Abstract

Telomere shortening occurs during oxidative and inflammatory stress with guanine (G) as the major site of damage. In this work, a comprehensive profile of the sites of oxidation and structures of products observed from G-quadruplex and duplex structures of the human telomere sequence was studied in the G-quadruplex folds (hybrid (K+), basket (Na+), and propeller (K+ + 50% CH3CN)) resulting from the sequence 5’-(TAGGGT)4T-3’ and in an appropriate duplex containing one telomere repeat. Oxidations with four oxidant systems consisting of riboflavin photosensitization, carbonate radical generation, singlet oxygen, and the copper Fenton-like reaction were analyzed under conditions of low product conversion to determine relative reactivity. The one-electron oxidants damaged the 5’-G in G-quadruplexes leading to spiroiminodihydantoin (Sp) and 2,2,4-triamino-2H-oxazol-5-one (Z) as major products as well as 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (OG) and 5-guanidinohydantoin (Gh) in low relative yields, while oxidation in the duplex context produced damage at the 5’- and middle-Gs of GGG sequences and resulted in Gh being the major product. Addition of the reductant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to the reaction did not alter the riboflavin-mediated damage sites, but decreased Z by 2-fold and increased OG by 5-fold, while not altering the hydantoin ratio. However, NAC completely quenched the CO3•− reactions. Singlet oxygen oxidations of the G-quadruplex showed reactivity at all Gs on the exterior faces of G-quartets and furnished the product Sp, while no oxidation was observed in the duplex context under these conditions, and addition of NAC had no effect. Because a long telomere sequence would have higher-order structures of G-quadruplexes, studies were also conducted with 5’-(TAGGGT)8-T-3’, and it provided similar oxidation profiles to the single G-quadruplex. Lastly, CuII/H2O2-mediated oxidations were found to be indiscriminate in the damage patterns, and 5-carboxamido-5-formamido-2-iminohydantoin (2Ih) was found to be a major duplex product, while nearly equal yields of 2Ih and Sp were observed in G-quadruplex contexts. These findings indicate that the nature of the secondary structure of folded DNA greatly alters both the reactivity of G toward oxidative stress as well as the product outcome and suggest that recognition of damage in telomeric sequences by repair enzymes may be profoundly different from that of B-form duplex DNA.

Keywords: G-Quadruplex; DNA Damage; Telomere; 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine Spiroiminodihydantoin; Guanine Oxidation

INTRODUCTION

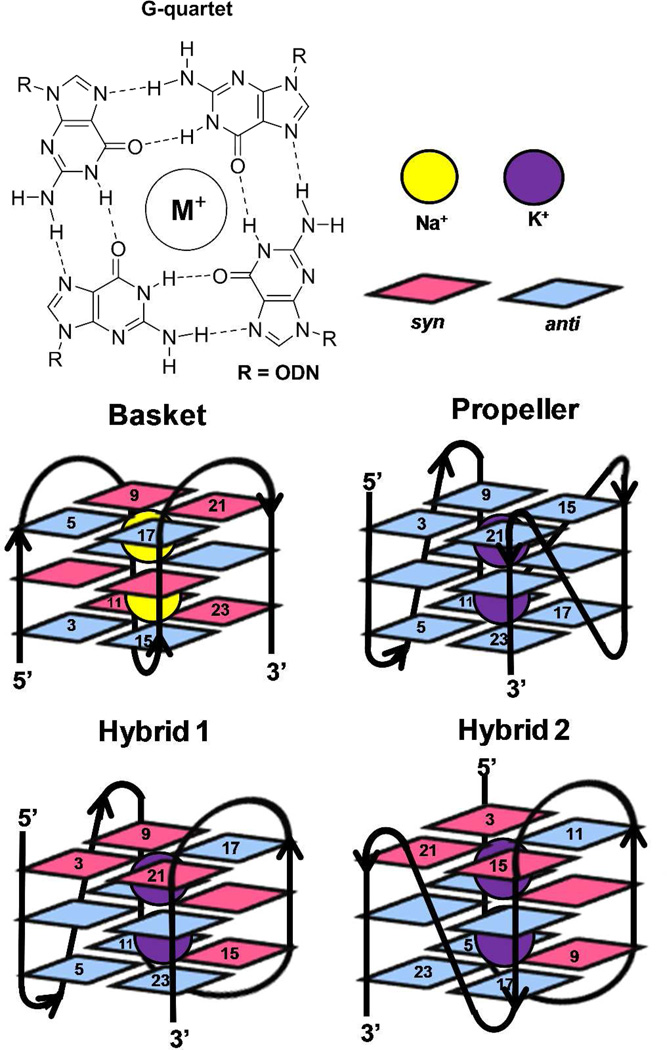

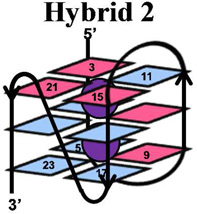

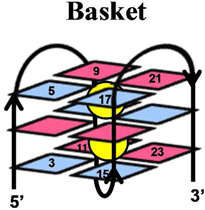

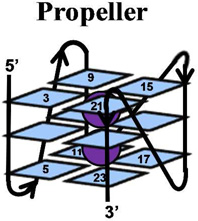

The telomere fold protects the chromosome ends from degradation and prevents repair enzymes from recognizing the chromosome ends as double-strand breaks.1 This region can be many kilobases long and is composed of the repeat sequence, 5’-(TTAGGG)n-3’.2 Within the telomere, roughly 5–15 kbps of the repeat sequence are paired with its complementary strand forming a DNA duplex, while the last 50–200 nucleotides are single stranded.3 The structure of the single-stranded overhang is the topic of current discussion in which one proposal suggests that this guanine-rich sequence folds into a unique secondary structure referred to as a G-quadruplex.4–6 Recent reports have detected G-quadruplexes in human cells, as well as shown that they respond to small molecules.7 DNA G-quadruplexes consist of a plane of four guanine (G) residues H-bonded through Hoogsteen base pairs forming a G-quartet (Figure 1), and these stack in the presence of a suitable alkali metal (Na+ and K+) forming the G-quadruplex (Figure 1).8, 9 Solution experiments conducted in NaCl revealed the basket-like structure that involves two edgewise loops and one diagonal loop (Figure 1),10 while KCl solution experiments identified two similar folding motifs referred to as hybrid 1 and hybrid 2 (Figure 1) that include two edgewise loops and one double-chain reversal loop.11–14 These two hybrid structures differ in the order of their loop orientations. In contrast, solid-state experiments, and those conducted with solutions bearing high concentrations of dehydrating solvents, have identified the propeller fold that contains all loops as double-chain reversals (Figure 1).15–17 Because the K+ (~140 mM) concentration is higher in cells than the Na+ (~10 mM) concentration,18 and G-quadruplexes have a stronger binding constant with K+, the hybrid folds are thought to dominate in vivo.9, 12 Furthermore, recent studies suggest the two hybrid folds allow stacking of adjacent G-quadruplexes into column-like geometries, providing clues to folding of the single-stranded region at the end of the telomere.19

Figure 1.

Structures of a G-quartet, and the basket, propeller, hybrid-1 and hybrid-2 folds of G-quadruplexes. Each G-quadruplex structure was drawn based on the solved structures reported in references 10–15. Potassium ions are shown with purple spheres, sodium ions are shown with yellow spheres, anti G residues are shown in blue and syn G residues are shown in magenta.

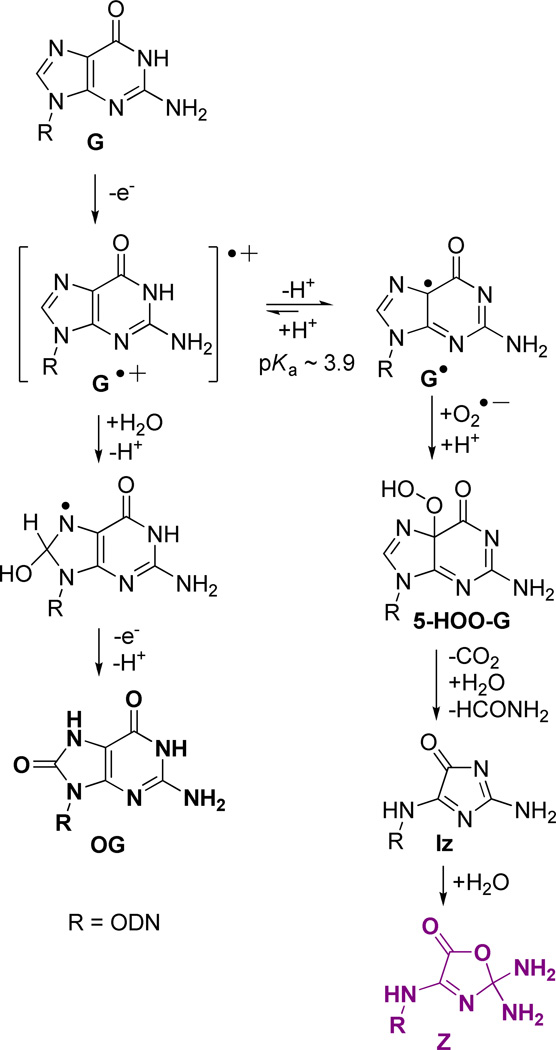

Telomere length is associated with cellular mortality with the overall length showing a correlation with age.20 Recently, studies have found that a decreasing telomere length is correlated to lifetime exposure to oxidative and inflammatory stress.21, 22 The chemical agents responsible for oxidative and inflammatory stress are electron-deficient species, chiefly H2O2, HO•, O2•−, 1O2, and ONOO−, all of which are established oxidants present in vivo.23 Within the genome, G is a dominant site for oxidatively-generated damage because this base has the lowest redox potential.24 Studies concerning G oxidation have provided a wealth of data that has generated the following major conclusions: Product formation is determined by initial reactions that occur at either the C5 or C8 position of guanine.25–29 Products of G nucleoside oxidation by ionizing radiation and Fenton chemistry (HO•) along the C5 pathway have been identified as 2,5-diaminoimidazolone (Iz) and its hydrolysis product 2,2,4-triamino-2H-oxazol-5-one (Z), among which Z has been observed in vivo (Scheme 1).30, 31 Recent studies have found 5-carboxamido-5-formamido-2-iminohydantoin (2Ih, Scheme 1), also a C5-pathway product, resulting from CuII or PbII plus H2O2, NiCR/HSO5, Mn-TMPyP/KHSO5, the epoxidizing agent dimethyldioxirane, and from CO3•− as the oxidant systems.25, 32–36 Along the C8 pathway, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (OG) and 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy•G) are major products found from ionizing radiation and Fenton chemistry in DNA.30 The yield of OG dominates under aerobic conditions while the Fapy•G yield increases under anaerobic conditions;37 both products have been observed in vivo (Scheme 1).27 Inflammatory stress generates •NO and O2•− that undergo a reaction cascade in bicarbonate buffer to yield CO3•− and •NO2.38 CO3•− is the more oxidizing radical, oxidizing G to initially give OG.39, 40 The summation of these experiments highlight OG as the major G oxidation product; consequently, OG is a common biomarker for oxidative stress. Currently, the concentration of OG in uncompromised cells is estimated at ~ 1 in 106 bases,41 and this figure increases under cellular stress.31, 42, 43

