Abstract

Background

Opioid analgesics are effective for postsurgical pain but are associated with opioid-related adverse events, creating a significant clinical and economic burden. Gastrointestinal surgery patients are at high risk for opioid-related adverse events. We conducted a study to assess the impact of an opioid-sparing multimodal analgesia regimen with liposome bupivacaine, compared with the standard of care (intravenous [IV] opioid-based, patient-controlled analgesia [PCA]) on postsurgical opioid use and health economic outcomes in patients undergoing ileostomy reversal.

Methods

In this open-label, multicenter study, sequential cohorts of patients undergoing ileostomy reversal received IV opioid PCA (first cohort); or multimodal analgesia including a single intraoperative administration of liposome bupivacaine (second cohort). Rescue analgesia was available to all patients. Primary outcome measures were postsurgical opioid use, hospital length of stay, and hospitalization costs. Incidence of opioid-related adverse events was also assessed.

Results

Twenty-seven patients were enrolled, underwent the planned surgery, and did not meet any intraoperative exclusion criteria; 16 received liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia and eleven received the standard IV opioid PCA regimen. The multimodal regimen was associated with significant reductions in opioid use compared with the IV opioid PCA regimen (mean, 20 mg versus 112 mg; median, 6 mg versus 48 mg, respectively; P < 0.01), postsurgical length of stay (median, 3.0 days versus 5.1 days, respectively; P < 0.001), and hospitalization costs (geometric mean, $6482 versus $9282, respectively; P = 0.01).

Conclusion

A liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesic regimen resulted in statistically significant and clinically meaningful reductions in opioid consumption, shorter length of stay, and lower inpatient costs than an IV opioid-based analgesic regimen.

Keywords: surgery, ileostomy, multimodal analgesia, opioid-related adverse events, hospitalization cost, length of stay

Introduction

The efficacy of opioid analgesics has led to their widespread adoption as the main component of perioperative and postsurgical pain control regimens.1,2 However, opioid-related adverse events (ORAEs) create a significant clinical and economic burden in the postsurgical setting, including increased per-patient cost and length of stay (LOS).1–3 One 10-year study of admissions at a single hospital found that ORAEs were associated with a 16% increase in hospitalization costs and a 0.5-day increase in LOS.1 The risk and impact of ORAEs, including postoperative ileus and intestinal obstruction, appear to be dose-related and particularly severe in patients undergoing gastrointestinal (GI) surgery.4–9

Among patients undergoing ileostomy reversal, the overall rate of postsurgical complications (including ORAEs) is high, with reported complication rates ranging from 17% to 37%.10–20 GI motility complications (including postoperative ileus and intestinal obstruction or small bowel obstruction) are among the most frequent complications of ileostomy reversal, with reported rates of 5%–12%.11–17,19,20 Perioperative opioid use is likely to exacerbate the burden of GI motility and other complications.4–6,8 In a retrospective study of 279 patients who underwent elective colorectal surgery, Barletta et al6 showed that intravenous (IV) hydromorphone doses of as little as 2 mg per day were associated with about a 10-fold increase in postoperative ileus (odds ratio [OR] 9.9; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2 to 82.2; P = 0.03) compared with lower doses, and a median 1-day increase in length of hospital stay (5 days versus 4 days; P < 0.001). Conversely, a reduction in perioperative opioid use may be expected to reduce the risk of postoperative ORAEs, including those related to GI motility.

Liposome bupivacaine is a multivesicular liposomal formulation of the local anesthetic bupivacaine (EXPAREL®; Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Parsippany, NJ, USA), designed to extend the duration of analgesia with a single administration. It is currently indicated for administration into the surgical site to produce postsurgical analgesia.21 In clinical studies involving five different surgical settings, the intraoperative administration of a single dose (range, 66 to 532 mg) of liposome bupivacaine has been shown to be well tolerated and to provide analgesia for up to 72 hours after administration.22,23 In addition to providing extended analgesia, liposome bupivacaine also increased the time to first opioid use and reduced the use of opioids overall.22,24

