Abstract

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) between p53 and its negative regulator MDM2 comprises one of the most important and intensely studied PPI’s involved in preventing the initiation of cancer. The interaction between p53 and MDM2 is conformation-based and is tightly regulated on multiple levels. Due to the Angstrom level structural insight there is a reasonable understanding of the structural requirements needed for a molecule to bind to MDM2 and successfully inhibit the p53/MDM2 interaction. The current review summarizes the binding characteristics of the different disclosed small molecules for inhibition of MDM2 with a co-crystal structure. Synthetic access to these compounds as well as their derivatives are described in detail.

Keywords: p53, MDM2, HDM2, protein protein interactions, small molecule inhibitors

1. INTRO: BIOLOGY OF P53 MDM2

P53, a nuclear transcription factor and its negative regulator MDM2 consists of the most intensely studied protein-protein interactions (PPI) with a group of small molecular weight antagonists described and many more disclosed in patent literature. Around 22 million people are currently living with a tumor affected by p53 and while p53 mutations are very common in human tumors it remains wildtype in approximately 50% of cancer patients. Glioblastoma multiformis, one of the most common and aggressive primary brain tumors in humans has been well established as a tumor with cells highly overexpressing the negative regulators of p53, MDM2 and/or MDMX, causing a severe decrease in p53 expression [1–7].

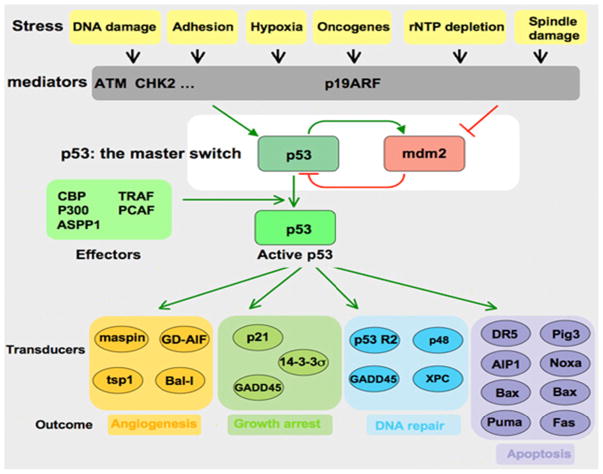

p53 suppresses the formation of tumors and plays an essential role in guarding cells in response to various stresses, such as DNA damage, or hypoxia, by inducing cell cycle arrest, repair, or apoptosis (Fig. 1). It is specifically involved in the effects of survival of proteins in the mitochondria, regulating DNA repair, microRNA processing, and protein translation as well as many other processes in the body. If p53 functionality is impaired it can no longer prevent damaged cells from multiplying and passing mutated genes to the next generation and allows these processes to go unregulated. In fact a study done with p53 deficient mice showed that they were able to develop normally; however were prone to spontaneous tumor generation. Therefore cells that lack p53 have the potential to pass mutations on to the next generation which can facilitate tumor growth [8, 9].

Fig. 1.

Regulation of p53 by MDM2 showing the stress signals that activate the pathway, mediators that detect the signals, and downstream transcriptional activators affected by the pathway and their outcomes (Figure courtesy of Thierry Soussi, PhD http://p53.free.fr/p53_info/p53_Pathways.html)

The concentration and activity of p53 protein in a cells are low and subjected to tight control both during stress and under normal physiological conditions. MDM2 mediated degradation regulates unstressed cell, via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (regulation of p53 stability), and by inactivation of the p53 transcriptional activity. In addition p53 activity is modified by MDM2 and MDMX by transporting p53 into cytoplasm, away from nuclear DNA making the activity of p53 as a transcription factor out of reach. Once a cell undergoes stress MDM2 degrades itself, leading to the accumulation and activation of p53. Increased nuclear levels of p53 activate MDM2/X gene transcription, leading to elevated levels of MDM2 and MDMX. As activated p53 transactivates MDM2, the increasingly abundant MDM2 degrades MDMX more efficiently, enabling full p53 activation; the transcriptional stress response is at.,its peak. MDM2 is a special example of a protein that regulates p53 through an auto-regulatory feedback loop, in which p53 also regulates MDM2. Following stress relief, the accumulated MDM2 preferentially targets p53 again; p53 levels decrease, and MDMX levels increase, p53 activity also decreases. Small amounts of p53 will reduce the amount of MDM2 protein and this will result in an increase of p53 activity, thus completing the loop. The switch that makes MDM2 preferentially target p53 for degradation in unstressed cells, then target itself and MDMX after stress relief, is not precisely understood [2, 10–15].

Other than MDM2, MDMX also plays an important role in regulation of p53 however it is much less characterized (MDMX is also known as MDM4, and human versions as HDMX, and HDM4). MDMX is structurally homologous to MDM2 with a high degree of sequence homology and structural similarity. MDMX can either act alone or form a heterocomplex with MDM2 and enhance ubiquitination of p53. There has been extensive validation of MDM2 and MDMX as a target showing that even a small reduction in MDM2 is significant enough to increase p53 activity. Targeting small molecules to specifically inhibit either MDM2 or MDMX could aid in more patient/tumor specific treatments [2, 12–15].

2. STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY OF MDM2 P53 INTERACTION

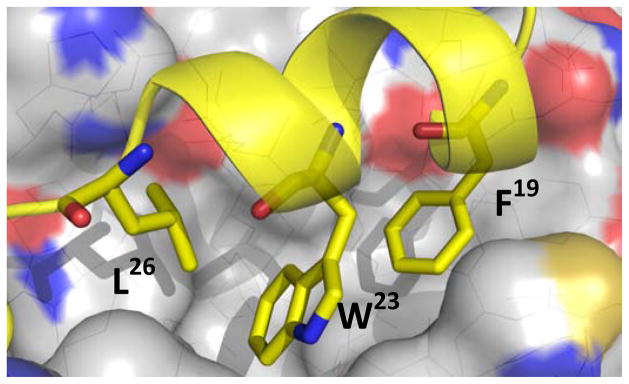

The 3D structure of MDM2 with and without p53 derived peptides and small molecules is extensively elaborated with more than 20 high resolution X-ray and NMR structures available in the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org). In a seminal work in 1996 Pavletich et al. described the first crystal structure of the interaction of p53/MDM2 (Fig. 2). MDM2 has a deep and structured binding pocket for p53. The binding pocket measures only 18 Å along the long edge; the size of a typical small molecule. The p53/MDM2 complex has a “hot spot triad” made up of p53’s Trp23, Leu26, and Phe19. The three hydrophobic amino acids fit into three shape and electrostatic complementary hydrophobic pockets, and the indole nitrogen of p53’s Trp23 forms a hydrogen bond with Leu54 of MDM2 (Met53 in MDMX). In fact much of the binding energy resides in these three amino acids. Alanine scan studies show that mutation of any of the three hot-spot amino acids destroys the affinity between p53 and MDM2. A prerequisite for high affinity MDM2 antagonists is therefore that certain moieties of the molecule must mimic the three amino acids of p53’s hot spot triad Trp23, Leu26, and Phe19. In fact an illustrative model termed “three finger pharmacophore” has been created [16–19].

Fig. 2.

Key amino acids of p53 (yellow) mounted on an alpha-helix bound to MDM2 (grey) (PDB-ID: 1YCR). (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3. NUTLIN

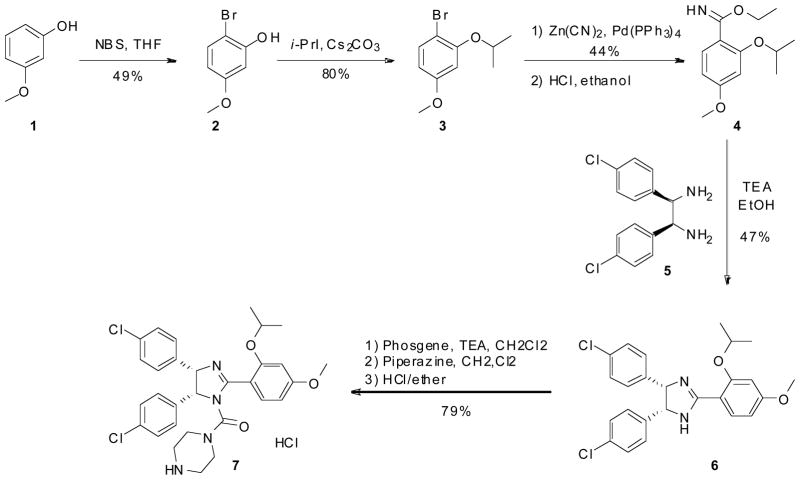

Hoffmann La Roche set out via high throughput screening to find potent and selective p53/MDM2 inhibitors. One class of compounds was a series of cis-imidazoline analogs termed Nutlins (Scheme 1). These compounds displaced p53 from MDM2 with an IC50 in the 100 to 300 nM range. Compounds were first screened as a racemic mixture however upon separation of enantiomers via use of a chiral column it was shown that (−)Nutlin-3 was 150 times more active than (+)Nutlin 3. Crystallographic studies showed the mode of binding of the Nutlin scaffold. The crystal structure of Nutlin-2 and MDM2 (Fig. 3) was solved and seen to bind to p53’s MDM2 pocket. One of the bromophenyl moieties sits deeply in the Trp23 pocket, while the other bromophenyl moiety sits in the Leu26 pocket. The ethyl ether side chain occupies the Phe19 pocket and the backbone of the imidazoline scaffold mimics the alpha helix of p53 [20].

Scheme 1.

Hoffmann la Roche’s synthesis of Nutlin-3.

Fig. 3.

A) Co-crystal of Nutlin 2 (purple) (PDB-ID: 1RV1) bound to MDM2 (grey), superimposed on key amino acids of p53/MDM2 co-crystal B) RG7112 (RO5045337) Roche’s Nutlin compound currently in clinical trial. (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Roche’s original synthesis of the Nutlin class of compound required an 8 step synthesis followed by chiral column separation (Scheme 1). Bromination of 3-Methoxyphenol (1) is followed by alkylation to give 1-bromo-2-isoproproxy-4-methoxybenzene (3). 3 then undergoes palladium catalyzed cyanation and treatment of the cyanide with hydrogen chloride in ethanol to give the imidate (4). The imidate was coupled with meso-(4-chlorophenyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (5) to give the imidazoline intermediate (6). Treatment of the imidazoline with phosgene and reaction of the resulting carbamoyl chloride with piperazine afforded Nutlin-3 (7). The compound must then be separated on a chiral column to separate the enantiomers [21].

Recently Johnston and Davis from Vanderbilt University reported a novel enantioselective synthesis of (−)-Nutlin-3 in only six steps (Scheme 2). Johnston and Davis describe the first highly diastero- and enantioselective addition of aryl nitromethane pronucleophiles (8) to aryl aldimines (9) using an electron rich chiral Bis(Amidine) catalyst (10) leading to the protected cis-stilbene (11). Boc-protected amide (13) was afforded via reduction of the nitro to amine using cobalt boride formed in situ followed by subsequent acylation with acid (12). Deprotection of the Boc group using trifluroacetic acid was followed by acylation of the amine with carbonyl diimidazole forming an isocyanate intermediate. This intermediate was treated with piperazinone. Cyclizative dehydration to the desired enantiomerically pure imidazoline, Nutlin-3 (14), was done via phosphonium anhydride formed by the combination of triphenylphosphine oxide and triflic anhydride. This synthesis removes Roche’s reliance on preparatory chromatography using a chiral stationary phase and substitutes it with a readily available chiral catalyst [22].

Scheme 2.

Enantioselective synthesis by Davis and Johnston of Hoffmann-La Roche’s Nutlin.