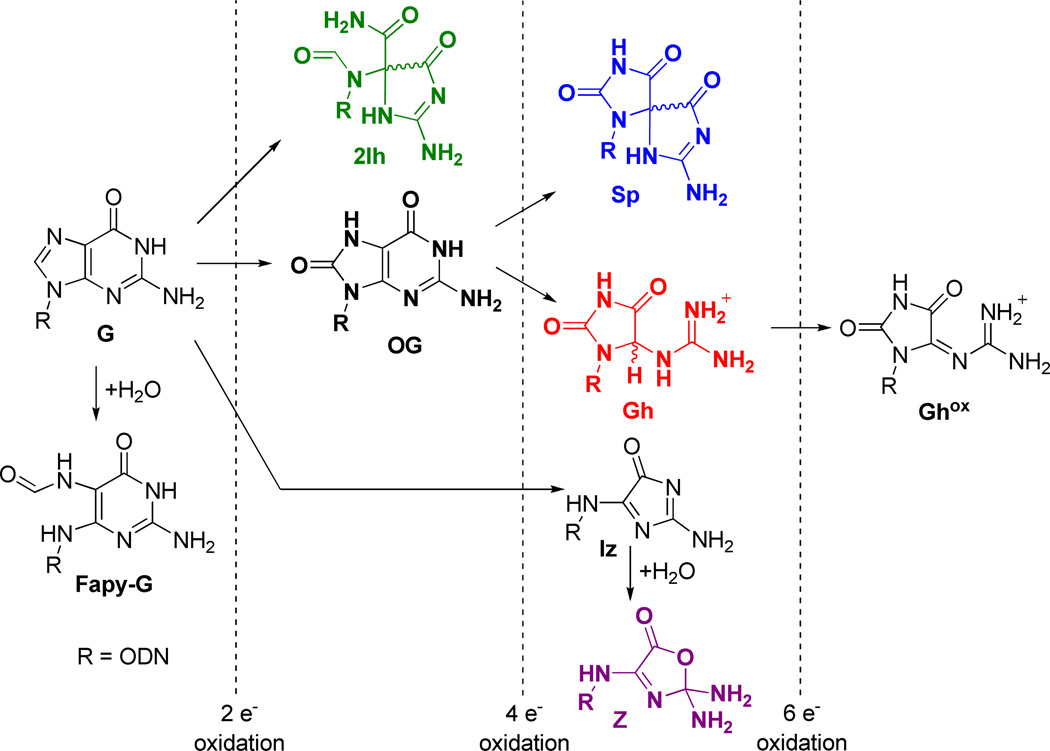

Scheme 1.

Extent of oxidation for products that arise from guanine plus reactive oxygen species.

OG is thermally and hydrolytically stable, but it has a significantly lower redox potential than G (~600 mV)44 and can therefore undergo a second oxidation leading to the hydantoin products spiroiminodihydantoin (Sp) and 5-guanidinohydantoin (Gh, Scheme 1). The hydantoins have been observed from many oxidation systems including CO3•−,40 •NO2,45, 46 transition-metal oxidants,47–50 HOCl,51 riboflavin photooxidation,52 and 1O2.53, 54 Furthermore, the yields of Sp and Gh are reaction context dependent; high pH and nucleoside contexts favor the more sterically demanding Sp, while low pH and oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) contexts favor Gh.55–58 Both Sp and Gh have been observed in vivo.59, 60 Taken together, these studies suggest two major G-oxidation manifolds exist: (1) C5 oxidation leading to Z and 2Ih, or (2) initial C8 oxidation yielding OG that can be further oxidized to Sp and Gh. Although Sp is stable toward additional oxidation reactions, Gh can be further oxidized to dehydroguanidinohydantoin (Ghox), which is formally a six-electron oxidation product of G.55, 61 Recent studies highlight C8 oxidation products accumulating in the liver in a mouse model of colon cancer.60

The human telomere sequence 5’-(TTAGGG)n-3’ is comprised of triple G sequences that are established hotspots for G oxidation, particularly with respect to one-electron oxidants.62–65 Previous studies have addressed electron-hole transfer between an adjacent duplex and G-quadruplex regions in ODNs with varying results, in which the reactivity depends on the choice of oxidant and the folded G-quadruplex conformation.66–69 Furthermore, the rate of G oxidation in a G-quadruplex is ~twofold faster than that observed for duplex G oxidation.70 In a subsequent set of studies, a cationic metalloporphyrin complex, Mn-TMPyP, was activated with KHSO5 when bound to the human telomere sequence, and damage was observed at the G nucleotides interacting with the metal complex.71 None of the previous studies reported the products of G oxidation in G-quadruplexes. However, OG has been observed during oxidation studies of riboflavin, SIN-1 (3-morpholinosydnonimine) or CuII/H2O2 with the human telomere sequence in the duplex context or a single-stranded context with low sodium ion concentrations; in these studies, though, the folded nature of the single strand was not evaluated.72, 73 Therefore, we elected to study comprehensively the G oxidation sites and products in the G-quadruplex that folds from the human telomere sequence, 5’-(TAGGGT)4T-3’. In these studies, Type I (e− transfer) and Type II (1O2) photochemical oxidants, as well as SIN-1/HCO3− generated CO3•−, and CuII/H2O2 were utilized to effect G oxidation. Because the human telomere also exists in the duplex context, a comparison was made to G oxidation using the sequence 5’-d(ATA TTA TTA GGG TTA TTA TTA)-3’ • 3’-d(TAT AAT AAT CCC AAT AAT AAT)-5’, which positions the GGG component of the human telomere sequence in an appropriate context for dsODNs. Cellular contexts are maintained in reducing environments with many reductants, particularly glutathione, and for that reason the oxidation sites and products were also compared when the glutathione mimic N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was added to the reaction solution.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All chemicals were obtained from commercially available sources and used without further purification. Oligodeoxynucleotides were synthesized by the DNA/Peptide synthesis core facility at the University of Utah following standard solid-phase synthetic protocols using commercially available phosphoramidites (Glen Research, Sterling, VA). Preparation and characterization of all ODN samples was achieved following standard protocols that are further elaborated in the Supporting Information.

Oxidation reactions

All oxidations were conducted in 20 mM MPi (pH 7.4) 120 mM MCl (M = Na or K) at 37 °C at a 10 µM ODN concentration. Oxidation sites were determined on reactions doped with 20,000 cpm of 5’-32P labeled strand in a 50-µL reaction utilizing the following oxidant conditions: (1) Riboflavin (Type I photooxidant) was added to give a 50 µM final concentration and solutions were exposed to 350-nm light for 5–20 min, (2) CO3•− was produced when SIN-1 generated ONOO− (<3 mM) was allowed to react with 25 mM MHCO3 (M = Na or K) present, and the reaction progressed through the thermal decomposition of SIN-1 for 0.5–3 h, (3) Rose Bengal (Type II photooxidant) was added to a final concentration of 50 µM and solutions were exposed to 350-nm light for 5–20 min, and (4) Cu-mediated oxidations were conducted with 10 µM Cu(OAc)2 that was preincubated with the ODNs for 30 min prior to the addition of 10–1000 µM H2O2, and allowed to react for 30 min prior to reaction termination with 5 mM EDTA. Following the oxidation, samples were dialyzed overnight then worked up with 1 M piperidine at 90 °C for 2 h, and then the piperidine was removed by lyophilization. Next, the samples were resuspended in 12 µL of loading buffer (30% glycerol, 0.25% bromophenol blue, and 0.25% xylene cyanol) and 6 µL was loaded on a 20% denaturing PAGE gel, and electrophoresed at 75 W for 2.5 h. A Maxam-Gilbert G-lane was run alongside each reaction to determine the G oxidation sites.74 The cleavage sites were observed and quantified by storage-phosphor autoradiography on a phosphorimager (see Supporting Information).

Oxidation products were determined by nuclease digestion followed by HPLC analysis. To achieve the analysis, reactions were conducted similarly to those described above with the exception of not adding the 5’-32P labeled strand. For each oxidant studied, 20 reactions were conducted and then combined to have 10 nmoles of oxidized ODN. Next, the samples were dialyzed overnight to remove the reaction buffer. Rose Bengal was removed with a NAP-25 column (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After concentrating the samples by lyophilization, they were resuspended in 50 µL of digestion buffer and digested with nuclease P1, snake venom phosphodiesterase and calf intestinal phosphatase, as previously described.32 Next, the products were quantified by HPLC following a previously described protocol32 for which the complete details of the entire process are described in the Supporting Information.

RESULTS

All studies reported herein were conducted with 10 µM ODNs in 20 mM MPi (pH 7.4) and 120 mM MCl (M = Na or K) at 37 °C. The duplex and G-quadruplex ODNs were characterized by CD spectroscopy and found to be consistent with those reported in the literature.75 All Tm melting values were >10 °C above the reaction temperature; furthermore, native gel electrophoresis led to shifts that differed from the ss- and dsODN controls (Supporting Information). Next, the duplex and G-quadruplex contexts were oxidized and the sites of G oxidation were determined by hot piperidine workup that led to strand breaks at the oxidation sites, and were visualized by gel electrophoresis and storage phosphor autoradiography. The OG lesion is the least labile to piperdine workup while the other lesions (Sp, Gh, and Z) have varying degrees of lability toward strand scission.76 To minimize the systematic error, post oxidation OG was further driven to Sp and Gh with K2IrBr6 following a previously described method from our laboratory,76 and the cleavage reactions were conducted with 1 M piperidine for 2 h at 90 °C; we and others have previously shown that these reaction conditions greatly enhance strand scission at the Sp, Gh and Z damaged sites.58, 77 Next, the oxidation products were determined by exhaustive nuclease digestion followed by HPLC analysis utilizing a method previously described by our laboratory.32 For each context studied, oxidation sites and products were determined under low conversion reaction conditions; dsODN reactions were conducted at <20% conversion to product, and G-quadruplex reactions were conducted at <12% conversion to product, due to the high percentage of Gs. Triplicate trials were conducted to obtain suitable error bars.

