Abstract

The cardiac sodium current underlies excitability in heart, and inherited abnormalities of the proteins regulating and conducting this current cause inherited arrhythmia syndromes. This review focuses on inherited mutations in non-pore forming proteins of sodium channel complexes that cause cardiac arrhythmia, and the deduced mechanisms by which they affect function and dysfunction of the cardiac sodium current. Defining the structure and function of these complexes and how they are regulated will contribute to understanding the possible roles for this complex in normal and abnormal physiology and homeostasis.

Keywords: Macromolecular complex, Signaling complex, Interacting proteins, sodium current, SCN5A, Arrhythmia, Long QT syndrome, Brugada Syndrome, SIDS

1. Introduction and Background

1.1 INa in heart: excitability, arrhythmogenesis, and sodium-calcium homeostasis

Sodium current (INa) underlies excitability in cardiac ventricular and atrial myocytes and also in specialized conduction tissue including Purkinje cells. Peak INa is a large inward current responsible for rapid upstroke of the action potential (phase 0) and for conduction in working myocardium. The INa flowing just milliseconds after the peak, here called “early INa”, decays rapidly but helps sustain the initial plateau (phase 1) during activation of the transient outward potassium current (Ito). INa then rapidly decays, but a late relatively small INa flowing tens to hundreds of milliseconds after the peak that is less than 1% of the peak INa combines with the inward calcium current to sustain the plateau (phase 2) of the action potential. This late INa is sometimes called sustained or persistent INabut we prefer the more generic term late INa because late INa is often subject to decay and therefore not completely sustained or persistent. Increased late INarepresenting a “gain of function,” prolongs the action potential and produces a long QT interval on the ECG and is arrhythmogenic in part by causing early afterdepolarizations. Increased late INa is a cause of the broader category of the Long QT syndrome (LQTS) arrhythmia. Increased late INa also contributes to sodium loading of myocytes, and by secondarily decreasing extrusion of calcium by sodium/calcium exchange, causes calcium overload [4]. This has effects on both inotropy and lusitropy, and can be arrhythmogenic by producing delayed afterdepolarizations. Decreased peak and early INarepresent a “loss of function”, slows conduction, and is arrhythmogenic by setting up reentry. It can also be arrhythmogenic by allowing for phase 1 repolarization in some myocytes and phase2 reentry, a mechanism suggested for Brugada syndrome (BrS) [6]. Note that it is possible to have in the same tissue both a decrease in peak INa and an increase in late INa as seen in heart failure [8;9], demonstrating an apparent paradox that the terms “gain of function” and “loss of function” as applied to INa are not mutually exclusive. But broadly speaking, the SCN5A channelopathies can be classified as “gain of function” where late INa is increased or “loss of function” where peak and early INa are decreased.

1.2 INa flows through SCN5A; mutations in SCN5A cause channelopathies

The gene Scn5a encodes the subunit protein Nav1.5, also noted as SCN5A (non-italicized and capitalized to represent the protein) which is one of nine isoforms of voltage-dependent sodium channels [12]. It forms the pore through which flows most INa in the heart, “most” because other Nav α subunits carry some INa [14]. The structure/function of SCN5A has been well-studied and reviewed [16–18]. Mutations in Scn5a causing increased late INa have been implicated to cause LQT3 [20], and mutations causing decreased peak/early INa have been implicated to cause a number of syndromes, including BrS, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (IVF), cardiac conduction disease (CCD), sick sinus syndrome (SSS), and familial atrial fibrillation (FAF) [23;24]. Mutations in SCN5A have also been associated with Sudden Infant Death Syndrome or SIDS [26], presumed but not proven to be from arrhythmia, and to be associated with dilated cardiomyopathy [29;30]. Channelopathies affecting SCN5A are not necessarily or exclusively associated with arrhythmia, nor in fact confined to the heart as in the case of a telethonin mutation associated with irritable bowel syndrome [31].

1.3 Sodium channel complexes (SCCs)

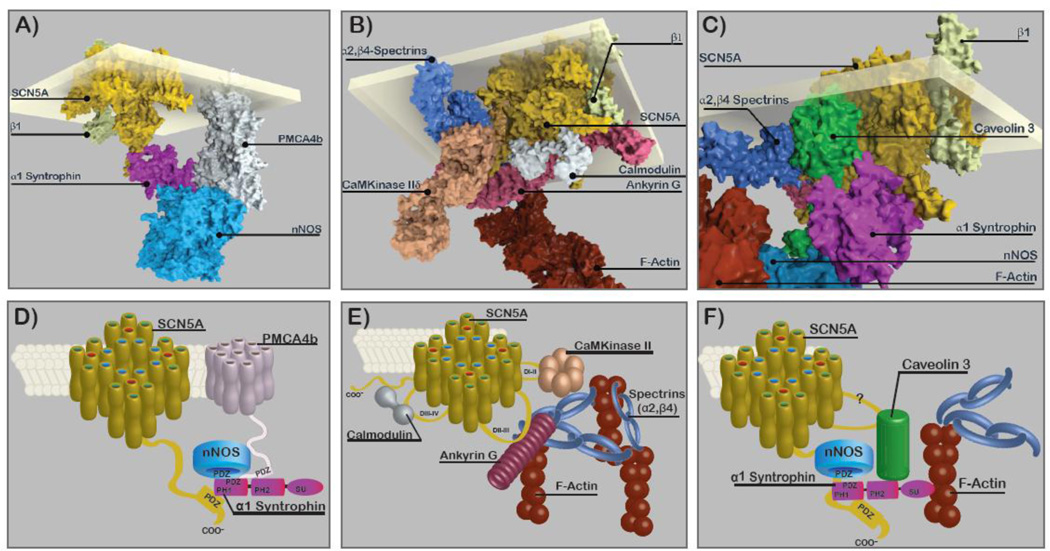

The SCN5A subunit participates in larger protein complexes, also called “macromolecular complex” [35] or “signaling complex” [36], which are composed of many different proteins [41–43] (Fig. 1). The proteins making up SCCs are linked to SCN5A directly or indirectly through intermediary proteins that regulate INa function and/or affect localization. These proteins have been variously called subunits, auxiliary proteins, accessory proteins, channel interacting proteins or ChIPs, adapter proteins, associated proteins, effector proteins, regulatory proteins, anchoring proteins, and scaffolding proteins depending in part on their roles in the complex but often more on author preference without clear definitions. For purposes of this review we will call them Sodium Channel Complex Proteins (SCCPs) and operationally define them as proteins that have a connection to SCN5A demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) or other “pull-down” techniques (such as GST-fusion), either directly to SCN5A, or through intermediary connections. Mutations affecting eight SCCPs have been linked to SCN5A channelopathies (Table 1), but many more have not yet been directly implicated in channelopathies (Table 2). In many cases the sites and nature of the association and interaction have been identified (Table 1&2). Other proteins are candidates to be cardiac SCCPs because they have been shown to have one or more of the following: 1) they affect SCN5A function, 2) they are SCCPs for non-cardiac isoforms of Nav, or attached to a known SCN5A SCCPs (but not yet shown to be part of the SCN5A complex by co-IP or other pull-down). These are listed in a Table S1 in the online supplement.

Figure 1.

SCCP representations of a Syntrophin Complex (A,D), a CaMKinase II Complex, (B,E), and a Caveolin-3 Complex (C,F). Top panels: Atomic scale resolution representations highlighting functionally associated sub-complexes. Bottom panels: Diagrams of the panels above. For construction of the top panels each protein (or if not available, a matched homologue) was accessed from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org). Assembly was done manually taking into account known interactions sites. These renditions are intended to give impressions of relative size, shapes, and attachments and do not represent any energy minimization or other rigorous modeling. Additional details are in the online supplement.

Table 1.

