Abstract

Cytoskeleton-mediated transport processes are central to the subcellular organization of cells. The nucleus constitutes the largest organelle of a cell, and studying how it is positioned and moved around during various types of cell morphogenetic processes has puzzled researchers for a long time. Now, the molecular architectures of the underlying dynamic processes start to reveal their secrets.

In yeast, karyogamy denotes the migration of two nuclei toward each other—termed nuclear congression—upon partner cell mating and the subsequent fusion of these nuclei to form a diploid nucleus. It constitutes a well-studied case. Recent insights completed the picture about the molecular processes involved and provided us with a comprehensive model amenable to quantitative computational simulation of the process. This review discusses our understanding of yeast nuclear congression and karyogamy and seeks to explain how a detailed, quantitative and systemic understanding has emerged from this knowledge.

Keywords: yeast mating, spindle pole body, karyogamy, nuclear migration, microtubule dynamics, kinesin-14, Kar3, yeast cell morphogenesis, microtubule motor protein, nuclear fusion

Introduction

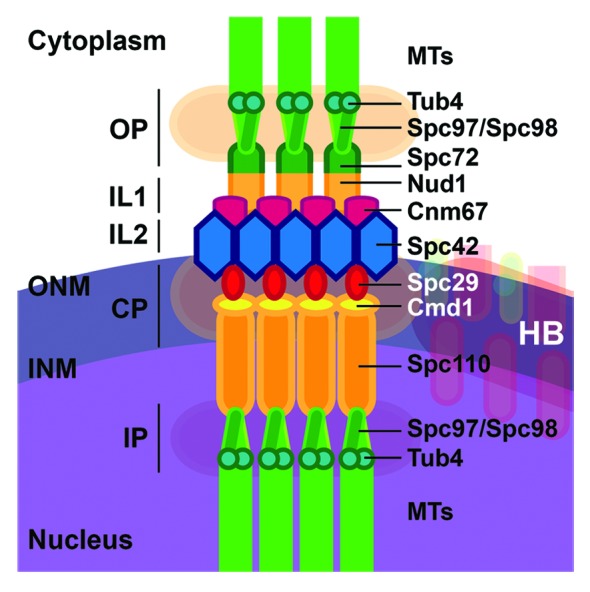

Nuclear migration processes are major cellular events associated with particular live cycle stages or specific cellular differentiation processes in many eukaryotes.1-3 In the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, nuclear migration is crucial during mitosis to orient the mitotic spindle toward the bud and move the nucleus into the bud neck.4 During mating of haploid cells, it also enables the two nuclei of the mating partners to meet and subsequently to engage in a cascade of molecular events that lead to the fusion of the nuclei and the formation of diploid cells.5 Understanding this process and the underlying molecular mechanisms became early of interest to cell biologists because of its central role in the live cycle of this species and because it was amenable to electron microscopy (EM) studies and genetic screens. In particular, the EM work of Byers and Goetsch6 shed central insights into the hierarchy of events that accompanies cell mating. From this work, it became clear that the microtubule (MT) organizing centers, the so-called spindle pole bodies (SPB; Figure 1), take a lead in the transport processes that guide the nuclei of the mating partners toward each other and that, associated with nuclear fusion, the SPBs also fuse to form the so-called “fusion plaque”. Nonetheless, it was only when molecular biology techniques enabled cloning of the genes from kar-mutants (for karyogamy mutants), that insights into the underlying molecular machinery was gained.7-11 This had a rich influence on the study of various cellular processes, from functions of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (e.g., Kar2, the yeast homolog of the major ER chaperonin BIP),12 to transcriptional regulation (Kar4),13 SPB biology (Kar1)8 and molecular motor proteins (Kar3),14 all of which suggested a highly coordinated set of molecular processes leading to nuclear fusion. Our recent work has now closed a gap in the understanding of how some of these molecules cooperate in order to physically move the nuclei together. This work placed Spc72, a molecule of the outer plaque and the half-bridge of the SPB (Fig. 1) into a central position for MT organization during mating. It revealed that Spc72, which binds the minus ends of MTs15 also functions as platform for the molecular motor Kar3, a minus end-directed Kinesin-14.16 Spc72 itself is anchored to a lateral appendage of the SPB, the so-called half-bridge, via its interaction with Kar1.17 Incorporation our new findings into previous work, now outlines the structural and regulatory processes that lead to the specific MT organization and provide the driving forces underling nuclear congression. In this review, we will describe these molecular events and how they cooperate to functionalize MTs, and we will conclude by discussing open questions for future research. Because the process of nuclear membrane and SPB fusion, although very interesting, constitutes another topic, we will not discuss it in detail here.

