Abstract

Duplicated ribosomal protein (Rp) gene families often encode highly similar or identical proteins with redundant or unique roles. Eukaryotic-specific paralogues RpL22e and RpL22e-like-PA are structurally divergent within the N terminus and differentially expressed, suggesting tissue-specific functions. We previously identified RpL22e-like-PA as a testis Rp. Strikingly, RpL22e is detected in immunoblots at its expected molecular mass (m) of 33 kD and at increasing m of ~43–55 kD, suggesting RpL22e post-translational modification (PTM). Numerous PTMs, including N-terminal SUMOylation, are predicted computationally. Based on S2 cell co-immunoprecipitations, bacterial-based SUMOylation assays and in vivo germline-specific RNAi depletion of SUMO, we conclude that RpL22e is a SUMO substrate. Testis-specific PTMs are evident, including a phosphorylated version of SUMOylated RpL22e identified by in vitro phosphatase experiments. In ribosomal profiles from S2 cells, only unconjugated RpL22e co-sediments with active ribosomes, supporting an extra-translational role for SUMOylated RpL22e. Ectopic expression of an RpL22e N-terminal deletion (lacking SUMO motifs) shows that truncated RpL22e co-sediments with polysomes, implying that RpL22e SUMOylation is dispensable for ribosome biogenesis and function. In mitotic germ cells, both paralogues localize within the cytoplasm and nucleolus. However, within meiotic cells, phase contrast microscopy and co-immunohistochemical analysis with nucleolar markers nucleostemin1 and fibrillarin reveals diffuse nucleoplasmic, but not nucleolar RpL22e localization that transitions to a punctate pattern as meiotic cells mature, suggesting an RpL22e role outside of translation. Germline-specific knockdown of SUMO shows that RpL22e nucleoplasmic distribution is sensitive to SUMO levels, as immunostaining becomes more dispersed. Overall, these data suggest distinct male germline roles for RpL22e and RpL22e-like-PA.

Keywords: RpL22e, RpL22e-like-PA, Drosophila, ribosomal protein paralogues, duplicated ribosomal proteins, SUMOylation, phosphorylation, post-translational modification, male germline

Introduction

Duplicated ribosomal protein (Rp) genes are prominent features of yeast, plant and fly genomes. Many highly similar or identical Rp genes (demonstrated most notably in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in Arabidopsis thaliana) appear to encode paralogues with functionally-distinct roles in several cellular, molecular or developmental pathways in response to different environmental cues.1-3 These discoveries have stimulated an interest in determining if ribosome heterogeneity, in this case defined by Rp paralogue interchangeability, has an impact on translational regulation capacity (for a review see ref. 4). Differences in rRNA composition, tissue-specific expression of Rp paralogues and Rp post-translational modifications (PTMs) also contribute to ribosome heterogeneity and may broaden the translational regulatory spectrum in cells under certain physiological conditions.

Noteworthy is the fact that some Rps perform extra-ribosomal functions in addition to their roles in translation (for a review see ref. 5). Certainly through the course of evolution, a duplicated Rp paralogue may have acquired a new role distinct from its presumed original canonical role as a structural component of the ribosome. Notwithstanding the acquisition of a new function, some degree of functional redundancy between Rp paralogues might also have been retained.

Given that different functional roles have often been attributed to structurally similar paralogues, it is reasonable to propose that disparate functions could be ascribed to structurally dissimilar paralogues, particularly in instances where tissue-specific expression patterns accompany paralogue structural divergence. The conserved eukaryotic-specific RpL22e family in Drosophila melanogaster represents a model protein family whose structurally divergent members may have evolved disparate functions.

The fly RpL22e family includes two genes, rpL22 and rpL22-like, hereafter included with an “e” designation to signify the gene and products as “eukaryotic-specific” and not homologous to bacterial rpL22. A single protein product was previously annotated for each gene, but recent evidence demonstrates that the rpL22e-like gene is alternatively spliced, giving rise to two protein products, “RpL22e-like-PA” (previously called “RpL22-like-full”) and a novel protein isoform, previously called “RpL22-like short,” but renamed in Flybase.org as “RpL22e-like-PB.”6 Previous work by others determined that rpL22e-like mRNA is expressed in embryonic and adult gonads and germline cells (gonads, primordial germ cells [PGCs], adult ovary germline stem cells [GSCs] and in adult testes, but not adult ovary from microarray analyses).7-10 On the other hand, RpL22e is ubiquitously expressed in embryos and adults.7,8 With paralogue-specific antibodies (Abs), we determined that RpL22e-like-PA is expressed in a tissue-specific manner, found only in germ cells in adult testes and in fly heads of both sexes.6 Thus the gonadal protein expression pattern aligned well with previously reported mRNA expression patterns.

Well established as a 60S ribosomal subunit protein, RpL22e is only 37% identical in amino acid (aa) sequence to RpL22e-like-PA.11,12 Both proteins share a Rp signature with rRNA binding motifs (as defined for human RpL22e) at the C-terminal end.13 Our previous ribosomal profile analyses confirm as well that within the testis, RpL22e-like-PA is found in ribosomes and in polysomes, though other possible functions cannot be excluded at this time.6 A fly-specific N-terminal extension (of unknown function) with homology to the C-terminal end of histone H1 (previously described only for RpL23a and RpL22e by Koyama et al.) is clearly the most divergent structural feature between the two proteins.14 Therefore, any potential functional differences between these proteins might be mediated through interactions in the N-terminal domain.

In the male reproductive system of the fly, RpL22e is expressed in the testis, accessory gland, seminal vesicle and the ejaculatory duct. RpL22e-like-PA is only expressed within germ cells throughout spermatogenesis; therefore, RpL22e paralogues are co-expressed within germ cells.6 The significance of an overlapping expression pattern within germ cells has yet to be uncovered.

In the testis and in other tissues, we previously discovered additional immunoreactive species (using paralogue-specific Abs) at a higher molecular mass (m) of ~50 kD than would be predicted (33 kD) for RpL22e.6 In the testis, RpL22e-like-PA was detected at its predicted m of 34 kD, with no indication of stable higher m species. We hypothesized that the higher m, SDS-resistant species might represent post-translationally modified RpL22e.6 If so, an array of RpL22e PTMs sufficient to account for a minimum m differential of ~20 kD would have to be proposed. In the current study PTMs are examined to evaluate m differences among RpL22e species detected by immunoblot. In the male germline where both paralogues are co-expressed, PTM of RpL22e, but not of RpL22e-like-PA would further distinguish these paralogues not only structurally, but most likely functionally as well. Such a distinction in PTM between Rp paralogues would bring to the forefront a new mechanism not widely explored as a means to regulate paralogue functions within the same cell.

Numerous examples of Rps serving as substrates for PTM machinery for methylation, acetylation, ubiquitylation, addition of O-linked β-D-N-acetylglucosamine, phosphorylation and SUMOylation have been described (for a brief review of this subject overall see ref. 4; see ref. 15 for SUMOylation). Much remains to be uncovered about the importance of PTMs in controlling the dynamics of ribosome assembly (for a review see ref. 16) and in altering Rp function in translation or in other cellular pathways. Modification of eukaryotic Rps in the context of the ribosome adds a layer of translational regulation that has stimulated numerous lines of investigation (for a PTM review of mitochondrial Rps see ref. 17.; for a Rp PTM review see ref. 4) and in some instances, an impact on translation has been documented, albeit mechanistically not fully understood.18 A notable example is that incorporation of polyubiquinated RpL28 (a component of the peptidyl transferase center) into ribosomes may have a stimulatory effect on translation.19

PTMs of some Rps may be significant in defining extra-ribosomal roles for these proteins; for example, regulated phosphorylation of RpS6 affects cell size and glucose metabolic regulation in murine cells but does not affect mRNA translational control.20 Further, for RpS3, the DNA repair activities and the most recently described regulatory activities affecting mitotic spindle dynamics appear to be controlled by PTMs that include regulated phosphorylation as well as SUMOylation.21-27

For RpL22e and RpL22e-like-PA, little is known about PTMs, with a few exceptions for RpL22e. RpL22e is a substrate for casein kinase II with phosphorylation sites located at the C-terminal end.28 Previous proteomics studies have identified numerous Rps as SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) targets, implicating involvement of the SUMOylation pathway in ribosome assembly or in the degradation of unassembled Rps.15,29-31 RpL22e was identified as a possible SUMOylation substrate based on its recovery in a complex containing multiple SUMO substrates; however, no definitive evidence that RpL22e itself is a target of SUMOylation has as yet been reported.29 SUMO, encoded by smt3 (a single gene in Drosophila), is a reversible protein modifier of ~10 kD that can be added as a single entity or in multiples to acceptor lysines in protein targets through a series of enzymatic reactions (for a review see ref. 32). The addition of SUMO chains to RpL22e could account for m differences previously observed.6

Computational analyses to predict conserved recognition motifs within proteins reveal a putative strong SUMOylation site within RpL22e and RpL22e-like-PA located within the N-terminal domain but at a different location within each paralogue (Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource for Functional Sites in Proteins; http://elm.eu.org/). It is known that SUMOylation can impact subcellular localization, activity and/or stability of modified substrates by altering intra- or intermolecular protein interactions.32 Further, the SUMOylation pathway is critical at multiple stages of spermatogenesis in several species, including Drosophila (for a review see ref. 33).

Together with the detection of higher m immunoreactive RpL22e species with paralogue-specific, peptide-derived Abs,6 computational predictions of a SUMO motif within the N-terminal region of RpL22e and proteomics evidence for association of RpL22e in complexes with other SUMO substrates,29 we propose that RpL22e is a SUMO substrate. To investigate this possibility, we use a combination of biochemical, molecular and genetic approaches that included co-immunoprecipitations from S2 cells using anti-SUMO and anti-RpL22e Abs, a bacterial-based SUMOylation assay and in vivo germline-specific RNAi depletion of SUMO. Another goal was to determine if high m immunoreactive RpL22e species associate with 60S subunits, 80S monosomes and/or polysomes in ribosome profiles from S2 cells. Such an association would support involvement in translation. On the other hand, lack of co-sedimentation with ribosomal components would favor involvement in extra-translational pathways. Further, using immunohistochemistry (IHC) we refine the cellular and subcellular localization patterns for both paralogues in the male reproductive tract, previously described by Kearse et al.6 Collectively, these investigations provide insights into mechanistic processes that specify RpL22e paralogue functions within the testis.

Results

RpL22e is differentially post-translationally modified in different tissues

We have previously reported the tissue- and sex- specific expression of the duplicated member of the RpL22e family, RpL22e-like-PA.6 In the adult testis, RpL22e-like-PA protein is detected at its predicted m of 34 kD and has an electrophoretic pattern identical to recombinant protein. However, we noted that the ubiquitously expressed RpL22e was detected predominantly at an m of ~50 kD, greater than its predicted m of 33 kD. Here we further refine this observation by characterizing RpL22e in various tissues and show evidence for RpL22e PTM.