A derivative of Nutlin-3 is currently undergoing two Phase I clinical trials; one for hematological neoplasms and one for advanced solid tumor. RG7112 (RO5045337) (Fig. 3) is currently the most advanced small molecule inhibitor for p53/MDM2 inhibition. The study start date for the solid tumors trial was December 2007, and it is expected to be completed in June of 2012 (final data collection date for primary outcomes measure). The start date for the patients with hematologic neoplasms was May 2008, and will be completed in January 2013. The compound is dosed orally. The respective trials are performed in parallel to the development of p53 chip based diagnosis in order to identify potential responders to the therapy. First preliminary trial results with RG7112 look promising. Patients with relapsed/refractory leukemia were treated for 10 days orally in a dose escalation study from 20 mg m−2d−1 to 1920 mg m−2d−1 with continuous escalation. The p53 transcriptional target and secreted protein, MIC-1 served as a pharmacodynamic marker and increased with increasing drug concentration. One patient with relapsed AML achieved complete remission that is ongoing for more than 9 month. The studies therefore comprise a proof-of-principle showing p53 stabilization, activation of p53 targets and the p53 pathway. Future improved (better solubility, stability, and absorption) MDM2 antagonists hold the promise of even more selective and effective therapies. This therapy will potentially allow for a non-genotoxic treatment which does not cause damage to a patient’s DNA, and may be able to help avoid secondary tumors usually caused by other treatments [23–25].

4. SPIROOXINDOLES

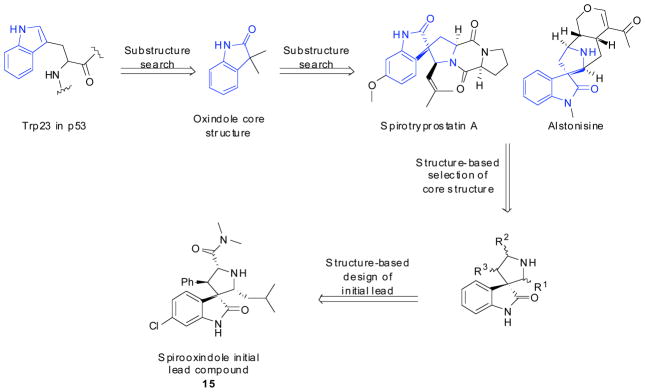

Shaomeng Wang, from the University of Michigan, describes a class of compounds known as spirooxindoles discovered using computational techniques. Wang et al describes use of p53’s Trp23 as a starting point and looked for molecules to mimic the interaction of p53’s Trp23 to MDM2. In addition to the indole ring, the oxindole was also found to be a perfect mimic for Trp23 in both the hydrogen bond formations and the potential hydrophobic interaction with MDM2. Substructure searches of natural products containing oxindole rings allowed them to identify a number of natural products, including natural alkaloids such as spirotryprostatin A and alstonisine which contain a spirooxindole core (Fig. 4). Though these specific compounds docked poorly into the MDM2 pocket, due to steric hindrance, they provided Wang et al with a starting point for the design of a new class of MDM2 inhibitors. The spiroindole ring provides a rigid scaffold from which two hydrophobic groups can project to mimic p53’s Phe19 and Leu26. From here computational docking studies were done on small molecules in this scaffold; compound (15) was predicted to have good affinity to MDM2. Compounds were screened via fluorescence polarization and compound (15) was shown to have a Ki of 8.46μM. Cellular studies of these compounds showed that the designed compounds were highly effective at inhibiting cell growth in wild type LNCaP human prostate cancer cells with 15 having an IC50 of 86nM. In human prostate cancer PC-3 cells with a deleted p53 these compounds showed much less potency as predicted, with compound 15 showing 22,500nM IC50. These compounds also showed significantly less toxicity in normal human prostate epithelial cells [26].

Fig. 4.

Wang et al.’s scheme for computational design of their spirooxindole compounds.

These compounds were synthesized via a multistep synthesis (Scheme 3), in high stereoselectivity. Briefly, oxindoles were condensed with different aromatic halides under basic conditions either in a microwave or under reflux to obtain E-3-aryl-1,3-dihydro-indol-2ones (16). In order to obtain appropriate stereochemistry (5R,6S)-5,6-diphenylmorpholin-2-one (18) is used as a chiral auxiliary promoting the stereocontrol seen in the final product. Asymmetric 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition was then done by heating the re-crystallized product 16 with alkyl aldehydes 17 and (5R,6S)-5,6-diphenylmorpholine 18 in toluene in the presence of a dehydrating agent. Compound (19) was partially purified by silica gel column and treated with 2M dimethylamine in THF to afford amides (20) in overall good yield. Analysis of both the intermediate and the final compound by X-ray crystallography revealed absolute configuration of the stereocenters [27].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Spirooxindole by Wang et al. Only a few examples of what was synthesized is shown.