Figure 1. Protein composition of yeast microtubule organizing center, the SPB. Known proteins of the SPB are displayed and thus illustrate the composition of the different plaques (Outer plaque, OP; Central plaque, CP; Inner plaque, IP) and the two inner layers (IL1&2). ONM: Outer nuclear membrane, INM: inner nuclear membrane. The structure of the half-bridge (HB) is detailed in Figure 3A. Schematic adapted from a review by Jaspersen and Winey52 where the structure, duplication, and functions of the SPB are extensively described.

Initiation of Mating and Preparation for Nuclear Congression

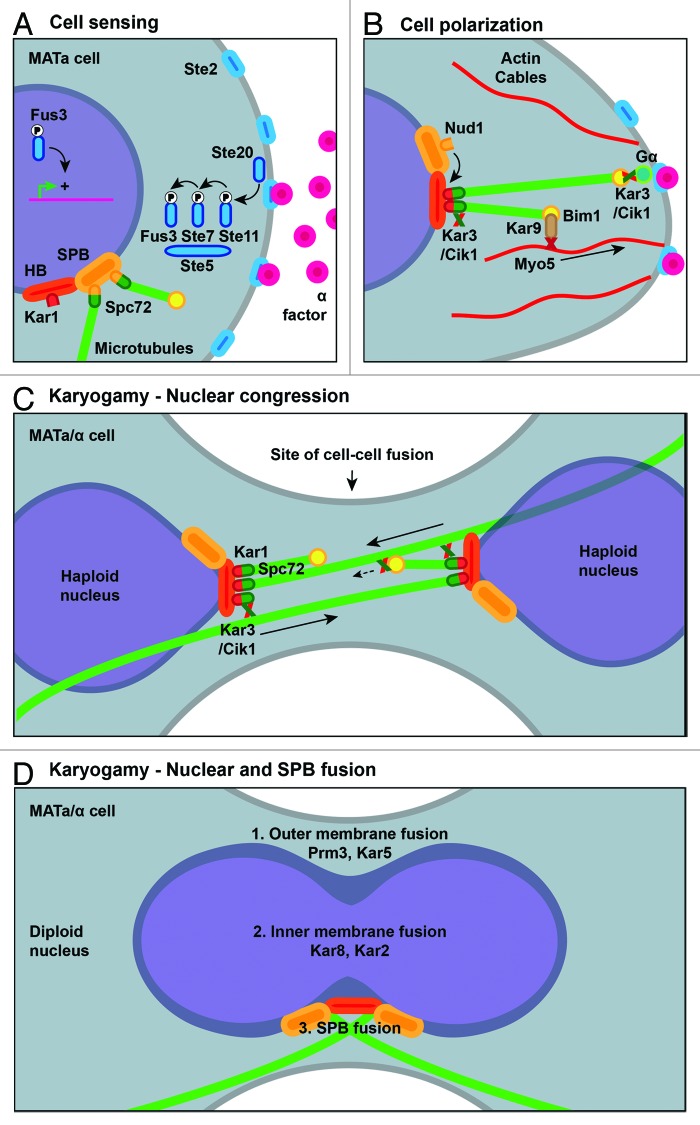

Mating is initiated by the response of a cell to the mating pheromone of a nearby partner of opposite mating type. By means of a canonical mitogen associated protein (MAP) kinase pathway, various activities are triggered that lead to a cell cycle arrest in G1, establishment of cell polarity and the upregulation of genes required to execute the mating program (Fig. 2A). Here, actin cable-mediated guiding via MT tip proteins Kar9 and Bim1, with the help of the actin motor Myo5 directs MTs toward the site of polarity, the shmoo tip. The heterodimeric MT minus end-directed motor Kar3/Cik1 at MT plus ends establishes interactions with the Gα protein Gpa1 at the shmoo tip,18 promoting the persistent interaction of MTs at the cortex. Especially, this cortical interaction is maintained during MT shortening,19,20 thus effectively pulling the nucleus toward the incipient fusion site at the tip of the shmoo tip (Fig. 2B). After cell fusion and the formation of a physical connection between the cells, MTs rapidly grow into the cytoplasm of the mating partner and nuclear congression is initiated upon a short often hardly noticeable lag phase of up to 1 min. Consequently, proteins regulating MT dynamics, e.g., Bik1 or Bim1, which both are required for normal amounts and lengths, by means of regulation of MT polymerization/depolymerization,21-23 are essential for mating, as are certain mutant alleles of tubulin itself.24 This is presumably because increased MT-catastrophes prevent persistent interactions between the mating nuclei and thus fail to promote full congression in an efficient manner.25