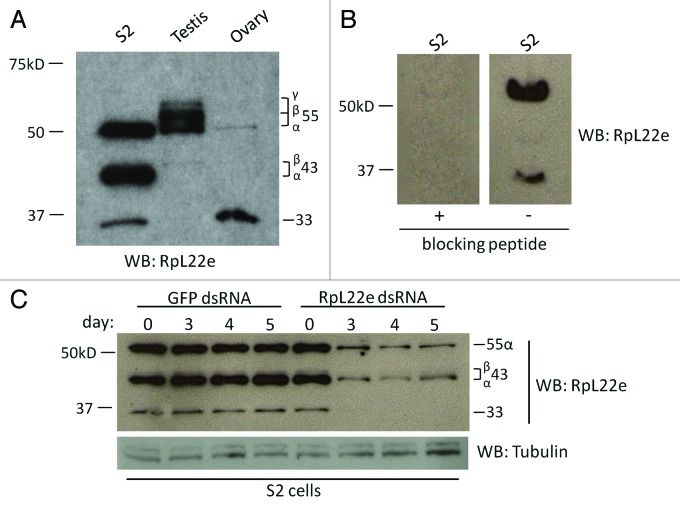

Comparing RpL22e electrophoretic patterns between Drosophila S2 tissue culture cells and adult gonads, m variation in accumulating proteins is seen in the ~33–55 kD range (Fig. 1A). To facilitate protein comparative analysis, we established a protein nomenclature based on the approximate observed m. The predicted m of RpL22e based on the annotated coding sequence is 33 kD and is seen in all tissues. Two additional proteins, designated 43α and 43β, accumulate at varying amounts at the ~43 kD range in S2 cells, ovaries, as well as in testes. The 43 kD proteins accumulate at varying amounts not only in different tissues/cells (compare S2 cells with testis and ovary) but also within different samples from the same cell type (compare S2 cells in Figures 1A−C; Fig. S1). The amounts of these particular species were consistently variable and may indicate that the 43 kD products are less stable modification pathway intermediates that fluctuate with metabolic state. Immunoreactive proteins migrating in the ~55 kD range are also evident, with 55α present in all tissues examined. Interestingly, testis tissue contains two additional immunoreactive proteins, designated 55β and 55γ. Western analysis of accessory glands (removed during testes dissections) suggests 55β and 55γ are testis-specific RpL22e species within the male reproductive tract (Fig. S1). Furthermore, comparison of RpL22e immunodetection patterns between whole testis tissue and isolated apical tip tissue suggests that 55γ is restricted to mature post-mitotic spermatocytes (Fig. S2). The absence of these species from ovary and S2 cells (this report) as well as from salivary glands and head tissue6 suggests that these species may indeed be unique to testis tissue.

Figure 1. RpL22e is detected at higher m in multiple Drosophila tissues. (A) Using a peptide-derived polyclonal antibody, RpL22e is detected in S2 tissue culture cells, testis and ovary tissue at its predicted m of 33 kD, but also at increasing m, designated as 43α,β and 55α,β,γ (increasing m of ~43 kD and ~55 kD). (B) Peptide inhibition experiments confirm specificity of polyclonal antibody. (C) Immunodetection of 33 kD RpL22e, as well as novel slower migrating species (43α,β and 55α) is reduced in S2 cells via RNAi by incubation of dsRNA targeting codons 1–100 of RpL22e, but not by targeting GFP (negative control). Tubulin was used as a loading control.

Initially, to confirm higher m proteins as bona fide RpL22e gene products, we first performed pre-immune (see ref. 6) and then peptide inhibition experiments (Fig. 1B). When anti-RpL22e polyclonal Ab was pre-incubated with a blocking peptide (a C-terminal peptide originally used for Ab production), detection of all proteins was significantly reduced compared with protein detection in the absence of the blocking peptide. That the specific peptide acts to block detection of the higher m proteins as well as RpL22e at 33 kD favors the interpretation that the Ab is detecting RpL22e proteins. To provide additional support that high m products detected with the RpL22e polyclonal Ab are RpL22e proteins, we next attempted to express FLAG-tagged RpL22e in S2 cells. While the addition of the FLAG-tag did not hinder protein stability, only minimal amounts of protein that migrated slower than the predicted m of 33 kD accumulated in some experiments (Fig. S3). Production of higher m RpL22e proteins within S2 cells may have been curtailed by (1) steric hindrance of the FLAG tag on the function of the protein modification machinery or (2) an imbalance in protein modification machinery relative to the abundance of FLAG-tagged RpL22e in overexpression experiments. We later explored the possibility that overexpression of FLAG-tagged RpL22e within S2 cells overwhelms the modification machinery and determine that higher m products are produced when S2 cells overexpress components of the Drosophila SUMOylation pathway. More definitive evidence to confirm the identity of higher m species as RpL22e proteins was provided by RNAi knockdown of RpL22e in S2 cells. By treating cells with dsRNA targeting codons 1–100 of RpL22e, immunoreactive proteins of the predicted m (33 kD) as well as all other higher m proteins are significantly reduced over time compared with dsRNA GFP controls (Fig. 1C). Taken together, we conclude that immunoreactive proteins in the 33, 43 and 55 kD range are true RpL22e proteins.

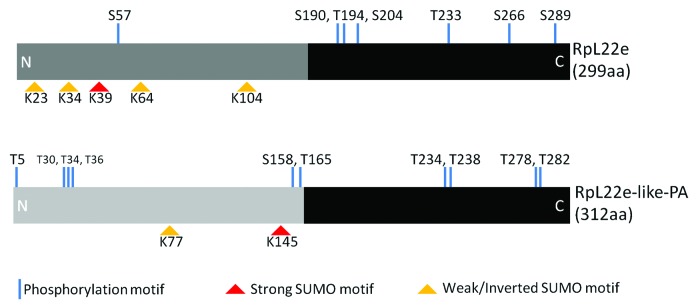

By RT-PCR, we eliminated the possibility that alternative splicing of the rpL22e gene could produce transcripts that would encode higher m proteins, as amplicons larger than those that would be predicted from the coding sequence are not evident (data not shown). We therefore hypothesize that the accumulation of higher m RpL22e proteins is a result of PTM. Initial investigation of PTMs by in silico probing (via Eukaryotic Linear Motif scanner) for conserved modification motifs predicts multiple modifications for RpL22e (Fig. 2, Table S1). Seven putative phosphorylation targets are predicted in RpL22e, however, the small m of such a modification (95Da per phosphate group), even if combined, would not account for the observed ~10 and ~20 kD increase in m (Fig. 1). However, a conserved SUMOylation motif was predicted for RpL22e and if covalent attachment of the 10 kD SUMO protein does occur, this could account for the observed electrophoretic shift seen by immunodetection.

Figure 2. Computational predictions of post-translational modifications within the RpL22e family. Eukaryotic Linear Motif (ELM) scanner predicts multiple modifications in both RpL22e (FBgn0015288; FBpp0070143) and RpL22e-like-PA (FBgn0034837; FBpp0071958) as consensus sequences were conserved for various phosphorylation and SUMOylation motifs. The black domains represent the conserved region between the fly paralogues and other eukaryotic RpL22e proteins. Dark and light gray domains represent the fly-specific histone H1-like N-terminal extension that has less homology between the paralogues. Consensus sequences and motifs within RpL22e family members are found in Table S1.

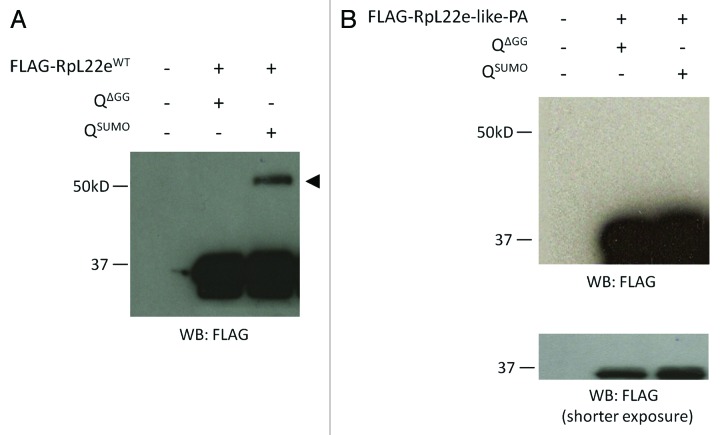

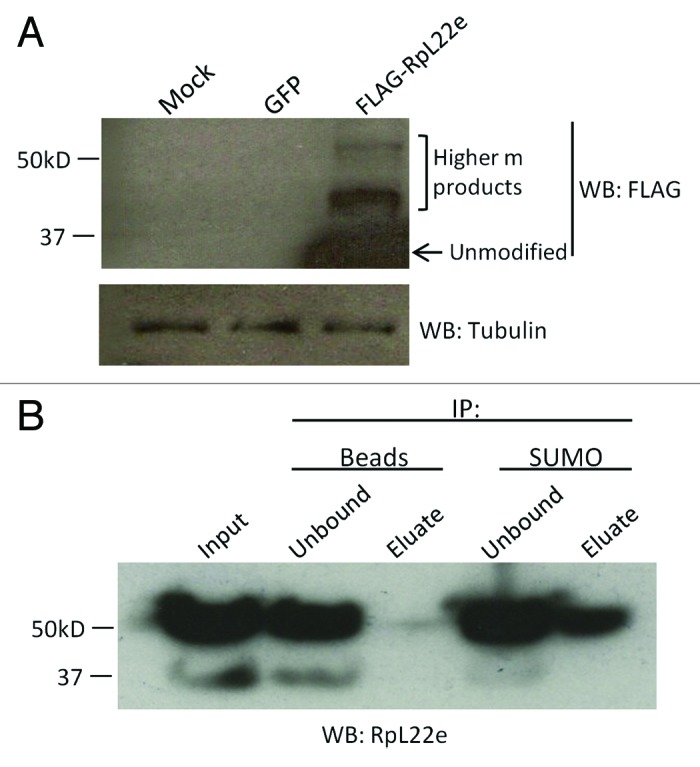

Given that initial expression of FLAG-tagged RpL22e in S2 cells did not produce an abundance of high m products, we surmised that if RpL22e is SUMOylated, then its overexpression in S2 cells would produce unequal stoichiometry between the target protein and SUMO, likely resulting in relatively little SUMO-modified FLAG-tagged RpL22e. To rectify this imbalance, it is common to overexpress elements of the SUMOylation pathway, including the E2 conjugating enzymes (Ubc9 in Drosophila) and SUMO itself.34-36 Therefore, we used the previously developed 529SU S2 stable cell line, which harbors expression vectors for FLAG-SUMO and HA-Ubc9, both under the control of the Cu2+ inducible metallothionein promoter for FLAG-tagged RpL22e expression experiments.34 Western analysis of FLAG-RpL22e transfections shows accumulation of FLAG proteins with m of 33 kD, as well as (although at lower quantities) ~43 kD and ~55 kD (Fig. 3A). High levels of endogenous RpL22e may hinder FLAG-RpL22e modification in S2 cell-based assays. Although SUMO is FLAG-tagged in the cell line and we would expect any FLAG-SUMO conjugate to be detected with anti-FLAG Ab, we note that FLAG-SUMO conjugates are present at 43–55 kD, consistent with known higher m RpL22e species. These FLAG-SUMO conjugates are only detected when RpL22e, but not GFP, is transiently expressed. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that high m species could be SUMOylated RpL22e proteins or alternatively yet less likely, RpL22e expression (but not GFP expression) may stimulate SUMO modification in this cell line for unknown proteins whose m coincides with those of higher m RpL22e species. In either case, more direct evidence for RpL22e SUMO modification would be required.