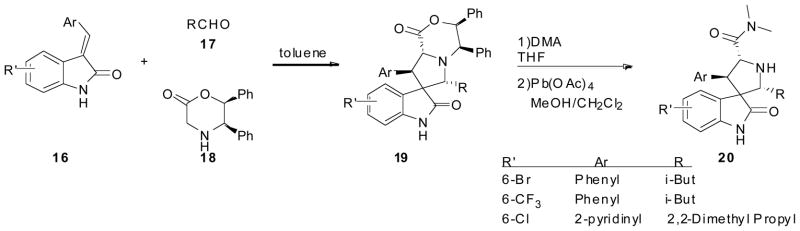

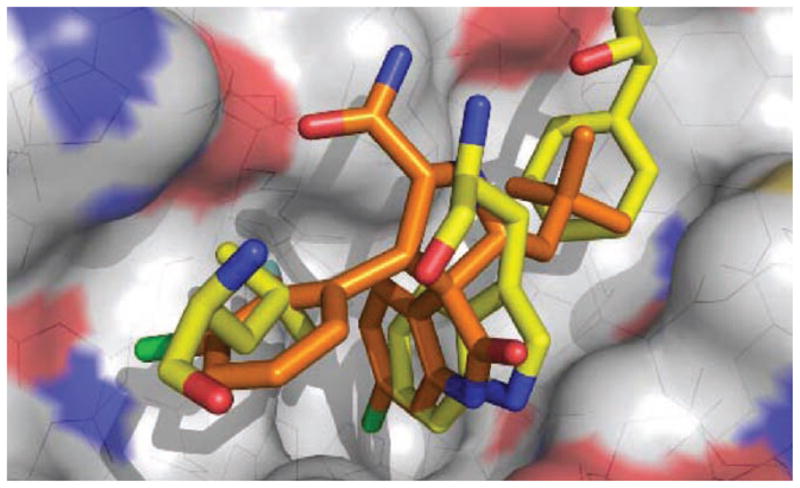

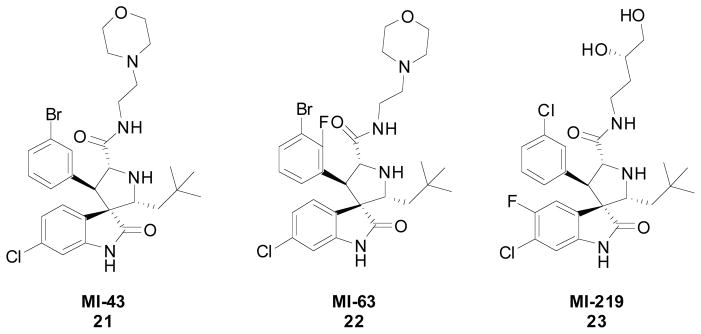

Though Wang’s compounds achieved high binding affinities they were still significantly less potent than most peptide based inhibitors. After their first round of compounds Wang attempted to modify the spirooxindole compounds to also fit into the p53’s Leu22 pocket. Since Leu22 is not buried deeply into the MDM2 cleft and is partially exposed to solvent this allowed for Wang to explore the addition of a polar moiety to not only mimic the hydrophobic interaction of Leu22 to MDM2 but also to introduce pharmacophores to improve physiochemical properties of the compounds such as aqueous solubility. Computational studies of the spirooxindole scaffold were done using the Leu22 as an additional pharmacophore site. Compound 21 (MI43) was assumed to closely mimic Leu22 at the two carbon linker between the morpholine ring and the 5′-carbonyl group. In addition it was thought that the oxygen of the morpholine ring would be in close proximity to the charged amine group in Lys90. This positively charged Lys90 is thought to have a charge-charge interaction to the carbonyl group in p53’s Glu17 [28]. Co-crystal analysis (Fig. 5) performed by Holak et al shows the oxindole group occupying the Trp23 pocket and also forming a hydrogen bond to MDM2’s Leu54 [29].

Fig. 5.

Co-crystal of spirooxindole (orange) (PDB-ID: 1RV1) bound to MDM2 (grey), superimposed on key amino acids of p53/MDM2 co-crystal. (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

MI43 (21) and MI-63 (22) (Fig. 6) had previously shown great binding affinity however were poor candidates for in vivo evaluation due to their poor PK profile. Extensive modification and in silico simulations led to MI219 (23) as a potent and selective MDM2 inhibitor with a desirable pharmacokinetic profile. Computational binding suggested that 23 would interact similarly to the key residues in p53, and in vitro screening showed that it binds with a Ki of 5 nM to MDM2 which is >1,000 fold more potent than p53 peptide. 23 is also seen to be specific to MDM2 over MDMX as it has an IC50 to MDMX of >100 μM and an estimated Ki of 55.7 μM. Cellular assays were performed on 23 similar to that of 21 and showed that 23 was a potent and selective p53/MDM2 inhibitor which induced apoptosis in cancer cells but not in normal cells. 23 showed good oral bioavailability and was therefore investigated in mouse xenograft models of human cancer. Immunohistochemical analysis showed that a single dose of 23 induced strong accumulation of p53 in the SJSA-1 tumor. Western blot data showed that as the levels of 23 decreased the levels of p53 activation in the tumor cells also decreased indicating that 23 was in fact inducing p53 activity. Tumor growth was next evaluated showing that at a 200 mg/kg dose twice a day 23 inhibited tumor growth 86% compared with the vehicle control and was more effective than once a day dosing. Toxicity studies also showed that though 23 induces p53 activity in normal cells it does not induce apoptosis consistent with the notion that established only tumors remain vulnerable to p53 tumor suppressor functionality [28],[30].

Fig. 6.

Spirooxindoes developed by Wang et al.