Figure 2. A cascade of cellular events triggered by distinct, but interconnected molecular systems, is required for mating and nuclear fusion. (A) Stimulation by mating pheromone (here, α-factor in the case of a MATa cell) of the G protein-coupled seven-transmembrane receptor Ste2 leads to the activation of the pheromone MAP kinase signaling pathway, consisting of the scaffold protein Ste5 and the three canonical MAP kinases Ste11, Ste7 and Fus3. Fus3 regulates a number of cytoplasmic proteins and nuclear transcriptional regulators, thereby triggering cell cycle arrest and the expression of factors needed for mating. Prior the activation of the mating program and cell polarization, MTs are anchored at the SPB, through the interaction of the γ-tubulin receptor Spc72 with the SPB protein Nud1. (B) Upon pheromone stimulation, MTs are relocated from the SPB to the half-bridge (HB) via the interaction of Spc72 with Kar1. Concomitantly, Myo2 linked to the MT plus end-tracking protein Bim1 through the adaptor protein Kar9 moves MTs along polarized actin cables and therefore orients the nucleus toward the shmoo tip. At the shmoo tip, the MT plus ends interact persistently via the interaction of plus end-located Kar3 with the Gα subunit of the Ste2 receptor. Simultaneously, a mating specific cytoplasmic Cik1 form is expressed, heterodimerizes with Kar3 and binds to Spc72. (C) After cell-cell fusion, MTs protrude into the cytoplasm of the mating partner. When they reach the opposite SPB, they interact with Spc72-anchored Kar3 and the congression of the haploid nuclei starts. Possibly, MT plus end-located Kar3 interacts transiently with MTs from the mating partner to guide the MTs before they reach the opposite SPB. (D) When the two nuclei become close enough, nuclear and SPB fusion is initiated in a three-step pathway. First, the outer nuclear membrane fuses, initiated by Prm3 and facilitated by Kar5. In a second step, the inner nuclear membrane fuses using Kar2 and Kar8. Only finally is the SPB fusion occurring (for more details about nuclear and SPB fusion see refs.53,54).

Molecular Organization of MT-SPB Attachment in Mating

The budding yeast S. cerevisiae undergoes enclosed mitosis (i.e., the nuclear envelope never breaks down) and the SPB constitutes the sole center for MT organization. The SPB remains embedded in the nuclear envelope throughout all life cycle stages of this species, thereby providing the platform that connects the MTs of both the cytoplasmic and the nuclear compartments.6,26 On each side of the SPB, specialized proteins characterized by central coiled coil domains anchor the minus ends of MTs via direct interaction with the γ-tubulin complex—Spc110 on the nuclear side27 and Spc72 on the cytoplasmic side (Fig. 1).28,29 On the cytoplasmic side, the interaction of Spc72 with the core structures of the SPB is subject to regulation. During most of the mitotic stages, Spc72 and with it the MTs are anchored to the outer plaque of the SPB via the binding of Spc72 to Nud1 (Fig. 1), a structural component of the SPB30 with additional regulatory function as a scaffolding molecule for cell cycle regulators.31 Nud1 itself is anchored to the central plaque of the SPB via binding to Cnm67 (Fig. 1). Two observations suggested that Spc72 binding to the SPB is differently organized in mating: cnm67Δ mutants defective in Nud1 and therefore also in MT anchorage to the SPB outer plaque retained their ability to properly organize MTs during mating.32 Thereby, the MTs are attached not to the outer plaque of the SPB but to the half-bridge, a lateral extension of the SPB also required for SPB duplication.26 Conversely, Rose and Fink identified in the kar1 screen the kar1–1 mutant with a unique unilateral mating defect – abrogation of nuclear fusion during mating if only one mating partner possesses the kar1–1 allele.7,8,33,34 Kar1 turned out to be an integral and nuclear membrane anchored component of the half-bridge35 with an additional and clearly separable function in SPB duplication and mitosis.8 In the unique mating specific kar1–1 allele, a specific loss of MT attachment to the SPB during mating was observed, whereas no MT attachment defect to the outer plaque of the SPB in mitosis was noticed.36 Localization of Spc72 and subsequent biochemical work then established that Kar1 anchors Spc72 together with the cytoplasmic MTs to the half-bridge during mating; a rearrangement that is initiated upon pheromone stimulation of the cell and is associated with the translocation of Spc72 from the outer plaque of the SPB to the half-bridge.17