Figure 3. Anti-SUMO immunoprecipitates FLAG-tagged RpL22e of higher m. (A) FLAG-RpL22e is detected (using anti-FLAG Ab) above its predicted m of 33 kD in the 43–55 kD range in the 529SU S2 cell line, which harbors inducible expression of the SUMO protein (as FLAG-SUMO) and the E2 SUMO conjugating enzyme Ubc9 (as HA-Ubc9). Although the FLAG Ab will detect both FLAG-RpL22e and all SUMOylated proteins, we note that FLAG-SUMO conjugates are only detected when FLAG-RpL22e, but not GFP, is transiently expressed. Cells treated with calcium phosphate alone served as the mock control. The FLAG-SUMO conjugates detected are not present in the mock control. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) 55α RpL22e can be immunoprecipitated from S2 cells using anti-Drosophila SUMO, but not with beads alone. The polyclonal Ab against RpL22e was used for detection.

Drosophila RpL22e has been identified in the first purification step of a TAP-tagging proteomics study identifying SUMO targets in embryos.29 In this study, the initial purification by Ni-NTA chromatography was performed under strong denaturing conditions (8M urea), eliminating any non-covalent interactions. Identifying RpL22e from purified tagged-SUMO under these conditions does provide preliminary evidence that RpL22e can be SUMOylated in Drosophila. Based on the observed m, we predict at least two SUMO moieties are covalently attached to RpL22e, with 43α and/or 43β containing a single moiety and 55α representing attachment of two SUMO moieties. While only one conserved major motif is found by the in silico analysis, SUMO has been shown to form chains in yeast and humans (for a review see ref. 37) and evidence does suggest SUMO chain formation can occur in Drosophila as well.38

We next assessed RpL22e SUMOylation by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments. Using S2 cell lysates, SUMOylated proteins were immunoprecipitated using anti-Drosophila SUMO. The 55α RpL22e species was captured in IP reactions containing anti-Drosophila SUMO, but not in control reactions with beads alone (Fig. 3B). The amount of 43 kD species in this particular S2 sample is effectively undetectable compared with quantities in other samples (e.g., Figure 1); thus, it is unknown if the 43 kD species would be captured in co-IP experiments as effectively as the 55α species. Additionally, a SUMO immunoreactive protein of 55 kD (and not 43 kD) is captured from S2 cell lysates in IP reactions with anti-RpL22e, but not in control reactions (Fig. S4).

To further test if RpL22e is a SUMOylation substrate, we used the previously developed bacterial-based SUMOylation assay utilizing the Drosophila SUMOylation pathway enzymes and SUMO protein.29 E. coli were co-transformed with plasmids encoding FLAG-RpL22e and either an incompetent (QΔGG) or competent (QSUMO) form of SUMO. Western analysis shows a 20 kD electrophoretic shift of FLAG-RpL22e when co-transformed with a competent from of SUMO (QSUMO), but not with an incompetent form (QΔGG) (Fig. 4A). Based on the observed m, we conclude the modification is due to the addition of two SUMO moieties (55α).

Figure 4. FLAG-RpL22e, but not FLAG-RpL22e-like-PA, can be SUMOylated in vitro. (A) When co-expressed in E. coli harboring the Drosophila SUMOylation machinery (the E1 heteromeric activating enzyme and E2 conjugating enzyme) with an attachable competent SUMO protein (QSUMO), but not with an incompetent SUMO mutant (QΔGG), FLAG-RpL22e is detected above its predicted m (33 kD) at 55 kD (arrowhead). Based on the m shift, the addition of two SUMO moieties is predicted. (B) Although harboring two predicted SUMO motifs (Fig. 2, Table S1), FLAG-RpL22e-like-PA is not SUMOylated in vitro.

In an attempt to gain evidence for functional diversification between the RpL22e paralogues, we extended the in silico investigation of predicted PTMs of RpL22e-like-PA (Fig. 2, Table S1). Interestingly, although located at a separate location within the N terminus, a conserved major SUMO motif is predicted in RpL22e-like-PA. We have not detected RpL22e-like-PA above its predicted m in testis protein lysates.6 Therefore, if modified, proteins are either not stable or do not accumulate to detectable levels. Nevertheless, we tested if RpL22e-like-PA is a SUMO substrate using the bacterial-based SUMOylation assay. Consistent with in vivo testis results, SUMOylation of RpL22e-like-PA is not evident in this bacterial SUMO assay (Fig. 4B). Positioning of the predicted motif and/or its structural context may render this SUMO motif inaccessible or nonfunctional not only in the bacterial assay, but in the testis environment as well. Alternatively, additional essential factor(s) and/or conditions may be required for RpL22-like-PA SUMOylation that are neither present in the bacterial system or by inference, in the testis germline environment as well.

In many instances SUMOylation is known to impact target protein stability (for a review see ref. 32). RpS3 stability is enhanced by SUMOylation.27 In order to determine if a similar effect could be demonstrated for RpL22e, we used an in vitro proteolytic assay described by Jang et al., previously used to assess SUMOylated RpS3 stability.27 We did not observe an impact of SUMOylation on the stability of RpL22e, previously expressed and SUMOylated in a bacterial assay. The proteolytic sensitivity of unmodified and SUMOylated RpL22e was equivalent in this assay (Fig. S5). We do conclude, however, that SUMOylated RpL22e from S2 cells and testis is highly stable, as revealed by western blot analysis (Fig. 1C).

Male germline-specific modifications include specific phosphorylation of SUMOylated RpL22e

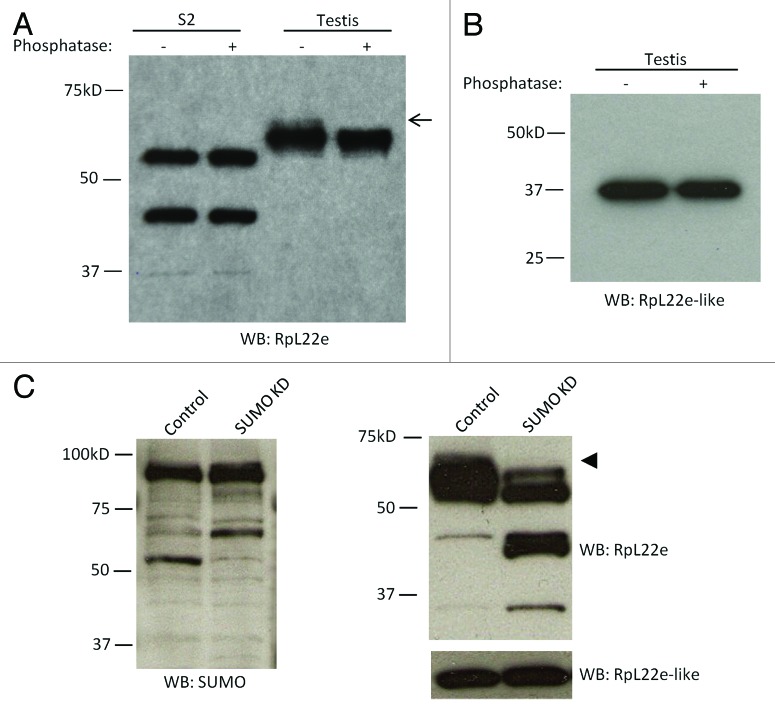

To characterize the testis-specific RpL22e modifications (Fig. 1), we proceeded to investigate possible phosphorylation and additional SUMOylation events. Using in vitro calf-intestinal alkaline phosphatase treatments, we assessed the phosphorylation state of RpL22e in S2 cells and testis. Western analysis of extracts treated with phosphatase shows a significant reduction of the testis-specific 55γ species exclusively compared with control reactions (Fig. 5A). Thus, the 55γ species is a phosphorylated form of SUMOylated RpL22e. Whether this 55γ contains a single or multiple phosphate moieties is not addressed here. Additionally, other lower m RpL22e species (e.g., 43β) may also be phosphorylated but not accessible to the phosphatase in vitro.

Figure 5. Testis RpL22e, but not FLAG-RpL22e-like-PA, is susceptible to phosphatase in vitro and smt3 (SUMO) knockdown in vivo. (A) Incubation of S2 cell and testis tissue extracts with calf-intestinal alkaline phosphatase in vitro significantly reduces immunodetection of the testis-specific 55γ RpL22e species (arrow). (B) Phosphatase treatment has no effect on the RpL22e-like-PA immunodetection pattern in testis. (C) In vivo knockdown of smt3 (via UAS-GAL4 binary system) was achieved by expressing a miR1 cassette targeting smt3 using a germline-specific GAL4 driver (bam-GAL4-VP16, UAS-Dicer2). Altered SUMOylated protein levels in the testis, determined by Western analysis, confirm smt3 knockdown. The testis RpL22e immunodetection pattern is significantly altered upon smt3 knockdown compared with control tissue. No change in RpL22e-like-PA accumulating levels is seen. In an attempt to produce a stronger smt3 knockdown, we used the early germline-specific GAL4 driver, nos-GAL4; however, smt3 depletion in this case results in complete loss of the germline (data not shown).

Multiple phosphorylation targets are predicted in both RpL22e and RpL22e-like-PA (Fig. 2, Table S1). No evidence for significant modification of germline-expressed RpL22e-like-PA has been observed (this work included).6 Phosphatase treatments of testis extracts did not result in any discernible electrophoretic shifts in Western analysis of RpL22e-like-PA (Fig. 5B), supporting the conclusion that RpL22e-like-PA is not phosphorylated at accumulating levels in the testis.