Mutations in Cardiac Sodium Channel (SCN5A) Complex Proteins.

| 96Protein | Gene | Size (aa) | Connection on SCN5A |

Association | Normal INa Effect | Human Mutant | Mutant Effect | Phenotype |

| β1, β1b | Scn1b | β1 218 β1b 268 |

1° DIV P-loop [1] |

Co-IP [3] | Kinetics conflicting (↓) INa Late [5] |

Trp179X | (Ø−) Activ., (Ø −) SSI, (Ø↑) INa Peak | BrS(type 5), CCD[13] |

| (↑)RecR [7] (↑)INa Peak [10] |

E87Q | (Ø−) Activ., (Ø↑) INa Peak | BrS (type 5), CCD [13] | |||||

| 2° through Ankyrin G [19] | Co-IP [19] | R85H | (+) Activ,SSI, (Ø↑) INa Peak | FAF, (↑)R.ST [22] | ||||

| D153N | (Ø↑) INa Peak | FAF [22] | ||||||

| R214Q | (Ø↑) INa Peak [28] | BrS, FAF [28;32] | ||||||

| β2 | Scn2b | 215 | 1° Disulfide Bond, Unknown site [34] | Co-IP [37] | Sialylation Status [38] (↑)Late Current [40] |

R28Q | (+)Activ. (↓) INa Peak | FAF [22] (↑)PR, (↑)R.ST |

| R28W | (+) SSI, (+)Activ, (↓)INa Peak | FAF [13] (↑)PR, (↑)R.ST |

||||||

| β3 | Scn3b | 215 | Unknown, Competitive with β1 [48] | Co-IP [50] | (↑)INa, (↑)RecR [51] (+) SSI, (↑)RefractPer., [50] |

R6K, L10P and M161T | Mixed (↓)INa Peak, (−) SSI, (↓)RecR |

FAF [55] BrS(type7) [57] |

| A130V | (↓)INa Peak | FAF [60] | ||||||

| V54G | (↓)INa Peak (↓)Trafficking |

IVF [63], SIDS [65] | ||||||

| V36M | (↓)INa Peak, (↑)INa Late, | SIDS [65] | ||||||

| β4 | Scn4b | 228 | 1° Disulfide Bond, unknown site [69] | Co-IP {Medeiros-Domingo, 2007 567/id} | (↑) AP Upstroke Velocity (+) SSI [71] |

S206L L179F |

(↑)INa Late, (↑)Window INa | SIDS [65] LQT(type 10) {Medeiros-Domingo, 2007 567/id} |

| Caveolin-3 | Cav3 | 151 | ? | Co-IP [76] | Scaffolding (↓)INa Late [77] |

F97C, S141R | (↑)INa Late, V14L, T78M, and L79R | LQT(type9) [76] (↑)INa Late, SIDS [79] |

| GPD1L | Gpd1l | 351 | ? | GST-PD [80] (Ø) Co-IP [82] |

(↑)INa by phosphorylation [80] | A280V E83K, I124V, R273C |

(↓)INa Peak (↓)INa Peak (+)Activ. in 273C |

BrS (type 2) [85] SIDS [82] |

| MOG1 | Rangrf | 218 | 1° linker DII–DIII [89] | GST-PD, Co-IP [89] | (↑)Surface Density, (↑)INa Peak [89] | E83D | (↓)INa Peak, (↓)Trafficking [89] |

BrS (type 8) [92] |

| 1 syntrophin | Snta1 | 505 | 1° C-terminal S-I-V residues [67] | GST-PD, Co-IP [67]) [87] | Scaffolding | A390V S287R, T372M, G460S |

(↑)INa Peak, (↑)INa Late, (↑)INa Peak, (↑) INa Late, (+) SSI | LQT (type 12) [87] SIDS [95] |

SCN5A structure: DI–DIV= Repeat Domains I–IV; S1-S6= Membrane Spanning Segments 1–6; P-Loop = Pour lining loop. Abbreviations: Ø = A failure to; 1° = Primary association with SCN5A; 2°=Secondary Association with SCN5A by way of intermediate protein; Co-IP=Coimmunoprecipitation; GST-PD=GST Pull Down; (↓)=Decrease in; (↑)=Increase in; (+)=Depolarizing shift; (−)=Hyperpolarizing shift; Activ.=Activation; RecR= Recovery Rate; RefractPer.=Refractory Period; SSI=Steady State Inactivation; INa Peak= Peak Sodium Current; INa Late= Late Sodium Current a.k.a. Persistent Current; BrS=Brugada Syndrome, FAF=Familial Atrial Fibrillation; IVF= Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation; LQT=Long QT Syndrome; SIDS=Sudden Infant Death Syndrome; QT=QT interval on Surface EKG; R. ST=Right Precordial ST elevation

Table 2.

Proposed Sodium Channel Complex Proteins.

Please refer to Table 1 for abbreviations.

| Protein | Gene | Size (aa) | Connection on SCN5A | Association | Normal INa Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14-3-3η | Ywhah | 246 | 1° DI–II linker [2] | Co-IP [2] | (↓)RecR, (−) SSI [2] |

| α Actinin 2 | Actn2 | 894 | 1° DIII–IV linker [11] | Co-IP [11] | (↑) INa Peak [11] |

| Ankyrin G | Ank3 | 4377 | DII–III linker, 14–15 tops Ankyrin G [15] | Co-IP [21] | (↑)Surface Density (↑)INa Peak [21] |

| β4 Spectrin | Sptbn4 | 2,564 | 1° Unknown site, 2° CAMKII-Delta [25] 2° Through Ankyrin G [27] |

Co-IP [25] | (↑)INa Peak, (+) SSI via Phos. S571[25] |

| Calmodulin | Calm1 | 152 | 1° C terminus IQ [33] | GST-PD [39] | (+)SSI [44] |

| 1° DIII–DIV linker [25] | NMR [32] | ||||

| 1° EF Hand [32] | |||||

| CaMKinase IIδ isoform 3 | Camk2d | 510 | 1° DI–II linker [46] | Co-IP [25] | (−) SSI, Phos. @ S571S, 516, T594 |

| 2° IV Spectrin [25] | (↑) INa Late [46] | ||||

| Connexin 40 | Gja5 | 358 | ? | Co-Loc. [53] | ? |

| Connexin 43 | Gja1 | 382 | ? | Co-IP [56] | (↑) INa Peak [49] |

| Desmoglein 2 | Dsg2 | 1118 | ? | Co-IP [62] | (↑) INa Peak [62] |

| Dystrophin | Dmd | 3,685 | 1° Unknown site 2° Syntrophin [67] |

Co-IP [70] | (↑)INa Peak [70] |

| Fibroblast growth factor FGF12B, 13 |

Fgf12 Fgf13 |

181 | 1° C terminus 2° Calmodulin [74] |

Co-IP [75] | (+) SSI (↑) RecR [75] |

| λ2 syntrophin | Sntg2 | 539 | 1° C terminus, PDZ [78] | GST-PD [78] | (+) Activ. [78] |

| Nedd4-2 | Nedd4l | 975 | 1° C terminus PY [83] | GST-PD [83] | (↑) INa Peak [83] |

| nNOS | Nos1 | 1434 | 2° α1 syntrophin [87] | GST, Co-IP [87] | (↑)INa Late [87] |

| Plakophilin-2 | Pkp2 | 881 | 1° Unknown site [90] | Co-IP [90] | (↑) INa Peak (+) SSI [90] |

| PMCA4b | Atp2b4 | 1241 | 2° α1 syntrophin [93] | GST-PD [93] Co-IP [87] |

(↓) INa Late [87] |

| Disks large homolog1 (SAP97) | Dlg1 | 904 | 1° C terminus PDZ [45] | Co-IP {Petitprez, 2011 PETITPREZ2011/id} | (↑) INa Peak [45] |

| Telethonin | Tcap | 167 | 1° Unknown Site [31] | Co-IP [31] | (−) Activ. [31] |

| PTPH1 | Ptpn3 | 913 | 1° C terminus PDZ [96] | GST-PD [96] | (−) SSI [96] |

| Utrophin | Utrn | 3433 | 2° α1 syntrophin [70] | Co-IP [70] | (↓) INa Peak [70] |

| Zasp | Ldb3 | 727 | 1° Unknown Site 2° Telethonin [99] |

GST-PD[99] |

It is advisable to think of SCCs as a family of complexes, as at least two populations of SCCs in cardiac myocytes have been identified [45]. One is located at the myocyte lateral membrane with SNTA1 and a second one is located at the intercalated disc with SAP97/plakophilin-2 (PKP2). Delmar’s group [47] has recently shown that the kinetic properties of INa adult rodent ventricular myocytes differed at the lateral membrane and intercalated disk, raising the possibility that differences in SCCPs at the different locations may be responsible for differences in kinetics. In addition some SCCPs may be other ion channels themselves, such as connexin 43 [49] and KIR2.1 [52]. In addition, it has long been suspected that multiple SCN5A subunits grouped together and interact with other SCN5A subunits within the complex because of cooperativity seen in gating [21;54]. More recently this interaction has been demonstrated [58], making it likely that more than one SCN5A subunits are in SCCs. Sodium channel isoforms other than SCN5A are found in heart (eg [59]), albeit at much lower levels than SCN5A. These are candidates for SCCPs in heart, but it has not yet been demonstrated that they reside in the same complexes as SCN5A. Surely SCN5A SCCs are indeed “complex” and heterogeneous in composition, localization, and function, and they may not be static in any of these qualities but could be dynamic in development, disease, and even normal physiology. In Figure 1 we depict three different putative SCN5A SCCs using both space filling models (top) and diagrams (below). Details of how the models were constructed and access to an interactive display of these models is provided in the online supplement.

