Abstract

Introduction

Vitamin D may have an immunological role in Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Retrospective studies suggested a weak association between vitamin D status and disease activity but have significant limitations.

Methods

Using a multi-institution inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) cohort, we identified all CD and UC patients who had at least one measured plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D]. Plasma 25(OH)D was considered sufficient at levels ≥ 30ng/mL. Logistic regression models adjusting for potential confounders were used to identify impact of measured plasma 25(OH)D on subsequent risk of IBD-related surgery or hospitalization. In a subset of patients where multiple measures of 25(OH)D were available, we examined impact of normalization of vitamin D status on study outcomes.

Results

Our study included 3,217 patients (55% CD, mean age 49 yrs). The median lowest plasma 25(OH)D was 26ng/ml (IQR 17–35ng/ml). In CD, on multivariable analysis, plasma 25(OH)D < 20ng/ml was associated with an increased risk of surgery (OR 1.76 (1.24 – 2.51) and IBD-related hospitalization (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.59 – 2.68) compared to those with 25(OH)D ≥ 30ng/ml. Similar estimates were also seen for UC. Furthermore, CD patients who had initial levels < 30ng/ml but subsequently normalized their 25(OH)D had a reduced likelihood of surgery (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 – 0.98) compared to those who remained deficient.

Conclusion

Low plasma 25(OH)D is associated with increased risk of surgery and hospitalizations in both CD and UC and normalization of 25(OH)D status is associated with a reduction in the risk of CD-related surgery.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, vitamin D, surgery, hospitalization

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic immunologically mediated diseases that often have their onset at a young age and are associated with recurrent episodes of relapsing disease activity1. Nearly two-thirds of patients with CD and one-fifth of those with UC will eventually require surgery for management of their refractory disease or disease-related complication2–6. A larger proportion of patients will require at least one IBD-related hospitalization2. Thus, both surgery and hospitalization represent major events in the natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD; CD and UC) and are responsible for a substantial portion of the estimated $6 billion in annual healthcare costs associated with these diseases7. Identification of risk factors for such adverse outcomes and interventions that may reduce the risk of such adverse outcomes are an important need.

Vitamin D has been classically described in association with its effect on bone mineralization. However, there is considerable interest in the immunological effects of vitamin D8–14. Indeed, a recent body of literature has substantiated a significant role of vitamin D in IBD. Residence in areas with reduced ultraviolet light exposure15 or a lower predicted plasma vitamin D level16 is associated with an increased risk for CD. Furthermore, retrospective or cross-sectional studies have suggested an association between lower vitamin D and disease activity in CD17–19. However, they have been limited by the inability to temporally separate the effect of plasma 25(OH)D, the best measure of an individuals vitamin D status, and subsequent adverse outcomes. Consequently, there is a need for prospective studies examining the association between vitamin D status and risk for subsequent surgery or hospitalization. In addition, it is also of interest to examine if a change in vitamin D status, in particular, normalization of plasma 25(OH)D levels, can attenuate the risk associated with deficient vitamin D. This hypothesis is supported by laboratory data from animal models where vitamin D supplementation ameliorated colitis20, and from a randomized controlled trial where CD patients in remission randomized to vitamin D had a lower rate of relapse over 12 months compared to placebo21.

We performed the present study with the aims of (1) examining the association between plasma 25(OH)D and risk of subsequent IBD-related surgery or hosptalization in a large cohort of CD and UC patients; and (2) analyzing whether normalization of vitamin D status in those with insufficient or deficient levels is associated with a reduction in risk for surgery or hospital stays.

METHODS

Study Population

The data source for our study was an electronic medical record (EMR) based cohort of CD and UC patients from two tertiary medical centers in Boston serving a population of over 4 million patients in the Greater Boston area as well as neighboring states. The development and validation of our cohort has been described in detail in previous publications22. From among patients with at least one International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9-CM) clinical modification code for CD (555.x) or UC (556.x) (n = 24,182), we refined our cohort by developing an algorithm incorporating codified data as well as narrative free text concepts from the EMR identified using natural language processing tools. The positive predictive value of our final algorithms were 97% for both CD and UC, confirmed in an independent validation cohort, and yielded a final CD cohort of 5,506 patients and 5,522 UC patients.