Further evidence of RpL22e SUMOylation in testis and the male germline is provided by SUMO knockdown. Using the UAS-GAL4 binary system and the pVALIUM20 RNAi vector to express a miR1 cassette for knockdown, smt3 (encodes the single Drosophila SUMO protein) was specifically targeted in the male germline using the bam-GAL4-VP16 driver.39,40 Confirmation of a smt3 knockdown effect is shown by an altered pattern of SUMOylated proteins detected by anti-Drosophila SUMO in the smt3 knockdown compared with controls (Fig. 5C). Western analysis of testis tissue from F1 males when compared with control tissue shows that both 43 kD species increase in amount after SUMO knockdown, consistent with the hypothesis that these species represent an intermediate with one SUMO group. Additionally, a strong reduction in the amount of testis-specific 55β and 55γ RpL22e protein species is displayed (Fig. 5C). Depletion of the 55β species in response to SUMO knockdown suggests that this species is also a SUMOylated protein that may arise from an additional SUMO residue added to SUMOylated 55α RpL22e, although specific data to address this possibility are currently unavailable. We note, however, that the “~55 kD” designation in our nomenclature provides only an approximate m for these slower migrating proteins, as 55β and 55γ are progressively increasing in m compared with 55 kD (and 55α) and may fall within the ~63−65 kD range to account for an additional SUMO moiety added. Depletion of phosphorylated 55γ would be expected if derived from phosphorylation of the 55β species. Collectively, quantitative changes in modified RpL22e proteins in the 43 kD range (43α and 43β), as well as for RpL22e proteins in the 55 kD range, further support the conclusion RpL22e is a SUMO substrate.

In vivo knockdown of SUMO also provides evidence that the phosphorylated 55γ species is found in germ cells, as the bam-GAL4-VP16 driver has a restricted expression pattern confined to the germline. Although the presence of the 55γ species within somatic cyst cells cannot be excluded, it is apparent that the majority of the 55γ species in the testis is contributed by germ cells. Taking these data together, we propose that testis-specific modifications result from phosphorylation of SUMOylated 55β RpL22e, giving rise to the 55γ species.

Unmodified RpL22e associates with the translation machinery in S2 cells

Phosphorylation and methylation are among the most common PTMs seen in eukaryotic Rps.17,41 Such modifications typically have roles in ribosome biogenesis, as opposed to active translation.42-44 In some cases, modification (e.g., ubiquitylation) of the Rp occurs on polysomes, suggesting a role for the modification in active translation.45 Accumulation of unmodified or modified Rp within a particular type of ribosomal particle provides insight into a putative role in assembly or active translation. Conversely, the lack of accumulation in ribosomal particles would provide evidence for an extra-ribosomal function.

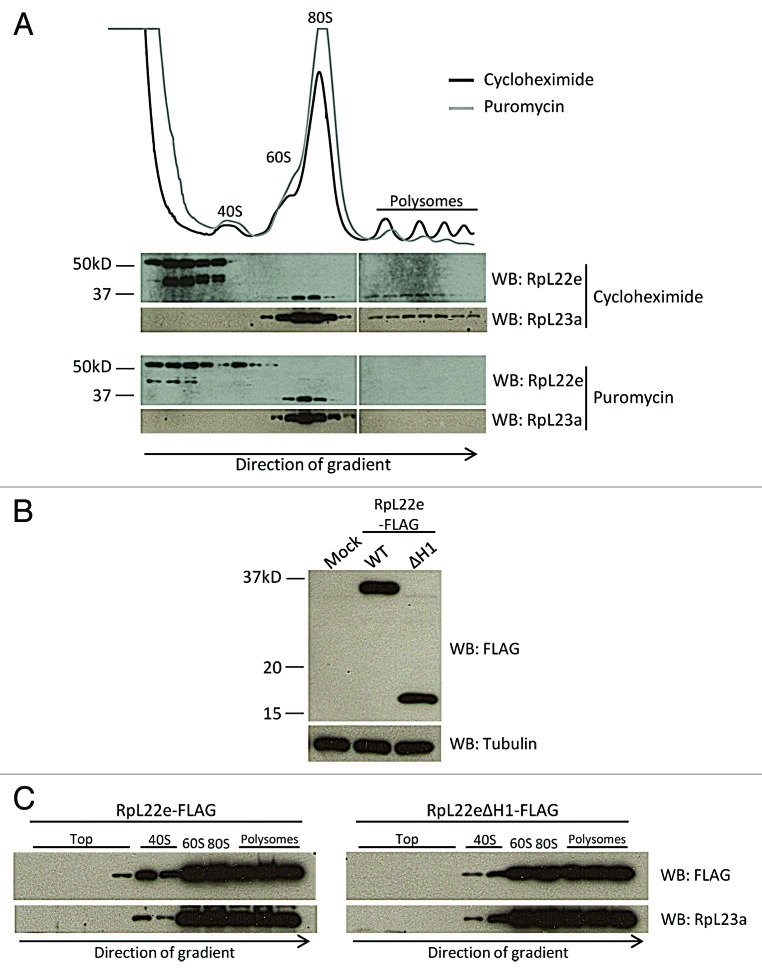

To assess a role for RpL22e in translation, we performed polysome analysis in S2 cells, using distribution of a large ribosomal subunit protein (RpL23a) for comparison. In cycloheximide-treated cells, unmodified RpL22e (seen at 33 kD) co-sediments with the 60S large subunit, 80S monosomes, as well as polysomes, supporting its role as a ribosomal component and as a component of actively translating ribosomes (Fig. 6A). A similar distribution pattern is seen for RpL23a. Notably, all modified RpL22e, representing the majority of this protein in S2 cells (43α, 43β and 55α), accumulates at the top of the gradient, well segregated from ribosomal subunits and active translation machinery, strongly indicative of a role apart from translation. Unlike modified RpL22e, no RpL23a accumulated at the top of the gradient.

Figure 6. Modified RpL22e does not co-sediment with the translation machinery. (A) S2 cell extracts were separated in a 10–50% buffered sucrose gradient for polysome analysis to assess RpL22e co-sedimentation with ribosomal subunits, 80S monosomes and polysomes. In cells treated with the elongation inhibitor cycloheximide (black line), all modified RpL22e (43α, β and 55α) accumulates at the top of the gradient and only the unmodified 33 kD RpL22e co-sediments with the 60S large subunit, 80S monosomes and polysomes. Treatment with the chain terminator puromycin (causing a disruption of polysomes and accumulation of 80S monosomes; gray line) shifts the immunodetection pattern of unmodified RpL22e from polysomes to monosomes. Endogenous RpL23a was used was a positive control. (B) Deletion of fly-specific histone H1-like domain that harbors five putative SUMOylation motifs (ΔH1; residues 176−299) results in stable FLAG-tagged RpL22e protein (C-terminally tagged) in S2 cells. Full length (residues 1–299) is represented as WT. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Polysome analysis of S2 cells expressing RpL22e-FLAG (full length) or RpL22eΔH1-FLAG shows an equal distribution pattern, as both were found to co-sediment with the translation machinery. The presence of FLAG-RpL22 in less dense “top” fractions may be attributable to high overexpression levels. Endogenous RpL23a was used as a positive control.

Further, to confirm that unmodified RpL22e (33 kD) is associated with the translation machinery, cells were treated with the chain terminator puromycin, resulting in dissociation of polysomes and accumulation of 80S monosomes. Similar to what is seen for RpL23a, sedimentation of unmodified RpL22e protein shifts from polysomes to the 80S monosome region with puromycin treatment (Fig. 6A). Taken together, we conclude that only unmodified RpL22e associates with ribosomal subunits and is part of the active translation machinery. We find that modified RpL22e (43α, 43β and 55α) in S2 cells does not co-sediment at detectable levels with ribosomal particles and remains distributed at the top of ribosome gradient profiles.

To determine if SUMOylation of RpL22e has a role in ribosome assembly, we investigated a mutant that lacks all predicted SUMO motifs, consisting primarily of the C-terminal domain that harbors the rRNA-binding signature. In the in vitro bacterial assay, SUMOylation of a K39R mutant was not completely abolished (data not shown), suggesting that a lysine(s) other than the predicted major acceptor lysine was critical for SUMO modification. Therefore, we deleted the fly-specific N-terminal histone H1-like domain (defined by Koyama et al.) that harbors all predicted SUMO motifs (Fig. 2).14 Deleting the N-terminal domain (residues 1–175) results in a sequence that is highly conserved between all metazoans and closely resembles orthologs from yeast, C. elegans and human. Noteworthy is the fact that no SUMO modification motifs are predicted by ELM (data not shown) in these RpL22e orthologs. The resulting coding sequence, RpL22eΔH1-FLAG (residues 176–299), can be expressed in S2 cells at similar levels as the full length protein, suggesting that deletion of the domain does not hinder stability (Fig. 6B). Polysome analysis of full length (RpL22e-FLAG) and truncated RpL22e (RpL22eΔH1-FLAG) shows that both have a similar distribution pattern as endogenous RpL23a and both co-sediment with the active translation machinery (Fig. 6C). The significance of a slightly different distribution of truncated RpL22eΔH1-FLAG in 40S subunits compared with RpL22e in 40S subunits is unknown, but may only reflect slight gradient variations since the distribution pattern for RpL23a is similar in each case. As seen in Figure 3, the FLAG tag decreases the amount of modified RpL22e and the unmodified form of RpL22e is expected to migrate with the polysomes and not be free at the top of the gradient. Therefore, we postulate that stable modification of RpL22e, most notably SUMOylation, is not required for RpL22e assembly into the 60S ribosomal subunit or for ribosome function. Instead, SUMOylation of RpL22e likely shunts the protein into an extra-ribosomal pathway.

We have previously shown that RpL22e-like-PA co-sediments with ribosomes and polysomes in sucrose gradients.6 Though no evidence for PTM of RpL22e-like-PA in testis is apparent in immunoblots (ref. 6 and this study), we explored the possibility that the histone H1-like domain is a necessary element for RpL22e-like-PA incorporation into ribosomes in S2 cells. Gradient analysis shows that the majority of truncated RpL22e-like-PA (ΔH1) co-sediments with ribosomes and polysomes, suggesting that the histone H1-like domain is dispensable for RpL22e-like-PA assembly into ribosomes and for association with the active translation machinery (Fig. S6). However, deletion of the histone H1-like in RpL22e-like (ΔH1) does result in an excess of free/unincorporated protein, distributed across the top of the gradient unlike the distribution for full-length RpL22e-like-PA, suggesting a possible role of the domain in efficient ribosome incorporation (Fig. S6).

