JE, Muglia LJ. Paternal race is a risk factor for preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197:152.e151–152.e157. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simhan HN, Krohn MA. Paternal race and preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;198:644.e641–644.e646. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kistka Z, Palomar L, Lee K, Boslaugh S, Wangler M, Cole F, et al. Racial disparity in the frequency of recurrence of preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;196:131.e131–131.e136. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, Ray N, Rojas W, Parra MV, Bedoya G, Gallo C, et al. Geographic Patterns of Genome Admixture in Latin American Mestizos. PLoS Genetics. 2008;4:e1000037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salas A, Jaime JC, Álvarez-Iglesias V, Carracedo Á . Gender bias in the multiethnic genetic composition of central Argentina. Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;53:662–674. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dipierri JE, Alfaro E, Martinez-Marignac VL, Bailliet G, Bravi CM, Cejas S, et al. Paternal directional mating in two Amerindian subpopulations located at different altitudes in northwestern Argentina. Hum Biol. 1998;70:1001–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolan SM, Hollegaard MV, Merialdi M, Betran AP, Allen T, Abelow C, et al. Synopsis of preterm birth genetic association studies: the preterm birth genetics knowledge base (PTBGene) Public Health Genomics. 2010;13:514–523. doi: 10.1159/000294202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehn NL, Cooper ME, Orr K, Shi MIN, Johnson MK, Caprau D, et al. Evaluation of Fetal and Maternal Genetic Variation in the Progesterone Receptor Gene for Contributions to Preterm Birth. Pediatric Research. 2007;62:630–635. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181567bfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steffen KM, Cooper ME, Shi M, Caprau D, Simhan HN, Dagle JM, et al. Maternal and fetal variation in genes of cholesterol metabolism is associated with preterm delivery. Journal of Perinatology. 2007;27:672–680. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews RM, Kubacka I, Chinnery PF, Lightowlers RN, Turnbull DM, Howell N. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat Genet. 1999;23:147. doi: 10.1038/13779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [cited]Available from:

- 23.Bandelt HJ, Herrnstadt C, Yao YG, Kong QP, Kivisild T, Rengo C, et al. Identification of Native American founder mtDNAs through the analysis of complete mtDNA sequences: some caveats. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:512–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roewer L, Arnemann J, Spurr NK, Grzeschik KH, Epplen JT. Simple repeat sequences on the human Y chromosome are equally polymorphic as their autosomal counterparts. Hum Genet. 1992;89:389–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00194309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammer MF, Horai S. Y chromosomal DNA variation and the peopling of Japan. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:951–962. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Underhill PA, Jin L, Zemans R, Oefner PJ, Cavalli-Sforza LL. A pre-Columbian Y chromosome-specific transition and its implications for human evolutionary history. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:196–200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X. Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet Epidemiol. 2000;19(Suppl 1):S36–42. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabinowitz D, Laird N. A unified approach to adjusting association tests for population admixture with arbitrary pedigree structure and arbitrary missing marker information. Hum Hered. 2000;50:211–223. doi: 10.1159/000022918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:514–550. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sfakianaki AK, Norwitz ER. Mechanisms of progesterone action in inhibiting prematurity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:763–772. doi: 10.1080/14767050600949829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, Dombrowski MP, Sibai B, Moawad AH, et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379–2385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo G, Abrahams VM, Tadesse S, Funai EF, Hodgson EJ, Gao J, et al. Progesterone inhibits basal and TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in fetal membranes: a novel mechanism to explain progesterone-mediated prevention of preterm birth. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:532–539. doi: 10.1177/1933719110363618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merlino A, Welsh T, Erdonmez T, Madsen G, Zakar T, Smith R, et al. Nuclear progesterone receptor expression in the human fetal membranes and decidua at term before and after labor. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:357–363. doi: 10.1177/1933719108328616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh SY, Kim CJ, Park I, Romero R, Sohn YK, Moon KC, et al. Progesterone receptor isoform (A/B) ratio of human fetal membranes increases during term parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1156–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang E, Marcotte R, Petroulakis E. Signaling pathway for apoptosis: a racetrack for life or death. J Cell Biochem. 1999;(Suppl 32–33):95–102. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(1999)75:32+<95::aid-jcb12>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr. NF-kappaB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobsson B, Mattsby-Baltzer I, Andersch B, Bokstrom H, Holst RM, Nikolaitchouk N, et al. Microbial invasion and cytokine response in amniotic fluid in a Swedish population of women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:423–431. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shobokshi A, Shaarawy M. Maternal serum and amniotic fluid cytokines in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes with and without intrauterine infection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;79:209–215. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalish RB, Vardhana S, Gupta M, Perni SC, Chasen ST, Witkin SS. Polymorphisms in the tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene at position −308 and the inducible 70 kd heat shock protein gene at position +1267 in multifetal pregnancies and preterm premature rupture of fetal membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1368–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts AK, Monzon-Bordonaba F, Van Deerlin PG, Holder J, Macones GA, Morgan MA, et al. Association of polymorphism within the promoter of the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene with increased risk of preterm premature rupture of the fetal membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1297–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70632-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen MX, Gorman SA, Benson B, Singh K, Hieble JP, Michel MC, et al. Small and intermediate conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels confer distinctive patterns of distribution in human tissues and differential cellular localisation in the colon and corpus cavernosum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369:602–615. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierce SL, England SK. SK3 channel expression during pregnancy is regulated through estrogen and Sp factor-mediated transcriptional control of the KCNN3 gene. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E640–646. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00063.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bond CT, Sprengel R, Bissonnette JM, Kaufmann WA, Pribnow D, Neelands T, et al. Respiration and parturition affected by conditional overexpression of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel subunit, SK3. Science. 2000;289:1942–1946. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierce SL, Kresowik JD, Lamping KG, England SK. Overexpression of SK3 channels dampens uterine contractility to prevent preterm labor in mice. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:1058–1063. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Day LJ, Schaa KL, Ryckman KK, Cooper M, Dagle JM, Fong CT, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the KCNN3 gene associate with preterm birth. Reprod Sci. 2011 Mar;18(3):286–295. doi: 10.1177/1933719110391277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexander GR, Wingate MS, Boulet S. Pregnancy outcomes of American Indians: contrasts among regions and with other ethnic groups. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Svensson AC, Sandin S, Cnattingius S, Reilly M, Pawitan Y, Hultman CM, et al. Maternal effects for preterm birth: a genetic epidemiologic study of 630,000 families. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:1365–1372. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyd HA, Poulsen G, Wohlfahrt J, Murray JC, Feenstra B, Melbye M. Maternal contributions to preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:1358–1364. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rice TK, Schork NJ, Rao DC. Methods for handling multiple testing. Adv Genet. 2008;60:293–308. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(07)00412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]