A series of open-label Phase IV studies (designated the PaIn Relief Trial Utilizing the Infiltration of a Long-Acting Multivesicular LiPosome FoRmulation Of BupiVacaine, EXPAREL [IMPROVE]) was designed to evaluate the impact of an opioid-sparing multimodal analgesic regimen incorporating liposome bupivacaine compared with opioid-based patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) on clinically meaningful and economically impactful postsurgical outcomes in three models of GI surgery (open colectomy, laparoscopic colectomy, and ileostomy reversal). Cohen25 previously reported results from a single-center open colectomy study, in which patients receiving liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia experienced statistically significant and clinically meaningful reductions in postsurgical opioid consumption, cost of hospitalization, and postsurgical LOS compared with patients receiving opioid-based analgesia.25

The current study, which is essentially identical in design to the open colectomy study, is the first multicenter IMPROVE study to be reported. The study objective was to assess the impact of liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia versus an opioid-based analgesia regimen on total opioid use and health economic outcomes in adult patients undergoing ileostomy reversal with general anesthesia.

Methods

This was a Phase IV prospective, multicenter, open-label, sequential-group study designed to evaluate the opioid burden and health economic outcomes associated with a multimodal analgesia regimen incorporating intraoperatively administered liposome bupivacaine 266 mg (the standard US Food and Drug Administration-approved dose) compared with an IV opioid-based regimen with PCA. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee at each study center, and the study was conducted in accordance with the International Committee on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guide-lines.26 All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Twenty-seven adults (18 men and 9 women) 18 years of age or older who were undergoing ileostomy reversal surgery were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or not willing to use appropriate contraceptive methods; or if they had severe hepatic impairment; had a history of drug/alcohol abuse; had any concomitant condition that could preclude study participation; or had received intraoperative analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), local anesthetics, or alvimopan during surgery.

Except for the change in surgical model and the multicenter nature of this study, overall study methodology was essentially identical to that used in the single-center study in open colectomy patients reported by Cohen.25 Eligible patients were enrolled in sequential cohorts (IV opioid PCA cohort first, followed by the liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia cohort) by the study investigators at three study centers; all screening procedures were conducted within 2 weeks of surgery.

On the day of surgery (study day 1), for patients assigned to the IV opioid PCA cohort, study treatment was initiated as soon as possible following surgery. For patients assigned to liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia, a single dose of liposome bupivacaine (266 mg in 30 mL 0.9% normal saline) was administered using a moving-needle technique prior to the end of surgery. Administration was divided evenly between the left and right sides of the surgical site; approximately 75% was infused into the perifascial region and the remaining 25% was infused into the junction between the subcutaneous and dermal regions. Patients assigned to the multimodal regimen also received 30 mg ketorolac IV (or alternative NSAID equivalent) at the end of surgery, followed by 1000 mg acetaminophen (IV or oral) every 6 hours for 72 hours postsurgery, as well as oral ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours for 72 hours, starting when oral therapy was first tolerated. Rescue therapy with IV opioid and/or oxycodone/acetaminophen 5 mg/325 mg was available to all patients on an as-needed basis (acetaminophen use was limited to 4000 mg/day).

Postsurgical IV PCA and rescue analgesia were continued as needed until hospital discharge; cumulative opioid usage and adverse events (AEs) were recorded through discharge or day 30 (whichever was earlier). On day 30, AEs were assessed and patient follow-up surveys were conducted with regard to postsurgical complications and satisfaction with postsurgical analgesia.

The primary outcome measures were total postsurgical opioid consumption (oral and IV) until discharge or study day 30, whichever came first; total cost of hospitalization until discharge or study day 30, whichever came first; and postsurgical LOS, defined as the time in hours between wound closure and discharge or through day 30. Hospital costs were obtained by using medical billing claim forms. Secondary outcome measures included time to first opioid administration, overall patient satisfaction with postsurgical analgesia (assessed on day 30 using a 5-point Likert scale), and patient responses to a follow-up survey administered on day 30 with respect to hospital readmission, unplanned medical visits, contact with physician to discuss recovery, and health-related problems during recovery. ORAEs, defined as somnolence, respiratory depression, hypoventilation, hypoxia, dry mouth, nausea, vomiting, constipation, sedation, confusion, pruritus, urinary retention, or postoperative ileus, were monitored through day 30.