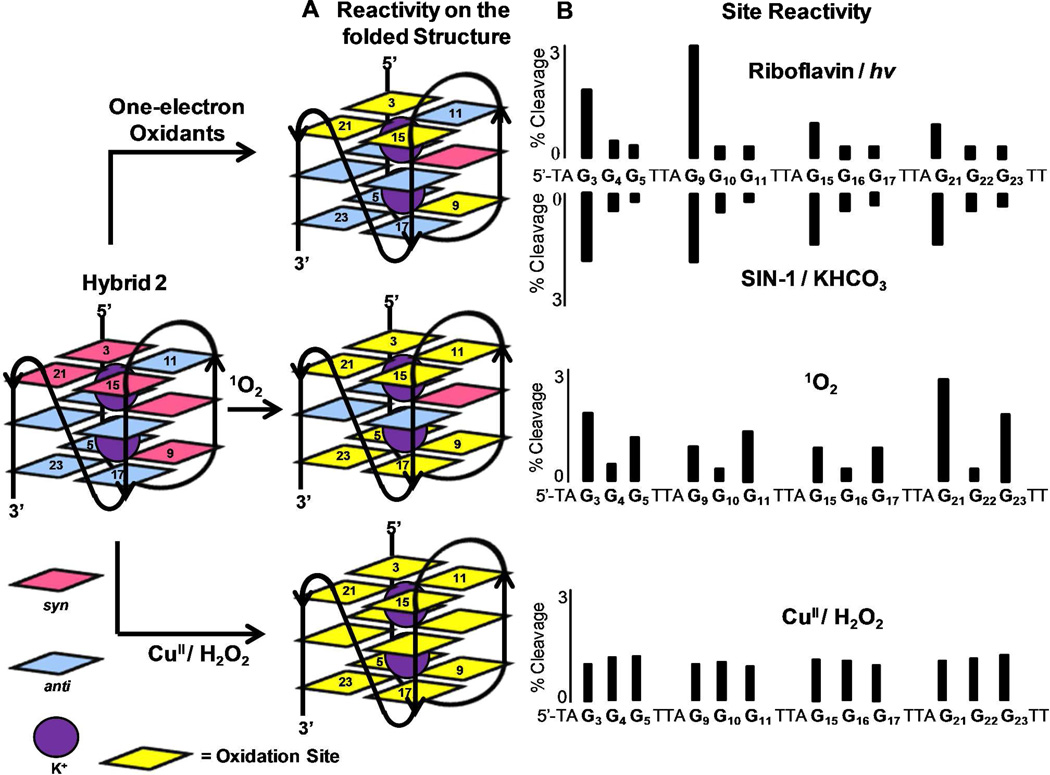

Oxidations in the 5’-(TAGGGT)4T-3’ oligomer folded into the hybrid (KCl solution), basket (NaCl solution), or propeller (KCl solution + 50% CH3CN) G-quadruplexes were studied. The sites for G reactivity in the hybrid-2 fold are compared with the one-electron oxidants (riboflavin/hν and SIN-1/HCO3− generated CO3•−), 1O2, and CuII/H2O2 (Figure 2). . Reaction sites for the one-electron oxidants riboflavin and CO3•− were predominantly observed on the 5’-Gs (G3, G9, G15, and G21). In comparison, 1O2-mediated oxidations showed nearly equal reactivity at all Gs in the exterior quartets (G3 & G5, G9 & G11, G15 & G17, G21 & G23; Figure 2). Thirdly, the hybrid G-quadruplex was oxidized with CuII/H2O2 for which no site selectivity was observed post piperidine workup. Furthermore, a minor amount of frank strand breaks was observed in the copper Fenton-like reaction without piperidine treatment, indicative of sugar oxidation. The hybrid folds resulting from the human telomere sequence are notoriously polymorphic in solution depending on the number and identity of 5’ and 3’ terminal nucleotides, and this may have influenced the results; therefore, we elected to study also the sequence 5’-TTGGG(TTAGGG)3A-3’ that is less dynamic in solution.78 However, repeating the above experiments with the new sequence provided similar results (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Sites of oxidation in the G-quadruplex context of the human telomere sequence. For brevity, results from only the hybrid 2 conformation are shown; all others appear in the Supporting Information. Oxidations were conducted with one-electron oxidants (riboflavin/hν and SIN-1/KHCO3), 1O2, and CuII/H2O2. (A) Represents the G reactivity on the folded structure, and (B) displays the absolute G reactivity. The reaction sites were determined by hot piperidine cleavage followed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Total reaction yield for the G-quadruplex context was held below 12%.

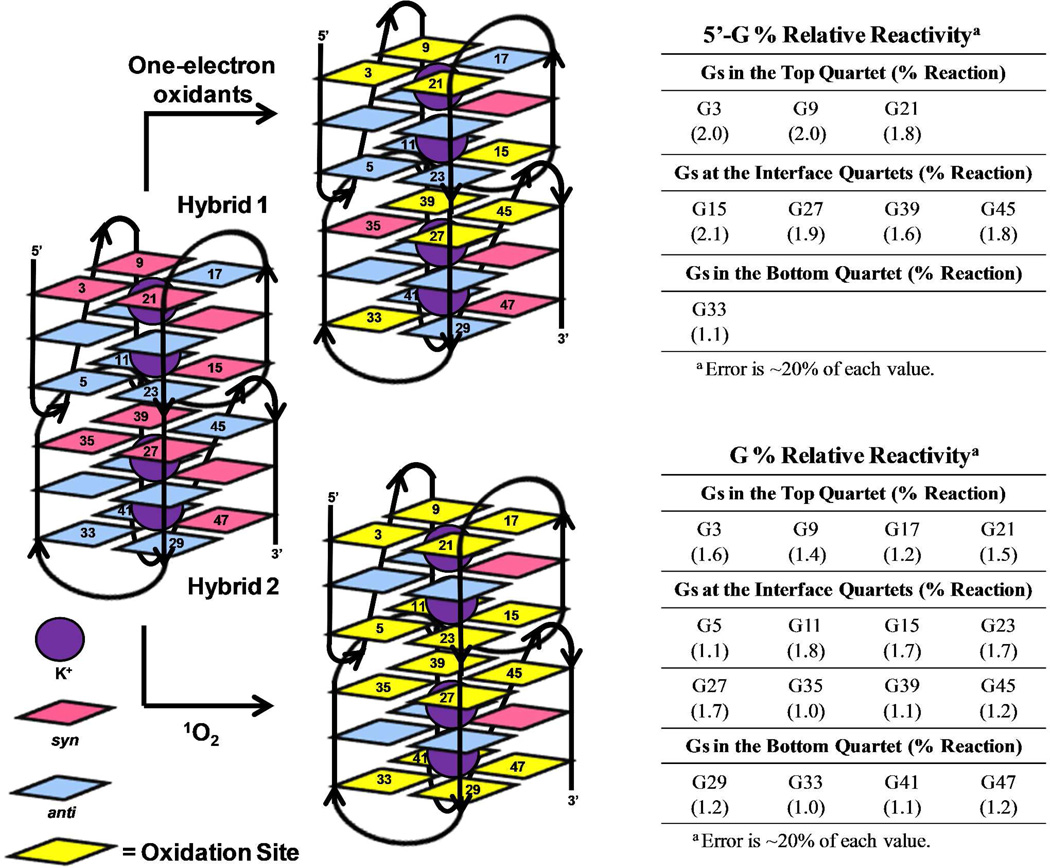

Because the single-stranded region of the full length human telomere is 50–200 nucleotides long, it could fold to give many G-quadruplexes stacked on one another. Previous studies from the Chaires laboratory have proposed that two stacked G-quadruplexes in KCl solution would alternate between the hybrid-1 and hybrid-2 folds;19, 79 therefore, oxidations with the sequence 5’-(TAGGGT)8T-3’ were conducted that has two adjacent G-quadruplexes. Studies performed with the one-electron oxidants riboflavin/hν and SIN-1/KHCO3 led to base damage at all 5’-Gs of each GGG sequence (Figure 3). Oxidations conducted with 1O2 damaged the outer G-quartets of each individual G-quadruplex, similarly to the studies above with single G-quadruplexes (Figure 3). From these studies, there do not appear to be any differences observed in single vs. double G-quadruplexes in terms of their site reactivity toward oxidation. Thus, we conclude that the interface between two adjacent G-quadruplexes is not structured in such a way that would confer protection of G from oxidatively-generated damage or enhance the reactivity.

Figure 3.

Sites of oxidation observed in higher order G-quadruplex structures in KCl solution. Oxidations were conducted with one-electron oxidants (riboflavin/hν and SIN-1/KHCO3) and 1O2. The reaction sites were determined by hot piperidine cleavage followed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Total reaction yields for the G-quadruplex context were held below 20%.

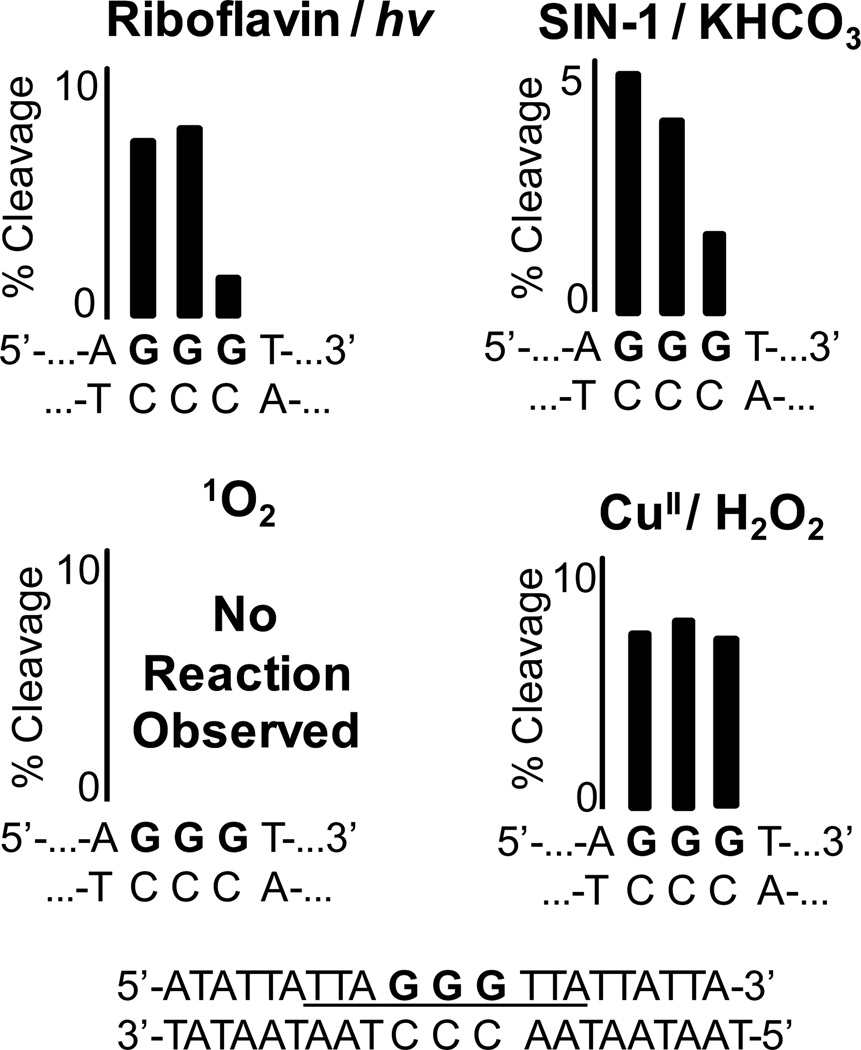

In contrast to the quadruplex structures, oxidation of the duplex telomere sequence with these oxidants led to different sites of reactivity. The one-electron oxidants gave nearly an equal amount of oxidation at the 5’- and middle-G nucleotides of the GGG sequence (Figure 4). Next, when the duplex-telomere sequence was exposed to 1O2, no strand scission was observed under the conditions used for G-quadruplex oxidation (Figure 4). Previous reports utilizing methylene blue as a source of 1O2 found G oxidation to OG in dsODNs. Because OG nucleotides are not labile to hot piperidine,76 we were concerned that our analytical method might not permit visualization of oxidation on a gel. Therefore, after oxidation of the dsODN with 1O2, the strands were further oxidized with K2IrBr6 to drive OG oxidation to Sp or Gh, both of which are piperidine labile.57, 76 These control reactions did not show increased strand scission (Supporting Information). Lastly, dsODN oxidations with CuII/H2O2 showed reactivity at all G nucleotides, as expected (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sites of oxidation in the duplex context of the human telomere sequence. Oxidations were conducted with one-electron oxidants (riboflavin + hν or SIN-1/KHCO3), 1O2, and CuII/H2O. The reaction sites were determined by hot piperidine cleavage followed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Total reaction yields for the duplex context were held below 20%.

