Abstract

Mitosis is the process of one cell dividing into two daughters, such that each inherits a single and complete copy of the genome of their mother. This is achieved through the equal segregation of the sister chromatids between the daughter cells. However, beyond this simple principle, the partitioning of other cellular components between daughter cells appears to follow a large variety of patterns. We discuss here how the organization of the nuclear envelope during mitosis influences cell division and, subsequently, cellular identity.

Keywords: closed mitosis, open mitosis, compartmentalization, nuclear envelope, asymmetric cell division

Introduction

Eukaryotic chromosomes are surrounded by a double membrane (consisting of an inner and outer nuclear membrane) called the nuclear envelope. Depending on the organism and cell type, the nuclear envelope either remains intact or disassembles before chromosome segregation; these forms of mitosis are termed closed and open division, respectively. Closed mitosis is considered to be the most ancient mechanism of eukaryotic cell division,1 whereas open mitosis appears to have been invented several times during evolution. Animals and plants, for example, are related more distantly to each other than to fungi.2 Nevertheless, both undergo open mitosis, whereas most fungi retain an intact nuclear envelope during division.1,3 Within the six supergroups of eukaryotes,4 consisting of Opisthokonts (fungi, animals and some protists), Amoebozoa, Excavates, Chromoalveolates, Archaeplastids and Rhizaria, open as well as closed forms of mitosis have been described—except for Excavates, which exclusively undergo closed mitosis.1,3 Among others, Fungi and Amoebozoa explore the whole spectrum from open to semi-open and closed mitosis, suggesting that multiple solutions for nuclear division exist, each with its advantages and disadvantages. Here, we discuss the consequences of open vs. closed mitosis, focusing on nuclear compartmentalization during closed mitosis and the importance of nuclear envelope disassembly for progression through anaphase.

Nuclear Envelope Dynamics and the Asymmetric Segregation of Cell Identity Factors

In addition to the symmetric distribution of chromosomes between sister cells, cell division often also involves the asymmetric segregation of cellular components. In some cases, this asymmetry relies on the presence and organization of the nuclear envelope. During metazoan embryogenesis, asymmetric cell divisions diversify a pool of precursor cells into different cell types. In adult organisms, asymmetric divisions constantly regenerate various tissues. Indeed, stem cells are generally thought to divide asymmetrically during both embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis. They maintain an unlimited division potential, whereas their differentiating progeny only divide a few times before undergoing terminal differentiation. Similarly to differentiating cells, individual budding yeast cells can only produce a limited number of direct progeny.5 During the budding yeast cell cycle, a smaller daughter cell grows from a larger mother cell.6 This daughter cell survives its mother and expresses its own transcriptional programs.7-10 Consequently, daughter cells represent an eternal lineage in a population of budding yeast cells.

One of the mechanisms through which eternal and differentiating/aging lineages differ from each other involves the asymmetric segregation of factors defining these fates. Depending on whether these factors are fixed or freely diffusing, different mechanisms ensure the asymmetry of their inheritance. If cell identity factors are immobilized on a structure, asymmetric inheritance can be achieved by segregating this structure into only one of the two sister cells. Cell identity factors diffusing freely in two-dimensional membranes or three-dimensional liquid phases can be segregated asymmetrically only if their exchange between the future sister-cells is restricted in some way. Budding yeast cells, for example, take advantage of their closed mitosis to extensively compartmentalize their nuclei during division. This compartmentalization is used to asymmetrically segregate cellular components such as the transcription factor Ace2 and non-chromosomal DNA.11-13

The daughter-specific transcription factor Ace2 (activator of CUP1 expression) diffuses freely in the budding yeast nucleus but strongly accumulates in the daughter half of the dividing nucleus.9,11,14 The asymmetry of Ace2 localization is established at the end of anaphase by a network of kinases and phosphatases that differentially regulate its nuclear import and export in the two halves of the nucleus.14,15 Importantly, initiating and maintaining/increasing this asymmetry requires the compartmentalization of the nucleoplasm between the future mother and daughter parts of the dividing nucleus.11 This compartmentalization is ensured by the dumbbell-morphology of the late anaphase nucleus. Mutants with a wider and/or shorter bridge exchange Ace2 and other nucleoplasmic molecules more rapidly between the two halves of the nucleus, resulting in a more homogenous distribution of Ace2 between mother and bud. Hence, the presence of the nuclear envelope during mitosis is essential for the asymmetry of Ace2 segregation.