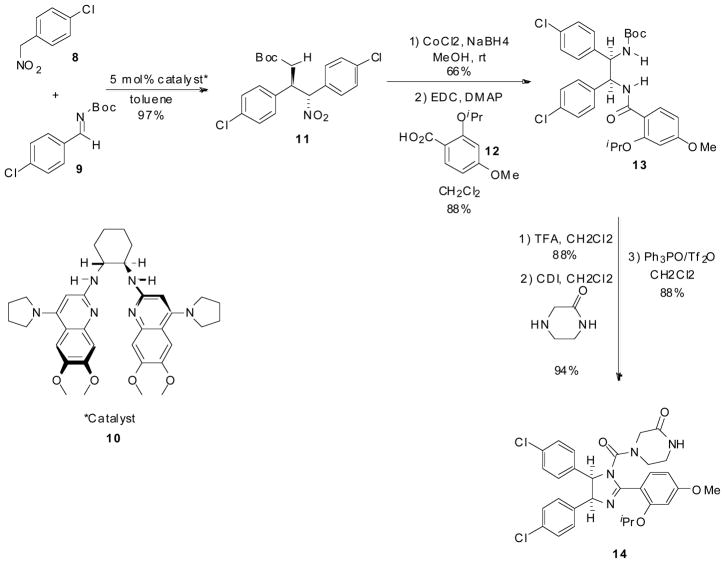

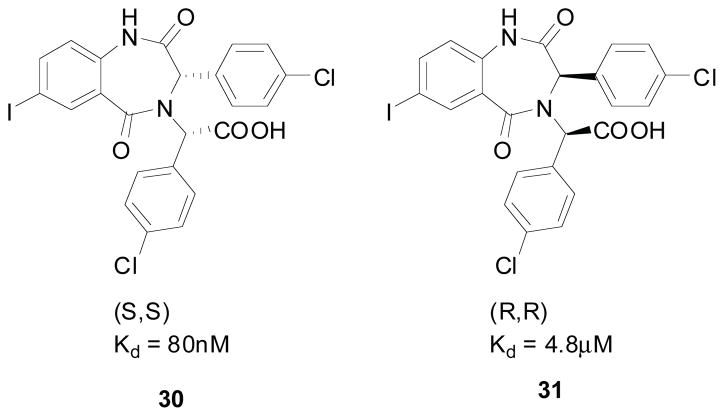

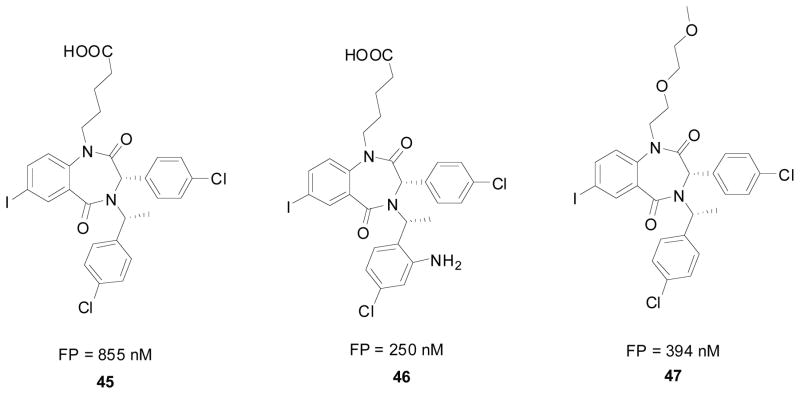

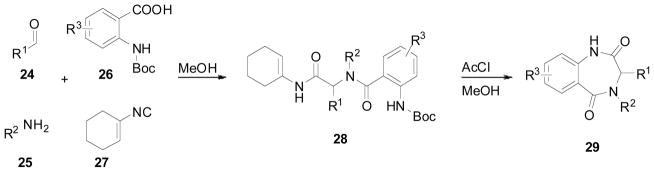

7. BDP (J&J)

Johnson and Johnson screened a library of 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-diones (BDP) for binding to the p53 domain of MDM2. The BDPs were synthesized in two steps (Scheme 4), the first of which was the highly efficient Ugi 4 component reaction. Equal parts of aldehyde (24), amine (25), N-protected anthranilic acid (26), and 1-isocyanidecyclohexene (27) were combined in methanol to produce the Ugi product (28). This step was followed by acid-catalyzed cyclization to afford the desired BDP (29) (Yields not disclosed). Due to the ease of the Ugi reaction, Johnson and Johnson was able to synthesize over 22,000 compound and screen them using a high throughput direct binding assay that measures the affinity of compound toward a MDM2 (residues 17–125). Hits were confirmed using Thermofluor fluorescence polarization assay. This showed a subset of BDPs containing α-amino esters as the amine component to have decent activity against p53/MDM2. Although the esters did show some activity in the assays, the low solubility precluded screening in the FP assay. BDP acids derived from the amino esters contained two chiral centers and were obtained as mixtures of di-astereomers. Chiral separation afforded two different compounds, typically with drastically different potencies. Substitutions on the phenyl ring showed that a Cl, CF3, or OCF3 showed the greatest increase in activity. Keeping these 3 substituents constant the acid side chain was explored. Aliphatic side chains were found to greatly decrease activity. Compounds containing a parachlorophenyl or parabromophenyl ring afforded compounds with sub micromolar activity; the first of the BDP series. Attempts to replace the iodo group on the benzodiazepine showed only decreases in activity [31].

Scheme 4.

2 step synthesis of Johnson and Johnson’s benzodiazepine.

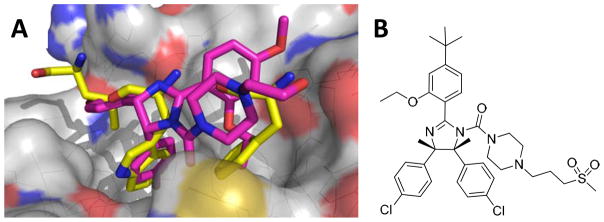

Their lead compound (Fig. 7) was then co crystallized with MDM2 to determine the binding mode of the BDPs. The compound like most other p53/MDM2 inhibitors fits into the Phe19, Trp23, and Leu26 pocket and makes hydrogen bonds to 3 different water molecules but none to MDM2. The interactions to MDM2 are largely nonspecific van der Waals contact. The hydrogen bonds can be removed without substantially affecting the affinity of the molecule to MDM2 [32].

Fig. 7.

Lead compounds of Johnson and Johnson’s benzodiazepine scaffold. It was found that the different diastereomers have drastically different activities.

The co-crystal structure (Fig. 8) shows the parachlorophenyl group derived from the α-amino ester starting material fits into the Leu26 pocket, the parachlorophenyl group derived from the aldehyde starting material fits into the Trp23 pocket similar to the chlorine containing oxindole from Wang et al, and the iodophenyl moiety binds in the Phe19 pocket [33]. The co-crystallized compound as well as other derivatives (Fig. 9) were studied in cellular based assays. The activities were dependent on the expression of wild type p53 and MDM2 as determined by lack of potency in mutant or null p53 expressing cell lines or cell lines which no longer express MDM2 and wild type p53 [34].

Fig. 8.

Co-crystal of J&J’s benzodiazepine (green) (PDB-ID: 1RV1) bound to MDM2 (grey), superimposed on key amino acids of p53/MDM2 co-crystal. (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Fig. 9.

Lead variations of J&J’s benzodiazepine scaffold.