Kar3/Cik1 Constitute the Motor Activity Underlying Nuclear Congression

Kar3 is a kinesin-14 homolog with a C-terminal motor domain that exhibits MT minus end-directed non-processive motor activity.37 It was identified as an essential factor for nuclear congression during mating14 with additional functions in mitosis.38 Two proteins with independent MT binding activity, Cik1 and its homolog Vik1, form distinct heterodimeric complexes with Kar3, with each distinct functions.39-41 Of these, the Kar3/Cik1 heterodimer is required for mating, where a mating-specific Kar3/Cik1 heterodimer is formed upon pheromone stimulation of yeast cells: Kar4-mediated transcriptional upregulation of Cik113 leads to the formation of an N-terminally shortened Cik1 by means of a shorter transcript and the use of an alternative Start codon,42 similar to the mating specific regulation of Kar4 itself.43 This shorter Cik1 lacks a nuclear localization signal (NLS) as well as an N-terminal signal for APC/CCdh1 mediated degradation of the protein after mitosis.41,42 Consequently, a stable cytoplasmic protein is formed upon pheromone signaling, which engages Kar3—itself also upregulated during mating—in a cytoplasmic function.

The precise role of Kar3 during nuclear congression and how it interacts to generate the necessary force for nuclear movements remained elusive for quite some time, as the in vitro and in vivo acquired data about Kar3 molecular functions and phenotypes enabled multiple interpretations. Based on the molecular functions of Kar3 as a minus end-directed motor protein with MT depolymerizing activity37 and a detected localization at both MTs and SPBs,14 Rose and coworkers suggested the so-called “sliding cross-bridge” model, where Kar3/Cik1, bound to antiparallel overlap zones between the cytoplasmic MTs from the two SPBs, would underlie force generation during congression.9 Simultaneously, the MT depolymerizing activity would ensure proper lengthening of the MTs when reaching the opposite SPB. Quantitative imaging of MTs in live cells 10 y later failed to detect clear indication of such MT overlap zones. This, and the observed localization of MT plus end trackers between the two SPBs, led to the proposal of a refined model, the “plus end” model, where MT plus end-localized Kar3 cross-links the plus ends of MTs from the opposite SPBs. Simultaneous movement and MT depolymerization would then pull the two SPBs toward each other.25 In both models, the detachment of MT minus end anchorage at one SPB of one of the mating partners is sufficient to disrupt nuclear congression completely. Although no direct experimental evidence was available, these models sufficiently explained the unilateral mating defect of the kar1–1 mutant, via its defect in Spc72 and therefore MT minus end binding to the half-bridge during mating.17 These models however implicated that forces underlying nuclear congression are generated at MT overlaps or interaction zones, for which experimental evidence, e.g., from in vitro reconstitutions was strikingly absent from literature, despite of the availability of working in vitro assays for Kar3 functions.37,38,44

Force Generation by SPB Half-Bridge Localized Kar3/Cik1

In contrast to what was proposed from the previous models, electron tomography failed to detect consistent direct MT-MT interactions between MTs from the SPBs of the mating partners.16 This suggested that the main forces underlying congression are generated by a new mecchanism that would not be primarily based on direct MT-MT interactions. Consecutive analysis then established that MTs nucleated from one SPB interact directly with Kar3/Cik1 localized to the half-bridge of the other SPB. Here, Spc72 serves as an anchor for the Kar3/Cik1 motor, and this Spc72-anchored pool of the motor was found to constitute the force generation motor fraction. Spc72 also serves as the anchor for MT minus ends, via an interaction with the γ-tubulin complex. Therefore, the following scenario appears as the likely mechanism how MTs are organized into a functional structure during mating: upon pheromone stimulation, Spc72 is released from the outer plaque of the SPB and subsequently captured at the SPB half-bridge, where it now attaches the cytoplasmic MTs. Simultaneously, a new cytoplasmic motor consisting of Kar3/Cik1 is assembled and also binds to Spc72, thus bringing MT minus end-directed motor activity directly to the minus end of anchored MTs (Fig. 2C).

This minimalistic MT organization is strikingly elegant. First, Kar3, when directly bound to the minus ends of MTs, is unable to exert forces on these MTs. Second, in a symmetric arrangement, where both SPBs provide MT minus end attachment sites and motor activity, this location is the best position to move the two SPBs as close as possible toward each other, while the same results will also be obtained if only an asymmetric MT arrangement is present, thus making the process very robust.