Ace2 homologs are present in the genomes of many fungi.16 In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Schizosaccharomyces japonicus, Candida albicans and Candida glabrata, Ace2 induces the transcription of genes encoding cell wall degrading enzymes genes involved in sister cell separation after mitosis.16-20 During the yeast-like growth phase of C. albicans, Ace2 accumulates in the daughter nucleus of large budded cells, similarly to its budding yeast homolog.17 The C. albicans nucleus also adopts a dumbbell-like shape during division, probably providing the basis for the maintenance of Ace2 asymmetry by nucleoplasmic compartmentalization. In contrast, S. pombe has a dumbbell shaped nucleus but distributes Ace2 symmetrically.21 Ace2 being not the sole nuclear factor to segregate asymmetrically in budding yeast (see below), the dumbbell morphology of the fission yeast nucleus might in this case help to maintain other asymmetries than that of Ace2.

During budding yeast mitosis, nuclear compartmentalization also promotes the retention of acentromeric DNA in the mother cell.12,13 The accumulation of these acentromeric episomes in turn contributes to aging of the yeast mother cell as it divides.22-24 Extrachromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs) are naturally occurring episomes that are excised from the rDNA locus by homologous recombination.22,25 Aging yeast mother cells accumulate large numbers of ERCs, since ERCs are retained in the mother nucleus, where they proliferate through replication.

Several non-exclusive mechanisms converge to ensure the retention of episomes in budding yeast mother cells (as discussed by Ouellet and Barral26). The asymmetry of episomes diffusing freely in the nucleoplasm strongly depends on the geometrical constraints of the dividing nuclear envelope and the time spent in nuclear division, as both parameters determine to which extent episomes can equilibrate between mother and daughter parts of the nucleus before division.13 The morphology of the dividing nucleus and the time needed for nuclear division set a basal retention frequency for individual plasmids to about 85% per division. The retention frequencies of a second class of episomes, which also includes ERCs, is much higher, with about 96% to over 99% retained in the mother cell.22,27 In addition to nuclear geometry and timing, the high retention frequencies of these episomes also depend on the compartmentalization of the nuclear envelope. Highly retained non-centromeric episomes are tethered to the nuclear envelope and a diffusion barrier in the ONM restricts their segregation to the daughter part of the nucleus.12 Failure to attach to the nuclear periphery and mutations weakening the diffusion barrier in the ONM decrease the asymmetry of their segregation to levels similar to episomes diffusing freely in the nucleoplasm.12,25 Consequently, it has been proposed that the diffusion barrier in the ONM is required for high episome retention frequencies in budding yeast cells.26

In S. pombe, acentromeric self-replicating episomes are also asymmetrically segregated to one of the daughter cells.28 Furthermore, ERCs have been isolated from fission yeast.29,30 If integrated into a bacterial vector backbone, fission yeast ERC sequences are able to promote plasmid replication in vivo, suggesting ERCs are able to self-amplify in fission yeast.30 How episomes are segregated asymmetrically in fission yeast is still unclear. The comparison to budding yeast, however, strongly suggests that nuclear compartmentalization may contribute to the asymmetry of episome inheritance in both budding and fission yeast.