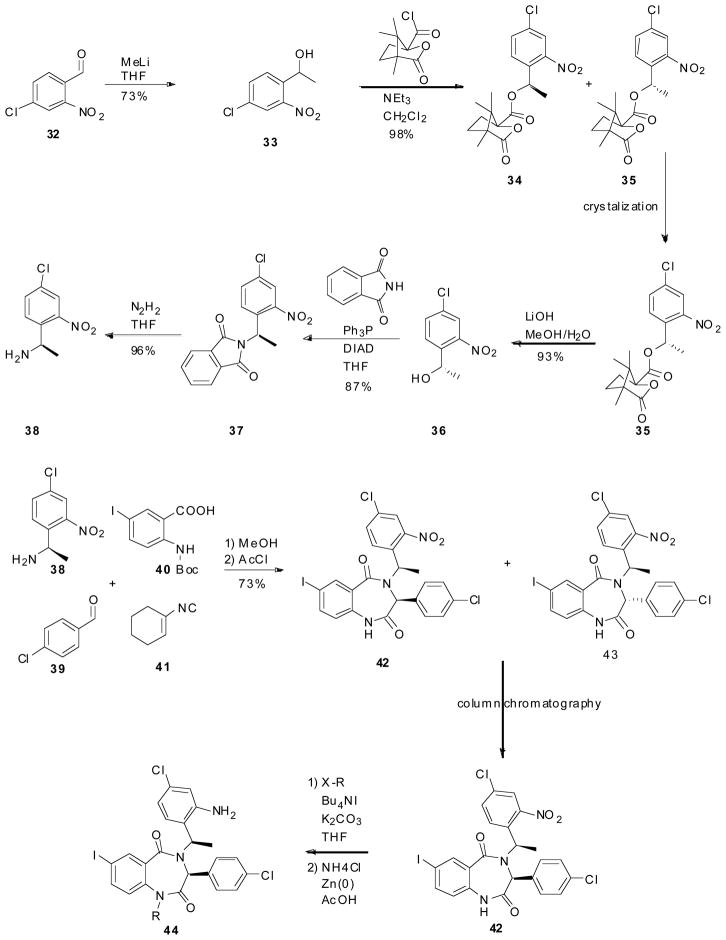

Given that this class of promising compounds contained two stereocenters and that the different diastereomers (30 and 31) were seen to have drastically different inhibitory activities (Fig. 7), J&J set it upon themselves to obtain enantiomerically pure BDPs (Scheme 5). The synthetic strategy consisted of the preparation and selective crystallization of the diastereomeric camphanic esters. Compound 32 was treated with methyl lithium to give the corresponding racemic alcohol 33, which was treated with camphanic chloride, followed by selective re-crystallization to give 35. 35 was then transformed to the corresponding amine 38 via hydrolysis (36), followed by the Mitsunobu reaction with phthalimide (to give 37), and finally deprotection with hydrazine. This amine (38) is then ready for use in the Ugi reaction followed by cyclization as described above. The reaction gives a mix of the two different diastereomers (42 and 43) which are separated via column chromatography. The separated diastereomers (42) then undergoes alkylation followed by reduction of the nitro group to give the corresponding MDM2 antagonist (44); X-ray structure confirmed stereochemistry [35].

Scheme 5.

Enantioselective synthesis of J&J’ s benzodiazepine scaffold.

Compound 45 was shown to be a potent inhibitor of p53/MDM2 in cellular assays and was improved by the introduction of an ortho amino functionality to the benzylic ring 46. The increase in activity, seen in the FP assay (from 0.85uM to 0.25uM), is believed to be due to an extra donor hydrogen bond interaction between the amino group and the carbonyl of Val93 on MDM2. However this compound was found to be less potent in cell based assay, most likely due to its zwitterionic characteristic which limits the cross membrane permeability and adversely modulates the availability of the compound to MDM2. Changing the valeric acid side chain with a non-charged side solubilizing group, such as the methoxyethoxyethyl side chain 47 lead to a slight decrease in the FP assay but an increase in the cellular assay indicating that this compound is able to penetrate the cell unlike 46. When this group is switched out for a morpholino side chain as a solubilizing group the cellular activity increased even more. However when the orthoamine hydrogen bond donor group was replaced a loss of activity in FP assay and no cellular activity was observed [36].