The safety population included all patients who underwent the planned surgery. The efficacy population included all patients who underwent surgery as planned and did not receive intraoperative administration of analgesics (other than fentanyl or analogs), local anesthetics, anti-inflammatory agents, or alvimopan. Between-group comparisons for continuous efficacy measures (such as opioid consumption) were made using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) model after a natural logarithm transformation was applied to the data, with two-sided 95% CIs calculated for all differences. All opioid consumption amounts were converted to morphine equivalents prior to statistical analysis. Between-group comparisons for categorical measures were conducted using Fisher’s exact test. Between-group differences in postsurgical LOS and time to first opioid administration were tested using a log-rank test. All tests for significance were two-sided and based on a significance level of 0.05; no adjustments of the significance level were made for multiple tests.

Results

After enrolling only 32 patients, the study sponsor reviewed the data and determined that statistically significant differences between the treatment groups had been reached; therefore, the study was stopped. Of the 27 patients who underwent the planned surgery and did not meet any of the intraoperative exclusion criteria (efficacy population), eleven received the IV opioid PCA-based regimen and 16 received liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics (efficacy population)

| Attribute | IV opioid PCA regimen (n = 11) | Liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal regimen (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 53 (18) | 51 (16) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 8 (73) | 10 (63) |

| Female | 3 (27) | 6 (38) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 8 (73) | 14 (88) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 (27) | 0 |

| Black | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.1 (5.4) | 24.6 (4.2) |

| ASA physical status classification, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 1 (9) | 1 (6) |

| 2 | 6 (55) | 6 (38) |

| 3 | 4 (36) | 9 (56) |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; IV, intravenous; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; SD, standard deviation.