Development of the study cohort

This study was restricted to a subset of 3,217 CD or UC patients with at least one measured plasma 25(OH)D level. Patients who had ≥ 1 plasma 25(OH)D measure were similar in age to those without a vitamin D level, but were more likely to be female (61% vs. 50%), use immunomodulator or anti-TNF therapy, and undergo an IBD-related surgery (16% vs. 10%) or hospitalization (40% vs. 27%). The plasma 25(OH)D was measured as part of routine clinical care at the two hospitals using high performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry since 2008 and radioimmunoassay prior to that with similar normal values across both assays. The dates of plasma 25(OH)D measurements, the lowest, and highest values were retrieved and modeled as normal (> 30ng/ml), insufficient (20 – 29.9ng/ml) or deficient (< 20ng/ml) according to current recommendations23–25.

Variables and Outcomes

Information on current age, age at first ICD-9-CM code for CD or UC, gender, race (white or non-white) and non-IBD co-morbidity modeled using the Deyo modification of the Charlson co-morbidity index26 were obtained as was duration of follow-up within our healthcare system. Using the electronic prescription function of our EMR, we ascertained use of IBD-related medications including aminosalicylates, systemic corticosteroids, immunomodulators (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate), and anti-tumor necrosis factor α monoclonal antibodies (anti-TNF). We also additionally assessed for use of prescription vitamin D supplementation as well as use of high dose ergocalciferol (50,000 international units (IU) weekly).

Our primary outcomes were undergoing an IBD-related surgery or hospitalization identified using the appropriate procedure ICD-9 codes for surgical procedures (Supplemental Table 1) or the presence of CD or UC as the primary diagnosis for hospitalizations. Patients were censored at the first such event and plasma 25(OH)D measures beyond this time point were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using Stata 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations while categorical variables were expressed as percentages. The t-test was used to compare continuous variables with the chi-square test being used for comparison of categorical variables. Univariate logistic regression was used to identify predictors of IBD-related surgery, constructing separate models for CD and UC and modeling plasma 25(OH)D status using the lowest measured level (prior to surgery or end of follow-up) and the three strata described above. Multivariable logistic regression was then used to examine the independent effect of vitamin D status on risk of IBD-related surgery or hospitalization. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

For the analysis of the effect of normalization of vitamin D status, we restricted the cohort to patients with at least 2 measures of plasma 25(OH)D examining whether they had ever achieved a normal level of plasma 25(OH)D prior to the event of interest (surgery or hospitalization). Similar multivariable regression models were constructed to examine both predictors of normalization of plasma 25(OH)D as well as to examine the effect of such normalization on risk of surgery and hospitalization. Ethical approval for our study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Partners Healthcare.

RESULTS

Study Population

Our study included a total of 3,217 patients (55% CD, 45% UC) with at least one measured plasma 25(OH) D. The mean age of the cohort was 49 years with a mean age of 41 years at the first ICD-9 code for CD or UC (Table 1). Most of the patients were Caucasian (81%) and a majority were female (61%). At least half the patients had a history of systemic corticosteroid use (54%) while just under a quarter had a history of anti-TNF use (21%). The median lowest plasma 25(OH)D was 26 ng/ml (interquartile range (IQR) 17 – 35ng/ml) with median highest plasma 25(OH)D of 35ng/ml (IQR 26 – 44 ng/ml). Just under a third of patients each had insufficient (28%) or deficient (32%) 25(OH)D levels. The median number of 25(OH)D measurements prior to surgery or end of follow up was 1 (IQR 1–3); half the cohort (49%) had 2 or more measurements.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 3,217 (100%) |

| Median age (in years) (IQR) | 48 (34 – 63) |

| Median age at first IBD ICD-9 code (in years) (IQR) | 40 (28 – 54) |

| Female | 1,954 (61%) |

| Race | |

| White | 2,812 (87%) |

| Non-white | 238 (8%) |

| Other/Unknown | 167 (5%) |

| Mean Charlson score (SD) | 3.7 (3.6) |

| IBD type | |

| Crohn’s disease | 1,763 (55%) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1,454 (45%) |