The mobile phase of congression lasts on average less than three minutes during which the nuclei converge about 2 µm. When reaching a distance of just below 1 µm congression is often paused, and the SPBs remain visible as clearly distinguishable entities for several minutes. Then suddenly they complete congression to form one entity. We noticed that Kar3, when forced to the outer plaque of the SPB (instead of the half-bridge) via direct fusion to the outer plaque component Cnm67 was well able to promote normal congression. In matings of these cells, however, the SPBs approached each other directly without noticeable pausing phase at the distance of approx.1 µm, and subsequent nuclear fusion appears to be impaired. From these observations we speculate that the reason why MTs are organized via the half-bridge serves to orient the SPBs properly before nuclear and subsequent SPB fusion. Thereby, the pausing phase before fusion would start when the half-bridges contact each other and its duration is probably associated with physical processes needed to initiate membrane and subsequent SPB fusion (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the Kar3-Cnm67 SPBs probably reach rapidly a face-to-face association, which could sterically prevent the subsequent steps.

This revised model for MT organization and force generation during nuclear congression (Fig. 2C and 3A) again is consistent with the unilateral kar1–1 phenotype, since also in this model the disruption of the Spc72/Kar1 interaction in one mating partner does completely abrogate MT organization at its SPB. In an experimental mating between a KAR1 wild type and a kar1Δ15 mutant, which is impaired in binding to Spc72 (similar to the kar1–1 mutant), the detached MTs of the kar1Δ15 cell now move with their minus end toward the SPB of the KAR1 wild type mating partner, thus confirming that a fully functional machinery capable to migrate along MTs toward their minus ends is attached via Spc72 at MT minus ends.

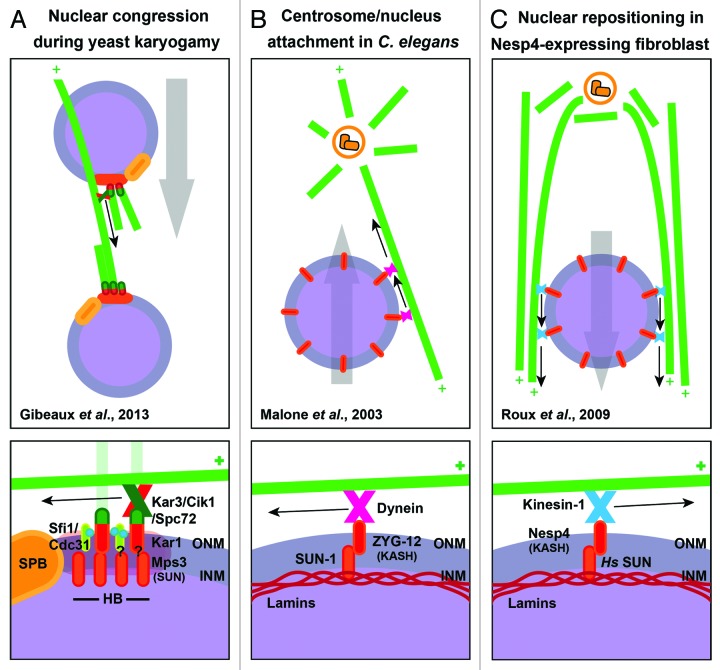

Figure 3. Comparison of nuclear migration mechanisms in yeast, C. elegans and in human cells. (A) Nuclear congression during yeast karyogamy (adapted from Gibeaux et al.16). The recruitment of the Kar3/Cik1 heterodimer to the half-bridge appendage of the SPB promotes the migration of the associated nucleus along the MTs nucleated from the partner nucleus (top). The Kar3/Cik1 heterodimer interacts with the cytoplasmic γ-tubulin receptor Spc72. Spc72 is recruited to the half-bridge through an interaction with Kar1. The half-bridge is composed of Kar1 and several other proteins including the Centrin-binding protein Sfi1, the Centrin-homolog Cdc31 and the SUN domain-containing protein Mps3. The whole half-bridge forms a lateral appendage to the SPB, which is a natural linker between the inner and outer side of the nucleus. Altogether, this allows the movement of the nucleus toward the minus ends of the MTs that are anchored at the opposite nucleus (bottom). (B) Centromere/nucleus attachment in C. elegans (adapted from Malone et al.45). The recruitment of Dynein to the nuclear envelope promotes the close association of the nucleus with the centrosome during the first steps of development in C. elegans (top). Dynein is recruited by the KASH domain-containing protein ZYG-12 integrated in the outer nuclear membrane. ZYG-12 interacts through its KASH domain with the SUN domain of SUN-1 that is integrated in the inner nuclear membrane. This SUN domain-containing protein interacts itself with the lamins in the nucleoplasm. Altogether, this promotes the movement of the nucleus toward the minus end of the MT array. (bottom). (C) Nuclear repositioning in Nesp4-expressing fibroblast (adapted from Roux et al.47). The recruitment of Kinesin-1 to the nuclear envelope in fibroblasts induces separation of the nucleus and centrosome (top). Kinesin-1 is recruited by the KASH domain-containing protein Nesprin-4 integrated in the outer nuclear membrane. Nesp4 interacts through its KASH domain with the SUN domain of Hs SUN that is integrated in the inner nuclear membrane. This SUN domain-containing protein interacts itself with the lamins in the nucleoplasm. Altogether, this promotes the movement of the nucleus toward the plus end of the MT array (bottom).