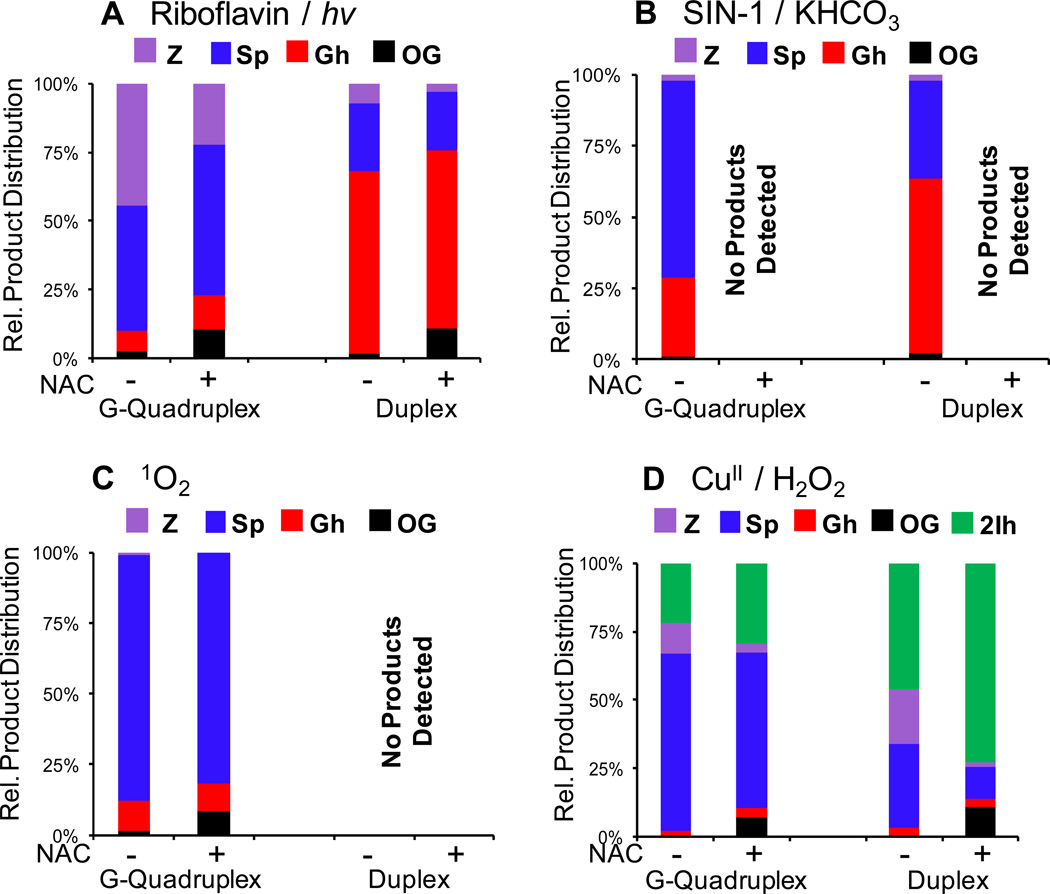

Riboflavin-mediated oxidation of the G-quadruplex yielded the products Z, OG, Sp and Gh in which Z (~45%) and Sp (~45%) were the two major products observed (Figure 5A; errors are ~8% of each value). In contrast, oxidation of the telomere sequence in the dsODN context also gave Z, OG, Sp and Gh, but the major product was Gh (~66%; Figure 5A). Oxidation of a G-quadruplex by CO3−• (generated by SIN-1/KHCO3) also yielded the products Z, OG, Sp and Gh with the major product being Sp (~69%), while the relative yield of Gh was lower (~27%), and <5% Z and OG were observed (Figure 5B). The dsODN oxidation product distribution included all four compounds and Gh was the major product (~66%), followed by Sp (~34%; Figure 5B). In all oxidations conducted with the SIN-1/HCO3− oxidant system, two reactive radicals are generated, CO3•− and •NO2, and all products identified are consistent with CO3•− and •NO2-mediated oxidations, and not with •NO2 radical coupling reactions. No nitroimidazole products were observed, consistent with previous reports.80 Rose Bengal photochemically activates 3O2 to 1O2 that readily oxidized the G-quadruplex contexts. The product distribution included Z, OG, Sp and Gh, with Sp (~87%) being the major product, and the remaining mass balance was predominantly comprised of Gh (~11%) and trace amounts of Z and OG (Figure 5C). No products were observed when the dsODN context was oxidized with Rose Bengal under the same reaction conditions (Figure 5C). Lastly, CuII/H2O2 oxidation of the hybrid G-quadruplex gave Sp (~50%) as the major product with a significant amount of 2Ih (~30%), and the remaining mass balance was comprised of Z, OG, and Gh (Figure 5D), while dsODNs gave somewhat more 2Ih (37%) than Sp (25%, Figure 5D), with the remaining mass balance comprised of Gh, Z and OG. In both contexts the base release observed from sugar oxidation was monitored and was <10% in the quadruplex oxidations, which was predominantly observed at the 3’-G of each GGG sequence, and ~20% in the duplex studies that appears to be stochastic in nature (Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

The context-dependent oxidation product distributions monitored with and without added NAC as reductant. The oxidant systems utilized were (A) riboflavin/hν, (B) CO3•− (SIN-1/KHCO3), (C) 1O2 (Rose Bengal), (D) CuII/H2O2. Products were determined post oxidation by nuclease digestion of the ODNs followed by HPLC analysis. Product quantification was achieved by integration of the peak areas that were normalized through their respective extinction coefficients at 240 nm, which allowed direct comparison of each peak area. Errors are estimated at ~8% of each value reported.

A comparison of the G-quadruplex folds (i.e., hybrid, basket, and propeller) in terms of oxidation sites and product structures was also conducted (Table 1). The basket fold was formed in NaCl solutions and exhibited a similar CD spectral shape to that reported in the literature (Supporting Information).75 The propeller quadruplex was formed by the addition of 50% CH3CN following previous methods that gave the same CD spectral shape as literature reports.17, 75 In the propeller context studies, the reaction progressed on a similar timeframe as for the basket and hybrid studies (determined by gel electrophoresis), therefore, the added CH3CN does not appear to dramatically affect the reaction course. One-electron oxidants (riboflavin/hν and CO3•−) in all three contexts predominantly damaged the 5’-G nucleotides of each GGG run; subtle differences in the extent of damage exist between the folded contexts, but nothing striking was observed (Supporting Information). Moreover, the product distributions observed across the contexts were similar. During the course of 1O2-mediated oxidations the same site reactivity and products were observed across the three quadruplex conformations studied. Lastly, with Cu-mediated oxidations, the sites of reaction and products were not affected by the quadruplex context. The key observations from these studies are that reactivity sites in G-quadruplex structures is not influenced by folding topology, but the coordinated cation (K+ or Na+) diminished reactivity on the middle quartet. Last, the product distribution in G-quadruplexes is not highly dependent on the folding topology. The glycosidic bond orientation of the G nucleotides (syn vs. anti) does not influence the reactivity with the oxidants studied. Studies that utilized one-electron oxidants always damaged the most 5’-G, and 1O2 always damaged the exterior G nucleotides, and CuII-H2O2 oxidations were indiscriminate in their selection of reaction site.

Table 1.

Comparison of G-quadruplex fold effects on reaction sites and products.

|

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidant | Sites of Reactivity |

Major Products (%)a |

Sites of Reactivity |

Major Products (%)a |

Sites of Reactivity |

Major Products (%)a |

| Riboflavin + hν | 5’G Nucleotides | Sp (45) Z (44) | 5’G Nucleotides | Sp (43) Z (52) | 5’G Nucleotides | Sp (42) Z (48) |

| CO3•− (SIN-1 + HCO3−) | 5’-G Nucleotides | Sp (63) Gh (36) | 5’-G Nucleotides | Sp (72) Gh (23) | 5’-G Nucleotides | Sp (74) Gh (21) |

| 1O2 | Exterior Quartets | Sp (72) | Exterior Quartets | Sp (87) | Exterior Quartets | Sp (89) |

| CuII/H2O2/NAC | All G Nucleotides | Sp (59) 2Ih (27) | All G Nucleotides | Sp (53) 2Ih (30) | All G Nucleotides | Sp (57) 2Ih (25) |

Errors are estimated at ~8% of each value reported.

All previous oxidation studies were then repeated in the presence of 2 mM NAC to mimic the reducing environment of the cell. The added reductant did not have an effect on the oxidation sites (Supporting Information), although to obtain the same amount of strand scission, reactions had to be run for twice as long for the riboflavin and 1O2 reactions. The SIN-1/KHCO3 oxidations were completely quenched; therefore, oxidation sites and products were not determined. Finally, the NAC enhanced the oxidatively-generated damage associated with CuII/H2O2, as expected, by facilitating the formation of CuI.58 While the sites of reaction were not affected by the presence of reductant, the product outcome was. In the riboflavin-mediated oxidations, the presence of NAC decreased the yield of Z by ~two-fold in both the G-quadruplex and the duplex contexts (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the amount of OG observed in each context increased by ~five-fold (Figure 5A). When the G-quadruplex contexts were subjected to 1O2-mediated oxidation in the presence of NAC, the OG yield increased by ~six-fold while the Sp and Gh yields slightly decreased (Figure 5C). Lastly, the presence of NAC during Cu-mediated oxidations decreased the Z yield and increased the OG yield in the G-quadruplex context (Figure 5D), while increasing the 2Ih yield in the duplex context, as expected (Figure 5D).58

DISCUSSION

These studies highlight two main differences observed for G oxidation in the duplex and G-quadruplex folds of the human telomere sequence with respect to sites of reactivity and product distributions. (1) One-electron oxidants, such as riboflavin and CO3•−, predominately damage the 5’-Gs in G-quadruplexes, however, both the 5’ and middle-G nucleotides are reactive in duplexes containing a 5’-GGG-3’ sequence; 1O2 oxidation did not lead to observable chemistry in duplex contexts, while oxidizing all Gs in the two exterior G-quartets of the G-quadruplexes studied, and CuII/H2O2 effects oxidation at all Gs in both duplex and G-quadruplex contexts (Figures 2 and 4). (2) Product distributions between the two contexts showed many contrasts with respect to the major product(s) observed in which Sp was the major G-quadruplex oxidation product with all oxidants studied, while in duplex contexts the product distribution was oxidant specific, though the hydantoin products typically dominated and Gh was formed to a much greater extent than Sp (Figure 5A–D).

The context dependency in G oxidation observed in this work is best reasoned chemically by the following proposed mechanisms. One-electron oxidants initiate G oxidation following the pathway outlined in Scheme 1 in which the initial electron-deficient species is a radical cation (G•+).26, 29, 81 G•+ is acidic (N1 proton pKa ~3.9) and rapidly deprotonates to the neutral radical (G•) in nucleoside reactions conducted at neutral pH.82 G• couples with O2•− at C5 to yield 5-HOO-G that decomposes to furnish Iz, and then slowly hydrates to yield Z.83 The production of O2•− occurs through the deactivation of excited state riboflavin by O2; additionally, it is one of the decomposition products of SIN-1 under aerobic reaction conditions.83, 84 A high yield of Z was observed with riboflavin-mediated oxidations, consistent with other studies.85, 86 The acid-base chemistry of G•+ is modulated in the duplex context because the acidic proton is one of the Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds to C; therefore, this proton is trapped within the H-bonds altering the reaction course of G.81, 82, 87 Subsequently, H2O can add at C8, and loss of another electron occurs to give OG as a product under aerobic conditions, or alternatively, reduction can occur under anaerobic conditions to give Fapy•G. Our data are consistent with previous studies that observed OG as an oxidation product, because the reactions were all conducted under aerobic conditions (Figure 5).30, 37 To account for OG in the G-quadruplex studies, a parallel is drawn between a G•C Watson-Crick base pair and a G•G Hoogsteen base pair. In both base pairs, the N1 proton of G is hydrogen bonded to either N3 of C in the Watson-Crick base pair, or to O6 of G in the G-quartet. We hypothesize that trapping of the N1 base-paired proton will also occur in the G-quadruplex, and the G oxidation intermediate will favor the C8 reaction channel to OG, which was observed. This observation is consistent with previous reports (Figure 5);72, 73 moreover, OG is prone to further oxidation to yield the hydantoins, Sp and Gh.