| IBD-related medications | |

| Corticosteroids | 1,732 (54%) |

| 5-aminosalicylates | 1,942 (60%) |

| Immunomodulators | 1,255 (39%) |

| Anti-TNF biologics | 688 (21%) |

| IBD-related surgery | 525 (16%) |

| IBD-related hospitalization | 1,293 (40%) |

| Median lowest plasma 25(OH)D measurement (IQR) | 26 ng/mL (17 – 35) |

| Median highest plasma 25(OH)D measurement (IQR) | 35 ng/mL (26 – 44) |

IBD – inflammatory bowel diseases, IQR – interquartile range, SD – standard deviation, TNF – tumor necrosis factor

Plasma 25(OH)D and risk of IBD-related surgery and hospitalization

Table 2 describes the association between the lowest measured plasma 25(OH)D and subsequent risk of surgery. Only 10% of CD patients who were never deficient in vitamin D subsequently underwent an IBD-related surgery compared to 13% of those with insufficient levels (Odds ratio (OR) 1.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.24 – 2.34) and 17% of those with deficient levels below 20ng/ml (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.53 – 2.75). The association between plasma 25(OH)D and surgery remained significant on multivariable analysis adjusting for age, gender, Charlson co-morbidity, season of measurement, duration of follow up and use of immunomodulator or anti-TNF therapies. A similar association was seen for CD-related hospitalizations with a dose-response effect observed for progressively lower levels of 25(OH)D (Table 2).

Table 2.

Plasma 25(OH)D and risk of IBD-related surgery and hospitalization

| Surgery | Hospitalizations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 30ng/ml | 20 – 29.9 ng/ml | < 20 ng/mL | ≥ 30ng/ml | 20 – 29.9 ng/ml | < 20 ng/mL | |

| Crohn’s disease | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 1.70 (1.24 – 2.34) | 2.05 (1.53 – 2.75) | 1.0 | 1.65 (1.30 – 2.10) | 2.49 (1.98 – 3.12) |

| Adjusted† | 1.0 | 1.54 (1.06 – 2.25) | 1.76 (1.24 – 2.51) | 1.0 | 1.56 (1.20 – 2.04) | 2.07 (1.59 – 2.68) |

| Ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 1.17 (0.80 – 1.72) | 1.75 (1.21 – 2.52) | 1.0 | 1.27 (0.96 – 1.66) | 2.22 (1.70 – 2.91) |

| Adjusted† | 1.0 | 1.13 (0.68 – 1.86) | 2.10 (1.32 – 3.34) | 1.0 | 1.18 (0.87 – 1.62) | 2.26 (1.66 – 3.06) |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, Charlson co-morbidity, season of measurement of vitamin D, use of immunomodulators or anti-TNF biologics, and duration of follow-up

For patients with UC, an association between plasma 25(OH)D below 20ng/ml and elevated risk of surgery and hospitalization was observed with an effect size similar to that observed for CD. However, the stratum with insufficient vitamin D (levels between 20–29.9ng/ml) did not demonstrate a statistically significant elevation in risk of surgery or hospitalization (Table 2).

Predictors of Normalization of Vitamin D status

We examined predictors of normalization of vitamin D status in patients with at least 2 measurements of plasma 25(OH)D (median interval between the two measures was 294 days). Just over three-quarters of patients with CD (404/538, 75%) and UC (80%) had a normal plasma 25(OH)D ≥ 30ng/ml following an initial measure below this threshold (“normalized” patients). Table 3 describes the variables associated with normalization. Older age increased likelihood of normalization (OR 1.16 for every 10 year increase in age, 95% CI 1.06 – 1.28) as did a higher baseline vitamin D level (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.09 – 1.15 for every 1ng/ml). Supplemental vitamin D use was seen in 52% of those with low vitamin D levels and was associated with a higher likelihood of normalization (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.31 – 2.66). Non-white race was associated with a significant lower likelihood of normalization (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30 – 0.92).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Normalization of plasma 25(OH)D in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age (for every 10 years) | 1.16 | 1.06 – 1.28 |