RpL22e paralogues are differently localized in the male germline

In yeast, localization of 54 out of the 59 pairs of duplicated ribosomal proteins, typically encoding identical or nearly identical proteins, has been studied using a GFP fusion approach.46 Of the 54 pairs investigated, only five pairs (RpL22e is not included) had paralogues with unique, separate localization patterns, suggesting possible non-redundant roles.46 We have previously reported that within the male reproductive system, RpL22e-like-PA is specifically localized to the male germline and RpL22e is ubiquitously localized throughout the male reproductive tract.6 Insights into redundant or novel functions of both paralogues may be provided by comparing subcellular localization. Using paralogue-specific Abs and confocal microscopy, we assessed the distribution pattern of the RpL22e family in the male germline.

Drosophila male germline development is a coordinated event requiring somatic and germline stem cell signaling cascades that steer germ cells toward sperm cell differentiation, as well as testis-specific gene expression and dramatic changes in nuclear and cytoplasmic morphology in germ cells (for a review see ref. 47).48,49 Briefly, germ cells originate at the apical tip of the testis from asymmetric mitotic divisions of germline stem cells (GSCs) to produce a spermatogonial cell and a GSC. Surrounded by two somatic cyst cells, each spermatogonial cell undergoes four rounds of mitosis with incomplete cytokinesis to generate a 16-cell cyst containing post-mitotic, primary spermatocytes primed to enter meiosis. After a prolonged G2 phase of extensive cell volume growth (~30×) and gene expression, early primary spermatocytes enter meiosis, resulting ultimately in 64 round spermatids per cyst. Spermatid elongation ensues during spermiogenesis and the individualization process is completed to form mature, separated spermatids. The gradient of germ cell maturation (with the most immature cysts at the apical tip and mature spermatids positioned distally to move into the seminal vesicle) allows for easy staging of germline development. Notably, nuclei are very distinct in phase contrast microscopy (and when immunostaining cytosolic proteins) can be counted to identify the cyst stage. Additionally, maturing meiotic spermatocytes are distinguishable as their nuclei enlarge during the prolonged G2 phase before meiosis I.

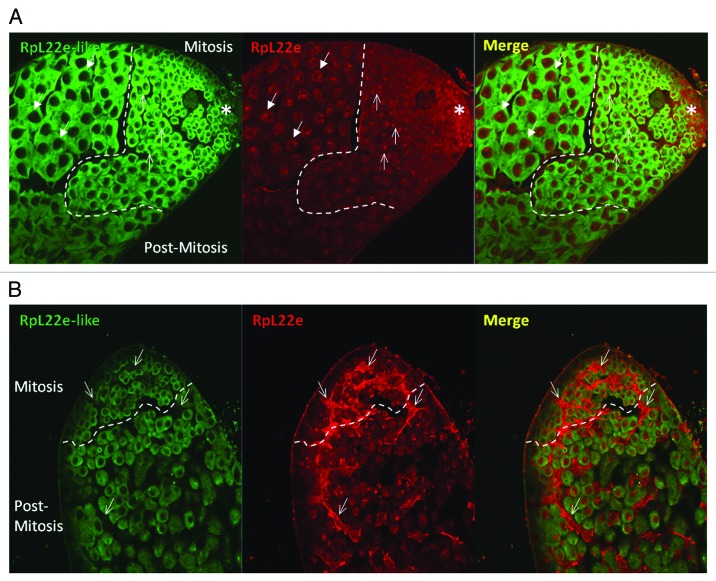

IHC reveals distinct and separate subcellular localization patterns for RpL22e paralogues in the mitotic and meiotic male germ line. Indicative of a ribosomal protein, nucleolar and strong cytoplasmic localization is evident for RpL22e-like-PA in mitotic spermatogonia (Fig. 7A). In early primary spermatocytes (before first meiotic division), nucleolar accumulation of RpL22e-like-PA is still evident although less pronounced; abundant cytoplasmic staining is still apparent. Nucleolar accumulation of RpL22e-like-PA in mature primary spermatocytes is absent, as only strong cytoplasmic staining is seen (Fig. 7A). Notably, immunostaining is not seen in the somatic cells within the testis. Furthermore, these data provide evidence that RpL22e-like-PA is a male germ cell marker in Drosophila.

Figure 7. RpL22e family members are differently localized in the male germline. (A) The mitotic and post-mitotic germline are separated by a dashed line. Mitotic spermatogonia are proximal to the apical tip (asterisk), where germline stem cells are located and germline development begins. Post-mitotic primary spermatocytes (will further develop and enter meiosis I) are found distal to the apical tip. Immunofluorescence (used to localize RpL22e family members) reveals distinct localization patterns in the male germline. RpL22e-like-PA (green) is primarily cytoplasmic, with some subnuclear accumulation (presumably in the nucleolus) in mitotic germ cells. Strong cytoplasmic localization is seen meiotic spermatocytes. RpL22e (red) is primarily distributed in the nucleus. A punctate RpL22e localization is seen in the mitotic germline (thin arrow), but becomes more nucleoplasmic in post-mitotic cells (arrow with filled-in arrowhead). Co-localization of RpL22e-like-PA with RpL22e is only seen in the nucleus (presumably in the nucleolus) in mitotic spermatogonia (thin arrows, merge). (B) RpL22e (red) is also detected in somatic cyst cells (arrow) that surround spermatogonial cysts. RpL22e-like-PA (green) is a distinct germline marker. Although the anti-RpL22e-like Ab detects both spliced isoforms (-PA and -PB), staining intensity is consistent with the relative accumulation of RpL22e-like-PA (based on immunoblot analysis) compared with RpL22e-like-PB in the testis.6 RpL22e-like-PA is far more abundant (~10,000 × ) than RpL22e-like-PB in the testis.6

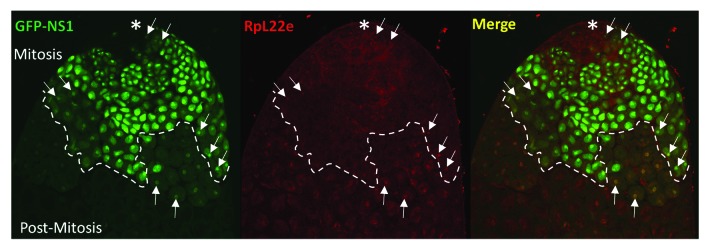

Interestingly, RpL22e has a predominant nuclear localization pattern in both mitotic and meiotic germ cells, with some cytoplasmic staining most evident in mitotic germ cells. Strong cytoplasmic staining is also apparent in somatic cyst cells (Fig. 7A and B). There is, however, a clear difference in the nuclear distribution of RpL22e within mitotic cells compared with meiotic germ cells. Nucleolar localization is seen in mitotic spermatogonia, partially co-localizing with RpL22e-like, with partial immunostaining in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7A). Nucleolar localization was confirmed by co-localizing RpL22e with the nucleolar protein nucleostemin1 (Fig. 8), shown to be enriched in the granular component of the nucleolus in Drosophila.50 GFP-tagged nucleostemin1 was expressed specially in the early male germline (limited to mitotic spermatogonia and early post-mitotic primary spermatocytes) using the GAL4-UAS binary system with the germline specific bam-GAL4-VP16 driver. Although immunostaining shows that RpL22e co-localizes with the nucleolus primarily in mitotic cells (Fig. 7A and B, Fig. 8), limits in the amount of the co-localization signal with GFP-NS1 can be accounted for by the expression pattern for NS1, driven by a germline driver that is most active in early stage mitotic spermatogonia and early primary spermatocytes.

Figure 8. RpL22e co-localizes with nucleolar markers in mitotic spermatogonia and early (post-mitotic) primary spermatocytes. GFP-tagged Nucleostemin1 (GFP-NS1) was expressed in vivo in the early germline using the germline-specific bam-GAL4-VP16 driver. Co-localization of GFP-NS1 (green) nucleolar foci with RpL22e (red) subnuclear immunostaining is evident in mitotic spermatogonia and early primary spermatocytes (arrows). Mitotic spermatogonia are proximal to the apical tip (asterisk), where germline stem cells are located and germline development is initiated. Post-mitotic primary spermatocytes are found distal to the apical tip.