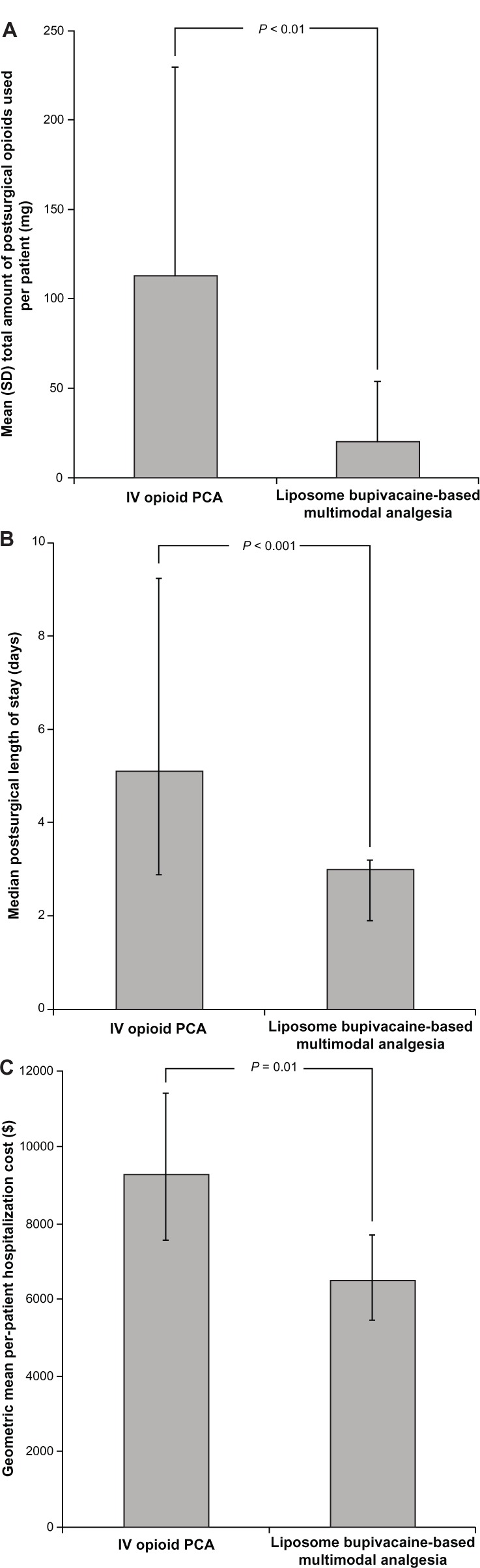

With respect to the primary outcome measures, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) postsurgical opioid consumption in morphine equivalents was 20 (34) mg in the liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia group (median, 6 mg; range, 0–129 mg) compared with 112 (117) mg in the IV opioid PCA group (median, 48 mg; range, 0–342 mg; P < 0.01; Figure 1A). The median (range) duration of hospital stay after surgery was 3.0 (0.8, 5.0) days in the multimodal analgesia group compared with 5.1 (2.2, 31.9) days in the IV opioid PCA group (Figure 1B, P < 0.001). The geometric mean cost of hospitalization was $6482 (median, $6413; range, $3783–$10,637) in the multimodal analgesia group compared with $9282 (median, $9702; range, $5060–$17,659) in the IV opioid PCA group (Figure 1C, P = 0.01).

Figure 1.

Primary outcome measures; comparison of study primary outcome measure results for patients receiving IV opioid-based analgesia or liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia.

Notes: (A) Mean per-patient amount of postsurgical opioids consumed (morphine equivalent, mg). Error bars represent standard deviation. (B) Median postsurgical length of stay (days). Error bars represent range for 95% of values around the median. (C) Geometric mean per-patient hospitalization costs (USD$). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the geometric mean.

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; SD, standard deviation.

With respect to secondary outcome measures, the median length of time to first opioid use was longer in the liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia group (2.9 hours) compared with the IV opioid PCA group (0.6 hours, P = 0.04). The proportion of patients who were extremely satisfied with their postsurgical pain treatment was higher, and the proportion who made unplanned visits and/or contact with a health care provider to discuss recovery after surgery was lower in the multimodal analgesia group compared with the IV opioid PCA group. The proportions requiring readmission to the hospital and experiencing postsurgical health problems were higher in the multimodal analgesia group. However, none of these between-group differences achieved statistical significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results for secondary efficacy outcome measures (efficacy population)a

| Outcome measure | IV opioid PCA regimen (n = 11) | Liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal regimen (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Median time (range) to first opioid use, hours | 0.6 (0.3, 70.0) |

2.9 (0.3, 120.0) |

| Proportion of patients who: | ||

| Reported being extremely satisfied with their postsurgical pain treatment, % | 36 | 63 |

| Made unplanned visits with a health care provider after surgery, % | 9 | 0 |

| Made contact with health care provider to discuss recovery after surgery, % | 9 | 0 |

| Needed to be readmitted to the hospital after surgery, % | 0 | 13 |

| Reported health problems or changes in health after hospital discharge, % | 9 | 13 |

Notes:

P = 0.04 for between-group comparison of time to first opioid use; between-group comparisons showed no statistical differences for any of the other outcomes listed.

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.

Overall, 15 patients (47%) experienced AEs (Table 3). The most frequently reported AEs were nausea (22%), abdominal distension (16%), and vomiting (13%). Two patients experienced serious AEs; one patient in the IV opioid PCA group experienced gastrointestinal hemorrhage and one in the liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia group had a serious AE of pancreatitis. None of the AEs reported during the study were considered related to study drug by the investigators. Opioid-related AEs (based on the efficacy population) were reported by 4/11 patients (36%) in the IV opioid PCA group compared with 4/16 patients (25%) in the multimodal analgesia group (P = 0.68). The mean (SD) per-patient number of ORAEs was 0.5 (0.8) in the opioid analgesia group compared with 0.3 (0.5) in the multimodal analgesia group (P = 0.41). Across both treatment groups, reported ORAEs included nausea in 5/27 (19%), vomiting in 3/27 (11%), and urinary retention and postoperative ileus in 1/27 (4%) patients.

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events (safety population)

| Adverse events | IV opioid PCA regimen (n = 15) | Liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal regimen (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with any adverse event, n (%) | 7 (47) | 8 (47) |

| Nausea | 4 (27) | 3 (18) |

| Abdominal distension | 3 (20) | 2 (12) |

| Vomiting | 1 (7) | 3 (18) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (13) | 1 (6) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (7) | 2 (12) |

| Fecal incontinence | 3 (20) | 0 |

| Anal injury | 2 (13) | 0 |

| Urinary retention | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| Anal pruritus | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Frequent bowel movements | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Hematochezia | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Incisional drainage | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Incision site edema | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Incision site erythema | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Incision site pain | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Influenza | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Pancreatitis | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Postoperative ileus | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Sinus headache | 1 (7) | 0 |

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.