1.4 Approaches to studying and understanding structure and function of the SCCs

For this review we have defined an SCCP as a protein that co-IPs with SCN5A, or as proteins showing a physical association by other means, for example by GST-fusion pull-down. By these criteria we have identified eight SCCPs where mutations in them are associated with arrhythmia (Table 1). Twenty-one additional SCCPs (Table 2) meet the SCCP association criteria but arrhythmia mutations in them are yet to be discovered. Co-localization experiments show proximity but do not prove attachment, therefore co-localization alone is not sufficient for our classification as SCCP. Functional characterization of INa has been done by a number of methods. Co-expression of the SCCP with SCN5A in Xenopus oocytes or heterologous transfected cells (eg HEK293 cells) is a usual first step. These models have the advantages of a minimalist system without other sodium channels or SCCPs, but it carries the disadvantage that one SCCP may depend upon the presence of other SCCPs not expressed in that cell type. Another model is targeted knockout of the putative SCCP in mice, or suppression of the SCCP in myocardial cell culture using inhibitory siRNAs. The effects of mutations in SCCPs can be studied by transgenic knock-ins, or overexpression of the mutated SCCP in myocardial cell culture. The development of induced pluripotent stem cells represents a significant advance and holds the promise of studying mutations from myocytes created directly from affected patients (see review [61]). This technique has been used to study mutations in SCN5A [64]. Finally, in some cases we cite data from studies of SCCPs with non-cardiac sodium channel isoforms, recognizing that SCCP interactions and effects may differ with different α subunits (eg, [66]). These different methods of study have advantages and limitations and may result in apparently conflicting results.

2. Arrhythmia syndromes associated with mutations in SCCPs

This review focuses on those SCCPs for which putative mutations have been identified in arrhythmia patients and for which dysfunctional INa supports a plausible arrhythmogenic mechanism through either gain of function, loss of function, or both. Many of these SCCPs interact with other ion channels and may have multiple roles in cardiac myocytes, and thus the mutations may have additional arrhythmogenic mechanisms in addition to INa dysfunction.

2.1 β1 subunit

Scn1b encodes the β1 subunit of voltage-dependent sodium channels and is a member of the cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily [68]. β1, like its homologs β2, β3 and β4, is composed of a single transmembrane spanning region with a short cytosolic C-terminus and an immunoglobulin domain in the extracellular N-terminus. It is expressed in cardiac and neuronal tissues ([22;72;73]) and is alternatively spliced to give a 218 aa β1 or the 268 aa β1b splice variant [73], both of which are expressed in heart [13]. β1 has been shown by co-IP to be associated with both the α subunit [3] as well as the scaffolding protein ankyrin-B [19], implicating at least two potential mechanisms of SCN5A modulation. The primary interaction site appears to be with a region of the P-loop of SCN5A in domain IV (DIVS5-S6) [1]. Phosphorylation status at Tyr(181) in β1 appears important in the formation of the β1 association with ankyrin-G in neural [81] and cardiac tissue [56;84]. A second primary interaction site on the SCN1A C-terminus has been described in neuronal sodium channels [86], but this has not yet been demonstrated for SCN5A. Interestingly, β1 appears to be required for the interaction of α subunits [88] in the SCC.

INa modulation by β1 in heterologous expression systems generally showed increased INa density and decreased late INa (Table 1). INa density was increased by β1 in injected Xenopus oocytes [10] and in transfected HEK293 cells [5], suggesting a loss of β1 function would cause decreased INa density. β1 co-transfection decreased late INa in HEK293 cells [5] and tsA201 experiments [9]. Studies of β1 effects on steady-state inactivation and activation (Table 1) have been contradictory, and generally do not account for decreased peak INa [7;91]. A β1 knockout mouse [18] showed increased late INa and decreased INa density as suggested by the heterologous expression experiments, but did not report kinetic changes in INa activation and inactivation In contrast to this and the experiments in heterologous cells [5;9]), RNA interference-based knockdown of β1 in a canine model for heart failure [40;94] demonstrated no significant effect on peak INa density or kinetics, and late INa was decreased instead of increased. However, at the level of “clinical” phenotype in the surface EKG's of knockout mice [18] showed prolonged QT and RR intervals consistent with a loss of β1 causing decreased peak INa and increased late INa.

Mutations in β1 have been found in patients with BrS, CCD, and AF (Table 1) consistent with loss of function. Truncated β1b (p.Trp179X) and a missense mutation in β1 (E87Q) were found in patients with BrS and CCD [13]. Both variants decreased INa density consistent with the expected loss of function mechanism for these arrhythmia syndromes. They failed to hyperpolarize activation or affect recovery, and the truncated β1b failed to shift inactivation [13]. The β1 mutations R85H and D153N were found in patients with lone AF [22;87;92]. The patient with R85H demonstrated a distinctive right precordial ST elevation on surface EKG resembling BrS. In CHO cells D153N and R85H both decreased INa density compared to wild-type β1[22]. Interestingly, heterologous experiments predict a loss of function of β1 would increase late INabut so far β1 mutations have not been found in LQT. Rare R214Q variants in SCN1Bb have been linked to both BrS and SIDS [28] and modulated both SCN5A and Kv4.3 (Ito); this mutation has also been linked to lone AF [43].

2.2 β2 subunit

The Scn2b gene encodes the sodium channel β2 subunit protein that shares sequence homology and topology with the other sodium channel β subunits, and like β1 has sequence homology to cell adhesion molecules [97]. β2 is expressed in human adult heart in both atria and ventricle expressing more strongly in the epicardium [98]. β2 is localized to the intercalated disks [59] and has been coimmunoprecipitated with SCN5A in mouse heart [3]. Moreover the cysteine residue participating in the SCN5A-β2 intermolecular disulfide bond has been shown to be Cys26 on β2, although the participating SCN5A residue has yet to be elucidated [34]. Mutating the disulfide bond residue at cys-26 decreased INa density when co-expressed with SCN1A [34]. β2 may also act indirectly through ankyrin proteins [100] as shown for neuronal sodium channels, although this association was not found in another study [101].

When β2 was co-expressed with neuronal α subunits in oocytes, INa density was increased without effects on kinetics [97]. In heterologous cells, however, hyperpolarizing shifts in both activation and inactivation were found that depended upon glycosylation[38] and the effects were additive to β1 effects. RNA interference silencing of β2 in normal and failing dog heart [40] caused no effect on peak INa density or kinetics, but late INa was increased (opposite the effect seen with β1 silencing). Finally, a β2 knockout mouse had primarily a neurological phenotype with seizures and reduced neuronal sodium channel density [102] but the effect on the heart and SCN5A, if any, was not described.

Two novel β2 mutants R28Q and R28W were found in patients with lone AF [22] with R28W patients showing prolonged PR interval and right precordial ST elevation on surface EKG. In CHO cells, INa density was decreased and activation was shifted for R28G, and inactivation was positively shifted for R28W. Late INa was not affected [22]. Overall it appears loss or absence of β2 decreased INa.

2.3 β3 subunit

The Scn3b gene encodes a single isoform β3 subunit that has homology to β1, both containing myelin protein zero (MPZ) homology; β3 shares 57 and 47% homology with β1 and β2, respectively [103]. β3 expresses in human ventricle [57], human atria [55] in mice atria and ventricle [104], and in sheep ventricle and Purkinje (but not atria) [51]. Co-IP of β3 with SCN5A has been demonstrated in HEK293 cells [105] and mouse myocardium [50]. By homology to β1, a SCN5A association site is expected [103] but has not yet been demonstrated. Goldin has stated [48] “the β1 and β 3 subunits are non-covalently attached and expressed in a complementary fashion, so that alpha subunits are associated with either β1 or β3”.

In oocytes, expression of β3 with SCN5A increased INa density 3-fold over SCN5A alone, and accelerated recovery, and shifted SSI positively [51]. In heterologous cells, expression of β3 with SCN5A increased INa density with β1 present in tsA201 cells [57], and in HEK293 cells without β1 [65], although some studies report no increase [60;106]. In HEK293 cells late INa was not significantly increased [65]. In SCN3B knockout mice, INa density was increased, the opposite of the expected results, SSI was negatively shifted [107], and sinoatrial and atrial conduction were slowed [50]. Although effects on kinetics are divergent in the various studies, the most consistent effect was that presence of the β3 subunit increased INa density and absence reduced it (loss of function).

The β3 mutation L10P was implicated in BrS (type 7) [57] and caused decreased INa density and decreased expression of SC5NA protein with variable effects on kinetics in transfected tsA201 cells. β3 mutations R6K, L10P and M161T were found in familial atrial fibrillation [55] and all three caused decreased INa when expressed in CHO-5 cells. Identified in a patient with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, the mutant V54G decreased INa density and cell surface expression of SCN5A in HEK293cells which were partially restored by co-expression with the β1 subunit [63]. A β3 mutation V36M found in a SIDS victim greatly decreased INa density in HEK293 cells and also significantly increased late INa relative to peak [65]. The β3 mutant A130V from a patient with AF decreased INa density in a dominant negative fashion without a decrease in surface expression [60]. These β3 mutants have a mixed influence (when co-expression with β1 in heterologous models) on peak INarecovery and inactivation generally leading to a decrease sodium channel availability [55] through decreased channel expression at the surface [63].