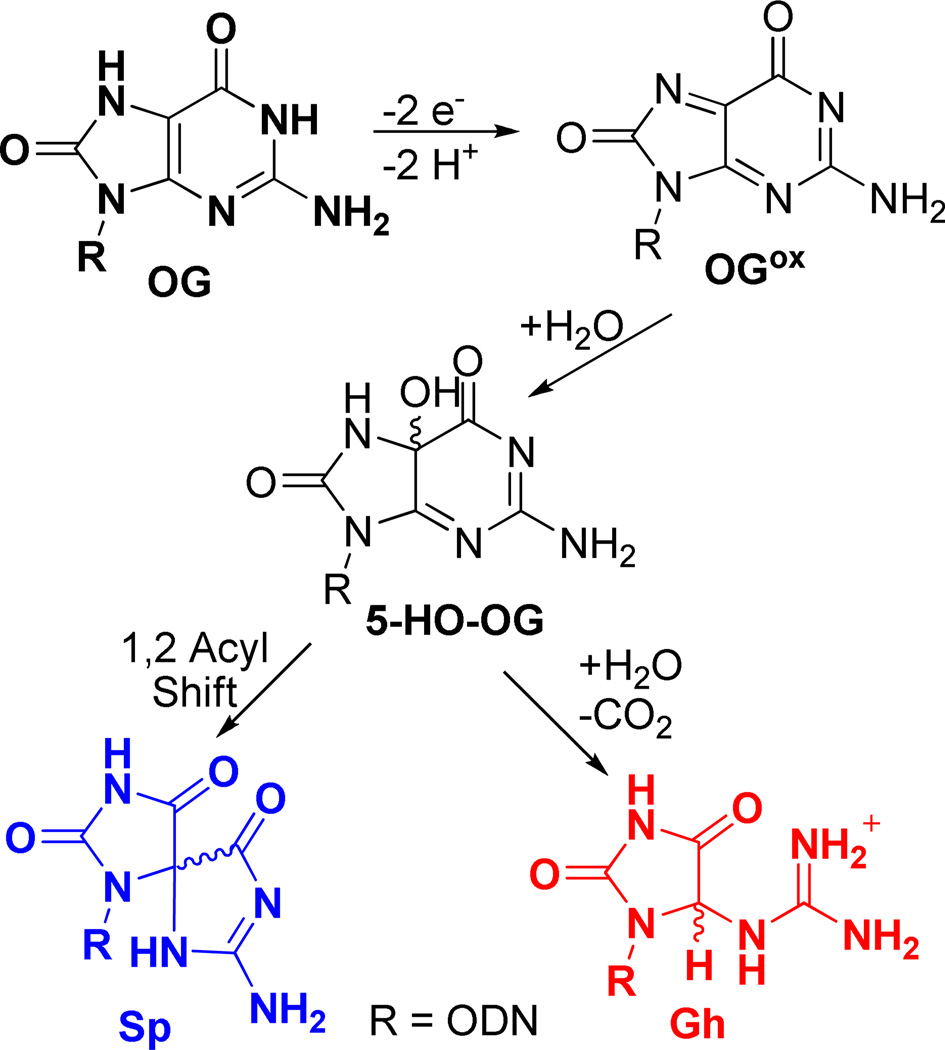

As shown in Scheme 3, the further oxidation of OG by one-electron oxidants ultimately yields the electrophilic intermediate OGox that adds H2O at C5 to yield 5-HO-OG.53 This species partitions to Sp and Gh in a pH and context dependent fashion.48, 52, 55, 56, 58 Our previous studies have shown that sterics, electrostatics, and base pairing in the duplex context combine to drive 5-HO-OG down the Gh pathway, in other words, Gh ≫ Sp.58 Consistent with this observation, Gh was the major product observed in the duplex context under riboflavin photooxidation conditions, and its yield increased under conditions generating CO3•− as oxidant (Figure 5). In contrast, a G in the exterior quartet of a G-quadruplex is in a less sterically demanding context, and the bound cation (K+ or Na+, Figure 1) can mitigate the electrostatic effect; thus, the yields in the G-quadruplex oxidation showed Sp ≫ Gh (Figure 5). Another reaction channel for OG in the presence of O2•− ultimately yields Ghox (Scheme 1) that has limited stability, and decomposes with two intermediate products (parabanic acid and oxaluric acid) that ultimately ends in formation of a urea lesion.61, 88 Our assay can detect the oxaluric acid and urea lesions; however, in our current reactions we have not detected significant amounts of these products (<5% yield), consistent with other reports.80

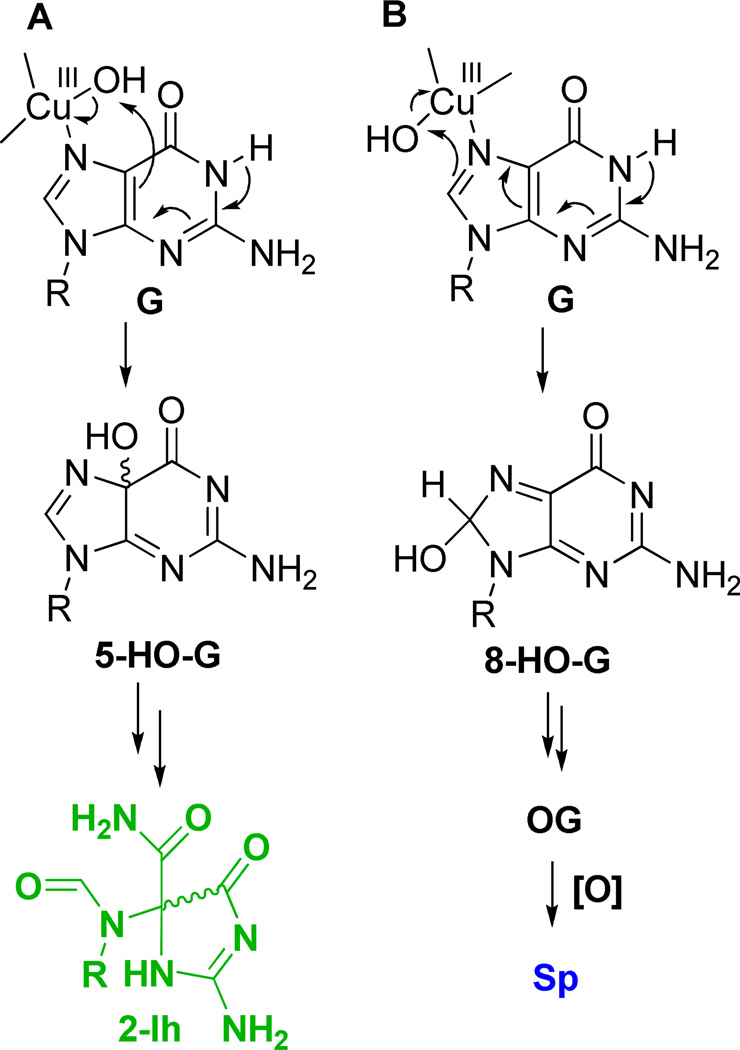

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for oxidation of OG to the hydantoins, Sp and Gh.

The context-dependent site of G oxidation is also best understood from G-oxidation intermediates. One-electron oxidants led to high product yields at the 5’-Gs in G-quadruplexes, while damaging the 5’-G and middle-G nucleotides in dsODNs where these two Gs were observed to react in nearly equal amounts. The initial G oxidation product is a radical cation for which the electron hole migrates in the dsODN context to a reactive G nucleotide that is determined by both thermodynamics and kinetics; Saito and others showed that a G that is 5’ to another purine, specifically another G, is most reactive because it has the lowest ionization potential,62 and Schuster has proposed that the 5’-G has the smallest kinetic barrier for reaction.89 Accordingly, in the duplex telomere sequence, oxidation was observed at the 5’-G and central Gs (Figure 3), consistent with previous observations.62–65, 89 In contrast, G oxidation in the G-quadruplex only occurs on the 5’-Gs (Figures 2 and 3). We propose that the presence of the monovalent cations (K+ or Na+, Figure 1) in the interior of the quadruplex channel diminishes radical cation formation on the middle G due to electrostatic repulsion; hence, very little oxidation occurs at the middle G in the 5’-GGG-3’ sequence context. Our data are fully consistent with the Barton and Schuster laboratories who previously demonstrated that hybrid G-quadruplex oxidation sites, via electron transfer from an intervening duplex, show reactivity at only the 5’-Gs.66, 67 Furthermore, the Thorp laboratory has demonstrated that diffusible oxidants show a preference for damaging only the 5’-G in hybrid quadruplexes.70 In summary, G oxidation by one-electron oxidants provides a pattern of damage that is context specific, in which the duplex context yields damage at both 5’-Gs while the G-quadruplex folds lead to damage at only the initial 5’-G (Figures 2–4) of each GGG sequence. Overall, Sp was the major G-quadruplex product and Gh was the major duplex oxidation product, highlighting another key difference between these two structures.

Culminations of many reported studies have identified the four main G-oxidation products as OG, Sp, Gh, and Z, and the ratios of these products have been quantified by many laboratories. However, the values reported here and elsewhere do not completely reconcile with one another. Therefore, we feel it prudent to point out some of the key differences between these bodies of work. The typical method for quantification of these products requires first digesting the ODN or DNA sample to nucleosides and quantifying them by HPLC coupled to either a mass spectrometer or photodiode array detector, both of which require comparison of standards of known concentrations to establish detector responses. There are two sets of extinction coefficients for these species in the literature: (1) Those used by the Tannenbaum and Dedon laboratories (Z: ε232 = 9,000; Sp ε230 = 10,500; Gh ε230 = 3,000 M−1 cm−1),61 and (2) those used by our laboratory (Z: ε240 = 1,778;31 Sp ε240 = 3,275;47 Gh ε240 = 2,412 M−1cm−1).32, 55 An important note is that the Gh extinction coefficient has been shown previously by our laboratory to be pH dependent.55 Because the hydantoins can be made in very high yield (>95%) from OG utilizing Na2IrCl6 as the oxidant under the appropriate reaction conditions,58 we conducted a simple HPLC-based assay to reevaluate the ε ratio for Sp and Gh under our present assay conditions (0.1% acetic acid), and we were able to reconfirm the relative ratio of the Sp and Gh values used here (Supporting Information). Comparison of our Sp:Gh ε240 ratio (1.35) to other reported values (ratio = 3.5) indicates a significant difference in quantification methods. In addition, the OG and Z ε values for each of our laboratories are relatively consistent when compared to Sp. A better method is to monitor site-specific oxidations in an ODN that can be directly quantified, and this also has been done by all three laboratories.33, 58, 61 Even here, we observe discrepancies in the reported Sp:Gh product distributions in dsDNA, though each of these studies has used slightly different oxidant systems and ODNs with variable sequences and from different sources. As it currently stands, the reported values are inconsistent, with the Sp:Gh ratio in dsDNA observed to be ~ 1:2 in our laboratory (Figure 5) but nearly the reverse in other reported studies.80 We await more comparative studies to elucidate the underlying chemical rationale for these differences.