Discussion

In this multicenter, open-label study of patients undergoing ileostomy reversal surgery, the use of a liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia regimen for postsurgical analgesia was associated with a statistically significant 82% reduction in mean total amount of opioids consumed after surgery. The liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia regimen was also associated with a median postsurgical LOS that was 2 days shorter than the median for the IV opioid PCA group, which was also statistically significant. Given the lower opioid use and shorter hospital stays observed with multimodal treatment, it is not surprising that hospitalization costs were significantly lower in this group as well; about 70% lower (≈$2800 lower). The results we observed on these outcome measures are consistent with results observed in the open colectomy study reported by Cohen.25 The results of the secondary outcome assessments and incidence of reported ORAEs also favored the multimodal analgesia group, although the study was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference between the two groups. Nevertheless, based on the data compiled from the secondary measures, it appears the liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesic regimen was well accepted by the patients in this group.

We are unable to provide context for the results observed in our study versus other similar studies, since there is a paucity of published data from studies assessing the effects of different analgesic regimens in patients undergoing ileostomy closure/reversal. To our knowledge, there is only one other published comparative study in this surgical setting – a retrospective study reported by Amlong et al,27 which evaluated the analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block with bupivacaine HCl or ropivacaine (n = 31) versus no transversus abdominis plane block (n = 38); postoperative analgesics were administered to patients in both groups at the discretion of the attending medical teams. In that study, the mean postoperative opioid requirements were significantly lower in the transversus abdominis plane block group during the first 24 hours after surgery (60 mg) compared with the control group (104 mg, P = 0.01), although the average length of hospital stay was not statistically different between groups (5.8 days versus 4.6 days, respectively; P = 0.828).

Regarding observed wound-related adverse events in this study, there were no incidences of incisional site drainage, edema, erythema, or pain reported after surgery in the liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal analgesia group. These results were not unexpected, given the previously reported data from ten clinical studies of 823 liposome bupivacaine-treated patients with no negative impact on wound healing observed with this compound.28

Study limitations included the open-label design, as well as the use of sequential cohorts in lieu of randomization, which might have introduced possible temporally-driven variation between study groups and/or bias by the investigators. In addition, the study was not sufficiently powered to demonstrate statistically significant between-group differences in secondary efficacy outcomes and incidences of ORAEs, or across patient subgroups stratified by age, gender, race, or comorbidities. Finally, although the design of the study may confound attribution of treatment effects to any one of the specific analgesics used in the multimodal analgesia group, the liposome bupivacaine-based multimodal regimen nonetheless resulted in statistically significant and clinically meaningful reductions in opioid consumption, shorter LOS, and lower inpatient costs than an IV opioid-based analgesic regimen.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Editorial assistance was provided by Peloton Advantage, LLC, and supported by Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The authors were fully responsible for the content, editorial decisions, and opinions expressed in the current article. The authors did not receive an honorarium related to the development of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