2.4 β4 subunit

β4 is similar to β2 in topology, sequence, and associations and joins SCN5A by a disulfide bond via unknown Cys sites. When co-expressed with NaV1.2 and NaV1.4 in tsA201 cells it caused a negative shift in activation [69]. This subunit has been studied mostly with neuronal sodium channels where it is important in the phenomenon of resurgent current [108]. β4 is expressed in mouse ventricle [59] and co-IP’s with SCN5A when expressed in HEK293 cells [109]. β4 had minimal effects on kinetics, INa density or late INa in HEK293 cells when co-expressed with SCN5A. The mutation L179F found in a patient with LQT showed marked increase in late INa and was designated as a novel LQT, LQT10 [109]. A mutation S206L found in a case of SIDS also increased late INa and prolonged action potential duration when overexpressed in rat ventricular myocytes [65]. The detailed mechanisms for the effect on INa are unknown, but it appears mutations in the β4 subunit are arrhythmogenic through an increase late INa.

2.5 Caveolin-3

Caveolin-3 (Cav3) is one of three caveolin isoform that are essential in forming cave-like structures called caveolae, which are nonclathrin coated vesicles. Cav-3 has been shown to regulate several ion currents in heart including INa [110]. Cav-3 is an oligomerized protein and shares features with Caveolin-1 including cytoplasmic N- and C-termini, W-W-like domain, highly conserved aromatic residues [111], a scaffolding domain essential for oligomerization, and palmitoylated cysteine residues at the C-terminus important for sterol interactions [112]. Whereas Caveolin-1 expression is ubiquitous, Cav-3 is restricted to striated muscle and is increases with maturity in rat myocytes [113]. Cav-3 tends to localize to the lateral and t-tubular membranes in cardiac myocytes [114]. In transfected HEK293 cells [76] and in rat cardiac myocytes [84], Cav-3 co-IP’s with SCN5A. The exact residues of association between Cav-3 and SCN5A are not yet known, but many other interaction sites on Cav-3 have been implicated in association with other signaling proteins such as adenylyl cyclase and β adrenergic receptors reflecting its importance as a structural member of the SCCP (eg [115])

Cav-3 appears to be important in mediating adrenergic upregulation of cardiac INa through G proteins [84]. Expression of wild-type Cav-3 with SCN5A in HEK293 cells had no effect on peak INakinetics, or late INa [76;79]. Cav-3 mutants F97C and S141R, however, found in patients with LQTS, increased late INa in HEK293 cells [76] and these were designated LQT9. The Cav-3 mutants V14L, T78M, and L79R found in a SIDS cohort also showed increased late INa in transfected HEK293 cells [79]. Cav-3 is known to be an inhibitor of nNOS [116], and nitrosylation of SCN5A by nNOS has been shown to increase late INa [87]. The LQT9 Cav-3 mutation F97C increased late INa in HEK293 cells, increased late INa and action potential duration in cardiac myocytes, and also increased nitrosylation of SCN5A [77], suggesting that the mechanism for both LQT9 and LQT12 may be through direct SCN5A nitrosylation. Mutations in Cav-3 have also been linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (T64S) [117], although it is not clear the mechanism is through a channelopathy.

2.6 GPD1L

The gene GPD1L encodes the protein GPD1L; the letters stand for “glycerol 3 phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like” because it shares 84% homology with glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (GPD1) [118]. GPD1L was first noted as part of mammalian gene sequence collection program [119], but the function or importance of GPD1L, was unknown. Mutations in GPD1L were linked to BrS in a large family [85], and the GPD1L mutation A280V [82] and the novel SIDS-associated mutation E83K [120] were both shown to decrease INa amplitude. A GST-fusion protein with GPD1L pulled down SCN5A in transfected HEK293 cells suggesting association with SCN5A [80]. The related gene GPD1 encodes a NAD-dependent cytosolic enzyme that is an important link between the glycolytic pathway and triglyceride synthesis, catalyzing the reversible conversion of glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) to dihydroxyacetone phosphate. GPD1L was also shown to have this activity in transfected HEK293 cells and the A280V mutant GPD1L showed significantly decreased enzymatic activity [80]. Decreased GPD1L activity would locally increase substrate G3P and by “mass action” feed the PKC-mediated phosphorylation of SCN5A at serine residue 1503 (S1503) where such phosphorylation is known to decrease INa [121]. In support of this hypothesis the mutation induced decrease in INa was abrogated by pharmacological blockers of the G3P-PKA pathway and was also abrogated by co-expression with the PKC phosphorylation deficient mutant SCN5A-S-1503A [80]. An alternative, or perhaps supplementary pathway, may involve effects of the GPD1L mutants on NAD through PKC and reactive oxygen species, and NAD effects through PKA [122].

2.7 MOG1

The cytosolic multicopy suppressor of gsp1 (MOG1) affects protein trafficking through Ran, a GTP binding nuclear protein [123]. MOG1 is found in neonatal mouse ventricles localized to the intercalated disks [89] and is highly expressed in heart [124]. Association with SCN5A was discovered through yeast two-hybrid screen and confirmed with GST-SCN5A DII–DIII linker pull-down [89]. Co-IP in lysates prepared from mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes also confirmed the association of MOG1 and SCN5A [89]. Heterologous expression in HEK293 cells and MOG1 overexpression in neonatal myocytes led to increased expression of SCN5A and peak INa [89;92]. siRNA interference knock-down of MOG1 impaired SCN5A trafficking [92]. Coexpression of SCN5A with the MOG1 mutant, E83D, discovered in a BrS patient showed marked reduction of INa and evidence of impaired trafficking when expressed in HEK293 cells and when over expressed in neonatal mouse myocytes [92] in a dominant negative fashion. MOG1 does not appear to affect SCN5A kinetics [92]. The MOG1 mutant loss of function appears to cause BrS by decreasing SCN5A trafficking to the cell surface and decreased peak INa.

2.8 Alpha-1-Syntrophin

The cytosolic scaffolding product of the Snta1 gene is the rod-shaped alpha-1-syntrophin (SNTA1) protein. SNTA1 is part of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex and plays a role in linking proteins to the cytoskeleton. SNTA1 contains a PDZ (PSD-95, Disk-large and ZO-1) domain, two pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, and a syntrophin unique (SU) domain allowing for its role in multiple protein complex interactions including other syntrophins and dystrophin [125]. It is expressed in human heart [67] and is associated with SCN5A as shown by GST pull-down using a SCN5A C-terminus GST-fusion protein [87] expressed in transfected HEK293 cells and by co-IP from lysates prepared from mouse ventricles [67]. SNTA1 is suggested to associate via the PDZ domain to the three specific residues, Ser-Ile-Val at the SCN5A distal end of the C-terminus. [67] and is localized to lateral membrane of cardiac myocytes [45].

Mutations in SNTA1 have been associated with LQTS (LQT12) [87] and SIDS [95] with a proposed mechanism of increased late INa. Based on the associations of nNOS, SNTA1, PMCA4b [93] and SNTA1 with SCN5A [67], the full complex (Fig. 1A) was demonstrated in mouse heart by co-IP [87]. The LQT12 mutation A390V in SNTA1 was shown to selectively disrupt association of PMCA4b, a plasma membrane calcium transporter and an nNOS inhibitor [126], from the complex, leading to increased direct nitrosylation of SCN5A and late INa [87]. This represents an example of how disruption of members of the SCC that link to SCN5A through intermediates can result in a channelopathy.

3. Other Cardiac SCCPs

Many cardiac SCCPs have been identified that modulate cardiac INabut mutations in these proteins that have yet to be discovered in patients with inherited arrhythmias of unknown origin. These SCCPs (listed in Table 2, with additional possible SCCPs discussed in the online supplement) are candidate genes for SCN5A channelopathies.

3.1 Ankyrin-G

The cytosolic protein product of Ank3ankyrin 3 or ankyrin-G, is a scaffolding protein that bridges ion channel complexes with the spectrin-actin cytoskeleton [127]. Ankyrin-G shares homology with other ankyrins in four functional domains: membrane-binding domain (MBD), spectrin-binding domain (SBD), death domain (DD) and a C-terminal regulatory domain (CTD) [128]. Ankyrin-G is expressed in the human heart and has been shown by co-IP to associate with SCN5A in both rat myocytes and transfected HEK293 cells. In cardiac myocytes ankyrin-G is localized to intercalated discs and T-tubule membranes [19]. The interaction with SCN5A occurs in a conserved 9-aa sequence in the cytosolic DII–III linker loop of SCN5A [129] through repeats 14–15 loop tops on ankyrin-G [15]. In rat cardiomyocytes with ankyrin-G expression reduced by siRNA, total SCN5A expression, plasma membrane localization, and INa were reduced, without an effect on kinetics [15]. A signaling complex consisting of CaM Kinase II linked to SCN5A by βIV-spectrin and ankyrin-G (Fig. 1B,E) phosphorylates SCN5A at S571 [25] to increase late INa.