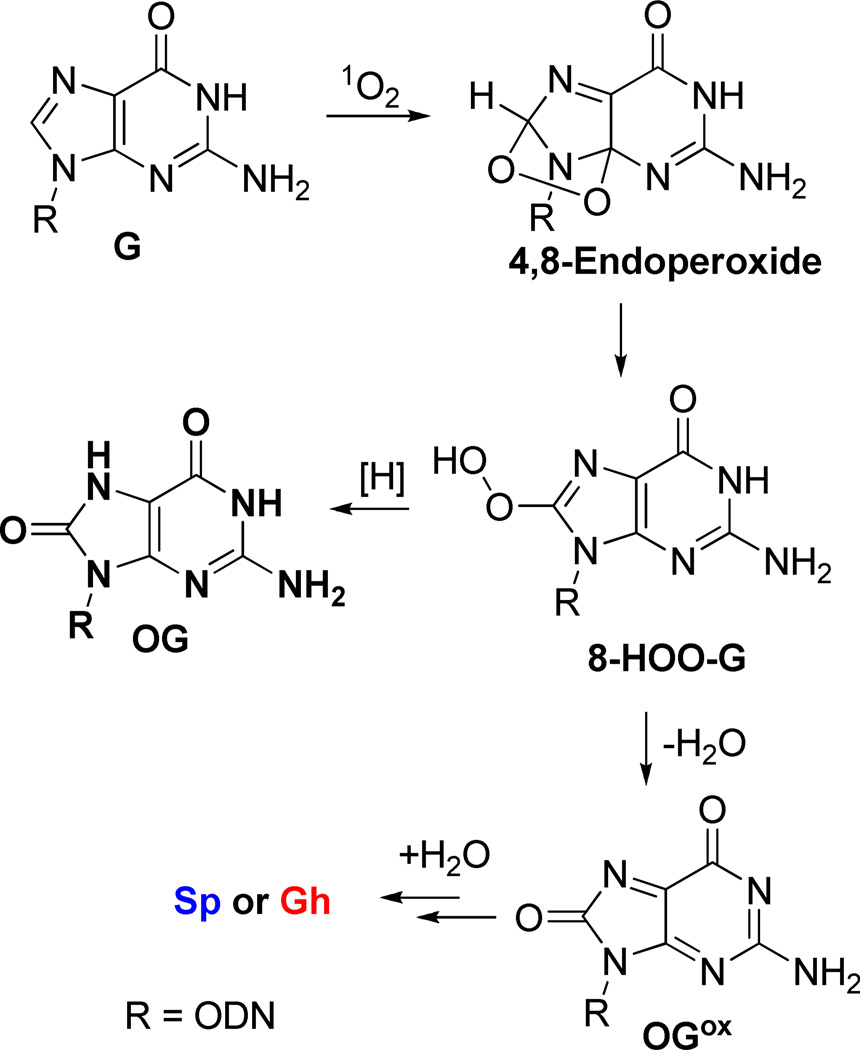

Guanine oxidation mediated by 1O2 is proposed to occur by the cycloaddition mechanism outlined in Scheme 4 by 1O2 addition in a [4+2] manner across the imidazole ring, generating a 4,8-endoperoxide intermediate that rearranges to produce 8-HOO-G.27 8-HOO-G can be reduced to OG,25, 90 or dehydrate to the quininoid-like species, OGox, and as previously described, OGox adds H2O at C5 leading to the hydantoins Sp and Gh (Scheme 3).53 Within the duplex sequence, the G bases are π-stacked, inhibiting the cycloaddition of 1O2 to the face of the purine. Consequently, G oxidation in the dsODN context was not detected under reaction conditions that showed high reactivity for the G-quadruplex context (Figures 2–4). dsODNs oxidized by 1O2 have previously been shown to yield OG, and in order to test this possibility post reaction, K2IrBr6 was added to further drive OG oxidation to the piperidine-labile products Sp and Gh.76 However, no increase in strand scission was observed. Previously our laboratory has shown that 1O2-mediated damage is mitigated in the dsODN context, which is consistent with our current observations.65 In contrast, Gs in the G-quadruplex context readily reacted with 1O2 (Figure 2), an observation that is best explained by solvent exposure of the first and third G quartet layers. Lastly, G oxidation by 1O2 mediates the four-electron oxidation of G to hydantoins, and Sp ≫ Gh was observed in G-quadruplex oxidations due to the ability of the exterior Gs to rearrange to the sterically demanding but thermodynamically preferred spirocyclic structure (Figure 5). Interestingly, the G-oxidation pattern observed for 1O2 is so context specific between duplex and quadruplex folds that this difference in reactivity might serve as a probe of secondary structure.

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanism for 1O2 oxidation of G to OG and OGox. See Scheme 3 for the transformation of OGox to Sp and Gh.

Intracellular environments are reducing in nature with glutathione at low mM concentrations.91 Based on this fact, we asked how G oxidation is affected by reducing reaction conditions. Because the active reducing agent in glutathione is the free thiol of cysteine, we chose N-acetylcysteine (NAC) as a close mimic for our studies. Protection of the amino terminus is advantageous because it prevents complications that would arise from the primary amine acting as a nucleophile toward intermediates in the oxidation of G.92 Accordingly, we can study how the free thiol influences G oxidation product distributions. The addition of 2 mM NAC to all reactions with dsODN or G-quadruplexes did not alter the sites of oxidation by riboflavin-, 1O2- or Cu-mediated oxidations, although it did completely quench the SIN-1/HCO3 − mediated oxidation reactions (Supporting Information). The reaction yield versus time of oxidant exposure decreased by ~2-fold with the addition of NAC to the riboflavin- and 1O2-mediated oxidations of quadruplexes. In these reductant-dependent studies, the timing of G oxidation was initially unknown, that is, did damage occur after NAC was consumed, or was NAC still present when G was initially oxidized? To address this question, Ellman’s-free thiol test was conducted to determine the concentration of unreacted NAC during the reaction course.93 Using this analysis, we found that at the time products were determined, ~0.8–1 mM free thiol (NAC) remained in both the riboflavin- and 1O2-mediated oxidations (Supporting Information). In the riboflavin reaction, NAC affected the product distribution by a ~2-fold reduction in the yield of Z (Figure 5A), which was expected because NAC quenches superoxide,94 a reaction partner of G• that ultimately yields Z (Scheme 2). Moreover, a ~5-fold increase in the yield of OG was observed (Figure 5A). This observation is interpreted to suggest either a reaction intermediate is sensitive toward reduction and yields OG, or that NAC quenched the further oxidation of OG.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanisms for the oxidation of G initiated by one-electron oxidants.

In the 1O2-mediated oxidation, the addition of NAC increased the OG yield by ~6-fold with a compensatory decrease in the Sp and Gh yields (Figure 5B). 1O2 oxidation of G yields 8-HOO-G, an intermediate that would be sensitive to reduction yielding OG (Scheme 4); otherwise, dehydration of the peroxide intermediate would occur to yield OGox that further reacts to provide Sp and Gh (Scheme 3).53, 90 The intermediate 8-HOO-G has previously been proposed to be reduced to OG before further reacting to give Sp,25, 90 and the data reported herein support the proposed mechanism, because the OG yield increased with added NAC.

Finally, in the CuII/H2O2 reaction, all G nucleotides were oxidized. We note that N7 of G coordinates to CuII that has previously been shown to denature G-quadruplexes.95 This observation explains why Cu-catalyzed oxidations were indiscriminate in the G oxidation pattern (Figure 2). In these reactions, Sp was the major product (~50%), and 2Ih was observed in high yield (~30%), with the remaining mass balance comprised of Gh and Z in low yields (Figure 5D). In our previous studies, Cu-mediated oxidations were shown to give 2Ih in high yield due to coordination with G (Scheme 5);32 however, in the present reactions the Sp yield was greater. This observation may result from the fact that equal molar amounts of CuII and ODN were mixed together causing each CuII ion to be coordinated with more than one G nucleotide, thus the coordination environment altered the initial oxidation site to favor a pathway leading to Sp (Scheme 5). Interestingly, the frank strand breaks resulting from 2-deoxyribose oxidation showed a preference for damage at the 3’-G. A similar observation for sitespecific ribose oxidation has previously been described by the Meunier laboratory during oxidations of G-quadruplexes with Mn-TMPyP/KHSO5 oxidant systems.71 Lastly, the addition of NAC to the Cu-mediated oxidations greatly enhanced the observed damage, as previously described.32

Scheme 5.

Proposed CuII-mediated oxidation of G at C5 (A) or C8 (B).

In the present work, Sp was always the major G oxidation product observed in the G-quadruplex structural context of the human telomere sequence, while the duplex context for this sequence gave a major product that was oxidant dependent (Figure 5). Our previous studies concerning OG oxidation in the duplex have shown that Gh is the major product as a consequence of base stacking and electrostatics that favor the Gh pathway.58 In contrast, the exterior quartets of the G-quadruplex are less sterically restricted by base stacking, and the bound cation alters the reaction course, as evidenced by the change in reaction sites, and these combine to increase the Sp yield (Figure 5). In the current duplex studies, G is oxidized by CO3•− to give a Gh:Sp product ratio of about 2:1 (Figure 5), whereas previous work in our laboratory and others showed that OG in a very similar sequence contexts leads to a 19:1 ratio of Gh:Sp.56, 58, 76 This discrepancy points to a further nuance in trying to understand reaction pathways in genomic DNA; CO3•− may initially react with G by an inner-sphere electron transfer mechanism while its reaction with OG has been debated as both outer and inner sphere;40, 96 furthermore, in dsODNs the site reactivity has been associated with base pair opening rates,97 in which the OG•C base pair is slightly more dynamic than a G•C base pair.98

With respect to telomere oxidation in vivo, recent observations have quantified more G oxidation to OG (2- to 4-fold) within the human telomere than in a control region of the chromosome containing an equal amount of G.99, 100 Because the cellular context is reducing, our product distribution results obtained in the presence of NAC support OG as the major product under the low-oxidant flux that would be found in cellular contexts. Also of interest is a study showing that repair of OG in the human telomere by OGG1 is diminished due to the secondary structure of the human telomere. Faulty repair would increase the OG load within the telomere.100 These observations suggest that OG would accumulate to a higher concentration in the telomere than the rest of the chromosome. The Thorp laboratory has shown that the rate of OG oxidation within a G-quadruplex is ~2-fold faster than the rate observed in the duplex context.101 Collectively, these observations point to higher levels of OG formation and further oxidation occurring in the G-quadruplex context compared to the duplex context of the telomere, and our current results predict that the major OG oxidation product would be Sp (Figure 5). These observations might help explain recent reports from the Tannenbaum and Dedon laboratories concerning hydantoin concentrations in vivo.60

Recently the hydantoins Sp and Gh were quantified in a mouse model of chronic inflammation for which researchers found that the Sp and Gh yields were similar, and that Sp showed a dose response, while Gh did not.60 Taking into account previous reports of more OG in the telomere,99, 100 and the propensity for Sp as the major product in the G-quadruplex context, it is appealing to propose that the higher amount of Sp observed in the mouse studies are biased by high levels of telomeric DNA damage to the folded quadruplex regions. Furthermore, if repair of Sp by the Neil glycosylases is inhibited in the telomere,102–104 as has been observed for OG,100 then the Sp load, specifically in the telomere, would increase significantly as observed in the mouse studies.60 Moreover, oxidative and inflammatory stress have been correlated with telomere shortening21, 22 and persistent DNA damage response,105 that when coupled with our current data, suggest that OG and its oxidation product Sp should be looked upon closely as causative DNA-damage elements for these phenomena.