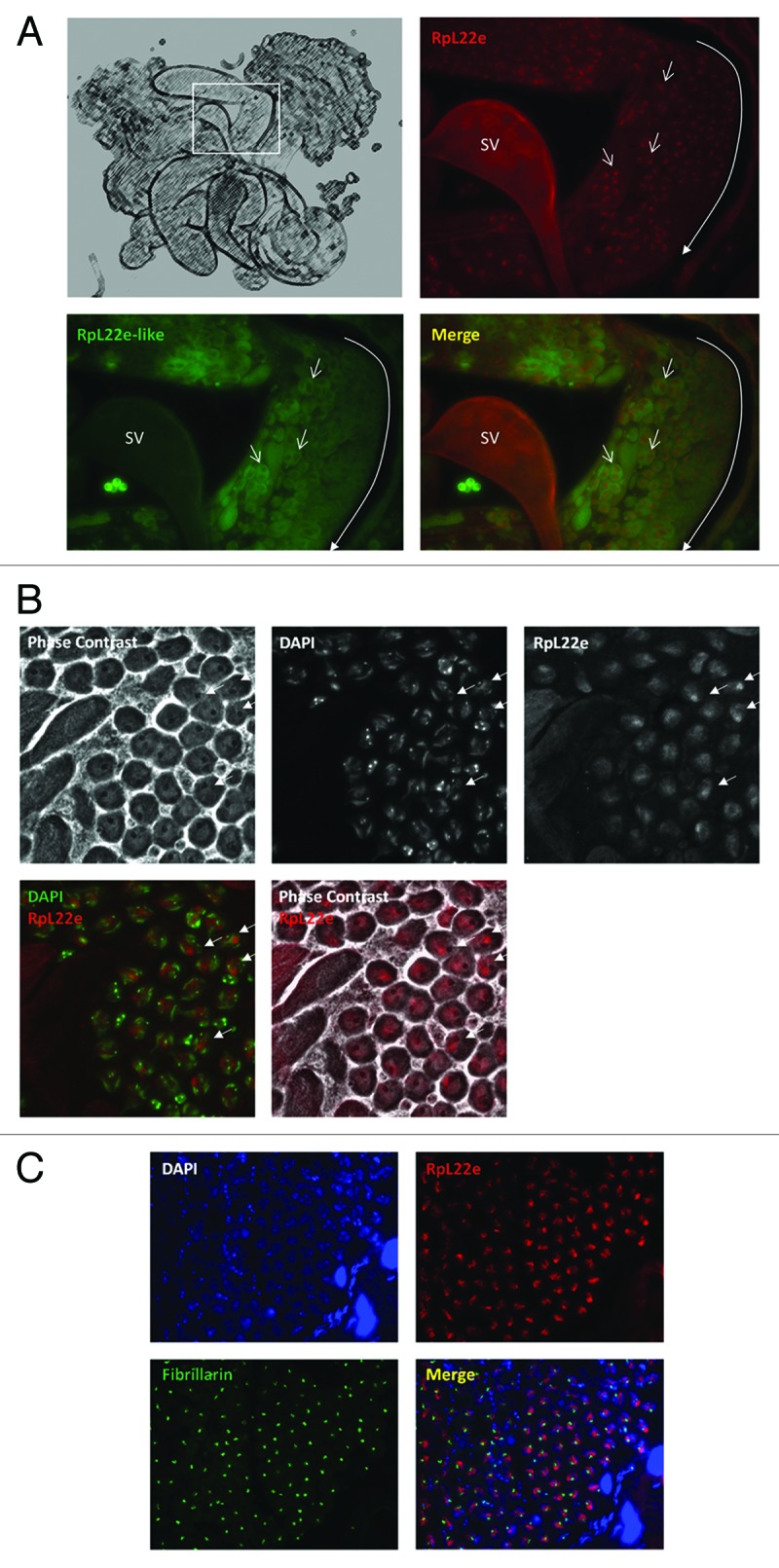

The punctate nucleolar RpL22e pattern seen in the mitotic germ line dissipates and becomes increasingly nucleoplasmic in maturing post-mitotic spermatocytes (Fig. 7A and B, Fig. 9A). Using phase contrast microscopy of tissue immunolabeled for RpL22e, we observed distinct segregation (although still close proximity) of RpL22e from the nucleolus within post-mitotic primary spermatocytes (Fig. 9B). We further confirmed the RpL22e nucleoplasmic pattern by co-staining for fibrillarin, a marker for the dense fibrillar center of the nucleolus. Confocal microcopy confirms the close proximity, but separate localization of RpL22e and fibrillarin, as co-localization is not evident (Fig. 9C, Fig. S8). In more mature meiotic spermatocytes, the RpL22e staining pattern is less uniformly diffuse in the nucleoplasm and includes focused, punctate staining in the nuclear periphery, creating a cage-like lattice pattern in the nucleoplasm, visualized by confocal microscopy (Fig. S8). As spermiogenesis continues, sperm cell nuclei become increasingly compact. It is unclear how the RpL22e staining pattern is modified in this maturing population of cells (as images of this population were difficult to capture), but it is notable that the axonemes of individual sperm cells show strong RpL22e and/or RpL22e-like-PA staining.6 For RpL22e, it is unclear if axoneme staining results from extrusion of RpL22e from the nucleoplasm into the cytoplasm as the sperm nucleus undergoes compaction or if new RpL22e protein synthesis in the cytoplasm provides the explanation.

Figure 9. RpL22e does not co-localize with the nucleolus in mature meiotic spermatocytes. (A) Schematic representation of male reproductive tract as shown in Kearse et al. (2011).6 Inset shows region of testis distal from the apical tip where populations of meiotic spermatocytes are represented. Immunohistochemistry of the RpL22e paralogues shows distinct punctate nuclear localization of RpL22e (red) in maturing primary spermatocytes, whereas RpL22e-like (green) remains primarily cytoplasmic (open arrows). The developmental gradient of germline maturation (from less mature to more mature) is represented by the long closed arrow. SV: seminal vesicle. (B) Phase contrast and immunohistochemistry of mature meiotic primary spermatoctyes shows juxtaposition, but not co-localization, of the phase dark nucleoli and RpL22e (red; arrows). DAPI staining (green) was used to confirm nuclear co-localization. (C) Co-staining of the nucleolar marker fibrillarin (green) and RpL22e (red) in mature meiotic primary spermatocytes confirms RpL22e is nucleoplasmic, not nucleolar (arrows). DAPI staining (blue) was used to confirm nuclear co-localization.

Co-localization of RpL22e and GFP-nucleostemin1, a protein localized to the granular component of the nucleolus as reported by Rosby et al., and a high level of cytoplasmic staining may collectively support a ribosomal role for RpL22e during mitotic stages of spermatogenesis.50 The presence of RpL22e within nucleoli may, however, suggest other non-ribosomal roles as well. The function of nucleoplasmic RpL22e in meiotic spermatocytes remains unknown, but nucleoplasmic immunolocalization favors the hypothesis that in the meiotic germline, the bulk of RpL22e does not have a role in ribosome biogenesis or in active translation. The predominant nucleoplasmic immunostaining pattern for RpL22e in the absence of strong cytoplasmic staining in meiotic germ cells correlates well with results from S2 cells showing that modified RpL22e does not co-sediment with polysomes, but instead sediments at the top of ribosomal profile gradients (Fig. 6). These data favor the proposal for an extra-ribosomal role for modified RpL22e in the testis as well. Immunohistochemistry of S2 cells shows strong cytoplasmic staining as well as some subnuclear staining for RpL22e (Fig. S7). The subcellular distribution of modified and unmodified RpL22e within S2 cells is unknown, but based on ribosome profiles from S2 cells, it is reasonable to attribute at least some cytoplasmic staining to the small pool of actively translating ribosomes containing unmodified RpL22e (as shown in Fig. 6).

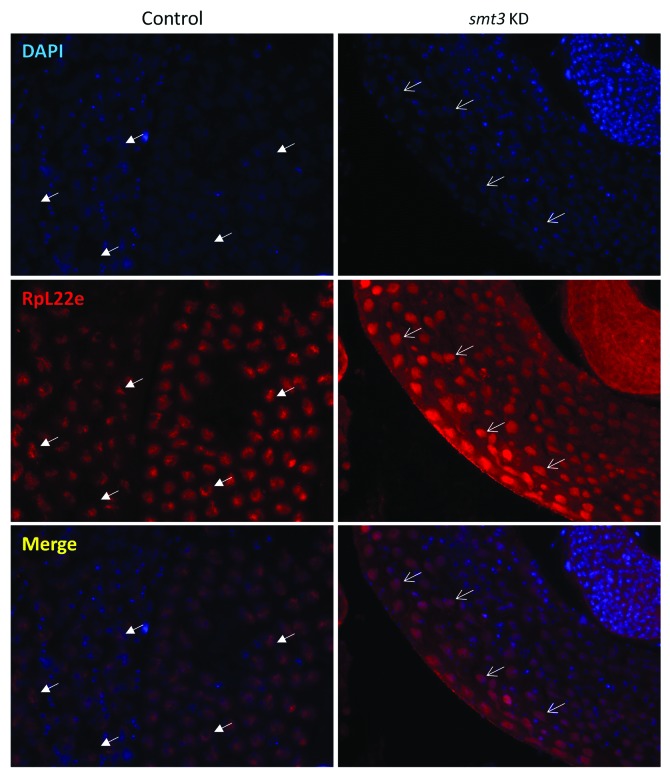

SUMO knockdown perturbs RpL22e localization in the meiotic germline

We next determined the impact of SUMO knockdown on RpL22e localization. As previously seen in Figure 5C, knockdown of SUMO causes a drastic change in RpL22e modification. Immunostaining shows that RpL22e becomes more widely nucleoplasmic, as compared with the control (Fig. 10). The characteristic focused, cage-like staining near the nuclear periphery is not observed, but staining remains more diffuse within the nucleoplasm. Whether or not this change in nucleoplasmic localization is a direct effect of the altered RpL22e modification pattern or of subsequent nuclear defects from SUMO knockdown is unclear. Could the change in localization pattern (Fig. 10) reflect the loss of the 55γ (phosphorylated) molecular species as seen in Figure 5C? Nevertheless, RpL22e nucleoplasmic localization is sensitive to SUMO protein levels.

Figure 10. RpL22e localization in mature spermatocytes is sensitive to SUMO levels. In vivo knockdown of SUMO (smt3) was achieved by expressing a miR1 RNA cassette targeting smt3 (Fig. 5C). Nucleoplasmic RpL22e immunolocalization (red) in mature meiotic spermatocytes is generally widespread (thin arrows) as a result of the smt3 knockdown, as compared with control tissue (wildtype) where the RpL22e nucleoplasmic pattern is more punctate (arrows with filled-in arrowheads). DAPI staining is seen in blue.

Discussion

RpL22e is differentially post-translationally modified in different tissues

Evidence from S2 cell-based expression assays and in vivo expression analyses in several tissues shows that RpL22e is expressed not only at its predicted m of 33 kD, but also at a higher m of ~43−55 kD. Collectively, co-IPs and bacterial SUMOylation assays favor the conclusion that higher m RpL22e is attributable to PTMs that include SUMOylation, with the amount of SUMO-conjugated RpL22e accumulating in varying amounts in different tissues. These results extend the proteomics report of Nie et al. and show that RpL22e is a direct SUMO target.29

How RpL22e function changes in response to SUMOylation is unknown, but in S2 cells, SUMOylated RpL22e is not found in association with ribosomal subunits or translating ribosomes nor is SUMOylation required for RpL22e incorporation into ribosomes or for ribosome function, the latter based on our analysis in S2 cells of the expression and gradient sedimentation of an N-terminal RpL22e truncation in which all predicted SUMO motifs were deleted (RpL22eΔH1-FLAG). Thus, we conclude that RpL22e has no less than a dual cellular role including an extra-ribosomal function(s), regulated by SUMOylation.

Testis expression of RpL22e paralogues is further distinguished by a unique pattern of PTMs for RpL22e but not for RpL22e-like-PA. Additional testis-specific RpL22e modifications include phosphorylation and may include conjugation of an additional SUMO moiety. Phosphorylation of the 55β species of SUMOylated RpL22e appears to give rise to the 55γ moiety. Based on its absence from testis apical tip extracts and from day 1 smt3 (SUMO)-depleted testis extracts (that primarily accumulate primary spermatocytes), the 55γ species may be a unique component generated only in post-mitotic cells. More definitive evidence of phosphorylation timing requires more extensive biochemical investigation of cohorts of cells at different spermatogenesis stages.

Differential sub-compartmentalization of RpL22e paralogues and its functional implications

Our IHC data show that both paralogues are co-expressed within germ cells, but paralogue localization changes as germ cells mature. We have previously determined that RpL22e-like-PA is a bona fide testis Rp.6 Within mitotic germ cells closest to the apical tip, both paralogues are distributed within the nucleolus and cytoplasm. This localization pattern is consistent with a ribosomal function for both paralogues within mitotic germ cells. If so, then two different ribosomal populations based on RpL22e paralogue content could be identified, and may constitute a class of “specialized ribosomes” (as recently proposed by Xue and Barna) with unique translational roles at mitotic stages of spermatogenesis.4 In addition, the nucleolar to nucleoplasmic transition for RpL22e in the germline may reflect a non-ribosomal function(s) for this paralogue from early through late stages of germ cell maturation.