| Non-white race | 0.53 | 0.30 – 0.92 |

| Lowest vitamin D level (for every 1 ng/ml increase) | 1.12 | 1.09 – 1.15 |

| Supplemental Vitamin D use | 1.87 | 1.31 – 2.66 |

| Season of initial measurement | ||

| Spring | Reference | |

| Summer | 1.29 | 0.78 – 2.15 |

| Fall | 1.16 | 0.75 – 1.82 |

| Winter | 1.49 | 0.99 – 2.26 |

Effect of normalization of vitamin D status on risk of surgery and hospitalization

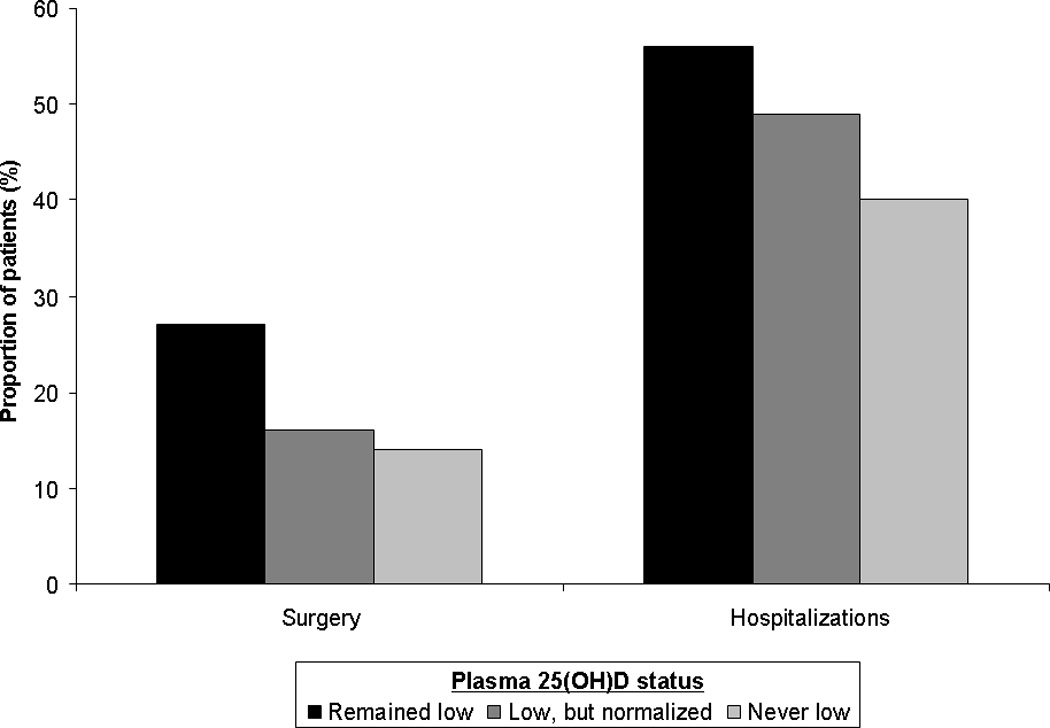

We then examined if normalization of vitamin D status influenced risk of surgery and hospitalization in CD and UC. In patients with CD, those who had an initial low level of 25(OH)D but subsequently normalized their values had a significantly lower likelihood of requiring surgery on multivariable analysis (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 – 0.98) compared to those who remained low (Table 4, Figure 1). While this difference was also seen for hospitalizations on univariate analysis, the effect did not achieve independent statistical significance on multivariable analysis. In contrast, we did not observe a reduction in the likelihood of surgery or hospitalization associated with normalization of vitamin D status in UC patients. CD patients who normalized their vitamin D status also had a significantly lower median C-reactive protein (10.7mg/dl vs. 16.2 mg/dl, adjusted regression co-efficient (β): −5.2, 95% CI −9.5 to −1.02) that those who remained low; this effect was not seen in UC (β: −8.5mg/dl, 95% CI −35.2 to 18.2 mg/dl).