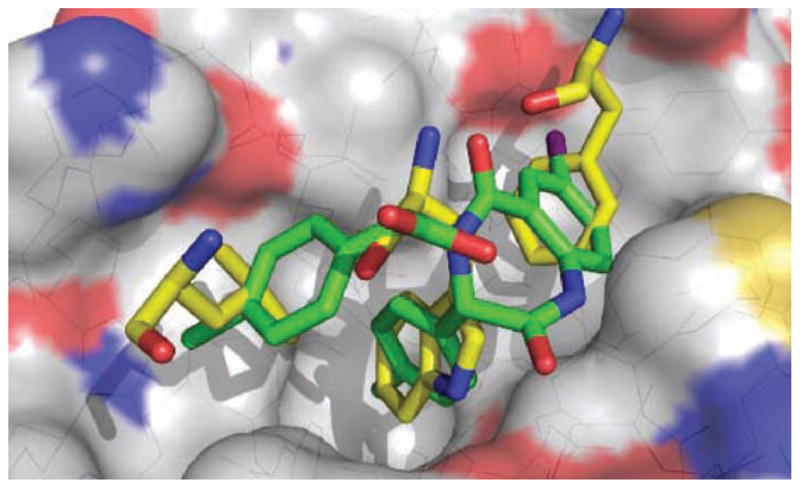

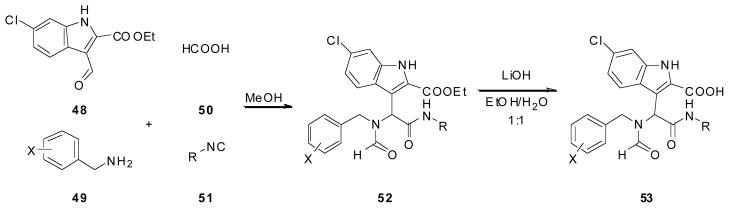

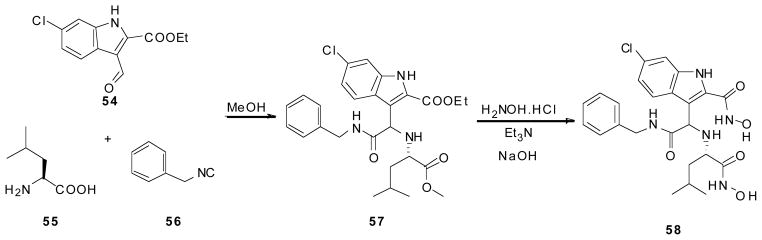

8. UGI BACKBONE

Alexander Dömling, from the University of Pittsburgh in collaboration with Tad Holak from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry has described a number of unprecedented multicomponent reaction scaffolds that are able to efficiently disrupt the p53/MDM2 interaction [29, 37–39]. Recently they published a series of acyclic compounds synthesized via variations of the classic Ugi reaction [40, 41]. Using an in house pharmacophore based virtual screening platform ANCHOR.QUERY [42] Dömling et al synthesized and screened compounds from the Ugi-4-component reaction (Scheme 6) and the Ugi-4-component-5-centered (U4C5Cr) reaction (Scheme 7). The Ugi-4-component products (52) were formed by taking one equivalent each of, ethyl-6-chloroindole-2-carboxylate (48), a benzyl amine (49), formic acid (50), and an isocyanide (51) in methanol. The corresponding acid (53) was achieved by treating the Ugi product (52) with lithium hydroxide in a mixture of ethanol and water (Scheme 6). The co-crystal structure of the small molecule in MDM2 (Fig. 10) showed that the benzyl amine portion of the small molecule had a parallel alignment to His96 of MDM2 which indicated π-π stacking between the small molecule and the protein. Dömling et al took this opportunity to optimize this interaction by synthesizing all 19 possible isomers with different fluorine substitution patterns at the benzyl position [40]. Compounds were screened as racemic mixtures, however co-crystal analysis (Fig. 10) showed that only one enantiomer was the active form. It was found that 3,4,5-tri-fluro benzyl amine achieved the greatest binding constant of 130nM. Co-crystal analysis confirmed the expected binding mode of the 6-chloroindole moiety aligning with the Trp23 of p53, forming a hydrogen bond with Leu54 of MDM2. The benzyl group mimics the Leu26 of p53, and the tert-butylamide substituent derived from the isocyanide was deeply buried in the Phe19 pocket. As seen previously there was a nice π-π stacking between the 3,4-di-fluoro benzyl amine and His96 of MDM2 (Fig. 10) [40].

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of Dömling et al’s acyclic Ugi-4-component p53/MDM2 inhibitor.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of Dömling et al’s acyclic Ugi-4-component-5-centered p53/MDM2 inhibitor.

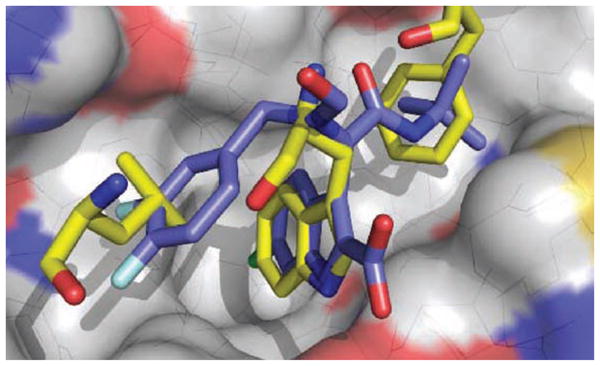

Fig. 10.

Co-crystal of Dömling et al’s Ugi-4-component reaction product (blue) (PDB-ID: 3TU1) bound to MDM2 (grey), superimposed on key amino acids of p53/MDM2 co-crystal. (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Using this same class of molecules, as well as compounds produced via the U4C5Cr reaction, this group discloses the discovery of a second binding pocket which till now has never before been seen. Very similar to the Ugi-4-component, the U4C5Cr reaction starts with Ethyl-6-chloroindole-2-carboxylate (54), benzyl isocyanide (56), and an amino acid (55), which acts as both the amine and acid component in the reaction, in methanol. This compound (57) then undergoes hydroxyamidation by adding excess of hydroxylamine and sodium hydroxide, in triethylamine; the product (58) precipitated out as a white solid (Scheme 7). This compound, as well as another derivative of the Ugi-4-component reaction show a never before seen pocket open in the MDM2 protein (not shown), which extends the ligand-protein interaction site [41]. In addition to their great protein binding activity these compounds have also shown activity in Leukemia cells (AML). (not published)