The other eight SCN5A SCCPs described above cause channelopathies by mutations within the SCCP. So far no mutations in ankyrin-g have been associated with arrhythmia. A mutation in SCN5A (E1053K) discovered in a patient with BrS disrupts association of SCN5A with ankyrin-G, resulting in decreased INa [19]. Interestingly, peak INa density was not affected, but steady-state inactivation was shifted in the hyperpolarizing direction, INa decay was accelerated, and recovery from inactivation was slowed [19] suggesting a kinetic loss of function at normal resting potentials in heart. As it was subsequently shown that the main effect of loss of ankyrin-G is decreased INa density without a change in kinetics [15], it may be that the E1053K mutation has effects unrelated to binding to ankyrin-G. Also LQT3 mutations nearby the S571 residues in SCN5A mimic phosphorylation and cause increased late INa [46], but to date no arrhythmia related mutations in the SCCPs of this complex have been identified.

3.2 Plakophillin 2

Plakophillin2 (PKP2) is a desmosomal protein, belonging to the armadillo family of proteins, important in the context of intercellular junctions in cardiomyocytes. Structurally they consist of a head domain, 9-armadillo repeat domains and a tail domain [130]. PKP2 was associated with Nav1.5 by Co-IP and immunolocalized to the intercalated disc in cardiac myocytes [90]. Knockdown of PKP2 in cultured cardiomyocytes altered the properties of the INa and GST pull-down assays demonstrated that the head domain of PKP2 associates with Nav1.5 [90]. It is not known if this association is direct or indirect. Mutations in PKP2 have been implicated in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) as part of the desmosome complex [131] also involving connexin43 [49]. Haploinsufficiency of PKP2 in mice downregulated INa and was associated with arrhythmia [132]. Similarly a mutant in the desmosome associated protein desmoglein-2 decreased INa density when overexpressed in mouse myocytes [62]. Decreased SCN5A and connexin43 protein was observed in tissue from a majority of ARVC patients with various mutations including PKP2 and other AVRC mutations, as well as from patients without a known AVRC mutation [133]. These effects on SCN5A in AVRC may be caused by a more general remodeling in the desmosome from mutations in a number of proteins, and may represent an SCN5A channelopathy intermediate between the more specific SCCP induced SCN5A channelopathies (Table 1), and the more general SCN5A channelopathy caused by electrical remodeling in heart failure [134].

3.3 Synapse Associated Protein-97

Synapse associated protein-97 (SAP97) is a scaffolding protein belonging to the membrane associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family of proteins. They have been shown to play an important role in assembling signaling complexes at the membrane due to their modular structure consisting of 3 PDZ domains, a guanylate kinase like (GK) domain, a hook domain and a SRC homology-3 (SH3) domain. Abriel and colleagues have reported that SAP97 associated with the extreme carboxyl-terminus (residues-S-I-V) of SCN5A by GST pull-down assays and also by Co-IP [45]. SAP97 has been shown to localize to the intercalated disc and T-tubules in cardiac myocytes and knockdown of SAP97 in HEK293 cells and cultured rat atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes resulted in reduced INa density [45;52]. No known mutations in SAP97 have yet been linked to SCN5A channelopathies.

5. Comments and Conclusions

Channelopathies caused by mutations in SCCPs, although relatively rare clinically, are “natural” experiments that give insight into the structure function of SCCs. For example, a function for GPD1L was completely unknown until associated with SCN5A and BrS [82]. Conversely, work associating SNTA1 with SCN5A [67] led to the discovery of LQT12 [87] and further definition of a particular SCC (Fig. 1A,D). Genotype-negative inherited arrhythmia patients (patients for which the causative gene and mutations are unknown) remain an issue especially for BrS [135]. Moreover mutations in SCCPs causing channelopathies appear to be relatively common in SIDS [79] [65] [95] [94] [65], suggesting more SCCP channeopathy genes to be discovered in SIDS patients. In addition to discovering novel SCCPs and channelopathies, future research that defines the composition, localization, dynamic nature, and regulatory functions of the various classes of SCCs will provide insights into mechanisms of channelopathies associated with the even greater health problem that is acquired heart disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights for review.

Sodium channel complex proteins (SCCPs) regulate the sodium current in the heart.

Inherited mutations in SCCPs cause abnormalities in channel function called channelopathies which underlie cardiac arrhythmia.

The literature for established and potential SCCPs is reviewed with a special focus on those SCCPs that have known arrhythmia causing mutations.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH NHLBI HL71092 and T32 HL07936