Table 4.

Effect of normalization of plasma 25(OH)D and risk of surgery and hospitalizations in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Surgery | Hospitalizations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not normalize | Normalize | Did not normalize | Normalized | |

| Crohn’s disease | ||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 0.51 (0.32 – 0.82) | 1.0 | 0.64 (0.44 – 0.96) |

| Adjusted† | 1.0 | 0.56 (0.32 – 0.98) | 1.0 | 0.78 (0.51 – 1.25) |

| Ulcerative colitis | ||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 1.02 (0.45 – 2.31) | 1.0 | 0.88 (0.52 – 1.47) |

| Adjusted† | 1.0 | 0.75 (0.29 – 1.93) | 1.0 | 0.78 (0.44 – 1.40) |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, Charlson co-morbidity, use of immunomodulators or anti-TNF biologics, and duration of follow-up

Figure 1.

Normalization of plasma 25(OH)D and risk of surgery in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

We repeated the analysis including all patients with at least one measure of vitamin D status, carrying forward the single plasma 25(OH)D measure for those with only one lab value. The association between normalization of plasma 25(OH)D and reduced risk of surgery in CD remained (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.32 – 0.70) with a significant effect also observed for reduced risk of hospitalization (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.38 – 0.69). No effect was observed for ulcerative colitis.

DISCUSSION

Vitamin D plays an important immunologic role in inflammatory bowel diseases9–13. In a large IBD cohort, we demonstrate that (1) low plasma 25(OH)D is an independent risk factor for both UC and CD-related surgery and hospitalization; and (2) CD patients who normalize their vitamin D status have a lower risk of subsequent CD-related surgery that those whose levels remained low.

There has been growing data on vitamin D status in cohorts of IBD patients. However, many of the studies have limitations that preclude drawing conclusions regarding the immunologic effect of vitamin D. First, a majority of studies focused on describing a cross-sectional prevalence of insufficient or deficient vitamin D in their cohorts, or risk factors thereof, with a limited ability to prospectively examine consequences of vitamin D deficiency17–19, 27. Second, the studies that did examine the association with disease activity were limited by retrospective ascertainment of cumulative disease burden such that the low vitamin D could have temporally followed the outcome measured17–19. In this study, using a large cohort of over 3,200 IBD patients with at least one measured plasma 25(OH)D, we demonstrate that low plasma 25(OH)D is independently associated with an increased risk of subsequent surgery and hospitalization in both CD and UC patients. Furthermore, in CD, we also observed a dose-response effect with a progressively higher frequency of surgery and hospitalizations in those with insufficient (25(OH)D between 20–29.9ng/ml) and deficient (25(OH)D < 20ng/ml) levels.

Though one cannot exclude the possibility that improvement in vitamin D status was consequent to increasing physical activity and outdoor sun exposure as better control of disease is achieved, considerable evidence both from our study and prior work suggests this is unlikely to be the explanation for our findings. First, in our study, the effect of normalization of plasma 25(OH)D on reduction in risk of CD-related surgery remained significant after adjusting for inflammatory burden quantified using median C-reactive protein levels, as well as use of medical therapies (immunomodulator or anti-TNF) initiated to achieve disease control, suggesting that vitamin D status is not merely a marker of disease activity or severity but potentially a biologically relevant parameter. Furthermore, there is also supporting biologic evidence on how vitamin D could influence disease activity in CD. In an IL-10 knockout model of colitis, Cantorna et al. demonstrated that administration of 1,25-dihydroxy cholecalciferol was associated with amelioration of colitis with a dose-response effect similar to that observed in our study20. In a second study, a vitamin D analogue similarly ameliorated TNBS mediated colitis and decreased both clinical and macroscopic activity scores28. In addition, Zhu et al. demonstrated that administration of vitamin D was associated with a reduction in the colonic expression of TNF-related genes29.