SL is a speaker for Applied Medical Resources and Covidien. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Oderda GM, Evans RS, Lloyd J, et al. Cost of opioid-related adverse drug events in surgical patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(3):276–283. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oderda GM, Said Q, Evans RS, et al. Opioid-related adverse drug events in surgical hospitalizations: impact on costs and length of stay. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(3):400–406. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler M, Oderda GM, Ashburn MA, Lipman AG. Adverse events associated with postoperative opioid analgesia: a systematic review. J Pain. 2002;3(3):159–180. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.123652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senagore AJ. Pathogenesis and clinical and economic consequences of postoperative ileus. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(20 Suppl 13):S3–S7. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goettsch WG, Sukel MP, van der Peet DL, van Riemsdijk MM, Herings RM. In-hospital use of opioids increases rate of coded postoperative paralytic ileus. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(6):668–674. doi: 10.1002/pds.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barletta JF, Asgeirsson T, Senagore AJ. Influence of intravenous opioid dose on postoperative ileus. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(7–8):916–923. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cali RL, Meade PG, Swanson MS, Freeman C. Effect of morphine and incision length on bowel function after colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(2):163–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02236975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oderda GM, Robinson SB, Gan TJ, Scranton R, Pepin J, Ramamoorthy S. Impact of postsurgical opioid use and ileus on economic outcomes in gastrointestinal surgeries; Abstract presented at: Annual Meeting of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; June 2–6, 2012; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramamoorthy S, Robinson SB. Impact of opioid-related adverse events (ORAE) on length of stay (LOS) and hospital costs in patients undergoing a laparoscopic colectomy; Abstract presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (in conjunction with Digestive Disease Week); May 18–22, 2012; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansfield SD, Jensen C, Phair AS, Kelly OT, Kelly SB. Complications of loop ileostomy closure: a retrospective cohort analysis of 123 patients. World J Surg. 2008;32(9):2101–2106. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9669-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser AM, Israelit S, Klaristenfeld D, et al. Morbidity of ostomy takedown. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(3):437–441. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha AK, Tapping CR, Foley GT, et al. Morbidity and mortality after closure of loop ileostomy. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(8):866–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joh YG, Lindsetmo RO, Stulberg J, Obias V, Champagne B, Delaney CP. Standardized postoperative pathway: accelerating recovery after ileostomy closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(12):1786–1789. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams LA, Sagar PM, Finan PJ, Burke D. The outcome of loop ileostomy closure: a prospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10(5):460–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, Seid VE, et al. Loop ileostomy morbidity: timing of closure matters. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(10):1539–1545. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0645-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phang PT, Hain JM, Perez-Ramirez JJ, Madoff RD, Gemlo BT. Techniques and complications of ileostomy takedown. Am J Surg. 1999;177(6):463–466. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann LJ, Stewart PJ, Goodwin RJ, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL. Complications following closure of loop ileostomy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991;61(7):493–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luglio G, Pendlimari R, Holubar SD, Cima RR, Nelson H. Loop ileostomy reversal after colon and rectal surgery: a single institutional 5-year experience in 944 patients. Arch Surg. 2011;146(10):1191–1196. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baraza W, Wild J, Barber W, Brown S. Postoperative management after loop ileostomy closure: are we keeping patients in hospital too long? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(1):51–55. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12518836439209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow A, Tilney HS, Paraskeva P, Jeyarajah S, Zacharakis E, Purkayastha S. The morbidity surrounding reversal of defunctioning ileostomies: a systematic review of 48 studies including 6,107 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(6):711–723. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Exparel® (bupivacaine liposome injectable suspension) [package insert] Parsippany, NJ: Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergese SD, Ramamoorthy S, Patou G, Bramlett K, Gorfine SR, Candiotti KA. Efficacy profile of liposome bupivacaine, a novel formulation of bupivacaine for postsurgical analgesia. J Pain Res. 2012;5:107–116. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S30861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viscusi ER, Sinatra R, Onel E, Ramamoorthy SL. The safety of liposome bupivacaine, a novel local analgesic formulation. Clin J Pain. 2013 Feb 26; doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318288e1f6. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dasta J, Ramamoorthy S, Patou G, Sinatra R. Bupivacaine liposome injectable suspension compared with bupivacaine HCl for the reduction of opioid burden in the postsurgical setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(10):1609–1615. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.721760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen SM. Extended pain relief trial utilizing infiltration of Exparel®, a long-acting multivesicular liposome formulation of bupivacaine: a Phase IV health economic trial in adult patients undergoing open colectomy. J Pain Res. 2012;5:567–572. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S38621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Conference on Harmonisation Working Group ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6 (R1); International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; June 10, 1996; Washington, DC. [Accessed April 19, 2012]. Available at: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6_R1/Step4/E6_R1__Guideline.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amlong CA, Schroeder KM, Andrei AC, Han S, Donnelly MJ. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane blocks in ileostomy takedowns: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24(5):373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baxter R, Bramlett K, Onel E, Daniels S. Impact of local administration of liposome bupivacaine for postsurgical analgesia on wound healing: a review of data from ten prospective, controlled clinical studies. Clin Ther. 2013;35(3):312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]