The pattern of G damage shows a strong dependence on the reactive oxygen species present. Inflammation liberates ONOO− that oxidizes G through a complex pathway in which CO3•− is a major one-electron oxidant that imposes the damage. Based on the present results, the G-quadruplex context would show damage at only the 5’-G nucleotides, while in the duplex context, damage would be observed at both of the first two Gs of a GGG sequence (Figures 2–4). These observations are compared to the reactivity of single-strand contexts that have previously been shown to react without a strong preference to contextual factors as in duplex and G-quadruplex Gs.106 With respect to 1O2-mediated damage, the external G-quartets of a G-quadruplex would readily react, i.e. the 5’ and 3’ Gs of each GGG sequence, while the duplex context is expected to show limited reactivity;65 again, single-stranded Gs do not show a strong contextual reaction influence like those in duplexes and G-quadruplexes.107 These structural context studies address how damage can occur at the 3’-G of a G run that is not predicted by electron-transfer studies or those using one-electron oxidants.62–64, 66, 67 Finally, with respect to CuII/H2O2-mediated damage, the pattern is indiscriminant in its location in both duplex and G-quadruplex contexts (Figures 2–4), consistent with its ability both to bind to N7 of G and to increase 2-deoxyribose oxidation, which has also been verified in single-stranded contexts.32

Taking into account these studies and previous reports, a picture is painted to suggest the locations and products that would be observed from G oxidation “hotspots” in a chromosome. Most chromosomal DNA is found intimately wrapped around the nucleosomes for compaction and protection of the DNA. Consequently, electron-deficient species can initiate oxidation at one site and the damage can migrate long distances to a suitable 5’-GG-3’ or 5’-GGG-3’ with the oxidation terminating on a 5’-G or middle G of a purine triplet that is positioned distally from the nucleosome core.108–110 Moreover, this process is gated in an ion-dependent fashion by the intervening A•T base pairs between the reactive G sites.111 The G oxidation products observed from damage via electron transfer are either OG or Z in which Z is detected when O2•− is present. The quenching of superoxide by cellular antioxidants permits the OG reaction manifold to dominate in vivo (Figure 5).109, 112 The mutation profile observed for OG is to cause G→T transversion mutations; however, if Z is present it would stall strand elongation.113, 114 Indeed, G→T transversion mutations are a commonly observed somatic cancer cell mutation.115 It is well established that OG is prone to further oxidation yielding the pair of hydantoin compounds Sp and Gh, with Gh being the major product observed in the duplex context.56, 58, 76 The hydantoins give rise to both G→T and G→C transversion mutations,116 which are observed in lung and breast cancers; however, these mutations do not occur primarily at GG and GGG sequences as expected.117 Our current set of data, in conjunction with previous work from our laboratory and others on various motifs,58, 118 show that solvent exposure is a key factor in both reactivity patterns and product outcome. Accordingly, we expect that hotspots for oxidation in genomic DNA may reflect alternative folds in addition to simple sequence effects. Further support for this hypothesis comes from solvent effects on G damage sites in DNA toroids,119 and the observed increased reactivity of G toward oxidation with an adjacent abasic site.118 These observations provide an additional parameter to consider beyond the sequence-dependent ionization potential for G61, 110 in elucidating its oxidation pattern in the genome.

Bioinformatics studies have proposed that nearly 400,000 potential G-quadruplexes reside within the chromosome, and they show a higher probability of being located in gene promoter regions.120 The folding patterns of some of these promoter G-quadruplex structures have been studied, for example, the c-MYC and VEGF genes.121 Additionally it has been reported that promoters bearing G-quadruplex forming sequences appear to show enhanced sensitivity toward oxidation.122 Moreover, G-quadruplex forming sequences show a significant enrichment of DNA breakpoints associated with somatic copy-number alterations that characterize many cancer types,123 and damaged G-quadruplexes in promoter regions have been shown to give new structures that could lead to altered gene expression.124 Interestingly, quadruplex forming sequences show a bias toward being conserved within promoter regions of yeast, suggesting decreased damage or adequate repair, while G-quadruplexes found outside the promoter region are “hotspots” for double-strand breaks and chromosomal rearrangements.125 These observations taken in their entirety suggest that oxidative damage to G-quadruplex forming sequences might provide a chemical explanation for these types of chromosomal defects (i.e., breakpoints and rearrangements). The studies outlined herein lay the groundwork for understanding and predicting the sites that these chromosomal anomalies might occur, as well as the culprit G-oxidation products. Because these promoter G-quadruplexes have a diverse array of structures that would likely influence the G reactivity, it is anticipated these structures will alter the reactivity sites, parallel to the results described here. The future of G-quadruplex oxidation studies may provide some missing insight into the counterintuitive site specificity of G mutation sites, and the associated conundrum of understanding the frequency with which these elusive products are formed in mammals.

CONCLUSIONS

In the current body of work, oxidatively-damaged G sites and products were assessed in the duplex and G-quadruplex contexts of the human telomere sequence 5’-(TTAGGG)n-3’ utilizing four oxidants. These studies highlight contrasts in both the sites of G oxidation and the final products formed when the two contexts were compared. For example, the sites observed with the one-electron oxidants, riboflavin/hν and CO3•− were located at the 5’- and middle-G nucleotides of the GGG sequence in the duplex context, but only at the 5’-G in the G-quadruplex context. We propose a mechanistic explanation for the observed context differences in which the G•+ is stabilized on the 5’ and middle-G of the duplex, similarly to previous studies (Figure 4);62–64 however, the alkali cations in the G-quadruplex channel disfavor G•+ formation at the central G. Thus, oxidation occurred only at the 5’-G (Figures 2 and 4) in the folded quadruplexes. The product distributions for the riboflavin-mediated reaction differed such that duplex contexts gave a high yield of Gh, and the G-quadruplex context gave Z and Sp in nearly equal yield (Figure 5A). The presence of the reductant NAC did not significantly affect the duplex products while decreasing the overall Z yield in the G-quadruplex context. When CO3•− was the oxidant, Sp was the major G-quadruplex product, and Gh was the major duplex product (Figure 5B). The addition of NAC completely quenched these reactions. 1O2-mediated oxidations did not show reaction with the duplex context (Figure 4); however, the G-quadruplex context was highly reactive (Figure 2) with 1O2 leading to Sp as the major product with and without NAC present (Figure 5C). Lastly, CuII/H2O2-mediated oxidations did not show a preference in the oxidation sites (Figures 2 and 4), and the product ratios highlight the formation of 2Ih in the duplex context, but both Sp and 2Ih in the G-quadruplex context (Figure 5D). Moreover, these data have been instructive in proposing testable hypotheses for addressing G-mutation profiles, which will be better understood with next-generation sequencing applications. These product distribution studies help shed light on why the yield of Sp relative to Gh is higher than expected in mammalian cells.60

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge thoughtful discussions with Dr. James Muller (University of Utah). This work was supported by the NIH (CA090689).