A randomized controlled trial examined the effect of vitamin D supplementation on disease activity in CD. Jorgensen et al. randomized 94 patients to placebo or vitamin D 1200 IU daily in conjunction with 1200mg/day of calcium in both arms21. At the end of one year, there was a trend towards lower frequency of relapse in the vitamin D (13%) compared to the placebo arm (29%, p=0.06). The median plasma 25(OH)D increased from 27ng/ml to 38ng/ml at 3 months and was sustained at the higher level through 12 months. Our findings of the effect of normalization similarly support that attainment of a vitamin D level above 30ng/ml is associated with a reduction in risk of CD-related surgery. In our study, though reduction in CD-related hospitalizations was not statistically significant on multivariable analysis, we did find a statistically significant drop in rate of hospitalizations of a similar magnitude when the cohort was expanded to include those with at least one measured plasma 25(OH)D, suggesting consistency in effects. In a smaller study, Miheller et al. compared two different vitamin D formulations – cholecalciferol 1000 IU/day and alfacalcidol 0.50mcg/day and found a reduction in the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI), C-reactive protein and SIBDQ30. Our findings support this and expand it to a larger cohort by additionally demonstrating that CD patients who normalized their plasma 25(OH)D measurements had a lower median C-reactive protein than those who remained low.

It was interesting that we observed this effect of normalization among CD but not UC patients. First, this may indicate that a higher plasma 25(OH)D threshold is required to attain immunologic activity in UC compared to CD. The lack of an effect of insufficient (plasma 25(OH)D 20–29.9mg/dl) vitamin D on risk of surgery or hospitalization in UC supports this plausibility. However, there is also biological evidence suggesting a stronger interplay between vitamin D status and CD compared to UC. In a previous study, Ananthakrishnan et al. found that lower predicted plasma 25(OH)D was associated with an increased risk for incident CD but not UC16. Similarly, Ulitsky et al. identified an association between low vitamin D and disease activity in CD but not UC17. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation and parallel DNA sequencing (ChIP-Seq), Ramagopalan et al. found that calcitriol administration led to enrichment of vitamin D receptor (VDR) binding sites in proximity to several autoimmune loci including the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 locus (NOD2) on chromosome 1631. NOD2 is a risk allele with a strong effect on CD but not UC, and is associated with ileal disease location, fibrostenosing phenotype, and need for surgery32. Also mediated through VDR, administration of calcitriol leads to induction of NF-κB inhibitory proteins, and reduction in NF-κB mediated production of TNF and other inflammatory cytokines33. Binding of VDR by 1,25(OH)D regulates NOD2 transcription and induces NF-κB -mediated expression of defensins (DEFB2/HBD2)34.

Our findings have a few clinical implications. To our knowledge, ours is the largest cohort examining the effect of vitamin D status on natural history and outcomes of CD and UC. Furthermore, prior studies have been limited by cross-sectional assessment of vitamin D status at a single time point, or cumulative average of vitamin D measures over the entire study period17–19. Using our distinct and repeated measures of plasma 25(OH)D, we were able to additionally demonstrate that CD patients who normalized their vitamin D had a lower likelihood of surgery. This finding, in conjunction with the supportive laboratory data10, 20 and the Jorgensen trial21 suggest a need for prospective studies of vitamin D as an intervention in the management of IBD. Further data is also needed on whether the role of vitamin D is restricted to maintenance of remission as examined in the trial, or if it could also play a role in induction in combination with existing therapy.