OUTLOOK

The protein protein interaction of the transcription factor p53 and its negative regulator MDM2 and MDMX is a highly competitive field in drug discovery with one compound in early clinical development and several compounds in the preparation to enter clinical evaluation in cancer. p53/MDM2 as a non genotoxic treatment thus comprises a new paradigm for fighting cancer. As always in drug discovery the success of particular compounds depends on many factors including their drug like properties such as lipophilicity, stability, water solubility, molecular weight and toxicity. From current available data it can confer the compounds with drug like properties is the domain on medicinal chemists who will have to understand the requirements of PPI antagonists as opposed to compounds targeting other classes of proteins such as proteases or kinases. However the current success of discovery and developing PPI antagonist point to a bright future for this area of discovery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant P41 GM094055-02 and 1R01GM097082-01 and by a grant of the Qatar National Science Foundation NPRP 4-319-3-097.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lane DP, Crawford LV. T antigen is bound to a host protein in SV40-transformed cells. Nature. 1979;278(5701):261–3. doi: 10.1038/278261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown C, Lain S, Verma C, Fersht A, Lane D. Awakening guardian angels: drugging the p53 pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(12):862–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liau LM, Weaver CH. Ted Kennedy’s Recent Diagnosis of Glioblastoma Raises Awareness of Brain Cancer. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halatsch ME, Schmidt U, Unterberg A, Vougioukas VI. Uniform MDM2 overexpression in a panel of glioblastoma multiforme cell lines with divergent EGFR and p53 expression status. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(6B):4191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wade M, Wahl GM. Targeting Mdm2 and Mdmx in cancer therapy: better living through medicinal chemistry? Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(1):1–11. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal F, Wade M, Godes M, et al. A stapled p53 helix overcomes HDMX-mediated suppression of p53. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):411–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoury K, Popowicz GM, Holak TA, Dömling A. The p53-MDM2/MDMx axis - A chemotype perspective. Med Chem Comm. 2011;2:246–60. doi: 10.1039/C0MD00248H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell’s response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(8):594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356(6366):215–21. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marine J-CW, Dyer MA, Jochemsen AG. MDMX: From Bench to Bedside. J of Cell Science. 2007;120(3):371–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(12):909–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu X, Bayle JH, Olson D, Levine AJ. The p53-mdm-2 autoregulatory feedback loop. Genes Dev. 1993;7(7A):1126–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momand J, Zambetti G, Olson D, George D, Levine A. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69(7):1237–45. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danovi D, Meulmeester E, Pasini D, et al. Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) directly contributes to tumor formation by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24(13):5835–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5835-5843.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riemenschneider MJ, Buschges R, Wolter M, et al. Amplification and overexpression of the MDM4 (MDMX) gene from 1q32 in a subset of malignant gliomas without TP53 mutation or MDM2 amplification. Cancer Res. 1999;59(24):6091–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clackson T, Wells JA. A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone-receptor interface. Science. 1995;267(5196):383–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7529940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kussie PH, Gorina S, Marechal V, et al. Structure of the MDM2 Oncoprotein Bound to p53 Tumor Suppressor Transactivation Domain. Science. 1996;274:948–53. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picksley SM, Vojtesek B, Sparks A, Lane DP. Immunochemical analysis of the interaction of p53 with MDM2;--fine mapping of the MDM2 binding site on p53 using synthetic peptides. Oncogene. 1994;9(9):2523–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dömling A., inventor Selective and Dual-Action p53/MDM2/MDM4 Antagonists patent. WO/2008/130614. 2008

- 20.Klein C, Vassilev LT. Targeting the p53-MDM2 interaction to treat cancer. British journal of cancer. 2004;91:1415–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fry DC, Emerson SD, Palme S, et al. NMR structure of a complex between MDM2 and a small molecule inhibitor. J Biomol NMR. 2004;30(2):163–73. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000048856.84603.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis TA, Johnston JN. Catalytic, enantioselective synthesis of stilbene cis-diamines: A concise preparation of (−)-Nutlin-3, a potent p53/MDM2 inhibitor. Chemical Science. 2011;2:1076–9. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00061F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study of RO5045337 [RG7112] Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24.ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study of RO5045337 [RG7112] Patients With Hematologic Neoplasms. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreeff M, Kojima K, Padmanabhan S, et al. Small Molecule May Disarm Enemy of Cancer-Fighting p53. American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; San Diago, CA. 2010; p. Abstract #657. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding K, Lu Y, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, et al. Structure-based design of potent non-peptide MDM2 inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(29):10130–1. doi: 10.1021/ja051147z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding K, Wang G, Deschamps JR, Parrish Da, Wang S. Synthesis of spirooxindoles via asymmetric 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Tetrahedron Letters. 2005;2005(35):5949–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shangary S, Ding K, Qiu S, et al. Reactivation of p53 by a specific MDM2 antagonist (MI-43) leads to p21-mediated cell cycle arrest and selective cell death in colon cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(6):1533–42. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popowicz GM, Czarna A, Wolf S, et al. Structures of low molecular weight inhibitors bound to MDMX and MDM2 reveal new approaches for p53-MDMX/MDM2 antagonist drug discovery. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(6) doi: 10.4161/cc.9.6.10956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shangary S, Qin D, McEachern D, et al. Temporal activation of p53 by a specific MDM2 inhibitor is selectively toxic to tumors and leads to complete tumor growth inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(10):3933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708917105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parks DJ, Lafrance LV, Calvo RR, et al. 1,4-Benzodiazepine-2,5-diones as small molecule antagonists of the HDM2-p53 interaction: discovery and SAR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15(3):765–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grasberger BL, Lu T, Schubert C, et al. Discovery and cocrystal structure of benzodiazepinedione HDM2 antagonists that activate p53 in cells. J Med Chem. 2005;48(4):909–12. doi: 10.1021/jm049137g. Epub 2005/02/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cummings MD, Schubert C, Parks DJ, et al. Substituted 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-diones as alpha-helix mimetic antagonists of the HDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;67(3):201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koblish HK, Zhao S, Franks CF, et al. Benzodiazepinedione inhibitors of the Hdm2: p53 complex suppress human tumor cell proliferation in vitro and sensitize tumors to doxorubicin in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(1):160–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marugan JJ, Leonard K, Raboisson P, et al. Enantiomerically pure 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-diones as Hdm2 antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;16(12):3115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parks DJ, LaFrance LV, Calvo RR, et al. Enhanced pharmaco-kinetic properties of 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-dione antagonists of the HDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction through structure-based drug design. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16(12):3310–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czarna A, Beck B, Srivastava S, et al. Robust generation of lead compounds for protein-protein interactions by computational and MCR chemistry: p53/Hdm2 antagonists. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(31):5352–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y, Wolf S, Bista M, et al. 1,4-Thienodiazepine-2,5-diones via MCR (I): synthesis, virtual space and p53-Mdm2 activity. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2010;76(2):116–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2010.00989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava S, Beck B, Wang W, et al. Rapid and efficient hydrophilicity tuning of p53/mdm2 antagonists. J Comb Chem. 2009;11(4):631–9. doi: 10.1021/cc9000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang Y, Wolf S, Koes D, et al. Exhaustive Fluorine Scanning toward Potent p53-Mdm2 Antagonists. ChemMedChem. 2012;7(1):49–52. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bista M, Khoury K, Wolf S, et al. Discovery of an unusual ligand-induced binding pocket in MDM2. PNAS. 2012 Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koes D, Khoury K, Huang Y, et al. Enabling large-scale design, synthesis and validation of small molecule protein-protein antagonists. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e32839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]