How MT growth is regulated immediately after cell-cell fusion remains however still unclear. One would expect that this is associated with a disruption of the binding of the conventional Kar3/Cik1 complex to the Gα protein Gpa1 at the shmoo, e.g., caused by the disruption of the machinery at the shmoo tip. Liberated MT plus ends would then be free to rapidly grow into the cytoplasm of the mating partner. Since the mating-specific Kar3/Cik1 binds to the half-bridge of SPBs already upon pheromone stimulation (via translocated Spc72), these MTs, when reaching the area of the opposite SPB, can be rapidly captured and the nuclei can start to congress. From the time point of cell fusion, this process takes less than 30‒60 sec to initiate, probably aided by the fact that the forces exerted by one SPB on one incoming MT are sufficient to initiate congression. Interestingly, using stochastic simulations of the process, we observed that this initial phase is significantly longer, if we do omit MT plus end bound Kar3/Cik1, giving rise to the speculation that this pool of Kar3 motor could aid proper guidance, along opposite cytoplasmic MTs, of the growing MTs before they reach the opposite SPB, and by this could facilitate efficient progression into the congression phase. Indeed, the Kar3-Cnm67 cells that contained Kar3 only at the SPB, did exhibit a pronounced lengthening of this initial phase, whereas congression itself proceeded with normal speed. This argues for an auxiliary role of MT plus end-localized Kar3/Cik1 to help finding the opposite SPB, whereas—at least in our simulation—this was not sufficient to promote nuclear congression. In Addition, it is difficult to imagine how MT-MT interactions alone would be sufficient to complete congression, as the final convergence of the SPBs would only be permitted upon complete depolymerization of the MTs, in which case Kar3 could not function any more. Nevertheless, to decisively understand the importance of direct MT-MT interactions, and whether they play auxiliary roles or serve as a backup, maybe partially redundant mechanism, it is required to map the Kar3/Cik1 binding site at Spc72. The specific abrogation of this interaction will then allow to investigate directly the role of SPB localized Kar3 as well as the other functions of Kar3 during congression.

Conclusions

This basic mechanism how MTs are organized during nuclear congression in yeast exhibits striking structural similarity to the nuclear migration processes in other species. In all cases investigated so far (see examples provided in Fig. 3) attachment of a motor to a nucleus requires that the motor is not only anchored to the nucleus via binding to the membrane, but it seems to require interactions with bridging structures. In C. elegans, Drosophila as well as human cells, for instance, this is achieved via SUN- and KASH-domain containing proteins that, by interacting together, bridge the gap between the two lipid bilayers of the nuclear envelope and establish contact with the lamin network beneath the surface of the nuclear envelope (Fig. 3B and C).45-47 In yeast, the SPB constitutes a linker between the inner and outer side of the nucleus, and in the light of absent nuclear lamins, constitutes the natural anchor for a motor in order to maneuver it along a cytoplasmic structure. Interestingly, the half-bridge protein Mps3 belongs to the family of the SUN proteins,48 which could fuel speculations about the evolutionary origin of this SPB appendage (Fig. 3A). The type of motor used to promote nuclear movements seems however to vary between species and cell types. While a minus end-directed kinesin-14 is required for nuclear congression in yeast (Fig. 3A), a MT plus end-directed kinesin-1 was found to guide the nucleus away from the centrosome in human cells (Fig. 3C). Dynein in contrast is used to bring the nucleus toward the centrosome in C. elegans (Fig. 3B). In zebrafish, congression of the female centrosome-free pronucleus along the astral MTs from the male pronuclear centrosome is mediated by maternally expressed Lrmp, the likely linker between the nucleus and the dynein/dynactin motor.49,50 From these examples and the several others described in literature (For a review see Starr and Fridolfsson, 201051), it appears evident that various types of nucleus-cytoskeleton interactions have evolved to fulfill particular needs, irrespective of the cytoskeletal structure used (actin, MTs or intermediate filaments), with the sole unifying principle to bring an anchor or motor activity directly to the object that needs to control its spatial position—the nucleus.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/25021