There are a few limitations to our study. First, plasma 25(OH)D levels were not available for all patients in our cohort; there likely exists both a provider- and a patient-level bias in obtaining vitamin D levels. However, patients for whom measures of vitamin D status was available were sicker than those without a measured level suggesting that our findings are particularly relevant in a cohort enriched for adverse outcomes. Second, not all patients had multiple measures of plasma vitamin D, and at pre-defined time points. However, our findings remained robust in analyses that included those with single or multiple measures. Third, we did not have information on dietary vitamin D or supplemental vitamin D that was not captured in the electronic medical records. However, since our primary variable, directly measured plasma 25(OH)D, is a comprehensive reflection of dietary intake, vitamin D absorption, and vitamin D from other sources including sun exposure, we believe our findings to have greater biological relevance than studies examining vitamin D intake alone. As in most observational studies, the effect of unmeasured confounders cannot be excluded. We also did not have the ability to adjust in detail for disease location which could predict need for surgery. However, for small bowel disease location to be a confounder, it would have to be associated with both our predictor (vitamin D) and outcome (surgery), and several prior studies have failed to identify an association between small bowel CD with low vitamin D status17–19. Furthermore, vitamin D intake contributes to only a small fraction on an individual’s overall vitamin D status35. Finally, it is also possible that vitamin D repletion is a marker of compliance with treatment, or overall health status. Causality cannot be inferred from an observational study, but the wealth of laboratory data supporting a bioactive role of vitamin D in intestinal inflammation provides significant biologic plausibility to this association.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that low plasma 25(OH)D is associated with increased risk of surgery in CD and UC, with a dose-response relationship observed in CD. Furthermore, CD patients who normalized their vitamin D had a lower risk of subsequent surgery than those who remained deficient suggesting a need to examine the role of vitamin D supplementation as an intervention in the management of CD. However, only a subset of patients had measured 25(OH)D at multiple time points, and detailed dietary vitamin D intake, physical activity, or sunlight exposure was not available. Larger prospective studies in other cohorts as well as randomized intervention trials are required to definitively establish if modulating vitamin D status can help in the therapy of IBD and improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The study was supported by NIH U54-LM008748. A.N.A is supported by funding from the US National Institutes of Health (K23 DK097142). K.P.L. is supported by NIH K08 AR060257 and the Katherine Swan Ginsburg Fund. R.M.P. is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01-AR056768, U01-GM092691 and R01-AR059648) and holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. E.W.K is supported by grants from the NIH (K24 AR052403, P60 AR047782, R01 AR049880).

Footnotes

Authorship Statement

Guarantor of the article: Dr. Ananthakrishnan

Specific author contributions:

Study concept – Ananthakrishnan

Study design – Ananthakrishnan

Data Collection – Ananthakrishnan, Gainer, Cagan, Cai, Cheng, Savova, Chen, Churchill, Kohane, Shaw, Xia, De Jager, Plenge, Liao, Szolovits, Murphy

Analysis – Ananthakrishnan

Preliminary draft of the manuscript – Ananthakrishnan

Approval of final version of the manuscript – Ananthakrishnan, Gainer, Cai, Cagan, Cheng, Savova, Chen, Xia, De Jager, Shaw, Churchill, Karlson, Kohane, Plenge, Murphy, Liao