ABBREVIATIONS

- 2Ih

5-carboxamido-5-formamido-2-iminohydantoin

- 5-OH-OG

5-hydroxy-8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine

- dsODN

double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide

- Fapy•G

2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine

- Gh

5-guanidinohydantoin

- Ghox

dehydroguanidinohydantoin

- Iz

2,5-diaminoimidazolone

- O and OG

8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SIN-1

3-morpholinosydnonimine

- Sp

spiroiminodihydantoin

- ssODN

single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide

- Tm

melting temperature

- Z

2,2,4-triamino-2H-oxazol-5-one

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION. HPLC, CD, Tm, piperidine cleavage studies for the propeller fold and NAC studies, Ellman’s free thiol test, Na2IrCl6, and G-quadruplex structures. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Sullivan RJ, Karlseder J. Telomeres: protecting chromosomes against genome instability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:171–181. doi: 10.1038/nrm2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyzis RK, Buckingham JM, Cram LS, Dani M, Deaven LL, Jones MD, Meyne J, Ratliff RL, Wu JR. A highly conserved repetitive DNA sequence, (TTAGGG)n, present at the telomeres of human chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:6622–6626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verdun RE, Karlseder J. Replication and protection of telomeres. Nature. 2007;447:924–931. doi: 10.1038/nature05976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lange T. How telomeres solve the end-protection problem. Science. 2009;326:948–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1170633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paeschke K, Simonsson T, Postberg J, Rhodes D, Lipps HJ. Telomere end-bonding proteins control the formation of G-quadruplex DNA structures in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nsmb982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paeschke K, Juranek S, Simonsson T, Hempel A, Rhodes D, Lipps HJ. Telomerase recruitment by the telomere end binding protein-[beta] facilitates G-quadruplex DNA unfolding in ciliates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:598–604. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biffi G, Tannahill D, McCafferty J, Balasubramanian S. Quantitiative visualization of DNA G-quadruplex structures in human cells. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:182–186. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel DJ, Phan AT, Kuryavyi V. Human telomere, oncogenic promoter and 5'-UTR G-quadruplexes: diverse higher order DNA and RNA targets for cancer therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7429–7455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane AN, Chaires JB, Gray RD, Trent JO. Stability and kinetics of G-quadruplex structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5482–5515. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the human telomeric repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] G-tetraplex. Structure. 1993;1:263–282. doi: 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Luu KN, Patel DJ. Structure of two intramolecular G-quadruplexes formed by natural human telomere sequences in K+ solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6517–6525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrus A, Chen D, Dai J, Bialis T, Jones RA, Yang D. Human telomeric sequence forms a hybrid-type intramolecular G-quadruplex structure with mixed parallel/antiparallel strands in potassium solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2723–2735. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Noguchi Y, Sugiyama H. The new models of the human telomere d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] in K+ solution. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:5584–5591. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phan AT, Luu KN, Patel DJ. Different loop arrangements of intramolecular human telomeric (3+1) G-quadruplexes in K+ solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5715–5719. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkinson GN, Lee MPH, Neidle S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature. 2002;417:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MC, Buscaglia R, Chaires JB, Lane AN, Trent JO. Hydration Is a major determinant of the G-quadruplex stability and conformation of the human telomere 3'-sequence of d(AG3(TTAG3)3) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17105–17107. doi: 10.1021/ja105259m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heddi B, Phan AT. Structure of human telomeric DNA in crowded solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9824–9833. doi: 10.1021/ja200786q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang D, Okamoto K. Structural insights into G-quadruplexes: towards new anticancer drugs. Future Med. Chem. 2010;2:619–646. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petraccone L, Spink C, Trent JO, Garbett NC, Mekmaysy CS, Giancola C, Chaires JB. Structure and stability of higher-order human telomeric quadruplexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20951–20961. doi: 10.1021/ja209192a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samassekou O, Gadji M, Drouin R, Yan J. Sizing the ends: Normal length of human telomeres. Ann. Anat. 2010;192:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, Cawthon RM. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Su Y, Reus VI, Rosser R, Burke HM, Kupferman E, Compagnone M, Nelson JC, Blackburn EH. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: Correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress - preliminary findings. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Tian X, Shin I, Yoon J. Fluorescent and luminescent probes for detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4783–4804. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15037e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. How easily oxidizable is DNA? One-electron reduction potentials of adenosine and guanosine radicals in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratviel G, Meunier B. Guanine oxidation: one- and two-electron reactions. Chemistry. 2006;12:6018–6030. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat J-L. Oxidatively generated damage to the guanine moiety of DNA: Mechanistic aspects and formation in cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1075–1083. doi: 10.1021/ar700245e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat J-L. Oxidatively generated base damage to cellular DNA. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2010;49:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaney S, Jarem DA, Volle CB, Yennie CJ. Chemical and biological consequences of oxidatively damaged guanine in DNA. Free Radical Res. 2012;46:420–441. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.653968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gimisis T, Cismas C. Isolation, characterization, and independent synthesis of guanine oxidation products. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006;2006:1351–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angelov D, Spassky A, Berger M, Cadet J. High-intensity UV laser photolysis of DNA and purine 2'-deoxyribonucleosides: Formation of 8-oxopurine damage and oligonucleotide strand cleavage as revealed by HPLC and gel electrophoresis studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11373–11380. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matter B, Malejka-Giganti D, Csallany AS, Tretyakova N. Quantitative analysis of the oxidative DNA lesion, 2,2-diamino-4-(2-deoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone (oxazolone), in vitro and in vivo by isotope dilution-capillary HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5449–5460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleming AM, Muller JG, Ji I, Burrows CJ. Characterization of 2'-deoxyguanosine oxidation products observed in the Fenton-like system Cu(II)/H2O2/reductant in nucleoside and oligodeoxynucleotide contexts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:3338–3348. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05112a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rokhlenko Y, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Lifetimes and reaction pathways of guanine radical cations and neutral guanine radicals in an oligonucleotide in aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4955–4962. doi: 10.1021/ja212186w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banu L, Blagojevic V, Bohme DK. Lead(II)-catalyzed oxidation of guanine in solution studied with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:11791–11797. doi: 10.1021/jp302720z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye W, Sangaiah R, Degen DE, Gold A, Jayaraj K, Koshlap KM, Boysen G, Williams J, Tomer KB, Mocanu V, Dicheva N, Parker CE, Schaaper RM, Ball LM. Iminohydantoin lesion induced in DNA by peracids and other epoxidizing oxidants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6114–6123. doi: 10.1021/ja8090752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghude P, Schallenberger MA, Fleming AM, Muller JG, Burrows CJ. Comparison of transition metal-mediated oxidation reactions of guanine in nucleoside and single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide contexts. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2011;369:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2010.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenberg MM. The formamidopyrimidines: Purine lesions formed in competition with 8-oxopurines from oxidative stress. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:588–597. doi: 10.1021/ar2002182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lonkar P, Dedon PC. Reactive species and DNA damage in chronic inflammation: reconciling chemical mechanisms and biological fates. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;128:1999–2009. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennedy LJ, Moore K, Caulfield JL, Tannenbaum SR, Dedon PC. Quantitation of 8-oxoguanine and strand breaks produced by four oxidizing agents. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:386–392. doi: 10.1021/tx960102w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Oxidation of Guanine and 8-oxo-7,8-Dihydroguanine by Carbonate Radical Anions: Insight from Oxygen-18 Labeling Experiments. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:5057–5060. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gedik CM, Collins A. Establishing the background level of base oxidation in human lymphocyte DNA: results of an interlaboratory validation study. FASEB J.; ESCODD (European Standard Committee on Oxidative DNA Damage) 2005;19:82–84. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1767fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mangal D, Vudathala D, Park J-H, Lee SH, Penning TM, Blair IA. Analysis of 7,8-Dihydro-8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine in cellular DNA during oxidative stress. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009;22:788–797. doi: 10.1021/tx800343c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mesaros C, Arora JS, Wholer A, Vachani A, Blair IA. 8-Oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine as a biomarker of tobacco smoking-induced oxidative stress. Free Radical Biol. Med., ASAP. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV, Bietti M, Bernhard K. The trap depth (in DNA) of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'deoxyguanosine as derived from electron-transfer equilibria in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2373–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shafirovich V, Cadet J, Gasparutto D, Dourandin A, Geacintov NE. Nitrogen dioxide as an oxidizing agent of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine but not of 2'-deoxyguanosine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:233–241. doi: 10.1021/tx000204t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Misiaszek R, Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Combination of nitrogen dioxide radicals with 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and guanine radicals in DNA: Oxidation and nitration end-products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2191–2200. doi: 10.1021/ja044390r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo W, Muller JG, Rachlin EM, Burrows CJ. Characterization of spiroiminodihydantoin as a product of one-electron oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine. Org. Lett. 2000;2:613–616. doi: 10.1021/ol9913643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niles JC, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Spiroiminodihydantoin and guanidinohydantoin are the dominant products of 8-oxoguanosine oxidation at low fluxes of peroxynitrite: Mechanistic studies with 18O. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004;17:1510–1519. doi: 10.1021/tx0400048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugden KD, Campo CK, Martin BD. Direct oxidation of guanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine in DNA by a high-valent chromium complex: A possible mechanism for chromate genotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:1315–1322. doi: 10.1021/tx010088+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vialas C, Claparols C, Pratviel G, Meunier B. Guanine oxidation in double-stranded DNA by Mn-TMPyP/KHSO5: 5,8-Dihydroxy-7,8-dihydroguanine residue as a key precursor of imidazolone and parabanic acid derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2157–2167. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki T, Masuda M, Friesen MD, Ohshima H. Formation of spiroiminodihydantoin nucleoside by reaction of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine with hypochlorous acid or a myeloperoxidase-H2O2-Cl− system. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:1163–1169. doi: 10.1021/tx010024z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo W, Muller JG, Burrows CJ. The pH-dependent role of superoxide in riboflavin-catalyzed photooxidation of 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2801–2804. doi: 10.1021/ol0161763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye Y, Muller JG, Luo W, Mayne CL, Shallop AJ, Jones RA, Burrows CJ. Formation of 13C-15N-, and 18O-labeled guanidinohydantoin from guanosine oxidation with singlet oxygen. Implications for structure and mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13926–13927. doi: 10.1021/ja0378660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCallum JEB, Kuniyoshi CY, Foote CS. Characterization of 5-hydroxy-8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine in the photosensitized sxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine and its rearrangement to spiroiminodihydantoin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16777–16782. doi: 10.1021/ja030678p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo W, Muller JG, Rachlin EM, Burrows CJ. Characterization of hydantoin products from one-electron oxidation of 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine in a nucleoside model. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:927–938. doi: 10.1021/tx010072j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gremaud JN, Martin BD, Sugden KD. Influence of substrate complexity on the diastereoselective formation of spiroiminodihydantoin and guanidinohydantoin from chromate oxidation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;23:379–385. doi: 10.1021/tx900362r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duarte V, Muller J, Burrows C. Insertion of dGMP and dAMP during in vitro DNA synthesis opposite an oxidized form of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:496–502. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fleming AM, Muller JG, Dlouhy AC, Burrows CJ. Context effects in the oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine to hydantoin products: Electrostatics, base stacking, and base pairing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15091–15102. doi: 10.1021/ja306077b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hailer MK, Slade PG, Martin BD, Sugden KD. Nei deficient Escherichia coli are sensitive to chromate and accumulate the oxidized guanine lesion spiroiminodihydantoin. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:1378–1383. doi: 10.1021/tx0501379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mangerich A, Knutson CG, Parry NM, Muthupalani S, Ye W, Prestwich E, Cui L, McFaline JL, Mobley M, Ge Z, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Wogan GN, Fox JG, Tannenbaum SR, Dedon PC. Infection-induced colitis in mice causes dynamic and tissue-specific changes in stress response and DNA damage leading to colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:E1820–E1829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207829109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim KS, Cui L, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Chan W, DeMott MS, Babu IR, Tannenbaum SR, Dedon PC. In situ analysis of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine oxidation reveals sequence- and agent-specific damage spectra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:18053–18064. doi: 10.1021/ja307525h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugiyama H, Saito I. Theoretical studies of GG-specific photocleavage of DNA via electron transfer: Significant lowering of ionization potential and localization of HOMO of stacked GG bases in B-form DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:7063–7068. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hall DB, Barton JK. Sensitivity of DNA-mediated electron transfer to the intervening π-stack: A probe for the integrity of the DNA base stack. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5045–5046. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Breslin DT, Schuster GB. Anthraquinone photonucleases: Mechanisms for GG-selective and nonselective cleavage of double-stranded DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2311–2319. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hickerson RP, Prat F, Muller JG, Foote CS, Burrows CJ. Sequence and stacking dependence of 8-oxoguanine oxidation: Comparison of one-electron vs singlet oxygen mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9423–9428. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delaney S, Barton JK. Charge transport in DNA duplex/quadruplex conjugates. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14159–14165. doi: 10.1021/bi0351965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ndlebe T, Schuster GB. Long-distance radical cation transport in DNA: horizontal charge hopping in a dimeric quadruplex. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:4015–4021. doi: 10.1039/b610159c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang YC, Cheng AKH, Yu H-Z, Sen D. Charge conduction properties of a parallel-stranded DNA G-quadruplex: Implications for chromosomal oxidative damage. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6794–6804. doi: 10.1021/bi9007484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pothukuchy A, Mazzitelli CL, Rodriguez ML, Tuesuwan B, Salazar M, Brodbelt JS, Kerwin SM. Duplex and quadruplex DNA binding and photocleavage by trioxatriangulenium ion. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2163–2172. doi: 10.1021/bi0485981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Szalai VA, Thorp HH. Electron transfer in tetrads: Adjacent guanines are not hole traps in G quartets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4524–4525. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vialas C, Pratviel G, Meunier B. Oxidative damage generated by an oxo-metalloporphyrin onto the human telomeric sequence. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9514–9522. doi: 10.1021/bi000743x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oikawa S, Tada-Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Site-specific DNA damage at the GGG sequence by UVA involves acceleration of telomere shortening. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4763–4768. doi: 10.1021/bi002721g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Site-specific DNA damage at GGG sequence by oxidative stress may accelerate telomere shortening. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:365–368. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00748-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maxam AM, Gilbert W. A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1977;74:560–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karsisiotis AI, Hessari NMa, Novellino E, Spada GP, Randazzo A, Webba da Silva M. Topological characterization of nucleic acid G-quadruplexes by UV absorption and circular dichroism. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:10645–10648. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muller JG, Duarte V, Hickerson RP, Burrows CJ. Gel electrophoretic detection of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine via oxidation by IRIV) Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2247–2249. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tretyakova NY, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Peroxynitrite-induced secondary oxidative lesions at guanine nucleobases: Chemical stability and recognition by the Fpg DNA repair enzyme. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:658–664. doi: 10.1021/tx000083x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Luu KN, Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Lacroix L, Patel DJ. Structure of the human telomere in K+ solution: An intramolecular (3 + 1) G-quadruplex scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9963–9970. doi: 10.1021/ja062791w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Petraccone L, Trent JO, Chaires JB. The tail of the telomere. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16530–16532. doi: 10.1021/ja8075567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cui L, Ye W, Prestwich E, Wishnok JS, Taghizadeh K, Dedon PC, Tannenbaum SR. Comparative analysis of four oxidized guanine lesions from reactions of DNA with peroxynitrite, singlet oxygen and γ-radiation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013;26:195–202. doi: 10.1021/tx300294d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burrows CJ, Muller JG. Oxidative nucleobase modifications leading to strand scission. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1109–1152. doi: 10.1021/cr960421s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Steenken S. Purine bases, nucleosides, and nucleotides: aqueous solution redox chemistry and transformation reactions of their radical cations and e− and OH adducts. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:503–520. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Misiaszek R, Crean C, Joffe A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Oxidative DNA damage associated with combination of guanine and superoxide radicals and repair mechanisms via radical trapping. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32106–32115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spencer JPE, Wong J, Jenner A, Aruoma OI, Cross CE, Halliwell B. Base modification and strand breakage in isolated calf thymus DNA and in DNA from human skin epidermal keratinocytes exposed to peroxynitrite or 3-morpholinosydnonimine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1996;9:1152–1158. doi: 10.1021/tx960084i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cadet J, Berger M, Buchko GW, Joshi PC, Raoul S, Ravanat J-L. 2,2-Diamino-4-[(3,5-di-O--acetyl-2-deoxy-β-D-erythro- pentofuranosyl)amino]-5-(2H)-oxazolone: a novel and predominant radical oxidation product of 3',5'-di-O--acetyl-2'-deoxyguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:7403–7404. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kino K, Saito I, Sugiyama H. Product analysis of GG-specific photooxidation of DNA via electron transfer: 2-Aminoimidazolone as a major guanine oxidation product. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7373–7374. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. Direct observation of the hole protonation state and hole localization site in DNA-oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8614–8619. doi: 10.1021/ja9014869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Misiaszek R, Uvaydov Y, Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Combination reactions of superoxide with 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine radicals in DNA: KINETICS AND END PRODUCTS. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6293–6300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cleveland CL, Barnett RN, Bongiorno A, Joseph J, Liu C, Schuster GB, Landman U. Steric effects on water accessability control sequence-selectivity of radical cation reactions in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8408–8409. doi: 10.1021/ja071893z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ravanat J-L, Martinez GR, Medeiros MHG, Di Mascio P, Cadet J. Singlet oxygen oxidation of 2'-deoxyguanosine. Formation and mechanistic insights. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:10709–10715. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1983;52:711–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xu X, Muller JG, Ye Y, Burrows CJ. DNA-protein cross-links between guanine and lysine depend on the mechanism of oxidation for formation of C5 vs C8 guanosine adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:703–709. doi: 10.1021/ja077102a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]