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Qu Y, Rogers JC, Chen SF, McCormick KA, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional roles of the extracellular segments of the sodium channel α subunit in voltage-dependent gating and modulation by β1 subunits. J Biol Chem. 1999 Nov 12;274(46):32647–32654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allouis M, Le Bouffant F, Wilders R, Peroz D, Schott JJ, Noireaud J, et al. 14-3-3 is a regulator of the cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5. Circ Res. 2006 Jun 23;98(12):1538–1546. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000229244.97497.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhar MJ, Chen C, Rivolta I, Abriel H, Malhotra R, Mattei LN, et al. Characterization of sodium channel alpha- and beta-subunits in rat and mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2001 Mar 6;103(9):1303–1310. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makielski JC, Farley AL. Na(+) current in human ventricle: implications for sodium loading and homeostasis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006 May;17(Suppl 1):S15–S20. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valdivia CR, Nagatomo T, Makielski JC. Late currents affect kinetics for heart and skeletal Na channel α and β1 subunits expressed in HEK293 cells. Journal of Molecular & Cellular Cardiology. 2002 doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2040. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antzelevitch C. The Brugada syndrome: ionic basis and arrhythmia mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001 Feb;12(2):268–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herfst LJ, Potet F, Bezzina CR, Groenewegen WA, Le Marec H, Hoorntje TM, et al. Na+ channel mutation leading to loss of function and non-progressive cardiac conduction defects. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003 May;35(5):549–557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdivia CR, Haworth RA, Wood JN, Makielski JC. Increased late Na+ current from a canine heart failure model and from human heart failure. Biophys J. 2000;78:523. Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maltsev VA, Kyle JW, Undrovinas A. Late Na+ current produced by human cardiac Na+ channel isoform Nav1.5 is modulated by its beta1 subunit. J Physiol Sci. 2009 May;59(3):217–225. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuss HB, Chiamvimonvat N, Perez-Garcia MT, Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Functional association of the β1 subunit with human cardiac (hH1) and rat skeletal muscle (ε1) sodium channel α subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1995 Dec;106(6):1171–1191. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.6.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziane R, Huang H, Moghadaszadeh B, Beggs AH, Levesque G, Chahine M. Cell membrane expression of cardiac sodium channel Na(v)1.5 is modulated by alpha-actinin-2 interaction. Biochemistry. 2010 Jan 12;49(1):166–178. doi: 10.1021/bi901086v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldin AL, Barchi RL, Caldwell JH, Hofmann F, Howe JR, Hunter JC, et al. Nomenclature of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000 Nov;28(2):365–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe H, Koopmann TT, Le Scouarnec S, Yang T, Ingram CR, Schott JJ, et al. Sodium channel beta1 subunit mutations associated with Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease in humans. J Clin Invest. 2008 Jun;118(6):2260–2268. doi: 10.1172/JCI33891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maier SK, Westenbroek RE, Schenkman KA, Feigl EO, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. An unexpected role for brain-type sodium channels in coupling of cell surface depolarization to contraction in the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002 Mar 19;99(6):4073–4078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261705699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe JS, Palygin O, Bhasin N, Hund TJ, Boyden PA, Shibata E, et al. Voltage-gated Nav channel targeting in the heart requires an ankyrin-G dependent cellular pathway. J Cell Biol. 2008 Jan 14;180(1):173–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balser JR. The cardiac sodium channel: gating function and molecular pharmacology. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001 Apr;33(4):599–613. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000 Apr;26(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez-Santiago LF, Meadows LS, Ernst SJ, Chen C, Malhotra JD, Mcewen DP, et al. Sodium channel Scn1b null mice exhibit prolonged QT and RR intervals. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007 Aug 10; doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohler PJ, Rivolta I, Napolitano C, LeMaillet G, Lambert S, Priori SG, et al. Nav1.5 E1053K mutation causing Brugada syndrome blocks binding to ankyrin-G and expression of Nav1.5 on the surface of cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Dec 14;101(50):17533–17538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett PB, Yazawa K, Makita N, George AL., Jr Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995;376:683–685. doi: 10.1038/376683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiba T, Hesketh GG, Liu T, Carlisle R, Villa-Abrille MC, O'Rourke B, et al. Na+ channel regulation by Ca2+/calmodulin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2010 Feb 1;85(3):454–463. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe H, Darbar D, Kaiser DW, Jiramongkolchai K, Chopra S, Donahue BS, et al. Mutations in sodium channel beta1-and beta2-subunits associated with atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Jun;2(3):268–275. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.779181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruan Y, Liu N, Priori SG. Sodium channel mutations and arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009 May;6(5):337–348. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilde AA, Brugada R. Phenotypical manifestations of mutations in the genes encoding subunits of the cardiac sodium channel. Circ Res. 2011 Apr 1;108(7):884–897. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.238469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hund TJ, Koval OM, Li J, Wright PJ, Qian L, Snyder JS, et al. A beta(IV)-spectrin/CaMKII signaling complex is essential for membrane excitability in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010 Oct;120(10):3508–3519. doi: 10.1172/JCI43621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ackerman MJ, Siu BL, Sturner WQ, Tester DJ, Valdivia CR, Makielski JC, et al. Postmortem molecular analysis of SCN5A defects in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA. 2001 Nov 14;286(18):2264–2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komada M, Soriano P. [Beta]IV-spectrin regulates sodium channel clustering through ankyrin-G at axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier. J Cell Biol. 2002 Jan 21;156(2):337–348. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, Medeiros-Domingo A, Crotti L, Veltmann C, Schimpf R, et al. A novel rare variant in SCN1Bb linked to Brugada syndrome and SIDS by combined modulation of Na(v)1.5 and K(v)4.3 channel currents. Heart Rhythm. 2012 May;9(5):760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson TM, Michels VV, Ballew JD, Reyna SP, Karst ML, Herron KJ, et al. Sodium channel mutations and susceptibility to heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005 Jan 26;293(4):447–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng J, Morales A, Siegfried JD, Li D, Norton N, Song J, et al. SCN5A rare variants in familial dilated cardiomyopathy decrease peak sodium current depending on the common polymorphism H558R and common splice variant Q1077del. Clin Transl Sci. 2010 Dec;3(6):287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzone A, Strege PR, Tester DJ, Bernard CE, Faulkner G, De Giorgio R, et al. A mutation in telethonin alters nav1.5 function. J Biol Chem. 2008 Jun 13;283(24):16537–16544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801744200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chagot B, Chazin WJ. Solution NMR structure of Apo-calmodulin in complex with the IQ motif of human cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5. J Mol Biol. 2011 Feb 11;406(1):106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potet F, Chagot B, Anghelescu M, Viswanathan PC, Stepanovic SZ, Kupershmidt S, et al. Functional Interactions between Distinct Sodium Channel Cytoplasmic Domains through the Action of Calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2009 Mar 27;284(13):8846–8854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806871200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C, Calhoun JD, Zhang Y, Lopez-Santiago L, Zhou N, Davis TH, et al. Identification of the cysteine residue responsible for disulfide linkage of Na+ channel alpha and beta2 subunits. J Biol Chem. 2012 Nov 9;287(46):39061–39069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.397646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meadows LS, Isom LL. Sodium channels as macromolecular complexes: implications for inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Cardiovasc Res. 2005 Aug 15;67(3):448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catterall WA. Signaling complexes of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Neurosci Lett. 2010 Dec 10;486(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaborit N, Steenman M, Lamirault G, Le Meur N, Le Bouter S, Lande G, et al. Human atrial ion channel and transporter subunit gene-expression remodeling associated with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005 Jul 26;112(4):471–481. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.506857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson D, Bennett ES. Isoform-specific effects of the beta2 subunit on voltage-gated sodium channel gating. J Biol Chem. 2006 Sep 8;281(36):25875–25881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim J, Ghosh S, Liu H, Tateyama M, Kass RS, Pitt GS. Calmodulin mediates Ca2+ sensitivity of sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2004 Oct 22;279(43):45004–45012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra S, Undrovinas NA, Maltsev VA, Reznikov V, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas A. Post-transcriptional silencing of SCN1B and SCN2B genes modulates late sodium current in cardiac myocytes from normal dogs and dogs with chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011 Oct;301(4):H1596–H1605. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00948.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abriel H. Cardiac sodium channel Na(v)1.5 and interacting proteins: Physiology and pathophysiology. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009 Sep 8; doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shy D, Gillet L, Abriel H. Cardiac sodium channel Na(V)1.5 distribution in myocytes via interacting proteins: The multiple pool model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 Oct 31; doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olesen MS, Holst AG, Svendsen JH, Haunso S, Tfelt-Hansen J. SCN1Bb R214Q found in 3 patients: 1 with Brugada syndrome and 2 with lone atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2012 May;9(5):770–773. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan HL, Kupershmidt S, Zhang R, Stepanovic S, Roden DM, Wilde AA, et al. A calcium sensor in the sodium channel modulates cardiac excitability. Nature. 2002 Jan 24;415(6870):442–447. doi: 10.1038/415442a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petitprez S, Zmoos AF, Ogrodnik J, Balse E, Raad N, El Haou S, et al. SAP97 and dystrophin macromolecular complexes determine two pools of cardiac sodium channels Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011 Feb 4;108(3):294–304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koval OM, Snyder JS, Wolf RM, Pavlovicz RE, Glynn P, Curran J, et al. Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II-Based Regulation of Voltage-Gated Na+ Channel in Cardiac Disease. Circulation. 2012 Oct 23;126(17):2084–2094. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin X, Liu N, Lu J, Zhang J, Anumonwo JM, Isom LL, et al. Subcellular heterogeneity of sodium current properties in adult cardiac ventricular myocytes. Heart Rhythm. 