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein CN, Loftus EV, Jr, Ng SC, Lakatos PL, Moum B. Hospitalisations and surgery in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2012;61:622–629. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakatos L, Kiss LS, David G, Pandur T, Erdelyi Z, Mester G, Balogh M, Szipocs I, Molnar C, Komaromi E, Lakatos PL. Incidence, disease phenotype at diagnosis, and early disease course in inflammatory bowel diseases in Western Hungary, 2002–2006. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2558–2565. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, Aadland E, Hoie O, Cvancarova M, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Sauar J, Vatn MH, Moum B. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–440. doi: 10.1080/00365520802600961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Targownik LE, Singh H, Nugent Z, Bernstein CN. The epidemiology of colectomy in ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Afchain P, Tiret E, Gendre JP. Impact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn's disease on the need for intestinal surgery. Gut. 2005;54:237–241. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.045294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, Ollendorf DA, Sandler RS, Galanko JA, Finkelstein JA. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907–1913. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. D-hormone and the immune system. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2005;76:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting evidence for vitamin D as an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1136–1142. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantorna MT, Zhu Y, Froicu M, Wittke A. Vitamin D status, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and the immune system. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1717S–1720S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1717S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim WC, Hanauer SB, Li YC. Mechanisms of disease: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:308–315. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narula N, Marshall JK. Management of inflammatory bowel disease with vitamin D: beyond bone health. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholson I, Dalzell AM, El-Matary W. Vitamin D as a therapy for colitis: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg M, Lubel JS, Sparrow MP, Holt SG, Gibson PR. Review article: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease - established concepts and future directions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:324–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalili H, Huang ES, Ananthakrishnan AN, Higuchi L, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, Chan AT. Geographical variation and incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among US women. Gut. 2012 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Bao Y, Korzenik JR, Giovannucci EL, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, Chan AT. Higher predicted vitamin d status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:482–489. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulitsky A, Ananthakrishnan AN, Naik A, Skaros S, Zadvornova Y, Binion DG, Issa M. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: association with disease activity and quality of life. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:308–316. doi: 10.1177/0148607110381267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph AJ, George B, Pulimood AB, Seshadri MS, Chacko A. 25 (OH) vitamin D level in Crohn's disease: association with sun exposure & disease activity. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tajika M, Matsuura A, Nakamura T, Suzuki T, Sawaki A, Kato T, Hara K, Ookubo K, Yamao K, Kato M, Muto Y. Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency in patients with Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:527–533. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantorna MT, Munsick C, Bemiss C, Mahon BD. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol prevents and ameliorates symptoms of experimental murine inflammatory bowel disease. J Nutr. 2000;130:2648–2652. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorgensen SP, Agnholt J, Glerup H, Lyhne S, Villadsen GE, Hvas CL, Bartels LE, Kelsen J, Christensen LA, Dahlerup JF. Clinical trial: vitamin D3 treatment in Crohn's disease - a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:377–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ananthakrishnan AN, Cai T, Savova G, Chen P, Guzman Perez R, Gainer VS, Murphy SN, Szolovits P, Xia Z, Shaw S, Churchill S, Karlson EW, Kohane I, Plenge RM, Liao KP. Improving Case Definition of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Electronic Medical Records Using Natural Language Processing: A Novel Informatics Approach. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828133fd. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, Holick MF, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Vieth R. Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:713–716. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen CJ. Clinical practice. Vitamin D insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:248–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1009570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilman J, Shanahan F, Cashman KD. Determinants of vitamin D status in adult Crohn's disease patients, with particular emphasis on supplemental vitamin D use. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:889–896. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniel C, Radeke HH, Sartory NA, Zahn N, Zuegel U, Steinmeyer A, Stein J. The new low calcemic vitamin D analog 22-ene-25-oxa-vitamin D prominently ameliorates T helper cell type 1-mediated colitis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:622–631. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y, Mahon BD, Froicu M, Cantorna MT. Calcium and 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target the TNF-alpha pathway to suppress experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:217–224. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miheller P, Muzes G, Hritz I, Lakatos G, Pregun I, Lakatos PL, Herszenyi L, Tulassay Z. Comparison of the effects of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D and 25 hydroxyvitamin D on bone pathology and disease activity in Crohn's disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1656–1662. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramagopalan SV, Heger A, Berlanga AJ, Maugeri NJ, Lincoln MR, Burrell A, Handunnetthi L, Handel AE, Disanto G, Orton SM, Watson CT, Morahan JM, Giovannoni G, Ponting CP, Ebers GC, Knight JC. A ChIP-seq defined genome-wide map of vitamin D receptor binding: associations with disease and evolution. Genome Res. 2010;20:1352–1360. doi: 10.1101/gr.107920.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adler J, Rangwalla SC, Dwamena BA, Higgins PD. The prognostic power of the NOD2 genotype for complicated Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:699–712. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu S, Xia Y, Liu X, Sun J. Vitamin D receptor deletion leads to reduced level of IkappaBalpha protein through protein translation, protein-protein interaction, and post-translational modification. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang TT, Dabbas B, Laperriere D, Bitton AJ, Soualhine H, Tavera-Mendoza LE, Dionne S, Servant MJ, Bitton A, Seidman EG, Mader S, Behr MA, White JH. Direct and indirect induction by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 of the NOD2/CARD15-defensin beta2 innate immune pathway defective in Crohn disease. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2227–2231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.071225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, Hollis BW, Fuchs CS, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:451–459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.