References

- 1.Reinsch S, Gönczy P. Mechanisms of nuclear positioning. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2283–95. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.16.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris NR. Nuclear positioning: the means is at the ends. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:54–9. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke B, Roux KJ. Nuclei take a position: managing nuclear location. Dev Cell. 2009;17:587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson CG, Bloom KS. Dynamic microtubules lead the way for spindle positioning. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:481–92. doi: 10.1038/nrm1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurihara LJ, Beh CT, Latterich M, Schekman R, Rose MD. Nuclear congression and membrane fusion: two distinct events in the yeast karyogamy pathway. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:911–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byers B, Goetsch L. Behavior of spindles and spindle plaques in the cell cycle and conjugation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:511–23. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.511-523.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conde J, Fink GR. A mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective for nuclear fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3651–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose MD, Fink GR. KAR1, a gene required for function of both intranuclear and extranuclear microtubules in yeast. Cell. 1987;48:1047–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose MD. Nuclear fusion in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:663–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polaina J, Conde J. Genes involved in the control of nuclear fusion during the sexual cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;186:253–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00331858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose MD, Price BR, Fink GR. Saccharomyces cerevisiae nuclear fusion requires prior activation by alpha factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3490–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.10.3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose MD, Misra LM, Vogel JP. KAR2, a karyogamy gene, is the yeast homolog of the mammalian BiP/GRP78 gene. Cell. 1989;57:1211–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurihara LJ, Stewart BG, Gammie AE, Rose MD. Kar4p, a karyogamy-specific component of the yeast pheromone response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3990–4002. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meluh PB, Rose MD. KAR3, a kinesin-related gene required for yeast nuclear fusion. Cell. 1990;60:1029–41. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90351-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knop M, Pereira G, Schiebel E. Microtubule organization by the budding yeast spindle pole body. Biol Cell. 1999;91:291–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibeaux R, Politi AZ, Nédélec F, Antony C, Knop M. Spindle pole body-anchored Kar3 drives the nucleus along microtubules from another nucleus in preparation for nuclear fusion during yeast karyogamy. Genes Dev. 2013;27:335–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.206318.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira G, Grueneberg U, Knop M, Schiebel E. Interaction of the yeast gamma-tubulin complex-binding protein Spc72p with Kar1p is essential for microtubule function during karyogamy. EMBO J. 1999;18:4180–95. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaichick SV, Metodiev MV, Nelson SA, Durbrovskyi O, Draper E, Cooper JA, et al. The mating-specific Galpha interacts with a kinesin-14 and regulates pheromone-induced nuclear migration in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2820–30. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sproul LR, Anderson DJ, Mackey AT, Saunders WS, Gilbert SP. Cik1 targets the minus-end kinesin depolymerase kar3 to microtubule plus ends. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1420–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maddox PS, Stemple JK, Satterwhite LL, Salmon ED, Bloom KS. The minus end-directed motor Kar3 is required for coupling dynamic microtubule plus ends to the cortical shmoo tip in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1423–8. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blake-Hodek KA, Cassimeris L, Huffaker TC. Regulation of microtubule dynamics by Bim1 and Bik1, the budding yeast members of the EB1 and CLIP-170 families of plus-end tracking proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2013–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz K, Richards K, Botstein D. BIM1 encodes a microtubule-binding protein in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:2677–91. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berlin V, Styles CA, Fink GR. BIK1, a protein required for microtubule function during mating and mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, colocalizes with tubulin. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2573–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huffaker TC, Thomas JH, Botstein D. Diverse effects of beta-tubulin mutations on microtubule formation and function. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:1997–2010. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molk JN, Salmon ED, Bloom KS. Nuclear congression is driven by cytoplasmic microtubule plus end interactions in S. cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:27–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byers B, Goetsch L. Duplication of spindle plaques and integration of the yeast cell cycle. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1974;38:123–31. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1974.038.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knop M, Schiebel E. Spc98p and Spc97p of the yeast gamma-tubulin complex mediate binding to the spindle pole body via their interaction with Spc110p. EMBO J. 1997;16:6985–95. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knop M, Schiebel E. Receptors determine the cellular localization of a gamma-tubulin complex and thereby the site of microtubule formation. EMBO J. 1998;17:3952–67. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Usui T, Maekawa H, Pereira G, Schiebel E. The XMAP215 homologue Stu2 at yeast spindle pole bodies regulates microtubule dynamics and anchorage. EMBO J. 2003;22:4779–93. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott S, Knop M, Schlenstedt G, Schiebel E. Spc29p is a component of the Spc110p subcomplex and is essential for spindle pole body duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6205–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruneberg U, Campbell K, Simpson C, Grindlay J, Schiebel E. Nud1p links astral microtubule organization and the control of exit from mitosis. EMBO J. 2000;19:6475–88. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brachat A, Kilmartin JV, Wach A, Philippsen P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells with defective spindle pole body outer plaques accomplish nuclear migration via half-bridge-organized microtubules. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:977–91. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.5.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dutcher SK. Internuclear transfer of genetic information in kar1-1/KAR1 heterokaryons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1981;1:245–53. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutcher SK, Hartwell LH. Genes that act before conjugation to prepare the Saccharomyces cerevisiae nucleus for caryogamy. Cell. 1983;33:203–10. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spang A, Courtney I, Grein K, Matzner M, Schiebel E. The Cdc31p-binding protein Kar1p is a component of the half bridge of the yeast spindle pole body. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:863–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vallen EA, Hiller MA, Scherson TY, Rose MD. Separate domains of KAR1 mediate distinct functions in mitosis and nuclear fusion. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:1277–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.6.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endow SA, Kang SJ, Satterwhite LL, Rose MD, Skeen VP, Salmon ED. Yeast Kar3 is a minus-end microtubule motor protein that destabilizes microtubules preferentially at the minus ends. EMBO J. 1994;13:2708–13. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Middleton K, Carbon J. KAR3-encoded kinesin is a minus-end-directed motor that functions with centromere binding proteins (CBF3) on an in vitro yeast kinetochore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7212–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page BD, Snyder M. CIK1: a developmentally regulated spindle pole body-associated protein important for microtubule functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1414–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page BD, Satterwhite LL, Rose MD, Snyder M. Localization of the Kar3 kinesin heavy chain-related protein requires the Cik1 interacting protein. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:507–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manning BD, Barrett JG, Wallace JA, Granok H, Snyder M. Differential regulation of the Kar3p kinesin-related protein by two associated proteins, Cik1p and Vik1p. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1219–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benanti JA, Matyskiela ME, Morgan DO, Toczyski DP. Functionally distinct isoforms of Cik1 are differentially regulated by APC/C-mediated proteolysis. Mol Cell. 2009;33:581–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gammie AE, Stewart BG, Scott CF, Rose MD. The two forms of karyogamy transcription factor Kar4p are regulated by differential initiation of transcription, translation, and protein turnover. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:817–25. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allingham JS, Sproul LR, Rayment I, Gilbert SP. Vik1 modulates microtubule-Kar3 interactions through a motor domain that lacks an active site. Cell. 2007;128:1161–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malone CJ, Misner L, Le Bot N, Tsai MC, Campbell JM, Ahringer J, et al. The C. elegans hook protein, ZYG-12, mediates the essential attachment between the centrosome and nucleus. Cell. 2003;115:825–36. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kracklauer MP, Banks SML, Xie X, Wu Y, Fischer JA. Drosophila klaroid encodes a SUN domain protein required for Klarsicht localization to the nuclear envelope and nuclear migration in the eye. Fly (Austin) 2007;1:75–85. doi: 10.4161/fly.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roux KJ, Crisp ML, Liu Q, Kim D, Kozlov S, Stewart CL, et al. Nesprin 4 is an outer nuclear membrane protein that can induce kinesin-mediated cell polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2194–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808602106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jaspersen SL, Martin AE, Glazko G, Giddings TH, Jr., Morgan G, Mushegian A, et al. The Sad1-UNC-84 homology domain in Mps3 interacts with Mps2 to connect the spindle pole body with the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:665–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindeman RE, Pelegri F. Localized products of futile cycle/lrmp promote centrosome-nucleus attachment in the zebrafish zygote. Curr Biol. 2012;22:843–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen PA, Ishihara K, Wühr M, Mitchison TJ. Pronuclear migration: no attachment? No union, but a futile cycle! Curr Biol. 2012;22:R409–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Starr DA, Fridolfsson HN. Interactions between nuclei and the cytoskeleton are mediated by SUN-KASH nuclear-envelope bridges. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:421–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaspersen SL, Winey M. The budding yeast spindle pole body: structure, duplication, and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.022003.114106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melloy P, Shen S, White E, McIntosh JR, Rose MD. Nuclear fusion during yeast mating occurs by a three-step pathway. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:659–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melloy P, Shen S, White E, Rose MD. Distinct roles for key karyogamy proteins during yeast nuclear fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3773–82. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]