Chromosome Segregation during Closed Mitosis

In addition to the segregation of individual proteins and relatively small acentromeric episomes, the nuclear envelope has also been implicated in chromosome segregation during closed mitosis. In organisms undergoing both closed and open mitoses, the mitotic spindle generally segregates chromatids during mitosis. However, when cells undergo closed mitosis in the absence of nuclear spindle microtubules, contacts between the nuclear envelope and chromatin can also promote the segregation of the chromosomes.

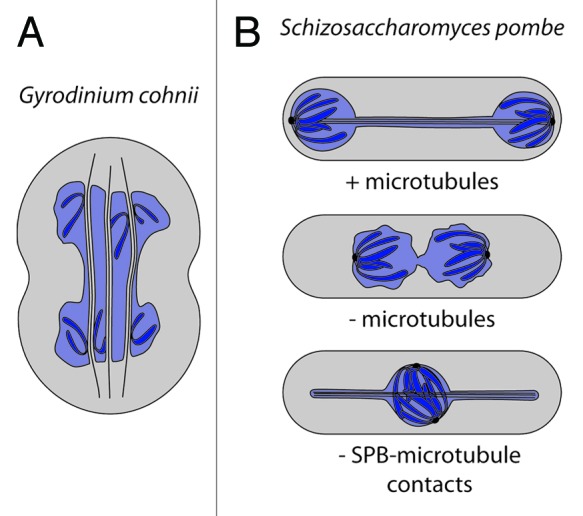

Certain dinoflagellates, for example divide without disassembling their nuclear envelope and without assembling an intranuclear spindle(Fig. 1).31-33 Chromosome segregation in these organisms involves the interaction of chromosomes with the nuclear envelope, which is in contact with ordered arrays of cytoplasmic microtubules. These microtubules transverse the dividing nucleus in parallel while they are wrapped by pipes of nuclear envelope. Chromosomes intimately contact the nuclear envelope surrounding the individual microtubule bundles and appear to slide along the membrane, resulting in their segregation into two future nuclei.

Figure 1. Late anaphase / telophase during closed mitosis without nucleoplasmic spindle microtubules or SPB-microtubule contacts. (A) Chromosomes (dark blue) of the dinoflagellate G. cohnii are separated as they slide along NE tubes, which enwrap microtubule bundles penetrating in the nucleoplasm (light blue). (B) Nuclei of the fission yeast S. pombe dividing with or without microtubules or with microtubules attached to the SPB.

Such intimate chromatin-nuclear envelope contacts might also be present in S. pombe, since these cells are also able to divide their nuclei in the absence of a mitotic spindle in a process termed nuclear fission.34 The maturation of spindle pole bodies (SPBs) and the separation of sister chromatids are two key factors driving nuclear fission. In the absence of SPB-associated proteins linking chromatin to the nuclear periphery, nuclear fission is impaired. It seems that, in fission yeast, the interaction between chromatin and the nuclear envelope is not only passively maintained during nuclear division but also actively shapes the dividing nucleus and drives karyofission. Supporting this idea, inhibiting chromosome segregation in presence of an elongating anaphase spindle interferes with nuclear division and changes nuclear shape. Upon uncoupling of the SPB from the pole of the elongating spindle, chromatin masses are not separated and remain in the center of the nucleus.35-38 At the same time, the growing spindle microtubules push the nuclear envelope, producing projections that give the late anaphase nucleus a pan- instead of a dumbbell-shaped form (Fig. 1). Both examples together illustrate that the segregation of DNA largely influences the morphology of the dividing nucleus and that it potentially even drives nuclear fission.

In budding yeast, the interaction between chromatin and the nuclear envelope during mitosis potentially contributes to the separation of chromatids as well. The INM protein Src1 (also called Heh139) is involved in chromosome segregation, as indicated by the fact that src1∆ mutant cells have a shorter anaphase and that this deletion shows genetic interactions with genes involved in chromatid separation at anaphase onset.40 Furthermore, Src1 interacts with chromatin.41-43 Interactions of chromatin with Src1 or other INM proteins could keep separated chromosomes apart in the short timeframe between spindle breakdown and karyofission. Thereby chromatin-nuclear envelope contacts could contribute to the faithful segregation of the chromosomes between mother and daughter nuclei.