2011 Dec;8(12):1923–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldin AL. Mechanisms of sodium channel inactivation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003 Jun;13(3):284–290. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jansen JA, Noorman M, Musa H, Stein M, de Jong S, van der NR, et al. Reduced heterogeneous expression of Cx43 results in decreased Nav1.5 expression and reduced sodium current that accounts for arrhythmia vulnerability in conditional Cx43 knockout mice. Heart Rhythm. 2012 Apr;9(4):600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hakim P, Brice N, Thresher R, Lawrence J, Zhang Y, Jackson AP, et al. Scn3b knockout mice exhibit abnormal sino-atrial and cardiac conduction properties. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010 Jan;198(1):47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fahmi AI, Patel M, Stevens EB, Fowden AL, John JE, III, Lee K, et al. The sodium channel beta-subunit SCN3b modulates the kinetics of SCN5a and is expressed heterogeneously in sheep heart. J Physiol. 2001 Dec 15;537(Pt 3):693–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Milstein ML, Musa H, Balbuena DP, Anumonwo JM, Auerbach DS, Furspan PB, et al. Dynamic reciprocity of sodium and potassium channel expression in a macromolecular complex controls cardiac excitability and arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Jul 31;109(31):E2134–E2143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109370109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Velden HM, Jongsma HJ. Cardiac gap junctions and connexins: their role in atrial fibrillation and potential as therapeutic targets. Cardiovasc Res. 2002 May;54(2):270–279. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Undrovinas AI, Fleidervish IA, Makielski JC. Inward sodium current at resting potentials in single cardiac myocytes induced by the ischemic metabolite lysophosphatidylcholine. Circ Res. 1992 Nov;71(5):1231–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.5.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olesen MS, Jespersen T, Nielsen JB, Liang B, Moller DV, Hedley P, et al. Mutations in sodium channel beta-subunit SCN3B are associated with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2011 Mar 1;89(4):786–793. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malhotra JD, Thyagarajan V, Chen C, Isom LL. Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated sodium channel beta1 subunits are differentially localized in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004 Sep 24;279(39):40748–40754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, Burashnikov E, Springer M, Wu Y, Varro A, et al. A mutation in the beta3 subunit ofthe cardiac sodium channel associated with Brugada ECG phenotype. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.829192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clatot J, Ziyadeh-Isleem A, Maugenre S, Denjoy I, Liu H, Dilanian G, et al. Dominant-negative effect of SCN5A N-terminal mutations through the interaction of Nav1.5 alpha-subunits. Cardiovasc Res. 2012 Oct 1;96(1):53–63. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maier SKG, Westenbroek RE, McCormick KA, Curtis R, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Distinct subcellular localization of different sodium channel alpha and beta subunits in single ventricular myocytes from mouse heart. Circulation. 2004 Mar 23;109(11):1421–1427. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121421.61896.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang P, Yang Q, Wu X, Yang Y, Shi L, Wang C, et al. Functional dominant-negative mutation of sodium channel subunit gene SCN3B associated with atrial fibrillation in a Chinese GeneID population. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010 Jul 16;398(1):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamp TJ. An electrifying iPSC disease model: long QT syndrome type 2 and heart cells in a dish. Cell Stem Cell. 2011 Feb 4;8(2):130–131. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rizzo S, Lodder EM, Verkerk AO, Wolswinkel R, Beekman L, Pilichou K, et al. Intercalated disc abnormalities, reduced Na(+) current density, and conduction slowing in desmoglein-2 mutant mice prior to cardiomyopathic changes. Cardiovasc Res. 2012 Sep 1;95(4):409–418. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valdivia CR, Medeiros-Domingo A, Ye B, Shen WK, Algiers TJ, Ackerman MJ, et al. Loss-of-function mutation of the SCN3B-encoded sodium channel {beta}3 subunit associated with a case of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010 Jun 1;86(3):392–400. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davis RP, Casini S, van den Berg CW, Hoekstra M, Remme CA, Dambrot C, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from pluripotent stem cells recapitulate electrophysiological characteristics of an overlap syndrome of cardiac sodium channel disease. Circulation. 2012 Jun 26;125(25):3079–3091. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan BH, Pundi KN, Van Norstrand DW, Valdivia CR, Tester DJ, Medeiros-Domingo A, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome-associated mutations in the sodium channel beta subunits. Heart Rhythm. 2010 Jun;7(6):771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valdivia CR, Nagatomo T, Makielski JC. Late Na currents affected by alpha subunit isoform and beta1 subunit co-expression in HEK293 cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002 Aug;34(8):1029–1039. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gavillet B, Rougier JS, Domenighetti AA, Behar R, Boixel C, Ruchat P, et al. Cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 is regulated by a multiprotein complex composed of syntrophins and dystrophin. Circ Res. 2006 Aug 18;99(4):407–414. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237466.13252.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Isom LL, Catterall WA. Na+ channel subunits and Ig domains. Nature. 1996 Sep 26;383(6598):307–308. doi: 10.1038/383307b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu FH, Westenbroek RE, Silos-Santiago I, McCormick KA, Lawson D, Ge P, et al. Sodium channel beta 4, a new disulfide-linked auxiliary subunit with similarity to beta 2. J Neurosci. 2003 Aug 20;23(20):7577–7585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Albesa M, Ogrodnik J, Rougier JS, Abriel H. Regulation of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by utrophin in dystrophin-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2011 Feb 1;89(2):320–328. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Remme CA, Scicluna BP, Verkerk AO, Amin AS, van Brunschot S, Beekman L, et al. Genetically determined differences in sodium current characteristics modulate conduction disease severity in mice with cardiac sodium channelopathy. Circ Res. 2009 Jun 5;104(11):1283–1292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qu Y, Isom LL, Westenbroek RE, Rogers JC, Tanada TN, McCormick KA, et al. Modulation of cardiac Na+ channel expression in Xenopus oocytes by β1 subunits. J Biol Chem. 1995 Oct 27;270(43):25696–25701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qin N, D'Andrea MR, Lubin ML, Shafaee N, Codd EE, Correa AM. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the human sodium channel beta(1B) subunit, a novel splicing variant of the beta(1) subunit. Eur J Biochem. 2003 Dec;270(23):4762–4770. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang C, Chung BC, Yan H, Lee SY, Pitt GS. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of a NaV C-terminal domain, a fibroblast growth factor homologous factor, and calmodulin. Structure. 2012 Jul 3;20(7):1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang C, Hennessey JA, Kirkton RD, Wang C, Graham V, Puranam RS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 13 regulates Na+ channels and conduction velocity in murine hearts. Circ Res. 2011 Sep 16;109(7):775–782. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vatta M, Ackerman MJ, Ye B, Makielski JC, Ughanze EE, Taylor EW, et al. Mutant caveolin-3 induces persistent late sodium current and is associated with long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2006 Nov 14;114(20):2104–2112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cheng J, Valdivia C, Vaidyanathn R, Balijepalli RC, Ackerman MJ, Makielski JC. Caveolin-3 suppresses late sodium current by inhibiting nNOS-dependent S-nitrosylation of SCN5A. JMCC. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.013. Ref Type: Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ou YJ, Strege P, Miller SM, Makielski J, Ackerman M, Gibbons SJ, et al. Syntrophin gamma 2 regulates SCN5A Gating by a PDZ domain-mediated interaction. J Biol Chem. 2003 Jan 17;278(3):1915–1923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cronk LB, Ye B, Kaku T, Tester DJ, Vatta M, Makielski JC, et al. Novel mechanism for sudden infant death syndrome: Persistent late sodium current secondary to mutations in caveolin-3. Heart Rhythm. 2007 Feb;4(2):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Valdivia CR, Ueda K, Ackerman MJ, Makielski JC. GPD1L links redox state to cardiac excitability by PKC-dependent phosphorylation of the sodium channel SCN5A. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 Oct;297(4):H1446–H1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00513.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malhotra JD, Koopmann MC, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Fettman N, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel beta 1 subunits with ankyrin. J Biol Chem. 2002 Jul 19;277(29):26681–26688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.London B, Michalec M, Mehdi H, Zhu X, Kerchner L, Sanyal S, et al. Mutation in glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like gene (GPD1-L) decreases cardiac Na+ current and causes inherited arrhythmias. Circulation. 2007 Nov 13;116(20):2260–2268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Bemmelen MX, Rougier JS, Gavillet B, Apotheloz F, Daidie D, Tateyama M, et al. Cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5 is regulated by Nedd4-2 mediated ubiquitination. Circ Res. 2004 Aug 6;95(3):284–291. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000136816.05109.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yarbrough TL, Lu T, Lee HC, Shibata EF. Localization of cardiac sodium channels in caveolin-rich membrane domains: regulation of sodium current amplitude. Circ Res. 2002 Mar 8;90(4):443–449. doi: 10.1161/hh0402.105177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weiss R, Barmada MM, Nguyen T, Seibel JS, Cavlovich D, Kornblit CA, et al. Clinical and molecular heterogeneity in the Brugada syndrome: a novel gene locus on chromosome 3. Circulation. 2002 Feb 12;105(6):707–713. doi: 10.1161/hc0602.103618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spampanato J, Kearney JA, de Haan G, Mcewen DP, Escayg A, Aradi I, et al. A novel epilepsy mutation in the sodium channel SCN1A identifies a cytoplasmic domain for beta subunit interaction. J Neurosci. 2004 Nov 3;24(44):10022–10034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2034-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ueda K, Valdivia C, Medeiros-Domingo A, Tester DJ, Vatta M, Farrugia G, et al. Syntrophin mutation associated with long QT syndrome through activation of the nNOS-SCN5A macromolecular complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Jul 8;105(27):9355–9360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801294105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mercier A, Clement R, Harnois T, Bourmeyster N, Faivre JF, Findlay I, et al. The beta1-subunit of Na(v)1.5 cardiac sodium channel is required for a dominant negative effect through alpha-alpha interaction. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu L, Yong SL, Fan C, Ni Y, Yoo S, Zhang T, et al. Identification of a new co-factor, MOG1, required for the full function of cardiac sodium channel Nav 1.5. J Biol Chem. 2008 Mar 14;283(11):6968–6978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sato PY, Musa H, Coombs W, Guerrero-Serna G, Patino GA, Taffet SM, et al. Loss of plakophilin-2 expression leads to decreased sodium current and slower conduction velocity in cultured cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009 Sep 11;105(6):523–526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Malhotra JD, Chen C, Rivolta I, Abriel H, Malhotra R, Mattei LN, et al. Characterization of sodium channel α- and β-Subunits in rat and mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2001 Mar 6;103(9):1303–1310. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kattygnarath D, Maugenre S, Neyroud N, Balse E, Ichai C, Denjoy I, et al. MOG1: a new susceptibility gene for Brugada syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011 Jun;4(3):261–268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.959130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Williams JC, Armesilla AL, Mohamed TM, Hagarty CL, McIntyre FH, Schomburg S, et al. The sarcolemmal calcium pump, alpha-1 syntrophin, and neuronal nitric-oxide synthase are parts of a macromolecular protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2006 Aug 18;281(33):23341–23348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Van Norstrand DW, Valdivia CR, Tester DJ, Ueda K, London B, Makielski JC, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of novel glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like gene (GPD1-L) mutations in sudden infant death syndrome. Circulation. 2007 Nov 13;116(20):2253–2259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cheng J, Van Norstrand DW, Medeiros-Domingo A, Valdivia C, Tan BH, Ye B, et al. Alpha1-syntrophin mutations identified in sudden infant death syndrome cause an increase in late cardiac sodium current. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Dec;2(6):667–676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.891440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jespersen T, Gavillet B, van Bemmelen MX, Cordonier S, Thomas MA, Staub O, et al. Cardiac sodium channel Na(v)1.5 interacts with and is regulated by the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPH1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006 Oct 6;348(4):1455–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Isom LL, Ragsdale DS, De Jongh KS, Westenbroek RE, Reber BF, Scheuer T, et al. Structure and function of the beta 2 subunit of brain sodium channels, a transmembrane glycoprotein with a CAM motif. Cell. 1995 Nov 3;83(3):433–442. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gaborit N, Le Bouter S, Szuts V, Varro A, Escande D, Nattel S, et al. Regional and tissue specific transcript signatures of ion channel genes in the non-diseased human heart. J Physiol. 2007 Jul 15;582(Pt 2):675–693. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xi Y, Ai T, De Lange E, Li Z, Wu G, Brunelli L, et al. Loss of function of hNav1.5 by a ZASP1 mutation associated with intraventricular conduction disturbances in left ventricular noncompaction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012 Oct;5(5):1017–1026. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.969220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Malhotra JD, Kazen-Gillespie K, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Sodium channel beta subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell-cell contact. J Biol Chem. 2000 Apr 14;275(15):11383–11388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bouzidi M, Tricaud N, Giraud P, Kordeli E, Caillol G, Deleuze C, et al. Interaction of the Nav1.2a subunit of the voltage-dependent sodium channel with nodal ankyrinG. In vitro mapping of the interacting domains and association in synaptosomes. J Biol Chem. 2002 Aug 9;277(32):28996–29004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen CL, Bharucha V, Chen YA, Westenbroek RE, Brown A, Malhotra JD, et al. Reduced sodium channel density, altered voltage dependence of inactivation, and increased susceptibility to seizures in mice lacking sodium channel beta 2-subunits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002 Dec 24;99(26):17072–17077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212638099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Morgan K, Stevens EB, Shah B, Cox PJ, Dixon AK, Lee K, et al. beta 3: an additional auxiliary subunit of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel that modulates channel gating with distinct kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Feb 29;97(5):2308–2313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030362197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hakim P, Brice N, Thresher R, Lawrence J, Zhang Y, Jackson AP, et al. Scn3b knockout mice exhibit abnormal sino-atrial and cardiac conduction properties. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009 Oct 1; doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Valdivia CR, Medeiros-Domingo A, Ye B, Shen WK, Algiers TJ, Ackerman MJ, et al. Loss of Function Mutation of the SCN3B-Encoded Sodium Channel {beta}3 Subunit Associated with a Case of Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2009 Dec 30; doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ko SH, Lenkowski PW, Lee HC, Mounsey JP, Patel MK. Modulation of Na(v)1.5 by beta1-- and beta3-subunit co-expression in mammalian cells. Pflugers Arch. 2005 Jan;449(4):403–412. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hakim P, Gurung IS, Pedersen TH, Thresher R, Brice N, Lawrence J, et al. Scn3b knockout mice exhibit abnormal ventricular electrophysiological properties. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008 Oct;98(2–3):251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cannon SC, Bean BP. Sodium channels gone wild: resurgent current from neuronal and muscle channelopathies. J Clin Invest. 2010 Jan;120(1):80–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI41340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Medeiros-Domingo A, Kaku T, Tester DJ, Iturralde-Torres P, Itty A, Ye B, et al. SCN4B-Encoded Sodium Channel {beta}4 Subunit in Congenital Long-QT Syndrome. Circulation. 2007 Jun 25;116:136–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Balijepalli RC, Kamp TJ. Caveolae, ion channels and cardiac arrhythmias. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008 Oct;98(2–3):149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sotgia F, Lee JK, Das K, Bedford M, Petrucci TC, Macioce P, et al. Caveolin-3 directly interacts with the C-terminal tail of beta -dystroglycan. Identification of a central WW-like domain within caveolin family members. J Biol Chem. 2000 Dec 1;275(48):38048–38058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Uittenbogaard A, Smart EJ. Palmitoylation of caveolin-1 is required for cholesterol binding, chaperone complex formation, and rapid transport of cholesterol to caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000 Aug 18;275(33):25595–25599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003401200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rybin VO, Grabham PW, Elouardighi H, Steinberg SF. Caveolae-associated proteins in cardiomyocytes: caveolin-2 expression and interactions with caveolin-3. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003 Jul;285(1):H325–H332. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00946.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Balijepalli RC, Foell JD, Hall DD, Hell JW, Kamp TJ. Localization of cardiac L-type Ca(2+) channels to a caveolar macromolecular signaling complex is required for beta(2)-adrenergic regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 May 9;103(19):7500–7505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503465103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ostrom RS, Bundey RA, Insel PA. Nitric oxide inhibition of adenylyl cyclase type 6 activity is dependent upon lipid rafts and caveolin signaling complexes. J Biol Chem. 2004 May 7;279(19):19846–19853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Venema VJ, Ju H, Zou R, Venema RC. Interaction of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase with caveolin-3 in skeletal muscle. Identification of a novel caveolin scaffolding/inhibitory domain. J Biol Chem. 1997 Nov 7;272(45):28187–28190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hayashi T, Arimura T, Ueda K, Shibata H, Hohda S, Takahashi M, et al. Identification and functional analysis of a caveolin-3 mutation associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004 Jan 2;313(1):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ou X, Ji C, Han X, Zhao X, Li X, Mao Y, et al. Crystal structures of human glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (GPD1) J Mol Biol. 2006 Mar 31;357(3):858–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, et al. Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Dec 24;99(26):16899–16903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242603899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Van Norstrand DW, Valdivia CR, Tester DJ, Ueda K, London B, Makielski JC, et al. Molecular and Functional Characterization of Novel Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase 1 Like Gene (GPD1-L) Mutations in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Circulation. 2007 Oct 29; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Murray KT, Hu NN, Daw JR, Shin HG, Watson MT, Mashburn AB, et al. Functional effects of protein kinase C activation on the human cardiac Na+ channel. Circ Res. 1997 Mar;80(3):370–376. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liu M, Sanyal S, Gao G, Gurung IS, Zhu X, Gaconnet G, et al. Cardiac Na+ current regulation by pyridine nucleotides. Circ Res. 2009 Oct 9;105(8):737–745. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Steggerda SM, Paschal BM. Identification of a conserved loop in Mog1 that releases GTP from Ran. Traffic. 2001 Nov;2(11):804–811. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.21109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Marfatia KA, Harreman MT, Fanara P, Vertino PM, Corbett AH. Identification and characterization of the human MOG1 gene. Gene. 2001 Mar 21;266(1–2):45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ahn AH, Freener CA, Gussoni E, Yoshida M, Ozawa E, Kunkel LM. The three human syntrophin genes are expressed in diverse tissues, have distinct chromosomal locations, and each bind to dystrophin and its relatives. J Biol Chem. 1996 Feb 2;271(5):2724–2730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Oceandy D, Cartwright EJ, Emerson M, Prehar S, Baudoin FM, Zi M, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase signaling in the heart is regulated by the sarcolemmal calcium pump 4b. Circulation. 2007 Jan 30;115(4):483–492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bennett V, Baines AJ. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol Rev. 2001 Jul;81(3):1353–1392. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cunha SR, Mohler PJ. Cardiac ankyrins: Essential components for development and maintenance of excitable membrane domains in heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2006 Jul 1;71(1):22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.LeMaillet G, Walker B, Lambert S. Identification of a conserved ankyrin-binding motif in the family of sodium channel alpha subunits. J Biol Chem. 2003 Jul 25;278(30):27333–27339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Delva E, Tucker DK, Kowalczyk AP. The desmosome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009 Aug;1(2):a002543. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Delmar M. Desmosome-ion channel interactions and their possible role in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012 Aug;33(6):975–979. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cerrone M, Noorman M, Lin X, Chkourko H, Liang FX, van der NR, et al. Sodium current deficit and arrhythmogenesis in a murine model of plakophilin-2 haploinsufficiency. Cardiovasc Res. 2012 Sep 1;95(4):460–468. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Noorman M, Hakim S, Kessler E, Groeneweg JA, Cox MG, Asimaki A, et al. Remodeling of the cardiac sodium channel, connexin43, and plakoglobin at the intercalated disk in patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Mar;10(3):412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Valdivia CR, Chu WW, Pu JL, Foell JD, Haworth RA, Wolff MR, et al. Increased late sodium current in myocytes from a canine heart failure model and from failing human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005 Mar;38(3):475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lehnart SE, Ackerman MJ, Benson DW, Jr, Brugada R, Clancy CE, Donahue JK, et al. Inherited arrhythmias: a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases workshop consensus report about the diagnosis, phenotyping, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches for primary cardiomyopathies of gene mutations affecting ion channel function. Circulation. 2007 Nov 13;116(20):2325–2345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data