In post-mitotic primary spermatocytes, the cytoplasmic localization pattern for RpL22e-like-PA is retained; however, the RpL22e pattern is primarily nuclear; relatively little cytoplasmic staining is noted at this stage, but may still signal that a fraction of the RpL22e pool is incorporated into cytoplasmic ribosomes. RpL22e nuclear staining appears uniformly diffuse at this stage except that staining is generally excluded from nucleoli. Primary spermatocytes undergo tremendous cellular growth and increases in protein synthesis as they enter meiosis. It is unclear what novel interactions for newly synthesized RpL22e or previously synthesized RpL22e account for the observed change in nuclear distribution in maturing primary spermatocytes.

SUMOylation has been linked to regulating localization of nuclear proteins and formation of nuclear bodies. The small GTPase-activating protein RanGAP was the first SUMO substrate identified and its localization is regulated by SUMOylation.51 Unmodified RanGAP is cytoplasmic, but SUMOylated RanGAP localizes to nuclear pores.51,52 The formation of PML nuclear bodies is dependent on SUMOylation of the PML protein.53 We show that the nucleoplasmic localization of RpL22e in the meiotic germline is sensitive to SUMO levels. Whether this redistribution is a direct effect from interfering with RpL22e SUMOylation or the result of a change in nuclear architecture due to SUMO knockdown remains to be investigated.

Many studies have found mechanisms that rapidly degrade excess Rps (for review see refs. 54, 55). Therefore, it is likely that RpL22e accumulates within meiotic cell nuclei for a specific, functional role. Ni et al. reported a chromatin-RpL22e association in a transcriptional repressor complex with histone H1 in Drosophila Kc cells, suggesting that RpL22e has an alternate function in transcriptional regulation aside from its function as an Rp.56 We note that no higher m RpL22e species were identified in immunoblots in the Ni et al. report and thus it is unclear if SUMOylated RpL22e is a contributing effector in these studies. The lack of detection of modified RpL22e proteins in immunoblots in the Ni et al. report may be attributable to differences in polyclonal Ab specificities used in the two studies. Recent studies in Schizosaccharomyces pombe reported that other Rp-chromatin complexes are enriched at tRNA genes and centromeres, implicating Rps as effectors in tRNA biogenesis and centromere functions.57

Mounting evidence therefore positions numerous Rps in nuclear locations that suggest alternate Rp roles. We speculate that in a variety of cell types, SUMOylated RpL22e may associate with chromatin as cells undergo nuclear architectural changes, chromatin remodeling and/or transcriptional silencing. In the male germline additional PTMs would further regulate and expand the role of RpL22e beyond functions found in other cells and tissues. Within post-meiotic cells undergoing extensive nuclear remodeling, SUMO accumulates in chromatin during histone removal, but its role and targets are unknown.58 Whether or not testis-specific modification of SUMOylated RpL22e is part of the mechanism to promote chromatin condensation and/or transcriptional repression in maturing germ cells awaits determination.

Overall, this study finds additional evidence to support the proposal that RpL22e paralogues have evolved disparate functions within the male germline. That these paralogues are partitioned into different biochemical pathways leading to differential PTM and different subcellular accumulation within germ cells makes a compelling argument for the pursuit of RpL22e function within the male germline.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

Unless noted, all flies used were wildtype Oregon R from Carolina. The bam-GAL4-VP16 driver was a kind gift from Marina Wolfner (Cornell), but originally developed by Dennis McKearin.39 The GFP-Nucleostemin1 stock was a kind gift from Pat DiMario.50 The smt3 (SUMO) RNAi line, originally developed by the TRiP, uses the pVALIUM20 vector to generate a hairpin and was obtained from Bloomington Stock Center (#36125). We thank the TRiP at Harvard Medical School (NIH/NIGMS R01-GM084947) for providing transgenic RNAi fly stocks and/or plasmid vectors used in this study. All stocks were kept at room temperature on standard cornmeal media.

Fly in vivo RNAi and ectopic expression

SUMO (smt3) knockdown was performed using the UAS-GAL4 binary system. UAS-VALIUM20-smt3 females were crossed with bam-GAL4-VP16, UAS-Dicer2 males at 25°C to drive SUMO (smt3) knockdown in the male germline. One day old F1 males were collected and used for analyses.

Similarly, GFP-Nucleostemin1 (NS1) was expressed in the male germline by crossing UAS-GFP-NS1 females with bam-GAL4-VP16 males at 25°C. One day old F1 males were collected and used for immunohistochemical analysis.

Antibodies

The rabbit polyclonal anti-Drosophila RpL22e and mouse polyclonal anti-Drosophila RpL22e-like antibodies were previously developed by Kearse et al. and were used at 1:2000 for Western analysis and 1:100–200 for immunohistochemistry (IHC).6 The rabbit polyclonal anti-Drosophila SUMO was obtained from Abgent (#AP1287b) and used at 1:500 for Western analysis. The mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody was obtained from SIGMA (#F3165) and used at 1:1000 for Western analysis. The mouse anti-GFP monoclonal antibody was obtained from Abgent (#AM1009a) and used at 1:500 for IHC. Mouse anti-fibrillarin was obtained from Abcam (#ab4566) and used at 1:200 for IHC. The mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (E7) developed by M. Klymkowsky was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242 and used at 1:500 for Western analysis.

HRP conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies were obtained from Promega (W4021 and W4011, respectively) and used at 1:50,000 for Western analysis. Goat anti-mouse/Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-rabbit/Alexa 568 were obtained from Invitrogen (#A11029 and #A11036, respectively) and used at 1:200 for IHC.

Cell culture

S2 cells were obtained from the Drosophila Genetics Research Center and grown in Schneider’s Media (Invitrogen, #21720024) supplemented with 10% head-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, #10082) and grown at 26°C. The 529SU stable cell line was a kind gift from Albert Courey (UCLA) and was grown as above with the addition of 300µg/mL Hygromycin B as a selection agent.

Cells were seeded at 1.0 × 106 cells/mL (3mL per well) for transfections. 24h post seeding, transient transfections were performed using the calcium phosphate kit (Invitrogen, #K278001) with 19µg DNA per well following manufacture guidelines. Cells were washed 24h post transfection and induced with 500µM CuSO4 (final).

Preparation of cell and tissue lysates

S2 cells were collected during log phase growth (2−3 d post seeding at 1.0 × 106 cells/mL) or at designated time points after treatments, pelleted at 4°C and then lysed in RIPA buffer (25 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with 1mM PMSF for 10 min on ice. Gonads were dissected from wildtype adults in 1 × PBS and immediately frozen on dry ice. Approximately 15 pairs were lysed in 30 µL of RIPA buffer supplemented with 1mM PMSF for 10 min on ice. Lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000xg to clear cell debris, nuclei and mitochondria. The resulting supernatant was then quantified using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay Kit with BSA standards (500-0112).

Western analysis

SDS-PAGE was conducted under reducing (βME) conditions. Proteins were then electrotransferred onto a 0.2 µm Westran-S PVDF membrane (Whatman, #10413096) for 1h in chilled transfer buffer. Upon blocking in 5% non-fat dry milk (NFDM) for 1 h, primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C in 3% NFDM. HRP conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated for 2 h at 4°C in 3% NFDM. ECL-Plus (GE Healthcare) was used for chemiluminescent detection on Kodak Bio-Max film as directed by the manufacturer.

Peptide inhibition experiments were completed by pre-incubating Ab with 5-fold excess (by weight) of peptide used for antibody production in 500µl 1 × PBS at room temperature for 2 h before using for Western analysis. Addition of PBS in lieu of blocking peptide was used for negative control samples.

S2 cell RNAi

Knockdown of RpL22e by RNAi was achieved by serum-starvation induced uptake of dsRNA (final 37 nM) as described.59 dsRNA was generated using PCR amplicons with T7 recognition sites at 5′ and 3′ ends with the MEGAscript T7 in vitro transcription kit (Invitrogen/Ambion, #AM1333) and purified as described by manufacturer’s recommendations. Annealing of dsRNA was achieved by incubation 30–60 min at 65°C and allowed to cool slowly at room temperature. Samples were taken at designated time points, pelleted and frozen for subsequent analysis. Samples were lysed and quantitated as described above.

Cloning and mutagenesis

Previously cloned cDNAs were used as templates for PCR.6 A FLAG tag was added to the N-terminus by PCR for RpL22e and RpL22e-like-PA and cloned into pMT/V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen, # K412501) for expression studies in S2 cells and pEXP5-CT/TOPO (Invitrogen, #V96006) for expression in E. coli. The RpL22eK39R mutation was generated using the Change-IT Multiple Mutation Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Affymetrix, #78480 1 KT) following manufacturer’s recommendations using the following forward primer: PO45′-AAGGTGGAGAAGCCGCGCGCTGAGGCCGCCAAG-3′. The single codon change was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

The RpL22e-FLAG and RpL22eΔH1-FLAG constructs for expression studies in S2 cells were constructed by standard PCR methods using previously cloned RpL22e cDNA.6 A FLAG-tag was incorporated by inserting the FLAG coding sequence into the reverse primer sequence (5′-GTACGAATTCTTACTTGTCATCGTCATCCTTGTAGTCGCCGCGGCCGATCTCGGCATCGTCGTCCTCATCGTCG-3′) using Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen, #11304011) and cloned into pMT/V5-His-TOPO following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Subsequently, to create RpL22eΔH1-FLAG, a methionine codon (ATG) was added upstream of the coding sequence starting at amino acid 176 in the forward primer (5′-GAATTCATGAAGAACGTGCTGCGTGGCAAGGGACAGAAGAAGAAG-3′) and cloned into pMT/V5-His-TOPO. Proper FLAG-tag fusion and construct sequence was confirmed at each cloning step by Sanger sequencing.

Bacterial SUMOylation assay

Assay was performed essentially as previously reported.29 QSUMO and QΔGG plasmids were a generous gift from Albert Courey (UCLA). For RpL22e, BL21 Star (DE3) E. coli cells (Invitrogen) were co-transformed with pEXP-5/FLAG-RpL22eWT or pEXP-5/FLAG-RpL22eK39R along with QSUMO or QΔCC and plated on to double selective media (LB agar with 100 µg/mL Ampicillin and 50 µg/mL Kanamycin) at 37°C. Resistant transformants were selected to inoculate overnight seed cultures in LB broth with Ampicillin and Kanamycin at 37°C. 100 µL of seed culture was used to inoculate 50mL auto-inducing media as described by Studier with antibiotics in 500 mL baffled flasks at 200rpm.60 Cultures were incubated in a 26°C shaking water bath at 200 rpm until 10.0 OD600. For protein prep, 10mL of culture was pelleted and resuspended in 1mL sonication buffer (1X PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1mM PMSF). Samples were lysed with three 10 sec sonication cycles with 1 min intervals resting ice followed by a 10 min centrifugation step (16,000xg at 4°C) to clear debris. Lysates were quantified and used for SDS-PAGE and Western analysis as described above. For RpL22e-like-PA, the assay was performed identically with pEXP-5/FLAG-L22e-like-PA.