Anaphase With or Without a Nuclear Envelope

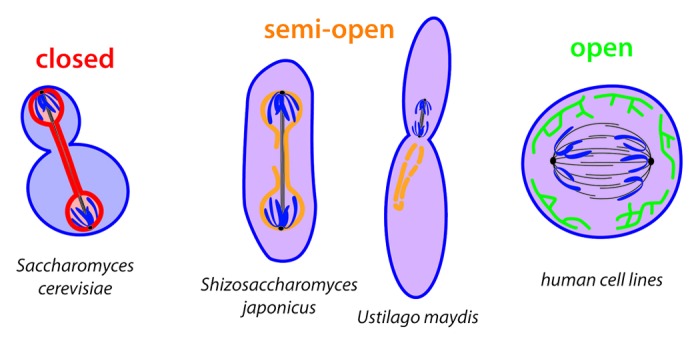

In contrast to fungi, metazoan cells fully disassemble their nuclear envelope at some point during cell division. The timing of nuclear envelope disassembly varies significantly between organisms and cells types. In addition, some fungi undergo only a partially closed mitosis, starting with an intact nuclear envelope and assembling an intranuclear spindle before breaking the nuclear envelope open at a later time point. In contrast to the true open mitosis of metazoans, the nuclear envelope does not disperse completely in these cases; instead it ruptures and/or fenestrates without disappearing (Fig. 2). A closer look at the spectrum cells explore between open and closed mitosis provides insight into what drives cells to disassemble their nuclear envelope during mitosis.

Figure 2. Different fates of the nuclear envelope during anaphase: “intact” (red) during closed mitosis in S.cerevisiae separating nucleoplasm (light red) and cytoplasm (light blue), “fenestrated” (orange) during semi-open mitosis in S. japonicus and U. maydis. allowing nucleoplasm and cytoplasm to mix (purple) and “completely disassembled,” incorporated into the ER (green) during open mitosis in human cell lines.

As one example, the fission yeast S. japonicus begins mitosis with an intact nuclear envelope and assembles an intranuclear mitotic spindle.44,45 The elongating anaphase spindle causes the nucleus to adopt a diamond shape. As the intranuclear spindle extends, it both begins to buckle and exerts a force on the nuclear envelope that is only relieved as the nuclear membranes rupture on one side of the nucleus. At this point, the separation of cytoplasm and nucleoplasm is lost and only reestablished after mitosis. The nuclear envelope, however, does not dissolve but remains present throughout mitosis.

As a second example, the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis partially disassembles and additionally fenestrates its nuclear envelope prior to metaphase onset.46,47 In this case, the nuclear envelope ruptures asymmetrically. The spindle specifically exits the elongating nucleus at the tip facing the bud neck between the future mother and daughter cell.46 Thereby the spindle leaves the preexisting nuclear envelope behind in the mother cell and translocates into the daughter cell cytoplasm where chromatin separation is initiated. In addition, NPCs partially disassemble once the nucleus opens at its tip, leading to a fenestration of the nuclear envelope.47

In the cases of both S. japonicus and U. maydis, the nuclear envelope does not disassemble completely. Therefore, the nuclear envelope as such might still serve as a platform for the transport, the segregation and potentially the asymmetric partitioning of associated factors and structures despite the loss of nucleo-cytoplasmic compartmentalization.

Despite the different mechanisms with which the nuclear envelope opens, the switch from closed to (semi-)open mitosis takes place latest as cells start chromosome segregation. These observations suggest that during closed mitosis, anaphase is a critical point for nuclear envelope integrity. Indeed, during closed mitosis, the most dramatic rearrangements of nuclear shape take place in anaphase, when the spherical metaphase nucleus transforms into an elongated dumbbell shape. Since this represents a process during which the original sphere is transformed into two, the nuclear surface must increase by a third in order to maintain a constant nuclear volume. This increase in nuclear envelope surface is observed during anaphase in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe,48-50 whereas it is absent in S. japonicus.44

In general, the volume of the nucleus depends on the volume of the surrounding cytoplasm.51,52 Due to this so-called karyoplasmic ratio, larger cells have larger nuclei. Consequently, in larger cells the larger nucleus will have a larger absolute change in surface during mitosis than the nucleus of smaller cells. The sheer magnitude of membrane addition necessary during closed mitosis could force large cells to disassemble their nuclear envelope rather than synthesizing or diverting sufficient membrane material over the short course of anaphase. Cells of the fission yeast S. japonicus, for example, are approximately twice the size of S. pombe cells—their close relatives. The nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) separate into two separate pools early during the mitosis of S. japonicus.44,45 Consequently, this fungus may potentially use attachment to NPCs to partition nuclear components between the two daughters. The nuclei of animal and plant cells are even larger than those of S. japonicus. Consequently, one reason why they undergo nuclear envelope disassembly may be to avoid having to provide large amounts of new membrane material prior to nuclear envelope reassembly.

In plant cells and human cell lines, the nuclear envelope breaks down during prometaphase,53,54 whereas in young sea urchin embryos, nuclear envelope disassembly occurs after metaphase.55,56 Similarly, nuclear envelope-like structures surrounding mitotic spindles have been observed in invertebrates. During early embryonic and neuroblast divisions of Drosophila melanogaster, the nuclear envelope still surrounds chromatin during metaphase.57-59 In early C. elegans embryogenesis, transmembrane proteins of the INM are detectable at the periphery of chromatin as late as early anaphase.60,61 Chromosome condensation and the attachment of chromosomes to spindle microtubules can occur within a nuclear envelope-like structure, whereas anaphase is completed only after nuclear envelope disassembly. This suggests that, in animal cells, progression through anaphase requires complete removal of the nuclear envelope and its resorption into the ER. If any asymmetry would still be provided by the original structure of the nucleus, its propagation through mitosis would now rely on the ER being compartmentalized. Although this is the case in yeast, compartmentalization of the ER has not yet been reported for metazoans.

The second prediction from the observations in S. japonicus is that animal cells are unable to increase their nuclear surface during mitosis. We did not find any data precisely measuring nuclear envelope surface in animal cells before and after mitosis. However, a study by Anderson and colleagues suggests that the amount of membrane material available for nuclear envelope formation in human cells is limited.62 At the end of mitosis, the nuclear envelope is reformed through contacts between ER membrane tubules and decondensing chromatin.62-64 This requires the transformation of highly curved ER membrane tubes into flat membrane sheets to form the nuclear envelope. Overexpression of proteins inducing membrane curvature in the ER causes reduced increases in nuclear size after mitosis.62 Consequently, mechanisms stabilizing the organization of the ER could counteract the incorporation of membrane material in the nuclear envelope and thereby limit the amount available.

To date we have only little knowledge about the factors driving the evolution of mitosis in eukaryotes. Therefore, we can only speculate about why eukaryotes developed a range of mechanisms to progress through the cell cycle. However, even the limited knowledge currently available indicates that the cell biology of nuclear division has clear consequences for segregation of nuclear factors as well as for anaphase progression. Future studies on the variations between open and closed mitosis will allow a more detailed understanding of the relationship between nuclear geometry, mitotic progression and asymmetric cell fate, as well as the forces that have driven the evolution of these diverse mechanisms of mitosis. However, at this point, several parameters appear to play key roles: the possibility for the nuclear envelope to control the symmetric or asymmetric segregation of nuclear components as well as the size of the nucleus. We propose that the interplay between these parameters determines which mitotic mechanisms are chosen and that these mechanisms, in turn, contribute to evolution.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Barral laboratory for helpful discussions. B. Boettcher was supported by the BarrAge grant from the European Research Council to Y. Barral.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/24676