In vitro proteolysis

Proteolysis assays of bacterial SUMOylation assay lysates (see above) using purified trypsin (Sigma) was performed as previously described.27 Reactions were stopped by the addition of an equal volume of reducing sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Subsequently, 5 µg of lysate was used for SDS-PAGE and Western analysis.

Immunoprecipitation

Indirect immunoprecipitation (IP) protocols were adapted from Sanz et al. for S2 cells.61 10 mLs of S2 cells were seeded at 1.0 × 106 cell/mL in T25 flasks and incubated for 3 d at 26°C. Cells were pelleted at 100 xg for 5 min, washed with PBS and lysed in 1mL of IP lysis buffer [10 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7), 100mM KCl, 5mM MgCl2, 1mM DTT, 100µg/mL cycloheximide] for 10 min on ice. A post-mitochondrial fraction was created by centrifugation at 16,000 xg for 10 min in a microcentrifuge at 4°C. 20µg anti-Drosophila SUMO antibody (Abgent, #AP1287b) incubated with 400–500 µL of lysate overnight at 4°C with constant agitation. Antibody-antigen complexes were captured by the addition of 40 µL of prepared magnetic protein A beads (Millipore, #LSKMAGA02) as recommended by the manufacture with constant agitation for 20 min at RT. Upon three washes with high salt IP wash buffer (300 mM KCl), captured proteins were eluted by incubation of excess free peptide at 4°C for 30 min (two rounds of 200 µL free peptide at 100 mg/mL with constant agitation). Eluates were pooled, TCA precipitated as described by Houmani and Ruf, resuspended in reducing SDS-sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE and probed for RpL22e in Western analysis.13

RpL22e IP reactions were performed as described above, but capture used 20 µg anti-RpL22e. Eluates were subjected to Western analysis and probed with anti-Drosophila SUMO.

Phosphatase treatment

10µL reactions using Calf Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase (New England Biolabs, M0290S) were set up as suggested by New England Biolabs. Protein samples were diluted to 1–2 µg/10 µL in 1X NEBuffer 2. Upon the addition of 1 unit of CIP/1 µg protein, reactions were incubated at 37°C for 60 min. PBS was added to negative control samples in lieu of phosphatase. Reactions were either frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C or directly used for SDS-PAGE by adding equal volume of reducing SDS-sample buffer and boiled.

Sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation

S2 cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/mL (9 mLs per drug treatment) and allowed to grow for 3 d at 26°C. Cells were then treated with 100 µg/mL cycloheximide or 300µg/mL puromycin for 10 min on ice, pelleted and washed with ice-cold 1X PBS containing cycloheximide or puromycin. Cells were then lysed in 1mL of ribosome lysis buffer and layered on top of a 10–50% buffered sucrose gradient as described by Houmani and Ruf.13 Gradient preparation, centrifugation conditions and subsequent protein extraction by TCA precipitation was performed as previously described by Houmani and Ruf.13 Gradients were fractionated using a Brandel syringe pump and Foxy Jr. R1 gradient fractionators along with an Isco UA-6 detector for continuous absorbance reading at 254 nm. Fractions were collected in 0.5 mL volumes with 40 sec fraction collection times set with 0.75 mL/min pump speed).

For analysis of RpL22e-FLAG and RpL22eΔH1-FLAG, three wells of S2 cells were transfected as described above. 48 h post-induction, wells were pooled, treated with cycloheximide, lysed and subjected to sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation as described above.62,63

Immunohistochemistry

Testis squashes and immunostaining was performed as previously described for all analyses.6

S2 cell immunostaining was performed as previously described.64 Anti-RpL22e was used at 1:100 in blocking solution for 1 h incubation at room temperature. Cells were mounted in Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech, #0100–01) and imaged with a Nikon Eclipse TE200U.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided in part from Lehigh University Faculty Research Grants (607233 and 607277) to V.C.W. The work described here is in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree for M.G.K., who was partially supported by a Nemes Fellowship. J.A.I., S.M.P. and A.S.C. were supported by undergraduate research grants funded by the College of Arts and Sciences at Lehigh University. A.S.C. was also supported in part as a Lehigh University-Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) student from a grant to Lehigh University from the HHMI through the Precollege and Undergraduate Science Education Program. We thank members of the fly community (noted in Materials and Methods) for their generosity for sharing fly stocks, plasmids, antibodies and cell lines. We also extend our gratitude to Maria Brace for figure assistance and members of the Ware lab for discussions. Members of M.G.K.’s dissertation committee are acknowledged for stimulating discussions about the work reported here.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- bam

bag-of-marbles

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- m

molecular mass

- Rp

ribosomal protein

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-like modifier

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/25261

References

- 1.Komili S, Farny NG, Roth FP, Silver PA. Functional specificity among ribosomal proteins regulates gene expression. Cell. 2007;131:557–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim TY, Ha CW, Huh WK. Differential subcellular localization of ribosomal protein L7 paralogs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cells. 2009;27:539–46. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hummel M, Cordewener JH, de Groot JC, Smeekens S, America AH, Hanson J. Dynamic protein composition of Arabidopsis thaliana cytosolic ribosomes in response to sucrose feeding as revealed by label free MSE proteomics. Proteomics. 2012;12:1024–38. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue S, Barna M. Specialized ribosomes: a new frontier in gene regulation and organismal biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:355–69. doi: 10.1038/nrm3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner JR, McIntosh KB. How common are extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins? Mol Cell. 2009;34:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearse MG, Chen AS, Ware VC. Expression of ribosomal protein L22e family members in Drosophila melanogaster: rpL22-like is differentially expressed and alternatively spliced. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2701–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shigenobu S, Arita K, Kitadate Y, Noda C, Kobayashi S. Isolation of germline cells from Drosophila embryos by flow cytometry. Dev Growth Differ. 2006;48:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00845.x. a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shigenobu S, Kitadate Y, Noda C, Kobayashi S. Molecular characterization of embryonic gonads by gene expression profiling in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13728–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603767103. b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kai T, Williams D, Spradling AC. The expression profile of purified Drosophila germline stem cells. Dev Biol. 2005;283:486–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JA. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:715–20. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavergne JP, Conquet F, Reboud JP, Reboud AM. Role of acidic phosphoproteins in the partial reconstitution of the active 60 S ribosomal subunit. FEBS Lett. 1987;216:83–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marygold SJ, Roote J, Reuter G, Lambertsson A, Ashburner M, Millburn GH, et al. The ribosomal protein genes and Minute loci of Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R216. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houmani JL, Ruf IK. Clusters of basic amino acids contribute to RNA binding and nucleolar localization of ribosomal protein L22. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyama Y, Katagiri S, Hanai S, Uchida K, Miwa M. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase interacts with novel Drosophila ribosomal proteins, L22 and l23a, with unique histone-like amino-terminal extensions. Gene. 1999;226:339–45. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matafora V, D’Amato A, Mori S, Blasi F, Bachi A. Proteomics analysis of nucleolar SUMO-1 target proteins upon proteasome inhibition. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:2243–55. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900079-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staley JP, Woolford JL., Jr. Assembly of ribosomes and spliceosomes: complex ribonucleoprotein machines. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koc EC, Koc H. Regulation of mammalian mitochondrial translation by post-translational modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:1055–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young BD, Weiss DI, Zurita-Lopez CI, Webb KJ, Clarke SG, McBride AE. Identification of methylated proteins in the yeast small ribosomal subunit: a role for SPOUT methyltransferases in protein arginine methylation. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5091–104. doi: 10.1021/bi300186g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spence J, Gali RR, Dittmar G, Sherman F, Karin M, Finley D. Cell cycle-regulated modification of the ribosome by a variant multiubiquitin chain. Cell. 2000;102:67–76. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruvinsky I, Sharon N, Lerer T, Cohen H, Stolovich-Rain M, Nir T, et al. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation is a determinant of cell size and glucose homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2199–211. doi: 10.1101/gad.351605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yacoub A, Augeri L, Kelley MR, Doetsch PW, Deutsch WA. A Drosophila ribosomal protein contains 8-oxoguanine and abasic site DNA repair activities. EMBO J. 1996;15:2306–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandigursky M, Yacoub A, Kelley MR, Xu Y, Franklin WA, Deutsch WA. The yeast 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (Ogg1) contains a DNA deoxyribophosphodiesterase (dRpase) activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4557–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deutsch WA, Yacoub A, Jaruga P, Zastawny TH, Dizdaroglu M. Characterization and mechanism of action of Drosophila ribosomal protein S3 DNA glycosylase activity for the removal of oxidatively damaged DNA bases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32857–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jang CY, Kim HD, Zhang X, Chang JS, Kim J. Ribosomal protein S3 localizes on the mitotic spindle and functions as a microtubule associated protein in mitosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;429:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HD, Lee JY, Kim J. Erk phosphorylates threonine 42 residue of ribosomal protein S3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:110–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim TS, Kim HD, Shin HS, Kim J. Phosphorylation status of nuclear ribosomal protein S3 is reciprocally regulated by protein kinase Cdelta and protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21201–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jang CY, Shin HS, Kim HD, Kim JW, Choi SY, Kim J. Ribosomal protein S3 is stabilized by sumoylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414:523–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao W, Bidwai AP, Glover CV. Interaction of casein kinase II with ribosomal protein L22 of Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:60–6. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02396-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie M, Xie Y, Loo JA, Courey AJ. Genetic and proteomic evidence for roles of Drosophila SUMO in cell cycle control, Ras signaling, and early pattern formation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shcherbik N, Pestov DG. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins in the nucleolus: multitasking tools for a ribosome factory. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:681–9. doi: 10.1177/1947601910381382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galisson F, Mahrouche L, Courcelles M, Bonneil E, Meloche S, Chelbi-Alix MK, et al. A novel proteomics approach to identify SUMOylated proteins and their modification sites in human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:004796. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:947–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lomelí H, Vázquez M. Emerging roles of the SUMO pathway in development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:4045–64. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0792-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhaskar V, Smith M, Courey AJ. Conjugation of Smt3 to dorsal may potentiate the Drosophila immune response. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:492–504. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.492-504.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauri F, McNamee LM, Lunardi A, Chiacchiera F, Del Sal G, Brodsky MH, et al. Modification of Drosophila p53 by SUMO modulates its transactivation and pro-apoptotic functions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20848–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710186200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith M, Mallin DR, Simon JA, Courey AJ. Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) conjugation impedes transcriptional silencing by the polycomb group repressor Sex Comb on Midleg. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11391–400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulrich HD. The fast-growing business of SUMO chains. Mol Cell. 2008;32:301–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]