References

- 1.Cavalier-Smith T. Origin of the cell nucleus, mitosis and sex: roles of intracellular coevolution. Biol Direct. 2010;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldauf SL, Roger AJ, Wenk-Siefert I, Doolittle WF. A kingdom-level phylogeny of eukaryotes based on combined protein data. Science. 2000;290:972–7. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson DJ. The Diversity of Eukaryotes. Am Nat. 1999;154(s4):S96–124. doi: 10.1086/303287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampl V, Hug L, Leigh JW, Dacks JB, Lang BF, Simpson AGB, et al. Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Excavata and resolve relationships among eukaryotic “supergroups”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807880106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mortimer RK, Johnston JR. Life span of individual yeast cells. Nature. 1959;183:1751–2. doi: 10.1038/1831751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartwell LH, Unger MW. Unequal division in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its implications for the control of cell division. J Cell Biol. 1977;75:422–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.75.2.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy BK, Austriaco NR, Jr., Guarente L. Daughter cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae from old mothers display a reduced life span. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1985–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobola N, Jansen RP, Shin TH, Nasmyth K. Asymmetric accumulation of Ash1p in postanaphase nuclei depends on a myosin and restricts yeast mating-type switching to mother cells. Cell. 1996;84:699–709. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colman-Lerner A, Chin TE, Brent R. Yeast Cbk1 and Mob2 activate daughter-specific genetic programs to induce asymmetric cell fates. Cell. 2001;107:739–50. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sil A, Herskowitz I. Identification of asymmetrically localized determinant, Ash1p, required for lineage-specific transcription of the yeast HO gene. Cell. 1996;84:711–22. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boettcher B, Marquez-Lago TT, Bayer M, Weiss EL, Barral Y. Nuclear envelope morphology constrains diffusion and promotes asymmetric protein segregation in closed mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:921–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shcheprova Z, Baldi S, Frei SB, Gonnet G, Barral Y. A mechanism for asymmetric segregation of age during yeast budding. Nature. 2008;454:728–34. doi: 10.1038/nature07212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gehlen LR, Nagai S, Shimada K, Meister P, Taddei A, Gasser SM. Nuclear geometry and rapid mitosis ensure asymmetric episome segregation in yeast. Curr Biol. 2011;21:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazanka E, Alexander J, Yeh BJ, Charoenpong P, Lowery DM, Yaffe M, et al. The NDR/LATS family kinase Cbk1 directly controls transcriptional asymmetry. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazanka E, Weiss EL. Sequential counteracting kinases restrict an asymmetric gene expression program to early G1. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2809–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balazs A, Batta G, Miklos I, Acs-Szabo L, Vazquez de Aldana CR, Sipiczki M. Conserved regulators of the cell separation process in Schizosaccharomyces. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49:235–49. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly MT, MacCallum DM, Clancy SD, Odds FC, Brown AJP, Butler G. The Candida albicans CaACE2 gene affects morphogenesis, adherence and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:969–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stead DA, Walker J, Holcombe L, Gibbs SRS, Yin Z, Selway L, et al. Impact of the transcriptional regulator, Ace2, on the Candida glabrata secretome. Proteomics. 2010;10:212–23. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martín-Cuadrado AB, Dueñas E, Sipiczki M, Vázquez de Aldana CR, del Rey F. The endo-beta-1,3-glucanase eng1p is required for dissolution of the primary septum during cell separation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1689–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dohrmann PR, Butler G, Tamai K, Dorland S, Greene JR, Thiele DJ, et al. Parallel pathways of gene regulation: homologous regulators SWI5 and ACE2 differentially control transcription of HO and chitinase. Genes Dev. 1992;6:93–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petit CS, Mehta S, Roberts RH, Gould KL. Ace2p contributes to fission yeast septin ring assembly by regulating mid2+ expression. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5731–42. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinclair DA, Guarente L. Extrachromosomal rDNA circles--a cause of aging in yeast. Cell. 1997;91:1033–42. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson KA, Gottschling DE. A mother’s sacrifice: what is she keeping for herself? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:723–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falcón AA, Aris JP. Plasmid accumulation reduces life span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41607–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307025200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindstrom DL, Leverich CK, Henderson KA, Gottschling DE. Replicative Age Induces Mitotic Recombination in the Ribosomal RNA Gene Cluster of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rine J, ed. PLoS Genet 2011;7(3):e1002015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouellet J, Barral Y. Organelle segregation during mitosis: lessons from asymmetrically dividing cells. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:305–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillespie CS, Proctor CJ, Boys RJ, Shanley DP, Wilkinson DJ, Kirkwood TBL. A mathematical model of ageing in yeast. J Theor Biol. 2004;229:189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heyer WD, Sipiczki M, Kohli J. Replicating plasmids in Schizosaccharomyces pombe: improvement of symmetric segregation by a new genetic element. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:80–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anziano PQ, Perlman PS, Lang BF, Wolf K. The mitochondrial genome of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Curr Genet. 1983;7:273–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00376072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fournier P, Gaillardin C, Louvencourt L, Heslot H, Lang BF, Kaudewitz F. r-DNA plasmid from Schizosaccharomyces pombe: cloning and use in yeast transformation. Curr Genet. 1982;6:31–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00397639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubai DF, Ris H. Division in the dinoflagellate Gyrodinium cohnii (Schiller). A new type of nuclear reproduction. J Cell Biol. 1969;40:508–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.40.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perret E, Davoust J, Albert M, Besseau L, Soyer-Gobillard MO. Microtubule organization during the cell cycle of the primitive eukaryote dinoflagellate Crypthecodinium cohnii. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:639–51. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.3.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barlow SB, Triemer RE. The mitotic apparatus in the dinoflagellateAmphidinium carterae. Protoplasma. 1988;145:16–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01323252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castagnetti S, Oliferenko S, Nurse P. Fission Yeast Cells Undergo Nuclear Division in the Absence of Spindle Microtubules. Lichten M, ed. Plos Biol 2010;8(10):e1000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng L, Schwartz C, Magidson V, Khodjakov A, Oliferenko S. The spindle pole bodies facilitate nuclear envelope division during closed mitosis in fission yeast. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West RR, Vaisberg EV, Ding R, Nurse P, McIntosh JR. cut11(+): A gene required for cell cycle-dependent spindle pole body anchoring in the nuclear envelope and bipolar spindle formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2839–55. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.10.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toya M, Sato M, Haselmann U, Asakawa K, Brunner D, Antony C, et al. γ-tubulin complex-mediated anchoring of spindle microtubules to spindle-pole bodies requires Msd1 in fission yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:646–53. doi: 10.1038/ncb1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khodjakov A, La Terra S, Chang F. Laser microsurgery in fission yeast; role of the mitotic spindle midzone in anaphase B. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1330–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King MC, Lusk CP, Blobel G. Karyopherin-mediated import of integral inner nuclear membrane proteins. Nature. 2006;442:1003–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodríguez-Navarro S, Igual JC, Pérez-Ortín JE. SRC1: an intron-containing yeast gene involved in sister chromatid segregation. Yeast. 2002;19:43–54. doi: 10.1002/yea.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang J, Brito IL, Villén J, Gygi SP, Amon A, Moazed D. Inhibition of homologous recombination by a cohesin-associated clamp complex recruited to the rDNA recombination enhancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2887–901. doi: 10.1101/gad.1472706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mekhail K, Seebacher J, Gygi SP, Moazed D. Role for perinuclear chromosome tethering in maintenance of genome stability. Nature. 2008;456:667–70. doi: 10.1038/nature07460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grund SE, Fischer T, Cabal GG, Antúnez O, Pérez-Ortín JE, Hurt E. The inner nuclear membrane protein Src1 associates with subtelomeric genes and alters their regulated gene expression. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:897–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yam C, He Y, Zhang D, Chiam K-H, Oliferenko S. Divergent strategies for controlling the nuclear membrane satisfy geometric constraints during nuclear division. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aoki K, Hayashi H, Furuya K, Sato M, Takagi T, Osumi M, et al. Breakage of the nuclear envelope by an extending mitotic nucleus occurs during anaphase in Schizosaccharomyces japonicus. Genes Cells. 2011;16:911–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straube A, Weber I, Steinberg G. A novel mechanism of nuclear envelope break-down in a fungus: nuclear migration strips off the envelope. EMBO J. 2005;24:1674–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theisen U, Straube A, Steinberg G. Dynamic rearrangement of nucleoporins during fungal “open” mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1230–40. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalez Y, Meerbrey K, Chong J, Torii Y, Padte NN, Sazer S. Nuclear shape, growth and integrity in the closed mitosis of fission yeast depend on the Ran-GTPase system, the spindle pole body and the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2464–72. doi: 10.1242/jcs.049999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lim HWG, Huber G, Torii Y, Hirata A, Miller J, Sazer S. Vesicle-Like Biomechanics Governs Important Aspects of Nuclear Geometry in Fission Yeast. Secomb T, ed. PLoS ONE 2007;2(9):e948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winey M, Yarar D, Giddings TH, Jr., Mastronarde DN. Nuclear pore complex number and distribution throughout the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle by three-dimensional reconstruction from electron micrographs of nuclear envelopes. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:2119–32. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.11.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jorgensen P, Edgington NP, Schneider BL, Rupes I, Tyers M, Futcher B. The size of the nucleus increases as yeast cells grow. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3523–32. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neumann FR, Nurse P. Nuclear size control in fission yeast. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:593–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Güttinger S, Laurell E, Kutay U. Orchestrating nuclear envelope disassembly and reassembly during mitosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:178–91. doi: 10.1038/nrm2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rose A. Open mitosis: nuclear envelope dynamics. Cell Division Control in Plants 2008:207–230. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lénárt P, Rabut G, Daigle N, Hand AR, Terasaki M, Ellenberg J. Nuclear envelope breakdown in starfish oocytes proceeds by partial NPC disassembly followed by a rapidly spreading fenestration of nuclear membranes. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:1055–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terasaki M. Dynamics of the endoplasmic reticulum and golgi apparatus during early sea urchin development. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:897–914. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katsani KR, Karess RE, Dostatni N, Doye V. In vivo dynamics of Drosophila nuclear envelope components. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3652–66. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner N, Kagermeier B, Loserth S, Krohne G. The Drosophila melanogaster LEM-domain protein MAN1. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harel A, Zlotkin E, Nainudel-Epszteyn S, Feinstein N, Fisher PA, Gruenbaum Y. Persistence of major nuclear envelope antigens in an envelope-like structure during mitosis in Drosophila melanogaster embryos. J Cell Sci. 1989;94:463–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.94.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee KK, Gruenbaum Y, Spann P, Liu J, Wilson KL. C. elegans nuclear envelope proteins emerin, MAN1, lamin, and nucleoporins reveal unique timing of nuclear envelope breakdown during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3089–99. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee KK, Starr D, Cohen M, Liu J, Han M, Wilson KL, et al. Lamin-dependent localization of UNC-84, a protein required for nuclear migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:892–901. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-06-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson DJ, Hetzer MW. Reshaping of the endoplasmic reticulum limits the rate for nuclear envelope formation. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:911–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anderson DJ, Hetzer MW. Nuclear envelope formation by chromatin-mediated reorganization of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1160–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Antonin W, Ellenberg J, Dultz E. Nuclear pore complex assembly through the cell cycle: regulation and membrane organization. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2004–16. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]